Abstract

Background

“Referral” characterises a significant area of interaction between primary and secondary care. Despite advantages, it can be inflexible, and may lead to duplication.

Objective

To examine the outcomes of an integrated model that lends weight to general practitioner (GP)‐led evidence based care.

Design

A prospective, non‐random comparison of two services: women attending the new (Bridges) pathway compared with those attending a consultant‐led one‐stop menstrual clinic (OSMC). Patients' views were examined using patient career diaries, health and clinical outcomes, and resource utilisation. Follow‐up was for 8 months.

Setting

A large teaching hospital and general practices within one primary care trust (PCT).

Results

Between March 2002 and June 2004, 99 women in the Bridges pathway were compared with 94 women referred to the OSMC by GPs from non‐participating PCTs. The patient career diary demonstrated a significant improvement in the Bridges group for patient information, fitting in at the point of arrangements made for the patient to attend hospital (ease of access) (p<0.001), choice of doctor (p = 0.020), waiting time for an appointment (p<0.001), and less “limbo” (patient experience of non‐coordination between primary and secondary care) (p<0.001). At 8 months there were no significant differences between the two groups in surgical and medical treatment rates or in the use of GP clinic appointments. Significantly fewer (traditional) hospital outpatient appointments were made in the Bridges group than in the OSMC group (p<0.001).

Conclusion

A general practice‐led model of integrated care can significantly reduce outpatient attendance while improving patient experience, and maintaining the quality of care.

Keywords: primary–secondary care interface, menorrhagia, one‐stop clinic, delivery of health care

In the UK, patients are registered with a general practitioner (GP), who is their primary care provider. With few exceptions, it is the GP who determines patients' access to hospital and specialist care in the secondary sector. Upon request by the GP, patients are seen for a consultation in hospital outpatient clinics before further management is planned. Patient transfer between primary and secondary care usually involves a “referral”, which reassigns some responsibility for care. While determinants of referral both from and to primary care are complex and difficult to quantify, rates of referral vary widely.1,2,3,4 Given that attendance at hospital outpatient departments can be associated with subsequent elective admission, referral decisions in primary care have an important impact on resource use.2 It would therefore seem to be advantageous if such referrals were to be determined by evidence based criteria and pathways.

Use of the GP as a “gatekeeper” to hospitals has helped to contain healthcare costs. Despite this, existing services struggle to cope with increasing demand and to meet government targets. A further problem with “referral” based patient transition is that it can be inflexible, for apart from assigning different degrees of urgency it may be unable to respond to differing requirements of the referral—for example, investigation and diagnosis, advice and reassurance or treatment.5 A more responsive approach is advocated in the NHS plan (2000), which argued that care should be designed around the patient, that unnecessary stages of care should be removed, and that there should be a standard guideline or protocol for each condition.6 The NHS Confederation has supported this view, and proposed the development of new working relationships at the primary–secondary interface with the aim of reducing the estimated 30–70% of outpatient work that is not materially adding to patient care.7

Optimising care therefore requires consideration of both primary and secondary sectors and of patients' transition between the two. Exploring new ways of interacting with secondary care is also important in the context of the evolution of general practitioners with a special interest and the role of general practice in commissioning services.8 We adopted an integrated care model9 and assessed its impact on patient care.

We developed an integrated, evidence based care pathway for women with menstrual disorders (Bridges pathway; table 1) to facilitate their access to diagnostic and therapeutic facilities within secondary care, eliminating the need for a traditional “referral”, and set out to assess its impact. The Bridges pathway involved the use of shared evidence based guidelines for the management of patients in both primary and secondary care, which determined timing for investigations and surgical treatment. Management decisions (including booking for investigations or surgery) were made by GPs in all but atypical or complex cases. The latter were the only category receiving consultations in secondary care.

Table 1 Main distinguishing features between the two care pathways.

| Features | Bridges | OSMC |

|---|---|---|

| Use of guidelines | Agreed joint guidelines between primary and secondary care | Secondary care |

| Access to investigations in secondary care | Open at request of GP | Only through referral, determined after consultation |

| Consultation in secondary care | Only for complex cases | For all referrals |

| Surgical treatment | Decided and booked by GP according to guidelines | Decided and booked by hospital consultant |

| Same day investigations | Yes | Yes |

OSMC, one‐stop menstrual clinic.

We adapted the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) guidelines for the management of menorrhagia into an integrated care record (ICR).10,11 The record was paper based but also provided in electronic form for easy archiving by equipped practices. The ICR was used to record the history and examination findings in checklist form, and was used for direct booking of services in secondary care. Using the ICR, the GP could (a) manage uncomplicated cases in primary care; (b) book and receive investigation results—for example, ultrasound, hysteroscopy and biopsy, where indicated, while continuing to manage the patient; (c) book patients for surgical treatment—for example, endometrial ablation or hysterectomy; (d) request an outpatient consultation for complex or atypical cases. Booking for hospital investigations or treatments was done by the GP practice or directly by patients. Results were communicated to patients and GPs the following day by phone and fax, respectively.

The partner organisations were the South Leicestershire Primary Care Trust consisting of 21 practices and 89 GPs providing primary care to a mixed urban, semi‐rural and rural population of around 150 000 people, and the one‐stop menstrual clinic (OSMC) at the University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust. The clinic provides same day service for consultation, investigation, results (including histopathology) and initiation of treatment.12

Methods

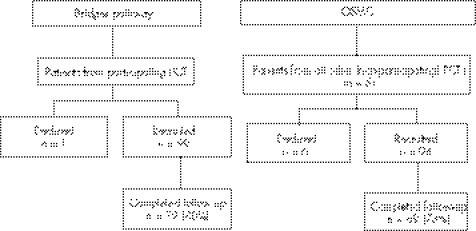

A prospective observational study was undertaken over 28 months to evaluate the new service. Between March 2002 and June 2004, the outcomes of women consecutively presenting to the new service “ Bridges project” were compared with patients referred by GPs in non‐participating PCTs to the OSMC (established service) (fig 1). The five non‐participating PCTs comprised 519 GPs in 136 practices. All patients were given verbal and written information about the study and provided written consent. Follow‐up was for 8 months after first attendance in secondary care.

Figure 1 Flow diagram of study.

We hypothesised that the new pathway would result in improved patient experience as measured using the patient career diary (PCD) as a primary outcome.13 We used the sections of the diary relevant to the patients' journey. Health status was investigated at baseline and at 8 months using the SF‐36 version 2,14,15 in conjunction with the multiattribute scale for menorrhagia (MQ).16 We recorded medical and surgical treatment rates, and use of other services such as hospital and primary care attendances and investigations.

Statistical analysis and sample size

Using patient career diaries, assuming a mean score of 80 for the patients treated using the OSMC,12 and an SD of 18 in each group, we calculated that 81 patients would be needed for each group to detect a clinically important change in score of 10% with 80% power and p<0.05. We aimed at recruiting 100 patients for each group to allow for dropouts. Results were summarised as means (SD) or as frequencies, as appropriate. Student's t test, χ2 test or Fisher's exact test, and Mann–Whitney test were used for comparative statistics. 95% Confidence intervals were calculated for the main study results. Statistical significance was defined at the 5% level throughout. All analyses were carried out using SPSS version 11. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated for the PCD total section scores to assess whether allowance for “clustering” of patients for individual GPs was needed. The ICC values ranged from 0.09 to 0.27, indicating a low level of clustering for an average of two patients for each GP, so that the study analysis could use conventional methods. For confirmation of this, the main study comparisons were given a secondary analysis making explicit allowance for the clustering of patients within GP lists, using the “robust” variance estimation method within the STATA computer package (StataCorp 2003. Stata Statistical Software: Release 8.0. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation).

Results

All GPs from the 21 practices in the South Leicester PCT were approached and asked to participate, but two (10%) practices declined representing 8/89 (9%) GPs. Overall, 28 GPs from 14 practices actively used the Bridges pathway (representing 32% of GPs in the PCT and 67% of practices). The control group consisted of women referred by 68 GPs from the five non‐participating PCTs in Leicestershire. All patients attending the Bridges pathway and the OSMC groups were asked if they would participate in the study. Of those approached, seven declined; no reason was given in three cases, one person moved to the private sector, two cited lack of time because of work or family, and one was moving home. Thus, 99 women in the Bridges and 94 women in the OSMC groups were recruited. Seventy‐nine women (80%) in the Bridges group and 69 (73%) in the OSMC group completed 8 months follow‐up. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups for age, height, weight, parity, previous miscarriages, smoking habits, employment status, smoking habits or haemoglobin concentration; and no statistically significant differences between the number of women in the two groups with cycle regularity, presence or absence of dysmenorrhoea or heavy bleeding (results not shown), or in symptom severity scores (table 2) at study entry.

Table 2 Menstrual questionnaire score for the two groups at entry and after 8 months of follow‐up.

| Usable response rate, n (%) | Mean score | Difference | 95% CI | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bridges (n = 99) | OSMC (n = 94) | Bridges | OSMC | ||||

| Entry menstrual questionnaire score (MQ1) | 93 (94) | 86 (91) | 49.96 | 44.23 | 5.73 | −1.30 to 12.77 | 0.110 |

| Exit menstrual questionnaire (MQ2)* | 69 (70) | 55 (59) | 60.93 | 57.48 | 3.45 | −5.56 to 12.46 | 0.450 |

| Change in score (MQ2 – MQ1) by participant | 67 (68) | 52 (55) | 9.22 | 8.01 | 1.21 | −6.00 to 8.41 | 0.741 |

OSMC, one‐stop menstrual clinic.

* Only women still menstruating were eligible to complete the exit menstrual questionnaire.

The PCD (table 3) demonstrated significant improvements in the Bridges group compared with the OSMC at point of arrangements made for the patient to attend hospital. This denoted improved information provision and fitting in, choice of doctor, waiting for appointment and less limbo (denoting poor experiences of care, feelings of uncertainty and powerlessness). The score for the whole section was higher in the Bridges (72.9) compared with the OSMC (67.4) groups (p = 0.007). The score for overall health care as measured at the end of 8 months demonstrated no significant differences between the two groups (table 3). The results of the “robust” t tests with allowance for patient clustering (not presented in this paper) agreed closely with those derived using the conventional t test and presented above.

Table 3 Patient career diary score (PCD) for women with menstrual disorders attending the Bridges project compared with those attending the one‐stop menstrual clinic (OSMC).

| Sections and components of the PCD | Usable responses, n (%) | Mean Score | Difference | 95% CI | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bridges (n = 99) | OSMC (n = 94) | Bridges | OSMC | ||||

| When the GP told you that you needed to go to the OPD | 91 (92) | 89 (95) | |||||

| Score for whole section | 69 (70) | 77 (82) | 69.18 | 64.19 | 4.99 | −0.88 to 10.82 | 0.095 |

| Component 1: information, fitting in with arrangements* | 83 (84) | 84 (89) | 74.40 | 63.31 | 11.09 | 5.48 to 16.70 | <0.001 |

| Component 2: getting in, appointments† | 86 (87) | 86 (91) | 69.99 | 64.17 | 5.82 | −0.96 to 12.59 | 0.092 |

| Component 3: continuity | 74 (75) | 79 (84) | 63.06 | 65.40 | −2.34 | −11.04 to 6.37 | 0.596 |

| Going to your first outpatient or specialist clinic visit | 88 (89) | 82 (87) | |||||

| Score for whole section | 56 (57) | 61 (65) | 72.90 | 67.43 | 5.47 | 1.56 to 9.38 | 0.007 |

| Component 1: information, fitting in with arrangements | 73 (74) | 72 (77) | 73.46 | 73.48 | −0.02 | −4.89 to 4.84 | 0.993 |

| Component 2: continuity, choice of doctor‡ | 65 (66) | 68 (72) | 59.74 | 56.37 | 3.37 | 0.53 to 6.21 | 0.020 |

| Component 3: wait for appointment | 83 (84) | 75 (80) | 80.22 | 58.33 | 21.89 | 16.7 to 27.07 | <0.001 |

| Component 4: clinic organisation | 84 (85) | 79 (84) | 79.91 | 78.16 | 1.75 | −2.34 to 5.84 | 0.400 |

| Component 5: limbo | 84 (85) | 79 (84) | 67.86 | 54.96 | 12.90 | 7.31 to 18.49 | <0.001 |

| Your health care overall | 80 (81) | 67 (71) | |||||

| Score for whole section | 64 (65) | 58 (62) | 68.84 | 63.22 | 5.62 | −0.59 to 11.82 | 0.075 |

| Component 1: coordination, progress | 72 (73) | 64 (68) | 70.23 | 67.38 | 2.85 | −4.49 to 10.17 | 0.444 |

| Component 2: continuity, limbo | 70 (71) | 62 (66) | 52.14 | 50.08 | 2.06 | −2.55 to 6.68 | 0.378 |

OPD, outpatients department.

* The extent to which healthcare settings and staff attitudes are organised around the needs of patients.

† Gaining access to appropriate care at all stages, including across interfaces.

‡ Analysis affected by high proportion of patients who answered “not applicable” to questions 10, 11, and 12 of component 2.

SF‐36 scores showed a modest change over the follow‐up period, but there were no statistically significant differences between the groups apart from the role‐emotional score (reflecting ability to carry out work or other daily activities as a result of emotional problems), which showed a significant improvement (p = 0.012) from 40.8 to 49.5 in the OSMC compared with the Bridges group (results not shown). At the end of the follow‐up period, the menstrual questionnaire score showed no significant differences between the two groups (table 2).

No structural pathology was found in 59 (60%) of the Bridges group and 61 (65%) of the OSMC group. Two patients in the Bridges group were found to have endometrial cancer, and two women in the OSMC group were found to have endometrial hyperplasia on pipelle biopsy but both proved to have endometrial cancer on hysterectomy. Of those who responded at the end of the 8 months' follow‐up (table 4), there were no significant differences between the two groups in the number of women not receiving treatment, those receiving medical treatment, and those who had undergone or were awaiting surgery (p = 0.789).

Table 4 Medical and surgical treatment(s) received after attending the Bridges and the one‐stop menstrual clinic (OSMC).

| All participants, n (%) | Responders to follow‐up, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bridges (n = 99) | OSMC (n = 94) | Bridges (n = 79) | OSMC (n = 69) | |

| Not receiving any treatment at 8 months | – | – | 45 (57) | 36 (52) |

| Receiving medical treatment at 8 months | – | – | 18 (23) | 16 (23) |

| Tried one medical treatment during study | – | – | 54 (68) | 50 (72) |

| Tried second line medical treatment during study | – | – | 23 (29) | 27 (39) |

| Tried third line medical treatment during study | – | – | 6 (8) | 7 (10) |

| Surgical treatment | 12 (12) | 16 (17) | 11 (14)* | 11 (16) |

| Hysteroscopic laser polypectomy | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 3 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Endometrial ablation | 1 (1) | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Abdominal hysterectomy | 8 (8) | 12 (13) | 7 (9) | 10 (14) |

| Awaiting surgical treatment | 5 (5) | 9 (10) | 5 (6) | 6 (9) |

| Hysteroscopic laser polypectomy | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Endometrial ablation | 0 (0) | 4 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Total abdominal hysterectomy | 4 (4) | 3 (3) | 4 (5) | 3 (4) |

| Vaginal hysterectomy | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

–, not applicable.

* Including one patient with failed laser ablation of the endometrium awaiting hysterectomy.

By the end of the 8 months follow‐up, the Bridges group (n = 79) had made 142 visits to the GP (1.8 visits/patient), whereas the OSMC patients (n = 69) had made 144 visits (2.1 visits/patient) (table 5). There were significantly fewer hospital outpatient consultations in the Bridges group than in the OSMC group (p<0.001) (table 6).

Table 5 Number of women attending for consultations in primary care in the year before and the 8 months after hospital attendance.

| Before attending hospital, n (%) | p Value | After attending hospital, n (%) | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bridges (n = 79) | OSMC (n = 69) | Bridges (n = 79) | OSMC (n = 69) | |||

| Number of visits to GP | ||||||

| 1 | 26 (33) | 16 (23) | 29 (37) | 10 (14) | ||

| 2 | 24 (30) | 22 (32) | 38 (48) | 46 (67) | ||

| 3 | 11 (14) | 14 (20) | 0.313 | 7 (9) | 8 (12) | 0.018 |

| 4 | 7 (9) | 6 (9) | 1 (1) | 3 (4) | ||

| 5 | 4 (5) | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| 6 | 6 (8) | 6 (9) | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | ||

| Missing data | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | ||

| Total number of visits | 191 | 177 | 142 | 144 | ||

| Past use of hospital clinics* | ||||||

| 0 | 77 | 65 | ||||

| 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.339 | |||

| Missing data | 1 | 1 | ||||

OSMC, one‐stop menstrual clinic.

*Number of attendances at outpatients in the year before the index attendance.

Table 6 Number and type of hospital attendances during the follow‐up period.

| Hospital visit | Bridges, n (%) (n = 99) | OSMC, n (%) (n = 94) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial visit to outpatients | |||

| Consultation | 23 (23) | 94 (100) | <0.001 |

| Ultrasound scan | 70 (71) | 73 (78) | 0.270 |

| Hysteroscopy and biopsy | 94 (95) | 82 (87) | 0.059 |

| Subsequent visits to outpatients | |||

| No follow‐up | 85 (86) | 66 (70) | 0.006 |

| One follow‐up consultation | 13 (13) | 20 (21) | |

| Two follow‐up consultations | 1 (1) | 8 (9) | |

| Operative pre‐assessment visit to outpatients | 9 (9) | 9 (10) | 0.908 |

OSMC, one‐stop menstrual clinic.

Discussion

Strengths and limitations

Our study involved a new approach to healthcare delivery and a significant role change for both primary and secondary care. Our results are significant as we compared the Bridges model with a one‐stop clinic which was associated with considerable improvement compared with the traditional clinic.12 Possibly, a randomised controlled trial would have yielded more robust conclusions, but this would not have been feasible in the current structures in primary care without a considerable risk of contamination. Although this model has the potential to be applied to areas other than menstrual problems, it is not possible to extrapolate directly from our findings to other areas, and there is a need for further research with different patient groups and disease conditions.

Main findings

Patients' experiences must remain central to service provision. The PCD is a tool designed to assess patients' journeys through the healthcare system. The OSMC provides a highly organised, consultant‐delivered service, yet we demonstrated further improvement in patients' experiences through the Bridges model of care, where the GP is the principal care provider and decision maker. Several aspects of the Bridges pathway scored better. This appears to reflect the fact that the Bridges pathway allows patients better control of their journey and more purposeful visits to healthcare providers, both in primary and secondary care. Menstrual problems on the whole tend to be dealt with by female GPs within practices and this may be a factor in the total number of GPs represented. That patients preferred the Bridges model when it came to the type of doctor may be a reflection on the observation that patients attending primary care with menstrual problems often exercise some choice over the doctor they see. The model also enhanced the patients' sense that progress is being made. Although the results from the PCD suggest that the impact of the new pathway may blunt over time, this is not surprising and is consistent with our observation in the OSMC compared with the traditional gynaecology clinic.12

Health status (SF‐36) and menstrual status questionnaires demonstrated that both pathways produce comparable health outcomes. We remain uncertain of the clinical significance of the more favourable role‐emotional score for patients attending the OSMC. Surgical and medical intervention rates for the GP led service were comparable to the consultant‐led evidence based service as applied in the one‐stop clinic.

One of the most significant findings in our study was that initial fears that the Bridges pathway might result in an increased workload in primary care did not materialise. On the contrary, we demonstrated that the integrated approach reduced workload both in primary and secondary care. Given that health outcomes were comparable, we assume that such saving resulted from a reduction of duplication and non‐value adding work.

Interpretation in the context of current services

Previous attempts have been made to influence the pattern of “referral” between primary and secondary care, with variable results. In East Anglia, an educational package delivered to GPs was shown to positively influence their referral rate and prescribing patterns.17,18 Reorganisation in secondary care, coupled with evidence based guidelines adopted in primary care, was shown to result in more rapid management decisions.19 On the other hand, dissemination of infertility guidelines to practices in Glasgow coupled with educational meetings resulted in only a modest change in the rate of investigations carried out before referral, with no detectable differences in outcomes or costs.20 Published research accepts referral as a means of communication between healthcare sectors. It attempts to improve care by improving adherence to guidelines and subsequently influencing referral. In the case of menstrual problems, this system is supported by the two‐phase RCOG guidelines for use in primary and secondary care.10,11 Referral, however, is influenced by a range of complex factors beyond the dissemination of knowledge, guidelines and education. Our approach was different in that we aimed at promoting patient progress while removing the traditional boundaries between the care sectors. Evidence based practice was used to underpin care, allowing primary care management more scope for arranging investigations and treatments traditionally reserved for secondary care. This approach allowed freeing of resources while reducing duplication. An interesting observation is that women referred to the OSMC continued to use GP services at the same rate as those who were not referred to the clinic, suggesting that multiplicity of providers may increase resource use with no clear benefit. This requires further evaluation.

Implications for the future of service delivery

It is important that services evolve to embrace changing patient expectations and to respond to the national agenda. Patients are increasingly better informed about treatment options, allowing them greater control. Centralisation allows hospitals to concentrate resources towards more complex interventions, and there is an increasing need for services to be provided in community settings.21 Practice based commissioning and payment by results will change the dynamics between primary and secondary care and changes in referral patterns consequent to these initiatives should be evidence based and able to demonstrate advantage.22,23 An important feature of the Bridges pathway is its ability to deliver clinical care that is booked, communicated and delivered in such a manner as to minimise disruption to patients. The project aimed at achieving improvement through an integrated network of provision, and by tackling the rigid barriers between the main sectors.21 Within UK health policy the Bridges pathways embraces the evolving and widening role of the GP.24

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the Trent‐NHS R&D. The views expressed are those of the authors, and the sponsor had no influence over the execution of the research, collating the results or data analysis.

Abbreviations

GP - general practitioner

ICC - intraclass correlation coefficient

ICR - integrated care record

OSMC - one‐stop menstrual clinic

PCD - patient career diary

RCOG - Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None.

References

- 1.Reynolds G A, Chitnis J G, Roland M O. General practitioners outpatient referral – do good doctors refer more patients to hospital? BMJ 19913021250–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coulter A, Seagroatt V, McPherson K. Relation between general practices outpatient referral rates and elective admission to hospital. BMJ 1990301273–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coulter A, Peto V, Doll H. Influence of sex of general practitioner on management of menorrhagia. Br J Gen Pract 199545471–475. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waghorn A, McKee M, Thompson J. Surgical outpatients: challenges and responses. Br J Surg 199784300–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coulter A, Noone A, Goldacre M. General practitioners referrals to specialist outpatient clinics. BMJ 1988299304–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Health The NHS plan: a plan for investment, a plan for reform. London: DH, 2000

- 7.Edwards N, Austin J.Modernising outpatients – developing effective services. London: The NHS Confederation, 2001

- 8.Department of Health Practitioners with special interests: bringing services closer to patients. London: DH, 2003

- 9.Campbell H, Hotchkiss R, Bradshaw N.et al Integrated care pathways. BMJ 1989316133–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists The initial management of menorrhagia. London: RCOG Press, 1998, (Evidence‐based clinical guideline No1. )

- 11.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists The management of menorrhagia in secondary care. London: RCOG Press, 1999, (Evidence‐based clinical guideline No 5. )

- 12.Abu J I, Habiba M A, Baker R.et al Quantitative and qualitative assessment of women's experience of a one‐stop menstrual clinic in comparison with traditional gynaecology clinics. BJOG 2001108993–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker R, Preston C, Cheater F.et al Measuring patients' attitudes to care across the primary/secondary interface: the development of the patient career diary. Qual Health Care 19998154–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jenkinson C, Stewart‐Brown S, Petersen S.et al Assessment of the SF‐36 version 2 in the United Kingdom. J Epidemiol Community Health 19995346–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garratt A M, Ruta D A, Abdalla M I.et al SF 36 health survey questionnaire: II. Responsiveness to changes in health status in four common clinical conditions. Qual Health Care 19943186–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaw R W, Brickley M R, Evans L.et al Perceptions of women on the impact of menorrhagia on their health using multi‐attribute utility assessment. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 19981051155–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fender G R K, Prentice A, Gorst T.et al Randomized controlled trial of educational package on management of menorrhagia in primary care: the Anglia menorrhagia education study. BMJ 19993181246–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fender G R, Prentice A, Nixon R M.et al Management of menorrhagia: an audit of practices in the Anglia menorrhagia education study. BMJ 2001322523–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas R E, Grimshaw J M, Mollison J.et al Cluster randomized trial of a guideline‐based open access urological investigation service. Fam Pract 200320646–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrison J, Carroll L, Twaddle S.et al Pragmatic randomised controlled trial to evaluate guidelines for the management of infertility across the primary care‐secondary care interface. BMJ 20013221282–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Department of Health Creating a patient led NHS, delivering the NHS improvement plan. London: DH, 2005

- 22.Department of Health Practice based commissioning; engaging practices in commissioning. London: DH, 2004

- 23.Department of Health Reforming NHS financial flows: introducing payment by results. London: DH, 2002

- 24.Department of Health, Royal College of General Practitioners Implementing a scheme for general practitioners with special interests. London: DH, 2002