Abstract

Introduction

The monoclonal antibody (mAb) L8A4, reactive with the epidermal growth factor receptor variant III (EGFRvIII), internalizes rapidly in glioma cells after receptor binding. Combining this tumor specific mAb with the low energy β-emitter 177Lu would be an attractive approach for brain tumor radioimmunotherapy, provided that trapping of the radionuclide in tumor cells after mAb intracellular processing could be maximized.

Materials and Methods

L8A4 mAb was labeled with 177Lu using the acyclic ligands [(R)-2-Amino-3-(4-isothiocyanatophenyl)propyl]-trans-(S,S)-cyclohexane-1,2-diamine-pentaacetic acid (CHX-A″-DTPA), 2-(4-Isothiocyanatobenzyl)-diethylenetriaminepenta-acetic acid (pSCN-Bz-DTPA), and 2-(4-Isothiocyanatobenzyl)-6-methyldiethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (1B4M-DTPA) and the macrocyclic ligands S-2-(4-Isothiocyanatobenzyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-tetraacetic acid (C-DOTA) and α-(5-isothiocyanato-2-methoxyphenyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (MeO-DOTA). Paired-label internalization and cellular processing assays were performed on EGFRvIII-expressing U87.ΔEGFR glioma cells over 24-h to directly compare 177Lu-labeled L8A4 to L8A4 labeled with 125I using either Iodogen or N-succinimidyl 4-guanidinomethyl-3-[125I]iodobenzoate ([125I]SGMIB). In order to facilitate comparison of labeling methods, the primary parameter evaluated was the ratio of 177Lu to 125I activity retained in U87.ΔEGFR cells.

Results

All chelates demonstrated higher retention of internalized activity compared with mAb labeled using Iodogen, with 177Lu/125I ratios of >20 observed for the 3 DTPA chelates at 24 h. When compared to L8A4 labeled using SGMIB, except for MeO-DOTA, internalized activity for 125I was higher than 177Lu from 1–8 h with the opposite behavior observed thereafter. At 24 h, 177Lu/125I ratios were between 1.5 and 3, with higher values observed for the 3 DTPA chelates.

Conclusions

The nature of the chelate used to label this internalizing mAb with 177Lu influenced intracellular retention in vitro, although at early time points, only MeO-DOTA provided more favorable results than radioiodination of the mAb via SGMIB.

Keywords: Lu-177, radioimmunotherapy, epidermal growth factor receptor, DOTA, DTPA

1. Introduction

Mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene are commonly found in many types of human malignancies, with deletions in the extracellular domain being the most frequent. These deletions seem to have an activating effect on the receptor, giving cells expressing these truncated receptors a growth advantage [1, 2]. The most common of these truncated receptors is the type III EGFR deletion mutant (EGFRvIIl, A801EGFR, de2-7 EGFR). Although EGFRvIIl does not bind EGF or other wild-type EGFR-binding ligands, it is constitutively phosphorylated and able to activate downstream signaling cascades via other signal transduction pathways. This difference in EGFRvIIl and EGFR signaling may, at least in part, account for the increased malignancy of EGFRvIII-expressing cells at the molecular level [3, 4]. Because EGFRvIIl is expressed by a variety of human malignancies including breast carcinomas, non-small cell lung carcinomas, ovarian carcinomas and gliomas, but not normal tissues including those expressing wild-type EGFR [5], it is an ideal target for radioimmunotherapy (RIT).

Although there are a variety of radionuclides that are potentially useful for radioimmunotherapeutic applications, due to their ready availability at a moderate cost and the easiness of the labeling chemistry, the beta emitters 131I and 90Y are the most utilized [6]. Each of these two radioisotopes has certain advantages and drawbacks. Yttrium-90 (β; Emax=2.27 MeV; t1/2 = 2.5 d) is a high energy β-emitting radionuclide with a relatively long range in tissues (~12 mm maximum range) with approximately 90% of its emissions absorbed within 0.7 cm. Thus it is ideal for the treatment of large masses of solid tumors especially if the radioactivity is distributed heterogeneously within the tumor. However, for minimum residual disease settings such as RIT of tumor cells remaining after surgical resection of brain tumors, shorter range β emissions would be preferred [7]. Iodine-131 (β; Emax = 0.61 MeV; t1/2 = 8 d) has lower energy beta emissions with a maximum range in tissue of approximately 2.3 mm. It also emits high energy gamma-rays of 364 keV (81%), which can be used for imaging, but can also increase radiation dose to clinical personnel and necessitate patient confinement. In addition, they can harm normal brain tissues limiting the dose that can be administered in the treatment of brain tumors.

One strategy for improving RIT of smaller volume malignancies is to replace 131I with the low energy β-emitter 177Lu. Lutetium-177 has a half life (6.7 d), β-particle energy (497 keV) and resultant tissue range (1.8 mm) that are similar to those of 131I; however, its γ-rays are of considerably lower energy (113, 208 keV) and abundance (7, 11%) than those of 131I. Fortuitous consquences of these differences in γ-ray spectra include simpler radiation protection for patients and personnel, higher quality imaging for dosimetry estimation, and greater amenability to use as an outpatient procedure. Moreover, mAbs labeled with radiometals have generally demonstrated a higher tumor uptake and retention compared with those radioiodinated using conventional methods and have been used increasingly in the detection and therapy of various tumors [8–13]. Finally, 177Lu is readily available in excellent radionuclidic purity and in relatively high specific activity [14].

Over the years, a number of chelating agents have been investigated for labeling proteins and peptides with radiometals, with various derivatives of the acyclic agent DTPA and the macrocyclic agent DOTA being the most widely investigated [15–23]. Because 177Lu, like 90Y, is a bone-seeking element [24], preventing bone-marrow toxicity due to its early release and accumulation in the bone is critical for a successful RIT with 177Lu-labeled mAbs. Labeling of mAbs and their fragments with 177Lu has been achieved utilizing a number of acyclic and cyclic bifunctional chelates including p-SCN-Bz-DTPA, cDTPA, and PA-DOTA [25–29]. Recently, we reported the results from a study comparing acyclic and macrocylic ligands for 177Lu labeling of the murine and chimeric forms of anti-tenascin mAb 81C6 [30]. It was inferred that reducing the normal tissue uptake of 177Lu was influenced by both the characteristics of the mAb and the chelate and that, of the three chelates evaluated — NHS-DOTA, MeO-DOTA, and 1B4M-DTPA — MeO-DOTA yielded the most favorable results with both forms of the mAb.

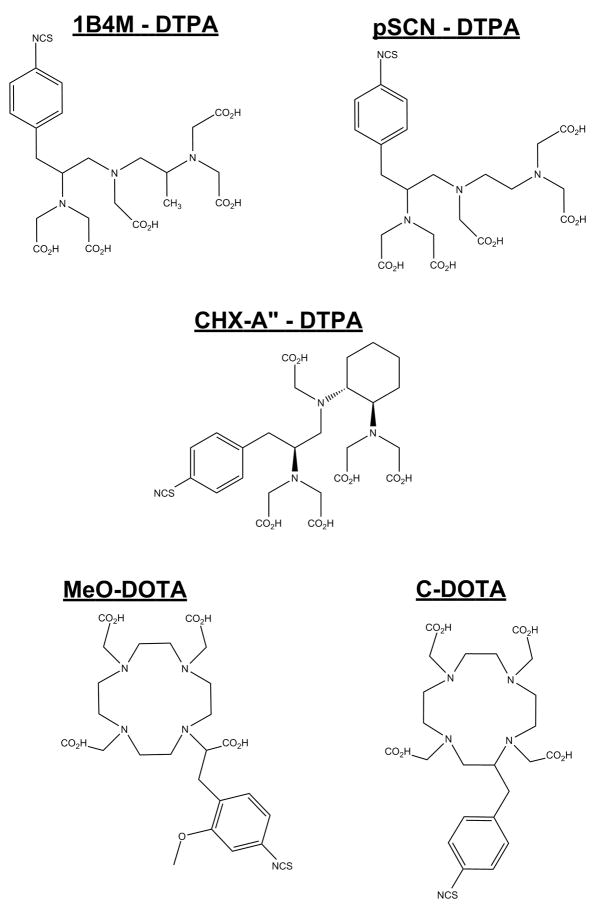

Although it is generally believed that radiometals are preferred to radiohalogens for labeling internalizing mAbs such as those targeting EGFRvIII, there is no clear consensus, to the best of our knowledge, as to the best bifunctional chelate for use with 177Lu or in fact, any radiometal, for this purpose. To that end, in this study, we have labeled the anti-EGFRvIII mAb L8A4 with 177Lu using the acyclic chelators p-SCN-Bz-DTPA, CHX-A″-DTPA, and 1B4M-DTPA as well as with macrocyclic chelators C-DOTA and MeO-DOTA (Figure 1). The intracellular retention of 177Lu activity after incubation of the 177Lu-labeled L8A4 preparations with an EGFRvIII-expressing cell line was determined and compared to that of L8A4 radioiodinated directly and using N-succinimidyl 4-guanidinomethyl-3-[131I]iodobenzoate (SGMIB) [31]. The goal of this study was to determine the extent to which the nature of the BCA played a role in the cellular retention of 177Lu after mAb internalization. Furthermore, we wanted to evaluate the extent to which radiometal labeling of an internalizing mAb offered an advantage over the same mAb radioiodinated with a residualizing radioiodine label such as SGMIB with respect to retention of the radionuclide within the tumor cells.

Figure 1.

Structures of the DOTA and DTPA bifunctional chelates evaluated in this study.

2. Materials and Methods

All solvents were either ACS-certified or HPLC grade, obtained from Sigma Aldrich, and used as received. MeO-DOTA and 1B4M-DTPA were generously donated by Dr. Keith Frank (Iso Therapeutics Group Angleton, TX) and by Dr. Martin Brechbiel (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD), respectively. All other chelators described in this paper were purchased from Macrocyclics (Dallas, Texas), and used as such. [177Lu]Cl3 was obtained from the University of Missouri-Columbia Research Reactor (MURR, Columbia, MO, USA) as a 0.05 N HCl solution.

2.1 mAb L8A4

The development of the murine IgG1 anti-EGFRvIII mAb L8A4 have been described previously [32]. EGFRvIII is characterized by a deletion of amino acids 6 through 273 from the extracellular domain of the wild type EGFR. The truncated EGFRvIII molecule contains a unique primary sequence consisting of an inserted glycine residue at position 6 between amino acid residues 5 and 274. To generate anti-EGFRvIII mAbs, mice were immunized with a 14 mer peptide corresponding to amino acid residues 1-5, the fusion junction glycine, and amino acid residues 274-280. Several weeks later, mice were inoculated with irradiated transfected cells or cell membrane preparations expressing the mutant receptor. Spleen cells were fused with Kearney variant P3X63/Ag8.653 myeloma cells and the resultant hybridomas were screened for reactivity against EGFRvIII-expressing cells. Purification and characterization of L8A4 was carried out following previously described methods [33].

2.2 Buffers

Because DOTA- and DTPA-type chelators form stable inert complexes with many metals including Ca2+ [34], all buffers were prepared so as to minimize metal ion concentrations before their use for radiometal labeling. For a 10x conjugation carbonate buffer, sodium bicarbonate (80.44g), sodium carbonate (4.5 g) and NaCl (175.32 g) were dissolved in 2 L deionized water. This buffer was passed through a conditioned column (2.5 × 18 cm) of Chelex-100 (Na+ form, 200–400 mesh, BioRad). For conditioning, the Chelex column was rinsed with 0.1M HCl (Altrax grade, J.T. Baker), washed with deionized water until the eluent neutral, and then rinsed with ~250 mL of the 10x buffer. For a 30x ammonium acetate buffer, a 5M solution was prepared and treated in a similar manner as above. The concentrated buffers were stored at 4°C. For use in the conjugation reactions, 100 mL of the 10x conjugation buffer was diluted to 1000 mL with 10 mL 0.5M EDTA and 890 mL of OmniTrace Ultra™ water (High Purity, EMD) to obtain a 1x buffer, pH 8.6. The 1x ammonium acetate buffer was prepared similarly by adding 33.3 mL of 30x buffer to 966.7 mL of OmniTrace Ultra™ water without addition of EDTA.

TSK buffer for SEC-HPLC was prepared by dissolving 20g Na2HPO4, 51.5g NaH2PO4, 28.4g Na2SO4, and 1g NaN3 in 2 L deionized water and adjustment of pH to 6.75 with saturated trisodium phosphate solution.

2.3 Chelate and mAb conjugation

L8A4 was derivatized with the bifunctional chelators by incubation of 0.5–2.5mg L8A4 with a 10–20-fold molar excess of the DOTA- or DTPA-type chelator in 10–12 mL 1x pH 8.6 conjugation buffer for 24 h at room temperature. The conjugates were then subjected to centrifugal filtration using a Centricon concentrator (10 kDa MWCO, Amicon) in order to remove unreacted chelate. During this process the buffer was gradually replaced by 1x NH4OAc (pH 7) buffer. To determine the average number of chelates per mAb, a spectrophotometric assay based on the titration of the Pb(II)-Arsenazo(III) complex for macrocyclic ligands [35] and the Y(III)-Arsenazo(III) complex for acyclic ligands was used [36].

2.4 Radiolabeling of L8A4 with 177Lu and 125I

Lutetium-177 (typical specific activity and activity concentration 25 Ci/mg and 1.2 Ci/mL, respectively; 20 μL) was diluted with 80 μL of 0.15 M NH4OAc buffer, pH 7, and an aliquot was mixed with a solution of L8A4-chelate conjugate in the same buffer (200–300 μg in 150 μL; about 1 μg per 2 μCi of 177Lu). The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 1.5 h and at the end of incubation period, quenched with the addition of 3 μL of 0.15M EDTA. The labeled mAb was isolated by gravity gel-filtration chromatography using a PD-10 column eluted with PBS.

Radioiodination of L8A4 with 125I was performed using either Iodogen or the SGMIB method [31]. When the Iodogen method was used, a solution of L8A4 in PBS (pH 7.4; 150 μg in 100 μl) and Na125I (0.5–1.0 mCi) were added to a glass vial coated with 10 μg of Iodogen, and the mixture incubated at room temperature with shaking for 10 min. The labeled mAb was purified as described above. For labeling L8A4 using SGMIB, a solution of the mAb in 0.1 M borate buffer pH 8.5 (80 μL, 1.29 mg/mL) was added to about 1 mCi of [125I]SGMIB, prepared from the corresponding tin precursor [31], and the mixture was incubated for 20 min at room temperature. The labeled mAb was isolated using a Sephadex G-25 PD-10 column (GE Health Care Bio-Sciences AB, Uppsala, Sweden). The integrity of all radiolabeled mAbs was confirmed by size-exclusion HPLC.

2.5 Determination of immunoreactive fraction

The immunoreactivity of radiolabeled L8A4 was evaluated using a magnetic bead assay using beads coated with the extracellular domain of EGFRvIII, or to control for nonspecific binding, BSA, as described [37]. Assays were done in paired-label format using two mAb preparations, one labeled with 125I (SGMIB or Iodogen) and the other with 177Lu. Each labeled mAb (5 ng in 10 μL PBS) in triplicate was added to increasing volumes (10, 20, and 40μL) of both positive- and control beads and the percent of total radioactivity that bound to the beads was determined. The immunoreactive fractions were calculated using the method of Lindmo et al [38].

2.6 Paired-label in vitro internalization assay

The EGFRvIII-expressing cell line used in these studies was U87MG.ΔEGFR, which was established from U87 MG cells by transfection with EGFRvIII cDNA. In cell culture, this line expresses an average of 4–13 × 105 EGFRvIII molecules per cell [39]. Cells were grown in zinc option media (Life Technologies, Inc., Grand Island, NY) containing 10% fetal calf serum and Geneticin sulfate (600 mg/mL). Cells were plated in 6-well plates at a density of 5 × 106 per well and incubated overnight at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. On the day of the assay, the cells were incubated at 4°C for 30 min, after which both labeled (125I and 177Lu) mAbs were added to the wells under conditions of mAb excess. The cells were incubated at 4°C for 1h, washed with fresh medium to remove unbound radioactivity and brought to 37°C. Cells were then processed at 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, and 24 h as follows. Acidic medium (zinc option, pH 2; 1 mL) was added to each well and the cells were incubated for 10 min at 4°C. The acid wash was transferred to a counting vial and the cells were further washed with 1 mL of the acidic medium and pooled with the previous wash. The cells were solubilized by incubation at room temperature with 0.5 mL of 0.5 N NaOH overnight. Cell culture supernatant aliquots, acid washes, and solubilized cell fractions were then counted in the gamma counter using a dual-label program. The protein-associated radioactivity in the cell culture supernatants was determined by incubating 1mL aliquots with 9 mL of MeOH overnight at 4°C.

2.7 Analysis of cell culture supernatant by SDS-PAGE and HPLC

Cell culture supernatant from single-label internalization experiments were analyzed by size-exclusion HPLC using a Tosoh Bioscience, Japan, TSK Gel column (7.5mm × 600mm), eluted at 1 mL/min with TSK buffer on a Beckman Coulter System Gold HPLC, which included a Model 126 programmable solvent module, a Model 168 diode array detector, and a IN/US Systems (Tampa, Florida) β-RAM radioisotope detector. Data analysis was accomplished using Laura Lite software (V3.2 for IN/US) on a PC computer.

SDS-PAGE gel analysis was carried out following standard procedures on samples taken from the same experiments described above in which the HPLC analyses were performed. Samples were analyzed using 15% gels (Ready Gel, Bio-Rad) under non-reducing conditions. Dried gels were analyzed on a Cyclone™ Storage Phosphor System (Packard, Meriden, CT), and the distribution of radioactivity among the different bands was analyzed with an Optiquant Image Analysis Software package (Packard, Meriden, CT) on a PC computer.

3. Results

3.1 Conjugation of chelating agents to L8A4 and radiolabeling

L8A4 was modified by reaction with 3 acyclic DTPA derivatives (p-SCN-Bz-DTPA, CHX-A″-DTPA, or 1B4M-DTPA) and 2 macrocyclic DOTA derivatives (C-DOTA and MeO-DOTA). Conjugation was carried out by using a 20:1 molar excess of chelate-to-mAb, which resulted in an average ratio of about one-to-three chelator molecules per mAb (Table 1). The mAb-chelate conjugates and mAbs were then radiolabeled with either 177Lu or 125I, respectively, at near physiological pH in order to minimize loss of immunoreactivity. Although optimization of 177Lu labeling was not performed in this study, the conditions employed generally resulted in radiochemical yields of 70% or more (Table 1). Incubation at higher temperatures (37°C) and longer times (up to 3 h) did not increase the radiochemical yields significantly. The labeling yield for all studied chelators was between 73% for L8A4-C-DOTA and 86% for 1B4M – DTPA. (Table 1). All 177Lu-labeled L8A4 conjugates exhibited immunoreactive fractions between 60 and 76%. When labeled with 125I, the immunoreactive fraction of L8A4 was similar, between 63% and 80% for both the SGMIB and Iodogen labeling methods. Size-exclusion HPLC of all labeled mAb preparations used in the cell culture experiments showed a single peak with a retention time corresponding to that of intact mAb, with little or no aggregation observed (data not shown).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 177Lu-labeled L8A4 mAb preparations used in the U87MG.ΔEGFR cell culture assays

| Conjugate | Chelates/mAb | Activity incorporated % | Immunoreactive Fraction % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acyclic ligands | |||

| L8A4 - 1B4M - DTPA | 1.1 | 86 | 76 |

| L8A4 - CHX –A″ - DTPA | 0.3 | 76 | 60 |

| L8A4 - pSCN - Bz - DTPA | 0.9 | 81 | 68 |

| Macrocyclic ligands | |||

| L8A4 - C-DOTA | 3.1 | 73 | 63 |

| L8A4 - MeO - DOTA | 2.7 | 80 | 70 |

3.2 Internalization of 177Lu- and 125I-labeled mAbs by U87MGΔEGFR cells

Internalization assays were performed in paired label format on the EGFRvIII expressing U87MGΔEGFR cell line to directly compare the time-dependent movement of radioactivity from the cell surface to both the intracellular compartment and the cell culture supernatant. The goal was to determine the effect of labeling chemistry on the intracellular retention of radioactivity after receptor mediated internalization of L8A4 mAb. The results from a typical experiment, performed with L8A4 labeled with 125I using Iodogen and 177Lu-C-DOTA-L8A4, are shown in Figure 2. With both labeled mAbs, the majority of the radioactivity rapidly was rapidly released from the cell surface and translocated to the cell culture supernatant. The fraction of the radioactivity originally bound to the cells that becomes internalized peaks at 1 h for 125I; on the other hand, internalized counts for 177Lu continued to increase over the 24 h observation period.

Figure 2.

Paired label in vitro internalization of radiolabeled L8A4 mAb by U87MG.ΔEGFR cells. L8A4 was labeled with 125I using Iodogen (top) and with 177Lu via the C-DOTA macrocycle. The percentage of radioactivity initially bound to the cells that was suface bound, internalized and found in the cell culture supernatant as a function of time is shown.

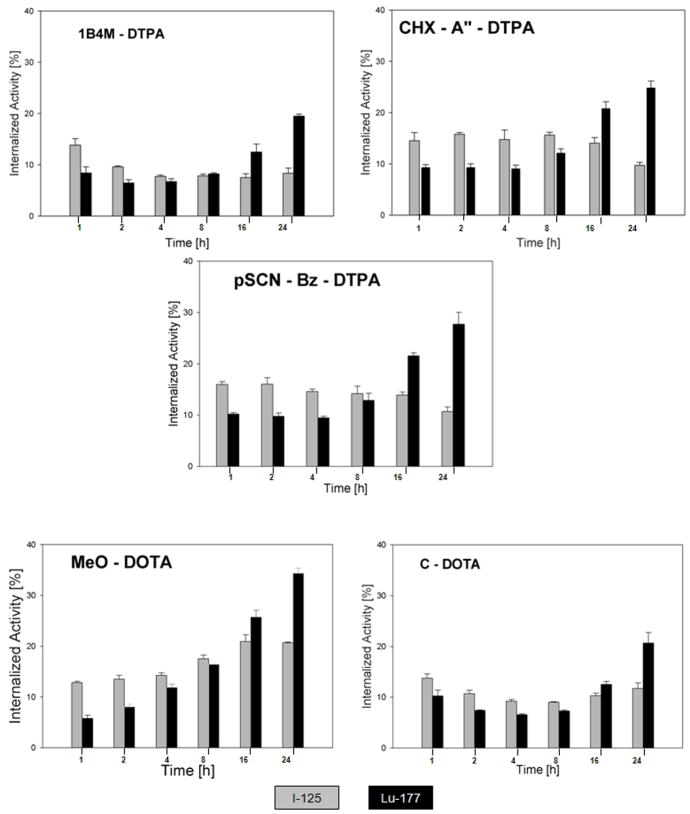

The remainder of our analyses foucused on labeling-method dependent differences in intracellular retention because previous studies have shown a good correlation between this parameter and tumor retention in EGFRvIII expressing xenografts in vivo [37]. With the exception of the 1B4M-DTPA chelate, direct comparisons were done between the 177Lu-labeled L8A4 conjugates and mAb radioiodinated using Iodogen (Figure 3a); all 5 177Lu-labeled mAb conjugates were evaluated in paired-label format in tandem with [125I]SGMIB-L8A4 (Figure 3b). In all experiments, internalized radioiodine activity from mAb labeled using Iodogen declined as a function of time, and the opposite behavior was observed with the 5 different 177Lu-labeled L8A4 chelate conjugates. With SGMIB labeling, the fraction of radioactivity originally bound to the cells that was found in the intracellular compartment remained approximately constant over the 24-h observation period.

Figure 3.

Figure 3a. Paired label comparison of percentage of initially bound counts to U87MG.ΔEGFR cells remaining in the intracellular compartment as a function of time for L8A4 labeled with 177Lu using different bifunctional chelates and L8A4 radioiodinated using Iodogen.

Figure 3b Paired label comparison of percentage of initially bound counts to U87MG.ΔEGFR cells remaining in the intracellular compartment as a function of time for L8A4 labeled with 177Lu using different bifunctional chelates and L8A4 radioiodinated using SGMIB.

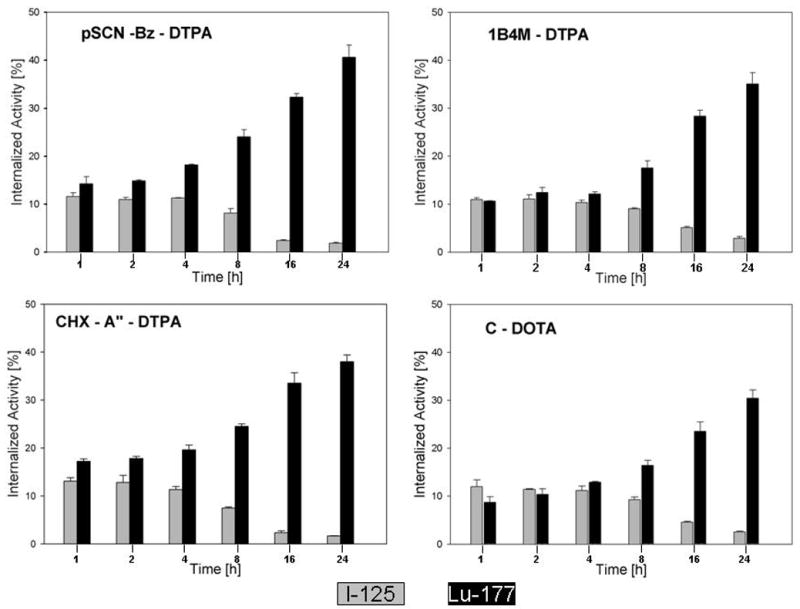

Differences in the retention of radioactivity within the intracellular compartment were also evaluated by determining the ratio of 177Lu and 125I activity for each paired-label experiment. By normalizing the results for the different 177Lu-labeled mAb-chelate conjugates to the same 125I-labeled L8A4 included in the incubation media, the possible effects of differences in experimental conditions that can occur among in vitro sets should be minimized. In Figure 4a, the 177Lu/125I ratios for the C-DOTA, CHX-A″-DTPA, 1B4M-DTPA, and pSCN-Bz-DTPA bifunctional chelates and mAb labeled using Iodogen are presented. Beginning at the 8-h time point, there was a clear advantage in internalized counts for 177Lu compared with 125I with the difference reaching a factor of more than 20 at 24 h for the three DTPA chelates (pSCN-Bz-DTPA, 22.0; CHX-A″-DTPA, 22.9; 1B4M-DTPA, 24.1). In comparison, the 177Lu/125I ratio for C-DOTA was 11.9 at 24 h. The 177Lu/125I internalized counts ratios for all 5 L8A4-chelate conjugates co-incubated with L8A4 labeled via [125I]SGMIB are presented in Figure 4b. Unlike the case when the mAb was radioiodinated using Iodogen, the advantage imparted in retention of radioactivity within the intracellular compartment associated with radiometal labeling compared with [125,177Lu/125I ratios are significantly below unity for the other 4 L8A4-chelate conjugates at 1, 2 and 4 h. Twenty-four hours after incubation of the labeled mAbs with U87MGΔEGFR cells, the 177Lu/125I ratios were: C-DOTA, 1.76 ± 0.24; MeO-DOTA, 2.09 ± 0.17; 1B4M-DTPA, 2.34 ± 0.39; pSCN-Bz-DTPA, 2.58 ± 0.31; and CHX-A″-DTPA, 2.86 ± 0.26.

Figure 4.

Figure 4a. Ratio of 177Lu to 125I activity in U87MG.ΔEGFR cells as a function of time for L8A4 labeled with 177Lu using different bifunctional chelates and L8A4 radioiodinated using Iodogen. (Data from the experiments illustrated in Figure 3a). For comparison, dashed line indicates ratio of unity.

Figure 4b. Ratio of 177Lu to 125I activity in U87MG.ΔEGFR cells as a function of time for L8A4 labeled with 177Lu using different bifunctional chelates and L8A4 radioiodinated using SGMIB. (Data from the experiments illustrated in Figure 3b). For comparison, dashed line indicates ratio of unity.

3.3 Characterization of Cell Culture Supernatant Activity

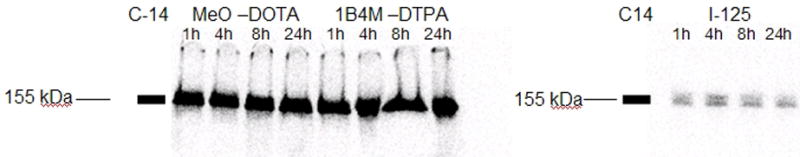

Changes in the distribution of radioactivity on the cell surface, inside the cell and in the cell culture supernatant could reflect a number of processes, including catabolism of the mAb, dissociation of the mAb from the cell surface receptor, and shedding of the mAb-receptor complex. To determine the nature of the radioactivity that was present in the cell culture supernatant, parallel experiments were performed with MeO-DOTA- and 1B4M-DTPA-modified L8A4 with 177Lu as well as L8A4 radioiodinated using SGMIB. The cell culture supernatant was then analyzed by SDS-PAGE and size-exclusion HPLC. Three primary forms of radioactivity would be expected in the cell culture supernatants—intact mAb, mAb-receptor complex, and small molecular weight catabolites. In all cases, radioactivity in the cell culture supernatants at 1, 4, 8, and 24 h was associated with intact mAb as evidenced by SDS-PAGE and HPLC analyses; most of the radioactivity co-eluted with the band/peak corresponding to a molecular weight of 160 kDa (Figures 5 and 6) (results not shown for L8A4-MeO-DOTA and SGMIB). These results suggest that with both radiolabels, most of the activity in the supernatant is caused by loss of intact labeled mAb from the cells.

Figure 5.

SDS-Page analysis of radioactivity present in cell culture supernatant at various time points after binding of radiolabeled L8A4 to U87MG.ΔEGFR cells. Left image; 14C-labeled 155kDa molecular weight standard in the far left lane,177Lu-labeled MeO-DOTA-L8A4 in the next four lanes followed by 1B4M-DTPA-L8A4 in the last four lanes. Right image; 14C-labeled 155kDa molecular weight standard in the far left lane followed by L8A4 labeled using [125I]SGMIB in the next four lanes.

Figure 6.

Size exclusion HPLC analysis of 177Lu activity present in cell culture supernatant 24 h after binding of 177Lu-labeled 1B4M-DTPA-L8A4 to U87MG.ΔEGFR cells. Top; UV trace; botton, radioactivity trace. Arrows indicate elution times of molecular weight standards.

4. Discussion

Radionuclides emitting short range β-particles are an important part of the radiotherapeutic armamentarium. They represent a reasonable compromise between the need to compensate for heterogeneities in labeled molecule accumulation, requiring longer range radiation, and the desire to minimize dose to normal tissues from decays originating in tumor, requiring shorter range radiation. One setting in which striking this balance is of critical importance is in the treatment of malignant brain tumors, characterized by both a propensity for local recurrence as well as the infiltration of small foci of tumor cells within normal brain [40]. For this reason, the majority of targeted therapy trials for the treatment of gliomas have utilized mAbs labeled with the low-energy β-emitter,131I [7]. However, with 177Lu becoming more widely available at a reasonable cost, it offers an attractive alternative to 131I for the treatment of residual disease. Lutetium-177 offers several potential advantages for targeted radiotherapy compared with 131I including a) shorter β path length (mean range 670 μm), b) shorter half life, c) γ-rays with better characteristics for imaging and d) lower γ-ray energies and intensities, resulting in less radiation dose to whole brain and to personnel involved in the radioimmunotherapy procedures.

One of the most attractive molecular targets for the radionuclide therapy of brain tumors as well as several other types of malignancies is EGFRvIII, which is expressed at high levels on these malignant cell populations but not on normal tissues [1–5]. This is an important distinction from the molecular target involved in the vast majority of clinical radioimmunotherapy trials because tenascin-C is expressed at high levels in normal liver and spleen [7]. From a radiochemistry perspective, an important characteristic of mAbs such as L8A4 that target EGFRvIII is that they are rapidly internalized into tumor cells after binding to the receptor, and undergo extensive intracellular degradation [39]. Our past efforts to label anti-EGFRvIII mAbs focused on radioiodination approaches, from which it was ascertained that trapping of labeled catabolites in EGFRvIII-expressing tumor cells could best be achieved if the radioiodinated prosthetic group was either positively [31,37] or negatively [41, 42] charged.

The primary goal of this study was to determine the best among a number of available macrocyclic and acyclic chelating agents for labeling the anti-EGFRvIII mAb L8A4 with 177Lu. Although the advange of radiometal labeling compared with conventional radioiodination for maximizing intracellular retention of radioactivity after labeled mAb internalization is well known [11,12], little if any information is available comparing different bifunctional chlelates with the same radiometal in this regard. Our experience with the radiohalogenation of internalizing mAbs noted above suggests that the charge of the labeled prosthetic group is a important factor. The extent to which the charge of the labeled chelate plays an analogous role has not been extensively investigated. However, it is known that both lipophilicity and the net charge of the metal-chelate complexes have been shown to have significant effect on the biological behavior of mAbs labeled with copper radionuclides, 64Cu and 67Cu [43].

By considering the structural features of the chelating agents used in this study, especially the number of acetic acid residues, one would expect to see differences in cell uptake/retention based on the net charge of the 177Lu-chelate complex, presumably as its lysine conjugate, that would be generated after proteolysis of the labeled mAb [44,45]. On this basis, one would expect the intracellular retention of 177Lu with the acyclic ligands to be greater than that of the macrocyclic ligands because the former provide a bigger negative net charge that the latter (negative 2 vs. negative 1). Normalizing to the same radioiodinated mAb preparation facilitated comparison in the intracellular trapping properties of the various chelates (Figure 4). As predicted, 177Lu/125I intracellular counts ratios were significantly higher for DTPA-based compared with DOTA-based chelates.

Differences among the pSCN-Bz-DTPA, CHX-A″-DTPA and 1B4M-DTPA chelates were not striking even though the resultant metal complexes might be expected to exhibit differences in stability. The CHX-A′ DTPA with its more rigid cyclohexyl ring as part of the backbone would be expected to confer a more rigid conformation of the ensuing 177Lu complex leading to a higher degree of retention compared to the other DTPA derivatives. Likewise, 1B4M-DTPA features a methyl-group in position 4, which is expected to impart conformational stability to its radiometallated complex, it actually yielded the lowest cell retention amongst the acyclic chelators studied. This suggests that under these in vitro conditions, charge of the complex may be a more important factor than its stability in determining intracellular retention of radiometal activity for internalizing mAbs labeled with 177Lu and possibly other radiometals. Thus, we speculate that the rate limiting step governing the loss of 177Lu from target cells after internaliziation of this receptor-mAb complex, is not dissociation of the metal from the chelate but transport of the chelate complex or its lysine adduct across lysosomal and cell membranes. However, this is clearly not the case for all chelate radiometal combinations, as reflected by the results of a study comparing other internalizing mAbs labeled with 111In using earlier generation chelates [18].

It is important to note that even with the optimal ligand systems, less than 40% of the activity originally bound to the cells remained cell associated after 24 h. While this could reflect gradual loss of lower molecular weight catabolites from the cell, it could also be due to recycling of the labeled mAb receptor complex to the cell surface, followed by loss of the labeled complex and/or labeled mAb into the cell culture supernatant. Analyses by HPLC and SDS-PAGE of cell culture supernatants for L8A4 labeled with 177Lu using MeO-DOTA and 1B4M-DOTA, and with 125I using SGMIB indicated that nearly all of the radioactivity was present as intact mAb. Intact mAb also was the predominant species in cell culture supernatant in a similar study with anti prostate specific membrane antigen mAbs labeled with 111In via a DOTA anhydride bifunctional chelate [18]. Whether this reflected loss of initially bound mAb from the cell surface or recycling of labeled mAb receptor complex to the cell surface, followed by dissociation and loss of the labeled mAb into the cell culture supernatant, could not be discerned.

Our results confirm the anticipated superiority of radiometal labeling compared with a direct radioiodination method for maximizing the cellular retention of radioactivity after internalization of a labeled mAb [11,12,18]. On the other hand, similar comparisons with this internalizing mAb labeled with 125I using SGMIB suggest that the cellular retention advantage for radiometals does not reflect an intrinsic property of metals vs. halogens. Indeed, with the exception of mAb labeled using the MeO-DOTA bifunctional chelate, cellular retention of 125I was greater than that of 177Lu at early time points. The fact that this behavior is reversed after more prolonged incubation periods suggests that the catabolism of internalizing mAbs is a complex process, with the potential implication that the preferred labeling approach may depend on the half life of the radionuclide. Clearly, maximizing intracelluar retention in vitro is not the only criterion in selecting the best labeling method for use with this promising anti-EGFRvIII mAb. In vivo comparisons of L8A4 labeled using these different bifunctional chelates and radioiodination methods are in progress to select the best method to take forward for clinical evaluation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grants NS20023 and CA42324 from the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to thank Dr. Darell Bigner, Department of Pathology, Duke University Medical Center, for providing the L8A4 antibody. MeO-DOTA and 1B4M-DTPA were generously donated by Dr. Keith Frank, IsoTherapeutics Group Angleton, TX, and by Dr. Martin Brechbiel, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, respectively.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Garcia de Palazzo IEAG, Sundareshan P, Wong AJ, Testa JR, Bigner DD, Weiner LM. Expression of Mutated Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor by Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3217–3220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwechheimer K, Huang S, Cavenee WK. EGFR gene amplification-rearrangement in human glioblastomas. Int J Cancer. 1995;62:145–148. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910620206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antonyak MA, Moscatello DKWA. Constitutive activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase by a mutant epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2817–2822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moscatello DK, Holgado-Madruga M, Emlet DR, et al. Constitutive activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase by a naturally occurring mutant epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:200–206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wikstrand CJ, Reist CJ, Archer GE, Zalutsky MR, Bigner DD. The class III variant of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFRvIII): characterization and utilization as an immunotherapeutic target. J NeuroVirol. 1998;4:148–158. doi: 10.3109/13550289809114515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Donoghue JA, Bsrdies M, Wheldon TE. Relationships between Tumor Size and Curability for Uniformly Targeted Therapy with Beta-Emitting Radionuclides. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:1902–1909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reardon DA, Zalutsky MR, Bigner DD. Antitenascin-C monoclonal antibody radioimmunotherapy for malignant glioma patients. Expert Rev Anti-Cancer Therapy. 2007;7:675–687. doi: 10.1586/14737140.7.5.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeNardo GL, DeNardo SJ, Miyao NP. Non-dehalogenation mechanisms for excretion of radioiodine after administration of labeled antibodies. Int J Biol Markers. 1988;3:1–9. doi: 10.1177/172460088800300101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanna R, Ong GL, Mattes MJ. Processing of Antibodies Bound to B-Cell Lymphomas and Other Hematological Malignancies. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3062–3068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heeg MJ, Jurisson SS. The Role of Inorganic Chemistry in the Development of Radiometal Agents for Cancer Therapy. Acc Chem Res. 1999;32:1053–1060. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Press OW, Shan D, Howell-Clark J, Eary J, Appelbaum FR, Matthews D, et al. Comparative Metabolism and Retention of Iodine-125, Yttrium-90, and Indium-111 Radioimmunoconjugates by Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2123–2129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shih LB, Thorpe SR, Griffiths GL, Diril H, Ong GL, Hansen HJ, et al. The Processing and Fate of Antibodies and Their Radiolabels Bound to the Surface of Tumor Cells In Vitro: A Comparison of Nine Radiolabels. J Nucl Med. 1994;35:899–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Witzig TE, Gordon LI, Cabanillas F, Czuczman MS, Emmanouilides C, Joyce R, et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of Yttrium-90-Labeled Ibritumomab Tiuxetan Radioimmunotherapy Versus Rituximab Immunotherapy for Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Low-Grade, Follicular, or Transformed B-Cell Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2453–2463. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Volkert WA, Goeckler WF, Ehrhardt GJ, Ketring AR. Therapeutic radionuclides: Production and decay property considerations. J Nucl Med. 1991;32:174–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahlgren S, Orlova A, Rosik D, Sandström M, Sjöberg A, Baastrup B, et al. Evaluation of Maleimide Derivative of DOTA for Site-Specific Labeling of Recombinant Affibody Molecules. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008;19:235–243. doi: 10.1021/bc700307y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banerjee S, Das T, Chakraborty S, Samuel G, Korde A, Srivastava S. 177Lu-DOTA-lanreotide: a novel tracer as a targeted agent for tumor therapy. Nuclear Medicine and Biology. 2004;31:753–759. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parry JJ, Kelly TS, Andrews R, Rogers BE. In Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation of 64Cu-Labeled DOTA-Linker-Bombesin(7–14) Analogues Containing Different Amino Acid Linker Moieties. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007;18:1110–1117. doi: 10.1021/bc0603788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith-Jones PM, Vallabahajosula S, Goldsmith SJ, Navarro V, Hunter CJ, Bastidas D, et al. In Vitro Characterization of Radiolabeled Monoclonal Antibodies Specific for the Extracellular Domain of Prostate-specific Membrane Antigen. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5237–5243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bousquet JC, Saini S, Stark DD, Hahn PF, Nigam M, Wittenberg J, et al. Gd-DOTA: characterization of a new paramagnetic complex. Radiology. 1988;166:693–698. doi: 10.1148/radiology.166.3.3340763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McMurry TJ, Brechbiel M, Kumar K, Gansow OA. Convenient synthesis of bifunctional tetraaza macrocycles. Bioconjugate Chem. 1992;3:108–117. doi: 10.1021/bc00014a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moi MK, Meares CF, DeNardo SJ. The peptide way to macrocyclic bifunctional chelating agents: synthesis of 2-(p-nitrobenzyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-N,N′,N″,N‴-tetraacetic acid and study of its yttrium(III) complex. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1988;110:6266–6267. doi: 10.1021/ja00226a063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parker D. Tumour targeting with radiolabelled macrocycle–antibody conjugates. Chem Soc Rev. 1990;19:271–291. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woods M, Kovacs Z, Kiraly R, Brucher E, Zhang S, Sherry AD. Solution Dynamics and Stability of Lanthanide(III) S-2-Nitrobenzyl)-DOTA Complexes. 2004:2845–2851. doi: 10.1021/ic0353007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Durbin P. Metabolic characteristics within a chemical family. Health Phys. 1960;2:225–228. doi: 10.1097/00004032-195907000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brouwers AH, van Eerd JEM, Frielink C, Oosterwijk E, Oyen WJG, Corstens FHM, et al. Optimization of radioimmunotherapy of renal cell carcinoma: Labeling of monoclonal antibody cG250 with 131I, 90Y, 177Lu, or 186Re. J Nucl Med. 2003;45:327–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clauhan SC, Jain M, Moore ED, Wittel UA, Li J, Gwilt PW, et al. Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of 177Lu-labeled multivalent single-chain Fv construct of the pancarcinoma monoclonal antibody CC49. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:264–273. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1664-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grunberg J, Novak-Hofer I, Honer M, Zimmermann K, Knogler K, Blauenstein P, et al. In vivo evaluation of 177Lu- and 67/64Cu-labeled recombinant fragments of antibody chCE7 for radioimmunotherapy and PET imaging of L1-CAM-positive tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5112–5120. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Postema EJ, Frielink C, Oyeen WJ, Raemakers JM, Goldenberg DM, Corstens FH, et al. Biodistribution of 131I-, 186Re-177Lu-, and 88Y-labeled hLL2 (Epratuzumab) in nude mice with CD22-positive lymphoma. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2003;18:525–533. doi: 10.1089/108497803322287592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tijink BM, Neri D, Leemans CR, Budde M, Dinkelborg LM, Stigter-van Walsum M, et al. Radioimmunotherapy of head and neck cancer xenografts using 131I-labeled antibody L19-SIP for selective targeting of tumor vasculature. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1127–1135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yordanov AT, Hens M, Pegram CN, Bigner DD, Zalutsky MR. Antitenascin antibody 81C6 armed with 177Lu: in vivo comparison of macrocyclic and acyclic ligands. Nuclear Medicine and Biology. 2007;34:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaidyanathan G, Affleck D, Li J, Welsh P, Zalutsky MR. A Polar Substituent-Containing Acylation Agent for the Radioiodination of Internalizing Monoclonal Antibodies: N-Succinimidyl 4-Guanidinomethyl-3-[131I]iodobenzoate ([131I]SGMIB) Bioconjugate Chem. 2001;12:428–438. doi: 10.1021/bc0001490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Humphrey PA, Wong AJ, Vogelstein B, Zalutsky MR, Fuller GN, Archer GE, et al. Anti-Synthetic Peptide Antibody Reacting at the Fusion Junction of Deletion-Mutant Epidermal Growth Factor Receptors in Human Glioblastoma. Proc Nati Acad Sci. 1990;87:4207–4211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.11.4207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wikstrand CJ, Hale LP, Batra SK, Hill L, Humphrey PA, Kurpad SK, et al. Monoclonal antibodies against EGFRvllI are tumor specific and react with breast and lung carcinomas and malignant gliomas. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3140–3148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stetter H, Frank W. Complex formation with tetraazacycloalkane-N,N′,N″,N‴ tetraacetic acids as a function of ring size. Angewandte Chemie. 1976;88:760. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pippin CG, Parker T, McMurry TJ, Brechbiel MW. Spectrophotometric method for the determination of a bifunctional DTPA ligand in DTPA -monoclonal antibody conjugates. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 1992;3:342–344. doi: 10.1021/bc00016a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Milenic DE, Garmestani K, Chappell LL, Dadachova E, Yordanov A, Ma D, Schlom J, Brechbiel MW. In vivo comparison of macrocyclic and acyclic ligands for radiolabeling of monoclonal antibodies with 177Lu for radioimmunotherapeutic applications. Nucl Med Biol. 2002;29:431–442. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(02)00294-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foulon CF, Reist CJ, Bigner DD, Zalutsky MR. Radioiodination via D-amino acid peptide enhances cellular retention and tumor xenograft targeting of an internalizing anti-epidermal growth factor receptor variant III monoclonal antibody. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4453–4460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindmo T, Boven E, Cuttitta F, Fedorko J, Bunn PA., Jr Determination of the immunoreactive fraction of radiolabeled monoclonal antibodies by linear extrapolation to binding at infinite antigen excess. J Immunol Methods. 1984;72:77–89. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(84)90435-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reist CJ, Archer GE, Kurpad SN, Wikstrand CJ, Vaidyanathan G, Willingham MC, et al. Tumor-specific Anti-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Variant III Monoclonal Antibodies: Use of the Tyramine-Cellobiose Radioiodination Method Enhances Cellular Retention and Uptake in Tumor Xenografts. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4375–4382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Enam SA, Rosenblum ML, Edvardsen K. Role of extracellular matrix in tumor invasion: migration of glioma cells along fibronectin-positive mesenchymal cell processes. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:599–607. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199803000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shankar S, Vaidyanathan G, Affleck DJ, Welsh P, Zalutsky MR. N-succinimidyl 3-[131I]iodo-4-phosphonomethylbenzoate, A negatively charged substitutent-bearing acylation agent for the radioiodination of peptides and mAbs. Bioconjugate Chem. 2003;14:331–341. doi: 10.1021/bc025636p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vaidyanathan G, Alston KL, Bigner DD, Zalutsky MR. Nε-(3-[*I]iodobenzoyl)-Lys5-Nα–maleimido-Gly1-GEEEK ([*I]IB-Mal-D-GEEEK): A radioiodinated prosthetic group containing negatively charged D-glutamates for labeling internalizing monoclonal antibodies. Bioconjugate Chem. 2006;17:1085–1092. doi: 10.1021/bc0600766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anderson CJ, Welch M. Radiometal-Labeled Agents (Non-Technetium) for Diagnostic Imaging. Chem Rev. 1999;99:2219–2234. doi: 10.1021/cr980451q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Franano FN, Edwards WB, Welch MJ, Duncan JR. Metabolism of receptor targeted 111In-DTPA-glycoproteins: identification of 111In-DTPA-epsilon-lysine as the primary metabolic and excretaory product. Nucl Med Biol. 1994;21:1023–1034. doi: 10.1016/0969-8051(94)90174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rogers BE, Franano FN, Duncan JR, Edwards WB, Anderson CJ, Connett JM, et al. Identification of metabolites of 111In-diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid-monoclonal antibodies and antibody fragments in vivo. Cancer Res. 1995;55(suppl):5714s–5720s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]