Summary

Formation of single-strand DNA (ssDNA) tails at a double-strand break (DSB) is a key step in homologous recombination and DNA damage signaling. The enzyme(s) producing ssDNA at DSBs in eukaryotes remains unknown. We monitored 5’-strand resection at inducible DSB ends and identified proteins required for two stages of resection: initiation and long-range 5’-strand resection. The Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 complex (MRX) initiates 5’ degradation, whereas Sgs1 and Dna2 degrade 5’-strands exposing long 3’-strands at 4.4 kb/h rate. Deletion of SGS1 or DNA2 reduces resection and DSB repair by single strand annealing between distant repeats. Resection in the absence of SGS1 or DNA2 depends on Exo1. In exo1Δ sgs1Δ mutants the MRX complex and Sae2 in a stepwise manner generate only few hundred nucleotides of ssDNA at the break resulting in inefficient gene conversion and G2/M damage checkpoint arrest. We provide the first comprehensive model of the early steps of DSB repair in eukaryotes.

Introduction

In mitotic cells DNA recombination repairs double-strand breaks (DSBs) and gaps that occur spontaneously or are induced by chemicals or irradiation. DSBs occur also as intermediates of biological events such as meiotic recombination, V(D)J recombination or mating-type switching in yeast. DSB-induced homologous recombination (HR) is initiated by formation of 3’-OH single-stranded tails (Sun et al., 1991; White and Haber, 1990). The strand exchange protein Rad51 assembles a nucleofilament at 3’ ssDNA tails that carries out a search for homologous sequences and promotes strand invasion (reviewed in San Filippo et al., 2008; Symington, 2002). The same 3’ ssDNA tails at DSB ends constitute a signal for DNA damage checkpoint induction (Vaze et al., 2002; Zou and Elledge, 2003). Mec1/Ddc2 in yeast and ATR/ATRIP in mammals bind RPA-coated ssDNA tails and initiate a kinase cascade that leads to cell cycle arrest (reviewed in Harrison and Haber, 2006). Formation of 3’ ssDNA tails also determines the switch from the nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) to the HR pathway, because NHEJ preferentially utilizes the unresected ends for ligation (Ira et al., 2004).

In Escherichia coli, RecBCD, a complex of helicases and a nuclease, is responsible for the formation of 3’ ssDNA tails at DSBs (reviewed in Spies and Kowalczykowski, 2005). In eukaryotic cells, however, the major 5’ end resection activity remains unknown. Several proteins that are required for a normal rate of DSB end resection have been identified in budding yeast and mammals including the MRX/MRN complex (Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 in yeast and Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 in human) (Ivanov et al., 1994; Jazayeri et al., 2006), Sae2/CtIP (Clerici et al., 2005; Sartori et al., 2007), Exo1 (Llorente and Symington, 2004; Tsubouchi and Ogawa, 2000), H2AX, and the chromatin remodeling Ino80 or RSC complex (Shim et al., 2007; van Attikum et al., 2004). Both MRX and Sae2 belong to one epistasis group with respect to DSB resection (Clerici et al., 2005). Although deletion of any component of the MRX or Sae2 complex decreases the resection rate at DSBs, how MRX or Sae2 contributes to resection is unknown. Mre11 has multiple nuclease motifs but expression of mre11-H125N, which completely eliminates nuclease activity in vitro, was shown to retain a nearly normal resection rate, suggesting that the MRX complex may facilitate the access to DSB ends for other nuclease (Lee et al., 2002; Llorente and Symington, 2004). Also, the in vitro exonuclease activity of Mre11 has 3’ to 5’ polarity, which is opposite to the polarity of end degradation observed at DSBs in vivo (Furuse et al., 1998; Paull and Gellert, 1998; Trujillo et al., 1998). Mre11 nuclease activity is directly responsible for processing Spo11-induced DSBs only in meiotic cells, most likely by removing covalently bound Spo11 from DSB ends (Furuse et al., 1998; Moreau et al., 1999; Neale et al., 2005; Tsubouchi and Ogawa, 1998; Usui et al., 1998). Sae2 also exhibits nuclease activity (Lengsfeld et al., 2007). However, the role of this nuclease in DSB end resection is not yet defined. In mammals, loss of either the MRN complex, or the recently identified Sae2 ortholog CtIP results in a dramatic defect in processing mitotic DSBs (Jazayeri et al., 2006; Sartori et al., 2007), with checkpoint and recombination proteins not properly loaded at the γ-irradiation-induced damage sites.

Loss of Exo1, a 5’ to 3’ exonuclease, moderately reduces the rate of resection, but the more dramatic defect is observed only when both EXO1 and either the MRX complex or SAE2 are simultaneously deleted (Clerici et al., 2005; Llorente and Symington, 2004; Tsubouchi and Ogawa, 2000). Importantly, gene conversion is still accomplished in exo1Δ mre11Δ cells, suggesting that additional enzymes are able to generate ssDNA at DNA breaks.

Since none of the factors listed above is likely to be the primary nuclease responsible for resection of DSBs in budding yeast, we searched for an enzyme that provides a robust resection activity analogous to the bacterial RecBCD. By monitoring the kinetics of 5’ resection at regions immediately adjacent to, and at different distances from the break site, we identified mutants that are defective in the initiation or progression of 5’ strand resection. We demonstrate that the MRX complex and Sae2 are important only in the initiation of resection. We also identified two new factors involved in 5’ strand resection: Bloom and Werner syndromes’ helicases orthologue called Sgs1 and the Dna2 nuclease/helicase. In the absence of Sgs1 or Dna2, resection is very slow and depends on yet another nuclease: Exo1.

Results

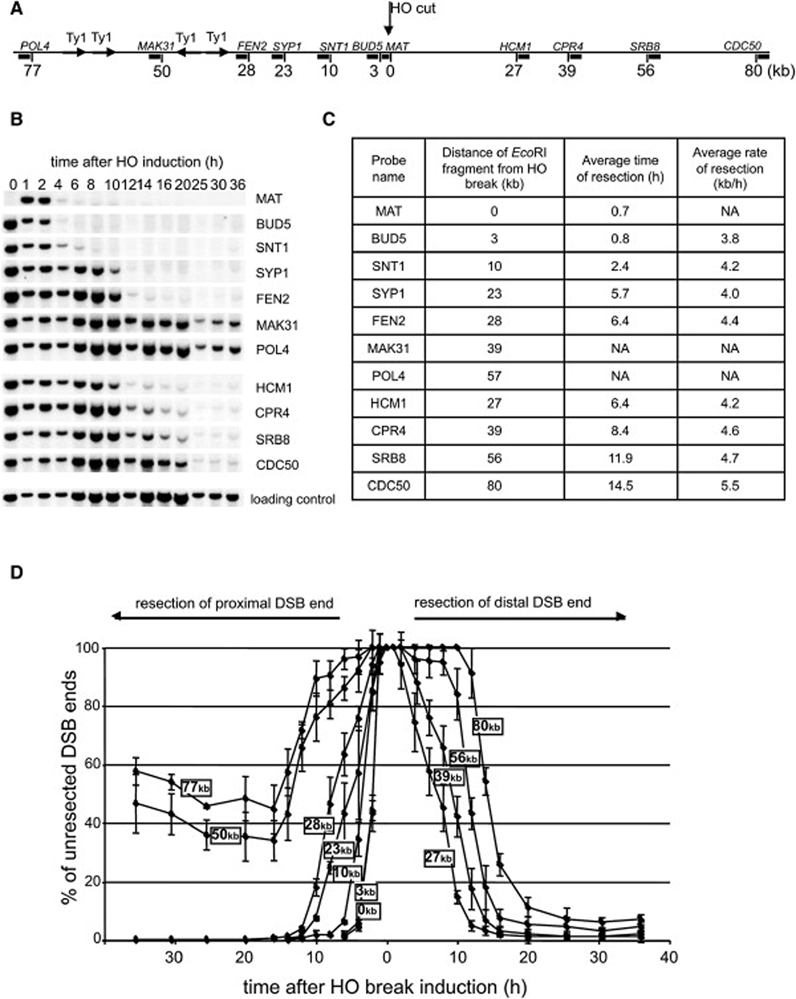

DSB resection rate in asynchronous wild-type cells

To define the roles of various factors in 5’ strand removal at DSBs in budding yeast, we first analyzed in detail how breaks are processed in wild-type cells. We used a strain that has a single HO endonuclease recognition site at the MAT locus on chromosome III. A DSB at MAT cannot be repaired by homologous recombination because the donor sequences HMR and HML are deleted. Following synchronous HO-induced cleavage, we monitored the rate of resection within 80 kb at each side of the break using a set of probes specific for sequences at different distances from the HO break (Figure 1A). As the 5’ strand is being degraded at DSB ends, the EcoRI enzyme is unable to cleave ssDNA, and the intensity of the bands corresponding to the DNA fragments by Southern blot hybridization becomes diminished (Figure 1B). We measured the band intensity corresponding to each probe over time and an average rate of resection was estimated from the time at which the signal intensity dropped to 50% of its original value measured 1 h after break induction. An average rate of resection in wild-type cells for all of the investigated EcoRI fragments is 4.4 kb/h (Figure 1C–D). A similar rate of resection was established previously in different assays (Fishman-Lobell and Haber, 1992; Vaze et al., 2002). Interestingly, resection at 30 kb proximal to the break is blocked. This is due to the presence of long inverted Ty1 transposon repeats that once resected immediately anneal to each other either within the same sister chromatid or between two different chromatids, forming a hairpin structure that blocks further processing. Deletion of Ty repeats restores resection beyond 30 kb (VanHulle et al., 2007; Ira and Haber, data not published). To avoid any impact of inverted repeats on resection in this study, we used probes located prior to the inverted Ty repeats only.

Figure 1. Analysis of 5’ strand resection in wild-type cells.

(A) Position of EcoRI sites and DNA probes used to analyze 5’ strand processing with respect to the HO recognition site on chromosome III. (B) Southern blot analysis of 5’ strand resection in wild-type cells. Names of the probes are indicated. (C) Average rate of resection beyond each studied EcoRI site. NA – not applicable. (D) Plot demonstrating percentage of unprocessed 5’ strand for each studied EcoRI site.

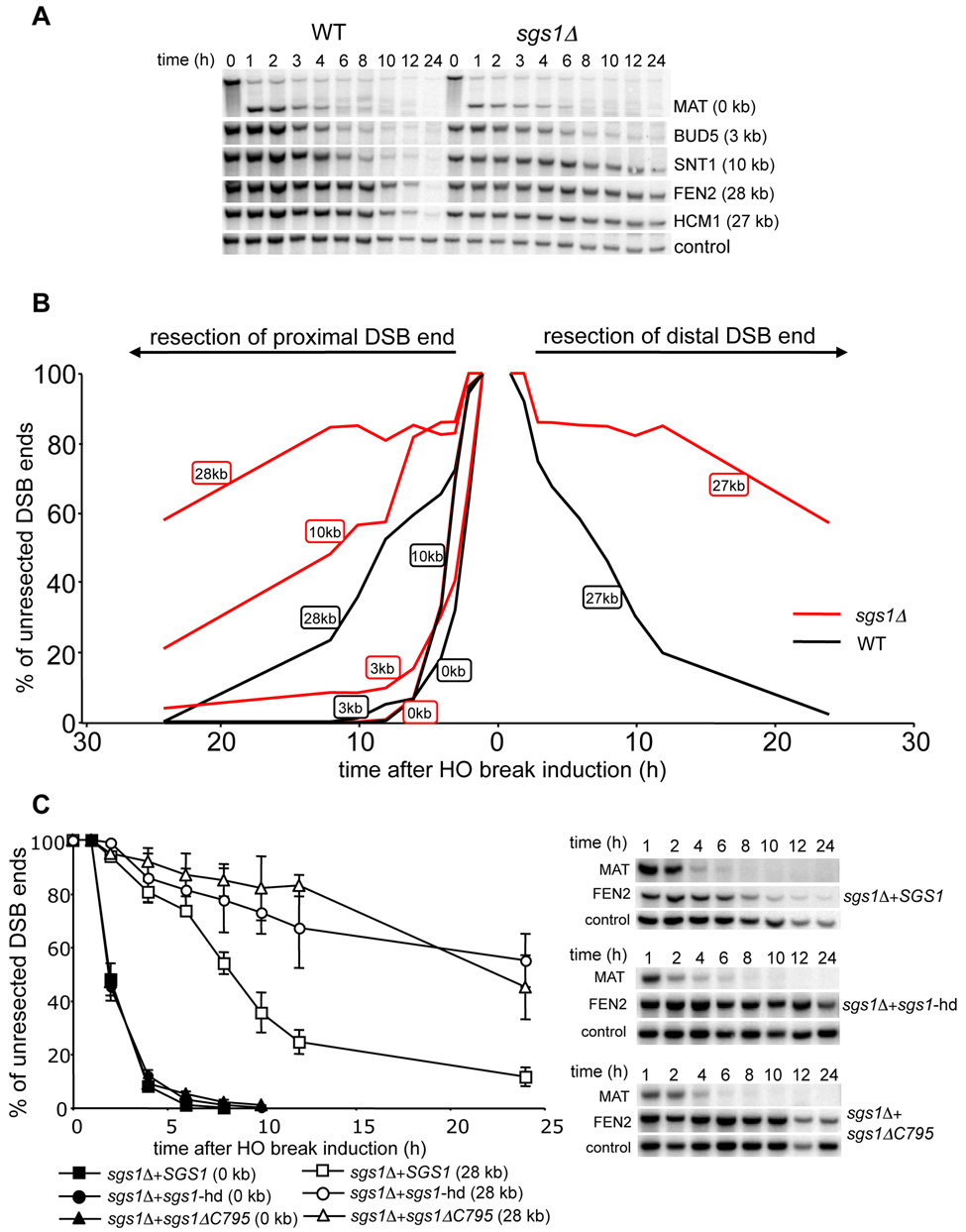

DSB resection rate and efficiency in sgs1Δ cells is markedly reduced

In E. coli, the nuclease component of the RecBCD complex degrades ssDNA unwound by helicases and initiates DSB-induced recombination. To test whether any yeast helicase is involved in 5’ strand resection we surveyed the role of Srs2, Sgs1, Rrm3 and Mph1 DNA helicases in end resection. In this initial screen only two probes were used, one located immediately next to the break (MAT) to monitor the rate of initiation of resection, and the other located 28 kb away from the break (FEN2) that allowed us to follow the rate of long-range resection. In all but one mutant, the rates of resection initiation were identical to those in wild-type cells (data not shown). In an sgs1Δ mutant, initiation of resection at MAT was the same as in wild-type cells. However, resection at FEN2 was very slow. We used additional probes to detect resection beyond 3 kb, 10 kb and 27–28 kb on both sides of the break. For all probes the average rate of resection was markedly reduced by about four-fold to about 1 kb/h (Figure 2A–B). Moreover the efficiency of resection was also dramatically reduced as only about 40% of cells processed the 5’ strand beyond 28 kb. Sgs1 forms a complex with Top3 and Rmi1 (hereafter called the STR complex) and acts together in several distinct DNA transactions (Chang et al., 2005; Chen and Brill, 2007; Fricke et al., 2001; Gangloff et al., 1994; Mullen et al., 2005). A similar complex was described between human orthologs called BLM/TopoIIIα/BLAP75 or BTB complex (Raynard et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2000; Yin et al., 2005). We therefore tested whether TOP3- and RMI1-deficient cells show defects in 5’ strand resection comparable to that in the sgs1Δ mutant. Both top3Δ and sgs1Δ top3Δ can initiate resection but are equally defective in long-range resection at 5’ strands (Figure S1). Also the rmi1Δ mutant is defective in resection (data not shown). We conclude that the STR complex is required for a wild-type rate (4.4 kb/h) but not for the initiation of resection.

Figure 2. Sgs1 helicase is required for normal rate of DSB end resection.

(A) Southern blot analysis of 5’ strand resection in sgs1Δ cells. (B) Plot demonstrating percentage of unprocessed 5’ strand for each EcoRI site in wild-type (black line) and sgs1Δ cells (red line). (C) Analysis of resection in sgs1Δ cells carrying a centromeric plasmid with either wild-type or helicase mutant genes of SGS1.

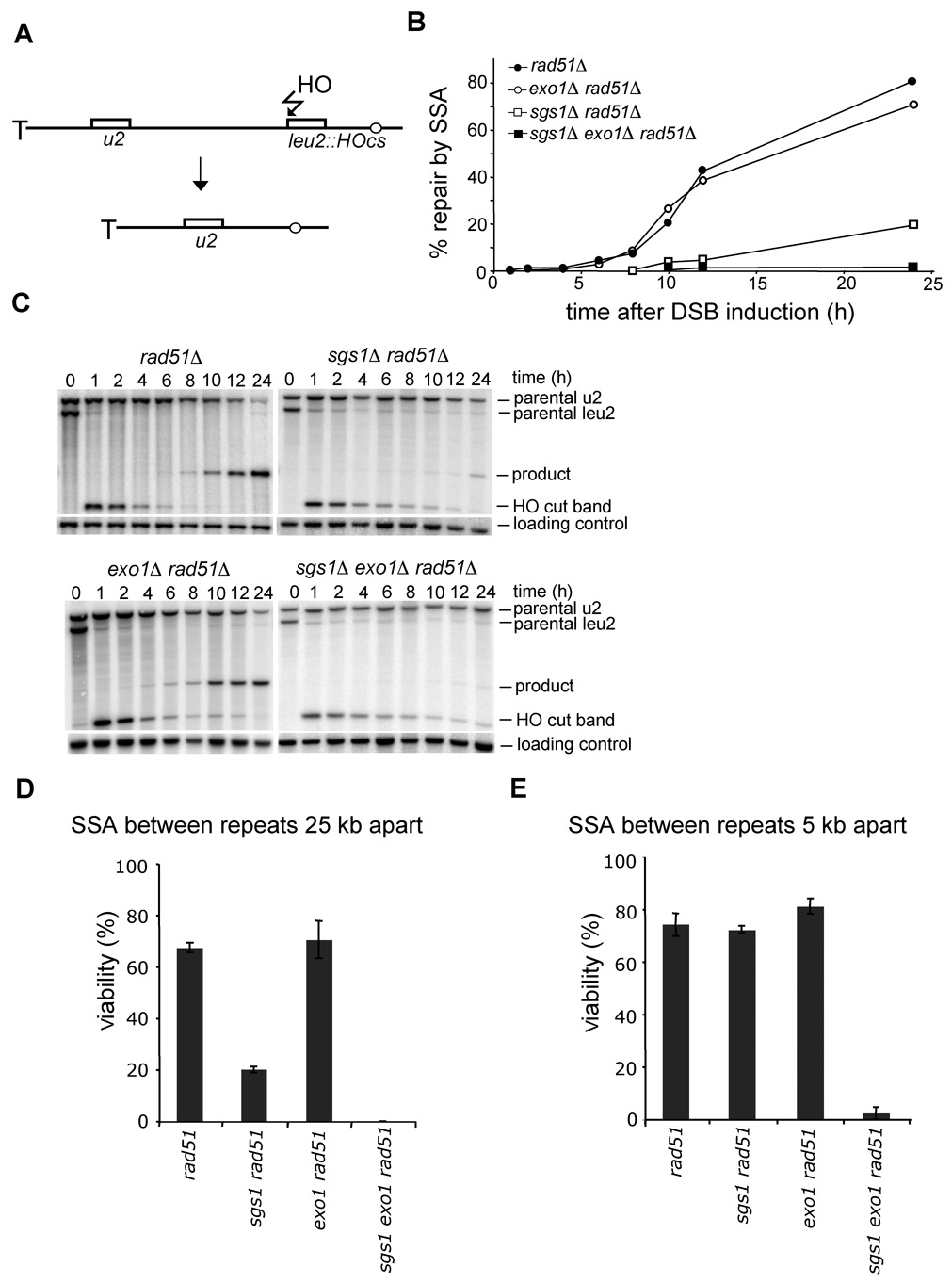

Single strand annealing between distant repeats is defective in sgs1Δ cells

To rule out the possibility that the observed resection defect in sgs1Δ is specific for a particular locus or assay that we employed, we tested whether sgs1Δ cells are proficient in single strand annealing (SSA) between partial leu2 gene repeats located 25 kb apart from each other on the left arm of the chromosome III. In this assay, the HO recognition site is located next to leu2 gene and the second leu2 sequence is inserted 25 kb downstream at HIS4 locus. Therefore 25 kb of resection is required for SSA to occur (Figure 3A; Vaze et al., 2002). To exclude the contribution of break-induced replication (BIR) to DSB repair by which one repeat invades the other repeat and copies the distal part of the chromosome, we measured the repair frequency in the absence of RAD51. Rad51 is essential for BIR but dispensable for SSA (Davis and Symington, 2004; VanHulle et al., 2007). We reasoned that if Sgs1 is involved in resection, especially for regions further from the break, SSA between repeats separated by 25 kb should depend strongly on Sgs1. Indeed in rad51Δ sgs1Δ mutant cells SSA is dramatically reduced and product formation is delayed substantially (Figure 3B–D). The time required for product formation is congruent with earlier estimates of a 1 kb/h rate of resection in an sgs1Δ mutant (Figure 2A–B). Together these results confirm that sgs1Δ cells are defective in 5’ strand resection but not in the initial processing of the breaks.

Figure 3. Sgs1 promotes SSA between distant repeats.

(A) Scheme representing SSA assay between partial LEU2 gene repeats (Vaze et al., 2002). (B) Kinetics of SSA product formation in wild-type and mutant cells lacking one or more genes. (C) Southern blot analysis of SSA in wild type and indicated mutants. (D–E) Viability of mutants on galactose-containing plates, where an HO break is repaired by SSA between repeats separated by 25 kb (D) or 5 kb (E).

The helicase domain of Sgs1 is required for proper DSB end resection

To determine whether the helicase activity of Sgs1 is required for 5’ resection, we expressed the wild-type SGS1 gene or sgs1 mutant derivatives with a deletion or single amino acid substitution in the helicase domain (sgs1-ΔC795 or sgs1-hd) in sgs1Δ cells. As shown in Figure 2C, only wild-type SGS1 was able to restore the normal resection rate, demonstrating that Sgs1 helicase activity is required for efficient removal of the 5’ strand.

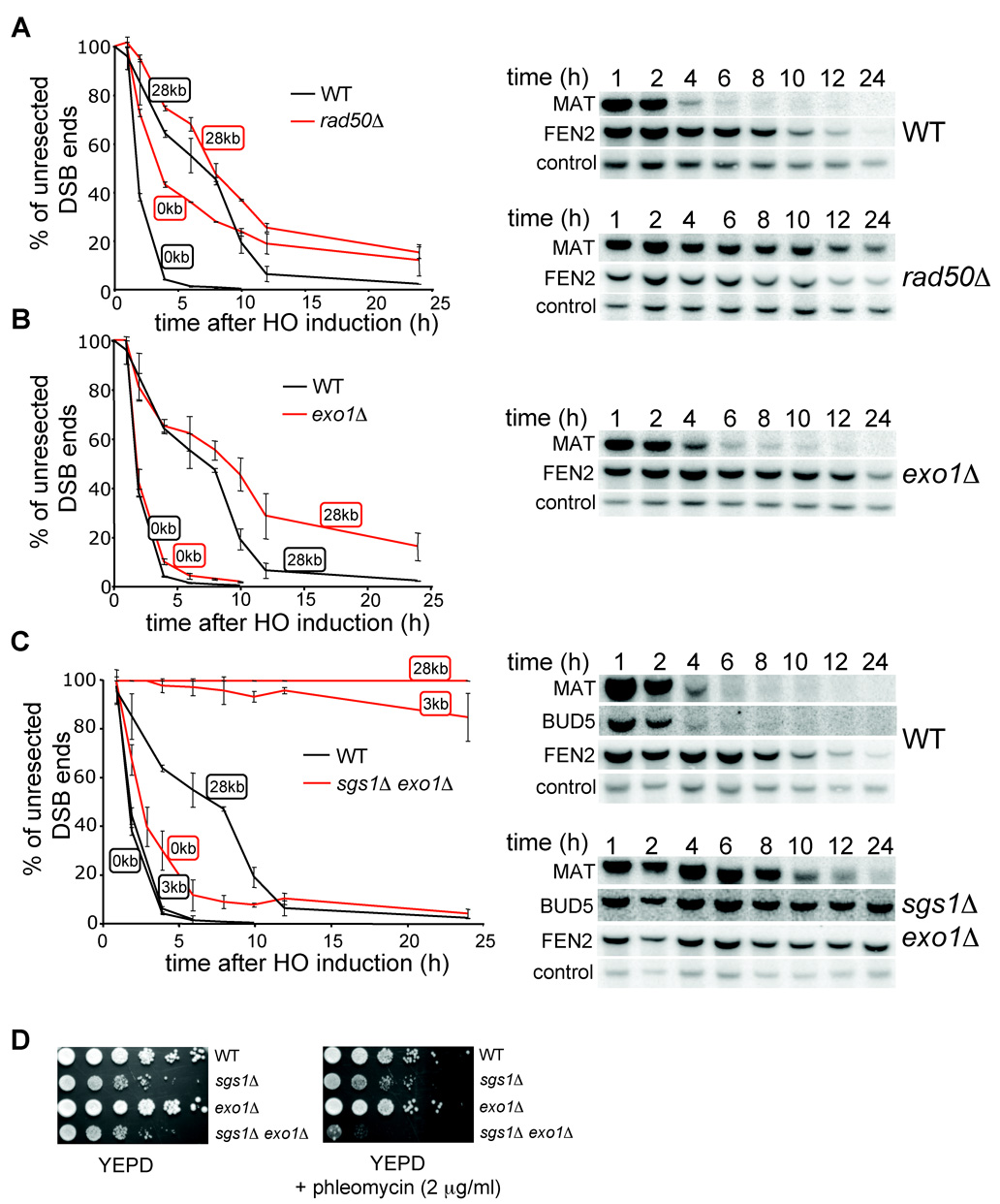

The MRX complex functions only in the initiation of resection

Sgs1 is a DNA helicase that unwinds a 5’ strand and provides a substrate for a nuclease(s). Previously the MRX complex and Exo1 were shown to be involved in 5’ strand resection. Therefore we decided to test whether any of these factors is important for long-range processing of DSB ends along with Sgs1. We measured resection rates in a rad50Δ mutant. Consistent with previous reports (Ivanov et al., 1994), resection at the MAT locus is slower in a rad50Δ mutant (Figure 4A). If the MRX complex is required for 5’ strand processing further away from the break, we anticipated very slow 5’ strand degradation at a distance of 28 kb from the break. However, we did not observe a significant difference between rad50Δ and wild-type cells in resection at 28 kb, except that a fraction of rad50Δ cells (about 20%) never initiated resection and therefore failed to process the 5’ strand away from the break (Figure 4A). The same results were observed in mre11Δ cells (Figure S2). We conclude that cells deficient in the MRX complex are impaired in the initiation of 5’ resection, but those that successfully initiate resection still process the 5’ strand at the wild-type rate. Therefore, MRX is not the nuclease that processes 5’ strands unwound by Sgs1.

Figure 4. Sgs1 and Exo1 can process 5’ strands independently.

Kinetics of resection in rad50Δ (A), exo1Δ (B), and sgs1Δ exo1Δ mutant cells (C) compared to wild-type cells. Southern blot analysis is shown. (D) Sensitivity of wild-type, sgs1Δ, exo1Δ and sgs1Δ exo1Δ cells to phleomycin.

Sgs1 and Exo1 can act independently to remove the 5’ strand

To determine whether Exo1 is the enzyme that processes the 5’ strands unwound by Sgs1, we measured the resection rate in an exo1Δ mutant. Initiation of resection in exo1Δ cells is comparable to that in wild-type cells. The kinetics and efficiency of SSA between repeats that are separated by 25 kb were identical in rad51Δand exo1Δ rad51Δ cells (Figure 3C–D). In addition resection measured at 28 kb from the DSB in exo1Δ cells was reduced, however less dramatically than in sgs1Δ cells (Figure 4B). These results indicate that Exo1 is not the major nuclease that processes 5’ strands or that there is another equally efficient nuclease. We further constructed the sgs1Δ exo1Δ strain and measured the 5’ strand resection rate. As shown in Figure 4C, the processing of DSB ends in sgs1Δ exo1Δ is substantially slower and much less efficient than that in each single mutant. Only about 5–10% of cells resect the 5’ strand beyond the EcoRI site located 3 kb away from the break (BUD5 probe). The results demonstrate that deletion of SGS1 and EXO1 almost completely eliminates 5’ strand degradation. However, these factors are dispensable for the initial resection of the break. Furthermore, sgs1Δ exo1Δ rad51Δ cells almost never complete SSA between repeats that are 25 kb or even 5 kb apart (Figure 3C–E). Along with the synergistic effect of sgs1Δ exo1Δ on phleomycin-induced damage tolerance (Figure 4D), we conclude that Sgs1 and Exo1 play a redundant role in DSB repair: 5’ end resection. We also conclude that besides Exo1, another nuclease exists to process the 5’ strand together with the Sgs1 helicase.

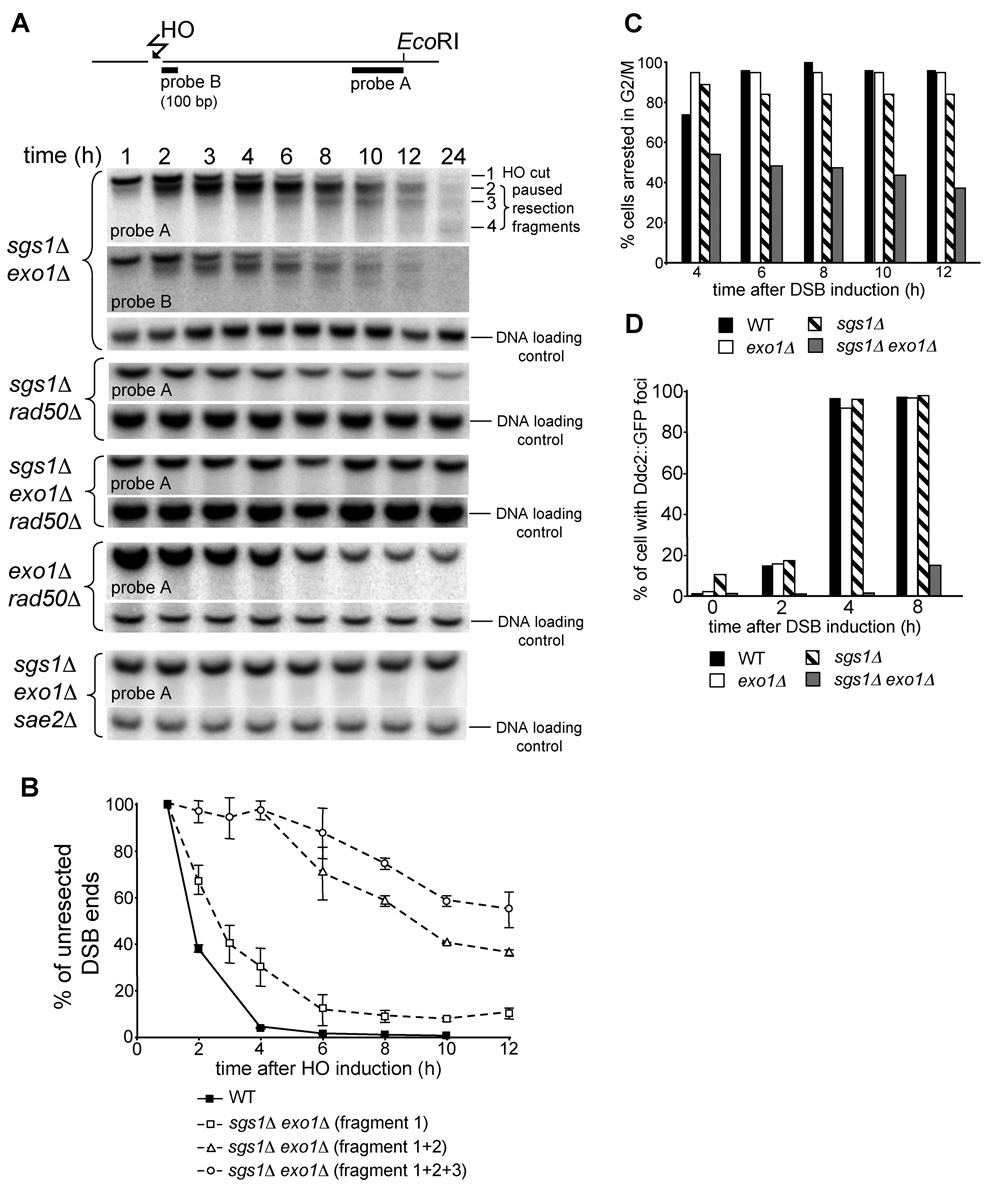

Resection in sgs1Δ exo1Δ is limited to the vicinity of DSB ends and depends on the MRX complex and Sae2

The sgs1Δ exo1Δ mutant still sustains slow and limited 5’ resection at the vicinity of the break, as the HO-cut fragments disappeared into diffused bands (Figure 4C). To analyze these diffuse bands in more detail, we separated EcoRI fragments for a longer time (Figure 5A). Interestingly we observed several bands accumulated over time below the initial HO cut bands that migrate in increments of about 100 bp. The additional bands are observed on both sides of the break. These smaller DNA fragments observed in the sgs1Δ exo1Δ double mutant could result when either 3’ end degradation or 5’ strand resection pauses at discrete sites. To distinguish between these two possibilities we used a 100 bp probe specific to the first 100 bp immediately adjacent to the break (probe B) (Figure 5A). The pattern and relative intensity of DNA fragments detected by this probe are identical to DNA fragments detected with a probe specific to 400 bp at the other end of the HO-cut fragment (probe A). We conclude that 3’ ends are stable and that enzymatic processing of DSB ends in the absence of both SGS1Δ and EXO1Δ pauses at discrete sites. We further measured how much ssDNA is created over time on one side of a DSB in the sgs1Δ exo1Δ mutant. The first 100 nucleotides is removed quickly, but after 4–6 h after HO induction only 30% or 10% of cells processed DSB ends beyond 100 or 200 nucleotides, respectively (Figure 5B). Such limited resection with the unique 100 bp pausing is also detected in rmi1Δ exo1Δ and top3Δ rmi1Δ strains (Figure S3).

Figure 5. Analysis of resection and G2/M DNA damage checkpoint arrest in sgs1Δ exo1Δ cells.

(A) Position of two probes with respect to the DSB and EcoRI sites used to analyze 5’ strand processing in sgs1Δ exo1Δ cells. Southern blot analysis of 5’ strand resection in indicated mutants. Position of HO cut band (DNA fragment 1) and additional bands (DNA fragments 2 to 4) observed in sgs1Δ exo1Δ cells is indicated. (B) Plot demonstrating kinetics of resection in wild-type and sgs1Δ exo1Δ cells. Pixel intensities of the signal corresponding to the unprocessed HO cut band separately or added to the signal of the band(s) corresponding to paused degradation are presented. (C) Analysis of G2/M arrest after induction of the HO break in indicated mutants. (D) Number of cells forming Ddc2 foci after DSB induction was analyzed in indicated mutant and wild-type cells.

We discovered that STR- and Exo1-independent 5’ resection depends almost entirely on the MRX complex and Sae2. In sgs1Δ rad50Δ, exo1Δ rad50Δ, exo1Δ sgs1Δ rad50Δ and exo1Δ sgs1Δ sae2Δ mutants the bands corresponding to smaller HO cleavage products are never formed and in very slow growing triple mutants resection of the HO break is almost undetectable (Figure 5A and Figure S4). The results indicate that the MRX complex and Sae2 are primarily responsible for resecting close to the break (Figure 4A). Furthermore, resection close to the break in rad50Δ sgs1Δ and rad50Δ exo1Δ double mutant cells is even more delayed than in a rad50Δ single mutant, suggesting that in the absence of the MRX complex both Sgs1 and Exo1 can still initiate limited DSB end processing.

Mutants with impaired 5’ strand resection show decreased gene conversion efficiency

To test whether resection limited to the vicinity of DSB ends in sgs1Δ exo1Δ is sufficient for gene conversion, we used an ectopic recombination assay between MATa sequence located on chromosome V and a MATa-inc sequence located on chromosome III (Ira et al., 2003). Gene conversion in the sgs1Δ exo1Δ double mutant was reduced by about one-third when compared to each single mutant, demonstrating that limited resection in sgs1Δ exo1Δ partially impairs DSB repair via gene conversion (Figure S4). A relatively high level of repair in sgs1Δ exo1Δ cells is not surprising given that 100–200 bp of homology is sufficient for homologous recombination (Ira and Haber, 2002; Jinks-Robertson et al., 1993) and the resection observed is capable of producing up to 1 kb of ssDNA on each side of the break. Similarly, gene conversion is decreased in the rad50Δ sgs1Δ and rad50Δ exo1Δ double mutants that show decreased initiation of resection (Figure S4). Gene conversion is completely abolished in exo1Δ sgs1Δ rad50Δ cells where almost no resection is observed (Figure S4).

G2/M checkpoint arrest in response to a single DSB is impaired in sgs1Δ exo1Δ cells

To examine whether the length of ssDNA in the sgs1Δ exo1Δ mutant is sufficient to trigger the G2/M DNA damage checkpoint, we compared the cell cycle progression after inducing a single unrepairable DSB in wild-type, exo1Δ, sgs1Δ and sgs1Δ exo1Δ cells. Cell cycle arrest was monitored microscopically for 12 h in micromanipulated unbudded G1 cells on YEP-galactose plates as described previously (Lee et al., 1998). 90% of cells from the wild-type and each single mutant strain were arrested within 4–6 h at G2/M and remained arrested for at least 12 h. In contrast sgs1Δ exo1Δ double mutant cells did not arrest efficiently at G2/M (Figure 5C). This result suggests that limited resection in the sgs1Δ exo1Δ double mutant impairs the G2/M DNA damage checkpoint. To confirm this result we verified the localization of the upstream checkpoint protein Ddc2::GFP to the DSB using fluorescence microscopy. Ddc2/Mec1 is required for DNA damage checkpoint arrest (reviewed in Harrison and Haber, 2006), binds to RPA-coated ssDNA and was shown previously to localize to DNA damage foci (Melo et al., 2001). Figure 5D shows that Ddc2 foci appear in most of the wild-type and sgs1Δ or exo1Δ single mutant cells within 4 h after HO break induction. In sgs1Δ exo1Δ double mutant cells however we do not observe Ddc2 foci for 4 h after break induction where only about 100 bp of ssDNA was accumulated. Later 8 h after break induction about 20% of sgs1Δ exo1Δ cells have Ddc2 foci. This result suggests that the slow formation of ssDNA in the absence of Sgs1 and Exo1 delays DNA damage checkpoint activation.

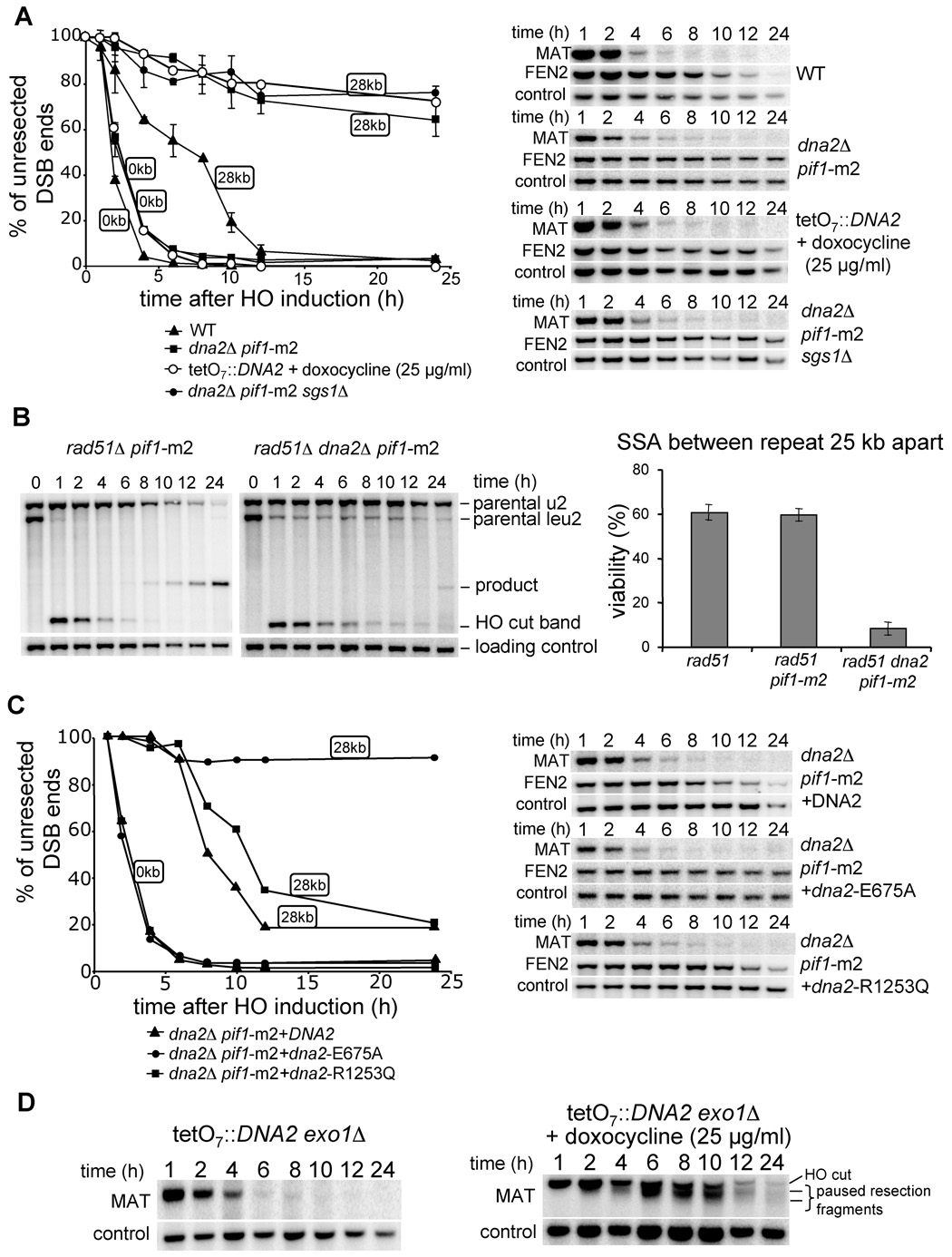

A dna2Δ mutant is severely defective in resection

Our results suggest that besides Exo1 yet another nuclease processes 5’ strands. Recently in a screen for proteins recruited to DSBs we discovered Dna2 (W.H.C. and G.I., unpublished data). Dna2 is a nuclease/helicase conserved among all eukaryotes that has been implicated in Okazaki fragment processing (Bae et al., 2001; Budd and Campbell, 1995). Several hypomorphic dna2 mutants were shown to be sensitive to DNA damage induced by MMS and γ-irradiation (Budd and Campbell, 2000; Formosa and Nittis, 1999). However the specific function of Dna2 in DNA repair has not been previously identified. Although DNA2 is an essential gene, deletion of another helicase, PIF1, suppresses the lethality of dna2Δ (Budd et al., 2006). Saccharomyces PIF1 encodes two isoforms of a protein transcribed from different initiating methionine codons (Schulz and Zakian, 1994; Zhou et al., 2000) to either catalyze telomere length regulation or promote mitochondrial DNA integrity. In particular, a pif1-m2 mutation allows cells to produce pif1-m2 protein that retains only mitochondrial localization (Schulz and Zakian, 1994). Importantly, the pif1-m2 mutation suppresses the lethality of dna2Δ. We thus evaluated the resection rate in both pif1-m2 and dna2Δ pif1-m2 strains. In the pif1-m2 mutant both initiation and long-range resection occur as efficiently as in wild-type cells (Figure S5). In a dna2Δ pif1-m2 double mutant, initiation of resection is comparable to wild-type cells but long-range resection is very defective (Figure 6A). To confirm that Dna2 is required to produce long ssDNA, and that the defect in resection is not limited to one locus, we again used the SSA assay where repeats flanking a DSB are separated by 25 kb. As expected, the double mutant pif1-m2 rad51Δ was as proficient in SSA as rad51Δ, whereas the triple mutant pif1-m2 rad51Δ dna2Δ was very defective in SSA (~10% repair) (Figure 6B). The defect in SSA was slightly more severe than that observed in sgs1Δ rad51Δ (~17% repair), suggesting that the alternative Exo1-dependent resection pathway is more active in sgs1Δ than in dna2Δ or that Dna2 has an additional role in DSB repair. We conclude that Dna2 likely corresponds to the second nuclease besides Exo1 responsible for the formation of long ssDNA tails at a DSB.

Figure 6. Dna2 nuclease processes the 5’ strand at a DSB.

(A) Southern blot analysis and kinetics of 5’ strand resection in pif1-m2 dna2Δ, pif1-m2 dna2Δ sgs1Δ and TetO7 ::TATA::DNA2 cells compared to wild-type cells. (B) Southern blot analysis and viability in the SSA assay in indicated mutants. (C) Southern blot analysis and kinetics of 5’ strand resection in pif1-m2 dna2Δ supplemented with a plasmid carrying either the wild-type DNA2 gene, or a point mutation eliminating nuclease (E675A) or helicase activity (R1253Q). (D) Southern blot analysis of 5’ strand resection in the absence of both Exo1 and Dna2 nucleases.

Exo1 promotes resection in the absence of Dna2

To verify the relationship of Sgs1 and Dna2 with respect to DSB end resection we constructed the triple mutant sgs1Δ dna2Δ pif1-m2, and found that the initiation of resection is comparable to wild-type cells whereas progression of resection is severely impaired (Figure 6A). Importantly the defects in resection in pif1-m2 dna2Δ and sgs1Δ dna2Δ pif1-m2 cells are comparable, suggesting that Sgs1 and Dna2 may work in a common pathway to produce long ssDNA. Epistasis between Dna2 and Exo1 could not be established since the triple mutant dna2Δ exo1Δ pif1-m2 is not viable. Analysis of 150 tetrads from a dna2/DNA2 EXO1/exo1 pif1-m2/PIF1 diploid strain did not yield a single dna2Δ exo1Δ pif1-m2 viable colony. Instead we constructed DNA2 under the regulatable TetO7 promoter in which DNA2 expression is shut off by the addition of doxocycline to the growth media (Mnaimneh et al., 2004). In the presence of 25 µg/ml doxocycline the TetO7 ::TATA::DNA2 strain becomes inviable (data not shown) and the resection rate is as slow as in dna2Δ pif1-m2 (Figure 6A). We then constructed the TetO7 ::TATA::DNA2 exo1Δ strain and tested the resection rate in the presence and absence of doxocycline. Strikingly we observed very slow resection in the presence of doxocycline, with the characteristic pattern of additional bands below the initial HO cut band (Figure 6D) previously observed in the double mutant sgs1Δ exo1Δ (Figure 5A). Altogether these data show that Exo1 and Dna2 are the two nucleases with redundant functions in DSB end resection.

The nuclease domain of Dna2 is required for processing DSB ends

Dna2 may function in 5’ end resection as a nuclease and/or helicase. To verify which of these two activities is responsible for resection, we constructed dna2Δ pif1-m2 strains harboring plasmids expressing the wild-type DNA2 gene or mutant dna2 with a single amino acid substitution in either the helicase domain (dna2-R1253Q) or the nuclease domain (dna2-E675A). These mutations were previously shown to eliminate the helicase and nuclease activities, respectively (Budd et al., 2000; Formosa and Nittis, 1999; Lee et al., 2000). We then determined the resection rates in these mutants and found that expression of either wild-type DNA2 or the helicase-deficient dna2-R1253Q mutant restores 5’ resection, whereas dna2-E675A does not (Figure 6C). Therefore, Dna2 nuclease activity is important for 5’ strand resection.

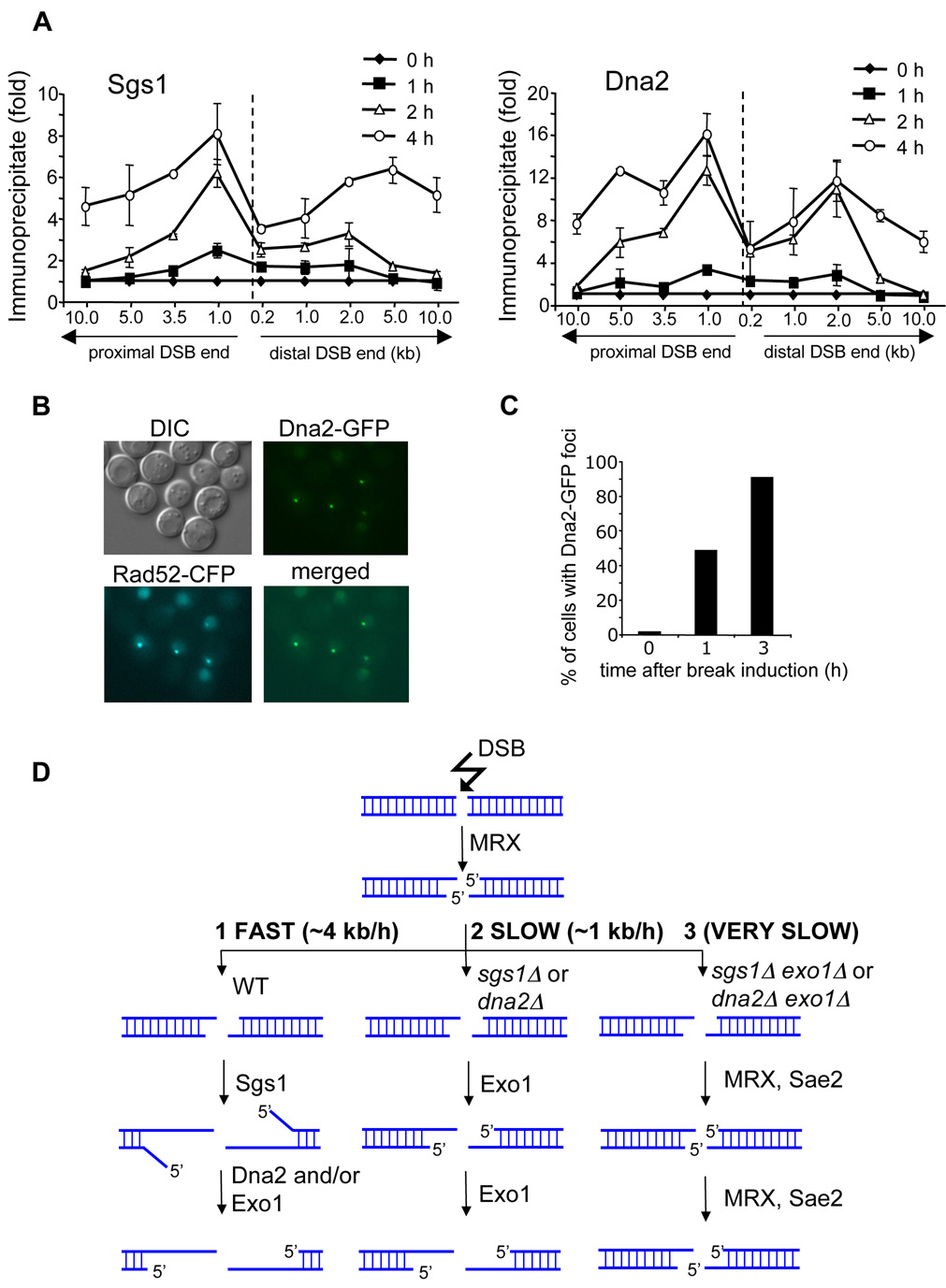

Dna2 and Sgs1 are recruited to DSB ends and spread away from DSB ends as resection progresses

We identified two new factors required for normal DSB end resection: Dna2 and Sgs1. We anticipated that both proteins are recruited to the break early and are propagated away from DSB ends as resection progresses. Using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) we monitored Sgs1 and Dna2 recruitment to DSB ends. We demonstrate that both proteins are rapidly recruited to the region immediately adjacent to the DSB ends within 1 h after break induction and gradually move 5 to 10 kb away from the break at 4 h after DNA cleavage (Figure 7A). Dna2 recruitment was also followed using fluorescence microscopy. After HO break induction Dna2-GFP forms nuclear foci that overlap with Rad52 foci (Figure 7B–C). Consistent with our ChIP data almost 50% of cells have a single Dna2-GFP focus at 1 h after break induction. Notably, the binding patterns of Sgs1 and Dna2 are substantially different from that of the MRX complex whose recruitment is almost exclusively limited to the sequence right next to the DNA break (Shroff et al., 2004). Therefore, the results further support our model that the role of MRX in resection is restricted to the very ends of a DSB, whereas Sgs1 and Dna2 function to extend 3’ single strands.

Figure 7. Recruitment of Dna2 and Sgs1 to a DSB and a model of 5’ strand resection at DSBs.

(A) Localization of Sgs1 and Dna2 to DSBs at the MAT locus estimated by ChIP before and 1, 2 and 4 h after break induction. IP represents the ratio of the Sgs1p or Dna2p IP PCR signal before and after HO induction, normalized by the PCR signal of the PRE1 control. A dotted line indicates the location of the HO-induced break. (B) Dna2-GFP foci formed after HO break induction colocalize with Rad52-CFP foci. (C) Number of cells with Dna2-GFP foci before and 1 and 3 h after break induction. (D) Model representing three different 5’ strand resection pathways at a DSB with various processivity.

Discussion

We identified multiple pathways in the initial step of DSB-induced homologous recombination, 5’ strand resection. A novel comprehensive model of DSB end processing is presented in Figure 7D.

The Sgs1 helicase catalyzes DSB resection

Wild-type cells resect DSB ends at an average rate of 4.4 kb/h. This rapid resection rate depends on the STR complex (Sgs1, Top3, Rmi1) (Figure 7D). Sgs1 encodes a 3’-5’ helicase, a member of the highly conserved RecQ family of helicases with crucial roles in the maintenance of genome stability. Multiple functions in DNA recombination and replication were assigned to RecQ helicases including resolution of recombination intermediates, disruption of Rad51 nucleoprotein filaments and stabilization of stalled replication forks (reviewed in Bachrati and Hickson, 2008; Branzei and Foiani, 2007). Interestingly all components of the STR complex are required for an optimal level of resection. Rmi1 stimulates the association of Top3 and Sgs1 with ssDNA and may be required for proper Sgs1 complex recruitment (Chen and Brill, 2007). Top3 may remove supercoiled DNA formed by the Sgs1 helicase during resection. Deletion of any component of the yeast STR complex or human BTB complex elevates crossover recombination. Most likely these complexes suppress crossover formation by dissolution of double Holliday junction intermediates (Wu and Hickson, 2003). It remains to be determined whether resection rate influences crossover recombination.

Dna2 and Exo1 nucleases process 5’ strands at a DSB

We identified two nucleases, Dna2 and Exo1, with redundant activities in processing DSB ends. DNA2 is an essential gene carrying two conserved domains: a RecB family nuclease motif (Aravind et al., 2000; Bae et al., 1998) in the middle of the protein and a superfamily I helicase domain at the C terminus (Budd et al., 1995). The nuclease domain alone is required for 5’ strand processing of DSBs. Dna2 was shown previously to clip off long 5’ flaps even when they are coated with RPA, a function not shared with the other known 5’ flap nuclease, Rad27 (Bae et al., 2001). For this reason, the role of Dna2 was previously assigned to the processing of long Okazaki fragments.

While both Exo1 and Dna2 nucleases may process 5’ strands unwound by Sgs1, we favor Dna2 in this role for two reasons. First, the resection defect and SSA deficiency observed in sgs1Δ and dna2Δ mutants are comparable in magnitude and epistatic. Second, long-range resection in the absence of Sgs1 or Dna2 depends on Exo1. This result implies that Dna2 does not contribute to resection in the absence of Sgs1 and vice versa. Alternatively, the combined activity of Dna2 and Exo1 may provide optimal processing of 5’ strands unwound by Sgs1 since even a single exo1Δ mutant shows a modest defect in the processing of DSB ends. Overexpression of EXO1 was shown to compensate partially for the growth defect of a dna2-1 mutant, supporting the model that these nucleases can process common substrates (Budd et al., 2000). Within the first 3 kb from the break site both Exo1 and Dna2 seem equally efficient in resection. Therefore it remains to be determined which of these two enzymes plays a more prominent role in resection close to the break in wild-type cells. DSB resection pathway choice may depend on the cell cycle stage as it has been demonstrated that resection is very tightly controlled during the cell cycle (Ira et al., 2004). Alternatively, the MRX complex that is specialized in the initiation of resection may modulate how a cell processes a DNA break by physical association with one of these factors. Indeed, Sgs1 physically interacts with the MRX complex (Chiolo et al., 2005).

MRX and Sae2 initiate DSBs processing

Cells deficient in any component of the MRX/MRN complex or Sae2/CtIP in both yeast and mammals are defective in HO endonuclease- or γ-irradiation-induced DSB end processing. Unlike the rad50Δ and mre11Δ mutations, deletion of any other gene analyzed here by itself does not delay the initiation of 5’ strand resection, suggesting a unique role for the MRX complex in facilitating initial DSB resection. Accordingly, rad50Δ cells that managed to initiate resection catalyze subsequent 5’ strand processing at the wild-type rate. In mutants deprived of both Sgs1 (or Dna2) and Exo1, resection is limited to the very vicinity of the DSB and depends on the MRX complex and Sae2. Furthermore, MRX is recruited to unprocessed DSB ends, maintained at the break only for a short time immediately after DSB induction, and cannot be detected by ChIP further away from DSBs (Lisby et al., 2004; Shroff et al., 2004). This contrasts with Sgs1 and Dna2 which are recruited to DSB ends when they are initially processed, and both are propagated away from the break as resection progresses (Figure 7A–C). Together these data strongly suggest that the role of MRX and Sae2 in resection is limited to the very early stages of DSB repair (Figure 7D). DNA 5’ strands are processed there in a characteristic stepwise manner with a pause at about every 100 bp. It is possible that this represents transient initial 5’ resection intermediates which are quickly converted to longer ssDNA ends by Sgs1, Dna2 and Exo1 and are difficult to detect in wild-type cells. It remains to be determined whether Sae2 or Mre11 or both in a cooperative way are responsible for this unique 5’ strand processing (Lengsfeld et al., 2007).

Is the 5’ strand resection pathway conserved from bacteria to mammals?

In E. coli, aside from the major RecBCD-dependent pathway, there is a second pathway promoting recombination - RecF. In the RecF pathway, a combined activity of the RecQ helicase and the RecJ nuclease promotes formation of ssDNA (Amundsen and Smith, 2003). In higher eukaryotes there are multiple orthologues of the RecQ helicase, among which WRN was shown in X. laevis egg extracts to promote 5’ strand resection (Toczylowski and Yan, 2006). A nuclease that works together with the WRN helicase in DSB end resection has not yet been identified, but likely is a human Dna2 orthologue. Human Dna2 homologue was found to have biochemical features remarkably similar to its yeast counterpart (Kim et al., 2006; Masuda-Sasa et al., 2006).

Benefits and control of multiple pathways of 5’ strand processing

Yeast has multiple pathways to process 5’ strands at mitotic DSBs (Figure 7D). We showed that resection limited to the first 100–200 bp is enough to promote relatively efficient gene conversion. Why do cells then produce such long 3’ tails? The length of ssDNA formed during DSB-induced gene conversion is not known, however two lines of evidence suggest that at least several kb of ssDNA are formed on each DSB end. First, sequences 2–3 kb away from the break are used preferentially over sequences immediately next to the break for homology search and repair (Inbar and Kupiec, 1999). Second, strand invasion and new DNA synthesis primed by 3’ tails is observed about 1 to 2 h after DSB formation (White and Haber, 1990), suggesting that at least several kb of ssDNA must be formed given the observed rate of resection is 4.4 kb/h. Long 3’ tails produced by 5’ strand processing may facilitate quick and efficient DSB repair and robust DNA damage checkpoint activation. Furthermore, usage of short homology immediately adjacent to the break site rather than longer homologous sequences may increase the chances of recombination between short nonallelic repeats leading to chromosome translocations. Indeed in sgs1Δ mutants, increased ectopic recombination and recombination between short homeologous sequences was reported (Myung et al., 2001; Watt et al., 1996).

Multiple pathways probably allow cells to use specific processing for different types of DNA damage. DNA breaks in the middle of a chromosome or at telomere ends, and breaks during the mitotic or meiotic cell cycle all may require different processing. In E. coli, RecBCD processes DSBs whereas RecQ/RecJ is thought to play a more specialized role in processing spontaneous damage that yields single strand gaps (Courcelle et al., 2006; Hishida et al., 2004; Magner et al., 2007). In budding yeast, Exo1 was shown to generate ssDNA at stalled replication forks in checkpoint-deficient rad53Δ mutants (Cotta-Ramusino et al., 2005), whereas telomere chromosome ends are protected from Exo1 activity by the Ku70/Ku80 complex (Maringele and Lydall, 2002). It will be of great interest to define which 5’ resection pathways contribute to the formation ssDNA in meiotic cells or at telomeres, and how these processes are controlled in the cell cycle to achieve genetic integrity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains and plasmids

All strains used in this study are derivatives of JKM139 (hoΔ hml::ADE1 MATa hmr::ADE1 ade1 leu2–3, 112 lys5 trp1::hisG ura3–52 ade3::GAL10::HO). All strains and plasmids are listed in Supplemental Data.

DSB end resection analysis

5’ strand processing was determined in mutants compared to wild type at least three times in every experiment. DNA isolated by glass bead disruption using a standard phenol extraction method was digested with EcoRI and separated on 0.8% agarose gels. Southern blotting and hybridization with radiolabeled DNA probes was carried out as described previously (Church and Gilbert, 1985). Multiple DNA probes used for hybridization to detect 5’ strand resection beyond the EcoRI site, as well as the sequences of DNA primers used to prepare the probes by PCR are listed in Supplemental Procedures. Intensities of bands on Southern blots corresponding to probed DNA fragments were analyzed with ImageQuant TL (Amersham Biosciences). Quantities of DNA loaded on gels for each time point were normalized using either an APA1 or a TRA1 DNA probe. DSB end resection beyond each EcoRI site for each timepoint was estimated as a percentage of the signal intensity corresponding to the EcoRI fragment of interest 1 h after break induction.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Data includes Experimental Procedures, 5 figures and 2 tables.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to James Haber, Virginia Zakian, Steve Brill, Rodney Rothstein, and Judith Campbell for strains and plasmids and to Alma Papusha for technical support. We thank James Haber, Phil Hastings and Neil Hunter for critical comments on manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grants GM80600-02 (to G.I.) and GM071011 and Texas Advanced Research Program (to S.E.L.). The preliminary work was supported by GM20056 to J.E. Haber. S.E.L. is a scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Amundsen SK, Smith GR. Interchangeable parts of the Escherichia coli recombination machinery. Cell. 2003;112:741–744. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00197-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravind L, Makarova KS, Koonin EV. SURVEY AND SUMMARY: holliday junction resolvases and related nucleases: identification of new families, phyletic distribution and evolutionary trajectories. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:3417–3432. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.18.3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachrati CZ, Hickson ID. RecQ helicases: guardian angels of the DNA replication fork. Chromosoma. 2008;117:219–233. doi: 10.1007/s00412-007-0142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae SH, Bae KH, Kim JA, Seo YS. RPA governs endonuclease switching during processing of Okazaki fragments in eukaryotes. Nature. 2001;412:456–461. doi: 10.1038/35086609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae SH, Choi E, Lee KH, Park JS, Lee SH, Seo YS. Dna2 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae possesses a single-stranded DNA-specific endonuclease activity that is able to act on double-stranded DNA in the presence of ATP. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:26880–26890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branzei D, Foiani M. RecQ helicases queuing with Srs2 to disrupt Rad51 filaments and suppress recombination. Genes Dev. 2007;21:3019–3026. doi: 10.1101/gad.1624707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd ME, Campbell JL. A yeast gene required for DNA replication encodes a protein with homology to DNA helicases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1995;92:7642–7646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd ME, Campbell JL. The pattern of sensitivity of yeast dna2 mutants to DNA damaging agents suggests a role in DSB and postreplication repair pathways. Mutat. Res. 2000;459:173–186. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(99)00072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd ME, Choe W, Campbell JL. The nuclease activity of the yeast DNA2 protein, which is related to the RecB-like nucleases, is essential in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:16518–16529. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909511199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd ME, Choe WC, Campbell JL. DNA2 encodes a DNA helicase essential for replication of eukaryotic chromosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:26766–26769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd ME, Reis CC, Smith S, Myung K, Campbell JL. Evidence suggesting that Pif1 helicase functions in DNA replication with the Dna2 helicase/nuclease and DNA polymerase delta. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:2490–2500. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.7.2490-2500.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang M, Bellaoui M, Zhang C, Desai R, Morozov P, Delgado-Cruzata L, Rothstein R, Freyer GA, Boone C, Brown GW. RMI1/NCE4, a suppressor of genome instability, encodes a member of the RecQ helicase/Topo III complex. EMBO J. 2005;24:2024–2033. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CF, Brill SJ. Binding and activation of DNA topoisomerase III by the Rmi1 subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:28971–28979. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705427200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiolo I, Carotenuto W, Maffioletti G, Petrini JH, Foiani M, Liberi G. Srs2 and Sgs1 DNA helicases associate with Mre11 in different subcomplexes following checkpoint activation and CDK1-mediated Srs2 phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:5738–5751. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5738-5751.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church GM, Gilbert W. The genomic sequencing technique. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 1985;177:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerici M, Mantiero D, Lucchini G, Longhese MP. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Sae2 protein promotes resection and bridging of double strand break ends. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:38631–38638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508339200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotta-Ramusino C, Fachinetti D, Lucca C, Doksani Y, Lopes M, Sogo J, Foiani M. Exo1 processes stalled replication forks and counteracts fork reversal in checkpoint-defective cells. Mol. Cell. 2005;17:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courcelle CT, Chow KH, Casey A, Courcelle J. Nascent DNA processing by RecJ favors lesion repair over translesion synthesis at arrested replication forks in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:9154–9159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600785103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis AP, Symington LS. RAD51-dependent break-induced replication in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:2344–2351. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.6.2344-2351.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman-Lobell J, Haber JE. Removal of nonhomologous DNA ends in double-strand break recombination: the role of the yeast ultraviolet repair gene RAD1. Science. 1992;258:480–484. doi: 10.1126/science.1411547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formosa T, Nittis T. Dna2 mutants reveal interactions with Dna polymerase alpha and Ctf4, a Pol alpha accessory factor, and show that full Dna2 helicase activity is not essential for growth. Genetics. 1999;151:1459–1470. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.4.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricke WM, Kaliraman V, Brill SJ. Mapping the DNA topoisomerase III binding domain of the Sgs1 DNA helicase. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:8848–8855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009719200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuse M, Nagase Y, Tsubouchi H, Murakami-Murofushi K, Shibata T, Ohta K. Distinct roles of two separable in vitro activities of yeast Mre11 in mitotic and meiotic recombination. EMBO J. 1998;17:6412–6425. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangloff S, McDonald JP, Bendixen C, Arthur L, Rothstein R. The yeast type I topoisomerase Top3 interacts with Sgs1, a DNA helicase homolog: a potential eukaryotic reverse gyrase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:8391–8398. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison JC, Haber JE. Surviving the breakup: the DNA damage checkpoint. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2006;40:209–235. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.051206.105231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hishida T, Han YW, Shibata T, Kubota Y, Ishino Y, Iwasaki H, Shinagawa H. Role of the Escherichia coli RecQ DNA helicase in SOS signaling and genome stabilization at stalled replication forks. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1886–1897. doi: 10.1101/gad.1223804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inbar O, Kupiec M. Homology search and choice of homologous partner during mitotic recombination. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:4134–4142. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.4134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ira G, Haber JE. Characterization of RAD51-Independent Break- Induced Replication That Acts Preferentially with Short Homologous Sequences. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:6384–6392. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.18.6384-6392.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ira G, Malkova A, Liberi G, Foiani M, Haber JE. Srs2 and Sgs1-Top3 suppress crossovers during double-strand break repair in yeast. Cell. 2003;115:401–411. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00886-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ira G, Pellicioli A, Balijja A, Wang X, Fiorani S, Carotenuto W, Liberi G, Bressan D, Wan L, Hollingsworth NM, et al. DNA end resection, homologous recombination and DNA damage checkpoint activation require CDK1. Nature. 2004;431:1011–1017. doi: 10.1038/nature02964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov EL, Sugawara N, White CI, Fabre F, Haber JE. Mutations in XRS2 and RAD50 delay but do not prevent mating-type witching in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:3414–3425. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.5.3414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazayeri A, Falck J, Lukas C, Bartek J, Smith GC, Lukas J, Jackson SP. ATM- and cell cycle-dependent regulation of ATR in response to DNA double-strand breaks. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2006;8:37–45. doi: 10.1038/ncb1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinks-Robertson S, Michelitch M, Ramcharan S. Substrate length requirements for efficient mitotic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1993;13:3937–3950. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Kim HD, Ryu GH, Kim DH, Hurwitz J, Seo YS. Isolation of human Dna2 endonuclease and characterization of its enzymatic properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:1854–1864. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KH, Kim DW, Bae SH, Kim JA, Ryu GH, Kwon YN, Kim KA, Koo HS, Seo YS. The endonuclease activity of the yeast Dna2 enzyme is essential in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:2873–2881. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.15.2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SE, Bressan DA, Petrini JH, Haber JE. Complementation between N-terminal Saccharomyces cerevisiae mre11 alleles in DNA repair and telomere length maintenance. DNA Repair (Amst) 2002;1:27–40. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(01)00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SE, Moore JK, Holmes A, Umezu K, Kolodner RD, Haber JE. Saccharomyces Ku70, mre11/rad50 and RPA proteins regulate adaptation to G2/M arrest after DNA damage. Cell. 1998;94:399–409. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81482-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengsfeld BM, Rattray AJ, Bhaskara V, Ghirlando R, Paull TT. Sae2 is an endonuclease that processes hairpin DNA cooperatively with the Mre11/Rad50/Xrs2 complex. Mol. Cell. 2007;28:638–651. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisby M, Barlow JH, Burgess RC, Rothstein R. Choreography of the DNA damage response: spatiotemporal relationships among checkpoint and repair proteins. Cell. 2004;118:699–713. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorente B, Symington LS. The Mre11 nuclease is not required for 5' to 3' resection at multiple HO-induced double-strand breaks. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:9682–9694. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9682-9694.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magner DB, Blankschien MD, Lee JA, Pennington JM, Lupski JR, Rosenberg SM. RecQ promotes toxic recombination in cells lacking recombination intermediate-removal proteins. Mol. Cell. 2007;26:273–286. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maringele L, Lydall D. EXO1-dependent single-stranded DNA at telomeres activates subsets of DNA damage and spindle checkpoint pathways in budding yeast yku70Delta mutants. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1919–1933. doi: 10.1101/gad.225102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda-Sasa T, Imamura O, Campbell JL. Biochemical analysis of human Dna2. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:1865–1875. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo JA, Cohen J, Toczyski DP. Two checkpoint complexes are independently recruited to sites of DNA damage in vivo. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2809–2821. doi: 10.1101/gad.903501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mnaimneh S, Davierwala AP, Haynes J, Moffat J, Peng WT, Zhang W, Yang X, Pootoolal J, Chua G, Lopez A, et al. Exploration of essential gene functions via titratable promoter alleles. Cell. 2004;118:31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau S, Ferguson JR, Symington LS. The nuclease activity of Mre11 is required for meiosis but not for mating type switching, end joining, or telomere maintenance. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:556–566. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen JR, Nallaseth FS, Lan YQ, Slagle CE, Brill SJ. Yeast Rmi1/Nce4 controls genome stability as a subunit of the Sgs1-Top3 complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:4476–4487. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.11.4476-4487.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myung K, Datta A, Chen C, Kolodner RD. SGS1, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae homologue of BLM and WRN, suppresses genome instability and homeologous recombination. Nat. Genet. 2001;27:113–116. doi: 10.1038/83673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale MJ, Pan J, Keeney S. Endonucleolytic processing of covalent protein-linked DNA double-strand breaks. Nature. 2005;436:1053–1057. doi: 10.1038/nature03872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paull TT, Gellert M. The 3' to 5' exonuclease activity of Mre 11 facilitates repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Mol. Cell. 1998;1:969–979. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raynard S, Bussen W, Sung P. A double Holliday junction dissolvasome comprising BLM, topoisomerase IIIalpha, and BLAP75. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:13861–13864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600051200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Filippo J, Sung P, Klein H. Mechanism of eukaryotic homologous recombination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008;77:229–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061306.125255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartori AA, Lukas C, Coates J, Mistrik M, Fu S, Bartek J, Baer R, Lukas J, Jackson SP. Human CtIP promotes DNA end resection. Nature. 2007;450:509–514. doi: 10.1038/nature06337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz VP, Zakian VA. The saccharomyces PIF1 DNA helicase inhibits telomere elongation and de novo telomere formation. Cell. 1994;76:145–155. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim EY, Hong SJ, Oum JH, Yanez Y, Zhang Y, Lee SE. RSC mobilizes nucleosomes to improve accessibility of repair machinery to the damaged chromatin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:1602–1613. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01956-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shroff R, Arbel-Eden A, Pilch D, Ira G, Bonner WM, Petrini JH, Haber JE, Lichten M. Distribution and dynamics of chromatin modification induced by a defined DNA double-strand break. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:1703–1711. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spies M, Kowalczykowski S. Homologous recombination by RecBCD and RecF pathways. In: Higgins NP, editor. The Bacterial Chromosome. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 2005. pp. 389–403. [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Treco D, Szostak JW. Extensive 3'-overhanging, single-stranded DNA associated with the meiosis-specific double-strand breaks at the ARG4 recombination initiation site. Cell. 1991;64:1155–1161. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90270-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symington LS. Role of RAD52 epistasis group genes in homologous recombination and double-strand break repair. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2002;66:630–670. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.4.630-670.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toczylowski T, Yan H. Mechanistic analysis of a DNA end processing pathway mediated by the Xenopus Werner syndrome protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:33198–33205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605044200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo KM, Yuan SS, Lee EY, Sung P. Nuclease activities in a complex of human recombination and DNA repair factors Rad50, Mre11, and p95. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:21447–21450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.21447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubouchi H, Ogawa H. A novel mre11 mutation impairs processing of double-strand breaks of DNA during both mitosis and meiosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:260–268. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubouchi H, Ogawa H. Exo1 roles for repair of DNA double-strand breaks and meiotic crossing over in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2000;11:2221–2233. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.7.2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usui T, Ohta T, Oshiumi H, Tomizawa J, Ogawa H, Ogawa T. Complex formation and functional versatility of Mre11 of budding yeast in recombination. Cell. 1998;95:705–716. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81640-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Attikum H, Fritsch O, Hohn B, Gasser SM. Recruitment of the INO80 complex by H2A phosphorylation links ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling with DNA double-strand break repair. Cell. 2004;119:777–788. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanHulle K, Lemoine FJ, Narayanan V, Downing B, Hull K, McCullough C, Bellinger M, Lobachev K, Petes TD, Malkova A. Inverted DNA repeats channel repair of distant double-strand breaks into chromatid fusions and chromosomal rearrangements. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:2601–2614. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01740-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaze M, Pellicioli A, Lee S, Ira G, Liberi G, Arbel-Eden A, Foiani M, Haber J. Recovery from checkpoint-mediated arrest after repair of a double- strand break requires srs2 helicase. Mol. Cell. 2002;10:373. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00593-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt PM, Hickson ID, Borts RH, Louis EJ. SGS1, a homologue of the Bloom's and Werner's syndrome genes, is required for maintenance of genome stability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1996;144:935–945. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.3.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White CI, Haber JE. Intermediates of recombination during mating type switching in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1990;9:663–673. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08158.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Davies SL, North PS, Goulaouic H, Riou JF, Turley H, Gatter KC, Hickson ID. The Bloom's syndrome gene product interacts with topoisomerase III. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:9636–9644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Hickson ID. The Bloom's syndrome helicase suppresses crossing over during homologous recombination. Nature. 2003;426:870–874. doi: 10.1038/nature02253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin J, Sobeck A, Xu C, Meetei AR, Hoatlin M, Li L, Wang W. BLAP75, an essential component of Bloom's syndrome protein complexes that maintain genome integrity. EMBO J. 2005;24:1465–1476. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Monson EK, Teng SC, Schulz VP, Zakian VA. Pif1p helicase, a catalytic inhibitor of telomerase in yeast. Science. 2000;289:771–774. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou L, Elledge SJ. Sensing DNA damage through ATRIP recognition of RPA-ssDNA complexes. Science. 2003;300:1542–1548. doi: 10.1126/science.1083430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Data includes Experimental Procedures, 5 figures and 2 tables.