Abstract

General anesthetics, once thought to exert their effects through non-specific membrane effects, have highly specific ion channel targets that can silence neuronal populations in the nervous system, thereby causing unconsciousness and immobility, characteristic of general anesthesia. Inhibitory GABAA receptors (GABAARs), particularly highly GABA-sensitive extrasynaptic receptor subtypes that give rise to sustained inhibitory currents, are uniquely sensititive to GABAAR-active anesthetics. A prominent population of extrasynaptic GABAARs is made up of α4, β2 or β3, and δ subunits. Considering the demonstrated importance of GABA receptor β3 subunits for in vivo anesthetic effects of etomidate and propofol, we decided to investigate the effects of GABA anesthetics on ”extrasynaptic” α4β3δ and also binary α4β3 receptors expressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells. Consistent with previous work on similar receptor subtypes we show that maximal GABA currents through “extrasynaptic” α4β3δ receptors, receptors defined by sensitivity to EtOH (30 mM) and the β-carboline β-CCE (1 µM), are enhanced by the GABAAR-active anesthetics etomidate propofol, and the neurosteroid anesthetic THDOC. Furthermore, we show that receptors formed by α4β3 subunits alone also show high GABA sensitivity and that saturating GABA responses of α4β3 receptors are increased to the same extent by etomidate, propofol, and THDOC as are α4β3δ receptors. Therefore, both α4β3 and α4β3δ receptors show low GABA efficacy, and GABA is also a partial agonist on certain binary αβ receptor subtypes. Increasing GABA efficacy on α4/6β3δ and α4β3 receptors is likely to make an important contribution to the anesthetic effects of etomidate, propofol and the neurosteroid THDOC.

Keywords: tonic inhibition, delta subunit, etomidate, propofol, anesthesia, neurosteroid THDOC, alcohol

Introduction

Synaptic GABAA receptors contain γ subunits (with the γ2 subunit being the most abundant subtype) and are thought to be located to synapses through interactions with accessory proteins like GABARAP (Wang et al., 1999) and gephryin (Kneussel and Betz, 2000). This implies that GABAA receptors without γ subunits are found outside of synapses. The presence of a γ subunit also makes GABAARs less sensitive to GABA, when compared to their matching αβ counterparts (Baburin et al., 2008). Therefore, it is thought that activation of most γ subunit-containing “synaptic” GABAARs require relatively high GABA concentrations supplied by classical synaptic vesicular GABAergic neurotransmission. Given the relatively low GABA-sensitivity of γ subunit-containing receptors it seems likely that γ subunit-containing receptors are usually inactive at the low ambient “extrasynaptic” concentrations of GABA (≤ 1 µM) that are determined largely by the activity of GABA transporters (Wu et al., 2007). Tonic currents mediated by α5-subunit-containing GABAARs in CA1 hippocampal pyramidal neurons might be an exception (Glykys et al., 2008), as they have been proposed to be composed of α5β3γ2 subunits (Caraiscos et al., 2004).

Certain GABAAR subtypes such as those containing δ subunits are excluded from synapses and show an extrasynaptic or perisynaptic localization (Farrant and Nusser, 2005). In contrast to the effects of γ2 subunits, incorporation of δ subunits into functional receptors is believed to increase GABA potency (EC50 < 1 µM) when compared to matching αβ GABAARs. This high GABA potency allows δ subunit-containing receptors to open at low ambient GABA concentrations, a feature that (together with slow desensitization) makes δ subunit-containing receptors uniquely suited to mediate a constant (tonic) inhibitory activity that can potently suppress neuronal excitation. The importance of ambient GABA levels and tonic GABA currents in the control of normal and pathological neuronal activity (Richerson, 2004) as well as the finding that extrasynaptic GABAARs are important mediators of alcohol (Hanchar et al., 2005; Wallner et al., 2006a) and gaboxadol (Chandra et al., 2006) actions, makes it likely that extrasynaptic receptors play an important role in controlling neuronal excitability even in the absence of exogenous modulators. In addition, many medications that are used to control hyperexcitability phenomena like convulsions, epilepsy, and tremor directly or indirectly (e.g., by increasing extrasynaptic GABA) augment tonic inhibition (Richerson, 2004).

It has been shown in neurons in slices that tonic GABA currents mediated by δ subunit-containing receptors are distinguished from their synaptic counterparts by several pharmacological features: 1) they are enhanced by nanomolar concentrations of the neurosteroid THDOC (Stell et al., 2003); 2) they are enhanced by ethanol at low inebriating (3–30 mM) concentrations (Hanchar et al., 2005; Wei et al., 2004); and 3) they are activated by high nanomolar concentrations of the GABA-analog THIP/Gaboxadol (Chandra et al., 2006; Cope et al., 2005). Given that THDOC, ethanol, and THIP have anesthetic-like actions (lead to “loss of righting reflex” in rodents at appropriate doses), the high potency and efficacy of these drugs on δ subunit-containing receptors suggests that δ subunit-containing receptors can mediate functional effects of GABAAR-active anesthetics. In addition, while δ subunit-containing receptors are uniquely sensitive to GABA, it has been shown in a number of studies on recombinant δ subunit-containing receptors that etomidate, propofol, THDOC and barbiturates lead to increases in peak currents even at saturating GABA concentrations (Bianchi and Macdonald, 2003; Feng et al., 2004; Wallner et al., 2003; Wohlfarth et al., 2002; Zheleznova et al., 2008). This indicates that δ subunit-containing receptor subtypes, while showing high potency for GABA, have a low GABA efficacy, likely because of inefficient coupling of GABA binding to pore opening. In other words, GABA can be considered a partial agonist on these low efficacy GABAAR subtypes (Bianchi and Macdonald, 2003; Wallner et al., 2003). The low GABA efficacy on δ subunit-containing receptors seen in recombinant systems (particularly with α1 subunits and in the oocyte expression system) explains some of the difficulty in expressing these receptors in recombinant systems, with one recent report stating that α1β2δ receptors expressed in oocytes are essentially silent receptors which can be “recruited” by tracazolate and the neurosteroid THDOC (Zheleznova et al., 2008).

Besides δ subunit-containing receptors, there is evidence for additional GABAAR subtypes formed by receptors composed of binary αβ combinations without δ, γ, or ε subunits in the pentamer. Particularly interesting in this respect are biochemical data showing that only 7% of α4 subunits are associated with δ subunits, whereas around 50% of α4 subunit-containing receptors do not contain γ or δ subunits (Bencsits et al., 1999). It seems likely that the majority of these α4 subunit-containing receptors without γ or δ subunits are composed of α4 and β subunits alone (Bencsits et al., 1999). Such binary, αβ receptor subtypes also have been proposed to be present in cultured hippocampal neurons where they mediate certain forms of tonic inhibition (Mortensen and Smart, 2006) and it seems likely that most of the GABA response recorded from neurons derived from γ2 subunit knock-out mice is mediated by αβ receptor subtypes (Günther et al., 1995).

GABA receptors containing β3 subunits are important mediators of etomidate and propofol anesthetic effects in vivo, because it has been shown that mice with the knock-in point mutation β3N265M lack the immobilizing effects of etomidate and propofol in response to painful stimuli (Jurd et al., 2003). In contrast, a similar knock-in point mutation at the homologous position in the β2 subunit that drastically reduces etomidate effects in β2 subunit-containing receptors (β2N265S, a change in β2 to the residue present in the “etomidate-insensitive’ β1 subunit (Belelli et al., 1997)), reduces the sedative but not the immobilizing and hypnotic etomidate effects (Reynolds et al., 2003). One factor that may account for the importance of β3 subunit-containing receptors in meditating anesthetic actions is the association of β3 subunits with extrasynaptic receptors, a finding supported by the correlation of alcohol sensitivity of β3 subunit-containing receptors in recombinant systems (Wallner et al., 2003) with alcohol sensitivity of native tonic δ-receptor-mediated GABA currents (Hanchar et al., 2005; Wei et al., 2004). Another factor may be that β3 subunit-containing GABAAR subtypes could be key components in specific neuronal circuits that are particularly important in mediating anesthetic actions (Grasshoff et al., 2006).

Here we compare receptors formed by α4β3 subunits alone with those formed by α4β3δ subunits. We find that α4β3 receptors show only slightly lower GABA sensitivity when compared to α4β3δ receptors (α4β3 GABA EC50 = 1.1 µM, α4β3δ GABA EC50 = 0.5 µM), a finding consistent with the notion that binary α4β3 receptors present in native neurons could mediate unique forms of tonic inhibition. Further we show that peak GABA responses, not only on α4β3δ, but also on binary α4β3δ receptors are enhanced by GABAAR-active anesthetics etomidate, propofol, and THDOC. Thus, the suggestion that these anesthetics act by increasing GABA efficacy can be extended to include binary α4β3 receptors and possibly other “binary” αβ GABAAR subtypes. Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that binary αβ receptors could contribute not only to tonic GABA currents, but that such receptors could potentially make important contributions to the actions of GABAAR-active anesthetics.

Results

α4β3 and α4β3δ receptors expressed in HEK cells are sensitive low “extrasynaptic” [GABA]

GABAARs composed only with α and β subunits may exist on native neurons and are readily expressed in recombinant systems; indeed evidence suggest that they are often a contaminating species when γ2, δ or ε subunit-containing receptors are the desired subject of study (Baburin et al., 2008; Olsen et al., 2007). Most native δ subunit-containing GABAARs are composed with α4 or α6, and either β2 or β3 subunits. Considering that β3 has been implicated as important for anesthetic actions and low dose ethanol sensitivity, we decided to compare the GABA sensitivity and modulation by GABA anesthetics of α4β3 and α4β3δ GABAARs.

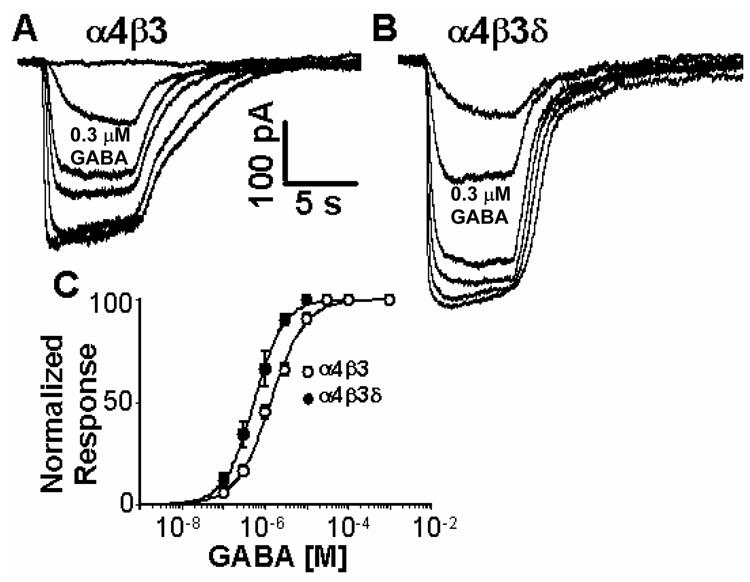

Figure 1 shows that receptors formed by α4β3δ subunits in HEK cells are half-maximally activated at a GABA concentration of ~500 nM, an EC50 only slightly higher than our previous (lower) estimate (~ 200 nM) of extrasynaptic [GABA] in cerebellar granule cells in perfused slices (Santhakumar et al., 2006). Binary α4β3 receptors also respond to low GABA concentrations, although slightly less potently (EC50 =1.1 µM, 300 nM is GABA ~EC20 at binary α4β3 receptors). This small, yet highly significant shift in GABA-sensitivity indicates that δ subunit expression indeed leads to increased GABA-sensitivity and this is opposite to the reduced GABA sensitivity generally observed with γ subunit incorporation.

Fig. 1. Expression of the δ subunit with α4 and β3 leads to increased GABA-sensitivity.

A,B) Representative recordings showing GABA dose response data from cells transfected with (A) α4β3 and (B) α4β3δ receptors. GABA concentrations of 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10 and 30 µM were applied. The 0.3 µM GABA responses are marked below the traces; C) Average GABA dose response curve of α4β3δ and α4β3 receptors. GABA EC50 values ± SD are, α4β3 = 1.3 ± 0.1 µM (n=8), for α4β3δ EC50 = 0.53 ± 0.02 µM (n=6). The GABA sensitivities of receptors made from α4β3 and α4β3δ subunits are significantly different (p<0.01).

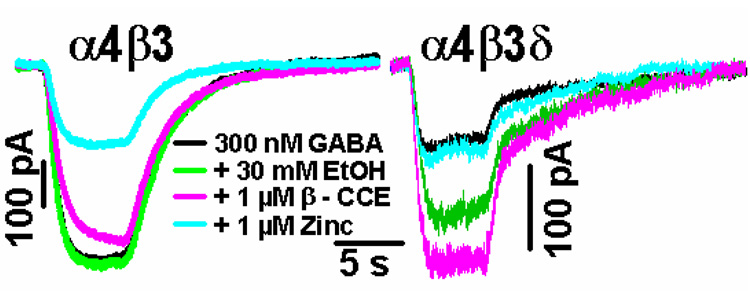

We showed previously with recombinant expression in oocytes that expression of the δ subunit makes α4β3δ and α6β3δ receptors sensitive to inebriating (3–30 mM) concentrations of ethanol, whereas α4β3 receptors are insensitive to EtOH at these same low concentrations (Hanchar et al., 2005; Wallner et al., 2003). We therefore investigated in α4β3δ-transfected HEK cells if GABA responses are ethanol sensitive. Figure 2 show representative recordings from α4β3δ– and α4β3-transfected cells in which various pharmacological features (sensitivity to 30 mM ethanol, 1 µM β-CCE, and 1 µM Zn2+, co-applied with GABA) were tested. As shown, currents evoked by application of 300 nM GABA from α4β3δ-transfected cells are enhanced by 30 mM EtOH and by 1 µM of the β-carboline β-CCE, whereas 300 nM GABA responses in all α4β3-transfected cells were insensitive to 30 mM EtOH and 1 µM β-CCE. Furthermore, 1 µM Zn2+ led to a significant (~70%) inhibition of GABA currents in α4β3 receptors, whereas EtOH- and β-CCE-sensitive 300 nM GABA responses measured in α4β3δ transfected cells were not inhibited by 1 µM Zn2+.

Fig. 2. Expression of the δ subunit with α4β3 confers sensitivity to 30 mM EtOH, 1 µM β-CCE and insensitivity to 1 µM Zn2+.

Shown are representative recordings from three (α4β3) or four (α4β3δ) similar recordings. To evoke currents, 300 nM GABA was applied, either alone (black trace), with 30 mM EtOH (green trace), with 1 µM β-CCE (pink), or with 1 µM Zn2+ (light blue).

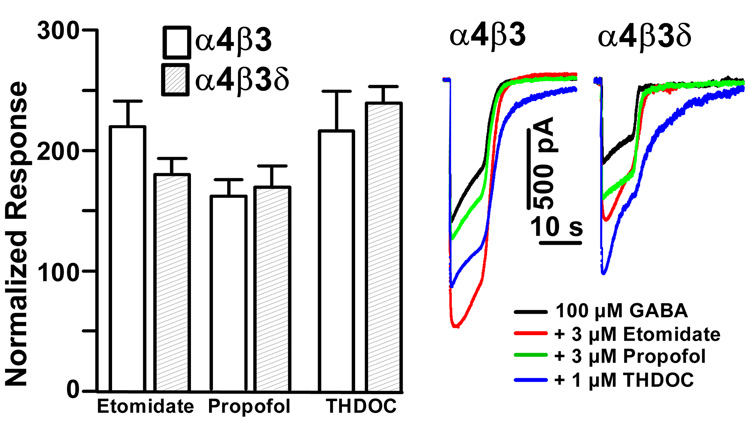

Given the observation that δ subunit-containing receptors in recombinant expression show low GABA efficacy, we decided to test the hypothesis that incorporation of the δ subunit confers low GABA efficacy and that this in turn allows for hypnotic/anesthetic modulator-induced increases in GABA efficacy. To test for increases in GABA efficacy by anesthetics we evoked GABA responses with a saturating (100 µM) GABA concentration alone, or with 100 µM GABA co-applied with either 3 µM etomidate, 3 µM propofol, or 1 µM THDOC. The concentrations of etomidate, propofol, and THDOC were chosen to match frequently used concentrations applied to expressed α1β3δ, α6β3δ and α1β2γ2 receptors (Bianchi et al., 2002; Bianchi and Macdonald, 2003; Feng and Macdonald, 2004; Rusch et al., 2004; Wallner et al., 2003; Wohlfarth et al., 2002) and tonic GABA currents (Herd et al., 2008). Figure 3 shows that, as expected from previous work on α1- and α6 subunit-containing receptors, co-application of anesthetics indeed leads to a significant enhancement of α4β3δ receptors. However, to our surprise, etomidate, propofol, and THDOC also increased peak current responses in α4β3 receptors, with no significant difference in the amount of peak current enhancement when compared to α4β3δ receptor currents (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Both α4β3 and α4β3δ receptors are enhanced by the anesthetics THDOC, etomidate and propofol at saturating (100 µM) GABA concentrations.

A bar graph summarizing the mean enhancement relative to control for 3 µM etomidate, 3 µM propofol and 1 µM THDOC. Open bars show effects on α4β3 (n=9 for etomidate and propofol, n=8 for THDOC), shaded bars on α4β3δ (n=3). Enhancements of 100 µM GABA evoked peak current responses by 3 µM etomidate and propofol, and 1 µM THDOC are statistically significant (p < 0.01). A comparison of αβ3δ vs. αβ receptors responses to THDOC, etomidate and propofol shows that differences are not statistically significant (p=0.32 for etomidate, p=0.76 for propofol, p=0.69 for THDOC).

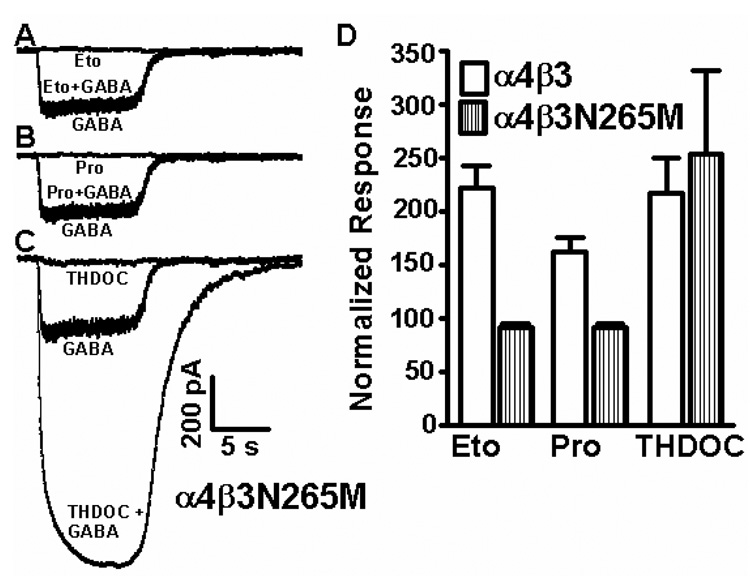

To assess whether etomidate and propofol effects on α4β3 receptors are mediated by the potential transmembrane sites, defined by mutations (like β3N265M) in α and β subunits (Belelli et al., 1997; Mihic et al., 1997) that drastically reduce etomidate and propofol enhancment, we tested whether etomidate and propofol responses in α4β3 receptors can be abolished with the β3N265M mutation that makes β3 subunit-containing receptors (and mice) insensitive to etomidate and propofol. Figure 4 shows that the β3N265M mutation introduced into binary α4β3 GABAARs prevents enhancement of saturating 100 µM GABA responses by 3 µM etomidate and propofol, and in fact reveals a trend towards current inhibition. In comparison, the steroid anesthetic THDOC (1 µM) retains the ability to enhance saturating GABA responses in α4β3N265M receptors. Original traces show that there is small amount of direct activation (in the absence of GABA) of these α4β3 receptors by 1 µM THDOC, indicating that direct activation of receptors might have contributed to anesthetic responses at the concentrations used.

Fig. 4. In mutant α4β3N265M binary receptors the enhancing effects of 3 µM etomidate and 3 µM propofol but not 1 µM THDOC are abolished.

The responses shown in A, B and C are from the same recording from a single α4β3N265M transfected cell (out of four similar recordings). (A) Etomidate (3 µM), (B) propofol (3 µM) and (C) THDOC (1 µM) were applied either alone or together with a saturating (100 µM) GABA concentration and compared to a saturating 100 µM GABA response. (D) Summary data (n=4, error bars are standard error of mean). Voltage clamp errors occurring with larger GABA currents may lead to underestimates in the amounts of current enhancement by anesthetics and overestimates of the amount of variability, particularly in the case of THDOC.

Discussion

Given that ‘binary’ GABAARs composed of α and β subunits are readily expressed in recombinant systems, it is important to establish their functional properties so that they can be distinguished from receptors that incorporate γ, δ or ε subunits into the pentamer. It is thought that most, but not all (Bencsits et al., 1999; Mortensen and Smart, 2006), native GABAA receptors have γ, δ, or ε subunits in the pentameric assembly with a stoichiometry of 2α, 2β, and 1γ, δ, or ε.

Extrasynaptic δ subunit-containing receptors are highly sensitive to GABA which allows them to sense ambient, extrasynaptic GABA concentrations and serve as a negative feedback system to prevent excessive excitation. We confirm here that α4β3δ receptors expressed in HEK cells are uniquely sensitive to GABA (EC50 of ~ 0.5 µM) with binary α4β3 receptors significantly less sensitive (GABA EC50 ~ 1.1. µM). This is consistent with the general notion that δ subunit-incorporation into functional receptors leads to an increase in GABA sensitivity. However, despite being less sensitive to GABA than α4β3δ receptors, the GABA sensitivity of α4β3 receptors remains in a range where these receptors could be activated by ambient GABA levels (300 nM GABA is ~ EC20 on α4β3 receptors), indicating that binary receptors, if present on the cell surface of neurons, could contribute to tonic GABA currents.

While δ subunit deletion in knock-out animals often leads to a significant reduction in tonic GABA currents in certain neurons, there are tonic GABA currents that remain in δ knock-out animals (Glykys et al., 2008; Glykys et al., 2007; Herd et al., 2008; Stell et al., 2003). Given the relatively high GABA sensitivity of binary α4β3 receptors, and the report that ~50% of all α4 subunit-containing receptors may form binary α4β receptors subtypes, while only 7% form α4βδ receptors (Bencsits et al., 1999), these binary receptors make excellent candidates for the GABAAR subtypes responsible for mediating tonic currents and etomidate enhancement of the tonic currents that persist in δ knock-out mice (Herd et al., 2008). Behaviorally, δ −/− mice show significantly reduced responsiveness to neurosteroid anesthetics, supporting the notion that δ subunit-containing GABAARs are important mediators of hypnotic/anesthetic actions of neuroactive steroids like alphaxolone, pregnanolone (Mihalek et al., 1999), which are close structural analogs of THDOC (THDOC is 21-hydroxyallopreganolone). However, the reduction in anesthetic efficacy (measured as duration of “loss of righting reflex”) of the GABA-enhancing anesthetics pentobarbital, propofol and etomidate were not considered statistically significant (i.e., p < 0.02) under the conditions and drug doses studied (Mihalek et al., 1999). This indicates that perhaps etomidate, propofol and barbiturates might be less specific for δ subunit-containing receptors and behavioral effects mediated by these drugs on δ-subunit-containing GABAARs might be masked by of other GABAA receptor targets, which we show here might include binary α4β3 GABAAR subtypes.

Using recombinant α1β3δ and α6β3δ receptors it has been previously shown that δ subunit-containing GABAARs exhibit higher potency and efficacy for etomidate, propofol, as well as GABAAR-active neurosteroids like THDOC, and barbiturates (Bianchi and Macdonald, 2003; Feng and Macdonald, 2004; Wallner et al., 2003; Wohlfarth et al., 2002). We confirm this increase in GABA efficacy for δ subunit containing receptors, but show that increases in GABA efficacy, i.e., increases in peak currents at saturating GABA concentrations, by GABAAR-active anesthetics etomidate, propofol, and THDOC can be similar in αβ and αβδ receptors. Therefore, increases in GABA efficacy by anesthetics are not necessarily due to δ subunit incorporation. In addition, enhancement by 3 µM propofol cannot be used to distinguish binary αβ3 GABAARs from αβ3δ receptors as previously implied (Yamashita et al., 2006).

Anesthetic actions of etomidate, propofol and barbiturates can be blunted by mutations (e.g., β3N265M) in GABA receptor β3 subunits (Siegwart et al., 2002); interestingly the same point mutation also reduces effects of high concentrations (≥100 mM) of EtOH on recombinant GABAARs receptors (Mihic et al., 1997; Wallner et al., 2006b). Most importantly, β3N265M point mutated mice lack the immobilizing anesthetic actions of etomidate and propofol (but not alphaxolone) in vivo (Jurd et al., 2003). In contrast, mice with an analogous mutation in the β2 subunit (β2N265S) only lose the sedative effects of etomidate (Reynolds et al., 2003). Given our observation of β3 specificity for low dose 30 mM alcohol actions, we have previously speculated that extrasynaptic δ subunit-containing GABA receptors might be preferentially associated with β3 subunits and this might contribute to β3 subunit-specificity of etomidate anesthetic effects as suggested by the β3N265M and β2N265S mice (Jurd et al., 2003; Reynolds et al., 2003; Wallner et al., 2003).

The action of most GABAAR-active anesthetics are determined by putative transmembrane receptor sites (THIP/gaboxadol as a GABA mimetic is an exception), defined by mutations that eliminate action of these anesthetics (Hosie et al., 2007; Jurd et al., 2003; Mihic et al., 1997). Recent etomidate photoaffinity labeling studies have proposed that these binding sites are present at the interface between α and β subunits at transmembrane sites (Li et al., 2006). Our finding here that etomidate, propofol and THDOC enhance α4β3 receptors, and that this enhancement is absent in α4β3N265M receptors is consistent with the notion that transmembrane acting GABA-anesthetics actions may be determined by binding sites formed between αβ subunits. Furthermore, the loss of etomidate and propofol enhancement in α4β3N265M transfected cells, demonstrates that there is a negligible contribution of endogenous β2 or β3 subunits, previously shown to be expressed in HEK 293 cells (Davies et al., 2000; Ueno et al., 1996)

A number of studies on δ subunit-containing receptors expressed in recombinant system have suggested that GABA is only a partial agonist on these receptors as it has been demonstrated that the low efficacy on δ subunit-containing receptors can be increased by the anesthetic neurosteroid THDOC with little or no changes in GABA potency/EC50 (Bianchi et al., 2002; Wallner et al., 2003; Wohlfarth et al., 2002). The amount of enhancement is dependent on the exact receptor composition with α1β3δ GABA peak currents being enhanced about 10 fold, with less enhancement of peak currents seen with α6β3δ receptors when expressed in HEK cells (Bianchi et al., 2002). The enhancement by 1 µM THDOC reported here with α4β3δ, α4β3 and α4β3N265M expressed in HEK cells is similar to the enhancement previously reported with α6β3δ receptors in HEK cells (Bianchi et al., 2002). The similarity of α6β3δ and α4β3δ in anesthetic enhancement of peak GABA responses is not surprising given that α4 and α6 subunit protein sequences are closely related. Even more dramatic increases in peak currents mediated by α4/6β3δ GABAARs are observed in response to etomidate and THDOC (Wallner et al., 2003) and for α1β2δ receptors to THDOC and tracazolate (Zheleznova et al., 2008) when expressed in oocytes. With α1β2δ receptors expressed in oocytes the GABA efficacy is so low that it was concluded that these receptors are essentially silent with GABA alone and that such silent receptors can be recruited by the neurosteroid THDOC as well as tracazolate (Zheleznova et al., 2008). In contrast to what we show here with α4β3 subunits expressed in HEK cells, Zheleznova et al. showed that currents from α1β2 injected oocytes were not enhanced by 1 µM THDOC and tracazolate at saturating 100 µM GABA concentrations. This indicates that GABA efficacy and enhancement by anesthetics on binary αβ receptors might be critically dependent on the exact subunit composition. In addition, the expression system might be important, with expression of δ subunit-containing receptors in oocyte apparently favoring lower efficacy and therefore more room for enhancement by GABAAR-active anesthetics. Many important open questions remain, including perhaps the most pressing, whether or not native δ subunit-containing and possibly native binary αβ receptors that mediate tonic currents show low GABA efficacy, and if GABA efficacy on native receptors subtypes can be modulated by pharmacological and physiological means.

While there is evidence that GABAAR-active anesthetics are more efficacious, and apparently some of them also more potent, on extrasynaptic receptor subtypes (Bonin and Orser, 2008; Cope et al., 2005; Feng and Macdonald, 2004; Stell et al., 2003; Wallner et al., 2003; Wohlfarth et al., 2002; Zheleznova et al., 2008), they are certainly not entirely selective for extrasynaptic receptors. Indeed, at higher concentrations they are allosteric modulators (gaboxadol/THIP as a GABA analog is an exception) on classical synaptic GABAAR subtypes where they increase the potency of GABA (Rusch et al., 2004; Siegwart et al., 2002). The high GABA efficacy of classical γ subunit-containing synaptic receptors leaves little room for increases in the maximum GABA current in the presence of anesthetics (Rusch et al., 2004). However, similar to benzodiazepines, anesthetics slow the decay of synaptic responses, and this may contribute to sedation and anesthesia. Given that many GABAAR-active anesthetics increase the GABA sensitivity of γ subunit-containing receptors, the presence of relevant concentrations of anesthetics might increase GABA sensitivity of certain γ subunit-containing receptor subtypes so that otherwise “silent” GABAAR populations (possibly even regardless whether they are synaptic or extrasynaptic), could now be activated by low ambient GABA concentrations, thereby giving rise to anesthetic-induced forms of tonic GABA inhibition that could mediate behavioral aspects of anesthetic actions.

While there are currently more open questions than answers, we are confident that a better understanding of the physiology and pharmacology of native and recombinant GABAA receptor subtypes will allow us to discriminate in the future which of the many native GABA receptors subtypes contribute to the many aspects of actions of different GABAAR-active anesthetics.

Methods

Propofol and etomidate were obtained from Tocris. THDOC (3α,21-Dihydroxy-5α-preganan-20-one) was obtained from Sigma. Propofol, etomidate, and THDOC were dissolved in DMSO as 100 mM stock solutions. β-CCE was a gift from Ferrosan (Copenhagen). Most other standard chemicals, including EtOH, were obtained from Sigma.

Cell Transfection

GABAAR cDNAs were as previously described (Hanchar et al., 2006). To increase δ subunit incorporation into functional GABAARs, we transfected human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells with five-fold excess of δ subunit plasmid versus α/β plasmid DNA; the total amounts of DNA are 4 µg α, 4 µg β, 20 µg δ (δ cDNA omitted for αβ receptors) together with 0.4 µg of eGFP-plasmid DNA for each 10 cm diameter plate. HEK cells were transfected using a DEAE-Dextran transfection method as previously described (Meera et al., 1997). Briefly, HEK cells were seeded at a density of ~2.5 × 106 cells per 10 cm diameter culture plate with DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, and maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Cells were exposed for two hours to a transfection mixture consisting of DEAE-dextran (0.5 mg/ml in DMEM) and endotoxin-free plasmid DNA, followed by a brief shock with 5% DMSO in PBS. Electrophysiological recordings were preformed starting 70 hours post transfection on cells plated on polylysine-coated cover slips.

Electrophysiological recordings in HEK cell

Whole-cell currents were recorded at room temperature using the patch clamp technique (Axopatch 200 B amplifier, Molecular Devices, USA) at a holding potential of −60 mV. The external solution is (in mM): 142 NaCl, 1 CaCl2, 6 MgCl2, 8 KCl, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 (327–330 mOsm). The pipette internal solution contained in mM: 140 CsCl, 4 NaCl, 0.5 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, 5 EGTA, 2 Mg2+ ATP, and 0.2 GTP. Drug solutions were applied using a multibarrel pipette driven by a stepper motor (SF77B, Warner Instruments) with an exchange time of around 10 ms. Recording pipettes had a bath resistance of around 4 MΩ.

Data analysis

Whole-cell currents were analyzed using Clampfit 9 (Molecular Devices). The normalized concentration-response data were least-square fitted (using the “Solver” function in Microsoft EXCEL) using the Hill equation: I/Imax= (1/(1 + (EC50/[A])n) where EC50 represents the concentration of the agonist ([A]) inducing 50% of the maximal current evoked by a saturating concentration of the agonist and n is the Hill coefficient. I is the peak current evoked by a given concentration of GABA. Imax is the maximal current at saturating GABA concentrations.

Acknowledgements

Supported by NIH grant NS035985 (T.S.O and R.W.O) and by funds to the University of California to support research and a new drug development program for alcoholism and addiction (R.W.O).

Glossary

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- GABAAR

type A GABA receptor

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- β-CCE

β-carboline-3-carboxyethyl ester

- EtOH

ethanol

- THDOC

tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone or 3α,21-dihydroxy-5α-preganan-20-one

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baburin I, Khom S, Timin E, Hohaus A, Sieghart W, Hering S. Estimating the efficiency of benzodiazepines on GABAA receptors comprising γ1 or γ2 subunits. Br J Pharmacol E-Pub online. 2008 doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belelli D, Lambert JJ, Peters JA, Wafford K, Whiting PJ. The interaction of the general anesthetic etomidate with the GABAA receptor is influenced by a single amino acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:11031–11036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.11031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bencsits E, Ebert V, Tretter V, Sieghart W. A significant part of native GABAA receptors containing α4 subunits do not contain γ or δ subunits. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19613–19616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi MT, Haas KF, Macdonald RL. Alpha1 and alpha6 subunits specify distinct desensitization, deactivation and neurosteroid modulation of GABA(A) receptors containing the delta subunit. Neuropharmacology. 2002;43:492–502. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi MT, Macdonald RL. Neurosteroids shift partial agonist activation of GABAA receptor channels from low- to high-efficacy gating patterns. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10934–10943. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-34-10934.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonin RP, Orser BA. GABA(A) receptor subtypes underlying general anesthesia. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caraiscos VB, Elliott EM, You-Ten KE, Cheng VY, Belelli D, Newell JG, Jackson MF, Lambert JJ, Rosahl TW, Wafford KA, MacDonald JF, Orser BA. Tonic inhibition in mouse hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons is mediated by α5 subunit-containing GABAA receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3662–3667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307231101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra D, Jia F, Liang J, Peng Z, Suryanarayanan A, Werner DF, Spigelman I, Houser CR, Olsen RW, Harrison NL, Homanics GE. GABAA receptor α4 subunits mediate extrasynaptic inhibition in thalamus and dentate gyrus and the action of gaboxadol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15230–15235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604304103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope DW, Hughes SW, Crunelli V. GABAA receptor-mediated tonic inhibition in thalamic neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11553–11563. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3362-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PA, Hoffmann EB, Carlisle HJ, Tyndale RF, Hales TG. The influence of an endogenous β3 subunit on recombinant GABAA receptor assembly and pharmacology in WSS-1 cells and transiently transfected HEK293 cells. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:611–620. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00163-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrant M, Nusser Z. Variations on an inhibitory theme: phasic and tonic activation of GABAA receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:215–229. doi: 10.1038/nrn1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng HJ, Bianchi MT, MacDonald RL. Pentobarbital differentially modulates α1β3δ and α1β3γ2L GABAA receptor currents. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66:988–1003. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.002543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng HJ, Macdonald RL. Multiple actions of propofol on αβγ and αβδ GABAA receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66:1517–1524. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.003426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glykys J, Mann EO, Mody I. Which GABA(A) receptor subunits are necessary for tonic inhibition in the hippocampus? J Neurosci. 2008;28:1421–1426. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4751-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glykys J, Peng Z, Chandra D, Homanics GE, Houser CR, Mody I. A new naturally occurring GABAA receptor subunit partnership with high sensitivity to ethanol. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:40–48. doi: 10.1038/nn1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasshoff C, Drexler B, Rudolph U, Antkowiak B. Anaesthetic drugs: linking molecular actions to clinical effects. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:3665–3679. doi: 10.2174/138161206778522038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günther U, Benson J, Benke D, Fritschy JM, Reyes G, Knoflach F, Crestani F, Aguzzi A, Arigoni M, Lang Y, Bluethmann H, Möhler H, Lüscher B. Benzodiazepine-insensitive mice generated by targeted disruption of the γ2 subunit gene of GABAA receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7749–7753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanchar HJ, Chutsrinopkun P, Meera P, Supavilai P, Sieghart W, Wallner M, Olsen RW. Ethanol potently and competitively inhibits binding of the alcohol antagonist Ro15-4513 to α4/6β3δ GABAA receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8546–8550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509903103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanchar HJ, Dodson PD, Olsen RW, Otis TS, Wallner M. Alcohol-induced motor impairment caused by increased extrasynaptic GABAA receptor activity. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:339–345. doi: 10.1038/nn1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herd MB, Haythornthwaite AR, Rosahl TW, Wafford KA, Homanics GE, Lambert JJ, Belelli D. The expression of GABAA β subunit isoforms in synaptic and extrasynaptic receptor populations of mouse dentate gyrus granule cells. J Physiol. 2008;586:989–1004. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.146746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosie AM, Wilkins ME, Smart TG. Neurosteroid binding sites on GABA(A) receptors. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;116:7–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurd R, Arras M, Lambert S, Drexler B, Siegwart R, Crestani F, Zaugg M, Vogt KE, Ledermann B, Antkowiak B, Rudolph U. General anesthetic actions in vivo strongly attenuated by a point mutation in the GABAA receptor β3 subunit. Faseb J. 2003;17:250–252. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0611fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneussel M, Betz H. Clustering of inhibitory neurotransmitter receptors at developing postsynaptic sites: the membrane activation model. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:429–435. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01627-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GD, Chiara DC, Sawyer GW, Husain SS, Olsen RW, Cohen JB. Identification of a GABAA receptor anesthetic binding site at subunit interfaces by photolabeling with an etomidate analog. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11599–11605. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3467-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meera P, Wallner M, Song M, Toro L. Large conductance voltage- and calcium-dependent K+ channel, a distinct member of voltage-dependent ion channels with seven N-terminal transmembrane segments (S0–S6), an extracellular N terminus, and an intracellular (S9–S10) C terminus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:14066–14071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.14066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalek RM, Banerjee PK, Korpi ER, Quinlan JJ, Firestone LL, Mi ZP, Lagenaur C, Tretter V, Sieghart W, Anagnostaras SG, Sage JR, Fanselow MS, Guidotti A, Spigelman I, Li Z, DeLorey TM, Olsen RW, Homanics GE. Attenuated sensitivity to neuroactive steroids in GABAA receptor δ subunit knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:12905–12910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihic SJ, Ye Q, Wick MJ, Koltchine VV, Krasowski MD, Finn SE, Mascia MP, Valenzuela CF, Hanson KK, Greenblatt EP, Harris RA, Harrison NL. Sites of alcohol and volatile anaesthetic action on GABAA and glycine receptors. Nature. 1997;389:385–389. doi: 10.1038/38738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen M, Smart TG. Extrasynaptic αβ subunit GABAA receptors on rat hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Physiol. 2006;577:841–856. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.117952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen RW, Hanchar HJ, Meera P, Wallner M. GABAA receptor subtypes: the "one glass of wine" receptors. Alcohol. 2007;41:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds DS, Rosahl TW, Cirone J, O'Meara GF, Haythornthwaite A, Newman RJ, Myers J, Sur C, Howell O, Rutter AR, Atack J, Macaulay AJ, Hadingham KL, Hutson PH, Belelli D, Lambert JJ, Dawson GR, McKernan R, Whiting PJ, Wafford KA. Sedation and anesthesia mediated by distinct GABAA receptor isoforms. J Neurosci. 2003;23:8608–8617. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-24-08608.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richerson GB. Looking for GABA in all the wrong places: the relevance of extrasynaptic GABA(A) receptors to epilepsy. Epilepsy Curr. 2004;4:239–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1535-7597.2004.46008.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusch D, Zhong H, Forman SA. Gating allosterism at a single class of etomidate sites on α1β2γ2L GABAA receptors accounts for both direct activation and agonist modulation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20982–20992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400472200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santhakumar V, Hanchar HJ, Wallner M, Olsen RW, Otis TS. Contributions of the GABAA receptor α6 subunit to phasic and tonic inhibition revealed by a naturally occurring polymorphism in the α6 gene. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3357–3364. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4799-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegwart R, Jurd R, Rudolph U. Molecular determinants for the action of general anesthetics at recombinant α2β3γ2 GABAA receptors. J Neurochem. 2002;80:140–148. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stell BM, Brickley SG, Tang CY, Farrant M, Mody I. Neuroactive steroids reduce neuronal excitability by selectively enhancing tonic inhibition mediated by δ subunit-containing GABAA receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14439–14444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2435457100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno S, Zorumski C, Bracamontes J, Steinbach JH. Endogenous subunits can cause ambiguities in the pharmacology of exogenous GABAA receptors expressed in human embryonic kidney 293 cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50:931–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallner M, Hanchar HJ, Olsen RW. Ethanol enhances α4β3δ and α6β3δ GABAA receptors at low concentrations known to affect humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15218–15223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2435171100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallner M, Hanchar HJ, Olsen RW. Low dose acute alcohol effects on GABAA receptor subtypes. Pharmacol Ther. 2006a;112:513–528. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallner M, Hanchar HJ, Olsen RW. Low dose alcohol actions on α4β3δ GABAA receptors are reversed by the behavioral alcohol antagonist Ro15-4513. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006b;103:8540–8545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600194103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Bedford FK, Brandon NJ, Moss SJ, Olsen RW. GABAA-receptor-associated protein links GABAA receptors and the cytoskeleton. Nature. 1999;397:69–72. doi: 10.1038/16264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W, Faria LC, Mody I. Low ethanol concentrations selectively augment the tonic inhibition mediated by δ subunit-containing GABAA receptors in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8379–8382. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2040-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlfarth KM, Bianchi MT, Macdonald RL. Enhanced neurosteroid potentiation of ternary GABAA receptors containing the δ subunit. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1541–1549. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01541.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Wang W, Diez-Sampedro A, Richerson GB. Nonvesicular Inhibitory Neurotransmission via Reversal of the GABA Transporter GAT-1. Neuron. 2007;56:851–855. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita M, Marszalec W, Yeh JZ, Narahashi T. Effects of ethanol on tonic GABA currents in cerebellar granule cells and mammalian cells recombinantly expressing GABA(A) receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:431–438. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.106260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheleznova N, Sedelnikova A, Weiss DS. alpha1beta2delta, a silent GABAA receptor: recruitment by tracazolate and neurosteroids. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:1062–1071. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]