Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Infection with different genotypes of virulent Helicobacter pylori strains (cytotoxin-associated gene A [CagA]-and/or vacuolating cytotoxin A [VacA]-positive) can play a role in the development of atrophic gastritis, duodenal ulcer (DU) and gastric cancer (GC).

OBJECTIVE:

To determine whether patients with GC and H pylori-negative histological staining had previously been infected with H pylori CagA- and/or VacA-positive virulent strains.

METHODS:

Twenty-three GC patients with a mean (± SD) age of 68.14±9.8 years who tested H pylori-negative on histological staining took part in the study. Three control groups were included. The first group comprised 19 patients with past H pylori infection and DUs eradicated 10 years earlier, with a mean age of 58±18.2 years. H pylori-negative status for this group was determined every year with Giemsa staining, and follow-up testing occured 120±32 months (mean ± SD) after therapy. The subsequent control groups included 20 asymptomatic children, with a mean age of 7±4.47 years, and with H pylori-negative fecal tests; the final group contained 30 patients without clinical symptoms of H pylori infection, with a mean age of 68±11.6 years, who tested H pylori-negative by histological staining.

RESULTS:

Prevalence of CagA and VacA seropositivity, respectively was 82.6% and 73.91% in GC patients; 84.2% and 84.2% in H pylori-negative DU patients; 25% and 5% in H pylori-negative children; and 36.6% and 16.6% in the patients without clinical symptoms on histological staining. CagA and VacA antibody positivity was not significantly different between GC patients and patients with DUs that had been eradicated 10 years earlier. Significant positivity was found between the children’s group and the H pylori-negative (with past DUs) group (P<0.001). A statistically significant difference was found in age between groups (P<0.03).

CONCLUSIONS:

Patients with GC, even when H pylori-negative at the time of the present study, may have been infected by H pylori before the onset of the disease, as confirmed by CagA and VacA seropositivity. These data reinforce the hypothesis that H pylori may be a direct carcinogenic agent of GC.

Keywords: CagA, Gastric cancer, Helicobacter pylori, VacA

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

L’infection causée par les gènes de virulence CagA (pour cytotoxin-associated gene A) et/ou VacA- (pour vacuolating cytotoxin A) d’Helicobacter pylori peut jouer un rôle dans le développement de la gastrite atrophique, de l’ulcère gastroduodénal (UGD) et du cancer de l’estomac.

OBJECTIF :

Déterminer si les patients atteints de cancer de l’estomac chez qui on obtient une coloration histologique H. pylori-négative avaient déjà été infectés par des souches virulentes CagA- et/ou VacA-positives d’H. pylori.

MÉTHODES :

Vingt-trois patients atteints de cancer de l’estomac âgés en moyenne de 68,14 ± 9,8 ans ± É.-T. et présentant un test de dépistage de H. pylori-négatif à la coloration histologique ont pris part à l’étude. Trois groupes témoins ont été inclus. Le premier groupe comprenait 19 patients qui avaient déjà été infectés par H. pylori et avaient souffert d’UGD éradiqué dix ans auparavant, âgés en moyenne de 58 ± 18,2 ans. Dans ce groupe, on a contrôlé annuellement le statut H. pylori-négatif (une coloration de Giemsa et un test de contrôle ont été effectués 120 ± 32 mois (moyenne ± É.-T.) après le traitement. Le groupe témoin suivant a inclus 20 enfants asymptomatiques âgés en moyenne de 7 ± 4,47 ans chez qui des tests fécaux H. pylori-négatifs avaient été réalisés. Le dernier groupe comprenait 30 patients normaux âgés en moyenne de 68 ± 11,6 ans ayant obtenu un résultat H. pylori-négatif à la coloration histologique.

RÉSULTATS :

La prévalence de la CagA- et VacA-séropositivité a été respectivement de 82,6 % et de 73,91 % chez les patients atteints de cancer de l’estomac, de 84,2 % et de 84,2 % chez les patients atteints d’UGD H. pylori-négatif et de 25 %, de 5 % chez les enfants H. pylori-négatifs et de 36,6 % et 16,6 % chez les patients normaux, selon la coloration histologique. La positivité à l’égard des anticorps anti-CagA et VagA n’a pas été significativement différente entre les patients atteints de cancer de l’estomac ou d’UGD qui avaient subi un traitement d’éradication dix ans auparavant. Une positivité significative a été observée entre le groupe d’enfants et le groupe H. pylori-négatif (antécédents d’UGD) (p < 0,001). Une différence statistiquement significative a été observée quant à l’âge entre les groupes (p< 0,03).

CONCLUSION :

Les patients atteints de cancer de l’estomac, même H. pylori-négatifs au moment de l’étude, peuvent avoir été infectés par H. pylori avant le déclenchement de la maladie, comme le confirme la CagA et la VacA-séropositivité. Ces données étayent l’hypothèse selon laquelle H. pylori pourrait être un agent cancérogène direct dans le cancer de l’estomac.

Helicobacter pylori infection is one of the most widespread infections in humans. It is highly prevalent, especially in developing countries. In the western world, the infection rate is gradually decreasing; however, the prevalence still ranges from 25% to 50% (1). Virtually everyone infected with H pylori develops lifelong chronic type B gastritis, but only a minority of infected individuals will develop a clinically relevant condition, such as gastric cancer (GC). Seroepidemiological studies have demonstrated a three- to sixfold increased risk for infected individuals of developing GC (2–4). Based on these and other findings, H pylori has been classified as a class I human carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (5), although the exact nature and strength of its association with GC has remained debatable. However, recent meta-analyses (6–8) indicate a weaker RR (approximately two) than originally reported for seropositive individuals (2,3).

Although it is clear that H pylori infection increases the risk of these upper gastrointestinal diseases, it is still not fully understood why infected individuals develop one disease rather than another, emphasizing the importance of the host and other cofactors. It has been suggested that both the possession of the cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA), and the production of a vacuolating cytotoxin encoded by the vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA) gene, are linked to increased pathogenicity of H pylori strains (9,10). There is substantial evidence that H pylori infection, especially with the strains expressing the 128 kDa CagA protein, is associated with enhanced gastric inflammatory response and increased risk of developing atrophic gastritis (11–13), peptic ulcer (10,14,15) and even GC (2,16–18). However, conflicting results regarding the association between these virulence factors and clinical disease have been reported, and epidemiological papers suggest that not all tumours are H pylori-positive (19,20). The objective of the present study was to determine whether patients with GC who tested H pylori-negative by histological Giemsa staining were previously infected with H pylori CagA- and/or VacA-positive virulent strains.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Twenty-three individuals with GC (16 men, seven women; mean [± SD] age 68.14±9.8 years) who tested negative for H pylori by histological Giemsa staining were included in the study.

The presence of H pylori in gastric antral and corpus mucosa was determined by Giemsa staining, and also by immunoglobulin (Ig) G H pylori antibodies detected at the same time as VacA and CagA antibodies in human serum.

Endoscopic mucosal biopsies were obtained from the antrum and corpus mucosa, far from the tumour site, for histological assessment of H pylori. The patients underwent two antral biopsy samplings taken from the lesser and greater curvature, approximately 2 cm from the pylorus if possible. Two further biopsies of the gastric body were taken from the major and minor curves, if possible. Multiple biopsies were obtained from the tumour lesion to establish the diagnosis according to the Lauren classification (21).

In the present study, three control groups were used; each group consisted of H pylori-negative subjects. The first control group comprised 19 individuals (14 men, five women; mean age 58±18.2 years) with past H pylori infection and duodenal ulcers (DUs) that were eradicated 10 years earlier. In this group, patients were tested for H pylori-negative status every year by endoscopy, and gastric biopsy specimens were collected in the same way as for the GC group. For histopathological examination and H pylori detection, two antrum and two corpus biopsy specimens were stained using hematoxylin and eosin, and Giemsa staining. In this group of patients, IgG H pylori antibodies were also detected at the same time as VacA and CagA antibodies in human serum. The follow-up period of observation after H pylori eradication therapy was (mean ± SD) 120±32 months (range 96 to 144 months). All histological specimens were assessed by the same pathologist (EC).

The second control group was composed of 20 asymptomatic children (10 boys, 10 girls; mean age 7±4.47 years) with H pylori-negative fecal tests.

The third control group was composed of 30 patients without clinical symptoms (17 men, 13 women; mean age 68±11.6 years). All patients tested H pylori-negative by histological staining; again for this group, mucosal biopsies were obtained from the antrum and corpus mucosa, and were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and Giemsa staining. The endoscopic diagnosis of these patients was esophagitis in nine patients, gastritis in 17 patients, DU in two patients and normal mucosal pattern in another two patients. VacA, CagA and IgG H pylori antibodies were detected simultaneously.

Blood samples of all subjects recruited for the present study were collected. After centrifugation at 37°C, all serum samples were stored at −20°C and transported to the clinical immunology laboratory at Rivoli Hospital (Turin, Italy), where tests were performed.

CagA and VacA antibodies from all patients were detected by the Western blot technique, using a commercially available kit (Immunoblot Helicobacter IgG, Mikrogen, Germany). This test detects antibodies for proteins from different H pylori strains (22).

For IgG detection of H pylori in human serum, a two-step immunometric assay was applied, using a commercially available kit (Immulite 2000 H pylori IgG, Diagnostic Products Corporation, USA).

A commercially available kit (Premier Platinum HpSA enzyme immunoassay, Meridian Bioscience Inc, USA) was used to detect H pylori antigens in human stools.

Data are expressed as mean ± SD and as percentages of totals. The χ2 test was used for statistical analysis. Differences were considered to be statistically significant at P<0.05.

RESULTS

The prevalence of CagA, VacA and IgG seropositivity for H pylori antibodies was 82.6%, 73.91% and 56.5%, respectively in GC patients; 84.2%, 84.2% and 47.3%, respectively in H pylori-negative DU patients; 25%, 5% and 10%, respectively in H pylori-negative children; and 36.6%, 16.6% and 40%, respectively in patients without clinical symptoms who tested H pylori-negative by histological staining. A statistically significant difference was found in serum CagA and VacA antibodies, versus IgG H pylori antibodies in H pylori-negative DU patients (P=0.03). In the GC group, a statistically significant difference was found in CagA versus IgG detection (P=0.01), whereas in VacA versus IgG detection, there was no statistically significant difference (P=0.07).

Data on VacA, CagA and IgG antibodies against H pylori in GC patients, DU patients, asymptomatic children and patients without clinical symptoms are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Prevalence of VacA, CagA and immunoglobulin (Ig) G in gastric cancer patients, and in Helicobacter pylori-negative control patients

| Groups | CagA+/total patients (%) | VacA+/total patients (%) | IgG+/total patients (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gastric cancer | 19/23 (82.6) | 17/23 (73.9) | 13/23 (56.5) |

| Control | |||

| Duodenal ulcer | 16/19 (84.2) | 16/19 (84.2) | 9/19 (47.3) |

| Children | 5/20 (25) | 1/20 (5) | 2/20 (10) |

| Patients, no symptoms | 11/30 (36.6) | 5/30 (16.6) | 12/30 (40) |

+ Positive; CagA Cytotoxin-associated gene A; VacA Vacuolating cytotoxin A

There were no significant differences between sexes in serum CagA, VacA and IgG antibody positivity in H pylori-negative GC patients, or in patients with past H pylori infection and DU eradicated 10 years earlier.

A statistically significant difference was found in serum CagA, VacA and IgG antibodies in the GC group versus in children (P<0.001). No significant difference was found in the GC group versus patients with past H pylori infection and DUs eradicated 10 years earlier (P=0.858).

CagA and VacA antibody positivity was found to be significantly different between the GC and H pylori-negative (with past DUs) groups, versus children and patients without clinical symptoms (P<0.001).

Moreover, a highly significant difference was found in serum CagA and VacA antibodies in the asymptomatic children and patients without clinical symptoms, versus patients with past H pylori and DUs eradicated 10 years earlier (P<0.001). The statistical significance for IgG was P<0.018 between asymptomatic children and patients with past H pylori and DUs eradicated 10 years earlier; there was no statistically significant difference between children and patients without symptoms.

No statistically significant difference was found among CagA, VacA and IgG antibodies against H pylori in DU and GC patients whose H pylori infection was eradicated 10 years earlier. The respective P values were P=0.905, P=0.420 and P=0.920.

A weak statistically significant difference was also found in age among groups (P<0.03).

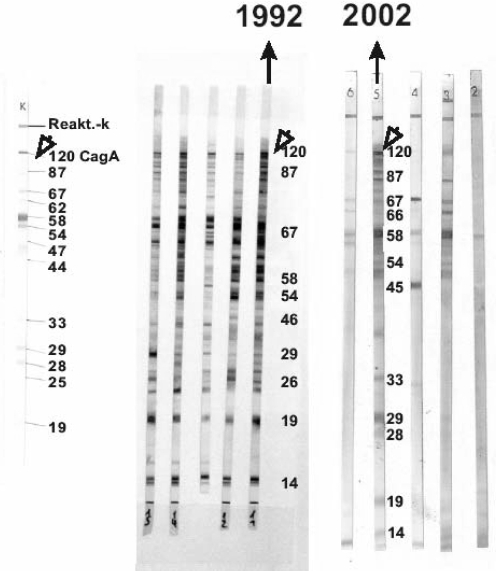

Figure 1 shows a sample of similar patterns of CagA, assessed by Western blot in 1992 and 2002, from a patient with past H pylori and DUs who tested negative to histological Giemsa staining for H pylori.

Figure 1).

Western blot of cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) antibodies in the sera of a duodenal ulcer patient whose Helicobacter pylori infection was eradicated 10 years earlier, and who tested negative to histological Giemsa staining with consistent patterns of CagA in 1992 and 2002

DISCUSSION

H pylori infection causes both intestinal and diffuse types of gastric adenocarcinoma. Its carcinogenic effects have been attributed to induction of inflammation. The phenotype of H pylori that expresses CagA causes higher degrees of acute and chronic inflammation than the CagA-negative condition. Recent serological studies have shown that CagA and VacA seropositivity is associated with an increased risk for atrophic gastritis and GC (12,17,19). The H pylori strain possessing CagA-enhanced gastric epithelial proliferation and apoptosis induces tyrosine phosphorylation of the CagA protein (20,23), causing gastric cells to produce high levels of interleukin-8, which plays a crucial role in the inflammatory cell response to infection (24).

Whereas some studies on GC patients were unable to find an association between VacA and CagA antibodies, and GC (25), other studies demonstrated a significant association between VacA and CagA antibodies, and GC (26). Some authors found no difference in the prevalence of anti-CagA antibodies between H pylori-positive DU patients and patients without DUs and GC (27,28).

Although GC patients tested negative for H pylori at the time of the present study, they tested positive for serological CagA, VacA and IgG antibodies. The presence of CagA, VacA and IgG antibodies against H pylori in these patients likely indicates H pylori infection before the appearance of GC. In fact, CagA-positive H pylori strains seem to induce a high immune response with a markedly higher frequency of IgA. Although literature is scarce, existing clinical data indicate that CagA antibodies persist longer after eradication treatment than antibodies detected by IgG ELISA; a stronger association emerged when antibodies to CagA were used as markers of H pylori exposure (29). It therefore seems reasonable, as other studies report (30), to assume that the addition of immunoblotting would result in a more correct representation of prior exposure than the use of IgG ELISA alone.

These data were also confirmed by the present study, in which patients with previous DUs eradicated 10 years earlier, who were known to be H pylori-negative at the time of the histological biopsy of the antrum and corpus, and were followed up for a long period of time (120±32 months) tested positive for VacA and CagA proteins more often than for IgG.

This was also confirmed by the high level of CagA and VacA than IgG antibodies for H pylori in the patients with GC and in asymptomatic children.

These data reinforce the hypothesis that CagA and VacA proteins induce a strong mucosal and systemic immune response and may represent an immunological memory from previous contact with the bacteria. The former DU patients showed seropositivity to CagA and VacA without any difference of prevalence versus GC patients, as some studies report. Seropositivity for CagA, VacA and IgG for H pylori in GC patients can be explained theoretically by a previous infection that was cured. Because several decades may pass between initiation and detection of GC, and the precancerous microenvironment promotes spontaneous eradication (31), substantial misclassification of relevant exposure to H pylori is likely to occur in case control and short-term follow-up studies. A declining association between H pylori and GC risk with advancing age could possibly be explained by increased exposure misclassification with advancing age.

Although the number of patients included in the present study was somewhat limited, it nevertheless reinforces the idea that CagA and VacA induce a strong mucosal and systemic immune response, and may represent an immunological memory from previous contact with the bacteria. H pylori can be considered a direct carcinogenic agent of GC, although it is not clear why some people develop cancer, and others only develop DUs or no pathology at all. Further studies are necessary for a better understanding of the pathogenic mechanism.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dunn BE, Cohen H, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:720–41. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.4.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Vandersteen DP, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1127–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nomura A, Stemmermann GN, Chyou PH, Kato I, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric carcinoma among Japanese Americans in Hawaii. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1132–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forman D, Newell DG, Fullerton F, et al. Association between infection with Helicobacter pylori and risk of gastric cancer: Evidence from a prospective investigation. BMJ. 1991;302:1302–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6788.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to HumansLyon, 7–14 June 1994IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum 1994611–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang JQ, Sridhar S, Chen Y, Hunt RH. Meta-analysis of the relationship between Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1169–79. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70422-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eslick GD, Lim LL, Byles JE, Xia HH, Talley NJ. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with gastric carcinoma: A meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2373–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danesh J. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer: Systematic review of the epidemiological studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:851–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Covacci A, Censini S, Bugnoli M, et al. Molecular characterization of the 128-kDa immunodominant antigen of Helicobacter pylori associated with cytotoxicity and duodenal ulcer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5791–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cover TL, Dooley CP, Blaser MJ. Characterization of and human serologic response to proteins in Helicobacter pylori broth culture supernatants with vacuolizing cytotoxin activity. Infect Immun. 1990;58:603–10. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.3.603-610.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crabtree JE, Covacci A, Farmery SM, et al. Helicobacter pylori induced interleukin-8 expression in gastric epithelial cells is associated with CagA positive phenotype. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:41–5. doi: 10.1136/jcp.48.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuipers EJ, Pérez-Pérez GI, Meuwissen SG, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori and atrophic gastritis: Importance of the cagA status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1777–80. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.23.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sozzi M, Valentini M, Figura N, et al. Atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia in Helicobacter pylori infection: The role of CagA status. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:375–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Figura N, Bugnoli M, Cusi MG, et al. Pathogenic mechanisms of Helicobacter pylori: Production of cytotoxin. In: Malfertheiner P, Ditschuneit H, editors. Helicobacter pylori, Gastritis and Peptic Ulcer. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1990. pp. 86–95. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orsini B, Ciancio G, Surrenti E, et al. Serologic detection of CagA positive Helicobacter pylori infection in a northern Italian population: Its association with peptic ulcer disease. Helicobacter. 1998;3:15–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.1998.08015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Orentreich N, Vogelman H. Risk for gastric cancer in people with CagA positive or CagA negative Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut. 1997;40:297–301. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.3.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blaser MJ, Perez-Perez GI, Kleanthous H, et al. Infection with Helicobacter pylori strains possessing cagA is associated with an increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2111–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rugge M, Cassaro M, Leandro G, et al. Helicobacter pylori in promotion of gastric carcinogenesis. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:950–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02091536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fox JG, Correa P, Taylor NS, et al. High prevalence and persistence of cytotoxin-positive Helicobacter pylori strains in a population with high prevalence of atrophic gastritis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:1554–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rokkas T, Ladas S, Liatsos C, et al. Relationship of Helicobacter pylori CagA status to gastric cell proliferation and apoptosis. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:487–93. doi: 10.1023/a:1026636803101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: Diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–49. doi: 10.1111/apm.1965.64.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andersen LP, Espersen F. Immunoglobulin G antibodies to Helicobacter pylori in patients with dyspeptic symptoms investigated by the western immunoblot technique. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1743–51. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.7.1743-1751.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Segal ED, Cha J, Lo J, Falkow S, Tompkins LS. Altered states: Involvement of phosphorylated CagA in the induction of host cellular growth changes by Helicobacter pylori. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14559–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Censini S, Lange C, Xiang Z, et al. Cag, a pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori, encodes type I-specific and disease-associated virulence factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14648–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamaoka Y, Kodama T, Kita M, Imanishi J, Kashima K, Graham DY. Relationship of vacA genotypes of Helicobacter pylori to cagA status, cytotoxin production, and clinical outcome. Helicobacter. 1998;3:241–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.1998.08056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miehlke S, Kirsch C, Agha-Amiri K, et al. The Helicobacter pylori vacA s1, m1 genotype and cagA is associated with gastric carcinoma in Germany. Int J Cancer. 2000;87:322–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graham DY, Genta RM, Graham DP, Crabtree JE. Serum CagA antibodies in asymptomatic subjects and patients with peptic ulcer: Lack of correlation of IgG antibody in patients with peptic ulcer or asymptomatic Helicobacter pylori gastritis. J Clin Pathol. 1996;49:829–32. doi: 10.1136/jcp.49.10.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iaquinto G, Todisco A, Giardullo N, et al. Antibody response to Helicobacter pylori CagA and heat-shock proteins in determining the risk of gastric cancer development. Dig Liver Dis. 2000;32:378–83. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(00)80256-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sörberg M, Engstrand L, Ström M, Jönsson KA, Jörbeck H, Granström M. The diagnostic value of enzyme immunoassay and immunoblot in monitoring eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Scand J Infect Dis. 1997;29:147–51. doi: 10.3109/00365549709035875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ekström AM, Held M, Hansson LE, Engstrand L, Nyrén O. Helicobacter pylori in gastric cancer established by CagA immunoblot as a marker of past infection. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:784–91. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.27999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuipers EJ. Review article: Exploring the link between Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13(Suppl 1):3–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]