Abstract

Objective To compare the cost effectiveness of nurses and doctors in performing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy.

Design As part of a pragmatic randomised trial, the economic analysis calculated incremental cost effectiveness ratios, and generated cost effectiveness acceptability curves to address uncertainty.

Setting 23 hospitals in the United Kingdom.

Participants 67 doctors and 30 nurses, with a total of 1888 patients, from July 2002 to June 2003.

Intervention Diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy carried out by doctors or nurses.

Main outcome measure Estimated health gains in QALYs measured with EQ-5D. Probability of cost effectiveness over a range of decision makers’ willingness to pay for an additional quality adjusted life year (QALY).

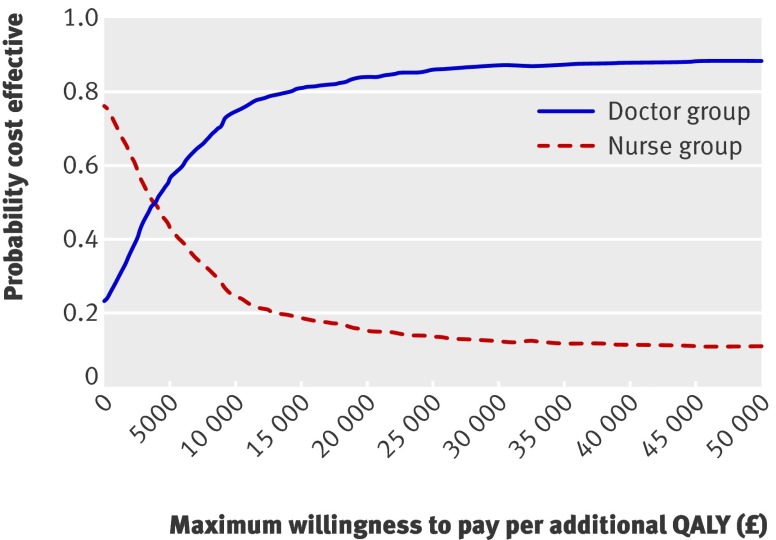

Results Although differences did not reach traditional levels of significance, patients in the doctor group gained 0.015 QALYs more than those in the nurse group, at an increased cost of about £56 (€59, $78) per patient. This yields an incremental cost effectiveness ratio of £3660 (€3876, $5097) per QALY. Though there is uncertainty around these results, doctors are probably more cost effective than nurses for plausible values of a QALY.

Conclusions Though upper gastrointestinal endoscopies and flexible sigmoidoscopies carried out by doctors cost slightly more than those by nurses and improved health outcomes only slightly, our analysis favours endoscopies by doctors. For plausible values of decision makers’ willingness to pay for an extra QALY, endoscopy delivered by nurses is unlikely to be cost effective compared with endoscopy delivered by doctors.

Trial registration International standard RCT 82765705

Introduction

Gastrointestinal endoscopy is a common clinical procedure, and its use is increasing over time. To meet the increasing demand, endoscopy is becoming widely practised by nurses in the United Kingdom.1 There has been little evaluation of the cost effectiveness of procedures undertaken by nurses rather than by doctors.

Consideration of the economics of diagnostic procedures can be complex as the cost effectiveness of the consequent treatment of any discovered condition needs to be considered. Economic evaluations of screening tests often estimate a “cost per condition detected,” which is determined partly by the sensitivity and specificity of the test. We focused not on the cost effectiveness of endoscopy itself but on whether or not there is a difference in endoscopy delivered by doctors or nurses. We took a pragmatic approach to the evaluation of this complex intervention,2 in which we assumed that it is the method of delivery (nurse or doctor) that is under consideration, not the intervention itself. We assessed relative cost effectiveness as part of a pragmatic randomised controlled trial undertaken in the UK.3

Methods

Study design and interventions

In the cost effectiveness analysis we addressed two issues: the decision about who should undertake the intervention and the level of uncertainty around this decision.4 5 The incremental cost effectiveness ratio represents the relation between costs and outcomes and thus facilitates decision making. We characterised the uncertainty associated with this decision by estimating the probability that nurse delivered endoscopy is cost effective over a range of values of decision makers’ willingness to pay for an additional quality adjusted life year (QALY).

The clinical study, of which this economic evaluation was part, was a pragmatic randomised trial in 23 hospitals in England, Scotland, and Wales.6 A total of 1888 patients were allocated at random to either a doctor or a nurse for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy. We collected health outcome measures at baseline, one day, one month, and one year after the intervention. Further details of the trial conduct, and patient sample and characteristics, are described elsewhere.3 We take a UK National Health Service (NHS) perspective with effects assessed in terms of health gains measured in QALYs. As the time horizon of the study was one year, discounting was not appropriate. We did not extrapolate beyond one year as the study was not powered to detect differences between groups in factors influencing long term health outcomes. We used Bayesian analysis in which the parameters have probability distributions. Thus it was possible, and appropriate, to compute the probability of an event being effective or cost effective.

Data collection and outcome measures

We extracted information on resources used during endoscopy of trial patients from resource time sheets. Information collected included duration of endoscopy, number of patients undergoing endoscopy, staffing, and consumables used (except for therapeutic procedures). The duration of procedures was timed from the extubation of one patient to the extubation of the next.

We obtained data on resource use after the endoscopy from examination of patients’ medical records and patients’ questionnaires administered at baseline and 12 months (table 1). We estimated the cost of the intervention from data on the duration of intervention from the clinical trial multiplied by figures for the cost per minute (for doctor or nurse) estimated from Netten and Curtis.7 Table 2 shows unit cost estimates in 2002-3 prices.

Table 1.

Details of resource use data and unit costs

| Item of resource use | Source of resource use | Source of unit cost data |

|---|---|---|

| NHS staff and time | Resource time sheet recorded during endoscopy lists | UK NHS salary scales |

| Inpatient stay | Hospital medical records examined at one year | UK NHS reference costs |

| Outpatient appointments | Patient questionnaires plus hospital medical records and primary care records at one year | UK NHS reference costs |

| GP visits | Patient questionnaires plus hospital medical records and primary care records at one year | Unit costs of health and social care4 |

| Medical management, such as drugs | Patient questionnaires and GP questionnaire | British National Formulary |

| Travel to and from appointments | Patient questionnaires at baseline, one month, and one year | AA |

| Private medical care | Patient questionnaires at baseline, one month, and one year | Unit costs of health and social care4 |

AA=Automobile Association.

Table 2.

Unit costs of resources used

| Unit cost (£) in 2002-3 prices4 | |

|---|---|

| General practitioner: | |

| Home visits (cost per visit) | 61 |

| Surgery visits | 20 |

| Practice nurse | |

| Home visit | 18 |

| Surgery visits | 10 |

| Day hospital attendances | 74 |

| Inpatient cost per day | 269-484 |

| Outpatient attendances | 75-110 |

| Intervention (cost per min) | 0.53 nurse, 1.82 doctor |

We used the EQ-5D instrument8 to measure patients’ health states and to ascribe values to those states. This instrument measures health across five dimensions (mobility, self care, usual activities, pain and discomfort, and anxiety and depression). Patients have three possible responses (no problems, moderate problems, or severe problems) for each of these dimensions to reflect their perceived their health states. This puts each into one of 245 mutually exclusive health states (the 243 states arising from the EQ-5D, plus unconscious, and dead), each valued on a scale from 0 (representing death) to 1 (representing perfect health).

We converted all EQ-5D scores to “utilities” through a tariff derived from a representative UK population sample.9 We compared mean QALYs generated in the two groups over the 12 month period. We plotted utility at baseline and subsequent points and calculated the area under the curve to estimate QALYs gained (or lost) by each patient. This reflects the fact that the QALY is the product of time and utility10 and assumes that changes in utility over time follow a linear path.11 We adjusted these estimates for baseline EQ-5D as recommended by Manca et al12 and included sex and age as covariates. In a subgroup analysis we separately considered the cost effectiveness of sigmoidoscopy and oesophagogastroduodenoscopy.

Analysis

Resource use and EQ-5D data were missing in several patients, with some missing both. For analysis we assumed that data were missing at random. We used two methods to impute missing data. For EQ-5D, we used the last value carried forward, as patients’ last score is likely to be the best predictor of the missing value. For resource use we used regression to impute missing values from age, sex, and EQ-5D scores.

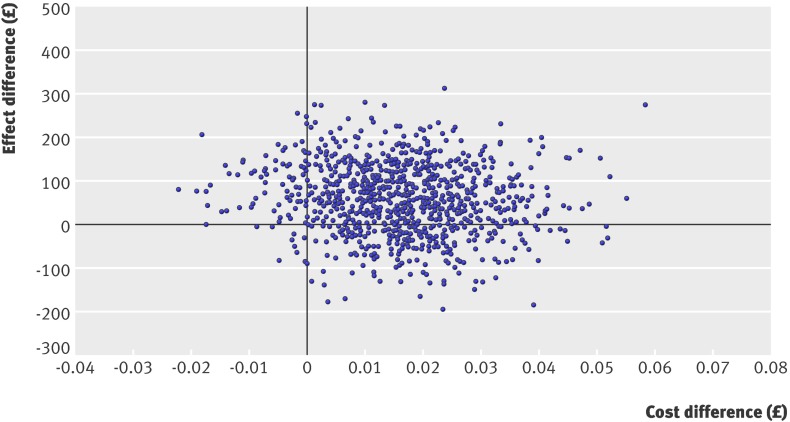

Traditionally, cost effectiveness analyses estimate incremental cost effectiveness ratios from mean differences in costs and effects between treatment and control groups, and 95% confidence intervals from the independent samples t test. As interpretation of incremental cost effectiveness ratios derived from more than one quadrant of the cost effectiveness plane is problematic,13 we calculated net monetary benefit14 for each group from trial and imputed data.15 To calculate patient specific net monetary benefits we multiplied each patient’s QALYs by the assumed maximum value of a QALY and subtracted that patient’s costs. We used these patient specific net monetary benefits to derive cost effectiveness acceptability curves and estimated the aggregate benefit from the equation:

where λ is the decision maker’s maximum willingness to pay for a QALY. For example, if treatment A has a mean cost of £100 000 and generates a mean of five QALYs with a QALY valued at £30 000, then the net monetary benefit associated with treatment A is £50 000 ((5×£30 000)−£100 000).

Thus the net monetary benefit depends on the value of the QALY, and analysis shows how sensitive the results are to changes in this value. The uncertainty around the net monetary benefit can estimate the probability that a strategy is cost effective through the cost effectiveness acceptability curve. This is a graphical representation of the probability of an intervention being cost effective over a monetary range for a decision maker’s willingness to pay for an additional unit of health gain. We used the values 0 (which assumes outcomes are equivalent or not valued), £1000, £10 000, £20 000, £30 000, and £50 000 as examples of the decision maker’s willingness to pay for one extra QALY.

Results

Missing data

At baseline utility data were missing for 184 patients (10%), either because they did not complete the questionnaire or because one of the items within the EQ-5D was missing. This figure increased to 489 patients (26%) at one month and 576 (31%) at one year. For data on resource use we examined the medical records of 1674 patients (89%); 606 patients (32%) did not report number of attendances in general practice. There were no significant differences in characteristics of patients with and without missing data.

Resource use

Table 3 presents mean levels of resource use. These estimates arise from responders to questionnaires without imputation. For most variables, the nurse based programme increased resource use (table 3). Endoscopy by nurses was followed by slightly more use of all primary care resources except home visits from general practitioners. In secondary care there were increased attendances at day hospital and outpatient clinics. These differences were small, however, and did not reach conventional levels of significance.

Table 3.

Mean resource use in two groups over 12 month study period

| Doctor group (n=953) | Nurse group (n=928) | Mean difference (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| General practitioner: | |||

| Home visits | 0.30 | 0.17 | 0.13 (−0.04 to 0.29) |

| Surgery visits | 4.81 | 5.05 | −0.24 (−0.72 to 0.24) |

| Practice nurse: | |||

| Surgery visits | 1.43 | 1.56 | −0.13 (−0.47 to 0.22) |

| Home visits | 0.03 | 0.11 | −0.08 (−0.22 to 0.05) |

| Day hospital attendances | 0.27 | 0.35 | −0.08 (−0.14 to 0.01) |

| Inpatient length of stay | 1.10 | 1.10 | 0.00 (−0.53 to 0.53) |

| Outpatient attendances | 1.34 | 1.46 | −0.13 (−0.32 to 0.06) |

| Intervention time (minutes) | 23.50 | 22.41 | 1.09 (−1.95 to 4.13) |

Health states

There was little effect in either group on usual activities or self care. Both groups showed an increased proportion of patients in the least severe pain and discomfort and anxiety and depression groups, and these differences favoured endoscopy delivered by doctors (table 4). Mobility deteriorated in both groups, with the nurse group again performing slightly less well than the doctor group. These results were consistent with the clinical effectiveness results as measured by the condition specific gastrointestinal symptom rating questionnaire.3 Three of the four factors measured at one year favoured the doctor group, though none of these differences reached significance.3

Table 4.

Number (percentage) of patients in each EQ-5D dimension (health state 1 (best), 2, or 3 (worst)) by group at baseline, one month, and one year follow-up

| Baseline | One month | One year | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Doctor group (n=836): | |||||||||||

| Mobility | 579 (69) | 257 (31) | 0 | 580 (69) | 254 (30) | 2 (0.2) | 567 (68) | 268 (32) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| Self care | 761 (91) | 75 (9) | 0 | 744 (89) | 92 (11) | 0 | 739 (88) | 93 (11) | 4 (1) | ||

| Usual activities | 476 (60) | 328 (39) | 33 (4) | 471 (56) | 327 (39) | 39 (5) | 472 (57) | 326 (39) | 37 (4) | ||

| Pain/discomfort | 176 (21) | 570 (68) | 89 (11) | 250 (30) | 517 (62) | 69 (8) | 263 (32) | 498 (60) | 74 (9) | ||

| Anxiety/depression | 423 (51) | 369 (44) | 44 (5) | 468 (56) | 323 (39) | 45 (5) | 452 (54) | 344 (41) | 39 (5) | ||

| Nurse group (n=868): | |||||||||||

| Mobility | 596 (69) | 268 (31) | 4 (0.5) | 588 (68) | 278 (32) | 3 (0.3) | 565 (65) | 301 (35) | 2 (0.2) | ||

| Self care | 786 (91) | 80 (9) | 2 (0.2) | 766 (88) | 99 (11) | 3 (0.3) | 768 (89) | 97 (11) | 3 (0.3) | ||

| Usual activities | 470 (54) | 367 (42) | 30 (4) | 465 (54) | 368 (42) | 35 (4) | 474 (55) | 361 (42) | 33 (4) | ||

| Pain/discomfort | 179 (21) | 591 (68) | 98 (11) | 234 (27) | 559 (64) | 75 (9) | 247 (28) | 536 (62) | 85 (10) | ||

| Anxiety/depression | 455 (52) | 356 (41) | 57 (7) | 483 (56) | 334 (39) | 51 (6) | 479 (55) | 331 (38) | 58 (7) | ||

QALYs

From these estimates, which included values imputed for missing values, we estimated changes in EQ-5D over one year (table 5). In turn we used these estimates to generate QALYs.

Table 5.

Mean EQ-5D scores, QALYs, and costs (£) per patient over 12 months by group

| Doctor group (n=931) | Nurse group (n=957) | Difference (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean EQ-5D scores: | |||

| Baseline | 0.700 | 0.689 | 0.011 (−0.014 to 0.040) |

| One month | 0.713 | 0.697 | 0.016 (−0.009 to 0.041) |

| One year | 0.710 | 0.693 | 0.017 (−0.008 to 0.043) |

| QALYs | 0.712 | 0.695 | 0.0153* (−0.008 to 0.039) |

| Primary care costs | 135 | 128 | 7 (−3 to 15) |

| Secondary care costs | 565 | 538 | 27 (−127 to 181) |

| Intervention costs | 39 | 16 | 23 (20 to 26) |

| Total cost | 739 | 683 | 56 (−100 to 213) |

*Difference in QALYs allows for baseline differences in EQ-5D, sex, and age.

Though differences were small, the gain in QALYs was greater after endoscopy by doctors than by nurses. This is partly explained by difference in baseline characteristics, notably the EQ-5D score at baseline. Adjustment for these reduced the difference in QALYs to 0.0153 (95% confidence interval −0.008 to 0.039) (table 5). We used this estimate in the construction of cost effectiveness acceptability curves, which reflect the finding that EQ-5D score at baseline was higher for the doctor group.

While this difference in QALYs seems to be small in absolute terms, it equates to a difference of five to six days of additional perfect health each year. There are several plausible explanations for the improved QALY scores for doctors. The most likely scenario is that nurses requested more subsequent tests and investigations. Such tests and investigations might have a negative effect on patients’ wellbeing and it is possible that this manifested itself in lower QALY scores in the nurse group.

Total cost

Table 5 shows estimated differences in cost per patient between groups, including the cost of the intervention. As there was uncertainty around these estimates, the difference was not significant at conventional levels. The intervention cost more in the doctor group because doctors’ time costs more than nurses’ time. There was little difference in the duration of endoscopy between groups. In addition patients allocated to doctors had slightly higher costs in both primary and secondary care. The differences in costs associated with resource use in primary and secondary care was small. Though in absolute terms there were (slightly) more contacts in both primary and secondary care in the nurse group than in the doctor group, the doctor group was associated with more costly resources, particularly salary costs. Adjustment for total costs for baseline differences in age and sex made no meaningful difference to the results.

Incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER)

The doctor group generated 0.0153 more QALYs than the nurse group, at a net cost of £56 per patient. This resulted in an incremental cost effectiveness ratio of £3660 per QALY. There was much uncertainty around these results, and neither the difference in patients’ outcomes nor that in costs approached traditional levels of significance. Therefore we used the net monetary benefit approach and generated cost effectiveness acceptability curves.

Net monetary benefits and cost effectiveness acceptability curves

Figure 1 shows the cost effectiveness acceptability curve for values of a QALY between zero and £50 000. Attaching no value to a QALY yields a probability of about 78% of the nurse group being cost effective, implying a chance of 78% that nurses reduced costs. The probability of nurses being cost effective, however, decreases as the value of a QALY increases and as doctors become more cost effective. At a value of £30 000 per QALY, often stated to be the borderline for the NHS, nurses have only a 13% chance of being cost effective. Indeed, for all plausible values of a QALY, doctors are more likely to be cost effective than nurses. There is, however, much uncertainty around this result; the cost effectiveness scatter in figure 2 shows the plots of incremental costs and incremental effects for doctors compared with nurses.

Fig 1 Cost effectiveness acceptability curve

Fig 2 Cost effectiveness scatter

Sensitivity analysis

Though this stochastic analysis addresses intrinsic uncertainty, sensitivity analysis is still appropriate to check on methodological uncertainty, specifically uncertainty arising from data imputation and from different forms of endoscopy.

We had complete medical records and EQ-5D data for 440 patients, 227 (51.6%) in the nurse group and 213 (48.4%) in the doctor group, reflecting the distribution of patients between groups in the full trial. Most missing data omitted a single cost or a single EQ-5D dimension at baseline or follow-up. The resulting estimates were similar to those with imputed data: doctors cost £40 more than nurses (−£148 to £231) but generated 0.021 more QALYs (−0.02 to 0.06). This yields an incremental cost effectiveness ratio of £2060, lower than with imputed data. The smaller sample, however, leads to more uncertainty: the probability of doctors being cost effective never exceeds 84%, whatever the value of a QALY.

Sigmoidoscopy v oesophagogastroduodenoscopy

Sigmoidoscopy showed an incremental cost effectiveness ratio of £2600 per QALY for doctors. Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy cost relatively more for doctors, resulting in a higher ratio of £7850. Both ratios, however, would be acceptable for most reasonable values of a decision maker’s willingness to pay for a QALY.

Discussion

Principal findings

Patients undergoing endoscopy carried out by doctors gained 0.015 QALYs more than those treated by nurses, at an increased cost of around £56 per patient, yielding an incremental cost effectiveness ratio of £3660 per QALY. Doctor delivered endoscopy would therefore seem to be acceptably cost effective. The analysis also suggests that, for most reasonable values of a decision maker’s willingness to pay for an additional QALY, endoscopy delivered by nurses is unlikely to be cost effective compared with endoscopy delivered by doctors based on the evidence of this single trial analysis. There is considerable uncertainty around these estimates, which indicates that further research might be needed.

Strengths and weaknesses

We used a randomised trial to compare the cost effectiveness of doctors and nurses performing endoscopy. There were missing data both on resource use and patients’ utility. While imputing these data is not ideal, the results of that imputation are robust, as analysis limited to complete cases yields similar results. The study lasted only one year, though there is potential for later effects in this population—for example, missed diagnoses. A longer trial would be ideal, but the similarity of immediate and delayed complications between nurses and doctors suggests there is little difference in their long term performance.

It is possible that the use of the EQ-5D and the resulting estimates of QALYs are not sensitive enough in these patients to identify differences in their health related quality of life. The results of our economic analysis, however, are similar to those of the clinical analysis in that there was a non-significant effect in favour of doctors.

Hence the QALY gain was greater one year after endoscopy by doctors than by nurses. This is despite patients being more satisfied with endoscopies performed by nurses. This does not imply inconsistency, as short term gains in satisfaction probably reflect differences in process, while medium term gains in quality of life reflect patients’ perception of outcomes, perhaps in the form of the accuracy of the procedure and their confidence in the results.

Nurse endoscopists might not have reached “steady state” in experience and confidence. As their experience grows, they might become more confident and therefore order fewer follow-up tests. The higher frequency of tests and interventions in the nurse group, however, might reflect intrinsic differences between the professions in terms of attitudes to risk.

Meaning of the study

Though there is debate over the appropriate NHS threshold cost per QALY, Rawlins and Culyer16 argue that the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence would be unlikely to reject a technology with a cost of between £5000 and £15 000 per QALY on grounds of cost effectiveness. On the evidence of this trial, therefore, doctor delivered endoscopy seems cost effective.

This result might surprise some as upper gastrointestinal endoscopies and sigmoidoscopies by nurses cost slightly less than doctors and the difference in health outcomes is small and does not reach traditional levels of significance. Our economic analysis estimates the probability of cost effectiveness from the uncertainty around the estimates of costs and effects, rather than discarding differences that do not reach “significance.” Hence this methodological paradigm leads to a different interpretation of our results from that adopted in the clinical effectiveness paper.6

Interpretation depends on the paradigm chosen and the factors under consideration by decision makers. Classic statistical inference fails to reject the null hypotheses that there is no difference in effectiveness or cost effectiveness between endoscopy delivered by doctors and nurses. Policy makers might therefore view nurse endoscopists as an acceptably safe and effective way of changing skill mix in health care, releasing medical resources and increasing the role of nurse specialists. In contrast with the classic statistical approach, economic inference in this context makes decisions by comparing the estimated cost per QALY with a threshold equal to the most that a decision maker would pay for a QALY. In this trial this leads to the conclusion that upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and sigmoidoscopy delivered by doctors would be cost effective at a typical threshold. Bayesian analysis goes further by estimating the probability that the intervention is cost effective in the sense that the estimated cost per QALY exceeds a given threshold. In this trial this form of analysis leads to the conclusion that the average doctor endoscopist has a probability of 80-90% of being more cost effective than the average nurse endoscopist at commonly used values of willingness to pay for a QALY. Policy makers or hospital decision makers pursuing efficiency alone would therefore choose endoscopy delivered by doctors.

Unanswered questions

The choice of skill mix in endoscopy might be influenced by factors other than cost effectiveness, such as affordability, staff shortages, and access to health care, all of which enter into policy decisions. At the start of this trial there was concern about shortages of medical staff but, after the expansion of medical schools, concerns shifted to surpluses and potential unemployment of junior doctors.17 Endoscopy delivered by nurses, in the current state of their training and experience, is unlikely to be cost effective compared with endoscopy delivered by doctors. As nurses grow in experience over time it will be important to continue to monitor both effectiveness and cost effectiveness.

What is already known on this topic

To meet increasing demand for gastrointestinal endoscopy, nurses are increasingly undertaking both upper and lower endoscopy in the UK

Clinical studies, mainly observational and non-randomised, have established the safety and acceptability of this, but there has been little evaluation of the cost effectiveness

What this paper adds

Though there is uncertainty around the results, doctors are likely to be more cost effective than nurses for plausible values of a QALY

Contributors: GR was responsible for the design, conduct, and interpretation of the analysis, drafted the paper, and is guarantor. KB contributed to analysis, interpretation, and drafting the paper. JW led the trial team and was principal author of the final report. IR contributed to the design and implementation of the trial and drafting of the paper. DD developed, validated, and applied the method of assessing the upper GI endoscopy video recordings, validated the gastrointestinal symptom rating questionnaire, collected and analysed clinical data, notably from hospital records. WYC validated the gastrointestinal symptom rating and gastrointestinal endoscopy satisfaction questionnaires. AF contributed to the overall design and implementation of the trial and drafting of the paper. SC developed, validated, and managed the main database. All authors reviewed successive drafts of both papers.

Funding: The study was funded by the NIHR Evaluation Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre. All researchers are independent from this source of funding.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Welsh multicentre research ethics committee and informed consent was given by all patients.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;338:b270

References

- 1.Pathmakanthan S, Murray I, Smith K, Heeley R, Donnelly M. Nurse endoscopists in United Kingdom health care: a survey of prevalence, skills and attitudes. J Adv Nurs 2001;36:705-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medical Research Council. A framework for development and evaluation of RCTs for complex interventions to improve health. London: MRC, 2000.

- 3.Williams J, Russell I, Durai D, Cheung W-Y, Farrin A, Bloor K, et al. What are the clinical outcome and cost-effectiveness of endoscopy undertaken by nurses when compared with doctors? Health Technol Assess 2006;10;1-95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Sculpher M, Claxton K, Akehurst R. It’s just evaluation for decision making—recent developments in, and challenges for, cost-effectiveness research. In: Smith PC, Ginnelly L, Sculpher M, eds. Health policy and economics: opportunities and challenges. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- 5.Claxton K, Sculpher M, McCabe C, Briggs A, Akehurst R, Buxton M, et al. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis for NICE technology assessment: not an optional extra. Health Econ 2005;14:339-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams J, Russell I, Durai D, Cheung WY, Farrin A, Bloor K, et al. Effectiveness of nurse delivered endoscopy: findings from randomised multi-institution nurse endoscopy trial (MINuET). BMJ 2009;338:b231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Netten A, Curtis P. Unit costs of health and social care. Personal social services research unit report. Canterbury: University of Kent, 2003.

- 8.Kind P. The EuroQoL instrument: an index of health-related quality of life. In: Spilker B, ed. Quality of life and pharmacoeconomics in clinical trials. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1996.

- 9.Dolan P, Gudex C, Kind P, Williams A. A social tariff for EuroQol: results from a UK general population survey. York: University of York, 1995. (Centre for Health Economics Discussion Paper 138.)

- 10.Matthews J, Altman D, Campbell M, Royston P. Analysis of serial measurements in medical research. BMJ 1990;300:230-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richardson G, Manca A. Calculation of quality adjusted life years (QALYs) in the published literature: a review of methodology and transparency. Health Econ 2004;13:1203-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manca A, Hawkins N, Sculpher, MJ. Estimating mean QALYs in trial based cost-effectiveness analysis: the importance of controlling for baseline utility. Health Econ 2005;14:487-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Hout BA, Al MJ, Gordon GS, Rutten FF. Costs, effects and C/E-ratios alongside a clinical trial. Health Econ 1994;3:309-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stinnett AA, Mullahy J. Net health benefits: a new framework for the analysis of uncertainty in cost-effectiveness analysis. Med Decis Making 1998;18:S68-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fenwick E CK, Sculpher M, Briggs A. Improving efficiency and relevance of health technology assessment: the role of iterative decision analytic modelling. York: Centre for Health Economics, University of York, 2001.

- 16.Rawlins MD, Culyer AJ. National Institute for Clinical Excellence and its value judgments. BMJ 2004;329:224-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.British Medical Association. 21,000 into 9,500 won’t go—BMA raises concerns about junior doctor unemployment. London: BMA, 14 Jun 2006. (press release).