Abstract

Understanding the molecular mechanisms by which cartilage formation is regulated is essential toward understanding the physiology of both embryonic bone development and postnatal bone growth. Although much is known about growth factor signaling in cartilage formation, the regulatory role of noncollagenous matrix proteins in this process are still largely unknown. In the present studies, we present evidence for a critical role of DMP1 (dentin matrix protein 1) in postnatal chondrogenesis. The Dmp1 gene was originally identified from a rat incisor cDNA library and has been shown to play an important role in late stage dentinogenesis. Whereas no apparent abnormalities were observed in prenatal bone development, Dmp1-deficient (Dmp1−/−) mice unexpectedly develop a severe defect in cartilage formation during postnatal chondrogenesis. Vertebrae and long bones in Dmp1-deficient (Dmp1−/−) mice are shorter and wider with delayed and malformed secondary ossification centers and an irregular and highly expanded growth plate, results of both a highly expanded proliferation and a highly expanded hypertrophic zone creating a phenotype resembling dwarfism with chondrodysplasia. This phenotype appears to be due to increased cell proliferation in the proliferating zone and reduced apoptosis in the hypertrophic zone. In addition, blood vessel invasion is impaired in the epiphyses of Dmp1−/− mice. These findings show that DMP1 is essential for normal postnatal chondrogenesis and subsequent osteogenesis.

Most of the vertebrate appendicular and axial skeleton is formed through endochondral ossification, which occurs in the epiphysis and growth plate. During development, mesenchymal stem cells first differentiate into cartilage, which acts as a template and determines the shape of future bone. After formation, cartilage is removed and replaced by bone. Considerable progress has been made in the last decade in identifying the mechanisms responsible for prenatal longitudinal bone growth, which is initiated and controlled by factors such as parathyroid hormone-related peptide, Indian hedgehog, and fibroblast growth factor (1, 2). Parathyroid hormone-related peptide maintains chondrocyte proliferation, whereas Indian hedgehog controls and accelerates chondrocyte differentiation. This is balanced by fibroblast growth factor signaling, which retards chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation. In addition, Runx2/Cbfa1 signaling plays a critical role in this process by stimulating hypertrophic chondrocyte maturation (3-6). However, mechanisms for regulating postnatal growth and development of cartilage are not as well characterized. This is important because there are numerous skeletal diseases that first manifest in childhood and worsen with age such as chondrodysplasias (7).

DMP1 belongs to a glycosylated and phosphorylated group of proteins, called SIBLINGs for small, integrin-binding ligand, N-linked glycoproteins. These molecules share similar genomic and biochemical features. The members of this family also include bone sialoprotein, osteopontin (OPN),1 dentin sialophosphoprotein (DSPP), and matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein. All of these family members bind hydroxyapatite (8, 9). Bone sialoprotein, OPN, and DMP1 also bridge complement Factor H to cell surface receptors, an alternative complement pathway to prevent cell lysis (8, 9). Furthermore, the SIBLING proteins can interact with integrin and CD44 receptors, and their integrin interactions are usually mediated through the RGD motif (10). CD44 is a membrane bound protein thought to interact with the ERM (ezrin, radixin, and moesin) family of adapter proteins that link to actin in the cytoskeleton. Although many in vitro studies have indicated that the various family members have specific biological activities, none of the knock-out animals in which these molecules have been ablated have shown an apparent bone phenotype.

With regards to the function of DMP1, it has been reported that overexpression of Dmp1 in vitro induces differentiation and mineralization of mesenchymal stem cells (11). However, the effects of recombinant DMP1 on in vitro mineralization are controversial and depend on phosphorylation state (12). In vivo, Dmp1 is mainly expressed in mineralizing tissues in cells such as hypertrophic chondrocytes, osteoblasts, and osteocytes (13-16). First observations showed that Dmp1−/− embryos and newborns displayed no apparent skeletal nor tooth phenotype, suggesting that DMP1 may be redundant or nonessential for early dentinogenesis and osteogenesis (17). However, postnatally, Dmp1−/− mice develop a profound tooth formation defect characterized by a partial failure of maturation of predentin into dentin, enlarged pulp chambers, increased width of the predentin zone with reduced dentin wall thickness and hypomineralization (18). This tooth phenotype is strikingly similar to that in Dspp null mice (19) and shares some of the features of dentinogenesis imperfecta III in humans.

In a search for mechanisms controlling postnatal bone and cartilage morphogenesis, we have investigated the role of an extracellular matrix protein, DMP1 (20), in postnatal cartilage formation. Here we report changes in chondrocyte morphology, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis in postnatal Dmp1−/− mice. We found that Dmp1 is essential for postnatal cartilage formation, especially for the cell fate of hypertrophic chondrocytes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

The Dmp1−/− mice were generated with exon 6 deletion as described previously (17). The control, wild type (WT), heterozygous (Dmp1+/−), and homozygous (Dmp1−/−) null mice were maintained on a C57BL/6 or CD-1 background. The animal protocol for their use was approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees in University of Missouri-Kansas City and NIEHS, National Institutes of Health.

X-ray Radiography and Micro-computed Tomography

WT, Dmp1+/−, and Dmp1−/− mice (from newborn to 12 months of age) were examined radiographically using a specimen radiography system (model MX-20; Faxitron, Buffalo Grove, Illinois). The tibiae from 1- and 12-month-old control and null or knock-out (KO) mice were scanned using a compact fan beam-type tomograph (Micro-CT 40; Scanco Medical AG, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) (21).

Backscattered Scanning Electron Microscopy

Femurs from WT and Dmp1−/− mice were dissected and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 m cacodylate buffer solution (pH 7.4) at room temperature for 4 h and then transferred to 0.1 m cacodylate buffer solution. After dehydration in ascending concentrations of ethanol, the bones were fractured under a dissecting microscope and mounted on aluminum stubs with the fractured surface upward facing, sputter-coated with gold and palladium, and examined with field emission scanning electron microscopy (Philips XL30, FEI Company, Oregon).

Preparation of Decalcified Paraffin, Methylmethacrylate, and Frozen Sections

To analyze morphological changes, skeletal tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h (22). One hind limb was decalcified and embedded in paraffin, and the other hind limb was embedded in methylmethacrylate (22). Frozen sections were prepared on 10- and 19-day-old animals. Histological analyses were performed on both femoral and tibial bone from 10-day-old to 5-month-old WT and Dmp1−/− mice.

Histological Staining and Preparation

Nondecalcified sections were used for Goldner's Masson Trichrome staining (22). Safranin-O staining was used for visualizing proteoglycans (23). Slides containing femoral growth plates were stained with 5′-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine to detect proliferating cells according to the manufacturer's instructions (Sigma).

Histomorphometry

The length of each of the chondrocyte zones, the resting, proliferation, and hypertrophic zones, in femoral growth plates were measured using the software of OsteoMeasure System (version 4.1, Atlanta, GA) from a minimum of 20 measurements/section. Lines were drawn between each zone, and the average distance was determined. A minimum of three animals/group were used.

To determine the epiphyseal and metaphyseal areas, tibia from 3-week-old animals (n = 5) were first radiographed. Then the OsteoMeasure system was used to measure the total area above the growth plate for epiphyses, and the area below the growth plate was used for metaphyses. The Student's t test was used to determine significant differences between groups, the Dmp1−/− and the control group.

Immunohistochemistry

The Cleaved Caspase 3 (Asp175) antibody from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA) was used for detection of apoptotic cells, and platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1) monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz, CA) was used for detecting endothelial cells in blood vessels. The monoclonal antibody against collagen type II was purchased from Lab Vision Corporation (Fremont, CA), and the polyclonal antibody against collagen type X was a gift from Dr. Gregory Lunstrum (Portland Research Center, Oregon). Anti-OPN antibody was obtained from Dr. Larry Fisher (NIDCR, National Institutes of Health), and anti-matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) polyclonal antibody was purchased from Affinity Bioreagents (Golden, CO). After deparaffinization and rehydration, the sections were immersed in 3% H2O2 to quench endogenous peroxidase and further digested with 1 mg/ml trypsin for 30 min at 37 °C. Sections were then blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin containing 1% serum at room temperature for 2 h. The primary antibodies were added to the sections and incubated overnight at 4 °C. After washing, the sections were coated with biotinylated second antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) at a dilution of 1:200 and then incubated at room temperature for 60 min. The sections were washed again and incubated with the ABC reagent (Vector Laboratories) at room temperature for 60 min. The 3,3′-diaminobenzidine substrate was used to visualize immunoreaction sites. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and mounted on glass slides. Negative controls were obtained by substituting the primary antibody with normal serum or normal IGG.

In Situ Hybridization for VEGF

The mouse VEGF mRNA was used for in situ hybridization as described previously (16). Briefly, the digoxigenin-labeled VEGF cRNA was prepared by using an RNA labeling kit (Roche Applied Science). The hybridization temperature was set at 55 °C, and the washing temperature was set at 70 °C so that endogenous alkaline phosphatase is inactivated. Digoxigenin-labeled nucleic acids were detected in an enzyme-linked immunoassay with a specific anti-digoxigenin-alkaline phosphatase antibody conjugate, and the color substrates nitro blue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate were used according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Applied Science).

MMP9 Expression and Activity

To determine whether the activity of MMP9/gelatinase B is altered in the null mice, the femoral-tibial joint was dissected free from skin and muscle followed by homogenization in 0.01 m Tris-Cl (pH 7.2) solution. Normalized sample aliquots (10 μg) were mixed with 3 μl of 5× zymogram loading buffer and then subjected to SDS-PAGE using 7.5% polyacrylamide gels containing 1 mg/ml of gelatin. After electrophoresis, the gels were washed in 2.5% Triton X-100 renaturing buffer and incubated overnight at 37 °C in developing buffer (50 mm Tris, 0.2 m NaCl, 5 mm CaCl2, and 0.02% Brij 35) followed by staining with Coomassie Blue.

RESULTS

Dmp1−/− Mice Exhibit a Chondrodysplasia-like Phenotype

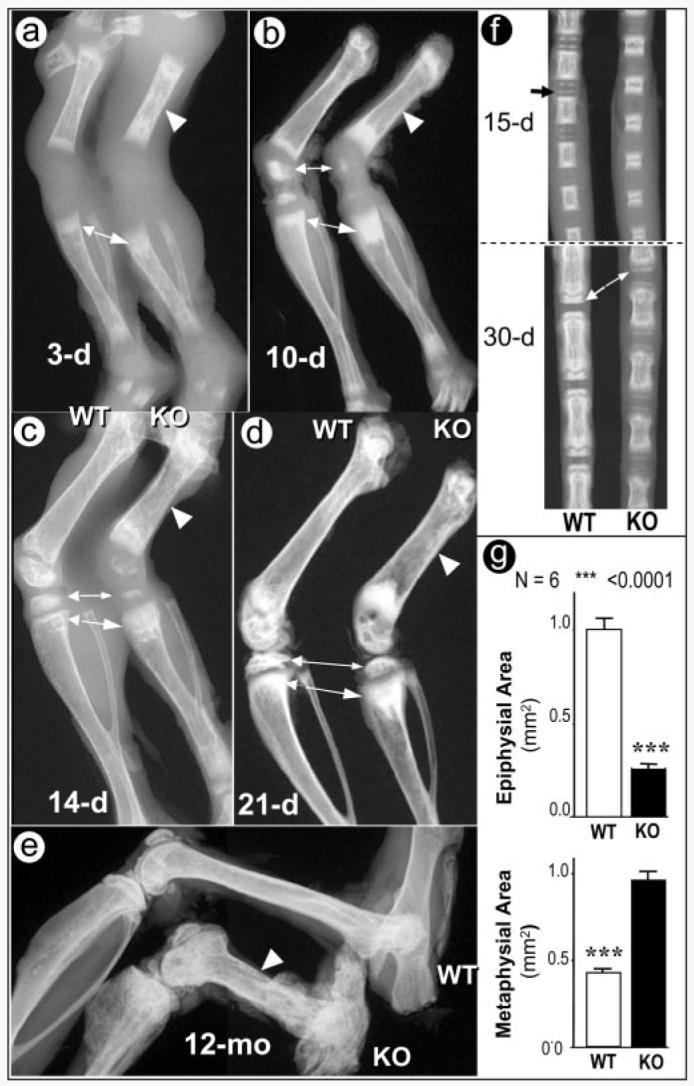

To determine the role of Dmp1 in skeletal development and growth, we generated Dmp1−/− null (KO) mice (17). The bones of Dmp1+/− heterozygote mice were similar to the WT littermates with comparable weight, growth rates, and radio-graphic and histological appearance, suggesting that the loss of a single copy of the Dmp1 gene has no apparent effect on skeletal development (data not shown). At birth, the Dmp1−/− mice show no visible gross skeletal abnormalities by radiographic analysis (data not shown). However, the Dmp1−/− null mice develop an age-dependent defect in skeletal formation similar to human conditions of chondrodysplasia (Fig. 1). This phenotype is evident at 10 days after birth and progresses with age. The major abnormalities observed in Dmp1−/− mice are decreased endochondral ossification, failure to lengthen, increases in width, and flaring at the metaphyses or ends of the long bones (Fig. 1). These abnormalities appear to be 100% penetrant and progressively worsen with age (Fig. 1e). Radiographic analysis revealed that the midshafts of the Dmp1−/− long bones are wider and fail to form a normal diaphysis compared with the control littermates (Fig. 1, a–e). A delay in appearance of the secondary ossification center of the epiphysis occurs concurrently with an expansion of the metaphysis in the long bone as shown at days 10, 14, and 21 (Fig. 1, b–d; quantitated in Fig. 1g), as well as in vertebrae at days 15 and 30 that are also shorter and wider than controls (Fig. 1f). Photographs of tibia/fibula emphasize the dysplastic phenotype (Fig. 2a). Quantitative measurement of these long bones showed a significant decrease in length and a significant increase in width of tibia from the Dmp1−/− null mice (Fig. 2b). Micro-CT analysis further confirmed the delayed and malformed epiphyses in Dmp1−/− mice (Fig. 2, c and d). Also noted by micro-CT was increased porosity and an expanded growth plate.

Fig. 1. Progressive changes of long bone structure in the Dmp1−/− mice.

Representative radiographs of hind limbs from 3- (a), 10- (b), 14- (c), and 21-day-old (d) and 12-month-old animals (e). The shorter long bones with wider shafts of Dmp1−/− bones (KO) femurs are indicated by arrowheads, the delayed epiphyses are indicated by small arrows, and the expanded metaphyses are indicated by large arrows. Radiographs of tail vertebrae from 15- and 30-day-old mice show delayed formation of epiphyses and shortened vertebral bodies (f). Quantitative data for the extent of epiphyseal and metaphyseal ossification show a reduction in epiphysial area but an increase in metaphyseal area in Dmp1−/− mice (g).

Fig. 2. Analyses of deformed tibias in Dmp1−/− mice.

Photographs (a) and quantitative (b) analyses of tibias from 3-week-old and 3- and 5-month-old animals. A significant difference is observed between the WT and the mutant (KO) tibiae in both length and width. Representative three-dimensional micro-CT reconstruction of 1-month-old tibiae with whole mount view (c) and sagittal section view (d) are shown. The secondary ossification center is delayed and malformed (arrows), and the growth plate is dramatically expanded (arrowheads) in the tibia from Dmp1−/− mice.

Severe Abnormalities in Growth Plates in Dmp1−/− Mice

Images using backscattered scanning electron microscopy that allow visualization of mineralized tissues (bright area) show clear separation of the epiphysis and metaphyseal by the sharply demarcating growth plate in WT mice (Fig. 3a, upper panel). In contrast, the growth plate from Dmp1−/− mice appears as an irregular and discontinuous band poorly separating the epiphysis and metaphysis, and the bone appears hypomineralized (Fig. 3a, lower panel). Histological examination using safranin-O staining revealed that the well ordered vertical columns of chondrocytes observed in the WT growth plate were replaced by a disorganized and irregular growth plate with a dramatically expanded hypertrophic zone in Dmp1−/− mice (Fig. 3, c and d). Quantitation of the lengths of the proliferation zone and the hypertrophic zone showed a significant increase in both in the Dmp1−/− mice compared with wild type at the age of 3 weeks (Fig. 4d).

Fig. 3. Malformed growth plates in the Dmp1−/− mice.

Images from backscattered scanning electron microscopy of 6-week-old and 6- and 12-month-old mice. Well formed growth plate (arrows), epiphyses and metaphyses can be easily seen in the WT mice (a, upper panel). The growth plate of Dmp1−/− mice however, is expanded and disorganized with malformed epiphyses and metaphyses (a, lower panel, arrows). Representative sections from decalcified femurs, stained with Safranin-O show a striking expansion of the growth plate at the age of 3 weeks and irregularities at 3 months and complete disruption at 5 months in the Dmp1−/− null mice (b, lower panel) compared with the WT growth plates (b, upper panel). Visually, histology shows an increased proliferation and hypertropic zone (c). Quantitative histomorphometry shows a significant increase in the proliferation zone of almost a doubling and in the hypertrophic zone of a 3-fold increase in femurs of 3-month-old Dmp1−/− mice compared with wild type controls (d). PZ, proliferation zone; HZ, hypertrophic zone.

Fig. 4. Increased proliferation, reduced apoptosis, and reduced calcification of the cartilaginous matrix and trabecular bone in the Dmp1−/− mice.

A significant increase in cell proliferation as detected using bromodeoxyuridine labeling was observed in tibial growth plate of 2-month-old Dmp1−/− mice (a, arrows). No apparent difference in intensity of type II (b, arrowheads) and type X (c) collagen expression was observed in femora of 3-week-old Dmp1−/− mice. Caspase 3 staining showed a significant decrease in apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes in 3-week-old Dmp1−/− mice (d). Goldner's Masson Trichrome staining of a tibial growth plate displays an expanded, disorganized growth plate, a poorly calcified cartilage matrix, and reduced trabecular bone formation in a 3-month-old Dmp1−/− mouse (e). PC, proliferating chondrocyte; HC, hypertrophic chondrocyte.

Alterations in Chondrocyte Proliferation, and Apoptosis in Dmp1−/− Mice

To determine the underlying mechanisms for the morphological abnormalities of the growth plate of Dmp1−/− mice, we examined changes in chondrocyte proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. Bromodeoxyuridine labeling of the proliferating cells shows that chondrocyte proliferation in the proliferation zone was increased ∼4-fold in 2-month-old Dmp1−/− mice (Fig. 4a), suggesting that a greater number of chondrocytes enter the hypertrophic zone. We then examined changes in chondrocyte differentiation, using the marker genes, type IIα collagen (expressed in proliferating and mature chondrocytes) and type X collagen (expressed in hypertrophic chondrocytes). We found no significant differences in staining intensity in type IIα and type X collagen expression in growth plates from either the WT or Dmp1−/− mice (Fig. 4, b and c). Next, we determined the extent of programmed cell death or apoptosis using the caspase 3 immunostain (Fig. 5d). Quantitative data show that the percentage of apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes was reduced over 70% in the null mice (Fig. 5d). Subsequently, changes in mineralization in Dmp1−/− mice compared with WT mice were determined using Goldner staining of nondecalcified sections of tibial growth plates from 3-month-old mice. The normal growth plate is composed of well ordered, vertical columns of chondrocytes with few hypertrophic chondrocytes, and the subchondral vascular resorption front is of uniform size with well mineralized trabecular bone (Fig. 4e, left panel). In contrast, the Dmp1−/− growth plate was thicker and disorganized and exhibited a dramatic increase in the proportion of hypertrophic chondrocytes. The matrix surrounding the hypertrophic chondrocytes was poorly calcified (Fig. 5e, right panel, arrows). There is also reduced trabecular bone formation. These observations suggest that the normal function of DMP1 is to control the function of the growth plate by reducing chondrocyte proliferation and enhancing the final differentiation step for the growth plate chondrocyte, apoptosis. These observations also suggest that DMP1 is essential for the transition of chondrogenesis to osteogenesis.

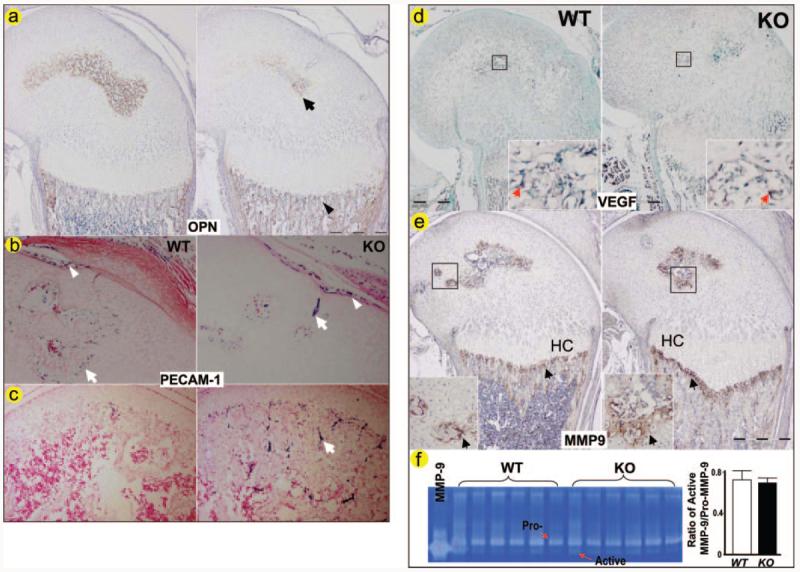

Fig. 5. Delayed blood vessel invasion in Dmp1−/− epiphyses.

Polyclonal antibody against OPN (a), a marker of new bone formation is reduced in the KO epiphysis (arrow) but increased in the KO metaphysis (arrowhead) from a 3-week-old animal. Monoclonal antibody against PECAM-1 was used on sections of day 10 (b) and 17 (c) femurs. The positively stained endothelial cells (in blue purple, arrows) are significantly reduced in the Dmp1−/− epiphysis at day 10, although the stained endothelial cells in surrounding areas appear normal (arrowhead). By day 17, more endothelial cells stained positive for PECAM-1 in the Dmp1−/− epiphysis compared with the control with well formed bone marrow (c, arrow). In situ hybridization was performed to examine changes in mRNA expression of VEGF (d), and immunostaining was performed to examine protein expression of MMP9 (f), and enzyme activity of MMP9 (e) were measured by genetin zymography in 10-day-old Dmp1−/− mice and the age-matched control mice (right panels). Both VEGF and MMP9 are expressed at sites of neovascularization (arrows) with no apparent difference in VEGF and MMP9 expression in Dmp1−/− mice compared with control littermates. HC, hypertrophic chondrocyte.

Delayed Blood Vessel Invasion in Dmp1−/− Mice

Blood vessel invasion is essential for bone formation and for the formation of secondary ossification centers (25, 26). Ossification is delayed in Dmp1−/− mice as indicated by notably decreased expression of OPN, a marker for ossification, in the epiphyseal area of the growth plate (Fig. 5a). To determine whether the delayed and malformed secondary ossification center observed in Dmp1−/− mice was linked to a change in blood vessel invasion, we examined the expression of PECAM-1, a marker for blood vessel endothelial cells (27), by immunostaining sections from 10- and 17-day-old femurs (Fig. 5b). In 10-day-old Dmp1−/− mice, endothelial cells staining positively for PECAM-1 were restricted to a very small region in the epiphysis compared with the control. By day 17, bone marrow is well formed in the normal epiphysis, whereas the bone marrow space in the KO epiphysis is still very limited (Fig. 5c). Another marker for angiogenesis is VEGF (28, 29), which was used for in situ hybridization assay to determine VEGF expression in 10-day-old femurs of Dmp1−/− and the littermate control mice. As shown in Fig. 5d, there was no apparent difference in VEGF expression between the Dmp1−/− mice and their wild type littermates.

MMP9 is also a key regulator of angiogenesis (28, 29), and DMP1 has been shown to bind and activate MMP9 in vitro (30). To determine whether MMP9 plays a role in the defective chondrocyte maturation in Dmp1−/− mice, we first examined the expression pattern of MMP9 in the growth plate area and found that there was no difference in MMP9 expression between the Dmp1−/− and littermate control mice (Fig. 5e). We then measured the activity of MMP9 by gelatin zymography and found no alteration in MMP9 activity in the Dmp1−/− knee joints (Fig. 5f). These results suggest that MMP9 may not be critical for the delayed angiogenesis observed in Dmp1−/− mice.

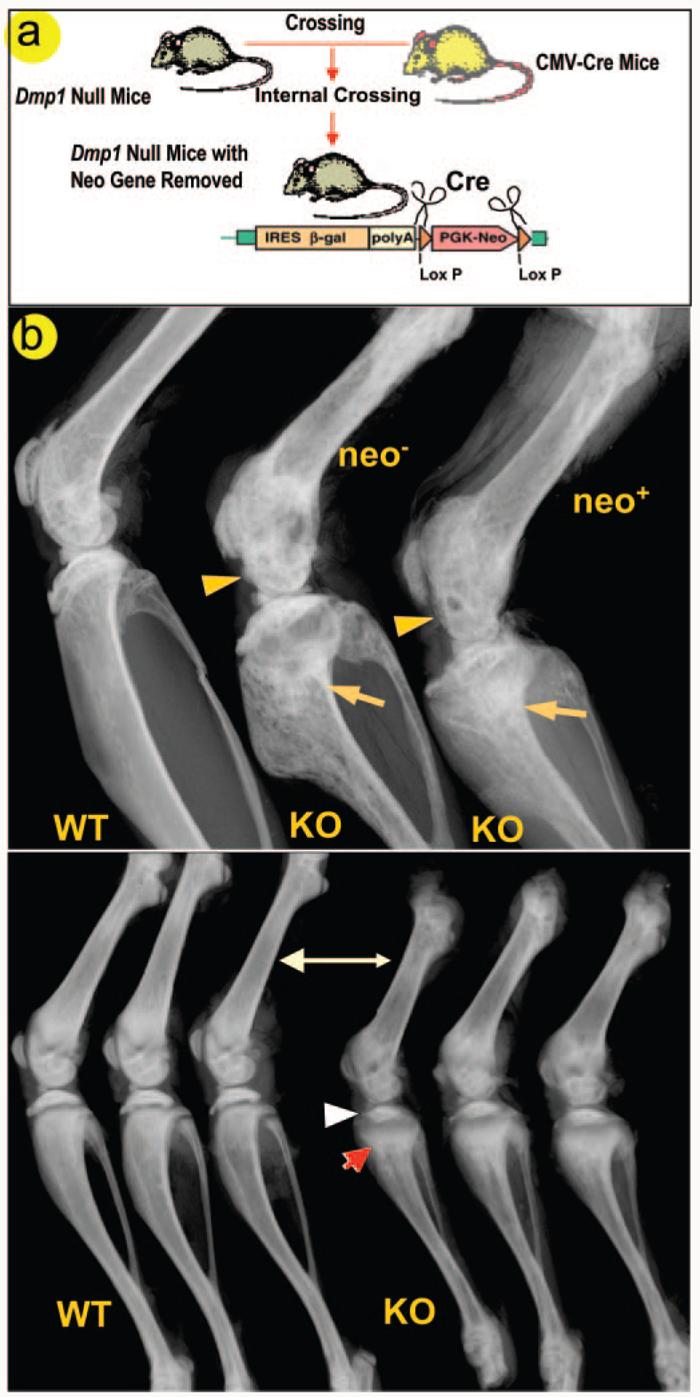

Validation of Deletion Model

To exclude the possibility that the observed bone phenotype was related to the insertion of the neo cassette in the targeting construct (31), the neo cassette was removed by crossing Dmp1−/− mice with CMV-Cre transgenic mice (32). Dmp1−/− mice with or without the neo cassette showed an identical bone phenotype (Fig. 6), suggesting that expression of the neo cassette has no effect on the skeletal phenotype in Dmp1−/− mice.

Fig. 6. Neither the mouse strain nor the neo cassette has an effect on the Dmp1−/− phenotype.

To exclude the potential effect of the neo gene that was inserted into the Dmp1 knock-out construct on the bone phenotype of Dmp1−/− mice, CMV-cre transgenic mice were crossed with Dmp1−/− mice to remove the neo gene (a). The presence or absence of the neo gene has no effect on either the malformed epiphyses (arrowheads) or metaphysis (arrows) in 4-month-old Dmp1−/− mice (b, upper panel). Because the mouse strain itself can have considerable effect on bone structure and bone mineral density (35), we compared radiographs of Dmp1 null long bone of 1-month-old animals on the C57/B6 and the CD-1 background and found no apparent differences (b, lower panel).

We also compared the skeletal phenotype in both the C57BL/6 (inbred strain) and CD-1 (outbred strain) background and found that the chondrodysplasia-like phenotype is essentially identical in both strains, demonstrating that the Dmp1 null phenotype is likely independent of influences from the genetic background of each mouse strain (Fig. 6b, lower panel).

DISCUSSION

Overlap clearly occurs in the processes by which the prenatal skeleton is formed, develops, and mineralizes with those utilized by the postnatal and adult skeleton. However, there is growing evidence that distinct differences do exist. Rapid skeletal growth occurs postnatally that is mainly dependent upon the development and function of the growth plate. Here we show that DMP1 clearly plays an essential role in the postnatal (Figs. 1-5) but not prenatal skeleton (17). Deletion of the Dmp1 gene results in a chondrodysplasia-like phenotype, starting several days to weeks after birth. The growth plate is abnormally expanded and disorganized in these mice, and epiphyseal formation and calcification is delayed. These data show that Dmp1 is required for normal growth plate development and therefore essential for normal chondrogenesis postnatally.

Normally, hypertrophic chondrocytes will undergo apoptosis after exiting from the cell cycle to yield to replacement by bone. The timing of this process is critical for endochondral bone formation. MMP9 was shown to play a role in apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes because deletion of MMP9 lead to an expansion of the growth plate because of delayed apoptosis (29). Similar to MMP9 null mice, a 3-fold reduction in apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes was observed in the DMP1 null mice. However, we could find no apparent change in MMP9 expression or activity in the DMP1 null mice. However, in contrast to the MMP9 null mice, the expanded growth in the DMP1 null mice continues to worsen with age, whereas the expanded growth plate in the MMP9 null mice is temporary and is corrected within 3 weeks after birth (30). Also, it is of note that changes in growth plate development in MMP9 null mice were only reported in the metatarsals. In contrast, the chondrodysplasia-like changes in Dmp1−/− mice occur in all endochondral bones and worsen with age. These results suggest that MMP9 is not responsible for the defects observed in Dmp1−/− mice.

Induction of apoptosis is spatially and temporally associated with the removal of the cartilage matrix. In vitro studies have shown that calcium, phosphate, and RGD-containing peptides found in several extracellular matrix proteins can act as powerful apoptogens (33, 34). Because DMP1 also contains an RGD sequence, this protein could function as an apoptogen. Results from the Dmp1−/− mice showing reduced apoptosis in hypertrophic chondrocytes and a severe defect in growth plate calcification support this hypothesis. We propose that reduced apoptosis in Dmp1−/− mice is partially due to poor mineralization of the cartilage matrix and possibly to DMP1 acting as an apoptogen for hypertrophic chondrocytes. This leads to an accumulation of hypertrophic chondrocytes, expanded growth plate, failure of coupling of chondrogenesis to osteogenesis, and therefore dwarfism.

We also examined changes in expression of markers for chondrocytes, such as type II collagen for chondrocyte differentiation and maturation and type X collagen for hypertrophic chondrocyte differentiation. No apparent differences in staining intensity for these ECM proteins were observed between Dmp1−/− mice and wild type mice. This suggests that the expanded and disorganized growth plate observed in these animals is not due to changes in chondrocyte differentiation.

Skeletal growth is also dependent on the lengthening of epiphyses at the proximal end of the long bone shaft. Development of epiphyses is different from the growth of the long bone shaft in the following ways: 1) the epiphyseal ossification center, also called the secondary ossification center, is formed after birth; 2) the epiphyses are composed primarily of spongy bone without a well defined bone marrow; and 3) the cartilage on the articular surface is retained without being replaced by bone. In this study, we provide evidence that Dmp1 is essential in the normal development of the secondary ossification center, because deletion of the Dmp1 gene leads to a delayed and malformed epiphyses followed by joint destruction. Blood vessel invasion of the epiphyses is delayed in the Dmp1−/− mice, but there is no evidence to show an intrinsic defect in angiogenesis itself in these animals.

In summary, our findings suggest multiple functions for DMP1 in postnatal skeletal development. A combination of increased proliferation of chondrocytes, impairment in chondrocyte programmed cell death, poor calcification of cartilage matrix, and a delay in blood vessel invasion appears to contribute to a chondrodysplasia-like defect in Dmp1−/− mice.

Acknowledgments

We thank Larry Fisher and Greg Lunstrum for providing polyclonal antibodies, David Anderson for providing CMVCre mice, and Drs. Stephen Harris, Lianping Xing, Jiwang Zhang, and Clarke Anderson for valuable discussions. Micro-CT data were collected at the HSS Core Center for Musculoskeletal Integrity, which was supported by Grant P30AR046121 from National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants DE13480, DE00455, and AR51587 (to J. Q. F.) and AR46798 (to L. F. B.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The abbreviations used are: OPN, osteopontin; WT, wild type; KO, knock-out; PECAM-1, platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kronenberg HM. Nature. 2003;423:332–336. doi: 10.1038/nature01657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Crombrugghe B, Lefebvre V, Nakashima K. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2001;13:721–727. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ducy P, Zhang R, Geoffroy V, Ridall AL, Karsenty G. Cell. 1997;89:747–754. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Komori T, Yagi H, Nomura S, Yamaguchi A, Sasaki K, Deguchi K, Shimizu Y, Bronson RT, Gao YH, Inada M, Sato M, Okamoto R, Kitamura Y, Yoshiki S, Kishimoto T. Cell. 1997;89:755–764. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80258-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ueta C, Iwamoto M, Kanatani N, Yoshida C, Liu Y, Enomoto-Iwamoto M, Ohmori T, Enomoto H, Nakata K, Takada K, Kurisu K, Komori T. J. Cell Biol. 2001;153:87–100. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeda S, Bonnamy JP, Owen MJ, Ducy P, Karsenty G. Genes Dev. 2001;15:467–481. doi: 10.1101/gad.845101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rimoin DL. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1996;63:106–110. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960503)63:1<106::AID-AJMG20>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisher LW, Torchia DA, Fohr B, Young MF, Fedarko NS. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;280:460–465. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fedarko NS, Fohr B, Robey PG, Young MF, Fisher LW. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:16666–16672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001123200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weber GF, Ashkar S, Glimcher MJ, Cantor H. Science. 1996;271:509–512. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5248.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Narayanan K, Srinivas R, Ramachandran A, Hao J, Quinn B, George A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:4516–4521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081075198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tartaix PH, Doulaverakis M, George A, Fisher LW, Butler WT, Qin C, Salih E, Tan M, Fujimoto Y, Spevak L, Boskey AL. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:18115–18120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314114200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D'Souza RN, Cavender A, Sunavala G, Alvarez J, Ohshima T, Kulkarni AB, MacDougall M. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1997;12:2040–2049. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.12.2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirst KL, Ibaraki-O'Connor K, Young MF, Dixon MJ. J. Dent. Res. 1997;76:754–760. doi: 10.1177/00220345970760030701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacDougall M, DuPont BR, Simmons D, Leach RJ. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 1996;74:189. doi: 10.1159/000134410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng JQ, Zhang J, Dallas SL, Lu Y, Chen S, Tan X, Owen M, Harris SE, MacDougall M. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2002;17:1822–1831. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.10.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng JQ, Huang H, Lu Y, Ye L, Xie Y, Tsutsui TW, Kunieda T, Castranio T, Scott G, Bonewald LB, Mishina Y. J. Dent. Res. 2003;82:776–780. doi: 10.1177/154405910308201003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ye L, MacDougall M, Zhang S, Xie Y, Zhang J, Li Z, Lu Y, Mishina Y, Feng JQ. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:19141–19148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400490200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sreenath T, Thyagarajan T, Hall B, Longenecker G, D'Souza R, Hong S, Wright JT, MacDougall M, Sauk J, Kulkarni AB. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:24874–24880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303908200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.George A, Sabsay B, Simonian PA, Veis A. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:12624–12630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruegsegger P, Koller B, Muller R. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1996;58:24–29. doi: 10.1007/BF02509542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao M, Harris SE, Horn D, Geng Z, Nishimura R, Mundy GR, Chen D. J. Cell Biol. 2002;157:1049–1060. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kiernan J. Histological and Histochemical Methods: Theory and Practice. 3rd Ed. Oxford University Press; Boston: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deleted in proof

- 25.Gerber HP, Ferrara N. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2000;10:223–228. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(00)00074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zelzer E, McLean W, Ng YS, Fukai N, Reginato AM, Lovejoy S, D'Amore PA, Olsen BR. Development. 2002;129:1893–1904. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albelda S, Oliver P, Romer L, Buck C. J. Cell Biol. 1990;110:1227–1237. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.4.1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerber HP, Vu TH, Ryan AM, Kowalski J, Werb Z, Ferrara N. Nat. Med. 1999;5:623–628. doi: 10.1038/9467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vu TH, Shipley JM, Bergers G, Berger JE, Helms JA, Hanahan D, Shapiro SD, Senior RM, Werb Z. Cell. 1998;93:411–422. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81169-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fedarko NS, Jain A, Karadag A, Fisher LW. FASEB J. 2004;18:734–736. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0966fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olson EN, Arnold HH, Rigby PW, Wold BJ. Cell. 1996;85:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arango NA, Lovell-Badge R, Behringer RR. Cell. 1999;99:409–419. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81527-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perlot RL, Jr., Shapiro IM, Mansfield K, Adams CS. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2002;17:66–76. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adams CS, Shapiro IM. Crit. Rev. Oral. Biol. Med. 2002;13:465–473. doi: 10.1177/154411130201300604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koller DL, Schriefer J, Sun Q, Shultz KL, Donahue LR, Rosen CJ, Foroud T, Beamer WG, Turner CH. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2003;18:1758–1765. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.10.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]