Abstract

Ischemic injury is traditionally viewed from an axiomatic perspective of neuronal loss. Yet the ischemic infarct encompasses all cell types, including astrocytes. This review will discuss the idea that astrocytes play a fundamental role in the pathogenesis of ischemic neuronal death. It is proposed that stroke injury is primarily a consequence of the failure of astrocytes to support the essential metabolic needs of neurons. This ‘gliocentric view’ of stroke injury predicts that pharmacological interventions specifically targeting neurons are unlikely to succeed, because it is not feasible to preserve neuronal viability in an environment that fails to meet essential metabolic requirements. Neuroprotective efforts targeting the functional integrity of astrocytes may constitute a superior strategy for future neuroprotection.

Introduction

Over the past decade, a virtual revolution has occurred in our understanding of the physiology of astrocytes, and of their interactions with neurons in the normal brain 1, 2. For example, astrocytes actively propagate Ca2+ signals to neighboring neurons, whose level of synaptic activity they can actively modulate 3, 4. Key mediators of astrocyte-neuron signaling are glutamate 5 and ATP/adenosine 6. While much current work is focused on the role of gliotransmitters in synaptic transmission, the potential harmful effects of glutamate/ATP release from astrocytes in the ischemic penumbra has not been defined. Also, astrocytes have recently been implicated in the local control of blood flow 7-9, but it is not established how ischemia affects the ability of astrocytes to modulate vascular tone. We will here critically evaluate astrocytes as a potential new therapeutic target in stroke. Although the contribution of astrocytes to the process of ischemic infarction has not been clearly defined, an abundance of data already suggests the importance of astrocytes in both the initiation and propagation of secondary ischemic injury.

Pathology of focal stroke

Focal ischemia, or prolonged occlusion of a cerebral vessel, initiates the process of ischemic infarction, in which all tissue elements are affected. Ischemic infarcts are sharply demarcated and the transition between the infarct and the surrounding tissue is frequently less than 100 μm. All cell types, including neurons, astrocytes, and the vasculature are dead in a chronic infarct, whereas cells in the per-infarct areas are preserved. No evidence for neuronal loss outside chronic infarcts has been identified in either human or rodent brain 10, 11. In contrast, transient artery occlusion is frequently associated with selective neuronal injury with little, if any loss of astrocytes 12. Functional recovery after prolonged or permanent artery occlusion is often poor, indicating that ischemic infarcts have a much worse prognosis than transient ischemic attacks (TIA) associated with selective neuronal injury.

Supportive functions of astrocytes

Astrocytes are the principal housekeeping cells of the nervous system. Their main supportive tasks are to scavenge transmitters released during synaptic activity, control ion and water homeostasis, release neurotrophic factors, shuttle metabolite and waste products, and to participate in the formation of the blood-brain-barrier 13. Failure of any of these supportive functions of astrocytes will, either alone or in combination, constitute a threat for neuronal survival. In fact, the all-and-none pattern of ischemic infarction indicates that neurons are not capable of surviving in the absence of astrocytes. Unfortunately, our current understanding of how ischemia affects basic astrocytic functions is incomplete 14. It has not been established to which degree astrocytic glutamate uptake is impaired in the ischemic penumbra. It is therefore not possible to predict whether impairment of astrocytic glutamate uptake contributes more significantly to neuronal death, than for example a decrease in astrocytic K+ buffering capacity.

Astrocytes Ca2+ oscillations and Ca2+ waves

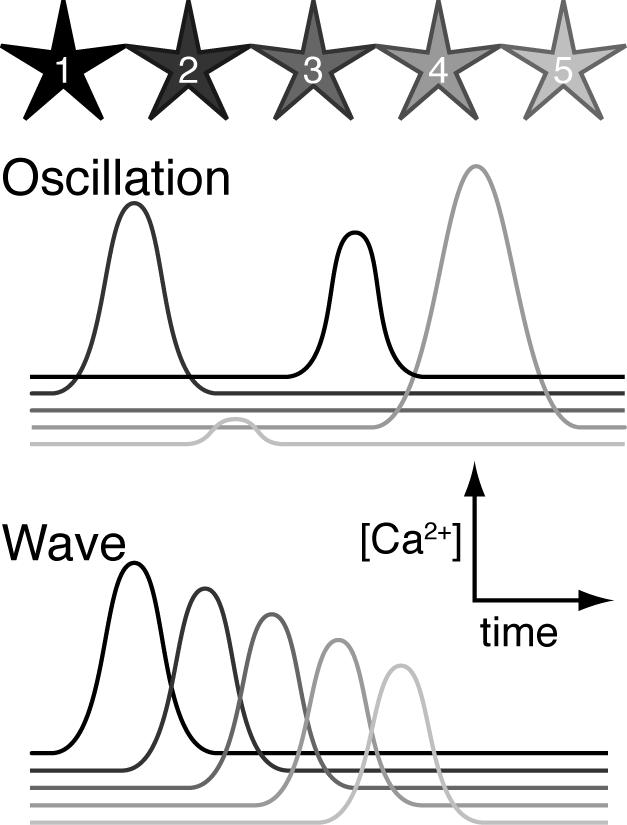

A growing body of evidence has in the last decade documented that astrocytes are more than the supportive cells of CNS. Astrocytes express neurotransmitter receptors and respond to neuronal activity by increases in cytosolic Ca2+ 15. Astrocytes display two distinct types of Ca2+ signaling modalities: Ca2+ oscillations and propagating Ca2+ waves 16. Ca2+ oscillations are repetitive monophasic increases in cytosolic Ca2+ limited to a single cell. Ca2+ oscillations can be evoked by exposure to several different transmitters, including glutamate, GABA, and ATP 17. They can also be triggered by removal of extracellular Ca2+, or by exposure of cultured astrocytes to hypoosmotic solutions 18. An extensive literature has documented that astrocytic Ca2+ oscillations involves activation of PLA, IP3 production, and release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores, rather than Ca2+ influx through membrane channels 17.

The second modality of astrocytic Ca2+ signaling, propagating Ca2+ waves, can be stimulated by focal electrical stimulation, mechanical stimulation, lowering extracellular Ca2+ levels, or by local application of transmitters (glutamate or ATP). High frequency neuronal spiking has been shown to induce astrocytic Ca2+ waves in organotypic slices and in anesthetized mice following sensory stimulation 19, 20. In general, Ca2+ waves propagate with a velocity of around 8−20 μm/s and expand over a maximum radius of 100 to 300 μM, including 10 to 50 astrocytes per wave. Initially, it was proposed that propagation of Ca2+ waves was conducted through the diffusion of IP3 and/or calcium through intercellular gap junctions 21. Using pharmacologic approaches, it was demonstrated that an extracellular agent, ATP, was the actual diffusible messenger 22. Similar studies have in parallel shown that ATP mediates Ca2+ waves in several non-excitable cells, including epithelium, liver, heart, and osteoblasts (see Berridge 2000 48). Wave propagation is mediated by P2Y receptors, likely including multiple purinergic receptor subtypes in astrocytes, including P2Y1, P2Y2, and P2Y4 23. Ca2+ waves can be viewed as a pathway for amplification of astrocytic activation. When an astrocyte reaches a certain level of activation, it will release ATP that in turn increases Ca2+ in its neighbors resulting in a spatial expansion of astrocytic activation 49. Purinergic signaling plays important roles in coordination and synchronization of astrocytic responses to synaptic transmission. Accordingly, inhibition of astrocytic P2Y receptors reduced and delayed Ca2+ increases in cortical astrocytes following whisker stimulation 20. Little is known with regard to the effect of ischemia on purinergic signaling. However, traumatic spinal cord injury is associated with prolonged increases in astrocytic ATP release. Motor neurons express multiple purinergic receptors, including P2×7 receptors. Administration of P2×7 receptor antagonists reduces tissue injury and improves functional recovery suggesting that excessive purinergic signaling contributes to secondary damage following spinal cord injury 24.

Mechanisms of ATP release

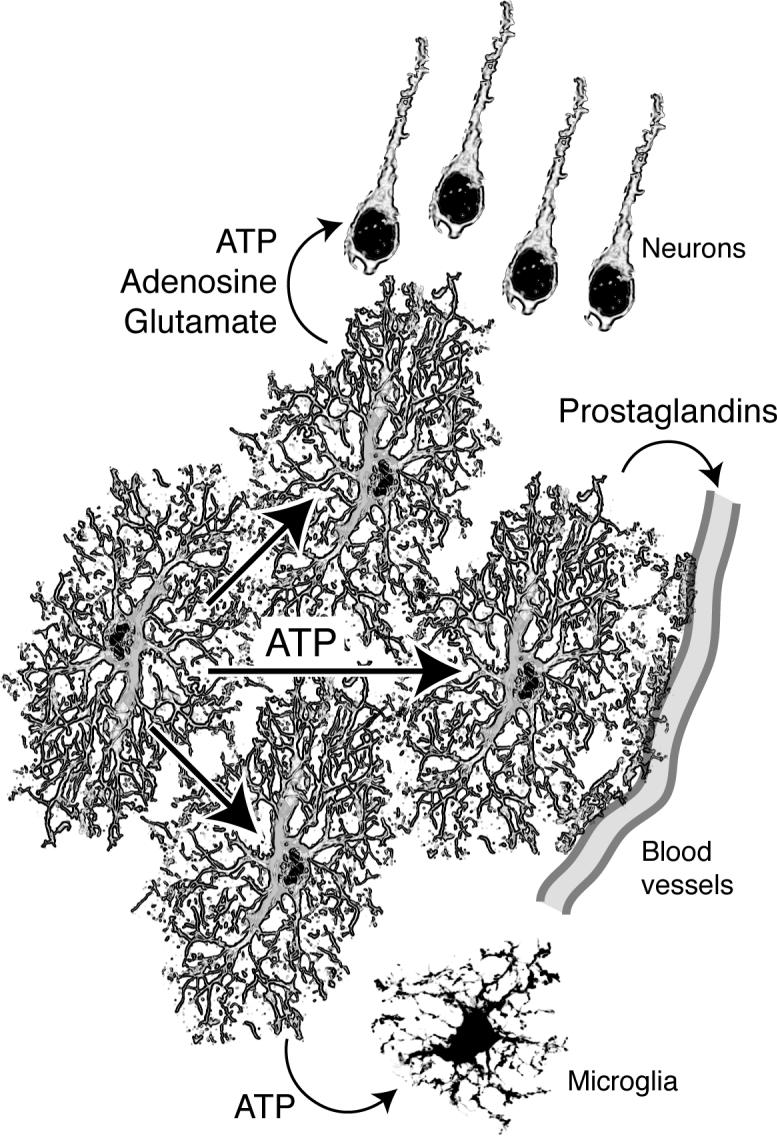

Purinergic signaling represents the most important pathway by which astrocytes communicate with other cells in CNS. A key step to understand the modulation of astrocytic function is therefore to define the mechanism by which these electrically unexcitable cells release ATP. Several pathways of ATP release have been proposed, including channel-mediated release, exocytosis of ATP containing vesicles, connexin (C×) hemichannels, and P2×7 receptor hemichannels, possibly linked to pannexins (reviewed in 25. Several observations indicate that C×-hemichannels are the most significant mechanism of ATP release from astrocytes. It has been shown that: C×-deficient glia cell lines increased ATP release 3 to 10-fold after transfection with C×43 22; C×-channel blockers (NPPB and FFA) potently inhibited ATP release 26; and single channel recordings indicate that ATP can exit through C×43 hemichannels 27. Cultured neurons do not release ATP in response to K+ or receptor activation, suggesting that release of ATP from synaptic vesicles is low 28. Although neurons express the gap junction protein, C×36 29., this connexin has a small single channel conductance and is impermeable to larger molecules, including Lucifer yellow and ATP 30. Astrocytes can release many other transmitters, including PGE2, glutamate, TNF-α, and d-serine, which play a role in paracrine signaling between astrocytes and neurons, endothelial cells, and microglial cells. The pathways for release of these gliotransmitters have not been established. Nevertheless, excessive release of gliotransmitters in the setting of ischemia is likely contributing to additional cellular damage, similar to the observations of increased ATP release in spinal cord inury.

Astrocytic Ca2+ signaling as an integral part of brain function

Purinergic signaling represents the primary pathway for astrocyte-astrocyte signaling. Emerging evidence indicates that astrocytes also modulate the function of other cell types in brain by release of ATP and other gliotransmitters including glutamate, PGE2, and d-serine. Several methods by which astrocytes modulate brain function are described here:

Synaptic transmission

A flurry of studies has over the past few years documented that astrocytes can modulate neuronal Ca2+ levels and synaptic transmission by means of Ca2+ signaling. For example, spontaneous astrocytic Ca2+ oscillations and subsequent glutamate release can drive NMDA-receptor-mediated neuronal excitation in the rat ventrobasal thalamus 31, and astrocytes can potentiate inhibitory transmission in the hippocampus through a pathway that is sensitive to kainate-receptor antagonists 32. These and other studies have pointed to glutamate and ATP/adenosine as key mediators of astrocyte-to-neuron signaling 33. Astrocytic release of ATP leads to the production of adenosine in the extracellular space by the action of highly expressed nucleotidases that degrade ATP with a rapid time constant (∼200 ms) 34. Adenosine then acts as is a potent neurotransmitter, with pervasive and generally inhibitory effects on neuronal activity 34. Several recent lines of work have demonstrated that astrocytes can control network activity in both cortex and hippocampus through adenosine resulting from astrocytic ATP release 28, 35. Adenosine has both presynaptic and postsynaptic effects. Presynaptically, adenosine A1 receptors inhibited Ca2+ channel opening resulting in reduced transmitter release, whereas postsynaptically, A1 receptors opened K+ channels resulting in hyperpolarization and decreased neuronal activity 34. In a resting state, low levels of extracellular adenosine tonically dampened neural activity, and the A1 receptor antagonist, DPCPX, increased spontaneous cortical activity. Conversely, adenosine or the A1 specific agonist CCPA potently suppressed local activity 34. Interestingly, adenosine and ATP have recently been implicated in the depression of synaptic activity associated with increased concentrations of CO2 36, and one report found that extracellular ATP was increased in rat striatum following MCA occlusion 37.

Control of local microcirculation

Given that cerebral microvessels are extensively ensheathed by astrocyte processes, thereby physically linking the intraparenchymal vasculature with synapses, it is tempting to speculate that astrocytes are involved in activity-induced hyperemia 38, 39. Several studies suggest that astrocytes participate in activity-dependent parenchymal blood flow regulation. One study demonstrated that astrocytic activity can influence vascular tone, by observing that direct stimulation of perivascular astrocytes in cortical slices caused vasodilation 7. It was demonstrated that mGluRs on astrocytes were activated by synaptic release of glutamate and that the resultant astrocytic Ca2+ signaling was linked to changes in vascular diameter. This study concluded that a cyclooxygenase product was involved, since acetylsalicylic acid blocked astrocyte-mediated vasodilation 7. A subsequent study, which selectively targeted astrocytes by Ca2+ photolysis, found that astrocytic Ca2+ signaling triggered cerebrovascular constriction 40. Similar to the first report, arachodonic acid (AA) metabolites were generated in astrocytes, but were proposed to diffuse into smooth muscle cells, where they are converted to 20-HETE, a potent vasoconstrictor 40. The two papers raised considerable interest and it was speculated that use of L-NAME or differences with regard to brain regions (cortex versus hippocampus) could explain the opposing results. Importantly, both studies were performed in non-blood perfused brain slices, which has obvious limitations when studying functional hyperemia. Using 2-photon imaging of intact cortex in live adult mice, it was later demonstrated that photolysis of caged Ca2+ in astrocytic endfeet invariably triggered vasodilation 8. Astrocytic activation lead to an 18% increase in arterial cross-sectional area corresponding to an almost 40% increase in local perfusion. A specific COX-1 inhibitor (NS-398), as well as indomethacin, attenuated astrocyte-induced vasodilation. Furthermore, COX-1 immunoreactivity was strongly expressed around penetrating cortical arteries, suggesting that COX-1 vasoactive products mediated vasodilation 8. Recent work has supported the concept that COX-1 is the primary mediator of vasodilation involving astrocytes 41.

Microglial cell activation

Recent reports using 2-photon imaging have shown that astrocytes release ATP in response to local injury, this, in turn, activated local microglial cells 42, 43. Microglial P2Y12 and P2Y6 receptors are critical for movement and phagocytosis, respectively 44, 45. Together, these reports highlight the importance of astrocytic ATP release and position purinergic signaling in as an important initial step of inflammatory responses.

Human astrocytes are more are larger, more complex, and more diverse than rodent astrocytes

The relative ratio of glial cells to neurons increases algorithmically with phylogeny, manifestly as a function of increasingly complex information processing 6. The human brain also contains subtypes of GFAP positive astrocytes that are both human and primate specific, suggesting their importance in the evolution of the human brain 46 . Additionally, human protoplasmic astrocytes are significantly larger in diameter and more complex that the rodent counterpart represented by a 2.5 fold increase in diameter and 10-fold more main GFAP positive processes. Human protoplasmic astrocytes are organized into domains in which there is little overlap adjacent cells processes, resulting in autonomous territories of neuropil that are influenced by a single astrocyte. The domain of a single human astrocyte has been estimated to contain up 2 million synapses as well as vasculature, significantly greater than the estimated 20,000 to 120,000 synapses in rodent astrocytic domains 46. Therefore, human astrocytes can integrate a larger contiguous set of synapses in conjunction with the vasculature creating a larger glioneuronal unit linking neuronal activity with blood flow. Therefore, in adult humans then, stroke may be more a disease of astrocytes than in our experimental rodent models.

CONCLUSION

During evolution, neurons have lost many essential metabolic pathways as they became increasingly specialized and gained the ability to generate action potentials and communicate by synaptic transmission. As a consequence, neurons in the adult brain depend on metabolic support from surrounding astrocytes. For example, neurons do not express the mitochondrial enzyme glutamine dehydrogenase and cannot produce the chief excitatory transmitter, glutamate, which in the adult CNS mediates 70% of neurotransmission. Since glutamate does not pass through the blood-brain-barrier, excitatory transmission heavily depends on glutamate produced by astrocytes 33. Similarly, synapse formation requires multiple lipids, including cholesterol, produced by astrocytes 47. It is clear that neuron survival in both the normal and the diseased brain relies heavily on surrounding astrocytes. A striking example is ischemic infarcts, in which neurons do not survive if neighboring astrocytes are lost. While large gaps exist with regard to our understanding of how ischemia affects the supportive function of astrocytes, it is likely that failure of glutamate uptake, K+ buffering, water homeostasis, vascular control, etc, all contribute to the massive loss of neurons in focal stroke. A challenge for the future is to develop experimental tools to manipulate and monitor dynamic changes in the supportive function in ischemic astrocytes.

Fig. 1.

Ca2+ oscillations and Ca2+ waves represent two different modalities of astrocytic Ca2+ signaling

Fig. 2.

ATP is the main transmitter by which astrocytes communicate with neighboring astrocytes. ATP is also an important paracrine transmitter in signaling to neurons, vessels, and microglial cells. Other gliotransmitters include glutamate, d-serine, and prostaglandins,

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants, NS38073, NS39559, and NS050315 and the Adelson Program in Neural Repair and Regeneration.

References

- 1.Haydon PG. Glia: Listening and talking to the synapse. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:185–193. doi: 10.1038/35058528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Volterra A, Meldolesi J. Astrocytes, from brain glue to communication elements: The revolution continues. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:626–640. doi: 10.1038/nrn1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nedergaard M. Direct signaling from astrocytes to neurons in cultures of mammalian brain cells. Science. 1994;263:1768–1771. doi: 10.1126/science.8134839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parpura V, Basarsky TA, Liu F, Jeftinija K, Jeftinija S, Haydon PG. Glutamate-mediated astrocyte-neuron signalling. Nature. 1994;369:744–747. doi: 10.1038/369744a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Araque A, Parpura V, Sanzgiri RP, Haydon PG. Tripartite synapses: Glia, the unacknowledged partner. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:208–215. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01349-6. 205_00001349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nedergaard M, Ransom B, Goldman SA. New roles for astrocytes: Redefining the functional architecture of the brain. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:523–530. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zonta M, Angulo MC, Gobbo S, Rosengarten B, Hossmann KA, Pozzan T, Carmignoto G. Neuron-to-astrocyte signaling is central to the dynamic control of brain microcirculation. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:43–50. doi: 10.1038/nn980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takano T, Tian GF, Peng W, Lou N, Libionka W, Han X, Nedergaard M. Astrocyte-mediated control of cerebral blood flow. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:260–267. doi: 10.1038/nn1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iadecola C, Nedergaard M. Glial regulation of the cerebral microvasculature. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1369–1376. doi: 10.1038/nn2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nedergaard M, Astrup J, Klinken L. Cell density and cortex thickness in the border zone surrounding old infarcts in the human brain. Stroke. 1984;15:1033–1039. doi: 10.1161/01.str.15.6.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nedergaard M. Neuronal injury in the infarct border: A neuropathological study in the rat. Acta Neuropathol. 1987;73:267–274. doi: 10.1007/BF00686621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nedergaard M. Mechanisms of brain damage in focal cerebral ischemia. Acta Neurol Scand. 1988;77:81–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1988.tb05878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y, Swanson RA. Astrocytes and brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:137–149. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000044631.80210.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nedergaard M, Dirnagl U. Role of glial cells in cerebral ischemia. Glia. 2005;50:281–286. doi: 10.1002/glia.20205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verkhratsky A, Orkand RK, Kettenmann H. Glial calcium: Homeostasis and signaling function. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:99–141. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cotrina M, Nedergaard M. Intracellular calcium control mechanisms in glia. Oxford University Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Roderick HL. Calcium signalling: Dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:517–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stout C, Charles A. Modulation of intercellular calcium signaling in astrocytes by extracellular calcium and magnesium. Glia. 2003;43:265–273. doi: 10.1002/glia.10257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dani JW, Chernjavsky A, Smith SJ. Neuronal activity triggers calcium waves in hippocampal astrocyte networks. Neuron. 1992;8:429–440. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90271-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X, Lou N, Xu Q, Tian GF, Peng WG, Han X, Kang J, Takano T, Nedergaard M. Astrocytic ca(2+) signaling evoked by sensory stimulation in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:816–823. doi: 10.1038/nn1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charles AC, Merrill JE, Dirksen ER, Sanderson MJ. Intercellular signaling in glial cells: Calcium waves and oscillations in response to mechanical stimulation and glutamate. Neuron. 1991;6:983–992. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90238-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cotrina ML, Lin JH, Alves-Rodrigues A, Liu S, Li J, Azmi-Ghadimi H, Kang J, Naus CC, Nedergaard M. Connexins regulate calcium signaling by controlling atp release. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15735–15740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cotrina ML, Lin JH, Lopez-Garcia JC, Naus CC, Nedergaard M. Atp-mediated glia signaling. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2835–2844. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-08-02835.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang X, Arcuino G, Takano T, Lin J, Peng WG, Wan P, Li P, Xu Q, Liu QS, Goldman SA, Nedergaard M. P2x7 receptor inhibition improves recovery after spinal cord injury. Nat Med. 2004;10:821–827. doi: 10.1038/nm1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haydon PG, Carmignoto G. Astrocyte control of synaptic transmission and neurovascular coupling. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:1009–1031. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00049.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stout CE, Costantin JL, Naus CC, Charles AC. Intercellular calcium signaling in astrocytes via atp release through connexin hemichannels. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10482–10488. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109902200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang J, Kang N, Lovatt D, Torres A, Zhao Z, Lin J, Nedergaard M. Connexin 43 hemichannels are permeable to atp. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4702–4711. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5048-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang JM, Wang HK, Ye CQ, Ge W, Chen Y, Jiang ZL, Wu CP, Poo MM, Duan S. Atp released by astrocytes mediates glutamatergic activity-dependent heterosynaptic suppression. Neuron. 2003;40:971–982. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00717-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Connors BW, Long MA. Electrical synapses in the mammalian brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:393–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teubner B, Degen J, Sohl G, Guldenagel M, Bukauskas FF, Trexler EB, Verselis VK, De Zeeuw CI, Lee CG, Kozak CA, Petrasch-Parwez E, Dermietzel R, Willecke K. Functional expression of the murine connexin 36 gene coding for a neuron-specific gap junctional protein. J Membr Biol. 2000;176:249–262. doi: 10.1007/s00232001094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parri HR, Gould TM, Crunelli V. Spontaneous astrocytic ca2+ oscillations in situ drive nmdar-mediated neuronal excitation. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:803–812. doi: 10.1038/90507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang J, Jiang L, Goldman S, Nedergaard M. Astrocyte-mediated potentiation of inhibitory synaptic transmission. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:683–692. doi: 10.1038/3684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nedergaard M, Takano T, Hansen AJ. Beyond the role of glutamate as a neurotransmitter. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:748–755. doi: 10.1038/nrn916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dunwiddie TV, Masino SA. The role and regulation of adenosine in the central nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:31–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pascual O, Casper KB, Kubera C, Zhang J, Revilla-Sanchez R, Sul JY, Takano H, Moss SJ, McCarthy K, Haydon PG. Astrocytic purinergic signaling coordinates synaptic networks. Science. 2005;310:113–116. doi: 10.1126/science.1116916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dulla CG, Dobelis P, Pearson T, Frenguelli BG, Staley KJ, Masino SA. Adenosine and atp link p(co(2)) to cortical excitability via ph. Neuron. 2005;48:1011–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Melani A, Turchi D, Vannucchi MG, Cipriani S, Gianfriddo M, Pedata F. Atp extracellular concentrations are increased in the rat striatum during in vivo ischemia. Neurochem Int. 2005;47:442–448. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simard M, Arcuino G, Takano T, Liu QS, Nedergaard M. Signaling at the gliovascular interface. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9254–9262. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-27-09254.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anderson CM, Nedergaard M. Astrocyte-mediated control of cerebral microcirculation. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:340–344. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00141-3. author reply 344−345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mulligan SJ, MacVicar BA. Calcium transients in astrocyte endfeet cause cerebrovascular constrictions. Nature. 2004;431:195–199. doi: 10.1038/nature02827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petzold GC, Albeanu DF, Sato TF, Murthy VN. Coupling of neural activity to blood flow in olfactory glomeruli is mediated by astrocytic pathways. Neuron. 2008;58:897–910. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davalos D, Grutzendler J, Yang G, Kim JV, Zuo Y, Jung S, Littman DR, Dustin ML, Gan WB. Atp mediates rapid microglial response to local brain injury in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2005 doi: 10.1038/nn1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nimmerjahn A, Kirchhoff F, Helmchen F. Resting microglial cells are highly dynamic surveillants of brain parenchyma in vivo. Science. 2005 doi: 10.1126/science.1110647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sasaki Y, Hoshi M, Akazawa C, Nakamura Y, Tsuzuki H, Inoue K, Kohsaka S. Selective expression of gi/o-coupled atp receptor p2y12 in microglia in rat brain. Glia. 2003;44:242–250. doi: 10.1002/glia.10293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koizumi S, Shigemoto-Mogami Y, Nasu-Tada K, Shinozaki Y, Ohsawa K, Tsuda M, Joshi BV, Jacobson KA, Kohsaka S, Inoue K. Udp acting at p2y6 receptors is a mediator of microglial phagocytosis. Nature. 2007;446:1091–1095. doi: 10.1038/nature05704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oberheim NA, Wang X, Goldman S, Nedergaard M. Astrocytic complexity distinguishes the human brain. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:547–553. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pfrieger FW, Barres BA. Synaptic efficacy enhanced by glial cells in vitro. Science. 1997;277:1684–1687. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berridge MJ, Lipp P, Bootman MD. The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:11–21. doi: 10.1038/35036035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arcuino G, Lin JH, Takano T, Liu C, Jiang L, Gao Q, Kang J, Nedergaard M. Intercellular calcium signaling mediated by point-source burst release of ATP. Proc Natl Aca Sci. USA. 2002;99(15):9840–9845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152588599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]