Abstract

T-box genes encode a large family of transcription factors that regulate many developmental processes in vertebrates and invertebrates. In addition to their roles in regulating embryonic heart and epidermal development in Drosophila, we provide evidence that the T-box transcription factors neuromancer1 (nmr1) and neuromancer2 (nmr2) play key roles in embryonic CNS development. We verify that nmr1 and nmr2 function in a partially redundant manner to regulate neuronal cell fate by inhibiting even-skipped (eve) expression in specific cells in the CNS. Consistent with their redundant function, nmr1 and nmr2 exhibit overlapping yet distinct protein expression profiles within the CNS. Of note, nmr2 transcript and protein are expressed in identical patterns of segment polarity stripes, defined sets of neuroblasts, many ganglion mother cells and discrete populations of neurons. However, while we observe nmr1 transcripts in segment polarity stripes and specific neural precursors in early stages of CNS development, we first detect Nmr1 protein in later stages of CNS development where it is restricted to discrete subsets of Nmr2-positive neurons. Expression studies identify nearly all Nmr1/2 co-expressing neurons as interneurons, while a single Eve-positive U/CQ motor neuron weakly co-expresses Nmr2. Lineage studies map a subset of Nmr1/2-positive neurons to neuroblast lineages 2-2, 6-1, and 6-2 while genetic studies reveal that nmr2 collaborates with nkx6 to regulate eve expression in the CNS. Thus, nmr1 and nmr2 appear to act together as members of the combinatorial code of transcription factors that govern neuronal subtype identity in the CNS.

Keywords: CNS development, T-box transcription factors, neuroblast lineage, Neuromancer1/2, Even-skipped

INTRODUCTION

T-box transcription factors play general and conserved roles to regulate the development of all metazoans. For example, T-box genes are known to regulate mesoderm formation, morphogenetic movements, cell adhesion, cell migration, tissue patterning, limb patterning, limb bud outgrowth, and organogenesis (King et al., 2006; Fong et al., 2005; Naiche et al., 2005; Showell et al., 2004; Chapman and Papaioannou, 1998; Papaioannou and Silver, 1998; Gibson-Brown et al., 1998). Moreover, an evolutionary conserved role for T-box genes to specify cell fates is supported by studies in simple organisms ranging from sponges, which contain several T-box genes (Larroux et al., 2006; Adell and Muller, 2005), to more complex invertebrate and vertebrate organisms, which can contain up to 21 T-box genes (Naiche et al., 2005; Woollard, 2005). In Drosophila melanogaster, eight T-box genes from four subfamilies have been identified; these include Dorsocross-1 (Doc1), Doc2, Doc3, optomotor blind (omb), optomotor-blind-related (org-1), brachyenteron (Byn), neuromancer1 (nmr1/H15), and neuromancer2 (nmr2/midline) (Reim and Frasch, 2005; Reim et al., 2005; Buescher et al., 2004; Griffin et al., 2000; Singer et al., 1996; Poeck et al., 1993). nmr1 and nmr2 are members of the Tbx20 gene family and regulate epidermal patterning as well as cardioblast specification in Drosophila (Buescher et al., 2006; Reim et al., 2005; Qian et al., 2005, Miskolczi-McCallum et al., 2005; Buescher et al., 2004).

Since mutations in T-box genes are associated with human congenital heart defects (Stennard et al., 2005; Takeuchi et al., 2005; Jerome and Papaioannou, 2001; Basson et al., 1999; Li et al., 1997), a majority of studies have focused on the role of Tbx20 and other T-box genes in regulating vertebrate embryonic heart development. In chick, zebrafish, and frog embryos, Tbx20 orthologues are expressed in developing cardiovascular structures and regulate the expression of Tbx5, a heart morphogenic gene important for the development of the early heart tube as well as chamber formation (Showell et al., 2006; Brown et al., 2005; Plageman and Yutzey, 2004; Szeto et al., 2002; Ahn et al., 2000). Morpholino oligonucleotide knockdown of Zebrafish Tbx20 (hrT) and frog Tbx20 results in small, malformed hearts and a loss of blood circulation (Brown et al., 2005; Szeto et al., 2002). Likewise, mouse Tbx20 mutants exhibit hypoplastic hearts with severe looping defects and abnormalities in cardiac chamber differentiation (Takeuchi et al., 2005; Stennard et al., 2005). Consistent with its fundamental role in cardiogenesis, mouse Tbx20 modulates the expression of Nkx2-5, Gata4 and Mef2c, members of the core cardiac transcription factor network, in the developing heart (Cai et al., 2005; Singh et al., 2005; Stennard et al., 2005; Takeuchi et al., 2005; Stennard et al., 2003).

The Drosophila Tbx-20 homologues, nmr1 and nmr2, have been shown to regulate two separable functions during cardiogenesis. Initially, nmr1 and nmr2 cooperate with the NK-2 class homeodomain transcription factor tinman and the GATA factor pannier to specify the fates of cardiac progenitor cells (Reim et al., 2005; Qian et al., 2005; Miskolczi-McCallum et al., 2005). In addition, nmr2 mutant embryos exhibit increased numbers of even-skipped-expressing cardiac progenitors at the expense of ladybird-expressing cardiac progenitors (Qian, et al., 2005). After specifying cardiac cell fates, nmr1 and nmr2 regulate the epithelial polarity of myocardial cells as repression of nmr1 and nmr2 results in the mislocalization of the junctional proteins Discs-large, Dystroglycan, and alpha-Spectrin (Qian et al., 2005). These molecular defects likely lead to the disorganization of the heart tube and misalignment of heart cells consistent with defects in cell adhesion (Fong et al., 2005).

While much research has focused on the function of Tbx20 genes in heart development, a few studies have indicated a likely function for this gene family during CNS development. For example, Tbx20 genes are expressed in cranial motor neurons in zebrafish, mice, and C. intestinalis and in dorsal motor neurons in the chick spinal cord (Nordstrom et al., 2006; Song et al., 2006; Dufour et al., 2006; Ahn et al., 2000). Moreover, mab-9, the C. elegans Tbx20 family member, is expressed in neurons located in specific regions of the ventral nerve cord (Woollard and Hodgkin, 2000). Drosophila nmr1 and nmr2 transcripts are also detected in the mature embryonic CNS (Qian et al., 2005) and loss of nmr1 and nmr2 results in an increase in Eve-expressing neurons (this study; Buescher et al., 2006).

In Drosophila nmr1 and nmr2 negatively regulate Wingless signaling in the ventral epidermis to establish proper segmentation (Buescher et al., 2004). In early stages of CNS development, nmr2 promotes the formation and specification of several neuroblasts in the CNS (Buescher et al., 2006). However, the roles of nmr1 and nmr2 in regulating later steps of CNS development in Drosophila remain largely unexplored. Through a forward genetic screen we identified nmr1 and nmr2 as regulators of neuronal subtype identity in the Drosophila CNS. nmr1 and nmr2 function in a partially redundant manner to regulate neuronal specification and in agreement with this, are expressed in overlapping patterns of CNS neurons. Nmr1 and Nmr2 expression appear predominantly confined to interneurons, and lineage tracing studies map subsets of Nmr1-positive neurons to three specific neuroblast lineages. Taken together, these data suggest that nmr1 and nmr2 are additional members of the transcriptional regulatory network that specifies neuronal fates in the Drosophila embryonic CNS, and that elucidating their function will further our understanding of the mechanisms guiding CNS development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly stocks

Drosophila melanogaster strains were maintained at 25°C on cornmeal-yeast-agar media. white[1] flies were used as wild-type. We used the following lines in the study: Df(2L)sc19-4 (Bloomington Stock Center), Df(2L)x528 (Buescher et al., 2006; Buescher et al., 2004), nmr1210 (Qian et al., 2005), midGA174 (Seeger et al., 1993), mid2 (Nusslein-Vohard et al., 1984), eveID19 (Nusslein-Volhard et al., 1985), hb9kk30 (Broihier and Skeath, 2002), nkx6D25 (Broihier et al., 2004), and PZ[lac-Z;ry+]H15 ((H15-lacZ); Brook and Cohen (1996)). We generated the double-mutant lines nmr1210;hb9kk30, nmr1210;nkx6D25, midGA174;hb9kk30 (nmr2;hb9), and midGA174;nkx6D25 (nmr2;nkx6). We used the Gal4/UAS system (Brand and Perrimon, 1993) and Elav-Gal4 (Lin and Goodman, 1994) to misexpress the following transgenes in wild-type and specific mutant backgrounds: UAS-nmr1, UAS-nmr2 (Qian et al., 2005) and UAS-eve (Landgraf et al., 1999). Due to the observed post-transcriptional regulation of nmr1 in embryos, we verified that ElavGAL4::UAS-nmr1 drove generalized Nmr1 protein expression in the CNS via standard immunochemical methods. Embryos used for the lineage analyses were of the following genotype: y w hsFlp/+; UAS-tau-myc-GFP/+; flpout-Gal4/+.

Antibody production, immunofluorescent, and immunohistochemical studies

Amino acids 1-287 of Nmr1 (N-terminal) and 322-557 of Nmr2 (C-terminal) were cloned into pET (Novagen) for protein expression and purification. These protein fragments were used as immunogens to generate antibody responses specific to Nmr1 in rabbits and guinea pigs and to Nmr2 in rabbits at Pocono Rabbit Farm and Laboratory. Both Nmr1 and Nmr2 antibodies are specific as demonstrated by their inability to detect the expression of any other proteins in Drosophila homozygous mutant for null alleles of nmr1 and nmr2, respectively. We used the Vector ABC kit for immunocytochemical staining and Alexa 488, Alexa 594, and Alexa 633 with appropriate species specificity for immunofluorescence studies (Molecular Probes). We followed standard protocols published by N.H. Patel (1994) for both immunocytochemical and immunofluorescent staining.

We used the following primary antibodies at the indicated dilutions for this study: rabbit anti-Eve (1:3000; Frasch et al., 1987), mouse anti-Repo (1:100; Halter et al., 1995), rat anti-Nkx6 (1:1000; Broihier et al., 2004), guinea pig anti-Hb9 (1:1000; Broihier and Skeath, 2002), mouse anti-Zfh-1 (1:1000; Lai et al., 1993), rabbit anti-Mef2 (1:3000; Lilly et al., 1995), rabbit anti-Gad (1:1000; a gift of F.R. Jackson; Kulkarni et al., 1994), rabbit anti-Serotonin (1:300; a gift of P. Taghert; Taghert and Goodman, 1988), rabbit anti-DVGLUT (1:10,000; a gift of A. DiAntonio; Daniels et al., 2004), rabbit anti-Dbx (1:1000; J. Skeath), guinea pig or rabbit anti-Nmr1 (1:3000; this work), and rabbit anti-Nmr2 (1:1000; this work). The following primary antibodies were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank at The University of Iowa: anti-Dac2-3 (1:10, Mardon et al., 1994), anti-Fasciclin II (1D4, 1:5; Grenningloh et al., 1991), anti-Engrailed/Invected (4D9, 1:10; Patel et al., 1989), and BP-102 anti-Neurotactin (1:20; Hortsch et al., 1990). Rabbit (Jackson Laboratories) and mouse (Promega) β-Galactosidase antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:2000. Rabbit GFP antibody (Torey Pines) was used at a 1:3000 dilution. All secondary antibodies for immunocytochemical staining were diluted at 1:300 (Vector Laboratories).

RNA in situ hybridization

In situ hybridization of Drosophila embryos was performed essentially as described in Tautz and Pfeiffle (1989). To detect nmr1 RNA expression we generated two anti-sense digoxygenin RNA probes specific for nmr1 using the T7 Megascript transcription kit (Ambion). One region corresponded to exons 1 and 2 of nmr1 (798 bases). This region almost completely overlaps with the fragment of nmr1 used to generate recombinant Nmr1 protein for antibody generation, which includes exons 1 and 2 and the first 63 bases of exon 3. The other RNA probe was generated from the full-length nmr1 cDNA (Qian et al., 2005). Both probes detect identical nmr1 RNA expression patterns in embryos.

Deficiency screening and deficiency mapping

We screened 200 deficiency lines contained within the second and third chromosomal deficiency kits available from the Bloomington Stock Center (IN) for alterations in the CNS expression pattern of Eve. Embryos homozygous for Df(2L)sc19-4 (25D7;26A9) exhibited ectopic Eve-positive neurons. We then used the following deficiencies to map this Eve CNS phenotype to a smaller genomic interval: Df(2L)tkv2 (25D2;25E1), Df(2L)Exel6012 (25D5;25E6), Df(2L)cl2 (25D2;25F2), Df(2L)cl-h2 (25D6;25F5), and Df(2L)cl-h4 (25E1;25E5). The latter deficiency was the most useful for narrowing the genomic interval of interest to 25E1;25E5 within which 16 predicted or known genes reside. We obtained mutant alleles available for 6 of these genes and screened embryos homozygous for each of these mutations for alterations in the Eve CNS expression. Only the neuromancer2 (midline) mutant alleles, midGA174 and mid2, recapitulated the Df(2L)sc19-4 Eve mutant phenotype.

Lineage tracing analyses

We used a modified Flp/FRT (Flipase/Flp Recognition Target) system developed by Harrison and Perrimon (1993) to map the neuroblast lineage and trace axon projection patterns of neurons that express Nmr1. We collected 0–2 hr old embryos and aged them for 2, 4, and 6 hrs at 25°C. Each group of developmentally staged embryos was collected and heat-shocked for seven minutes at 33°C to induce flp recombinase, placed at 18°C, and aged until stage 15–17. Embryos were then collected, fixed, and triple-stained with anti-Nmr1, anti-GFP, and anti-Fas II. By varying the time of the Flp expression, we GFP-labeled the whole neuroblast lineage or individual Nmr1-positive neurons. Anti-Fas II labeled the axon connectives. Using confocal microscopy, we obtained approximately 50–60 0.1 μm thick Z-series of each nerve cord containing positive clones and compressed those images into two dimensions using Leica software.

Software programs

The final confocal images were assembled using Adobe Photoshop software. Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel and the data were presented graphically using Origin software (Microcal Software, Inc.).

RESULTS

nmr2 and nmr1 are neuronal fate determinants

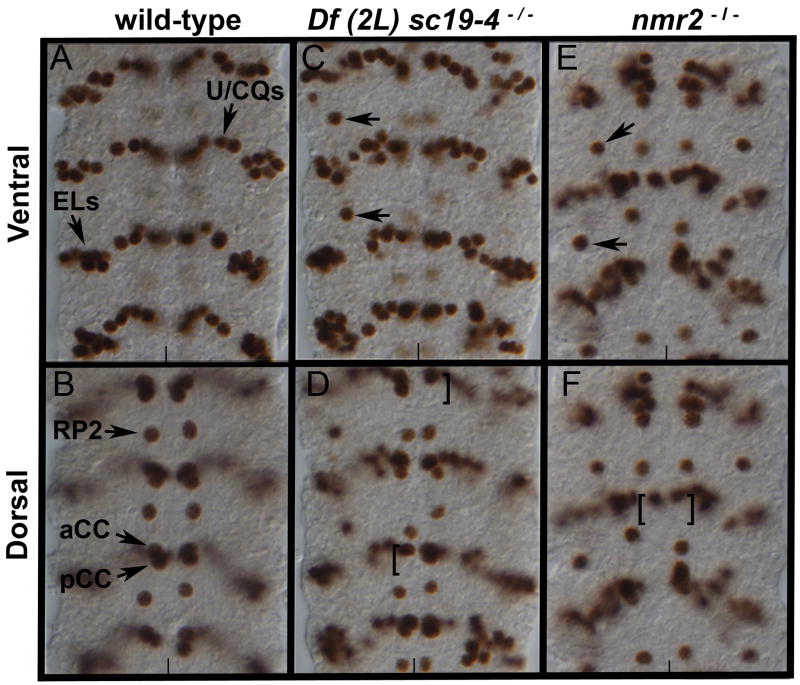

To identify genes that regulate neuronal cell fate in the Drosophila embryonic CNS, we screened a collection of approximately 200 second and third chromosomal deficiency lines for changes in the CNS expression pattern of even-skipped (eve). We chose eve as a molecular marker because eve regulates neuronal cell fates (Doe et al., 1988) and is expressed in a stereotyped pattern of neurons in the CNS (Fig. 1A,B). We focused our attention on Df(2L)sc19-4 (25D7;26A9) because embryos homozygous for this deficiency exhibit ectopic Eve-positive neurons in the lateral region of the CNS (Fig. 1C) as well as a partial loss of medial Eve-positive aCC/pCC neurons (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

nmr2 represses eve expression in the Drosophila nerve cord.

Stage 15 wild-type (A,B), Df(2L)sc19-4−/− (C,D), and nmr2−/− (E,F) mutant nerve cords stained for Eve. (A,B) In wild-type nerve cords Eve labels 5–6 U/CQ, 10 EL, RP2, and aCC/pCC neurons as indicated. (C) In Df(2L)sc19-4−/− mutant embryos, ectopic Eve-positive neurons arise laterally (arrows) and (D) there is a decrease in the presence of Eve-positive aCC/pCC neurons (brackets). (E,F) nmr2−/− mutant embryos (midGA174) exhibit the same phenotype as that observed in Df(2L)sc19-4−/− embryos. Panels A, C, E – ventral views and panels B, D, F – dorsal views of the Drosophila nerve cord; the vertical line marks the midline.

We used deficiency mapping to localize this genetic function to a smaller interval and identified the T-box genes neuromancer1 (nmr1) and neuromancer2 (nmr2) as likely candidates to regulate eve expression in the CNS (see Methods). Since nmr1 and nmr2 are known to regulate heart and epidermal development in the Drosophila embryo and both are expressed in the CNS (Qian et al., 2005; Buescher et al., 2004), we asked whether loss of function in nmr1 and/or nmr2 yielded a phenotype similar to that observed for Df(2L)sc19-4. Embryos homozygous for a null allele of nmr2 (midGA174) display an Eve CNS phenotype similar to but weaker than that observed for embryos homozygous for Df(2L)sc19-4 (Fig. 1), whereas embryos homozygous for a null allele of nmr1 (nmr1210) exhibit a wild-type Eve expression pattern (data not shown). Thus, nmr2, but not nmr1, is necessary to regulate eve expression in the CNS.

Prior work has shown that nmr1 and nmr2 function in a partially redundant manner to control epidermal development in the Drosophila embryo with nmr2 playing a primary role in this process (Buescher et al., 2004). To test whether nmr1 collaborates with nmr2 to regulate eve expression and to rule out the possibility that other genes uncovered by the deficiency contribute to the mutant phenotype, we removed both copies of nmr1 and nmr2 by generating embryos trans-heterozygous for the original deficiency, Df(2L)sc19-4, and a different deficiency, Df(2L)x528. The region of overlap between these deficiencies specifically removes nmr1, nmr2, and an annotated gene, CG31647, with unknown function (Buescher et al., 2004). Embryos trans-heterozygous for these two deficiencies yielded a phenotype identical to that observed for embryos homozygous for Df(2L)sc19-4 (Buescher et al., 2004; data not shown). Thus, we conclude that nmr1 and nmr2 function in a partially redundant manner to control eve expression within the CNS.

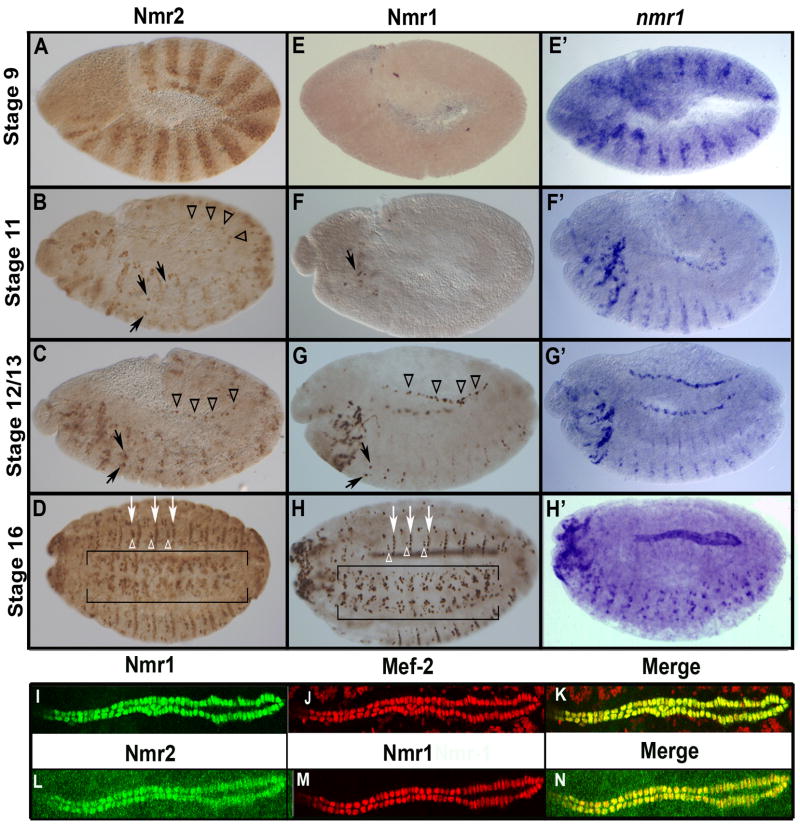

Nmr2 and Nmr1 protein expression during embryogenesis

In order to identify the individual cells that express nmr1 and/or nmr2, and to follow the expression dynamics of these two factors during embryogenesis and neurogenesis we generated Nmr1 and Nmr2 specific antibodies (see Methods). In general, we find that Nmr2 is expressed earlier and more broadly than Nmr1, with Nmr1 expression being restricted to subsets of Nmr2-expressing cells. We also find evidence for temporal regulation of Nmr1 protein translation as we observe nmr1 transcripts in segment polarity stripes during gastrulation (Buescher et al., 2006; Fig. 2), many hours before Nmr1 protein becomes detectable in a few cells in the CNS (Fig. 2). In contrast, the RNA and protein expression profiles of Nmr2 appear essentially identical (Buescher et al., 2006).

Figure 2.

Nmr1 and Nmr2 protein expression during embryogenesis.

Nmr2 (A–D,L), Nmr1 (E–H,I) and nmr1 mRNA transcript (E′–H′) expression in wild-type embryos at progressively later stages of development (A) Stage 9 embryos express Nmr2 in segment polarity stripes. (B) During early stage 12, Nmr2 is expressed in subsets of neuroblasts and their progeny in the CNS (arrows) as well as in heart precursor cells in the dorsal mesoderm (arrowheads). (C) During late stage 12, Nmr2 is expressed prominently in a medial pair of CNS neurons in each segment (arrows) and is also expressed in heart precursor cells (arrowheads). (D) By stage 16 Nmr2 is expressed in many neurons in the CNS (brackets), narrower transverse stripes of ectodermal cells (white arrows), and clusters of ectodermal cells (white arrowheads) between these stripes. (E) Stage 9 embryos do not express Nmr1 protein while (E′) nmr1 transcripts are clearly detected in segment polarity stripes. (F) Nmr1 protein is first detected during early stage 12 in a few cells in the cephalic region (arrow), (F′) while similarly staged embryos express nmr1 transcripts in segment polarity stripes, neuronal precursors and neurons. (G, G′) By stage 13, Nmr1 protein and RNA are expressed in identical patterns of CNS neurons (arrows) and heart precursors in the mesoderm (arrowheads). (H, H′) By stage 16, Nmr1 protein and RNA are co-expressed in many neurons in the CNS (H, brackets), all cardioblasts as well as in narrow stripes of ectodermal cells (H, white arrows). (I–N) High magnification views of the Drosophila heart at stage 16 show that Nmr1 (I, green; M, red) and Nmr2 (L, green) are co-expressed with Mef-2 (J, red) in all cardioblasts (K,N). Whole mounts in the lateral orientation; Anterior, left; Posterior, right; Dorsal, up; Ventral, down.

We first detect Nmr2 expression during gastrulation (stage 6/7). At this time and through stage 10 Nmr2 is expressed in segment polarity stripes consistent with its known role in repressing wingless expression during segmentation (Fig. 2A) (Buescher et al., 2006; Buescher et al., 2004). During the remainder of embryogenesis Nmr2 is expressed in a dynamic pattern in many tissues (Fig. 2B–D). In the CNS, Nmr2 is expressed in subsets of neuroblasts, ganglion mother cells, and neurons and by the end of embryogenesis marks about twenty neurons per hemisegment. In the ectoderm, Nmr2 expression remains in the ventral region of the embryo and is lost most dorsally. By the end of embryogenesis Nmr2 is expressed in ventral stripes of ectodermal cells (white arrows, Fig. 2D) and small clusters of ectodermal cells between these stripes (white arrowheads, Fig. 2D). In the mesoderm, Nmr2 expression is restricted to the heart where Nmr2 is expressed in all cardioblasts as well as their precursors (Fig. 2B,C,H–M).

In contrast to Nmr2, we first detect Nmr1 protein during stage 12 in a few cells in the anterior portion of the CNS (Fig. 2F,G). From this stage forward, the expression pattern of Nmr1 largely parallels that of Nmr2 in the CNS, ectoderm and mesoderm; the only exception being that only a subset of Nmr2-positive neuronal and ectodermal cells express Nmr1 (Fig. 2G and Fig. 3I). The protein expression profile of Nmr1 is noteworthy for two reasons. One, comparisons of the Nmr1 protein and RNA expression patterns indicate that nmr1 transcript is subject to post-transcriptional regulation during early but not late embryogenesis. For example, while nmr1 RNA is expressed from stage 7 to stage 12 in a pattern very similar to that observed for nmr2 (Buescher et al., 2006; Fig. 2E′–H′), Nmr1 protein first appears during late stage 12 in a few cells in the CNS. From late stage 12 forward the Nmr1 protein and RNA patterns appear essentially identical (Fig. 2F–G and F′–G′).

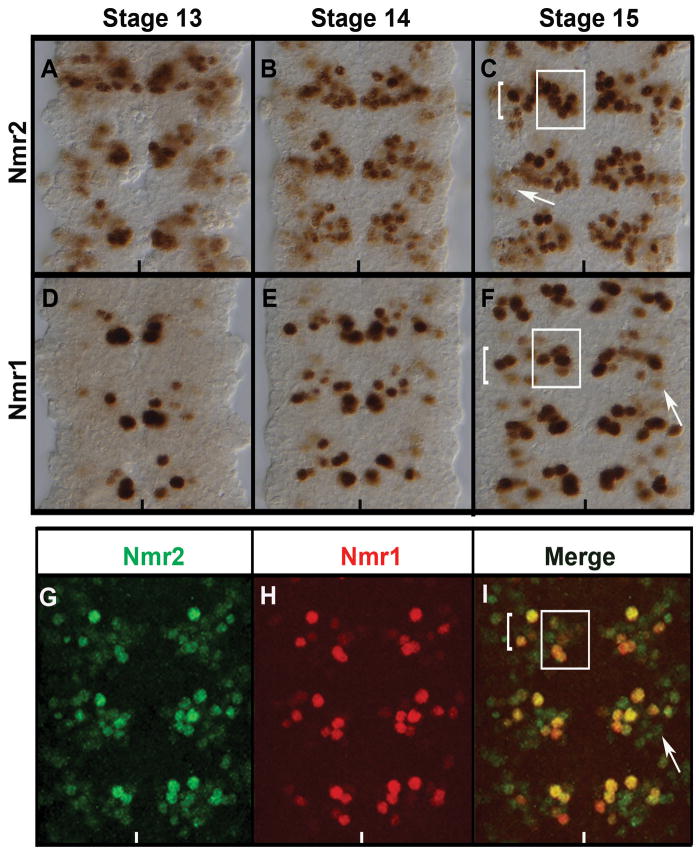

Figure 3.

Co-expression of Nmr2 and Nmr1 in the Drosophila CNS.

Stage 13 (A,D,) stage 14 (B,E), and late stage 15 (C,F,G–I) wild-type embryos labeled for Nmr2 (A–C, G, I), Nmr1 (D–F, H, I) and co-labeled for Nmr1 and Nmr2 (I). (A) During stage 13 Nmr2 is expressed strongly in a cluster of medial neurons and weakly in a group of lateral neurons. (B) By stage 14, Nmr2 is expressed strongly in a cluster of approximately 10–15 cells per hemisegment with enhanced expression in the medial and intermediate regions of the nerve cord and diminished expression laterally. (C) This pattern of expression is prominently defined in stage 15 where Nmr2 is expressed strongly in a cluster of approximately 8 medial neurons (box) and 8 lateral neurons (bracket). Nmr2 is also expressed weakly in about 5–6 neurons within the lateral cluster (arrow). (D) During stage 13 Nmr1 is expressed strongly in a small number of medial neurons and expressed weakly in a few neurons in the intermediate region. (E) By stage 14, Nmr1 expression remains high in medial neurons and expression is now observed in additional neurons in the intermediate regions of the CNS. (F) By stage 15, Nmr1 is expressed in many discrete sets of neurons in the CNS: a medial cluster of approximately 3–5 neurons (box), a lateral cluster of 7–8 neurons (bracket), and a few dispersed lateral neurons (arrow). (G–I) Double-labeling for Nmr2 (green) and Nmr1 (red) in stage 15 embryos indicates that a subset of Nmr2-positive neurons express Nmr1 (merge).

Two, we find that the protein expression profile of Nmr1 is not identical to that driven by the H15-lacZ enhancer trap line, which is inserted roughly 3 Kb upstream of nmr1, and has been used as a surrogate for Nmr1 protein expression in embryos (Buescher et al., 2006; Miskolczi-McCallum et al., 2005; Buescher et al., 2004). For example, during late stages of CNS development (stages 13–16) double-label studies indicate that while H15-lacZ labels all Nmr1-positive neurons, many H15-lacZ-positive cells do not express Nmr1 protein (Fig. S1). During earlier stages of development the two patterns do not overlap as H15-lacZ drives expression in segment polarity stripes, many NBs, and ganglion mothers cells, but as noted Nmr1 protein first becomes detectable during stage 12 in a few post-mitotic neurons. The early pattern of H15-lacZ does appear essentially identical to the Nmr2 protein expression profile. However, while more neurons co-express H15-lacZ and Nmr2 than H15-lacZ and Nmr1 during late stages of CNS development, many cells especially those near the midline still express H15-lacZ but not Nmr2 (Fig. S1). Thus, the H15-lacZ expression pattern, likely due to perdurance of β-galactosidase within neuroblasts and neuroblast lineages that transiently express nmr1/2, appears to over-estimate the protein expression profiles of Nmr1 and Nmr2 in the mature embryonic CNS (see also below).

Nmr2 and Nmr1 expression in discrete neuronal populations of the CNS

We explored the CNS expression profiles of Nmr1 and Nmr2 in greater detail to gain insight into their possible functions during CNS development. The expression patterns of Nmr2 and Nmr1 are dynamic and complex in the CNS with a number of distinguishing. Nmr2 and Nmr1 are expressed in several discrete clusters of neurons in the CNS per hemisegment. A subset of cells within each cluster of Nmr2-positive neurons expresses Nmr1, and the expression of Nmr1 is delayed relative to that of Nmr2 in these cells. While distinct clusters of neurons reproducibly express Nmr1/Nmr2 at different levels, the relative expression levels of Nmr2 and Nmr1 within any one cluster are similar. The extensive co-expression of Nmr1/2 in the CNS helps explain the partially redundant function of these genes. Moreover, the temporal delay of nmr1 expression relative to that of nmr2 in neurons together with the restriction of nmr1 expression to a subset of nmr2-positive neurons suggests the existence of a positive regulatory relationship between nmr2 and nmr1.

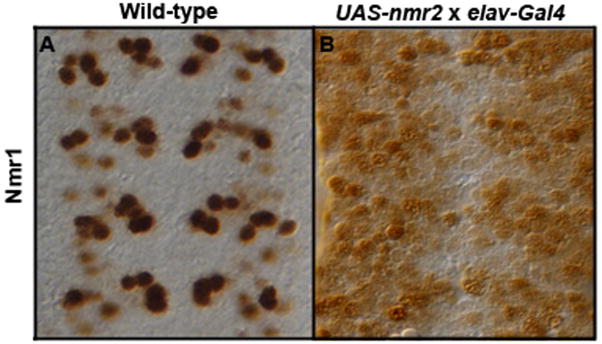

To test for a regulatory relationship between nmr2 and nmr1 we followed Nmr1 protein expression in embryos that express Nmr2 in all CNS neurons as well as in embryos that lack nmr2 function. First, we used the Gal4/UAS system and the Elav-Gal4 driver line to express nmr2 ectopically in all CNS neurons. This manipulation led to ectopic nmr1 expression in most, if not all, cells in the CNS (Fig. 4) suggesting that nmr2 can positively regulate nmr1 expression in many neurons. However, the pattern and levels of nmr1 remain essentially normal in embryos homozygous mutant for nmr2 (data not shown). The pattern of nmr2 expression remains unchanged in embryos that lack nmr1 function as well as in those in which nmr1 is expressed throughout the CNS using the Gal4/UAS system (methods; data not shown). These results underscore the complex regulatory relationship between nmr2 and nmr1 in the CNS as nmr2 appears sufficient to activate nmr1 in most neurons but is not necessary to promote nmr1 expression in any neurons. Thus, other factors must act in parallel to nmr2 to activate or to maintain nmr1 expression in neurons that co-express nmr1 and nmr2, while distinct factors likely repress nmr1 in cells that only express nmr2.

Figure 4.

Nmr2 enhances Nmr1 expression.

Stage 15 embryonic nerve cords stained for Nmr1. (A) Wild-type expression pattern of Nmr1 in the ventral nerve cord. (B) Misexpression of Nmr2 in all post-mitotic neurons (ElavGAL4::UAS-nmr2) significantly enhances Nmr1 expression throughout the nerve cord.

Nmr1 and Nmr2 mark a unique population of interneurons

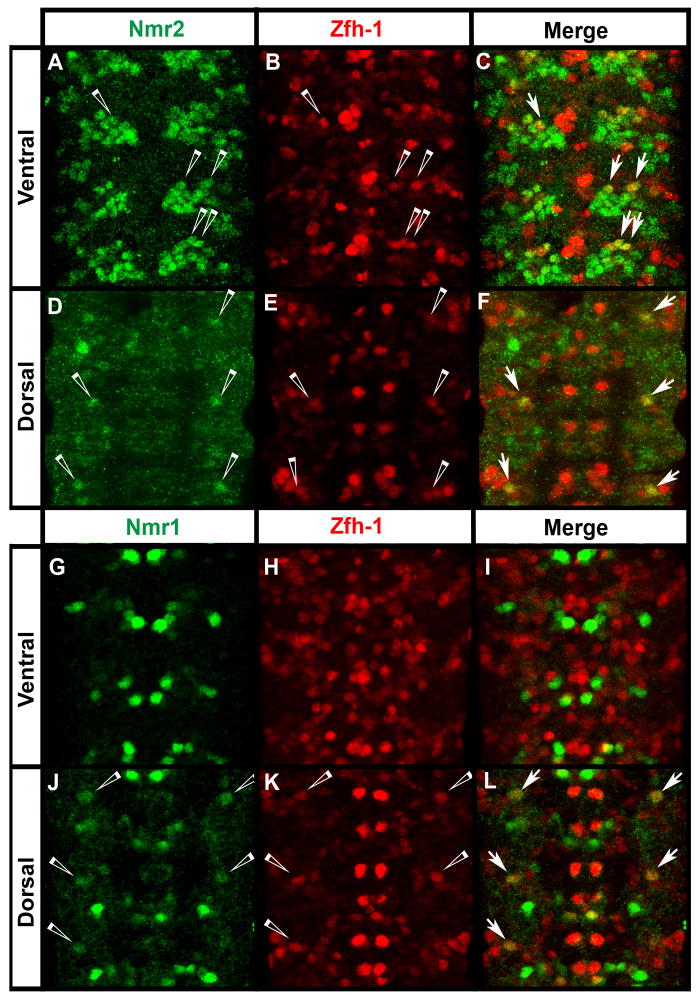

Next, we sought to determine the specific subtype of cells that express nmr1 and nmr2 in the CNS. We first tested whether glia and/or motor neurons express nmr1 and nmr2 by looking for co-expression between Nmr1/Nmr2 and molecular markers of the glial (Repo) or motor neuron fate (Eve, Hb9, Zfh-1) (Layden et al., 2006; Lundell et al., 2003; Novotny et al., 2002; Isshiki et al., 2001; Skeath and Doe, 1998). Repo and Nmr1/Nmr2 label largely complementary sets of cells in the CNS with no co-expression observed between Repo and Nmr1 and only one lateral glial cell expressing Nmr2 (Fig. S2). Similarly, Nmr1/Nmr2 exhibit minimal co-expression with Eve and Hb9 (Fig. 9H,I; data not shown for Hb9), which together label most motor neurons (Broihier and Skeath, 2002; Schmid et al., 1999; Landgraf et al., 1997; Sink and Whitington, 1991). No Hb9-positive neurons express Nmr1 or Nmr2, while only one Eve-positive U/CQ neuron weakly expresses Nmr2 (Fig. 9H). Zfh-1 is expressed in most motor neurons and some interneurons in abdominal segments (Skeath and Doe, 1998; Layden et al., 2006). Three Zfh-1 and Nmr2 co-expressing neurons are located ventrally within each hemisegment (Fig. 5A–C) and one dorsal Zfh-1 neuron co-expresses Nmr2 and Nmr1 within each hemisegment (Fig. 5D–F and Fig. 5J–L). Since the vast majority of Zfh-1-positive neurons do not co-express Nmr2 or Nmr1, these analyses indicate that most nmr1 and nmr2-expressing cells in the CNS are interneurons.

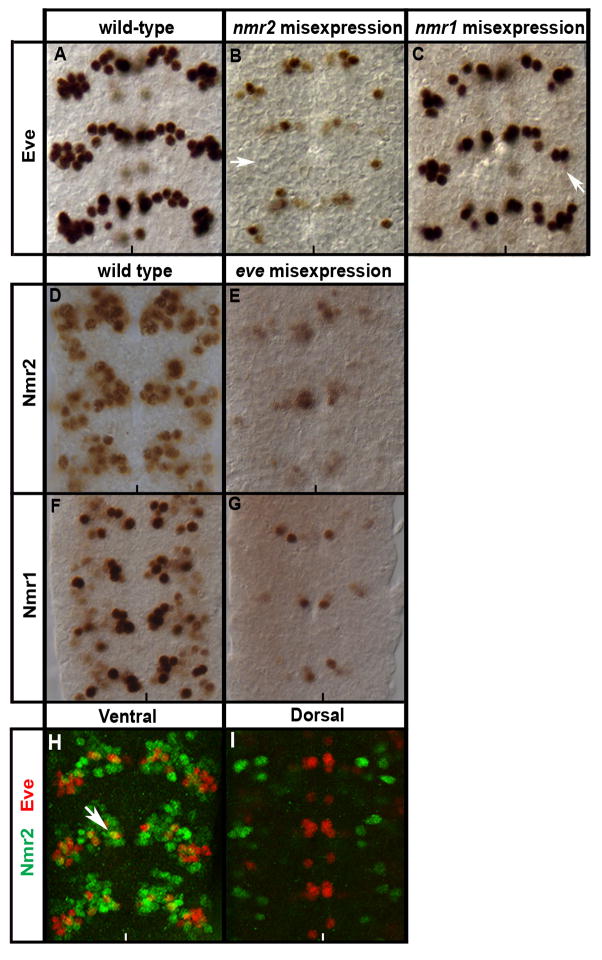

Figure 9.

Nmr1 and Nmr2 repress Eve expression.

Wild-type stage 15 embryonic nerve cords stained for Eve (A–C, H,I), Nmr2 (D,E,H,I), and Nmr1 (F,G). (A) Wild-type expression pattern of Eve within the ventral region of the CNS. (B) Misexpression of Nmr2 in all post-mitotic neurons (ElavGAL4::UAS-nmr2) significantly reduces Eve expression in all Eve-positive neurons (arrow points to location of ELs). (C) Misexpression of Nmr1 throughout the CNS (ElavGAL4::UAS-nmr1) causes a mild decrease of Eve expression (arrow points to ELs). (D,F) Wild-type expression pattern of Nmr2 (D) and Nmr1 (F). (E,G) Expression of Eve throughout the CNS (ElavGAL4::UAS-eve) results in a significant decrease of Nmr2 (E) and Nmr1 (G). (H,I) Eve (red) exhibits a predominantly mutually exclusive expression pattern with Nmr2 (green) in the ventral (H) and dorsal (I) regions of the nerve cord while a single Eve-positive U/CQ neuron (H) co-expresses Nmr2 (arrows).

Figure 5.

Nmr1 and Nmr2 are detected in a few Zfh-1-expressing motor neurons.

(A–L) Wild-type stage 15 embryos stained for Zfh-1 (red) and Nmr2 (green) or Nmr1 (green). (A–C) In the ventral region of the CNS, Nmr2-positive and Zfh-1-positive neurons are co-expressed in approximately 2–3 neurons in the medial Nmr2-expressing cluster per hemisegment (merge, arrows). (D–F) Dorsally in the CNS, a single lateral neuron co-expresses Nmr2 and Zfh-1 per hemisegment (merge, arrows). (G–I) In the ventral region of the CNS, no cells co-express Nmr1 (green) and Zfh-1 (red). (J–L) In the dorsal region of the CNS, one lateral neuron weakly co-expresses Nmr1 and Zfh-1 per hemisegment (merge, arrows).

To determine if Nmr1/Nmr2-positive neurons identify any well-characterized interneurons, we carried out additional double-labeling studies and assayed for co-expression between Nmr1/Nmr2 and Dachshund (Miguel-Aliaga et al., 2004), Engrailed (Bossing and Brand, 2006), or Apterous (Lundgren et al., 1995), each of which labels discrete sets of interneurons. We find that Nmr1 and Nmr2 are expressed in mutually exclusive sets of interneurons relative to each of these markers. Thus, Nmr1 and Nmr2 identify subsets of interneurons largely distinct from those that have previously been characterized.

Our results contrast with prior work on Nmr1/Nmr2, which indicated that these factors are expressed in the Engrailed-positive ventral and dorsal channel glia as well as in the Engrailed-expressing progeny of the midline neuroblast (Buescher et al., 2006). However, we do not observe expression of Nmr1 or Nmr2 in any Engrailed expressing neurons/glia in the CNS (Fig. S3). Thus, H15-lacZ expression in these cells likely arises due to earlier transient expression of nmr1/nmr2 within neuroblast 7-4, the progenitor of the channel glia, and the median neuroblast (Buescher et al. 2006). Consistent with nmr2 acting during early steps of CNS development to regulate the development and differentiation of cells in these two lineages, we confirmed that loss of nmr2 function leads to the disorganization and occasional loss of the channel glia as well as the Engrailed-positive progeny of the midline neuroblast, as observed previously by Buescher et al. (2006).

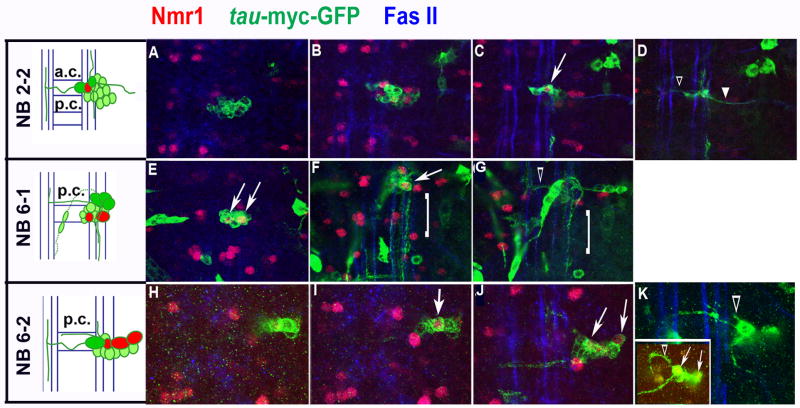

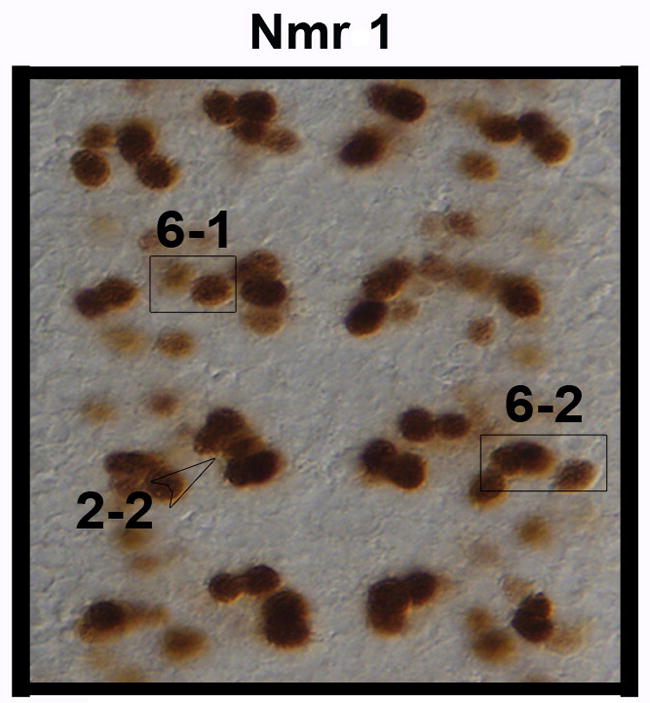

Nmr1 and Nmr2 are expressed within interneurons derived from NB lineages 2-2, 6-1, and 6-2

We used lineage tracing to begin to map the neuroblast lineages that give rise to Nmr1-positive neurons. This technique also allowed us to visualize the axon trajectories of Nmr1-positive neurons. Since we demonstrate that Nmr2 labels all Nmr1-positive neurons (Fig. 3I), we are essentially mapping the neuroblast lineages giving rise to subsets of Nmr1 and Nmr2 co-expressing neurons. Briefly, we used a modified version of the FLP/FRT lineage tracing system (Harrison and Perrimon, 1993; see Methods) to create random clones of tau-myc-GFP reporter gene expression. We screened lineage clones within the embryonic CNS for those that contained at least one Nmr1-positive neuron, and then identified the parental neuroblast of Nmr1-positive neurons by comparing the location and morphology of our lineage clones to the location and morphology of identified neuroblast lineages as determined by Dil-labeling (Schmid et al., 1999; Schimdt et al., 1997; Bossing et al., 1996). Through this approach we identified the parental neuroblast lineage for three sets of Nmr1-positive neurons (6 neurons) via the analysis of multiple independent clones for each set of neurons (summarized in Fig. 7). For example, two clones in abdominal segments contained the same medially-positioned Nmr1-positive neuron (Fig. 6C). This interneuron resides within a large clone of approximately 12–15 interneurons and 1 motor neuron (Fig. 6A–D). The interneurons project axons across the anterior commissure and then project axons anteriorly and posteriorly along the medial and lateral Fas-II-positive longitudinal fascicles (Fig. 6D). The motor neuron projects its axon out the segmental nerve (Fig. 6D). The morphology of these clones together with their relative location in a segment most closely match those identified for NB 2-2 by DiI labeling studies (Schmid et al., 1999). Thus, we place this medial Nmr1-positive neuron within the 2-2 lineage (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Expression pattern of Nmr1-positive neurons derived from NBs 2-2, 6-1 and and 6-2.

The boxed sets of neurons highlight the Nmr1-positive neurons derived from NB lineages 6-1 (left) and 6-2 (right). An open arrowhead points to the Nmr1-positive neuron derived from the NB 2-2 lineage.

Figure 6.

A subset of Nmr1/−2 expressing interneurons derived from neuroblast lineages 2-2, 6-1, and 6-2.

Cartoons detail the positions and axon morphologies of Nmr1-positive interneurons (red) within identified NB clones in the CNS of wild-type, stage 15–17 embryos. The most ventral neurons are shaded dark green. Neurons are drawn in relation to the anterior and posterior commissures (AC/PC) and the longitudinal connectives (blue). From top (dorsal) to bottom (ventral) the compressed confocal images represent ~1 μM thick sections of Nmr1-positive clones. The nerve cord is triple-labeled for Nmr1 (red), axons (green, anti-GFP), and longitudinal connectives (blue, anti-FasII). (A–D) A lineage clone that contains one Nmr1-positive neuron (arrow) extends axons contralaterally (D, open arrowhead) and a motor neuron axon branch (D, closed arrowhead). (E–G) A lineage clone that contains two Nmr1-positive interneurons (white arrows) extends a collateral axon branch (G, open arrowheads) and a cascade of ipsilateral axons (F,G, brackets). (H–K) A lineage clone that contains three Nmr1-positive neurons (arrows) extends a small ipsilateral axon branch (J, open arrowhead) as well as anterior and posterior collateral axons. Occasionally, NB 6-2 clones exhibit an ipsilateral axon branch with a prominent arch and this axonal phenotype was detected in a similar clone (K, inset).

We used similar criteria to place two other sets of Nmr1-positive neurons in defined lineages. We identified two clones in abdominal segments comprised of ~10 interneurons that contain both a medial and intermediate positioned Nmr1-positive neuron (Fig. 6E,F). The most striking feature of these clones is the cascade of ipsilateral axon branches that extend posteriorly and span at least one segment (Fig. 6F,G). The ventral region of these clones contains two to three large interneurons that project axons across the posterior commissure and then turn anteriorly (Fig. 6G). These morphological features most closely match those defined by DiL labeling for the 6-1 lineage. Thus, two specific Nmr1-positive neurons are derived from this lineage (Fig. 7) (Schmid et al., 1999; Bossing et al., 1996).

Finally we identified four clones each of which labeled the same three Nmr1-positive neurons in abdominal segments. These neurons are located in abdominal segments and their clones contain 12–18 interneurons (Fig. 6H–K) that extend two contralateral axon bundles across the posterior commissure and a small ipsilateral axon branch. In one clone the short ipsilateral axon branch formed a prominent arch peaking towards the anterior end (Fig. 6K, inset). This arching phenotype has been described as a distinguishing feature of a small number of NB lineages including NB 6-2. Based on a close match between the morphology and relative location of these clones to those defined for NB 6-2, we place these three Nmr1-positive neurons within the 6-2 lineage (Fig. 7) (Schmid et al., 1999; Bossing et al., 1996).

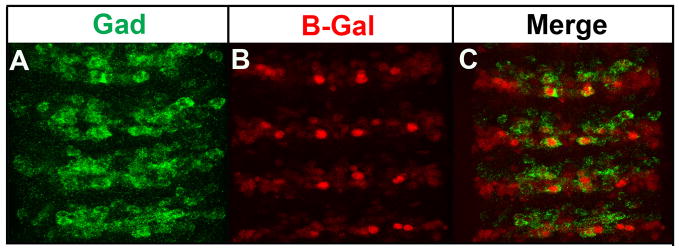

Medial Nmr1 and Nmr2 subsets of neurons are GABAergic

To gain insight into the potential function of Nmr1- and Nmr2-positive neurons, we assayed whether Nmr1 and Nmr2 interneurons express specific classes of neurotransmitters. While Nmr1 and Nmr2 neurons do not express serotonin (Taghert and Goodman, 1984) or the vesicular transporter for glutamate (DVGLUT) (Daniels et al., 2004) (data not shown), a single medial Nmr1/Nmr2-positive neuron strongly expresses vesicular glutamic acid decarboxylase (Gad) (Fig. 8). Gad is the biosynthetic enzyme for γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) (Jackson et al., 1990), an abundant inhibitory neurotransmitter expressed throughout the embryonic CNS. Thus at least one medial Nmr1/Nmr2-positive interneurons is competent to synthesize GABA and to potentially modulate the activity of neural circuits.

Figure 8.

A subset of medial Nmr2 and Nmr1 interneurons co-express glutamic acid decarboxylase.

(A–C) Stage 15 nerve cords from the H15-LacZ reporter line, which labels all Nmr1-positive and Nmr2-positive neurons. (A) Staining for glutamic acid decarboxylase (Gad) specifically identifies GABAergic populations of interneurons (green). (B) Staining for β-Galactosidase (B-Gal) marks all Nmr1 and Nmr2 positive neurons (red). (C) A prominent, medial pair of previously identified Nmr1 and Nmr2 co-expressing neurons detected within each segment of the nerve cord accumulates a high level of vesicular Gad at the plasma membrane (arrows, merge).

nmr2 negatively regulates even-skipped expression

Our loss-of-function studies indicate that nmr1 and nmr2 are necessary to repress eve expression in a few cells in the CNS (Fig. 1E), thus we focused our attention on exploring the negative regulatory relationship between nmr2 and eve. Specifically, we asked whether nmr1 and nmr2 are sufficient to repress eve expression. To do this we used the Gal4/UAS system and Elav-Gal4 to drive nmr2 or nmr1 expression in all post-mitotic neurons of the CNS and assayed the effect on eve expression (Fig. 9). Ubiquitous misexpression of nmr2 causes a significant reduction of eve expression in all Eve-positive neurons (Fig. 9B). In contrast, misexpression of nmr1 causes a very mild reduction of Eve expression in the CNS (Fig. 9C). Thus, nmr2 and to a lesser extent nmr1 can inhibit eve expression in some, but not all, CNS neurons. The mild phenotype observed upon generalized nmr1 expression is not attributable to low level Nmr1 protein expression, as ElavGAL4::UAS-nmr1 embryos display high levels of Nmr1 protein throughout the CNS (data not shown).

In a reciprocal manner, we determined whether eve, a known transcriptional repressor, can inhibit the expression of nmr1 and nmr2. We misexpressed eve in all post-mitotic neurons using the Gal4/UAS system and assayed the effect on Nmr1 or Nmr2 expression. Ubiquitous eve expression in the CNS causes a dramatic reduction of nmr2 and nmr1 expression in the CNS (Fig. 9D–G). However, eve appears sufficient but not necessary to inhibit nmr1 and nmr2 expression since eveID19, a temperature-sensitive allele of eve (Nusslein-Volhard et al., 1985), exhibits normal numbers of Nmr1- and Nmr2-positive neurons (data not shown). As noted, eve and nmr1/nmr2 are expressed in mutually exclusive sets of neurons in the CNS (Fig. 9H,I). Thus, the mutually cross-repressive actions of nmr2 and eve likely help maintain their complementary expression patterns in the CNS. In early embryonic CNS development, we also observed that the loss of nmr2 resulted in the loss of eve expression in the aCC and pCC neurons in predominantly odd-numbered segments (Fig. 1F). Buescher et al. (2006) reported similar observations and attributed this loss of Eve-positive aCC and pCC neurons to the failure of their neuroblast precursor, NB 1-1, to form in odd-numbered segments (Buescher et al., 2006).

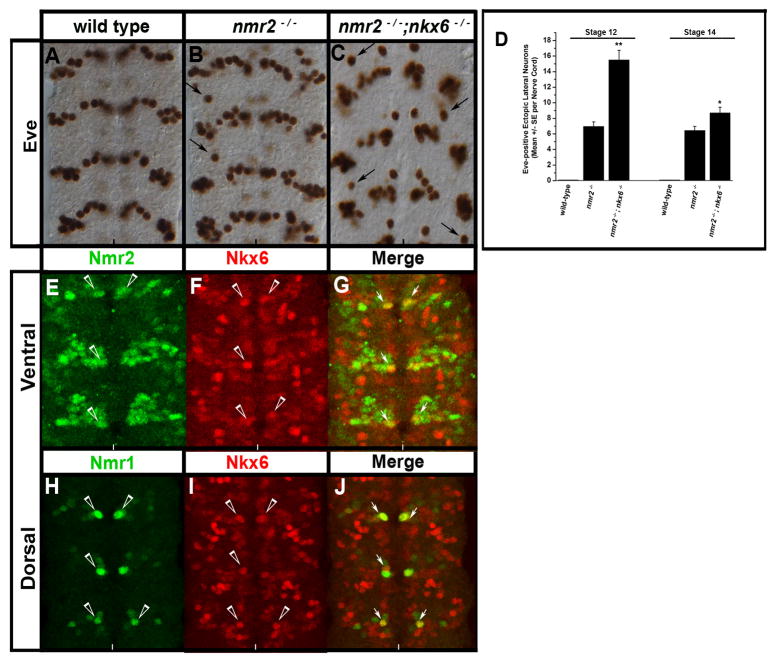

nmr1 and nmr2 interact genetically with nkx6, a key regulator of eve

dhb9kk30and nkx6D26 are two homeodomain transcription factors known to inhibit eve expression in the CNS (Broihier et al., 2004; Broihier and Skeath, 2002). Thus, we constructed embryos doubly mutant for nmr1 or nmr2 in combination with dhb9kk30 or nkx6D26 to determine whether nmr1 and nmr2 act with dhb9kk30 or nkx6D26 to inhibit eve expression. nkx6D26 mutants exhibit a wild-type eve expression pattern while dhb9kk30 single mutants exhibit 2–3 ectopic Eve-positive neurons (Broihier and Skeath, 2002). Embryos doubly mutant for nmr1 or nmr2 and dhb9kk30 do not enhance the eve CNS phenotype over each single mutant (data not shown). However, embryos doubly mutant for nkx6D26 and nmr2 exhibit an increase of ectopic Eve-positive neurons in the lateral CNS relative to either single mutant (Fig. 10A–C). The increase in Eve-positive neurons peaks around stage 12 and diminishes at later stages of development (Fig. 10D). These embryos also exhibit gross defects in the architecture of the CNS, which preclude an ability to assess the exact number of Eve-positive neurons beyond stage 14. We observe co-expression of Nkx6 with Nmr2 (Fig. 9E–G) and Nmr1 (Fig. 10H–J) in a single medial neuron within each hemisegment at later stages of development (stages 13–15). Thus, Nkx6 and Nmr2 are unlikely to act at the same time in the same cells to repress eve in a cell autonomous manner. Rather Nkx6 and Nmr2 may act together during earlier stages of development, or sequentially in the same cells or cell lineage, to inhibit eve expression; alternatively these factors may act in the same cells or within the same lineage to initiate specific interneuronal signaling events that inhibit eve expression in adjacent cells.

Figure 10.

nmr2 and nkx6 collaborate to inhibit eve expression.

(A–C) Stage 14 wild-type and mutant embryonic nerve cords stained for Eve, (D) a chart quantifies the number of Eve-positive lateral neurons in wild-type, nmr2−/−, and nmr2−/−;nkx6−/− mutant backgrounds at stages 12 and 14, (E–J) immunofluorescent staining of Nmr2-, Nmr1-, and Nkx-6-positive neurons in the CNS of Stage 15 wild-type embryos. All images depict the ventral region of the CNS. (A) Stage 14 wild-type Eve expression pattern. (B) As shown previously, nmr2−/− mutant embryos exhibit Eve-positive ectopic lateral neurons (arrows, see Fig. 1B). (C) nmr2−/−;nkx6−/− double mutant embryos exhibit increased numbers of Eve-positive ectopic lateral neurons throughout the nerve cord as compared with nmr2−/− mutants (arrows). The nerve cords of nmr2−/−;nkx6−/− mutants also exhibit severe orientation defects that become pronounced at stages 15–16 (data not shown). (D) Each bar value represents the mean of 20 embryos scored for the number of Eve-positive ectopic lateral neurons observed throughout the nerve cord at stages 12 and 14. The error bars represent the S.E.M. and statistical significance was determined by One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) where p** < 0.001 and p* < 0.01. (E–G) Nmr2 (green) and Nkx6 (red) exhibit a mutually exclusive expression pattern with the exception of one medial neuron per hemisegment that co-expresses Nmr2 and Nkx6 (merge, arrows). (H–J) Nmr1 (green) and Nkx6 (red) are also co-expressed in one medial neuron per hemisegment.

DISCUSSION

The work presented here identifies nmr1 and nmr2 as neuronal fate determinants and confirms that nmr1 and nmr2 act in a partially redundant manner to repress eve expression in a small number of neurons in the CNS (Buescher et al., 2006). In addition, it describes the generation of Nmr1 and Nmr2 specific antibodies, which reveal dynamic and cell-type specific expression profiles of these factors in the CNS, heart and epidermis, while also providing evidence for post-transcriptional regulation of nmr1. Through the use of these molecular reagents, we reveal that most Nmr1/Nmr2-positive neurons define a novel class of interneurons and map a subset of these cells to defined CNS lineages. Finally, we show that nmr1 and nmr2 exhibit cross-repressive interactions with eve in the CNS, and that nmr2 acts with nkx6D25 to repress the CNS expression of eve. Below we discuss our results in light of the known genetic requirements for nmr1 and nmr2 function in the CNS and embryo, and highlight particular sequence characteristics of these loci that suggest nmr1 may be in the process of undergoing non-functionalization.

Our detailed studies on the expression of Nmr1 protein and RNA suggest that the nmr1 transcript is subject to post-transcriptional regulation during early stages of embryogenesis. For example, while the Nmr2 protein pattern faithfully recapitulates its RNA profile, a significant temporal delay exists between the onset of nmr1 transcription and the initial detection of Nmr1 protein in a few cells in the CNS (Fig. 2). Precedence exists for temporal regulation of mRNA translation in the CNS. For example, the nerfin transcript, which codes for a zinc-finger domain containing protein, is expressed in neuroblasts, GMCs and neurons but Nerfin protein is detected only in GMCs and neurons due to the action of multiple microRNAs acting on the nerfin 3′UTR (Kuzin et al., 2005, 2007). In this context it is interesting to note that the nmr1 transcript is predicted to contain a short 3′ UTR and a long 538 bp 5′ UTR (Fig. S4). The 5′ UTR contains a number of conserved sequence blocks towards its 5′ end. While these sequences are not target sites for characterized microRNAs (Enright et al., 2003; Stark et al., 2003), they may represent motifs through which RNA-binding proteins or uncharacterized microRNAs mediate the translational silencing of nmr1. In the future it will be important to define the relevant sequence motifs in the nmr1 transcript in order to begin to define the cis- and trans-acting mechanisms responsible for its post-transcriptional regulation.

We should note that it is formally possible that our Nmr1 specific antibodies fail to recognize a protein isoform expressed during early embryogenesis. However, we view this as unlikely due to the design of the antibody and RNA probes. We generated Nmr1 specific antibodies against a protein fragment that contained the first two exons, and a small region of the third exon, of nmr1 (see Methods), while an anti-sense RNA probe generated from exons 1 and 2 detects the entirety of the nmr1 transcript pattern. Thus, we believe the simplest interpretation of our data is that nmr1 is subject to post-transcriptional regulation during early but not late embryogenesis.

Genetic studies reveal a key role for nmr2 during segmentation, neuroblast formation and specification, heart development and neuronal specification (Buescher et al., 2006; Reim et al., 2005; Qian et al., 2005, Miskolczi-McCallum et al., 2005; Buescher et al., 2004). In contrast, loss of nmr1 exhibits no phenotype on its own. In fact, nmr1 has only been shown to contribute to nmr2 function due to a modest enhancement of the severity of a subset of nmr2 phenotypes observed in embryos doubly-mutant for nmr1 and nmr2 (Buescher et al., 2006; Qian et al., 2005). The clear differences in the genetic requirements for nmr2 and nmr1 during embryonic development have been difficult to reconcile with the nearly identical RNA expression profiles of these factors (Buescher et al., 2006; Qian et al., 2005). In this context, our characterization of the protein expression profiles of Nmr1 and Nmr2 provide a molecular explanation for the functional requirement of nmr1 during a subset of nmr2-dependent events. For example, we observe co-expression of Nmr1 and Nmr2 protein in all cardioblasts and many CNS neurons, consistent with nmr1 acting in a partly redundant manner to nmr2 in these tissues. In contrast, we do not observe Nmr1 protein in neuroblasts, consistent with the lack of a genetic requirement for nmr1 during neuroblast formation and specification. Thus, nmr1 appears to contribute to nmr2 function, albeit weakly, in most or all cells that co-express the two proteins.

The genetic requirement for nmr1 during segmentation remains difficult to explain, as we do not observe Nmr1 protein in segment polarity stripes during early embryogenesis. Nmr1 and Nmr2 proteins are detected in narrow stripes of ventral ectodermal cells during late embryogenesis (Fig. 2). Thus, nmr2 and nmr1 function in these cells may help define the final cuticular pattern of the Drosophila embryo (Buescher et al., 2006). Consistent with this model, interactions between the Wingless, Notch and EGF signaling pathways in late stage embryos is critical to establish the final cuticular pattern of the Drosophila embryo (Walters et al., 2005; Alexandre et al., 1999), and nmr2 has been shown to mediate its effect on segmentation by negatively regulating wingless expression (Buescher et al, 2004). Alternatively, the enhancement of the nmr2 segmentation phenotype observed in nmr1/nmr2 double mutant embryos could arise due to heterozygosity for one or more genes, as overlapping deficiencies were used to construct nmr1/nmr2 double-mutant embryos.

Our work, as well as prior studies, reveals that nmr1 and nmr2 act together to control the specification of eve-expressing neurons in the CNS (Fig. 1; Beuscher et al., 2006). However, due to the similar RNA expression patterns of nmr1 and nmr2 in neuroblasts and neurons, prior studies could not define whether nmr1 and nmr2 function in post-mitotic neurons and/or neural precursors to control the development of these cells. Our observation that Nmr1 protein is expressed in post-mitotic neurons, but not in neural precursors, in the CNS provides strong evidence that nmr1 and nmr2 act in post-mitotic neurons to regulate eve expression. This late function for nmr1 and nmr2 does not preclude nmr2 also acting earlier in the lineage to help mediate this event, a possibility supported by the more severe nature of the nmr2 phenotype with respect to eve-positive neurons. Nonetheless, our work reveals a functional role for nmr1 and nmr2 in post-mitotic neurons, and thus places these factors in the combinatorial code of transcription factors known to govern the specification and differentiation of post-mitotic neurons. Moreover, as nmr1 and nmr2 are expressed in many neurons, they likely play a much broader role during neuronal differentiation than simply regulating eve expression.

nmr1 and nmr2 are paralogs and arose as the result of a duplication of an ancestral Tbx-20 gene. Thus, nmr1 and nmr2 likely exhibited essentially identical gene regulation in the ancestral species in which they first appeared. However, in Drosophila the regulation of nmr1 and nmr2 display clear differences, with nmr2 exhibiting significantly higher RNA expression, and nmr1 being specifically subjected to post-transcriptional regulation. Inspection of the nmr1 and nmr2 loci for key regulatory sequences that promote gene transcription and translation suggests greater selective pressure acts on nmr2 to retain such motifs than on nmr1. For example, the nmr2 locus contains conserved motifs that match the consensus sequences for the Initiator and downstream promoter element (DPE), and for the Drosophila Kozak sequence at its translation start site (Kutach and Kadonaga, 2000; Cavener, 1987). In contrast, we were unable to find matches to the consensus sequences for an Initiator, DPE or TATA box at the predicted nmr1 promoter, while the nmr1 translation start site contains an imperfect match to the Kozak sequence. We did identify a consensus match to an Initiator motif 62 bp upstream of the predicted start of transcription, after scanning 200 bp upstream and downstream of the predicted promoter (Fig. S4). While this sequence is conserved in drosophilids, it is not flanked by a consensus TATA box or DPE. Thus, heightened expression of nmr2 relative to nmr1 may arise, at least in part, due to retention of key regulatory motifs critical for appropriate gene transcription and translation. Together with the paralogous nature of nmr1 and nmr2, these observations indicate that nmr1 may be undergoing non-functionalization – a process often thought to occur to one of two duplicate genes when neither gene assumes a new function following duplication (Prince and Pickett, 2002).

Conclusion

nmr1 and nmr2 are members of the combinatorial code of transcription factors that govern neuronal specification and differentiation. However, extensive expression studies between Nmr1/Nmr2 and many transcription factors known to control motor neuron and interneuron fates revealed little co-expression between these factors (Fig. 5, data not shown). Thus, significant additional work is needed to decipher the functions of nmr1/nmr2 in neurons, and place their action within the complex genetic regulatory hierarchy that governs neuronal differentiation. In this context, our expression and lineage studies, which identify a set of Nmr1/Nmr2-positive neurons as GABAergic, and map a handful of Nmr1-expressing neurons to defined CNS cell lineages, represent a step towards establishing the descriptive foundation required to dissect in detail the CNS functions of nmr1 and nmr2. Clearly, it will be crucial to identify other transcription factors expressed with Nmr1/Nmr2 in neurons, and to define the target genes through which Nmr2/Nmr1 mediate their effect on neuronal differentiation. Thus, we expect the integration of traditional embryological methods with modern genome-wide searches for transcription factor targets to begin to illuminate how Nmr1/2, and other transcription factors, direct distinct sets of neurons to differentiate from each other.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1 H15-lacZ labels more cells in the CNS than either Nmr1 or Nmr2.

Stage 15 H15-lacZ embryos stained for Nmr1 or Nmr2 (green; A, D) and β-Galactosidase (red; B,E). Panels C and F show the merged image of H15-lacZ/Nmr1 and H15-lacZ/Nmr2.

Supplemental Figure 2 Nmr1 and Repo exhibit a mutually exclusive expression pattern while Nmr2 is detected in a few Repo-positive glia.

(A,B) Wild-type stage 15 embryos stained for Nmr1 (green) and Repo (red) or (C,D) Nmr2 (green) and Repo (red). (A,B) In the ventral and dorsal regions of the CNS, no cells co-express Nmr1 and Repo. (C) In the ventral region of the CNS, one Repo-positive glial cell co-expresses Nmr2 (arrowheads). (D) In the dorsal region of the CNS, no cells co-express Nmr2 and Repo. Any apparent overlap results from the merging individual confocal Z-sections and the overlaying of Nmr2-positive and Repo-positive cells in different focal planes.

Supplemental Figure 3 Nmr1/Nmr2 and Engrailed are expressed in distinct sets of cells in the CNS.

(A,B) Wild-type stage 15 embryos stained for Nmr1 (red) and Engrailed (green) or (C,D) Nmr2 (green) and Engrailed (red). (A,B) No cells co-express Nmr1 and Engrailed in the CNS. (C,D) Similarly, no cells co-express Nmr2 and Engrailed.

Supplemental Figure 4 Sequence analysis of the predicted transcriptional and translational start sites of nmr1 and nmr2.

(A) Top: Sequence of predicted transcriptional start site of nmr1. Middle: Sequence of region upstream of predicted nmr1 transcriptional start site that contains a conserved Initiator element but not a DPE. Bottom: Sequence of predicted transcriptional start site of nmr2. Consensus sequences for the Drosophila Initiator and DPE elements are shown at top of the panel. Positions of the Initiator and DPE elements are underlined and nucleotides that match the consensus are shown in red. Conserved nucleotides are shown in upper case; non-conserved residues in lower case. (B) Consensus sequence of the Drosophila Kozak sequence and the corresponding regions of the nmr1 and nmr2 transcripts. (C) Sequence of nmr1 5′UTR; conserved residues are shown in upper case; non-conserved in lower case.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tanya Wolff for providing many second and third chromosomal deficiency lines as well as the Bloomington Stock Center for other deficiency stocks and mutant alleles. We also thank Marita Buescher for the deficiency line Df(2L)x528 and Ian Duncan for the eveID19 mutant alleles. We thank Rob Jackson for the gift of glutamic acid decarboxylase antibody, Ross Cagan for Repo antibody, both Y. Wairkar and A. DiAntonio for the DVGLUT antibody generated by Daniels et al. (2004) as well as Paul Taghert for providing serotonin antibody. S.M.L. was supported by a Ford Foundation Postdoctoral Diversity Fellowship and a Grant-in-Aid administered by the Ford Foundation. L.Q was supported by an American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship. S.M.L. thanks Jake Schaefer and Mohamed Elasri for helpful comments on the manuscript. This research was funded by an NIHBI grant (1 RO1 HL54732) to R.B. and an NINDS grant (RO1 NS036570) to J.B.S.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adell T, Muller WE. Expression pattern of the Brachyury and Tbx2 homologues from the sponge Suberites domuncula. Biol Cell. 2005;97:641–650. doi: 10.1042/BC20040135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn DG, Ruvinsky I, Oates AC, et al. tbx20, a new vertebrate T-box gene expressed in the cranial motor neurons and developing cardiovascular structures in zebrafish. Mech Dev. 2000;95:253–258. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00346-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandre C, Lecourtois M, Vincent J. Wingless and Hedgehog pattern Drosophila denticle belts by regulating the production of short-range signals. Development. 1999;126:689–98. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.24.5689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basson CT, Huang T, Lin RC, et al. Different TBX5 interactions in heart and limb defined by Holt-Oram syndrome mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2919–2924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossing T, Brand AH. Determination of cell fate along the anteroposterior axis of the Drosophila ventral midline. Development. 2006;133:1001–1012. doi: 10.1242/dev.02288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossing T, Udolph G, Doe CQ, Technau GM. The embryonic central nervous system lineages of Drosophila melanogaster I. Neuroblast lineages derived from the ventral half of the neuroectoderm. Dev Biol. 1996;179:41–64. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand AH, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broihier HT, Kuzin A, Zhu Y, et al. Drosophila homeodomain protein Nkx6 coordinates motoneuron subtype identity and axonogenesis. Development. 2004;131:5233–5242. doi: 10.1242/dev.01394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broihier HT, Skeath JB. Drosophila homeodomain protein dHb9 directs neuronal fate via crossrepressive and cell-nonautonomous mechanisms. Neuron. 2002;35:39–50. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00743-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook WJ, Cohen SM. Antagonistic interactions between wingless and decapentaplegic responsible for dorsal-ventral pattern in the Drosophila leg. Science. 1996;273:1373–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5280.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DD, Martz SN, Binder O, et al. Tbx5 and Tbx20 act synergistically to control vertebrate heart morphogenesis. Development. 2005;132:553–563. doi: 10.1242/dev.01596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buescher M, Tio M, Tear G, et al. Functions of the segment polarity genes midline and H15 in Drosophila melanogaster neurogenesis. Dev Biol. 2006;292:418–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buescher M, Svendsen PC, Tio M, et al. Drosophila T box proteins break the symmetry of hedgehog-dependent activation of wingless. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1694–1702. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai CL, Zhou W, Yang L, et al. T-box genes coordinate regional rates of proliferation and regional specification during cardiogenesis. Development. 2005;132:2475–2487. doi: 10.1242/dev.01832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavener DR. Comparison of the consensus sequence flanking translational start sites in Drosophila and vertebrates. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:1353–61. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.4.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman DL, Papaioannou VE. Three neural tubes in mouse embryos with mutations in the T-box gene. Nature. 1998;391:695–697. doi: 10.1038/35624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels RW, Collins CA, Gelfrand MV, et al. Increased expression of the Drosophila vesicular glutamate transporter leads to excess glutamate release and a compensatory decrease in quantal content. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10466–10474. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3001-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doe CQ, Smouse D, Goodman CS. Control of neuronal fate by the Drosophila segmentation gene even-skipped. Nature. 1988;333:376–378. doi: 10.1038/333376a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour HD, Chettouh Z, Deyts C, et al. Precraniate origin of cranial motoneurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:8727–8732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600805103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enright AJ, John B, Gaul U, Tuschl T, Sander C, Marks DS. MicroRNA targets in Drosophila. Genome Biol. 2003;5:R1. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-5-1-r1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong SH, Emelyanov A, The C, Korzh V. Wnt signaling mediated by Tbx2b regulates cell migration during the formation of the neural plate. Development. 2005;132:3587–3596. doi: 10.1242/dev.01933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasch M, Hoey T, Rushlow C, et al. Characterization and localization of the Even-skipped protein of Drosophila. EMBO J. 1987;16:749–759. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb04817.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Brown JJ, Agulnik IS, Silver LM, Papaioannou VE. Expression of T-box genes Tbx2-Tbx5 during chick organogenesis. Mech Dev. 1998;74:165–169. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenningloh G, Rehm EJ, Goodman CS. Genetic analysis of growth cone guidance in Drosophila: fasciclin II functions as a neuronal recognition molecule. Cell. 1991;67:45–57. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90571-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KJ, Stoller J, Gibson M, Chen S, et al. A conserved role for H15-related T-box transcription factors in zebrafish and Drosophila heart formation. Dev Biol. 2000;218:235–247. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halter DA, Urban J, Rickert C, et al. The homeobox gene repo is required for the differentiation and maintenance of glia function in the embryonic nervous system of Drosophila melanogaster. Development. 1995;121:317–322. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison DA, Perrimon N. Simple and efficient generation of marked clones in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 1993;3:424–433. doi: 10.1016/0960-9822(93)90349-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzig MC, Thor S, Thomas JB, et al. Expression and function of the LIM homeodomain protein Apterous during embryonic brain development of Drosophila. Dev Genes Evol. 2001;211:545–554. doi: 10.1007/s00427-001-0195-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hortsch M, Patel NH, Bieber AJ, et al. Drosophila neurotactin, a surface glycoprotein with homology to serine esterases, is dynamically expressed during embryogenesis. Development. 1990;110:1327–1340. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.4.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isshiki T, Pearson B, Holbrook S, Doe CQ. Drosophila neuroblasts sequentially express transcription factors which specify the temporal identity of their neuronal progeny. Cell. 2001;106:511–521. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00465-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson FR, Newby LM, Kulkarni SJ. Drosophila GABAergic systems: sequence and expression of glutamic acid decarboxylase. J Neurochem. 1990;54:1068–1078. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb02359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerome LA, Papaioannou VE. DiGeorge syndrome phenotype in mice mutant for the T-box gene, Tbx1. Nat Genet. 2001;27:286–291. doi: 10.1038/85845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King M, Arnold JS, Shanske A, Morrow BE. T-genes and limb bud development. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:1407–1413. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni SJ, Newby LM, Jackson FR. Drosophila GABAergic systems. II Mutational analysis of chromosomal segment 64AB, a region containing the glutamic acid decarboxylase gene . Mol Gen Genet. 1994;243:555–564. doi: 10.1007/BF00284204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutach AK, Kadonaga JT. The downstream promoter element DPE appears to be as widely used as the TATA box in Drosophila core promoters. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4754–64. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.13.4754-4764.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzin A, Kundu M, Brody T, Odenwald WF. The Drosophila nerfin-1 mRNA requires multiple microRNAs to regulate its spatial and temporal translation dynamics in the developing nervous system. Dev Biol. 2007;310:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzin A, Brody T, Moore AW, Odenwald WF. Nerfin-1 is required for early axon guidance decisions in the developing Drosophila CNS. Dev Biol. 2005;277:347–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai ZC, Rushton E, Bate M, Rubin GM. Loss of function of the Drosophila zfh-1 gene results in abnormal development of mesodermally derived tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4122–4126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.4122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landgraf M, Roy S, Prokop A, VijayRaghavan K, et al. even-skipped determines the dorsal growth of motor axons in Drosophila. Neuron. 1999;22:43–52. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80677-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larroux C, Fahey B, Liubicich D, et al. Developmental expression of transcription factor genes in a desmosponge: insights into the origin of metazoan multicellularity. Evol Dev. 2006;8:150–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2006.00086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layden MJ, Odden JP, Schmid A, et al. Zfh1, a somatic motor neuron transcription factor, regulates axon exit from the CNS. Dev Biol. 2006;291:253–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Qy, Newbury-Ecob RA, Terrett JA, et al. Holt-Oram syndrome is caused by mutations in TBX5, a member of the Brachyury (T) gene family. Nat Genet. 1997;15:21–29. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilly B, Zhao B, Ranganayakulu G, et al. Requirement of MADS domain transcription factor D-MEF2 for muscle formation in Drosophila. Science. 1995;267:688–693. doi: 10.1126/science.7839146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin DM, Goodman CS. Ectopic and increased expression of Fasciclin II alters motoneuron cone guidance. Neuron. 1994;13:507–523. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundell MJ, Lee HK, Perez E, Chadwell L. The regulation of apoptosis by Numb/Notch signaling in the serotonin lineage of Drosophila. Development. 2003;130:4109–4121. doi: 10.1242/dev.00593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren SE, Callahan CA, Thor S, Thomas JB. Control of neuronal pathway selection by the Drosophila LIM homeodomain gene apterous. Development. 1995;121:1769–1773. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.6.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardon G, Solomon NM, Rubin GM. dachshund encodes a nuclear protein required for normal eye and leg development in Drosophila. Development. 1994;120:3473–3486. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.12.3473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel-Aliaga I, Allan DW, Thor S. Independent roles of the dachshund and eyes absent genes in BMP signaling, axon pathfinding and neuronal specification. Development. 2004;131:5837–5848. doi: 10.1242/dev.01447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miskolczi-McCallum CM, Scavetta RJ, Svendsen PC, et al. The Drosophila melanogaster T-box genes midline and H15 are conserved regulators of heart development. Dev Biol. 2005;278:459–472. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naiche LA, Harrelson Z, Kelly RG, Papaioannou VE. T-box genes in vertebrate development. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:219–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.105925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordstrom U, Maier E, Jessell TM, Edlund T. An early role for WNT signaling in specifying neural patterns of Cdx and Hox gene expression and motor neuron subtype identity. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novotny T, Eiselt R, Urban J. Hunchback is required for the specification of the early sublineage of neuroblast 7-3 in the Drosophila central nervous system. Development. 2002;129:1027–1036. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.4.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusslein-Volhard C, Kluding H, Jurgens G. Genes affecting the segmental subdivision of the Drosophila embryo. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1985;50:145–154. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1985.050.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusslein-Volhard C, Wieschaus E, Kluding H. Zygotic loci on the second chromosome. Roux Arch Dev Biol. 1984;193:267–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00848156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papaioannou VE, Silver LM. The T-box gene family. Bioessays. 1998;20:9–19. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199801)20:1<9::AID-BIES4>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel NH. Imaging neuronal subsets and other cell types in whole mount Drosophila embryos and larvae using antibody probes. In: Goldstein LSB, Fyrberg E, editors. Methods in Cell Biology, Vol 44. Drosophila melanogaster: Practical Uses in Cell Biology. Academic Press; New York: 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel NH, Kornberg TB, Goodman CS. Expression of engrailed during segmentation in grasshopper and crayfish. Development. 1989;107:210–212. doi: 10.1242/dev.107.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plageman TF, Jr, Yutzey KE. Differential expression and function of Tbx5 and Tbx20 in cardiac development. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19026–19034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314041200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poeck B, Hofbauer A, Pflugfelder GO. Expression of the Drosophila optomotor-blind gene transcript in neuronal and glial cells of the developing nervous system. Development. 1993;117:1017–1029. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.3.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince VE, Pickett FB. Splitting pairs: the diverging fates of duplicated genes. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;11:827–37. doi: 10.1038/nrg928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian L, Liu J, Bodmer R. Neuromancer TBX20-related genes (H15/midline) promote cell fate specification and morphogenesis of the Drosophila heart. Dev Biol. 2005;279:509–524. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reim I, Mohler JP, Frasch M. Tbx20-related genes, mid and H15, are required for tinman expression, proper patterning, and normal differentiation of cardioblasts in Drosophila. Mech Dev. 2005;122:1056–69. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reim I, Frasch M. The Dorsocross T-box genes are key components of the regulatory network controlling early cardiogenesis in Drosophila. Development. 2005;132:4911–4925. doi: 10.1242/dev.02077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid A, Chiba A, Doe CQ. Clonal analysis of Drosophila embryonic neuroblasts: neural cell types, axon projections, and muscle targets. Development. 1999;128:4653–4689. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.21.4653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt H, Rickert C, Bossing T, et al. The embryonic central nervous system lineages of Drosophila melanogaster II. Neuroblast lineages derived from the dorsal part of the neuroectoderm. Dev Biol. 1997;189:186–204. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeger M, Tear G, Ferres-Marco D, Goodman CS. Mutations affecting growth cone guidance in Drosophila: genes necessary for guidance toward or away from the midline. Neuron. 1993;10:409–426. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90330-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Showell C, Binder O, Conlon FL. T-box genes in early embryogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2004;229:201–218. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Showell C, Christine KS, Mandel EM, Conlon FL. Developmental expression patterns of Tbx1, Tbx2, Tbx5, and Tbx20 in Xenopus tropicalis. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1623–1630. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JB, Harbecke R, Kusch T, et al. Drosophila brachyenteron regulates gene activity and morphogenesis in the gut. Development. 1996;122:3707–3718. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.3707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh MK, Christoffels VM, Dias JM, et al. Tbx20 is essential for cardiac chamber differentiation and repression of Tbx2. Development. 2005;132:2697–2707. doi: 10.1242/dev.01854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sink H, Whitington PM. Pathfinding in the central nervous system and periphery by identified embryonic Drosophila motor neurons. Development. 1991;112:307–316. doi: 10.1242/dev.112.1.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeath JB, Doe CQ. Sanpodo and Notch act in opposition to Numb to distinguish sibling fates in the Drosophila CNS. Development. 1998;125:1857–1865. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.10.1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song MR, Shirasaki R, Cai CL, et al. T-box transcription factor Tbx20 regulates a genetic program for cranial motor neuron cell body migration. Development. 2006;133:4945–4955. doi: 10.1242/dev.02694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark A, Brennecke J, Russell RB, Cohen SM. Identification of Drosophila MicroRNA targets. PLoS Biol. 2003;1(3):E60. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000060. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stennard FA, Harvey RP. T-box transcription factors and their roles in regulatory hierarchies in the developing heart. Development. 2005;132:4897–4910. doi: 10.1242/dev.02099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stennard FA, Costa MW, Lai D, et al. Murine T-box transcription factor Tbx20 acts as a repressor during heart development, and is essential for adult integrity, function, and adaptation. Development. 2005;132:2451–2462. doi: 10.1242/dev.01799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stennard FA, Costa MW, Elliot DA, et al. Cardiac T-box factor Tbx20 directly interacts with Nkx2-5, GATA4, and GATA5 in regulation of gene expression in the developing heart. Dev Biol. 2003;262:206–224. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00385-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szeto DP, Griffin KJ, Kimelman D. Hrt is required for cardiovascular development in zebrafish. Development. 2002;129:5093–5101. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.21.5093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taghert PH, Goodman CS. Cell determination and differentiation of identified serotonin-immunoreactive neurons in the grasshopper embryo. J Neurosci. 1984;4:989–1000. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-04-00989.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi JK, Mileikovskaia M, Koshiba-Takeuchi K, et al. Tbx20 dose-dependently regulates transcription factor networks required for mouse heart and motoneuron development. Development. 2005;132:2463–2474. doi: 10.1242/dev.01827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tautz D, Pfeifle C. A non-radioactive in situ hybridization method for the localization of specific RNAs in Drosophila embryos reveals translational control of the segmentation gene hunchback. Chromosoma. 1989;98:81–85. doi: 10.1007/BF00291041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbach R, Technau GM. Molecular markers for identified neuroblasts in the developing brain of Drosophila. Development. 2003;130:3621–3637. doi: 10.1242/dev.00533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters JW, Muñoz C, Paaby AB, Dinardo S. Serrate-Notch signaling defines the scope of the initial denticle field by modulating EGFR activation. Dev Biol. 2005;286:415–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woollard A. Gene duplications and genetic redundancy in C. elegans (June 25, 2005), WormBook. The C. elegans Research Community, WormBook. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.2.1. http://www.wormbook.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Woollard A, Hodgkin J. The Caenorhabditis elegans fate-determining gene mab9 encodes a T-box protein required to pattern the posterior hindgut. Gene Dev. 2000;14:596–603. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1 H15-lacZ labels more cells in the CNS than either Nmr1 or Nmr2.