Abstract

TDP-43 is a highly conserved, 43-kDa RNA-binding protein implicated to play a role in transcription repression, nuclear organization, and alternative splicing. More recently, this factor has been identified as the major disease protein of several neurodegenerative diseases, including frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive inclusions and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. For the splicing activity, the factor has been shown to be mainly an exon-skipping promoter. In this study using the survival of motor neuron (SMN) minigenes as the reporters in transfection assay, we show for the first time that TDP-43 could also act as an exon-inclusion factor. Furthermore, both RNA-recognition motif domains are required for its ability to enhance the SMN2 exon 7 inclusion. Combined protein-immunoprecipitation and RNA-immunoprecipitation experiments also suggested that this exon inclusion activity might be mediated by multimeric complex(es) consisting of this protein interacting with other splicing factors, including Htra2-β1. Our data further evidence TDP-43 as a multifunctional RNA-binding protein for a diverse set of cellular activities.

TDP-43 is a ubiquitously expressed protein that was originally identified as a factor capable of binding to the TAR DNA of human immunodeficiency virus (1). It was later identified in searches for asymmetrically expressed mouse brain genes2 and for factor(s) binding to a GU-rich, exon-intron junction sequence of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR)3 pre-mRNA (2). Structurally, TDP-43 contains two RNA-recognition motifs (RRMs), RRM1 and RRM2, and a glycine-rich region in its C terminus. The TDP-43 protein is located primarily in the nucleus (3), and it could act as a transcriptional repressor (1, 3), translational repressor (4), as well as a splicing factor promoting the exon 9 exclusion of the CFTR pre-mRNA (2). As other RRM-containing, RNA-binding proteins (5), the RRM1 of TDP-43 contributes primarily to its RNA-binding ability, whereas RRM2 is needed for correct complex formation (6). The C terminus of TDP-43 including the glycine-rich domain is necessary for formation of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP)-rich complexes (7) and for causing the CFTR exon 9 to be skipped during splicing (8). Significantly, TDP-43 was later identified as the pathological signature protein for a number of neurodegenerative diseases, including frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive inclusions and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), with TDP-43(+), ubiquitin(+) inclusion bodies, or UBI, in the brain/neuron cell (9, 10, and 34). In particular, different miscleaved or modified forms of TDP-43 were trapped in these UBIs (9, 10). The recent analysis of the characteristics of TDP-43 in cultured rodent neurons suggested that the neurodegenerative diseases with TDP-43(+) UBIs likely resulted from the impairment/loss of a spectrum of neuronal functions of TDP-43 because of its trapping within the UBIs (4).

The splicing of the transcripts from the survival of motor neuron gene (SMN) has been one of the systems for intensive studies of the mechanisms of alternative splicing. The human genome consists of two nearly identical copies of SMN genes (SMN1 and SMN2). The critical difference between SMN1 and SMN2 is a translationally silent C (in SMN1) → T (in SMN2) change at position 6 of exon 7 (11, 12). Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), the second most common autosomal recessive disorder caused by degeneration of the α-motor neurons, has been unequivocally shown to be caused by homozygous loss or rare intragenic mutations of the SMN1 gene. The SMN2 gene fails to compensate for the loss of SMN1 in SMA because the T nucleotide at position 6 causes predominant exon 7 skipping, resulting in an unstable protein (SMNΔ7) with reduced oligomerization ability (13, 14). Two different models, loss of exonic splicing enhancer (ESE) (15) and gain of exonic splicing silencer (ESS) (16), have been proposed to explain for the differential splicing patterns of the SMN1 and SMN2 pre-mRNAs. Many trans-factors involved in SMN exon 7 splicing have been characterized (16–19), including the serine/arginine rich (SR) protein, SR-like factors, and hnRNP proteins known to be involved in constitutive as well as alternative splicing (20). Among them, Htra2-β1, SRp30c, and hnRNP G act as positive regulators through the AG-rich ESE element in SMN exon 7 (17–19), whereas hnRNP A1 acts as a negative regulator by binding to the ESS element created by the C → T change in the SMN2 exon 7 (16, 21). It is likely that apart from the above factors, other RNA-binding proteins might also promote SMN exon 7 inclusion through their direct or indirect association with the SMN pre-mRNAs and/or interactions with the ESE-associated splicing factors.

In the following, we provide the first evidence that TDP-43, in addition to its exon exclusion activity on the CFTR transcript, could promote the inclusion of exon 7 during splicing of the human SMN2 pre-mRNA. Furthermore, the known structural/functional motifs of TDP-43 are required for this exon-inclusion activity of TDP-43 as well as its interaction with the human SMN RNAs and other splicing factors.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmid Constructs—The minigene reporter constructs pCI-SMN1 and pCI-SMN2 containing the genomic SMN sequences from exons 6–8 were generous gifts from Dr. Elliot J. Androphy (Tufts University School of Medicine). Site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene) of the SMN1 exon 7 at the SE1, SE2, and SE3 elements, respectively, was carried out as described by Hofmann et al. (17). The construction of pSMN(E6)-CFTR 9-(E8), which contains the normal human CFTR intron 8-exon 9-intron 9 sequence flanked by the SMN exons 6 and 8, has been described by Wang et al. (8). The (TG)12T7 sequence in the CFTR intron 8 of pSMN(E6)-CFTR 9-(E8) was changed to the patient genotype (TG)12T3 by site-direct mutagenesis, resulting in the derivative pSMN(E6)-CFTR 9-(E8)-T3. This T7 → T3 change facilitates the CFTR exon 9 skipping in the transfected cells (22).

Expression Vectors—The cDNA of TDP-43 (GenBank accession no. BC025544) was amplified from the mouse brain RNA and cloned into a pEF-based vector that contain an N-terminal FLAG tag (Invitrogen). The different domains of TDP-43 were deleted using the site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The cDNA of the wild-type Htra2-β1 (GenBank accession no. U61267), hnRNP G (GenBank accession no. Z23064), and Fyn-p59 (GenBank accession no. Z97989) were amplified from 293 cell RNAs and cloned into pEF-based vector that contains N-terminal FLAG tag or C-terminal Myc tag (Invitrogen).

DNA Transfection and in Vivo Splicing Assay—293 cells (1 × 105 cells/60-mm-diameter culture plate) were cotransfected with different minigene reporter plasmids and expression plasmids by the calcium phosphate method. Total RNA was isolated 48 h after transfection using TRIzol (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions and subjected to reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis. cDNAs were then synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using the Superscript II system (Invitrogen). To ensure amplification of plasmid-derived transcript, PCR was carried out using a vector-specific forward primer (pCI-Fwd, 5′-GGT GTC CAC TCC CAG TTC AA-3′) and SMN-specific reverse primer (SMN exon 8-Rev, 5′-GCC TCA CCA CCG TGC TGG-3′). The products were resolved on 2% agarose gels and quantitated using an Alpha Imager 2200 (Alpha Innotech Corporation).

RNA Immunoprecipitation (RNA-IP)—293 cells without or with transfections (24 h after transfection) were collected and lysed in 500 μl of RNA-IP buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 15 mm EGTA, 100 mm NaCl, and 0.1% Triton X-100) supplemented with 1× protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science) and 10 units/ml RNAsin (Promega). The total lysate was incubated with 10μl of RNase-free DNase I (Roche Applied Science), incubated at room temperature for 20 min, and then immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG (M2, Sigma) or anti-Myc (9E10, Roche Applied Science) antibodies at 4 °C for 3 h. Agarose beads (GE Healthcare) were added for further incubation of 1 h. The beads were washed five times, and the RNAs in the pull-downs were extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen). 10% of the total lysate was processed in parallel to obtain the total input sample. The RNA pellet was dissolved in 10 μl of diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water, and 5 μl was used for RT-PCR analysis. The sequences of the primers are available upon request. For endogenous RNA-IP, antibodies against TDP-43 (rabbit polyclonal), hnRNP A1 (4B10, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) (Chemicon), and RNA binding protein 4 (RBM4) (a kind gift from Dr. W.-Y. Tarn), respectively, were used instead of the anti-FLAG and anti-Myc.

Protein-Protein Interaction Assay—293 cells were lysed by three cycles of freeze-thaw in Nonidet P-40 buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 1.0% Nonidet P-40 with 1× protease inhibitor). The lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 10 min, precleaned with 50% protein A-agarose beads (GE Healthcare) for 30 min at 4 °C, and then incubated with appropriate antibodies, e.g. anti-TDP-43, at 4 °C for 2 h. Protein A-agarose beads were then added and incubated for another 1 h. The bound precipitates were washed five times and analyzed by Western immunoblotting with appropriate antibodies, e.g. anti-Htra2-β1 (S-18, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). For RNase treatment, RNase A (Sigma) was added to the lysate to a final concentration of 10 μg/ml, and the reaction mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 30 min before the immunoprecipitation.

Oligonucleotide Preparation by in Vitro Transcription—The method followed that described by Wyatt et al. (23). Oligonucleotides corresponding to different regions of the wild-type and mutant SMN genes or CFTR genes were synthesized and annealed with a T7 promoter oligonucleotide, resulting in templates each having a double-stranded T7 promoter region and a single-stranded region that acted as a template for in vitro transcription. Using the biotinylated RNTP mix (Roche Applied Science) and T7 RNA polymerase (Promega), the in vitro transcription was performed at 37 °C for 4 h. After DNase digestion, the RNA transcripts were gel purified, precipitated, and quantified. The sequences of the different oligonucleotides are: T7 RNA pol, 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAG-3′; ex 7 SMN1, 5′-ATTATGCTGAGTGATATCCCAAAGTCTGTTTTAGTTTTTCTTCCT-3′; ex 7 SMN2, 5′-ATTATGCTGAGTGATATCCCAAAATCTGTTTTAGTTTTTCTTCCT-3′; ex 6 SMN, 5′-ATTATGCTGAGTGATATCCTATTAAGGGGGTGGTGGAGGGTATAC-3′; ex 7 SMN1 (SE2 MUT), 5′-ATTATGCTGAGTGATATCCCAAAGTCTGTTTTAGTTAATAATAAT-3′; 3 X SE2, 5′-ATTATGCTGAGTGATATCTTTCTTCCTTTTCTTCCTTTTCTTCCT-3′; (UG)12, 5′-ATTATGCTGAGTGATATCACACACACACACACACACACACAC-3′; tubulin, 5′-ATTATGCTGAGTGATATCAAGAGACATCCACCGTTTATACAAGGAGCACGGTAG-3′.

In Vitro RNA-Protein Binding—293 cells (2 × 106) were transfected with 2 μg of the expression plasmids pEF-FLAG-TDP-43, pEF-Myc-Htra2-β1, pEF-FLAG-hnRNP G, or pEF-FLAG-Fyn. The nuclear extracts were prepared 36 h after transfection and precleaned by incubation with 100 μl of streptavidin beads (Sigma) for 1 h at 4 °C. 2.5 μg of the biotin-labeled RNA, prepared as described in the previous section, were reacted with 50 μl of streptavidin beads in a binding buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 50 mm KCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, and 0.5 mm DTT supplemented with 10 units/ml RNAsin) for 1 h at 4 °C. These RNA oligonucleotide-conjugated beads were then incubated with the precleaned nuclear extract for 90 min at 4 °C with constant shaking. The bound fractions were washed five times with NET-2 buffer containing 0.2% Nonidet P-40 and then analyzed by Western blotting.

RNA Interference (RNAi) Assay—293 (1 × 105) cells/well were put on 6-well culture plates. After 24 h, the cells were transfected with 50 pmol of duplex siRNAs (Ambion) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). After another 48 h, the minigene reporter plasmids (1.0 μg/well) were transfected. Cells were collected 24 h after the second transfection for preparation of the total RNAs and total cellular proteins. For RNAi, the following RNA interference oligonucleotides (Ambion) were used: (sense strand) human TDP-43, 5′-GGUUGAAAUAUUGAGUGGU-3′; human Htra2-β1 (SFRS10), 5′-GGUCUUACAGUCGA GAUUA-3′; human hnRNP A1, 5′-CUACAAUG AUUUUGGGAAU-3′. Antibodies against TDP-43, Htra2-β1 (S-18, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), hnRNP A1 (4B10, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and tubulin (Sig ma), respectively, were used to check the protein amounts before and after RNAi by Western blotting.

RESULTS

TDP-43 Stimulated the Inclusion of Exon 7 during Splicing of SMN2 Pre-mRNA—To address the possible involvement of TDP-43 in SMN splicing, assays of the SMN2 exon 7-splicing in vivo were carried out by cotransfection experiments. The SMN minigenes used in the assay contained either SMN1 or SMN2 fragments from exons 6–8 cloned in the mammalian expression vector pCI (left maps, Fig. 1A). Expression plasmids encoding FLAG-tagged TDP-43 and Myc-tagged Htra2-β1, a RNA-binding protein known to cause exon 7 inclusion of SMN (17), were individually cotransfected with either pCI-SMN1 or pCI-SMN2. As shown by RT-PCR analysis, coexpression of TDP-43 did not change the splicing pattern of the SMN1 transcript containing exons 6/7/8 (compare lanes 1 and 2, left panel of Fig. 1B). For the SMN2 minigene, the splicing pattern resembled that of the endogenous SMN2 gene, with a more abundant level of the exon 7-skipped transcript (SMNΔ7) than the full-length one (FL-SMN) (lane 1 of the right panel of Fig. 1A and lane 3 of the left panel of Fig. 1B). Notably, coexpression of TDP-43 increased the relative amount of FL-SMN2 (lanes 2–5 of the right panel of Fig. 1A and lane 4 of the left panel of Fig. 1B). Thus, although TDP-43 has been known mainly as an exon-skipping factor (22, 24), it appeared to be an exon-inclusion factor for SMN splicing. Although the exon-inclusion effect of TDP-43 was not as high as that of Htra2-β1 (lanes 6–9, right panel of Fig. 1A and lane 5, left panel of Fig. 1B), the data of Fig. 1 provided the first evidence that, similar to the RNA-binding proteins such as Htra2-β1, SRp55, and SRp30c (25, 26), TDP-43 also could play dual roles in alternative splicing.

FIGURE 1.

Enhancement of SMN2 exon 7 inclusion by overexpressed TDP-43. A. Left panel, schematic representations of the two pEF-based plasmids expressing FLAG-TDP-43 and Myc-Htra2-β1, and pCI-based SMN minigene constructs, respectively. The small arrows indicate the locations of the primer pair used for RT-PCR analysis of SMN minigene expression. The location of C → T change at position 6 of the exon 7 of SMN2 is indicated by an asterisk. Right panel, RT-PCR analysis of the total RNAs isolated from pCI-SMN2-transfected 293 cells without (lane 1) or with cotransfection of the plasmid pEF-FLAG-TDP-43 (lanes 2–5) or pEF-Myc-Htra2-β1(lanes 6–9). The amounts of the cotransfected plasmids (μg) are indicated. B. Left panel, RT-PCR analysis of the expression of the SMN1 (lanes 1 and 2) or SMN2 minigene (lanes 3–5) as affected by coexpression of FLAG-TDP-43 (lanes 2 and 4), Myc-Htra2-β1(lane 5), or a combination of both (lane 6). 1 μg of each of the reporter plasmid and 1 μg of each of the expression plasmids were used in transfection. Asterisk indicates the mismatched heterodimer formed between the RT-PCR products from the SMN1 and SMN2 templates. The band on the top of the gel, which is most abundant in lane 5, is the incomplete splicing product containing intron 7. Both of the above were identified by cloning and sequencing of the bands excised from the gel. Right panel, histobar graph comparing the enhancing effects of SMN2 exon 7 inclusion by overexpression of TDP-43 and/or Htra2-β1. The effects are expressed as the ratios of the RT-PCR band signals of FL-SMN/SMNΔ7 averaged from three independent cotransfection experiments as exemplified in the gel in the left panel.

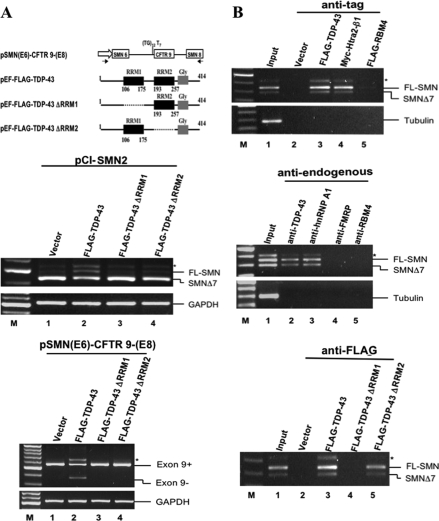

The functional requirement of the RRM domains for the enhancement of the SMN2 exon 7 inclusion by TDP-43 was assessed by cotransfection experiments. 293 cells were transfected with the pCI-SMN2 minigene along with the expression plasmids encoding FLAG-TDP-43 and its deletion mutants lacking the RRM1 or RRM2, respectively. As shown by the RT-PCR analysis of Fig. 2A, deletion of either RRM1 or RRM2 abolished the ability of TDP-43 to cause exon 7 inclusion of the SMN2 minigene transcript (compare lanes 2–4, middle panel of Fig. 2A). Both RRM1 and RRM2 were also required for the exon-skipping capability of TDP-43 to enhance exon skipping of the CFTR transcript (bottom panel, Fig. 2A), as initially demonstrated by Burrati and Barralle (6).

FIGURE 2.

Requirement of the RRM domains for TDP-43 to enhance SMN2 exon 7 inclusion and to associate with the SMN mRNAs. A. Top panel, schematic representations of the inserts of the pCMV-based CFTR minigene and pEF-based plasmids expressing the two RRM domain-deletion mutants of TDP-43. Middle panel, RT-PCR analysis of the total RNA isolated from 293 cells transfected with the SMN2 minigene plus the pEF vector (lane 1) or one of the three expression plasmids as indicated in lanes 2–4. FL, full-length. In the bottom panel, 293 cells were transfected with pSMN(E6)-CFTR9-(E8) together with the pEF-vector or with one of the three expression plasmids as indicated. Note that only the full-length TDP-43 could enhance the SMN2 exon 7 inclusion or the CFTR exon 9-skipping. B. RNA association assays. Top panel, 293 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing FLAG-TDP-43 (lane 3), Myc-Htra2-β1(lane 4), and FLAG-RBM4 (lane 5), respectively, and then immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG or anti-Myc. The RNAs in the immunoprecipitates were then analyzed by RT-PCR using primers specific for the SMN1/2 transcripts or the tubulin mRNA. Middle panel, RNA-IP analysis of 293 cell lysate with the use of antibodies against the endogenous TDP-43 (lane 2), hnRNP A1 (lane 3), FMRP (lane 4), and RBM4 (lane 5), respectively. Note that only the use of anti-TDP-43 (lane 2) and hnRNP A1 (lane 3) antibodies showed enrichment of SMN1 and SMN2 RNAs. Bottom panel, RNA-IP of cells transfected with pEF-FLAG-TDP-43 (lane 3), pEF-FLAG-TDP-43 ΔRRM1 (lane 4), or pEF-FLAG-TDP-43 ΔRRM2 (lane 5).

TDP-43 Interacted with the SMN Transcripts—In view of the above, we have examined whether TDP-43 is associated with the SMN transcripts by RNA-IP experiments. 293 cells were transfected with pEF-FLAG-TDP-43, pEF-Myc-Htra2-β1, pEF-FLAG-RBM4, pEF-FLAG-TDP-43 ΔRRM1, and pEF-FLAG-TDP-43 ΔRRM2, respectively. The total extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG or anti-Myc, and the RNAs contained within the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 2B, similar to Myc-Htra2-β1 known to bind SMN RNA (17), FLAG-TDP-43 was bound to both FL-SMN and SMNΔ7 RNAs (lanes 3 and 4, top panel of Fig. 2B). However, FLAG-RBM4 could not bind these RNAs (lane 5, top panel of Fig. 2B). We have also used anti-TDP-43 to examine whether the endogenous TDP-43 interacted with the SMN transcripts. Indeed, TDP-43 as well as hnRNP A1, but not FMRP and RBM4, was bound to both FL-SMN and SMNΔ7 RNAs (middle panel of Fig. 2B). The RRM1, but not RRM2, was required for the TDP-43-SMN RNA interaction, as shown in the bottom panel of Fig. 2B. Taken together, the data of Fig. 2 demonstrated that both RRM domains are necessary for the splicing activities, exon inclusion as well exon skipping, of TDP-43, and that the two RRM motifs were differentially required for the binding of TDP-43 with the SMN transcripts.

The AG-rich SE2 Element of the SMN Transcripts Was Required for TDP-43-stimulated Exon 7 Inclusion—To determine the region(s) of SMN RNA required for TDP-43 to enhance the exon 7 inclusion, we have adopted the splicing assay designed by Hofmann et al. (17). RT-PCR analysis was carried out with RNAs isolated from cells transfected with SMN1 minigenes containing site-directed mutations within ESE in the SMN exon 7 (Fig. 3). Similar to that found by others in studies of the SMN exon 7 inclusion effect of Htra2-β1 (17), mutation in either SE1 or SE3 element of the ESE resulted in a decreased amount the full-length SMN transcript (compare lanes 1 and 5 with lane 7, Fig. 3), whereas the mutant SE2 minigene produced only the SMNΔ7 RNA (lane 3, Fig. 3). As with the wild-type SMN2 minigene, cotransfection of pEF-FLAG-TDP-43 with the SMN1 minigene containing the SE1 or SE3 mutation caused exon 7 inclusion (compare lanes 2 and 6 with lanes 1 and 5, respectively, Fig. 3). In contrast, overexpression of TDP-43 could not stimulate the generation of exon 7-containing transcript from cotransfected SMN1 minigene containing the disrupted AG-rich SE2 element (compare lane 4 with lane 3, Fig. 3). These data suggested that an intact SE2 element of ESE was needed for TDP-43 to promote the exon 7 inclusion of the SMN transcript.

FIGURE 3.

Requirement of AG-rich SE2 element for TDP-43-induced SMN2 exon 7 inclusion. Upper panel, schematic representation of the SMN exon 7. The nucleotide difference between SMN1 and SMN2 at position 6 (*) in exon 7 and the stop codon (underlined) are indicated. Nucleotides mutated into U in the SE1, SE2, and SE3 elements, respectively, of the three mutant minigene plasmids are indicated with bold letters. Lower panel, data of RT-PCR analysis of RNAs from 293 cells transfected with the three mutant minigenes pCI-SMN1 (SE1) (lanes 1 and 2), pCI-SMN1 (SE2) (lanes 3 and 4), and pCI-SMN1 (SE3) (lanes 5 and 6), respectively, without (lanes 1, 3, and 5) or with (lanes 2, 4, and 6) coexpression of FLAG-TDP-43. The splicing patterns of the wild-type SMN1 and SMN2 minigene transcripts are shown (lanes 7 and 8) for comparison.

Previously, Htra2-β1 and hnRNP G have been shown to be positive regulators of the SMN exon 7 inclusion (17, 18). Furthermore, this property of Htra2-β1 correlated with its ability to bind to the intact, but not mutated, SE2 element (17). In view of the similar requirement of SE2 for the SMN exon 7-inclusion activity of TDP-43 (Fig. 3), we have determined whether the TDP-43-SMN RNA interaction was also mediated through binding with the SE2 element. For this, an in vitro RNA-protein binding assay was carried out (Fig. 4). Biotinylated RNA fragments synthesized by in vitro transcription were incubated with nuclear extracts prepared from 293 cells transfected with plasmids expressing FLAG-TDP-43, Myc-Htra2-β1, FLAG-hnRNP G, and FLAG-Fyn, respectively. Proteins associated with the biotin-labeled RNAs were pulled down by the streptavidin beads, washed, and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-FLAG or anti-Myc as the probe. As shown in Fig. 4, consistent with the literature report (17, 18), Myc-Htra2-β1 bound specifically to the exon 7 of either SMN1 or SMN2 but not to exon 6 (compare lanes 1 and 2 with lane 3, second panel from top of Fig. 4). Furthermore, Myc-Htra2-β1 could not bind to the exon 7 of SMN1 containing mutated SE2 element (compare lane 4 with lane 1, second panel from top of Fig. 4). Interestingly, FLAG-hnRNP G behaved similarly to Myc-Htra2-β1(third panel from top, Fig. 4; see “Discussion”). FLAG-TDP-43 bound to all of the RNA oligonucleotides tested with approximately similar efficiencies, except for the (UG)12 oligonucleotide that was shown by Buratti et al. (2) to bind TDP-43 with high efficiency (compare lanes 1–5 and 7 with lane 6, top panel of Fig. 4). The data of the RNA oligonucleotide binding assay were consistent with the RNA-IP results of Fig. 2B. They further suggested that if complex formation between TDP-43 and the SMN transcripts was required for the protein to enhance exon 7 inclusion, no binding of TDP-43 to specific regions of the SMN RNA was involved.

FIGURE 4.

Protein pulldown by biotinylated RNA. Biotin-labeled RNA oligonucleotides corresponding to sequences of the ex 7 SMN1, ex 7 SMN2, ex 6 SMN, ex 7 SMN1 (SE2 mut), 3× SE2, (UG)12 repeats, and a region of the tubulin mRNA (for the oligonucleotide sequences, see “Experimental Procedures”) were incubated with the nuclear extracts prepared from 293 cells transiently transfected with pEF-FLAG-TDP-43, pEF-Myc-Htra2-β1, pEF-FLAG-hnRNP G, and pEF-FLAG-Fyn, respectively. The RNA oligonucleotide–protein complexes were then pulled down with streptavidin beads, and the proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and probed with the anti-FLAG or anti-Myc antibody.

TDP-43 Interacted with Htra2-β1—Because both TDP-43 (Fig. 3) and Htra2-β1 (17) required an intact SE2 element to promote SMN exon 7 inclusion, we have examined whether there is an interaction between the two factors. Immunoprecipitation of the endogenous TDP-43 from 293 cell extract followed by Western blot analysis with anti-Htra2-β1 antibody as the probe showed that there was indeed an interaction between the two factors (compare lanes 1 and 2, Fig. 5A). Significantly, RNase treatment of the cell extract before immunoprecipitation abolished the anti-Htra2-β1 signal on the blot (lane 3, Fig. 5A), suggesting that the TDP-43–Htra2-β1 complex formation was augmented by the presence of RNA.

FIGURE 5.

Interaction of TDP-43 with Htra2-β1. A, coimmunoprecipitation (IP) was performed with 293 cell lysates using preimmune serum (lane 1) or with anti-TDP-43 antibody without (lane 2) or with prior RNase A treatment (lane 3). The precipitated samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-TDP-43, anti-Htra2-β1, or antitubulin. B, domain requirement of TDP-43 interaction with Htra2-β1. Cell lysates prepared from 293 cells exogenously expressing Myc-Htra2-β1 plus FLAG-TDP-43, FLAG-TDP-43 ΔRRM1, or FLAG-TDP-43 ΔRRM2 were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG, and the precipitates were then subjected to Western blotting (IB) with use of anti-Myc and anti-FLAG, respectively.

Only full-length TDP-43 stimulated the SMN exon 7 inclusion, whereas the deletion mutants (ΔRRM1 and ΔRRM2) did not (Fig. 2A). We thus have examined whether the RRM domain-deletion mutants of TDP-43 could interact with Htra2-β1. For this, pCI-Myc-Htra2-β1 was cotransfected with plasmids expressing FLAG-tagged TDP-43, TDP-43 ΔRRM1, and TDP-43 ΔRRM2, respectively, into 293 cells. As seen, both RRM1 and RRM2 were required for the interaction of TDP-43 with Htra2-β1 (compare lanes 2 and 3 with lane 1, Fig. 5B).

RNAi Knockdown of TDP-43 Had No Effect on SMN Splicing—To examine whether depletion of the endogenous TDP-43 had an effect on SMN splicing, we have analyzed the SMN splicing patterns of transfected SMN minigenes in 293 cells upon knockdown of TDP-43, Htra2-β1, and hnRNP A1, respectively, by RNAi oligonucleotides. As shown in Fig. 6A, depletion of either TDP-43 (lanes 1 and 2, Fig. 6A) or Htra2-β1(lanes 3 and 4, Fig. 6A) by RNAi knockdown did not affect the splicing of SMN1 or SMN2 compared with the no-RNAi controls (lanes 7 and 8, Fig. 6A). However, as found previously (16, 21), knockdown of hnRNP A1 promoted exon 7 inclusion of the SMN2 splicing (compare lane 6 with lane 8, Fig. 6A). The lack of an effect on SMN exon 7 inclusion by RNAi knockdown of TDP-43 was not an artifact because the depletion of TDP-43 did prevent exon 9 exclusion of the CFTR transcript (Fig. 6B), as expected from data of the previous study by others (22).

FIGURE 6.

Effects of RNAi of TDP-43 and Htra2-β1 on alternative splicing. A, 293 cells were transfected with siRNA oligonucleotides specific for TDP-43 (lanes 1 and 2), Htra2-β1(lanes 3 and 4), and hnRNP A1 (lanes 5 and 6), respectively. The in vivo splicing patterns of the SMN1/2 minigene transcripts were then analyzed by RT-PCR. The positions of the full-length (FL) and exon 7-skipped PCR products are indicated on the right. The lower Western blotting panel validates the depletion of the individual RNAi target proteins. B, requirement of TDP-43 for the CFTR exon 9 skipping. The assay was carried out as in A above, except that the pSMN(E6)-CFTR9-(E8)-T3 minigene and only the RNAi oligonucleotides specific for TDP-43 were used.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we have identified TDP-43 as a factor capable of stimulating an increase, by ∼2-fold, of the relative level of SMN2-derived, full-length SMN mRNA than the exon 7-skipped transcript. Thus, TDP-43 joins the category of proteins including Htra2-β1 (26, 27), hnRNP G (27), SRp55 (25, 26), and SRp30c (26) that play a dual regulatory role in alternative splicing. This exon-inclusion capability of TDP-43, along with its previously known activities of transcriptional repression (1, 3), nuclear scaffolding (3), and exon exclusion (2), further supports the functional diversity of a DNA/RNA-binding protein in the various types of cells, including the neurons (4). Related to this, it is interesting to note that among the diseases with TDP-43 as the pathological signature is ALS (10), the most common disorder in which the functions of both the upper and lower motor neurons are affected (28). Variants of ALS with a predominant involvement of the spinal motor neurons have been reported (29). Although the overlapping of disorder cases such as ALS and SMA is still controversial (30), the fact that a common factor is involved between the two diseases is intriguing.

Compared with the capability to induce exon 9 exclusion of the CFTR pre-mRNA (2, 6, 8), the ability of TDP-43 to enhance exon 7 inclusion of the SMN2 pre-mRNA (Figs. 1 and 7) exhibited similarities as well as differences with respect to the requirements of the structural/functional domains of the protein, the cis-acting element(s) on the pre-mRNAs, and the involvement of other trans-acting splicing factors. As shown in Fig. 2A, both RRMs were required for the SMN2 exon 7-inclusion effect of TDP-43, just like their positive roles in the CFTR exon 9 exclusion as enhanced by TDP-43. Interestingly, in our IP assay of the transiently transfected cells, deletion of either RRM abolished the interaction of TDP-43 with Htra2-β1 (Fig. 5B) or hnRNP G (data not shown), both of which have been shown before to promote the SMN2 exon 7 inclusion, and they physically interacted with each other as well (17, 18). Of these two factors, at least the interaction between Htra2-β1 and TDP-43 required the presence of RNA (Fig. 5A). Finally, TDP-43 interacts with the other factors known to regulate splicing, which include hnRNPs (7), SMN (3), and SRp55.4 The above together suggest that a multimeric complex could form, through one or more of the structural domains of TDP-43, among TDP-43 and other splicing factors.

FIGURE 7.

Models of involvement of TDP-43 and other factors in the alternative splicing of SMN1 and SMN2 pre-mRNAs. The regulation of the SMN pre-mRNAs by TDP-43, compared with other splicing factors, under different conditions is modeled in diagram presentation. In model 1, TDP-43, Htra2-β1, and hnRNP G participate in the SMN splicing under the normal condition. In model 2, they do not. The possible molecular basis for the consequences upon overexpression and RNAi knockdown of TDP-43, respectively, as shown in Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 6 are also depicted by the diagrams. Note that in either model, the SE2 element in exon 7 is required for the splicing reactions. For details, see “Discussion.”

It has been shown before that the enhancement of the SMN2 exon 7 inclusion by Htra2-β1 is mediated through binding of Htra2-β1 at the SE2 element of ESE in exon 7 (17). However, even though the SE2 element was also required for the positive regulatory effect of TDP-43 on the SMN2 exon 7 inclusion (Fig. 3), TDP-43 interacted with the SMN RNA without apparent sequence preference (Fig. 4). This lack of substrate sequence specificity of TDP-43 is very similar to many RRM-containing, RNA-binding factors (31), but it is in great contrast to Htra2-β1 (Fig. 4 and Ref. 17) and hnRNP G (Fig. 4). Note that although hnRNP G has been reported before to bind SMN RNA without sequence preference (18), longer RNA oligonucleotides (∼60 nucleotides) than ours (∼30 nucleotides) were used in the previous study. Overall, the data of Figs. 3, 4, 5 suggested that the SMN2 exon 7-inclusion effect by overexpressed TDP-43 was mediated through specific complex(es) formed at the SE2 element of ESE in exon 7.

But, is TDP-43 or Htra2-β1 involved in the exon 7 inclusion of SMN2 transcript under normal conditions? This question is particularly intriguing in view of the lack of effect on the splicing pattern of either SMN1 or SMN2 transcript upon RNAi depletion of TDP-43 or Htra2-β1 (Fig. 6A), despite the obvious SMN2 exon 7-inclusion effects by either factor in overexpressed cells. Several models, including the loss of splicing enhancer (15), creation of splicing silencer (16, 21), disruption of stimulatory RNA structure (32), and strengthening of an inhibitory RNA structure (33), have been proposed to account for the promotion of SMN2 exon 7 skipping because of the C → U change at position 6 of exon 7. Combining our data with these previous studies, most of which were based on overexpression assay in transfected cells, we suggest two alternative models for the regulation of SMN splicing by TDP-43 in relation to those other splicing factors. As depicted in Fig. 7 for the first model, TDP-43 as well as Htra2-β1, hnRNP G, SRp30c, etc. are involved in the regulation of SMN splicing under normal conditions (top two diagrams in model 1 of Fig. 7), and they together form a complex(es) centered on SE2 on both SMN transcripts. The C → U transition in SMN2 exon 7 creates ESS (16) where the hnRNP A1 binds and causes exon 7 skipping (21). However, this negative regulatory effect by the ESS–hnRNP A1 complex upon SMN2 exon 7 inclusion could be overcome by overexpressed TDP-43, Htra2-β1, hnRNP G, or SRp30c (middle two diagrams in model 1 of Fig. 7), all of which may induce the formation of new complex(es) on SE2 of the SMN2 pre-mRNA that are resistant to the negative effect by hnRNP A1. Alternatively, these overexpressed proteins could interact with hnRNP A1 and thus sequester this negative factor. When one or more of these splicing factors, such as TDP-43 or Htra2-β1, is depleted from the cells by RNAi (Fig. 6), other splicing factor(s), e.g. factor Z in the bottom diagrams of model 1 in Fig. 7, with degenerate function(s) could rescue the loss of the depleted factor(s).

However, it remains an open possibility that neither TDP-43 nor Htra2-β1 participates in the regulation of the alternative splicing of the SMN1 and/or SMN2 transcripts under normal cellular conditions (top two diagrams in model 2 of Fig. 7). The overexpressed factor(s) might force the formation of new splicing complex(es) that enhance the inclusion of the SMN2 exon 7 (middle diagram in model 2 of Fig. 7). In this scenario, RNAi knockdown of these factors is thus expected to have no effect on the splicing patterns of either SMN1 or SMN2 pre-mRNA (bottom two diagrams in model 2 of Fig. 7).

In summary, we have uncovered the capability of overexpressed TDP-43 to promote exon inclusion during splicing of the SMN2 pre-mRNA. This further evidences the functional complexity of this medically interesting RNA-binding factor. Whether TDP-43 plays dual roles of splicing globally in the cells remains to be investigated. The finding may also provide new directions for the identification of new targets in the design of therapies for SMA and ALS.

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues and friends, especially Karim Roder, Hung-Ting Chen, Jhong-Jhe You, Shau-Ching Wen, Kenrick Deen, Harry Wilson, Miranda Loney, Guang-Yuh Chiou, Yu-Chi Chou, Lydia Jakubickova, Lien-Szu Wu, and Bo-Tsang Huang, for helpful comments. pCI-SMN1 and pCI-SMN2 plasmids were the generous gifts from Dr. Elliot Androphy (Tufts School of Medicine, Boston, MA).

This work was supported by the Academia Sinica and National Science Council, Taipei, Taiwan. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

I.-F. Wang, unpublished results.

The abbreviations used are: CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; ESE, exonic splicing enhancer; ESS, exonic splicing silencer; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; hnRNP, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein; RNA-IP, RNA-immunoprecipitation; RNAi, RNA interference; RRM, RNA-recognition motif; RT, reverse transcription; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; SMN, survival of motor neuron; UBI, ubiquitin inclusion bodies; FMRP, fragile X mental retardation protein; RBM4, RNA binding protein 4; SR protein, serine/arginine rich protein.

J. K. Bose, unpublished results.

References

- 1.Ou, S. H., Wu, F., Harrich, D., Garcia-Martinez, L. F., and Gaynor, R. B. (1995) J. Virol. 69 3584–3596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buratti, E., Dork, T., Zuccato, E., Pagani, F., Romano, M., and Baralle, F. E. (2001) EMBO J. 20 1774–1784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang, I. F., Reddy, N. M., and Shen, C. K. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99 13583–13588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang, I. F., Wu, L. S., Chang, H. Y., and Shen, C. K. (2008) J. Neurochem. 105 797–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dreyfuss, G., Matunis, M. J., Pinol-Roma, S., and Burd, C. G. (1993) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 62 289–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buratti, E., and Baralle, F. E. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 36337–36343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buratti, E., Brindisi, A., Giombi, M., Tisminetzky, S., Ayala, Y. M., and Baralle, F. E. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 37572–37584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang, H. Y., Wang, I. F., Bose, J., and Shen, C. K. (2004) Genomics 83 130–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arai, T., Hasegawa, M., Akiyama, H., Ikeda, K., Nonaka, T., Mori, H., Mann, D., Tsuchiya, K., Yoshida, M., Hashizume, Y., and Oda, T. (2006) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 351 602–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neumann, M., Sampathu, D. M., Kwong, L. K., Truax, A. C., Micsenyi, M. C., Chou, T. T., Bruce, J., Schuck, T., Grossman, M., Clark, C. M., McCluskey, L. F., Miller, B. L., Masliah, E., Mackenzie, I. R., Feldman, H., Feiden, W., Kretzschmar, H. A., Trojanowski, J. Q., and Lee, V. M. (2006) Science 314 130–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monani, U. R., Lorson, C. L., Parsons, D. W., Prior, T. W., Androphy, E. J., Burghes, A. H., and McPherson, J. D. (1999) Hum. Mol. Genet. 8 1177–1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorson, C. L., Hahnen, E., Androphy, E. J., and Wirth, B. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96 6307–6311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lorson, C. L., and Androphy, E. J. (2000) Hum. Mol. Genet. 9 259–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorson, C. L., Strasswimmer, J., Yao, J. M., Baleja, J. D., Hahnen, E., Wirth, B., Le, T., Burghes, A. H., and Androphy, E. J. (1998) Nat. Genet. 19 63–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cartegni, L., and Krainer, A. R. (2002) Nat. Genet. 30 377–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kashima, T., and Manley, J. L. (2003) Nat. Genet. 34 460–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hofmann, Y., Lorson, C. L., Stamm, S., Androphy, E. J., and Wirth, B. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97 9618–9623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hofmann, Y., and Wirth, B. (2002) Hum. Mol. Genet. 11 2037–2049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young, P. J., DiDonato, C. J., Hu, D., Kothary, R., Androphy, E. J., and Lorson, C. L. (2002) Hum. Mol. Genet. 11 577–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krainer, A. R., Conway, G. C., and Kozak, D. (1990) Cell 62 35–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kashima, T., Rao, N., David, C. J., and Manley, J. L. (2007) Hum. Mol. Genet. 16 3149–3159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ayala, Y. M., Pagani, F., and Baralle, F. E. (2006) FEBS Lett. 580 1339–1344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wyatt, J. R., Chastain, M., and Puglisi, J. D. (1991) BioTechniques 11 764–769 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mercado, P. A., Ayala, Y. M., Romano, M., Buratti, E., and Baralle, F. E. (2005) Nucleic Acids Res. 33 6000–6010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin, W., and Cote, G. J. (2004) Cancer Res. 64 8901–8905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang, Y., Wang, J., Gao, L., Lafyatis, R., Stamm, S., and Andreadis, A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 14230–14239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nasim, M. T., Chernova, T. K., Chowdhury, H. M., Yue, B. G., and Eperon, I. C. (2003) Hum. Mol. Genet. 12 1337–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaw, C. E., al-Chalabi, A., and Leigh, N. (2001) Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 1 69–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ince, P. G., Lowe, J., and Shaw, P. J. (1998) Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 24 104–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dickson, D. W., Josephs, K. A., and Amador-Ortiz, C. (2007) Acta Neuropathol. 114 71–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maris, C., Dominguez, C., and Allain, F. H. (2005) FEBS J. 272 2118–2131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh, N. N., Androphy, E. J., and Singh, R. N. (2004) Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 14 271–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh, N. N., Androphy, E. J., and Singh, R. N. (2004) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 315 381–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang, I. F., Wu, L. S., and Shen, C. K. (2008) Trends Mol. Med., in press [DOI] [PubMed]