Abstract

Motivation: Statistical methods are used to test for the differential expression of genes in microarray experiments. The most widely used methods successfully test whether the true differential expression is different from zero, but give no assurance that the differences found are large enough to be biologically meaningful.

Results: We present a method, t-tests relative to a threshold (TREAT), that allows researchers to test formally the hypothesis (with associated p-values) that the differential expression in a microarray experiment is greater than a given (biologically meaningful) threshold. We have evaluated the method using simulated data, a dataset from a quality control experiment for microarrays and data from a biological experiment investigating histone deacetylase inhibitors. When the magnitude of differential expression is taken into account, TREAT improves upon the false discovery rate of existing methods and identifies more biologically relevant genes.

Availability: R code implementing our methods is contributed to the software package limma available at http://www.bioconductor.org.

Contact: smyth@wehi.edu.au

1 INTRODUCTION

In gene expression analysis, what does it mean to claim that a gene is differentially expressed? In formal statistical terms, a gene is differentially expressed if its expression level changes systematically between two treatment conditions, regardless of how small the difference might be. On the other hand, in scientific discussion, a gene is likely to be considered differentially expressed only if its expression level changes by a worthwhile amount. There is therefore a disconnect between the mathematical and biological concepts of differential expression. In this article, we move the concept of statistical significance to be closer to the biological concept of differential expression.

The earliest microarray publications judged differential expression purely in terms of fold-change (DeRisi et al., 1996; Schena et al., 1996), with 2-fold typically considered a worthwhile cutoff. However, fold-change cutoffs do not take variability into account or guarantee reproducibility, so it soon become popular to use traditional statistical tests such as the t-test or the Wilcoxon test. These in turn were soon found to give high false discovery rates (FDRs) in small samples, and to be only weakly related to fold-change.

A new generation of statistical tests has been developed for the microarray context in recent years, introducing tests that borrow information between genes using empirical Bayes and other statistical means (Baldi and Long, 2001; Efron et al., 2001; Lönnstedt and Speed, 2002; Smyth, 2004; Tusher et al., 2001; Wright and Simon, 2003). These tests have been consistently shown to outperform traditional genewise statistical tests, and to give results more in line with fold-change rankings (Jeffery et al., 2006; Kooperberg et al., 2005; Shi et al., 2005; Xie et al., 2004).

However, even these modern statistical tests permit genes with arbitrarily small fold-changes to be considered statistically significant. Hence, it has become increasingly common to require that differentially expressed genes satisfy both p-value and fold-change criteria simultaneously. Patterson et al. (2006) required genes to satisfy a modest level of statistical significance (p <0.01 or p <0.05) then ranked significant genes by fold-change with a cutoff of 1.5, 2 or 4. They found that this combination ranking gave much better agreement between platforms than p-value alone. Other studies have applied a fold-change cutoff and then ranked by p-value. Peart et al. (2005) and Raouf et al. (2008) declare genes to be differentially expressed if they show a fold-change of at least 1.5 and also satisfy p <0.05 after adjustment for multiple testing. Huggins et al. (2008) required a 1.3 fold-change and p <0.2. These combination criteria typically find more biologically meaningful sets of genes than p-values alone.

The combination approaches remain ad hoc. If the FDR is controlled at a certain level using p-values, but a fold-change cutoff is applied as well, then the expected FDR must decrease, but by how much is unclear. At the same time, the fold-change cutoff does not take variability into account, so there is no statistical confidence that the genes will achieve the same fold-change threshold in future experiments or studies. Hence, a more formal approach for combining statistical significance and fold-change is desirable.

We present a new method for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments, t-tests relative to a threshold (TREAT). This method is an extension of the empirical Bayes moderated t-statistic presented by Smyth (2004), and can be used to test whether the true differential expression is greater than a given threshold value. By including the fold-change threshold of interest in a formal hypothesis test, we achieve reliable p-values and FDRs for finding genes with differential expression that is biologically meaningful.

The biological significance of a given fold-change is likely to depend on the gene and on the experimental context. On the other hand, it is reasonable to assume that there is a minimum fold-change threshold below which differential expression is unlikely to be of interest for any gene. We assume throughout this article that such a minimum fold-change threshold can be specified for the experiment at hand.

2 APPROACH

2.1 Hypotheses relative to a threshold

Let βg be the log-fold-change for gene g relating to some comparison of interest. In the simplest case, βg might be the log-fold-change in expression between two treatment groups or between affected and unaffected patients. The classical test of differential expression would test the null hypothesis H0: βg=0 against the alternative H1: βg≠0. We test instead the thresholded null hypothesis that H0: |βg|≤τ against the alternative H1: |βg|>τ, where τ is a pre-specified threshold for the log-fold-change below which differential expression is not of material interest.

Note that standard statistical theory does not provide an exact test of the thresholded null hypothesis, even for normally distributed data. The thresholded null hypothesis is a composite hypothesis in that it specifies an interval of values for βg rather than a single value (Cox and Hinkley, 1974). The standard statistical approach would be to construct a likelihood ratio test of H0 versus H1, and then to apply asymptotic distribution theory. Our aim, however, is to borrow information between genes, and to calculate an exact p-value for the thresholded test.

2.2 Linear models for microarray data

In order to be completely general, we adopt the linear model setup of Smyth (2004). In this approach, the design of any microarray experiment can be represented in terms of a linear model for each gene. Assume that we have a set of n independent microarrays yielding a response vector ygT=(yg1,…, ygn for the g-th gene. The responses are assumed to be suitably normalized and will usually be log-ratios for two-colour data or log-intensities for single-channel data. Assume that

where X is a design matrix of full column rank and αg is an unknown coefficient vector. The experimental design is captured by the matrix X. For example, for a simple two-group comparison, X would contain two columns, one an intercept column and the other an indicator vector for the two groups.

We assume

where σ2g is the unknown genewise variance and Wg is a known non-negative definite weight matrix. The weights W may for example represent quality weights for the individual observations.

Suppose that the contrast we wish to test is βg=cT αg, where c is a constant vector. For example, in the two-group comparison, we might have cT=(0, 1) to pick out the coefficient relating to the difference between the two groups.

The linear model is fitted to the responses for each gene to obtain coefficient estimator  and variance estimator sg2 of σg2. The fitting might be by least squares, or perhaps by a robust estimation criteria, but in any case the covariance of the coefficients can be written

and variance estimator sg2 of σg2. The fitting might be by least squares, or perhaps by a robust estimation criteria, but in any case the covariance of the coefficients can be written

where Vg is a positive definite matrix not depending on σg2. If the fitting of the linear model is by least squares, then Vg=(XT WgX)−1. The corresponding estimate for βg is

The responses yg are not necessarily assumed to be normal and the fitting of the linear model is not assumed to be by least squares. Nevertheless, we do assume  to be approximately normal with mean βg and the residual variances sg2 to follow approximately a scaled χ2-distribution. The distributional assumptions we make can be summarized by

to be approximately normal with mean βg and the residual variances sg2 to follow approximately a scaled χ2-distribution. The distributional assumptions we make can be summarized by

where vg=cTVgc, and

where dg is the residual degrees of freedom for the linear model for gene g. Under these assumptions the ordinary t-statistic

follows a t-distribution on dg degrees of freedom.

2.3 Hierarchical model

The same linear model is fitted to each gene, resulting in a large number of fits with the same structure. A simple hierarchical model can reflect this parallel structure by describing how the unknown coefficients and variances vary across genes (Lönnstedt and Speed, 2002; Smyth, 2004; Wright and Simon, 2003). This is achieved by assuming prior distributions for these sets of parameters.

Assume an inverse-χ2 prior for σg2 located at prior estimate s02 with d0 degrees of freedom, i.e.

| (1) |

This describes how the variances are expected to vary across genes.

Under this hierarchical model, the posterior mean of σg−2 given sg2 is

The posterior variances shrink the observed variances towards the prior value with the degree of shrinkage depending on the relative sizes of the observed and prior degrees of freedom. Smyth (2004) defines the moderated t-statistic by

| (2) |

This statistic represents a hybrid classical and Bayesian approach in which the posterior variance has been substituted into the classical t-statistic in place of the usual sample variance. Under the null hypothesis that βg=0, the moderated t follows a t-distribution on dg+d0 degrees of freedom (Smyth, 2004; Wright and Simon, 2003). Furthermore,  and

and  are distributed independently of one another (Smyth, 2004), a feature we will use below. The increased degrees of freedom for the moderated over the ordinary t-statistic reflects the extra information borrowed from the ensemble of genes for inference about each individual gene.

are distributed independently of one another (Smyth, 2004), a feature we will use below. The increased degrees of freedom for the moderated over the ordinary t-statistic reflects the extra information borrowed from the ensemble of genes for inference about each individual gene.

2.4 Testing relative to a threshold

Consider now the thresholded hypotheses defined above, and write tobs for the observed value of the moderated t-statistic  . We wish to obtain an expression for the p-value

. We wish to obtain an expression for the p-value  given H0.

given H0.

First observe that if βg=β0, then the re-centered t-statistic

inherits the properties of the moderated t-statistic, following a t-distribution on d0+dg independently of  .

.

Note also that the distribution of  does not depend on βg, our parameter of interest (Smyth, 2004). In other words,

does not depend on βg, our parameter of interest (Smyth, 2004). In other words,  is an ancillary statistic. It is a general principle that test statistics can be made more precise, with gain of statistical power, by conditioning on ancillary statistics (Cox and Hinkley, 1974). Hence, we compute p-values conditional on

is an ancillary statistic. It is a general principle that test statistics can be made more precise, with gain of statistical power, by conditioning on ancillary statistics (Cox and Hinkley, 1974). Hence, we compute p-values conditional on  .

.

Without loss of generality, assume tobs > 0. Write  for the observed value of

for the observed value of  . The conditional p-value is defined by

. The conditional p-value is defined by

This probability is problematic to calculate because H0 refers to an interval of possible values for βg. However, an upper bound can be found by choosing that element of H0 which is the most difficult to reject. Thus, the conditional p-value can be bounded above by

where β0 is the value of the null hypothesis closest to  , i.e.

, i.e.  . We adopt this upper bound as our p-value estimate, understanding that, being a worst-case calculation, it is somewhat conservative. It can be expanded as the sum of two tail probabilities

. We adopt this upper bound as our p-value estimate, understanding that, being a worst-case calculation, it is somewhat conservative. It can be expanded as the sum of two tail probabilities

Write

Note that  and that δ can be treated as a constant, conditional on

and that δ can be treated as a constant, conditional on  . Our conservative p-value is therefore the sum of two t-distribution tail probabilities,

. Our conservative p-value is therefore the sum of two t-distribution tail probabilities,

|

where F() is the upper-tail probability function of the t-distribution on d0+dg degrees of freedom. This yields an easily computable conservative p-value for testing the thresholded null hypothesis. We call the resulting statistical test TREAT.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Comparisons

We compared TREAT with five other methods for ranking genes in terms of evidence for differential expression. The six methods were compared in situations where the magnitude of the differential expression was taken into account. Only genes with ‘true’ differential expression greater than a threshold τ were deemed to be differentially expressed. Knowledge of which genes are ‘truly’ differentially expressed and which are not, allows us to compare the methods on the basis of FDR and the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. TREAT is compared with the

ordinary t-statistic;

moderated t-statistic;

ordinary fold-change;

fold-change with moderated t-value cutoff; and

moderated t with fold-change cutoff.

Methods (4) and (5) are ad hoc methods that attempt to combine moderated t and fold-change. Both reflect approaches used in practice. For method (5), genes are ordered on the magnitude of the moderated t-statistic, but only genes with a fold-change greater than the given threshold value are considered differentially expressed, equivalent to the method used by Peart et al. (2005). Method (4) is similar, but opposite—genes are ordered on the absolute value of the log-fold-change, but genes with adjusted p-values from the moderated t-statistic less than a given cutoff value (usually <0.05) are ranked higher than genes with adjusted p-values larger than the cutoff. Any method of adjusting the p-values for multiple testing can be used; in the following analyses, we use the method described by Benjamini and Hochberg (1995). Patterson et al. (2006) take a similar approach to method (4), although without adjusting p-values for multiple testing.

3.2 Simulated data

Using the distributional assumptions presented above, we simulated 1000 realizations of a microarray experiment involving 15 000 genes. Parameter values were selected to reflect realistic values for a typical microarray experiment. For each dataset, we first simulated values for σg2, the true variance of each gene, from the assumed distribution given in (1). We set d0=4 and s0=0.07. These values for σg2 were then used to generate some random values for βg from a normal distribution with mean of zero and variance of v0σg2, where v0=8. Genes with a βg > log21.5, i.e. a fold-change > 1.5, were defined as differentially expressed.

These values for βg were used to give the ‘true’ βg-values for our simulation. We set 60% of the 15 000 genes are set to have true βg=0, and the remaining 40% have true βg-values taken from the simulated set above—some of these 40% of genes are truly differentially expressed under our definition, i.e. have fold-change > 1.5, and the rest are defined as not differentially expressed, although their true βg is non-zero. On average, about 4% of the genes in each dataset were defined as truly differentially expressed.

The ‘observed’ values  and sg2 are then simulated according to the assumptions in Section 2.2, using our simulated ‘true’ values for βg and σg2, and with v1=(1/n1+1/n2), n1=n2=2 and dg=2. This simulates a two-group comparison with two arrays in each group. These ‘observed’ values were then analysed using the six different methods described above.

and sg2 are then simulated according to the assumptions in Section 2.2, using our simulated ‘true’ values for βg and σg2, and with v1=(1/n1+1/n2), n1=n2=2 and dg=2. This simulates a two-group comparison with two arrays in each group. These ‘observed’ values were then analysed using the six different methods described above.

The ‘true’ expression levels of the genes were known in this simulation, so we could calculate the true FDR and the area under the ROC curve for each of the six methods. Each method ranks genes in order of evidence of differential expression. We find the number of genes that are not truly differentially expressed in a given number of genes as ranked by each method to give the FDR. The number of false discoveries for each number of genes selected as being differentially expressed and the area under the ROC curve for each method was averaged over the 1000 runs to provide good information on the performance of each statistic. For this analysis, we set the threshold value for TREAT to τ=log21.5, and set the p-value cutoff for method (4) to be an adjusted p-value of 0.05, and the fold-change cutoff for method (5) to 1.5.

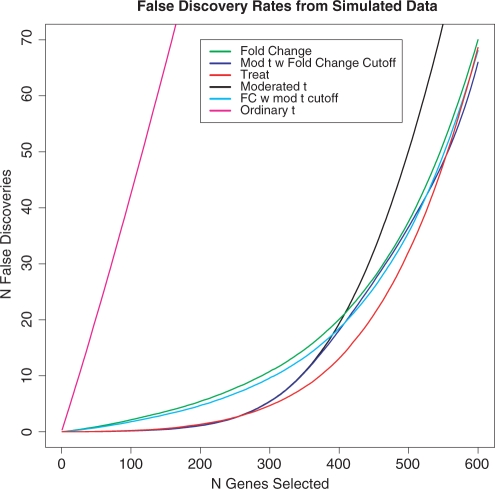

Figure 1 shows that, when used to analyse the simulated data, TREAT has the lowest FDR overall. In general, the statistics based on moderated t do best for small numbers of genes, whereas methods based on fold-change do best for large numbers of genes. TREAT successfully combines the advantages of both types of statistic, matching the best statistics at the two extremes, and having clearly lowest FDR of all the methods for the intermediate range of 250–500 genes selected. Above about 600 genes selected, all the methods which use fold-change are similar. Table 1 shows that TREAT has the highest area under the ROC curve, confirming it is the best overall method for these data. Ordinary t is by far the worst-performing method.

Fig. 1.

FDRs for six different gene selection statistics from the analysis of simulated data. The rates are the means of actual FDRs for 1000 simulated datasets.

Table 1.

Area under the ROC curve for six methods and two datasets, one simulated and the other real experimental data from the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre (PMCC)

| Method | Simulated data | PMCC data |

|---|---|---|

| Ordinary t | 0.9526 | 0.7852 |

| Moderated t | 0.9919 | 0.9723 |

| Fold-change | 0.9967 | 0.9819 |

| Fold-change with moderated t cutoff | 0.9963 | 0.9801 |

| Moderated t with fold-change cutoff | 0.9944 | 0.9761 |

| TREAT | 0.9970 | 0.9832 |

TREAT has the highest area under the ROC curve (values in bold) for both the simulated data and the data from the PMCC quality control experiment.

3.3 Quality control data

We also used data from a real experiment to compare the different methods. The dataset consists of 100 replicate two-colour cDNA arrays from an experiment done at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre designed for quality control of the microarray platform being used (Ritchie et al., 2006). One array which contained some missing values was discarded. Each array was printed with 10 944 human probes and was hybridized with Jurkat (Cy3) and MCF7 (Cy5) RNA. The two samples used are from different cell-types, so atypically for a microarray experiment, most of the genes are differentially expressed. We compared methods by analysing two randomly selected arrays for each of 1000 runs. ‘Truly’ differentially expressed genes were determined for each run by constructing 95% confidence intervals for the true expression levels using the 97 arrays not used for analysis in that particular run.

As there was a great deal of differential expression for these arrays, we set our threshold value to τ=log22. Genes were flagged as differentially expressed (roughly 800 in each run) if they had a confidence interval completely outside of [−τ, τ], and as not differentially expressed if the confidence interval was completely inside of [−τ, τ]. Genes with confidence intervals that contained −τ or τ, about 9% of genes for each run, were omitted from the analysis. As for the simulated data, we calculated the FDR and the area under the ROC curve for each of the six statistics for each run. For method (4) we set the cutoff value for the adjusted p-value to 0.2, and we set the cutoff fold-change for method (5) to be 2.

As for the simulated data, the number of false discoveries for each number of genes selected as being differentially expressed and the area under the ROC curve for each method was averaged over the 1000 runs to provide good information on the performance of each statistic.

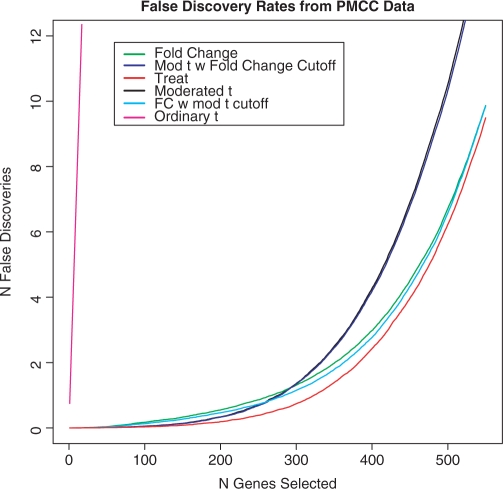

Figure 2 shows that TREAT has the lowest FDR of all the methods. When more than 100 genes are selected, TREAT clearly outperforms the other methods. It is only when fewer than 100 genes are selected, that the FDR for the two methods based on moderated t is equal to that of TREAT. Table 1 shows that TREAT has the highest area under the ROC curve when analysing these data, which shows that TREAT is the best method over the full range of number of genes selected. TREAT proves to be the superior method for analysing these data when the magnitude of differential expression is taken into account.

Fig. 2.

FDRs for six different gene selection statistics from the analysis of real experimental data. The dataset was produced by a quality control experiment conducted at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre. The rates are the means of the actual FDRs from 1000 analyses of pairs of arrays selected at random from the 99 replicate arrays in the dataset.

3.4 Biological data

To compare further the performance of TREAT and the moderated t, we analysed data from Peart et al. (2005). This experiment was designed to investigate histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACis), in particular their effects on gene regulation in a tumorigenic cell line over a 16 h time course. The cDNA microarrays were used to compare gene expression at five different time points (1, 2, 4, 8 and 16 h) after treatment by two HDACis, suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) and depsipeptide, to gene expression (GOs) in untreated cells.

Of particular, interest are genes which respond differently over time to the two HDACis. As described by Peart et al. (2005), we used an interaction model to compare the response to SAHA versus the response to depsipeptide at the 16 h point. The analysis was done using the limma software package (Smyth, 2005) for R (R Development Core Team, 2006), controlling the FDR at 0.05 using the Benjamini and Hochberg (1995) method. For the TREAT statistic, the threshold log-fold-change was set to τ=log21.1. This threshold, corresponding to 10% fold-change, was chosen based on our experience that fold-changes so small are virtually never of scientific interest, and also because this cutoff gives a similar number of DE genes to the 1.5 fold-change cutoff used by Peart et al. (2005).

Moderated t identified 982 genes as having a significantly higher response to SAHA than to depsipeptide at 16 h, and 1043 genes with significantly lower response in SAHA versus depsipeptide at 16 h. As expected, TREAT found somewhat fewer genes as significant, 646 higher and 674 lower at 16 h (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of genes identified by moderated t and TREAT as having higher or lower response to SAHA versus depsipeptide at 16 h, and the number of these genes also detected at the previous time point 8 h

| Method | Direction | 16 h | 8 h | Overlap (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderated t | Up | 982 | 271 | 27.6 |

| Down | 1043 | 216 | 20.7 | |

| TREAT | Up | 646 | 280 | 43.3 |

| Down | 674 | 204 | 30.3 |

The data come from a biological experiment investigating HDACis. The final column gives the proportion of genes differentially expressed at 16 h that were also differentially expressed at 8 h.

To give an indication of how many genes are of genuine interest, we checked which genes significant at 16 h were also detectable at 8 h. We checked differential expression without regard to fold-change at 8 h. Of the genes found by moderated t, 271/982 genes were already up at 8 h and 216/1043 genes found to already down at 8 h. For genes found by TREAT, 280/646 were already up at 8 h and 204/674 were already down at 8 h. TREAT gives a much better overlap between 8 and 16 h than does moderated t, finding just as many overlapping genes on a smaller base (Table 2). As genes of genuine interest are likely to give consistent results over several consecutive times, we conclude that TREAT does a better job of identifying the most important responding genes.

In order to compare the biological information provided by TREAT and moderated t, we used a DAVID search (Dennis et al., 2003) to find relevant gene ontologies (GOs) from the lists of significantly differentially expressed genes at 16 h. The DAVID tool conducts a statistical test based on Fisher's Exact test to measure gene-enrichment in annotation terms. The tool also reports FDRs, calculated in a way similiar to the approximate FDR described by Benjamini and Hochberg (1995). In our analysis, GO categories were judged to be significant if they had a reported FDR <5%. TREAT and moderated t identified mostly the same GO categories. However, TREAT was successful at identifying a number of highly relevant GO categories which were missed by moderated t. These interesting gene ontology groups included DNA metabolic process, DNA damage, response to DNA damage stimulus, response to stress, DNA repair, response to endogenous stimulus, regulation of apoptosis and regulation of programmed cell death (Table 3). These are typically key processes in investigating responses to HDACis (Peart et al., 2005). No interesting categories were identified by moderated t but not by TREAT. We conclude that the larger list of genes returned by moderated t dilutes the biological results somewhat by including more genes with small fold-changes.

Table 3.

Relevant gene ontology groups from the analysis of the HDACi data that were identified as significant when using TREAT, but not when using moderated t

| Relevant gene ontology groups identified by TREAT, but not moderated t |

|---|

| DNA metabolic process |

| DNA damage |

| DNA repair |

| Response to DNA damage stimulus |

| Response to endogenous stimulus |

| Response to stress |

| Regulation of apoptosis |

| Regulation of programmed cell death |

These are typically key processes in assessing responses to HDACis. Groups were found using a DAVID search from the lists of significantly differentially expressed genes found using the two methods. Ontologies were found to be significant if they had an FDR <5%.

4 DISCUSSION

The results from our analysis of the simulated and PMCC datasets show that the traditional t-test is by far the worst and TREAT is the best of the methods considered at ranking genes in terms of evidence for differential expression, when the magnitude of differential expression is taken into account. TREAT outperforms other methods which select genes on fold-change or which combine t-tests and fold-changes in various ways. TREAT has the lowest FDR and greatest area under the ROC curve for both simulated and PMCC data. Our functional analysis of the biological data shows that the information about gene ontologies provided by TREAT is more focused than that provided by moderated t, in that TREAT identifies the same biologically informative genes with less dilution by uninteresting genes.

A further advantage of TREAT is that it provides valid p-values for any threshold value. None of its closest competitors in terms of gene rankings [methods (3)–(5) here] give p-values at all. The p-values provided by TREAT can be adjusted for multiple testing to provide control of the family wise error rate or the FDR, particularly useful in the microarray context.

It is interesting to note a connection with the theory of equivalence testing (Wellek, 2002), which also considers thresholded null hypotheses similar to those considered here. In equivalence testing, however, the role of the null and alternative hypotheses are reversed, with the emphasis on proving, for example, that two drugs are bioequivalent. In the microarray context considered here, we wish to retain the traditional hypothesis testing view that the null hypothesis is the status quo.

The p-values returned by TREAT are larger than those from the moderated t-statistic, and usually although not always larger than those from other methods which test the hypothesis that the true differential expression is zero. At first glance this might seem to show that TREAT is less powerful than conventional tests, but in reality TREAT is testing a different hypothesis. TREAT requires stronger evidence of differential expression, including a sufficiently large fold-change, to identify a gene as significant, than does moderated t or similar methods. Thus, while TREAT generally returns fewer genes than conventional tests, TREAT offers greater specificity for identifying the most important genes.

TREAT returns slightly conservative p-values, an inevitable side-effect of testing a composite null hypothesis. This means that the true FDR is likely to be better than the nominal rate suggested by the p-values. An unavoidable consequence is that the TREAT p-values do not follow perfectly the traditional uniform distribution for genes which are genuinely not differentially expressed. Rather, the null distribution of the TREAT p-values is somewhat skewed towards larger values. While TREAT p-values can be used with most multiple testing adjustment schemes, including Benjamini and Hochberg (1995), they do not fulfil the assumptions of some methods which try to estimate the proportion of truly null genes such as Ferkingstad et al. (2005).

The TREAT fold-change threshold should be set to a low value below which no fold-change is likely to be of genuine interest. Researchers should be mindful that genes will need to exceed this threshold by some way, depending on the data, before being declared statistically significant. Our experience suggests a minimal value, such as a 10% fold-change, corresponding to τ=log2(1.1)=0.13 on the log2-scale. It would be better to interpret the threshold as ‘the fold-change below which we are definitely not interested in the gene’ rather than ‘the fold-change above which we are interested in the gene’.

The TREAT threshold can be varied as appropriate for the data at hand. If the molecular perturbation being studied produces dramatic and promiscuous expression changes, then a relatively large threshold may be appropriate to narrow down the search to those genes and pathways of most influence. For example, Peart et al. (2005) found >40% of all genes on the genome changing at a 5% FDR. Gene knock-out experiments also often produce clear-cut phenotypes and large differential expression changes, although perhaps restricted to a smaller number of genes. On the other hand, if the expression changes in the dataset are more subtle then a small threshold (or even no threshold) can be used. For example, physiological variations may be associated with molecular changes which might be widespread, but are small in magnitude. If the threshold level is set to zero, then TREAT reduces to the moderated t-statistic presented by Smyth (2004).

TREAT is the best method when the magnitude of the differential expression is taken into account. TREAT offers advantages over existing methods by providing a formal hypothesis test and rigorous associated p-values, achieved by conditioning on an ancillary statistic. TREAT should prove especially useful in analysing microarray experiments in which there is a large amount of differential expression by testing formally for differential expression that is not only statistically significant but also biologically meaningful.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Alicia Oshlack for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Funding: NHMRC Program (grant 406657 to D.J.M. and G.K.S.); NHMRC IRIISS (grant 361646 to D.J.M. and G.K.S.); Victorian State Government OIS grant.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Baldi P, Long AD. A Bayesian framework for the analysis of microarray expression data: regularized t-test and statistical inferences of gene changes. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:509–519. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.6.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR, Hinkley DV. Theoretical Statistics. London: Chapman and Hall; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis G, et al. DAVID: database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRisi J, et al. Use of a cDNA microarray to analyse gene expression patterns in human cancer. Nat. Genet. 1996;14:457–460. doi: 10.1038/ng1296-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, et al. Empirical Bayes analysis of a microarray experiment. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2001;96:1151–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Ferkingstad E, et al. Estimating the proportion of true null hypotheses, with application to DNA microarray data. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B. 2005;67:555–572. [Google Scholar]

- Huggins CE, et al. Functional and metabolic remodelling in GLUT4-deficient hearts confers hyper-responsiveness to substrate intervention. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2008;44:270–280. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery IB, et al. Comparison and evaluation of methods for generating differentially expressed gene lists from microarray data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:359. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooperberg C, et al. Significance testing for small microarray experiments. Stat. Med. 2005;24:2281–2298. doi: 10.1002/sim.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lönnstedt I, Speed T. Replicated microarray data. Stat. Sinica. 2002;12:31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TA, et al. Performance comparison of one-color and two-color platforms within the MicroArray Quality Control (MAQC) project. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:1140–1150. doi: 10.1038/nbt1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peart MJ, et al. Identification and functional significance of genes regulated by structurally different histone deacetylase inhibitors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:3697–3702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500369102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. Vienna, Austria: 2006. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Raouf A, et al. Transcriptome analysis of the normal human mammary cell commitment and differentiation process. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie ME, et al. Empirical array quality weights for microarray data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:261. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schena M, et al. Parallel human genome analysis: microarray-based expression monitoring of 1000 genes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:10614–10619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, et al. Cross-platform comparability of microarray technology: intra-platform consistency and appropriate data analysis procedures are essential. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;15(Suppl 2):S12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-S2-S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. 2004;3 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. Article 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK. Limma: linear models for microarray data. In: Gentleman R, et al., editors. Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions using R and Bioconductor. New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 397–420. [Google Scholar]

- Tusher VG, et al. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellek S. Testing Statistical Hypotheses of Equivalence. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wright GW, Simon RM. A random variance model for detection of differential gene expression in small microarray experiments. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:2448–2455. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, et al. A case study on choosing normalization methods and test statistics for two-channel microarray data. Comp. Funct. Genomics. 2004;5:432–444. doi: 10.1002/cfg.416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]