Abstract

Introduction

Of recent clinical interest have been two related human G-protein coupled receptors: formylpeptide receptor (FPR), linked to anti-bacterial inflammation and malignant glioma cell metastasis; and formylpeptide receptor like-1 (FPRL1), linked to chronic inflammation in systemic amyloidosis, Alzheimer’s disease and prion diseases. In association with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Molecular Library Screening Network, we implemented a flow cytometry based high throughput screening (HTS) approach for identifying selective small molecule FPR and FPRL1 ligands.

Methods

The screening assay measured the ability of test compounds to competitively displace a high-affinity, fluorescein-labeled peptide ligand from FPR, FPRL1 or both. U937 cells expressing FPR and RBL cells expressing FPRL1 were tested together in a “duplex” format. The U937 cells were color-coded with red fluorescent dye allowing their distinction during analysis. Compounds, cells and fluorescent ligand were sequentially combined (no-wash) in 15 μL assay volumes in 384-well plates. Throughput averaged ∼11 min per plate to analyze ∼4000 cells (∼2000/receptor) in a 2 μL aspirate from each well.

Results/Conclusions

In primary single concentration HTS of 24,304 NIH Small Molecule Repository compounds, 253 resulted in inhibition >30% (181 for FPR, 72 for FPRL1) of which 40 had selective binding inhibition constants (Ki) ≤ 4 μM (34 for FPR and 6 for FPRL1). An additional 1,446 candidate compounds were selected by structure-activity -relationship analysis of the hits and screened to identify novel ligands for FPR (3570-0208, Ki= 95 ± 10 nM) and FPRL1 (BB-V-115, Ki= 270 ± 51 nM). Each was a selective antagonist in calcium response assays and the most potent small molecule antagonist reported for its respective receptor to date. The duplex assay format reduced assay time, minimized reagent requirements, and provided selectivity information at every screening stage, thus proving to be an efficient means to screen for selective receptor ligand probes.

Introduction

The G-protein coupled formylpeptide receptor (FPR) was one of the originating members of the chemoattractant receptor superfamily (1,2). N-formylated peptides such as fMLF are high affinity FPR ligands that trigger a variety of biologic activities in myeloid cells, including chemokinesis, chemotaxis, cytokine production and superoxide generation (3-7). Since such peptides are derived from bacterial or mitochondrial proteins (8-11), it has been proposed that a primary FPR function is to promote trafficking of phagocytic myeloid cells to sites of infection and tissue damage where they exert anti-bacterial effector functions and clear cell debris. In support of this hypothesis, mice lacking a known murine FPR variant were more susceptible to bacterial infections (12). The glucocorticoid-regulated protein, annexin I (lipocortin I), was recently identified as another protein of host origin that is a specific agonist for human FPR (13). FPR have also been proposed as prospective targets for therapeutic intervention against malignant gliomas (14,15).

FPR-like 1 (FPRL1) is the product of one of a family of additional human genes that have been reported to encode FPR variants (16-19). FPRL1 shares 69% identity at the amino acid level with FPR and is, like FPR, a seven-transmembrane, G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) (3,20). While N-formyl peptides such as fMLF only weakly activate FPRL1 (18), a number of host-derived FPRL1 agonists of pathophysiological provenance have been identified. These include amyloidogenic proteins, serum amyloid A (6,21) and A β42 (22), and a prion protein fragment, PrP1206-26 (23), which are involved in chronic inflammation-associated systemic amyloidosis (24), Alzheimer’s disease (25,26), and prion diseases (23,27), respectively. Since infiltration of activated mononuclear phagocytes is a common feature, cells responding to FPRL1 ligands may contribute to the inflammatory pathology observed in the diseased tissues (7,28,29). Other reported FPRL1 agonists include an enzymatic cleavage fragment of the neutrophil granule derived cathelicidin (30), a NADH dehydrogenase subunit peptide fragment (31) and subdomains of HIV-1 envelope proteins (32-34). Interestingly, FPRL1 agonists were recently reported to suppress growth of transplanted mouse liver tumor cells by virtue of elevating leukocyte expression of endogenous necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) (35).

FPR is expressed by neutrophils, monocytes, hepatocytes, immature dendritic cells, astrocytes, microglial cells, and the tunica media of coronary arteries (36-39). FPRL1 is expressed by an even greater variety of cell types including phagocytic leukocytes, hepatocytes, epithelial cells, T lymphocytes, neuroblastoma cells, astrocytoma cells, and microvascular endothelial cells (18,20,28,40,41). In addition, a recent study has documented expression of both FPR and FPRL1 by normal human lung and skin fibroblasts (34). The diverse tissue expression of these receptors suggests the possibility of as yet unappreciated complexity in the innate immune response and perhaps other unidentified functions for the receptor family.

High affinity small molecule ligands for FPR and FPRL1 represent probes with which to dissect the physiological roles of these receptors in vivo as well as in vitro. We previously reported the use of a fluorescent ligand competition assay and high-throughput flow cytometry to identify a series of novel small molecule ligands for FPR that acted as antagonists (42). The most potent had a ligand binding inhibition constant (Ki) of ∼2 μM. To date, whereas a number of small molecule agonists for FPRL1 have been identified (43,44), there has only been one recent report of an antagonist, designated C7, that exhibited an IC50 of 6.7μM (45).

The present study was undertaken to identify small molecule FPR and FPRL1 antagonists with improved potency that might be of greater effectiveness for biological investigations and possible therapeutic applications. Of particular interest was development of a screening approach whereby both receptors could be interrogated simultaneously so as to improve screening efficiency and enable receptor binding specificity as an integral feature reported by the screen. Here we describe a high-throughput flow cytometry assay that uses a novel fluorescent peptide ligand that binds both FPR and FPRL1 with low nM affinity. Cells expressing human FPR or FPRL1 are fluorescently color-coded to allow their discrimination in flow cytometric analysis of fluorescent ligand competition results. The assay is homogeneous, requiring no intermediate wash steps during the assay plate set up. It also requires only ∼2 μl to be aspirated from each well of a 384-well assay plate for the analysis, a 15 μl total assay volume in each well, and ∼11 min for flow cytometry processing of each 384-well plate. After screening of more than 25,000 small molecules, selective antagonists were identified for each receptor that exhibited greater that 10-fold improved potency relative to previously reported non-peptide ligands.

Methods

Reagents

Tissue culture medium (TCM) consisted of RPMI-1640 medium (Mediatech) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (US Biotechnologies), 2mM L-glutamine-10U/ml penicillin-10 μg/ml streptomycin (Mediatech), 10 mM HEPES (Mediatech), and 4 μg/ml CIPRO (Bayer Pharmaceuticals). Peptide dilution buffer (PDB) consisted of 110 mM NaCl, 30 mM HEPES, 10 mM KCl, 1mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucose, and 0.1% bovine serum albumin, all components from SIGMA. N-formyl-methionine-leucine-phenylalanine-phenylalanine peptide (fMLFF) was obtained from Sigma. Tryptophan-lysine-tyrosine-methionine-valine-D-methionine (WPep) was obtained from Bachem.

A fluorescein label was conjugated to the lysine residue of the WPep peptide to produce a fluorescent ligand (WPep-FITC) that bound both FPR and FPRL-1 with high affinity (Bachem, special synthesis). Dissociation constants (Kd) for binding of WPep-FITC to FPR and FPRL1 were determined to be 1.2 nM and 1.8 nM, respectively. WPep-FITC was used as the fluorescent ligand in the duplex FPR-FPRL1 assay to determine compound activity for both receptors. A detailed quantitative characterization of WPep-FITC binding to FPR and FPRL1 has been reported separately (Strouse et al, Fluorescent Cross-Reactive FPR/FPRL1 Hexapeptide Ligand, submitted for publication).

Cells

RBL-2H3 cells expressing human FPRL1 (RBL/FPRL1) were grown as adherent cell cultures in TCM supplemented with 2.5 μg/ml Amphotericin B (CellGro). U937 cells expressing human FPR were grown as 100 ml suspensions in TCM.

RBL/FPRL1 cells were detached with 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA (37° C, 2-5 min), suspended in TCM, centrifuged 10 min at 450×g and resuspended at 4 × 106 / ml in PDB. U937/FPR cells were centrifuged 10 min at 450×g, resuspended in PDB at 5 × 105 cells/ml and color-coded by incubation 15 min at 37°C with Fura RedTM, AM (InVitrogen) at a final concentration of 6 μM. After two subsequent centrifugation washes in PDB to remove unincorporated dye, the cell pellet was resuspended by addition of the RBL/FPRL1 cell suspension to achieve a final U937/FPR cell concentration of 4 × 106/ ml, equal to that of the RBL/FPRL1 cells. The cell mixture was stored on ice until used in the assay.

Single concentration HTS assays

The single concentration HTS assay used flow cytometry to measure test compound competition with a high-affinity fluorescent ligand for binding to human FPR. The assay was performed in a “duplex” format in which U937/FPR cells were tested together with RBL/FPRL1 cells. The FPR-expressing cells were stained with a red-fluorescent dye, FuraRed™ allowing them to be distinguished from the FPRL1-expressing cells during flow cytometric analysis.

Assays were performed in polystyrene 384-well plates with small volume wells (Greiner #784101). Additions to wells were in sequence as follows: 1) test compounds and control reagents (5 μL/well); 2) the combined suspension of U937/FPR and RBL/FPRL1 cells (5 μL/well); 3) (after 30 min, 4° C incubation) WPep-FITC (5 μL/well). After an additional 45 min, 4° C incubation, plates were immediately analyzed using flow cytometry. The assay response range was defined by replicate control wells containing unlabeled receptor-blocking peptide (positive control) or buffer (negative control). fMLFF was used as the FPR-blocking peptide, unlabeled WPep as the FPRL1-blocking peptide. Final concentrations of test compounds and WPep-FITC were 6.7 μM and 5 nM, respectively.

The assay was homogeneous in that cells, compounds and fluorescent peptide were added in sequence and the wells subsequently analyzed without intervening wash steps. The HyperCyt™ high throughput flow cytometry platform (46,47) was used to sequentially sample cells from wells of 384-well microplates (2 μL/sample) for presentation to a CyAn flow cytometer (Beckman-Coulter) at a rate of ∼40 samples/min. Fluorescence was excited at 488 nm and detected with 530/40 and 680/30 optical bandpass filters for WPep-FITC and FuraRed™, respectively. The resulting time-resolved data files were analyzed with IDLeQuery software to determine compound activity in each well. The HyperCyt platform and associated analysis software are commercially available (IntelliCyt).

Test compound inhibition of fluorescent peptide binding was calculated as

in which MFI_Test, MFI_PC and MFI_NC represent the median fluorescence intensity of cells in wells containing test compound, the average MFI of cells in positive control wells and the average MFI of cells in negative control wells, respectively.

Dose response assays

Dose response assays were performed essentially as described for single concentration assays except that test compounds were hit-picked at a 10 mM concentration (unless otherwise indicated) in DMSO and serially diluted 1:3 eight times for a total of nine different test compound concentrations. Final compound dilution factors in the assay ranged from 1:984,150 to 1:150. For a starting concentration of 10 mM this corresponded to a concentration range of 10.2 nM to 66.7 μM.

In an individual dose response experiment, each compound was tested in duplicate to result in 18 data points. The resulting ligand competition curves were fitted by Prism® software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA) using nonlinear least-squares regression in a sigmoidal dose response model with variable slope, also known as the four parameter logistic equation. Two parameters, the top and bottom of the fitted curves, were fixed at 100 and 0, the expected upper and lower boundaries of normalized data. Curve fit statistics were used to determine the concentration of added test compound competitor that inhibited fluorescent ligand binding by 50 percent (IC50, μM), the low and high boundaries of the 95% confidence interval of the IC50 estimate, the Hill Slope, and the correlation coefficient (r2) indicative of goodness-of-fit.

FPR expression ranged from 100,000 to 200,000 receptors per cell in different assays as determined by comparison to standard curves generated with Fluorescein Reference Standard Microbeads (Bangs Laboratories, Fishers, IN). This corresponded to total FPR concentrations of 0.6 to 1.2 nM. To account for effects of possible ligand depletion at the higher receptor concentrations, Ki were calculated from IC50 estimates by the method of Munson and Rodbard (48):

in which y0 is the initial bound-to-free concentration ratio for the fluorescent ligand, p* is the added concentration of fluorescent ligand and Kd is the dissociation constant of the fluorescent ligand.

Intracellular calcium response antagonist assay

Cells were resuspended in warm tissue culture medium (107 cells in 10 mL) containing 200 nM Fluo4 acetoxymethyl ester (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and incubated at 37° C for 30 minutes, with mixing every 10 minutes. After incubation, Fluo4-loaded cells were washed twice by centrifugation, resuspended in complete HHB medium (110 mM NaCl, 30 mM HEPES, 10 mM KCL, 1mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucose, and 0.1% (v/v) human serum albumin, and 1.5 mM CaCl2), allowed to equilibrate at 37° C for 10 minutes, and stored on ice.

To assess the ability of test compounds to block receptor-induced intracellular calcium responses, 100 microL of Fluo-4 labeled cell suspension plus 1 microL of test compound was added to wells of a Nunc 96-well plate (Nunclon surface, Nuncbrand, Denmark) and allowed to warm at 37 degrees C for 5-10 minutes. Final test compound concentration was 100 μM (1% DMSO). Wells were then sequentially analyzed in a PerkinElmer Wallac 1420 Multilabel Counter used in bottom counting mode with excitation at 485 nm and emission detected at 535 nm. For each well there was an initial 10 s reading at 1 s intervals to establish background fluorescence intensity, then 100 μL of 10-9 M WKYMVm was dispensed into the well, the plate was shaken for 5 s and readings were made for an additional 30 s thereafter at 1 s intervals.

The fluorescence intensity (FI) values were summed and averaged for the 10 s prior to stimulus addition (Avg_FI_Base). The FI values were summed over the 30 measurements made during the last 30 s post-addition to determine the area under the response curve post-addition (AUC_Post). Avg_FI_Base was multiplied by 30 to obtain a baseline area under the curve estimate (AUC_Base). The response to stimulus was calculated as the difference

AUC_Response was calculated for 2 conditions: 1) 1% DMSO, no test compound present and WKYMVm added as stimulus (Rmax), and 2) test compound present (1% DMSO) and WKYMVm added as stimulus (Rtest).

Test compound inhibition of the calcium response was calculated as:

Results

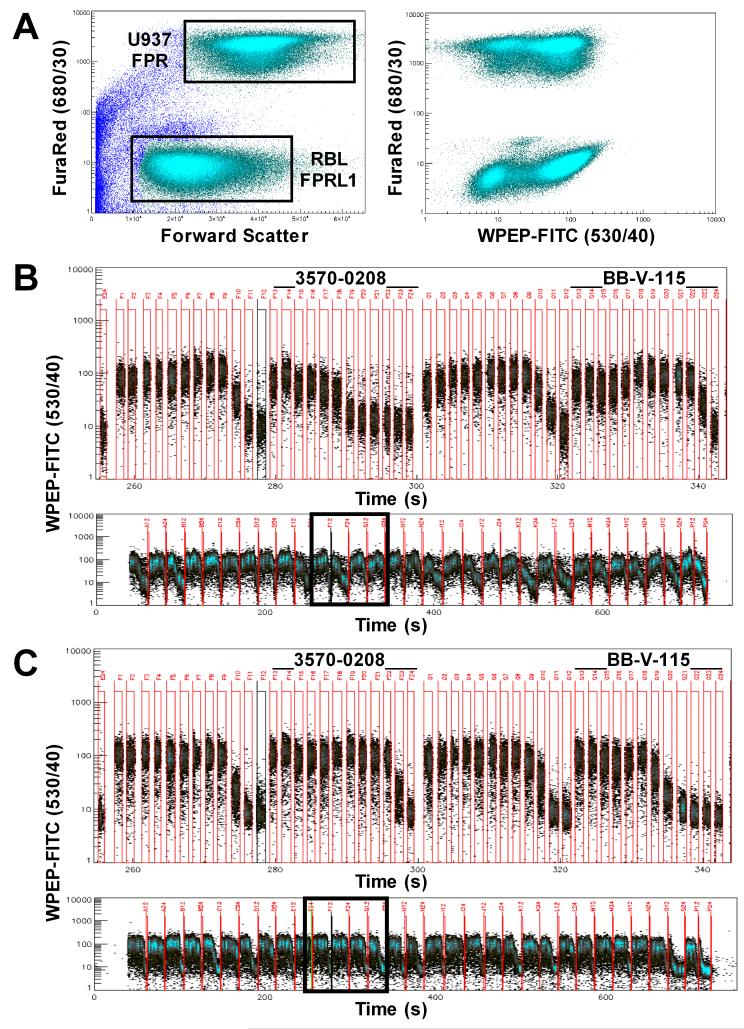

A screening assay was developed to assess the ability of test compounds to competitively displace fluorescent peptide ligand from FPR and FPRL1. Though similar in principle to previously published studies of FPR (42,49), this assay was a duplex analysis in which both receptors were evaluated in parallel. Enabling this approach was a novel fluorescent probe peptide that bound both receptors with a comparable low nM affinity (WPEP-FITC, manuscript submitted for publication). U937/FPR cells were color-coded with a red fluorescent label so that they could be distinguished from the RBL/FPRL1 cells and separately gated (Fig. 1, A, left panel), allowing simultaneous analysis of binding of WPEP-FITC to the respective receptors. Samples of ∼2 μl in volume were aspirated from wells of a 384-well plate and delivered to the flow cytometer by a peristaltic pump. Each sample was separated from the other by air bubbles in the delivery line. As illustrated in a representative dose-response experiment (Fig. 1, B and C), cells from individual wells were temporally resolved as periodic bursts of events interrupted by event-free intervals, the former corresponding to the passage of samples and the latter to the passage of air bubbles through the point of analysis. The independence of FPR and FPRL1 measurements was illustrated by the differences in dose response profiles of individual test compounds for each receptor (Fig 1, B and C, top panels).

Figure 1.

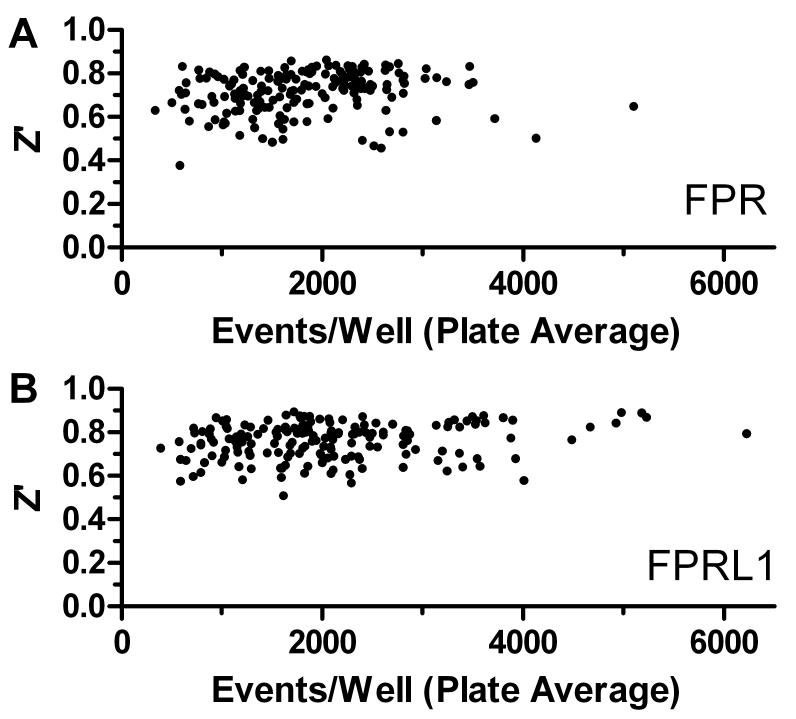

Initially, 24,304 compounds from the NIH Molecular Libraries Small Molecule Repository (MLSMR) were screened in the duplex competition assay at a single concentration of 6.7 μM. Over the course of screening 176 plates the Z’ value averaged 0.715 ± 0.097 for the FPR assay component and 0.759 ± 0.082 for the FPRL1 assay component. Interestingly, comparable Z’ values were observed when the average number of cells sampled from individual wells ranged from less than 1,000 to as high as 5,000 (Fig. 2). This indicated that high quality assay results could be obtained with analysis of relatively small numbers of cells from a sample.

Figure 2.

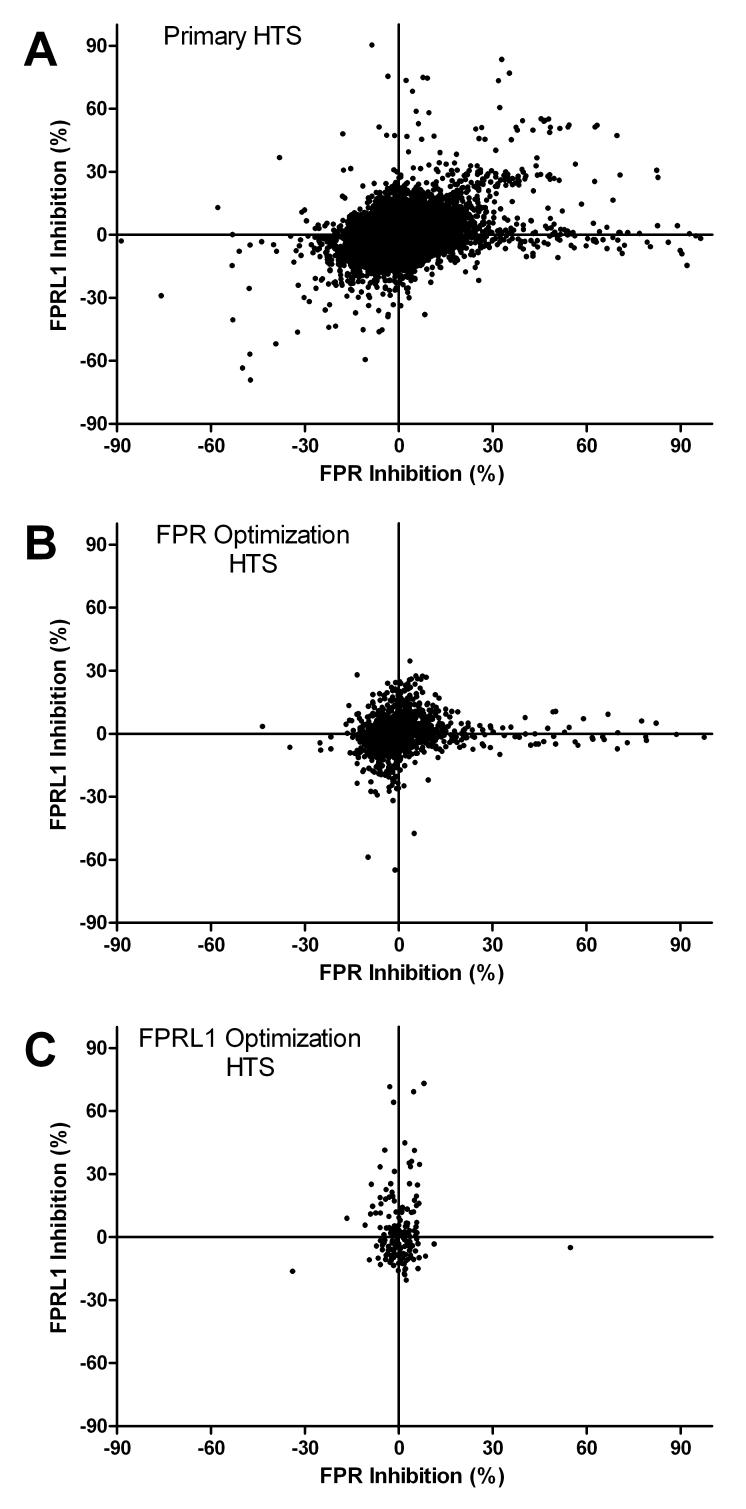

The distribution of compound activities for FPR and FPRL1 in the primary HTS assay is illustrated in Fig. 3A. There were 181 (0.74%) and 72 (0.3%) compounds that exceeded the hit selection threshold of 30% inhibition of fluorescent ligand binding for FPR and FPRL1, respectively. Of these, there were 26 compounds (0.11%) that were apparently crossreactive with both receptors. In follow up dose response studies, 34 of the compounds with FPR activity and 6 with FPRL1 activity were determined to have inhibition constants (Ki) of 4 μM or less for their respective receptors. The most potent compounds had Ki of 0.67 and 1.8 μM for FPR and FPRL1, respectively. There were none with Ki ≤ 4 μM for both receptors.

Figure 3.

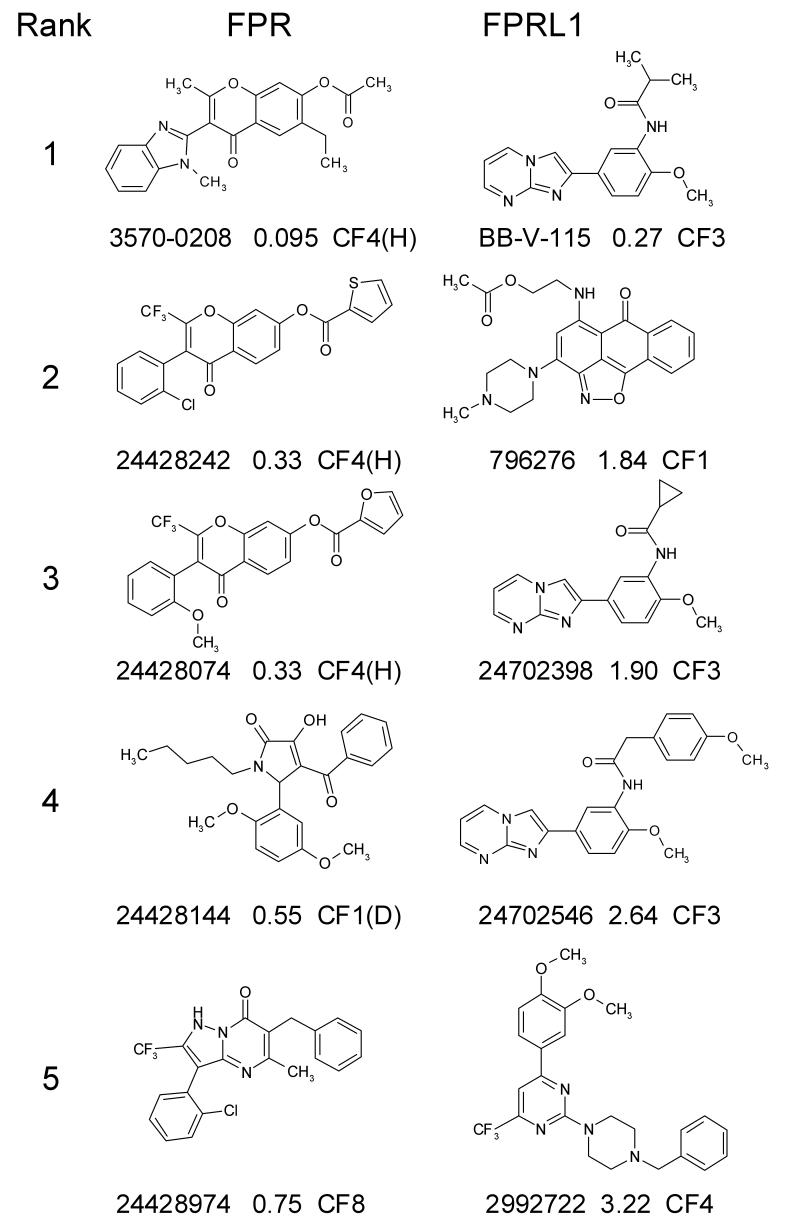

A second round of analysis and screening was performed in an attempt to identify compounds with greater potency. Active compounds from the first round were first evaluated to identify common chemical scaffolds or chemotype families that correlated with activity. Two-dimensional substructure searches and other computational screening techniques were then used to select compounds with similar characteristics from a 700,000 compound subset of the ChemDiv collection. A set of 1,276 compounds was selected for optimization of FPR activity and separate set of 170 compounds was selected for FPRL1 activity optimization. When each set was subsequently screened in single concentration HTS assays there was clear confirmation of the hypothesized chemotype family structure activity relationships. In each optimization screen all but one of the active compounds showed selective activity for the receptor that was targeted for optimization (Fig. 3B and 3C, respectively). Moreover, as compared to results in the primary round of screening, the percentage of tested compounds with Ki < 4μM increased 10.8-fold in the FPR optimization screen (from 0.13% to 1.4%) and 116-fold in the FPRL1 optimization screen (from 0.025% to 2.9%) (Table 1). The Ki s of the top five most potent compounds ranged from 0.095 to 0.75 μM for FPR and from 0.27 to 3.22 μM for FPRL1 (Fig. 4). Four of the top-ranked compounds in the FPR series were from chemotype families (CF) 1 and 4, respectively corresponding to families D and H identified in a previous FPR screening campaign (42). The fifth ranked FPR hit compound represented a novel family, designated CF8. Three novel CF were identified among the top five compounds of the FPRL1 hit series (Fig. 4, CF1, 3 and 4). The most potent compounds identified were 3570-0208 (PubChem SID 24428139) for FPR and BB-V-115 (PubChem SID 24702504) for FPRL1 (Fig. 4, rank 1). Both were resynthesized and retested to confirm activity.

Table 1.

Compound activity summary

| FPR | FPRL1 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening Round |

# Screened |

Inhib > 30% | Ki ≤ 4 μM | Inhib > 30% | Ki ≤ 4 μM | ||||

| # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | ||

| Primary | 24,304 | 181 | 0.13 | 34 | 0.13 | 72 | 0.30 | 6 | 0.025 |

| FPR Optimization |

1,276 | 38 | 3.0 | 18 | 1.4 | 1 | 0.08 | 0 | 0 |

| FPRL1 Optimization |

170 | 1 | 0.59 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 7.6 | 5 | 2.9 |

Figure 4.

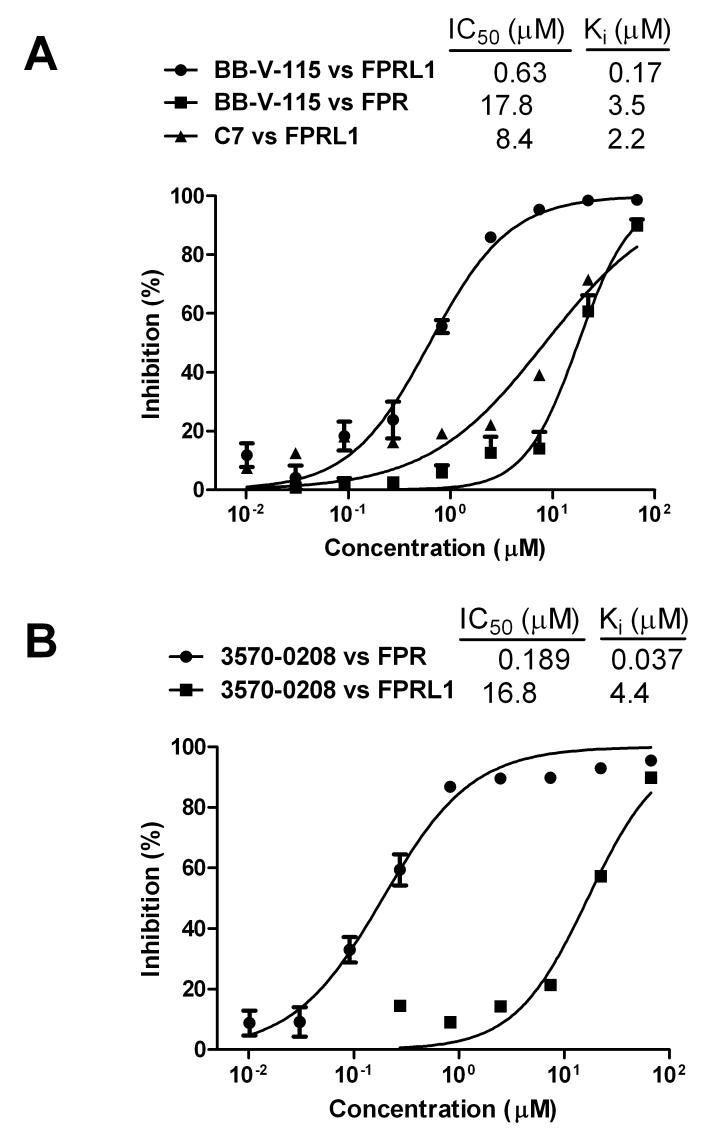

When evaluated in 17 separate duplex competition assays over a period of several weeks, the Ki of BB-V-115 for FPRL1 averaged 0.27 ± 0.051 μM (mean ± SEM) and was beyond the upper measurement limit of the assay for FPR (13.3 μM) in 14 of the 17 assays. In an experiment representative of the 3 assays in which FPR activity was in a measurable range, BB-V-115 affinity for FPRL1 was ∼20-fold greater than for FPR (Fig. 5A, Ki = 0.17 and 3.5 μM, respectively). We also synthesized C7, the recently reported non-peptide antagonist for FPRL1 (45), and confirmed its ability to competitively displace WPep-FITC from FPRL1. The observed affinity was similar to what was previously reported and ∼10-fold less than that of BB-V-115 when compared in the same experiment (Fig 5A, Ki = 2.2 μM).

Figure 5.

In 20 separate duplex competition assays, the Ki of 3570-0208 averaged 0.095 ± 0.010 μM for FPR and was beyond the upper measurement limit of the assay for FPRL1 (17.8 μM) in 18 of the 20 assays. Representative of the 2 assays in which there was measurable FPRL1 activity, the affinity of 3570-0208 for FPR exceeded that for FPRL1 by more than 100-fold (Fig. 5B, Ki= 0.037 and 4.4 μM, respectively).

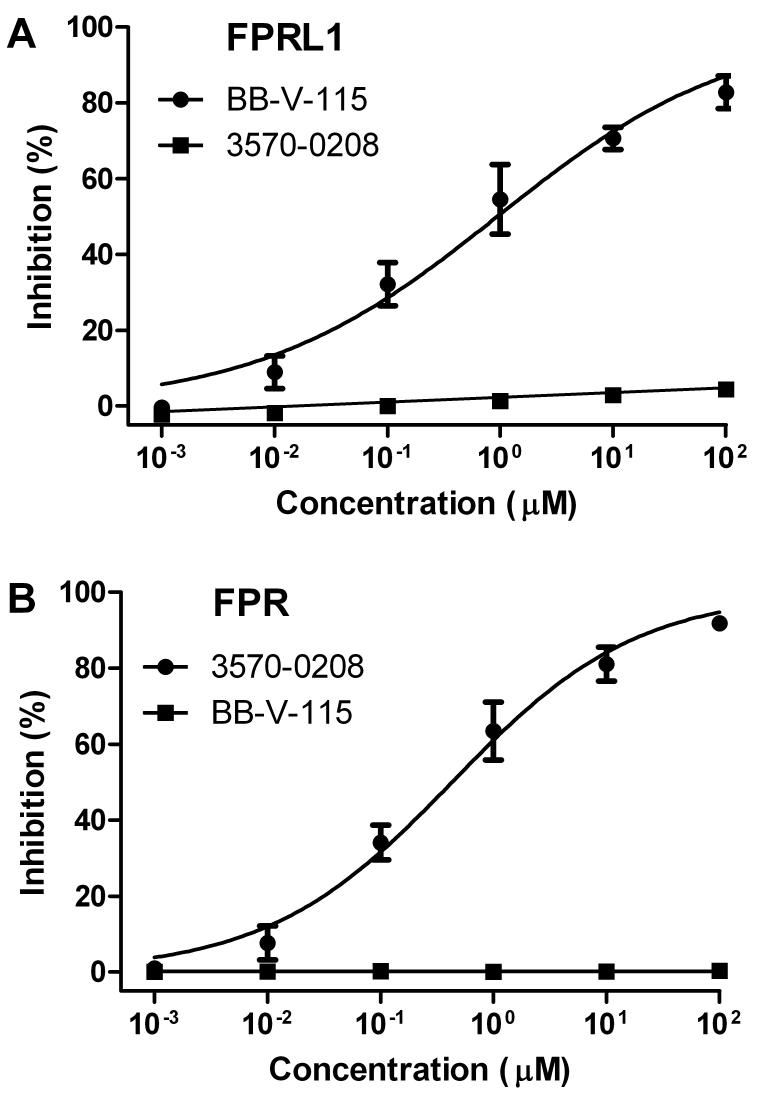

Intracellular calcium response assays were performed to determine the ability of the two compounds to block responses induced by high affinity peptide agonists for their respective target receptors. BB-V-115 was confirmed to be an antagonist for intracellular calcium responses elicited in RBL/FPRL1 cells by WKYMVm (Fig. 6A). Likewise, 3570-0208 was an antagonist for responses elicited in U937/FPR cells by fMLFF (Fig. 6B). At concentrations of up to 100 μM, neither compound exhibited measurable antagonist activity for the off-target receptor (Fig 6).

Figure 6.

Discussion

There is a significant unmet need for new small molecule chemical probes to functionally dissect and modulate cellular processes and pathways. The present studies were undertaken to develop selective probes with which to advance the understanding of two members of the FPR family of receptors, FPR and FPRL1. These receptors are expressed in a diversity of tissues and have been implicated in a number of important pathophysiological processes. A high throughput flow cytometry screening campaign involving analysis of more than 25,000 small molecules was undertaken to identify selective ligands for each receptor.

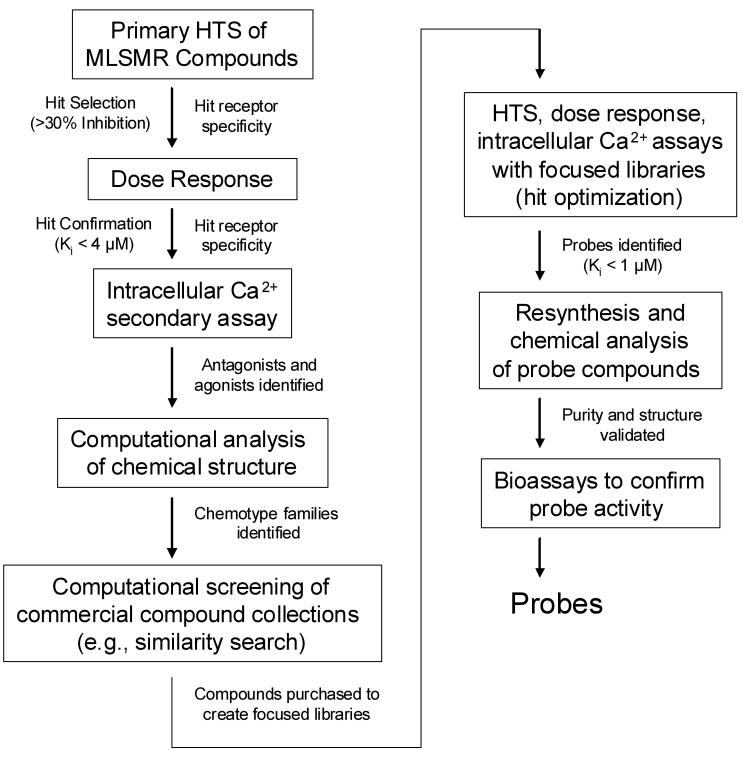

The screening strategy involved two sequential rounds of HTS, dose-response and intracellular Ca2+ response analysis (Fig. 7). The first round used a relatively large and structurally diverse collection of compounds from the MLSMR. This was followed by a hit optimization round in which much smaller compound collections were created and screened on the basis of computational analysis of active structures identified in the first round (Fig. 7). This strategy led to identification of novel selective antagonist probes for each receptor. Both probes exhibited greater that 10-fold improved potency relative to previously reported non-peptide antagonists for these receptors. A listing of small molecules reported as the most potent antagonists and agonists for the two receptors in this and previous studies is illustrated in Table 2. During the course of the present screening campaign we also identified a small number of FPR and FPRL1 agonists (data not shown), but none of appreciable potency in comparison to previously reported small molecule agonists.

Figure 7.

Table 2.

Small molecules with activity for FPR or FPRL1

| Receptor and Activity |

Small Molecule Compound |

Binding Kiaor IC50b (μM) |

Ca2+Response EC50 (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPR Antagonist | 3570-0208 | 0.095a | - | Fig. 4 |

| 24428144 | 0.55a | - | Fig. 4 | |

| 24428974 | 0.75a | - | Fig. 4 | |

| H3335-0327 | 2a | - | (42) | |

| I2293-2337 | 3a | - | (42) | |

| B6359-0291 | 4a | - | (42) | |

| D4622-8438 | 4a | - | (42) | |

| E1682-2106 | 4a | - | (42) | |

| FPR Agonist | 14 | - | 0.63 | (55) |

| 104 | - | 12.2 | (55) | |

| A1910-5441 | 1a | 20 | (42) | |

| FPRL1 Antagonist | BB-V-115 | 0.17a | - | Fig. 4 |

| 796276 | 1.84a | Fig. 4 | ||

| C7 | 2.2a/6.7b | - | Fig. 5A, (45) | |

| 2992722 | 3.22 | Fig. 4 | ||

| FPRL1 Agonist | 24 | - | 0.03 | (43) |

| 43 | - | 0.044 | (43) | |

| 1 | - | 0.3 | (56) | |

| C1 | 0.092b | 0.47 | (44,45) | |

| 2 | - | 0.6 | (42) | |

| C5 | 0.174b | 1.48 | (45) |

We have previously reported results of small scale flow cytometry screens in 96-well format to identify novel FPR ligands (42,49). The first was done with a small 880 compound library containing well characterized off-patent drugs as a means of validating the ability of our flow cytometry screening platform to detect known FPR-active structures (49). In the subsequent FPR study (42), flow cytometry screening was performed on a small focused library created on the basis of computational modeling and pre-screening of a large commercial compound library “in silico” to putatively enrich for active compounds. In the present study a substantially larger and more structurally diverse compound collection was physically screened without any a priori selection. Thus, the present study provided a context for comparing the efficacy of two approaches to screening. That 4 of the 5 most active compounds in the present FPR series were from two structural chemotype families identified in the previous study is supportive of the efficacy and increased efficiency of the computational pre-selection approach. On the other hand the larger physical screen picked up a novel active family, CF8 (Fig. 4), missed by the original computational approach.

In the present study we also demonstrated a significant extension of flow cytometric screening capabilities of the HyperCyt HTS platform to include routine screening in 384-well format and simultaneous screening of two FPR family receptors in a single assay well volume. Parallel analysis of the two receptors not only reduced test compound, fluorescent probe, and flow cytometry analysis time requirements per target receptor, but also provided receptor specificity information as an inherent assay reporting feature throughout the screening process.

The concept of assay multiplexing in flow cytometry has long been appreciated for application to bead-based assays (50,51). Multiple cell subpopulations resolved by polychromatic fluorescent probes and light scattering properties have also been historically amenable to parallel analysis via flow cytometry (52). Color coding of cells with non-specific fluorescent dyes was recently used to enable parallel analysis of multiple intracellular signaling pathways in otherwise homogeneous populations of cells (53,54). Such color-coding was used as a well address tag method to distinguish the treatments, different for each well, to which the cells had been exposed. This allowed cells from multiple wells to be pooled at the end of treatment and evaluated in a single round of flow cytometry analysis (54). The present screening study illustrated a somewhat simpler color-coding approach that allowed two cell populations to be resolved in each well. Rapid air gap partitioned sampling and analysis were used to distinguish the microplate well provenance of cells and corresponding treatments to which they were subjected. An advantage of this approach was that bulk preparations of cells could be separately color coded and pooled prior to addition to wells. This enabled a simple mix and measure assay approach in which compounds, cells and fluorescent ligand were added in three sequential steps and no further manipulations were required prior to sampling and analysis. This color coding approach can be readily extended to accommodate higher degrees of assay multiplexing without compromising the mix and measure capability.

The screening of a collection of more than 25,000 compounds in the present study represented a significant increase relative to collections we have screened in previous studies (42,49). We have also recently demonstrated the use of the HyperCyt HTS platform to successfully screen more than 190,000 compounds in multiplex bead-based assays to identify small molecule inhibitors of Ras and Ras-related GTPases (PubChem assay identifier numbers 757, 758, 759, 760, 761 and 764; manuscript in preparation). Modern HTS campaigns typically involve evaluating collections of several hundreds of thousands to millions of compounds and this represents a throughput challenge for the platform in its current configuration. However, it is important to note that the present study confirmed the concept that in combination with appropriate cheminformatics methods even modest screening campaigns can lead to identification of biological probe molecules of useful potency (42). This was further illustrated by the differences in receptor-selective hit rates in the first round of screening, involving a relatively random collection of compounds (Fig 3A), and in the second round in which cheminformatics analysis guided the construction of much smaller, receptor-targeted compound collections for follow up screening (Fig 3B and 3C). The HTS hit rates increased 23-fold for FPR (from 0.13% to 3%) and 25-fold for FPRL1 (from 0.3% to 7.6%) (Table 1). The percentage of compounds with Ki below the 4 μM threshold increased 11- and 116-fold respectively (Table 1). Thus, judicious application of cheminformatics techniques significantly enhanced the efficiency of the probe identification process for both receptor targets.

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH R03 MH076381-01, U54 MH074425-01, the New Mexico Molecular Libraries Screening Center, the University of New Mexico Shared Flow Cytometry Resource and Cancer Research and Treatment Center. It was presented in part at the 24th ISAC Congress, Budapest, Hungary, May, 2008. In accordance with our mission as a screening center in the NIH Molecular Libraries Screening Network, comprehensive assay data from various stages of screening have been published on the PubChem website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=pcassay) under the following assay identifier (AID) numbers: 440, 441, 519, 520, 698, 699, 722, 723, 724, 725, 762, 763, 765, 766, 863, 1061, 805 and 1202. The last two reference summary reports that organize information about the screening stages and active test compounds identified in FPR and FPRL1 assays, respectively.

Literature Cited

- 1.Le Y, Murphy PM, Wang JM. Formyl-peptide receptors revisited. Trends Immunol. 2002;23(11):541–8. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oppenheim JJ, Zachariae CO, Mukaida N, Matsushima K. Properties of the novel proinflammatory supergene “intercrine” cytokine family. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:617–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.003153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy PM. The N-formylpeptide chemotactic receptor. In: Horuk R, editor. Chemoattractant ligands and their receptors. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1996. pp. 269–299. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Le Y, Oppenheim JJ, Wang JM. Pleiotropic roles of formyl peptide receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2001;12(1):91–105. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(01)00003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy PM. The molecular biology of leukocyte chemoattractant receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:593–633. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.003113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He R, Sang H, Ye RD. Serum amyloid A induces IL-8 secretion through a G protein-coupled receptor, FPRL1/LXA4R. Blood. 2003;101(4):1572–81. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tiffany HL, Lavigne MC, Cui YH, Wang JM, Leto TL, Gao JL, Murphy PM. Amyloid-beta induces chemotaxis and oxidant stress by acting at formylpeptide receptor 2, a G protein-coupled receptor expressed in phagocytes and brain. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(26):23645–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101031200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schiffmann E, Showell HV, Corcoran BA, Ward PA, Smith E, Becker EL. The isolation and partial characterization of neutrophil chemotactic factors from Escherichia coli. J Immunol. 1975;114(6):1831–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schiffmann E, Corcoran BA, Wahl SM. N-formylmethionyl peptides as chemoattractants for leucocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72(3):1059–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.3.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marasco WA, Phan SH, Krutzsch H, Showell HJ, Feltner DE, Nairn R, Becker EL, Ward PA. Purification and identification of formyl-methionylleucyl-phenylalanine as the major peptide neutrophil chemotactic factor produced by Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1984;259(9):5430–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carp H. Mitochondrial N-formylmethionyl proteins as chemoattractants for neutrophils. J Exp Med. 1982;155(1):264–75. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.1.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao JL, Lee EJ, Murphy PM. Impaired antibacterial host defense in mice lacking the N-formylpeptide receptor. J Exp Med. 1999;189(4):657–62. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.4.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walther A, Riehemann K, Gerke V. A novel ligand of the formyl peptide receptor: annexin I regulates neutrophil extravasation by interacting with the FPR. Mol Cell. 2000;5(5):831–40. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80323-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou Y, Bian X, Le Y, Gong W, Hu J, Zhang X, Wang L, Iribarren P, Salcedo R, Howard OM. and others. Formylpeptide receptor FPR and the rapid growth of malignant human gliomas J Natl Cancer Inst 20059711823–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yao XH, Ping YF, Chen JH, Chen DL, Xu CP, Zheng J, Wang JM, Bian XW. Production of angiogenic factors by human glioblastoma cells following activation of the G-protein coupled formylpeptide receptor FPR. J Neurooncol. 2008;86(1):47–53. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9443-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bao L, Gerard NP, Eddy RL, Jr., Shows TB, Gerard C. Mapping of genes for the human C5a receptor (C5AR), human FMLP receptor (FPR), and two FMLP receptor homologue orphan receptors (FPRH1, FPRH2) to chromosome 19. Genomics. 1992;13(2):437–40. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(92)90265-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy PM, Ozcelik T, Kenney RT, Tiffany HL, McDermott D, Francke U. A structural homologue of the N-formyl peptide receptor. Characterization and chromosome mapping of a peptide chemoattractant receptor family. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(11):7637–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ye RD, Cavanagh SL, Quehenberger O, Prossnitz ER, Cochrane CG. Isolation of a cDNA that encodes a novel granulocyte N-formyl peptide receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;184(2):582–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)90629-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nomura H, Nielsen BW, Matsushima K. Molecular cloning of cDNAs encoding a LD78 receptor and putative leukocyte chemotactic peptide receptors. Int Immunol. 1993;5(10):1239–49. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.10.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prossnitz ER, Ye RD. The N-formyl peptide receptor: a model for the study of chemoattractant receptor structure and function. Pharmacol Ther. 1997;74(1):73–102. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(96)00203-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Su SB, Gong W, Gao JL, Shen W, Murphy PM, Oppenheim JJ, Wang JM. A seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor, FPRL1, mediates the chemotactic activity of serum amyloid A for human phagocytic cells. J Exp Med. 1999;189(2):395–402. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Le Y, Gong W, Tiffany HL, Tumanov A, Nedospasov S, Shen W, Dunlop NM, Gao JL, Murphy PM, Oppenheim JJ. and others. Amyloid (beta)42 activates a G-protein-coupled chemoattractant receptor, FPR-like-1 J Neurosci 2001212RC123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Y, Yazawa H, Gong W, Yu Z, Ferrans VJ, Murphy PM, Wang JM. The neurotoxic prion peptide fragment PrP(106-126) is a chemotactic agonist for the G protein-coupled receptor formyl peptide receptor-like 1. J Immunol. 2001;166(3):1448–51. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snipe JD. The acute phase response. In: Oppenheim JJ, Shevac EM, editors. Immunophysiology: the role of cells and cytokines in immunity and inflammation. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 1990. pp. 259–273. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lambert MP, Barlow AK, Chromy BA, Edwards C, Freed R, Liosatos M, Morgan TE, Rozovsky I, Trommer B, Viola KL. and others. Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Abeta1-42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 199895116448–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalaria RN. Microglia and Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Opin Hematol. 1999;6(1):15–24. doi: 10.1097/00062752-199901000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown DR, Schmidt B, Kretzschmar HA. Role of microglia and host prion protein in neurotoxicity of a prion protein fragment. Nature. 1996;380(6572):345–7. doi: 10.1038/380345a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le Y, Yang Y, Cui Y, Yazawa H, Gong W, Qiu C, Wang JM. Receptors for chemotactic formyl peptides as pharmacological targets. Int Immunopharmacol. 2002;2(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(01)00150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yazawa H, Yu ZX, Takeda, Le Y, Gong W, Ferrans VJ, Oppenheim JJ, Li CC, Wang JM. Beta amyloid peptide (Abeta42) is internalized via the G-protein-coupled receptor FPRL1 and forms fibrillar aggregates in macrophages. Faseb J. 2001;15(13):2454–62. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0251com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Y, Chen Q, Schmidt AP, Anderson GM, Wang JM, Wooters J, Oppenheim JJ, Chertov O. LL-37, the neutrophil granule- and epithelial cell-derived cathelicidin, utilizes formyl peptide receptor-like 1 (FPRL1) as a receptor to chemoattract human peripheral blood neutrophils, monocytes, and T cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192(7):1069–74. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiang N, Fierro IM, Gronert K, Serhan CN. Activation of lipoxin A(4) receptors by aspirin-triggered lipoxins and select peptides evokes ligand-specific responses in inflammation. J Exp Med. 2000;191(7):1197–208. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.7.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Su SB, Gao J, Gong W, Dunlop NM, Murphy PM, Oppenheim JJ, Wang JM. T21/DP107, A synthetic leucine zipper-like domain of the HIV-1 envelope gp41, attracts and activates human phagocytes by using G-protein-coupled formyl peptide receptors. J Immunol. 1999;162(10):5924–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Le Y, Jiang S, Hu J, Gong W, Su S, Dunlop NM, Shen W, Li B, Wang Ming J. N36, a synthetic N-terminal heptad repeat domain of the HIV-1 envelope protein gp41, is an activator of human phagocytes. Clin Immunol. 2000;96(3):236–42. doi: 10.1006/clim.2000.4896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.VanCompernolle SE, Clark KL, Rummel KA, Todd SC. Expression and function of formyl peptide receptors on human fibroblast cells. J Immunol. 2003;171(4):2050–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin C, Wei W, Zhang J, Liu S, Liu Y, Zheng D. Formyl peptide receptor-like 1 mediated endogenous TRAIL gene expression with tumoricidal activity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6(10):2618–25. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCoy R, Haviland DL, Molmenti EP, Ziambaras T, Wetsel RA, Perlmutter DH. N-formylpeptide and complement C5a receptors are expressed in liver cells and mediate hepatic acute phase gene regulation. J Exp Med. 1995;182(1):207–17. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sozzani S, Sallusto F, Luini W, Zhou D, Piemonti L, Allavena P, Van Damme J, Valitutti S, Lanzavecchia A, Mantovani A. Migration of dendritic cells in response to formyl peptides, C5a, and a distinct set of chemokines. J Immunol. 1995;155(7):3292–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lacy M, Jones J, Whittemore SR, Haviland DL, Wetsel RA, Barnum SR. Expression of the receptors for the C5a anaphylatoxin, interleukin-8 and FMLP by human astrocytes and microglia. J Neuroimmunol. 1995;61(1):71–8. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(95)00075-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keitoku M, Kohzuki M, Katoh H, Funakoshi M, Suzuki S, Takeuchi M, Karibe A, Horiguchi S, Watanabe J, Satoh S. and others. FMLP actions and its binding sites in isolated human coronary arteries J Mol Cell Cardiol 1997293881–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gronert K, Gewirtz A, Madara JL, Serhan CN. Identification of a human enterocyte lipoxin A4 receptor that is regulated by interleukin (IL)-13 and interferon gamma and inhibits tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced IL-8 release. J Exp Med. 1998;187(8):1285–94. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.8.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Le Y, Hu J, Gong W, Shen W, Li B, Dunlop NM, Halverson DO, Blair DG, Wang JM. Expression of functional formyl peptide receptors by human astrocytoma cell lines. J Neuroimmunol. 2000;111(1-2):102–8. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(00)00373-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Edwards BS, Bologa C, Young SM, Balakin KV, Prossnitz E, Savchuck NP, Sklar LA, Oprea TI. Integration of virtual screening with high throughput flow cytometry to identify novel small molecule formylpeptide receptor antagonists. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:1301–1310. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.014068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burli RW, Xu H, Zou X, Muller K, Golden J, Frohn M, Adlam M, Plant MH, Wong M, McElvain M. and others. Potent hFPRL1 (ALXR) agonists as potential anti-inflammatory agents Bioorg Med Chem Lett 200616143713–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nanamori M, Cheng X, Mei J, Sang H, Xuan Y, Zhou C, Wang MW, Ye RD. A novel nonpeptide ligand for formyl peptide receptor-like 1. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66(5):1213–22. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.004309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou C, Zhang S, Nanamori M, Zhang Y, Liu Q, Li N, Sun M, Tian J, Ye PP, Cheng N. and others. Pharmacological characterization of a novel nonpeptide antagonist for formyl peptide receptor-like 1 Mol Pharmacol 2007724976–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramirez S, Aiken CT, Andrzejewski B, Sklar LA, Edwards BS. High-throughput flow cytometry: Validation in microvolume bioassays. Cytometry. 2003;53A(1):55–65. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.10035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuckuck FW, Edwards BS, Sklar LA. High throughput flow cytometry. Cytometry. 2001;44(1):83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Munson PJ, Rodbard D. An exact correction to the “Cheng-Prusoff” correction. J Recept Res. 1988;8(1-4):533–46. doi: 10.3109/10799898809049010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Young SM, Bologa C, Prossnitz E, Oprea TI, Sklar LA, Edwards BS. High throughput screening with HyperCyt flow cytometry to detect small molecule formylpeptide receptor ligands. J Biomol Screen. 2005;10(4):374–382. doi: 10.1177/1087057105274532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kettman JR, Davies T, Chandler D, Oliver KG, Fulton RJ. Classification and properties of 64 multiplexed microsphere sets. Cytometry. 1998;33(2):234–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nolan JP, Sklar LA. Suspension array technology: evolution of the flat-array paradigm. Trends Biotechnol. 2002;20(1):9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(01)01844-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shapiro HM. Alan R. Liss; New York: 1988. Practical Flow Cytometry. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perez OD, Nolan GP. Simultaneous measurement of multiple active kinase states using polychromatic flow cytometry. Nat.Biotechnol. 2002;20(2):155–162. doi: 10.1038/nbt0202-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krutzik PO, Nolan GP. Fluorescent cell barcoding in flow cytometry allows high-throughput drug screening and signaling profiling. Nat Methods. 2006;3(5):361–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schepetkin IA, Kirpotina LN, Khlebnikov AI, Quinn MT. High-throughput screening for small-molecule activators of neutrophils: identification of novel N-formyl peptide receptor agonists. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71(4):1061–74. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.033100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schepetkin IA, Kirpotina LN, Tian J, Khlebnikov AI, Ye RD, Quinn MT. Identification of novel formyl peptide receptor-like 1 agonists that induce macrophage tumor necrosis factor alpha production. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74(2):392–402. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.046946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]