Abstract

Nucleotide sequence analysis of the region surrounding the pIVET8 insertion site in Yersinia ruckeri 150RiviXII, previously selected by in vivo expression technology (IVET), revealed the presence of eight genes (traHIJKCLMN [hereafter referred to collectively as the tra operon or tra cluster]), which are similar both in sequence and organization to the tra operon cluster found in the virulence-related plasmid pADAP from Serratia entomophila. Interestingly, the tra cluster of Y. ruckeri is chromosomally encoded, and no similar tra cluster has been identified yet in the genomic analysis of human pathogenic yersiniae. A traI insertional mutant was obtained by homologous recombination. Coinfection experiments with the mutant and the parental strain, as well as 50% lethal dose determinations, indicate that this operon is involved in the virulence of this bacterium. All of these results suggest the implication of the tra cluster in a virulence-related type IV secretion/transfer system. Reverse transcriptase PCR studies showed that this cluster is transcribed as an operon from a putative promoter located upstream of traH and that the mutation of traI had a polar effect. A traI::lacZY transcriptional fusion displayed higher expression levels at 18°C, the temperature of occurrence of the disease, and under nutrient-limiting conditions. PCR detection analysis indicated that the tra cluster is present in 15 Y. ruckeri strains from different origins and with different plasmid profiles. The results obtained in the present study support the conclusion, already suggested by different authors, that Y. ruckeri is a very homogeneous species that is quite different from the other members of the genus Yersinia.

Yersinia ruckeri causes yersiniosis, a systemic infection affecting mainly salmonids in fish farms with important economic consequences. The major source of infection is the shedding of bacteria from the intestines of carrier fish, and transmission is also favored by the ability of most strains to survive and remain infective in the aquatic environment (46), sometimes forming biofilms (11). Although fish are generally treated with inactivated whole-cell vaccines, outbreaks still occur under severe stress or poor hygiene conditions. Moreover, commercial vaccines do not confer protection against a new biogroup recently isolated in southern England (2), Spain (21), and the United States (1). Early approaches to the study of this bacterium indicated that some extracellular products, including hemolysins, lipases, and proteases, could play an important role in virulence (36). Nevertheless, only recently have some of the pathogenic mechanisms involved in the development of the infection been identified (47). The use of in vivo expression technology (IVET) permitted the selection of a set of in vivo-induced (ivi) genetic loci, some of which have been proven to participate in virulence, such as the iron uptake mechanism via the catecholate siderophore ruckerbactin (14) and YhlA hemolysin/cytolysin (16). Fernández et al. (17) also demonstrated the involvement in virulence of Yrp1, a serralysin-type protease. However, the pathogenic mechanisms of this bacterium are still not very well understood.

Type IV secretion systems (T4SS) from gram-negative bacteria are mainly involved in the spread of plasmids. T4SS constitute complex conjugation machineries composed of a pilus and a mating channel through which the DNA transfer intermediate is translocated. The T4SS genes involved in this kind of process are generally carried by conjugative plasmids, such as RP4 and pKM101 (7), which harbor antibiotic resistance genes that are disseminated among bacteria. Over the last several years, the adaptation in some bacteria of T4SS for delivering virulence factors into eukaryotic cells has been described (9, 42, 50). These T4SS are divided into two subgroups according to their similarities to the Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB system (type IVA) or to the Legionella pneumophila icm/dot system (type IVB). Functionally, the VirB system of A. tumefaciens is an example of a type IV exporter of DNA across bacterial membranes to be introduced into plant cells to induce tumor proliferation (52). Extracellular pathogens such as Helicobacter pylori (6) and Bordetella pertussis (12, 48) use T4SS to deliver the CagA protein or the pertussis toxin, respectively, into the extracellular milieu or the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells. Finally, in the case of some intracellular pathogens, such as L. pneumophila (41), Brucella sp. (33), and Bartonella sp. (40), T4SS participate in the transfer of different effector molecules into the target cells in order to ensure their survival within macrophages or red blood cells.

It is well established that some components of T4SS involved in conjugation share structural similarity, display considerable sequence homology, and consequently have identical protein functions, with the T4SS related to pathogenicity (8, 19). For instance, traH, traI, traJ, and traK genes from the traHIJKCLMN (hereafter referred to as the tra operon or tra cluster) transfer loci, which are present among others in the tra region of plasmid R64 (28, 29), code for proteins similar to those encoded by the dot/icm genes of the virulence-related type IVB secretion system of L. pneumophila (29). The presence of conjugative plasmids has been described in several Yersinia species (24, 25, 45, 49). Recently, a type IVB secretion system has been identified in the genomic analysis of Y. pseudotuberculosis IP31758, the causative agent of Far East scarlet-like fever (13). This system is encoded by plasmid pYpsIP31758.1, and it is phylogenetically related to the type IVB dot/icm secretion system of L. pneumophila (13). Until now, no other type IVB secretion system had been reported in the genus Yersinia.

Here, we report the in-depth analysis of the previously isolated Y. ruckeri iviXII clone (14) that allowed the identification of a tra chromosomally located operon, which is structurally related to the DNA transfer system present in plasmid pADAP of S. entomophila (26). A traI::lacZY transcriptional fusion showed that the operon was regulated by nutritional conditions and temperature. The fact that the identification of the cluster was accomplished via IVET, together with in vivo competition studies and 50% lethal dose (LD50) experiments, indicated that the tra operon contributes to the virulence of Y. ruckeri. In addition, PCR analysis showed the presence of this operon in Y. ruckeri strains from different origins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in the present study are listed in Table 1. Bacterial strains were routinely cultured in nutrient broth (NB) and nutrient agar (NA) from Difco at 18 or 28°C for Y. ruckeri and in 2×TY (1.6% tryptone, 1% yeast extract, and 0.5% NaCl) broth (Difco) and agar at 37°C for Escherichia coli. When required, the following compounds were added to the media: 100 μg of ampicillin/ml, 50 μg of rifampin/ml, and 50 μg of streptomycin/ml (all from Sigma-Aldrich Co.). Growth was monitored by determining the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) at different times during incubation, and bacterial concentrations were determined by serial dilutions and plate counts. Long-term storage of the strains was done in 25% glycerol at −20°C and −70°C, and strains were lyophilized at −70°C. Experiments on the regulation of gene expression were performed with minimal medium M9, prepared as described by Romalde et al. (37).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmida | Characteristics and/or originb | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Yersinia ruckeri | ||

| 150R | Rifr derivative of 150 | 17 |

| 150RiviXII | Strain containing ivi fusion expressed only in the host | 14 |

| 150RtraI | RifrtraI::pIVET8 | This study |

| 146, 147, 148, 149, and 150 | Strains isolated from an outbreak in trout (Danish fish farm) | J. L. Larsen (Denmark) |

| 955, 956, and 43/19 | Strains isolated from an outbreak in trout (U.S. fish farms) | CECT (Spanish Type Culture Collection) |

| 35/85 and 13/86 | Strains isolated from outbreaks in trout (Danish and United Kingdom fish farms, respectively) | C. J. Rodgers, University of Tarragona, Spain |

| A100 and A102 | Strains isolated from an outbreak in trout (Spanish fish farm) | I. Márquez, Laboratory of Animal Health |

| 150/05, 158/05, and 382/05 | Strains isolated from outbreak in trout (Spanish fish farm) | ProAqua Nutricón S.A. |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| S17-1λpir | Smr λ(pir) hsdR pro thi RP4-2 Tc::Mu Km::Tn7 | 43 |

| MT1694 | Helper strain HB101 containing pRK2013 | 18 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pIVET8 | AproriR6K mob+ promoterless cat-lacZY | 30 |

| pTRAI | pIVET8::BglII (traI), Apr | This study |

All Y. ruckeri strains with the exception of strain 956 (which belongs to serotype 2) belong to serotype 1.

Rifr, rifampin resistance; Apr, ampicillin resistance; Smr, streptomycin resistance.

Genetic techniques.

Routine DNA manipulation was performed as described by Sambrook et al. (39). Phage T4 DNA ligase and calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase were purchased from Roche, Ltd.; restriction enzymes were from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Ltd.; and oligonucleotides were from Sigma-Aldrich Co.

DNA sequencing was performed at the Universidad de Oviedo facility by the dideoxy chain termination method with a DR terminator kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions in an ABI Prism 310A automated DNA sequencer from Perkin-Elmer. The sequences were compared using the computer programs BLASTx and BLASTp to those in the databases.

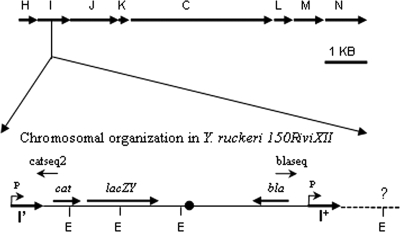

Plasmid DNA was recovered from the Y. ruckeri 150RiviXII chromosome by triparental mating (34). Briefly, cultures of the Y. ruckeri fusion-containing strain 150RiviXII, an E. coli strain plus the recipient (S17-1λpir), and an E. coli strain harboring a helper plasmid (pRK2013) that encodes Tra were mixed in equal amounts (100 μl of overnight cultures), pelleted, plated onto a 2×TY plate, and incubated at 28°C for 6 h. Transconjugants containing the transcriptional fusion induced in vivo were selected in plates with both ampicillin and streptomycin at the concentrations mentioned above. The DNA fragment situated upstream of the cat gene from plasmid pIVET8 was sequenced by using the initial primer catseq-2 (5′-CGGTGGTATATCCAGTG-3′), corresponding to nucleotides 31 to 15 of the cat gene (Fig. 1). Thus were obtained the partial sequence of traI and the complete sequence of traH. To analyze the fragment adjacent to the partial traI sequence in clone iviXII, genomic DNA from Y. ruckeri 150RiviXII was digested with EcoRI (Fig. 1). The restriction fragments were religated and the mixture was used to transform cells of E. coli S17-1λpir. Transformants were selected on 2×TY agar medium containing ampicillin. The resulting plasmid, containing the rest of the cluster except for the end of gene traN, was sequenced with the initial primer blaseq from the pIVET8 bla gene. The rest of gene traN was obtained by inverse PCR. Briefly, genomic DNA from Y. ruckeri 150R was digested with ClaI, and the generated fragments were religated. The ligation mixture was used as template DNA for a PCR, using a long amplification kit (Biotools) and oligonucleotides corresponding to the known DNA sequence. The reaction was performed in a Perkin-Elmer 9700 GeneAmp thermocycler. Sequences were compared to the GenBank NR database using BLASTx and BLASTp.

FIG. 1.

Chromosomal arrangement of the region containing the traHIJKCLMN genes in Y. ruckeri 150R. Arrows indicate the direction of the transcription. The organization of the transcriptional fusion between traI and the promoterless genes cat and lacZY in Y. ruckeri 150RiviXII is shown underneath, and the putative promoter (P) selected by IVET is indicated. blaseq and catseq2 oligonucleotides were used to sequence the adjacent fragments to the pIVET8 integration site. E, EcoRI sites; cat, chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene (promoterless); lacZY, genes for lactose fermentation (promoterless); bla, ampicillin resistance gene.

Localization of the tra genes in the Y. ruckeri genome.

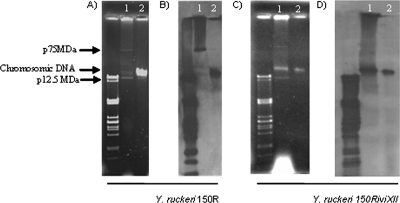

Total DNA was isolated from 1-ml portions of overnight cultures of Y. ruckeri 150R and Y. ruckeri 150RiviXII strains by using a Gene Elute genomic bacterial DNA kit (Sigma). Plasmid DNA was obtained by using the protocol described by Kado and Liu (27). Chromosomal and plasmid DNA were separated by electrophoresis in 0.75% agarose gels, transferred to a nylon membrane, and hybridized with probes corresponding to internal fragments of traI and bla. Probe labeling, hybridization, and development were performed with a DIG DNA labeling and detection kit (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

In vitro regulation analysis.

For promoter expression studies, 20 ml of culture medium supplemented with ampicillin was inoculated with 200 μl of Y. ruckeri 150RiviXII overnight cultures, followed by incubation in orbital shakers at 250 rpm. To determine the influence of temperature, cells were incubated in minimal medium M9 at 18 or 28°C. To determine the effect of the presence of different salts, cells were incubated in M9 supplemented with NaCl (250 mM), MgCl2 (25 mM), or CaCl2 (1.25 mM). Samples from stationary-phase cultures were collected and stored at −20°C. The β-galactosidase activity of the traI::pIVET8 transcriptional fusion was measured as described by Miller (32), using ONPG (o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) as a substrate.

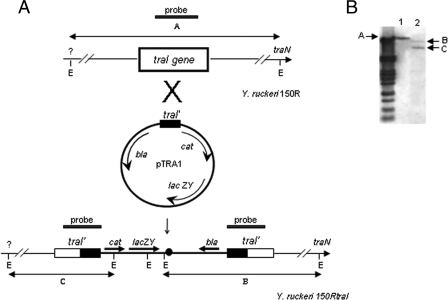

Construction of traI insertion mutant.

A 317-bp internal fragment of traI was amplified by PCR with the primers traI-1 (5′-ATGCAGATCTGTTTTTGGGGCGGACGC-3′, nucleotides 480 to 464 are in boldface type) and traI-2 (5′-ATGCAGATCTCCGTGGGGTTTCAGGGA-3′, nucleotides 164 to 180 are in boldface type). Both primers contained restriction sites for BglII (indicated in italics) and four additional bases at their 5′ ends. The generated amplicon was digested with BglII and ligated into pIVET8, previously digested with the same enzyme and dephosphorylated. The ligation mixture was used to transform electrocompetent cells of E. coli S17-1λpir. Selected transformants, containing the plasmid with insert, were used to conjugate with Y. ruckeri 150R to obtain the traI mutant. The mutation was confirmed by Southern blot analysis. Genomic DNA isolated from Y. ruckeri 150R and the mutant strain 150RtraI was digested with EcoRI and separated in a 0.75% (wt/vol) agarose gel. DNA was transferred to a nylon membrane (Amersham), fixed by UV irradiation, and hybridized with the 317-bp PCR-generated internal fragment from the traI. Probe labeling, hybridization, and development were performed with the DIG DNA labeling and detection kit from Roche according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Salt tolerance of the traI mutant.

The parental (Y. ruckeri 150R) and mutant (Y. ruckeri 150RtraI) strains were grown up to an OD600 of 0.5 (∼108 cells/ml). Five 10-fold serial dilutions were prepared, and 100-μl portions of 10−4 and 10−5 dilutions were plated onto NA and NA supplemented with 250 mM NaCl. The numbers of bacteria on both types of media were determined after 48 h. Three independent experiments were carried out, and in each one plating was carried out in triplicate.

LD50 studies with the traI mutant strain.

To determine the role in virulence of the traI mutation, LD50 experiments with the parental and mutant strains were carried out as described by Fernández et al. (17). Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) weighing between 8 and 10 g were kept in 60 l tanks at 18 ± 1°C in dechlorinated water. Groups of 10 fish were challenged by intraperitoneal injection of 0.1-ml serial 10-fold dilutions of exponential-phase cultures of the strains Y. ruckeri 150R and Y. ruckeri 150RtraI corresponding to a range of 102 to 108 cells, and mortalities were monitored for up for 7 days. The microorganisms were previously washed and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline. Control fish were injected with 0.1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline. In parallel, 100-μl aliquots of dilutions 10−4 and 10−5 of the cultures corresponding to both strains were plated in duplicate on NA to estimate the numbers of cells injected into the fish. Two independent experiments were carried out, and LD50 determinations were calculated by the method of Reed and Muench (35). All of the animal experiments were conducted under the European legislation governing animal welfare and were authorized and supervised by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee from the Oviedo University.

In vivo and in vitro competition assays.

For in vivo competition assays, the mutant and parental strains were grown separately in NB at 18°C in orbital shakers at 250 rpm up to an OD600 of 0.5 (∼108 cells/ml). Portions (2.5 ml) of each strain were mixed, and 10-fold dilutions of this suspension were plated onto NA and NA with ampicillin to count the number of total CFU and mutant CFU, respectively. Based on these values, the exact input ratio of mutant to parental strains was calculated. A sample of 0.1 ml at dilution 10−2 (∼106 cells of each strain/ml) was used to infect rainbow trout weighing from 8 to 10 g by intraperitoneal injection. After 72 h, the fish were euthanized and, afterward, the spleens, livers, and intestines were recovered and homogenized in NB with a stomacher. Tenfold serial dilutions of the suspensions were plated onto selective media to determine the output ratio of mutant to parental cells. The media used were NA and NA supplemented with ampicillin to count the number of total CFU and mutant CFU, respectively. From this, the output ratio of mutant to parental was calculated. The competitive index (CI) is defined as the output ratio (mutant to parental) divided by the input ratio (mutant to parental).

For in vitro competition assays, 20 ml of NB was inoculated with 0.2 ml of the dilution 10° (108 cells of each strain/ml). The cultures were grown at 18°C up to an OD600 of 1.2. The input and output ratios of mutant strain to wild-type strain were determined by selective plating as described for the in vivo competition assay.

RT-PCR.

Total RNA was obtained from 3-ml late-exponential-phase cultures of parental strain 150R and mutant 150RtraI grown in M9 at 18°C. RNA was isolated by using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) and was treated with RNase-free DNase (Ambion) to eliminate traces of DNA. Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analyses were performed by using Superscript One-Step with Platinum Taq (Invitrogen Life Technologies); 40 ng of RNA was used in each reaction. Control PCRs using Platinum Taq polymerase (Invitrogen Life Technologies) were performed to determine whether RNA was free of contaminant DNA. The primers used are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Primers used for RT-PCRs

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence (5′-3′) | Position (nt)a | Gene |

|---|---|---|---|

| XII-oF | CCCAGCTAGCCCGTCAA | 247-264 | traH |

| XII-pR | TGTGCCATATCGGTCGC | 323-307 | traI |

| XII-pF | GCGACCGATATGGCACA | 307-323 | traI |

| XII-qR | CGCAGACGTTCGCCTCG | 320-304 | traJ |

| XII-qF | CGAGGCGAACGTCTGCG | 304-320 | traJ |

| XII-rR | CACGACCGGAATACCCA | 69-53 | traK |

| XII-rF | TGGGTATTCCGGTCGTG | 53-69 | traK |

| XII-sR | CCAGCAGGTCGGCCATC | 419-403 | traC |

| XII-tF | GCACTGGCGGGAATGGC | 3047-3063 | traC |

| XII-xR | CCAATGACGCCGAAACG | 178-162 | traL |

| XII-xF | CGTTTCGGCGTCATTGG | 162-178 | traL |

| XII-yR | GAAGTGGGGTGTTGCTC | 293-277 | traM |

| XII-yF | GAGCAACACCCCACTTC | 277-293 | traM |

| XII-zR | GGAACAATATCGGCGGG | 335-319 | traN |

nt, nucleotides.

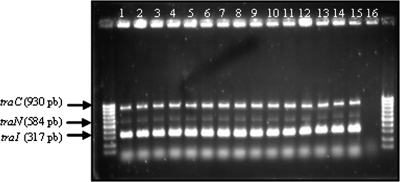

PCR detection of traI, traC, and traN in different Y. ruckeri strains.

Fifteen Y. ruckeri strains were studied in regard to the presence of traI, traC, and traN genes. PCR was performed using the primers traI-1 and traI-2 (previously described), the primers traC-1 (5′-CCACCGGCTCACATACC-3′) and traC-2 (5′-CCGGTTCGCTGCTGTTC-3′), and the primers traN-1 (5′-TGACCGGCTGGCATTTT-3′) and traN-2 (5′-CCTCAAAACGAACCTGT-3′). All PCR reagents were provided by Biotools. The amplification reactions were performed in a Perkin-Elmer 9700 GeneAmp thermocycler with an initial denaturation cycle at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 25 cycles of amplification (denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 48°C for 60 s, and extension at 72°C for 1 min), and a final 7-min elongation step at 72°C. The reaction products corresponding to the three groups were mixed, and 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis was used to separate the generated amplicons.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence accession number for the genes in the GenBank database is EU828793.

RESULTS

Sequence analysis of the Y. ruckeri tra cluster.

The application of IVET to Y. ruckeri allowed the selection of 14 clones, carrying in vivo-induced transcriptional fusions between Y. ruckeri promoters and the promoterless cat and lacZY genes (14). Sequence analysis of the region surrounding the pIVET8 insertion site in one of these ivi clones, iviXII, surprisingly revealed the presence of a partial open reading frame (ORF) encoding a protein with identity to TraI (58%), one of the components of the system Tra encoded by the S. entomophila virulence plasmid pADAP (26). In order to examine more closely the function of this system in Y. ruckeri, the region adjacent to this genetic locus was sequenced. An 8,234-bp DNA segment containing eight adjacent ORFs oriented in the same direction was found. The deduced amino acid sequences of these ORFs showed identities to the proteins encoded by the tra region involved in the transfer of some plasmids, such as pADAP of S. entomophila (ranging from 35 to 58%), pDC3000A of Pseudomonas syringae (ranging from 41 to 62%), pEL60 of Erwinia amylovora (ranging from 26 to 53%), pCTX-M3 of Citrobacter freundii (ranging from 27 to 53%), ColIb-P9 of Shigella sonnei (ranging from 30 to 50%), and the chromosomal icm/dot genes of L. pneumophila (ranging from 27 to 50%) or Coxiella burnetii (ranging from 23 to 34%). By analogy with the genes tra from S. entomophila, the eight ORFs from Y. ruckeri were designated traH-I-J-K-C-L-M-N, referred to here simply as the tra operon or cluster (Fig. 1). The predicted biochemical properties of the tra operon products are similar to the ones described for the same genes found in R64 plasmid described by Komano et al. (29).

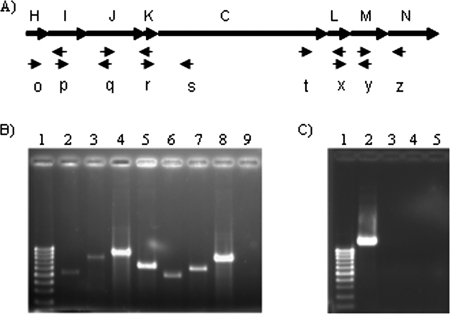

The small size of the intergenic spaces and the absence of putative promoter sequences within the tra cluster suggested that it might be transcribed as a single unit. This is in agreement with the presence of putative promoter, with −35 (5′-TAGTTA-3′), −10 (5′-TATATT-3′), and RBS (5′-AGGCGA-3′) sequences upstream of traH and a stem-loop palindromic sequence located at the end of traN (data not shown). RT-PCR analysis confirmed the prediction that the tra cluster genes form an operon. The results obtained with this analysis are shown in Fig. 2B. Fragments corresponding to the overlapping regions of the eight genes were amplified when RNA from the parental strain was used, confirming that all of the genes are cotranscribed. However, when RNA from the mutant Y. ruckeri 150RtraI strain was used, no mRNA corresponding to the overlapping region traJ-traK was found (Fig. 2C). This result confirms that the traI mutation has a polar effect.

FIG. 2.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of the RT-PCR amplification products showing transcriptional organization. (A) The positions of the primers used within the tra genes of Y. ruckeri are indicated. (B) RT-PCR of Y. ruckeri 150R using the primers oF and pR (lane 2), pF and qR (lane 3), qF and rR (lane 4), rF and sR (lane 5), tF and xR (lane 6), xF and yR (lane 7), and yF and zR (lane 8). (C) RT-PCR using RNA from Y. ruckeri 150R (lane 2) and 150RtraI (lane 3) using the oF and qR primers as a control for traI expression. Lane 4, RT-PCR of Y. ruckeri 150RtraI using qF and rR (overlapping region traJ-traK) to prove that the mutation has a polar effect. Lanes 9 (B) and 5 (C), control reactions to assess DNA contamination in RNA preparations; lane 1 (B and C), the molecular weight marker corresponding to sizes ranging from 1,000 to 100 bp.

The overall G+C content of this cluster, 53.6%, is slightly higher than the 47 to 48% reported for Y. ruckeri, indicating a possible horizontal gene transfer of this region. The genetic organization of the tra genes of Y. ruckeri was almost identical to the tra cluster of the S. entomophila pADAP plasmid (pADAP_08/pADAP_01) and similar to the ones present in C. freundii (pCTX-M3_053/pCTX-M3_061), Erwinia amylovora (pEL60p43/pEL60p50), and Pseudomonas syringae (PSPTOA0043/PSPTO A0052) (Fig. 3). The comparison of the flanking regions of the tra cluster of Y. ruckeri to those from S. entomophila, C. freundii, E. amylovora, and P. syringae hints at their likely evolutionary origin through horizontal gene transfer among these bacteria. Since the tra genes of S. entomophila presented the same genetic organization as the cluster tra of Y. ruckeri and because of the significant level of similarity between them, it is quite possible that the origin of the locus tra of Y. ruckeri is related to that of the tra cluster of pADAP (Fig. 3). In fact, a deletion of the traO-traG region in this plasmid, would explain the organization of the tra genes in Y. ruckeri (Fig. 3). The information collected from the data banks indicated that the cluster described here is not present in any of the three human pathogenic Yersinia species.

FIG. 3.

Genomic organization of the region surrounding the tra operon of Y. ruckeri150R and comparative analysis to that of S. entomophila (pADAP), C. freundii (pCTX-M3), E. amylovora (pEL60), and P. syringae pv. tomato (pDC3000B). Groups of genes are indicated by arrows indicating the direction of transcription. The loci are designated with the letter corresponding to each gene. The Y. ruckeri 150R gene organization lacks the traOPQRTUWXY, excB, trbABC, and traG loci present in S. entomophila, suggesting a deletion event. orf1, PSPTOA0046; orf2, PSPTOA0047, orf3, PSPTOA0061; orf4, PSPTOA0065.

Chromosomal localization of the tra operon in Y. ruckeri.

In order to determine whether the tra cluster in Y. ruckeri 150R was located in the chromosome or a plasmid, both DNA types of this strain were separated in agarose gels (Fig. 4A). Y. ruckeri 150R carried a large plasmid of 75 MDa and a smaller one of 12.7 MDa, as described for most Y. ruckeri strains belonging to serotype O1 (23). When a traI internal fragment was used as a probe for Southern blot analysis, there were hybridization marks in both chromosomal DNA and 75-MDa plasmid (Fig. 4B). It is important to emphasize that the tra genes are part of conjugal transfer systems and, therefore, there can be similar genes in conjugative plasmids. To confirm the localization of the in vivo-induced tra cluster in Y. ruckeri 150R, the chromosomal and plasmid DNA of the Y. ruckeri 150RiviXII strain were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 4C). Southern blotting was carried out with the bla gene from pIVET8 as a probe and, in this case, only a hybridization mark in the chromosomal DNA was obtained (Fig. 4D). Since clone iviXII contains pIVET8 integrated inside the traI coding sequence, this result showed that the tra genes described here and selected by IVET are located in the chromosome.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of the location of the tra operon in Y. ruckeri 150R and Y. ruckeri 150RiviXII. Plasmid (lane 1) and chromosomal (lane 2) DNAs of Y. ruckeri 150R (A) and Y. ruckeri 150RiviXII (C) were separated by 0.75% agarose gel electrophoresis. The relative sizes of the plasmids of Y. ruckeri 150RiviXII were determined by using lambda PstI-digested DNA fragments as molecular markers (left lane) and from the length of their migration compared to plasmids from Y. ruckeri 955 harboring a large plasmid of 75 MDa and a smaller one of 15.5 MDa (23; data not shown). (B) Southern blot analysis of plasmid and chromosomal DNA from Y. ruckeri 150R using an internal fragment of traI as a probe. Hybridization marks appeared in both chromosomal DNA and the 75-MDa plasmid. (D) Southern blot analysis of plasmid and chromosomal DNA from Y. ruckeri 150RiviXII using an internal fragment of bla as a probe. Only one hybridization mark appeared in chromosomal DNA. Lanes 1 and 2 correspond to plasmid and chromosomal DNAs, respectively. Please note that traces of chromosomal DNA were left in the plasmid extraction of Y. ruckeri 150RiviXII (lane 1, C and D).

Medium composition and temperature regulation of the traI promoter.

The Y. ruckeri 150RiviXII strain contains a transcriptional fusion between the promoter that controls the expression of traI and the promoterless lacZY genes (Fig. 1). This clone was used to carry out studies on the regulation of the expression of traI in response to different environmental conditions. The β-galactosidase activity produced by the bacteria grown in M9 at 18°C was considered to be 100%. When the incubation was carried out at 28°C, corresponding to the optimal growth temperature, the β-galactosidase activity decreased by 36% ± 1.92%. In addition, the influence of the medium composition on traI expression was also tested. In this case, the expression decreased by 35.5% ± 1.32% when the microorganism was grown in the complex medium NB. High concentrations of NaCl (250 mM), MgCl2 (25 mM), or CaCl2 (1.25 mM) did not influence the expression of traI (data not shown).

TraI mutation reduces Y. ruckeri virulence.

A traI isogenic mutant strain (traI::pIVET8) was obtained by insertional mutagenesis (Fig. 5A). The mutation was confirmed by Southern blot analysis. After EcoRI digestion of total genomic DNA from the parental and mutant strains, the fragments obtained were hybridized with an internal fragment of traI gene. Whereas a single hybridization band of ∼15 kb appeared in the parental strain, two bands of ca. 11 and 9.2 kb could be seen in the traI mutant (Fig. 5B). Since the plasmid pIVET8 has internal EcoRI sites (Fig. 5A), these patterns of hybridization show that a disruption of the traI gene was obtained by insertion of this vector within the genomic DNA. In conclusion, Southern blotting showed that the integration of the suicide vector containing the traI internal fragment into the chromosome had occurred by a single crossover event. The stability of the mutation in the absence of ampicillin was checked by doing several passes on nonselective medium, followed by comparison of the number of cells able to grow with or without the antibiotic. This same experiment was carried out after every LD50 experiment in order to confirm that the bacteria recovered from the fish had the mutation. In all cases, no significant reversion rate was observed. In addition, the ratio found in the in vitro CI experiments when both strains (parental and mutant) were grown together was approximately 1, indicating that growth of the mutant without antibiotic is similar to that of the parental strain and also that no major reversion occurred when that mutant strain was grown in the absence of antibiotic.

FIG. 5.

Construction of traI isogenic mutant by insertional mutagenesis. (A) Homologous recombination between the 317-bp traI internal fragment from plasmid pTRA1 and the traI gene from the Y. ruckeri 150R chromosome resulted in insertional mutation of traI. Open rectangles, target traI gene; solid rectangles, interrupted traI gene. cat, chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene; lacZY, β-galactosidase and galactoside permease genes; bla, β-lactamase gene. (B) Southern blot analysis of the Y. ruckeri 150R mutated strain. Genomic DNA from the parental strain Y. ruckeri 150R (lane 1) and mutant strain 150RtraI (lane 2) was digested with EcoRI and hybridized with the 317-bp internal traI fragment, previously labeled with digoxigenin as described in Materials and Methods. The hybridizing fragments are indicated with arrows as follows: A, Y. ruckeri 150R 15-kb EcoRI chromosome fragment flanking the traI gene; B and C, 11- and 9.2-kb EcoRI fragments, respectively, from the Y. ruckeri 150RtraI chromosome containing the traI truncated gene.

As previously indicated, TraI of Y. ruckeri displays 30% identity to the DotC protein of L. pneumophila. Phenotypically, the dotC mutant is described as salt resistant compared to the parental strain (38). A similar result was found in the traI::pIVET8 strain of Y. ruckeri. Thus, ca. 10% more cells of the mutant strain than cells of the parental strain were recovered in NB plates supplemented with 250 mM NaCl.

The virulence of the traI::pIVET8 strain was first assessed in an in vivo competition assay in a rainbow trout model. A CI of 0.2 ± 0.07 was obtained after the coinoculation of 105 cells of each strain (parental and traI::pIVET8) in fish weighing 10 to 15 g. This result shows that the mutant strain has significantly greater difficulty growing inside the fish than did the parental strain. However, in vitro competition assays showed that the mutant has no growth defect under optimal laboratory conditions, with an in vitro CI of 1.04 ± 0.18. The means of the LD50 values obtained for the parental strain and mutant traI after 7 days were 4.07 × 104 and 2.69 × 105 CFU per fish, respectively. Therefore, a slight but clear attenuation was found in the mutant strain Y. ruckeri 150RtraI.

The tra genes are present in Y. ruckeri strains from different origins.

PCR detection of traI, traC, and traN genes was carried out with 15 Y. ruckeri strains from different origins. The results showed, as can be observed in Fig. 6, that the three genes were present in all of the strains tested, which suggests that this cluster is conserved in this species. This is especially significant because the 15 strains represented three different plasmid profiles, and this fact thus strengthened the hypothesis of a chromosomal location.

FIG. 6.

PCR detection of traC, traN, and traI genes from different Y. ruckeri strains. Independent PCRs were carried out for each gene. The amplicons obtained were then mixed and separated in a 1.5% agarose gel. The sizes of the amplicons generated were as follows: traC (930 bp), traN (584 bp), and traI (317 bp). Lane 1, strain 146; lane 2, lane strain 147; lane 3, strain 148; lane 4, strain 149; lane 5, strain 150; lane 6, strain 955; lane 7, strain 956; lane 8, strain 35/85; lane 9, strain 13/86; lane 10, strain 43/19; lane 11, strain A100; lane 12, strain A102; lane 13, strain 150/05; lane 14, strain 158/05; lane 15, strain 382/05; lane 16, negative control. Flanking lanes, DNA molecular size markers from 1,000 to 100 bp.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, a cluster of eight genes involved in virulence was identified by analysis of a previously isolated iviXII clone, the product of the application of IVET to Y. ruckeri (14). Nucleotide sequencing, the identities of the translated products, and the genetic organization established that the tra cluster loci of Y. ruckeri are similar to the ones found in plasmid pADAP of S. entomophila (26), pCTX-M3 of C. freundii (31), and pEL60 of E. amylovora (20). In fact, a colinearity and conservation of the sequence of the region surrounding the tra cluster provided some hints about its possible evolution. A deletion could explain the rearrangement undergone by these regions from the pADAP plasmid to Y. ruckeri. Recently, the pYR1 plasmid, which contained a type IV conjugative transfer system, has been described in Y. ruckeri (49). However, the conjugation genes contained in plasmid pYR1 did not show significant identity with the tra genes described here, and their genetic organization is completely different. A Y. enterocolitica self-transmissible plasmid has been characterized (24), and genomic analysis of Y. pestis (44) also revealed the existence of type IV transfer systems in this species. In the case of Y. pseudotuberculosis IP31758, the etiological agent of Far East scarlet-like fever, Eppinger et al. (13) described a plasmid-borne putative type IVB secretion system related to the icm/dot system of L. pneumophila. However, the involvement in virulence of any of these T4SS systems has not been demonstrated thus far. In addition, they do not share a significant similarity with the in vivo-induced tra cluster from Y. ruckeri. These results stress again the uncertain taxonomic position of Y. ruckeri inside the genus Yersinia, as discussed by Bottone et al. (4).

Conjugative plasmids such as pCTX-M3 and pADAP can promote horizontal gene transfer between bacteria. The difference in G+C content between a particular gene cluster and the core genome can be a clue of this phenomenon. This seems to be the case of the Y. ruckeri tra operon, whose G+C content is 53.6%, a value closer to the G+C content of the plasmid pADAP from S. entomophila (50%) and pCTX-M3 from C. freundii (51%) than to the 47% G+C content of the Y. ruckeri genome. This, together with the similarities in genomic organization, suggests that Y. ruckeri, whose ecological niche is close to that of Serratia species, could have acquired this cluster from one of these species and eventually integrate it into the chromosome. This integration event might be a necessary step toward its stabilization in the genome and could be the consequence of the positive selection of virulence-related functions in the pathogen. For instance, in facultative intracellular bacteria such as Y. ruckeri this selection could be necessary for a functional T4SS during the intracellular stage. Thus, mutations in the T4SS chromosomal genes in L. pneumophila, such as dotD, dotC, dotB, or icmT genes (51), counterparts of the traH, traI, traJ, and traK genes, respectively, of Y. ruckeri, result in a defective intracellular growth. It should be emphasized that the presence of other tra clusters harbored by the plasmids present in Y. ruckeri 150 could not be excluded. In fact, when Southern blot hybridization was carried out with an internal fragment of traI as a probe, a band in the 75-MDa plasmid was found. However, all of the results obtained in the present study only refer to the tra operon present in the chromosome.

The expression of the tra operon is transcriptionally regulated by temperature and nutrient availability. Interestingly, as occurred in the case of other Y. ruckeri virulence factors (15, 16), the tra operon is upregulated at 18°C, a condition that resembles that present in water when the bacterial cells are in contact with the fish and might initiate the infection process. Although the differences found in the tra operon expression were not as high as in YhlA hemolysin (16), this result, together with those obtained for the protease Yrp1 (17) and ruckerbactin production (14), clearly establishes that temperature is an important environmental factor regulating the virulence of Y. ruckeri. tra cluster expression was higher in minimal medium than in complex medium, indicating that nutritional stress is a positive factor in its regulation. This result is reminiscent of the findings in other intracellular pathogenic bacteria such as Brucella suis (3) and L. pneumophila (5), in which nutritional limitation could induce the secretion of effector molecules by T4SS to lyse the host cells. When these bacteria are in a rich intracellular environment, replication is the response. Although the basis for the sodium resistance of dot mutants of L. pneumophila is still unknown, some researchers have suggested that the Dot-Icm protein complex may allow the diffusion of sodium into the cytoplasm of the L. pneumophila cells, resulting in a sodium-sensitive phenotype (22, 38). The sodium-resistant phenotype of the traI mutant is similar to the one described for L. pneumophila dot mutants. Therefore, the proteins from both microorganisms might have an identical functional effect. Nevertheless, NaCl did not have any influence on the expression of the tra cluster, suggesting that the sodium resistance mechanism might not be directly related to these loci but rather be an indirect effect of the mutation.

Experiments carried out to determine the stability of the traI insertional mutation showed that, under the assayed conditions and with this particular construction, no reversion of the mutation occurred. These data provide enough support to conclude that the results obtained with the mutant strain are valid in terms of virulence and phenotypic properties. Taking this into account, it can be concluded that the tra operon is a new virulence factor of this bacterium. First, it was initially identified as an ivi gene. Second, a traI mutant strain was approximately 10 times more attenuated than the parental strain and, finally, in vivo competition experiments showed a significantly lower recovery of the traI mutant strain. According to all of the characteristics of the chromosomal tra operon, it is tempting to speculate that it could form part of a T4SS involved in the transfer of virulence factors. Y. pseudotuberculosis harbors a chromosomal pilLMNOPQRSUVW gene cluster involved in the synthesis of type IV pilus that is regulated by environmental factors and contributes to pathogenicity (10). Sequence analysis of the region flanking the tra cluster in Y. ruckeri, particularly upstream of the pilV gene, could help to locate the genes coding for the synthesis of the pilus structure.

The tra operon is present in Y. ruckeri strains isolated from different outbreaks and locations, implying that these genes are likely to play an important role in the biology and pathogenesis of this bacterium. This confirms that Y. ruckeri is a highly homogeneous species at the genetic level, as was previously indicated by different studies (4, 15).

In conclusion, a component of a T4SS, absent from human pathogenic yersiniae, contributes to the virulence of Y. ruckeri and this, together with previously published data (4, 15), strongly supports the idea that the taxonomy of Y. ruckeri should be reconsidered, perhaps as a new genus within Enterobacteriaceae. Further analyses are necessary to identify other components of this T4SS to clarify its role in the environment, and especially during the infection process. In particular, the study of the intracellular stage of Y. ruckeri infection seems to be more interesting in the light of this finding.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the MEC of Spain (AGL2006-07562). J.M. was the recipient of a grant from Oviedo University. A.M., P.R., and D.P.-P. were the recipients of grants from the Spanish Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia.

We thank A. F. Braña for his help in keeping the laboratory equipment and facilities and ProAqua for providing some of the strains used for this study.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 December 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arias, C. R., O. Olivares-Fuster, K. Hayden, C. A. Shoemaker, J. M. Grizzle, and P. H. Klesius. 2007. First report of Yersinia ruckeri biotype 2 in the USA. J. Aquat. Anim. Health 19:35-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Austin, D. A., P. A. W. Robertson, and B. Austin. 2003. Recovery of a new biogroup of Yersinia ruckeri from disease rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss, Walbaum). Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 26:127-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boschironi, M. L., S. Ouahrani-Bettache, V. Foulongne, S. Michaux-Charachon, G. Bourg, A. Allardet-Servent, C. Cazevieille, J. P. Liautard, M. Ramuz, and D. O'Callaghan. 2002. The Brucella suis virB operon is induced intracellularly in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:1544-1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bottone, E. J., H. Bercovier, and H. H. Mollaret. 2005. Genus XLI. Yersinia, p. 838-848. In G. M. Garrity (ed.), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, vol. 2. Springer-Verlag, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byrne, B., and M. S. Swanson. 1998. Expression of Legionella pneumophila virulence traits in response to growth conditions. Infect. Immun. 66:3029-3034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Censini, S., C. Lange, Z. Xiang, J. E. Crabtree, P. Ghiara, M. Borodovsky, R. Rappoundi, and A. Covvacci. 1996. cag, a pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori, encodes type specific and disease-associated virulence factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:14648-14653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christie, P. J. 2001. Type IV secretion: intracellular transfer of macromolecules by systems ancestrally related to conjugation machines. Mol. Microbiol. 40:294-305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christie, P. J., K. Atmakuri, V. Krishnamoorthy, S. Jakubowski, and E. Cascales. 2005. Biogenesis, architecture, and function bacterial type IV secretion systems. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 59:451-485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christie, P. J., and J. P. Vogel. 2000. Bacterial type IV secretion: conjugation systems adapted to deliver effectors molecules to host cells. Trends Microbiol. 8:354-360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collyn, F., M.-A. Lety, S. Nair, V. Escuyer, A. B. Younes, M. Simonet, and M. Marceau. 2002. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis harbors a type IV pilus gene cluster that contributes to pathogenicity. Infect. Immun. 70:6196-6205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coquet, L., P. Cosette, L. Quillet, F. Petit, G. A. Junter, and T. Jouenne. 2002. Occurrence and phenotypic characterization of Yersinia ruckeri strains with biofilm-forming capacity in a rainbow trout farm. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:470-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Covacci, A., and R. Rappuoli. 1993. Pertussis toxin export requires accessory genes located downstream from the pertussis toxin operon. Mol. Microbiol. 8:429-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eppinger, M., M. J. Rosovitz, W. F. Fricke, D. A. Rasko, G. Kokorina, C. Fayolle, L. E. Lindler, E. Carniel, and J. Ravel. 2007. The complete genome sequence of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis IP31758, the causative agent of Far East scarlet-like fever. PLoS Genet. 3:1508-1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernández, L., I. Márquez, and J. A. Guijarro. 2004. Identification of specific in vivo-induced (ivi) genes in Yersinia ruckeri and analysis of ruckerbactin, a catecholate siderophore iron acquisition system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:5199-5207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernández, L., J. Mendez, and J. A. Guijarro. 2007. Molecular virulence mechanisms of the fish pathogen Yersinia ruckeri. Vet. Microbiol. 125:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernández, L., M. Prieto, and J. A. Guijarro. 2007. The iron- and temperature-regulated haemolysin YhlA is a virulence factor of Yersinia ruckeri. Microbiology 153:483-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernández, L., P. Secades, J. R. López, I. Márquez, and J. A. Guijarro. 2002. Isolation and analysis of a protease gene with an ABC transport system in the fish pathogen Yersinia ruckeri: insertional mutagenesis and involvement in virulence. Microbiology 148:2233-2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Figurski, D. H., and D. R. Helinski. 1979. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:1648-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fischer, W., R. Haas, and S. Odenbreit. 2002. Type IV secretion systems in pathogenic bacteria. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 292:159-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foster, G. C., G. C. McGhee, A. L. Jones, and G. W. Sundin. 2004. Nucleotide sequences, genetic organization, and distribution of pEU30, and pEL60 from Erwinia amylovora. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:7539-7544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fouz, B., C. Zarza, and C. Amaro. 2006. First description of non-motile Yersinia ruckeri serovar I strains causing disease in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum), cultured in Spain. J. Fish Dis. 29:339-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao, L. Y., O. S. Harb, and Y. A. Kwalk. 1998. Identification of macrophage-specific infectivity loci (mil) of Legionella pneumophila that are not required for infectivity of protozoa. Infect. Immun. 66:883-892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia, J. A., L. Dominguez, J. L. Larsen, and K. Pedersen. 1998. Ribotyping and plasmid profiling of Yersinia ruckeri. J. Appl. Microbiol. 85:949-955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammerl, J. A., I. Klein, E. Lanka, B. Appel, and S. Hertwig. 2008. Genetic and functional properties of the self-transmissible Yersinia enterocolitica plasmid pYE854, which mobilizes the virulence plasmid pYV. J. Bacteriol. 190:991-1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hertwig, S., I. Klein, J. A. Hammerl, and B. Appel. 2003. Characterisation of two conjugative Yersinia plasmids mobilizing pYV. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 529:35-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hurst, M. R. H., M. O'Callaghan, and T. R. Glare. 2003. Peripheral sequences of the Serratia entomophila pADAP virulence-associated region. Plasmid 50:213-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kado, C. I., and S.-T. Liu. 1981. Rapid procedure for detection and isolation of large and small plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 145:1365-1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kin, S. R., and T. Komano. 1997. The plasmid R64 thin pilus identified as a type IV pilus. J. Bacteriol. 179:3594-3603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Komano, T., T. Yoshida, K. Narahara, and N. Furuya. 2000. The transfer region of Incl1 plasmid R64: similarities between R64 tra and Legionella icm/dot genes. Mol. Microbiol. 35:1348-1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahan, M. J., J. W. Tobias, J. M. Slauch, P. C. Hanna, R. J. Collier, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1995. Antibiotic-based selection for bacterial genes that are specifically induced during infection of a host. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:669-673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mierzejewska, J., A. Kulinska, and G. Jagura-Burdzy. 2007. Functional analysis of replication and stability regions of broad-host-range conjugative plasmid CTX-M3 from the IncL/M incompatibility group. Plasmid 57:95-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics, p. 354. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 33.O'Callagahan, D., C. Cazevieille, A. Alladet-Servent, M. L. Boschiroli, G. Bourg, V. Foulongne, P. Frutos, Y. Kulakov, and M. Ramuz. 1999. A homologue of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB and Bordetella pertussis PtI type IV secretion systems is essential for intracellular survival of Brucella suis. Mol. Microbiol. 33:1210-1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rainey, P. B., D. M. Heithoff, and M. J. Mahan. 1997. Single-step conjugative cloning of bacterial gene fusions involved in microbe-host interactions. Mol. Gen. Genet. 256:84-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reed, L. J., and H. Muench. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 27:493-497. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Romalde, J. L., and A. E. Toranzo. 1993. Pathological activities of Yersinia ruckeri, the enteric redmouth (ERM) bacterium. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 112:291-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Romalde, J. L., R. F. Conchas, and A. E. Toranzo. 1991. Evidence that Yersinia ruckeri possesses a high-affinity iron uptake system. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 80:121-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sadosky, A. B., A. L. A. Wiater, and H. A. Shuman. 1993. Identification of Legionella pneumophila genes required for growth within and killing of human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 61:5361-5373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sambrook, J., D. Russell, and J. Sambrook. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 40.Schoder, G., and C. Dehio. 2005. Virulence-associated type IV secretion system of Bartonella. Trends Microbiol. 13:336-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Segal, G., M. Feldman, and T. Zusman. 2005. The icm/doc type IV secretion systems of Legionella pneumophila and Coxiella burnetii. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 29:65-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seubert, A., R. Hiestand, F. de la Cruz, and C. Dehio. 2003. A bacterial conjugation machinery recruited for pathogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 49:1253-1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simon, R., U. Priefer, and A. Pühler. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram-negative bacteria. Bio/Technology 1:784-791. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Song, Y., Z. Tong, J. Wang, L. Wang, Z. Guo, Y. Han, J. Zhang, D. Pei, D. Zhou, H. Qin, X. Pang, Y. Han, J. Zhai, M. Li, B. Cui, Z. Qi, L. Jin, R. Dai, F. Chen, S. Li, C. Ye, Z. Du, W. Lin, J. Wang, J. Yu, H. Yang, J. Wang, P. Huang, and R. Yang. 2004. Complete genome sequences of Yersinia pestis strain 91001, an isolate avirulent to humans. DNA Res. 11:179-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strauch, E., G. Goelz, D. Knabner, A. Konietzny, E. Lanka, and B. Appel. 2003. A cryptic plasmid of Yersinia enterocolitica encodes a conjugative transfer system related to the regions of CloDF13 mob and incX pil. Microbiology 149:2829-2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thorsen, B. K., O. Enger, S. Norland, and K. A. Hoff. 1992. Long-term starvation survival of Yersinia ruckeri at different salinities studied by microscopical and flow cytometric methods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:1624-1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tobback, E., A. Decostere, K. Hermans, F. Haesebrouck, and K. Chiers. 2007. Yersinia ruckeri infections in salmonid fish. J. Fish Dis. 30:257-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weiss, A. A., F. D. Johnson, and D. L. Burns. 1993. Molecular characterization of an operon required for pertussis toxin secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:2970-2974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Welch, T. J., W. F. Fricke, P. F. McDermott, D. G. White, M. L. Rosso, D. A. Rasko, M. K. Mammel, M. Eppinger, M. J. Rosovitz, D. Wagner, L. Rahalison, J. E. Leclerc, J. M. Hinshaw, L. E. Lindler, T. A. Cebula, E. Carniel, and J. Ravel. 2007. Multiple antimicrobial resistances in plague: an emerging public health risk. PLoS ONE 2:e309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Winans, S. C., D. L. Burns, and P. J. Christie. 1996. Adaptation of a conjugal transfer system for the export of pathogenic macromolecules. Trends Microbiol. 4:64-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yerushalmi, G., T. Zusman, and G. Segal. 2005. Additive effect on intracellular growth by Legionella pneumophila Icm/Dot proteins containing a lipobox motif. Infect. Immun. 73:7578-7587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhu, J., P. M. Oger, B. Schrammeijer, P. J. Hooykaas, S. K. Farrand, and S. C. Winans. 2000. The bases of crown gall tumorigenesis. J. Bacteriol. 182:3885-3895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]