Abstract

The Mhc is a highly conserved gene region especially interesting to geneticists because of the rapid evolution of gene families found within it. High levels of Mhc genetic diversity often exist within populations. The chicken Mhc is the focus of considerable interest because of the strong, reproducible infectious disease associations found with particular Mhc-B haplotypes. Sequence data for Mhc-B haplotypes have been lacking thereby hampering efforts to systematically resolve which genes within the Mhc-B region contribute to well-defined Mhc-B-associated disease responses. To better understand the genetic factors that generate and maintain genomic diversity in the Mhc-B region, we determined the complete genomic sequence for 14 Mhc-B haplotypes across a region of 59 kb that encompasses 14 gene loci ranging from BG1 to BF2. We compared the sequences using alignment, phylo-genetic, and genome profiling methods. We identified gene structural changes, synonymous and non-synonymous polymorphisms, insertions and deletions, and allelic gene rearrangements or exchanges that contribute to haplotype diversity. Mhc-B haplotype diversity appears to be generated by a number of mutational events. We found evidence that some Mhc-B haplotypes are derived by whole- and partial-allelic gene conversion and homologous reciprocal recombination, in addition to nucleotide mutations. These data provide a framework for further analyses of disease associations found among these 14 haplotypes and additional haplotypes segregating and evolving in wild and domesticated populations of chickens.

The Mhc is a genomic region that encodes molecules that provide the context in which T cells recognize foreign Ags and it is found in all but the most primitive vertebrates (1). Although polymorphism is a prominent, commonly encountered feature of the Mhc, presumably as a result of pathogen selection, it is generally difficult to find associations between Mhc polymorphism and infectious disease outcome. In this regard, the chicken Mhc-Bregion is the exception. Strong, reproducible associations exist between Mhc-B haplotypes and their response to diseases caused by several different pathogens (2–6). The chicken (Gallus domesticus) Mhc region is divided into two major parts, linkage group B (Mhc-B) and linkage group Y (Mhc-Y) (7). Mhc-B and Mhc-Y are inherited independently of each other even though they are physically linked on microchromosome 16 (GGA16) (8–11). However, it is Mhc-Brather than Mhc-Ythat has been most strongly associated with diseases caused by infection with several different pathogens. Presently, disease associations are defined at the level of the Mhc-B haplotype. The contributions of individual loci are undefined (12–14). The highly polymorphic nature of BF, BLB, and BG genes and high linkage disequilibrium that exists within this “minimal essential” Mhc (15–17) present obstacles to associating individual genes with disease responses.

Some Mhc-B haplotypes appear to have participated in past recombination events and to share alleles at the BF and BLB loci, whereas other haplotypes are closely related to one another when defined serologically, but perhaps have diversified by mutational changes or gene conversions (7, 15, 18). The result of a comparative study of two classical class I loci, BF1 and BF2, using seven Mhc-B haplotypes has implied that the two genes were generated by two different evolutionary processes, drift and selection, respectively (19). Thus, gene diversities have been reported on a restricted number of genomic segments and haplotypes, but comprehensive haplotypic DNA sequence information for the Mhc-B region has been generally lacking. Clearly, haplotype diversity information is still required to find answers to the basic questions such as why some infectious diseases are linked to the Mhc-B region and which molecular mechanism(s) generate and maintain diversity within the Mhc-B region.

To better understand the genetic factors that generate and maintain genomic diversity in the Mhc-B region, we determined the complete genomic sequence for 14 genes (59 kb) within the chicken Mhc-B region (59 kb, 14 genes) for 14 Mhc-B haplotypes. We elucidated the major molecular and evolutionary mechanisms that have contributed to haplotype diversity by comparing gene structures and polymorphisms among these Mhc-B haplotypes.

Materials and Methods

DNA samples

Genomic DNA samples were extracted from chickens in inbred or congenic lines or from homozygous chickens that were members of fully pedigreed families within closed lines in which known B haplotypes segregate. Fourteen standard Mhc-B haplotypes, distinguishable by serology and microsatellite typing (20, 21), were represented as follows: B2 Line 63 (Avian Disease and Oncology Laboratory (ADOL)), B5 Line15.15I-5 (ADOL), B6 Line GB-2 (University of Georgia), B8 Line Wis 3 (Northern Illinois University), B9 Line GVHR-HG (Hiroshima University), B11 Line Wis 3 (Northern Illinois University), B12 Line C (ADOL), B13 Line15.P-13 (ADOL), B15 Line RPRL-15I5 (Hiroshima University), B17 Line UCD003 (University of California, Davis), B19 Line P (ADOL), B21 Line N (ADOL), B23 Line UNH105 (Northern Illinois University), and B24 Line UNH105 (Northern Illinois University) (7, 20, 22). The B8 and B11 haplotypes were derived from the Ancona breed and the B23 and B24 haplotypes were derived from the New Hampshire breed, whereas all others originated from White Leghorns (20). From the serological typing of the B haplotypes in 1982, B2, B5, B6, B12, B13, B15, B19, and B21 are commonly encountered haplotypes and B8, B9, B11, B17, B23, and B24 are rare or low frequency haplotypes (21).

Long-range PCR (LR-PCR) 4 amplifications and sequencing strategy

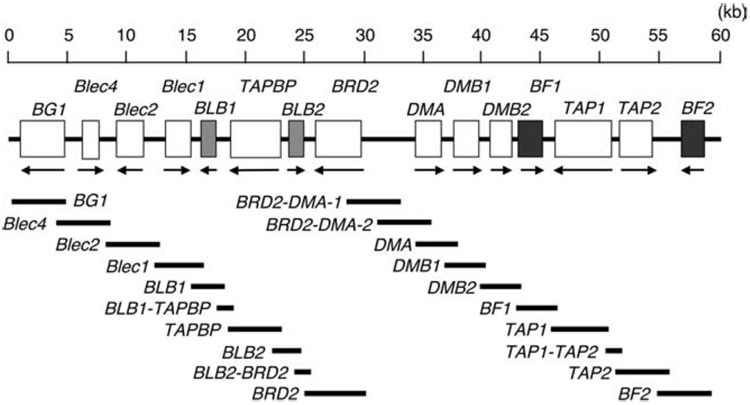

Twenty pairs of primers were designed with the assistance of Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems) for long-range PCR amplification of 14 expressed genes embedded within the 59 kb the chicken MHC-B region, ranging from BG1 to BF2 (Fig. 1). In brief, the 20-µl amplification reaction contained 100 ng of genomic DNA, 1 unit of TaKaRa LA Taq polymerase (TaKaRa Shuzo), 1× PCR buffer, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 400 µM of each dNTP, and 0.5 µM of each primer. The cycling parameters were as follows: an initial denaturation of 98°C/1 min followed by 30 cycles of 98°C/10 s and 68°C/5 min. Alternatively, the 10-µl amplification reaction contained 100 ng of genomic DNA, 1 unit of KOD-plus-DNA polymerase (Toyobo), 1× PCR buffer, 1 mM MgSO4, 200 µM of each dNTP, and 0.5 µM of each primer. The cycling parameters were as followed: an initial denaturation of 98°C/1 min followed by 30 cycles of 98°C/10 s and 68°C/3 min. The LR-PCR size is 3,565 kb on average and ranges from 899 bp to 5,771 bp (Supplemental Table IA).5 Direct sequencing was performed using the ABI Prism BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit with AmpliTaqDNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems) and 355 custom-designed sequencing primers (Supplemental Table IB). Reactions were run on ABI 3130 sequencing systems (Applied Biosystems). Gaps or areas of ambiguity were resolved after sequencing subcloned material (pGEM-T vector system, Promega). Assembly and database analyses were performed manually and using computer software following previously established procedures (23).

Figure 1.

An operational map for long-range PCR amplification of Mhc-B spanning the region from BG1 to BF2.

Sequence analyses

Nucleotide similarities among the sequences were calculated by using the GENETYX-MAC software ver 11.0 (Software Development). Multiple sequence alignments were created using the ClustalW Sequence Alignment program of the Molecular Evolution Genetics Analysis software (MEGA4; Ref.24). The phylogenetic trees were constructed by the neighbor-joining method provided in the MEGA4 software. The nucleotide diversity profiles were constructed after determining the percent nucleotide differences using DnaSP software Ver. 4.10.9 (25) between different paired combinations of the B haplotype sequences for a sliding window of 100 bp with 10 bp overlaps. The diversity profile was then drawn using the graphics output of Microsoft Excel. All insertions and deletions (indels) were removed from the alignments to standardize the number of nucleotides examined within each window. Nonsynonymous to synonymous substitution ratios (dN/dS) were calculated by the Nei and Gojobori method (26) with the P-distance parameter in the MEGA4 software.

Results

Sequence information for 14 Mhc-B haplotypes

Fig. 2 shows the gene organization and the shared alleles for the genomic DNA of 14 serological Mhc-B haplotypes (ten from White Leghorns, two (B8 and B11) from Ancona breed, and two (B23 and B24) from the New Hampshire breed) that were sequenced directly by using LR-PCR amplified products. The total length of the sequenced nucleotides per haplotype was 58,972 bp on average and ranged from 58,187 bp for B12 haplotype to 59,621 bp for B13 (GenBank Acc. Nos. AB426141 to AB426154). All Mhc-B haplotype sequences have 14 gene loci including some duplicated gene pairs, such as BLB1 and BLB2 or BF1 and BF2, but without the extensive gene duplications that were observed in quail orthologous region (27). The overall 10.7 kb of overlapping sequence had no nucleotide differences establishing our LR-PCR sequencing approach provided as high quality sequence data and confirming that the DNA samples were from Mhc-B homozygous animals.

Figure 2.

Allelic configuration of 14 gene loci for 14 chicken Mhc-B haplotypes. Haplotype numbers B2 to B24 are listed vertically on the left-handed side of the figure and the consecutive gene names BG1 to BF2 are presented horizontally at the top of the figure. Dark blue boxes indicate shared gene alleles perfectly matched in both amino acid and nucleotide sequences. Light blue boxes indicate perfect matches only within the amino acid sequences. Numbers in the boxes represent the allele identity. For example, the gene loci BLB1*B6 and BLB1*B8 belong to the identical allelic group 2 and they have perfectly matched amino acid and nucleotide sequences in the coding sequences. BLB1*B9 and BLB1*B11 belong to the identical allelic group 5 but match perfectly only in amino acid sequence. Orange and yellow backgrounds illustrate wide-ranged allele shared regions in B5, B8, and B11 and B12 and B19, respectively. Identification of allele sharing between different haplotypes is supported by the phylogenetic trees reconstructed for each locus in Supplemental Fig. 1B.

Genomic sequence diversity (SNPs and indels) within the Mhc-B region

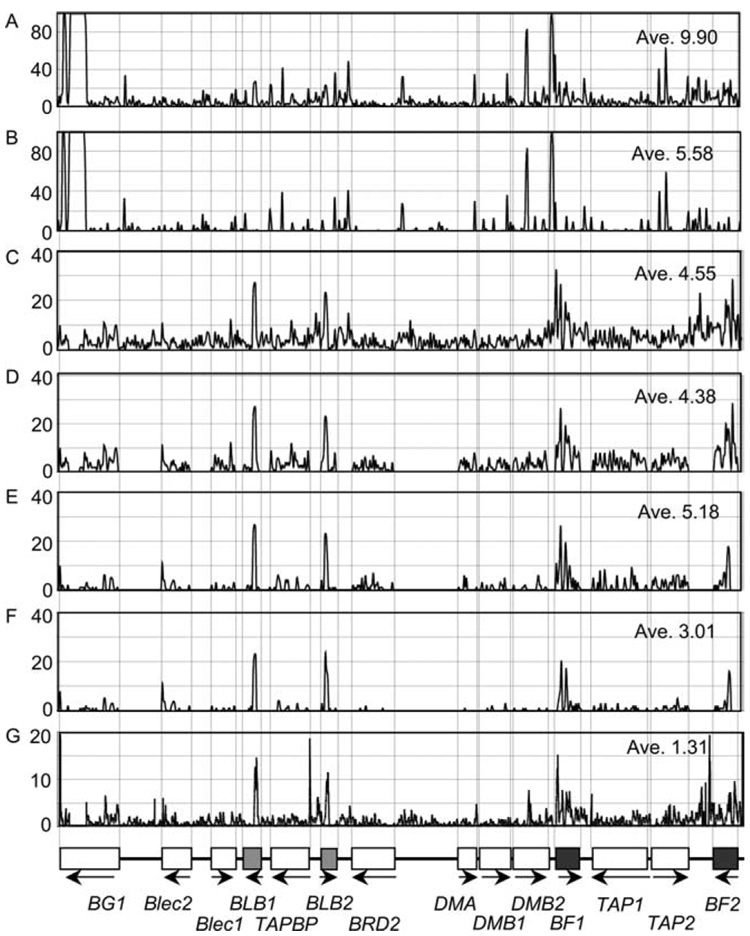

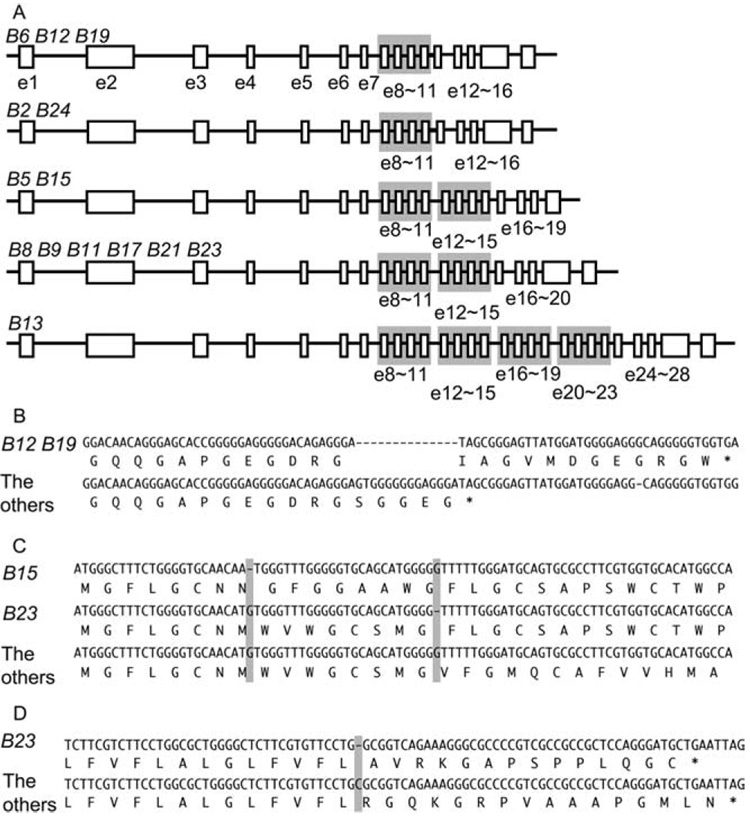

To investigate the contribution of nucleotide insertions and deletions (indels) to the Mhc-B haplotype genomic diversity, we used the computer program CLUSTALW to construct and compare a 61,046 bp alignment composed of the 14 haplotypes. We found 3,419 indels across the aligned sequences with an average indel number of 5.60 per 100 aligned nucleotides (5.60 indel%). Numerous indels were observed particularly within the introns and exons of BG1, DMB2, and TAP2 and around their intergenic regions (Fig. 3). From the alignment, structural differences were also observed at eight locations of four gene loci, BG1, TAP1, BLB1, and DMB1 (Fig. 4). In BG1, these differences result in five BG1 alleles (B2, B6, B12, B19, and B24) with 16 exons, while other alleles have 19 (B5 and B15), 20 (B8, B9, B11, B17, B21, and B23) and 28 exons (B13). These indels result in coding sequences length variants from 954 to 1,281 bp (Fig. 4A). In TAP1 exon 11 in B12 and B19 haplotypes (TAP1*B12 and TAP1*B19) are composed of 249 bp, but those in the other haplotypes are 228 bp (Fig. 4B). Single nucleotide deletions appear to have caused frame shift mutations in exon 1 of DMB1*B15 and DMB1*B23 and in exon 4 of BLB1*B23 (Fig. 4, C and D).

Figure 3.

Positional distributions of genomic sequence variations; such as all variations (A), indels (B), SNPs (C), SNPs within loci (D), coding SNPs (E), nonsynonymous coding SNPs (F), and pair-wise variations (G) among the 14 Mhc-B haplotype sequences.

Figure 4.

Structural differences observed in BG1 (A), TAP1 (B), BLB1 (C), and DMB1 (D) among the 14 Mhc-B haplotypes.

Fig. 3 shows the average variation and the positional distributions of the total SNPs, SNPs within loci, coding SNPs, and the non-synonymous coding SNPs for the 14 chicken Mhc-B haplotype sequences. Of the aligned 57,627 bp sequences excluding indels for each haplotype, 2,737 SNPs were counted, i.e., 4.48 SNPs per 100 nucleotides (4.48 SNP%) with an average pair-wise (normalized) SNP% of 1.36%. Of the 2,737 SNPs, 1,168 were singleton SNPs, i.e., the nucleotide substitution was present in only one of the 14 haplotypes. The singleton SNPs ranged from none in B12 (relative to itself as the control haplotype) to 176 in B15 (83 SNPs on average). Of the 2,737 SNPs, 1,705 SNPs were located within the 14 gene loci with an average SNP% of 4.36% and a strong regional bias (Fig. 3). The greatest overall sequence diversity was observed in the polymorphic loci BF2, BF1, BLB1, and BLB2 where the SNP% was 10.37, 9.07, 7.39, and 6.67%, respectively (Table I). In comparison, the well-conserved SNP% at the four loci of Blec2, BRD2, DMA, and DMB1 were 2.76, 2.26, 2.90, and 2.82%, respectively (Table I). The relatively high levels of diversity observed for some of the genes correlated directly with the 334 synonymous (dS) and 487 non-synonymous (dN) SNPs (Table I). The dN/dS was >1 (1.2723 to 7.0698) for Blec2, BLB1, BLB2, and BF2 (bold letters in Table I). A more intermediate dN/dS was found for BG1 (0.8784) and BF1 (0.7650). The lowest dN/dS levels were found in the BRD2, DMA, and DMB2 (< 0.1) and TAP1 (0.1452) genes. The remaining genes, Blec1, TAPBP, DMB1, and TAP2, had moderate dN/dS ratios of 0.2519 to 0.3109. When comparing the B21 haplotype that is associated with Marek’s disease resistance with the haplotypes associated with greatest susceptibility (B5, B13, B19) we found 216 SNP differences (13, 28, 29). Fifty-two of these are within the coding sequences of the 14 loci. Eighteen of these are nonsynonymous SNPs. Ten result in switches in amino acids from one class to another class (Table II). The B21 haplotype may be quite stable. The B21-like haplotype of Red Jungle Fowl (30) and the B21 haplotype from Line N used in this study differ by only eight nucleotide substitution differences and four indels.

Table I.

SNP and genetic features of the chicken MHC-B loci on 14 chicken haplotypes

| Locus | Aligned Seq. Length | Total SNP | SNP% (normalized*) | SNP in Non-CDS | SNP in CDS | Syn. SNP | Non-syn. SNP | dN | dS | dN/dS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BG1 | 5281 | 181 | 3.43 (1.53) | 125 | 56 | 16 | 40 | 0.0188 | 0.0214 | 0.8784 |

| Blec2 | 2499 | 69 | 2.76 (0.94) | 33 | 36 | 1 | 35 | 0.0206 | 0.0029 | 7.0698 |

| Blec1 | 2079 | 69 | 3.32 (0.97) | 55 | 14 | 5 | 9 | 0.0039 | 0.0125 | 0.3109 |

| BLB1 | 1367 | 101 | 7.39 (2.67) | 18 | 83 | 15 | 68 | 0.0446 | 0.0316 | 1.4116 |

| TAPBP | 3469 | 134 | 3.86 (0.99) | 90 | 44 | 25 | 19 | 0.0051 | 0.0185 | 0.2752 |

| BLB2 | 1379 | 92 | 6.67 (2.40) | 25 | 67 | 8 | 59 | 0.0375 | 0.0176 | 2.1296 |

| BRD2 | 3769 | 85 | 2.26 (0.62) | 38 | 47 | 43 | 4 | 0.0008 | 0.0253 | 0.0301 |

| DMA | 2103 | 61 | 2.90 (0.79) | 43 | 18 | 17 | 1 | 0.0002 | 0.0189 | 0.0131 |

| DMB1 | 2094 | 59 | 2.82 (0.78) | 39 | 20 | 12 | 8 | 0.0041 | 0.0162 | 0.2519 |

| DMB2 | 3004 | 107 | 3.56 (1.31) | 85 | 22 | 17 | 5 | 0.0015 | 0.0212 | 0.0684 |

| BF1 | 2051 | 186 | 9.07 (3.02) | 63 | 123 | 37 | 86 | 0.0351 | 0.0459 | 0.7650 |

| TAP1 | 4848 | 213 | 4.39 (1.24) | 138 | 75 | 52 | 23 | 0.0045 | 0.0308 | 0.1452 |

| TAP2 | 3121 | 138 | 4.42 (1.33) | 50 | 88 | 57 | 31 | 0.0072 | 0.0245 | 0.2922 |

| BF2 | 2026 | 210 | 10.37 (3.19) | 82 | 128 | 29 | 99 | 0.0407 | 0.0320 | 1.2723 |

| Total | 39090 | 1705 | 4.36 (1.56) | 884 | 821 | 334 | 487 | — | — | — |

Average pair-wise SNP%.

Table II.

Non-synonymous SNPs between Marek’s disease susceptible B5, B13, B19 and resistant B21 haplotypes

| Gene | Exon | Position* | B5 B13 B19 | B21 | Character | Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blec2 | 2 | 51 | Val | Met | Both non-polar neutral | Transmembrane |

| Blec2 | 3 | 92 | Trp | Leu | Polar neutral/Non-polar neutral | Stalk |

| TAPBP | 2 | 43 | Gly | Arg | Non-polar neutral/Basic | Signal peptide & N-terminal |

| TAPBP | 4 | 171 | Thr | Ala | Polar neutral/Non-polar neutral | Ig V |

| TAPBP | 4 | 246 | Arg | Gln | Basic/Polar neutral | Ig V |

| TAPBP | 5 | 319 | Gly | Ser | Non-polar neutral/Polar neutral | Ig C1 |

| BLB2 | 1 | 5 | Arg | Ser | Basic/Polar neutral | Signal peptide |

| DMB1 | 2 | 47 | Met | Val | Both non-polar neutral | Extracellular β1 |

| DMB1 | 2 | 75 | Val | Ile | Both non-polar neutral | Extracellular β1 |

| DMB2 | 1 | 11 | Val | Ile | Both non-polar neutral | Signal peptide |

| BF1 | 4 | 236 | Ala | Val | Both non-polar neutral | Transmembrane |

| TAP1 | 7 | 327 | Ala | Thr | Non-polar neutral/Polar neutral | Nucleotide binding |

| TAP1 | 9 | 437 | Arg | Trp | Basic/Polar neutral | Nucleotide binding |

| TAP2 | 4 | 325 | Asp | Asn | Acidic/Polar neutral | Core |

| TAP2 | 4 | 351 | His | Tyr | Basic/Polar neutral | Core |

| TAP2 | 7 | 579 | Arg | Lys | Basic/Basic | Nucleotide binding |

| BF2 | 3 | 142 | Ile | Val | Both non-polar neutral | Extracellular α3 |

| BF2 | 3 | 151 | Phe | Leu | Both non-polar neutral | Extracellular α3 |

Amino acid position in basis of B21 haplotype sequence (accession no. AB426152).

Phylogenetic analyses of haplotype DNA sequences and gene loci

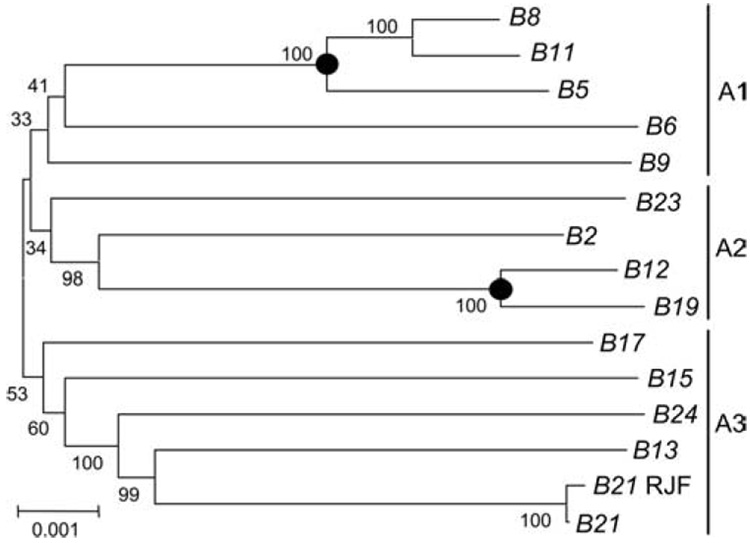

To elucidate the evolutionary history of the Mhc-B haplotypes, we constructed a phylogenetic tree using the 57,627 bp (indel free) aligned sequences for each haplotype (Fig. 5). This tree shows large genetic distances between most haplotypes. Aside from two lineages B12 and B19 and B5, B8, and B11 (marked by dots in Fig. 5), the haplotypes do not have the close phylogenetic relationships with each other as would be expected if they had evolved from a common ancestor in relatively recent times. Indeed, the phylogenetic topology revealed three ancestral lineages, A1 to A3, for the ten haplotypes. The haplotypes B8 and B11 of the Ancona breed grouped in the A1 lineage with Leghorn B5 and the haplotypes B23 and B24 of the New Hampshire breed grouped with the A2 and A3 lineages rather than in a separate lineage. The haplotypes with the greatest sequence similarities, B8, B11, and B5 in the A1 lineage and B12 and B19 in the A2 lineage, are likely to have arisen more recently.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic tree for 14 Mhc-B haplotypes derived from the 57 kb region of aligned nucleotide sequences. The tree branches are labeled with the percentage support based on 1000 bootstrap replicates. The labeled horizontal bar represents the scale of the number of nucleotide substitutions per site along the branch lengths. Homologous balanced recombination events are shown as solid circles at the relevant nodes. B21 RJF is the wild-type red jungle fowl B21 genomic sequence using accession no. AB268588 (27).

In the phylogenetic trees constructed for each gene locus, allele sharing was frequently observed across haplotypes. The number of allele-sharing loci ranged from two loci shared between haplotype B13 and other haplotypes to the 13 loci shared between the highly similar B8 and B11 haplotypes (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Fig. 1A). Allele sharing was observed at a total of 197 locations for 82 combinations (2.4 allele shared locations/combination). All haplotypes, excluding B13, had an allele shared with 12~13 other haplotypes. B13 shared only a BLB1 or DMB1 allele with four other haplotypes (Fig. 2). The alleles of the Ancona breed (B8 and B11) and New Hampshire breed (B23 and B24) were shared with the alleles of at least nine haplotypes of the White Leghorn breed, indicating their relatively close evolutionary and genetic relationships.

Phylogenetic analysis of allele sharing at each locus (Supplemental Fig. 1A) showed that the haplotype pairs B8 and B11 and B12 and B19 shared identical sequences at eleven and nine loci, respectively (Fig. 2). In addition, haplotype B5 shared the same sequences with haplotypes B8 and B11 at seven and eight loci, respectively (Fig. 2). This wide-ranging allele sharing is reflected in Fig. 2 and in the phylogenetic tree in Fig. 5. Thus, it appears that the Mhc-B haplotypes B5, B8, and B11 and the Mhc-B haplotypes B12 and B19 have stemmed from earlier ancestral haplotypes and were generated initially by homologous recombination with a breakpoint occurring between BG1 and Blec2 for B8 and B11, between BLB1 and TAPBP for B5, and between TAP1 and TAP2 in the separate lineage providing B12 and B19. The absence of identical gene alleles at the BLB2 and the BLB1 loci of the almost identical B8 and B11 haplotypes suggest that gene conversion events have occurred at these loci.

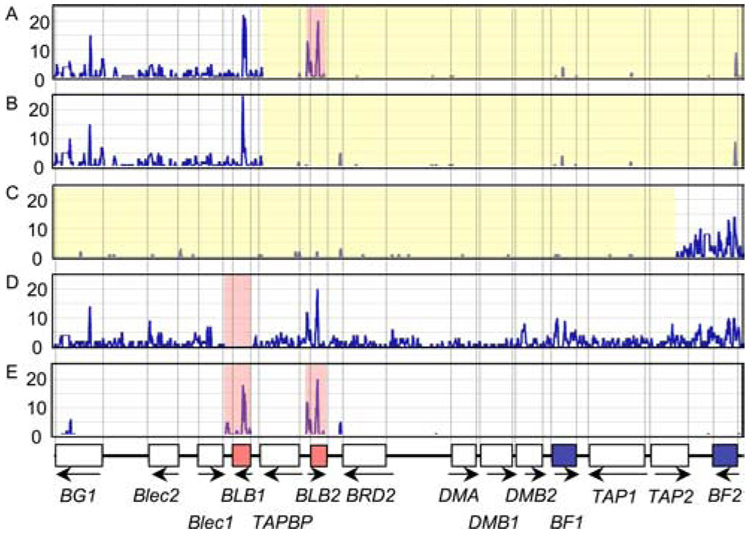

Homologous recombinations and allelic gene conversions

To examine the haplotypes for additional evidence of balanced homologous recombination (chromosomal crossing-over at meiosis) and allelic gene conversions, we constructed a total of 91 genomic diversity profiles for all of the Mhc-B haplotype combinations, and identified the locations and ranges of homologous recombinations and allelic gene conversions (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Four of these diversity profiles for the paired haplotype combinations B5 and B8, B5 and B11, B8 and B11, and B12 and B19 illustrated in Fig. 6 reveal the likelihood that homologous recombination traits (crossing over) and gene conversions or gene exchanges at various loci contribute to haplotype diversity. The SNP% for the haplotype combinations of B5 and B8 and of B5 and B11 are relatively high (1.37 to 1.38%) in the 18.2 kb segment between BG1 and BLB1 and low (0.21 to 0.07%) in the remaining 41.7 kb segment from TAPBP and to BF2. As illustrated in Fig. 6, this suggests that crossing over occurred within the 3′-end of the TAPBP gene so that the remaining portion of the B5 haplotype shares sequence with B8 and B11 throughout including the BF2 gene (Fig. 6, A and B). The SNP% for the B12 and B19 haplotype pair was 0.09% in the 54.3 kb segment between BG1 and TAP1 and 3.62% in the 5.7 kb segment between TAP2 and BF2, revealing an apparently common genomic segment extending from the BG1 gene to exon 6 of TAP2 (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

Representative pair-wise genomic diversity profiles of chicken Mhc-B haplotype sequences B5 and B8 (A), B5 and B11 (B), B12 and B19 (C), B6 and B8 (D), and B8 and B11 (E). Yellow and red backgrounds show wide-ranged allele shared regions and gene converted segments, respectively.

In addition to providing evidence of homologous recombination, 73 diversity profiles distinctly displayed evidence for a variety of allelic gene conversions traits (Supplemental Fig. 1B). These are summarized in Table III. For example, the distinct B6 and B8 haplotypes have a perfectly matched 2.6 kb segment including the BLB1 gene, but a marked diversity of 1.38 SNP% across the remaining 56.7 kb of aligned sequence (Fig. 6D). Similarly, whereas the B8 and B11 haplotypes are almost completely identical across 49.5 kb of genomic sequence (0.006 SNP%), they have markedly different gene alleles at BLB1 (2.2 kb) and BLB2 (3.2 kb) with a 2.64 SNP% and a 2.20 SNP%, respectively (Fig. 6E). These diversity profiles are consistent with gene conversion leading to the allele sharing distributions suggested by the phylogenetic analyses in Supplemental Fig. 1A.

Table III .

Two-kilobase perfectly matched whole- and partial-allelic gene conversions

| Combination of the Haplotypes | Allele Shared Length (bp) | Whole Gene Conversion Loci | Partial Gene Conversion Loci | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B2 – B5 | 2738 | DMA | DMB1 | exon 1 ~ intron 1 |

| B2 – B8 | 3255 | DMA | DMB1 | exon 1 ~ intron 1 |

| B2 – B11 | 3255 | DMA | DMB1 | exon 1 ~ intron 1 |

| B2 – B12 | 3410 | Blec1 | DMB1 | |

| 4587 | TAP2 | intron 5 ~ exon 9 | ||

| BF2 | exon 3 ~ exon 8 | |||

| B2 – B19 | 2947 | Blec1 | ||

| B5 – B6 | 2025 | BLB2 | ||

| B5 – B12 | 3142 | BRD2 | exon 1 ~ exon 7 | |

| B5 – B19 | 2267 | BRD2 | exon 1 ~ exon 5 | |

| B5 – B23 | 2010 | BLB1 | ||

| B6 – B8 | 2651 | BLB1 | ||

| B6 – B11 | 2038 | BLB2 | ||

| B8 – B9 | 2803 | BG1 | exon 1 ~ exon 9 | |

| 3474 | Blec2 | exon 4 ~ exon 5 | ||

| B8 – B12 | 2332 | BRD2 | exon 1 ~ exon 5 | |

| B8 – B19 | 2528 | BRD2 | exon 1 ~ intron 5 | |

| B8 – B21 | 2254 | BG1 | intron 1 ~ exon 9 | |

| 2057 | Blec1 | exon 1 ~ intron 3 | ||

| B9 – B11 | 2801 | BG1 | exon 1 ~ exon 9 | |

| 2947 | Blec2 | exon 4 ~ exon 6 | ||

| B9 – B21 | 2246 | BG1 | intron 1 ~ exon 9 | |

| B11 – B12 | 2332 | BRD2 | exon 1 ~ exon 5 | |

| B11 – B19 | 2528 | BRD2 | exon 1 ~ intron 5 | |

| B11 – B21 | 2395 | BG1 | intron 1 ~ intron 10 | |

| 2058 | Blec1 | exon 1 ~ intron 3 | ||

| B15 – B21 | 3295 | BF1 | ||

| B17 – B23 | 2067 | BG1 | exon 1 ~ intron 4 | |

| B23 – B24 | 2623 | BRD2 | exon 1 ~ intron 1 | |

To look further for evidence of whole or partial allelic gene conversions, we used 91 pair-wise diversity profiles (Supplemental Fig. 1B), and found perfectly matched allele shared segments of >2 kb at 32 locations (Table III). The whole-allelic gene conversions were identified for Blec1, BLB1, BLB2, DMA, and BF1 at seven locations (Table III). All these were found within in a single or across two adjacent LR-PCR amplified segments and so the boundaries of the apparent conversion events are different from those of LR-PCR amplified segments. These findings were consistent with the allele sharing distribution suggested by the phylogenetic analyses (Fig. 2, Supplemental Fig. 1A). The pair-wise diversity profiles also identified partial-allelic gene converted segments, which were not specified by the phylogenetic analyses. The partial-allelic gene conversions involved BG1, Blec2, Blec1, BRD2, DMB1 TAP2, and BF2 at a total of 22 distinct genomic positions (Table III). Evidence supports a gene conversion event in at least 13 of the 14 Mhc-B haplotypes.

Discussion

This study illustrates the distinct advantage of utilizing the Mhc-B region in the study of the Mhc function. In addition to providing the possibility of understanding the relationship between Mhc genetic polymorphism and disease associations, the small size of the Mhc-B region and its simplicity make it possible to efficiently explore Mhc sequence diversity across multiple loci in many haplotypes. The 59 kb region in this study encompasses not only the entire array of B class I and class IIβ loci, but also other genes that contribute to immune responses including TAP1 and TAP2, DMA and DMB, Blec2 (the putative NK cell receptor), Blec1 (likely an activating receptor), and BG1 (a possible inhibitory receptor). As would be expected by the polymorphic nature of Mhc class I and class II genes, sequence diversity (expressed as %SNPs and dN/dS in Table I) is biased to the regions found at or near the BLB1, BLB2, BF1, and BF2 loci supporting the likelihood of positive selection for diverse alleles. Other genes particular to the Mhc in the chicken, BG1, Blec2, and Blec1, are less polymorphic, but still contain non-synonymous SNPs providing significant dN/dS ratios and residue differences that could result in the functional capacity differences among haplotypes to support immune responses that affect disease susceptibility. Indeed, Blec2 has the highest dN/dS ratio of all 14 genes suggesting it is under strong positive selection. Genes providing the proteins required for normal assembly of peptides with Mhc class I and II (TAPBP, DMA, DMB1, DMB2, TAP1, and TAP2) and BRD2 have fewer coding region SNPs and reduced amino acid polymorphism, but nevertheless they do contain a few nonsynonymous SNPs including some that result in the incorporation of amino acids with different chemical characteristics. Since these loci may be under functional and structural constraints to limit diversity, allelic variants at these loci might, in particular, have significant functional consequences in immunity that result in differences in disease resistance. The extensive sequence data reported in this stud reveals the rich sequence diversity across Mhc-B and the need to have detailed sequence data for Mhc-B haplotypes in studies aimed at identifying genes providing disease resistance (30, 31).

Comparative analysis of the haplotype sequences has revealed several ways in which the rich sequence diversity within Mhc-B is introduced. The haplotypes of different phylogenetic ages helped greatly in resolving these different means. Haplotype diversity arises from single nucleotide mutations, indels, meiotic recombination, and gene conversion. While isolated SNPs provide evidence of diversity that is likely derived from mutational events, a large portion of Mhc-B diversity is generated by indels. Indels vary in size and appear both between and within genes. Allelic indel markers are present within the introns and exons of BG1, BLB1, DMB1, DMB2, BF1, TAP1, and TAP2 (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). Many of these are likely to have functional consequences. For example, although we did not encounter it in the B15 haplotype sequenced in this study, the largest indel that we are aware of is a 4-kb insert present in some B15 haplotypes (standard B15 haplotypes have been identified in several different populations using alloantisera in hemagglutination assays and hence B15 haplotypes from different populations may be different at the nucleotide level). The 4-kb insert is reported to disrupt the BF1*B15 locus leading to an absence of BF1*B15 at the cell surface (19).

There is also evidence that indels may be under positive selection. A series of indels found within the BG1 coding region likely gives rise to functionally distinct alleles. A number of small exons encode the coiled-coil subregion within the cytoplasmic region of BG1 proteins. The number of exons for the coiled-coil region differs between alleles. Three variant forms of BG1 that differ in the number of coiled-coil exons as illustrated in Fig. 4A. Five alleles have a single quartet of exons. Eight have two quartets. Another allele has four. Further variation in BG1 is found in two alleles that lack the penultimate exon in which sequence for an ITIM is located. These discreet allelic differences suggest that BG1 is likely under diversifying selection. Although the function of the BG1 gene product is still unknown, BG1 has been identified as a candidate gene involved in affecting the onset of Marek’s disease and tumor formation (Y. Wang, R. M. Goto and M. M. Miller, unpublished data). These differences provide substantial evidence that indels may have a role of Mhc-B in disease resistance.

Sequence diversity and phylogenetic analysis revealed that five of the fourteen haplotypes are closely related and apparently recently derived. The five haplotypes diverge through paths involving homologous recombination and gene conversion. As diagrammed in Fig. 6, haplotypes B12 and B19 are nearly entirely identical across the entire region. They differ only at the TAP2 and BF2 loci likely as the result of crossing over within the boundary of the TAP2 gene between two divergent parent haplotypes. Localization of the breakpoint within TAP2 provides evidence that minimal essential Mhc region is not a privileged site free from recombination as suggested earlier (17). Differences between B12 and B19 in Marek’s disease, if they occur, might then be related to this small subregion.

The second group of closely-related haplotypes (B5, B6, B8, and B11 in Fig. 6) provides an example of the effect of the combined forces of recombination and gene conversion. Highly similar B8 and B11 haplotypes differ from closely related B5 apparently as the result of a crossing over event that occurred with an unidentified parental haplotype providing a common subregion in B8 and B11. Secondarily, B8 and B11 apparently diverged through gene conversions taking place at the BLB loci (see Supplemental Fig. 1A). A further discrete gene conversion at BLB1 produced BLB1 identity between B8 and B6. Additional examples of whole and partial locus gene conversion (Table III) provide evidence that gene conversion is a substantial force introducing sequence diversity into Mhc-B. Evidence for gene conversion in the Mhc was previously limited to partial gene conversion events with single loci (18, 32). Gene conversion in the Mhc may influence the degree of disease association among segregating sites, interrupt linkage disequilibrium within localized regions, and generate an exchange of small tracts or an entire locus of a chromosome, creating mosaic sequences within haplotypes. Such gene conversion events are difficult to estimate from limited nucleotide sequence data. There are relatively few population genetic data sets with sufficient sequence and sample number to provide information regarding the role of gene conversion within a single locus. We overcame this difficulty by collecting informative and reliable nucleotide sequence data that is appropriate for estimating the role of gene conversion. The work was made easier by having DNA from Mhc-B homozygous chickens and by directly sequencing long tracts of orthologous sequence that was amplified by LR-PCR. Mhc-B haplotypes provide sufficient sequence polymorphism and enough genes to identify conversion tract boundaries using a sliding window method for comparison.

This work shows that chicken Mhc-B haplotypes are not as stable as previously proposed (19). Mhc haplotype diversity is generated by a variety of mutational forces. Some Mhc-B haplotypes are old, while others are apparently very recently derived. This study provides a framework for further analyses of Mhc infectious disease associations. With sufficient attention to detail it is likely that haplotypes can be selected that will allow classical genetics to define which elements within Mhc-B contribute to its significant influence in infectious disease resistance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Abplanalp, University of California Davis; W. E. Briles, Northern Illinois University, L.D. Bacon, USDA ARS ADOL, East Lansing, MI and L.W. Schierman, University of Georgia for providing DNA samples.

Footnotes

The nucleotide sequences reported in this work have been submitted to GenBank under accession nos. AB426141 to AB426154.

This work was supported by KAKENHI (Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research) on Priority Areas “Comparative Genomics” from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, the Advanced Research Project Type A, Tokyo University of Agriculture, No. 02, 2006; NIH NCI R21 CA105426; and USDA CREES NRICGP 2006-35205-16678.

Abbreviations used in this paper: LR-PCR, long-range PCR; indel, insertion and deletion; dN, nonsynonymous substitution; dS, synonymous substitution; SNP, sequence diversity.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Klein J. Antigen-major histocompatibility complex-T cell receptors: inquiries into the immunological ménage à trois. Immunol. Res. 1986;5:173–190. doi: 10.1007/BF02919199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schierman LW, Collins WM. Influence of the major histocompatibility complex on tumor regression and immunity in chickens. Poult. Sci. 1987;66:812–818. doi: 10.3382/ps.0660812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamont SJ, Bolin C, Cheville N. Genetic resistance to fowl cholera is linked to the major histocompatibility complex. Immunogenetics. 1987;25:284–289. doi: 10.1007/BF00404420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lillehoj HS, Ruff MD, Bacon LD, Lamont SJ, Jeffers TK. Genetic control of immunity to Eimeria tenella: interaction of MHC genes and non-MHC linked genes influences levels of disease susceptibility in chickens. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1989;20:135–148. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(89)90094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cotter PF, Taylor RL, Jr, Abplanalp H. B-complex associated immunity to Salmonella enteritidis challenge in congenic chickens. Poult. Sci. 1998;77:1846–1851. doi: 10.1093/ps/77.12.1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor RL., Jr Major histocompatibility (B) complex control of responses against Rous sarcomas. Poult. Sci. 2004;83:638–649. doi: 10.1093/ps/83.4.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller MM, Bacon LD, Hála K, Hunt HD, Ewald SJ, Kaufman J, Zoorob R, Briles WE. Nomenclature for the chicken major histocompatibility (B and Y) complex. Immunogenetics. 2004;56:261–279. doi: 10.1007/s00251-004-0682-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briles WE, Goto RM, Auffray C, Miller MM. A polymorphic system related to but genetically independent of the chicken major histocompatibility complex. Immunogenetics. 1993;37:408–414. doi: 10.1007/BF00222464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller MM, Goto R, Bernot A, Zoorob R, Auffray C, Bumstead N, Briles WE. Two Mhc class I and two Mhc class II genes map to the chicken Rfp-Y system outside the B complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:4397–4401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fillon V, Zoorob R, Yerle M, Auffray C, Vignal A. Mapping of the genetically independent chicken major histocompatibility complexes B and RFP-Y to the same microchromosome by two-color fluorescent in situ hybridization. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 1996;75:7–9. doi: 10.1159/000134445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller MM, Goto RM, Taylor RL, Jr, Zoorob R, Auffray C, Briles RW, Briles WE, Bloom SE. Assignment of Rfp-Y to the chicken major histocompatibility complex/NOR microchromosome and evidence for high-frequency recombination associated with the nucleolar organizer region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:3958–3962. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins WM, Briles WE, Zsigray RM, Dunlop WR, Corbett AC, Clark KK, Marks JL, McGrail TP. The B locus (MHC) in the chicken: association with the fate of RSV-induced tumors. Immunogenetics. 1977;5:333–343. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Briles WE, Stone HA, Cole RK. Marek’s disease: effects of B histocompatibility alloalleles in resistant and susceptible chicken lines. Science. 1977;195:193–195. doi: 10.1126/science.831269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Longenecker BM, Gallatin WM. Genetic control of resistance to Marek’s disease. IARC Sci. Publ. 1978;24:845–850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simonsen M, Crone M, Koch C, Hála K. The MHC haplotypes of the chicken. Immunogenetics. 1982;16:513–532. doi: 10.1007/BF00372021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hála K, Chausse AM, Bourlet Y, Lassila O, Hasler V, Auffray C. Attempt to detect recombination between B-F and B-L genes within the chicken B complex by serological typing, in vitro MLR, and RFLP analyses. Immunogenetics. 1988;28:433–438. doi: 10.1007/BF00355375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaufman J, Völk H, Wallny HJ. A “minimal essential Mhc” and an “unrecognized Mhc”: two extremes in selection for polymorphism. Immunol. Rev. 1995;143:63–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1995.tb00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunt HD, Pharr GT, Bacon LD. Molecular analysis reveals MHC class I intra-locus recombination in the chicken. Immunogenetics. 1994;40:370–375. doi: 10.1007/BF01246678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaw I, Powell TJ, Marston DA, Baker K, van Hateren A, Riegert P, Wiles MV, Milne S, Beck S, Kaufman J. Different evolutionary histories of the two classical class I genes BF1 and BF2 illustrate drift and selection within the stable MHC haplotypes of chickens. J. Immunol. 2007;178:5744–5752. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fulton JE, Juul-Madsen HR, Ashwell CM, McCarron AM, Arthur JA, O’Sullivan NP, Taylor RL., Jr Molecular genotype identification of the Gallus gallus major histocompatibility complex. Immunogenetics. 2006;58:407–421. doi: 10.1007/s00251-006-0119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Briles WE, Briles RW, Pollock DL, Pattison M. Marek’s disease resistance of B (MHC) heterozygotes in a cross of purebred Leghorn lines. Poult. Sci. 1982;61:205–211. doi: 10.3382/ps.0610205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okada I, Yamamoto Y, Mizuyama M. Parabiosis between avian embryos selected for high and low competences of the graft-versus-host reaction. Poult. Sci. 1987;66:1090–1094. doi: 10.3382/ps.0661090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shiina T, Tamiya G, Oka A, Yamagata T, Yamagata N, Kikkawa E, Goto K, Mizuki N, Watanabe K, Fukuzumi Y, et al. Nucleotide sequencing analysis of the 146-kilobase segment around the IkBL and MICA genes at the centromeric end of the HLA class I region. Genomics. 1998;47:372–382. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.5114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rozas J, Sánchez-DelBarrio JC, Messeguer X, Rozas R. DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:2496–2497. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nei M, Gojobori T. Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1986;3:418–426. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shiina T, Shimizu S, Hosomichi K, Kohara S, Watanabe S, Hanzawa K, Beck S, Kulski JK, Inoko H. Comparative genomic analysis of two avian (quail and chicken) MHC regions. J. Immunol. 2004;172:6751–6763. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.6751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Longenecker BM, Pazderka F, Gavora JS, Spencer JL, Stephens EA, Witter RL, Ruth RF. Role of the major histocompatibility complex in resistance to Marek's disease: restriction of the growth of JMV-MD tumor cells in genetically resistant birds. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1977;88:287–298. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-4169-7_27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bacon LD, Hunt HD, Cheng HH. Genetic resistance to Marek’s disease. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2001;255:121–141. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56863-3_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shiina T, Briles WE, Goto RM, Hosomichi K, Yanagiya K, Shimizu S, Inoko H, Miller MM. Extended gene map reveals tripartite motif, C-type lectin, and Ig superfamily type genes within a subregion of the chicken MHC-B affecting infectious disease. J. Immunol. 2007;178:7162–7172. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.7162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Briles WE, Briles RW, Taffs RE, Stone HA. Resistance to a malignant lymphoma in chickens is mapped to subregion of major histocompatibility (B) complex. Science. 1983;219:977–979. doi: 10.1126/science.6823560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holmes N, Parham P. Exon shuffling in vivo can generate novel HLA class I molecules. EMBO J. 1985;4:2849–2854. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb04013.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.