Abstract

Theileria parasites cause severe bovine disease and death in a large part of the world. These apicomplexan parasites possess a relic plastid (apicoplast), whose metabolic pathways include several promising drug targets. Putative inhibitors of these targets were screened, and we identified antiproliferative compounds that merit further characterization.

East Coast fever is an infectious disease of cattle caused by the intracellular apicomplexan parasite Theileria parva. East Coast fever is frequently fatal and causes economic loss and restricts cattle husbandry in parts of sub-Saharan Africa. T. parva is transmitted by ticks of the genus Rhipicephalus, which inject cattle with infectious sporozoites. Sporozoites invade lymphocytes and develop into multinucleated macroschizonts that can progress down two pathways. One involves the transformation of B or T lymphocytes into proliferating cells, with the multinucleate macroschizont dividing between the daughter lymphocytes (18). The second generates free merozoites that subsequently infect erythrocytes, in which they form “piroplasms” that can infect blood-feeding ticks. The blood stage causes pathology in T. annulata infections, but most pathology caused by T. parva is due to the proliferation and widespread tissue infiltration of infected lymphocytes.

East Coast fever can be controlled by acaricide prevention of vector bites, by vaccination, and by chemotherapy. Vaccination is conducted using a long-standing technique of simultaneous injection of live, infective sporozoites and a curative dose of tetracycline, which gives long-term protection (17, 23, 25). In areas of greater disease transmission and in larger herds, vaccination is the most cost-effective strategy (8, 22). Buparvaquone is widely and successfully used to treat early-stage infections of T. parva, though its cost may be prohibitive for smaller farms and poorer farmers (8, 15, 21). Low-cost alternatives will be urgently required in the inevitable event of buparvaquone resistance.

A potential source of targets for new antitheilerials is the relic plastid (or apicoplast) found in most apicomplexan genera. The eubacterial ancestry of apicoplasts is reflected in much of their metabolism. These departures from animal metabolism represent opportunities for selective inhibition that have been exploited in other medically important apicomplexans, such as Plasmodium spp. (the causative agents of malaria) and Toxoplasma spp. (33). The recent completion of the genome sequencing projects for two Theileria species, T. parva (11) and T. annulata (causative agent of tropical theileriosis) (24), now makes it possible to bioinformatically survey this important genus for promising apicoplast drug targets. At least 18 distinct apicoplast molecular chemotherapeutic targets have been experimentally validated in other apicomplexans. Of these targets, nine have clear matches in the Theileria parva genome (11), while nine have no apparent orthologues in either Theileria genome (Table 1). The missing proteins include all enzymes for heme and fatty acid syntheses (11) as well as glyoxalase I and II and a peptide deformylase (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Drug targets in Plasmodium and Theileria

| Target name | P. falciparum gene | T. parva gene | Inhibition datab |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase | PF14_0641 | TP02_0073 | Inhibited by fosmidomycin which stops IPP synthesis and shows promise in clinical trials (14) |

| 3-Hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydratase (FabZ) | PF13_0128 | No match | Competitive inhibitors of FabZ inhibit fatty acid synthesis and parasite growth (27) |

| Acetyl-CoA carboxylase | PF14_0664 | No match | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase is the target of aryloxyphenoxypropionate herbicides used against grass species; these inhibitors inhibit growth of Plasmodium and Toxoplasma in culture (32, 35) |

| Beta-ketoacyl-ACP synthase I/II (FabB/FabF) | PFF1275c | No match | Thiolactomycin and cerulenin both inhibit FabB/FabF activity and kill parasites in culture (16) |

| Beta-ketoacyl-ACP synthase III (FabH) | PFB0505c | No match | Thiolactomycin and thiolactomycin analogues inhibit FabH and kill parasites in culture (32) |

| Delta-aminolevulinate dehydratase | PF14_0381 | No match | Succinylacetone, an ALAD inhibitor, kills parasites in culture, but at high, mammalian-toxic concentrations (29) |

| EF-TU (encoded by plastid genome) | CAA64593 | TP05_0019 | The antibiotics kirromycin and amythiamicin inhibit EF-TU, parasite growth, and cure malaria models in mice (6) |

| Enoyl-ACP-reductase (FabI) | PFF0730c | No match | Triclosan inhibits FabI and fatty acid synthesis, and kills parasites both in culture and in animal models (30) |

| Fe-superoxide dismutasea | PFF1130c | TP04_0025 | Piperazine, chalcone derivatives and members of chemical libraries have sp act against parasite Fe-superoxide dismutase and kill parasites in culture (28) |

| Formylmethionine deformylase | PFI0380c | No match | Actinonin, a formylmethionine deformylase inhibitor, inhibits parasite growth in culture (34) |

| Glyoxalase I (plastid targeted) | PFF0230c | No match | The glyoxylase I inhibitor S-p-bromobenzylglutathione kills cultured parasites (31) |

| Glyoxalase II (plastid targeted) | PFL0285w | No match | S-d-Lactoylglutathione analogues inhibit both Plasmodium glyoxalase I and glyoxalase II (1) |

| Large-subunit rRNA (encoded by plastid genome) | X61660 | TP05_0046 | Antibiotics, including clindamycin and thiostrepton, bind to the large-subunit rRNA, inhibiting apicoplast translation and killing parasites in culture; clindamycin cures infected animals and humans (10) |

| M1 family aminopeptidase | MAL13P1.56 | TP01_0397 | Protease inhibitors like bestatin and amastatin inhibit this and other peptidases, and kill parasites in culture (2) |

| RNA polymerase B (encoded by plastid genome) | CAA64572 | TP05_0028 | Rifampin is an RpoB inhibitor that kills parasites in culture and cures human infections; however, clearance is sometimes slow (12) |

| Small-subunit rRNA (encoded by plastid genome) | X57167 | TP05_0045 | Doxycycline and tetracycline inhibit apicoplast protein synthesis, and doxycycline is a widely used human antimalarial (26) |

| Topoisomerase I | PFE0520c | TP02_0198 | Camptothecin is a topisomerase I inhibitor that kills parasites (3) |

| Topoisomerase II | PFL1915w | TP01_1125 | Antisense RNA against topoisomerase II is lethal in culture, and common fluoroquinolone antibiotics like ciprofloxacin efficiently inhibit topoisomerase II, but these drugs may have a delayed effect (9) |

An isoform of Fe-superoxide dismutase may be dually targeted to the mitochondrion and apicoplast.

IPP, isopentenyl diphosphate; ALAD, aminolevulinate; EF-TU, elongation factor thermo unstable.

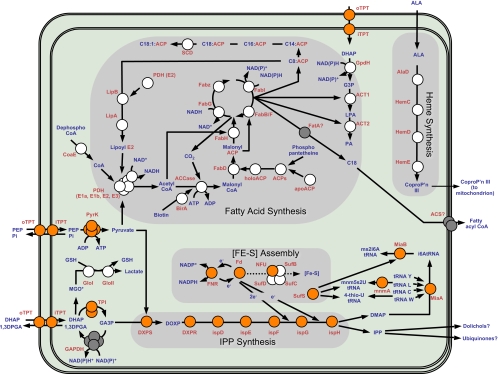

FIG. 1.

Metabolic map of the Theileria apicoplast. Apicoplast fatty acid and isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) biosyntheses are shown. This figure represents an in silico reconstruction of apicoplast metabolism in Theileria compared to a similar reconstruction of Plasmodium apicoplast metabolism. Enzymes are represented by circles. Orange circles represent enzymes that are predicted to be apicoplast targeted in both Plasmodium and Theileria. White circles represent enzymes that are predicted to be apicoplast targeted in Plasmodium but which are absent in Theileria. The figure highlights the absence of the pathways for fatty acid synthesis and heme synthesis in Theileria, as well as the absence of at least two [Fe-S] cluster assembly enzymes. Glyoxylase detoxification of the DHAP (dihydroxyacetone phosphate) breakdown product methylglyoxal is also present in the Plasmodium apicoplast but absent in Theileria. Gray circles represent enzymes that may participate in apicoplast metabolism and for which no gene has yet been found in Plasmodium or Theileria. An apicoplast-targeted GAPDH gene is predicted from the Toxoplasma genome, but orthologues of this gene cannot be found in Plasmodium or Theileria. Enzyme names are shown in red, and substrates and products are shown in blue. ACCase, acetyl-CoA carboxylase; ACS, acyl-CoA synthetase; ACT1, glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase; ACT2, 1-acyl-glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase; BirA, biotin-(acetyl-CoA carboxylase) ligase; DXPR, 1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate (DXP) reductoisomerase (IspC); DXPS, DXP synthase; FabB/F, β-ketoacyl ACP synthase I/II; FabD, malonyl-CoA transacylase; FabG, β-ketoacyl ACP reductase; FabH, β-keto-ACP synthase III; FabI, enoyl ACP reductase; FabZ, β-hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydratase; FatA, acyl-ACP thioesterase; ferredoxin (Fd), an electron carrier protein; FNR, ferredoxin-NADP+-reductase; GloI, glyoxalase I; GloII, glyoxalase II; GSH, glutathione; IspD, 4-diphosphocytidyl-2C-methyl-d-erythritol synthetase; IspE, 4-diphosphocytidyl-2C-methyl-derythritol kinase; IspF, 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase; IspG, (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate synthase; IspH, 1-hydroxy-2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl 4-diphosphate reductase; LipA, lipoic acid synthase; LipB, lipoate protein ligase; LPA, lysophosphatidic acid; MGO*, methylglyoxal; MiaA, delta-(2)-isopentenylpyrophosphate tRNA-adenosine transferase; MiaB, tRNA methylthiotransferase; MnmA, 2-thiouridine modification of tRNA; NAD+/NADH, nicotinamide adenosine; PA, phosphatidic acid; PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase; PDH(E2), pyruvate dehydrogenase complex E2 subunit; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; Pi, inorganic phosphate; PP, pyrophosphate; iTPT, inner membrane phosphate translocator; oTPT, outer membrane phosphate translocator; PYK, pyruvate kinase; SCD, stearoyl-ACP desaturase; SufBCD, SufB-SufC-SufD cysteine desulfurase complex; ALA, 5-aminolevulinic acid; CoproP'n III, coproporphyrinogen III; DMAP, dimethylallyl pyrophosphate; 1,3DPGA, 1,3-diphosphoglycerate; G3P, sn-glycerol 3-phosphate; i6AtRNA, N6-isopentenyladenosine tRNA; mnm5s2U, 5-methylaminomethyl-2-thiouridine; ms2i6A, 2-methylthio-N6-isopentenyladenosine; GA3P, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

To examine whether in silico Theileria matches to Plasmodium and Toxoplasma drug targets represent potential chemotherapeutic targets, we tested a small number of compounds that target various apicoplast functions for their ability to inhibit Theileria-induced proliferation of parasitized B cells. The functions of these targets were DNA replication (ciprofloxacin), transcription (rifampin [rifampicin]), translation (clindamyacin), and isopentenyl diphosphate synthesis (fosmidomycin). We also tested two fatty acid synthesis inhibitors: triclosan, which is thought to inhibit enoyl acyl carrier protein (ACP) reductase (30), and fenoxaprop, which is thought to inhibit acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) carboxylase (32). No enoyl ACP reductase or acetyl-CoA carboxylase is apparent in the Theileria genomes.

Drug assays were conducted on T. parva-infected B cells grown as previously described (19). Parasite cultures were initiated in 96-well flat-bottom plates with starting densities of 2.5 × 105 cells/ml and were diluted in series of drug concentrations from 1.56 μM to 400 μM in a total volume of 200 μl. Negative controls were set up adjacent to each replicate series, without any drug. Cells were grown for 32 h after the addition of the drug, and then 2 μCi of tritiated thymidine was added to each well. The culture was allowed to proceed for an additional 16 h (48 h in total) before being harvested onto filter paper, and thymidine incorporation was counted with an automated beta counter (Skatron). Within each experiment, the concentrations were determined in triplicate, and each experiment was repeated at least once with separate batches of parasites in independent biological experiments. Buparvaquone was used as a positive control for parasite inhibition (13).

Of the compounds tested that target housekeeping functions, the inhibitors of DNA replication and transcription had modest inhibitory effect, with 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50) in the mid-micromolar range (Table 2), while the inhibitor of prokaryotic-type translation (clindamycin) had a very high IC50. These inhibitory effects are less potent than they are against in vitro Plasmodium falciparum growth. Fosmidomycin, a potent inhibitor of the Plasmodium DOXP (1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate) isopentenyl diphosphate synthesis enzyme DOXP reductoisomerase, unexpectedly had no effect on thymidine incorporation in our assay, even at the highest (400 μM) concentrations used. This pathway is currently the subject of considerable inhibitor discovery in plants and in Plasmodium. It remains to be tested whether other inhibitors of the DOXP pathway, such as ketoclomazone (20), have antitheilerial activity. Unexpectedly, triclosan and fenoxaprop each inhibited thymidine incorporation at micromolar concentrations equivalent to their IC50 levels in Plasmodium and Toxoplasma (Table 2), despite the absence of any fatty acid synthesis enzymes, their presumed targets, in Theileria.

TABLE 2.

IC50 values for inhibitors of putative apicoplast enzymesa

| Inhibitor | Mean IC50 ± SD (μM) | Presumed target |

|---|---|---|

| Ciprofloxacin | 123 ± 38 | Topoisomerase II |

| Clindamycin | >400 | Large-subunit rRNA |

| Rifampin | 96 ± 2 | RNA polymerase B |

| Triclosan | 20 ± 2 | Missing |

| Fenoxaprop | 262 ± 13 | Missing |

| Fosmidomycin | No inhibition | DOXP reductoisomerase |

Inhibition of tritiated thymidine uptake by T. parva-infected B-lymphocyte culture. Cells were treated with drugs over 48 h and allowed to incorporate tritiated thymidine over the final 12 h of this treatment. IC50s are the averages for three replicate samples from a representative experiment.

Parasite and host cell proliferation are mutually dependent, so compounds that inhibit Theileria-infected lymphocytes may be acting on host and/or parasite processes. Because normal B cells do not naturally proliferate in the absence of infection, no perfect control is available to test for the specificity of this inhibition on host or parasite proliferation. One previously employed surrogate is to measure inhibition of proliferation of (uninfected) lymphosarcoma-derived B cells. All compounds were assayed for inhibition of the BL3 lymphosarcoma line by using the thymidine incorporation assay, conducted identically to that described above. At concentrations that produced 50% growth inhibition of Theileria-infected B cells, the assay revealed >75% inhibition of BL3 proliferation with triclosan, fenoxaprop, and rifampin and 28% inhibition with clindamycin (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Ciprofloxacin did not inhibit proliferation. An independent assay was conducted to detect induction of apoptosis of BL3 cells in the presence of the same compounds. Drug-treated BL3 cells were stained with annexin V and propidium iodide 24 h after the addition of inhibitor, and apoptosis was measured by fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis as described previously (7). This assay detected considerable induction of BL3 apoptosis after treatment with triclosan and fenoxaprop (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) but minimal apoptosis or no apoptosis with the other compounds. Several of these inhibitors are widely used and well tolerated in human health applications, so their inhibition of lymphosarcoma proliferation is clearly not an indicator of general mammalian toxicity. However, the antiproliferative effects of some of these compounds for BL3 cells suggest that their inhibition of proliferation for Theileria-infected B cells may well be due to inhibition of B-cell processes as well as or instead of parasite-specific inhibition. Both controls are to some extent limited by the difference in dynamics of replication between BL3 cells and parasite-infected B cells, which probably explains the effects of several of these compounds being greater on the BL3 line than on the Theileria-infected lymphocytes.

Our inhibition assays indicate that several putative inhibitors of apicoplast function inhibit Theileria-induced proliferation of lymphocytes, but their modes of action are unclear. Ciprofloxacin appears to specifically inhibit growth of Theileria-infected B cells without having any effect on uninfected B cells. Three other compounds, fenoxaprop, triclosan (inhibitors of fatty acid synthesis), and rifampin (bacterial transcription inhibitor), inhibited proliferation of Theileria-infected lymphocytes, but this effect could not be separated or distinguished from their direct inhibition of B-cell proliferation. The IC50s observed for these compounds were similar to those observed in other apicomplexans, but the micromolar-range IC50s of these inhibitors do not make them immediately appealing as antitheilerials. The proposed targets of fenoxaprop and triclosan in Plasmodium, the single-polypeptide-type acetyl-CoA carboxylase (32) and enoyl ACP reductase (30), respectively, are absent in both Theileria and humans, so their mode of action here cannot be via these enzymes. Babesia, another apicomplexan parasite, also lacks enoyl ACP reductase (5) but is similarly susceptible to triclosan (4). These data cast uncertainty on the specificity of these proposed compound-target relationships in other apicomplexans.

In other apicomplexans, some drugs inhibiting apicoplast processes inhibit growth of the parasite only after it has egressed from the initial schizont and reinvaded a new host cell. The mechanism behind this “delayed death” phenomenon is not understood. It is important to note that the life stage analyzed in this study involves the replication of Theileria parasites without formation of daughter merozoites or reinvasion and exploitation of a new host cell. The investigation of potential apicoplast inhibitors on additional life stages of Theileria, including merogeny, will be of interest but is unlikely to be directly applicable to the development of antidisease chemotherapeutics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Siggi Sato (National Institute for Medical Research, United Kingdom) for critical reading and advice.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 December 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aac.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akoachere, M., R. Iozef, S. Rahlfs, M. Deponte, B. Mannervik, D. J. Creighton, H. Schirmer, and K. Becker. 2005. Characterization of the glyoxalases of the malarial parasite Plasmodium falciparum and comparison with their human counterparts. Biol. Chem. 386:41-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allary, M., J. Schrevel, and I. Florent. 2002. Properties, stage-dependent expression and localization of Plasmodium falciparum M1 family zinc-aminopeptidase. Parasitology 125:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodley, A. L., J. N. Cumming, and T. A. Shapiro. 1998. Effects of camptothecin, a topoisomerase I inhibitor, on Plasmodium falciparum. Biochem. Pharmacol. 55:709-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bork, S., N. Yokoyama, T. Matsuo, F. G. Claveria, K. Fujisaki, and I. Igarashi. 2003. Growth inhibitory effect of triclosan on equine and bovine Babesia parasites. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 68:334-340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brayton, K. A., A. O. Lau, D. R. Herndon, L. Hannick, L. S. Kappmeyer, S. J. Berens, S. L. Bidwell, W. C. Brown, J. Crabtree, D. Fadrosh, T. Feldblum, H. A. Forberger, B. J. Haas, J. M. Howell, H. Khouri, H. Koo, D. J. Mann, J. Norimine, I. T. Paulsen, D. Radune, Q. Ren, R. K. Smith, Jr., C. E. Suarez, O. White, J. R. Wortman, D. P. Knowles, Jr., T. F. McElwain, and V. M. Nene. 2007. Genome sequence of Babesia bovis and comparative analysis of apicomplexan hemoprotozoa. PLoS Pathog. 3:1401-1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clough, B., M. Strath, P. Preiser, P. Denny, and R. Wilson. 1997. Thiostrepton binds to malarial plastid rRNA. FEBS Lett. 406:123-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dessauge, F., S. Hilaly, M. Baumgartner, B. Blumen, D. Werling, and G. Langsley. 2005. c-Myc activation by Theileria parasites promotes survival of infected B-lymphocytes. Oncogene 24:1075-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D'Haese, L., K. Penne, and R. Elyn. 1999. Economics of theileriosis control in Zambia. Trop. Med. Int. Health 4:A49-A57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Divo, A., A. Sartorelli, C. Patton, and F. Bia. 1988. Activity of fluoroqinolone antibiotics against Plasmodium falciparum in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 32:1182-1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fichera, M. E., and D. S. Roos. 1997. A plastid organelle as a drug target in apicomplexan parasites. Nature 390:407-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gardner, M. J., R. Bishop, T. Shah, E. P. de Villiers, J. M. Carlton, N. Hall, Q. Ren, I. T. Paulsen, A. Pain, M. Berriman, R. J. Wilson, S. Sato, S. A. Ralph, D. J. Mann, Z. Xiong, S. J. Shallom, J. Weidman, L. Jiang, J. Lynn, B. Weaver, A. Shoaibi, A. R. Domingo, D. Wasawo, J. Crabtree, J. R. Wortman, B. Haas, S. V. Angiuoli, T. H. Creasy, C. Lu, B. Suh, J. C. Silva, T. R. Utterback, T. V. Feldblyum, M. Pertea, J. Allen, W. C. Nierman, E. L. Taracha, S. L. Salzberg, O. R. White, H. A. Fitzhugh, S. Morzaria, J. C. Venter, C. M. Fraser, and V. Nene. 2005. Genome sequence of Theileria parva, a bovine pathogen that transforms lymphocytes. Science 309:134-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gardner, M. J., D. H. Williamson, and R. J. M. Wilson. 1991. A circular DNA in malaria parasites encodes an RNA polymerase like that of prokaryotes and chloroplasts. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 44:115-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hudson, A. T., A. W. Randall, M. Fry, C. D. Ginger, B. Hill, V. S. Latter, N. McHardy, and R. B. Williams. 1985. Novel anti-malarial hydroxynaphthoquinones with potent broad spectrum anti-protozoal activity. Parasitology 90(Part 1):45-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jomaa, H., J. Wiesner, S. Sanderbrand, B. Altincicek, C. Weidemeyer, M. Hintz, I. Turbachova, M. Eberl, J. Zeidler, H. K. Lichtenthaler, D. Soldati, and E. Beck. 1999. Inhibitors of the nonmevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis as antimalarial drugs. Science 285:1573-1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kivaria, F. M. 2006. Estimated direct economic costs associated with tick-borne diseases on cattle in Tanzania. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 38:291-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lack, G., E. Homberger-Zizzari, G. Folkers, L. Scapozza, and R. Perozzo. 2006. Recombinant expression and biochemical characterization of the unique elongating beta-ketoacyl-ACP synthase involved in fatty acid biosynthesis of Plasmodium falciparum using natural and artificial substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 281:9538-9546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKeever, D. J. 2007. Live immunisation against Theileria parva: containing or spreading the disease? Trends Parasitol. 23:565-568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehlhorn, H., and E. Shein. 1984. The piroplasms: life cycle and sexual stages. Adv. Parasitol. 23:37-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreau, M. F., J. L. Thibaud, L. B. Miled, M. Chaussepied, M. Baumgartner, W. C. Davis, P. Minoprio, and G. Langsley. 1999. Theileria annulata in CD5+ macrophages and B1 B cells. Infect. Immun. 67:6678-6682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mueller, C., J. Schwender, J. Zeidler, and H. K. Lichtenthaler. 2000. Properties and inhibition of the first two enzymes of the non-mevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 28:792-793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muraguri, G. R., H. K. Kiara, and N. McHardy. 1999. Treatment of East Coast fever: a comparison of parvaquone and buparvaquone. Vet. Parasitol. 87:25-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muraguri, G. R., S. K. Mbogo, N. McHardy, and D. P. Kariuki. 1998. Cost analysis of immunisation against east coast fever on smallholder dairy farms in Kenya. Prev. Vet. Med. 34:307-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oura, C. A., R. Bishop, B. B. Asiimwe, P. Spooner, G. W. Lubega, and A. Tait. 2007. Theileria parva live vaccination: parasite transmission, persistence and heterologous challenge in the field. Parasitology 134:1205-1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pain, A., H. Renauld, M. Berriman, L. Murphy, C. A. Yeats, W. Weir, A. Kerhornou, M. Aslett, R. Bishop, C. Bouchier, M. Cochet, R. M. Coulson, A. Cronin, E. P. de Villiers, A. Fraser, N. Fosker, M. Gardner, A. Goble, S. Griffiths-Jones, D. E. Harris, F. Katzer, N. Larke, A. Lord, P. Maser, S. McKellar, P. Mooney, F. Morton, V. Nene, S. O'Neil, C. Price, M. A. Quail, E. Rabbinowitsch, N. D. Rawlings, S. Rutter, D. Saunders, K. Seeger, T. Shah, R. Squares, S. Squares, A. Tivey, A. R. Walker, J. Woodward, D. A. Dobbelaere, G. Langsley, M. A. Rajandream, D. McKeever, B. Shiels, A. Tait, B. Barrell, and N. Hall. 2005. Genome of the host-cell transforming parasite Theileria annulata compared with T. parva. Science 309:131-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radley, D. E. 1981. Infection and treatment method of immunization against theileriosis, p. 227-237. In A. D. Irvin, M. P. Cunningham, and A. S. Young (ed.), Advances in the control of theileriosis: proceedings of an international conference held at the international laboratory for research on animal diseases in Nairobi, 9-13th February, 1981. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, The Hague, The Netherlands.

- 26.Sato, S., and R. J. Wilson. 2005. The plastid of Plasmodium spp.: a target for inhibitors. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 295:251-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharples, F. P., P. M. Wrench, K. L. Ou, and R. G. Hiller. 1996. Two distinct forms of the peridinin-chlorophyll a-protein from Amphidinium carterae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1276:117-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soulère, L., P. Delplace, E. Davioud-Charvet, S. Py, C. Sergheraert, J. Perie, I. Ricard, P. Hoffmann, and D. Dive. 2003. Screening of Plasmodium falciparum iron superoxide dismutase inhibitors and accuracy of the SOD-assays. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 11:4941-4944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Surolia, N., and G. Pasmanaban. 1992. De novo biosynthesis of heme offers a new chemotherapeutic target in the human malarial parasite. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 187:744-750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Surolia, N., and A. Surolia. 2001. Triclosan offers protection against blood stages of malaria by inhibiting enoyl-ACP reductase of Plasmodium falciparum. Nat. Med. 7:167-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thornalley, P. J., M. Strath, and R. J. Wilson. 1994. Antimalarial activity in vitro of the glyoxalase I inhibitor diester, S-p-bromobenzylglutathione diethyl ester. Biochem. Pharmacol. 47:418-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waller, R. F., S. A. Ralph, M. B. Reed, V. Su, J. D. Douglas, D. E. Minnikin, A. F. Cowman, G. S. Besra, and G. I. McFadden. 2003. A type II pathway for fatty acid biosynthesis presents drug targets in Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:297-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiesner, J., A. Reichenberg, S. Heinrich, M. Schlitzer, and H. Jomaa. 2008. The plastid-like organelle of apicomplexan parasites as drug target. Curr. Pharm. Des. 14:855-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wiesner, J., S. Sanderbrand, B. Altincicek, E. Beck, and H. Jomaa. 2001. Seeking new targets for antiparasitic agents. Trends Parasitol. 17:7-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zuther, E., J. J. Johnson, R. Haselkorn, R. McLeod, and P. Gornicki. 1999. Growth of Toxoplasma gondii is inhibited by aryloxyphenoxypropionate herbicides targeting acetyl-CoA carboxylase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:13387-13392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.