Abstract

Telomerase activity, which has wide expression in cancerous cells, is induced in lung proliferating fibroblasts. It is preferentially expressed in fibroblasts versus myofibroblasts. It is unknown whether regulation of telomerase expression is related to the process of fibroblast differentiation into myofibroblasts. The objective of this study was to clarify such a potential link between telomerase expression and myofibroblast differentiation. Telomerase inhibitor, 3′-azido-2′,3′-dideoxythymidine, or antisense oligonucleotide to the telomerase RNA component was used to inhibit the induced fibroblast telomerase activity. The results showed that inhibition of induced telomerase increased α-smooth muscle actin expression, an indicator of myofibroblast differentiation. In contrast, induction of telomerase by basic fibroblast growth factor inhibited α-smooth muscle actin expression. These findings suggest that the loss of telomerase activity is closely associated with myofibroblast differentiation and possibly functions as a trigger for myofibroblast differentiation. Conversely, expression of telomerase suppresses myofibroblast differentiation.

Keywords: cell differentiation, fibroblast, α-smooth muscle actin, telomerase reverse transcriptase

Telomerase, a specialized RNA-directed DNA polymerase, prevents progressive telomere loss and overcomes replicative senescence by elongating telomere sequences at the termini of chromosome DNA, thus contributing to chromosome stabilization. It is known to be activated during development and immortalization and upon neoplasia (1, 2). In addition to its presence in immortalized and cancerous cells, telomerase has been found to be induced in the cells of injured and inflamed tissue and in certain types of normal cells, including hematopoietic progenitor cells, endometrial cells, and basal cells of skin and cervical keratinocytes (3–6). Early evidence suggests that telomerase activity is associated with cell proliferation. In cells that do express telomerase activity, its expression is intimately related to cell growth. Subsequent reports reveal that telomerase activity is repressed when a variety of different cultured cell types are induced to differentiate in vitro (7–10). Our previous studies indicate that telomerase expression is induced in activated fibroblasts in an animal model of lung injury and fibrosis induced by bleomycin (BLM) (11, 12). There is also corroborating evidence showing that telomerase is induced in silica-induced lung injury, granulation tissue of wound healing (13), and in synoviocytes from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Moreover, there is evidence to suggest that this induction of telomerase activity may be due to basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) (12, 14–16).

Telomerase contains an RNA component and a catalytic subunit (telomerase reverse transcriptase [TERT]). There is abundant evidence to suggest that the regulation of telomerase expression and activity is multifactorial in mammalian cells, involving telomerase gene expression, post-translational protein–protein interaction, and protein phosphorylation. Studies of human TERT expression reveal that it is expressed in a variety of normal cells and tissue with high proliferative capacity, including many types of epithelial cells and hematopoietic precursors and spermatogonia (17). Our previous data show that the induction of telomerase activity in fibrotic pulmonary injury is related with increased numbers of lung fibroblasts, suggesting that induction of telomerase activity may be responsible for extending the life span of injured lung fibroblasts and/or improving and extending their survival. This is consistent with evidence that showed extension of the life span of normal fibroblasts by forced transient expression of human telomerase (18). In lung injury and fibrosis, telomerase is found to be selectively induced in fibroblasts versus myofibroblasts, and this induced telomerase activity is subject to inhibition by IL-4 or transforming growth factor–β1. Suppression of telomerase expression by these cytokines is accompanied by increased expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), an indicator of myofibroblast differentiation (12). There have been additional reports of inhibition of telomerase associated with normal somatic cell differentiation. Thus, the loss of telomerase activity is an early and general response to the induction of terminal differentiation of HL-60 human promyelocytic leukemia cells (8, 9). Additionally, embryonic NT2 precursor cells express telomerase and have longer telomeres than mature neurons lacking in telomerase activity (10). Large losses of telomeric DNA are also observed during differentiation of memory T lymphocytes from precursor cells (19). Thus, loss of telomerase activity is associated with cell differentiation. However, the significance of this reduction or loss of telomerase activity vis-à-vis cell differentiation is unclear, especially with respect to myofibroblast differentiation.

The objective of this study was to explore a possible link between the loss of telomerase activity and myofibroblast differentiation. We sought to determine whether inhibition of telomerase activity triggers differentiation or if increasing telomerase expression suppresses differentiation. The results using the bleomycin-induced model of pulmonary fibrosis revealed that inhibition of telomerase activity or expression by 3′-azido-2′,3′-dideoxythymidine (AZT) treatment was sufficient to induce myofibroblast differentiation, whereas induction of telomerase by bFGF has the converse effect on differentiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Induction of Animal Model and Isolation of Lung Fibroblasts

Female, specific pathogen-free, Fisher 344 rats, 7–8 wk of age, were purchased from Charles River Breeding Laboratories, Inc. (Wilmington, MA). Pulmonary fibrosis was induced by endotracheal injection of 7.5 U/kg body weight of BLM (Blenoxane; Nippon Kayaku Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) in sterile PBS as previously described (11). Control animals received the same volume of PBS only. On Day 21 after BLM treatment, the rats were killed, and the lungs were rapidly dissected out and used for further analyses (see below).

Fibroblasts were isolated from isolated lung tissue by trypsinization as described previously (20). The cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% plasma-derived fetal bovine serum (PDS), 10 ng/ml of epidermal growth factor, and 5 ng/ml of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN). Cells were passaged by trypsinization and used at the third to fifth passage (∼ 20 to ∼ 25 population doubling level) after primary culture. After plating as indicated, the cells were allowed to grow until they were almost (∼ 85%) confluent before being used in the indicated experiments

AZT Treatment of Primary Cultured Fibroblasts

The fibroblasts were plated into 6-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well and treated with 10, 100, 500, and 1,000 μM of AZT (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). After 48 h, the cells were harvested for telomerase activity assay or used for cell proliferation assay at 24 h after treatment with 500 μM AZT. AZT-treated fibroblasts were incubated for 2, 4, 7, and 10 d for cell viability analysis, and Western blotting was used to determine α-smooth muscle actin expression.

Treatment with Antisense Oligonucleotide against Telomerase RNA

Three antisense oligonucleotides (ODN) and their phosphorothiolated (S-ODN) derivatives complementary to the telomerase RNA component were purchased from Operon Technologies, Inc. (Alameda, CA). The sequences were ODN A: 5′-TGAAAGTCAGCGAGAAAAA CA-3′; ODN B: 5′-TCTTCACGGCGGCAGCGGAGT-3′; and ODN C: 5′-GAGTTCCAGGTGCACTTCCCA-3′.

Three corresponding sense oligonucleotides were purchased and used as controls. One day before oligonucleotide transfection, fibroblasts from control and BLM-treated rats were plated into 6-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well. After washing with serum-free DMEM, 900 μl serum-free DMEM was added to each well before transfection. To prepare the transfection complex, the transfection reagent Fugene 6 (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) (3 μl per well) was diluted with serum-free DMEM and allowed to stand for 5 min at room temperature before mixing with 1, 5, or 10 μM of ODNs or S-ODNs, respectively, in a final volume of 100 μl. The mixtures were incubated for 15 min at room temperature to form the complex. The transfection complexes, the control sense oligonucleotides, and Fugene 6–only reagent control were added to the cells. Four hours later, 1 ml of 20% PDS in DMEM with growth factors was added to yield a final PDS concentration of 10%. The fibroblast extracts were harvested after 48 h of incubation for analyses (see below).

Telomerase Activity Assay (Telomeric Repeat Amplification Protocol–Based ELISA)

Telomerase activity was assayed using a telomerase PCR ELISA kit (Roche) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Briefly, cell extracts were prepared by lysing the cultured fibroblasts with ice-cold lysis reagent. The protein concentrations were determined with Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and stored at −80°C until assayed. For each sample, 0.5 μg of total cell protein was added to 25 μl of reaction mixture containing telomerase substrate, including the biotin-labeled P1-TS and P2 primers, and nucleotides, Taq polymerase, and sterile water to a final volume of 50 μl. These mixtures were transferred to a PTC-200 DNA Engine thermal cycler (MJ Research, Inc., Waltham, MA) for primer elongation at 25°C for 25 min, telomerase inactivation at 94°C for 5 min, and 30 cycles of amplification (94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 90 s). Heat treatment of the cell extracts at 80°C for 10 min before the telomeric repeat amplification protocol (TRAP) reaction was used as negative control. The positive control (human kidney 293 cells) was supplied by the assay kit. Five microliters of the PCR products was denatured and hybridized to a digoxigenin-labeled telomeric repeat specific probe on the precoated microtiter plates at 37°C for 2 h with shaking (300 rpm). Anti-digoxigenin peroxidase conjugate and 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate were used for ELISA assay, and the absorbance at 450 nm (with a reference wavelength of 630 nm) was measured using an ELx 800 UV universal microplate reader (Bio-Tek instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT). Samples with an absorbance value of < 0.25 was considered as negative.

Cell Proliferation Assay

Fibroblasts were plated into 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well in a final volume of 100 μl medium. On the next day, 500 μM of AZT was added when ∼ 85% confluent was reached After 48 h of incubation, 50 μl of XTT labeling mixture (XTT Cell Proliferation Kit II; Roche) was added to each well. After an additional 4 h of incubation, cell proliferation was determined by measuring the absorbance at 450 nm with reference wavelength of 690 nm using an ELx 800 UV Universal microplate reader. Only absorbance readings in the linear range (0.4–1.5) were used. Cell counts of selected samples confirmed the validity of the results using this kit.

Cell Viability Determination

The cytotoxic effect of AZT on fibroblasts was evaluated using trypan blue dye exclusion assay (Sigma). After fibroblasts were trypsinized and suspended in Hank's balanced salt solution at Days 2, 4, 7, and 10 after AZT treatment, 0.5 ml of 0.4% trypan blue was transferred to an equal volume of cell suspension. The samples were mixed thoroughly and allowed to stand for 10 min before counting. Stained (nonviable) and unstained (viable) cells were counted separately. The cell viability was expressed as the percentage of viable cells.

Western Blotting Analysis

Western blotting was used to detect α-SMA protein and TERT expression and was performed as previously described (12). Five or 20 μg of protein for α-SMA and TERT, respectively, were loaded onto 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Mouse anti–α-SMA antibody (Roche) and rabbit anti-TERT polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) were used as primary antibodies. HRP-labeled anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK) were used as secondary antibodies. The immunostained bands were visualized using a chemiluminescent substrate (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) and immediately exposed to ECL Hyperfilm (Amersham).

α-SMA Promoter Construct and Luciferase Activity Assay

The rat α-SMA promoter was cloned by PCR from rat genomic DNA with primers 5′-ACGGTCCTTAAGCATGATAT-3′ and 5′-CTTACCCTGATGGCGACTGGCTGG-3′ according to a published sequence (GeneBank S76011). It was inserted into vector pGal3-basic (Promega Corp., Madison, WI) at the Sma site to form the α-SMAp-luc fusion plasmid pGal3-αSMAp (21). The α-SMA promoter activity was evaluated with a dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega). Briefly, fibroblasts were plated into 6-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well in complete growth media. The cells were transfected on the following day with 0.5 μM of S-ODN-A or S-ODN-C per well in serum-free DMEM. The corresponding sense oligonucleotides were used as controls. After 4 h, 2 μg of pGal3-αSMAp or empty vector control, pGal3-basic, were co-transfected with 2 μg control vector pRL-TK (used as control for normalization). After another 4 h, PDS was added to each well to yield a final concentration of 10%. At 24 h after transfection, the media were replaced. After an additional 24 h, the cells were harvested for analysis of enzyme activities. Firefly luciferase (Luc) and Renilla reniformis luciferase (RlLuc) activities were determined in 20 μl of cell lysates by using the dual-luciferase reporter assay system according to the manufacturer's protocol. Luminescent intensity was measured with a Reporter microplate luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA). The readings were in the linear range of the detector (100–10,000 U). Luc activity was normalized to RlLuc activity and presented as relative luciferase activity. The data were shown as fold changes over pGal3-basic.

Microscopic Assessment for Apoptosis and Expression of α-SMA and TERT

Lung fibroblasts from BLM-treated rats (BRFs) were placed into 4-well chamber slides with a density of 3 × 104 cells/well. On the next day, they were starved with DMEM containing 0.5% PDS for 24 h. The cells were then treated with 500 μM of AZT for 2 or 4 d. The cultured cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature followed by washing in two changes of PBS for 5 min each. The cells were postfixed in pre-cooled ethanol:acetic acid (2:1) for 5 min at −20°C and wash twice in PBS for 5 min each.

Cell apoptosis was examined by TUNEL assay using a fluorescence in situ apoptosis detection kit (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA) according to the manufacturer's manual. Briefly, the slides were incubated with digoxigenin-TdT, followed by anti-digoxigenin–FITC conjugate in the dark. The slides were then washed in PBS and immunostained for α-SMA or TERT.

α-SMA and/or TERT immunofluorescence staining was performed with the same slides after apoptosis detection by TUNEL assay as described previously. Mouse anti α-SMA–Cy5 (Sigma) and rabbit anti-rat TERT (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) were used for detection of these antigens. Alexa fluor 546 goat-anti rabbit IgG (Invitrogen) was as secondary antibody in the case of anti-TERT. The slides were mounted with anti-fade Vectashield hard set mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and examined under fluorescence microscopy. More than 500 cells were counted in 10 randomly selected high-power fields (400× magnification). Apoptosis, α-SMA, and TERT-positive cells were counted and expressed as a percentage of total cells counted.

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SE unless otherwise indicated. Differences between means of various treatment and control groups were assessed for statistical significance by ANOVA followed by post hoc analysis using Scheffé's test for comparison between any two groups. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All experiments were repeated at least twice, and representative results were shown.

RESULTS

Effects of AZT and Antisense Oligonucleotides on BLM-Induced Telomerase Activity and TERT Expression in Lung Fibroblasts

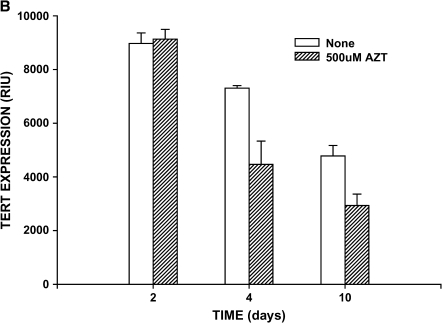

We previously demonstrated that telomerase is induced in a rat model of lung fibrosis and reaches a peak level during active periods of lung fibrosis (11, 12). Consistent with these studies, BRFs exhibited high telomerase activity relative to cells from control rats (lung fibroblasts from saline-treated rats [NRFs]). After 48 h of in vitro treatment with AZT, this induced telomerase activity in BRF was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner, with significant inhibition achieved at a dose as low as 100 μM (Figure 1A). Inhibition by AZT seemed to be maximal (∼ 30%) at a dose of 500 μM. AZT had no significant effect on the baseline telomerase activity in NRF. This inhibition in telomerase activity by 500 μM AZT at 48 h of treatment had no significant effect on TERT expression as measured by Western blotting (Figure 1B). Prolonged treatment with this dose of AZT caused a time-dependent decline in cellular TERT content that was greater than that in untreated cells. Thus, it was possible to significantly, albeit incompletely, suppress telomerase activity with AZT at a time point at which TERT expression was unaffected.

Figure 1.

Effects of AZT on fibroblast telomerase. Lung fibroblasts from control (NRF) and BLM-treated rats (BRF) were treated with the indicated doses of AZT (A) or for the indicated times after the addition of AZT (B). Cell extracts (0.5 μg protein) were assayed for telomerase activity by TRAP-ELISA and expressed as the absorbance at 450 nm minus the absorbance at the reference wavelength of 690 nm. BRF telomerase activity was significantly inhibited only by 500 and 1,000 μM of AZT (P < 0.001), whereas baseline activity in NRF was not affected by AZT (A). In (B), BRFs were treated with AZT for the indicated number of days, and 20 μg of cell lysate was loaded onto each lane for Western blotting to quantify TERT expression. AZT caused significant inhibition (P < 0.05) of TERT expression relative to untreated cells only at Days 4 and 10. Results are shown as mean ± SE of triplicate samples.

Because AZT may have nonspecific effects in addition to suppression of telomerase activity, a more specific means of inhibiting telomerase activity was attempted using antisense oligonucleotides directed at the telomerase RNA component. Three antisense oligonucleotides directed against the rat telomerase RNA template (ODN-A, ODN-B, and ODN-C) and their phosphorothioate derivatives (S-ODN-A, S-ODN-B, and S-ODN-C) were examined for their inhibitory effects on the induced telomerase activity in BRFs. The results showed that only S-ODN-A significantly inhibited (> 50%) telomerase activity in BRFs at 10 μM (Figure 2), whereas derivatized or nonderivatized ODN-B and ODN-C failed to significantly inhibit telomerase activity at identical doses (data not shown). The nonderivatized ODN-A did not have significant effects on telomerase activity. Similar levels of inhibition of bFGF-induced telomerase activity were observed in NRFs (data not shown). In contrast, up to 10 μM of S-ODN-A failed to show any significant effect on telomerase activity in NRFs (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Effects of antisense oligonucleotides on fibroblast telomerase activity. Lung fibroblasts from BRFs and NRF rats were treated with an antisense oligonucleotide directed at telomerase RNA component (ODN-A) or its corresponding phosphorothioate-derivatized form (S-ODN-A) at the indicated doses. After 48 h of incubation, cell extracts were prepared, and telomerase activity was assayed by TRAP-ELISA and expressed as the absorbance at 450 nm minus the absorbance at the reference wavelength of 690 nm. Only inhibition by 10 μM S-ODN-A was statistically significant in BRFs (P < 0.05) (A), whereas baseline telomerase activity in NRF was not affected by treatment with any concentration of S-ODN-A (B). Corresponding sense oligonucleotides did not have significant effects on telomerase activity at identical doses (data not shown). Results are shown as mean ± SE of triplicate samples.

Effects of AZT on Fibroblast Proliferation and Cell Viability

Telomerase activity is positively associated with cell proliferation. To investigate whether inhibition of telomerase activity affected fibroblast proliferation and/or toxicity, the effects of AZT on NRFs and BRFs were examined. Cell proliferation in both cell types was not significantly affected by treatment with AZT at a dose that effectively inhibited telomerase activity in BRFs (Figure 3A). Both cell types were significantly stimulated by PDGF as expected. Thus, inhibition of telomerase activity per se was not sufficient to affect cell proliferation. Moreover, cell viability was > 90% under the same conditions of AZT treatment, although it began to decline at a rate that was faster than untreated control cells after 2 d of incubation (Figure 3B). The decrease in the number of viable cells was observed as early as 4 d after AZT treatment and reached almost 50% reduction by Day 10, whereas control cells showed ∼ 75% viability. Thus, treatment of these cells for 2 d at a dose of 500 μM AZT did not have a toxic effect or affect cell proliferation, but such treatment significantly inhibited telomerase activity in BRFs. These conditions were used to analyze for the effects of telomerase inhibition on myofibroblast differentiation as determined by α-SMA expression.

Figure 3.

Effects of AZT on fibroblast proliferation and viability. (A) Lung fibroblasts from control (NRF) and BLM-treated (BRF) rats were treated with buffer only (Untreated), AZT, or PDGF (used as positive control) at the indicated doses (A). Cell proliferation was determined using the XTT-based assay and expressed as the absorbance 450 nm minus the absorbance at 690 nm. Although BRFs exhibited higher rates of cell proliferation (P < 0.05) under all conditions tested, AZT did not significantly alter the basal proliferation rate. (B) BRFs were treated with AZT for the indicated times, and cell viability was determined by exclusion of Trypan blue dye. Results were expressed as the percentage of viable cells. Relative to untreated cells, AZT-treated cells showed declining cell viability (P < 0.05) starting on Day 4, with further decreases at Days 6 and 10. Results are shown as mean ± SE (n = 5).

Effect of Telomerase Inhibition on Myofibroblast Differentiation

To examine if α-SMA expression and myofibroblast differentiation were induced by the loss of telomerase activity, the effects of inhibiting fibroblast telomerase activity on α-SMA expression was analyzed. In BRFs, treatment with 500 μM of AZT caused significantly higher α-SMA expression than untreated cells, starting on Day 4 of AZT treatment (Figure 4A). This stimulatory effect occurred later than its inhibition of telomerase activity, which occurred as early as Day 2 (see Figure 1). Furthermore, the effect on α-SMA expression occurred when there was significant toxicity developing (Figure 4B). The stimulatory effect on α-SMA expression was noted after correcting for this toxicity. A similar stimulatory effect (> 50% above cells treated with sense oligonucleotide control) was observed when telomerase was inhibited using S-ODN-A (Figure 4B). Treatment with the corresponding sense oligonucleotide did not stimulate α-SMA expression. Under these conditions, the oligonucleotides had no significant effects on cell number or viability (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Effects of telomerase inhibition on α-SMA expression. (A) Lung fibroblasts from BLM-treated animals were treated with AZT for the indicated times, and α-SMA expression was analyzed by Western blotting and expressed as a percentage of that in control (untreated) cells (P < 0.05 starting at the time point of Day 4). (B) Similar analysis as in (A), except that cells were treated with antisense oligonucleotide directed against telomerase RNA component (S-ODN-A, P < 0.05 versus sense control) or its corresponding sense oligonucleotide control (P > 0.05 versus none). Results are shown as mean ± SE of triplicate samples.

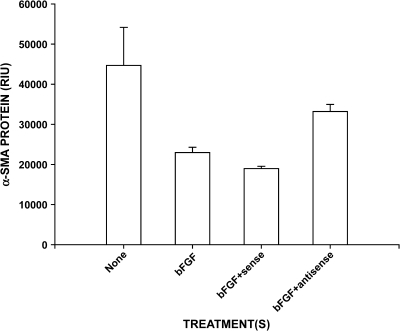

Because bFGF could stimulate telomerase expression in BRF (12), the effect of bFGF-enhanced telomerase expression on α-SMA expression was examined. The results showed significant reduction in α-SMA expression by treatment with bFGF (Figure 5). This reduction was partially reversed by inhibiting telomerase activity using S-ODN-A but not by the corresponding sense oligonucleotide. These findings indicate that the loss of telomerase activity is associated with increased α-SMA expression and may be a potential trigger for myofibroblast differentiation.

Figure 5.

Effect of bFGF and telomerase RNA antisense oligonucleotide on α-SMA expression. Fibroblasts were treated as indicated, and the cell extracts were analyzed by Western blotting for α-SMA protein content. bFGF treatment caused significant reduction in α-SMA content (P < 0.05), which was partially reversed (P < 0.05 versus bFGF alone) by additional treatment with antisense oligonucleotide treatment (S-ODN-A). Co-treatment with the corresponding sense oligonucleotide failed to reverse the effect of bFGF. Results were shown as random integration units (RIU) and expressed as mean ± SE of triplicate samples.

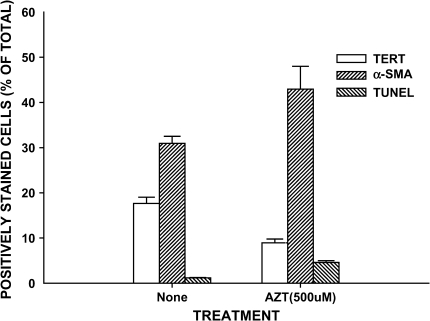

Effects of AZT on Cellular Phenotype Distribution and Apoptosis

Although bulk measurements of total cellular telomerase or α-SMA expression suggest that suppression of telomerase results in increased myofibroblast differentiation, they cannot provide information on expression at the level of individual cells (i.e., the cellular distribution of protein expression or specific phenotype). To provide such cellular distribution data requires analysis of phenotypic expression in individual cells. Thus, the effects of AZT treatment on individual cell apoptosis and phenotype were examined by fluorescence microscopy. Using this approach, cells expressing positive TUNEL, TERT, or α-SMA staining were counted and expressed as a percentage of total cells counted. Because only two colors can be simultaneously analyzed, the same set of cells with identical treatments but plated on different slides was analyzed for TUNEL and TERT or TUNEL and α-SMA expression. The results showed that although the proportion of TERT-positive cells was decreased, the percentages of α-SMA–positive and apoptotic cells were slightly increased after 2 d of AZT treatment (data not shown). The increases in the percentage of cells that are TUNEL and α-SMA–positive were higher and statistically significant by Day 4 (Figure 6). At the latter time point, the proportion of TERT-positive cells decreased by about half (from 19% to 9%), whereas the percentage of apoptotic cells increased from ∼ 1% to ∼ 4%, and the percentage for α-SMA positive cells increased from ∼ 31% to ∼ 44%. No co-localization for apoptosis and α-SMA or apoptosis and TERT signals was observed. Although this may indicate that the cells undergoing apoptosis were α-SMA– and TERT negative, the possibility of loss of these markers upon initiation of apoptosis cannot be ruled out.

Figure 6.

Effect of AZT on cellular phenotype and apoptosis. Rat lung fibroblasts from Day 21 BLM-treated animals were cultured on 4-well chamber slides and treated with buffer only (None) or 500 μM AZT. Four days later, the cells were assayed for TUNEL staining and immunostained with α-SMA or TERT antibodies. The slides were counted for cells expressing these markers at 100× magnification. The counts were expressed as a percentage of the total cells counted. Results are shown as means ± SE in triplicate samples. The effects of AZT on all three parameters were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

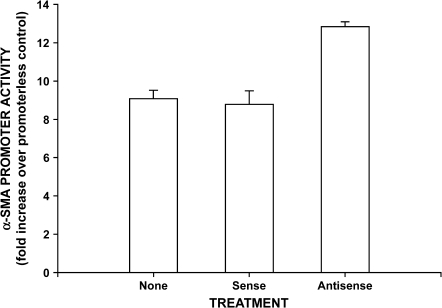

Effects of S-ODN of Telomerase RNA on α-SMA Promoter Activity

To further determine whether the inhibition of telomerase regulated α-SMA expression at the transcriptional level, S-ODN-A was co-transfected into telomerase expressing BRFs transfected with a α-SMA promoter reporter construct. The results showed that inhibition of telomerase by co-transfection with S-ODN-A caused significant stimulation (> 40%) of α-SMA promoter activity, indicating stimulation of gene transcription (Figure 7). The control sense oligonucleotide had no significant effect on promoter activity. Thus, inhibition of telomerase in BRFs caused significant stimulation of α-SMA promoter activity and protein expression, confirming its importance as a trigger or inducer of myofibroblast differentiation in these cells from injured lung.

Figure 7.

Effect of telomerase RNA antisense oligonucleotide on α-SMA promoter activity. Fibroblasts were transfected with the SMA promoter reporter gene construct, followed by transfection with antisense (S-ODN-A) or corresponding control sense oligonucleotide. Cell lysates were collected and analyzed for luciferase activities using a dual-luciferase reporter assay system. Activities were normalized to the promoterless pGal3-basic transfected cells and reported as fold change over pGal3-basic transfected cells. Only the antisense oligonucleotide significantly stimulated α-SMA promoter activity (P < 0.05). Results are expressed as mean ± SE of triplicate samples.

DISCUSSION

We recently reported that telomerase is induced and selectively expressed in lung fibroblasts without appreciable α-SMA expression (i.e., nonmyofibroblasts) in BLM-induced pulmonary fibrosis, suggesting that these telomerase-positive cells may represent an intermediate activated phenotype between the quiescent fibroblasts present in normal lungs and the highly activated myofibroblasts induced in lungs undergoing active fibrosis (11, 12, 22). The differentiation of fibroblasts to α-SMA expressing myofibroblasts and their persistence is thought to result in progressive fibrosis, terminating in end-stage lung disease (22–24). The telomerase activity induced in these fibroblasts from BLM-injured lung is inhibited by treatment with IL-4 or transforming growth factor–β1, two of many known inducers of myofibroblast differentiation. These findings suggest a potential link between telomerase repression and myofibroblast differentiation. It remains unknown whether the loss of telomerase is essential to or a mere consequence of the differentiation process.

To address this issue, the effects of telomerase inhibition on myofibroblast differentiation were examined to determine if loss of telomerase with myofibroblast differentiation was a cause or an effect of the differentiation process itself, as characterized by induction of α-SMA expression. To achieve this goal, two strategies were used to inhibit telomerase, namely to treat cells with AZT or an antisense oligonucleotide directed at the telomerase RNA component. AZT, a nucleoside analog, is well known for its multiple pharmacologic actions, including inhibition of telomerase reverse transcriptase component, DNA polymerase-γ, and is preferentially incorporated into telomeric DNA (25–27). AZT has been confirmed to cause telomere shortening mediated through telomerase inhibition in HeLa, pharyngeal FaDu tumor cells, endothelial cells, and human T lymphocytes (25, 28–30). In this study, we demonstrated that the telomerase inhibitor AZT and an antisense oligonucleotide to telomerase RNA component could significantly inhibit the induced telomerase activity in BRFs even after further telomerase induction by bFGF treatment. Three antisense oligonucleotides directly against rat telomerase RNA template were tested; however, only one, S-ODN-A, was found to significantly inhibit the induced telomerase activity in BRFs. Previously successful inhibition of telomerase activity is achieved by introducing antisense human telomerase RNA component expression vector into HeLa cells (31). There have been subsequent reports on the inhibition of telomerase by antisense DNA against telomerase RNA. However, antisense oligonucleotides, in particular, have short half-lives because they are rapidly degraded by nucleases present in serum and in cells (32, 33). Several modified antisense strategies have been applied using 2′-o-methyl RNA, 2–5A ODN and phosphorothioate-modified ODN (34–36). S-ODN exhibits several advantages, including relatively high nuclease resistance and the capacity to induce degradation of the target sequence by RNase H (36). Our data showed that S-ODN-A was much more potent in inhibiting telomerase activity, whereas the underivatized ODN-A showed only slight inhibitory activity. Thirty percent of inhibition by AZT was not as high as the > 50% of inhibitory effect by S-ODN-A treatment. This may be due to the fact that AZT might have some nonspecific inhibition to the cells.

In contrast to the inhibition of telomerase in BRFs, AZT and S-ODN-A were not able to show significant inhibitory effects on basal level of telomerase activity in control NRFs. This indicated that AZT and S-ODN-A may selectively affect BRFs with high telomerase activity but not NRFs with basal telomerase activity. Having established the optimal conditions for inhibition of telomerase activity, we examined the effects of such inhibition on cell proliferation, viability, and myofibroblast differentiation.

In addition to growth-related regulation of cell function, telomerase activity is associated with the status of cell differentiation (37, 38). A large body of evidence indicates that the inhibition of telomerase is associated with cellular differentiation, although it is unclear if telomerase inhibition is the cause or the result of the differentiation. Our data showed that inhibition of telomerase in BRFs caused a significant increase in α-SMA gene transcription and protein expression, suggesting that the loss of telomerase caused myofibroblast differentiation in these cells. Moreover, analysis of cellular phenotypic distribution indicated that the reduction in the proportion of cells expressing TERT correlated closely with the increase in α-SMA–positive cells, whereas the level of apoptotic cells only increased slightly. Even assuming that the apoptotic cells were all α-SMA negative, the level of increase in apoptosis (∼ 3% difference) remained too low to account for the noted percentage increase (> 10% difference) in α-SMA–positive cells. Thus, because the total number of cells did not increase, most of the α-SMA positive cells or myofibroblasts must have arisen from previously α-SMA–negative cells. Therefore, the reduction in TERT expression induces myofibroblast differentiation.

The totality of the data suggests that inhibition of the induced telomerase activity in these injury-activated fibroblasts was a sufficient trigger for myofibroblast differentiation. These findings are in agreement with previous studies showing that a decrease in telomerase activity is an early event of the differentiation process in diverse cells (8, 10). Moreover, reduced telomerase activity is also reported in a number of cell lines upon induction of terminal differentiation by treatment with diverse agents (9). More recently, retinoic acid–induced HL-60 cell differentiation was shown to be accompanied by an early and rapid telomerase inhibition (39). More importantly, downregulation of telomerase precedes the differentiation of HL60 cells, as monitored by expression of CD11b, a marker for granulocytic differentiation, leading the authors to conclude that differentiation in these cells is induced by the downregulation of telomerase. A comparable situation has also been reported in neuronal cell differentiation (10).

In this study, we demonstrated that stimulation of telomerase expression by treating BRFs with bFGF caused a reduction in α-SMA expression. Thus, upregulation of telomerase resulted in an effect that was opposite to the effect of treatment with telomerase inhibitors. This inhibitory effect of bFGF on α-SMA expression was partially but significantly reversed by antisense inhibition of telomerase. Taken together, these findings suggest a key regulatory role for telomerase in the induction of myofibroblast differentiation. Such a conclusion is also supported by evidence that constitutive overexpression of hTERT in human keratinocytes results in failure to achieve terminal differentiation, although the early epidermal differentiation per se is not impaired (40).

In conclusion, we have shown that inhibition of induced telomerase activity in injured/fibrotic lung fibroblasts promoted myofibroblast differentiation in these cells, whereas further upregulation of telomerase activity by treatment with bFGF had the opposite effect. Thus, changes in telomerase activity proceeded and directly (but negatively) correlated with myofibroblast differentiation. These findings are consistent with the conclusion that in these activated fibroblasts with induced telomerase activity, alterations in the latter activity are key modulators of myofibroblast differentiation, and not vice versa.

Increased fibroblast proliferation and the de novo appearance of myofibroblast are key features of the fibrotic process in fibrotic lung disease. Hence, improvement in the understanding of the mechanisms that give rise to fibroblast population expansion and its differentiation to myofibroblasts would be helpful in providing new insights into the pathogenesis of progressive fibrotic lung disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Bridget McGarry for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants HL31963, HL52285, and HL77297 from the National Institutes of Health and by an award from the Sandler Program in Asthma Research (S.H.P.).

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0252OC on January 19, 2006

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Counter CM, Avilion AA, LeFeuvre CE, Stewart NG, Greider CW, Harley CB, Bacchetti S. Telomere shortening associated with chromosome instability is arrested in immortal cells which express telomerase activity. EMBO J 1992;11:1921–1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu JP. Studies of the molecular mechanisms in the regulation of telomerase activity. FASEB J 1999;13:2091–2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kyo S, Inoue M. Complex regulatory mechanisms of telomerase activity in normal and cancer cells: how can we apply them for cancer therapy? Oncogene 2002;21:688–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hiyama K, Hirai Y, Kyoizumi S, Akiyama M, Hiyama E, Piatyszek MA, Shay JW, Ishioka S, Yamakido M. Activation of telomerase in human lymphocytes and hematopoietic progenitor cells. J Immunol 1995;155:3711–3715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kyo S, Takakura M, Kohama T, Inoue M. Telomerase activity in human endometrium. Cancer Res 1997;57:610–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yasumoto S, Kunimura C, Kikuchi K, Tahara H, Ohji H, Yamamoto H, Ide T, Utakoji T. Telomerase activity in normal human epithelial cells. Oncogene 1996;13:433–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greider CW. Telomerase activity, cell proliferation, and cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998;95:90–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savoysky E, Yoshida K, Ohtomo T, Yamaguchi Y, Akamatsu K, Yamazaki T, Yoshida S, Tsuchiya M. Down-regulation of telomerase activity is an early event in the differentiation of HL60 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1996;226:329–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma HW, Sokoloski JA, Perez JR, Maltese JY, Sartorelli AC, Stein CA, Nichols G, Khaled Z, Telang NT, Narayanan R. Differentiation of immortal cells inhibits telomerase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995;92:12343–12346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kruk PA, Balajee AS, Rao KS, Bohr VA. Telomere reduction and telomerase inactivation during neuronal cell differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1996;224:487–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nozaki Y, Liu T, Hatano K, Gharaee-Kermani M, Phan SH. Induction of telomerase activity in fibroblasts from bleomycin-injured lungs. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2000;23:460–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu T, Nozaki Y, Phan SH. Regulation of telomerase activity in rat lung fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2002;26:534–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osanai M, Tamaki T, Yonekawa M, Kawamura A, Sawada N. Transient increase in telomerase activity of proliferating fibroblasts and endothelial cells in granulation tissue of the human skin. Wound Repair Regen 2002;10:59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim JK, Lim Y, Kim KA, Seo MS, Kim JD, Lee KH, Park CY. Activation of telomerase by silica in rat lung. Toxicol Lett 2000;111:263–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsumuki H, Hasunuma T, Kobata T, Kato T, Uchida A, Nishioka K. Basic FGF-induced activation of telomerase in rheumatoid synoviocytes. Rheumatol Int 2000;19:123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurz DJ, Hong Y, Trivier E, Huang HL, Decary S, Zang GH, Luscher TF, Erusalimsky JD. Fibroblast growth factor-2, but not vascular endothelial growth factor, upregulates telomerase activity in human endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2003;23:748–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolquist KA, Ellisen LW, Counter CM, Meyerson M, Tan LK, Weinberg RA, Haber DA, Gerald WL. Expression of TERT in early premalignant lesions and a subset of cells in normal tissues. Nat Genet 1998;19:182–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinert S, Shay JW, Wright WE. Transient expression of human telomerase extends the life span of normal human fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000;273:1095–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weng NP, Levine BL, June CH, Hodes RJ. Human naive and memory T lymphocytes differ in telomeric length and replicative potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995;92:11091–11094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phan SH, Varani J, Smith D. Rat lung fibroblast collagen metabolism in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest 1985;76:241–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu B, Wu Z, Phan SH. Smad3 mediates transforming growth factor-beta-induced alpha-smooth muscle actin expression. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2003;29:397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phan SH. The myofibroblast in pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2002;122:286S–289S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang HY, Gharaee-Kermani M, Zhang K, Karmiol S, Phan SH. Lung fibroblast alpha-smooth muscle actin expression and contractile phenotype in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Pathol 1996;148:527–537. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang HY, Gharaee-Kermani M, Phan SH. Regulation of lung fibroblast alpha-smooth muscle actin expression, contractile phenotype, and apoptosis by IL-1beta. J Immunol 1997;158:1392–1399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strahl C, Blackburn EH. Effects of reverse transcriptase inhibitors on telomere length and telomerase activity in two immortalized human cell lines. Mol Cell Biol 1996;16:53–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melana SM, Holland JF, Pogo BG. Inhibition of cell growth and telomerase activity of breast cancer cells in vitro by 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine. Clin Cancer Res 1998;4:693–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazumder A, Cooney D, Agbaria R, Gupta M, Pommier Y. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase by 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidylate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994;91:5771–5775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomez DE, Tejera AM, Olivero OA. Irreversible telomere shortening by 3′-azido-2′,3′-dideoxythymidine (AZT) treatment. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1998;246:107–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zaccagnini G, Gaetano C, Della Pietra L, Nanni S, Grasselli A, Mangoni A, Benvenuto R, Fabrizi M, Truffa S, Germani A, et al. Telomerase mediates vascular endothelial growth factor-dependent responsiveness in a rat model of hind limb ischemia. J Biol Chem 2005;280:14790–14798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mo Y, Gan Y, Song S, Johnston J, Xiao X, Wientjes MG, Au JL. Simultaneous targeting of telomeres and telomerase as a cancer therapeutic approach. Cancer Res 2003;63:579–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feng J, Funk WD, Wang SS, Weinrich SL, Avilion AA, Chiu CP, Adams RR, Chang E, Allsopp RC, Yu J. The RNA component of human telomerase. Science 1995;269:1236–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wickstrom E. Oligodeoxynucleotide stability in subcellular extracts and culture media. J Biochem Biophys Methods 1986;13:97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaw JP, Kent K, Bird J, Fishback J, Froehler B. Modified deoxyoligonucleotides stable to exonuclease degradation in serum. Nucleic Acids Res 1991;19:747–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pitts AE, Corey DR. Inhibition of human telomerase by 2'-O-methyl-RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998;95:11549–11554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yatabe N, Kyo S, Kondo S, Kanaya T, Wang Z, Maida Y, Takakura M, Nakamura M, Tanaka M, Inoue M. 2–5A antisense therapy directed against human telomerase RNA inhibits telomerase activity and induces apoptosis without telomere impairment in cervical cancer cells. Cancer Gene Ther 2002;9:624–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tamura Y, Tao M, Miyano-Kurosaki N, Takai K, Takaku H. Inhibition of human telomerase activity by antisense phosphorothioate oligonucleotides encapsulated with the transfection reagent, FuGENE6, in HeLa cells. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev 2000;10:87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cong YS, Wright WE, Shay JW. Human telomerase and its regulation. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2002;66:407–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Armstrong L, Lako M, van Herpe I, Evans J, Saretzki G, Hole N. A role for nucleoprotein Zap3 in the reduction of telomerase activity during embryonic stem cell differentiation. Mech Dev 2004;121:1509–1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu L, Berletch JB, Green JG, Pate MS, Andrews LG, Tollefsbol TO. Telomerase inhibition by retinoids precedes cytodifferentiation of leukemia cells and may contribute to terminal differentiation. Mol Cancer Ther 2004;3:1003–1009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cerezo A, Stark HJ, Moshir S, Boukamp P. Constitutive overexpression of human telomerase reverse transcriptase but not c-myc blocks terminal differentiation in human HaCaT skin keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol 2003;121:110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]