Abstract

Lipoxin A4 is an eicosanoid that plays a key role in the resolution of neutrophilic inflammation. In these studies, we investigated the hypothesis that responses to lipoxin A4 are impaired in neonates, relative to adults. Lipoxin A4 was found to inhibit chemotaxis and respiratory burst in adult neutrophils. In contrast, it had no effect on these activities in neonatal neutrophils. In addition, while lipoxin A4 augmented apoptosis in LPS-treated adult neutrophils, apoptosis in neonatal cells was not affected by lipoxin A4 alone or in combination with LPS. The biologic actions of anti-inflammatory eicosanoids are mediated, in part, via the transcription factor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ). Expression of PPAR-γ mRNA and its target gene, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, were significantly reduced in neonatal cells when compared to adult cells. Moreover, whereas treatment of adult neutrophils with lipoxin A4 increased PPAR-γ expression, no effects were observed in neonatal cells. 5- and 15-lipoxygenase, enzymes required for the synthesis of lipoxin A4, were also reduced in neonatal neutrophils. These findings suggest that the anti-inflammatory activity of lipoxin A4 is impaired in neonatal neutrophils and that this is due, in part, to reduced PPAR-γ signaling. This may contribute to diseases associated with chronic inflammation in neonates.

Keywords: lipoxin, neutrophil, inflammation, neonatal

Inflammatory diseases in newborns are characterized by the persistence of activated neutrophils in tissues. These cells release oxidants, eicosanoids, and pro-inflammatory cytokines, which are thought to contribute to tissue injury (1). Neutrophils are normally cleared from inflammatory sites by apoptosis (2). Prolonged survival of neonatal neutrophils at sites of injury is thought to be important in the development of conditions such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) and necrotizing enterocolitis (3, 4). The fact that older children and adults do not develop these diseases suggests that neonates have developmental impairments in neutrophil clearance. In this regard, we have previously demonstrated that apoptosis is reduced in neonatal neutrophils relative to adults (5).

Lipoxin A4 is an anti-inflammatory eicosanoid generated from arachidonic acid by the actions of lipoxygenases (Lox) (6, 7). Recent data suggest that lipoxin A4 plays a key role in the resolution of neutrophil inflammation (8, 9). Thus, lipoxin A4 inhibits neutrophil chemotaxis and adhesion (6, 10, 11), blocks calcium mobilization and phagocyte oxidase activity, inhibits nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and activator protein-1 (AP-1) activation, and decreases inflammatory cytokine production and peroxynitrite generation (12-15). Lipoxins also promote the non-phlogistic removal of these cells by macrophages (6, 9, 16) and may stimulate apoptosis in neutrophils exposed to inflammatory stimuli (17). We speculated that responses to lipoxin A4 are impaired in neonatal neutrophils, contributing to prolonged longevity and activity of these cells. To investigate this, we compared the effects of lipoxin A4 on adult and neonatal neutrophils. Signaling pathways mediating the actions of lipoxin A4 were also analyzed. Whereas in adult neutrophils, lipoxin A4 suppressed chemotaxis and respiratory burst activity, and augmented apoptosis, minimal effects were observed in neonatal cells. This was associated with reduced activity of the transcription factor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ). These data suggest a potential mechanism underlying the increased susceptibility of neonates to chronic inflammatory diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Annexin V was obtained from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN), and propidium iodide from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). RNA purification kits were purchased from Qiagen (Chatsworth, CA). Primers for RT-PCR were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). Nucleotides and reagents for real-time PCR were from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). Lipoxin A4 was from Calbiochem, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI), and rabbit anti-formyl peptide receptor-like 1 (FPRL1) antibody from ABR-Affinity Bio-reagents (Golden, CO). Normal rabbit serum control was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), and FITC-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Amplex Red and horseradish peroxidase were from Molecular Probes (Carlsbad, CA).

Subjects and neutrophil isolation

Studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of UMDNJ and informed consent obtained from subjects. Umbilical cord blood was obtained from term infants (> 37 weeks gestation) delivered by elective cesarean section before labor between January 2004 and October 2007. Subjects were excluded with clinical evidence of chorioamnionitis or other perinatal bacterial or viral infections. Peripheral venous blood collected from antecubital veins of healthy adult volunteers was used for comparison. Neutrophils were isolated by dextran sedimentation, followed by Ficoll gradient centrifugation and hypotonic lysis of erythrocytes, as previously described (18). More than 95% of cord blood neutrophils exhibited multilobular nuclei, and these cells were not morphologically distinguishable from adult cells. Previous studies have shown that, while cord blood neutrophils exhibit developmental alterations in function, these cells express neutrophil-specific antigens comparably to adult cells (19, 20).

Measurement of neutrophil chemotaxis

Chemotaxis of neutrophils through Nucleopore filters was measured by the modified Boyden chamber technique using a 48-well microchemotaxis chamber, as previously described (21).

Measurement of Apoptosis

Neutrophils were incubated with or without lipoxin A4 (0.3−300 nM) and/or LPS (100 ng/ml) in a shaking water bath for 24 hr. Neutrophils were then centrifuged, resuspended, and incubated (15 min, room temperature) with Annexin V (1:20) and propidium iodide (1:10). Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry on a Beckman-Coulter Cytomics FC 500 (Miami FL). Viable apoptotic and necrotic neutrophil populations were gated electronically and data analyzed using quadrant statistics based on relative Annexin V and propidium iodide fluorescence.

Measurement of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) production

Neutrophils were inoculated into 96-well dishes (5 × 104 cells/well). Fifty microliters of reaction mixture containing Amplex Red (25 μM) and horseradish peroxidase (1.07 U/ml) were added to each well, followed by lipoxin A4 (300 nM), PMA (500 nM), lipoxin A4 + PMA, or PBS control. Fluorescent product formation, indicative of H2O2, was measured spectrophotometrically at 1 min intervals for 10 min using 540 nm excitation and 590 nm emission (22).

Immunofluorescence

Neutrophils (2 × 106 cells/ml) suspended in PBS containing 1% BSA and 0.01% sodium azide (1.5 × 106/ml) were incubated for 60 min at room temperature with a 1:1000 dilution of anti-FPRL1 antibody or control (normal rabbit serum), washed, and then incubated with FITC-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG. After 30 min, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Fluorescence histograms were analyzed by Overton's cumulative subtraction routine of the Coulter Cytologic Software program.

Analysis of mRNA expression

Neutrophils were cultured in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum with PGE2 (300 nM) or medium control for 5 hr and then with LPS (100 ng/ml), lipoxin A4 (0.3−300 nM), or control for an additional 4 hr. RNA was isolated for real time PCR using RNEasy (Quiagen, Chatsworth CA). Real time PCR was performed using the SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's protocol and amplified on the ABI Prism 7900 sequence detection system, using GAPDH as standard. FPRL1 and β-actin gene expression in freshly isolated cells were analyzed using reverse transcription PCR. RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent and cDNA prepared using a Superscript III RT kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The conditions for PCR amplification were denaturation for 30 sec at 94°C, annealing at 55°C for 30 sec, and elongation for 30 sec at 72°C, using 25 cycles. The PCR products were analyzed on a 2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide and quantified by densitometry. Full-length coding sequences for the genes to be analyzed were obtained from GenBank™ (National Center for Biotechnology Information).

Data analysis

Experiments were repeated 3−8 times. Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica 5.5 (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK). The effects of treatments by group were compared by 2×4 ANOVA. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

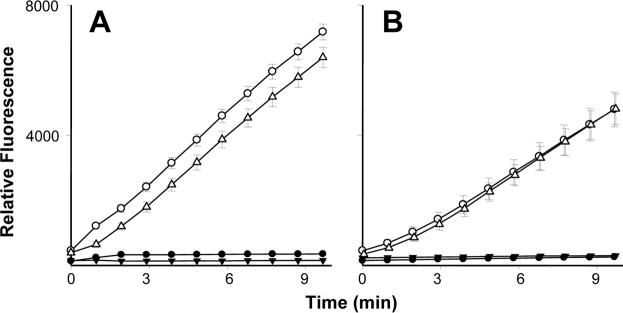

Initially, we compared the effects of lipoxin A4 on neutrophil chemotaxis in adult and neonatal neutrophils. The bacterially derived peptide fMLP readily induced chemotaxis in both cell types (Fig. 1, upper panel). Neutrophils from neonates were significantly less responsive to fMLP when compared to cells from adults, which is consistent with previous reports (21). Pretreatment of adult neutrophils with lipoxin A4 resulted in a significant reduction in fMLP-induced chemotaxis. In contrast, lipoxin A4 had no effect on the fMLP response in neonatal cells. Lipoxin A4 by itself had no effect on random migration or chemotaxis in either adult or neonatal neutrophils. We next compared the effects of lipoxin A4 on apoptosis in neutrophils from adults and neonates. Propidium iodide-positive cells did not exceed 3% in any sample, indicating that lipoxin A4 did not increase necrosis of neutrophils from adults or neonates (not shown). Spontaneous apoptosis, assayed after 24 hr in culture, was significantly reduced in neonatal, relative to adult neutrophils (Fig. 1, lower panel), and lipoxin A4 by itself had no effect on this activity in adult or neonatal cells. The addition of bacterially derived LPS to the cultures suppressed apoptosis in both cell types. Since some investigators have reported biologic activity of lipoxin A4 at low doses (23, 24), the effects of lipoxin A4 at concentrations from 0.3−300 nM on LPS-induced suppression of neutrophil apoptosis were then examined. While the addition of lipoxin A4 (100 and 300 nM) augmented apoptosis in LPS-treated adult neutrophils, neonatal neutrophils were not responsive to lipoxin A4 at any concentration.

Figure 1. Effects of lipoxin A4 on neutrophil chemotaxis and apoptosis.

A) Chemotaxis of adult (■) and neonatal  neutrophils in response to fMLP (Ctl/fMLP), lipoxin A4 (Ctl/LXA4), or medium control (Ctl) was assayed using microwell chambers and quantified as the number of cells migrated per 10 high-power fields. In some experiments, cells were treated with lipoxin A4 (LXA4, 300 nM) for 1 hr before measurement of chemotaxis toward fMLP (LXA4/fMLP) or medium control (LXA4/Ctl). B) Adult and neonatal neutrophils were incubated in a shaking water bath (37°C) with medium control (Ctl), LPS (100 ng/ml), lipoxin A4 (LXA4, 300 nM), or the combination of LPS and LXA4 (0.3−300 nM) for 24 hr. Cells were then labeled with Annexin V and propidium iodide and assayed for apoptosis by flow cytometry. Data were analyzed using Coulter quadrant statistics based on relative fluorescence binding of Annexin V and propidium iodide. Each bar represents the mean ± SE (n = 3). *Significantly different (p<0.05) from adult; **Significantly different (p<0.05) from Ctl; Significantly different † (p<0.05) from Ctl/fMLP; ‡Significantly different (p< 0.05) from LPS

neutrophils in response to fMLP (Ctl/fMLP), lipoxin A4 (Ctl/LXA4), or medium control (Ctl) was assayed using microwell chambers and quantified as the number of cells migrated per 10 high-power fields. In some experiments, cells were treated with lipoxin A4 (LXA4, 300 nM) for 1 hr before measurement of chemotaxis toward fMLP (LXA4/fMLP) or medium control (LXA4/Ctl). B) Adult and neonatal neutrophils were incubated in a shaking water bath (37°C) with medium control (Ctl), LPS (100 ng/ml), lipoxin A4 (LXA4, 300 nM), or the combination of LPS and LXA4 (0.3−300 nM) for 24 hr. Cells were then labeled with Annexin V and propidium iodide and assayed for apoptosis by flow cytometry. Data were analyzed using Coulter quadrant statistics based on relative fluorescence binding of Annexin V and propidium iodide. Each bar represents the mean ± SE (n = 3). *Significantly different (p<0.05) from adult; **Significantly different (p<0.05) from Ctl; Significantly different † (p<0.05) from Ctl/fMLP; ‡Significantly different (p< 0.05) from LPS

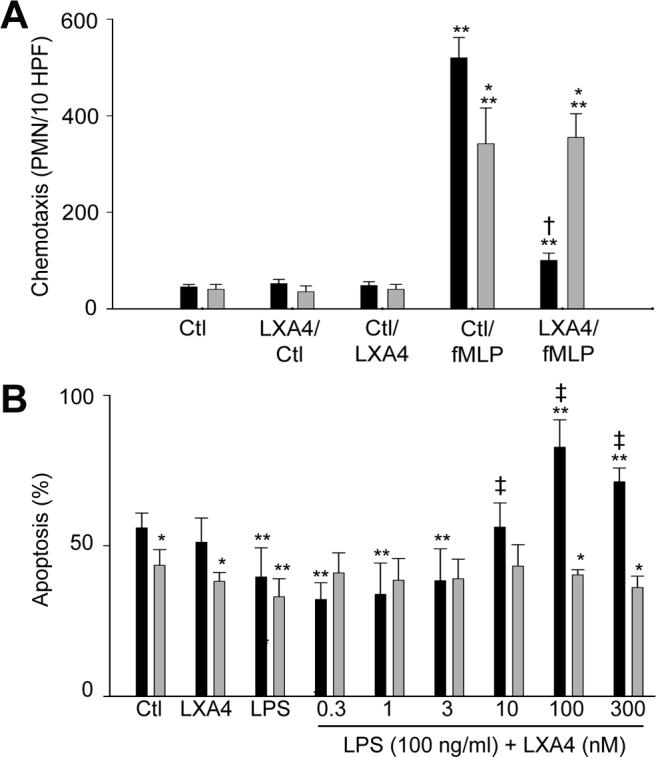

In further studies, we compared the effects of lipoxin A4 on production of H2O2 by adult and neonatal neutrophils. In the absence of stimulation, adult and neonatal neutrophils generated negligible quantities of H2O2 (Fig. 2). Stimulation of both cell types with PMA, a well-established inducer of respiratory burst activity in neutrophils, resulted in increased H2O2 production. Neonatal neutrophils were significantly less responsive to PMA than adult cells. In adult, but not neonatal neutrophils, lipoxin A4 was found to suppress PMA-induced H2O2 production. Lipoxin A4 by itself had no effect on basal oxidative metabolism in either cell type.

Figure 2. Effects of lipoxin A4 on neutrophil respiratory burst activity.

Adult (A) and neonatal (B) neutrophils (5 × 104 cells) were incubated with Amplex Red (25 μM) and horseradish peroxidase (1.07 U/ml), and then treated with lipoxin A4 (LXA4 300 nM, ▲), PMA (500 nM, ○), lipoxin A4 + PMA (△), or PBS control (•). Production of H2O2 was quantified by fluorescence (540 nm excitation, 590 nm emission). Each point represents the mean − SE (n=3). Note that lipoxin A4 significantly (p<0.05) decreased H2O2 production by PMA-treated adult neutrophils at all time points measured. PMA-treated neonatal neutrophils produced significantly (p<0.05) less H2O2 than adult cells at all time points.

Formyl peptide receptor-like 1 (FPRL1) is a G-protein-linked receptor that has been shown to mediate biologic responses to lipoxin A4 (25, 26). We next determined if differences in responses of adult and neonatal neutrophils to lipoxin A4 were associated with altered expression of this receptor. Indirect immunofluorescence and RT- PCR revealed that both adult and neonatal neutrophils expressed FPRL1 protein and mRNA (Fig. 3). Although no differences between the cells were observed in expression of FPRL1 mRNA, protein levels for this receptor were significantly greater in neonatal, when compared to adult cells.

Figure 3. Expression of FPRL1 in neutrophils.

A): FPRL1 gene expression in adult and neonatal neutrophils was analyzed by reverse transcription PCR. PCR products were visualized on an agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide and quantified by densitometry. Data were normalized to β-actin expression. Each bar represents mean ± SE (n=3). Neutrophils from adults (black lines) and neonates (red lines) were incubated with IgG control (B) or anti-FPRL1 antibody (C), followed by FITC-labeled secondary antibody, and analyzed by flow cytometry. One representative histogram from three experiments is shown.

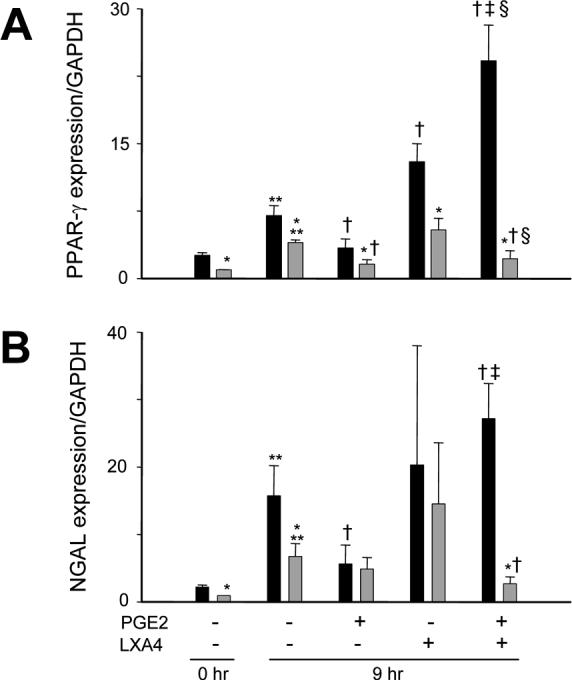

Biologic responses to anti-inflammatory mediators generated via 15-Lox are also mediated via activation of the transcription factor PPAR-γ, which blocks nuclear binding of NF-κB and down-regulates expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (27-30). In further studies, we compared expression of PPAR-γ in adult and neonatal neutrophils. Freshly isolated cells from adult and neonatal neutrophils were found to constitutively express PPAR-γ mRNA. This activity was reduced in neonatal, when compared to adult neutrophils (Fig. 4). Culturing both cell types for 9 hr resulted in increased expression of PPAR-γ. The addition of lipoxin A4 to cultures of adult, but not neonatal neutrophils resulted in further increased PPAR-γ expression.

Figure 4. Effects of lipoxin A4 on expression of PPAR-γ and NGAL.

Neutrophils from adults (■) and neonates  were analyzed immediately after isolation (0 hr) or were incubated with PGE2 (300 nM) or medium control for 5 hr, followed by incubation with LXA4 (300 nM) or medium control for an additional 4 hr. Real time PCR was performed using specific primers for PPAR-γ (A) or NGAL (B), and data normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression. Data are expressed as mean ± SE (n = 6−8). *Significantly different (p<0.05) from adult; **Significantly different (p<0.05) from 0 hr; Significantly different (p<0.05) from untreated 9 hr (PGE2−/LXA4−); ‡Significantly different (p<0.05) from PGE2 alone (PGE2+/LXA4−); Significantly different (p<0.05) from LXA4 alone (PGE2−/LXA4+).

were analyzed immediately after isolation (0 hr) or were incubated with PGE2 (300 nM) or medium control for 5 hr, followed by incubation with LXA4 (300 nM) or medium control for an additional 4 hr. Real time PCR was performed using specific primers for PPAR-γ (A) or NGAL (B), and data normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression. Data are expressed as mean ± SE (n = 6−8). *Significantly different (p<0.05) from adult; **Significantly different (p<0.05) from 0 hr; Significantly different (p<0.05) from untreated 9 hr (PGE2−/LXA4−); ‡Significantly different (p<0.05) from PGE2 alone (PGE2+/LXA4−); Significantly different (p<0.05) from LXA4 alone (PGE2−/LXA4+).

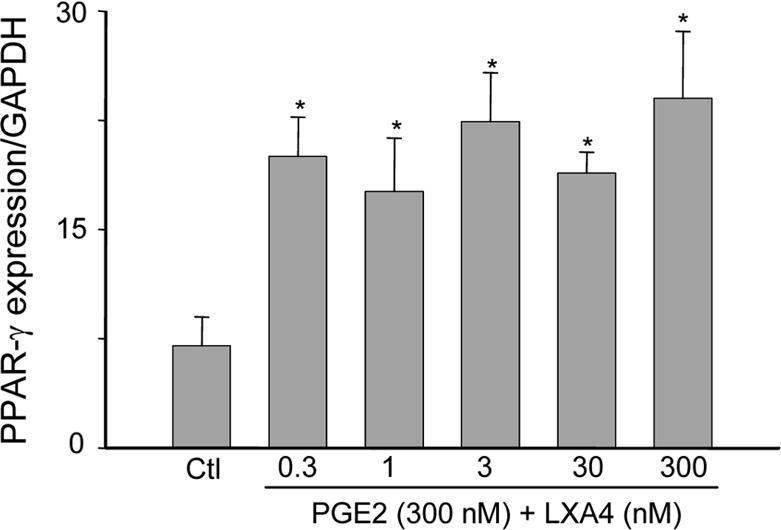

Prolonged exposure to pro-inflammatory mediators such as PGE2 triggers the generation of lipoxin A4 and the down regulation of neutrophilic inflammation (24). We next investigated the effects of PGE2 and lipoxin A4 on PPAR-γ expression. Lipoxin A4, at concentrations between 0.3 and 300 nM, markedly upregulated PPAR-γ in PGE2-treated adult neutrophils; this response was not dose-related in this range (Fig. 5). In contrast, lipoxin A4 had no effect on PPAR-γ expression in neonatal cells pretreated with PGE2 (Fig. 4). To determine if lipoxin A4-induced alterations in PPAR-γ expression were associated with changes in its activity, we analyzed expression of NGAL, a target gene that is up regulated in response to PPAR-γ agonists (31). As observed with PPAR-γ expression, NGAL expression was reduced in freshly isolated neutrophils from neonates relative to adults, and increased in both cell types after 9 hr in culture. In adult cells, incubation with PGE2 reduced NGAL expression. Moreover, the addition of lipoxin A4 to these cultures markedly up regulated expression of NGAL in adult, but not neonatal cells. Lipoxin A4 alone had no significant effect on expression of NGAL in cultured adult or neonatal cells.

Figure 5. Effects of lipoxin A4 concentration on induction of PPAR-γ.

Neutrophils from adults were incubated with PGE2 (300 nM) for 5 hr, followed by LXA4 (0.3−300 nM) or medium control (Ctl) for an additional 4 hr. Real time PCR was performed using specific primers for PPAR-γ, and data normalized to GAPDH expression. Data are expressed as mean ± SE (n = 3). *Significantly different (p<0.05) from Ctl.

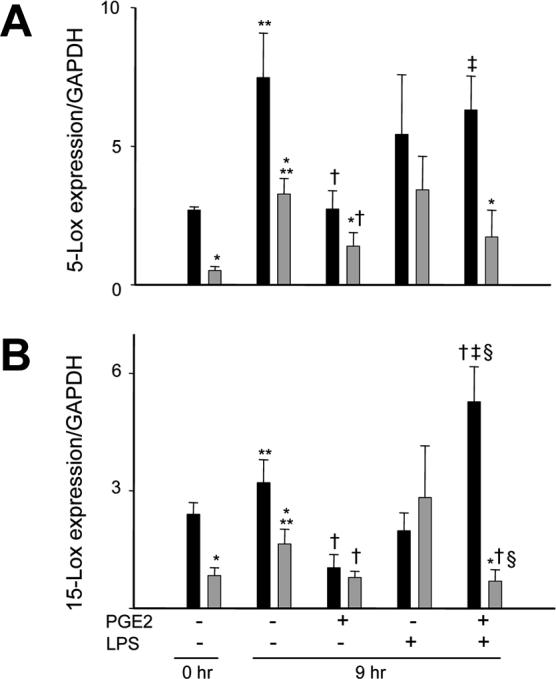

Prolonged inflammatory responses and delayed neutrophil apoptosis in neonates may also be associated with developmental defects in the generation of lipoxin A4. To investigate this, we analyzed expression of 5-Lox and 15-Lox, enzymes required for the synthesis of lipoxin A4 (6). Constitutive expression of 5-Lox and 15-Lox mRNA was detected in both freshly isolated and cultured neutrophils from adults and neonates (Fig. 6). This activity was reduced in neonatal, when compared to adult neutrophils. As observed with PPARγ, in both cell types, constitutive expression of 5-Lox and 15-Lox increased after 9 hr in culture. This activity was suppressed by PGE2. We next examined the effects of bacterially derived LPS, which are known to modulate Lox activity, on expression of these enzymes. While LPS by itself had no significant effect on expression of 5-Lox or 15-Lox, the addition of LPS to cultures of adult cells pretreated with PGE2 significantly increased expression of these enzymes. In contrast, LPS suppressed 15-Lox in PGE2-treated neonatal cells.

Figure 6. Expression of 5-lipoxygenase and 15-lipoxygenase in neutrophils.

Neutrophils from adults (■) and neonates  were analyzed immediately after isolation (0 hr) or were incubated with PGE2 (300 nM) or medium control (Ctl) for 5 hr, followed by incubation with LPS (100 ng/ml) or Ctl for an additional 4 hr. Real time PCR was performed using specific primers for 5-Lox (A) or 15-Lox (B) and data normalized to GAPDH expression. Data are expressed as mean ± SE (n = 4−8). *Significantly different (p<0.05) from adult; **Significantly different (p<0.05) from 0 hr; Significantly different † (p<0.05) from untreated 9 hr (PGE2−/LXA4−); ‡Significantly different (p<0.05) from PGE2 alone (PGE2+/LXA4−); Significantly different § p<0.05 from LPS alone (PGE2−/LPS+).

were analyzed immediately after isolation (0 hr) or were incubated with PGE2 (300 nM) or medium control (Ctl) for 5 hr, followed by incubation with LPS (100 ng/ml) or Ctl for an additional 4 hr. Real time PCR was performed using specific primers for 5-Lox (A) or 15-Lox (B) and data normalized to GAPDH expression. Data are expressed as mean ± SE (n = 4−8). *Significantly different (p<0.05) from adult; **Significantly different (p<0.05) from 0 hr; Significantly different † (p<0.05) from untreated 9 hr (PGE2−/LXA4−); ‡Significantly different (p<0.05) from PGE2 alone (PGE2+/LXA4−); Significantly different § p<0.05 from LPS alone (PGE2−/LPS+).

DISCUSSION

Lipoxin A4 is synthesized by neutrophils late during the inflammatory process and evidence suggests that it is involved in triggering the resolution of the response (24). This is due, in part, to the ability of lipoxin A4 to promote the clearance of senescent neutrophils by macrophages, and to block adhesion and respiratory burst activity (1, 2, 6, 13, 14, 32). Spontaneous apoptosis was reduced in neonatal neutrophils relative to adults, and LPS suppressed apoptosis in both cell types. We also found that, while lipoxin A4 augmented apoptosis in LPS-treated adult cells, neonatal neutrophils were not responsive. While some previous investigators have reported that synthetic analogues of lipoxin do not affect neutrophil survival (13), our finding in LPS-treated adult cells is consistent with previous reports that aspirin-triggered lipoxin and it analogs induce apoptosis in neutrophils exposed to inflammatory stimuli (17). The induction of neutrophil apoptosis by lipoxin A4 under inflammatory conditions may be of biologic importance in reducing oxidant-mediated cytotoxicity. Our findings that neonatal cells are hyporesponsive are consistent with increased susceptibility of neonates to inflammatory diseases and suggest that clearance of neonatal neutrophils from sites of infection is not dependent on lipoxin A4.

Neutrophils accumulate in tissues in response to chemotactic factors generated at sites of infection or injury. Inflammatory cytokines and bacterial-derived products also trigger the generation of reactive oxygen intermediates, which are key in bacterial killing and may also play a role in tissue injury (33). The present studies demonstrate that lipoxin A4 suppressed chemotaxis and respiratory burst activity in adult neutrophils, which is in accord with its anti-inflammatory effects. However, lipoxin A4-induced inhibition of chemotaxis and respiratory burst activity was significantly attenuated or absent in neonatal neutrophils. These findings are consistent with our results on apoptosis and suggest that the ability of lipoxin A4 to abrogate neutrophilic extravasation and limit tissue injury is impaired in neonates.

The biologic activities of lipoxin A4 are mediated, in part, via the membrane-bound G-protein coupled receptor, FPRL1 (also known as ALXR). Despite impaired responsiveness of neonatal neutrophils to lipoxin A4, these cells expressed greater levels of FPRL1 protein than adult cells. These data indicate that expression of FPRL1 is not a rate-limiting step in the response to lipoxin A4 in neonatal neutrophils. It is possible that over-expression of FPRL1 in neonatal neutrophils is a compensatory response to reduced lipoxin A4-mediated activation of downstream signaling pathways. In this regard, we have previously demonstrated that the activities of phosphoinositol-3 kinase and caspase 3, two signaling molecules up regulated following FPRL1 activation, are impaired in neonatal relative to adult neutrophils (5).

PPAR-γ is a nuclear transcription factor that down regulates inflammation (34). In the lung, PPAR-γ agonists have been shown to reduce neutrophil accumulation during endotoxemia (35), and to down regulate Cox-2, ICAM-1 and p-selectin expression (36). PPAR-γ activation triggers expression of target genes such as NGAL, which binds to and sequesters inflammatory mediators, including bacterial formyl peptides and leukotriene B4, and stimulates neutrophil apoptosis (37, 38). Previous studies have implicated 15-Lox and the lipoxin precursor, 15S-HETE, in the activation of PPAR-γ (27-29, 39). Consistent with this, we found that lipoxin A4 up regulated expression of PPAR-γ, as well as NGAL in adult neutrophils. In contrast, no effects were observed in neutrophils from neonates. Moreover, constitutive expression of PPAR-γ was significantly reduced in neonatal neutrophils, when compared to adult cells. These data suggest a potential mechanism underlying persistent activation of neonatal neutrophils at inflammatory sites.

Previous studies have shown that PGE2, which is produced early in the inflammatory response (1−2 hr), functions as a “primer” to induce of pathways important in down regulating the response, including 5-Lox and 15-Lox, which catalyze the generation of anti-inflammatory eicosanoids (24, 40). The present studies demonstrate that exposure of adult neutrophils to PGE2 primed these cells to respond to lipoxin A4, resulting in increased expression of PPAR-γ. In contrast, in neonatal cells pretreated with PGE2, there appear to be developmental defects in responsiveness to lipoxin A4. Thus in neonatal cells, LXA4 reduced expression of PPAR-γ, as well as NGAL. Moreover, lipoxin A4 alone had no significant effect on the cells. Interestingly, although PGE2 down regulated expression of 5-Lox and 15-Lox in both adult and neonatal neutrophils, PGE2 primed neutrophils to respond to LPS, a potent inducer of Lox expression during infection. However, this was only evident in adult cells. Hyporesponsiveness to lipoxin A4 and LPS in neonatal neutrophils, primed by exposure to PGE2 to exhibit the late-inflammatory phenotype, may lead to prolonged activity of pro-inflammatory eicosanoids, and exacerbate tissue injury. Of interest is our observation that culturing neutrophils from both adults and neonates resulted in increased constitutive expression of PPAR-γ, NGAL, and Lox. This may be attributed to changes in cellular responsiveness associated with adherence to culture dishes (41).

The present studies show that the anti-inflammatory effects of lipoxin A4 in neutrophils are reduced in neonatal relative to adult cells. This may be due, in part, to defective activation of PPAR-γ in response to lipoxin A4 during the late phase of the inflammatory response. Impaired activity of lipoxygenases may further contribute to this effect. Previous studies have demonstrated that neutrophil hyporesponsiveness to lipoxin A4 may play a role in the pathogenesis of specific chronic inflammatory diseases in children, such as periodontitis (42, 43). Similarly, developmental impairment of specific lipoxin A4-mediated responses may increase the susceptibility of neonates to prolonged neutrophilic inflammation. Our findings suggest that novel therapeutic approaches using lipoxin A4 or its analogs may ameliorate inflammatory diseases in neonates.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Supported by National Institutes of Health grants HD042036, GM034310, ES004738, ES005022, HL067708, CA100994, and AR055073.

ABBREVIATIONS

- fMLP

N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine

- FPRL1

formyl peptide receptor-like 1

- Lox

lipoxygenase

- NGAL

neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- PMA

phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- PPAR-γ

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma

REFERENCES

- 1.Koenig JM, Yoder MC. Neonatal neutrophils: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Clin Perinatol. 2004;31:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Savill J, Haslett C. Granulocyte clearance by apoptosis in the resolution of inflammation. Semin Cell Biol. 1995;6:385–393. doi: 10.1016/s1043-4682(05)80009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Speer CP. New insights into the pathogenesis of pulmonary inflammation in preterm infants. Biol Neonate. 2001;79:205–209. doi: 10.1159/000047092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stefanutti G, Lister P, Smith VV, Peters MJ, Klein NJ, Pierro A, Eaton S. P-selectin expression, neutrophil infiltration, and histologic injury in neonates with necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:942–947. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.03.027. discussion 947−948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanna N, Vasquez P, Pham P, Heck DE, Laskin JD, Laskin DL, Weinberger B. Mechanisms underlying reduced apoptosis in neonatal neutrophils. Pediatr Res. 2005;57:56–62. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000147568.14392.F0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMahon B, Godson C. Lipoxins: endogenous regulators of inflammation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F189–F201. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00224.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kantarci A, Van Dyke TE. Lipoxins in chronic inflammation. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;14:4–12. doi: 10.1177/154411130301400102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bannenberg G, Moussignac RL, Gronert K, Devchand PR, Schmidt BA, Guilford WJ, Bauman JG, Subramanyam B, Perez HD, Parkinson JF, Serhan CN. Lipoxins and novel 15-epi-lipoxin analogs display potent anti-inflammatory actions after oral administration. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143:43–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Godson C, Mitchell S, Harvey K, Petasis NA, Hogg N, Brady HR. Cutting edge: lipoxins rapidly stimulate nonphlogistic phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils by monocyte-derived macrophages. J Immunol. 2000;164:1663–1667. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee TH, Horton CE, Kyan-Aung U, Haskard D, Crea AE, Spur BW. Lipoxin A4 and lipoxin B4 inhibit chemotactic responses of human neutrophils stimulated by leukotriene B4 and N-formyl-L-methionyl-L-leucyl-L-phenylalanine. Clin Sci (Lond) 1989;77:195–203. doi: 10.1042/cs0770195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Filep JG, Zouki C, Petasis NA, Hachicha M, Serhan CN. Lipoxin A4 and aspirin-triggered 15-epi-lipoxin A4 modulate adhesion molecule expression on human leukocytes in whole blood and inhibit neutrophil-endothelial cell adhesion. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;507:223–228. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0193-0_34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goh J, Godson C, Brady HR, Macmathuna P. Lipoxins: pro-resolution lipid mediators in intestinal inflammation. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1043–1054. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jozsef L, Zouki C, Petasis NA, Serhan CN, Filep JG. Lipoxin A4 and aspirin-triggered 15-epi-lipoxin A4 inhibit peroxynitrite formation, NF-kappa B and AP-1 activation, and IL-8 gene expression in human leukocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13266–13271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202296999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papayianni A, Serhan CN, Brady HR. Lipoxin A4 and B4 inhibit leukotriene-stimulated interactions of human neutrophils and endothelial cells. J Immunol. 1996;156:2264–2272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serhan CN, Levy B. Novel pathways and endogenous mediators in anti-inflammation and resolution. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2003;83:115–145. doi: 10.1159/000071558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scannell M, Maderna P. Lipoxins and annexin-1: resolution of inflammation and regulation of phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. ScientificWorldJournal. 2006;6:1555–1573. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2006.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El Kebir D, Jozsef L, Khreiss T, Pan W, Petasis NA, Serhan CN, Filep JG. Aspirin-triggered lipoxins override the apoptosis-delaying action of serum amyloid A in human neutrophils: a novel mechanism for resolution of inflammation. J Immunol. 2007;179:616–622. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrante A, Thong YH. Optimal conditions for simultaneous purification of mononuclear and polymorphonuclear leucocytes from human blood by the Hypaque-Ficoll method. J Immunol Methods. 1980;36:109–117. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(80)90036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carr R. Neutrophil production and function in newborn infants. Br J Haematol. 2000;110:18–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madyastha PR, Glassman AB, Levine DH. Incidence of neutrophil antigens on human cord neutrophils. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1984;6:124–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1984.tb00126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weinberger B, Laskin DL, Mariano TM, Sunil VR, DeCoste CJ, Heck DE, Gardner CR, Laskin JD. Mechanisms underlying reduced responsiveness of neonatal neutrophils to distinct chemoattractants. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70:969–976. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohanty JG, Jaffe JS, Schulman ES, Raible DG. A highly sensitive fluorescent micro-assay of H2O2 release from activated human leukocytes using a dihydroxyphenoxazine derivative. J Immunol Methods. 1997;202:133–141. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(96)00244-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fierro IM, Colgan SP, Bernasconi G, Petasis NA, Clish CB, Arita M, Serhan CN. Lipoxin A4 and aspirin-triggered 15-epi-lipoxin A4 inhibit human neutrophil migration: comparisons between synthetic 15 epimers in chemotaxis and transmigration with microvessel endothelial cells and epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:2688–2694. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levy BD, Clish CB, Schmidt B, Gronert K, Serhan CN. Lipid mediator class switching during acute inflammation: signals in resolution. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:612–619. doi: 10.1038/89759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bae YS, Park JC, He R, Ye RD, Kwak JY, Suh PG, Ho Ryu S. Differential signaling of formyl peptide receptor-like 1 by Trp-Lys-Tyr-Met-Val-Met-CONH2 or lipoxin A4 in human neutrophils. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:721–730. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.3.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiang N, Fierro IM, Gronert K, Serhan CN. Activation of lipoxin A(4) receptors by aspirin-triggered lipoxins and select peptides evokes ligand-specific responses in inflammation. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1197–1208. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.7.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flores AM, Li L, McHugh NG, Aneskievich BJ. Enzyme association with PPARgamma: evidence of a new role for 15-lipoxygenase type 2. Chem Biol Interact. 2005;151:121–132. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang JT, Welch JS, Ricote M, Binder CJ, Willson TM, Kelly C, Witztum JL, Funk CD, Conrad D, Glass CK. Interleukin-4-dependent production of PPAR-gamma ligands in macrophages by 12/15-lipoxygenase. Nature. 1999;400:378–382. doi: 10.1038/22572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shappell SB, Gupta RA, Manning S, Whitehead R, Boeglin WE, Schneider C, Case T, Price J, Jack GS, Wheeler TM, Matusik RJ, Brash AR, Dubois RN. 15S-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and inhibits proliferation in PC3 prostate carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:497–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chinetti G, Fruchart JC, Staels B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): nuclear receptors at the crossroads between lipid metabolism and inflammation. Inflamm Res. 2000;49:497–505. doi: 10.1007/s000110050622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gupta RA, Brockman JA, Sarraf P, Willson TM, DuBois RN. Target genes of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in colorectal cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29681–29687. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103779200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diamond P, McGinty A, Sugrue D, Brady HR, Godson C. Regulation of leukocyte trafficking by lipoxins. Clin Chem Lab Med. 1999;37:293–297. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.1999.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagner JG, Roth RA. Neutrophil migration during endotoxemia. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:10–24. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delerive P, De Bosscher K, Besnard S, Vanden Berghe W, Peters JM, Gonzalez FJ, Fruchart JC, Tedgui A, Haegeman G, Staels B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha negatively regulates the vascular inflammatory gene response by negative cross-talk with transcription factors NF-kappaB and AP-1. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32048–32054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.32048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Birrell MA, Patel HJ, McCluskie K, Wong S, Leonard T, Yacoub MH, Belvisi MG. PPAR-gamma agonists as therapy for diseases involving airway neutrophilia. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:18–23. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00098303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cuzzocrea S, Pisano B, Dugo L, Ianaro A, Maffia P, Patel NS, Di Paola R, Ialenti A, Genovese T, Chatterjee PK, Di Rosa M, Caputi AP, Thiemermann C. Rosiglitazone, a ligand of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma, reduces acute inflammation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;483:79–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kjeldsen L, Cowland JB, Borregaard N. Human neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin and homologous proteins in rat and mouse. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1482:272–283. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(00)00152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryon J, Bendickson L, Nilsen-Hamilton M. High expression in involuting reproductive tissues of uterocalin/24p3, a lipocalin and acute phase protein. Biochem J. 2002;367:271–277. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuhn H, O'Donnell VB. Inflammation and immune regulation by 12/15-lipoxygenases. Prog Lipid Res. 2006;45:334–356. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fukunaga K, Kohli P, Bonnans C, Fredenburgh LE, Levy BD. Cyclooxygenase 2 plays a pivotal role in the resolution of acute lung injury. J Immunol. 2005;174:5033–5039. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.5033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cerasoli F, Jr, Gee MH, Ishihara Y, Albertine KH, Tahamont MV, Gottlieb JE, Peters SP. Biochemical analysis of the activation of adherent neutrophils in vitro. Tissue Cell. 1988;20:505–517. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(88)90053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kantarci A, Van Dyke TE. Lipoxin signaling in neutrophils and their role in periodontal disease. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2005;73:289–299. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kantarci A, Oyaizu K, Van Dyke TE. Neutrophil-mediated tissue injury in periodontal disease pathogenesis: findings from localized aggressive periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2003;74:66–75. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]