Abstract

Previous work has shown several proteins defective in Fanconi anemia (FA) are phosphorylated in a functionally critical manner. FANCA is phosphorylated after DNA damage and localized to chromatin, but the site and significance of this phosphorylation are unknown. Mass spectrometry of FANCA revealed one phosphopeptide, phosphorylated on serine 1449. Serine 1449 phosphorylation was induced after DNA damage but not during S phase, in contrast to other posttranslational modifications of FA proteins. Furthermore, the S1449A mutant failed to completely correct a variety of FA-associated phenotypes. The DNA damage response is coordinated by phosphorylation events initiated by apical kinases ATM (ataxia telangectasia mutated) and ATR (ATM and Rad3-related), and ATR is essential for proper FA pathway function. Serine 1449 is in a consensus ATM/ATR site, phosphorylation in vivo is dependent on ATR, and ATR phosphorylated FANCA on serine 1449 in vitro. Phosphorylation of FANCA on serine 1449 is a DNA damage–specific event that is downstream of ATR and is functionally important in the FA pathway.

Introduction

Fanconi anemia (FA) is a genetic disorder characterized by a variety of congenital defects, aplastic anemia, and a susceptibility to cancer.1,2 At the cellular level, cells from patients are hypersensitive to agents that cause DNA crosslinking, including mitomycin C (MMC). Cells display increased levels of chromosomal aberrations, making FA a disease of genome instability. To respond to and repair DNA damage, replicating cells have cell-cycle checkpoints that halt cell-cycle progression when damage is detected. The S-phase checkpoint responds to stalled replication forks in dividing cells and is coordinated by ataxia telangectasia mutated (ATM) and Rad3-related (ATR) kinase, whereas the ATM kinase is activated by double-strand breaks (DSBs).3

Patients with FA have been categorized into at least 13 complementation groups (FA-A, -B, -C, -D1, -D2, -E, -F, -G, -I, -J, -L, -M, and -N), and the genes responsible for each of these have been identified (FANCA, FANCB, FANCC, FANCD1/BRCA2, FANCD2, FANCE, FANCF, FANCG, FANCJ/BRIP1, FANCL, FANCM, and FANCN/PALB2).4–8 Despite the progress made in identifying FA genes, the function of most of these proteins remains largely unknown. Several of the protein products interact in a complex termed the FA core complex. The composition of this complex changes with subcellular localization, but a nuclear form contains the FANCA, FANCB, FANCC, FANCE, FANCF, FANCG, FANCL, and FANCM proteins, together with FAAP24 and FAAP100.9–14 The integrity of the core complex is essential for FANCD2 mono-ubiquitylation after DNA damage and during S phase, at which point FANCD2 localizes to foci that correspond with proteins involved in homologous recombination, such as BRCA1 and Rad51.15,16 FANCI is also mono-ubiquitylated after damage and in S phase in a manner dependent on FANCD2 and the core complex.17 In response to DNA damage and during S phase, the core complex translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and increases in molecular weight.9 Presence in the nucleus is essential for the complex to exert its function.18 The core complex is required for FANCD2 and FANCI mono-ubiquitylation, but may have other roles not yet determined.15,17,19 FANCA, FANCG, FANCM, FANCE, FANCD2, and FANCI are phosphoproteins, underscoring the importance of phosphorylation to the FA core complex and FA pathway.12,17,20–25 Importantly, identified posttranslational modifications of FA proteins, including mono-ubiquitylation and phosphorylation, FANCD2 foci formation, and translocation of the core complex into the nucleus all occur both during undamaged S phase and in response to DNA-damaging agents such as MMC. Cells arrest in S phase after induction of interstrand crosslinks.26 Together, these observations have led to the hypothesis that activation of the FA pathway occurs during normal S phase, and DNA damage–inducibility of the FA pathway represents checkpoint function in response to replication-associated damage encountered in S phase.27

ATR kinase has been implicated in the FA pathway. ATR is activated during replication stress in response to exposed ssDNA in cells, but the exact mechanism by which it coordinates cell-cycle arrest or repair is unknown.3 ATR is essential for FANCD2 mono-ubiquitylation in response to DNA damage.28 Both ATM and ATR contribute to FANCD2 phosphorylation.23,24 Furthermore, patients with Seckel syndrome, one form of which results from ATR deficiency, are phenotypically similar to FA patients.29 FANCA is a phosphoprotein, but the kinase responsible, as well as the site of phosphorylation, have not yet been identified.21,30 FANCA phosphorylation is abrogated in FA-A mutant cells derived from patients, suggesting it is functionally important.21,31 Previous work showed that FANCA is phosphorylated on chromatin after DNA damage.9 We wished to determine whether ATR is a kinase for FANCA. The observation that phosphorylation of FANCA is sensitive to wortmannin, a PIKK inhibitor, supports a role for ATR or ATM.30

In this study, we identify a FANCA phosphorylation event and demonstrate the functional importance of this phosphorylation to the FA pathway. We provide evidence for ATR as a FANCA kinase. Importantly, we also link FANCD2 mono-ubiquitylation with FANCA phosphorylation by showing FANCD2 mono-ubiquitylation is reduced in the absence of FANCA phosphorylation. Finally, we are the first to describe the posttranslational modification of an FA protein after DNA damage but not constitutively in S phase, suggestive of a DNA damage-specific modulation of the FA pathway.

Methods

Cell culture

Cells were maintained at 37° in a 5% CO2 incubator. HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). GM 6914 FA-A mutant cells were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium plus 15% FBS. MG7 lymphoblasts were grown in RPMI + 15% FBS. Wild-type (GM02188), ATR-Seckel (DK0064), and ATM-deficient (GM01389D), generously provided by Penny Jeggo, were maintained in RPMI 1640 and 15% FBS.

Preparation of Flag-FANCA S1449A

pMMP-Flag-FANCA (S1449A) was constructed from pMMP-Flag-FANCA32 using Stratagene's QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (La Jolla, CA). The resultant plasmid was sequenced to confirm serine to alanine mutation and check for PCR-introduced mutations. GM6914 and GM6914 DR-GFP plus pMMP-vector, pMMP-FANCA, or pMMP FANCA (S1449A) were produced by retroviral transduction as previously described.21,33

Mass spectrometry

All mass spectroscopy work was performed by the Mass Spectrometry Core at the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, VA). Briefly, silver stained bands (SilverQuest; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were trypsin-digested and subjected to liquid chromatography mass spectrometry on an ion spray mass spectrometer. Spectra were analyzed and identified using the Sequest search algorithm and manually (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA).

Cell lysate and chromatin extract preparation

Whole-cell lysates were prepared by suspending cell pellets in cell lysis buffer containing 300 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 1% Triton X-100, and protease and phosphatase inhibitors (2 μg/mL aprotinin, 1 μg/mL pepstatin, 2 μg/mL leupeptin, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, and 1 mM Na3VO4). Cell suspensions were sonicated briefly and cleared by centrifugation at 15 000g (14 000 rpm) for 15 minutes. Concentration of proteins in the supernatant was determined by Bradford assay. Chromatin and cell extracts were prepared as described.34

Immunoprecipitation

To the indicated amount of protein in a volume of 1 mL was added 20 μL anti-Flag M2 agarose (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) previously washed in Tris-buffered saline (TBS). Immunoprecipitates were incubated for 1.5 hours, and beads were washed 3 times in the same cell lysis buffer and dried. Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) loading buffer was added to the dried beads.

SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting

SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) was followed by transfer onto nitrocellulose in buffer containing 25 mM Tris, 200 mM glycine, and 20% methanol. Membranes were blocked in TBS + 5% bovine serum albumin for 1 hour. Blotting was as previously described.35 Primary antibodies were diluted in TBS + 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) and incubated 3 hours to overnight. Membranes were washed 4 times in TBST, then horseradish-peroxidase linked secondary antibodies (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) were added in TBST for 1 hour. After a second wash, proteins were visualized by chemiluminescence. Antibodies used were against FANCA-N terminal32 and FANCA (ABP-6201, Cascade Bioscience, Winchester, MA), FANCD2-N terminal,20 FANCG-N terminal,34 β-tubulin (DM1B, Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), topoisomerase II (SWT3D1, Calbiochem), Ku86 (B-1, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), ATR (for immunoprecipitation, PA1-450, Affinity Bioreagents, Golden, CO), ATR (for immunoblotting, N-19, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and phospho-(Ser/Thr) ATM/ATR Substrate (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA).

Synchronization

HeLa cells were treated overnight with 2 mM thymidine, washed, released into regular media, and treated again overnight with thymidine to synchronize at the G1/S border. Cells were then released for 3 hours to obtain an S phase population and 6 hours to obtain a late S/G2 population.34

Phosphatase treatment

Phosphatase treatments were performed on whole-cell lysate. A total of 400 U of λ-phosphatase was added to 275 μg total protein in cell lysis buffer (total volume = 75 μL) and incubated for 30 minutes at 30°C; 75 μL of 2× SDS loading buffer was added to stop the reaction.

Preparation of anti-pS1449 polyclonal antiserum

The peptide C-QAAPDADLpSQEPHLF, identical to the C terminal 15 amino acids of FANCA, was conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin and used to generate a polyclonal rabbit-derived antiserum. Peptide synthesis, immunization, and serum collection were performed by Proteintech Group (Chicago, IL). Serum was affinity purified with phosphorylated peptide immobilized on a column (Aminolink; Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's instructions, eluted in 0.2 M glycine, pH 2.5, adjusted to pH 7.5 with 1 M Tris-HCl, pH 9.5, and diluted 1:1 in TBS. The resulting antibody was cross-adsorbed to an unmodified peptide column to produce antibody specific to phospho-serine 1449.

Growth inhibition assay

A total of 106 cells were plated into 75-cm2 culture flasks with growth medium containing 0, 100, 500, or 1000 nM MMC. Cells were grown until near confluence was reached in the untreated cultures (72 hours). At this time, cell numbers in each culture were determined using a hemocytometer after trypsinization. The data presented in Figure 4A represent the means of 3 independent experiments.

Figure 4.

FANCA S1449A fails to completely correct FA-associated phenotypes. (A) Results of 3 growth inhibition assays are shown for GM6914 (FA-A) cells expressing wild-type Flag-FANCA, Flag-FANCA (S1449A), or the vector control. (B) Nuclear extracts were prepared from the same cells as in panel A treated with 0.1 μM MMC for 18 hours. Extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for FANCD2. Ku86 serves as a loading control. L/S ratios were calculated using densitometric measurements of short and long band intensities. (Bottom panel) The same cells as in panel A were treated with 0.1 μM MMC for the indicated time and then lysed directly in SDS loading buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted for FANCD2 and Ku86 as a loading control. L/S ratios were calculated by densitometry and plotted against time of treatment. (C) Histogram plots are shown of chromosomal aberrations seen on metaphase spreads from GM6914 cells as in panels A and B. (D) The frequency of homologous recombination in GM6914 DR-GFP cells expressing wild-type Flag-FANCA, Flag-FANCA S1449A, or the vector control was measured using flow cytometry after HDR-mediated repair of a GFP reporter substrate. Frequency is expressed as a percentage of the level of recombination seen in wild-type FANCA-expressing cells. FANCD2-L indicates long (mono-ubiquitylated) form of FANCD2; FANCD2-S, short (nonubiquitylated) form of FANCD2; and L/S Ratio, long/short ratio.

Chromosome breakage analysis

A total of 1 μM colcemid was added to cells treated for 24 hours with 1 μM MMC. After 6 hours, cells were collected with trypsin, washed 1 time in phosphate-buffered saline, swollen in hypotonic buffer (40 mM KCl, 25 mM sodium citrate) for 20 minutes at 37°, and fixed in acetic acid/methanol (1:3) for 10 minutes. Cells were dropped onto slides and stained with Giemsa, and at least 25 metaphase spreads were analyzed for the presence of gaps, single chromatid breaks, isochromatid breaks, fragments, and polyradials.

Analysis of homologous recombination frequency

GM6914 DR-GFP cells and an I-SceI expression vector, pCBASce, were generous gifts from Dr Maria Jasin (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY). These cells have one copy of an integrated homologous recombination reporter and have been described elsewhere.36 We transduced these cells with pMMP-vector, pMMP-FANCA, and pMMP-FANCA (S1449A), selected in puromycin, and assayed for frequency of homologous recombination as described.36

In vitro kinase

ATR was immunoprecipitated from HeLa lysate in cell lysis buffer (300 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1% Triton X-100, plus protease and phosphatase inhibitors as in “Cell lysate and chromatin extract preparation”). A total of 10 mg of protein (2.5 mg/mL) was mixed with 12.5 μg anti-ATR antibody (PA1-450, Affinity Bioreagents) or 12.5 μg rabbit IgG overnight. Immunoprecipitated proteins were collected with 100 μL Protein A Sepharose (Invitrogen) for 1 hour, washed 3 times in lysis buffer, then 3 times in in vitro kinase buffer (50 mM Tris pH7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, plus protease and phosphatase inhibitors as in “Cell lysate and chromatin extract preparation”), and divided into 4 parts for 3 in vitro kinase assays and Western blot. Beads were dried, then incubated in 20 μL in vitro kinase buffer containing 1 μM cold ATP and 10 μCi [γ-32P]ATP. To this was added approximately 1 μg of GST-fusion substrate. GST-FANCA C terminus has been described.32 GST-FANCA (S1449A) was generated by PCR-mediated, site-directed mutagenesis of pGEX-FANCA(C) using QuikChange kit (Stratagene). GST fusion proteins were purified from bacteria on glutathione sepharose according to the manufacturer's instructions (GE Healthcare). In vitro kinase reactions were incubated for 1 hour at 30°C, after which 25 μL of 2× SDS loading buffer was added to stop the reaction. Resulting products were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, stained with Coomassie, then dried and detected by autoradiography.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was by analysis of variance test for significance.

Results

FANCA is phosphorylated in vivo on serine 1449

Previous work in our laboratory and others has shown that FANCA phosphorylation correlates with intact FA pathway function, and a phosphorylated form of FANCA was found on chromatin after DNA damage.9,21,37 Okadaic acid has been shown to increase the level of FANCA phosphorylation.30 Based on previous work, we hypothesized that phosphorylated FANCA would be enriched from cells doubly treated with MMC and okadaic acid. In an effort to stabilize the phosphorylation event, we treated HeLa cells stably expressing Flag-FANCA with the PP2A inhibitor, okadaic acid, and immunoprecipitated Flag-FANCA (Figure S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).38 The band containing immunoprecipitated FANCA was excised from a silver-stained gel, trypsin digested, and peptides were analyzed by mass spectrometry. FANCA peptides were identified that resulted in 62% coverage of FANCA, and only one phosphopeptide was identified, QQAAPDADLS*QEPHLF, containing phosphoserine 1449 of FANCA. Of particular note was the presence of serine 1449 within an LSQE sequence, a consensus site for the PIKK kinases ATM and ATR.39

Antiphosphoserine 1449 antiserum detects phosphorylated FANCA

To directly detect and study phosphorylation of serine 1449, we raised an antiserum against a 15-amino acid peptide centered around and containing a phosphorylated serine 1449 residue. The antiserum was affinity purified over a phosphorylated peptide column, cross-adsorbed to an unmodified peptide column, and used to detect phosphorylated FANCA. HeLa whole cell lysate from cells treated with MMC was separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for phospho-FANCA (S1449). An increase in signal was observed in cells treated with okadaic acid, consistent with the discovery of the phosphorylation event (Figure 1A lane 3). Similarly, treatment of extracts with lambda phosphatase eliminated signal detected with the antiphosphoserine 1449 antiserum, indicating the antiserum specifically detected phosphorylated FANCA (Figure 1A lane 5).

Figure 1.

Phospho-FANCA serine 1449 is induced after DNA damage. (A) HeLa cells treated with 1 μM MMC for 18 hours (lanes 2-5) and 1 μM okadaic acid for 30 minutes (lane 3) were lysed, and 175 μg protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot for endogenous FANCA. In lanes 4 and 5, 275 μg protein from HeLa cells treated with MMC was treated directly with λ-phosphatase and run on SDS-PAGE. Proteins were immunoblotted using antiphosphoserine 1449 antibody. FANCA immunoblot shows even FANCA expression. β-tubulin shows equal loading. All lanes depicted are from the same gel, same exposure. (B) HeLa cells expressing Flag-tagged FANCA, Flag-FANCA (S1449A), or vector control were treated with MMC 1 μM for 18 hours, lysed, run on SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted using the same antibodies as in panel A. (C) Cell lysates from cells in panel B were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag antibody and subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot using antiphospho-(Ser/Thr) ATM/ATR substrate antibody. IP indicates immunoprecipitation; Ppase, phosphatase; P-S1449, phosphoserine 1449; P-L(S/T)Q, phospho-leucine (serine/threonine) glutamine (ATM/ATR substrate); and MW, molecular weight marker.

FANCA is phosphorylated after treatment with MMC

Because the previously identified, phosphatase-sensitive species of FANCA was only detected after treatment with MMC, we sought to investigate whether serine 1449 was phosphorylated after DNA damage. As shown in Figure 1A lanes 1 and 2, the amount of endogenous phosphorylated FANCA increased after MMC treatment, as detected with the phospho-specific antiserum. To confirm that this phosphorylation was on serine 1449, serine 1449 was mutated to alanine (S1449A) using PCR-mediated site-directed in vitro mutagenesis. HeLa cells were infected with pMMP-Flag-FANCA wild-type or pMMP-Flag-FANCA (S1449A). Cells expressing wild-type Flag-FANCA or Flag-FANCA (S1449A) were lysed, and extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting with antiphosphoserine 1449 antibody. This antibody specifically detected an increase in the amount of phospho-FANCA after DNA damage in cells overexpressing wild-type FANCA (Figure 1B lane 4), but not in cells expressing FANCA (S1449A) (Figure 1B lane 6). In Figure 1B lanes 1 and 2, endogenous FANCA was detected on a longer exposure, as shown in Figure 1A lanes 1 and 2.

In further support of our work, Elledge reported the identification of FANCA as a substrate for ATR/ATM in a phosphoprotein screen by immunoprecipitation, using an antibody specific for substrates of ATR/ATM (S. J. Elledge, personal communication, October 2006).40 The antibody used was raised against a phospho-leucine (serine/threonine) glutamine (L(S/T)*Q) motif (Cell Signaling Technology). Based on the sequence context of S1449, this antibody would be expected to recognize phosphoserine 1449. HeLa cells expressing Flag-FANCA or Flag-FANCA (S1449A) were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag resin. The α-L(S/T)*Q antibody specifically detected immunoprecipitated wild-type FANCA only after MMC treatment (Figure 1C lane 2) and did not detect FANCA (S1449A) before or after MMC (Figure 1C lanes 3, 4), supportive of both the work from the Elledge laboratory and the DNA damage-inducibility of the phosphorylation event.

FANCA phosphorylation is induced in a time-dependent manner after MMC treatment

A time course of MMC treatment reveals that phosphorylation of FANCA increased after MMC treatment in a time-dependent manner. HeLa cells were treated for the indicated time with 1 μM MMC, lysed, and analyzed by immunoblotting (Figure 2A). Phosphorylation of FANCA was first detectable after 4 hours of MMC treatment (Figure 2A lane 2) and reached a peak level at 24 to 32 hours of MMC treatment (Figure 2A lane 6; Figure 2B lanes 4, 5). An extended time course revealed diminishing levels of phosphorylation at longer treatment times (Figure 2B).

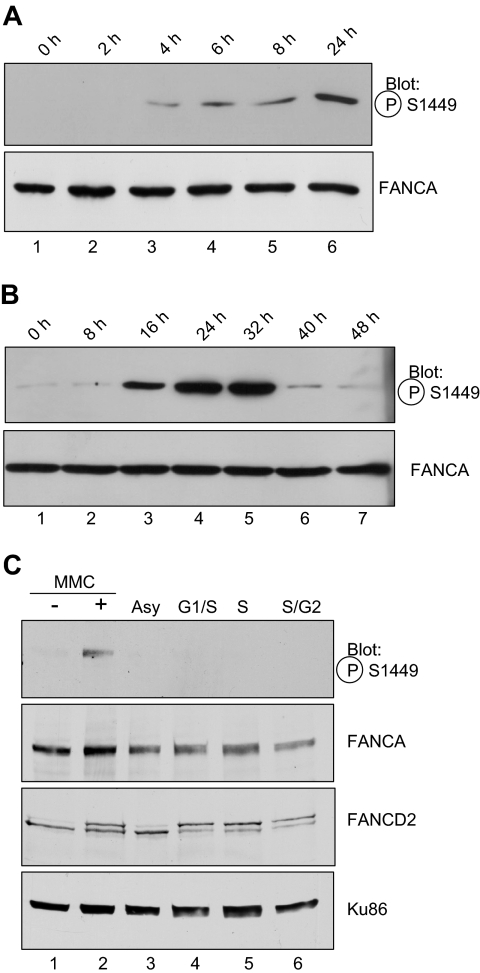

Figure 2.

FANCA is induced after MMC treatment but is not phosphorylated during S phase. (A) Exponentially growing HeLa cells were treated with 1 μM MMC for the time indicated, before preparation of whole cell lysates and SDS-PAGE electrophoresis. Western blotting was performed with the phospho-specific or nonspecific antibodies to FANCA as indicated. (B) Conditions were as in panel A, with MMC treatment continued for the indicated time. (C). HeLa cells were synchronized by double thymidine block at the G1/S border (lane 4) and released for 3 hours into S phase (lane 5) or 6 hours into late S/G2 phase (lane 6). Alternatively, cells in lane 2 were treated with 1 μM MMC for 18 hours. Whole cell extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for phosphoserine 1449, FANCA, FANCD2, and Ku86 as a loading control. P-FANCA indicates phospho-FANCA.

FANCA is not phosphorylated on serine 1449 during S phase

Other FA proteins that are modified in response to DNA damage are also modified during S phase. Specifically, FANCD2 and FANCI are mono-ubiquitylated and FANCD2 is phosphorylated after DNA damage and during S phase.15,17,24 Similarly, FANCG is phosphorylated at serine 7 after DNA damage and during S phase.20 Consequently, we sought to determine whether phosphoserine 1449 followed the same paradigm. HeLa cells were synchronized at S phase using double thymidine block or treated with MMC. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry to verify synchrony at S phase (data not shown). Surprisingly, phosphorylated FANCA could be detected after MMC treatment (Figure 2C lane 2), but not during S phase or in asynchronous extracts (Figure 2C lanes 3-5), indicating that phosphorylation of serine 1449 is specific to DNA damage by MMC. FANCD2 was mono-ubiquitylated both during the cell-cycle stages and after MMC (Figure 2C), confirming that phosphorylation of FANCA and FANCD2 mono-ubiquitylation can occur distinct from one another.

Phosphoserine 1449 FANCA is increased on chromatin after DNA damage

The original phosphorylated FANCA reported by our laboratory was found in a chromatin-associated core complex prepared from a DNA-damaged extract.9 Thus, we sought to determine whether phosphoserine 1449 FANCA was found on chromatin after DNA damage. Chromatin extracts were prepared from HeLa cells treated with MMC, and phosphorylated FANCA was detected using phospho-specific antiserum. Indeed, phosphorylated FANCA was associated almost exclusively with chromatin after MMC, whereas total FANCA was enriched on chromatin after DNA damage (Figure 3A lane 2), consistent with our previous report.34

Figure 3.

Phospho-FANCA S1449 is increased on chromatin after DNA damage and FANCA S1449A binds FANCG. (A) Chromatin extracts were prepared from HeLa cells treated with 1 μM MMC for 18 hours. Extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for phospho-FANCA S1449, total FANCA, and topoisomerase II as a loading control. (B) Whole cell extracts from HeLa cells expressing Flag-FANCA, Flag-FANCA S1449A, or the vector control and treated with 1 μM MMC for 6 hours were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag. Immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for FANCA and FANCG. topoII indicates topoisomerase II; P-S1449, phosphoserine 1449; and IP, immunoprecipitation.

FANCA S1449A is able to bind FANCG

FANCA is found within the larger FA core complex, where it forms an association with, among other proteins, FANCG. We wished to investigate whether phosphorylation on S1449 was essential for this interaction. HeLa cells expressing Flag-FANCA, Flag-FANCA S1449A, and the vector control were treated with MMC, and whole cell extracts were immunoprecipitated using anti-Flag antiserum-bound beads (Figure 3B). Importantly, FANCG was still found in association with FANCA (S1449A), indicating the core complex was at least partially intact in the absence of phosphorylation (Figure 3B lanes 3,4).

FANCA S1449A fails to fully correct FA-A mutant cells

Cells from FA patients display a marked hypersensitivity to DNA crosslinking agents, and correction of such cells with the appropriate wild-type cDNA results in complementation. If phosphorylation at serine 1449 were functionally important in the FA pathway, then mutants at S1449 would be expected to exhibit FA-associated phenotypes. To test the importance of serine 1449 phosphorylation, GM6914 FA-A mutant human fibroblasts were infected with the FANCA S1449A construct generated by site-directed mutagenesis. Cells expressing FANCA (S1449A) were assayed for sensitivity, using an MMC growth inhibition assay. FANCA (S1449A) failed to fully correct the MMC sensitivity seen in mutant FA-A cells (Figure 4A). Statistical testing using analysis of variance demonstrated the S1449A phenotype is statistically different from wild-type FANCA (P = .046) and from FA-A mutant cells (P = .018). Thus, the phosphorylation site in FANCA is functionally important for MMC resistance.

An intact FA core complex is required for FANCD2 mono-ubiquitylation after DNA damage and during S phase; therefore, FANCD2 mono-ubiquitylation is routinely used as a marker for core complex function and an intact FA pathway.15,16 FANCD2 mono-ubiquitylation was monitored in GM6914 (FA-A) cells expressing wild-type FANCA, FANCA (S1449A), and the vector control to assess the effect of the phosphorylation site mutant. Nuclear extracts were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. After MMC treatment, cells expressing wild-type FANCA showed the expected increase in the amount of mono-ubiquitylated FANCD2, whereas cells expressing FANCA (S1449A) had markedly less mono-ubiquitylated FANCD2, as confirmed by densitometry analysis and calculation of the long/short (L/S) ratio (Figure 4B top lanes 2,3). The vector control, as expected, exhibited no mono-ubiquitylated FANCD2 (Figure 4B top lane 1). Mutation of the phosphorylation site therefore reduced the efficiency of FANCD2 mono-ubiquitylation. Because mutation of serine 1449 to alanine did not result in complete loss of FANCD2 mono-ubiquitylation, we went on to clarify this defect using a time course of MMC treatment (Figure 4B bottom). In whole cell extracts from GM6914 cells expressing wild-type FANCA, an increase in mono-ubiquitylated FANCD2 was detectable at 4 hours of MMC treatment, and the level continued to increase with further treatment (Figure 4B bottom lanes 5-7). This was consistent with the time dependence of FANCA phosphorylation as shown in Figure 2A, where phosphorylation was initially detectable at 2 hours and continued to increase. In contrast, in cells expressing FANCA (S1449A), some increase in mono-ubiquitylation was detectable at 4 hours, but at later time points there is no further increase (Figure 4B bottom lanes 10-12). FANCD2 is mono-ubiquitylated constitutively at S phase; therefore, differences in FANCD2 ubiquitylation in cells expressing wild-type FANCA versus FANCA (S1449A) could potentially be explained by affected cell-cycle distribution. No differences in cell-cycle distribution were, however, detected in FA-A parental cells, those corrected by the wild-type FANCA cDNA, and those expressing the phosphomutant of FANCA (data not shown).

Cells from patients with FA have a characteristic increase in genome instability, displaying an increase in chromosomal aberrations both spontaneously and in response to DNA damage. For this reason, chromosomal breakage analysis is used as a clinical diagnostic test for FA. GM6914 fibroblasts expressing wild-type FANCA or FANCA (S1449A) and the vector control were exposed to MMC, treated with colcemid to arrest at metaphase, and metaphase spreads were prepared. Chromosomes were analyzed for the presence of gaps, single chromatid breaks, isochromatid breaks, fragments, and polyradials. Results were expressed as the number of aberrations per metaphase. At least 25 metaphases were counted per cell type. Whereas cells corrected with wild-type FANCA cDNA displayed low levels of aberrations, those expressing the phosphomutant FANCA (S1449A) exhibited an intermediate amount of chromosome aberrations compared with the vector control (Figure 4C). These data are consistent with our other findings that FANCA (S1449A) fails to fully correct the FA phenotype.

FANCA (S1449A) does not fully correct FA-A homologous recombination defect

Based on similarity of FA to other disorders of DNA repair and the interaction of FA proteins with proteins such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 known to be involved in homology directed repair (HDR), FA has been implicated in the repair of DSBs by HDR.15,41 Indeed, human cells from complementation groups FA-A, FA-G, and FA-D2 have been shown to be defective in repair of a DSB introduced on a recombination reporter.36 To assess the ability of cells expressing FANCA (S1449) to perform HDR, GM6914 (FA-A) cells were obtained (courtesy of M. Jasin, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center) with an integrated copy of the DR-GFP reporter.36 This reporter has 2 nonfunctional copies of GFP and a restriction site for the endonuclease I-SceI. A DSB is introduced by expression of I-SceI. If accurate HDR occurs, a functional GFP is produced, and HDR frequency can be calculated by the percentage of GFP-positive cells. GM6914 DR-GFP-expressing cells were infected with wild-type FANCA, FANCA (S1449A) cDNA, or the vector control and selected for stable expression. I-SceI was introduced on an expression vector, and cells were cultured for 3 days to allow time for expression of the enzyme, induction of the DSB, and repair. After this time, cells were harvested and analyzed for GFP expression using flow cytometry. GM6914 DR-GFP FANCA-corrected cells showed significantly more GFP-positive cells than the noncorrected vector control (Figure 4D; P = .027). The phosphomutant cells, GM6914 DR-GFP FANCA (S1449A), had a percentage of GFP-positive cells intermediate between the 2 and statistically distinct from wild-type FANCA (P = .043), consistent with the intermediate phenotype measured by MMC sensitivity, FANCD2 mono-ubiquitylation, and chromosome breakage. Cells transfected with an empty vector in the place of I-SceI had very low levels of GFP-positive cells (data not shown), indicating low levels of background homologous recombination on the reporter in the absence of a DSB.

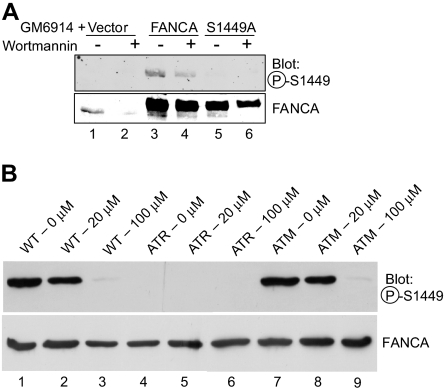

Phosphorylation of FANCA is dependent on ATR kinase

Based on the presence of serine 1449 within a consensus ATM/ATR site, as confirmed by the detection of the peptide by a screen performed by the Elledge group, and given previous work implicating ATR in FA, we hypothesized that ATR could be the kinase for FANCA at serine 1449.28,42 GM6914 FA-A mutant MMC-exposed cells expressing wild-type FANCA, FANCA (S1449A), or vector control were treated with wortmannin, a PIKK inhibitor that inhibits both ATM and ATR.43 Phosphorylation of overexpressed, wild-type FANCA decreased after wortmannin treatment (Figure 5A lane 3 vs lane 4). We then wished to investigate the phosphorylation status of FANCA in cells lacking functional ATM and ATR proteins, as previously determined for FANCG.35 ATR-Seckel (DK0064) cells failed to express a detectable level of phospho-Ser1449-FANCA (Figure 5B lanes 4-6), although it was clearly evident in both wild-type (GM02188) and ATM-deficient (GM01389D) cells (Figure 5B lanes 1-3 and 7-9). Use of a wortmannin dose that inhibits ATM (20 μM) failed to reduce the expression of phosphorylated FANCA in wild-type (Figure 5B lane 2) and ATM cells (Figure 5B lane 8), although the higher dose of 100 μM, which inhibits ATR, does result in reduced expression in these cell lines (Figure 5B lanes 3,9). These data indicate that ATM activity is not required for FANCA phosphorylation, whereas ATR activity is required.

Figure 5.

FANCA serine 1449 phosphorylation is dependent on ATR in vivo. (A) GM6914 cells expressing wild-type Flag-FANCA, Flag-FANCA (S1449A), or the vector control were treated with 0.1 μM MMC for 20 hours. At 16 hours, 1 μM wortmannin was added (lanes 2, 4, and 6) for 4 hours. Whole cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for phospho-FANCA S1449 and total FANCA. (B) Wild-type (GM02188), ATR-Seckel (DK0064), and ATM-deficient (GM01389D) cell lines were treated with 50 nM MMC and the indicated dose of wortmannin for 18 hours before preparation of lysates. Western blotting was performed with the phosphospecific or nonspecific antibodies to FANCA. P-S1449 indicates phosphoserine 1449.

ATR kinase phosphorylates S1449 in vitro

Given the role of ATR in vivo, we wished to investigate whether serine 1449 in FANCA was a substrate for ATR in vitro. Endogenous ATR kinase was immunoprecipitated from HeLa cells (Figure 6B) and incubated with GST alone, a GST-FANCA C terminal fusion protein (amino acids 1250-1455) encompassing serine 1449, or GST-FANCA (S1449A) C terminal fusion in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP and in vitro kinase conditions. All substrates were expressed and purified (Figure 6A, Coomassie), but ATR was only able to phosphorylate the GST-FANCA wild-type C terminal fusion, as detected by autoradiography (Figure 6A autorad lane 2, *). The phosphorylation was eliminated in the S1449A mutant (Figure 6A autorad lane 3). This, together with the consensus site at serine 1449 for ATR or ATM, is suggestive that ATR is a kinase for FANCA on serine 1449 in vitro but does not eliminate the possibility that the activity may be from an associated immunoprecipitated kinase. Taken together with the in vivo studies, these data indicate that ATR is responsible either directly or indirectly for phosphorylation of FANCA. To rule out the likelihood that the downstream effector of ATR, CHK1, could be phosphorylating FANCA, we conducted a blot of HeLa cells exposed or not to MMC in the presence or absence of CHK1 inhibitor SB218078. As seen in Figure 6C, unlike wortmannin, the CHK1 inhibitor SB28078 failed to abrogate FANCA phosphorylation.

Figure 6.

ATR phosphorylates serine 1449 of FANCA in vitro. ATR kinase was purified from HeLa cells by immunoprecipitation using anti-ATR antibody. After immunoprecipitation, beads were divided for Western blot (B) and in vitro kinase assay (A). (A) Immunoprecipitated ATR (lanes 1-3) or a control IgG immunoprecipitation (lanes 4-6) was incubated with GST (lanes 1,4), GST-FANCA C terminus (lanes 2,5), or GST-FANCA S1449A C terminus (lanes 3,6) in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. Products were separated by SDS-PAGE, stained with Coomassie, and dried, and resulting labeled substrates were detected by autoradiography. (B) Western blot for ATR showing immunoprecipitation of ATR with anti-ATR antibody (lane 3) but not with a control IgG immunoprecipitation (lane 2). (C) Chk1 inhibition does not inhibit phospho-FANCA S1449. HeLa cells were treated for 18 hours with 1 mM MMC (lanes 2-4). Cells in lanes 3 and 4 were additionally treated with 1 μM SB218078 or 100 μM wortmannin, respectively. Whole cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for phospho-FANCA S1449, total FANCA, and β-actin as a loading control. (D) In vitro kinase reaction was run as in panel A, except aliquots were incubated in the presence of wortmannin. Wortmannin inhibited ATR phosphorylation of the wild-type fusion protein. C term indicates C terminus; and IP, immunoprecipitation.

Discussion

With the exception of FANCL, a ubiquitin ligase, the helicase FANCJ/BRIP1, and FANCM/Hef, which contains a DNA binding motif, the functions of the other FA proteins remain elusive, partially because of their lack of functional motifs.11,12,44,45 Understanding the regulation and binding partners of the Fanconi proteins, including FANCA, can provide insight into the function of the proteins and the role of the FA pathway in genome stability. We report a phosphorylation of FANCA on serine 1449 that is DNA damage–inducible and essential to the function of the FA pathway. Importantly, we show this phosphorylation is dependent on ATR kinase. This, together with data showing that mono-ubiquitylation and phosphorylation of FANCD2 are dependent on ATR, places the FA pathway within the broader context of the DNA damage repair pathway and provides insight into the way in which ATR exerts its genome-maintenance role.24,42

We report here that phosphorylated FANCA is found on chromatin after DNA damage (Figure 3). Similarly, mono-ubiquitylated FANCD2 is found on chromatin after DNA damage, but mono-ubiquitylation is reduced in cells mutant at serine 1449. ATR kinase phosphorylates its binding partner, ATR interacting protein (ATRIP), and subsequently relocates to chromatin after DNA damage.46 FANCA (S1449A), however, localizes normally to chromatin (Figure S2). An interesting question is whether FANCA is phosphorylated before or on arriving on chromatin. Although we have demonstrated that FANCA phosphorylation is dependent on ATR, it remains a possibility that ATR may not be the direct kinase for FANCA in vivo or in vitro. ATR phosphorylates downstream effectors and adaptors that could possibly be responsible for the direct phosphorylation.47 We have investigated one downstream kinase, CHK1. In the presence of a specific inhibitor of CHK1, SB218078, FANCA is phosphorylated normally on S1449 after MMC treatment (Figure 6C), indicating that CHK1 is not required for FANCA phosphorylation.48 The presence of serine 1449 within an ATR/ATM consensus site, together with the data presented here and that provided by Elledge's group, is highly suggestive of a direct role for ATR.40

Importantly, we report the first differentiation of the FA pathway after DNA damage and during S phase. Until now, it has been understood that the function of the FA pathway in the DNA damage response was similar to its normal physiologic function at S phase. In support of this is evidence that FANCD2 and FANCI are mono-ubiquitylated and FANCG is phosphorylated both at S phase and after DNA damage.16,17,20 The core complex was also known to localize to chromatin under both conditions.49 This is the first report of an event in the pathway to occur specifically after DNA damage. This may represent a DNA damage-specific mechanism of activating the common FA pathway, or it may represent a mechanism by which a specialized function of the FA proteins is activated. Cells expressing FANCA (S1449A) will be useful reagents to dissect these possibilities and uncover potentially novel functions for the FA proteins. Separation of function seen after DNA damage versus S phase represents an important observation in FA biology.

How the phosphorylation modulates FANCD2 mono-ubiquitylation is unknown. Speculative mechanisms could include modulating the stability of FANCD2 itself or the stability of FANCD2 mono-ubiquitylation after MMC treatment, perhaps by negatively regulating the deubiquitylase, USP1, after DNA damage in a way that is not required at S phase.50 Consistent with this, we observe a slight but consistent decrease in FANCD2 expression after MMC treatment in cells expressing FANCA (S1449A) (Figure 4B top lane 3 and bottom lanes 11,12).

Cells mutant at serine 1449 of FANCA have an intermediate FA phenotype rather than a complete loss of function phenotype as measured by MMC sensitivity, FANCD2 mono-ubiquitylation, chromosome breakage, and homologous recombination. This partial correction of phenotype by a phosphorylation mutant is consistent with previous reports for several other FA proteins.20,22,24,25,35 PD20 (FA-D2) cells expressing T691A and S717A mutants of FANCD2 exhibit intermediate MMC sensitivity and partial restoration of radioresistant DNA synthesis,24 T346A and S374A mutants of FANCE result in incomplete restoration of MMC resistance,25 whereas S7A, S383A, and S387A mutants of FANCG confer an intermediate phenotype in both human and hamster cell lines.20,22 For FANCD2, these phosphorylations promote mono-ubiquitylation,24 whereas phosphorylation of Ser7 of FANCG promotes formation of a BRCA2-D2-G-XRCC3 protein complex.35 The reason for the partial complementation by S1449A FANCA is not yet clear, but it may be postulated that phosphorylation is necessary only for responding to increased cellular stress on the induction of DNA damage, rather than in normal cell activities such as maintaining replication during S phase in the presence of endogenous lesions or low levels of induced DNA damage. As presented in Figure 3B, FANCA (S1449A) is able to associate with FANCG and may retain partial function by forming associations with other proteins of the FA pathway. Thus, the S1449A protein may be able to operate normally during S-phase in undamaged cells but cannot be activated in response to DNA damage because of loss of a specialized function associated only with phosphorylated FANCA. The partial correction of the FA phenotype with the S1449A mutant and the specificity of FANCA phosphorylation on DNA damage strongly support this notion. Nevertheless, these data implicate S1449 as being necessary for complete correction of a variety of FA phenotypes, including cellular resistance to MMC, efficient FANCD2 mono-ubiquitylation, chromosomal stability after MMC, and repair of DSB by homologous recombination (Figure 4).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Maria Jasin and Penny Jeggo for sharing cell lines, Steven Elledge for sharing unpublished data, and Jennifer Phillips for technical assistance.

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Bethesda, MD) grant R01-063776 (G.M.K.) and North West Cancer Research Fund (Liverpool, United Kingdom) grant CR751 (N.J.J.).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: N.B.C. designed and performed research, collected data, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; T.B., A.T., J.B.W., and K.J.R. performed research and collected data; and N.J.J. and G.M.K. designed the research, analyzed and interpreted data, and assisted in writing the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Gary M. Kupfer, LMP 2074, 333 Cedar Street, New Haven, CT 06520; e-mail: gary.kupfer@yale.edu.

References

- 1.Alter BP. Cancer in Fanconi anemia, 1927-2001. Cancer. 2003;97:425–440. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kutler DI, Singh B, Satagopan J, et al. A 20-year perspective on the International Fanconi Anemia Registry (IFAR). Blood. 2003;101:1249–1256. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGowan CH, Russell P. The DNA damage response: sensing and signaling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:629–633. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taniguchi T, D'Andrea AD. Molecular pathogenesis of Fanconi anemia: recent progress. Blood. 2006;107:4223–4233. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins N, Kupfer GM. Molecular pathogenesis of Fanconi anemia. Int J Hematol. 2005;82:176–183. doi: 10.1532/IJH97.05108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joenje H, Patel KJ. The emerging genetic and molecular basis of Fanconi anaemia. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:446–457. doi: 10.1038/35076590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reid S, Schindler D, Hanenberg H, et al. Biallelic mutations in PALB2 cause Fanconi anemia subtype FA-N and predispose to childhood cancer. Nat Genet. 2007;39:162–164. doi: 10.1038/ng1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xia B, Dorsman JC, Ameziane N, et al. Fanconi anemia is associated with a defect in the BRCA2 partner PALB2. Nat Genet. 2007;39:159–161. doi: 10.1038/ng1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomashevski A, High AA, Drozd M, et al. The Fanconi anemia core complex forms four complexes of different sizes in different subcellular compartments. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:26201–26209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400091200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meetei AR, Levitus M, Xue Y, et al. X-linked inheritance of Fanconi anemia complementation group B. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1219–1224. doi: 10.1038/ng1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meetei AR, de Winter JP, Medhurst AL, et al. A novel ubiquitin ligase is deficient in Fanconi anemia. Nat Genet. 2003;35:165–170. doi: 10.1038/ng1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meetei AR, Medhurst AL, Ling C, et al. A human ortholog of archaeal DNA repair protein Hef is defective in Fanconi anemia complementation group M. Nat Genet. 2005;37:958–963. doi: 10.1038/ng1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ciccia A, Ling C, Coulthard R, et al. Identification of FAAP24, a Fanconi anemia core complex protein that interacts with FANCM. Mol Cell. 2007;25:331–343. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ling C, Ishiai M, Ali AM, et al. FAAP100 is essential for activation of the Fanconi anemia-associated DNA damage response pathway. EMBO J. 2007;26:2104–2114. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia-Higuera I, Taniguchi T, Ganesan S, et al. Interaction of the Fanconi anemia proteins and BRCA1 in a common pathway. Mol Cell. 2001;7:249–262. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taniguchi T, Garcia-Higuera I, Andreassen PR, Gregory RC, Grompe M, D'Andrea AD. S-phase-specific interaction of the Fanconi anemia protein, FANCD2, with BRCA1 and RAD51. Blood. 2002;100:2414–2420. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smogorzewska A, Matsuoka S, Vinciguerra P, et al. Identification of the FANCI protein, a mono-ubiquitinated FANCD2 paralog required for DNA repair. Cell. 2007;129:289–301. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naf D, Kupfer GM, Suliman A, Lambert K, D'Andrea AD. Functional activity of the fanconi anemia protein FAA requires FAC binding and nuclear localization. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5952–5960. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.5952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsushita N, Kitao H, Ishiai M, et al. A FancD2-mono-ubiquitin fusion reveals hidden functions of Fanconi anemia core complex in DNA repair. Mol Cell. 2005;19:841–847. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qiao F, Mi J, Wilson JB, et al. Phosphorylation of fanconi anemia complementation group G protein, FANCG, at serine 7 is important for function of the FA pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:46035–46045. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408323200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kupfer G, Naf D, Garcia-Higuera I, et al. A patient-derived mutant form of the Fanconi anemia protein, FANCA, is defective in nuclear accumulation. Exp Hematol. 1999;27:587–593. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(99)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mi J, Qiao F, Wilson JB, et al. FANCG is phosphorylated at serines 383 and 387 during mitosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8576–8585. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.19.8576-8585.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taniguchi T, Garcia-Higuera I, Xu B, et al. Convergence of the fanconi anemia and ataxia telangiectasia signaling pathways. Cell. 2002;109:459–472. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00747-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho GP, Margossian S, Taniguchi T, D'Andrea AD. Phosphorylation of FANCD2 on two novel sites is required for mitomycin C resistance. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:7005–7015. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02018-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang X, Kennedy R, Ray K, Stuckert P, Ellenberger T, D'Andrea AD. Chk1-mediated phosphorylation of FANCE is required for the Fanconi anemia/BRCA pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;12:12. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02357-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akkari YM, Bateman RL, Reifsteck CA, Olson SB, Grompe M. DNA replication is required To elicit cellular responses to psoralen-induced DNA interstrand cross-links. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8283–8289. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.21.8283-8289.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang X, D'Andrea AD. The interplay of Fanconi anemia proteins in the DNA damage response. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:1063–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andreassen PR, D'Andrea AD, Taniguchi T. ATR couples FANCD2 mono-ubiquitination to the DNA-damage response. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1958–1963. doi: 10.1101/gad.1196104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Driscoll M, Ruiz-Perez VL, Woods CG, Jeggo PA, Goodship JA. A splicing mutation affecting expression of ataxia-telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein (ATR) results in Seckel syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003;33:497–501. doi: 10.1038/ng1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yagasaki H, Adachi D, Oda T, et al. A cytoplasmic serine protein kinase binds and may regulate the Fanconi anemia protein FANCA. Blood. 2001;98:3650–3657. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.13.3650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adachi D, Oda T, Yagasaki H, et al. Heterogeneous activation of the Fanconi anemia pathway by patient-derived FANCA mutants. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:3125–3134. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.25.3125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kupfer GM, Naf D, Suliman A, Pulsipher M, D'Andrea AD. The Fanconi anaemia proteins, FAA and FAC, interact to form a nuclear complex. Nat Genet. 1997;17:487–490. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ory DS, Neugeboren BA, Mulligan RC. A stable human-derived packaging cell line for production of high titer retrovirus/vesicular stomatitis virus G pseudotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:11400–11406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qiao F, Moss A, Kupfer GM. Fanconi anemia proteins localize to chromatin and the nuclear matrix in a DNA damage- and cell cycle-regulated manner. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:23391–23396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101855200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson JB, Yamamoto K, Marriott AS, et al. FANCG promotes formation of a newly identified protein complex containing BRCA2, FANCD2 and XRCC3. Oncogene. 2008;27:3641–3652. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1211034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakanishi K, Yang YG, Pierce AJ, et al. Human Fanconi anemia mono-ubiquitination pathway promotes homologous DNA repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1110–1115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407796102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamashita T, Kupfer GM, Naf D, et al. The fanconi anemia pathway requires FAA phosphorylation and FAA/FAC nuclear accumulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13085–13090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schonthal AH. Role of PP2A in intracellular signal transduction pathways. Front Biosci. 1998;3:D1262–D1273. doi: 10.2741/A361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Neill T, Dwyer AJ, Ziv Y, et al. Utilization of oriented peptide libraries to identify substrate motifs selected by ATM. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:22719–22727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001002200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsuoka S, Ballif BA, Smogorzewska A, et al. ATM and ATR substrate analysis reveals extensive protein networks responsive to DNA damage. Science. 2007;316:1160–1166. doi: 10.1126/science.1140321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Howlett NG, Taniguchi T, Olson S, et al. Biallelic inactivation of BRCA2 in Fanconi anemia. Science. 2002;297:606–609. doi: 10.1126/science.1073834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pichierri P, Rosselli F. The DNA crosslink-induced S-phase checkpoint depends on ATR-CHK1 and ATR-NBS1-FANCD2 pathways. EMBO J. 2004;23:1178–1187. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sarkaria JN, Tibbetts RS, Busby EC, Kennedy AP, Hill DE, Abraham RT. Inhibition of phosphoinositide 3-kinase related kinases by the radiosensitizing agent wortmannin. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4375–4382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levitus M, Waisfisz Q, Godthelp BC, et al. The DNA helicase BRIP1 is defective in Fanconi anemia complementation group J. Nat Genet. 2005;37:934–935. doi: 10.1038/ng1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Litman R, Peng M, Jin Z, et al. BACH1 is critical for homologous recombination and appears to be the Fanconi anemia gene product FANCJ. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:255–265. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Itakura E, Umeda K, Sekoguchi E, Takata H, Ohsumi M, Matsuura A. ATR-dependent phosphorylation of ATRIP in response to genotoxic stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;323:1197–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.08.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou BB, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: putting checkpoints in perspective. Nature. 2000;408:433–439. doi: 10.1038/35044005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jackson JR, Gilmartin A, Imburgia C, Winkler JD, Marshall LA, Roshak A. An indolocarbazole inhibitor of human checkpoint kinase (Chk1) abrogates cell cycle arrest caused by DNA damage. Cancer Res. 2000;60:566–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mi J, Kupfer GM. The Fanconi anemia core complex associates with chromatin during S phase. Blood. 2005;105:759–766. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nijman SM, Huang TT, Dirac AM, et al. The deubiquitinating enzyme USP1 regulates the Fanconi anemia pathway. Mol Cell. 2005;17:331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.