Abstract

The Argonaute/PIWI protein family consists of Argonaute and PIWI subfamilies. Argonautes function in RNA interference and micro-RNA pathways; whereas PIWIs bind to PIWI-interacting RNAs and regulate germ line development, stem cell maintenance, epigenetic regulation, and transposition. However, the role of PIWIs in mammalian stem cells has not been demonstrated, and molecular mechanisms mediated by PIWIs remain elusive. Here we show that MILI, a murine PIWI protein, is expressed in the cytoplasm of testicular germ line stem cells, spermatogonia, and early spermatocytes, where it is enriched in chromatoid bodies. MILI is essential for the self-renewing division and differentiation of germ line stem cells but does not affect initial establishment of the germ line stem cell population at 7 days postpartum. Furthermore, MILI forms a stable RNA-independent complex with eIF3a and associates with the eIF4E- and eIF4G-containing m7G cap-binding complex. In isolated 7 days postpartum seminiferous tubules containing mostly germ line stem cells, the mili mutation has no effect on the cellular mRNA level yet significantly reduces the rate of protein synthesis. These observations indicate that MILI may positively regulate translation and that such regulation is required for germ line stem cell self-renewal.

Stem cells are defined by their dual ability to self-renew and to produce numerous differentiated daughter cells. Among adult tissue stem cells, germ line stem cells in mammalian testes serve as the source of spermatogenesis, a robust stem cell-driven process that generates millions of sperm hourly (1). In the testis, germ line stem cells can be identified as a subpopulation of spermatogonia that reside in the basal layer of the seminiferous epithelium. These stem cells divide in a self-renewing fashion to produce differentiating spermatogonia, which then further divide and differentiate into numerous spermatocytes. Spermatocytes undergo meiosis to produce haploid round spermatids, which then undertake drastic morphological changes via a process called spermiogenesis to become motile sperm. Germ line stem cells are not only of paramount importance in reproduction but also are effective models for studying molecular mechanisms that define the fate and behavior of stem cells in general.

Germ line stem cell division and differentiation are regulated by both intercellular signaling and cell-autonomous mechanisms (1). The requirement of intercellular signaling is exemplified by mutations in c-Kit receptors or its ligand, stem cell factor, which causes spermatogonial arrest prior to the differentiating (A1) spermatogonia stage (2, 3). Intercellular signaling also involves dose-sensitive regulation by Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor, since mice heterozygous for its gene (Gdnf) display aberrant germ line stem cell division (4). Perhaps the best illustrated cell-autonomous requirements for germ line stem cell maintenance are Plzf and Sox3 genes, both of which encodes transcriptional factors (5-7).

The cell-autonomous mechanism for mammalian germ line stem cell self-renewal probably involves translational regulation, as inferred from studies of germ line stem cells in lower model systems and spermatogenesis in mammals. In Drosophila, translational repression mediated by Pumilio and Nanos is crucial for maintaining the undifferentiated states of germ line stem cells and their precursors, primordial germ cells (8-10). In Caenorhabditis elegans, ATX-2, a homolog of mammalian ATAXIN 2, binds to cytoplasmic poly(A)-binding protein and is required for translational regulation of germ line stem cell proliferation (11). In mice, translational regulation has been shown to be crucial for spermiogenesis (12), although its role in germ line stem cells is not yet determined. However, studies of a mutation that affects germ line stem cell maintenance, Jsd (juvenile spermatogonial depletion), hint at a role for translation in mammalian germ line stem cell self-renewal. Jsd mutant mice can only undergo one round of spermatogenesis, followed by early (Aal) spermatogonia arrest (13). Molecular analysis indicates that the Jsd mutation affects mUtp14b, a testis-specific retroposed copy of the ubiquitously expressed gene mUtp14a (14). This gene is homologous to the yeast UTP14 gene, which is an essential component of a large ribonucleoprotein complex containing the U3 small nucleolar RNA (15). Deletion of UTP proteins in yeast inhibits 18 S rRNA production, indicating that they are part of the active pre-rRNA-processing complex. Similarly, mice lacking Dazl (deleted in azoospermia-like) contain no differentiated spermatogonia (16), and Dazl has been implicated in translational regulation of meiotic genes but not germ line stem cells (17, 18).

Translational regulation of germ line stem cells may involve the PIWI/ARGONAUTE (AGO) protein family, in addition to their known role in transposition repression and epigenetic silencing (19, 20). The PIWI/AGO family was first discovered to be required for stem cell maintenance in diverse organisms, such as Drosophila melanogaster, C. elegans, and Arabidopsis (21). This stem cell function has also been demonstrated in planaria (22). Recently, the role of piwi genes in C. elegans spermatogenesis has been further defined (23, 24). The PIWI/AGO protein family consists of AGO and PIWI subfamilies. AGO proteins bind to ∼21-nucleotide small interfering RNAs and micro-RNAs (miRNAs).6 They function in RNA interference and miRNA pathways as essential components of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and RNA-induced silencing of transcription (RITS) complex to negatively regulate gene expression at the posttranscriptional and transcriptional level, respectively. Recently, mammalian AGO2 has been shown to up-regulate translation via the AU-rich elements (ARE) in mRNA 3′-untranslated regions (25). In contrast, PIWI proteins bind to 24-31-nucleotide PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) and regulate germ line development, stem cell maintenance, epigenetic regulation, and transposition (26-34). Two PIWI proteins in Drosophila, AUBERGINE and PIWI itself, have been genetically implicated in translational regulation (35-37). In addition, MIWI, a mouse homolog of PIWI, binds to piRNAs as well as to the mRNA cap and polysomes, with the polysome association correlating to the translational activity during spermatogenesis (26, 38).

MILI is a murine PIWI protein that we previously reported to be essential for the early prophase of meiosis (39). Most recently, MILI has also been shown to bind to piRNAs (27) and been implicated in transposon control and DNA methylation (28, 40). Here, we show that MILI is a cytoplasmic protein specifically expressed in the germ line during early spermatogenesis. Deleting the mili gene severely affects the self-renewing division and differentiation of germ line stem cells, in addition to its meiotic defects. Furthermore, we provide evidence that MILI positively regulates translation in prepubertal testes that contain only stem cells in the germ line, in contrast to the negative role of AGO proteins and their associated small interfering RNAs and miRNAs. These results suggest a function of MILI in promoting germ line stem cell division and differentiation via translational regulation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibody Generation—The MILI antibody for immunoprecipitation was generated by Anaspec Inc. (San Jose, CA). Amino acid residues 108-122 of MILI were synthesized, purified, and conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin for immunization in rabbits. The resulting antisera were affinity-purified using MILI peptide conjugated to activated immunoaffinity support (Affi-Gel 15; Bio-Rad). The purified antibody was bound to protein A-Sepharose beads (Sigma) for immunoprecipitation. A different antibody, DU-PG15, generated in a guinea pig against a 483-amino acid peptide (52.8 kDa) from bp 1634 to 2117 of the Mili open reading frame, was used for immunostaining and Western blotting.

Immunoprecipitation and Protein Identification—Testicular lysates were prepared as follows. Mice were asphyxiated with CO2, and testes were dissected. The testes were then decapsulated and homogenized in 1 ml of lysis buffer (100 mm KOAc, 0.1% Triton X-100, 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 2 mm MgOAc, 10% glycerol, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 20 units/ml RNaseOut (Invitrogen), 1× complete mini EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science)) in a Dounce homogenizer for 20 strokes. The lysate was adjusted with lysis buffer to 10 mg/ml. Antibody-bound protein A-Sepharose (washed with lysis buffer minus RNAseOUT and protease inhibitor) was added to the adjusted lysate. The mixture was tumbled end over end for 2 h at 4 °C. The beads were then washed, and protein samples were eluted by boiling in 2× SDS sample buffer for 5 min. For the blocking experiment, MILI peptide was added to the beads at a final concentration of 100 μg/ml and incubated for 1 h at 4 °C prior to the addition of lysates. RNase A (Sigma) was added to a final concentration of 10 μg/ml prior to a 2-h, 4 °C incubation. The RNase A-treated sample and other samples were tumbled end over end for an additional 10 min at room temperature to ensure RNase activity. Co-immunoprecipitated MILI-interacting proteins were identified by mass spectrometry at the Proteomics Center at Duke University Medical Center.

RNA in Situ Hybridization and Immunofluorescence Microscopy—RNA in situ hybridization and immunofluorescence microscopy was performed as described by Deng and Lin (41). Affinity-purified polyclonal guinea pig MILI antibody (GP15 against amino acid residues 483-644) was used at 1:15 dilution. Plzf mouse monoclonal antibody from Calbiochem was used at a 1:40 dilution. Human anti-GE-1 serum IC6 from Ref. 42 was used at a 1:200 dilution to recognize GE-1 in cells.

The m7GTP Cap Binding Assay—Testicular extract was prepared as described above and incubated for 2 h at 4 °C with either 60 μl of protein A-Sepharose beads (Sigma) or m7GTP Sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences) in lysis buffer. The beads were then washed, and protein samples were eluted by boiling in 2× SDS sample buffer for 5 min. For the competition experiment, m7GTP was added to the testicular extract to a final concentration of 200 μg/ml and rotated end over end at 4 °C for 1 h prior to incubation with m7GTP-Sepharose.

RNA Isolation and Labeling—RNAs were isolated from the bound fraction of immunoprecipitation using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For small RNA labeling, one-half of the RNA co-immunoprecipitated with MILI from 6 mg of testicular extract was dephosphorylated using calf intestinal phosphatase (New England Biolabs) at 10 units/30-μl reaction in 1× calf intestinal phosphatase reaction buffer at 37 °C for 2 h. The dephosphorylated RNA was then precipitated overnight at -20 °C by ethanol and NaAc, supplemented by Glyco Blue glycogen (Invitrogen). End-labeling of small RNAs was performed using polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs), at 10 units/30-μl reaction, using 2 μl of γ-ATP (6000 Ci/mmol). The reaction was performed in 1× T4PNK buffer at 37 °C for 2 h and terminated by adding 1 μl of 0.5 m EDTA. The sample was then put through a Sephadex G-50 RNA purification column (Roche Applied Science) to remove the unincorporated radioactive nucleotides. Formamide sample buffer was added to one-half of the labeled RNA sample, which was resolved on 15% urea polyacrylamide gel. The signal from labeled small RNAs was visualized via autoradiography. For mRNA labeling, one-half of the extracted RNA from immunoprecipitation was used for first-strand cDNA synthesis using Superscript reverse transcriptase H- (Invitrogen) according to the instructions. Oligo(dT)20 was used as primer, and [α-32P]ATP (3000 Ci/mmol) was used as the labeling source. Samples were resolved on 1% agarose gel, transferred to nylon membrane, and visualized by autoradiography.

Polysome Fractionation—Testicular extract and sucrose gradient fractionation were carried out according to Cataldo et al. (43) with the following modifications. One pair of mouse testes were dissected, decapsulated, and then homogenized in 2 ml of lysis buffer (100 mm NaCl, 3 mm MgCl, 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 0.1% Triton, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 0.2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 20 units/ml RNase Out (Invitrogen)), using 20 strokes in the Dounce homogenizer. The lysates were treated with cycloheximide, a translational elongation inhibitor (44), at a final concentration of 200 μm to stabilize polysomes. The lysate was then centrifuged at 13,000 × g at 4 °C for 2 min. The supernatant was then layered on to the top of a 15-50% (w/w) linear sucrose gradient in the lysis buffer. The gradient was centrifuged in Beckman SW40 rotor for 3 h at 150,000 × g in an SW41 rotor (Beckman). The centrifugation was stopped without applying a break. The fractions were then precipitated using 7.2% trichloroacetic acid (final concentration) and dissolved in SDS sample buffer to 2× final concentration. For micrococcal nuclease experiment, micrococcal nuclease (60 units/ml final concentration; Sigma) was added to the lysate, which is supplemented with 2 mm CaCl2 and incubated at room temperature for 20 min. The reaction was stopped by adding EGTA to a final concentration of 25 mm prior to layering on the sucrose gradient, which was supplemented with EGTA as well.

[35S]Methionine Pulse-Chase Labeling of Protein Synthesis in Seminiferous Tubules—The [35S]methionine metabolic labeling to measure total protein synthesis in wild type or mutant testes was based on the method of Kleene (43, 45). Briefly, seminiferous tubules from 7-day postpartum (dpp) mili+/- or mili-/- testes were dissected in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 1 mm pyruvic acid and 6 mm lactic acid and then transferred to RPMI medium minus methionine. [35S]methionine (20 μCi/ml) was then added, and the tubules were incubated at 32 °C for 30 min. Total proteins were then extracted and precipitated by 20% trichloroacetic acid. The precipitated proteins were then examined on the SDS-polyacrylamide gel to evaluate the quality of labeling and to examine whether the synthesis of specific proteins is significantly changed in the mutant. The total protein synthesis activity was quantified by scintillation counting of the radioactivity of 20% trichloroacetic acid pellet.

Microarray Analysis of the Levels of Total and MILI-associated mRNAs in Wild Type and Mili-/- Mutant—Total RNA from groups of 9-dpp mili+/- or mili-/- testes was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) without any nucleic acid carrier. The high molecular weight RNAs were then further enriched against the low molecular weight RNAs (<200 nucleotides) by selective precipitation in 12.5% polyethylene glycol 8000 and 1.25 m NaCl. The samples were treated with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega) to remove any contaminating DNA and cleaned with RNeasy columns (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The quantity and quality of the RNA samples were evaluated by both spectrophotometry and gel electrophoresis. For the microarray analysis, 10 μg of each sample was reverse transcribed with oligo(dT) primers and SuperscriptII reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). cDNA samples were labeled with Cy3-conjugated nucleotides during the reverse transcription and directly hybridized to a mouse AROS version 3.0 oligonucleotide array (Operon) representing gene transcripts in the mouse. Cy5-labeled oligonulceotides complementary to the probes on the array were externally included in the sample during hybridization as a reference set for initial normalization of the raw data. Likewise, MILI-associated mRNAs were isolated using the TRIzol reagent from the anti-MILI immunoprecipitates from adult (2-4 months old) wild type testicular extract. After one round of amplification with the MessageAmp II RNA amplification kit (Ambion Inc.), the cDNAs were prepared, labeled, and subjected to the microarray chips as above. For the negative control, anti-MILI was blocked with the peptide antigen before applying for immunoprecipitation. The negative control immunoprecipitates were processed and analyzed side by side with the experimental sample in the same way. The same amount and batch of antibodies and extract were used for the negative control as for the experimental sample. The enriched mRNAs in the experimental sample relative to the negative control were dubbed MILI-associated mRNAs, and their expression levels were evaluated in the mili+/- and mili-/- microarray samples. The represented results were derived from five independent replicas for total RNAs from mili+/- and mili-/- and four replicas for MILI-associated mRNAs (reverse transcription, amplification, and hybridization were conducted by the Duke Institute of Genome Sciences and Policy).

Bioinformatic Analysis of Microarray Data—Data on relative abundances of mRNAs within total testicular lysates, MILI immunoprecipitation samples, and mock immunoprecipitation samples were generated as follows. Microarray signals from replicates of total lysates were mean-normalized and averaged, respectively, to generate standard gene expression profiles of mouse testicular tissue. The ratio of the signal of each gene from each MILI immunoprecipitation sample to the standard gene expression profile was then calculated. Based on this ratio, a percentile rank of each gene relative to all genes in each immunoprecipitated replicate was calculated. The percentile ranks in the three replicates of MILI-immunoprecipitated samples were averaged. Student's t test was utilized to determine if the average percentile ranks of enrichment of individual genes were significantly higher (p value) than the mean enrichment of all genes in the immunoprecipitation samples.

To determine the MILI-associated genes, the following criteria were used: 1) average percentile ranks of enrichment were greater than the mean enrichment of all genes in MILI immunoprecipitation with p < 0.01; 2) average signal in MILI immunoprecipitation replicates was significantly greater than the background signal (including 2× S.D.), with background signal and S.D. calculated based on signals from empty spots on each microarray; 3) criterion 1 was not satisfied for the same gene in the corresponding control immunoprecipitation. Using the above criteria, 802 mRNAs were designated as MILI-associated mRNAs. We further compared the expression profiles of MILI-associated mRNAs as well as nonassociated mRNAs in wild type versus mili-/- testis. All cDNA microarray signals were median-normalized. The relative abundances of individual mRNAs from replicates were averaged.

RESULTS

MILI Is Required for Germ Line Stem Cell Self-renewal—We previously reported that mili is required for meiosis (39), which echoes post-germ line stem cell function of piwi and pumilio in the Drosophila ovary (8, 46). Although the mili mutant displays a terminal arrest phenotype at the pachytene stage of meiosis, we notice that only 2 ± 2.5% of the mutant spermatogonia actually reach this stage of differentiation (analysis detailed below), indicating an earlier spermatogenic defect prior to meiosis.

To characterize the early spermatogenic defect, we examined the mutant testes at critical stages of early spermatogenesis. In mouse testes, the precursors of germ line stem cells, called gonocytes, start proliferation at 3 dpp to establish the population of germ line stem cells (also known as primitive Type A spermatogonia) at 6 dpp. These stem cells then undergo self-renewing divisions to produce differentiated Type A spermatogonia (47). To determine whether this defect occurs prior to stem cell formation at 6 dpp, we examined the number and proliferation rate of gonocytes at 5 dpp by immunofluorescence microscopy, using the gonocyte/spermatogonium-specific EE2 antibody (48) to label gonocytes and anti-phosphohistone 3 antibody to label mitotic cells. The mili-/- and mili+/- tubules were similar in size (51.0 ± 4.0 versus 48.1 ± 5.1 μm in diameter) and contained an equivalent number of gonocytes that proliferated at a similar rate (Fig. 1, A and M). This indicates that the mili mutation does not affect gonocyte proliferation. At 8 dpp, the number of spermatogonia in mili-/- and mili+/- tubules remained similar (Fig. 1, C and D), indicating that the germ line stem cell population had been established normally. However, at 8 dpp, the mili-/- germ line stem cells already showed a reduced mitotic rate (2.1 ± 0.40% versus 3.6 ± 0.4%; p < 0.006; Fig. 1M), indicating that spermatogonia division was compromised in the mili mutant.

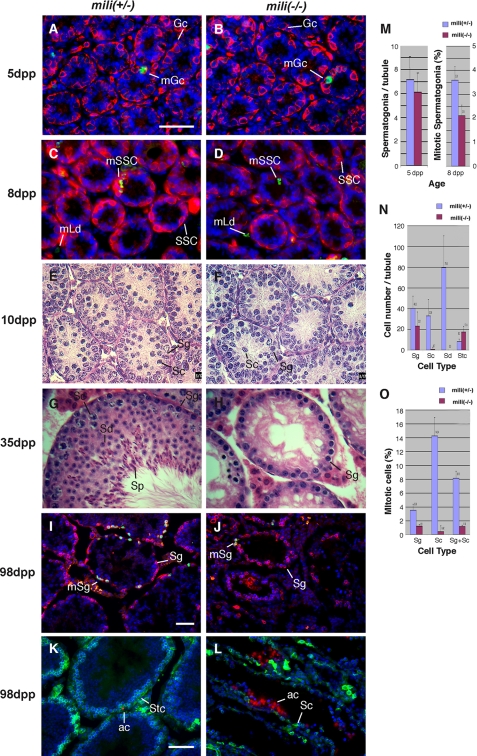

FIGURE 1.

The defect of mili mutant in the self-renewal of spermatogonial stem cells. A-D, testicular sections of 5-day-old (A and B) and 8-day-old (C and D) mili+/- (A and C) and mili-/- (B and D) mice stained with EE2 antibody to outline spermatogonia (red), anti-phosphohistone 3 antibody to label mitotic cells (green), and DAPI to label DNA (blue). The mili+/- and mili-/- testes contain the same number of spermatogonia, as quantified in M, but the mitotic rate in the mili-/- (2.1 ± 0.4%) is noticeably lower than that of mili+/- spermatogonia (3.6 ± 0.4%). Note that all spermatogonia (Sg) at 5 dpp are germ line stem cells. Gc, gonocyte; mGc, mitotic gonocyte; SSC, spermatogonial stem cell; mSSc, mitotic SSC; mLd, mitotic Leydig cells. E-H, hematoxylin/eosin-stained testicular sections of 10-day (E and F) and 35-day (G and H) old mili+/- (E and G) and mili-/- (F and H) mice. Sc, spermatocyte; Sd, spermatid; Sp, sperm. In mili-/- testes, most germ cells are arrested as spermatogonia, with a tiny fraction of germ cells differentiating into spermatocytes. However, no spermatid is detected. This phenotype persists through up to 180 days and was qualified at 98 days in N. I and J, testicular sections of 98-day-old mili+/- (I) and mili-/- (J) mice stained for EE2 (red), phosphohistone 3 (green), and DNA (blue). The mitotic rate of mili-/- spermatogonia is significantly lower than that of the mili+/- spermatogonia, as quantified in O. mSg, mitotic spermatogonia. K and L, testicular sections of 98-day old mili+/- (K) and mili-/- (L) mice stained with BC7 antibody to mark spermatocytes (green) and terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling to mark apoptotic cells (ac; red) and DNA (blue). Stc, Sertoli cell. Note that drastic apoptosis occurs in the arrested mili-/- germ cells. Bars in A, I, and K denote 50 μm for A-H, I and J, and K and L, respectively. M-O, quantitative comparisons between mili+/- and mili-/- testes with regard to the number of spermatogonia per tubule at 5 dpp (M) and 98 dpp (N), and mitotic index of spermatogenic cells at 8 dpp (M) and 98 dpp (O).

We then investigated the effects of the mili mutation on spermatogonial division and differentiation at representative stages of postnatal development. At 10 dpp, mili+/- spermatogonia underwent active divisions and started to produce spermatocytes (Fig. 1E and Fig. S1A), yet mili-/- spermatogonia became further reduced in division rate (Fig. 1F and Fig. S1B). By 35 dpp, mili+/- spermatogonia had extensively proliferated to generate a complete complement of spermatogenic cells, resulting in drastically enlarged tubules (Fig. 1G and Fig. S1C). In contrast, mili-/- spermatogonia were mostly arrested in mitosis and differentiation and only occasionally produced early spermatocytes (Fig. 1H and Fig. S1D). By 98 dpp, wild type testes contained 32.9 ± 12.2 spermatocytes/tubule, whereas the mili mutant testes only contained 0.7 ± 1.5 spermatocyte/tubule, 47-fold fewer than the wild type situation (Fig. 1N). No spermatid was ever observed (Fig. 1N). The identities of these spermatocytes were confirmed by staining with the spermatocyte-specific antibody BC7 (Fig. S2, E and F). Furthermore, as we previously reported (39), these spermatocytes are arrested at zygotene and pachytene stages, as judged by the characteristic morphology of their chromosomes (Fig. S1D). The defects in spermatogonial division and differentiation persisted through 52 dpp (Fig. S1, E and F), 63 dpp (Fig. S2, C-F), and 98 dpp (Fig. 1, I and J, quantified in Fig. 1, N and O), without any loss of Sertoli cells or interstitial cells (Fig. 1N and Fig. S1, C-F). Along this time line, the arrested mutant spermatogonia increasingly underwent apoptosis (Fig. 1, K and L), so that most tubules were depleted of spermatogonia by 180 dpp, resulting in a Sertolionly phenotype (Figs. S1 (G and H) and S2 (G-J)). These defects clearly indicate that mili mutant spermatogonial stem cells are blocked in both proliferation and differentiation. Thus, MILI is essential for the self-renewing division of these stem cells.

MILI Is Expressed in Gonocytes, Spermatogonia, and Early Spermatocytes—To examine whether MILI is directly involved in germ line stem cell functions, we examined the expression of mili during germ line development. We first conducted Northern analysis of mili expression in adult tissues. mili RNA was detectable as a 3.7-kb mRNA in the testis but not in other tissues (Fig. 2A), consistent with its spermatogenesis-specific phenotype. To further investigate the expression of mili during spermatogenesis and germ line development, we examined the expression of mili mRNA in embryonic gonads and adult testes. mili was expressed in primordial germ cells starting at 12.5 days post coitum in sexually dimorphic male and female gonads (Fig. 2, B and C). At 13.5 days post coitum, when primordial germ cells in the male and female gonad further differentiate into gonocytes and oocytes, respectively (49), mili expression became stronger in both male and female gonads (Fig. 2, D and E). In the testis, mili was expressed in all cells in the testicular cord, with strong expression in centrally located gonocytes and weak expression in the basally located Sertoli cells in the cord (Fig. 2D). During subsequent fetal development, mili expression persisted at this high level in the male gonad (Fig. 2F) but was abolished in the female gonad (Fig. 2G). This reduction of mili expression in the female gonad correlates with the entry of female primordial germ cells into meiosis at 13.5 days post coitum. In adult mice, mili was not expressed in the ovary but was strongly expressed in the testis at the basal and sub-basal layers of the seminiferous epithelium, where spermatogonia and primary spermatocytes reside (Fig. 2, H and I). This expression pattern suggests that mili is probably involved in early spermatogenesis, from spermatogonial stem cell division to early meiosis.

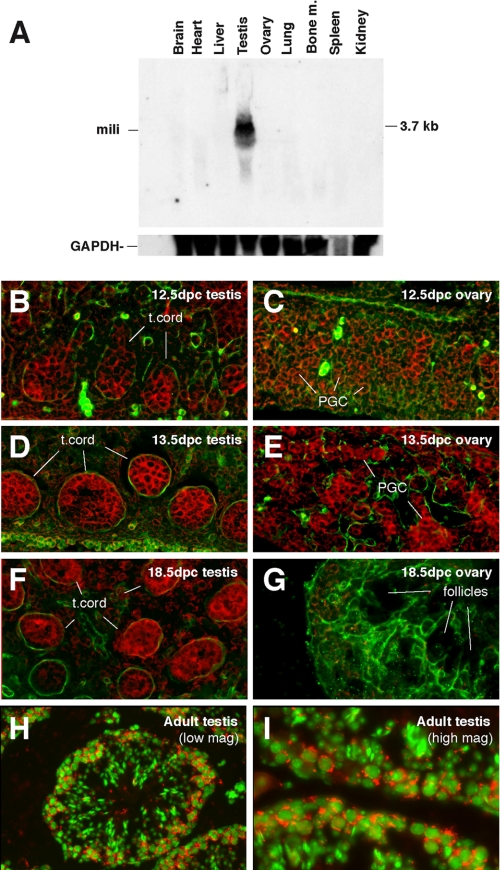

FIGURE 2.

The expression of mili mRNA during mouse germ line development. A, a Northern blot containing total RNAs prepared from various adult tissues as indicated and probed for the mili mRNA. B-I, in situ mili RNA hybridization of embryonic and adult testes and ovaries at specific stages as indicated. Red, mili mRNA; green in B and G, laminin, which outlines testicular cord (t. cord) in B, G, and F; green in H and I, DNA (stained with DAPI).

To examine the expression of MILI protein, we generated an anti-MILI antibody that specifically recognizes MILI but not its homologs, as evident by Western blot analysis (Fig. S3; also see “Experimental Procedures”). Immunofluorescence staining of adult mouse testicular sections using this antibody revealed that MILI was specifically expressed in the cytoplasm of spermatogonia and pachytene stage spermatocytes but not in more differentiated germ cells (Fig. 3, A and B), similar to the mili mRNA expression pattern (Fig. 2, H and I). MILI expression was not detectable in Sertoli cells, which can be readily identified either by their expression of the Tsx antigen (Fig. 3C) or by their distinct chromatin morphology as visualized by the DNA dye DAPI (Fig. 3, C and E). In the germ line cytoplasm, MILI is enriched in spherical structures, most of which contain the Ge-1 protein, a marker for the chromatoid body and nuage, perinuclear structures related to the P-body of somatic cells, and was proposed to serve as an RNA storage and processing center (Fig. 3D) (38, 50), yet a small number of MILI-enriched spheres do not have Ge-1, and vice versa. The chromatoid body/nuage localization of MILI resembles that of MIWI (38), suggesting that MILI might be involved in mRNA storage and processing.

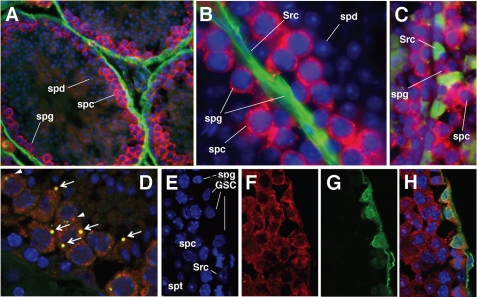

FIGURE 3.

The expression of MILI protein in adult testes. A and B, low and high magnification views, respectively, of MILI (red) expression in seminiferous tubules. DNA is stained with DAPI (blue), whereas the basal lamina that outlines the tubules are stained by the laminin antibody (green). spg, spermatogonia; spc, spermatocytes; spd, spermatids; Src, Sertoli cells. C, a magnified view of two adjacent tubules with only the basal and subbasal layers of the seminiferous epithelium shown. MILI (red) is expressed in spermatogenic cells but not in Sertoli cells (Src; green, as labeled by the Tsx antibody). D, MILI (red) and Ge-1 (green) double staining, showing that most MILI spheres also contain Ge-1 (arrows), whereas only a few MILI spheres do not have Ge-1 (arrowhead). E-H, high magnification views of seminiferous epithelium triple-stained for DNA (E), MILI (F), and germ line stem cell-specific protein Plzf (G). The merged image (H) indicates that MILI is present in all spermatogonia, including all of the germ line stem cells.

Since germ line stem cells are a subset of spermatogonia, the expression of MILI in all spermatogonia indicates that it is expressed in germ line stem cells. This was confirmed by the colocalization of MILI with Plzf, a germ line stem cell marker (Fig. 3, E-H) (5, 6). To examine whether MILI is expressed in germ line stem cells as soon as they are established, we conducted Western blot analysis on protein extracts from 4-, 6-, 8-, and 10-dpp testes. Since MILI was expressed at all these time points (Fig. S4A), yet MILI expression was germ line-specific (Fig. 3, B and C), this suggests that MILI is expressed in gonocytes (4 dpp), newly formed germ line stem cells (6 dpp), differentiating spermatogonia (8 dpp), and possibly leptotene spermatocytes (10 dpp). This result is also consistent with the detection of mili mRNA in embryonic gonocytes, adult germ line stem cells, spermatogonia, and primary spermatocytes but not in somatic cells (Figs. 2 and 3). The germ line-specific expression of MILI implicates that the function of MILI in germ line stem cell division and meiosis is cell-autonomous.

MILI Associates with Polysomes in an RNA-dependent Manner—To understand how MILI regulates spermatogonial division and differentiation, we explored the biochemical role of MILI. Recent works have shown that two Argonaute subfamily members, human eIF2C2 (also known as Ago2) and trypanosome TbAGO, associate with polysomes and, in the case of AGO2, stimulate translation (25, 51, 52). Moreover, we have shown that MIWI, a close homolog of MILI, is a cytoplasmic protein associated with polysomes in a manner correlated to active translation (26, 38). Since MILI is also a cytoplasmic protein, these reports raised the possibility that MILI may be involved in translational regulation. To explore this possibility, we first performed sucrose gradient fractionation of adult testicular lysates to examine if MILI co-fractionates with monosomes and/or polysomes (see “Experimental Procedures”). Testicular lysates displayed prominent polysome profiles, reflecting active translation (Fig. 4A). As expected, MILI co-sedimented not only with RNP fractions (fractions 1 and 2; Fig. 4A), which contain chromotoid body components, as we have previously shown (38), but also with polysome fractions (fractions 10-15; Fig. 4A), similar to MIWI (38).

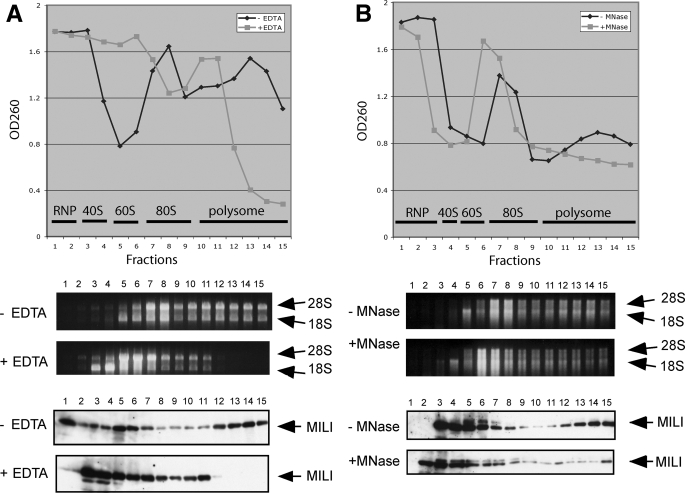

FIGURE 4.

A subpopulation of MILI is associated with polyribosomes. Sucrose density gradient analysis of adult mouse testicular extracts, with and without EDTA and micrococcal nuclease (MNase) treatment. Absorbance at 260 nm indicates the polyribosome profile. The presence of polysomes in various fractions was verified by the presence of 28 and 18 S rRNAs in the corresponding fractions. MILI in individual fractions was detected by Western blot analysis. A, effect of EDTA treatment. B, effect of micrococcal nuclease treatment.

To determine whether the co-sedimentation of MILI with polysome fractions is due to unrelated co-migration or reflects true association between MILI and polysomes, we added EDTA to chelate Mg2+ required for polysome assembly. EDTA eliminated large polysome fractions (fractions 11-15; Fig. 4A). Correspondingly, MILI disappeared in these fractions (Fig. 4A). Instead, MILI was mostly concentrated in the monosome and subunit fractions (fractions 3-9); very little was in the RNP fractions (fractions 1 and 2), where chromatoid body components are most abundantly segregated under this condition (38). To further eliminate the possibility that MILI co-migrates with polysomes in other EDTA-sensitive complexes, we treated the lysates with micrococcal nuclease, which digested mRNAs and reduced some polysomes to monosomes (Fig. 4B). Correspondingly, MILI in the polysome fractions was also reduced. These analyses indicate that the co-sedimentation of MILI with polysome reflects its association with polysomes.

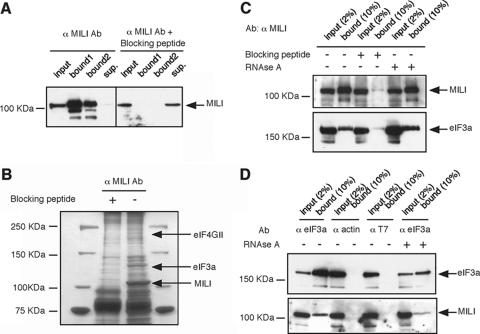

MILI Interacts with eIF3a and eIF4G—To further investigate the role of MILI association with polysomes, we used co-immunoprecipitation to search for specific components of the translational machinery that interact with MILI. We first developed a new rabbit antibody that specifically recognizes and precipitates endogenous full-length MILI from mouse testicular extracts (Fig. 5A; also see “Experimental Procedures”). This immunoprecipitation was not seen for mili mutant lysate (Fig. 6B) and was completely blocked by adding the antigen-peptide (Fig. 5A). Proteins co-immunoprecipitated with MILI were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gels and silver-stained (Fig. 5B). Bands that were present only in the co-immunoprecipitant without the blocking peptide were excised from the gel and analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (see “Experimental Procedures”). We identified two major MILI-associated proteins as eukaryotic translational initiation factors eIF4GII and eIF3a (Fig. 5B). The eIF4GII protein migrated at the expected size, whereas eIF3a migrated at 122 kDa, smaller than its reported molecular mass of 170 kDa (53).

FIGURE 5.

MILI interacts with eIF3a. A, purified anti-MILI peptide antibody (Ab) efficiently immunoprecipitates (bound) MILI from a testicular extract. Adding the antigen-peptide blocks the precipitation. B, eIF3a is specifically co-precipitated by with MILI, as revealed by mass spectrometry. C, Western blot showing that the MILI antibody co-immunoprecipitated MILI and eIF3a from a testicular extract. Adding the blocking peptide almost completely prevented the immunoprecipitation of both MILI and eIF3a. However, adding RNase A did not disrupt the co-precipitation. D, Western blot showing that the eIF3a antibody, but not actin or T7 antibodies, specifically co-precipitated eIF3a and MILI from a testicular extract. Adding RNase A did not disrupt the co-precipitation.

FIGURE 6.

MILI is associated with the cap-binding complex, poly(A)+ RNAs, and piRNAs. A, MILI protein co-purifies with components of the cap-binding complex from the testicular extract by the m7GTP-Sepharose (lane 3) but not with protein A-Sepharose (lane 2). The interaction is disrupted when m7GTP was added to the testicular extract prior to incubation with the m7GTP Sepharose as a competitor (lane 4). B, a heterogenous population of poly(A)+ RNAs ranging from 0.5 to 4 kb are present in the MILI-immunoprecipitated complex, as detected by oligo(dT)-primed reverse transcription. C, abundant piRNAs are also present in the MILI-immunoprecipitated complex, as detected by direct 5′-end labeling of RNAs extracted from the MILI-immunoprecipitated complex.

To verify the eIF3a-MILI interaction, we used an anti-eIF3a antibody to probe a Western blot of the MILI co-immunoprecipitant (Fig. 5C). The antibody detected an abundant presence of eIF3a in the co-immunoprecipitant at the expected size of 170 kDa (Fig. 5C). The addition of the blocking peptide drastically reduced eIF3a in the co-immunoprecipitant to an almost undetectable level (Fig. 5C). The eIF3a-MILI interaction was further confirmed by reciprocal co-immunoprecipitation of the testicular extract using the anti-eIF3A antibody. MILI was specifically co-immunoprecipitated by the eIF3a antibody but not by actin or T7 antibodies, as indicated by Western blot analysis (Fig. 5D). Thus, eIF3A interacts with MILI in the same protein complex. The smaller size of eIF3a in the mass spectrometry sample is presumably due to the breakdown of the 170-kDa protein into a 122-kDa fragment during the sample preparation for electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. The MILI-eIF4GII interaction was further verified by co-immunoprecipitation in the m7GTP cap-binding complex, as described below.

To examine whether the association between MILI and eIF3a is mediated by RNA, we treated the testicular extract with RNase A prior to co-immunoprecipitation by either MILI antibody or eIF3a antibody. RNase A treatment caused complete RNA degradation, as assessed by visualization of rRNA by ethidium bromide on agarose gel (data not shown). However, the association between MILI and eIF3a was still maintained (Fig. 5, C and D). These results indicate that MILI and eIF3A form a complex in vivo in an RNA-independent manner.

To examine whether MILI-eIF3a-eIF4GII interaction occurs in germ line stem cells, we examined the expression of MILI, eIF3a, eIF4GII, and ribosomal protein S6, another key component of the translational initiation complex in 6-dpp testes, which contain only nascent stem cells in the germ line, and 8-dpp testes, which contain only germ line stem cells and early type A spermatogonia in the germ line, by Western blotting analysis. MILI, eIF3a, eIF4GII, and ribosomal protein S6 were all present in the 6- and 8-dpp testicular extracts (Fig. S4A). Moreover, MILI-eIF3a interaction was detected at 8 dpp, the time point we examined (Fig. S4B). These results suggest the likely association between MILI and eIF3a as well as between MILI and eIF4GII in germ line stem cells and early type A spermatogonia.

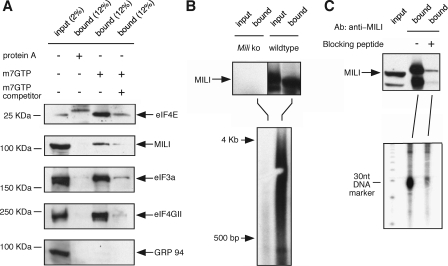

MILI Is Associated with m7GTP Cap-binding Complex, Poly(A)+ mRNA, and piRNA—The interaction between MILI and eIF3a suggests that MILI may regulate translational initiation at an early step, possibly when the eIF3a-containing preinitiation complex binds to the mRNA m7GTP cap prior to mRNA scanning. To explore this possibility, we performed an m7GTP cap binding assay to test if MILI is associated with the cap-binding complex. Testicular extracts were incubated with m7GTP-cap analog conjugated to Sepharose beads, and the bound fraction was analyzed by Western blot. The m7GTP-Sepharose specifically co-purified the cap-binding complex components eIF4E, eIF4GII, and eIF3a, as well as MILI (Fig. 6A). The association of MILI and the eukaryotic initiation factors with m7GTP-conjugated Sepharose is specific, since these proteins did not bind to protein-A-conjugated Sepharose (Fig. 6A); nor did GRP 94, a chaperone protein, bind to the m7GTP-Sepharose (Fig. 6A).

To further test the specificity of MILI association with the cap-binding complex, a m7GTP-cap analog was added to the testicular extract to a final concentration of 200 μg/ml to compete with the interaction between the cap-binding complex and the Sepharose-conjugated m7GTP moiety. This addition drastically reduced the association of eIF4E, eIF3a, and eIF4GII as well as MILI with the m7GTP-Sepharose beads (Fig. 6A, fourth lane), indicating that MILI is associated with cap-binding complex in a specific manner. Since we were unable to observe the interaction between MILI and eIF4e, eIF2a, or eIF4GII by MILI co-immunoprecipitation (data not shown), the association between MILI and the cap-binding complex is probably through the association between MILI and eIF3a.

The association of MILI with the translational initiation complex predicts that MILI is also associated with mRNAs. To investigate this possible association, we searched for the presence of polyadenylated mRNAs in the MILI-co-immunoprecipitated complexes by reverse transcription, using oligo(dT) primers (see “Experimental Procedures”). Radioactively labeled cDNA products were then fractionated by gel electrophoresis. Many poly(A)+ RNA species ranging from 0.5 to 4 kb in size were co-immunoprecipitated with MILI from the wild type but not mili mutant testicular lysate (Fig. 6B). This suggests that MILI is probably associated with many mRNAs in the testis. Under the same immunoprecipitation conditions, we also detected abundant association of piRNAs with MILI, as previously reported (Fig. 6C). These results point to the enticing possibility that some piRNAs are involved in translational regulation.

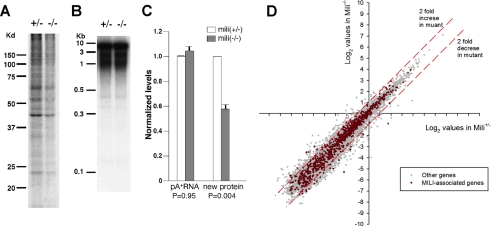

mili Mutant Testes Display Globally Reduced Translational Activity—To assess the function of MILI in translation, we performed [35S]methionine metabolic labeling to measure total protein synthesis in seminiferous tubules isolated from 7-dpp wild type versus mili mutant testes, based on the method of Kleene (43, 45) (see “Experimental Procedures”). We chose 7 dpp, because both wild type and mili mutant testes contain mostly, if not exclusively, stem cells in the germ line at this stage (Fig. 1 and Figs. S1 and S2). In addition, the mutant testes are phenotypically similar to the wild type testes at this time point, and both contain ∼80% germ line stem cells and only 20% Sertoli cells within seminiferous tubules (Fig. 1 and Figs. S1 and S2). Hence, by isolating seminiferous tubules, we eliminated extratubular somatic cells, thus allowing our measurements to reflect largely the status of protein synthesis in germ line stem cells yet under a physiologically normal condition that could not be achieved if we used isolated germ line stem cells (43, 45).

We pulse-labeled the isolated seminiferous tubules with [35S]methionine for just 30 min at 32 °C to allow the labeling of only nascent peptides. Total proteins were then extracted and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Protein synthesis occurs robustly in isolated wild type tubules, yet there is a decrease in the synthesis of many protein bands in the mutant tubules (Fig. 7A). To quantify the decrease in total protein synthesis, we performed scintillation counting on the radioactivity of trichloroacetic acid (20%)-precipitated protein samples from mili+/- or mili-/- testes to measure the total levels of protein synthesis. The experiments were repeated twice with independent samples. The variation among the three different experiments of either mili+/- or mili-/- testes were negligible (Fig. 7C). However, the total protein synthesis in mili-/- testes was consistently decreased to 59% of the mili+/- control level (Fig. 7C). This decrease is statistically highly significant (p = 0.004), indicating that global protein synthesis is reduced in the mili mutant.

FIGURE 7.

Comparison of mili+/- and mili-/- seminiferous tubules for translational activity. A, gel separation of 35S-labeled proteins precipitated by 20% trichloroacetic acid, indicating the rate of protein synthesis in mili+/- and mili-/- testes. B, gel separation of oligo(dT)-primed reverse transcription-PCR product, indicating the abundance and distribution of poly(A)+ RNAs in mili+/- and mili-/- testes. C, quantification of total levels of poly(A)+ RNAs and rate of synthesized proteins in mili+/- and mili-/- testes. n = 3. D, the scatter plot of the expression profiles of mRNAs in mili+/- and mili-/- testes interrogated by cDNA microarray analysis. The expression levels of 802 MILI-associated mRNAs are shown in red, whereas the expression levels of the remaining 14,845 non-MILI-associated mRNAs are shown in gray. All values are in log2 scale. The red dashed lines indicate the borders for 2-fold difference.

To determine whether the decreased protein synthesis is due to decreased levels of mRNAs in the mutant, we first quantified the total poly(A)+ mRNA in 24-dpp mili+/- and mili-/- testes by isolating total RNA and reverse transcribing poly(A)+ mRNA into 32P-labeled cDNA using oligo(dT) primers. The reason for choosing 24 dpp is that it was difficult to collect a sufficient amount of RNAs from the tiny 7-dpp testes, yet the mili mutant displays a clear phenotype at 24 dpp, thus providing a more stringent first evaluation. Electrophoretic examination of the resulting cDNAs indicated the success of the reverse transcription and purification procedure (Fig. 7B). Scintillation quantification of the cDNAs, again repeated twice with independent samples, indicated that mili+/- or mili-/- testes contain very similar levels of mRNAs.

We then further investigated whether the levels of individual mRNAs are changed in the mili mutant, especially whether there is an increase in retrotransposon mRNAs that compensates for a decrease in the “regular” transcripts, given the role of mili in transposon silencing (28, 40). Our previous Affymetrix GeneChip analysis revealed that most mRNAs, including transposon mRNAs, are not changed (40). Only five IAP retrotransposon genes are up-regulated more than 3-fold. To confirm this result and to further quantify mRNAs for the change of their expression in the mili mutant, we compared the expression of 15,647 genes in the 9-dpp mili+/- and mili-/- mice, using an AROS version 3.0 oligonucleotide array (Operon; see “Experimental Procedures”). Among these genes, only 365 showed a greater than 2-fold decrease in expression in mili-/- mice, representing a 0.65% decrease in the total mRNA pool (Fig. 7D). Likewise, only 381 genes showed a greater than 2-fold increased expression in mili-/- mutants, representing a 0.3% increase in the total RNA. The net change in the mRNA pool is only a 0.35% decrease. These results further indicate that the levels of most individual mRNAs are not affected in the mili mutant. We then further examined whether MILI-associated mRNAs are somewhat more affected than nonassociated mRNAs by co-immunoprecipitation of MILI and its associated mRNAs from the adult mili+/- or mili-/- testicular extract, followed by extraction of the MILI-associated mRNAs and quantification of their expression by an AROS version 3.0 oligonucleotide array (Operon). Again, of the 802 MILI-associated mRNAs that we detected, only 21 genes showed a greater than 2-fold decrease of expression in the mili-/- mutant, and only 23 genes showed a greater than 2-fold increased expression in the mili-/- mutant (Fig. 7D; see “Experimental Procedures”). Thus, by all of these criteria, the reduction of global protein synthesis in mili mutant seminiferous tubules reflects a novel and probably positive role of MILI in translational regulation.

DISCUSSION

MILI Is Essential for Germ Line Stem Cell Self-renewal and Differentiation—Although the piwi/ago gene family was first discovered for its function in stem cell self-renewal (21), such a function has not been demonstrated in any vertebrate system. Zebrafish PIWI (ZIWI) prevents excessive apoptosis in the germ line but not germ line stem cell division (54). The disruption of ago2 in mice leads to embryonic lethality early in development after the implantation stage (55). Among three murine PIWI proteins, MIWI is a key regulator of spermiogenesis (41); whereas MIWI2 is predominantly involved in meiosis and transposon control (32). Our previous work identified a function of MILI in meiosis (39). The earlier and essential function of MILI in germ line stem cell self-renewing division and differentiation reported here extends the stem cell function of the PIWI/AGO protein family to vertebrate systems.

This stem cell function of MILI is unique in that it is required for both self-renewal and differentiation, which is different from other known germ line stem cell genes. Plzf mutant mice produce a limited number of sperm but progressively lose their germ line afterward (5, 6), suggesting that Plzf is only required for self-renewal and not for differentiation. On the other hand, c-Kit and stem cell factor are only required for the differentiation of spermatogonia and not for self-renewal (2, 3). Sox3 appears to be a survival factor for germ line stem cells, since Sox3-deficient mice begin to lose germ cells as early as at 10 dpp (7). By 14 dpp, Sox3 null mice are nearly germ lineless. The dual function of MILI in controlling both the self-renewal and differentiation of germ line stem cells is reminiscent of that of PIWI, which affects both the self-renewal of germ line stem cells and sometimes the differentiation of their progeny in Drosophila (46), although the differentiation function of PIWI has not been extensively characterized.

In mili mutants, the escape of ∼2% of spermatogonia from differentiation block (see “Results”) has provided an opportunity to identify its subsequent function during early meiosis (39). The function of MILI in germ line stem cells and prophase spermatocytes matches nicely with its expression pattern during development.

MILI Represents a Novel Mechanism That Appears to Positively Regulate Translation—Recent advancements in noncoding small RNA research have shed light on the crucial role of PIWI/Argonaute proteins and miRNAs in diverse biological processes. Argonaute subfamily proteins have been implicated in small interfering RNA-mediated mRNA degradation, epigenetic silencing, and miRNA-mediated translational repression, all of which negatively regulate gene expression. Likewise, PIWI proteins have been shown to participate in the transcriptional and post-transcriptional transgene silencing as well as epigenetic regulation in various organisms (33, 34, 56-59). Particularly, MILI itself has been implicated in repressing DNA methylation and transposition (28, 40). Although a very small number of MILI molecules might exit in the nucleus for these functions, the cytoplasmic localization of MILI suggests that MILI may indirectly regulate these nuclear events. Our results suggest that MILI positively regulates the translation of many, if not all, genes during early spermatogenesis. Some of the MILI target genes could in turn regulate epigenetic state and repress transposition. Furthermore, our microarray analyses show that the increase of IAP retrotransposon RNAs reflects a minor change in the total levels of retrotransposon mRNAs, which had little impact on the total mRNA level in the mili mutant. In fact, the increased IAP mRNAs in the mili mutant should further contribute to the synthesis of the total pools of proteins that we measured.

The overall magnitude of the impact of MILI on translation is 2-fold, which is a value averaged over all cellular mRNAs, including mRNAs that are targets of MILI regulation. It is therefore conceivable that the effect of MILI toward its target mRNAs or a subset of them could be much higher than 2-fold. Although MILI might achieve this broad range positive regulation by repressing the translation of a small number of translational repressors that subsequently inhibit the translation of many other mRNAs in the cell, this scenario, even if it exists, is unlikely to be a major mode of regulation, given that MILI appears to bind directly to many mRNAs (Fig. 6B). The direct positive role of MILI in translational regulation is supported by the strong correlative evidence for a similar role of MIWI, since MIWI also directly complexes with its target mRNAs (41) and becomes increasingly associated with polysomes as translational activity increases in spematogenic cells (38).

Translational regulation by MILI appears to represent a novel mechanism-positive regulation by a PIWI protein at the initiation stage. In contrast, AGO proteins mediate miRNA-related translational repression that targets the 3′-untranslated region of mRNA. It has been suggested by several groups that this can cause early ribosome exit of repressed mRNAs and/or deadenylation of these mRNAs. It has also been reported that AGO proteins could subject substrate mRNAs to translational inhibition when miRNA-like small RNAs are used as targeting effectors (60) and that miRNA-dependent translational repression could interrupt translation initiation (61, 62). However, these effects on translational initiation are negative. It has recently been reported that AGO2 can up-regulate translation, but that is via the AU-rich element in the 3′-untranslated region rather than the cap (25). The function of MILI is probably different from all of the above mechanisms. It appears to promote translation via the preinitiation complex and the mRNA cap. Particularly, MILI interacts with eIF3a in an RNA-independent manner. eIF3a is the largest subunit of the eIF3 complex. In mammals, eIF3 binds to the 40 S ribosomal subunit prior to the recruitment of 5′ m7GTP-capped mRNA. This recruitment is necessary to initiate translation and is accomplished via the interaction between eIF3a and the eIF4F complex, which binds the m7GTP-cap via the eIF4E subunit (63). Our finding that MILI is associated with both the cap-binding complex and poly(A)+ RNAs is consistent with this hypothesis. The fact that MILI is also associated with polysomes suggests that the function of MILI is coupled with both the recruitment of the capped mRNA and the formation of polyribosomes on the mRNA.

MILI Regulates the Translation of Germ Line Stem Cells—MILI probably regulates translation in germ line stem cells, since MILI interacts with the components of the translational initiation complex in 8-dpp testes that contain mostly germ line stem cells and a small number of early type A spermatogonia (Fig. S4). Furthermore, translational activity is reduced in 7-dpp mili mutant seminiferous tubules, which contain mostly germ line stem cells and a small number of Sertoli cells. In addition to regulating germ line stem cells, MILI may regulate translation in gonocytes, other spermatogonia, and early spermatocytes, as implicated by its expression pattern and phenotype. These roles of MILI highlight the importance of translational regulation in germ line stem cell maintenance, mitosis, and meiosis. For example, the translational repressors NOS and PUM are essential for maintaining the fate of germ line stem cells in Drosophila, presumably by repressing the translation of differentiation genes (8-10). Consistent with this notion, the translational control of cyclin B is essential for the progression of cells through mitosis and meiosis (64). In addition, the requirement of eIF3 and eIF5 in meiosis has been demonstrated in C. elegans (65). The identification of MILI-target mRNAs should reveal aspects of cellular processes in spermatogenesis that are regulated by MILI.

Does MILI Regulate Translation via piRNAs—Although MILI is associated with the translational initiation factors, mRNAs, and piRNAs, without definitive data indicating one-to-one correspondence at the single-molecule level, it is not clear whether MILI-mediated translational regulation involves piRNAs. It has been reported that ZIWI-associated piRNAs are localized in the cytoplasm (54). Moreover, MIWI-associated piRNAs are present in the polysome fraction, and MIWI is also associated with the cap (38). Extensive and systematic effort is required to demonstrate whether some piRNAs are involved in translational regulation mediated by PIWI family proteins.

MILI in Chromatoid Bodies; a Function in RNA Sequestering?—The presence of MILI in both the nuage/chromatoid body and the free cytosol is consistent with its two-phase distribution between RNP and ribosomal fractions in sucrose gradients (Fig. 4). Our previous study of MIWI has demonstrated that RNP fractions contain chromatoid body components, yet ribosomal fractions contain cytoplasmic MIWI (38). Chromatoid bodies resemble P-/GW-bodies in somatic cells that are implicated in small RNA-mediated mRNA degradation (60, 66-68). However, MIWI is required for the stability of its target mRNAs as well as for the integrity of the chromatoid body (41, 69). Thus, the stabilization function of MIWI might be related to the chromatoid body. If so, this germ line organelle would have a function opposite to its somatic counterpart; it would sequester and protect mRNAs rather than degrade them. The observed MILI/Ge-1 co-localization in spermatocytes suggests that MILI is also a component of the P-/GW-bodies. In addition, the presence of a small number of MILI-enriched spheres that share the size and morphology of chromatoid bodies but lack Ge-1 further suggests the existence of at least two distinct types of P-body-like structures in the germ line. The role of chromotoid body-associated MILI in mRNA stability control was not tested here, since this study focuses on the effect of MILI on germ line stem cells in 6-8-dpp testes, which do not contain chromotoid bodies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Yuna Kim for mili RNA in situ hybridization and generating GP15 MILI antibody, Priyanka Bhattacharya for mili Northern blot analysis, Vivian Lui for verifying the specificity of GP15 antibody, and members of the Lin laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant HD42012. This work was also supported by a grant from the Connecticut Stem Cell Research Foundation (to H. L.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1-S4.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: miRNA, micro-RNA; piRNA, PIWI-interacting RNA; dpp, day(s) postpartum; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

References

- 1.Lin, H. (2004) in Stem cell Handbook (Sell, S., ed) pp. 57-74, Humana Press, Inc., Totowa, NJ

- 2.de Rooij, D. G., Okabe, M., and Nishimune, Y. (1999) Biol. Reprod. 61 842-847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohta, H., Tohda, A., and Nishimune, Y. (2003) Biol. Reprod. 69 1815-1821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meng, X., Lindahl, M., Hyvonen, M. E., Parvinen, M., de Rooij, D. G., Hess, M. W., Raatikainen-Ahokas, A., Sainio, K., Rauvala, H., Lakso, M., Pichel, J. G., Westphal, H., Saarma, M., and Sariola, H. (2000) Science 287 1489-1493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buaas, F. W., Kirsh, A. L., Sharma, M., McLean, D. J., Morris, J. L., Griswold, M. D., de Rooij, and Braun, R. E. (2004) Nat. Genet. 36 647-652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costoya, J. A., Hobbs, R. M., Barna, M., Cattoretti, G., Manova, K., Sukhwani, M., Orwig, K. E., Wolgemuth, D. J., and Pandolfi, P. P. (2004) Nat. Genet. 36 653-659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raverot, G., Weiss, J., Park, S. Y., Hurley, L., and Jameson, J. L. (2005) Dev. Biol. 283 215-225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parisi, M., and Lin, H. (1999) Genetics 153 235-250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang, Z., and Lin, H. (2004) Science 303 2016-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilboa, L., and Lehmann, R. (2004) Curr. Biol. 14 981-986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ciosk, R., DePalma, M., and Priess, J. R. (2004) Development 131 4831-4841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giorgini, F., Davies, H. G., and Braun, R. E. (2002) Development 129 3669-3679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beamer, W. G., Cunliffe-Beamer, T. L., Shultz, K. L., Langley, S. H., and Roderick, T. H. (1988) Biol. Reprod. 38 899-908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rohozinski, J., and Bishop, C. E. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101 11695-11700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dragon, F., Gallagher, J. E., Compagnone-Post, P. A., Mitchell, B. M., Porwancher, K. A., Wehner, K. A., Wormsley, S., Settlage, R. E., Shabanowitz, J., Osheim, Y., Beyer, A. L., Hunt, D. F., and Baserga, S. J. (2002) Nature 417 967-970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruggiu, M., Speed, R., Taggart, M., McKay, S. J., Kilanowski, F., Saunders, P., Dorin, J., and Cooke, H. J. (1997) Nature 389 73-77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collier, B., Gorgoni, B., Loveridge, C., Cooke, H. J., and Gray, N. K. (2005) EMBO J. 24 2656-2666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reynolds, N., Collier, B., Maratou, K., Bingham, V., Speed, R. M, Taggart, M., Semple, C. A, Gray, N. K., and Cooke, H. J. (2005) Hum. Mol. Genet. 14 3899-3909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin, H. (2007) Science 316 397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beyret, E., and Lin, H. (2007) in MicroRNAs: From Basic Science to Disease Biology (Appasani, ed) pp. 497-511, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- 21.Cox, D. N., Chao, A., Baker, J., Chang, L., Qiao, D., and Lin, H. (1998) Genes Dev. 12 3715-3727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reddien, P. W., Oviedo, N. J., Jennings, J. R., Jenkin, J. C., and Sanchez Alvarado, A. (2005) Science 310 1327-1330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Batista, P. J., Ruby, J. G., Claycomb, J. M., Chiang, R., Fahlgren, N., Kasschau, K. D., Chaves, D. A., Gu, W., Vasale, J. J., Duan, S., Conte, D., Jr., Luo, S., Schroth, G. P., Carrington, J. C., Bartel, D. P., and Mello, C. C. (2008) Mol. Cell 31 67-78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang, G., and Reinke, V. (2008) Curr. Biol. 18 861-867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vasudevan, S., and Steitz, J. (2007) Cell 128 1105-1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grivna, S. T., Beyret, E., Wang, Z., and Lin, H. (2006a) Genes Dev. 20 1709-1714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aravin, A., Gaidatzis, D., Pfeffer, S., Lagos-Quintana, M., Landgraf, P., Iovino, N., Morris, P., Brownstein, M. J., Kuramochi-Miyagawa, S., Nakano, T., Chien, M., Russo, J. J., Ju, J., Sheridan, R., Sander, C., Zavolan, M., and Tuschl, T. (2006) Nature 442 203-207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aravin, A., Sachidanandam, R., Girard, A., Fejes-Toth, K., and Hannon, G. J. (2007) Science 316 744-747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Girard, A., Sachidanandam, R., Hannon, G. J., and Carmell, M. A. (2006) Nature 442 199-202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lau, N. C., Seto, A. G., Kim, J., Kuramochi-Miyagawa, S., Nakano, T., Bartel, D. P., and Kingston, R. E. (2006) Science 313 363-367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watanabe, T., Takeda, A., Tsukiyama, T., Mise, K., Okuno, T., Sasaki, H., Minami, N., and Imai, H. (2006) Genes Dev. 20 1732-1743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carmell, M. A., Girard, A., van de Kant, H. J., Bourc'his, D., Bestor, T. H., de Rooij, D. G., and Hannon, G. J. (2007) Dev. Cell 12 503-514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brower-Toland, B., Findley, S., Jiang, L., Liu, L., Dus, M., Zhou, P., Elgin, S., and Lin, H. (2007) Genes Dev. 21 2300-2311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yin, H., and Lin, H. (2007) Nature 450 304-308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson, J. E., Connell, J. E., and Macdonald, P. M. (1996) Development 122 1631-1639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harris, A. N., and Macdonald, P. M. (2001) Development 128 2823-2832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Megosh, H. B., Cox, D. N., Campbell, C., and Lin, H. (2006) Curr. Biol. 16 1884-1894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grivna, S. T., Pyhtila, B., and Lin, H. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 13415-13420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuramochi-Miyagawa, S., Kimura, T., Ijiri, T. W., Isobe, T., Asada, N., Fujita, Y., Ikawa, M., Iwai, N., Okabe, M., Deng, W., Lin, H., Matsuda, Y., and Nakano, T. (2004) Development 131 839-849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuramochi-Miyagawa, S., Watanabe, T., Gotoh, K., Totoki, Y., Toyoda, A., Ikawa, M., Asada, N., Kojima, K., Yamaguchi, Y., Ijiri, T. W., Hata, K., Li, E., Matsuda, Y., Kimura, T., Okabe, M., Sakaki, Y., Sasaki, H., and Nakano, T. (2008) Genes Dev. 22 908-917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deng, W., and Lin, H. (2002) Dev. Cell 2 819-830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bloch, D. B., Gulick, T., Bloch, K. D., and Yang, W. H. (2006) RNA 12 707-709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cataldo, L., Mastrangelo, M. A., and Kleene, K. C. (1997) Exp. Cell Res. 231 206-213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Godchaux, W., III, Adamson, S. D., and Herbert, E. (1967) J. Mol. Biol. 27 57-72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kleene, K. C. (1993) Dev. Biol. 159 720-731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin, H., and Spradling, A. C. (1997) Development 124 2463-2476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bellve, A. R., Millette, C. F., Bhatnagar, Y. M., and O'Brien, D. A. (1977) J. Histochem. Cytochem. 25 480-494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koshimizu, U., Nishioka, H., Watanabe, D., Dohmae, K., and Nishimune, Y. (1995) Mol. Reprod. Dev. 40 221-227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ross, A. J., and Capel, B. (2005) Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 16 19-25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kotaja, N., Bhattacharyya, S. N., Jaskiewicz, L., Kimmins, S., Parvinen, M., Filipowicz, W., and Sassone-Corsi, P. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 2647-2652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nelson, P. T., Hatzigeorgiou, A. G., and Mourelatos, Z. (2004) RNA 10 387-394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shi, H., Ullu, E., and Tschudi, C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 49889-49893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Johnson, K. R., Merrick, W. C., Zoll, W. L., and Zhu, Y. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 7106-7113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Houwing, S., Kamminga, L. M., Berezikov, E., Cronembold, D., Girard, A., van den Elst, H., Filippov, D. V, Blaser, H., Raz, E., Moens, C. B., Plasterk, R. H., Hannon, G. J., Draper, B. W., and Ketting, R. F. (2007) Cell 129 69-82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morita, S., Horii, T., Kimura, M., Goto, Y., Ochiya, T., and Hatada, I. (2007) Genomics 6 687-696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morel, J. B., Godon, C., Mourrain, P., Beclin, C., Boutet, S., Feuerbach, F., Proux, F., and Vaucheret, H. (2002) Plant Cell 14 629-639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pal-Bhadra, M., Bhadra, U., and Birchler, J. A. (2002) Mol. Cell 9 315-327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pal-Bhadra, M., Leibovitch, B. A., Gandhi, S. G., Rao, M., Bhadra, U., Birchler, J. A., and Elgin, S. C. (2004) Science 303 669-672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sarot, E., Payen-Groschene, G., Bucheton, A., and Pelisson, A. (2004) Genetics 166 1313-1321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu, J., Rivas, F. V., Wohlschlegel, J., Yates, J. R., III, Parker, R., and Hannon, G. J. (2005) Nat. Cell Biol. 7 1261-1266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Humphreys, D. T., Westman, B. J., Martin, D. I., and Preiss, T. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102 16961-16966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pillai, R. S., Bhattacharyya, S. N., Artus, C. G., Zoller, T., Cougot, N., Basyuk, E., Bertrand, E., and Filipowicz, W. (2005) Science 309 1573-1576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kapp, L. D., and Lorsch, J. R. (2004) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73 657-704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Groisman, I., Jung, M. Y., Sarkissian, M., Cao, Q., and Richter, J. D. (2002) Cell 109 473-483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gonczy, P., Echeverri, C., Oegema, K., Coulson, A., Jones, S. J., Copley, R. R., Duperon, J., Oegema, J., Brehm, M., Cassin, E., Hannak, E., Kirkham, M., Pichler, S., Flohrs, K., Goessen, A., Leidel, S., Alleaume, A. M., Martin, C., Ozlu, N., Bork, P., and Hyman, A. A. (2000) Nature 408 331-336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jakymiw, A., Lian, S., Eystathioy, T., Li, S., Satoh, M., Hamel, J. C., Fritzler, M. J., and Chan, E. K. (2005) Nat. Cell Biol. 7 1267-1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rehwinkel, J., Behm-Ansmant, I., Gatfield, D., and Izaurralde, E. (2005) RNA 11 1640-1647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Behm-Ansmant, I., Rehwinkel, J., Doerks, T., Stark, A., Bork, P., and Izaurralde, E. (2006) Genes Dev. 20 1885-1898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kotaja, N., Lin, H., Martti Parvinen, M., and Sassone-Corsi, P. (2006) J. Cell Sci. 119 2819-2825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.