Abstract

DNA electrophoretic mobilities are highly dependent on the nature of the matrix in which the separation takes place. This review describes the effect of the matrix on DNA separations in agarose gels, polyacrylamide gels and solutions containing entangled linear polymers, correlating the electrophoretic mobilities with information obtained from other types of studies. DNA mobilities in various sieving media are determined by the interplay of three factors: the relative size of the DNA molecule with respect to the effective pore size of the matrix, the effect of the electric field on the matrix, and specific interactions of DNA with the matrix during electrophoresis.

Keywords: DNA electrophoresis, agarose gels, polyacrylamide gels, entangled polymer solutions, capillary electrophoresis, matrix effects

1. Introduction

DNA electrophoresis, defined as the migration of DNA molecules in a supporting medium under the influence of an electric field, is one of the most useful tools in modern molecular biology and biotechnology. In most cases, electrophoresis is carried out in agarose or polyacrylamide slab gels or in narrow bore capillaries containing linear polymer solutions. The matrix provides a torturous path through which the DNA molecules migrate in the electric field; sieving of the DNA molecules through pores of different sizes provides a mechanism for separation by molecular mass. A second purpose of the matrix is to prevent convective currents in the solution from disturbing the separation. However, it is important to realize that the matrix itself may affect the separation, as will be described here.

The present review brings together a wide range of observations using electrophoresis and other experimental techniques, scattered throughout the scientific literature, that offer insight into the effect of different matrices on DNA separations. The focus will be on DNA separations in the most commonly used slab gels and linear polymer solutions, rather than an exhaustive survey of the literature. The mobility of DNA in free solution will also be described briefly. The combined results indicate that DNA electrophoretic mobilities are determined by the interplay of three factors: the relative size of the DNA molecules with respect to the effective pore size of the matrix, the effect of the electric field on the matrix, and specific interactions of the matrix with the DNA molecules during electrophoresis. The relative importance of each of these factors depends on the matrix, the conformation of the DNA and the experimental conditions. Previous reviews of DNA electrophoresis may be found in references [1-7]; the theory of DNA electrophoresis is reviewed in references [1,3,8-10].

2. Background

In free solution, DNA molecules larger tha ∼400 base pairs (bp) migrate with a mobility that is independent of size [11,12], because the charge/unit mass is the same for all DNA molecules. However, the mobility is reduced in slab gels or entangled polymer solutions and becomes dependent on molecular mass. It is usually assumed that the reduced mobility is related to the fractional volume of the matrix that is available to the migrating macromolecules, according to Eq. (1):

| (1) |

Here, μ is the mobility observed in the matrix, μo is the free solution mobility and f(C) is related to the available fractional volume in the gel or entangled polymer solution [13]. If it is assumed that the sieving mechanism in the matrix is similar to that described by Ogston [14] for spheres placed in a random array of fibers, f(C) can be related to gel concentration, C, as shown by Eq. (2):

| (2) |

where K, the retardation coefficient, is dependent on macromolecular size [15-17]. Plots of the logarithm of μ/μo as a function of gel concentration are known as Ferguson plots [18]. Linear Ferguson plots indicate that the separation is taking place in the Ogston sieving regime, where the average pore radius of the gel is larger than the radius of gyration of the migrating macromolecules. Lattice models of DNA gel electrophoresis have shown that Eq. (2) can be used as a reasonable approximation of the actual sieving mechanism [19,20].

When the radius of gyration of the migrating DNA molecules becomes larger than the average pore size of the matrix, the DNA molecules must “thread” their way end-on through the matrix, a process known as reptation [21-24]. The reptation regime is often divided into two parts: reptation without orientation and reptation with orientation. In the reptation without orientation regime, the DNA conformation is not distorted by the electric field and the mobility decreases approximately linearly with increasing molecular mass [1,25-27]. Larger DNA molecules become stretched and oriented in the direction of the electric field, presenting a constant cross-section to the matrix. Under these conditions, known as the reptation with orientation regime, separation by molecular mass is not possible [25].

3. Agarose gels

Agarose gels are used for the routine determination of DNA size and the purification of restriction fragments and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products. The gels are usually characterized by the percentage (w/v) of agarose in the matrix (%A). Agarose gels are most often used to separate DNA molecules ranging in size from ∼100 bp to ∼20 kilobase pairs (kbp) in unidirectional electric fields [28].

3.1. Agarose gel structure

Agarose is an alternating copolymer of 1,3-linked β-D-galactose and 1,4-linked 3,6-anhydro-α-L-galactose [29-31]. The backbone is variably substituted with charged groups such as carboxylate, pyruvate and/or sulfate; different types of agarose have different concentrations of charged groups attached to the backbone. Some of the anhydrogalactose residues exist in an unbranched, open ring form, leading to structural discontinuities in the agarose backbone called junction zones; crosslinking between the agarose chains is thought to occur in the junction zones [29,32,33].

Agarose is dissolved by heating the fibrous powder in an aqueous solution. The agarose chains have a random coil conformation in solution at high temperatures [33-35]. Upon cooling, the agarose chains undergo a transition leading to the formation of helical fiber bundles containing multiple chains held together by noncovalent hydrogen bonds [35-40]. Gelation occurs at still lower temperatures, when the helical fiber bundles become linked together at the junction zones. Strand partner exchange occurs within the junction zones by hydrogen bond rearrangements [32,33,38]. Electron micrographs have shown that the agarose gel matrix is a random fibrous network with irregularly spaced branch points and many dangling ends [30,31,41-45].

3.2. Effective pore size

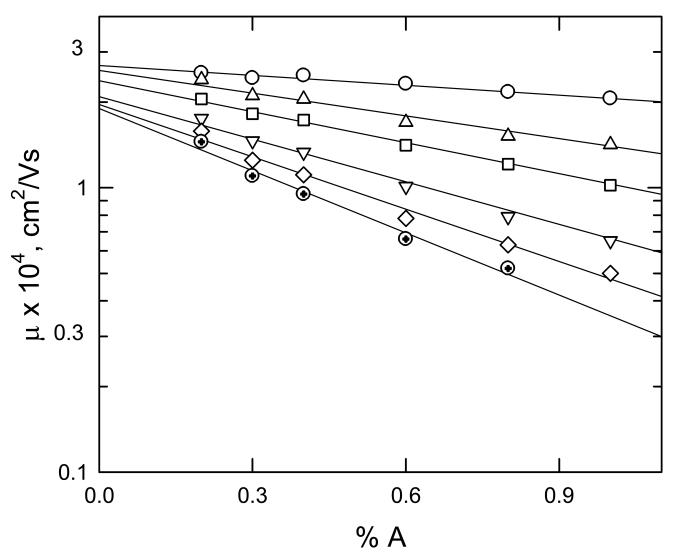

The effective pore size of agarose gels has been estimated by a variety of techniques. One common method is based on measuring Ferguson plots for DNA molecules of different sizes; typical Ferguson plots obtained for DNAs ranging from 0.5 to 12.2 kbp in size are illustrated in Fig. 1 [46]. The Ferguson plots are linear, indicating that electrophoresis is taking place in the Ogston sieving regime. Under such conditions, the median pore radius of the gel in which the mobility of the DNA is reduced to one-half its mobility at zero gel concentration can be taken as equal to the DNA radius of gyration [20,46-48]. Analysis of the Ferguson plots in Fig. 1 indicates that the median pore radius of a 1% agarose gel is ∼100 nm [46]; similar values have been obtained in a variety of other studies [47-50]. However, the gel pore radius of a 1% agarose gel estimated from lattice models of DNA gel electrophoresis is ∼2-fold smaller [20,51]; the gel pore radius determined by atomic force microscopy (AFM) is ∼2-fold larger [52]. One could argue that the average gel pore size determined by AFM is more realistic, since the values determined by electrophoretic methods only represent the pores that are accessible to the migrating DNA molecules. However, these effective gel pore radii may be the relevant ones for interpreting gel electrophoresis experiments. Studies have shown that the average agarose gel pore radius increases with increasing buffer concentration [52] but is independent of the buffer in which the gel is cast [48].

Fig. 1.

Ferguson plots observed for dsDNA fragments of different sizes. The logarithm of the mobility, μ, is plotted as a function of agarose concentration, %A. At each gel concentration, the mobilities were measured as a function of electric field strength and extrapolated to E = 0. From top to bottom, the sizes of the DNAs are: 0.5, 1.6, 3.1, 6.1, 9.2, and 12.2 kbp. Adapted from Ref. [46], with permission.

3.3. Electroosmotic flow

As described above, the agarose gel matrix is negatively charged because of covalently attached sulfate, carboxylate and/or pyruvate groups. These negatively charged residues are surrounded by positively charged counterions from the buffer. When an electric field is applied, some of the cations in the diffuse double layer near the gel fibers migrate toward the cathode, carrying along buffer and solvent molecules. The net result is a flow of the solvent toward the cathode, called the electroosmotic flow (EOF). DNA molecules are negatively charged and migrate in the opposite direction, i.e., toward the anode. Hence, the observed mobility of DNA in agarose gels is the algebraic sum of two effects, as shown in Eq. (3):

| (3) |

Many types of agarose are commercially available; the difference between them depends primarily on the number of charged residues on the agarose gel fibers. For this reason, the EOF varies from one type of agarose to another. The EOF can significantly impact the separation of very large DNA molecules, because the EOF mobility remains constant while DNA mobility decreases markedly with increasing molecular mass [48]. Some types of agarose have been hydroxyethylated to decrease the melting and gelling temperatures [31]; hydroxyethylation does not affect the EOF [48].

3.4. Separation of linear double-stranded DNA in unidirectional electric fields

The electrophoretic mobility observed for linear double-stranded (ds) DNAs in unidirectional electric fields depends on the magnitude of the electric field applied to the gel, as shown in Fig. 2. This effect is particularly important for large DNA molecules electrophoresed in concentrated agarose gels [46,53]. For example, the mobility of a DNA molecule containing 12.2 kbp increases 2.5-fold in a 1.5% agarose gel when the electric field strength is increased from 0.64 to 3.8 V/cm; the mobility of a 0.5 kbp fragment increases by ∼20% under the same conditions (compare Figs. 2A and 2B). Increases of ∼20% are observed for both DNAs in 0.2% agarose gels. The dependence of DNA mobility on electric field strength causes the Ferguson plots to become nonlinear at high gel concentrations [46].

Fig. 2.

Log-log plots of the dependence of the mobility, μ, observed in agarose gels of various concentrations on DNA molecular mass, in kilobase pairs, at two different electric field strengths. (A) 3.8 V/cm; (B), 0.64 V/cm. From top to bottom, the agarose gel concentrations are 0.2%, 0.4%, 0.6%, 0.9%, 1.25%, and 1.5%. Adapted from Ref. [53], with permission.

The dependence of DNA mobility on electric field strength can be attributed in part to the orientation of the agarose gel fibers and fiber bundles in the electric field. Agarose gel fibers have permanent dipole moments [54] and therefore interact with the electric field [54]; orientation occurs because the gel fibers are held together only by noncovalent hydrogen bonds [54,55]. The macroscopic orientation of the agarose gel fibers has been visualized directly by pre-electrophoresing an agarose gel in the direction perpendicular to the eventual direction of electrophoresis [56]. When the samples are loaded and electrophoresis is carried out in the parallel direction, linear DNA molecules travel in lanes skewed toward the side of the gel, as though orientation of the gel fibers had created pores or channels in the perpendicular direction. The lanes gradually straighten out as electrophoresis is continued, presumably because the gel fibers become reoriented in the new field direction. Lanes skewed toward the side of the gel are not observed if the gel is pre-electrophoresed in the direction in which electrophoresis will be carried out [56]. Oriented agarose gels become randomized when allowed to stand at room temperature for 24 hours, presumably because of reorganization of the hydrogen bonds in the junction zones [56]. DNA mobilities in the randomized gels are identical to those observed in gels that have not been subjected to pre-electrophoresis.

The mobilities observed for DNA molecules in agarose gels also depend on the relative size of the DNA compared with the average pore size of the gel matrix [1,25]. If the end-to-end length of the DNA is smaller than the average pore diameter (left sides of the curves in Fig. 2), the mobility decreases with the decreasing fractional volume of spaces within the gel that are available to the migrating DNA molecules. Larger DNAs migrate through the agarose gel matrix by reptation. In low voltage electric fields (Fig. 2B), the mobilities of the largest DNAs decrease approximately linearly with increasing molecular mass, as expected in the reptation without orientation regime. At higher electric fields, or for DNA molecules larger than ∼12 kbp, migration occurs in the reptation with orientation regime, as shown by the lowest curves in Fig. 2A; in this regime, the mobilities are nearly independent of molecular mass [25,53].

Direct evidence for the transition from the reptation without orientation to the reptation with orientation regimes has been observed for DNA fragments containing 622, 1426 and 2936 bp embedded in agarose gels of different concentrations, using transient electric birefringence [57]. DNA molecules embedded in agarose gels orient in a direction parallel to that of the electric field. If the median pore diameter of the gel is equal to or greater than the average end-to-end length of the DNA molecule in solution, the DNA retains its solution conformation within the gel matrix after orientation occurs. However, if the median pore diameter of the gel is smaller than the average end-to-end length of the DNA, the DNA becomes stretched as it orients in the electric field, reaching its full contour length in sufficiently concentrated gels [57-59]. DNA molecules stretched and oriented in such a manner would present a constant cross-section to the matrix and migrate with a constant mobility in the electric field.

Fluorescence videomicroscopy studies have suggested that large DNA molecules become hooked around obstacles in the agarose gel matrix during electrophoresis, leading to U-shaped conformations with the arms of the “U” pointing in the direction of the electric field [59-64]. Eventually, one of the arms of the “U” slides off the obstacle and the DNA collapses into a globular shape, before beginning the stretching and hooking process again [60-63]. Since the duration of interaction between DNA and the gel fibers is proportional to DNA length [64], DNA mobilities appear to be determined in part by interactions between the DNA molecules and the agarose gel matrix. Agarose fibers are known to bind anions [65], some of which appear to be localized near the junction zones [66]. Hence, it is not surprising that negatively charged DNA molecules interact with the agarose gel fibers during electrophoresis, probably via a dynamic association-dissociation process.

Other studies have also suggested that DNA molecules interact with the agarose gel matrix during electrophoresis. First, DNA molecules appear to form complexes with the agarose gel fibers at low sample loads; forward fronting of the DNA bands occurs at high sample loads, because the agarose binding sites have become saturated with DNA [67]. Secondly, the mobilities observed for DNA molecules of different sizes at zero agarose concentration, obtained from Ferguson plots such as those illustrated in Fig. 1, decrease with increasing DNA molecular mass, suggesting that interactions of the DNA molecules with the agarose gel matrix increase with increasing molecular mass [46]. The free solution mobility of DNA is obtained if the mobilities observed at zero agarose gel concentration are also extrapolated to zero DNA molecular mass [68]. Thirdly, DNA-agarose complexes have been observed directly by epifluorescence microscopy in melted agarose-DNA plugs [69]. In addition, DNA-agarose complexes have been observed by transient electric dichroism, using DNA molecules eluted from agarose gels after electrophoresis [70]. The enzyme agarase cannot dissolve agarose when it is complexed with DNA [69]; however, the DNA can be separated from the agarose gel fibers by diethylaminoethyl (DEAE)-cellulose column chromatography [70].

Linear dichroism studies of large DNA molecules migrating in agarose gels are consistent with the hooking and collapse process observed by fluorescence microscopy, because the initial orientation of the DNA in the electric field is greater than that observed at equilibrium [59,71-75]. The overshoot can be explained if the DNA molecules become stretched when hooked around obstacles in the gel matrix and relax back to their equilibrium conformations after sliding off the obstacles [73,76-80]. This alternating stretch and collapse process, called geometration for brevity [81], has been modeled by several authors and does not depend on specific interactions with the gel matrix; rather, the DNA chains are usually assumed to be hooked around frictionless obstacles in the gel [81-88]. However, the models do not explain why the DNA becomes compacted at its leading edge as it slides off the obstacle. It is possible that the leading edge encounters a relatively dense region in the gel which prevents further migration [83] or, alternatively, the leading edge may find an unusually large pore in the matrix which allows the DNA to collapse into a random coil conformation [84,85]. Eventually, the DNA finds a new path through the gel, either because orientation of the agarose gel fibers parallel to the electric field creates a new channel in the gel matrix [54] or because the force on the downfield gel fibers created by the mass of piled-up DNA at the leading edge distorts the matrix, allowing the DNA to migrate further into the gel [89].

3.5. Pulsed electric fields

The electrophoretic mobilities of DNA molecules larger than ∼20 kbp are nearly independent of molecular mass in unidirectional electric fields because of stretching and orientation effects [24,25,84,90]. To separate such large DNAs, pulsed electric fields must be applied to the gel. The pulsed fields may be applied intermittently in one direction [91], in opposite directions [92-97] or at obtuse angles [98,99]. Separation by molecular mass occurs because DNA molecules that are stretched and oriented in the original electric field relax toward their random coil conformations when the field is removed or changed in amplitude and/or direction; the rate at which relaxation occurs depends on DNA size [58,91]. The optimal separation window is determined by the ratio of pulse length to DNA reorientation time [100]. However, trapping effects are observed when the pulse time is close to the reorientation time [97], causing the DNA molecules to migrate in an order which is not consistent with their molecular mass [28,93,94,97].

The orientation and relaxation of large DNA molecules in pulsed electric fields has also been studied by transient electric birefringence [57,101,102] and linear dichroism [71-75]; the observed relaxation times agree with the predictions of reptation theory. In reversing electric fields, the “head” of the DNA molecule in the forward direction is usually assumed to become the “tail” in the reverse direction. However, transient electric birefringence [58] and linear dichroism [103] studies have shown that DNA orientation in the new field direction occurs via a coiled intermediate. Hence, the “head” does not necessarily become the “tail” upon field reversal; instead, another “head” appears as the DNA stretches out in the new field direction [103].

The fibers and fiber bundles in the agarose gel matrix are also oriented by pulsed electric fields of the amplitude and duration used for pulse field gel electrophoresis [54,55,104-106], most likely because the electric field catalyzes the reorganization of hydrogen bonds in the junction zones [54,55]. Surprisingly, the agarose gel fibers and fiber bundles become oriented in the perpendicular direction when the electric field is reversed in polarity [54,55]. Pulses ≥ 7 V/cm, with different durations in the forward and reverse directions, cause extensive disruption of the junction zones, allowing very large numbers of agarose fibers and fiber bundles to orient in the electric field [55,105,106]. The extensive reorientation of agarose gel fibers in reversing electric fields seems likely to create large pores in the gel matrix, allowing very large DNA molecules to migrate in the direction of the electric field with minimal conformational distortion.

3.6. Circular DNA

Supercoiled (interwound) DNA molecules have more compact conformations than linear DNAs containing the same number of base pairs, and migrate faster than linear DNA [107-110]. If the electric field is relatively low, topological isomers (topoisomers) containing different numbers of superhelical turns can be resolved into discrete bands [111-114]. Positively and negatively supercoiled topoisomers can be separated by two-dimensional electrophoresis if an intercalating agent, such as chloroquine or ethidium bromide, is added to the running buffer in one of the orthogonal directions [115]. Large open circle (relaxed) DNAs have negligible mobilities in high voltage electric fields, presumably because they are impaled by dangling fibers in the matrix [107,109,110,116,117].

The trapping of DNA open circles in agarose gels can be eliminated by reversing the direction of the electric field [109] or using pulsed unidirectional fields [110], either because changing the direction of the field allows the circles to migrate out of the trap, or because pulsed fields change the direction of orientation of the agarose gel fibers. Counterintuitively, the trapping of DNA open circles increases with decreasing agarose concentration, suggesting that the density of traps and/or the probability of entering them increases at low agarose concentrations [116,118]. In agreement with the trapping results, electron microscopy studies of freeze-fractured agarose gels have shown that the concentration of dangling ends increases with decreasing agarose concentration [119].

3.7 Branched DNA

Branched DNA molecules are those containing three or more arms emanating from one or more origins. Branched DNAs migrate more slowly than linear DNAs of equal mass because of trapping effects, which are enhanced at higher agarose concentrations and in higher electric fields [120]. However, the trapping of open circle and branched DNAs may occur by different mechanisms. Open circle DNAs appear to be impaled on agarose gel fibers [109], while the trapping observed for branched DNAs seems more likely to be cause by sieving effects. Branched and linear DNA molecules can be separated by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis if the separation in the first dimension is determined primarily by mass (low agarose concentration and low voltage), while the separation in the second dimension is determined primarily by shape (higher agarose concentration and higher voltage) [120,121].

2.8 Single-stranded DNA

Large single-stranded (ss) DNA molecules migrate by reptation in agarose gels, with mobilities that are slower than observed for double-stranded (ds) DNAs containing the same number of monomer units [122]. The reptation with orientation regime occurs at much higher molecular mass for ssDNA than for dsDNA [122], most likely because ssDNAs have a relatively low persistence length [123,124] and are flexible enough to migrate through the gel matrix without distortion. Open circle ssDNAs migrate more slowly than linear ssDNAs because of sieving and/or trapping effects; the mobility differences become more pronounced at high gel concentrations and high electric field strengths [125].

4. Polyacrylamide gels

Polyacrylamide gels, although more troublesome to cast than agarose gels, are widely used for DNA separations because of their excellent resolving power and high load capacity [28]. Depending on the composition of the gel, very small DNA oligomers or linear double-stranded DNAs ranging up to ∼ 5 kilobase pairs in size can be separated.

4.1 Polyacrylamide gel structure

Polyacrylamide gels are chemically crosslinked gels formed by the reaction of acrylamide with a bifunctional crosslinking agent such as N,N'-methylenebisacrylamide (Bis). The composition of the gel is usually described in terms of %T, the total (w/v) concentration of acrylamide plus crosslinker, and %C, the (w/w) percentage of crosslinker included in %T [126]. The free radical reaction between acrylamide and Bis is usually carried out using ammonium persulfate as the initiator and N,N,N',N'-tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED) as the catalyst. Dynamic light scattering studies have shown that the number of chains per gel depends on the initiator concentration [127], while the mass per chain increases with increasing monomer concentration [128]. Polyacrylamide gels are not uniform in structure, because Bis polymerizes with itself more rapidly than with acrylamide [129-136]. For this reason, the gels contain highly crosslinked, Bis-rich nodules linked together by more lightly crosslinked, relatively acrylamide-rich fibers [130,135,136]. Polyacrylamide gels contain no charged residues, so that electroosmosis is not observed; however, pre-electrophoresis is required to remove polar impurities that can bind to DNA [137].

4.2 Apparent gel pore size

The effective pore size of polyacrylamide gels depends on the size of the analyte and on the method used to determine the pore size. Ferguson plot methods using proteins as the analyte measure the apparent pore size in the Bis-rich nodules [17,138]. Larger analytes such as DNA, which do not “see” the small pores in the nodules, are retarded by migration through the acrylamide-rich gel fibers and report on the apparent pore size in this portion of the matrix. Typical Ferguson plots observed for DNA molecules migrating in polyacrylamide gels containing 3%C and various %T are illustrated in Fig. 3. Analysis of the Ferguson plots obtained in gels containing 3.5% to 10.5% T and 1% to 5%C indicates that the apparent pore radius decreases from 140 to 20 nm with increasing %T and %C [138-140]. The apparent gel pore radius decreases as the square root of gel concentration [140,141], as predicted by the Ogston sieving [14-17] and biased reptation [19,20] theories. The apparent gel pore radius is independent of the casting buffer [137], as observed for agarose gels [48].

Fig. 3.

Ferguson plots observed for dsDNA fragments in polyacrylamide gels containing 3.0%C and various %T. From top to bottom, the sizes of the DNAs are: 123, 246, 369, 615, 984, and 1599 bp. Adapted from Ref. [139], with permission.

Non-electrophoretic methods have also been used to estimate polyacrylamide gel pore size. Scanning and transmission electron microscope studies have indicated that the average pore radius is ∼100 nm for gels containing 5%T and 2.7% C [128,142,143], similar to the value obtained by Ferguson plot methods [140] (but see [144] for a contrary view). NMR relaxation experiments [145] have suggested that the average pore radius of a 5%T, 3% C gel is ∼8 nm, possibly because the NMR method measures an average of the nodule and gel fiber pore radii.

4.3 Separation of linear double-stranded DNA in unidirectional electric fields

The mobilities of dsDNA molecules larger than ∼2-3 kilobase pairs (kbp) decrease linearly with increasing molecular mass [137,139], indicating that large DNAs migrate though the polyacrylamide gel matrix by reptation [21,22]. Smaller DNA molecules exhibit linear Ferguson plots, as shown in Fig. 3, indicating that they are migrating in the Ogston sieving regime [136]. The Ogston theory predicts that the observed mobilities should converge to the same value at zero gel concentration [14-17], since the free solution mobilities of DNA molecules in this size range are independent of molecular mass [11,12]. However, as shown in Fig. 3, the mobilities observed at zero gel concentration decrease significantly with increasing DNA molecular mass If the mobilities observed for the various DNA fragments at zero gel concentration are also extrapolated to zero DNA molecular mass, the resultant value is equal to the free solution mobility of DNA [68,139]. Hence, DNA molecules are retarded in polyacrylamide gels by a molecular mass-dependent mechanism that occurs in addition to Ogston sieving. This additional retardation mechanism is most likely the transient interaction of the migrating DNA molecules with the polyacrylamide gel fibers during electrophoresis [68,139,140,146]. Several theoretical treatments of DNA gel electrophoresis have also indicated that the mobilities observed for DNA in polyacrylamide gels can only be rationalized by postulating an interaction between the DNA and the gel fibers [147-149]. In agreement with these results, transient electric birefringence studies have shown that DNA molecules recovered from polyacrylamide gels after electrophoresis are complexed with polyacrylamide gel fibers; the DNA can be separated from the gel fibers by DEAE-cellulose column chromatography [70].

4.4 Curved DNA molecules

One of the major differences between DNA separations in agarose and polyacrylamide gels is that the mobilities observed in polyacrylamide gels depend on DNA sequence [137,150], while the mobilities observed in agarose gels do not [151]. Certain DNA molecules migrate anomalously slowly in polyacrylamide gels, i.e., slower than expected from their known molecular mass. Fluorescence electron microscopy studies [152,153], as well as transient electric birefringence and dichroism experiments [154-158], have shown that the anomalously slowly migrating DNA molecules are bent or curved. Since curved DNA molecules have shorter end-to-end lengths and larger cross-sectional areas than normal fragments containing the same number of base pairs, curved DNAs require larger pores to migrate through the gel matrix, behaving electrophoretically as though they were larger than their true size [139,150,159]. Based on this argument, sieving effects would appear to be responsible for the mobility anomalies.

However, if sieving effects were the only factor contributing to the DNA mobility anomalies, the mobility anomalies should be independent of the method used to vary the gel pore size. Two methods can be used to vary the polyacrylamide gel pore size: changing %T at constant %C, the usual method of changing the pore size, or changing %C at constant %T. When the gel pore size is increased by decreasing %T at constant %C, the mobility anomalies decrease progressively with increasing gel pore radius [139,146,150,160,161]. However, when the gel pore size is increased by decreasing %C at constant %T, the mobility anomalies are independent of gel pore radius as long the pore radius is greater than the radius of gyration of the migrating DNA molecules [146]. For DNAs larger than the average gel pore radius, the mobility anomalies decrease with increasing gel pore radius until the pore radius becomes larger than the DNA radius of gyration, after which the mobility anomalies level off and become independent of gel pore radius. The combined results indicate that preferential interactions of curved DNA molecules with the polyacrylamide gel matrix, as well as sieving effects, are responsible for the mobility anomalies [146]. The anomalously slow mobilities observed for curved DNA molecules persist even at zero gel concentration [161], because curved DNAs also migrate anomalously slowly in free solution, as will be described below.

4.5 Circular DNA

Closed circular DNA molecules containing different numbers of superhelical turns exhibit different mobilities in polyacrylamide gels [162,163]. Relaxed or open circle DNAs migrate with the slowest mobility; the mobilities of supercoiled DNAs increase with the increasing number of superhelical turns. However, for relatively large circles or relatively high gel concentrations, the mobilities of topoisomers with the same number of superhelical turns do not increase monotonically with increasing molecular mass, suggesting that large circles can be compacted by the gel matrix [163]. Circle compaction is particularly evident for topoisomers with low supercoil densities.

Linear dichroism studies have shown that large DNA circles are trapped and become immobile in high voltage unidirectional electric fields, presumably because of the impalement of the circles on dangling ends of the gel fibers [164] and/or to entrapment in constricted “dead-ends” in the gel matrix [115,165]. In low voltage unidirectional electric fields, DNA circles migrate in broad smeary zones, suggesting that different DNAs are retarded to a different extent by trapping effects [164,165]. In pulsed reversing fields, relaxed and supercoiled DNAs migrate as sharp bands, indicating that the trapping effects are reversible. Surprisingly, open circle DNAs tend to be oriented perpendicular to the direction of the electric field in low voltage electric fields, opposite to the direction of orientation in high fields. Perpendicular orientation of DNA circles in low voltage electric fields may be due to the absence of a leading edge that can penetrate the gel matrix; various portions of the open circle may be attempting to orient in the electric field at the same time.

4.6 Branched DNA

The mobilities of branched DNAs containing three or more arms of equal size (stars) are equal to those of linear DNAs containing the same number of base pairs if the arms are relatively short and the gel pore size is relatively large [136]. The mobilities of DNA stars are also independent of the number of arms, as long as the total number of base pairs is held constant. However, the mobility decreases with the increasing number of arms if arms of constant size are added to the DNA backbone, or if one of the arms is increased in length [136,166,167]. The results can be explained in part by sieving effects, since branched DNA molecules with more arms and/or longer arms would require larger pores to migrate through the gel matrix [136,166]. However, the constancy of the mobility of linear DNAs with stars containing variable numbers of arms, when the total molecular mass is held constant, suggests that the retardation mechanism also includes interactions of the DNA with the polyacrylamide gel fibers [136].

Branched DNA molecules can also be created by the denaturation of AT-rich regions in large DNA molecules. Partial denaturation changes a linear DNA molecule into one with an internal bubble or a branched structure, depending on whether melting occurs in the middle or at one end of the DNA [168,169]. Partially melted DNAs migrate much more slowly through the polyacrylamide gel matrix than the parent duplexes or the individual single strands [168,169], enabling the rapid identification of the least stable domain(s) in the DNA [170]. Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis is usually carried out with polyacrylamide gels cast in a linear gradient of a chemical denaturant, or in temperature gradients parallel or perpendicular to the direction of the electric field [170]. The mechanism of retardation of partially melted DNAs is usually attributed to Ogston sieving, although the effect of chemical denaturants on gel porosity may also be important [170,171].

4.7 Single-stranded DNA

Small single-stranded oligomers containing the same number of nucleotides exhibit highly variable mobilities in native and denaturing polyacrylamide gels. The order of migration of mononucleotides and small homopolymers of the same length varies with oligomer size and depends on the identity of the nucleotide [172,173]. Since the mobility differences reflect base composition rather than sequence [173], the individual DNA bases appear to interact differently with the polyacrylamide gel matrix during electrophoresis. Because of this effect, different mobilities are observed for the complementary strands of oligomers containing alternating AT and GC bases [174], and the mobilities observed for DNA fragments in sequencing gels depend on the identity of the terminal nucleotide [175].

Small, mixed-sequence oligomers do not exhibit composition-dependent mobilities, because differences in the intrinsic mobilities of individual nucleotides are averaged out in the oligomers. However, the mobilities of mixed-sequence oligomers containing the same number of nucleotides can and do vary because of hairpin formation [176,177]. Hairpins have more compact conformations than random coils and have lower frictional coefficients, increasing the observed mobility. If mixed-sequence oligomers of the same size are in their random coil conformations, e.g., at high temperatures or in solutions containing urea or other chemical denaturants, they have identical mobilities [176,177]. Large, essentially random-sequence ssDNAs exhibit mobilities that decrease approximately linearly with increasing molecular mass, suggesting that they are migrating through the gel by reptation [178]. However, the observed mobilities increase with increasing electric field strength for ssDNAs >1000 bases in length [145], suggesting that molecules in this size range are migrating in the reptation with orientation regime.

4.8. Charged polyacrylamide gels

Although the polyacrylamide gel matrix is normally uncharged, charged residues can be deliberately added during the polymerization process. Copolymerizing acrylamide with acrylic acid creates a negatively charged matrix; copolymerizing with allyltriethylammonium bromide (ATAB) creates a positively charged matrix [159]. DNA mobilities are significantly reduced in gels containing 0.04% to 0.13% acrylic acid (w/v) because of the increased electroosmotic flow in the negatively charged matrix. The mobilities are also significantly reduced in gels containing 0.2 - 0.4 μM ATAB, because the DNA molecules are retarded by interacting with the positively charged gel fibers [159].

Positively charged polyacrylamide gels can also be made by adding millimolar concentrations of basic Immobilines (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) during polymerization [179]. If the gel contains a concentration gradient of basic Immobilines, large DNA fragments will be arrested in the portion of the gel containing a relatively small concentration of immobilized charges, while smaller fragments will migrate further into the gel and be immobilized there by the higher density of charged residues there [179]. Immobiline gradient gels are able to separate ssDNA oligomers containing 656 and 659 nucleotides, as well as 35-base oligomers with different sequences [179]. Such gels may be useful for analyzing single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in genomic DNA.

5. Capillary electrophoresis

The capillary electrophoresis of DNA is usually carried out in buffers containing entangled hydrophilic polymers that act as the sieving medium. Capillary electrophoresis offers significant advantages over slab gel DNA separations, because of higher resolution, greater speed, on-line detection, and the minimal use of samples and buffers. However, capillary electrophoresis also has several disadvantages, such as the fragility of the capillaries and capillary coatings and the necessity of running one sample at a time in each capillary to obtain accurate mobilities. Mulicapillary systems can be used to increase throughput, but they are relatively expensive to purchase and operate.

5.1. Capillary coatings and the control of electroosmotic flow

Capillary electrophoresis experiments are carried out in fused silica capillaries with a high surface area/volume ratio. At neutral pH, where DNA separations are usually carried out, the silanol residues on the capillary wall are negatively charged and attract positively charged counterions from the buffer, creating an electric double layer next to the wall. When an electric field is applied, the cations in the diffuse portion of the double layer migrate toward the cathode, carrying along buffer and solvent. The resulting electroosmotic flow (EOF) affects the observed mobility, as shown by Eq. (3). The EOF can also transport the sieving matrix out of the capillary, degrading the separation [180]. As a result, control of the EOF is essential for obtaining reproducible results.

Two types of capillary coatings are commonly used to minimize the EOF. The first involves covalent modification of the capillary wall by attaching neutral hydrophilic polymers to the silanol residues [181-183]. Covalently coated capillaries are useful for studies of the physical properties of DNA because the EOF mobility is very low [12]; however, the lifetime of the coating is often rather short because of hydrolytic cleavage of the siloxane bridges. The second common method of reducing the EOF is to add to the buffer a small molecule that adheres to the capillary wall; this method is called dynamic coating [180,183]. Dynamic coatings are convenient because they are renewed every time the capillary is filled with buffer. Some polymers, such as poly-N,N'-dimethylacrylamide (pDMA), adsorb to the capillary wall and have good bulk sieving properties, so they function both as capillary coatings and as the sieving matrix [5,180,184-186].

5.2. Separation matrices

Many different polymers have been investigated as separation matrices, including liquefied agarose, cellulose derivatives, dextrans, linear polyacrylamides and their derivatives, poly(ethylene oxides), and polyvinyl alcohols. The solution properties of these polymers are described elsewhere [184,187-196]. Most of the polymers provide good separations in certain DNA molecular mass ranges [184,187,197]. For polymers of comparable molar mass, hydrophilic polymers form more highly entangled networks because each molecule occupies a relatively large volume in the solution [188]. The mesh size of the entangled polymer should be of the same order of magnitude as the radii of gyration of the migrating DNA molecules, so that DNA-polymer interactions do not disrupt the polymer-polymer entanglements and locally destroy the polymer network [184,187,188]. Hence, large DNA molecules are most efficiently separated in relatively dilute solutions of high molar mass polymers, while small DNA fragments are better resolved in concentrated solutions of low molar mass polymers [193,198]. Mixtures of polymers with different molecular masses are often used to increase the range of the molecular mass separations [184,187,191,193,199-201].

5.3 DNA separations in entangled polymer solutions

One of the major differences between DNA separations in slab gels and entangled polymer solutions is that the entangled polymers are free to move about in the solution [202], creating dynamic pores in the matrix as they change interacting partners. The movements of the polymer chains give rise to a process called constraint release, which increases the mobility of the DNA [203-206].

Current theories of DNA electrophoresis are unable to rationalize the mobilities and diffusion coefficients observed in polymer solutions at concentrations above and below the entanglement threshold, possibly because the theories do not include coupling of the DNA motions with those of the polymer chains [184,202,205,207,208]. Non-entangling collisions between DNA and the polymer molecules also appear to be important, especially with low molar mass polymers, because the collisions impart a drag force that varies with DNA size [209]. In addition, entangled polymer chains close to the migrating DNA molecules undergo unusual collective hydrodynamic effects, which are not understood [210].

5.3.1. Linear double-stranded DNA

DNA separations in solutions containing different types of entangling polymers are qualitatively similar, suggesting a common mechanism of separation. As an example, log-log plots of the mobilities observed for dsDNA in entangled pDMA solutions [190] are illustrated in Fig. 4A. Three zones of separation can be observed: Ogston sieving for small DNA molecules, an intermediate region where reptation takes place and the mobility decreases approximately linearly with increasing molecular mass, and the reptation with orientation regime at high molecular mass, where the mobility is nearly constant and separation is poor [5, 190]. Transient electric birefringence studies have confirmed the existence of the three regimes [211]. Ferguson plots of the mobilities observed in entangled hydroxyethylcellulose (HEC) solutions indicate that the mobilities observed at zero polymer concentration decrease with decreasing DNA molecular mass [212], consistent with an interaction between the sieving matrix and the migrating DNA molecules.

Fig. 4.

Log-log plots of the dependence of the mobility, μ, observed in poly-N,N'-dimethylacrylamide (pDMA) solutions of various concentrations on DNA size. (A), dsDNA, 25°C; (B), ssDNA, 50°C with 4M urea. From top to bottom, the pDMA concentrations are 1%, 2%, 5%, and 10%. Adapted from Ref. [5] with permission.

Fluorescence microscopy studies of large DNA molecules in entangled polymer solutions indicate that the DNA migrates in wide U-shaped structures with the arms of the “U” preceding the apex [203,204,213-215]. Hence, the migrating DNA molecules appear to be trapped by obstacles in the entangled polymer matrix, as observed in slab gels. Since W-shaped structures are not observed, each DNA molecule appears to be trapped at a single point in the matrix [203]. As electrophoresis proceeds, the arms of the “U” become stretched and elongated until one arm eventually begins to retract, allowing the DNA to slide off the obstacle [203]. DNA density in the U-shaped conformation is greatest at the tips of the arms [184,203,214], suggesting that the DNA “piles up” at the tips until the mass of one of the arms becomes great enough to push the downfield polymers aside. When the direction of the electric field is reversed, the U-shaped DNA molecules collapse into a globular shape before extending into another U-shaped conformation in the new field direction [216].

The U-shaped DNA structures migrate downfield during the stretching and retraction process, suggesting that the DNA molecules drag the polymer chains with them during electrophoresis [203,213,214]. However, the velocity of the apex of the “U” varies randomly from one DNA molecule to another [203,217], suggesting either that the entangling polymer matrix is not homogeneous [203] or that different DNA molecules drag different numbers of polymer chains with them. Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) studies have shown that DNA molecules drag dextran chains with them during electrophoresis [210]; presumably other hydrophilic polymers can be dragged by the DNA as well. The mobilities of the DNA-polymer complexes decrease with increasing DNA size and polymer concentration, suggesting that the stoichiometry of the complex depends on these variables.

Megabase-sized DNA molecules migrating in concentrated polyacrylamide solutions are linear in shape instead of exhibiting wide U-shapes [214]. Regions with high segment density migrate with a constant velocity in the electric field, suggesting that the entangling polymer chains remain at fixed positions on the DNA during electrophoresis [214]. When an alternating 120° electric field is applied to the solution, multiple kinks form and begin to grow in the new field direction [218]. Eventually, the kink at the trailing end becomes dominant and the DNA resolves into a linear shape in the new field direction. The apex of the kinked structure does not move when the direction of the electric field is changed, suggesting that the DNA-polymer complex is trapped and immobile during reorientation [218].

5.3.2 Supercoiled DNA

Supercoiled DNA molecules migrate more slowly in entangled polymer solutions than linear DNAs containing the same number of base pairs and the peaks are much broader, suggesting that the migration dynamics are different [219,220]. Fluorescence microscopy studies have shown that supercoiled DNAs do not form the characteristic U-shaped structures observed for linear DNAs [219], most likely because the interwound chains are too stiff to be trapped by entangled linear polymers [220]. Instead, the supercoiled DNAs grow linearly after apparently random collisions with the matrix; as migration proceeds, the DNA conformation oscillates between partially extended and compact conformations [219]. If the conformation varies randomly from one collision to another, different topoisomers with the same supercoil density could have different average dimensions and migrate with different average mobilities, explaining the broad peaks observed during electrophoresis [219]. Alternatively, the broad peaks observed in entangled polymer solutions could reflect the unresolved mobilities of topoisomers with different supercoil densities.

5.3.3 Branched DNA

Branched DNA molecules (stars) migrating in entangled polymer solutions exhibit conformations similar to the U-shaped conformations observed for linear DNA [221]. The arms of the star are extended in the direction of the electric field, dragging the common branch point behind; the resulting fluorescence microscopy images are reminiscent of a squid moving backward. The arms of the star gradually retract as electrophoresis proceeds, giving rise to U- and J-shaped structures that eventually collapse into a globular conformation as the arms become disentangled from the matrix [221].

5.3.4 Single-stranded DNA

The separation of ssDNA molecules in entangled polymer solutions is similar to that observed for duplex DNAs, as shown in Fig. 4B. Three separation regimes are observed: the Ogston sieving regime for small DNAs, the reptation without orientation regime for DNAs of intermediate size, and the reptation with orientation regime for large DNAs [5,190]. The resolution of single-stranded DNA in the reptation without orientation regime is greater than observed for duplex DNAs containing the same number of residues, as indicated by the greater slopes of the mobility plots in the intermediate region (compare Figs. 4A and 4B).

5.4 Ultradilute polymer solutions

DNA molecules can also be separated in polymer solutions significantly more dilute than the threshold overlap concentration [222-225]. Uncoated capillaries are usually used with ultradilute polymer solutions, because the electroosmotic flow of the solvent increases the residence time of DNA in the capillary, effectively increasing the capillary length [224]. DNA mobilities decrease smoothly with increasing polymer concentration above and below the threshold overlap concentration, as shown in Fig. 5, indicating that DNA separations in hydrophilic polymer solutions do not require the presence of a pseudo matrix [209,223,225].

Fig. 5.

Dependence of the mobility, μ, observed for dsDNA on the concentration of hydroxypropyl cellulose (HPC) in the solution. The threshold overlap concentration, Φ*, is indicated. From top to bottom, the DNA increases in size from 72 to 23130 bp. Adapted from Ref. [225] with permission.

A new separation mechanism, called transient entanglement coupling, has been proposed to explain the molecular mass separations observed in ultradilute polymer solutions [205,222-225]. Individual polymer chains are proposed to become entangled with the DNA molecules, forming transient complexes that migrate downfield during electrophoresis. Separation is observed because the rates of collision and disentanglement of the polymer chains depend on DNA size [205,226,227]. However, the resolution is relatively poor, because the mobility differences observed for DNA molecules of different sizes are relatively small in ultradilute polymer solutions (compare Fig. 5 with Fig. 4A).

Fluorescence videomicroscopy studies are consistent with the transient entanglement coupling mechanism. DNA molecules form similar U- and J-shaped structures in polymer solutions above and below the overlap concentration, suggesting that the separation mechanism is similar in both concentration regions [203,209,226,228]. However, in ultradilute polymer solutions, the arms of the U-shaped and J-shaped structures are relatively short [203,228], suggesting that relatively few polymer chains are entangled with the DNA molecules. U- and J-shaped structures are not observed with low molar mass polymers; instead, the DNA molecules migrate as globular random coils [209]. Since molecular mass separation is observed even under these conditions, non-entangling encounters between the DNA and polymer chains must also retard the migration of the DNA molecules [209].

5.5. Thermoresponsive polymer solutions

Polymer matrices with temperature-dependent viscosities enable the capillary to be filled with a low-viscosity solution while allowing the separation to take place in a viscous, highly entangled polymer solution [229]. Typical thermoresponsive matrices are block copolymers containing moderately hydrophobic residues in one of the blocks; the hydrophobic groups either phase-separate or aggregate at high temperatures to form the entangled matrix [189,229]. One commercially available block copolymer, called Pluronic F127™ (BASF Performance Chemicals, Mount Olive, NJ, USA), is composed of alternating poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) and poly(propylene oxide) (PPO) blocks. Pluronic F127 solutions exist in a liquid-crystalline phase at temperatures above ∼20°C; the spherical micelles present in this phase have a dense PPO core surrounded by a “brush” of extended PEO chains [189,229-231].

Pluronic liquid crystalline solutions can be used to separate single-stranded, double-stranded and supercoiled DNA molecules [230-234], with exceptional resolution in some cases [234]. Since the DNA molecules cannot penetrate the hydrophobic PPO cores, it has been suggested that sieving occurs as the DNAs migrate through the PEO brushes [231,233]. However, comparison of the orientation of linear and circular DNAs in Pluronic gels suggests that migration may instead occur in the interstitial spaces between microcrystalline domains [235,236]. Linear dichroism studies have suggested that DNA molecules electrophoresed in Pluronic gels are oriented with their helix axes perpendicular to the direction of the electric field [235,236], opposite to the direction of orientation observed in other sieving media. In high electric fields, the liquid crystalline structure of the Pluronic gels appears to be disrupted by the migrating DNA molecules, giving rise to anomalously fast mobilities [236].

6. Free solution, no matrix

The free solution mobility of DNA is assumed to be independent of molecular mass, because the charge per unit mass is essentially constant. However, this assumption is incorrect for small DNA molecules, as shown by the closed circles in Fig. 6. The mobility of DNA increases with increasing molecular mass before leveling off at a constant plateau value for DNAs larger than ∼400 bp [11,12,237]. Since an increase in mobility with increasing molecular mass is predicted theoretically for stiff polyelectrolytes [238,239], small DNA molecules appear to migrate as rigid rods in the electric field. DNAs larger than ∼200-400 bp begin to adopt a random coil conformation and act as free-draining coils, with the mobility dependent only on the charge/friction ratio [11,12,237,240].

Fig. 6.

Dependence of the free solution mobility, μ, of curved (open circle) and normal (closed circle) DNA molecules on DNA molecular mass, in base pairs. Adapted from Ref. [241] with permission.

Some DNA molecules containing the same number of base pairs migrate anomalously slowly in free solution, as shown by the open circles in Fig. 6 [241]. The variable mobilities observed for these DNAs can be attributed to differences in shape and effective charge. Transient electric birefringence measurements have shown that the anomalously slowly migrating DNA molecules are stably curved [158] and therefore would have lower frictional coefficients than normal DNAs containing the same number of base pairs [242]; this effect would be expected to increase the observed mobility. However, the curved DNAs also contain A-tracts, runs of four or more contiguous adenine residues. DNA A-tracts are known to bind monovalent cations in solution [243-246] and in crystals [247,248]. Since the buffers used for electrophoresis typically contain Na+ or Tris+ ions, preferential cation binding to the A-tracts would decrease the effective charge of the curved DNAs, reducing their mobilities. The difference in effective charge is apparently more important than the difference in shape, because the mobilities of the curved, A-tract-containing DNAs (open circles) are lower than observed for non-curved, non-A-tract-containing DNAs of the same molecular mass (closed circles) [242].

A-tract-containing DNA oligomers that are too small to exhibit curvature also migrate anomalously slowly in free solution. For example, oligomers containing twelve A-T base pairs migrate more slowly than oligomers containing twelve G-C base pairs [249,250], and 20 bp oligomers containing A-tracts migrate more slowly than 20 bp oligomers without A-tracts [243]. These results provide further evidence for the binding of monovalent cations to DNA A-tracts, reducing the effective charge and thus reducing the observed mobility.

7. Concluding remarks

This review has summarized the results obtained to date on the effect of a sieving matrix (or no matrix) on DNA electrophoretic mobility. While all separations in sieving matrices have features in common, the actual separations depend on the relative size of the DNA with respect to the effective pore size of the matrix, and on specific features of the matrix itself. The separations observed for DNA in agarose gels are quite different from those observed in polyacrylamide gels, in part because the agarose gel fibers become oriented in the electric field, giving rise to relatively broad bands that are insensitive to small mobility differences between samples. Chemically crosslinked polyacrylamide gels offer much higher resolution, allowing small mobility differences, even between conformational isomers of the same DNA [251,252], to be observed. Electrophoresis in entangled linear polymer solutions has the added feature that the entire matrix is mobile, allowing individual polymer chains to become entangled with each other and with the migrating DNA molecules. The sieving effects of the various matrices makes possible the separation of DNA by molecular mass and conformation; the observed mobilities also reflect the intrinsic mobilities of the DNAs in free solution and specific interactions of the DNA molecules with the matrix.

Videofluorescence microscopy studies and electro-optic measurements of DNA in slab gels and hydrophilic polymer solutions have added to our understanding of the electrophoresis process and the contribution of the matrix to the observed separations. However, several outstanding questions remain. No one as yet has observed the migration of labeled DNA molecules in labeled polymer solutions by fluorescence microscopy, so that the number of polymer chains entangled with each DNA molecule and the effect of the electric field on the entanglement and disentanglement of the DNA and polymer chains could be determined directly. Similar experiments with labeled DNA molecules in labeled slab gels would also be enlightening. The unusual collective dynamics of entangled polymer chains [206] and agarose gel fibers [55] in the electric field, and electrohydrodynamic instabilities leading to the aggregation of very large DNA molecules in free solution [253-256], most likely also affect the separations; however, none of these effects are well understood.

On another front, most theoretical treatments of DNA electrophoresis have focused on the migration of double-stranded DNA in agarose gels and single-stranded DNA in polyacrylamide gels, primarily because the persistence length of the DNA is similar to the mean pore size of the gel matrix in these two cases. The separation of double-stranded DNAs in polyacrylamide gels (the “tight gel” case) has received less attention [25,148], and DNA separations in ultradilute and entangled polymer solutions are still incompletely understood. It is hoped that recent molecular dynamics simulations of polymer-DNA collisions in ultradilute polymer solutions [257] and semiphenomenological studies of DNA electrophoresis in artificial gel matrices [87,88] will lead to an improved understanding of DNA separations in all types of sieving matrices.

Acknowledgments

Partial financial support of the work in the authors' laboratory by grants GM29690 and GM61009 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and grant CHE-0748271 from the Analytical and Surface Chemistry Program of the National Science Foundation (to N.C.S.) is gratefully acknowledged. Helpful comments from the reviewers are also acknowledged.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Viovy J-L. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2000;72:813. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Upcroft P, Upcroft JA. J. Chromatogr. 1993;618:79. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(93)80028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slater GW, Guillouzic S, Gauthier MG, Mercier J-F, Kenward M, McCormick LC, Tessier F. Electrophoresis. 2002;23:3791. doi: 10.1002/elps.200290002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slater GW, Kist TBL, Ren H, Drouin G. Electrophoresis. 1998;19:1525. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150191003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heller C. Electrophoresis. 2001;22:629. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200102)22:4<629::AID-ELPS629>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Righetti PG, Gelfi C, D'Acunto MR. Electrophoresis. 2002;23:1361. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200205)23:10<1361::AID-ELPS1361>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stellwagen NC. In: Advances in Electrophoresis. Chrambach A, Dunn MJ, Radola BJ, editors. Vol. 1. VCH; New York: 1987. pp. 177–228. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimm BH, Levene SD. Q. Rev. Biophys. 1992;25:171. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500004662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slater GW, Desruisseaux C, Hubert SJ, Mercier J-F, Labrie J, Boileau J, Tessier F, Pépin MP. Electrophoresis. 2000;21:3873. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200012)21:18<3873::AID-ELPS3873>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sartori A, Barbier V, Viovy J-L. Electrophoresis. 2003;24:421. doi: 10.1002/elps.200390052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olivera BM, Baine P, Davidson N. Biopolymers. 1964;2:245. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stellwagen NC, Gelfi C, Righetti PG. Biopolymers. 1997;42:687. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(199711)42:6<687::AID-BIP7>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fawcett JA, Morris CJOR. Sep. Sci. 1966;1:9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogston AG. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1958;54:1754. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodbard D, Chrambach A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1970;4:970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.65.4.970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chrambach A, Rodbard D. Science. 1971;172:440. doi: 10.1126/science.172.3982.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tietz D. In: Advances in Electrophoresis. Chramback A, Dunn MJ, Radola BJ, editors. Vol. 2. VCH; New York: 1988. pp. 109–169. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferguson KA. Metabolism. 1964;13:985. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(64)80018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slater GW, Guo HL. Electrophoresis. 1996;17:977. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150170604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slater GW, Guo HL. electrophoresis. 1996;17:1407. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150170903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lerman LS, Frisch HL. Biopolymers. 1982;21:995. doi: 10.1002/bip.360210511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lumpkin OJ, Zimm BH. Biopolymers. 1982;21:2315. doi: 10.1002/bip.360211116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lumpkin OJ, Dejardin P, Zimm BH. Biopolymers. 1985;24:1573. doi: 10.1002/bip.360240812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hervet H, Bean CP. Biopolymers. 1987;26:727. doi: 10.1002/bip.360260512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Semenov AN, Duke TAJ, Viovy J-L. Phys. Rev. E. 1995;51:50. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Southern EM. Anal. Biochem. 1979;100:319. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90235-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heller C, Duke T, Viovy J-L. Biopolymers. 1994;34:249. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular Cloning. 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rees DA, Morris ER, Thom D, Madden JK. In: Polysaccharides. Aspinall GO, editor. Vol. 1. Academic Press; New York: 1982. pp. 196–290. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Serwer P. Electrophoresis. 1983;4:375. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirkpatrick FH. In: Electrophoresis of Large DNA Molecules: Theory and Applications, Current Communications in Molecular Biology. Lai E, Birren BW, editors. Vol. 1. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Plainview, NY: 1990. pp. 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dea ICM, McKinnon AA, Rees DA. J. Mol. Biol. 1972;68:153. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(72)90270-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arnott S, Fulmer A, Scott WE, Dea ICM, Moorhouse R, Rees DA. J. Mol. Biol. 1974;90:269. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(74)90372-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norton IT, Goodall DM, Austen KRJ, Morris ER, Rees DA. Biopolymers. 1986;25:1009. [Google Scholar]

- 35.San Biagio PL, Madonia F, Newman J, Palma MU. Biopolymers. 1986;25:2255. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pines E, Prins W. Macromolecules. 1973;6:888. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feke FT, Prins W. Macromolecules. 1974;7:527. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leone M, Sciortino F, Migliore M, Fornili SL, Vittorelli MB. Biopolymers. 1987;16:743. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Emanuele A, Di Stefano L, Giacomazza D, Trapanese M, Palma-Vittorelli MB, Palma MU. Biopolymers. 1991;31:859. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bulone D, San Biagio PL. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1991;179:339. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amsterdam A, er-El Z, Shaltiel S. Arch. Biochem. Biohys. 1975;171:673. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(75)90079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waki S, Harvey JD, Bellamy AR. Biopolymers. 1982;21:1909. doi: 10.1002/bip.360210917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whytock S, Finch J. Biopolymers. 1991;31:1025. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Attwood TK, Nelmes BJ, Sellen DB. Biopolymers. 1988;27:201. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun M, Griess GA, Serwer P. J. Struct. Biol. 1994;113:56. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holmes DL, Stellwagen NC. Electrophoresis. 1990;11:5. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150110103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Slater GW, Noolandi J, Turmel C, Lalande M. Biopolymers. 1988;27:509. doi: 10.1002/bip.360270311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stellwagen NC. Electrophoresis. 1992;13:601. doi: 10.1002/elps.11501301121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Serwer P, Hayes SJ. Anal. Biochem. 1986;158:72. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90591-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chui MM, Phillips RJ, McCarthy MJ. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1995;174:336. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Slater GW, Treurniet JR. J. Chromatogr. A. 1997;772:39. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maaloum M, Pernodet N, Tinland B. Electrophoresis. 1998;19:1606. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150191015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stellwagen NC. Biopolymers. 1985;24:2243. doi: 10.1002/bip.360241207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stellwagen J, Stellwagen NC. Biopolymers. 1994;34:187. doi: 10.1002/bip.360340205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stellwagen J, Stellwagen NC. Biopolymers. 1994;34:1259. doi: 10.1002/bip.360340914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Holmes DL, Stellwagen NC. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 1989;7:311. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1989.10507774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stellwagen NC. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 1985;3:299. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1985.10508418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stellwagen NC. Biochemistry. 1988;27:6417. doi: 10.1021/bi00417a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Magnúsdóttir S, Åkerman B, Jonsson M. J. Phys. Chem. 1994;98:2624. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith SB, Aldridge PK, Callis JB. Science. 1989;243:203. doi: 10.1126/science.2911733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schwartz DC, Koval M. Nature. 1989;338:520. doi: 10.1038/338520a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gurrieri S, Bustamante C. Biochem. J. 1997:131. doi: 10.1042/bj3260131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gurrieri S, Smith SB, Bustamante C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rampino NJ. Biopolymers. 1991;31:1009. doi: 10.1002/bip.360310810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Piculell L, Nilsson S. J. Phys. Chem. 1989;93:5596. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Piculell L, Nilsson S. J. Phys. Chem. 1989;93:5602. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Smith SS, Gilroy TE, Ferrari TA. Anal. Biochem. 1983;128:138. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90354-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Strutz K, Stellwagen NC. Electrophoresis. 1998;19:635. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150190504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rampino NJ, Chrambach A. J. Chromatogr. 1992;596:141. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(92)80217-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fukudome K, Iwasaki K, Matsumoto S, Yamaoka K. Biopolymers. 1991;31:1455. doi: 10.1002/bip.360311212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nordén B, Elvingson C, Jonsson M, Åkerman B. Q. Rev. Biophys. 1991;24:103. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500003395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Holzwarth G, McKee CB, Steiger S, Crater G. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:10031. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.23.10031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Holzwarth G, Platt KJ, McKee CB, Whitcomb RW, Crater GD. Biopolymers. 1989;28:1043. doi: 10.1002/bip.360280603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jonsson M, Åkerman B, Nordén B. Biopolymers. 1988;27:381. doi: 10.1002/bip.360270304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Åkerman B, Jonsson M, Nordén B. Biopolymers. 1989;28:1541. doi: 10.1002/bip.360280906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gurrieri S, Smith SB, Wells KS, Johnson ID, Bustamante C. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4759. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.23.4759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lim NA, Slater GW, Noolandi J. J. Chem. Phys. 1990;92:709. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mayer P, Sturm J, Weill G. Biopolymers. 1993;33:1347. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mayer P, Sturm J, Weill G. Biopolymers. 1993;33:1359. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Platt KJ, Holzwarth G. Phys. Rev. A. 1989;40:7292. doi: 10.1103/physreva.40.7292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Deutsch JM. J. Chem. Phys. 1989;90:7436. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Deutsch JM, Madden TL. J. Chem. Phys. 1989;90:2476. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Popelka Š, Kabátek Z, Viovy J-L, Gaš B. J. Chromatogr. A. 1999;838:45. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zimm BH. J. Chem. Phys. 1991;94:2187. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Duke T, Viovy J-L, Semenov AN. Biopolymers. 1994;34:239. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Noolandi J, Rousseau J, Slater GW, Turmel C, Lalande M. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1987;58:2428. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.58.2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dorfman KD, Viovy J-L. Phys. Rev. E. 2004;69:011901. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.69.011901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Minc N, Viovy J-L, Dorfman KD. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005;94:198105. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.198105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Calladine CR, Collis CM, Drew HR, Mott MR. J. Mol. Biol. 1991;221:981. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)80187-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rill RL, Beheshti A, Van Winkle DH. Electrophoresis. 2002;23:2710. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200208)23:16<2710::AID-ELPS2710>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jamil T, Frisch HL, Lerman LS. Biopolymers. 1989;28:1413. doi: 10.1002/bip.360280807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lalande M, Noolandi J, Turmel C, Rousseau J, Slater GW. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:8011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.22.8011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Turmel C, Brassard E, Forsyth R, Hood K, Slater GW, Noolandi J. Electrophoresis of Large DNA Molecules: Theory and Applications. In: Lai E, Birren BW, editors. Current Communications in Molecular Biology. Vol. 1. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Plainview, NY: 1990. pp. 101–131. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schwartz DC, Cantor CR. Cell. 1984;37:67. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Carle GF, Frank M, Olson MV. Science. 1986;232:65. doi: 10.1126/science.3952500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Turmel C, Noolandi J. Electrophoresis. 1993;14:304. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150140153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Turmel C, Brassard E, Slater GW, Noolandi J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:569. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.3.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chu G, Vollrath D, Davis RW. Science. 1986;234:1582. doi: 10.1126/science.3538420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Clark SM, Lai E, Birren BW, Hood L. Science. 1988;241:1203. doi: 10.1126/science.3045968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Birren B, Lai E. Pulsed Field Gel Electrophoresis. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sturm J, Weill G. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1989;62:1484. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.62.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mayer P, Sturm J, Heitz C, Weill G. Electrophoresis. 1993;14:330. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150140156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Åkerman B, Jonsson M. J. Phys. Chem. 1990;94:3828. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Stellwagen J, Stellwagen NC. J. Phys. Chem. 1995;99:4247. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Stellwagen J, Stellwagen NC. Electrophoresis. 1992;13:595. doi: 10.1002/elps.11501301120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Stellwagen J, Stellwagen NC. Electrophoresis. 1993;14:355. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150140160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mickel S, Arena V, Jr., Bauer W. Nucleic Acids Res. 1977;5:1465. doi: 10.1093/nar/4.5.1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Johnson PH, Grossman LI. Biochemistry. 1977;16:4217. doi: 10.1021/bi00638a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Levene SD, Zimm GH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:4054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.12.4054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Serwer P, Hayes SJ. Electrophoresis. 1987;8:244. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Goldstein D, Drlica K. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1984;81:4046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.13.4046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Depew RE, Wang JC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1975;72:4275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.11.4275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Anderson P, Bauer W. Biochemistry. 1978;17:594. doi: 10.1021/bi00597a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wang JC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1979;76:200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lee C-H, Mizusawa H, Kadefuda T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1981;78:2838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.5.2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Åkerman B, Cole KD. Electrophoresis. 2002;23:2549. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200208)23:16<2549::AID-ELPS2549>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cole KD, Gaigalas A, Åkerman B. Electrophoresis. 2006;27:4396. doi: 10.1002/elps.200600347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Serwer P, Hayes SJ. Biochemistry. 1989;28:5827. doi: 10.1021/bi00440a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Whytock S, Finch J. Biopolymers. 1991;31:1025. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Bell L, Byers B. Anal. Biochem. 1983;130:527. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90628-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Brewer BJ, Fangman WL. Cell. 1987;51:463. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90642-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hayward GC, Smith MG. J. Mol. Biol. 1972;63:383. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(72)90435-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Tinland B, Pluen A, Sturm J, Weill G. Macromolecules. 1997;30:5763. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Murphy MC, Rasnik I, Cheng W, Lohman TM, Ha T. Biophys. J. 2004;86:2530. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74308-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Shin S, Day LA. Anal. Biochem. 1995;226:202. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hjertén S, Mosbach R. Anal. Biochem. 1962;3:109. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(62)90100-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Nossal R. Macromolecules. 1985;18:49. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Rüchel R, Brager MC. Anal. Biochem. 1975;68:415. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(75)90637-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Hecht A-M, Duplessix R, Geissler E. Macromolecules. 1985;18:2167. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Baselga J, Hernández-Fuentes I, Piérola IF, Llorente MA. Macromolecules. 1987;20:3060. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Baselga J, Llorente MA, Nieto JL, Hernández-Fuentes I, Piérola IF. Eur. Polym. J. 1988;24:161. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Baselga J, Llorente MA, Hernández-Fuentes I, Piérola IF. Eur. Polym. J. 1989;25:477. [Google Scholar]

- 133.Righetti PG, Caglio S. Electrophoresis. 1993;14:573. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150140191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Weiss N, Van Vleit T, Silberberg A. J. Polym. Sci.: Polym. Phys. Ed. 1979;17:2229. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Joosten JGH, McCarthy JL, Pusey PM. Macromolecules. 1991;24:6690. [Google Scholar]