Abstract

Insulin-induced gene 2 (Insig2) was recently identified as a putative positive prognostic biomarker for colon cancer prognosis. Insig2 has been previously reported to be an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane protein, and a negative regulator of cholesterol synthesis. Here we report that Insig2 was validated as a gene with univariate negative prognostic capacity to discriminate human colon cancer survivorship. To investigate the functional roles it plays in tumor development and malignancy, Insig2 was over-expressed in colon cancer cells resulting in increased cellular proliferation, invasion, anchorage independent growth and inhibition of apoptosis. Over-expression of Insig2 appeared to suppress chemotherapeutic drug treatment-induced Bcl2 associated X protein (Bax) expression and activation. Insig2 was also found to localize to the mitochondria/heavy membrane fraction and associate with conformationally changed Bax. Moreover, Insig2 altered the expression of several additional apoptosis genes located in mitochondria, further supporting its new functional role in regulating mitochondrial mediated apoptosis. Our findings show that Insig2 is a novel colon cancer biomarker, and suggest, for the first time, a reasonable connection between Insig2 and Bax-mediated apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway.

Keywords: Insig2, biomarker, apoptosis, Bax, mitochondria

Insig2 was previously reported to be an ER protein that binds sterol regulatory element binding protein cleavage-activating protein (SCAP) and blocks export of sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs).1 Similar to Insulin induced gene 1 (Insig1),2 Insig2 also prevents the proteolytic processing of SREBPs by Golgi enzymes, thereby blocking cholesterol synthesis. Insig1 and 2 bind to 2 membrane-embedded proteins of ER, SCAP and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG CoA) reductase, that leads to the ubiquitination and degradation of the biosynthetic enzyme, and exerts actions that limit cholesterol synthesis by controlling SCAP and HMGCoA. Insigs stand at the crossroads between the transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulatory mechanisms that assure cholesterol homeostasis.3–6 Experiments in gene-targeted mice indicate that Insigs limit cholesterol synthesis, even under basal conditions. In livers of mice lacking both Insigs, the hepatic content of cholesterol was elevated by 7-fold, even when the animals were consuming a low-cholesterol chow diet.7 The Insig-double-knockout (DKO) mice manifested a highly selective defect, with 96% of Insig-DKO embryos having defects in midline facial development, ranging from cleft palate (52%) to complete cleft face (44%) in closure of facial structures,8 suggesting a critical role for Insigs in morphogenesis.

Previously, we produced a 43-gene colorectal cancer molecular staging classifier for accurately predicting 36-month prognosis.9 The classifier was derived from a 32,000-element cDNA microar-ray used to evaluate 78 human colon cancer specimens. The accuracy of this classifier was 90% in predicting prognosis and was significantly more effective than Dukes’ clinicopathological staging. Insig2 was identified as one of the key signature genes whose up-regulation was linked to poor prognosis.

Because of the apparent prognostic potential of Insig2, we first attempted to validate its biomarker potential. We elected to explore the biological functions of Insig2 in cellular proliferation, invasion, anchorage independent growth, and apoptosis to determine whether Insig2 plays a critical role in cancer development and progression.

Material and methods

Cells, reagents, transfection and treatments

The colon cancer cell lines HCT116, HT29 and SW620 were purchased from NCI. The cell lines KM12C, KM12SM and KM12L4A were a gift from Dr. I. Fidler (Department of Cancer Biology, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX). The SW480 cell line was purchased from ATCC. Plasmid pCMV-Insig2-Myc was purchased from ATCC, which was constructed by Dr. Joseph Goldstein’s laboratory (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, TX). Cells were incubated in DMEM medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Cellgro). Transient transfections were performed using LipofectAMIINE 2000 or Lipofectamine LTX reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the instructions of the manufacturer, and the stable clones were obtained by selection of colonies resistant to 600 μg/ml G418 sulfate (Cellgro). A variety of agents including etoposide (ETO, Sigma), 5-fluorouracil (5-FU, American Pharmaceutical Partners), camptothecin, staurosporine (STS) and Actinomycin D (Sigma) were used to induce apoptosis in HCT116 cells transfected with pcDNA3.1(+) (mock) or pCMV-Insig2-Myc. All treatments were done in triplicate.

Microarray

All colorectal tumor samples and normal mucosa samples were collected from patients at the Moffitt Cancer Center under IRB approved protocols. Total RNA was extracted and arrayed on the Affymetrix GeneChip U133Plus platform. The data was processed and normalized using the MAS5.0 procedure. Mean gene expression values for Insig2 were extracted and plotted by Dukes’ clinical staging together with standard error. Prognosis groups were defined by separating the 205 colorectal tumor patients by their Insig2 expression, either above or below the median Insig2 expression value. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were generated for the 2 prognosis groups and a log-rank test was used to determine if a difference existed in overall survival between the groups.

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis and quantitative real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as recommended by the manufacturer. First strand cDNA was performed using the Omniscript RT kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) as recommended by the manufacturer. In brief, 2 μg of RNA was incubated with 1 μg of Oligo-dT primers in the presence of 500 nM dNTP and 10 U of RNase inhibitor (Invitrogen).

Primers and probes for qRT-PCR were designed using Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems). The detection and quantitation of human Insig2 (GenBank accession no. AF527632) mRNA was accomplished using an amplicon-specific fluorescent oligonucleotide probe (Tm 68–70°C, with a 5′ reporter dye (FAM) and a downstream 3′ quencher dye (BHQ-1). The PCR reaction was performed in a 96-well optical reaction plate using Platinum Quantitative PCR-SuperMix-UDG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 2 μl of cDNA per well. Amplification profile is as follows: 50°C for 2 min (for UNG digest of contaminating PCR amplicons), 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min. Standards used for quantitation are derived from a serial dilution of the PCR products containing the gene specific primers for each gene of interest. Values were normalized using the GAPDH gene. qRT-PCR was performed with a Bio-Rad iCycler single-color real-time detection system.

DNA synthesis

DNA synthesis was assessed by [methyl 3H]thymidine incorporation assay.10 The cells of 2 stable HCT116-Insig2-Myc clones (clones 1 and 2) and mock control (pcDNA3.1(+) transfected) cells were cultured at 15,000 cells/well (96-well plate) for 48 hr. The [methyl-3H]thymidine (1.0 μCi/well) was added, incubated for 16 hr and the cells were harvested onto glass fiber filters using a microtiter plate cell harvester (Tomtec, CT). The incorporation of radiolabeled thymidine was determined by scintillation counting. The experiment was repeated twice; data from 4 separate wells for each data point were used to calculate the mean and standard deviations.

Cell invasion assay

HCT116 cells were used for checking cell invasion using the Biocoat Matrigel invasion chambers according to the manufacturer’s instruction (24-well plate, Becton Dickinson Labware).

Soft agar assay

A cell anchorage independent growth assay was done according to a previously published protocol.11 Three stable HCT116-Insig2-Myc clones (clones 1–3) and control cells (pcDNA3.1(+) transfected) were used.

Apoptosis assay

HCT116-Insig2-Myc clones (clones 1–3) and transfected control (pcDNA 3.1+) were treated with chemotherapeutic drugs or vehicle, stained with Annexin V-PE and 7-AAD (BD Biosciences) and analyzed by flow cytometry. The 2 quadrants of cells that stained positive for Annexin V-PE and negative for 7-AAD and that stained positive for both Annexin V-PE and 7-AAD were calculated as apoptotic. The apoptotic assay was confirmed with Active Caspase-3 PE MAb Apoptosis Kit (PharMingen, Cat. No. 550914), as per the manufacturer’s instructions, but equal numbers of cells from 3 stable HCT116-Insig2-Myc clones were pooled.

RNA interference

Duplexes of small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting human Insig2 and a nontargeting siRNA were synthesized by Dharmacon RNA Technologies (Catalog No. M-021039-00 and D-001210-01). Insig2-Myc clones or transfected control (pcDNA 3.1+) cells were transfected according to the protocol from Dharmacon. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were treated with ETO for 24 hr, and then both floating and attached cells were collected for FACS and Western blotting.

Western Blotting

Cellular lysates were prepared in Chaps buffer12 or in NP40 lysis buffer (50 mM Hepes (pH7.5), 100 mM sodium chloride, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40 (NP-40, Catalog number 492015, CALBIOCHEM) and 10% glycerol in the presence of protease inhibitors (1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 0.1 mM PMSF)). Extracted proteins (50 μg) were separated by 10 or 12% SDS-PAGE, transferred onto pure nitrocellulose membrane (BIO-RAD) and probed using after antibodies: anti-Myc, anti-Bax (N20) and anti-PERK (Santa Cruz), anti-cytochrome C (BD Biosciences), anti-Cox IV, anti-β-actin (Sigma).

Detection of Bax conformational change and subcellular fractionation

Detection of BAX conformational change and subcellular fractionation were performed as described.12 Activated Bax was detected by immunoprecipitation with anti-Bax 6A7 monoclonal antibody (BD Biosciences), which recognizes the conformation-ally changed Bax isolated in Chaps lysis buffer. Cell lysates (500 μg) were precleared by incubating with 25 μl rProtein G agarose beads (50% slurry, Invitrogen Life Technologies) at 4°C for 30–60 min. The lysate supernatant was incubated with 2 μg 6A7 antibody and 25 μl rProtein G agarose beads for 3 hr (an identical amount of lysate was used with same amount of nonimmune anti-mouse-IgG as negative control); The immunoprecipitation complexes with the rProtein G beads were washed thoroughly, eluted from the beads and used for Western blot with either anti-Bax polyclonal antibody N20 or anti-Myc antibody for Insig2-Myc. The mitochondria were recovered from the interface between 1.2 and 1.6 M of sucrose gradient layers and mixed with Chaps buffer to prepare a lysate—which was called the mitochondrial fraction but contained a mixture of both mitochondria as well as a small amount of ER membranes (i.e., heavy membrane). The supernatant derived from 10,000g was further centrifuged at 25,000g at 4°C for 30 min which produced a supernatant used as the cytosolic fraction.

Immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy

Cells were cultured and treated in 8 well chamber slides (Nalge Nunc International), washed in PBS and fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 5 min, blocked with 10% normal goat serum for 30 min. For activated Bax staining, the samples were incubated with polyclonal anti-Bax antibody (N20 clone, Santa Cruz; or NT clone, Upstate, both recognize activated Bax and produce similar results) for 1 hr, washed and stained with FITC-goat-anti-Rabbit IgG (Zymed, Invitrogen). For Bax and Insig2 double staining, the above anti-Bax antibody and anti-Myc antibody were used, and then detected by Alexa Fluor 488 (goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L)) and Alexa Fluor 555 (donkey anti-mouse IgG (H+L)) secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen). For mitochondria staining, cells were incubated with 50 nM MitoTracker Red CMXROS (Invitrogen, M7512) for 30 min at 37°C then fixed and permeablized as described above. For co-localization of Insig2 and Bax, cells were imaged with a Leica DMI6000 inverted microscope, TCS SP5 confocal scanner, and a 100×/1.40 NA Plan Apochromat oil immersion objective (Leica Microsystems, Germany). Argon and HeNe laser lines were applied to excite the samples and tunable filters were used to minimize crosstalk between fluorochromes. Colocalization mask was created with the LAS AF software (version 1.6.0 build 1016, Leica Microsystems, Germany). For colocalization imaging between Insig2 and mitochondria, samples were viewed with an inverted Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope with a 63×/1.20 NA water immersion objective. Argon and HeNe laser lines were applied to excite the samples using line switching to minimize crosstalk between fluorochromes.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the average with 95% confidence intervals. The differences between the treatment groups and untreated groups were determined using a two-sided student’s t test with two-sample unequal variance type.

Results

Insig2 serves as a novel biomarker for colon cancer

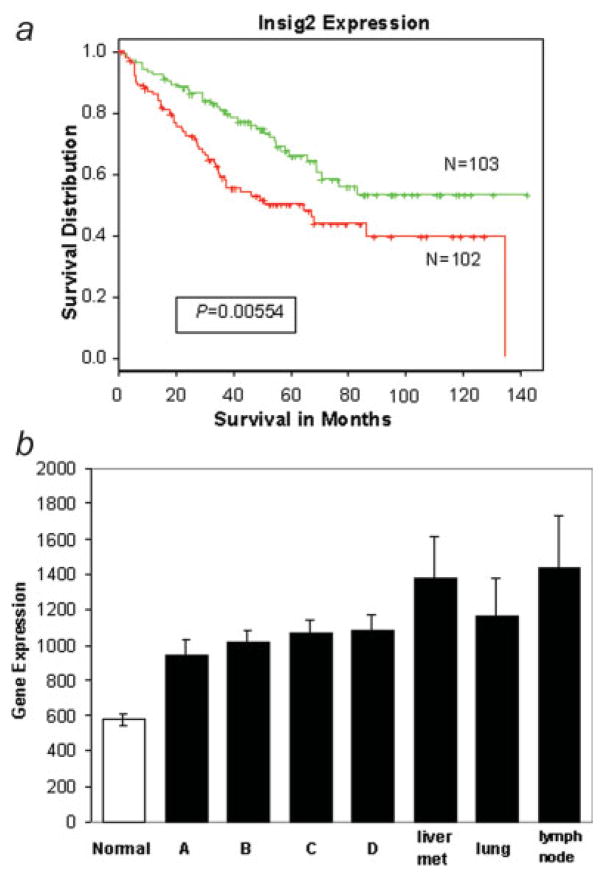

Our initial observations9 using 78 tumors and a complimentary DNA (cDNA) microarray platform were expanded to 205 new colon tumor samples to validate that Insig2 may be useful as a bio-marker for colon cancer prognosis. The Affeymetrix analysis confirmed that Insig2 had strong prognostic capacity to discriminate human colon cancer survivorship (Fig. 1a). Kaplan–Meier survival curves showed that patients with longer survival had lower levels of Insig2 mRNA expression and, conversely, higher expression of Insig2 correlated with worsened survival.

Figure 1.

Insig2 expression in human colon cancer patients. (a) Kaplan–Meier survival curves of colon cancer patients based on Insig2 expression. A total of 205 samples were arrayed on the Affy-metrix GeneChip U133Plus2 platform. Tumor samples were assigned to either good or poor prognosis groups based on over- (red line) or under-expression of Insig2 (green line), relative to the median Insig2 expression for all samples. The difference between these 2 curves was significant (p = 0.00554) using a log-rank test. (b) Insig2 mRNA expression levels in normal colon tissue and different Dukes’ stages of colon cancer primary tumors (Dukes’ stage A, B, C and D) and meta-static tumors (liver, lung and lymph nodes). The sample numbers from left to right are: 10, 33, 66, 64, 42, 18, 4 and 7, and their p-values versus normal are: 9.8E-9, 9.2E-20, 4.0E-19, 2.3E-13, 3.6E-6, 0.01and 0.001, respectively. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

Furthermore, Insig2 mRNA expression in different clinical stages of primary and metastatic human colon cancer was assessed. The data demonstrated that Insig2 mRNA levels were much higher in tumor samples than those in normal tissues, and the levels increased with increasing severity of tumor stage and metastatic potential (Fig. 1b). Not surprisingly, a similar Insig2 mRNA expression trend in human colon tissue (tumor vs. normal, early stage vs. late stage) was also confirmed by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using multiple pairs of samples (data not shown). The above data demonstrate that Insig2 may serve as a biomarker for colorectal cancer prognosis.

Insig2 affects DNA synthesis, invasion, anchorage independent growth and apoptosis of cells

Since Insig2 expression levels in colon tumors are higher than that in normal adjacent mucosal tissues, it is rational to hypothesize that it might play an important role in tumor development. To explore Insig2’s potential biological function, we decided to investigate the effect of Insig2 over-expression in colon cancer cells. The HCT116 human colon cancer cell line was initially chosen based on its very low level of endogenous Insig2 mRNA expression relative to 6 other colon cancer cell lines (HT29, KM12C, KM12SM, KM12L4A, SW480 and SW620) tested using real time RT-PCR (data not shown). HCT116 cells were transfected with a Myc-tagged Insig2 expression plasmid, pCMV-Insig2-Myc. Multiple stable clones expressing Insig2-Myc were selected with G418 and confirmed by western blot, real-time-PCR, and immunostaining. We chose 3 HCT116-Insig2-Myc clones to carry out our studies; with mRNA levels measured by RT-PCR (clones 1, 2 and 3 contained 276.4, 316.5 and 348.7 copies/cell, respectively).

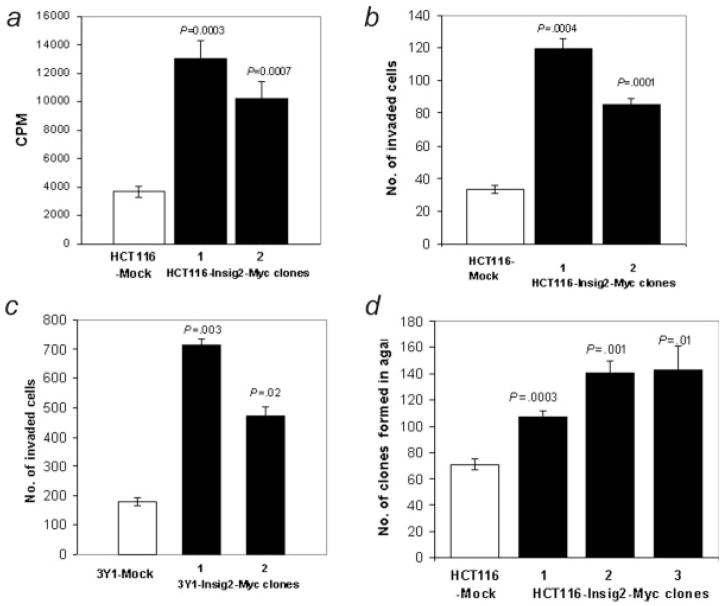

As Insig2 was linked to the reduced survival of colon cancer patients, we tested its potential functional effect on cellular proliferation, invasion, anchorage independent growth, and apoptosis. We first examined cellular proliferation with a [methyl-3H] thymidine incorporation assay.10 Stable clones expressing Insig2-Myc in HCT116 cells exhibited a 2- to 3-fold higher incorporation of thymidine than HCT116 “mock” cells transfected with an empty vector pcDNA3.1(+) (Fig. 2a), suggesting that the over-expression of Insig2 enhanced DNA synthesis. Using Matrigel chambers, we examined if Insig2 expression might promote cellular invasion. HCT116 clones expressing Insig2-Myc demonstrated enhanced invasion of the Matrigel barrier over those of mock transfected cells (Fig. 2b). Identical data were also obtained using the immortalized rat fibroblast cell line 3Y1 (Fig. 2c), suggesting the functional results were not limited to human or epithelial cell lineages. The ability of HCT116 cells transfected with Insig2-Myc to grow in soft agar was then tested as a measure of tumorigenicity. Using 3 independent clones of Insig2-Myc transfected HCT116 cells, twice as many colonies formed with cells expressing Insig2-Myc (Fig. 2d). Similar results were obtained with Insig2-Myc and mock transfected 3Y1 cells (data not shown) demonstrating enhanced anchorage independent growth in a non-epithelial non-human cell line.

Figure 2.

Insig2 promotes cell growth by enhancing DNA synthesis (a), invasion (b,c) and anchorage independent growth in soft agar (d). The cells used here were mock and Insig2-Myc stably transfected HCT116 cell clones (a,b,d) and the immortalized rat fibroblast cell line 3Y1 (c). The p-values are derived from comparison of the Insig2 clones versus their mock controls.

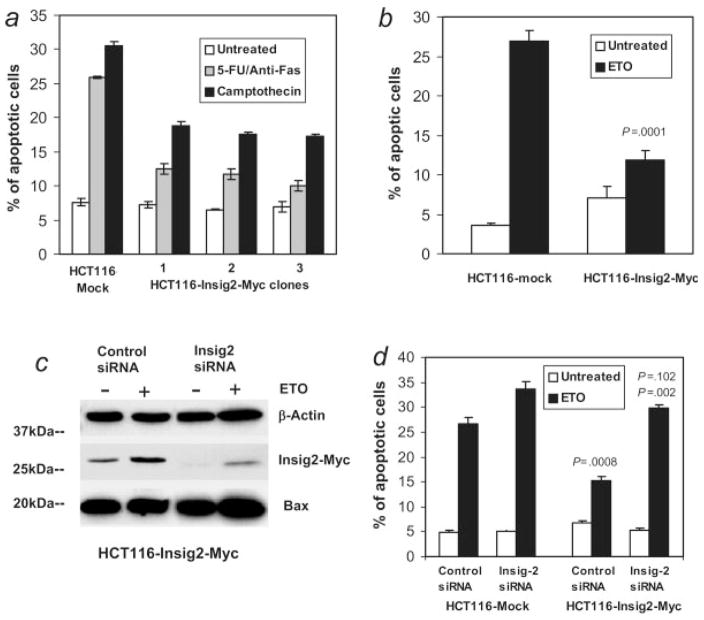

Next, the effect of Insig2 on cellular apoptosis was investigated using chemotherapeutic drugs 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), etoposide (ETO) or camptothecin as proapoptotic stimuli. Apoptotic cells were detected with Annexin V staining (Fig. 3a) or by measuring the activation of Caspase-3 (Fig. 3b) by flow cytometry. The Insig2-Myc transfected HCT116 cells produced significantly lower level of apoptosis induced by these 3 drugs than the mock transfected control cells. Taken together, these data suggested that Insig2 inhibited apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic drugs.

Figure 3.

Insig2 inhibits apoptosis. (a) Three HCT116-Insig2-Myc clones and mock transfected HCT116 cells were cultured overnight, treated with 5 μM 5-FU and 50 ng/ml anti-Fas, or 1 μM camptothecin for 24 hr. Both floating and attached cells were collected for staining with Annexin V-PE and 7-AAD and flow cytometry analysis. (b) HCT116-Insig2-Myc (the pool of the clones in (a) and mock transfected HCT116 cells) were treated with 100 μM ETO for 24 hr and then collected for staining with an antibody for active Caspase 3 and analyzed by flow cytometry. (c, d) Knockdown of Insig2 restored apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic drugs. The HCT116-Insig2-Myc clone and mock cells were transfected with Insig2 siRNA and control siRNA using oligofectamine. Forty-eight hours after transfection, 100 μM ETO was added to medium and cells were collected 24 hr later for Western blot (c) and, stained with Annexin V-PE and 7-AAD for cell apoptosis. (d) p = 0.0008, HCT116-Insig2-Myc cells compared to mock cells, both treated with non-target siRNA and ETO; p = 0.102, Insig2 siRNA transfected HCT116-Insig2-Myc cells versus Insig2 siRNA transfected mock cells, both treated with ETO; p = 0.002, Insig2 siRNA transfected versus non-target siRNA transfected HCT116-Insig2-Myc cells, both treated with ETO.

The earlier results show that Insig2 over-expression did enhance cellular proliferation, invasion, anchorage independent growth, as well as inhibit cellular apoptosis. The effects were significant compared to their mock controls, although there were some differences between different clones.

To further confirm the role of Insig2 on the inhibition of apoptosis, an Insig2-specific RNA interference (siRNA) assay was used to knock down the expression of Insig2. Figure 3c shows that Insig2-Myc protein levels were reduced substantially with siRNA treatment both in control as well as ETO-treated cells, where Insig2 levels actually increased with chemotherapeutic drug treatment. Levels of apoptosis of Insig2 siRNA transfected HCT116-Insig2-Myc cells were similar with that of transfected empty vector controls (p =0.102), and increased significantly over that of non-target siRNA transfected HCT116-Insig2-Myc cells (p =0.002) (Fig. 3d). Furthermore, the apoptotic rate was also increased in the Insig2 siRNA transfected HCT116-Mock control cells compared to nontarget siRNA treated mock cells. Collectively, these data demonstrate that Insig2 expression shows significant inhibition of chemotherapy-induced apoptosis.

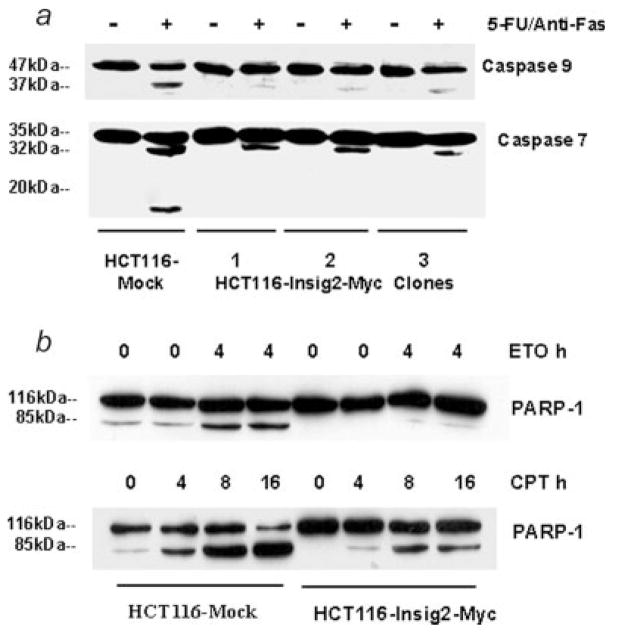

Insig2 inhibits cellular apoptosis by suppressing the expression and activation of Bax

To further investigate the mechanisms underlying Insig2 inhibition of chemotherapy-induced apoptosis, the capacity of Insig2 to inhibit the activation of apoptotic pathways was examined. The caspase family of cysteine proteases plays a key role in apoptosis. Upon induction of mitochondrial apoptosis, caspase 9 is cleaved from 47 into 37 kDa and procaspase 7 (35 kDa) is first converted to a 32 kDa intermediate, which is further processed into active subunits consisting of 20 and 11 kDa forms.13–15 We examined the activation of caspases 9/7 using HCT116 cells transfected with Insig2-Myc. Figure 4a clearly shows that the active form (37 kDa) of caspase 9 appeared in drug treated mock controls, but only a very weak band in 3 HCT116-Insig2-Myc clones. As for caspase 7, the 32 kDa intermediate band was weak in the 3 Insig2-Myc clones, and the activated 11 kDa form only appeared in drug treated mock cells. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) is a 116 kDa nuclear protein which is strongly activated by binding to DNA strand breaks. During apoptosis, caspases-3 and -7, cleave PARP to yield an 85 and a 25 kDa fragment. PARP cleavage is considered to be one of the classical characteristics of apoptosis.16 The cleavage of PARP-1 induced by both ETO and camptothecin (Fig. 4b) was inhibited in HCT116 cells transfected with Insig2-Myc. Taken together, these results suggested that Insig2 blocks this mitochondrial apoptotic pathway.

Figure 4.

Insig2 inhibits the activation/cleavage of caspases 9/7 and PARP-1. (a) The caspase 9/7 activation in HCT116 cells induced by 5-FU/anti-Fas treatment. The cells of HCT116 mock and HCT116-Insig2-Myc clones were grown overnight before adding 5-FU (5 μM) and anti-Fas. The drug treatment lasted for 24 hr. (b) Insig2 inhibits PARP-1 cleavage in HCT116 cells induced by ETO or camptothecin. The cells of HCT116 mock and mixed 3 HCT116-Insig2-Myc clones were grown overnight before adding ETO (25 μM) or camptothecin (CPT,1.0 μM). Full length PARP-1 (116 kDa) and cleaved PARP-1 (85 kDa) were detected with anti-PARP-1 antibody.

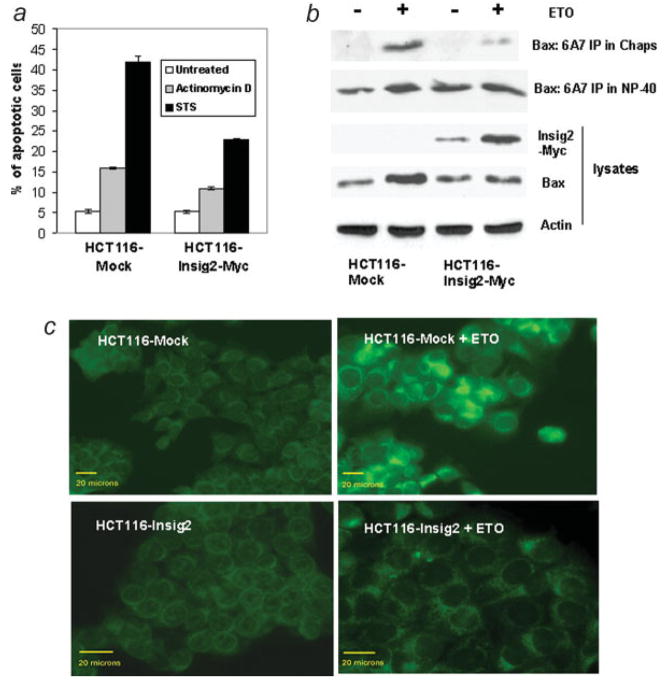

The proapoptotic protein Bax is known to play a pivotal role in mitochondria-mediated apoptosis.17–21 We reasoned that the over-expression of Insig2 might inhibit apoptosis through some heretofore unknown interaction with the proapoptotic Bax. In addition to etoposide, we also tested whether Insig2 over-expressing cells were also resistant to the Bax-dependent proapoptotic drugs staurosporine or actinomycin D.22 The data in Figure 5a demonstrate that the presence of Insig2-Myc can inhibit apoptosis induced by either staurosporin or actinomycin D. Next, we measured total Bax levels in Insig2-Myc and mock transfected HCT116 cells treated with ETO. ETO treatment increased Bax protein levels in mock transfected HCT116 cells but no apparent change in Bax levels was seen in HCT116 cells transfected with Insig2-Myc (Fig. 5b, total lysate blot). Real-time PCR confirmed similar changes in the Bax mRNA levels (data not showed). Thus, the over-expression of Insig2 in HCT116 cells suppressed both mRNA and protein levels of Bax expression induced by ETO. Because the treatments with ETO and other chemotherapeutic drugs did not induce apoptosis in Bax−/− HCT116,23,24 and the results presented above (Figs. 3c, 3d and 5b) show that the knockdown of Insig2 resulted in an increase in the levels of Bax and associated apoptosis, and ETO treatment did not induce increased Bax levels in HCT116-Insig2-Myc cells, we conclude that Insig2 inhibited apoptosis mediated by Bax.

Figure 5.

Insig2 suppresses Bax expression, activation and binds to the activated form of Bax. (a) Insig2 inhibits apoptosis induced by staurosporine (75 nM for 18 hr) and actinomycin D (1.5 μg/ml for 24 hr). The cells and flow cytometry analysis were similar that described in Figs. 3a and 3b, (b) HCT116-Insig2-Myc clones and mock-transfected cells were treated with 100 μM ETO for 24 hr. The lysates were prepared with Chaps buffer or NP-40 buffer, immunoprecipitated with anti-Bax (6A7) and probed with anti-Bax (N20). (c) Activation of Bax was inhibited by Insig2. Insig2-Myc stably transfected HCT116 and mock cells were treated with 100 μM ETO for 24 hr, fixed and stained with anti-Bax (N20). The images were taken by Leica DMLB upright fluorescent microscope with QIMaging camera, the scale bar =20 μm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

Since inactive Bax resides in the cytosol of healthy cells and a conformational change, namely the exposure of an amino-terminal epitope of Bax, is required for Bax to translocate to mitochondria in response to apoptotic signals,20,25 we further investigated whether over-expression of Insig2 affected the conformational change of Bax. Both immunoprecipitation and immunofluorescence experiments were performed using antibodies that only recognize the conformationally activated forms of Bax. We found that ETO treatment of mock transfected cells resulted in a significant increase in the level of activated Bax, but only a weak Bax band was found in the immunoprecipitates with the anti-Bax monoclonal antibody (6A7) in Chaps buffer from ETO treated Insig2-Myc transfected HCT116 cells (Fig. 5b). Similarly, immunofluorescence staining with the anti-Bax antibodies N20, 6A7 and NT demonstrated that cells stably transfected with Insig2-Myc was resistant to ETO-induced Bax conformational change. In contrast, mock transfected cells exhibited a dramatic increase of activated Bax when treated with ETO (Fig. 5c, not shown are the immunofluorescent staining with 6A7 and NT). Thus, in response to chemotherapeutic drugs, the immunoprecipitation data shows that Insig2 directly binds the activated form of Bax and the immunofluorescent analyses show Insig2 and activated Bax colocalize in the cell.

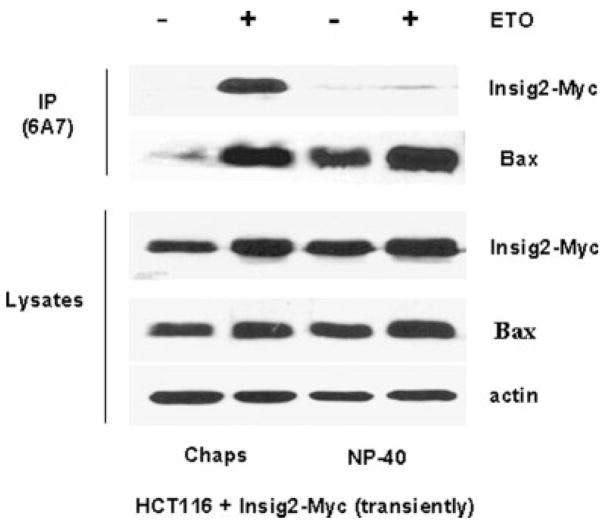

We further examined the interaction between Insig2 and Bax. Using both ETO-treated and untreated Insig2-Myc transiently transfected HCT116 cells, lysates were prepared with a Chaps buffer, where Bax neither dimerizes nor causes the exposure of 6A7 epitope or with NP-40 buffer where Bax can undergo both homo- and heterodimerization and does cause the exposure of the 6A7 epotope.26 As shown in Figure 6, the ETO treatment induced Bax activation substantially increased compared to the ETO untreated control. In the Chaps lysis buffer, Insig2-Myc was coprecipitated with conformationally changed Bax by the 6A7 conformation specific anti-Bax antibody. In the NP-40 lysis buffer, the 6A7 conformation specific anti-Bax antibody pulled down nearly equivalent amounts of Bax with or without ETO treatment, proving the NP-40 induces a conformation change in Bax to expose the relevant 6A7 epitope, but the Chaps lysis buffer does not induce a conformation change. Even though NP-40 lysis buffer creates more “activated” Bax, almost no Insig2-Myc is coimmunoprecipitated with the 6A7 conformation specific anti-Bax. These immunoprecipitation experiments demonstrate that Insig2-Myc binds to activated Bax prior to cell lysis and does not bind to Bax artificially “activated” by NP-40.

Figure 6.

Insig2 binds to activated Bax. HCT116 cells were transiently transfected with Insig2-Myc overnight and then treated with ETO for 24 hr. Immunoprecipitation was similar as in Fig. 5b. Fifty microgram of each lysate was run on the gel as direct loading control. Western blots were probed with antibodies against Bax, Insig2-Myc and β-Actin.

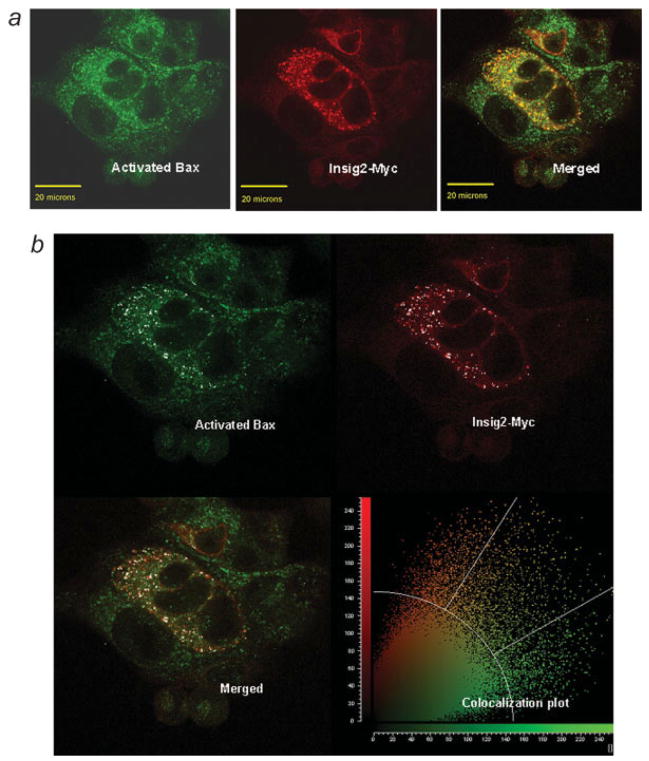

The coprecipitation of Insig2-Myc with the active form of Bax suggested an association (binding) between the 2 proteins. Furthermore, the confocal analysis of Insig2-Myc transiently transfected cells indicated that Insig2-Myc colocalized with activated Bax induced by ETO treatment (Fig. 7a, normal color images and Fig. 7b, a plot prepared by incorporating all the pixels in the same cells). Both earlier results from immunoprecipitation and immunofluorescent staining experiments suggest a specific interaction between activated Bax and Insig2.

Figure 7.

The colocalization between Insig2 and Bax. (a) Normal color confocal images of Insig2-Myc (in red) and activated Bax (in green) and merged colocalization (in orange). The Insig2-Myc was transiently transfected into HCT116 cells and treated with ETO to induce Bax activation. The scale bar equals 20 μm. (b) A colocalization plot was prepared incorporating all the pixels in the entire image. The background thresholds were set to 58% (or an intensity of 148) and the individual channel thresholds were each set to 60% (or an intensity of 153), meaning that any pixels lower than these percentages on the threshold scale (0–255) are not considered colocalized. The white spots on the image represent pixels that are above these thresholds in both color channels. Thus the white spot pixels have a high intensity in both the green and the red channels. Additionally the white spots are a mask to highlight these pixels.

Insig2 also localizes to mitochondria and blocks cytochrome c release

Since Bax is known to translocate to mitochondria in response to death signals and to mediate cellular apoptosis by inducing mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization,17,18,27 we next examined if Insig2 inhibited apoptosis by affecting Bax relocation from the cytoplasm to mitochondria. We isolated mitochondria from Insig2-Myc stably-transfected and mock-transfected HCT116 cells and then checked for Bax expression by Western blot analysis. As shown in Figure 8a, ETO treatment notably increased the Bax levels in both cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions of mock transfected HCT116 cells. The Bax levels, however, were nearly identical in the mitochondrial fraction of ETO treated and untreated Insig2-Myc transfected cells, indicating that the Bax translocation from cytoplasm to mitochondria triggered by chemotherapy was effectively blocked by Insig2. Since the total Bax levels of whole cells exhibited a similar pattern (Fig. 5b), it seems that Insig2 affected not only Bax expression but also its relocation from the cytoplasm to mitochondria. To ensure the accuracy of subcellular fractionation, we tested the cytoplasmic and mitochondrial fractions with antibodies for β-ACTIN, PERK and COX-IV which are specific for the cytoplasmic, ER and mitochondrial fractions, respectively. As expected, Insig2-Myc was found in the cytoplasmic fraction (Fig. 8a), since Insig2 is reported to be an integral ER membrane protein.1,3 But surprisingly, the Insig2-Myc was also found substantially in the mitochondrial fraction (Fig. 8a). Testing the fractions for an ER specific protein showed only a weak signal for the PERK protein suggesting the presence of a small amount of ER contamination in the mitochondrial fraction which might explain the presence of the Insig2-Myc in the mitochondrial fraction instead of the normal ER location. Moreover, the release of cytochrome C into cytoplasm was also significantly suppressed by expression of Insig2-Myc (Fig. 8a). The Western blot results show that Insig2 appeared in mitochondrial fraction indicated that Insig2 may be also localized to and even expressed in either the mitochondria or the contaminating ER.

Figure 8.

Insig2 also localized to mitochondria, blocked the release of cytochrome c. (a) Western blot with cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions from ETO-treated and untreated cells of mixed 3 HCT116-Insig2-Myc clones. Cytochrome oxidase subunit IV (COX IV), PERK and β-ACTIN served as the markers of mitochondria, ER, and loading, respectively. The same lysates were used on multiple western blots. (b) Colocalization between Insig2-Myc and mitochondria. The cells and treatment were same as that in Figure 5, and costained with MitoTracker (Red) and anti-Myc antibody (Green). Images were captured by confocal microscopy as stated in Material and methods section. The scale bar =20 μm.

To further support that Insig2 might be localized to the mitochondria, immunofluorescent confocal microscopy was done. The anti-Myc staining produced a punctate pattern of Insig2-Myc that is either superimposed or adjacent to mitochondria detected by the MitoTracker probe (Fig. 8b). Coupled with the Western blot data for the subcellular fractions, coprecipitation results, and imaging linking Bax to Insig2-Myc, these data strongly suggest that Insig2 is localized to mitochondria or in an ER fraction near the mitochondria.

Insig2 regulates other effecter genes related to apoptosis

To further investigate if Insig2 also regulates other downstream “effecter” genes related to apoptosis and cell invasion, a comparison of genes expressed in 3 HCT116-Insig2-Myc clones versus mock cells was carried out using human Affymetrix U133 plus 2.0 gene expression microarrays. In Table I, we identify those prominently over or under expressed genes related to cell apoptosis, cholesterol synthesis and invasion. Insig2 expression down-regulates a few proapoptotic genes: Bik, Bclxs, AIFM2, and upregulates survival protein interferon (-inducible protein 6 (G1P3). Of these, Bik is a novel apoptosis-inducing protein which shares a critical BH3 domain with other death-promoting proteins such as Bax and Bak28,29 and Bclxs acts as an apoptotic activator.30 AIFM2 is an apoptosis-inducing factor, whose over-expression has been shown to induce apoptosis.31 G1P3 is an antiapoptosis gene, which localizes to mitochondria and inhibits mitochondria-mediated apoptosis.32 In addition, Insig2 down-regulated SREBP1 by 2-fold and up-regulated genes related to extracellular matrix, cell adhesion and migration, such as FN1 and contactin 1,33,34 generating new observations warranting further investigation.

TABLE I.

THE GENES AFFECTED BY INSIG2

| Relative gene expression |

Accession no. | Gene name | Gene symbol | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mock | Insig2 clones | |||

| 1475.1 | 1069.7 | NM_001197 | bcl2-interacting killer | Bik |

| 1166.7 | 831.6 | NM_001191 | bcl2l1/bclxs | bcl2L1/bclxs |

| 1205.2 | 538.1 | NM_032797 | Apoptosis-inducing factor mitochondrion-associated 2 | AIFM2 |

| 581.4 | 1488.1 | NM_002038 | Interferon alpha-inducible protein 6 | G1P3 |

| 763.2 | 382.5 | NM_004176 | Sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1 transcript variant 2 | SREBP1 |

| 84.6 | 220.7 | NM_002026 | Fibronectin 1 | FN1 |

| 30.9 | 155.9 | NM_001843 | Contactin 1 | CNTN1 |

Discussion

Here we report that Insig2 was validated as a novel biomarker for predicting poor prognosis and survival for human colon cancer. The experiments using colon cancer cell line HCT116 cells transfected with Insig2 further demonstrated that Insig2 promotes cell growth and inhibits cellular apoptosis through suppression of Bax expression as well as the binding of activated Bax. These are new apparent functions for Insig2, previously reported to be a cholesterol synthesis regulator and an ER protein.

Colorectal cancer is the second most common cause of cancer death in the United States. Detecting malignant neoplasms at an early stage offers clinical advantages; however, it is often diagnosed at a late stage with concomitant poor prognosis. Although the modified Dukes’ staging system provides adequate prognostic information for colorectal cancer patients staged as A or D, the intermediate stages of B and C are not extremely useful in discriminating good from poor prognosis patients. It also results in potential for over or under-treatment of a large number of patients and can only be applied after complete surgical resection. Microarray technology has produced multiorgan cancer classifiers,35,36 discovery of progression markers,37,38 and prediction of disease outcome in some types of cancer.39,40 Molecular staging shows promise in predicting the long-term outcome of any individual based on the gene expression profile of the tumor at the time of diagnosis. The use of molecular biomarkers offers both convenience and accuracy compared to other detection methods.41,42 Examining Insig2 expression in 205 primary human colon cancer samples confirmed previous experiments suggesting that Insig2 may be a novel biomarker for predicting poor human colon cancer prognosis and survival. We subsequently hypothesized that a biomarker with substantial prognostic value might have biological underpinnings.

The experiments using colon cancer cell lines transfected with Insig2 demonstrated that Insig2 promotes cell growth and inhibits cell apoptosis through suppression of Bax expression and subsequent binding of activated Bax. Additional experiments provide new data suggesting that Insig2 may also down regulate Bik, Bclxs, AIFM2 and up regulate anti-apoptotic G1P3. Insig2 also localizes to either mitochondria or ER membranes adjacent to the mitochondria, which further supports its role in inhibiting apoptosis mediated by mitochondria. Interestingly, the Insig2 regulated genes, AIFM2 and G1P3 also co-localize with mitochondria.31,32 It is thus rational to suggest that Insig2 regulates both anti and proapoptotic proteins associated with mitochondria to protect the cell from apoptosis.

Activation of Bax with the detergent NP-40 to expose the amino terminal epitope recognized by the 6A7 antibody is not sufficient for the binding of Insig2 to activated Bax. Nor is the binding of Insig2 to Bax an artifact of cell lysis, since the binding occurs only with Chaps lysis buffer. This observation may suggest that additional steps are needed for the activation of Bax that is not replicated by the NP-40 lysis buffer or that the NP-40 lysis buffer disrupts a key interaction between Insig2 and Bax that is not affected by Chaps lysis buffer. It is possible that Insig2 binding to 6A7 positive conformer of Bax in ETO treated cells blocks the subsequent positive amplification of Bax conformational changes, mitochondrial integration and apoptosis. It is well accepted in gen eral that the small portion of initially activated Bax plays a role in positive feedback regulation of Bax activation. For example, the antiapoptotic Bcl-2 or Bcl-XL protein only interacts with conformationally changed Bax43; however, over-expression of Bcl-2 blocks Bax conformational change and mitochondrial translocation in response to apoptotic signals.44 Similarly, the anti-apopto-tic viral protein M11L only interacts with Bax after death stimulation and over-expression of M11L suppresses Bax activation and apoptosis.45

The presence of the ER specific protein PERK in the mitochon-drial fraction prevents concluding that Insig2 interacts with activated Bax only at the mitochondrial membrane but suggests a role for the ER membrane. Since Insig2 is a known ER protein and Bax is reported to also localize to the ER, makes this a plausible scenario. Indeed, the immunofluorescent studies show not only direct co-localization of Bax and Insig2 but the images also show many places where Bax and Insig2 sites are nearly touching. These sites might be areas where the mitochondria and ER membranes are in physical close association within the cell.

It is reasonable to hypothesize that the new and previous reported functions of Insig2 might be linked in some fashion. Insig2 is a regulatory protein that restricts the cholesterol biosynthetic pathway by preventing proteolytic activation of SREBPs and by enhancing degradation of HMG-CoA reductase, which assures cholesterol homeostasis.1,3,8 This relationship was supported by our finding that Insig2 down-regulates the expression of SREBP1, providing the new data supporting its known role in negatively regulating cholesterol synthesis. There is also a curious, but well known epidemiological association between low serum cholesterol levels and an increased risk for colon cancer development.46,47 Moreover, the Insig1 and Insig2 double-knockout mice over accumulated cholesterol and triglycerides in liver.7 Our findings suggest, for the first time, a reasonable connection between Insig2, cholesterol synthesis, mitochondria-mediated apoptosis and colon cancer development. Thus, we propose a model for how Insig2 might reduce cellular cholesterol levels and promote cancer malignancy. Namely, elevated levels of Insig2 prevent the transcriptional activation of genes required for cholesterol synthesis, which may result in low cholesterol levels in target tissues (and blood) that has been associated with the risk of colon cancer development. The elevated levels of Insig2 may also prevent the expression and activation of Bax, down-regulating proapoptotic genes Bik, Bclxs, AIFM2 and upregulating antiapoptotic G1P3 expression, blocking the subsequent initiation of an apoptotic cascade. While the precise mechanisms responsible for elevation of Insig2 levels in human colon cancer, and for a connection between Insig2 and Bax, Bik, Bclxs, AIFM2 and G1P3 warrant further investigation, our results demonstrate that Insig2 could serve as a novel biomarker for colorectal cancer and a potential tumor promoter with multiple, potentially related, biological functions. These functions principally include the regulation of cholesterol synthesis, the promotion of tumorigenicity and cellular proliferation, and the inhibition of mitochondria-mediated apoptosis.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank Dr. Joseph Goldstein for pCMV-Insig2-Myc plasmid information; Ms. Jodi Kroeger, Ms. Melissa Makris and Ms. Johana Melendez; Mr. Mark C. Lloyd, Ms. Nancy Burke and Mr. Joe Johnson; and Ms. LanMin Zhang for technical assistance in apoptosis, microscopy and microarray assay, from the core laboratories at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute. They are also grateful to Dr. Dung-Tsa Chen for help with statistical analysis and Ms. Magaly Mendez for partial manuscript preparation and the members of the Yeatman lab for helpful discussion.

References

- 1.Yabe D, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Insig-2, a second endoplasmic reticulum protein that binds SCAP and blocks export of sterol regulatory element-binding proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12753–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162488899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang T, Espenshade PJ, Wright ME, Yabe D, Gong Y, Aebersold R, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Crucial step in cholesterol homeostasis: sterols promote binding of SCAP to INSIG-1, a membrane protein that facilitates retention of SREBPs in ER. Cell. 2002;110:489–500. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00872-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldstein JL, DeBose-Boyd RA, Brown MS. Protein sensors for membrane sterols. Cell. 2006;124:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gong Y, Lee JN, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, Ye J. Juxtamembranous aspartic acid in Insig-1 and Insig-2 is required for cholesterol homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:6154–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601923103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sever N, Song BL, Yabe D, Goldstein JL, Brown MS, DeBose-Boyd RA. Insig-dependent ubiquitination and degradation of mammalian 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase stimulated by sterols and geranylgeraniol. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52479–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310053200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sever N, Yang T, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, DeBose-Boyd RA. Accelerated degradation of HMG CoA reductase mediated by binding of insig-1 to its sterol-sensing domain. Mol Cell. 2003;11:25–33. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00822-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engelking LJ, Liang G, Hammer RE, Takaishi K, Kuriyama H, Evers BM, Li WP, Horton JD, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Schoenheimer effect explained–feedback regulation of cholesterol synthesis in mice mediated by Insig proteins. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2489–98. doi: 10.1172/JCI25614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engelking LJ, Evers BM, Richardson JA, Goldstein JL, Brown MS, Liang G. Severe facial clefting in Insig-deficient mouse embryos caused by sterol accumulation and reversed by lovastatin. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2356–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI28988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eschrich S, Yang I, Bloom G, Kwong KY, Boulware D, Cantor A, Coppola D, Kruhoffer M, Aaltonen L, Orntoft TF, Quackenbush J, Yeatman TJ. Molecular staging for survival prediction of colorectal cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3526–35. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schulze PC, De Keulenaer GW, Yoshioka J, Kassik KA, Lee RT. Vitamin D3-upregulated protein-1 (VDUP-1) regulates redox-dependent vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation through interaction with thioredoxin. Circ Res. 2002;91:689–95. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000037982.55074.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irby RB, Mao W, Coppola D, Kang J, Loubeau JM, Trudeau W, Karl R, Fujita DJ, Jove R, Yeatman TJ. Activating SRC mutation in a subset of advanced human colon cancers. Nat Genet. 1999;21:187–90. doi: 10.1038/5971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamaguchi H, Chen J, Bhalla K, Wang HG. Regulation of Bax activation and apoptotic response to microtubule-damaging agents by p53 transcription-dependent and -independent pathways. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:39431–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401530200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duan H, Chinnaiyan AM, Hudson PL, Wing JP, He WW, Dixit VM. ICE-LAP3, a novel mammalian homologue of the Caenorhabditis elegans cell death protein Ced-3 is activated during Fas- and tumor necrosis factor-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1621–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.3.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li P, Nijhawan D, Budihardjo I, Srinivasula SM, Ahmad M, Alnemri ES, Wang X. Cytochrome c and dATP-dependent formation of Apaf-1/cas-pase-9 complex initiates an apoptotic protease cascade. Cell. 1997;91:479–89. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80434-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolf BB, Green DR. Suicidal tendencies: apoptotic cell death by caspase family proteinases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:20049–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Germain M, Affar EB, D’Amours D, Dixit VM, Salvesen GS, Poirier GG. Cleavage of automodified poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase during apoptosis. Evidence for involvement of caspase-7. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28379–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Narita M, Shimizu S, Ito T, Chittenden T, Lutz RJ, Matsuda H, Tsujimoto Y. Bax interacts with the permeability transition pore to induce permeability transition and cytochrome c release in isolated mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14681–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nechushtan A, Smith CL, Hsu YT, Youle RJ. Conformation of the Bax C-terminus regulates subcellular location and cell death. EMBO J. 1999;18:2330–41. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reed JC, Green DR. Remodeling for demolition: changes in mitochondrial ultrastructure during apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2002;9:1–3. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00437-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolter KG, Hsu YT, Smith CL, Nechushtan A, Xi XG, RJ Y. Movement of Bax from the cytosol to mitochondria during apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1281–92. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.5.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang L, Yu J, Park BH, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Role of BAX in the apoptotic response to anticancer agents. Science. 2000;290:989–92. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5493.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arnoult D, Parone P, Martinou JC, Antonsson B, Estaquier J, Ameisen JC. Mitochondrial release of apoptosis-inducing factor occurs downstream of cytochrome c release in response to several proapoptotic stimuli. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:923–9. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang S, El-Deiry WS. Requirement of p53 targets in chemosensitization of colonic carcinoma to death ligand therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15095–100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2435285100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamaguchi H, Bhalla K, Wang HG. Bax plays a pivotal role in thapsigargin-induced apoptosis of human colon cancer HCT116 cells by controlling Smac/Diablo and Omi/HtrA2 release from mitochondria. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1483–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schinzel A, Kaufmann T, Schuler M, Martinalbo J, Grubb D, Borner C. Conformational control of Bax localization and apoptotic activity by Pro168. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:1021–32. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsu YT, Youle RJ. Bax in murine thymus is a soluble monomeric protein that displays differential detergent-induced conformations. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10777–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang H, Kim JK, Edwards CA, Xu Z, Taichman R, Wang CY. Clusterin inhibits apoptosis by interacting with activated Bax. Nature Cell Biol. 2005;7:909–15. doi: 10.1038/ncb1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tong Y, Yang Q, Vater C, Venkatesh LK, Custeau D, Chittenden T, Chinnadurai G, Gourdeau H. The pro-apoptotic protein. Bik, exhibits potent antitumor activity that is dependent on its. BH3 domain. Mol Cancer Ther. 2001;1:95–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boyd JM, Gallo GJ, Elangovan B, Houghton AB, Malstrom S, Avery BJ, Ebb RG, Subramanian T, Chittenden T, Lutz RJ, et al. Bik, a novel death-inducing protein shares a distinct sequence motif with Bcl-2 family proteins and interacts with viral and cellular survival-promoting proteins. Oncogene. 1995;11:1921–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boise LH, Gonzalez-Garcia M, Postema CE, Ding L, Lindsten T, Turka LA, Mao X, Nunez G, Thompson CB. bcl-x, a bcl-2-related gene that functions as a dominant regulator of apoptotic cell death. Cell. 1993;74:597–608. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90508-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu M, Xu LG, Li X, Zhai Z, Shu HB. AMID, an apoptosis-inducing factor-homologous mitochondrion-associated protein, induces caspase-independent apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25617–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202285200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tahara E, Jr, Tahara H, Kanno M, Naka K, Takeda Y, Matsuzaki T, Yamazaki R, Ishihara H, Yasui W, Barrett JC, Ide T, Tahara E. G1P3, an interferon inducible gene 6–16, is expressed in gastric cancers and inhibits mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis in gastric cancer cell line TMK-1 cell. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54:729–40. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0645-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berglund EO, Ranscht B. Molecular cloning and in situ localization of the human contactin gene (CNTN1) on chromosome 12q11-q12. Genomics. 1994;21:571–82. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Su JL, Yang CY, Shih JY, Wei LH, Hsieh CY, Jeng YM, Wang MY, Yang PC, Kuo ML. Knockdown of contactin-1 expression suppresses invasion and metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2553–61. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramaswamy S, Tamayo P, Rifkin R, Mukherjee S, Yeang CH, Angelo M, Ladd C, Reich M, Latulippe E, Mesirov JP, Poggio T, Gerald W, et al. Multiclass cancer diagnosis using tumor gene expression signatures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:15149–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211566398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bloom G, Yang IV, Boulware D, Kwong KY, Coppola D, Eschrich S, Quackenbush J, Yeatman TJ. Multi-platform, multi-site, microarray-based human tumor classification. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:9–16. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63090-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agrawal D, Chen T, Irby R, Quackenbush J, Chambers AF, Szabo M, Cantor A, Coppola D, Yeatman TJ. Osteopontin identified as colon cancer tumor progression marker. C R Biol. 2003;326:1041–3. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanchez-Carbayo M, Socci ND, Lozano JJ, Li W, Charytonowicz E, Belbin TJ, Prystowsky MB, Ortiz AR, Childs G, Cordon-Cardo C. Gene discovery in bladder cancer progression using cDNA microarrays. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:505–16. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63679-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van ’t Veer LJ, Dai H, van de Vijver MJ, He YD, Hart AA, Mao M, Peterse HL, van der Kooy K, Marton MJ, Witteveen AT, Schreiber GJ, Kerkhoven RM, et al. Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer. Nature. 2002;415:530–6. doi: 10.1038/415530a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shipp MA, Ross KN, Tamayo P, Weng AP, Kutok JL, Aguiar RC, Gaasenbeek M, Angelo M, Reich M, Pinkus GS, Ray TS, Koval MA, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma outcome prediction by gene-expression profiling and supervised machine learning. Nat Med. 2002;8:68–74. doi: 10.1038/nm0102-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Srivastava S, Verma M, Henson DE. Biomarkers for early detection of colon cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1118–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ward DG, Suggett N, Cheng Y, Wei W, Johnson H, Billingham LJ, Ismail T, Wakelam MJ, Johnson PJ, Martin A. Identification of serum biomarkers for colon cancer by proteomic analysis. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1898–905. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hsu YT, Wolter KG, Youle RJ. Cytosol-to-membrane redistribution of Bax and Bcl-X(L) during apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3668–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murphy KM, Streips UN, Lock RB. Bcl-2 inhibits a Fas-induced conformational change in the Bax N terminus and Bax mitochondrial translocation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17225–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C900590199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Su J, Wang G, Barrett JW, Irvine TS, Gao X, McFadden G. Myxoma virus M11L blocks apoptosis through inhibition of conformational activation of Bax at the mitochondria. J Virol. 2006;80:1140–51. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.3.1140-1151.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nomura AMSG, Chyou PH. Prospective study of serum cholesterol levels and large-bowel cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83:1403–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.19.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kreger BEAK, Schatzkin A, Splansky GL. Serum cholesterol level, body mass index, and the risk of colon cancer. The Framingham Study Cancer. 1992;70:1038–43. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920901)70:5<1038::aid-cncr2820700505>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]