Abstract

Meiotic development (sporulation) in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is induced by nutritional deprivation. Smk1 is a meiosis-specific MAP kinase homolog that controls spore morphogenesis after the meiotic divisions have taken place. In this study, recessive mutants that suppress the sporulation defect of a smk1-2 temperature-sensitive hypomorph were isolated. The suppressors are partial function alleles of CDC25 and CYR1, which encode the Ras GDP/GTP exchange factor and adenyl cyclase, respectively, and MDS3, which encodes a kelch-domain protein previously implicated in Ras/cAMP signaling. Deletion of PMD1, which encodes a Mds3 paralog, also suppressed the smk1-2 phenotype, and a mds3-Δ pmd1-Δ double mutant was a more potent suppressor than either single mutant. The mds3-Δ, pmd1-Δ, and mds3-Δ pmd1-Δ mutants also exhibited mitotic Ras/cAMP phenotypes in the same rank order. The effect of Ras/cAMP pathway mutations on the smk1-2 phenotype required the presence of low levels of glucose. Ime2 is a meiosis-specific CDK-like kinase that is inhibited by low levels of glucose via its carboxy-terminal regulatory domain. IME2-ΔC241, which removes the carboxy-terminal domain of Ime2, exacerbated the smk1-2 spore formation phenotype and prevented cyr1 mutations from suppressing smk1-2. Inhibition of Ime2 in meiotic cells shortly after Smk1 is expressed revealed that Ime2 promotes phosphorylation of Smk1's activation loop. These findings demonstrate that nutrients can negatively regulate Smk1 through the Ras/cAMP pathway and that Ime2 is a key activator of Smk1 signaling.

MEIOSIS is the specialized cell division program used by diploids to produce haploids. Completion of meiosis is coupled to differentiation programs that produce gametes that are specialized for sexual fusion. In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, meiosis is coupled to the formation of spores, which can germinate and fuse with haploid cells of the opposite mating type. Similar to meiosis/gamete formation in higher organisms, sporulation in yeast is tightly regulated at the transcriptional level (Chu et al. 1998; Primig et al. 2000). The transcriptional program of sporulation can be roughly divided into early, middle, and late sporulation-specific genes. Induction of the program is controlled through Ime1, a transcription factor that activates early promoters. Early genes are involved in meiotic S phase, homolog pairing, and genetic recombination. Middle promoters are induced by the Ndt80 transcriptional activator after cells have completed key steps in prophase (Chu and Herskowitz 1998). Middle genes function in the meiotic divisions, cellularization, and spore wall morphogenesis. Late genes are expressed as spores mature and acquire resistance to environmental stresses. The timing of early, middle, and late genes is further temporally diversified to yield as many as 12 subclasses whose expression correlates with the execution of different steps in the program.

Nutritional deprivation is the key signal that causes diploid cells to enter the sporulation program. Starvation for essential nutrients and the presence of a nonfermentable carbon source promote sporulation, while glucose is a potent inhibitor. These signals control the IME1 promoter and also regulate Ime1 post-translationally. Addition of rich media can inhibit sporulation even after meiotic S phase, genetic recombination, and synapotenemal complex formation have taken place (Sherman and Roman 1963; Simchen et al. 1972; Esposito and Esposito 1974; Honigberg et al. 1992; Honigberg and Esposito 1994; Zenvirth et al. 1997; Friedlander et al. 2006). Moreover, such refed cells can exit from the sporulation program and return to mitotic growth (RTG) as long as the commitment point (MI) has not been passed. The overproduction of IME1 in stationary-phase cells can induce meiotic recombination and SC formation, but glucose can stall further progression in late prophase, suggesting that nutritional signals can control later steps in the program through an IME1-independent pathway (Lee and Honigberg 1996).

The multiple nutrient-sensing pathways that control induction and progression of sporulation form an interconnected signaling network that includes the nitrogen-sensing (Tor2), glucose repression, glucose induction, alkaline-sensing (Rim101), and Ras/cAMP pathways (reviewed in Honigberg and Purnapatre 2003). The Ras/cAMP pathway plays a prominent role in this regulatory network. In this pathway, the fraction of Ras that is bound to GTP is controlled by glucose and other signals that modulate exchange of GDP for GTP through the Cdc25 exchange factor (reviewed in Zaman et al. 2008). The active (GTP-bound) form of Ras activates adenyl cyclase (Cyr1), which increases the intracellular concentration of cAMP. cAMP activates PKA (Tpk1, 2, and 3) that dispenses regulatory phosphate to a variety of downstream targets. Mutants in the Ras/cAMP pathway that cause high PKA (growth-promoting) activity repress IME1 transcription and meiotic induction (Kassir et al. 2003). In addition, the Ras/cAMP pathway can negatively regulate Ime1 after it has been translated (Rubin-Bejerano et al. 1996; Rubin-Bejerano et al. 2004; Mallory et al. 2007).

Ime2 is a meiosis-specific cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)-like kinase that regulates multiple steps in meiotic development including meiotic S phase through the Sic1 CDK inhibitor, early gene expression through Ime1, middle gene expression through Ndt80, and the meiotic divisions through the anaphase promoting complex (APC) (reviewed in Honigberg 2004). Ime2 consists of an amino-terminal phosphotransferase domain and a carboxy-terminal regulatory domain. Although the amino acid sequence of the Ime2 phosphotransferase domain is similar to that of the CDK's, it does not require cyclins to become activated. Shortly after Ime2 is produced it is activated through T-loop phosphorylation by the Cak1 CDK activating kinase (Schindler et al. 2003), and its activity is further regulated by phosphorylation of the C-terminal domain as cells progress through meiotic development (Schindler and Winter 2006). In meiotic cells, motifs in the C terminus of Ime2 regulate protein stability in response to low levels of glucose (Purnapatre et al. 2005; Gray et al. 2008). Truncation of the carboxy-terminal third of Ime2 is hyperactivating (Kominami et al. 1993; Sia and Mitchell 1995) and generates a stabilized protein that causes cells to form asci with reduced numbers of spores (dyads and triads) (Sari et al. 2008). In addition, Gpa2, a Gα-protein that is activated when glucose engages the Gpr1 glucose receptor, inhibits Ime2 through its C terminus (Donzeau and Bandlow 1999). It is therefore likely that Ime2 is regulated by nutritional signals and that Ime2 plays a role in controlling meiotic progression in response to nutritional cues. The amino acid sequence of yeast Ime2 is similar to human germ cell-associated kinase (MAK) and intestinal cell kinase (ICK). MAK in rodents is expressed specifically in prophase during male gametogenesis (Matsushime et al. 1990; Koji et al. 1992; Jinno et al. 1993). Human MAK is activated by CCRC (cell cycle related kinase), the kinase with the closest amino acid similarity to yeast Cak1 (Fu et al. 2006), and human ICK can be activated by yeast Cak1 (Fu et al. 2005). In addition, the MAK phosphoacceptor consensus (R-P-X-S/T-P) (Fu et al. 2006) is similar to the Ime2 phosphacceptor consensus (R-P-X-S/T-R/A) (Clifford et al. 2005; Sedgwick et al. 2006; Holt et al. 2007; Moore et al. 2007). These observations suggest that key aspects of the Ime2 pathway have been conserved from yeast to humans.

Smk1 is a MAP kinase homolog that is expressed as a tightly regulated middle sporulation-specific gene (Krisak et al. 1994). Mutants lacking SMK1 complete meiotic S phase, genetic recombination, and MI and MII normally but show defects in spore morphogenesis. Although the sequence of Smk1 is similar to other MAPKs, and it is activated by phosphorylation of a MAPK-like activation loop, its activation does not require members of the MAPKK (Ste7-like) family. Instead, Smk1 is activated through T-loop phosphorylation by Cak1 similar to Ime2 (Wagner et al. 1997; Schaber et al. 2002). Positive regulators of Smk1 activation include Ama1 (McDonald et al. 2005), a meiosis-specific Cdc20-family member that links substrates to the APC (Cooper et al. 2000). It has been proposed that the APCAma1 plays a role in coupling completion of the meiotic divisions to gamete formation (Oelschlaegel et al. 2005; Penkner et al. 2005). Ssp2, a middle meiosis-specific protein that regulates spore formation (Sarkar et al. 2002; Coluccio et al. 2004; Li et al. 2007) is also required for efficient phosphorylation of Smk1's activation loop (McDonald et al. 2005). Thus, while Smk1 is a MAPK family member on the basis of its sequence and its activation by T-loop phosphorylation, it is unlike other MAPKs in several key respects; it is tightly controlled at the transcriptional level, it is activated by a CDK activating kinase, it is regulated by the APC, and its activation state is largely controlled by internally generated signals rather than extracellular ligands.

We previously described a collection of temperature-sensitive smk1 hypomorphs that complete only a subset of events in spore morphogenesis (Wagner et al. 1999). In the current study, mutants in the Ras/cAMP pathway that suppress the spore formation defect of one of these mutants (smk1-2) were isolated. Phenotypic analyses of the suppressors indicate that glucose can signal through the Ras/cAMP pathway to inhibit the Smk1 pathway. We also find that a hyperactivated allele of Ime2 (IME2-ΔC241) prevents Ras/cAMP pathway mutants from suppressing smk1-2 and that Ime2 catalytic activity promotes the activation of Smk1. These observations indicate that glucose can regulate Smk1 through the Ras/cAMP pathway and provide a mechanism to link spore morphogenesis to nutrient fluctuation. These findings also show that Ime2 is a key activator of the Smk1 pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions:

All experiments in this study were carried out in the SK1-genetic background (Table 1). Vegetative cultures were propagated in either SD (0.67% Difco yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 2% glucose) supplemented with nutrients essential for auxotrophic strains, or YEPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose), or YEPA (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% potassium acetate) at 30° unless otherwise indicated. 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) plates are SD plates containing 0.1% 5-FOA and 1.2% uracil. Two different liquid sporulation protocols were used in this study. For rapid sporulation in the absence of glucose, cells were pregrown in YEPA for at least 4 generations to a density of 1 × 107 cells/ml, collected by centrifugation, washed once, and resuspended at 4 × 107 cells/ml in SM (2% potassium acetate, 10 μg/ml adenine, 5 μg/ml histidine, 30 μg/ml leucine, 7.5 μg/ml lysine, 10 μg/ml tryptophan, 5 μg/ml uracil). For liquid sporulation in the presence of glucose, cells were pregrown in YEPD as described above, washed once, and resuspended in SM + 0.05% glucose. Sporulating cultures were maintained with aeration for at least 4 days. Sporulation on solid media was performed by patching or replica plating colonies to YEPD, allowing 12–18 hr pregrowth, and then replica plating to medium containing 2% potassium acetate, 0.1% yeast extract, and 0.05% glucose.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains

| Straina | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| MWY64 | MATa/MATα leu2∷hisG/leu2∷hisG trp1∷hisG/trp1∷hisG lys2/lys2 his3/HIS3 his4/HIS4 ura3/ura3 ho∷LYS2/ho∷LYS2 | This study |

| MDPY10 | MATa/MATα smk1-Δ∷LEU2/smk1-Δ∷LEU2 leu2∷hisG/leu2∷hisG trp1∷hisG/trp1∷hisG lys2/lys2 his4-N/his4-G ura3/ura3 ho∷LYS2/ho∷LYS2 | Wagner et al. (1997) |

| MWY1074 | MATα smk1-2 leu2∷hisG trp1∷hisG lys2 his4-N ura3 ho∷LYS2 | This study |

| EWY1141 | MATasmk1-2 leu2∷hisG trp1∷hisG lys2 his3 ura3 ho∷LYS2 | This study |

| EWY1145 | MATα smk1-2 leu2∷hisG trp1∷hisG lys2 his3 ura3 ho∷LYS2 | This study |

| MWY66 | MATa/MATα smk1-2/smk1-2 leu2∷hisG/leu2∷hisG trp1∷hisG/trp1∷hisG lys2/lys2 his3/HIS3 his4/HIS4 ura3/ura3 ho∷LYS2/ho∷LYS2 | This study |

| MWY69 | MATa/MATα cdc25-ΔC174/cdc25-ΔC174 smk1-2/smk1-2 leu2∷hisG/leu2∷hisG trp1∷hisG/trp1∷hisG lys2/lys2 his3/HIS3 his4/HIS4 ura3/ura3 ho∷LYS2/ho∷LYS2 | This study |

| MWY75 | MATa/MATα mds3-ΔC1226/mds3-ΔC1226 smk1-2/smk1-2 leu2∷hisG/leu2∷hisG trp1∷hisG/trp1∷hisG lys2/lys2 his3/HIS3 his4/HIS4 ura3/ura3 ho∷LYS2/ho∷LYS2 | This study |

| MWY76 | MATa/MATα cyr1-ess/cyr1-ess smk1-2/smk1-2 leu2∷hisG/leu2∷hisG trp1∷hisG/trp1∷hisG lys2/lys2 his3/HIS3 his4/HIS4 ura3/ura3 ho∷LYS2/ho∷LYS2 | This study |

| ALY60 | MATa/MATα SMK1-HA∷kan/SMK1-HA∷kan leu2∷hisG/leu2∷hisG trp1∷hisG/trp1∷hisG lys2/lys2 his4/his4 ura3/ura3 ho∷LYS2/ho∷LYS2 | McDonald et al. (2005) |

| CMY165 | MATa/MATα pmd1∷LEU2/pmd1∷LEU2 his3/his3 leu2∷hisG/leu2∷hisG trp1∷hisG/trp1∷hisG lys2/lys2 ura3/ura3 ho∷LYS2/ho∷LYS2 | This study |

| CMY164 | MATa/MATα mds3∷URA3/mds3∷URA3 his3/his3 leu2∷hisG/leu2∷hisG trp1∷hisG/trp1∷hisG lys2/lys2 ura3/ura3 ho∷LYS2/ho∷LYS2 | This study |

| CMY166 | MATa/MATα mds3∷URA3/mds3∷URA3 pmd1∷LEU2/pmd1∷LEU2 his3/his3 leu2∷hisG/leu2∷hisG trp1∷hisG/trp1∷hisG lys2/lys2 ura3/ura3 ho∷LYS2/ho∷LYS2 | This study |

| CMY153 | MATa/MATα smk1-2/smk1-2 mds3∷URA3/mds3∷URA3 leu2∷hisG/leu2∷hisG trp1∷hisG/trp1∷hisG lys2/lys2 ura3/ura3 ho∷LYS2/ho∷LYS2 arg6/arg6 | This study |

| CMY151 | MATa/MATα smk1-2/smk1-2 pmd1∷LEU2/pmd1∷LEU2 his3/his3 leu2∷hisG/leu2∷hisG trp1∷hisG/trp1∷hisG lys2/lys2 ura3/ura3 ho∷LYS2/ho∷LYS2 arg6/arg6 | This study |

| CMY155 | MATa/MATα smk1-2/smk1-2 pmd1∷LEU2/pmd1∷LEU2 mds3∷URA3/mds3∷URA3 his3/his3 leu2∷hisG/leu2∷hisG trp1∷hisG/trp1∷hisG lys2/lys2 ura3/ura3 ho∷LYS2/ho∷LYS2 ARG6/arg6 | This study |

| CMY143 | MATa/MATα SMK1-HA∷kan/SMK1-HA∷kan ime2-as1∷TRP1/ime2-as1∷TRP1 leu2∷hisG/leu2∷hisG trp1∷hisG/trp1∷hisG lys2/lys2 ura3/ura3 ho∷LYS2/ho∷LYS2 | This study |

| CMY148 | MATa/MATα SMK1-HA∷kan/SMK1-HA∷kan spo11∷hisG-URA3-hisG/spo11∷hisG-URA3-hisG ime2-as1∷TRP1/ime2-as1∷TRP1 mnd2∷kan/mnd2∷kan leu2∷hisG/leu2∷hisG trp1∷hisG/trp1∷hisG lys2/lys2 ura3/ura3 ho∷LYS2/ho∷LYS2 | This study |

| 608 | MATa/MATα IME2-ΔC241-HA∷kan/IME2 leu2∷hisG/leu2∷hisG trp1∷hisG/trp1∷hisG lys2/lys2 his3/his3 ura3/ura3 ho∷LYS2/ho∷LYS2 | Sari et al. (2008) |

| EWY157 | MATa/MATα IME2-ΔC241-HA∷kan/IME2-ΔC241-HA∷kan smk1-2/smk1-2 leu2∷hisG/leu2∷hisG trp1∷hisG/trp1∷hisG lys2/lys2 his3 or HIS3/his3 or HIS3 his4 or HIS4/his4 or HIS4 ura3/ura3 ho∷LYS2/ho∷LYS2 | This study |

| EWY159 | MATa/MATα IME2-ΔC241-HA∷kan/IME2-ΔC241-HA∷kan smk1-2/smk1-2 cyr1-ess/cyr1-ess leu2∷hisG/leu2∷hisG trp1∷hisG/trp1∷hisG lys2/lys2 his3 or HIS3/his3 or HIS3 his4 or HIS4/his4 or HIS4 ura3/ura3 ho∷LYS2/ho∷LYS2 | This study |

| EWY161 | MATa/MATα IME2-ΔC241-HA∷kan/IME2 smk1-2/smk1-2 leu2∷hisG/leu2∷hisG trp1∷hisG/trp1∷hisG lys2/lys2 his3 or HIS3/his3 his4 or HIS4/HIS4 ura3/ura3 ho∷LYS2/ho∷LYS2 | This study |

| EWY163 | MATa/MATα IME2-ΔC241-HA∷kan/IME2 smk1-2/smk1-2 cyr1-ess/cyr1-ess leu2∷hisG/leu2∷hisG trp1∷hisG/trp1∷hisG lys2/lys2 his3 or HIS3/his3 his4 or HIS4/HIS4 ura3/ura3 ho∷LYS2/ho∷LYS2 | This study |

All strains are SK1 genetic background.

Isolation of extragenic suppressor of smk1 (ess) mutants:

Cells (5 × 108) of the smk1-2 ho strain MWY1074 harboring the YCp50-HO (CEN URA3 HO) plasmid (YCP-HO was a gift from J. Broach) were mutagenized with ethylmethane sulfate (EMS) (Lawrence 2002), grown for three generations, and frozen in 15% glycerol in multiple aliquots for further analyses. An aliquot of the pooled mutagenized cells was thawed and revived in YEPD for 12 hr at 30°, and then sporulated en masse in liquid at 26°. Glusulase (500 μl) and glass beads (2 ml) were added directly to a 5-ml sporulated culture, and it was incubated on a rolling drum until the ascal walls were digested and the spores physically separated as determined by phase contrast microscopy. The concentration of spores was determined in a hemocytometer and ∼20,000 individual spores were plated on YEPD plates for germination/growth at 30°. Colonies (diploids due to the HO-induced mating-type switching followed by mating) were replica plated to nitrocellulose filters that were placed colony-side up on SM plates and incubated at the smk1-2 nonpermissive temperature (34°) for 4 days. The filters were then placed colony side up in a petri plate containing 350 ul ascal wall lysis buffer [350 μl 0.1 m Na-citrate, 0.01 m EDTA, 50 mm β-mercaptoethanol, pH 5.8, 70 μl glusulase (Dupont NEE-154, crude solution)], incubated at 37° for 4 hr, blotted on 3M Whatman paper to remove excess liquid, and then placed in a petri plate containing 300 μl concentrated ammonium hydroxide. Fluorescence was viewed under a 304-nm UV light source and photography performed using a blue filter (Kodak, Wratten filter, no. 98). Colonies that were fluorescent-positive were grown on 5-FOA plates to select for cells that had lost the HO plasmid, sporulated, and the spores microdissected to isolate haploid ess smk1-2 strains of both mating types. Each ess mutant was backcrossed to a haploid ESS smk1-2 strain. The ess fluorescence phenotype was followed by mating his4 haploids to a lawn of the cognate ess smk1-2 his3 haploid, selecting diploids (using SD-His medium), sporulating the resulting diploids on SM, and scoring smk1-2 suppression using the fluorescence assay as described above or by microscopic inspection. The data using ess2, ess64, and ess67 in this article were generated using isolates that had each been backcrossed at least four times to a nonmutagenized background.

Microscopy:

For light microscopy, cells were fixed in ethanol and stained with the DNA specific dye DAPI. Samples were viewed and photographed as a wet mount under phase-contrast oil immersion optics using a Nikon Optiphot equipped for epifluorescence.

Vegetative phenotypic characterization:

For the carbon source utilization experiments, cells were grown into exponential phase in YEPD, and fivefold serial dilutions spotted to YEPD, YEPA, YEPGal (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% galactose), or YEPGly [1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glycerol (v/v)]. For nitrogen starvation experiments, cells were grown to exponential phase in YEPD, pelleted and washed with water, resuspended and maintained at 30° in SD minimal media (0.67% Difco yeast nitrogen base without amino acids or ammonium sulfate, 2% glucose) without amino acid supplements for 3 days, and then fivefold serial dilutions spotted on YEPD. To test for glycogen accumulation, strains were grown overnight on YEPD plates that were inverted over solid iodine crystals until differences in the intensity of black staining were apparent.

Genetic mapping experiments:

Strains marked at CDC25 with URA3 were generated by transforming EWY1141 (Table 1) with pAGL2 that had been digested with XhoI. pAGL2 contained a 1433-bp fragment from chromosome XII starting 133 bps downstream of the CDC25 stop codon and extending into the adjacent IMH1 open reading frame (bases 750,660–752,093) cloned into the Kpn1/Xba1 sites of pRS406, respectively. Strains marked at CYR1 with URA3 were generated by transforming EWY1141 with pAGL1 that had been digested with BglII. pAGL1 contained a 1111-bp fragment from chromosome X starting 339 bps downstream of the CYR1 stop codon and extending into the adjacent SYS1 open reading frame (bases 431,570–432,681) cloned into the Kpn1/Xba1 sites of pRS406, respectively.

Tiling array analyses:

Genomic DNA was hybridized to Affymetrix tiling microarrays and the resulting data analyzed using the SNPScanner program as described (Gresham et al. 2006).

Biochemical and cellular assays:

Immunoblot analysis of Smk1-HA was performed as previously described (Schaber et al. 2002). Inhibition of Ime2-as1 was performed using 1Bn-PP1 as described (Benjamin et al. 2003).

RESULTS

Loss-of-function mutations in three different genes suppress a smk1 hypomorph:

Genetic suppression studies of hypomorphic protein kinases have led to the discovery of key signaling molecules and interactions (for review see Nagaraj and Banerjee 2004). Recessive suppressors are most often associated with upstream signaling components that negatively regulate a signaling pathway. In a previous study we generated a series of hypomorphic mutants in the Smk1 MAPK that are temperature sensitive for spore wall formation (Wagner et al. 1999). In the present study we used one of these hypomorphic mutants (smk1-2) to identify negative regulators of Smk1.

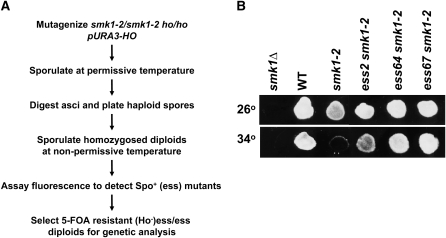

A complication in isolating recessive suppressors of smk1 is that meiosis is normally restricted to diploids. We used a genetic strategy that relies on the conditional smk1 phenotype, HO-induced mating-type switching, and self-mating, to homozygose mutations in the smk1-2 temperature-sensitive background so that recessive suppressors can be scored (Figure 1A). A smk1-2 ho strain (MWY1074) harboring HO on a URA3 selectable plasmid (pHO) was mutagenized, sporulated at the permissive temperature, and enzymatically digested to release individual spores that were then plated on rich (YEPD) medium. pHO in the spore colonies initiates mating-type switching, mating, and diploid formation. Because the colonies were derived from a single haploid spore, the diploids were homozygous at all loci (except MAT). These colonies were then transferred to a filter that was placed on solid sporulation medium and incubated at the smk1-2 nonpermissive temperature. Colonies that were able to form spores were identified using a fluorescence assay that detects dityrosine, a major component of the outer layer of the spore wall that emits visible radiation when excited by ultraviolet illumination. When sporulated at the nonpermissive temperature, smk1-2 mutants exhibit reduced fluorescence in this assay (Figure 1B). We screened 20,000 colonies and identified 72 fluorescent-positive mutants for further testing. Of this initial set we chose 12 mutants that reproducibly fluoresced above the level seen in the starting (smk1-2) strain. All of these mutants exhibited suppression of the smk1-2 spore formation defect at 34° as assayed using phase contrast microsopy.

Figure 1.—

Isolation of extragenic suppressors of smk1 (ess mutants). (A) Strategy for homozygosis and scoring suppressor mutations of the smk1-2 sporulation phenotype (see text for details). (B) Flourescence assay of suppressor strains. The indicated strains were grown on YEPD medium at 30° and sporulated for 4 days at the permissive temperature (26°) or the nonpermissive temperature (34°) on a nitrocellulose filter that was then processed for fluorescence visualization.

To test whether the mutants are dominant or recessive and to sort the mutants into complementation groups, derivatives of the mutants lacking pHO were selected using 5-FOA, sporulated at the permissive temperature, and stable (nonswitching) haploids isolated. Crosses of the stable haploid suppressor mutants to derivatives of the smk1-2 starting strain (EWY1141 and EWY1145) showed that all of the mutants are recessive. The 12 suppressor mutants were crossed in all pair-wise combinations. Fluorescence assays and microsopic examination of the resulting diploids sporulated at the nonpermissive temperature revealed that they fell into three complementation groups. Group 1 consists of 10 members and groups 2 and 3 each consist of a single member. Outcrosses of a representative member of each complementation group through a smk1-Δ∷LEU2 tester strain (haploid parents of MDPY10) demonstrated that the suppressor mutants are unlinked to SMK1. Thus, these mutants are extragenic mutational suppressors of smk1 mutants and will be referred to as ess mutants below. We selected the strongest mutant from complementation group 1 (ess2), and the group 2 and 3 mutants (ess64 and ess67) for further analyses. A representative fluorescence assay of these mutants is shown in Figure 1B. The ess2, -64 and -67 mutants showed no observable suppression of a smk1 null (smk1∷LEU2) mutant and showed significant suppression of two other partial-function smk1 alleles (smk1-4 and smk1-7). Thus, the suppressor mutants are not allele specific and do not appear to be bypass mutants.

To test whether the suppressed strains completed the meiotic divisions, cells processed in parallel with the fluorescence assay shown in Figure 1B were stained with DAPI and examined microscopically. The ess mutations had only modest effects on meiosis as judged by DAPI staining (Table 2). In contrast, the ess mutants had a dramatic effect on spore formation in these same cells and specifically suppressed the smk1-2 spore formation defect as assayed using the fluorescence assay (Figure 1B) and as assayed by phase contrast microscopy (Table 2; also see Figure 4, A and B). Indistinguishable results were obtained when cells were assayed after incubation on sporulation medium for longer times (5 or 6 days) demonstrating that these results represent an end-stage phenotype. Thus, under the conditions tested, ess mutants specifically suppressed the spore formation defect of the smk1-2 strain.

TABLE 2.

ess alleles suppress smk1 spore formation defects in a glucose-dependent manner

| YEPD/SPO-Da

|

YEPA/SPOb

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26°

|

34°

|

26°

|

34°

|

|||||

| Strain | Meiosisc (%) | Sporesd (%) | Meiosis (%) | Spores (%) | Meiosis (%) | Spores (%) | Meiosis (%) | Spores (%) |

| smk1-Δ ESS | 68 | 0 | 46 | 0 | 73 | 0 | 65 | 0 |

| SMK1 ESS | 55 | 90 | 59 | 85 | 93 | 100 | 86 | 96 |

| smk1-2 ESS | 67 | 67 | 52 | 13 | 83 | 78 | 78 | 6 |

| smk1-2 ess2 | 68 | 92 | 58 | 78 | NAe | NA | NA | NA |

| smk1-2 ess64 | 65 | 82 | 63 | 88 | 86 | 75 | 81 | 10 |

| smk1-2 ess67 | 52 | 85 | 75 | 85 | 91 | 85 | 86 | 9 |

Strains were pregrown on solid YEPD overnight, transferred to solid sporulation medium containing 0.05% glucose, and incubated at the smk1-2 permissive (26°) or nonpermissive (34°) temperature for 4 days. Subsequently, cells were fixed in ethanol, stained with the DNA-specific dye DAPI, and viewed by phase contrast/fluorescence microscopy. The strains were processed in parallel with the fluorescence assay shown in Figure 1 for comparison. At least 200 cells were viewed for each strain.

Strains were pregrown in liquid YEPA medium to early log phase, transferred to sporulation medium lacking glucose, and assayed as described above.

Meiosis was scored as the percentage of cells that contained multiple DAPI-stained foci.

Spore formation was scored as the percentage of cells that had completed meiosis and also exhibited spores under phase-contrast microscopy.

The ess2 strain initiated sporulation precociously during pregrowth in YEPA and was therefore not assayed.

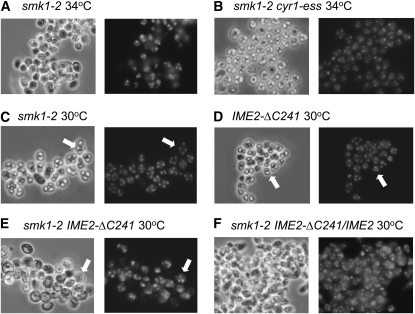

Figure 4.—

IME2-ΔC241 exacerbates the smk1-2 sporulation phenotype. The indicated strains were pregrown in YEPD, sporulated, stained with DAPI, and photographed using phase-contrast microscopy. All strains are homozygous except for the IME2-ΔC241/IME2 strain in F as indicated. Note the predominance of asci containing four refractile spores formed in the smk1-2 strain at the semipermissive temperature (arrows in C), the asci containing two refractile spores and two nuclei that are not contained in spore walls in the IME2-ΔC241/IME2-ΔC241 strain (arrows in D), and asci containing four meiotic products and the absence of refractile spores in the homozygous IME2-ΔC241/IME2-ΔC241 smk1-2/smk1-2 strain (arrows in E).

Suppression of smk1-2 by ess requires glucose:

The suppression screen described above was carried out using cells that had been pre-grown on medium containing glucose (YEPD) and transferred to sporulation medium containing 0.05% glucose. The smk1-2 phenotype does not require the presence of glucose since smk1-2 is also sporulation defective when cells are pregrown in medium in which acetate is the sole carbon source (YEPA) and transferred to sporulation media lacking glucose (Wagner et al. 1997, 1999). We tested the phenotypes of the mutants using the YEPA/no-glucose regimen and found that the spore formation phenotypes of the ess64 smk1-2, ess67 smk1-2, and ESS smk1-2 strains were indistinguishable as judged microscopically (Table 2) and using the fluorescence assay (data not shown). These data indicate that the ability of ess64 and ess67 mutants to modify the smk1-2 sporulation phenotype requires glucose. We were unable to test the suppression phenotype of ess2 since this mutant sporulated precociously when transferred to YEPA.

ess mutants show Ras/cAMP-like phenotypes:

A number of lines of evidence implicated ess mutants in the Ras/cAMP pathway. First, the Ras/cAMP pathway responds to glucose and the suppression of smk1-2 by ess64 and ess67 is seen when low levels of glucose are present but not when glucose is absent. Second, Ras/cAMP signaling mutants that cause a low PKA state sporulate precociously in YEPA (Matsumoto et al. 1983), similar to the ess2 mutant. Third, when ess/ESS asci were microdissected, the ess spores were delayed in germination on YEPD medium with ess2 being slower than ess67, and ess67 slower than ess64 (which was only slightly slower than wild type). Fourth, ess mutants were defective in the recovery from nitrogen starvation and formed small colonies on media containing nonfermentable carbon sources (glycerol and acetate). Fifth, ess mutants also accumulated increased levels of starch as measured by iodine vapor staining (Figure 2). Sixth, when the ess mutants were grown in glucose-containing (YPD) medium for extended times they formed spores that were not observed in wild-type strains (Table 3). Slow germination, premature induction of meiosis, defects in recovery from nutritional deprivation, and increased starch accumulation are all hallmarks of Ras/cAMP pathway mutants that cause a low PKA (growth inhibitory) phenotype.

Figure 2.—

ess mutants hyperaccumulate starch. The indicated haploid strains were grown overnight on YEPD medium, stained with iodine vapors, and photographed. The intensity of black staining correlates with the relative level of starch, a diagnostic phenotype of mitotic yeast strains that are deficient in PKA.

TABLE 3.

ess mutants hypersporulate in nutrient-rich conditions

Number of days of growth in YEPD liquid medium at 30°. Day 0 cells were analyzed at mid-log phase.

Percentage of cells that initiated or completed sporulation as evidenced by phase contrast and fluorescence microscopy of DAPI-stained cells (300 cells counted for each data point).

ess2 and ess67 are alleles of CDC25 and CYR1, respectively:

CDC25 encodes the GDP/GTP exchange factor (GEF) for Ras1 and Ras2 and CYR1 encodes adenyl cyclase. Recessive cdc25 and cyr1 mutations can cause decreased PKA activity and phenotypes similar to the ess phenotypes described above. We tested whether ess2, ess64, and ess67 are genetically linked to CDC25 or CYR1. For these experiments a URA3 marker was inserted adjacent to either CDC25 or CYR1 in a smk1-2 ESS strain and the resulting haploid crossed through the ess2, -64, or -67 isolates.

All ura3 meiotic segregants from the ess2/CDC25-URA3 diploids showed increased starch/iodine staining and all URA3 segregants showed normal starch iodine staining (n = 64 haploids tested). Thus, ess2 is linked to CDC25. Nucleotide sequencing of PCR products revealed that the CDC25 gene in the ess2 strain contains a substitution in codon 1415 that changes a tryptophan (TGG) codon to a termination (TGA) codon. Thus, the ess2 mutation removes 174 C-terminal residues from the 1589 residue Cdc25 protein. The ess2 mutation will therefore be referred to as cdc25-ΔC174 below. The C-terminal third of Cdc25 contains the catalytic domain as well as residues required for its membrane localization. The phenotypic analyses suggest that Cdc25-ΔC174 is a crippled protein that causes a reduction in the fraction of Ras that is active (GTP bound) but that it is still able to support vegetative growth since the cdc25-ΔC174 haploid strain grows only slightly slower than wild-type haploids on rich (YEPD) medium (data not shown).

All ura3 meiotic segregants from the ess67/CYR1-URA3 diploids showed increased starch/iodine staining and all URA3 segregants showed normal starch iodine staining (n = 60 haploid segregants tested). In addition, a ess67 smk1-2 diploid transformed with a low-copy CYR1 plasmid no longer suppressed the smk1-2 phenotype. Thus, ess67 is allelic to CYR1 and is referred to as cyr1-ess below.

ess64 is an allele of MDS3:

ess64 was shown to be unlinked to CDC25, CYR1, RAS1, or RAS2 using the same genetic linkage approach described above. We compared the DNA from ess64 and a co-isogenic (wild-type) control strain using Affymetrix tiling arrays (Gresham et al. 2006). Data from these analyses predicted a G783 substitution in MDS3. This mutation was a strong candidate for a causative ess64 substitution since (1) G783A is predicted to introduce a premature termination codon that would truncate 1226 amino acids of the 1487-residue-long protein (the EMS mutagen causes transitions and is thus predicted to cause G → A changes) and (2) MDS3 has been shown to negatively regulate early sporulation-specific genes and shows genetic interactions with mutants in RAS2 (Benni and Neigeborn 1997). To test whether MDS3 is allelic to ess64 we sequenced the region of MDS3 spanning G783 in meiotic segregants from an ess64/ESS64 diploid. In all cases a G783A form of MDS3 segregated with the increased iodine-staining phenotype (12 total haploids tested). Thus, ess64 is allelic to MDS3 and we refer to ess64 hereafter as mds3-ΔC1226.

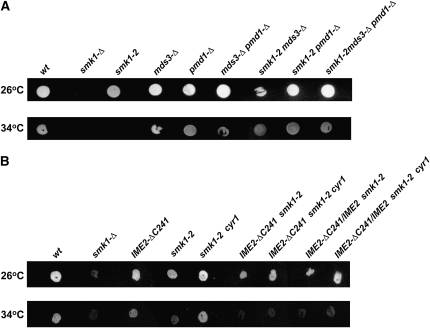

mds3-Δ and pmd1-Δ suppress smk1-2:

MDS3 is a nonessential gene that has previously been shown to negatively regulate IME1 and early sporulation-specific gene expression (Benni and Neigeborn 1997). PMD1 is a functionally redundant MDS3 paralog (predicted amino acid sequences of Pmd1 and Mds3 are 47% identical). In addition, a mds3 pmd1 double mutant has a slow growth phenotype on nonfermentable carbon sources, it sporulates precociously, and the sporulation phenotypes are suppressed by a constitutively active mutant in RAS2 (Benni and Neigeborn 1997). We tested whether mds3-Δ and pmd1-Δ deletions suppress the sporulation defect of smk1-2. The single mds3, pmd1, or double mds3 pmd1 deletions suppressed the fluorescence defect of smk1-2 (Figure 3A). Microscopic examination indicated that the mds3 pmd1 double mutant was a more potent suppressor than either single mutant. These deletions also increased starch accumulation in mitotic cells in the same rank order (Figure 2). Thus, the Mds3/Pmd1 proteins appear to be important regulators of the Ras/cAMP pathway in mitosis and in meiosis.

Figure 3.—

Mutations in Ras/cAMP pathway components and IME2 modify the smk1-2 fluorescence phenotype. (A) Deletion of MDS3 and/or PMD1 suppress the sporulation phenotype of smk1-2. Homozygous diploid strains of the indicated genotype were grown on YEPD, sporulated at the smk1-2 permissive temperature (26°) or nonpermissive temperature (34°) for 4 days, and processed using the fluorescence assay. (B) The C-terminal domain of Ime2 is required for cyr1-ess to suppress smk1-2. Diploid cells of the indicated genotype were assayed as described in A. All strains are homozygous except for the IME2-ΔC241/IME2 strains as indicated.

ess suppression of smk1-2 is distinct from meiotic induction:

The results described thus far demonstrate that mutations that are predicted to cause reduced PKA activity can suppress the sporulation defect of a weakened Smk1 mutant. It is well known that the Ras/cAMP pathway regulates meiotic induction. Indeed, when cells were pregrown in liquid YEPD medium and transferred to sporulation medium supplemented with 0.05% glucose, 50% of the cdc25-ΔC174, cyr1-ess, or mds3-ΔC261 cells completed both nuclear divisions by 9, 11, and 16 hr, respectively, while the wild-type strain required 35 hr. The advanced meiotic kinetics were also affected by the concentration of glucose in the sporulation media (increasing glucose to 0.2% caused slower meiosis in all the strains but did not alter the rank order in which the strains completed meiosis and sporulation). The increased sporulation seen in the Ras/cAMP mutants that had been grown into stationary phase in YEPD are consistent with these observations (Table 3). These data suggest that the Ras/cAMP mutants initiate meiosis at different thresholds of glucose-dependent signaling. The Ras/cAMP pathway controls meiotic initiation via the IME1 pathway. However, SMK1 is expressed as a middle-meiotic gene starting in late prophase long after initiation of the program has taken place. Although the Ras/cAMP pathway suppressor strains completed meiosis earlier than wild type, all the strains can complete meiosis to similar extents. It is therefore unlikely that the suppression of smk1-2 can be explained solely through the effect of the Ras/cAMP pathway mutants on the initiation of meiosis. These data indicate that the Ras/cAMP pathway regulates the Smk1 pathway after meiotic induction has occurred.

IME2-ΔC241 exacerbates the smk1-2 phenotype:

Ime2 consists of an amino-terminal phosphotransferase domain and a carboxy-terminal domain. Glucose has been shown to negatively regulate Ime2 via the carboxy-terminal domain (Donzeau and Bandlow 1999; Purnapatre et al. 2005). It has also been shown that IME2-ΔC241, which truncates the carboxy-terminal domain, can function in a dominant manner to promote skipped spore packaging and thus increase the frequency of asci containing dyads and triads (Sari et al. 2008). These connections between glucose signaling, spore packaging, and the C-terminal regulatory domain of Ime2 prompted us to test for genetic interactions between cyr1-ess, smk1-2, and IME2-ΔC241.

Although an IME2-ΔC241 strain forms an increased frequency of asci containing only two or three spores (Sari et al. 2008), the spores that are formed appear indistinguishable from those found in wild-type tetrads by light microscopy and they are resistant to glusulase digestion, a relatively stringent functional assay for spore wall formation. Thus, the hyperactivating IME2-ΔC241 mutant does not appear to be compromised in its ability to assemble spore walls but does appear to skip steps that occur early in the spore morphogenesis program. While smk1-2 and IME2-ΔC241 cells form morphologically normal spores at 30°, the frequency of morphologically normal spores produced by the smk1-2 IME2-ΔC241 double mutant was reduced (Figure 4, C–E). The IME2-ΔC241 heterozygous background also exacerbated the smk1-2 defect (although not as severely as the homozygous background) (Figure 4F). The enhancement of the smk1-2 phenotype by IME2-ΔC241 at 30° was observed irrespective of whether cells were sporulated in the presence or absence of glucose. These data indicate that while the C terminus of Ime2 is dispensable for the spore formation pathway in wild-type cells that it plays an important role in spore morphogenesis when Smk1 activity is compromised.

The C terminus of Ime2 is required for suppression:

We also tested whether cyr1-ess was able to suppress smk1-2 in the IME2-ΔC241 background. In contrast to the IME2 background, the smk1-2 fluorescence-defective phenotype was unaffected by cyr1-ess in the IME2-ΔC241 homozygous or heterozygous backgrounds (Figure 3B). In addition, while the sporulation phenotypes of smk1-2 CYR1 and smk1-2 cyr1-ess cells were readily distinguishable microscopically (Figure 4, A and B), the sporulation phenotypes of IME2-ΔC241 smk1-2 CYR1 and IME2-ΔC241 smk1-2 cyr1-ess were indistinguishable at a range of temperatures (data not shown). Although other explanations are possible, these observations are consistent with the C terminus of Ime2 being a regulatory target of the Ras/cAMP pathway that influences Smk1 activity.

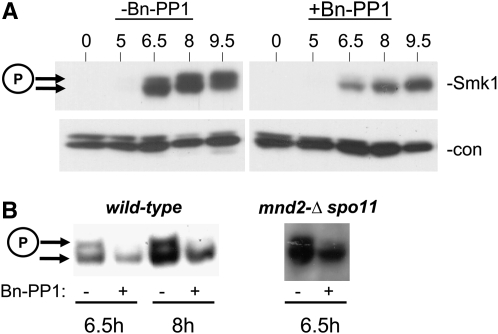

Ime2 promotes Smk1 activation:

The genetic interactions between IME2-ΔC241, cyr1-ess, and smk1-2 raised the possibility that Ime2 can regulate the activation of Smk1. Smk1 is phosphorylated in its activation loop and the phosphorylated form migrates more slowly in electrophoretic gels than the unphosphorylated form. A complexity in testing whether Ime2 regulates Smk1 activation is that Ime2 is required for meiotic induction and S phase. Thus, eliminating IME2 blocks cells prior to the stage when Smk1 is expressed. We used an allele of IME2 (ime2-as1) that is specifically sensitized to the cell-permeable ATP analog Bn-PP1 (Benjamin et al. 2003) to test whether Ime2 can regulate Smk1's activation state. In these experiments, an ime2-as1 SMK1-HA homozygous diploid was pregrown in YEPA and transferred to sporulation medium to induce rapid sporulation. After the culture had been incubated in sporulation medium for 4.5 hr, the Bn-PP1 inhibitor or vehicle alone (DMSO) was added. At this time, meiotic S phase had been completed, most cells were in prophase, and Smk1 had not yet been expressed. Cells were collected at various times after addition of the inhibitor and Smk1-HA electrophoretic migration was monitored by an immunoblot assay. As shown in Figure 5A, Smk1 expression was induced between 5 and 6.5 hr in the control samples. At 6.5 hr, the fraction of active Smk1-HA was low and it increased thereafter. In the Bn-PP1-treated samples, the overall level of Smk1-HA was lower than that seen in the untreated samples, consistent with Ime2's role in promoting middle meiotic gene expression. Importantly, the Bn-PP1-treated cells showed a dramatic reduction in the fraction of Smk1 that had been phosphorylated. We also tested the addition of the inhibitor later (at 5.5 hr) and withdrew samples at various times. The reduction in the fraction of Smk1 that was phosphorylated could be observed within 30 min of inhibitor addition in these experiments but was more readily observed at 1 or 2 hr after inhibitor addition (Figure 5B). Most Smk1-HA activation occurs between 5.5 and 7.5 hr in untreated cells as the level of Smk1-HA is increasing. Addition of the inhibitor after 7.5 hr, when Smk1-HA was maximally activated, had no effect on Smk1's activation state (data not shown). These data indicate that Ime2 catalytic activity promotes the phosphorylation of Smk1's activation loop but that it is not required for maintenance of the activated state. These observations imply that Ime2 promotes an irreversible step that is required for the phosphorylation of Smk1's activation loop.

Figure 5.—

Ime2 promotes Smk1 activation. (A) An ime2-as1 SMK1-HA homozygous diploid was pregrown in YEPA and transferred to sporulation medium to induce rapid sporulation. At 4.5 hr, Bn-PP1 in DMSO (+) or DMSO alone (−) was added and cells were incubated at 30°. Cells were withdrawn at the indicated times, and total cellular extracts were prepared and analyzed by Western immunoblot using an HA antibody to detect Smk1-HA (−Smk1). The same filter was subsequently analyzed using a PSTAIRE antibody, which detects a closely spaced doublet consisting of Cdc28 and Pho85 to control for total protein (−con). (B) Same as in A, except that Bn-PP1 was added at 5.5 hr when Smk1 protein levels were higher, and cellular extracts analyzed at 6.5 or 8.5 hr as indicated. The mnd2-Δ strain was also spo11-Δ to prevent checkpoint-mediated arrest due to the unregulated activation of Ama1. The phosphorylated (active) form of Smk1-HA is indicated with a circled P.

Ime2 regulates Smk1 activation in an Mnd2-independent pathway:

We previously demonstrated that Ama1, a meiosis-specific member of the Cdc20 family of targeting subunits of the anaphase promoting complex, positively regulates Smk1 activation (McDonald et al. 2005). Mnd2 is a subunit of the APC that specifically inhibits Ama1 (Oelschlaegel et al. 2005; Penkner et al. 2005). Ime2 has a relatively stringent phosphoacceptor motif requirement of R-P-X-S/T-A/R (phosphoacceptor residue can be either S or T as indicated where the −1 “X” position can be any residue) (Clifford et al. 2005; Sedgwick et al. 2006; Holt et al. 2007; Moore et al. 2007). Mnd2 contains a single Ime2 consensus phosphoacceptor site (at residue 269). These observations raise the possibility that Ime2 could regulate Smk1 by phosphorylating Mnd2. We tested whether Bn-PP1 was able to inhibit Smk1 activation in an mnd2-Δ ime2-as1 mutant. These experiments were carried out in a spo11-Δ genetic background to eliminate the meiosis-specific double strand breaks that can lead to checkpoint-mediated arrest in the mnd2-Δ background (Oelschlaegel et al. 2005; Penkner et al. 2005). Addition of Bn-PP1 reduced Smk1 phosphorylation in the ime2-as1 mnd2-Δ spo11-Δ cells (Figure 5B). These data demonstrate that Ime2 can promote the activation of Smk1 through an Mnd2-independent pathway.

DISCUSSION

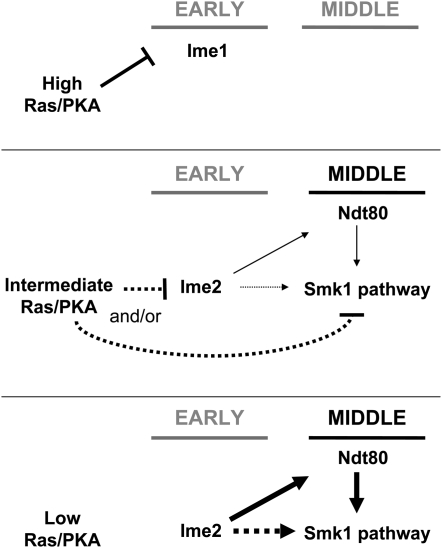

Ras was shown to control sporulation >25 years ago (Matsumoto et al. 1983; Kataoka et al. 1984). Since then, the Ras/cAMP pathway has been shown to control initiation of sporulation through the IME1 promoter (Sagee et al. 1998) and by regulating Ime1 once it has been translated (Rubin-Bejerano et al. 1996; Vidan and Mitchell 1997; Mallory et al. 2007). Much less is known about the Ras/cAMP pathway and late events in sporulation. In this study, we show that Ras/cAMP pathway mutations that decrease PKA activity can suppress the smk1-2 phenotype. We also show that glucose is required to observe this modification of the smk1-2 phenotype, consistent with the known role of glucose in Ras/cAMP signaling. The Ras/cAMP pathway mutations identified in this study can increase meiotic initiation (Table 3) and it is likely that this operates through IME1. However, it is unlikely that increased initiation is sufficient to cause the smk1-2 suppression phenotype since the SMK1 execution point is late in the program of sporulation, and since suppression of smk1-2 by cdc25-ΔC174, cyr1-ess, and mds3-ΔC1226 can be observed under conditions where the suppressed and nonsuppressed cells complete the meiotic divisions with comparable frequencies (Table 2). Moreover, Smk1 is not expressed until late in prophase, long after initiation has taken place. On the basis of these observations we propose that while high PKA activity can prevent initiation of meiosis through IME1 (Figure 6, top), intermediate PKA activity can inhibit the Smk1 pathway once meiotic initiation and progression through prophase have taken place (Figure 6, middle). A further reduction in Ras/cAMP signaling would eliminate the inhibitory interaction and permit activation of the Smk1 pathway and spore formation (Figure 6, bottom).

Figure 6.—

A model for signaling interactions that connect the Ras/cAMP pathway, Ime2, Smk1, and the transcriptional program of sporulation. The early (Ime1-inducible), and middle (Ndt80-inducible) phases of the transcriptional program of meiosis are indicated by horizontal lines. High levels of glucose lead to high PKA activity that inhibits IME1 and prevents meiotic initiation (top). The regulation of the Smk1 pathway by PKA occurs only in the presence of intermediate levels of glucose that are insufficient to prevent meiotic initiation (middle). In the intermediate state PKA is shown to negatively regulate Smk1 directly, through Ime2, or through both mechanisms as discussed in the text (dotted lines). Ime2 is shown to activate the Smk1 pathway through Ndt80-dependent and Ndt80-independent mechanisms. The Ndt80-independent mechanism is largely based on the relatively rapid kinetics of Smk1 inhibition by Bn-PP1 in the ime2-as1 strain and therefore should be considered provisional (dotted lines). Transition to a low PKA state (bottom) is predicted to relieve inhibition and increase Smk1 activity through the pathways indicated.

This study also demonstrates that Ime2 is a key regulator that promotes the phosphorylation of Smk1. How might Ime2 promote Smk1 activation? Ime2 positively regulates Ndt80 (Sopko et al. 2002; Benjamin et al. 2003) and Ndt80 activates the expression of Ama1 and Ssp2, which function in the Smk1 pathway (Chu et al. 1998; McDonald et al. 2005). Ndt80 also activates the expression of Cak1, the only known protein that is required for all detectable phosphorylation of Smk1 (Schaber et al. 2002) and Smk1 itself (Pierce et al. 1998). Thus, it is likely that Ime2 can promote activation of the Smk1 pathway through Ndt80. However, the kinetics of Smk1 inhibition when ime2-as1 cells are treated with Bn-PP1 is rapid (Figure 5). These observations suggest that a transcriptional mechanism may not be the only way that Ime2 promotes Smk1 activation (Figure 6). We found that although Mnd2 contains a predicted Ime2 phosphoacceptor motif, that Ime2 could affect Smk1 activation independent of Mnd2. The core APC and its mitotic substrate-bridging proteins Cdc20 and Cdh1 are significantly enriched in Ime2 phosphoacceptor consensus motifs, and Ime2 has been shown to regulate the APC (Bolte et al. 2002; Holt et al. 2007). Thus, it remains possible that Ime2 controls Smk1 activation through the APC by an Mnd2-independent mechanism.

IME2-ΔC241 is a dominant hyperactivating mutant, while smk1-2 is a loss-of-function hypomorph. Upstream hyperactivating mutations are expected to suppress the phenotype of a weakened signaling molecule. However, IME2-ΔC241 enhances the spore formation defect of smk1-2 (Figure 4). One model to explain these apparently contradictory results posits that IME2-ΔC241 hyperactivates multiple pathways that converge on spore formation (e.g. MI, MII, and steps in spore morphogenesis). According to this model, the catalytic output of Smk1-2 would be sufficient for sporulation when these steps are being executed at their normal rates in otherwise wild-type cells, but insufficient to meet the increased kinetic demands imposed by IME2-ΔC241. This model is consistent with the observation that even in an otherwise wild-type background, that many IME2-ΔC241 cells complete MI/MII but skip steps in the spore morphogenesis pathway and form asci containing only two or three spores (Sari et al. 2008).

The findings that the Smk1 pathway is activated by Ime2 and inhibited by the Ras/cAMP pathway raise the possibility that Ras/cAMP signaling controls Smk1 by inhibiting Ime2. Indeed, glucose can increase Ime2 degradation in sporulating cells through its C terminus (Purnapatre et al. 2005; Gray et al. 2008) and the ΔC241 deletion stabilizes Ime2 in mitotic cells (Sari et al. 2008). Gpa2 is a Gα-protein that transduces glucose signals from the Gpr1 receptor to adenylate cyclase and PKA (reviewed in Thevelein et al. 2008). Gpa2 also binds to Ime2's carboxy terminus and inhibits Ime2 catalytic activity (Donzeau and Bandlow 1999). Thus, the C terminus of Ime2 provides an appealing target of PKA that could explain the suppression of smk1-2 by Ras/cAMP pathway mutations. The observation that suppression of smk1-2 by cyr1-ess is not observed in an IME2-ΔC241 background is consistent with this hypothesis. However, as discussed above, a simple linear pathway model cannot explain the genetic interactions between smk1-2 and IME2-ΔC241. Thus, other explanations for these findings are possible and the inhibition of Ime2 by the Ras/cAMP pathway remains a provisional component of the model in Figure 6.

A major conclusion of this article is that the Ras/cAMP pathway inhibits spore formation in yeast. PKA inhibits exit from prophase in human oocytes and also inhibits spermatid development (reviewed in Burton and McKnight 2007). These observations raise the possibility that the inhibitory function of PKA in gametogenesis is evolutionarily conserved but that new extracellular ligand/PKA pathway connections evolved in multicellular organisms to control gamete formation in response to physiological and hormonal signals.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kirsten Benjamin, Lenore Neigeborne, Stefan Irniger, and James Broach for yeast strains and plasmids used in this study. The Bn-PP1 ATP analog was a generous gift from Kevin Shokat. We also thank Saul Honigberg for helpful advice and discussions. M.J.D. was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant P50-GM071508. M.E.S. was supported by NIH grant T32-DK07705. This work was supported by NIH grant GM061817 to E.W.

References

- Benjamin, K. R., C. Zhang, K. M. Shokat and I. Herskowitz, 2003. Control of landmark events in meiosis by the CDK Cdc28 and the meiosis-specific kinase Ime2. Genes Dev. 17 1524–1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benni, M. L., and L. Neigeborn, 1997. Identification of a new class of negative regulators affecting sporulation-specific gene expression in yeast. Genetics 147 1351–1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolte, M., P. Steigemann, G. H. Braus and S. Irniger, 2002. Inhibition of APC-mediated proteolysis by the meiosis-specific protein kinase Ime2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99 4385–4390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton, K. A., and G. S. McKnight, 2007. PKA, germ cells, and fertility. Physiology 22 40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu, S., J. DeRisi, M. Eisen, J. Mulholland, D. Botstein et al., 1998. The transcriptional program of sporulation in budding yeast. Science 282 699–705 (erratum: Science 282: 1421). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu, S., and I. Herskowitz, 1998. Gametogenesis in yeast is regulated by a transcriptional cascade dependent on Ndt80. Mol. Cell 1 685–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford, D. M., K. E. Stark, K. E. Gardner, S. Hoffmann-Benning and G. S. Brush, 2005. Mechanistic insight into the Cdc28-related protein kinase Ime2 through analysis of replication protein A phosphorylation. Cell Cycle 4 1826–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coluccio, A., E. Bogengruber, M. N. Conrad, M. E. Dresser, P. Briza et al., 2004. Morphogenetic pathway of spore wall assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot. Cell 3 1464–1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, K. F., M. J. Mallory, D. B. Egeland, M. Jarnik and R. Strich, 2000. Ama1p is a meiosis-specific regulator of the anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97 14548–14553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donzeau, M., and W. Bandlow, 1999. The yeast trimeric guanine nucleotide-binding protein alpha subunit, Gpa2p, controls the meiosis-specific kinase Ime2p activity in response to nutrients. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19 6110–6119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, R. E., and M. S. Esposito, 1974. Genetic recombination and commitment to meiosis in Saccharomyces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 71 3172–3176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedlander, G., D. Joseph-Strauss, M. Carmi, D. Zenvirth, G. Simchen et al., 2006. Modulation of the transcription regulatory program in yeast cells committed to sporulation. Genome Biol. 7 R20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Z., K. A. Larson, R. K. Chitta, S. A. Parker, B. E. Turk et al., 2006. Identification of Yin-Yang regulators and a phosphorylation consensus for male germ cell-associated kinase (MAK)-related kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26 8639–8654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Z., M. J. Schroeder, J. Shabanowitz, P. Kaldis, K. Togawa et al., 2005. Activation of a nuclear Cdc2-related kinase within a mitogen-activated protein kinase-like TDY motif by autophosphorylation and cyclin-dependent protein kinase-activating kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25 6047–6064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray, M., S. Piccirillo, K. Purnapatre, B. L. Schneider and S. M. Honigberg, 2008. Glucose induction pathway regulates meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae in part by controlling turnover of Ime2p meiotic kinase. FEMS Yeast Res. 8 676–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresham, D., D. M. Ruderfer, S. C. Pratt, J. Schacherer, M. J. Dunham et al., 2006. Genome-wide detection of polymorphisms at nucleotide resolution with a single DNA microarray. Science 311 1932–1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt, L. J., J. E. Hutti, L. C. Cantley and D. O. Morgan, 2007. Evolution of Ime2 phosphorylation sites on Cdk1 substrates provides a mechanism to limit the effects of the phosphatase Cdc14 in meiosis. Mol. Cell 25 689–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honigberg, S. M., 2004. Ime2p and Cdc28p: co-pilots driving meiotic development. J. Cell. Biochem. 92 1025–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honigberg, S. M., C. Conicella and R. E. Espositio, 1992. Commitment to meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: involvement of the SPO14 gene. Genetics 130 703–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honigberg, S. M., and R. E. Esposito, 1994. Reversal of cell determination in yeast meiosis: postcommitment arrest allows return to mitotic growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91 6559–6563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honigberg, S. M., and K. Purnapatre, 2003. Signal pathway integration in the switch from the mitotic cell cycle to meiosis in yeast. J. Cell Sci. 116 2137–2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinno, A., K. Tanaka, H. Matsushime, T. Haneji and M. Shibuya, 1993. Testis-specific mak protein kinase is expressed specifically in the meiotic phase in spermatogenesis and is associated with a 210-kilodalton cellular phosphoprotein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13 4146–4156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassir, Y., N. Adir, E. Boger-Nadjar, N. G. Raviv, I. Rubin-Bejerano et al., 2003. Transcriptional regulation of meiosis in budding yeast. Int. Rev. Cytol. 224 111–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka, T., S. Powers, C. McGill, O. Fasano, J. Strathern et al., 1984. Genetic analysis of yeast RAS1 and RAS2 genes. Cell 37 437–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koji, T., A. Jinno, H. Matsushime, M. Shibuya and P. K. Nakane, 1992. In situ localization of male germ cell-associated kinase (mak) mRNA in adult mouse testis: specific expression in germ cells at stages around meiotic cell division. Cell Biochem. Funct. 10 273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kominami, K., Y. Sakata, M. Sakai and I. Yamashita, 1993. Protein kinase activity associated with the IME2 gene product, a meiotic inducer in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 57 1731–1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krisak, L., R. Strich, R. S. Winters, J. P. Hall, M. J. Mallory et al., 1994. SMK1, a developmentally regulated MAP kinase, is required for spore wall assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 8 2151–2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, C. W., 2002. Classical mutagenesis techniques. Methods Enzymol. 350 189–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R. H., and S. M. Honigberg, 1996. Nutritional regulation of late meiotic events in Saccharomyces cerevisiae through a pathway distinct from initiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16 3222–3232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J., S. Agarwal and G. S. Roeder, 2007. SSP2 and OSW1, two sporulation-specific genes involved in spore morphogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 175 143–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallory, M. J., K. F. Cooper and R. Strich, 2007. Meiosis-specific destruction of the Ume6p repressor by the Cdc20-directed APC/C. Mol. Cell 27 951–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, K., I. Uno and T. Ishikawa, 1983. Initiation of meiosis in yeast mutants defective in adenylate cyclase and cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. Cell 32 417–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushime, H., A. Jinno, N. Takagi and M. Shibuya, 1990. A novel mammalian protein kinase gene (mak) is highly expressed in testicular germ cells at and after meiosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10 2261–2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, C. M., K. F. Cooper and E. Winter, 2005. The Ama1-directed APC/C ubiquitin ligase regulates the Smk1 MAPK during meiosis in yeast. Genetics. 171 901–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, M., M. E. Shin, A. Bruning, K. Schindler, A. Vershon et al., 2007. Arg-Pro-X-Ser/Thr is a consensus phosphoacceptor sequence for the meiosis-specific Ime2 protein kinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry 46 271–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraj, R., and U. Banerjee, 2004. The little R cell that could. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 48 755–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelschlaegel, T., M. Schwickart, J. Matos, A. Bogdanova, A. Camasses et al., 2005. The yeast APC/C subunit Mnd2 prevents premature sister chromatid separation triggered by the meiosis-specific APC/C-Ama1. Cell 120 773–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penkner, A. M., S. Prinz, S. Ferscha and F. Klein, 2005. Mnd2, an essential antagonist of the anaphase-promoting complex during meiotic prophase. Cell 120 789–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, M., M. Wagner, J. Xie, V. Gailus-Durner, J. Six et al., 1998. Transcriptional regulation of the SMK1 mitogen-activated protein kinase gene during meiotic development in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18 5970–5980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primig, M., R. Williams, E. Winzeler, G. Tevzadze, A. Conway et al., 2000. The core meiotic transcriptome in budding yeasts. Nat. Genet. 26 415–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purnapatre, K., M. Gray, S. Piccirillo and S. M. Honigberg, 2005. Glucose inhibits meiotic DNA replication through SCFGrr1p-dependent destruction of Ime2p kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25 440–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin-Bejerano, I., S. Mandel, K. Robzyk and Y. Kassir, 1996. Induction of meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae depends on conversion of the transcriptional represssor Ume6 to a positive regulator by its regulated association with the transcriptional activator Ime1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16 2518–2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin-Bejerano, I., S. Sagee, O. Friedman, L. Pnueli and Y. Kassir, 2004. The in vivo activity of Ime1, the key transcriptional activator of meiosis-specific genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is inhibited by the cyclic AMP/protein kinase A signal pathway through the glycogen synthase kinase 3-beta homolog Rim11. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24 6967–6979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagee, S., A. Sherman, G. Shenhar, K. Robzyk, N. Ben-Doy et al., 1998. Multiple and distinct activation and repression sequences mediate the regulated transcription of IME1, a transcriptional activator of meiosis- specific genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18 1985–1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sari, F., M. Heinrich, W. Meyer, G. H. Braus and S. Irniger, 2008. The C-terminal region of the meiosis-specific protein kinase Ime2 mediates protein instability and is required for normal spore formation in budding yeast. J. Mol. Biol. 378 31–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, P. K., M. A. Florczyk, K. A. McDonough and D. K. Nag, 2002. SSP2, a sporulation-specific gene necessary for outer spore wall assembly in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Genet. Genomics 267 348–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaber, M., A. Lindgren, K. Schindler, D. Bungard, P. Kaldis et al., 2002. CAK1 promotes meiosis and spore formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae in a CDC28-independent fashion. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22 57–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler, K., and E. Winter, 2006. Phosphorylation of Ime2 regulates meiotic progression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 281 18307–18316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler, K., K. R. Benjamin, A. Martin, A. Boglioli, I. Herskowitz et al., 2003. The Cdk-activating kinase Cak1p promotes meiotic S phase through Ime2p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 8718–8728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedgwick, C., M. Rawluk, J. Decesare, S. A. Raithatha, J. Wohlschlegel et al., 2006. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ime2 phosphorylates Sic1 at multiple PXS/T sites but is insufficient to trigger Sic1 degradation. Biochem. J. 399 151–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, F., and H. Roman, 1963. Evidence for two types of allelic recombination in yeast. Genetics 48 255–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sia, R. A., and A. P. Mitchell, 1995. Stimulation of later functions of the yeast meiotic protein kinase Ime2p by the IDS2 gene product. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15 5279–5287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simchen, G., R. Pinon and Y. Salts, 1972. Sporulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: premeiotic DNA synthesis, readiness and commitment. Exp. Cell Res. 75 207–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sopko, R., S. Raithatha and D. Stuart, 2002. Phosphorylation and maximal activity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae meiosis-specific transcription factor Ndt80 is dependent on Ime2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22 7024–7040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thevelein, J. M., B. M. Bonini, D. Castermans, S. Haesendonckx, J. Kriel et al., 2008. Novel mechanisms in nutrient activation of the yeast protein kinase A pathway. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 55 75–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidan, S., and A. P. Mitchell, 1997. Stimulation of yeast meiotic gene expression by the glucose-repressible protein kinase Rim15p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17 2688–2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, M., P. Briza, M. Pierce and E. Winter, 1999. Distinct steps in yeast spore morphogenesis require distinct SMK1 MAP kinase thresholds. Genetics 151 1327–1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, M., M. Pierce and E. Winter, 1997. The CDK-activating kinase CAK1 can dosage suppress sporulation defects of smk1 MAP kinase mutants and is required for spore wall morphogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 16 1305–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaman, S., S. I. Lippman, X. Zhao and J. R. Broach, 2008. How Saccharomyces responds to nutrients. Annu. Rev. Genet. 42 27–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenvirth, D., J. Loidl, S. Klein, A. Arbel, R. Shemesh et al., 1997. Switching yeast from meiosis to mitosis: double-strand break repair, recombination and synaptonemal complex. Genes Cells 2 487–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]