Abstract

The standard systemic treatment for prostate cancer (PCa) is androgen ablation, which causes tumor regression by inhibiting activity of the androgen receptor (AR). Invariably, PCa recurs with a fatal androgen-refractory phenotype. Importantly, the growth of androgen-refractory PCa remains dependent on the AR through various mechanisms of aberrant AR activation. Here we studied the 22Rv1 PCa cell line, which was derived from a CWR22 xenograft that relapsed during androgen ablation. Three AR isoforms are expressed in 22Rv1 cells: a full-length version with duplicated Exon 3, and two truncated versions lacking the COOH-terminal domain (CTD). We found that CTD-truncated AR isoforms are encoded by mRNAs that have a novel Exon 2b at their 3′ end. Functionally, these AR isoforms are constitutively active, and promote the expression of endogenous AR-dependent genes as well as the proliferation of 22Rv1 cells in a ligand-independent manner. AR mRNAs containing Exon 2b and their protein products are expressed in commonly studied PCa cell lines. Moreover, Exon 2b-derived species are enriched in xenograft-based models of therapy-resistant PCa. Together, our data describe a simple and effective mechanism by which PCa cells can synthesize a constitutively active AR, and thus circumvent androgen ablation.

Keywords: prostate cancer, androgen receptor, androgen refractory, mRNA splicing

Introduction

PCa is the most commonly diagnosed malignancy in U.S. males, and the second leading cause of male cancer mortality (1). In the event that surgery and/or radiation do not cure PCa, systemic therapy is based on inhibiting the AR. The AR is a 110 kDa steroid receptor transcription factor, which promotes the growth and survival of normal and cancerous prostate cells. Androgen ablation, which blocks the production and/or activity of androgens, initially results in a favorable clinical response. However, PCa invariably recurs in a fatal manifestation that is resistant to androgen ablation as well as further treatments. Importantly, clinical and experimental evidence has shown that this stage of the disease, termed androgen-refractory PCa, remains AR-dependent through mechanisms of aberrant AR activation (2, 3).

The AR shares a modular organization with other steroid receptors, and consists of an NTD, a central DBD, and a CTD. The amorphous NTD makes up nearly 60% of the AR protein, and has been resistant to structural determination. The remaining 40% is composed of the DBD and CTD, both of which have been extensively studied structurally and functionally (4-7). The AR NTD and CTD possess separate transcriptional activation domains, termed AF-1 and AF-2, respectively (8). AF-2 maps to a ligand-induced coactivator binding pocket, which is structurally conserved among steroid receptors (6). In contrast to the CTDs of other steroid receptors, the AR CTD in isolation displays very weak transcriptional activity (9). The AR NTD shares virtually no sequence identity with other known proteins, and functions as a potent transcriptional activator in isolation (6, 10, 11). The relative role of these domains in mediating the transcriptional activation of AR-regulated genes and the growth and progression of PCa is a critical unanswered question. We have shown that androgen-refractory PCa cells may circumvent androgen ablation through an aberrant, NTD-dependent, but CTD-independent mode of AR activity (10, 11). This suggests that activation of the AR NTD may be selected for during progression to androgen-refractory disease. This hypothesis is supported by the finding that a decoy molecule derived from the AR NTD blocks the growth and progression of prostate cancer in a xenograft-based model of PCa (12).

The androgen-refractory 22Rv1 PCa cell line was derived from an androgen-dependent CWR22 PCa xenograft that relapsed during androgen ablation (13). 22Rv1 cells are AR-dependent and express the AR-regulated gene, prostate specific antigen (PSA). AR mRNA in 22Rv1 cells contains a duplication of Exon 3, which results in a larger AR protein (hereafter referred to as AREx3dup), consisting of 3 zinc fingers in its DBD (14). AREx3dup does not exist in the parental CWR22 xenograft, and has not been observed in any other PCa tumor or cell line (14). Interestingly, in addition to AREx3dup, a novel short AR isoform is also expressed in 22Rv1 cells that may result from proteolytic cleavage of full-length AREx3dup (14, 15). Antibody mapping has demonstrated that this short AR isoform lacks most or all of the AR CTD, but retains an intact NTD and DBD (14). This model system therefore provides an excellent opportunity to study AR isoforms that either contain or lack the AR CTD. The purpose of this study was to understand the mechanism by which these AR isoforms regulate the androgen-refractory phenotype of 22Rv1 cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

PCa cell lines were purchased and cultured as described (11). LAPC4 cells were provided by Charles Sawyers (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York).

PCa Xenografts

AD and AI versions of LuCaP 23.1 and LuCaP 35 PCa xenografts have been described (16, 17). AD xenografts were propagated in Balb/c nu/nu mice and AI xenografts were propagated in SCID mice as described (16, 17). Animals were housed in the Mayo Clinic pathogen-free rodent facility and all procedures performed were approved by the Mayo Clinic institutional animal care and use committee. When tumors reached ∼100m3, they were excised and frozen on dry ice. Prior to RNA and protein extraction, tumor bits (∼27mm3) were pulverized under liquid N2 using a mortar and pestle.

Plasmids

Plasmid constructs for full-length AR (h5HBhAR) and MMTV-LUC have been described (10, 11). Plasmid 4XARE-E4-LUC was provided by Dr. Michael Carey (UCLA). Plasmid AREx1/2/2b was generated by mutating h5HBhAR to generate an XbaI site within Exon 2 using mutagenic primers FW: 5′-GGAAGCTGCAAGGTCTTCTAGAAAAGAGCCGCTGAAGG and RV: 5′-CCTTCAGCGGCTCTTTTCTAGAAGACCTTGCAGCTTCC and a Site Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene). Two oligonucleotides were synthesized and annealed (FW: 5′-CTAGAAAAGAGCCGCTGAAGGATTTTTCAGAATGAACAAATTAAAAGAATCA TAAG and RV: 5′-CTAGCTTATGATTCTTTTAATTTGTTCATTCTGAAAAATCCTTCAGCGGCTCTTTT) to generate a cassette which contained Exon 2 sequence downstream from the XbaI site spliced to Exon 2b. This cassette was phosphorylated and inserted into XbaI-cut h5HBhAR. The XbaI site within Exon 2 was then converted back to wild-type sequence via site directed mutagenesis. The same strategy was used to generate AREx1/2/2b, but in this case the mutagenic primers used were FW: 5′-GAAGCAGGGATGACTCTAGAAGCCCGGAAGCTGAAG and RV: 5′-CTTCAGCTTCCGGGCTTCTAGAGTCATCCCTGCTTC and oligonucleotides used for cassette generation were FW: 5′-CTAGGAGGATTTTTCAGAATGAACAAATTAAAAGAATCATAAT and RV: 5′-CTAGATTATGATTCTTTTAATTTGTTCATTCTGAAAAATCCTC.

Transient Transfections

AR-targeted siRNAs were purchased from Dharmacon. Custom-designed Exon 2b-targeted siRNAs (siEx2b-1 target sequence: 5′-AATCATAATCAGACACTAACC; siEx2b-2 target sequence: 5′-AAGCCATACTGCATGGCAGCA) were purchased from Ambion. The 22Rv1 cell line was transfected with siRNAs via electroporation as described (11) and harvested 72h post-transfection. The VCaP cell line was transfected with siRNAs using Lipofectamine 2000 as per the manufacturer’s protocol and harvested 48h post-transfection. For reporter gene assays, 105 cells were seeded in 24-well dishes and transfected the following day using 2μL of Superfect (Qiagen) mixed with 300ng of luciferase reporter, 100ng of SV40-Renlla, and 2ng or 10ng of hAR, hAREx1/2/2b, or hAREx1/2/3/2b. Transfections were performed in RPMI + 5% CSS. Transfection efficiencies ranged from 50-70%. At 24 hours post-transfection, medium was replaced with serum-free, phenol red-free RPMI with 1nM mibolerone (Biomol) or vehicle. Cells were harvested after an additional 24 hours in a lysis buffer provided with a Dual Luciferase Assay Kit (Promega). Activities of the firefly and Renilla luciferase reporters were assayed in 96-well plates via Dual Luciferase Assay and detected with a Molecular Devices LMax luminometer. Transfection efficiency was addressed by dividing firefly luciferase activity by Renilla luciferase activity. Data presented represent the mean +/- S.E.M. from at least 3 independent experiments, each performed in duplicate.

RNA Isolation, 3′-RACE, and RT-PCR

Total cellular RNA was isolated from cell lines and xenografts using acid-guanidinium phenol/chloroform extraction as described (10). RNA was reverse transcribed using a RT kit and an oligo(dT) primer (Roche). cDNAs were subjected to a two-step 3′-RACE procedure using a 3′-RACE kit (Roche). For the first step, cDNA 3′ ends were amplified using a forward primer anchored within Exon 1 (5′-TTGAACTGCCGTCTACCCTGTC) and the reverse primer from the kit. This step 1 reaction was diluted 1:1000 and further amplified using nested Exon 1 or 2b-anchored primers (Ex1 FW: 5′-ACAACTTTCCACTGGCTCTGGC; Ex2b FW: 5′-AATCAGACACTAACCCCAAG) and the reverse primer from the kit.

Conventional PCR was performed on cDNAs using Ex1 FW paired with a reverse primer specific for Exon 2b (5′-TATGGCTTGGGGTTAGTGTC). Absolute quantitation of AR mRNA species was performed using an Exon 2-anchored forward primer (qEx2 FW: 5′-GTGGAAGCTGCAAGGTCTTC) paired with either an Exon 4-anchored reverse primer (qEx4 RV: TTCAGATTACCAAGTTTCTTCAGC) or an Exon 2b-anchored reverse primer (qEx2b RV: TTTCTTCAGTCCCATTGGTG). Quantitative PCR with serial dilutions of plasmids harboring Exon 1/2/2b or Exon 1-8 cDNAs was performed using a CyberGreen mastermix (BD Biosciences) exactly as described (20). Threshold cycle of amplification (Ct) values from these standards were used to generate Ct vs. cDNA concentration standard curves. Ct values from test RNA samples were obtained via quantitative PCR and were extrapolated from these standard curves to generate absolute values for copy number.

For relative quantitation of AR target genes, quantitative real-time PCR was performed on cDNAs exactly as described (20) using primers specific for PSA (11), hK2 (18), TMPRSS2, (18) NKX3.1 (FW: 5′-GTACCTGTCAGCCCCTGAAC; RV: 5′-GGAGAGCTGCTTTCGCTTAG), SCAP (FW: 5′-CGGTAGACCTGGAGGTGA; RV: 5′-CGGGCACTAGGGTGAAGTAG), maspin (FW: 5′-CCCTATGCAAAGGAATTGGA; RV: 5′-CAAAGTGGCCATCTGTGAGA), and GAPDH (Applied Biosystems). Relative quantitation was used to determine fold change in expression levels by the comparative Ct method using the formula 2-ΔΔCt.

Western Blot

PCa cell lines and xenografts were subjected to Western blot analysis exactly as described (11). Blots were incubated with antibodies specific for AR (Santa Cruz, N-20, A-442, or N-20) or ERK-2 (Santa Cruz, D-2) exactly as described (11).

Cell Viability and Proliferation Assays

Electroporated 22Rv1 cells were seeded at a density of 3000 cells/well on 96-well plates in RPMI 1640 + 5% CSS. Following 24h growth, medium was replaced with RPMI 1640 + 5% CSS containing 1nM DHT (Sigma) or vehicle. Following 0 and 96h of subsequent growth, viable cell numbers were determined by MTS reduction (Cell Titer 96 AQueous One, Promega) as described (10). Cell proliferation assays were performed using the exact same approach; BrdU incorporation was measured 24h after DHT/vehicle treatment using a Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (Promega) via manufacturer specifications.

Results

Short AR Isoforms Mediate Ligand-Independent AR Activity in 22Rv1 Cells

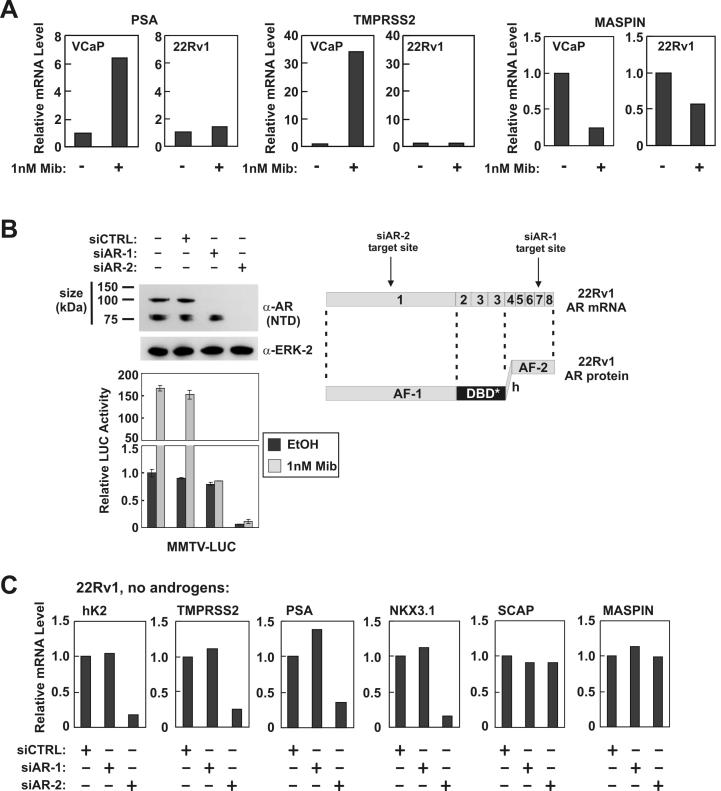

To assess whether Exon 3 duplication imparts gain-of-function to the AR in 22Rv1 cells, we quantified expression of AR target genes via real-time RT-PCR. For comparison, we employed the VCaP PCa cell line, which harbors wild-type AR protein. Following 24h treatment with the synthetic androgen, mibolerone, the androgen-responsive PSA and TMPRSS2 (19) genes were strongly up-regulated in VCaP, but not 22Rv1 cells (Fig. 1A). In line with these findings, maspin, an androgen-repressed tumor suppressor gene (20), demonstrated stronger inhibition in VCaP than 22Rv1 cells. These findings suggest that AREx3dup responds more poorly to androgens than wild-type AR.

Figure 1.

Short AR isoforms specifically mediate ligand-independent transcriptional activation of AR target genes. A, RNA was isolated from VCaP and 22Rv1 cells grown in vehicle or 1nM mibolerone (Mib) and subjected to quantitative real-time RT-PCR using primers specific for PSA, TMPRSS2, and maspin. Expression levels are relative to vehicle treatment, which was arbitrarily set to 1. B, 22Rv1 cells were transfected with MMTV-Luc, non-targeted control (CTRL) siRNA, or siRNAs targeted to AR Exon 1 or 7 (schematic on right; DBD* denotes a three zinc-finger DBD). Cells were grown 24h in serum-free medium and treated with 1nM Mib or EtOH (vehicle control) for 24h. Luciferase activity was determined. Data represent the mean +/- S.E. from at least three independent experiments, each performed in duplicate. MMTV promoter activity without androgens and siRNAs was arbitrarily set to 1. Lysates from vehicle-treated cells were subjected to Western blot using a polyclonal antibody targeted to the AR NTD. ERK-2 levels are shown as a control. C, 22Rv1 cells were transfected with non-targeted control (CTRL) siRNA, or siRNAs targeted to AR Exon 1 (siAR-2) or 7 (siAR-1). RNA was isolated from transfected cells grown for 72h without androgens. RT-PCR was performed using primers specific for hK2, PSA, TMPRSS2, NKX3.1, SCAP, and maspin. Expression levels are relative to vehicle treatment, which was arbitrarily set to 1.

One explanation for these findings could be that AR-regulated genes are already expressed at a high level in the absence of androgens in 22Rv1 cells. To test for ligand-independent AR activity in 22Rv1 cells, we knocked-down the AR via small-interfering RNA (siRNA). Unexpectedly, we observed that siRNA targeted to AR Exon 7 selectively ablated AREx3dup, but had no effect on expression of the short AR isoform in these cells (Fig. 1B). Moreover, these experiments demonstrated that the previously described short AR isoform (14) occurs as a doublet. Whereas the AR Exon 7-targeted siRNA selectively ablated AREx3dup, a siRNA targeted to AR Exon 1 ablated all AR isoforms (Fig. 1B). We employed a mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV)-regulated promoter reporter in these experiments to monitor AR activity. siRNA-mediated ablation of AREx3dup abolished MMTV-Luc androgen-responsiveness, but had no effect on ligand-independent MMTV-Luc activity (Fig. 1B). Conversely, a significant inhibition of ligand-independent MMTV-Luc activity was observed upon ablation of the short AR isoforms. Similarly, ligand-independent expression of the endogenous AR target genes hK2 (21), PSA, TMPRSS2, and NKX3.1 (22) was strongly inhibited by siRNA targeted to AR Exon 1 but not AR Exon 7 (Fig. 1C). Expression of maspin and SCAP, an AR-activated gene (23), were not affected by AR-targeted siRNAs. These results suggest that AREx3dup mediates weak androgen-dependent AR activity in 22Rv1 cells, whereas the shorter AR isoforms mediate constitutive, albeit selective, ligand-independent AR activity. Differential ablation by Exon 1-targeted vs. Exon 7-targeted siRNA demonstrates that AREx3dup and the short AR isoforms are derived from distinct mRNA species. Therefore, contrary to previous reports (14, 15), the short AR isoform(s) expressed in 22Rv1 cells is not a proteolytic cleavage product of AREx3dup.

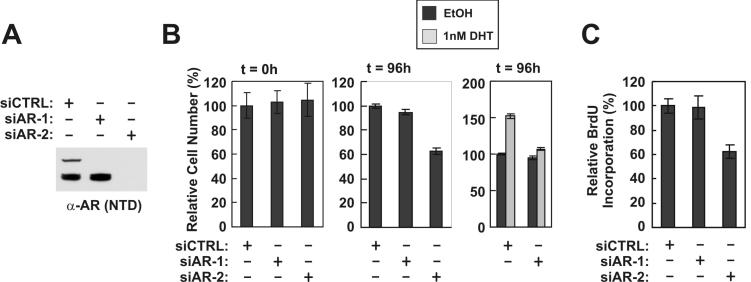

Short AR Isoforms Mediate Androgen-Independent Proliferation of 22Rv1 Cells

To test whether selectively knocking down AREx3dup and the short AR isoforms also selectively affected androgen-dependent vs. androgen-independent cell growth, we performed growth assays on 22Rv1 cells 96 hours following transfection with AR-targeted siRNAs (Fig. 2A). In line with RT-PCR and reporter gene assays (Fig. 1), ablation of AREx3dup inhibited androgen-dependent, but not androgen-independent 22Rv1 growth (Fig. 2B). Conversely, ablation of the short AR isoforms inhibited growth of 22Rv1 cells in the absence of androgens (Fig. 2B). Cell proliferation assays with BrdU demonstrated that ablation of the short AR isoforms specifically inhibited the ability of 22Rv1 cells to proliferate in the absence of androgens (Fig. 2C), but did not affect levels of apoptosis (data not shown). These findings suggest that AREx3dup specifically mediates the growth of 22Rv1 cells in response to androgens, while the short AR isoforms specifically promote the androgen-independent proliferation of 22Rv1 cells.

Figure 2.

Short AR isoforms specifically mediate ligand-independent growth of androgen-refractory 22Rv1 cells. 22Rv1 cells were transfected with non-targeted control (CTRL) siRNA, or siRNAs targeted to AR Exon 1 (siAR-2) or 7 (siAR-1). A, Transfected cells were cultured 72h post-transfection, lysed, and subjected to Western blot using a polyclonal antibody targeted to the AR NTD. ERK-2 levels are shown as a control. B, Transfected cells were seeded and cultured for 24h in medium supplemented with 5% charcoal-stripped serum (CSS). Cells were treated with 1nM DHT or ethanol (EtOH, vehicle control). The relative number of viable cells 0h and 96h following exposure to these compounds was determined by MTS assay. Values shown are relative to siCTRL-treated cells without androgens, which was arbitrarily set to 100%. Data represent the mean +/- S.E.M. from two experiments performed in quadruplicate. C, Transfected cells were seeded and treated as described in B. The relative number of proliferating cells 24h after treatment was determined by BrdU incorporation. Values are relative to siCTRL-treated cells grown without androgens, which was arbitrarily set to 100%. Data represent the mean +/- S.E.M. from two experiments performed in quadruplicate.

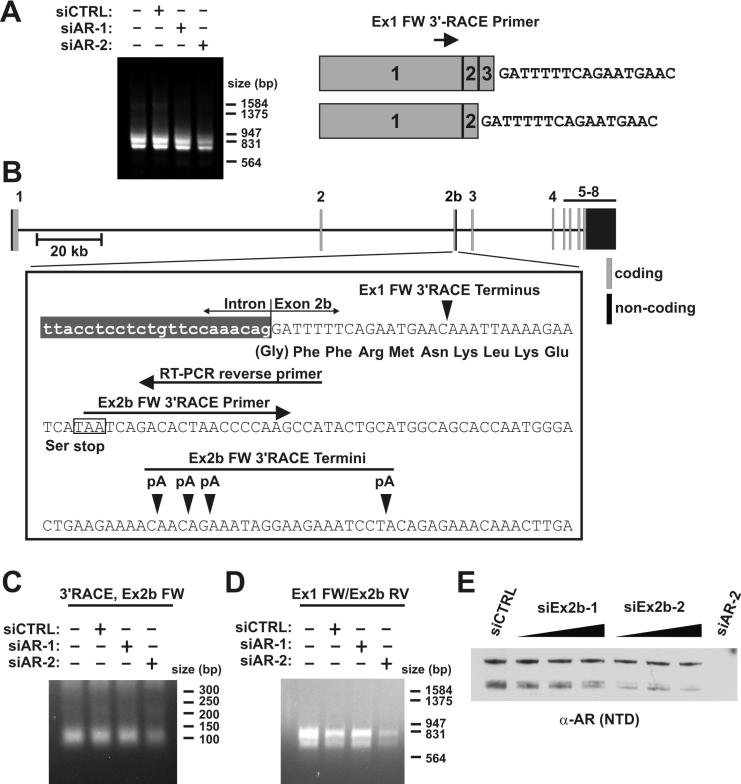

Identification and Characterization of a Novel AR Exon

Our data demonstrates that the short AR isoforms expressed in 22Rv1 cells mediate critical features of the androgen-refractory phenotype. Our siRNA data also shows that these short AR isoforms are translated from mRNA species distinct from AREx3dup. We therefore generated cDNA from 22Rv1 RNA, and performed 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) with an Exon 1-anchored primer in order to isolate any potential AR mRNAs with novel 3′ ends (Fig. 3A). This approach yielded two discrete ∼800bp and ∼900bp PCR products, which were reduced by Exon 1-targeted, but not Exon 7-targeted siRNA (Fig. 3A). Cloning and sequencing of these products revealed the presence of a novel 17bp sequence spliced to either Exon 2 or Exon 3 (Figs. 3A and 3B). Using human genome sequence data, we mapped this sequence, which we termed Exon 2b, to a region ∼37kb downstream from AR Exon 2 (Fig. 3B). Genomic sequence immediately following this Exon 2b sequence tag was followed by an A-rich segment, which suggested the oligo(dT) primer used for 3′RACE had generated a premature 3′ cDNA end. Therefore, we designed a second 3′RACE primer, which was targeted to a sequence downstream from a putative translation stop codon in Exon 2b (Fig. 3C). This approach yielded a ∼90-120 bp PCR product, the expression of which was selectively reduced in 22Rv1 cells treated with Exon 1-targeted siRNA (Fig. 3C). Cloning and sequencing revealed that this additional sequence contained the remainder of Exon 2b, which was polyadenylated at several sites 91-113bp downstream from the beginning of the Exon (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Short AR isoforms are encoded by novel mRNAs containing a novel AR Exon 2b. A, 22Rv1 cells were transfected with non-targeted control (siCTRL) siRNA, or siRNAs targeted to AR Exon 1 (siAR-2) or 7 (siAR-1) as indicated. RNA was isolated and subjected to 2-step 3′-RACE using Exon 1-anchored forward primers. PCR products were cloned and sequenced. A schematic of this approach and resultant sequence data are shown on the right. B, Relative location of Exon 2b in the AR locus and summary of 3′-RACE and RT-PCR experiments. Details are discussed in the text. C, A second 3′RACE reaction was performed on RNA as described in A using an Exon 2b-anchored forward primer indicated in B. PCR products were cloned and sequenced, which revealed 3′termini 91-113bp downstream from the start of Exon 2b. These putative sites of polyadenylation are indicated in B. D, RT-PCR was performed on RNA used in A and C with the Exon 1-anchored forward primer used for 3′RACE and a reverse primer indicated in B. PCR products were cloned and sequenced and confirmed to consist of spliced Exons 1/2/2b or 1/2/3/2b. E, 22Rv1 cells were transfected with non-targeted control (CTRL) siRNA, or siRNAs targeted to Exon 1 (siAR-2) or 2b. Transfected cells were cultured 48h post-transfection, lysed, and subjected to Western blot using a polyclonal antibody targeted to the AR NTD.

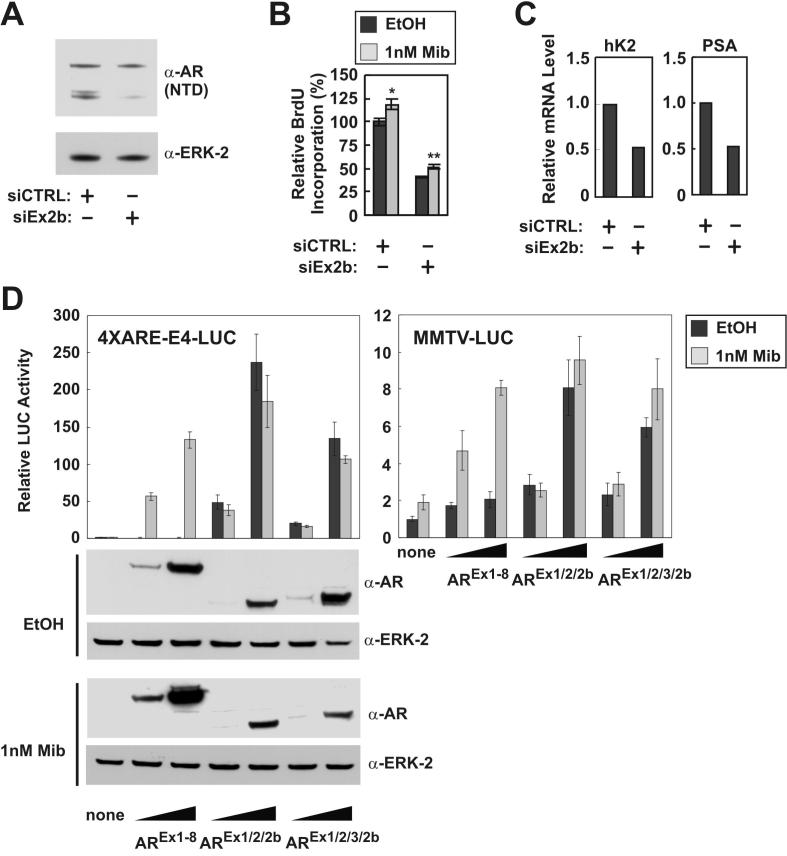

Examination of Exon 2b sequence indicated that mRNAs consisting of Exons 1/2/2b would generate a truncated AR consisting of the NTD, the first zinc finger in the DBD, and 11aa of Exon 2b-derived sequence (Fig. 3B). An mRNA consisting of Exons 1/2/3/2b would only exist in cells such as 22Rv1, where Exon 3 has been duplicated within the AR locus. Exon 2 and 3 have the same reading frame; therefore an mRNA consisting of Exons 1/2/3/2b would generate a second truncated AR consisting of the NTD, the entire two zinc finger DBD, and Exon 2b-derived sequence (Fig. 3B). We confirmed the existence of contiguous mRNAs consisting of Exons 1/2/2b and 1/2/3/2b in 22Rv1 cells via RT-PCR using primers anchored within Exons 1 and 2b (Figs. 3B and D). To confirm that mRNAs harboring Exon 2b gave rise to the short AR isoforms observed in 22Rv1 cells (hereafter referred to as AR1/2/2b and AR1/2/3/2b), we designed two separate siRNAs targeted to AR Exon 2b. As expected, these siRNAs knocked down the expression of AR1/2/2b and AR1/2/3/2b, but did not affect the expression of AREx3dup (Fig. 3E). Exon 2b-targeted siRNA specifically inhibited androgen-independent, but not androgen-dependent 22Rv1 proliferation, as assessed by BrdU incorporation (Figs. 4A and B). In line with these findings, Exon 2b-targeted siRNA inhibited androgen-independent expression of AR target genes in 22Rv1 cells (Fig. 4C). These data thus define a novel Exon 2b within the AR locus of 22Rv1 cells, which can splice to Exon 2 or 3, giving rise to CTD-truncated AR species that promote an androgen-refractory phenotype.

Figure 4.

AR1/2/2b and AR1/2/3/2b are constitutively active. A-C, 22Rv1 cells were transfected with non-targeted control (CTRL) siRNA, or siRNA targeted to Exon 2b. Transfected cells were cultured 24h post-transfection, and subjected to A, Western blot, B cell proliferation assay (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.002, compared to vehicle-treated cells), and C, quantitiative RT-PCR exactly as described in the legends to Figs. 1 and 2. D, DU-145 cells were transfected with expression vectors encoding full-length wild-type AR (AR1-8), AREx1/2/2b, or AREx1/2/3/2b in conjunction with MMTV-LUC or 4XARE-E4-LUC. Cells were treated under serum-free conditions with 1nM mibolerone (Mib) or ethanol (EtOH, vehicle control) for 24h. Luciferase activity was determined. Data represent the mean +/- S.E. from at least three independent experiments, each performed in duplicate. The activity of reporters in the absence of transactivator or androgens was arbitrarily set to 1. Lysates were analyzed by Western blot using an antibody specific for the AR NTD.

AR Isoforms Encoded by Exons 1/2/2b and 1/2/3/2b Are Constitutively Active

We next performed functional tests of AR1/2/2b and AR1/2/3/2b by co-transfecting AR-null DU-145 cells with expression vectors and AR-responsive reporter constructs (Fig. 4D). Expression of full-length AR (AREx1-8) rendered both MMTV-Luc and 4XARE-E4-Luc responsive to androgens. Expression of either AR1/2/2b or AR1/2/3/2b induced strong activation of these reporters in the absence of androgens. As expected, androgen treatment had no effect on the transcriptional activities of these short AR isoforms. These results demonstrate that both AR1/2/2b and AR1/2/3/2b can independently function as constitutively active transcription factors.

AR1/2/2b Expression in PCa Cell Lines

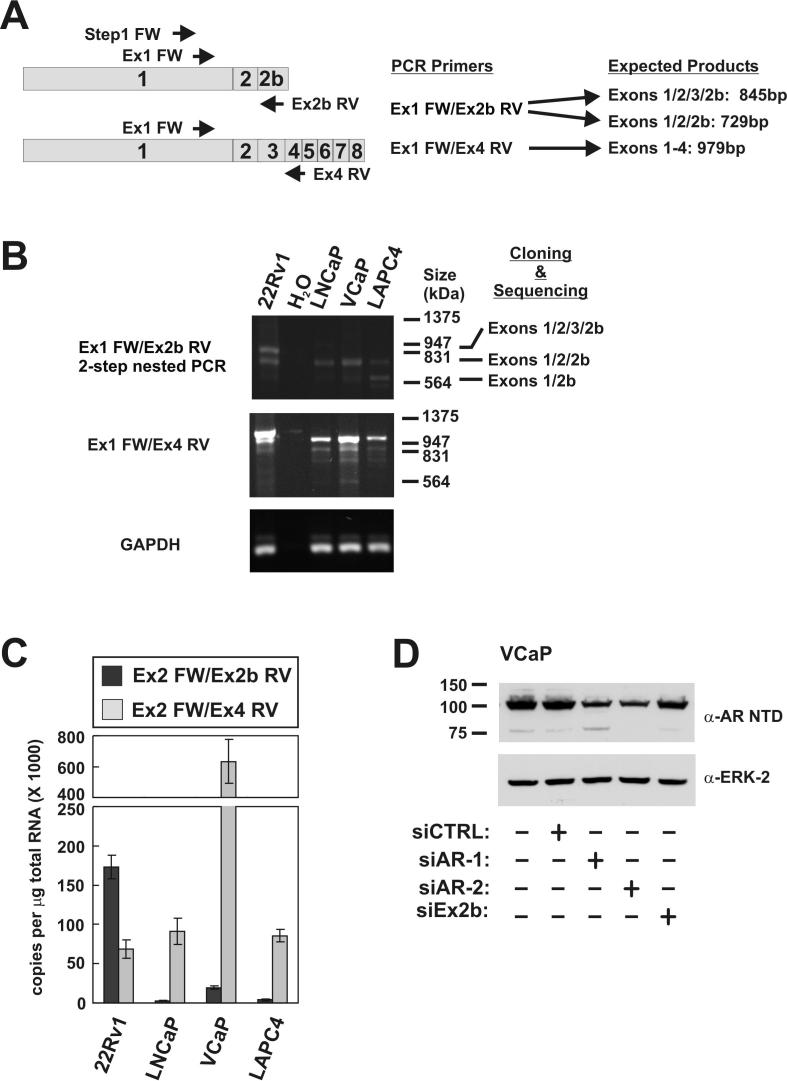

Expression of the AR1/2/3/2b isoform should be restricted to cells with duplication of Exon 3, which permits the generation of pre-mRNAs with Exon 2b downstream of Exon 3. However, synthesis of mRNAs encoding AR1/2/2b could be achieved in any cell type with a normal AR locus. Our finding that AR1/2/2b is a constitutively active AR isoform highlights Exon 2b splicing as a simple and effective mechanism by which PCa could circumvent androgen ablation. Therefore, to assess if AR mRNAs composed of Exons 1/2/2b exist outside of the 22Rv1 model system, we performed RT-PCR with oligo(dT)-primed cDNAs generated from androgen-dependent LNCaP, VCaP, and LAPC4 PCa cell lines (Fig 5A and 5B). Following 35 cycles of amplification, we observed a faint PCR product from VCaP cDNA, which corresponded to the product composed of Exon 1/2/2b from 22Rv1 cells (data not shown). However, using a two-step RT-PCR strategy, wherein an initial 20-cycle PCR was diluted and used for a second 35-cycle PCR, we observed products of the expected size in LNCaP, VCaP, and LAPC4 cells (Fig 5B). Cloning and sequencing confirmed these products resulted from splicing of Exons 1/2/2b. In addition to this Exon 1/2/2b product, we also observed a product of ∼600bp generated from LAPC4 cDNA. Interestingly, cloning and sequencing revealed that this product resulted from splicing of Exon 1 to Exon 2b. As a control, we also tested for generation of full-length AR mRNA using Exon 1 and Exon 4 PCR primers. Products of the expected size were generated with cDNAs from LNCaP, VCaP, and LAPC4 PCa cells. Together, these results demonstrate that the cellular machinery required for Exon 2b inclusion is not restricted to 22Rv1 cells.

Figure 5.

AR1/2/2b mRNA and protein is expressed in PCa cell lines. A, Schematic of AR mRNA species and PCR primer sets used for their detection. B, RT-PCR analysis of PCa cell lines. cDNAs were amplified by 2-step nested PCR using forward and reverse primer sets as indicated. Major bands were cloned and sequenced. The identity of sequenced products is indicated on the right. C, The absolute abundance of full-length AR mRNA and AR Exon 1/2/2b mRNA were determined using specific PCR primers in quantitative RT-PCR reactions. Threshold amplification cycle (Ct) values were converted to copy number by extrapolating against standard curves generated from serial dilutions of plasmids harboring Exon 1/2/2b or Exon 1-8 cDNAs. Data represent the mean +/- S.E.M. from four independent experiments. D, VCaP cells were transfected with non-targeted control (CTRL) siRNA, or siRNAs targeted to Exon 7 (siAR-1), Exon 1 (siAR-2), or Exon 2b. Transfected cells were cultured 48h post-transfection, lysed, and subjected to Western blot using a polyclonal antibody targeted to the AR NTD.

To quantitatively compare the amounts of full-length AR mRNA and AR Exon 1/2/2b mRNAs in these cell lines, we performed absolute quantitation using a standard curve of known target concentrations. For measurement of full-length AR mRNA, we employed an Exon 2 forward primer paired with an Exon 4 reverse primer. For measurement of AR Exon 1/2/2b mRNA, we employed the same Exon 2 forward primer paired with an Exon 2b reverse primer. Due to this design, this assay did not discriminate between the Exon 1/2/2b and Exon 1/2/3/2b mRNA species expressed in 22Rv1 cells, but provided a measure of the combined level of these two mRNAs. As expected, androgen-refractory 22Rv1 cells expressed higher amounts of Exon 2b-containing mRNAs than androgen-dependent LNCaP, VCaP, or LAPC4 cells (Fig. 5C). Moreover, Exon 2b-containing AR mRNAs were expressed at a higher level than full-length AR mRNA in the 22Rv1 cells line (Fig. 5C). Conversely, in LNCaP, VCaP, and LAPC4 cells, AR Exon 1/2/2b mRNA was consistently expressed at 5-10% of the level of full-length AR mRNA (Fig. 5C). Of these androgen-dependent cell lines, VCaP cells expressed the highest level of both full-length AR and AR Exon 1/2/2b mRNAs (Fig. 5C). We therefore sought to test whether the AR Exon 1/2/2b mRNA expressed in VCaP cells was translated into AR1/2/2b protein. Indeed, in addition to full-length AR, a faint immunoreactive species of approximately 75kDa was observed in VCaP cells. To determine the precise identity of this protein, we exploited the selective targeting properties of AR siRNAs (Fig. 5D). As expected, Exon 1 and Exon 7-targeted siRNAs knocked-down expression of full-length AR protein. However, only Exon 1-targeted siRNA knocked down expression of the 75kDa species. Similarly, Exon 2b-targeted siRNA knocked down expression of the 75kDa species, but not the full-length AR. From this data, we conclude that commonly-studied PCa cell lines express mRNA and protein derived from splicing of AR Exons 1/2/2b.

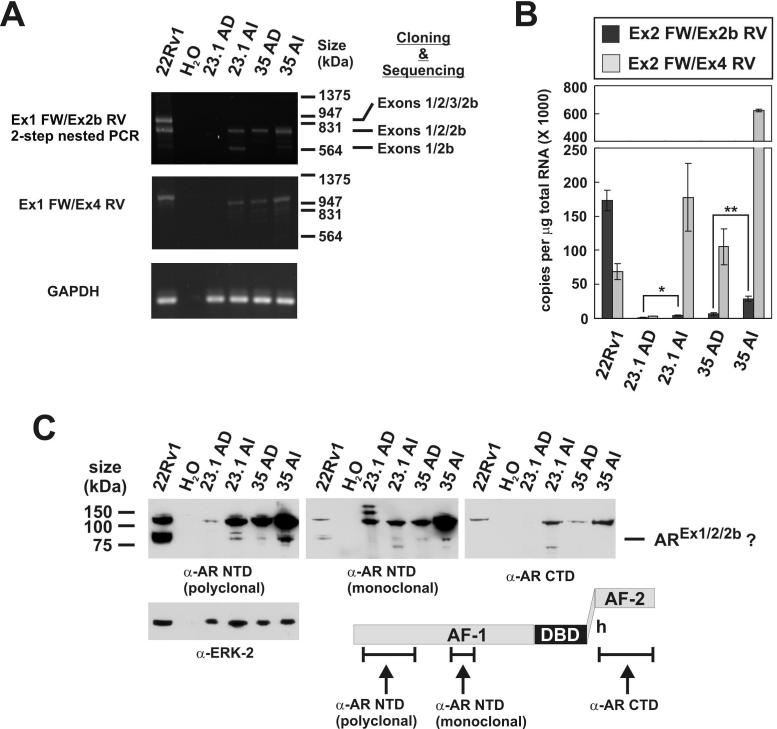

AR1/2/2b Expression in PCa Xenografts

These results raised the possibility that androgen ablation could select for PCa cells that can effectively synthesize AR1/2/2b. To test whether expression of AR1/2/2b might be increased during PCa progression, we employed the LuCaP 23.1 and LuCaP 35 xenograft models. LuCaP 23.1 and 35 tumors grow in intact immunocompromised mice, and serve as an accurate model of androgen- and AR-dependent (AD) PCa (16, 17). For example LuCaP 23.1 and 35 tumors regress following castration, but eventually recur in an AR-dependent, but androgen-refractory manner. We isolated total RNA from AD and androgen-refractory/independent (AI) versions of LuCaP tumors that had been propagated in intact and castrated mice, respectively. Similar to our observations in PCa cell lines, we detected mRNAs resulting from splicing of Exons 1/2/2b in these xenografts (Fig. 6A). The absolute abundance of both full-length AR mRNA and Exon 1/2/2b mRNA were increased in AI vs. AD samples for both LuCaP 23.1 and 35 tumors (Fig. 6B). To further support this observation, we performed Western blotting on lysates from AD and AI LuCaP 23.1 and 35 tumors (Fig. 6C). Using two separate antibodies targeted to the AR NTD, we observed immunoreactive species with the exact same mobility as AR1/2/2b from 22Rv1 lysates (Fig. 6C). These species were not detected using an AR CTD-directed antibody, which further indicated they likely represented AR1/2/2b protein. Importantly, increased expression of this putative AR1/2/2b species was observed in AI vs. AD xenografts, which was similar in magnitude to the increase observed for AR 1/2/2b mRNA. We also observed significantly more full-length AR protein in AI vs. AD xenografts, which has been previously reported (24). Our data suggests that increased expression of AR1/2/2b may play a previously unrecognized role in mediating the androgen-refractory phenotype of LuCaP 23.1 AI and LuCaP 35 AI xenografts.

Figure 6.

AR1/2/2b mRNA is enriched in xenograft-based models of androgen-refractory prostate cancer. A, cDNAs were amplified by 2-step PCR using the same forward and reverse primer sets depicted in the legend for Fig. 5. Major bands were cloned and sequenced. The identity of sequenced products is indicated on the right. B, The absolute abundance of full-length AR mRNA and AR Exon 1/2/2b mRNA were determined using specific PCR primers in quantitative RT-PCR reactions. Ct values were converted to copy number by extrapolating against standard curves generated from serial dilutions of plasmids harboring Exon 1/2/2b or Exon 1-8 cDNAs. Data represent the mean +/- S.E.M. from four independent experiments (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.001). C, Lysates from androgen dependent (AD) and androgen independent (AI) versions of LuCaP 23.1 and 35 xenografts were subjected to Western blot using polyclonal antibodies recognizing the AR NTD or CTD, or a monoclonal antibody recognizing the AR NTD. The putative AR1/2/2b isoform is indicated on the right. A schematic of the antibody recognition sites is shown at the bottom of the figure.

Discussion

Nuclear receptor CTDs serve a dual function, possessing both the LBD and AF-2 coactivator binding surface. The model for activation of the AR and other steroid receptors is that ligand binding induces an AF-2 conformation that is permissive for docking with NR boxes (LxxLL and related motifs) of coactivator molecules, which are required for transcriptional activation. For the AR, this model is complicated by the fact that AR AF-2 can also bind an FxxLF motif in the AR NTD, and thus mediate an interaction between the N- and C-termini (9, 25). In in vitro assays, the affinity of AF-2 for AR-derived FxxLF peptides is higher than for coactivator-derived LxxLL peptides (6, 26). As a result, the importance and role of AR AF-2 in transcriptional activation of target genes has been a topic of debate. Indeed, AR AF-2 functions as a very weak ligand-dependent transcriptional activation domain in isolation (9, 27, 28). However, the isolated AR NTD is stronger in reporter gene assays than the isolated AR CTD (27, 29). Our previous studies have demonstrated that the AR NTD may play a major role in mediating PCa therapy resistance (10, 11). The data we present in this study supports this concept, and has shown for the first time that naturally-occurring AR isoforms, consisting of the NTD and DBD, can support the expression of many endogenous AR target genes as well as the growth of androgen-refractory PCa cells in the absence of androgens.

Various mechanisms of resistance to androgen ablation therapy have been proposed and demonstrated in various models of PCa progression. For example, mutations in the AR LBD broaden the ligand specificity of the AR, thus permitting activation by alternative steroids or even antiandrogens (2). AR overexpression, which may result from AR gene amplification and/or enhanced AR transcription, has been shown to sensitize the AR to castrate levels of androgens (24, 30). Indeed, tissue androgens in androgen refractory PCa may persist at levels sufficient to elicit AR activation, and may arise from aberrant intra-tumor androgen production (31-33). All of these mechanisms are ligand-dependent in nature, and have called into question the importance of ligand-independent AR activation for the development and progression of androgen-refractory PCa. However, in this study, our data demonstrates that the androgen-refractory phenotype of 22Rv1 cells is due to novel AR isoforms that function in a completely ligand-independent fashion. Moreover, these isoforms would be completely resistant to all current androgen ablation regimens, which are targeted to the AR CTD. Our observation that other commonly-used PCa cell lines possess the machinery required to synthesize the ligand-independent AREx1/2/2b isoform provides a novel and simple avenue for these PCa cells to achieve androgen-independence. Indeed, in two xenograft-based models of PCa progression, we observed increased expression of AR Exon 1/2/2b mRNA in AI vs. AD tumors. Moreover, we observed a similar increased expression of a 75kDa AR species in these AI vs. AD tumors. Our data strongly suggests that this protein species is AREx1/2/2b; however, a definite conclusion will have to await the development of antibodies specific for this AR isoform. Importantly, in these models, AREx1/2/2b overexpression was accompanied by overexpression of full-length AR, which has been previously described (24). Since mRNAs encoding both full-length AR and AREx1/2/2b are spliced from the same pre-mRNA, enhanced transcription of the AR gene would result in enhanced overall expression of both isoforms. It will therefore be important to assess the relative contributions of AR and AREx1/2/2b overexpression to PCa progression during androgen ablation.

Two previous studies have investigated the nature of the small AR isoform(s) expressed in 22Rv1 cells, and have concluded that these species arise from calpain-mediated cleavage of AREx3dup (14, 15). Our data oppose this conclusion, and demonstrates that the AR NTD/DBD isoforms expressed in 22Rv1 cells arise from splicing of a novel AR Exon 2b after either AR Exon 2 or Exon 3. AR Exon 2b spliced after Exon 2 or Exon 3 gives rise to protein species possessing the entire AR NTD fused to the first zinc finger of the AR DBD (termed AREx1/2/2b), or the entire AR NTD fused to the complete AR DBD (termed AREx1/2/3/2b), respectively. Structural studies with AR DBD demonstrate that the first zinc finger, encoded by Exon 2, harbors the recognition helix that directly engages with one hexameric half-site in an androgen response element (ARE) (5). The second zinc finger, encoded by Exon 3, mediates dimerization with an AR molecule engaged with the neighboring ARE half-site (5). Our finding that AREx1/2/2b is able to constitutively activate AR-responsive promoters demonstrates that the first zinc finger is sufficient for the AR to engage with AREs, which agrees with this structural data. However, since the second Exon 3-encoded zinc finger is responsible for AR dimerization and subsequent stabilization of ARE-bound ARs, the repertoire of genes that are activated by AREx1/2/2b may be diminished compared to the repertoire of genes that are activated by full-length, liganded AR. Dissecting the differential patterns of gene activation by AREx1/2/2b and full-length, liganded AR will be important for understanding the relative abilities of these isoforms to mediate PCa growth.

In summary, our data indicates that AR truncation, resulting from aberrant splicing of a novel AR Exon 2b, uncouples androgen signaling from AR activity in 22Rv1 cells. AR mRNA and protein containing Exon 2b were also identified in commonly used PCa cell lines. Our data further shows that AR mRNA species containing Exon 2b were enriched in xenograft-based models of PCa progression. Therefore, inclusion of Exon 2b in AR mRNAs represents an effective mechanism by which constitutively active AR proteins can be produced that are completely resistant to current CTD-directed PCa therapies.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Haojie Huang for critical evaluation of this manuscript and Kevin Regan for assistance with maintaining LuCaP xenografts.

Grant Support: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants CA121277, DK065236, and CA91956 (to D.J.T.) and the TJ Martell Foundation (to D.J.T.). The LuCaP series of xenografts were developed with support from the Richard M. Lucas Foundation and the Prostate Cancer Foundation (to R.L.V). S.M.D. is a research fellow of the Terry Fox Foundation through a grant from the National Cancer Institute of Canada.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:106–130. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taplin ME. Drug insight: role of the androgen receptor in the development and progression of prostate cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;4:236–244. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heinlein CA, Chang C. Androgen receptor in prostate cancer. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:276–308. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matias PM, Donner P, Coelho R, et al. Structural evidence for ligand specificity in the binding domain of the human androgen receptor. Implications for pathogenic gene mutations. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26164–26171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004571200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaffer PL, Jivan A, Dollins DE, Claessens F, Gewirth DT. Structural basis of androgen receptor binding to selective androgen response elements. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4758–4763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401123101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He B, Gampe RT, Jr., Kole AJ, et al. Structural basis for androgen receptor interdomain and coactivator interactions suggests a transition in nuclear receptor activation function dominance. Mol Cell. 2004;16:425–438. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Estebanez-Perpina E, Moore JM, Mar E, et al. The molecular mechanisms of coactivator utilization in ligand-dependent transactivation by the androgen receptor. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8060–8068. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407046200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dehm SM, Tindall DJ. Androgen receptor structural and functional elements: role and regulation in prostate cancer. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:2855–2863. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He B, Kemppainen JA, Voegel JJ, Gronemeyer H, Wilson EM. Activation function 2 in the human androgen receptor ligand binding domain mediates interdomain communication with the NH(2)-terminal domain. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37219–37225. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dehm SM, Tindall DJ. Ligand-independent androgen receptor activity is activation function-2-independent and resistant to antiandrogens in androgen refractory prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:27882–27893. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605002200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dehm SM, Regan KM, Schmidt LJ, Tindall DJ. Selective role of an NH2-terminal WxxLF motif for aberrant androgen receptor activation in androgen depletion independent prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10067–10077. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quayle SN, Mawji NR, Wang J, Sadar MD. Androgen receptor decoy molecules block the growth of prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1331–1336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606718104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sramkoski RM, Pretlow TG, 2nd, Giaconia JM, et al. A new human prostate carcinoma cell line, 22Rv1. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 1999;35:403–409. doi: 10.1007/s11626-999-0115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tepper CG, Boucher DL, Ryan PE, et al. Characterization of a novel androgen receptor mutation in a relapsed CWR22 prostate cancer xenograft and cell line. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6606–6614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Libertini SJ, Tepper CG, Rodriguez V, Asmuth DM, Kung HJ, Mudryj M. Evidence for calpain-mediated androgen receptor cleavage as a mechanism for androgen independence. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9001–9005. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellis WJ, Vessella RL, Buhler KR, et al. Characterization of a novel androgen-sensitive, prostate-specific antigen-producing prostatic carcinoma xenograft: LuCaP 23. Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2:1039–1048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corey E, Quinn JE, Buhler KR, et al. LuCaP 35: a new model of prostate cancer progression to androgen independence. Prostate. 2003;55:239–246. doi: 10.1002/pros.10198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heemers HV, Regan KM, Dehm SM, Tindall DJ. Androgen induction of the androgen receptor coactivator four and a half LIM domain protein-2: evidence for a role for serum response factor in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10592–10599. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin B, Ferguson C, White JT, et al. Prostate-localized and androgen-regulated expression of the membrane-bound serine protease TMPRSS2. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4180–4184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang M, Magit D, Sager R. Expression of maspin in prostate cells is regulated by a positive ets element and a negative hormonal responsive element site recognized by androgen receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:5673–5678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murtha P, Tindall DJ, Young CY. Androgen induction of a human prostate-specific kallikrein, hKLK2: characterization of an androgen response element in the 5′ promoter region of the gene. Biochemistry. 1993;32:6459–6464. doi: 10.1021/bi00076a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prescott JL, Blok L, Tindall DJ. Isolation and androgen regulation of the human homeobox cDNA, NKX3.1. Prostate. 1998;35:71–80. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19980401)35:1<71::aid-pros10>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heemers H, Verrijdt G, Organe S, et al. Identification of an androgen response element in intron 8 of the sterol regulatory element-binding protein cleavage-activating protein gene allowing direct regulation by the androgen receptor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30880–30887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401615200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen CD, Welsbie DS, Tran C, et al. Molecular determinants of resistance to antiandrogen therapy. Nat Med. 2004;10:33–39. doi: 10.1038/nm972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ikonen T, Palvimo JJ, Janne OA. Interaction between the amino- and carboxyl-terminal regions of the rat androgen receptor modulates transcriptional activity and is influenced by nuclear receptor coactivators. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:29821–29828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.47.29821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He B, Kemppainen JA, Wilson EM. FXXLF and WXXLF sequences mediate the NH2-terminal interaction with the ligand binding domain of the androgen receptor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:22986–22994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002807200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alen P, Claessens F, Verhoeven G, Rombauts W, Peeters B. The androgen receptor amino-terminal domain plays a key role in p160 coactivator-stimulated gene transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:6085–6097. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.6085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bevan CL, Hoare S, Claessens F, Heery DM, Parker MG. The AF1 and AF2 domains of the androgen receptor interact with distinct regions of SRC1. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:8383–8392. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McEwan IJ. Molecular mechanisms of androgen receptor-mediated gene regulation: structure-function analysis of the AF-1 domain. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2004;11:281–293. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0110281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dehm SM, Tindall DJ. Regulation of androgen receptor signaling in prostate cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2005;5:63–74. doi: 10.1586/14737140.5.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohler JL, Gregory CW, Ford OH, 3rd, et al. The androgen axis in recurrent prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:440–448. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1146-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Titus MA, Schell MJ, Lih FB, Tomer KB, Mohler JL. Testosterone and dihydrotestosterone tissue levels in recurrent prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4653–4657. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stanbrough M, Bubley GJ, Ross K, et al. Increased expression of genes converting adrenal androgens to testosterone in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2815–2825. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]