Abstract

Laminins are major cell-adhesive proteins in basement membranes that are capable of binding to integrins. Laminins consist of three chains (α, β, and γ), in which three laminin globular modules in the α chain and the Glu residue in the C-terminal tail of the γ chain have been shown to be prerequisites for binding to integrins. However, it remains unknown whether any part of the β chain is involved in laminin-integrin interactions. We compared the binding affinities of pairs of laminin isoforms containing the β1 or β2 chain toward a panel of laminin-binding integrins, and we found that β2 chain-containing laminins (β2-laminins) bound more avidly to α3β1 and α7X2β1 integrins than β1 chain-containing laminins (β1-laminins), whereas α6β1, α6β4, and α7X1β1 integrins did not show any preference toward β2-laminins. Because α3β1 contains the “X2-type” variable region in the α3 subunit and α6β1 and α6β4 contain the “X1-type” region in the α6 subunit, we hypothesized that only integrins containing the X2-type region were capable of discriminating between β1-laminins and β2-laminins. In support of this possibility, a putative X2-type variant of α6β1 was produced and found to bind preferentially to β2-laminins. Production of a series of swap mutants between the β1 and β2 chains revealed that the C-terminal 20 amino acids in the coiled-coil domain were responsible for the enhanced integrin binding by β2-laminins. Taken together, the results provide evidence that the C-terminal region of β chains is involved in laminin recognition by integrins and modulates the binding affinities of laminins toward X2-type integrins.

Laminins are large glycoproteins exclusively localized in basement membranes, which represent thin sheets of extracellular matrix bound by a variety of cell types, including epithelial, endothelial, muscle, and glial cells. Laminins are composed of three polypeptide chains (α, β, and γ), which assemble into a disulfide-bonded heterotrimer with a cross-shaped structure. There are five α chains (α1–α5), three β chains (β1–β3), and three γ chains (γ1–γ3) in mammals (1, 2), combinations of which give rise to at least 12 distinct isoforms expressed in tissue-specific and developmentally regulated manners (1, 3).

Laminins play pivotal roles in embryonic development. Mice deficient in expression of the γ1 chain, which is present in most laminin isoforms except for laminin-3322 and some γ3 chain-containing isoforms, fail to deposit basement membranes and die at the peri-implantation stage of embryonic development (4). Gene knockouts of other laminin chains also result in severe phenotypes. Mice deficient in the α5 chain die around embryonic day 17 because of multiple developmental abnormalities, including failure of neural tube closure and digit separation and abnormal placental, kidney, and lung morphogenesis (5–7). Mice lacking the α2 chain show adult lethality because of severe and progressive skeletal muscle degeneration (8, 9). These phenotypes can be accounted for by defects in the physical strength of basement membranes and/or the adhesive interactions of cells with basement membranes and subsequent signaling events involving the integrin family of cell adhesion receptors (6, 10).

Integrins are heterodimeric membrane proteins composed of noncovalently associated α and β subunits. To date, 24 integrin types consisting of distinct α and β subunits have been identified in mammals (11). Among these integrins, α3β1, α6β1, α6β4, and α7β1 integrins have been shown to serve as the major laminin receptors in various cell types (12, 13). Further diversity has been introduced to α7β1 integrin by the presence of two α7 subunits, α7X1 and α7X2, which differ in their extracellular β-propeller domains (12). The α7 subunit contains alternatively spliced X1 or X2 regions that are located at the surface-exposed loop connecting blades III and IV of the β-propeller domain. The X1 and X2 regions have been shown to modulate the ligand-binding specificities and affinities of α7β1 integrins. Specifically, α7X1β1 integrin binds to laminin-511 with higher affinities than to laminin-111 and -211, whereas α7X2β1 integrin binds more avidly to laminin-111 and -211 than to laminin-511 (14, 15).

Accumulating evidence indicates that three laminin globular (LG)3 domains, LG1–3, in the α chains are prerequisites for integrin binding by laminins (16, 17). However, laminin α chain monomers do not show any significant activities for binding to integrins and require heterotrimerization with β and γ chains to fully exert their activities (18, 19). Recently, we found that the C-terminal region of laminin γ chains, particularly the glutamic acid residue at the third position from the C terminus, is critically involved in laminin recognition by integrins (20). Deletion or substitution of this glutamic acid residue, which is conserved between the γ1 and γ2 chains, abrogates the integrin binding activities of laminin isoforms containing these γ chains, whereas isoforms containing the γ3 chain, whose C-terminal tail is shorter than those of the γ1 and γ2 chains and lacks the glutamic acid residue, are unable to bind to integrins (20, 21). Despite the emerging evidence for roles of the α and γ chains in integrin binding by laminins, it remains unknown whether the β chains contribute to laminin recognition by integrins.

Among the three β chains, the β1 and β2 chains exhibit ∼50% sequence homology and share the same domain structure (2, 22). Both the β1 and β2 chains form disulfide-bonded dimers with the γ1 chain and assemble with all types of α chains to yield αXβ1γ1 or αXβ2γ1 heterotrimers (23–26). Immunohistochemical analyses revealed that although the β1 and β2 chains are both ubiquitously distributed in various tissues, the β2 chain dominates at sites with specialized functions and/or unique structures, such as neuromuscular junctions and glomerular basement membranes of the kidney (27–29). Consistent with the enriched expression of the β2 chain at these sites, deficiency in the β2 chain leads to abnormal structures of neuromuscular junctions and dysfunction of glomerular basement membranes (27, 30, 31). Although little is known about the functional distinctions between laminin isoforms containing the β1 chain (referred to as “β1-laminins”) and those containing the β2 chain (referred to as “β2-laminins”), the β2-containing laminin-421 has been shown to bind to voltage-gated calcium channels, components of neuromuscular junctions, through the C-terminal 20-kDa region of the β2 chain containing the tripeptide sequence Leu-Arg-Glu, which is absent from the corresponding region of the β1 chain (32). However, it remains unexplored whether β1-laminins and β2-laminins differ in their integrin-binding specificities or affinities.

In this study, we produced pairs of β1-laminins and β2-laminins sharing the same α chains, and we compared their binding activities toward a panel of laminin-binding integrins to investigate their functional distinctions. We found that β1-laminins and β2-laminins differ in their binding affinities toward a subset of laminin-binding integrins that contain the X2 region within their α subunits. We mapped the region modulating the integrin-binding affinities to the C-terminal 20 amino acid residues of the β chains and found that the C-terminal region of the laminin β2 chain up-regulates the binding affinities toward X2 region-containing integrins.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies and Reagents—Mouse monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against the human laminin α1 (1F11 and 5A3), α2 (3F12 and 22W2), α5 (5D6 and 15H5), and γ1 (C12SW) chains were produced as described previously (16, 33). A rat mAb against the human laminin β2 chain (6A3) was produced by fusion of Sp2/0 mouse myeloma cells with spleen cells from rats immunized with recombinant laminin-221 as an immunogen. The specificity of 6A3 was determined using laminin β1 and β2 swap mutants as detailed below. A mouse mAb against the human laminin β1 chain (DG10) was purchased from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA). A mouse anti-FLAG® M2 mAb was purchased from Sigma. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated mouse anti-His5 mAb and rabbit anti-hemagglutinin (HA) tag polyclonal antibody (pAb) were obtained from Qiagen (Valencia, CA) and QED Bioscience (San Diego), respectively. A rabbit pAb against ACID/BASE coiled-coil peptides was kindly provided by Dr. Junichi Takagi (Institute for Protein Research, Osaka University, Osaka, Japan). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG was purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG was obtained from American Qualex Antibodies (San Clemente, CA). A streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate was purchased from Zymed Laboratories Inc.

Construction of Expression Vectors—Expression vectors for the human laminin α1 (pcDNA3.1-α1), α2 (pcDNA3.1-α2), α5 (pcDNA3.1-α5), β1 (pCEP4-β1), and β2 (pcDNA3.1-β2) chains were prepared as described previously (16, 21, 34). An expression vector for a FLAG-tagged laminin β2 chain was constructed by inserting the following nucleic acid sequence encoding a FLAG tag between positions 96 and 97 from the starting codon of the β2 mRNA: 5′-CAA GCA CCA ATC GAT GAT TAC AAG GAC GAC GAT GAC AAG-3′ (the FLAG tag sequence is shown with underlines). An expression vector for the human laminin γ1 chain (pSecTag2A-γ1) was generated as follows. A cDNA encoding the laminin γ1 chain (pcDNA3.1-γ1) (34) was digested with XbaI, followed by digestion with BamHI. The resulting cDNA fragment was ligated into the EcoRV-BamHI sites of pSecTag2A (Invitrogen) from which the endogenous signal peptide had been deleted.

Expression vectors for individual E8 fragments of the human laminin α1, α2, α5, β1, and γ1 chains (designated α1E8, α2E8, α5E8, β1E8, and γ1E8, respectively) were prepared as described (20, 21). His6, HA, and FLAG tags were added to the recombinant αE8 (α1E8, α2E8, and α5E8), β1E8, and γ1E8 chains, respectively. An expression vector for a truncated laminin β2 chain (designated β2E8) was prepared as follows. A cDNA encoding laminin β2E8 (Leu1573–Gln1798) was amplified by PCR using pcDNA3.1-β2 as a template, with an EcoRI site at the 3′ end, and then inserted to the EcoRV and EcoRI sites of pBluescript® KS(+) (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), which had been modified to include a cDNA segment encoding an HA tag by extension PCR. The resulting cDNA encoding HA-tagged β2E8 was recloned into pSecTag2B (Invitrogen) cleaved with KpnI and EcoRI. Expression vectors for the following swap mutants of the laminin β1 and β2 chains were prepared by overlap extension PCR using pSecTag2B-β1E8 and pSecTag2B-β2E8 as templates: Swap1, Leu1573–Gln1622 of β2 were substituted with Leu1561–Glu1610 of β1; Swap2, Leu1573–Ser1678 of β2 were substituted with Leu1561–Ser1666 of β1; Swap3, Leu1573–Ser1755 of β2 were substituted with Leu1561–Leu1743 of β1; Swap4, Leu1573–Leu1776 of β2 were substituted with Leu1561–Leu1764 of β1; Swap5, Leu1573–Thr1796 of β2 were substituted with Leu1561–Thr1784 of β1; Swap6, Glu1765–Thr1784 of β1 were substituted with Glu1777–Thr1796 of β2. Schematic structures of the chimeric mutants are depicted in Fig. 5.

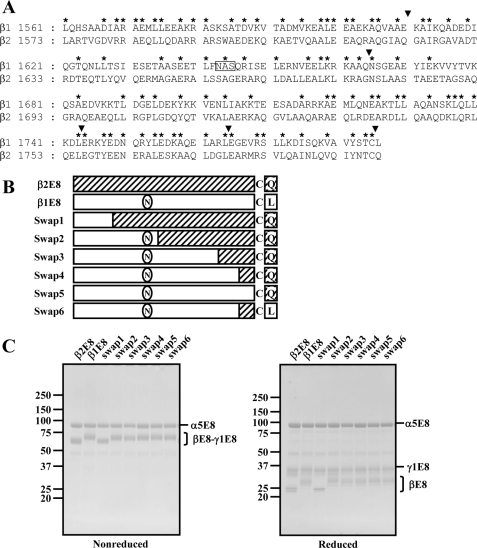

FIGURE 5.

Production of swap mutants between the laminin β1 and β2 chains. A, sequence alignment of the C-terminal regions of the human laminin β1-(1561–1786) and β2-(1573–1798) chains. The boxed amino acid sequence (Asn-Ala-Ser) is a putative N-linked glycosylation site. Conserved amino acids between the laminin β1 and β2 chains are indicated by asterisks. The boundaries between the β1 and β2 chains in the swap mutants are indicated by arrowheads. B, schematic representations of the β1/β2 swap mutants. The β1- and β2-derived sequences are represented by open boxes and hatched boxes, respectively. C, SDS-PAGE profiles of recombinant E8 fragments containing control and swapped βE8 chains were analyzed using 5–20% gradient polyacrylamide gels under nonreducing (left panel) and reducing (right panel) conditions, followed by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining. The positions of molecular size markers are shown in the left margin.

Expression vectors for truncated forms of integrin α subunits (α3, α6, α7X1, and α7X2) with an ACID peptide and a FLAG tag sequence at their C termini were prepared as described (14, 36). Expression vectors for the extracellular domains of the integrin β1 and β4 subunits with a BASE peptide and a His6 tag sequence at their C termini were kindly provided by Dr. Junichi Takagi (Institute for Protein Research, Osaka University) (37).

An expression vector for the putative X2-type variant of the human integrin α6 subunit (designated α6X2) was constructed as follows. A cDNA encoding the putative human integrin α6X2 subunit was assembled from the genomic sequence information for the exon/intron boundaries (Ensembl Transcript ID, ENST00000375221) (supplemental Fig. S1) (12, 38). The predicted amino acid sequence of integrin α6X2 is available from the UniProt Knowledgebase data bank (Swiss-Prot accession number P23229). Human genomic DNA was isolated from 293-F cells using a DNeasy® tissue kit (Qiagen). Exon 6 encoding the X2 region was amplified by PCR using the genomic DNA as a template, and the resulting cDNA was ligated to a cDNA encompassing exons 1–4 by overlap extension PCR, followed by ligation to a cDNA containing exons 7 and 8. The resulting cDNA segment encompassing nucleotides -13 to 1041 (supplemental Fig. S1) was cloned into the KpnI/AccI sites of pCR®-Blunt II-TOPO® (Invitrogen), excised with the same pair of restriction enzymes, and then ligated to KpnI/AccI-cleaved pBluescript KS(+) (Stratagene) in which an extracellular domain of the α6 integrin subunit was ligated, yielding a cDNA encoding the putative X2 variant of the integrin α6 subunit. The α6X2 cDNA was excised from pBluescript KS(+) with KpnI/NotI and ligated to KpnI/NotI-cleaved pcDNA3.1(+) that had been engineered to express the cloned cDNA as a fusion protein with a C-terminal peptide segment containing ACID and FLAG peptides in tandem. A list of the primer sequences used to construct the expression vectors in this study is available upon request.

Expression and Purification of Recombinant Proteins—Recombinant laminin-111, -211, and -511 were produced using a FreeStyle™ 293 Expression System (Invitrogen) and purified from conditioned media using immunoaffinity columns conjugated with the following mAbs (16, 21): 1F11 for laminin α1; 3F12 for laminin α2; and 5D6 for laminin α5. Recombinant laminin-121, -221, and -521 were produced using the same expression system and purified from conditioned media using anti-FLAG® M2-agarose columns (Sigma). The columns were washed with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 1 mm EDTA, and bound proteins were eluted with 100 μg/ml FLAG peptide (Sigma) and dialyzed against TBS containing 1 mm EDTA.

Recombinant integrins were produced using the FreeStyle™ 293 expression system and purified from conditioned media as previously described (14). Purified recombinant integrins were dialyzed against TBS without divalent cations.

Recombinant E8 fragments of laminin-111, -121, -211, -221, -511, and -521, and those of laminin-511/521 swap mutants were produced using the FreeStyle™ 293 expression system. The recombinant proteins were purified from conditioned media by sequential chromatography on Ni-NTA-agarose (Qiagen) and anti-FLAG® M2-agarose columns, and then dialyzed against TBS. The protein concentrations of all the recombinant products were determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard.

SDS-PAGE and Immunoblotting—SDS-PAGE was carried out according to Laemmli (39). The separated proteins were visualized by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining or transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were probed with antibodies against individual laminin chains or tag peptides, and the resulting antigen-antibody complexes were visualized using ECL Western blotting detection reagents (GE Healthcare).

Solid-phase Binding Assays—Solid-phase assays for binding of integrins with laminins and their E8 fragments were carried out as described previously (14). Briefly, 96-well microtiter plates were coated with recombinant proteins overnight at 4 °C, blocked with 1% BSA for 1 h at room temperature, and incubated with integrins for 3 h at room temperature in the presence of 1 mm MnCl2 or 10 mm EDTA. Following washes with TBS containing 0.1% BSA and 0.02% Tween 20 (buffer-W), the plates were incubated with the biotinylated pAb against ACID/BASE peptides in buffer-W containing 1 mm MnCl2 for 30 min, washed with the same buffer, and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin for 15 min. Bound antibodies were quantified by measuring the absorbance at 490 nm after incubation with o-phenylenediamine. The amounts of integrin ligands adsorbed on the plates were quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays using mAbs 1F11 (for laminin-111/121), 3F12 (for laminin-211/221), and 5D6 (for laminin-511/521) or anti-FLAG mAb (for E8 fragments) to confirm the equality of the adsorbed proteins. The apparent dissociation constants were determined as described previously (40). Statistical analyses were performed using Student's t test.

RESULTS

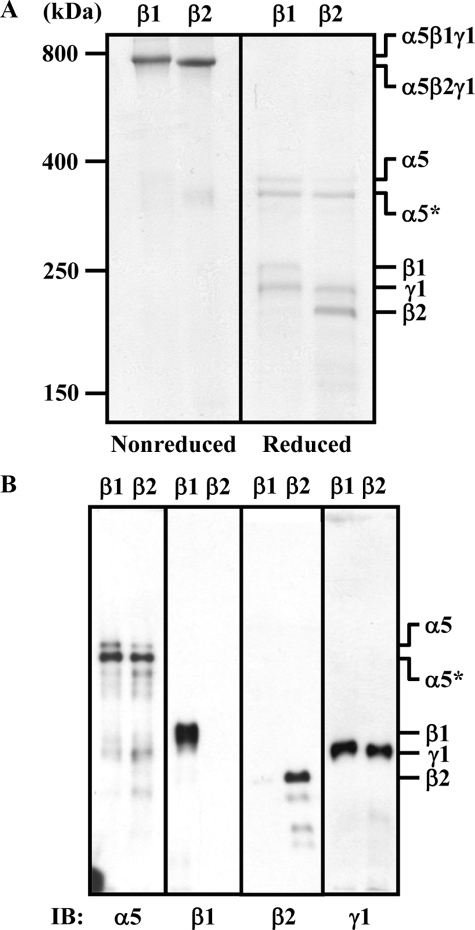

Laminin-521 Binds More Avidly to α3β1 and α7X2β1 Integrins Than Laminin-511—To investigate the potential functional distinctions between laminins containing the β1 and β2 chains in integrin binding, we produced recombinant laminin-511 and -521 by simultaneous transfection of cDNAs encoding the laminin α5/β1/γ1 and α5/β2/γ1 chains into 293-F cells, respectively, and we examined their binding activities toward a panel of laminin-binding integrins. 293-F cells expressed a small amount of the laminin β1 chain (data not shown), and the resulting laminin-521 became contaminated with laminin-511 containing the endogenously expressed β1 chain, which cannot be removed by immunoaffinity chromatography using antibodies against the α5 chain. To avoid such contaminants in β2 chain-containing laminins, a FLAG tag was fused to the N terminus of the β2 chain to facilitate purification of the recombinant laminin-521 using an anti-FLAG mAb column. The authenticities of the purified proteins were verified by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining (Fig. 1A) and immunoblotting with antibodies against individual laminin chains (Fig. 1B). Under nonreducing conditions, both laminin-511 and -521 gave high molecular weight bands migrating at similar positions to that of Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm-laminin (∼800 kDa), confirming that both laminins were purified as disulfide-bonded heterotrimers (Fig. 1A). Under reducing conditions, laminin-511 gave four bands. The two upper bands were full-length and LG4–5-deleted α5 chains (16) and the two lower bands were the β1 and γ1 chains, based on immunoblotting with antibodies against individual chains (Fig. 1, A and B). Similarly, laminin-521 also gave four bands under reducing conditions. The two upper bands were the same as those of laminin-511, and the two lower bands were the γ1 and β2 chains.

FIGURE 1.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analyses of purified laminin-511 and -521. A and B, purified laminin-511 and -521 (labeled β1 and β2, respectively) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE in 4% gels under nonreducing or reducing conditions. The separated proteins were visualized by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining (A) or transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes followed by immunoblotting (IB) with mAbs against theα5 (15H5), β1 (DG10), β2 (6A3) and, γ1 (C12SW) chains (B). The positions of molecular size markers, including nonreduced and reduced Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm-laminin (800 and 400 kDa, respectively), are shown in the left margin. The asterisk denotes the laminin α5 chain lacking LG4–5.

The purified laminin-511 and -521 were assessed for their abilities to bind to a panel of recombinant laminin-binding integrins by solid-phase binding assays (Fig. 2). The assays were performed in the presence of 1 mm Mn2+ to fully activate the integrins. Although α6β1, α6β4, and α7X1β1 integrins bound to laminin-511 and -521 equally well without any bias (Fig. 2, B–D), α3β1 and α7X2β1 integrins bound more avidly to laminin-521 than to laminin-511 (Fig. 2, A and E). The apparent dissociation constants of α3β1 integrin were 3.28 ± 0.26 nm for laminin-511 and 0.84 ± 0.14 nm for laminin-521 (Table 1), demonstrating that α3β1 integrin binds to laminin-521 with an affinity about four times higher than that for laminin-511. A similar difference in the affinities toward laminin-511 and -521 was observed for α7X2β1 integrin, although the dissociation constant for laminin-511 could not be determined because of incomplete saturation of the integrin binding activity. In contrast, α6β1 and α7X1β1 integrins did not show any differences in their dissociation constants toward laminin-511 and -521 (p = 0.78 for α6β1 and p = 0.19 for α7X1β1), as was also the case for α6β4 integrin, whose titration curves for laminin-511 and -521 overlapped with each other over the range of integrin concentrations examined (Fig. 2C). Binding of these integrins to laminin-511 and -521 was abolished in the presence of EDTA (data not shown), endorsing the specificity of the solid-phase binding assays. These results raised the possibility that laminin β chains modulate the binding affinities of laminins to some but not all laminin-binding integrins depending on the type of integrin α subunit.

FIGURE 2.

Titration curves of recombinant integrins bound to laminin-511 and -521. A–E, increasing concentrations of recombinant α3β1(A), α6β1(B), α6β4(C), α7X1β1(D), and α7X2β1(E) integrins were allowed to bind to microtiter plates coated with laminin-511 (open circles) or laminin-521 (closed circles) in the presence of 1 mm MnCl2. Bound integrins were quantified using an antibody against the ACID/BASE peptides attached to the C termini of the α and β integrin subunits. The amounts of the integrins bound in the presence of 10 mm EDTA were taken as nonspecific binding and subtracted as background. The results shown are the means of duplicate determinations. The apparent dissociation constants of the recombinant integrins are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Dissociation constants of recombinant integrins toward laminin-511/521 and their E8 fragments

|

Kda

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α3β1 | α6β1 | α6β4 | α7X1β1 | α7X2β1 | |

| nm | nm | nm | nm | nm | |

| Laminin-511 | 3.28 ± 0.26 | 0.73 ± 0.06 | NDb | 1.05 ± 0.23 | ND |

| Laminin-521 | 0.84 ± 0.14 | 0.74 ± 0.15 | ND | 0.81 ± 0.13 | 11.6 ± 1.97 |

| Laminin-511E8 | 2.96 ± 0.54 | 0.83 ± 0.02 | ND | 1.01 ± 0.16 | ND |

| Laminin-521E8 | 0.68 ± 0.08 | 0.79 ± 0.09 | ND | 0.75 ± 0.12 | 10.9 ± 2.17 |

The results are expressed as means ± S.D. of three independent experiments

Data were not determined because of only partial saturation at the highest integrin concentration examined

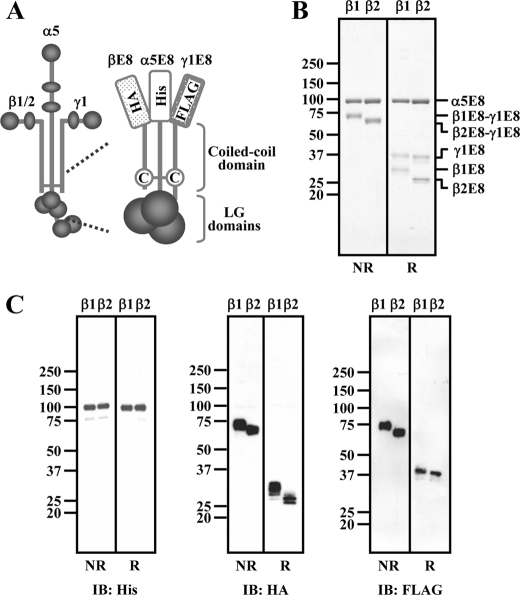

Enhanced Integrin-binding Affinities of β2 Laminins Are Reproduced by E8 Fragments—The integrin binding activities of laminins have been shown to be fully reproduced by their E8 fragments consisting of the C-terminal coiled-coil domains of the α, β, and γ chains with an extension of three LG domains in the α chain (17, 18, 20). To examine whether the distinctive integrin-binding affinities of laminin-511 and -521 could be reproduced by their E8 fragments, we generated recombinant E8 fragments of laminin-511 and -521 (designated laminin-511E8 and -521E8, respectively), which were comprised of truncated forms of the α5, β1/β2, and γ1 chains (designated α5E8, β1E8/β2E8, and γ1E8, respectively; Fig. 3A). His6, HA, and FLAG tags were engaged at the N termini of the α5E8, β1E8/β2E8, and γ1E8 chains, respectively, to facilitate purification of the resulting E8 fragments. The authenticities of the recombinant laminin-511E8 and -521E8 were verified by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3B) and subsequent immunoblotting with antibodies against individual tags (Fig. 3C). Under nonreducing conditions, two bands corresponding to α5E8 and the heterodimer of β1E8-γ1E8 or β2E8-γ1E8 were detected (Fig. 3, B and C), consistent with our previous report (20). Under reducing conditions, the recombinant E8 fragments gave three bands, each corresponding to α5E8, γ1E8, and β1E8/β2E8. The β2E8 fragment produced a band that migrated faster than the band for β1E8 because of the absence of an N-glycosylation site in β2E8 (see Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 3.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analyses of purified laminin-511E8 and -521E8. A, schematic diagrams of a full-length laminin and a recombinant E8 fragment. The cysteine (C) residues conserved in the C termini of the laminin β and γ chains are indicated. B and C, laminin-511E8 and -521E8 (labeled β1 and β2, respectively) were subjected to SDS-PAGE in 5–20% gradient polyacrylamide gels, followed by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining (B) or immunoblotting (IB) with specific antibodies against the α5E8 (anti-His5), β1E8/β2E8 (anti-HA), and γ1E8 (anti-FLAG) fragments (C) under nonreducing (NR) and reducing (R) conditions. The positions of molecular size markers are shown in the left margin.

Solid-phase integrin-binding assays with laminin-511E8 and -521E8 gave essentially the same results as those obtained with intact laminin-511 and -521. Laminin-521E8 bound more avidly to α3β1 and α7X2β1 integrins than laminin-511E8 (Fig. 4, A and E), whereas laminin-511E8 and -521E8 bound to α6β1, α6β4, and α7X1β1 integrins with almost the same affinities (Fig. 4, B–D). The dissociation constants of the laminin-binding integrins toward laminin-511E8 and -521E8 were essentially the same as those obtained with intact laminin-511 and -521 (Table 1), confirming that α3β1 and α7X2β1 integrins bind with higher affinities to laminin-521 than to laminin-511, whereas the other laminin-binding integrins do not discriminate laminin-521 from laminin-511. These results also show that the region in the laminin β chains that modulates the binding affinities for α3β1 and α7X2β1 integrins is preserved in the E8 fragments, i.e. within the C-terminal 226 amino acid residues.

FIGURE 4.

Titration curves of recombinant integrins bound to laminin-511E8 and -521E8. A–E, increasing concentrations of recombinant α3β1(A), α6β1(B), α6β4(C), α7X1β1(D), and α7X2β1(E) integrins were allowed to bind to microtiter plates coated with laminin-511E8 (open circle) and -521E8 (closed circle) in the presence of 1 mm MnCl2. The amounts of the integrins bound in the presence of 10 mm EDTA were taken as nonspecific binding and subtracted as background. The results shown are the means of duplicate determinations. Apparent dissociation constants of recombinant integrins are summarized in Table 1.

C-terminal 20 Amino Acid Residues of Laminin β Chains Modulate Integrin-binding Affinities—To define the region within the laminin β chains that modulates the integrin-binding affinities, we produced a panel of mutant E8 fragments of laminin-511/521, in which the β1 and β2 chains were differentially swapped from their N termini (Fig. 5, A and B). SDS-PAGE of the mutant E8 fragments of laminin-511/521 under nonreducing conditions gave two bands, one corresponding to the α5E8 chain and the other corresponding to the swapped βE8 chains linked to the γ1E8 chain by a disulfide bond (Fig. 5C, left panel). The relative intensities between the upper and lower bands remained unchanged among the control and mutant fragments, indicating that the heterotrimeric integrities of the mutant E8 fragments were not compromised after partial swapping between the β1 and β2 chains. The lower band of the mutant E8 fragments migrated to the identical position to the control β1E8-γ1E8 or β2E8-γ1E8 heterodimer, depending on the presence or absence of the putative N-glycosylation site (see Fig. 5, A and B). Consistent with the differences in the mobilities of the βE8-γ1E8 heterodimers under nonreducing conditions, the swapped β chains also migrated to the position of either the β1E8 or β2E8 chain under reducing conditions, depending on the presence or absence of the putative N-glycosylation site.

The binding affinities of the mutant E8 fragments to α3β1 integrin were assessed by solid-phase binding assays (Table 2). Although the E8 fragments containing the Swap1–4 chains, in which different lengths of the N-terminal region of the β2E8 chain were swapped with the corresponding regions of β1E8, exhibited no significant decreases in their integrin-binding affinities, the E8 fragment containing the Swap5 chain, in which the entire β2 chain except for the C-terminal-most Gln residue was replaced with the β1 chain, showed a significant reduction in the integrin-binding affinity, suggesting that the C-terminal 20 amino acid residues in the coiled-coil domain of the β chains were responsible for the modulation of laminin-integrin interactions by β chains. To further explore the role of the C-terminal 20 residues of the β chains, we generated Swap6, in which the C-terminal 20 residues of the β1 chain in the coiled-coil domain were swapped with the corresponding region of β2. The resulting E8 fragment containing Swap6 bound to α3β1 integrin with a similar affinity to that of the control laminin-521E8 (Kd, 0.81 ± 0.05 nm), confirming the critical role of the C-terminal 20 residues in the modulation of integrin-binding affinity by β chains. Unlike α3β1 integrin, α6β1 did not show any significant differences in its affinities toward these swap mutants of the laminin-511/521 E8 fragments irrespective of the mutations introduced (Table 2). These results support the conclusion that the C-terminal region of the β chains modulates the binding affinities of laminins toward α3β1 but not α6β1 integrin.

TABLE 2.

Dissociation constants of α3β1 and α6β1 integrins toward laminin-511E8/-521E8 containing swapped β chains

|

β chain

|

Kda

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| α3β1 | α6β1 | ||

| nm | |||

| β2E8 | 0.68 ± 0.08 | 0.83 ± 0.02 | |

| β1E8 | 2.96 ± 0.54 | 0.79 ± 0.09 | |

| Swap1 | 0.71 ± 0.04 | 0.68 ± 0.06 | |

| Swap2 | 0.75 ± 0.09 | 0.69 ± 0.06 | |

| Swap3 | 0.98 ± 0.10 | 0.71 ± 0.08 | |

| Swap4 | 0.71 ± 0.04 | 0.77 ± 0.12 | |

| Swap5 | 2.12 ± 0.39 | 0.83 ± 0.07 | |

| Swap6 | 0.81 ± 0.05 | 0.64 ± 0.16 | |

The results are expressed as means ± S.D. of three independent experiments

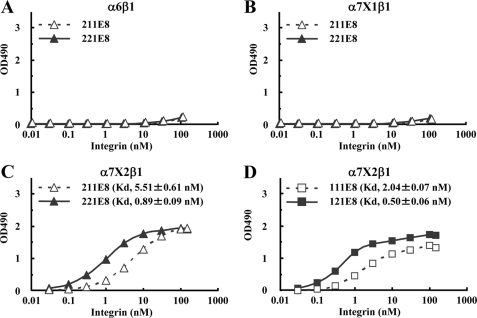

β Chains Modulate Integrin-binding Affinities of Laminin Isoforms Containing Other α Chains—Given the modulation of the integrin-binding affinities of α5 chain-containing laminins by β chains, we next examined whether the integrin binding activities of laminin isoforms containing other α chains were also modulated by β chains. We produced recombinant E8 fragments of laminin-211 and -221 (designated laminin-211E8 and -221E8, respectively) and examined their binding activities toward α6β1, α7X1β1, and α7X2β1 integrins. Although these integrins have been shown to bind to laminin-211 and -221 (14, 15), our solid-phase binding assays failed to detect any significant binding of laminin-211E8 and -221E8 to α6β1 and α7X1β1 integrins (Fig. 6, A and B). Consistent with these results, recombinant full-length laminin-211 and -221 also failed to bind to α6β1 and α7X1β1 integrins (data not shown). These apparent discrepancies may result from potential contaminations by other laminin isoforms in the laminin-211/221 used in the previous reports (see “Discussion”). On the other hand, α7X2β1 integrin was capable of binding to both laminin-211E8 and -221E8, although it bound more avidly to laminin-221E8 than to laminin-211E8, with an ∼6-fold difference in the dissociation constants (0.89 ± 0.09 nm for laminin-221E8 versus 5.51 ± 0.61 nm for laminin-211E8) (Fig. 6C), consistent with the higher affinity of α7X2β1 integrin for laminin-521 than for laminin-511. To further extend these observations to other laminin isoforms, we produced recombinant E8 fragments of laminin-111 and -121 (designated laminin-111E8 and -121E8, respectively), and we found that laminin-121E8 bound more avidly to α7X2β1 integrin than laminin-111E8 with dissociation constants of 2.04 ± 0.07 nm for laminin-111E8 and 0.50 ± 0.06 nm for laminin-121E8 (Fig. 6D). These results further support the conclusion that α7X2β1 integrin binds to β2-laminins with higher affinities than to β1-laminins, independently of the type of laminin α chain.

FIGURE 6.

Titration curves of recombinant integrins bound to laminin-111E8/121E8 and laminin-211E8/221E8. A–D, increasing concentrations of recombinant α6β1(A), α7X1β1(B), and α7X2β1(C and D) integrins were allowed to bind to microtiter plates coated with laminin-211E8 (open triangles) and -221E8 (closed triangles) (A–C) and laminin-111E8 (open squares) and -121E8 (closed squares) (D) in the presence of 1 mm MnCl2. The amounts of the integrins bound in the presence of 10 mm EDTA were taken as nonspecific binding and subtracted as background. The results shown are the means of duplicate determinations. The apparent dissociation constants are expressed as the means ± S.D. of three independent experiments.

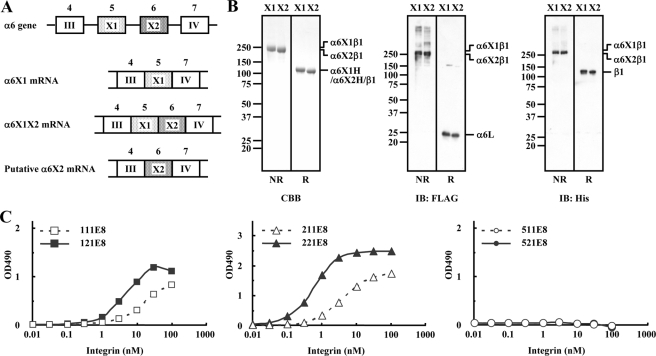

X2-type Integrins Preferentially Bind to β2-Laminins—Because the integrin α3 gene contains only the X2-like exon and has been classified into X2-type integrins along with α7X2β1 (12), we hypothesized that X2-type but not X1-type integrins might be able to discriminate between β1-laminins and β2-laminins and bind more avidly to β2-laminins than to β1-laminins. Consistent with this hypothesis, α6β1 and α6β4 integrins, which did not show any preference for β2-laminins, are classified as X1-type integrins because the major form of the integrin α6 subunit contains the X1 exon-derived sequence (12). A minor form of the integrin α6 transcript that contains both the X1 and X2 sequences has also been reported (38) (Fig. 7A), but transcripts containing only the X2 exon-derived sequence have not been found. To corroborate our hypothesis, we set out to clone the putative α6X2 cDNA by replacing the sequence encoded by the X1 exon with that of the X2 exon in the α6X1 cDNA and expressed a recombinant truncated form of α6X2β1 integrin in 293-F cells.

FIGURE 7.

Ligand-binding specificities of recombinant α6X2β1 integrin. A, schematic diagrams of the exon/intron structures of the part of the human integrin α6 gene encompassing domains 4–7 and the RNA transcripts arising from alternative splicing at the X1/X2 exons. Exons 4–7 (open boxes or dotted boxes) encode the blade III, X1, X2, and blade IV regions, respectively. B, recombinant α6X1β1 and α6X2β1 integrins (labeled X1 and X2, respectively) were subjected to SDS-PAGE in 5–20% gradient gels under nonreducing (NR) and reducing (R) conditions, followed by Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) staining (left panel) or immunoblotting with antibodies against the FLAG tag (for detection of the α6 light chain; middle panel) and His5 tag (for detection of the β1 subunit; right panel). The positions of molecular size markers are shown in the left margin. C, titration curves of recombinant α6X2β1 integrin bound to laminin-111E8/121E8, -211E8/221E8, and -511E8/521E8. Increasing concentrations of recombinant α6X2β1 integrins were allowed to bind to microtiter plates coated with laminin-111E8 (open squares), laminin-121E8 (closed squares), laminin-211E8 (open triangles), laminin-221E8 (closed triangles), laminin-511E8 (open circles), or laminin-521E8 (closed circles) in the presence of 1 mm MnCl2. The amounts of the integrins bound in the presence of 10 mm EDTA were taken as nonspecific binding and subtracted as background. The results shown are the means of duplicate determinations.

Upon SDS-PAGE, the resulting α6X2β1 integrin gave bands migrating at ∼250 kDa under nonreducing conditions and ∼150 kDa under reducing conditions, as was the case with the control α6X1β1 integrin (Fig. 7B, left panel). The authenticity of the α6X2β1 integrin was further confirmed by immunodetection of the FLAG and His6 tags added to the C termini of the α6 and β1 chains, respectively (Fig. 7B, middle and right panels). Because the integrin α6 subunit splits into heavy and light chains under reducing conditions, only the light chain derived from the C-terminal region was detected with the anti-FLAG antibody.

The laminin binding activities of the α6X2β1 integrin were assessed by solid-phase binding assays using three pairs of E8 fragments, namely laminin-111E8/121E8, -211E8/221E8, and -511E8/521E8 (Fig. 7C). Although the control α6β1 containing the X1 sequence was highly active in binding to laminin-511E8/521E8 but inactive in binding to laminin-211E8/221E8 (Figs. 4 and 6), the α6X2β1 integrin was capable of binding to laminin-211E8/221E8 but not to laminin-511E8/521E8 (Fig. 7C). Therefore, the ligand specificities of α6X2β1 differed significantly from those of α6X1β1. Nevertheless, α6X2β1 exhibited higher affinities toward β2-laminins (i.e. laminin-121E8/221E8) than toward β1-laminins (i.e. laminin-111E8/211E8), corroborating our hypothesis that X2-type integrins discriminate between β1-laminins and β2-laminins and bind to the latter isoforms with higher affinities.

DISCUSSION

Despite a number of attempts to identify the integrin recognition sites in laminins by molecular dissection using limited proteolysis, recombinant protein expression, and synthesis of an array of peptides, the mechanism by which laminins bind to integrins remained only poorly understood until recently. This situation has been in striking contrast to the interactions of collagens and Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD)-containing adhesive proteins with their integrin receptors, in which the amino acid residues that directly coordinate the divalent metal ions in the metal ion-dependent adhesion site of integrins, designated MIDAS, have been defined by x-ray crystallography (41, 42). Several lines of evidence indicate that three LG domains, LG1–3, in laminin α chains are prerequisites for the integrin binding activities of laminins (16, 36, 43, 44). However, the α chain monomers alone are functionally inactive (16–19), thereby underscoring the importance of heterotrimerization of the α chains with the β and γ chains for laminin recognition by integrins. Recently, the conserved Glu residue in the C-terminal regions of the γ1 and γ2 chains was shown to play a crucial role in laminin recognition by integrins (20), and laminin isoforms containing the γ3 chain that lacks the conserved Glu residue are unable to bind to integrins (21). Despite the accumulating evidence for roles of the α and γ chains, it has remained unknown whether the β chains also contribute to laminin recognition by integrins. In this study, we compared the binding activities of β2-laminins (i.e. laminin-121, -221, and -521) toward a panel of laminin-binding integrins with those of β1-laminins (i.e. laminin-111, -211, and -511). We found that β2-laminins were capable of binding to α3β1 and α7X2β1 integrins, both of which contain X2 exon-derived sequences, with higher affinities than β1-laminins. The other laminin-binding integrins, α6β1, α6β4, and α7X1β1, all of which contain X1 exon-derived sequences, did not exhibit any preference for β2-laminins over β1-laminins, indicating that only X2-type integrins discriminate between the β1 and β2 chains. In support of our conclusion, a constructed integrin containing an X2-type α6 subunit, α6X2β1, was capable of recognizing the difference in the β chains of laminins and bound with higher affinities to β2-laminins than to β1-laminins. We mapped the region within the laminin β chains responsible for the affinity modulation toward X2-type integrins to the C-terminal 20 amino acid residues, demonstrating that not only the C-terminal regions of the α and γ chains (i.e. the LG1–3 domains in α chains and the Glu residue in γ chains) but also the C-terminal region of the β chains are involved in laminin recognition by integrins.

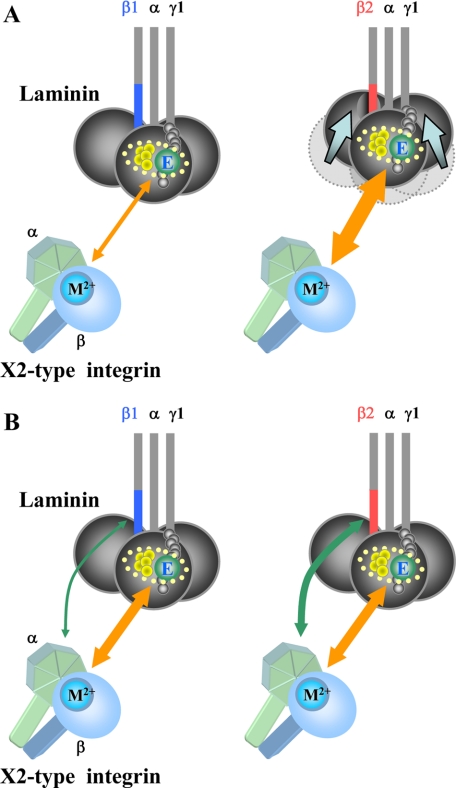

Despite the evidence for a role of the β chains in laminin recognition by integrins, the mechanism by which the β2 chain potentiates the binding affinities of laminins toward X2-type integrins remains to be elucidated. As a result, it is not clear whether the β2 chain up-regulates the binding affinities of laminins toward X2-type integrins through direct interactions with these integrins or by conformational fine-tuning of the integrin-binding sites comprising the LG1–3 domains of α chains and the Glu residue in the C-terminal region of γ chains. Based on the three-dimensional structure of the LG4–5 domains of the laminin α2 chain, Timpl et al. (45) proposed a model for the structure of the LG1–3 domains, in which the individual LG domains are arranged in a cloverleaf configuration. The integrity of the LG1–3 domains has been shown to be critical for integrin binding to laminins because substitution of any one of the three LG domains with the equivalent domains in other α chains abolished the integrin binding activities (36, 44). Because the β chains are linked to the γ chains by a disulfide bond near their C termini and form a heterotrimeric coiled-coil with the α chains, it is conceivable that the C-terminal region of the β chains is in close proximity to and potentially in direct contact with the LG1–3 domains, thereby exerting a fine-tuning effect on the active conformation of the LG1–3 domains and/or the C-terminal tail of the γ chain containing the critical Glu residue (Fig. 8A). It is interesting to note that the most C-terminal heptad repeat in the β2 chain is predicted to be less amenable to assuming coiled-coils than that in the β1 chain, based on in silico analyses using several algorithms for the prediction of coiled-coil domains (46–48). Such a distinction between the β1 and β2 chains in their abilities to assume coiled-coils may influence the integrity of the cloverleaf configuration of the LG1–3 domains and thereby modulate the integrin-binding affinities of laminins.

FIGURE 8.

Models for the mechanism by which the laminin β2 chain potentiates the binding affinity toward X2-type laminin-binding integrins. A, interaction between the C-terminal region of the β2 chain and the LG1–3 modules of the α chain fine-tunes the conformation of LG1–3, which are assembled into a cloverleaf shape, and thereby up-regulates the binding affinities of β2-laminins for X2-type laminin-binding integrins. The items encircled with dotted lines are the putative integrin-binding site comprised of the glutamic acid (E) residue in the C-terminal region of the γ1 chain (green) and undefined residues within the LG1–3 modules of the α chain (yellow), the former coordinating the divalent metal ion (M2+) in the MIDAS motif of the integrin β subunit, whereas the latter possibly interacts with the β-propeller domain of the integrin α subunit. The differences in the affinities between the putative integrin-binding site and X2-type integrins are reflected by the width of the orange two-way arrows connecting them. B, C-terminal region of the laminin β2 chain interacts directly with X2-type integrins and thereby potentiates the binding affinities of β2-laminins for X2-type laminin-binding integrins. The C-terminal region of the β1 chain may also interact with X2-type integrins with significantly lower affinities than those of the β2 chain. The width of the green two-way arrows reflects the strength of the interaction between the C-terminal region of the β chains and X2-type integrins. The orange two-way arrows refer to the interaction between the integrin and the putative integrin-binding site of laminin comprised of the LG1–3 modules of the α chain and the C-terminal tail of the γ1 chain.

The modulation of integrin-binding affinities by β chains can also be explained by a mechanism in which the C-terminal region of the β2 chain interacts directly with X2-type integrins (Fig. 8B). Recently, von der Mark et al. (15) generated homology models for the β-propeller domains of the integrin α7X1 and α7X2 subunits by molecular dynamics simulations based on the crystal structure of αvβ3 integrin. They showed that clusters of acidic residues as well as solvent-exposed hydrophobic residues within the X1 and X2 regions involved in defining the ligand-binding specificities of α7β1 integrin are located at the periphery of the β-propeller domain of the α7 subunit, distant from the I-like domain of the integrin β subunit, which is closely associated with the β-propeller domain. Given that the solvent-exposed hydrophobic residues (e.g. Tyr208 in the α7X2 subunit) are at equivalent positions to Tyr208 in the β-propeller domain of the integrin α5 subunit, which has been shown to interact with the so-called “synergy site” of fibronectin (15, 49), it is tempting to speculate that the X2 region interacts directly with laminins at the C-terminal region of the β2 chain, in a similar manner to the interaction of α5β1 integrin with the synergy site of fibronectin, thereby potentiating the binding affinities of X2-type integrins toward β2-laminins.

It is interesting to note that the proposed mechanisms by which the β chains modulate the binding affinities toward X2-type integrins are analogous to those proposed for the synergy site of fibronectin to secure the specific high affinity binding of fibronectin to α5β1 integrin. Although the RGD motif in the III-10 module is a prerequisite for fibronectin to bind to α5β1 integrin, the synergy site in the III-9 module, which is defined by the Pro-His-Ser-Arg-Asn sequence, is required for the high affinity binding of fibronectin to α5β1 integrin (50). There is evidence that the synergy site in the III-9 module modulates the conformation of the cell-binding domain, including III-10 toward α5β1 integrin (51, 52), representing an analogous scenario to our first model depicted in Fig. 8A. On the other hand, Mould et al. (49) provided evidence that the III-9 module interacts with the β-propeller domain of the integrin α5 subunit, consistent with our second model (Fig. 8B). Currently, there is no conclusive evidence available for either of the models shown in Fig. 8. However, determination of the three-dimensional structures of β2-laminins or their E8 fragments either alone or as complexes with X2-type integrins will provide definite evidence for the mechanism by which the C-terminal region of the β2 chain potentiates the interactions of β2-laminins with X2-type integrins.

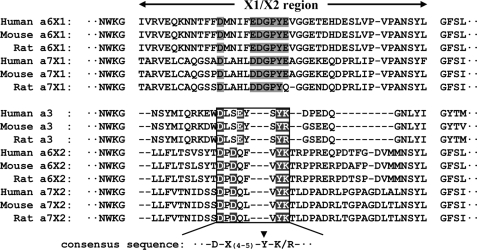

There is accumulating evidence that the X1/X2 regions define the ligand specificities of α7β1 integrins. It has been shown that α7X1β1 integrin binds more avidly to laminin-511 and -411 than to laminin-111 and -211, whereas α7X2β1 integrin binds to laminin-111 and -211/221 with higher affinities than to laminin-511 and -411 (Refs. 14, 15 and this study). Notably, the X1- and X2-type α6β1 integrins exhibited similar ligand-binding specificities to those of α7X1β1 and α7X2β1 integrins. Specifically, the α6β1 integrin containing the X1-derived sequence bound more avidly to laminin-511/521 than to laminin-111, whereas α6X2β1, a constructed α6β1 integrin containing the X2-derived sequence, was capable of binding to laminin-211/221 and -111/121 but not to laminin-511/521. Consistent with the similarities in their ligand specificities, the α6 and α7 subunits exhibit the highest sequence homology among the integrin α subunits (12). In contrast, α3β1 integrin, the third X2-type laminin-binding integrin, exhibits ligand specificities that are clearly distinct from those of α7X2β1 and α6X2β1, and it is capable of binding to laminin-511/521 with the highest affinity but incapable of binding to laminin-111/121. Multiple alignment of the X2 regions of the integrin α3, α6, and α7 subunits reveals that the X2 region of the α3 subunit is shorter than those of the α6 and α7 subunits and differs significantly in its amino acid sequence (Fig. 9). The clear distinction in the ligand specificities between α3β1 and the X2-type α6β1 and α7β1 integrins may therefore reflect, at least partially, the differences in the lengths and amino acid sequences of their X2 regions. Despite such differences, the X2 regions of the three subunits share the DX(4–5)Y(K/R) motif (15) (Fig. 9), which is not found in the X1 region of the α6 and α7 subunits. Because the tyrosine residue conserved in the consensus motif is equivalent in position to Tyr208 of the integrin α5 subunit, which has been shown to interact with the synergy site of fibronectin (15, 49), this motif may be involved in the recognition of the laminin β2 chain by X2-type integrins.

FIGURE 9.

Multiple sequence alignment of the variable regions of the integrin α3, α6, and α7 subunits. The amino acid sequences of the X1 and X2 regions of the integrin α3, α6, and α7 subunits of different vertebrate species were aligned using ClustalX (35). The highly conserved sequence in the variable region of the X2-type integrins is boxed. The consensus residues in the conserved sequence are highlighted in black. The conserved sequence in the X1 region that corresponds to the consensus sequence in the X2 region is shaded. The arrowhead indicates the tyrosine residue equivalent to Tyr208 in the integrin α5 subunit.

Our solid-phase binding assays showed that α2-containing laminins hardly bound to α6β1 and α7X1β1 integrins. These results are apparently in conflict with our previous results that these integrins are capable of binding to laminin-211/221 with moderate affinities (14). In our previous study, we extracted laminin-211/221 from human placenta with EDTA followed by purification by immunoaffinity chromatography using antibodies against the laminin α2 chain. The resulting α2 chain laminins were found to contain small amounts of other laminin isoforms, including laminin-511/521,4 which may partially override the intrinsic integrin binding activities of laminin-211/221 and thereby result in moderate binding of the placental laminin-211/221 to α6β1 and α7X1β1 integrins.

The binding of X2-type integrins to β2-laminins with higher affinities than to β1-laminins raises a question as to the physiological relevance of these findings. The laminin β2 chain has been shown to be dominantly expressed in the basement membranes of kidney glomeruli and neuromuscular junctions (26, 28, 29), where ablation of the β2 chain leads to aberrant neuromuscular junctions and dysfunction of glomerular basement membranes (27, 30). Although expression of the β1 chain was up-regulated in the basement membranes of β2 knock-out mice to compensate for the absence of the β2 chain, aberrant phenotypes persisted in the mice (27, 28), suggesting that the functions of β2-laminins cannot simply be compensated by β1-laminins (53). Consistent with the expression patterns of β2-laminins in the kidney glomeruli, podocytes and mesangial cells express α3β1 integrin, one of the X2-type integrins, as their major laminin-binding integrin for adherence to glomerular basement membranes (10, 54). In neuromuscular junctions, α7β1 is the major integrin type (55), although it remains unclear which type of α7 subunit, α7X1 or α7X2, is expressed in the cells at these junctions. Because the α7X2 subunit is the major integrin α subunit expressed in adult skeletal muscle (12), it seems likely that α7X2β1 will be mainly expressed in cells at neuromuscular junctions. Given the close association of the expression of X2-type integrins with cells adhering to basement membranes dominated by β2-laminins, the high affinity interactions between X2-type integrins and β2-laminins may contribute to the maintenance of the structural and/or functional integrities of the junctions between apposed cells, where the deficiency of β2-laminins cannot be compensated for by up-regulation of β1-laminins.

In conclusion, we have provided evidence that β2-laminins bind with higher affinities to X2-type integrins than β1-laminins, whereas β1-laminins and β2-laminins bind to X1-type integrins with similar affinities. The region responsible for the enhanced binding of β2-laminins to X2-type integrins has been mapped to the C-terminal 20 amino acid residues of the β2 chain, highlighting the auxiliary role of the C-terminal region of the β chains in the modulation of the integrin-binding affinities of laminins. The fact that the regions critically involved in integrin binding are all localized at the interface between the heterotrimeric coiled-coil domains and the LG1–3 modules led us to propose two alternative models for the β chain-dependent modulation of laminin-integrin interactions, wherein integrins recognize multiple sites at the interface, including the Glu residue in the C-terminal tail of the γ chains, the ill-defined residues within the LG1–3 modules and the C-terminal 20 amino acid residues of the β chains, although it remains to be explored whether the C-terminal residues of the β chains interact directly with integrins. Further studies, including the determination of the three-dimensional structures of laminins and their E8 fragments, are awaited to better understand the mechanistic basis of the recognition of laminins in basement membranes by integrins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Junichi Takagi for providing the recombinant β1 and β4 integrin expression vectors and anti-ACID/BASE polyclonal antibody. We also thank Dr. Naoko Norioka-Yabumoto for amino acid sequence analyses, and Chisei Shimono, Yoshiko Katsura-Ishizuka, and Yoshiko Yagi for their assistance in the expression and purification of recombinant laminins. We are grateful to Drs. Shaoliang Li and Hironobu Fujiwara for valuable discussions throughout the study.

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-aid for Scientific Research 17082005 and 20370046 (to K. S.) and Research Contract 06001294-0 with the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization of Japan. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. 1.

Footnotes

A new nomenclature for laminin isoforms (56) has been used throughout this paper as follows: laminin-111, laminin-α1β1γ1 (also designated laminin-1); laminin-211, laminin-α2β1γ1 (also designated laminin-2); laminin-121, laminin-α1β2γ1 (also designated laminin-3); laminin-221, laminin-α2β2γ1 (also designated laminin-4); laminin-332, laminin-α3β3γ2 (also designated laminin-5); laminin-421, laminin-α4β2γ1 (also designated laminin-9); laminin-511, laminin-α5β1γ1 (also designated laminin-10); laminin-521, laminin-α5β2γ1 (also designated laminin-11).

The abbreviations used are: LG, laminin globular; BSA, bovine serum albumin; HA, hemagglutinin; mAb, monoclonal antibody; pAb, polyclonal antibody; TBS, Tris-buffered saline.

Y. Taniguchi, unpublished data.

References

- 1.Tunggal, P., Smyth, N., Paulsson, M., and Ott, M. C. (2000) Microsc. Res. Tech. 51 214-227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colognato, H., and Yurchenco, P. D. (2000) Dev. Dyn. 218 213-234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miner, J. H., and Yurchenco, P. D. (2004) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20 255-284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smyth, N., Vatansever, H. S., Murray, P., Meyer, M., Frie, C., Paulsson, M., and Edgar, D. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 144 151-160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miner, J. H., Cunningham, J., and Sanes, J. R. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 143 1713-1723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen, N. M., Kelley, D. G., Schlueter, J. A., Meyer, M. J., Senior, R. M., and Miner, J. H. (2005) Dev. Biol. 282 111-125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miner, J. H., and Li, C. (2000) Dev. Biol. 217 278-289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyagoe, Y., Hanaoka, K., Nonaka, I., Hayasaka, M., Nabeshima, Y., Arahata, K., and Takeda, S. (1997) FEBS Lett. 415 33-39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuang, W., Xu, H., Vachon, P. H., and Engvall, E. (1998) Exp. Cell Res. 241 117-125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kikkawa, Y., Virtanen, I., and Miner, J. H. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 161 187-196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Humphries, M. J. (2002) Arthritis Res. 4 S69-S78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ziober, B. L., Vu, M. P., Waleh, N., Crawford, J., Lin, C. S., and Kramer, R. H. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268 26773-26783 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belkin, A. M., and Stepp, M. A. (2000) Microsc. Res. Tech. 51 280-301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishiuchi, R., Takagi, J., Hayashi, M., Ido, H., Yagi, Y., Sanzen, N., Tsuji, T., Yamada, M., and Sekiguchi, K. (2006) Matrix Biol. 25 189-197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von der Mark, H., Poschl, E., Lanig, H., Sasaki, T., Deutzman, R., and von der Mark, K. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 371 1188-1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ido, H., Harada, K., Futaki, S., Hayashi, Y., Nishiuchi, R., Natsuka, Y., Li, S., Wada, Y., Combs, A. C., Ervasti, J. M., and Sekiguchi, K. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 10946-10954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunneken, K., Pohlentz, G., Schmidt-Hederich, A., Odenthal, U., Smyth, N., Peter-Katalinic, J., Bruckner, P., and Eble, J. A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 5184-5193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deutzmann, R., Aumailley, M., Wiedemann, H., Pysny, W., Timpl, R., and Edgar, D. (1990) Eur. J. Biochem. 191 513-522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sung, U., O'Rear, J. J., and Yurchenco, P. D. (1993) J. Cell Biol. 123 1255-1268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ido, H., Nakamura, A., Kobayashi, R., Ito, S., Li, S., Futaki, S., and Sekiguchi, K. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 11144-11154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ido, H., Ito, S., Taniguchi, Y., Hayashi, M., Sato-Nishiuchi, R., Sanzen, N., Hayashi, Y., Futaki, S., and Sekiguchi, K. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 28149-28157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunter, D. D., Shah, V., Merlie, J. P., and Sanes, J. R. (1989) Nature 338 229-234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Champliaud, M. F., Virtanen, I., Tiger, C. F., Korhonen, M., Burgeson, R., and Gullberg, D. (2000) Exp. Cell Res. 259 326-335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown, J. C., Wiedemann, H., and Timpl, R. (1994) J. Cell Sci. 107 329-338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Champliaud, M. F., Lunstrum, G. P., Rousselle, P., Nishiyama, T., Keene, D. R., and Burgeson, R. E. (1996) J. Cell Biol. 132 1189-1198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miner, J. H., Patton, B. L., Lentz, S. I., Gilbert, D. J., Snider, W. D., Jenkins, N. A., Copeland, N. G., and Sanes, J. R. (1997) J. Cell Biol. 137 685-701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noakes, P. G., Miner, J. H., Gautam, M., Cunningham, J. M., Sanes, J. R., and Merlie, J. P. (1995) Nat. Genet. 10 400-406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patton, B. L., Miner, J. H., Chiu, A. Y., and Sanes, J. R. (1997) J. Cell Biol. 139 1507-1521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sasaki, T., Mann, K., Miner, J. H., Miosge, N., and Timpl, R. (2002) Eur. J. Biochem. 269 431-442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noakes, P. G., Gautam, M., Mudd, J., Sanes, J. R., and Merlie, J. P. (1995) Nature 374 258-262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zenker, M., Aigner, T., Wendler, O., Tralau, T., Muntefering, H., Fenski, R., Pitz, S., Schumacher, V., Royer-Pokora, B., Wuhl, E., Cochat, P., Bouvier, R., Kraus, C., Mark, K., Madlon, H., Dotsch, J., Rascher, W., Maruniak-Chudek, I., Lennert, T., Neumann, L. M., and Reis, A. (2004) Hum. Mol. Genet. 13 2625-2632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nishimune, H., Sanes, J. R., and Carlson, S. S. (2004) Nature 432 580-587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fujiwara, H., Kikkawa, Y., Sanzen, N., and Sekiguchi, K. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 17550-17558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayashi, Y., Kim, K. H., Fujiwara, H., Shimono, C., Yamashita, M., Sanzen, N., Futaki, S., and Sekiguchi, K. (2002) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 299 498-504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson, J. D., Gibson, T. J., Plewniak, F., Jeanmougin, F., and Higgins, D. G. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res. 25 4876-4882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ido, H., Harada, K., Yagi, Y., and Sekiguchi, K. (2006) Matrix Biol. 25 112-117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takagi, J., Erickson, H. P., and Springer, T. A. (2001) Nat. Struct. Biol. 8 412-416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delwel, G. O., Kuikman, I., and Sonnenberg, A. (1995) Cell Adhes. Commun. 3 143-161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laemmli, U. K. (1970) Nature 227 680-685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishiuchi, R., Murayama, O., Fujiwara, H., Gu, J., Kawakami, T., Aimoto, S., Wada, Y., and Sekiguchi, K. (2003) J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 134 497-504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emsley, J., Knight, C. G., Farndale, R. W., Barnes, M. J., and Liddington, R. C. (2000) Cell 101 47-56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiong, J. P., Stehle, T., Zhang, R., Joachimiak, A., Frech, M., Goodman, S. L., and Arnaout, M. A. (2002) Science 296 151-155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hirosaki, T., Mizushima, H., Tsubota, Y., Moriyama, K., and Miyazaki, K. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 22495-22502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kikkawa, Y., Sasaki, T., Nguyen, M. T., Nomizu, M., Mitaka, T., and Miner, J. H. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 14853-14860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Timpl, R., Tisi, D., Talts, J. F., Andac, Z., Sasaki, T., and Hohenester, E. (2000) Matrix Biol. 19 309-317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lupas, A., Van Dyke, M., and Stock, J. (1991) Science 252 1162-1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolf, E., Kim, P. S., and Berger, B. (1997) Protein Sci. 6 1179-1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Delorenzi, M., and Speed, T. (2002) Bioinformatics (Oxf.) 18 617-625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mould, A. P., Symonds, E. J., Buckley, P. A., Grossmann, J. G., McEwan, P. A., Barton, S. J., Askari, J. A., Craig, S. E., Bella, J., and Humphries, M. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 39993-39999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aota, S., Nomizu, M., and Yamada, K. M. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269 24756-24761 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Altroff, H., Choulier, L., and Mardon, H. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 491-497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takagi, J., Strokovich, K., Springer, T. A., and Walz, T. (2003) EMBO J. 22 4607-4615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miner, J. H., Go, G., Cunningham, J., Patton, B. L., and Jarad, G. (2006) Development (Camb.) 133 967-975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sterk, L. M., de Melker, A. A., Kramer, D., Kuikman, I., Chand, A., Claessen, N., Weening, J. J., and Sonnenberg, A. (1998) Cell Adhes. Commun. 5 177-192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martin, P. T., Kaufman, S. J., Kramer, R. H., and Sanes, J. R. (1996) Dev. Biol. 174 125-139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aumailley, M., Bruckner-Tuderman, L., Carter, W. G., Deutzmann, R., Edgar, D., Ekblom, P., Engel, J., Engvall, E., Hohenester, E., Jones, J. C., Kleinman, H. K., Marinkovich, M. P., Martin, G. R., Mayer, U., Meneguzzi, G., Miner, J. H., Miyazaki, K., Patarroyo, M., Paulsson, M., Quaranta, V., Sanes, J. R., Sasaki, T., Sekiguchi, K., Sorokin, L. M., Talts, J. F., Tryggvason, K., Uitto, J., Virtanen, I., von der Mark, K., Wewer, U. M., Yamada, Y., and Yurchenco, P. D. (2005) Matrix Biol. 24 326-332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.