Abstract

Background correction is an important preprocessing step for microarray data that attempts to adjust the data for the ambient intensity surrounding each feature. The “normexp” method models the observed pixel intensities as the sum of 2 random variables, one normally distributed and the other exponentially distributed, representing background noise and signal, respectively. Using a saddle-point approximation, Ritchie and others (2007) found normexp to be the best background correction method for 2-color microarray data. This article develops the normexp method further by improving the estimation of the parameters. A complete mathematical development is given of the normexp model and the associated saddle-point approximation. Some subtle numerical programming issues are solved which caused the original normexp method to fail occasionally when applied to unusual data sets. A practical and reliable algorithm is developed for exact maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) using high-quality optimization software and using the saddle-point estimates as starting values. “MLE” is shown to outperform heuristic estimators proposed by other authors, both in terms of estimation accuracy and in terms of performance on real data. The saddle-point approximation is an adequate replacement in most practical situations. The performance of normexp for assessing differential expression is improved by adding a small offset to the corrected intensities.

Keywords: 2-color microarray, Background correction, Maximum likelihood, Nelder-Mead algorithm, Newton- Raphson algorithm, Normal-exponential convolution

1. INTRODUCTION

Fluorescence intensities measured by microarrays are subject to a range of different sources of noise, both between and within arrays. Background correction aims to adjust for these effects by taking account of ambient fluorescence in the neighborhood of each microarray feature.

Ritchie and others (2007) compared a range of background correction methods for 2-color microarrays. A method normexp was introduced which models the observed intensities as the sum of exponentially distributed signals and normally distributed background values. The corrected intensities are obtained as the conditional expectations of the signals given the observations. The normexp method is an adaptation of the background correction method proposed by Irizarry and others (2003) for Affymetrix single-channel arrays, as the first step of the popular “robust multi-array average (RMA)” algorithm for preprocessing Affymetrix expression data. Ritchie and others (2007) showed that normexp, followed by a started-log transformation (i.e. log(x + c), for constant c), gave the lowest false-discovery rate of any commonly available background correction method for 2-color microarrays.

The convolution model underlying the normexp method involves 3 unknown parameters, all of which must be estimated before the method can be applied. In the 2-color context, the parameters must be estimated for each channel on each array, by fitting the convolution model to the observed intensities for that channel. Ritchie and others (2007) suggested an approximate likelihood method for estimating the parameters, based on a saddle-point approximation, but did not give mathematical details.

This article develops the normexp method further by improving the estimation of the parameters. First, a complete mathematical development is given of the normexp model and the associated saddle-point approximation. Second, some subtle numerical programming issues are solved which caused the original normexp method to fail occasionally when applied to unusual data sets. Third, we show how exact maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) of the parameters can be made practical and reliable. Fourth, we compare exact and approximate MLE with estimators proposed by other authors.

MLE has previously proved difficult because of numerical sensitivity of the likelihood function (Irizarry and others, 2003), (Bolstad, 2004), (McGee and Chen, 2006). Instead of MLE, the RMA algorithm, implemented in the affy software package for R (Gautier and others, 2004), uses simple heuristic estimators obtained by smoothing the histogram of observed intensities and partitioning the distribution about its mode (Bolstad, 2004), (Irizarry and others, 2003). McGee and Chen (2006) observed that the RMA estimators are highly biased and proposed 2 new estimators. These methods are based on the RMA kernel smoothing approach but partition the distribution about its mean (the “RMA-mean” method) or 75th percentile (the “RMA-75” method) and then apply a 1-step correction. The RMA-mean and RMA-75 estimators are far less biased than those of RMA but apparently do not improve the performance of the RMA algorithm on real data (McGee and Chen, 2006).

The saddle-point approximation avoids the sensitivity of the likelihood function by providing a closed-form expression for the probability density on the log-scale, ensuring good relative accuracy. However, the saddle point itself must first be found for each data value. This article provides a globally convergent iterative scheme that locates the saddle point to full accuracy in floating-point arithmetic in all cases.

The accuracy of the different estimators are compared in a simulation study. The estimators are also compared using the extensive battery of calibration data sets assembled by Ritchie and others (2007). This allows the estimators to be compared according to their ability to estimate fold changes and to detect differential expression on real data. As in Ritchie and others (2007), the assumed context is that of a small microarray experiment in which popular differential expression methods are to be applied. MLE is shown to have markedly better performance than the heuristic estimators.

Section 2 describes the normexp convolution model, presents the MLE and “saddle” procedures, and addresses some challenges in their implementation. Section 3 briefly describes the 3 test data sets with known levels of differential expression. Section 4 compares the 4 estimation schemes both by simulation and by performance on the test data sets.

2. CORRECTION METHODS

2.1. The normal–exponential convolution model

Image analysis software for 2-color microarrays produces red foreground and background intensities Rf and Rb and green foreground and background intensities Gf and Gb for each spot on each array. Our aim is to adjust the foreground intensities Rf and Gf for the ambient intensities represented by Rb and Gb.

The normexp model for the red channel assumes Rf = Rb + B + S, where S is the true expression intensity signal and B is the residual background not captured by Rb. The model for the green channel is similar. The signal S is assumed exponentially distributed with mean α, while B is normally distributed with mean μ and variance σ2. The parameters μ, σ2, and α are assumed different for each channel on each array. All variables are assumed independent.

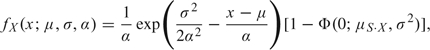

Write X = Rf − Rb for the background-subtracted observed intensity. The normexp model becomes

| (2.1) |

The joint density of B and S is just the product of densities

| (2.2) |

where s > 0 and φ(·) is the Gaussian density function. A simple transformation gives the joint density of X and S as

|

where μS·X = x − μ − σ2/α. Integrating over s gives the marginal density of X:

|

(2.3) |

where Φ(·) is the Gaussian distribution function. Dividing the joint by the marginal gives the conditional density of S given X as

for s > 0, which is a truncated Gaussian distribution. Our estimate of the signal given the observed intensities is the conditional expectation

| (2.4) |

2.2. Saddle-point approximation

MLE requires the marginal density (2.3), which turns out to be difficult to compute with full relative accuracy in floating-point arithmetic, due to subtractive cancelation affecting both factors in the expression. As an alternative, the saddle-point approximation, or tilted Edgeworth expansion, provides a means of approximating the density of any random variable from its cumulant generating function (Barndorff-Nielsen and Cox, 1981, p. 104). The approximation is attractive because it typically remains accurate far into the tails of the distribution.

The cumulant generating function of X is immediately available as the sum of those for B and S,

where θ < 1/α. The definition of the cumulant generating function implies that g(x;θ) = fX(x)exp[yθ − KX(θ)] integrates to unity for all θ. Here, we suppress the dependence of fX on μ, σ, and α for notational simplicity. The density g(x;θ) defines a linear exponential family with canonical parameter θ and rth cumulant κr = KX(r)(θ).

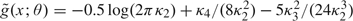

The second-order Edgeworth expansion for g (Barndorff-Nielsen and Cox, 1981, p. 106) is log  yielding the approximation

yielding the approximation  . The key feature which makes the saddle-point approximation so effective is its ability to choose θ to make the Edgeworth expansion as accurate as possible for each x, by choosing θ so that x is the mean of the distribution, that is θ is chosen to solve the saddle-point equation

. The key feature which makes the saddle-point approximation so effective is its ability to choose θ to make the Edgeworth expansion as accurate as possible for each x, by choosing θ so that x is the mean of the distribution, that is θ is chosen to solve the saddle-point equation

| (2.5) |

for θ < 1/α. Although this equation has a simple analytic solution, computing the solution is subject to catastrophic subtractive cancelation for certain values of σ and α. Details of how we avert this numerical issue are provided in Section A of the supplementary material available at Biostatistics online (http://www.biostatistics.oxfordjournals.org).

2.3. Optimization

Given a set of observed intensities xi, i = 1,…,n, the unknown parameters μ, σ, and α must be estimated before the correction formula (2.4) can be applied. Starting values are obtained as follows. The initial estimate  0 of μ is the 5% quantile of the xi. The initial variance

0 of μ is the 5% quantile of the xi. The initial variance  is the mean of (xi−

is the mean of (xi− 0)2 for xi<

0)2 for xi< 0. The initial

0. The initial  is

is  .

.

Next, the saddle-point approximation to the likelihood is maximized using the Nelder–Mead (1965) simplex algorithm. Finally, using the saddle-point estimates as starting values, the exact likelihood is maximized using the nlminb function of R, which performs unconstrained minimization using PORT routines (Gay, 1981), (Gay, 1983), (Gay, 1990). First and second derivatives of fX with respect to μ, logα, and logσ2 are supplied. Optimizing the likelihood with respect to logα and logσ2, rather than α and σ2, avoids parameter constraints and improves convergence.

The algorithm is implemented in the limma software package for R (Smyth, 2005). Saddle-point parameter estimation takes about 1 s per channel with 20 000 probe arrays on a 2 GHz Windows PC. Exact MLE takes about 50% longer. Time taken is roughly linear with the number of probes.

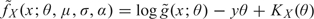

2.4. Transformation and offset

The normexp background correction (2.4) is performed for each channel on each array, yielding adjusted strictly positive red and green intensities R and G for each spot on each array. These are then converted to log-ratios, M = log2(R/G), and log-averages,  (Yang and others, 2001).

(Yang and others, 2001).

It also proves useful to offset the intensities by a small positive value k, giving offset log-ratios M = log2[(R + k)/(G + k)]. This simple transformation shifts the intensities away from 0 and serves to stabilize the variance of the log-ratios at low intensities (Rocke and Durbin, 2003), (Ritchie and others, 2007). The value k = 50 was chosen for this study on the basis of our previous experience with cDNA microarray experiments (Ritchie and others, 2007).

3. TEST DATA

3.1. Spike-in experiment

We use the same 3 calibration data sets as Ritchie and others (2007). The first uses Lucidea Universal ScoreCard controls (Amersham Biosciences) to assess bias. Twelve copies of the control probe set were printed in duplicate on 9 cDNA microarrays, along with a 13K clone library. Only the control probes are analyzed here. Prior to labeling, test and reference control RNA were spiked into RNA samples to produce known fold changes (Supplementary Table 1 available at Biostatistics online). All 8 background correction methods (RMA, RMA-75, saddle, and MLE, with and without the offset) were applied. The resulting log-ratios were normalized and duplicate spots were combined to give an estimate of the log2-fold change as described by Ritchie and others (2007).

3.2. Mixture experiment

The second data set is from Holloway and others (2006). Six RNA mixtures consisting of mRNA from MCF7 and Jurkat cell lines in known relative concentrations (100%:0%, 94%:6%, 88%:12%, 76%:24%, 50%:50% and 0%:100%) were compared to pure Jurkat reference mRNA on 12 cDNA microarrays printed with a Human 10.5K clone set. Dye-swap pairs were performed for each of the 6 mixtures. All 8 background correction methods were applied and the data were normalized using print-tip loess (Yang and others, 2001). Probe-wise nonlinear regression equations were fitted to the normalized log-ratios (Holloway and others, 2006). This produced for each probe a reliable consensus estimate of the MCF7 to Jurkat fold change and a standard deviation that estimates the between-array measurement error.

3.3. Quality control study

The final data set is from Ritchie and others (2006) and comprises 111 replicate arrays printed with the same 10.5k clone set as in the mixture study and hybridized with MCF7 (Cy3) and Jurkat mRNA (Cy5). Spot image data were morph background corrected and print-tip loess normalized. This very large data set enables genes truly differentially expressed (DE) between MCF7 and Jurkat to be identified with a high degree of confidence.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Reliability

The estimation scheme outlined in Section 2.3 has proved to be extremely reliable. It has converged successfully for all data sets the authors have encountered so far, including thousands of simulated and real microarrays. This contrasts with earlier experiences reported by McGee and Chen (2006), whose optimization algorithm, using Newton's method, converged in only 15% of cases, even when initial estimates were equal to the true parameter values.

RMA estimation also returned useable values for all data sets. The RMA-mean and RMA-75 methods each failed for some simulated data sets, the former slightly more often than the latter. Since the two are otherwise similar in performance, results will be presented here only for RMA-75. RMA-75 returned NaNs for 32% of simulated data sets with σ = 5 and α = 104 and for 0.3% of data sets with σ = 20 and α = 104.

4.2. Estimation accuracy

Data were simulated for all combinations of μ∈{30,100,500}, σ∈{5,20,100}, and α∈{102,103,104}. These values represent a very wide range of scenarios in terms of the distribution of foreground values typically observed in microarray data. For each combination of parameter values, 1000 replicate samples of 20 000 observed intensities X were generated. Results are presented only for μ = 100 as the other results are almost identical.

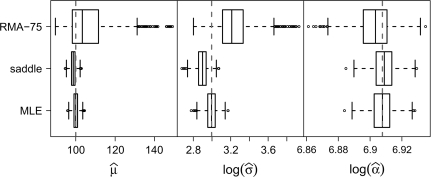

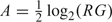

The MLE bias and standard deviation were the smallest, followed closely by those of saddle (Tables 1–3). RMA-75 is much more biased and RMA is by far the worst. Parameter estimates for individual data sets for the representative parameter values σ = 20 and α = 1000 are plotted in Figure 1; the estimates from RMA fall outside the range of this plot. MLE is the most precise with almost no bias. Saddle is equally precise but with some bias, tending to underestimate σ. RMA-75 and RMA on the other hand overestimate σ.

Table 1.

Bias and standard deviation (shown in brackets) in estimating μ for the 4 estimation methods in 9 different scenarios. The true values of α and σ in each scenario are shown in the first 2 columns, and μ = 100 for all scenarios. All values are given to 2 significant figures

| σ | α | MLE | Saddle | RMA-75 | RMA |

| 5 | 102 | 0.0079 (0.22) | – 0.25 (0.22) | 1.7 (1.6) | 12 (2.7) |

| 20 | 102 | 0.0024 (0.47) | 0.013 (0.50) | 5.4 (2.3) | 25 (2.6) |

| 100 | 102 | 0.013 (1.6) | 11.0 (1.5) | 4.8 (11) | 47 (9.0) |

| 5 | 103 | – 0.023 (0.67) | – 0.37 (0.65) | 4.2 (7.5) | 44 (23) |

| 20 | 103 | – 0.025 (1.4) | – 1.3 (1.4) | 6.6 (11) | 69 (24) |

| 100 | 103 | – 0.098 (3.1) | – 3.4 (3.1) | 26.0 (18) | 170 (24) |

| 5 | 104 | 0.022 (2.3) | – 0.36 (2.2) | 32.0 (64) | 380 (230) |

| 20 | 104 | 0.20 (4.2) | – 1.3 (4.0) | 32.0 (66) | 390 (220) |

| 100 | 104 | 0.069 (9.2) | – 6.5 (9.0) | 41.0 (85) | 520 (240) |

Table 2.

Bias and standard deviation (shown in brackets) in estimating σ for the 4 estimation methods in 9 different scenarios. The true values of α and σ in each scenario are shown in the first 2 columns, and μ = 100 for all scenarios. All values are given to 2 significant figures. ∞a and ∞b indicate, respectively, where 32.4% and 0.3% of replicates yielded infinite estimates

| σ | α | MLE | Saddle | RMA-75 | RMA |

| 5 | 102 | 0.00059 (0.20) | – 0.40 (0.19) | 1.5 (0.71) | 7.0 (1.9) |

| 20 | 102 | – 0.0069 (0.40) | – 0.46 (0.43) | 5.6 (1.0) | 15.0 (1.6) |

| 100 | 102 | 0.003 (1.0) | 7.3 (0.99) | 25.0 (5.0) | 45.0 (5.1) |

| 5 | 103 | – 0.067 (0.62) | – 0.56 (0.56) | 3.2 (4.7) | 32.0 (19) |

| 20 | 103 | – 0.11 (1.2) | – 1.9 (1.1) | 6.0 (5.3) | 44.0 (19) |

| 100 | 103 | – 0.00048 (2.8) | – 5.9 (2.7) | 27.0 (7.8) | 100.0 (16) |

| 5 | 104 | – 0.72 (2.4) | – 1.2 (2.1) | ∞a (∞a) | 310.0 (190) |

| 20 | 104 | – 0.40 (4.0) | – 2.5 (3.6) | ∞b (∞b) | 300.0 (180) |

| 100 | 104 | – 0.52 (8.5) | – 10.0 (7.8) | 36.0 (46) | 360.0 (190) |

Table 3.

Bias and standard deviation (shown in brackets) in estimating α for the 4 estimation methods in 9 different scenarios. The true values of α and σ in each scenario are shown in the first 2 columns, and μ = 100 for all scenarios. All values are given to 2 significant figures

| σ | α | MLE | Saddle | RMA-75 | RMA |

| 5 | 102 | – 0.00013 (0.75) | 0.25 (0.75) | – 1.1 (1.5) | – 80 (0.31) |

| 20 | 102 | – 0.013 (0.82) | – 0.023 (0.84) | – 2.5 (1.9) | – 79 (0.40) |

| 100 | 102 | – 0.046 (1.6) | – 11.0 (1.5) | 27.0 (8.1) | – 69 (4.4) |

| 5 | 103 | 0.021 (6.8) | 0.37 (6.8) | – 2.8 (10) | – 800 (2.9) |

| 20 | 103 | 0.11 (6.8) | 1.4 (6.8) | – 4.6 (12) | – 800 (2.9) |

| 100 | 103 | – 0.16 (7.5) | 3.2 (7.5) | – 15.0 (16) | – 790 (3.2) |

| 5 | 104 | 0.50 (72) | 1.0 (72) | – 28.0 (100) | – 8000 (28) |

| 20 | 104 | – 3.2 (69) | – 1.6 (69) | – 29.0 (100) | – 8000 (28) |

| 100 | 104 | 3.1 (71) | 9.5 (71) | – 23.0 (110) | – 8000 (30) |

Fig. 1.

Box plots of parameter estimates for the 3 best-performing methods. The true values of the parameters are indicated by dashed vertical lines. Estimates of RMA were so far from those of the other methods that do not appear when plotted on this scale (see Tables 1–3).

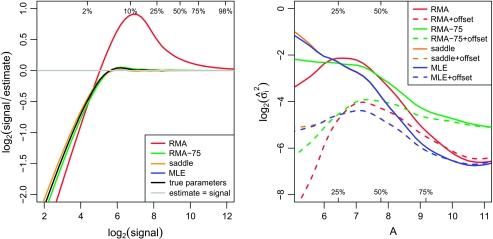

Another way to view accuracy is in terms of ability to return the correct signal values. The left panel of Figure 2 shows the bias with which E(S|X) estimates S on the log2-scale, for μ = 0, σ = 20, and α = 1000. Here, RMA-75 and especially RMA yield far more biased estimates of the signal than MLE or saddle, which are relatively accurate. Although MLE and saddle do tend to overestimate the true signal at lower intensities, this is indistinguishable from the bias that arises from inserting the true parameter values into E(S|X).

Fig. 2.

Left panel: smoothed log2-ratio of the true to the estimated signal versus the true signal. The black line shows this relationship if the true parameter values are used instead of estimates. The data used for this figure include 100 000 observations simulated with μ = 0, σ = 20, and α = 1000. Quantiles for the signal distribution are marked. The curves were smoothed using the lowess function in R (Cleveland, 1979). Right panel: smoothed  2 from the nonlinear fits versus intensity for the mixture experiment. The A-values have been standardized between methods and plotted from the 5th to the 95th percentiles. The quantiles of the A-values are marked.

2 from the nonlinear fits versus intensity for the mixture experiment. The A-values have been standardized between methods and plotted from the 5th to the 95th percentiles. The quantiles of the A-values are marked.

4.3. Implicit offsets

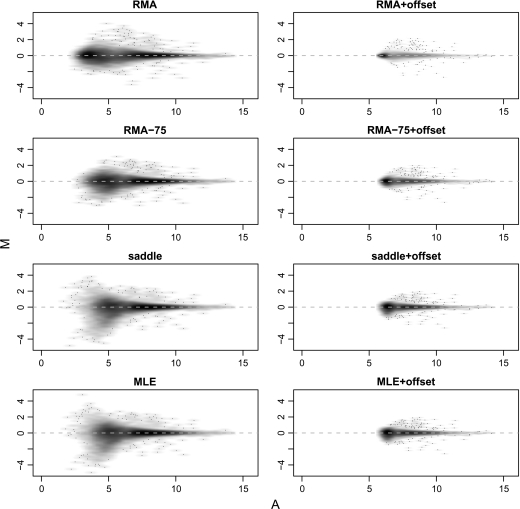

The normalized M- and A-values for one array from the mixture experiment are shown in Figure 3. This array has 100% Jurkat on both channels, so there is no true differential expression.

Fig. 3.

MA-plots obtained using different background correction methods for a self–self hybridization from the mixture experiment.

Some fanning of M-values is apparent at low A-values in the MLE and saddle panels. This fanning is essentially eliminated in the corresponding offset panels at the cost of compressing the range of A-values. Compared with MLE, RMA-75 and especially RMA show a somewhat compressed range of A- and M-values even before the offset is applied. Our interpretation is that these estimation schemes implicitly incorporate offsets, which arise from the fact that they tend to overestimate the quantity μS·X. Adding an offset to RMA is therefore in effect a double offset.

For this array, high offset and low M-value variability is desirable because the true M-values are zero. For arrays with genuine differential expression, compression of the M-values might appear as bias. We examine this in Section 4.5.

4.4. Precision of expression values

We now examine the precision of the background-corrected intensities, using results from the mixture experiment. The residual standard deviation for each probe,  i, is a measure of the precision with which the M-values returned by the microarrays follow the pattern of the mixing proportions. The right panel of Figure 2 shows the trend in variability for each background method as a function of intensity. The vertical scale is log2-variance, so each unit on the vertical axis corresponds to a 2-fold change in variance.

i, is a measure of the precision with which the M-values returned by the microarrays follow the pattern of the mixing proportions. The right panel of Figure 2 shows the trend in variability for each background method as a function of intensity. The vertical scale is log2-variance, so each unit on the vertical axis corresponds to a 2-fold change in variance.

As expected, precision improves with intensity for all the background correction methods prior to applying an offset. MLE and saddle have the best precision of the 4 methods for most of the intensity range. RMA-75 is relatively poor at higher intensities. After adding an offset, MLE and saddle have roughly constant variance across the intensity range, whereas the offset seems overdone for RMA and RMA-75, which now show a reversed trend in precision.

4.5. Bias of expression values

It is to be expected that higher precision, purchased by compressing the intensity range, will also result in attenuated signal. This is confirmed by examining the MCF7–Jurkat log-fold changes estimated from the mixture experiment. Supplementary Figure 1 available at Biostatistics online shows box plots of the log-fold changes arising from each method. The spread of fold changes narrows when offsets are added, although the largest fold changes remain nearly as great.

To confirm whether attenuated fold changes can be interpreted as bias, we turn to the spike-in experiment data. Supplementary Figure 2 available at Biostatistics online shows the M-values for a typical slide for the non-DE calibration controls and for the DE D03Med ratio controls, theoretically having 3-fold change down ( − log23 = − 1.58). All methods give log-ratios which are slightly biased towards 0, and the bias increases when offsets are added. There is surprisingly little difference between the 4 estimation algorithms, all leading to broadly similar bias.

4.6. Assessing differential expression

We now assess the ability of background corrected expression values to identify DE genes correctly. Apart from the self–self hybridizations, the mixture experiment consists of 5 dye-swap pairs of arrays. We assessed differential expression between MCF7 and Jurkat using each pair of arrays separately. The RNA mixtures vary from 100% to 50% MCF7, so the magnitude of the fold changes will vary from one pair of the arrays to another, but the set of DE genes should be the same in each case.

Using only 2 arrays to find DE genes presents a challenging problem because there is only one degree of freedom available to estimate gene-wise standard deviations. The level of difficulty further increases with the concentration of Jurkat in the MCF7:Jurkat RNA mixture. The use of ordinary t-tests or other traditional univariate statistics to assess differential expression would be disastrous (Smyth, 2004). Instead, we use two of the most popular algorithms for microarray differential expression which have the characteristic of “borrowing” information between genes and so enable statistical inferences with some confidence even for small numbers of replicate arrays. Genes were ranked in terms of evidence for differential expression using significance analysis of microarrays (SAM) regularized t-statistics (Tusher and others, 2001) and using empirical Bayes moderated t-statistics (Smyth, 2004). The statistics were calculated using the samr (http://www-stat.stanford.edu/display=’block'∼tibs/SAM/) and limma (Smyth, 2005) software packages, respectively.

To assess the success of the differential expression analyses, an independent determination of which genes are truly DE is required. The top 30% of genes, as ranked by moderated t-statistics, from the quality control study were selected as unambiguously DE and the bottom 40% as unambiguously non-DE. This gave 3098 DE and 4130 non-DE genes. The remaining 30% of genes were treated as indeterminate and are not used in the analysis.

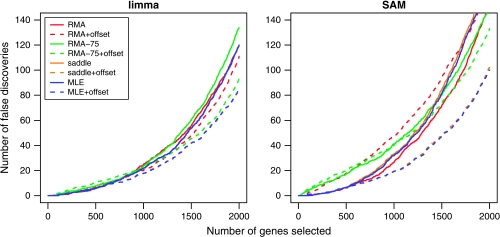

Figure 4 shows the number of false discoveries for each method versus the number of genes selected by ranking the genes using absolute t-statistics, from largest to smallest for (a) limma and (b) SAM. The curves have been averaged over the 5 dye-swap pairs. The limma curves show that adding an offset reduces the false-discovery rate, with the best performance achieved by MLE and saddle, followed by RMA-75 and then RMA. For SAM, the advantage of “MLE + offset” and “saddle + offset” over the methods is even more marked. SAM appears to penalize the methods which do not stabilize the variance.

Fig. 4.

Number of false discoveries from the mixture data set using moderated t-statistics from (a) limma and (b) SAM. Each curve is an average over the 5 mixtures.

5. DISCUSSION

In this article, we have shown that exact MLE gives the most accurate estimation of the normexp parameters, which translates into higher precision for the computed log-ratios of expression. The saddle-point approximation is a very close competitor. The heuristic normexp estimators are markedly poorer in estimation accuracy. Furthermore, RMA-mean and RMA-75 fail occasionally and even frequently for some simulated scenarios. However, MLE and saddle converged successfully in all of our tests.

The performance of normexp for assessing differential expression on real data is improved when combined with an offset, as a result of stabilizing the variance as a function of intensity. MLE + offset and saddle + offset gave the lowest false-discovery rates. Although exact MLE does slightly better, the saddle-point approximation could be considered an adequate replacement in most practical situations.

Estimation accuracy did not directly translate to practical performance in all cases. RMA gives easily the most biased parameter estimates. Yet when we turned to the real data examples, RMA yielded higher precision and fewer false positives than RMA-75. Prior to offset, RMA is the best of all the methods when used with SAM significance analysis. This can be understood in terms of noise–bias trade-off. It appears that the biased RMA estimators have the fortuitous effect of introducing an implicit offset into the corrected intensities, and this has a variance stabilizing effect. This partly explains why the RMA algorithm has been so successful for Affymetrix data. RMA also tends to return roughly similar parameter estimates regardless of the data, producing more consistent parameter estimates between arrays than the other methods. We speculate that this consistency may also help its performance on real data.

Since our study was completed, Ding and others (2008) developed a normexp-type background correction method for Illumina microarray data. They proposed a Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulation method to approximate the maximum likelihood parameter estimates. Their method is not directly applicable to non-Illumina data because it requires Illumina negative controls. MCMC is far more computationally intensive than our Newton–Raphson MLE and returns estimates which vary stochastically from run to run.

Our algorithm is the first to return reliable, exact maximum likelihood estimates for the normexp model. This was only achieved after careful attention to a number of numerical analysis issues. In initial attempts, numerical issues including subtractive cancelation prevented us from computing the likelihood for some data sets. Several ingredients were required before reliable success was achieved including: (1) good initial estimates provided by the saddle procedure, (2) optimizing with respect to logα and logσ instead of α and σ (to enforce α > 0 and σ > 0), and (3) optimizing using both first and second derivatives. Note that the Nelder–Mead algorithm was used first with the saddle-point likelihood, then a pseudo-Newton–Raphson algorithm was used on the exact likelihood once a focused parameter range was established. The Nelder–Mead algorithm could not have been used directly on the exact likelihood because of the much wider range of parameter values under which the likelihood would need to be evaluated. Nor could the Newton–Raphson have been applied to the saddle-point approximation because of the lack of good starting values.

Although we have focused exclusively here on 2-color microarrays, our algorithmic development has obvious applications to other micoarray platforms as well.

FUNDING

Allan Harris memorial scholarship (J.D.S.); Isaac Newton Trust (M.E.R.); National Health and Medical Research Council Program Grant (406657 to G.K.S.). Funding for open access charge: NHMRC Program Grant (G. K. S.).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Terry Speed and Ben Bolstad for valuable discussions and to a coeditor, an associate editor, and an anonymous reviewer for useful suggestions. Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Barndorff-Nielsen OE, Cox DR. Asymptotic Techniques for Use in Statistics. London, UK: Chapman and Hall; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Bolstad BM. Low-level analysis of high-density oligonucleotide array data. Berkeley, CA: University of California; 2004. background, normalization and summarization, [PhD. Thesis] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland WS. Robust locally weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1979;74:829–836. [Google Scholar]

- Ding L-H, Xie Y, Park S, Xiao G, Story MD. Enhanced identification and biological validation of differential gene expression via Illumina whole-genome expression arrays through the use of the model-based background correction methodology. Nucleic Acids Research. 2008 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn234. 36, e58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier L, Cope L, Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA. affy—analysis of Affymetrix GeneChip data at the probe level. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:307–315. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay DM. Computing optimal locally constrained steps. SIAM Journal on Scientific and Statistical Computing. 1981;2:186–197. [Google Scholar]

- Gay DM. Algorithm 611—subroutines for unconstrained minimization using a model/trust-region approach. ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software. 1983;9:503–524. [Google Scholar]

- Gay DM. Computing science technical report no. 153: usage summary for selected optimization routines. Technical Report. Murray Hill, NJ: AT and T Bell Laboratories; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Holloway AJ, Oshlack A, Diyagama DS, Bowtell DD, Smyth GK. Statistical analysis of an RNA titration series evaluates microarray precision and sensitivity on a whole-array basis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:511. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, Speed TP. Exploration, normalization and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–264. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee M, Chen Z. Parameter estimation for the exponential-normal convolution model for background correction of Affymetrix GeneChip data. Statistical Applications in Genetics and Molecular Biology. 2006 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1237. 5, Article 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelder JA, Mead R. A simplex algorithm for function minimization. Computer Journal. 1965;7:308–313. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie ME, Diyagama D, Neilson J, van Laar R, Dobrovic A, Holloway A, Smyth GK. Empirical array quality weights for microarray data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-261. 7, Article 261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie ME, Silver JD, Oshlack A, Holmes M, Diyagama D, Holloway A, Smyth GK. A comparison of background correction methods for two-colour microarrays. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2700–2707. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocke DM, Durbin B. Approximate variance-stabilizing transformations for gene-expression microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:966–972. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Statistical Applications in Genetics and Molecular Biology. 2004 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. 3, Article 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK. Limma: linear models for microarray data. In: Gentleman R, Carey V, Dudoit S, Irizarry R, Huber W, editors. Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions using R and Bioconductor. New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 397–420. [Google Scholar]

- Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YH, Dudoit S, Luu P, Speed T. Bittner ML, Chen Y, Dorsel AN, Dougherty ER, editors. Normalization for cDNA microarray data. Microarrays: Optical Technologies and Informatics. Proceedings of SPIE. Bellingham, WA: International Society for Optical Engineering. 2001;4266:141–152. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.