Abstract

Study Objective:

To evaluate whether socioeconomic status (SES) has a role in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) patients' decision to accept continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment.

Design:

Cross-sectional study; patients were recruited between March 2007 and December 2007.

Setting:

University-affiliated sleep laboratory.

Patients:

162 consecutive newly diagnosed (polysomnographically) adult OSAS patients who required CPAP underwent attendant titration and a 2-week adaptation period.

Results:

40% (n = 65) of patients who required CPAP therapy accepted this treatment. Patients accepting CPAP were older, had higher apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) and higher income level, and were more likely to sleep in a separate room than patients declining CPAP treatment. More patients who accepted treatment also reported receiving positive information about CPAP treatment from family or friends. Multiple logistic regression (after adjusting for age, body mass index, Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and AHI) revealed that CPAP purchase is determined by: each increased income level category (OR, 95% CI) (2.4; 1.2–4.6), age +1 year (1.07; 1.01–1.1), AHI ( ≥ 35 vs. < 35 events/hr) (4.2, 1.4–12.0), family and/or friends with positive experience of CPAP (2.9, 1.1–7.5), and partner sleeps separately (4.3, 1.4–13.3).

Conclusions:

In addition to the already known determinants of CPAP acceptance, patients with low SES are less receptive to CPAP treatment than groups with higher SES. CPAP support and patient education programs should be better tailored for low SES people in order to increase patient treatment initiation and adherence.

Citation:

Simon-Tuval T; Reuveni H; Greenberg-Dotan S; Oksenberg A; Tal A; Tarasiuk A. Low socioeconomic status is a risk factor for CPAP acceptance among adult OSAS patients requiring treatment. SLEEP 2009;32(4):545–552.

Keywords: CPAP, OSAS, patient support, socioeconomic status, treatment acceptance

CONTINUOUS POSITIVE AIRWAY PRESSURE (CPAP) IS THE TREATMENT OF CHOICE FOR PATIENTS WITH OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNEA SYNDROME (OSAS). IF used on a regular basis, CPAP can effectively reduce the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI), decrease daytime sleepiness,1,2 improve sleep quality and quality of life for both the patient and partner,3 and reduce the risk of cardiovascular events.4–6

Despite the increase in CPAP treatment options (i.e., bilevel positive airway pressure, autoadjusting CPAP), treatment acceptance and adherence are low. It has been estimated that 15% to 30% of patients do not accept CPAP treatment from the outset.7 The decision to embrace CPAP occurs during the first few days of treatment.3,8–10 The issues influencing CPAP acceptance (or non-acceptance) are complicated, involving behaviors by the physician, patient, and health care system. Currently, no single factor has been consistently identified as predictive of CPAP acceptance and adherence.1,10,11–17 CPAP support programs and patient education increase patient acceptance during treatment initiation,18–20 since they improve patients' symptoms and their perception about CPAP treatment, driving patients to seek therapy.19–21

Little is known about the role of socioeconomic status (SES), determined by income level,22–24 on the decision to accept CPAP treatment. Patients with OSAS25 and people with low SES have higher rates of obesity, glucose intolerance, and cigarette smoking.4,6,26,27 Health literacy among low SES patients was found to be a barrier to treating obesity and managing cardiovascular disease (CVD).22,24,28–30 Patients with lower SES have a greater likelihood of exposure to SES risk behaviors, including nonattendance for health checkups and poor compliance, resulting in increased CVD morbidity and mortality risk.24,27 Patients with OSAS recruited from hospitals serving low SES neighborhoods,28 compared with hospitals serving high SES populations, had a greater body mass index (BMI) and more comorbidity, despite similar demographics. Forty-two percent of patients with OSAS from hospitals serving minority groups failed to follow up for CPAP treatment, compared with 7% in the voluntary hospital group.28 This finding may be related to health literacy and low SES behavior. It is possible that the poor compliance with various interventions may impair treatment acceptance among low-SES OSA patients requiring CPAP.

The aim of the study was to evaluate whether SES is an independent factor affecting CPAP acceptance to commence (purchase) treatment.

METHODS

Experimental Design

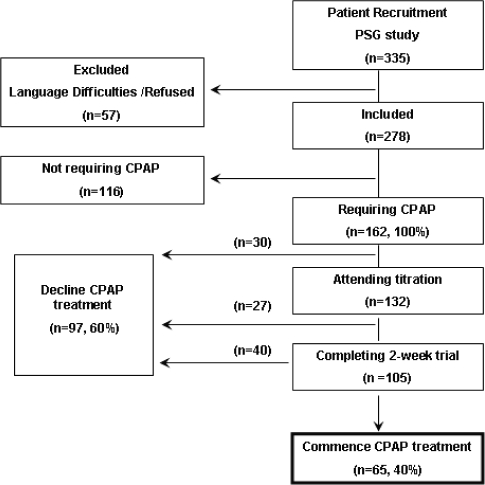

Cross-sectional prospective study in the university-affiliated Sleep-Wake Disorders Center in Beer-Sheva; > 85% of our patients are enrollees of Clalit Health Care Services (CHS), a Health Maintenance Organization. Between March 2007 and December 2007 we consecutively recruited referred subjects (n = 335) suspected of having OSA; subjects were ≥ 18 years of age and naïve to CPAP (Figure 1). One hundred sixty-two patients with OSAS were recommended for CPAP therapy according to the following criteria:31 apnea hypopnea index (AHI) ≥ 30/h; AHI of 5 to 30/h accompanied by Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) score ≥ 1032 and/or documented CVD and/or hypertension (HTN). The study excluded patients with mild-moderate OSAS31 and patients with atypical health care consumption, i.e., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring bilevel positive airway pressure, genetic disorders, cancer, or autoimmune disorders. Medical care for these patients is subsidized by CHS considerably more than for the general population.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the stages of the diagnostic and therapeutic process, the number of patients requiring or not requiring CPAP commencing or declining treatment. Declined – patients who declined treatment during the different stages.

The institutional ethics committee approved the protocol. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

CPAP support program was performed as part of our routine in our sleep center. We used a modification of the approach previously described by Popescu et al.19 Patients were seen by otolaryngology surgeons or pulmonologists before their diagnostic study. All subjects discussed PSG results and later (within 2 weeks) the need for CPAP therapy with a sleep physician. Upon receiving results of the CPAP titration study, patients were encouraged by sleep specialists to undergo a mandatory 2-week adaptation period in order to commence treatment, and were advised that this treatment required out-of-pocket payment (about 30% of CPAP cost) in addition to the cost participation by CHS, according to the Israeli National Health Insurance Law. If the patient agreed, he/she participated in a pre-adaptation session in the sleep laboratory with a sleep technician. During this session, patients received further explanation of the pathophysiology of OSAS, its risks and treatment, and an explanation of the upcoming adaptation trial. A 2-week period of adaptation with the CPAP device at home was offered and encouraged. During the pre-adaptation period, patients were fitted with an appropriate mask selected from a variety of CPAP devices and masks, and were given humidifiers as needed. Following that, patients were instructed how to use the device at home and received a brochure highlighting helpful tips regarding common problems with CPAP use. During the adaptation trial, when patients used the device at home, a technologist was in contact with the patient by phone or laboratory appointment at least once a week, as needed. In case of problems such as nasal dryness or mask discomfort, patients were encouraged to contact the CPAP technologist to solve the problem. Patients were encouraged to try masks and machines from a variety of CPAP manufacturers free of charge. Approximately 10% of the patients received an additional 1 to 2 of CPAP use to ensure patient satisfaction. At the end of the adaptation period, initiation of CPAP treatment was discussed. Four to six weeks following the conclusion of the adaptation period, the final decision of our patients to commence (purchase) or decline CPAP treatment was confirmed.

Polysomnographic Study (PSG)

Overnight PSG monitoring was performed according to previously described methods.33 Subjects reported to the laboratory at 20:30 and were discharged at 06:00 the following morning. Subjects were encouraged to maintain their usual daily routine and to avoid any caffeine and/or alcohol intake on the day of the study. Shift workers did not perform the PSG study in the week following shift duty. PSG study included electroencephalography (EEG), electrooculography (EOG), electromyography (EMG) applied over the submental muscles and bilateral anterior tibialis muscles for detection of periodic limb movements, electrocardiography (ECG), respiratory activity (airflow and chest/abdominal effort), body position, and oxygen saturation (SpO2). Scoring was done by a trained technician and reviewed by a polysomnographer, and a report sent to the referring physician. Obstructive apnea was defined as an episode of complete cessation of breathing (airflow reduction > 80%) ≥ 10 sec with continuing inspiratory effort. A hypopnea was scored when continuing inspiratory effort was accompanied by a reduction ≥ 50% in airflow, resulting in either an arousal or oxygen desaturation ≥ 4%. The AHI was calculated as the number of respiratory events (apnea/hypopnea) per hour of sleep. A sleep physician explained the significance of the results to the patients (prior to the CPAP support program) with recommendations for treatment. CPAP titration was performed during an approximately 2-week period following PSG study using attendant autotitration CPAP protocol.

Socioeconomic status was evaluated according to individual monthly income.15,22,23,27 We asked participants to rate their individual monthly income level as below (< 20%), equal to (± 20%), or above (> 20%) the average monthly income level in Israel (according to Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics data). Low SES people were defined as subjects with a monthly income below the national average.27

Comorbid Diagnoses

We reviewed the accumulated diagnoses of CVD along with their respective International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes27 including hypertension [401–405], ischemic heart disease [410–414], cardiac arrhythmia, congestive heart failure, valvular cardiac disease, cerebrovascular accident [426–438], and peripheral vascular disease [443]. CVD diagnosis23 included at least one of the following ICD-9 codes: 410–414, 426–438, or 443.

Questionnaires: The following questionnaires were completed prior to the PSG study.

Each individual's lifestyle, sleeping habits, and clinical history were recorded using a standardized self-administered questionnaire.27,34 Life habits were evaluated by determining smoking habits and consumption of coffee and tea.22 The ESS was used to assess excessive daytime sleepiness.32 In addition, for the purpose of this study we explored the following questions: “Does your partner sleep in a separate room, on regular basis, due to your snoring problems? Yes/no”; “Did your primary care physician explain to you what medical problem/s could be diagnosed in a sleep study? Yes/no/not enough”; “Did your primary care physician explain to you what obstructive sleep apnea syndrome is and what treatments options are available? Yes/no”; “Did you receive information from a person being treated with CPAP? Yes/no”; “Was his/her experience with CPAP positive/negative/neutral?”

At the conclusion of the CPAP support program a second questionnaire was used to explore reasons for commencing treatment; for example: “CPAP solved my snoring problems, yes/no”; “CPAP treatment reduced my excessive daytime sleepiness, yes/no”; “CPAP treatment improved my sleep, yes/no”; “Do you think CPAP treatment will improve your risks of further morbidities (i.e., CVD, HTN)? yes/no/don't know”; “Do you acknowledge the fact that CPAP treatment is the best treatment available for you? yes/no”. Reasons for declining CPAP treatment included side effects (variety of side effects). Patients were asked to mark whether the following options were applicable to them “I am interested in other treatment options”; “I could not adapt to CPAP”; “I feel better and don't need this treatment”; “I was not encouraged to commence CPAP by my partner, my physician, family/friend”. Patients were asked if there are other reasons for not accepting CPAP. We also asked whether cost was a financial barrier to purchase CPAP: “I cannot purchase CPAP since it is too expensive for me (yes/no)”.

Cases that were dropped prior to the CPAP support program (see below) were interviewed via telephone.

Data and Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using STATA software (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Continuous variables are presented as mean with standard deviation, unless otherwise specified. We used t-test, the chi-square test (χ2), and one-way analysis of variance to determine statistical significance between variables. Following descriptive and quantitative analysis, logistic regression analysis was used to calculate odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Logistic regression analysis was used to investigate variables influencing CPAP acceptance (i.e., purchase) 4 to 6 weeks following conclusion of the adaptation period. Independent variables included age, sex, HTN, CVD, smoking, monthly income level, PSG findings (AHI, T90%), ESS, and support from family and/or friends. The multiple logistic regression model was fitted to establish the primary determinants of CPAP acceptance and purchase (dependent variables). The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC curve) was calculated for the model. The null hypothesis was rejected at the 5% level.

RESULTS

Thirty-four patients refused to be included in the study, and 23 patients were excluded because of language difficulties with Hebrew. These patients (n = 57) were not significantly different from the 278 other initial participants with regard to sex (P = 0.46), AHI (P = 0.25), ESS (P = 0.88), or BMI (P = 0.44). Of the OSAS patients (n = 278), 74.7% of those requiring CPAP and 55.2% of those not requiring CPAP were men (P = 0.001) (Table 1). Patients requiring CPAP (n = 162) were older, had higher AHI, ESS, T90%, and higher rates of HTN and/or CVD than patients not requiring CPAP (n = 116). Only 16% and 17% of OSA patients requiring or not requiring CPAP, respectively, reported that they received some information from their primary care physician regarding the diagnostic procedure they underwent in the sleep laboratory. Fifty-seven patients (35%) requiring CPAP never started the support program and did not commence therapy after initial diagnosis or CPAP titration. Patients accepting CPAP were older, had more severe AHI, higher T90, and higher income level, reported receiving positive information about CPAP treatment from family/friends being treated with CPAP; more subjects reported sleeping in a separate room compared to patients declining CPAP treatment (Table 2). Years of education were 9.9 ± 3.4, 13.1 ± 3.0, and 15.2 ± 3.4 among low, average, and high-income level patients, respectively (P < 0.001). Both CPAP-accepting and CPAP-declining patients had similar levels of recognition that OSAS is a serious life-threatening condition, 54.7% vs. 48.4%, respectively (P = 0.4, χ2 = 0.6). Of CPAP-accepting patients, 37.5% reported (Table 2) that they received positive information from family and/or friends treated with CPAP compared to 19.5% of CPAP-declining patients (P = 0.021). Information provided by primary care physicians encouraged patients to commence CPAP treatment and increased the odds of CPAP acceptance (OR, 2.34, 1.06 to 5.2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of OSAS Patients

| OSA patients not requiring CPAP | OSA patients requiring CPAP | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 116 | 162 | |

| Males (%) | 55.2 | 74.7 | 0.001 |

| Age (years) | 49.7 ± 13.2 | 54.9 ± 12.0 | 0.0007 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.3 ± 7.3 | 32.3 ± 5.4 | 0.01 |

| AHI (events/h) | 9.3 ± 8.5 | 40.8 ± 24.4 | < 0.0001 |

| T90 (%) | 6.5 ± 16.8 | 14.8 ± 21.9 | 0.0004 |

| ESS (score) | 7.0 ± 4.2 | 10.4 ± 4.6 | < 0.0001 |

| HTN and/or CVD (prevalence) | 37.9% | 58.02% | < 0.0001 |

| Smoking (pack/year) | 30.5 ± 31.8 | 30.8 ± 30.3 | 0.957 |

| Education (years) | 11.9 ± 3.6 | 12.7 ± 3.7 | 0.057 |

| Income | |||

| Low | 30.4% | 31.8% | 0.562 |

| Average | 49.1% | 43.1% | |

| High | 20.5% | 25.2% |

AHI, apnea-hypopnea index; BMI, body mass index; ESS, Epworth Sleepiness Scale, T90, percent sleeping time with oxygen saturation was below 90%; HTN, hypertension; CVD, cardiovascular disease. Values are mean ± SD.

Table 2.

Characteristics of OSAS Patients Accepting or Declining CPAP Treatment

| CPAP Declining | CPAP Accepting | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 97 | 65 | |

| Males (%) | 71.1 | 80.0 | 0.203 |

| Age (years) | 52.4 ± 12.3 | 58.6 ± 10.6 | 0.001 |

| Marital status (% married) | 83.5 | 92.3 | 0.102 |

| Partner sleeps in separate room (%) | 21.1% | 39.0% | 0.023 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 32.1 ± 5.7 | 32.6 ± 4.8 | 0.562 |

| AHI (events/h) | 35.5 ± 23.8 | 48.8 ± 23.2 | 0.0005 |

| T90 (%) | 10.1 ± 15.9 | 21.9 ± 27.4 | 0.0026 |

| ESS (score) | 10.7 ± 4.6 | 10.0 ± 4.5 | 0.346 |

| ESS ≥ 10 (% subjects) | 63.9% | 53.9% | 0.200 |

| HTN and/or CVD (prevalence) | 52.6% | 66.2% | 0.086 |

| Tobacco Smoking (pack/year) | 30.0 ± 32.7 | 31.9 ± 27.1 | 0.773 |

| Education (years) | 12.3 ± 3.8 | 13.4 ± 3.4 | 0.092 |

| Income level | |||

| Low | 43.0% | 13.8% | 0.001 |

| Average | 35.5% | 55.2% | |

| High | 21.5% | 31.0% | |

| Receiving positive information about CPAP treatment from family or friends being treated with CPAP (% of subjects) | 19.5% | 37.5% | 0.021 |

AHI, apnea-hypopnea index; BMI, body mass index; ESS, Epworth Sleepiness Scale, T90, percent sleeping time with oxygen saturation was below 90%; HTN, hypertension; CVD, cardiovascular disease. Values are mean ± SD.

Patients' reasons for purchasing or declining CPAP are summarized in Table 3. Accepting patients reported that it solved their snoring problems and improved their daytime sleepiness (78%); they slept better with CPAP (59%) and received encouragement from partner and sleep center medical staff (53%). Only 35% reported they were convinced that CPAP treatment improved their associated morbidity and acknowledged that this was the best treatment available to them. Response of patients declining a CPAP device is summarized in Table 3: 38% reported that the side effects deterred them from CPAP treatment, 31% reported that they were interested in other treatments, and 29% reported that CPAP was too expensive and they tried and could not adapt.

Table 3.

Reasons for Accepting or Declining CPAP

| CPAP Declining % patients (n = 97) | CPAP Accepting % patients (n = 65) | |

|---|---|---|

| Response of Patients Accepting CPAP Device | ||

| It solved my snoring problems | 78% | |

| It reduced by daytime sleepiness | 78% | |

| It improved my sleep | 59% | |

| My physician and sleep laboratory team encouraged me | 53% | |

| Encouragement from partner | 53% | |

| Will improve my associated morbidity (CVD, HTN) | 35% | |

| This is the best treatment available for me | 33% | |

| Response of Patients Declining CPAP Device | ||

| I have side effects | 38% | |

| I am interested in other treatments | 31% | |

| CPAP cost is too expensive | 29% | |

| I tried and could not adapt | 29% | |

| I feel better and don't need this treatment | 13% | |

| Not encouraged by my family/friend | 11% | |

| Not encouraged by my partner | 10% | |

| Not encouraged by my physician | 6% |

CVD, cardiovascular disease; HTN, hypertension.

The univariate and multivariate ORs of determinants of CPAP acceptance are presented in Table 4. For all patients, CPAP purchase was determined by increased income level category (OR, 95% CI) (2.4; 1.3–4.3), age year +1 (1.05, 1.01–1.1), AHI (≥ 35 vs. < 35 events/hr) (3.3; 1.3–8.1), and positive experience of family and/or friends with CPAP (2.6; 1.1–5.9), area under the ROC curve of 77%. The odds of CPAP purchase for patients in the highest third of income level were 5.76 times as great as those in the lowest third of income level. HTN and/or CVD were statistically associated with age (P < 0.0001). T90 was statistically associated with AHI (P < 0.0001) and was not included in the model due to confounding effect. A similar model for CPAP purchase was received for patients living with partner (OR, 4.3, 1.4–13.3, multivariate analysis), with an area under the ROC curve of 82%. Improved sleep during the titration study and increased morning freshness afterward was an important factor: 55% of patients accepting CPAP and 24.5% of patients declining CPAP reported a positive first-ever CPAP experience (titration). This positive experience was found to increase the odds of accepting CPAP (OR 3.8, 1.7–8.5).

Table 4.

Determinants of OSAS Patients Accepting CPAP Treatment (n = 162)

| Variable | Univariate analysis (n = 162) |

Multivariate analysis (n = 162) |

Multivariate analysis (living with partner) (n = 141) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Income (low, medium, high) | 2.03 | 1.3–3.2 | 2.4 | 1.3–4.3 | 2.4 | 1.2–4.6 |

| Age (year +1) | 1.05 | 1.02–1.1 | 1.05 | 1.01–1.1 | 1.07 | 1.01–1.1 |

| BMI (+1 kg/m2) | 1.02 | 0.96–1.1 | 0.97 | 0.9–1.1 | 0.98 | 0.9–1.1 |

| AHI ( ≥ 35 vs. < 35 events/h) | 3.0 | 1.54–5.7 | 3.3 | 1.3–8.1 | 4.2 | 1.4–12.0 |

| ESS ( ≥ 10 vs. < 10 score) | 0.66 | 0.35–1.3 | 1.1 | 0.5–2.6 | 0.9 | 0.3–2.3 |

| Partner sleeps separately (yes vs. no) | 2.4 | 1.1–5.1 | Not included | 4.3 | 1.4–13.3 | |

| Family and/or friends have positive experience with CPAP (yes vs. no) | 2.5 | 1.1–5.4 | 2.6 | 1.1–5.9 | 2.9 | 1.1–7.5 |

Income, individual income level according average monthly income level in Israel; AHI, apnea-hypopnea index; BMI, body mass index; ESS, Epworth Sleepiness Scale score. Area under the ROC 77% for all 162 patients, and 82% for 141 patients living with partner.

DISCUSSION

We found that only 40% of our patients requiring CPAP actually purchased the device. Using multivariate analysis (after adjusting for age, BMI, ESS, AHI), we found that CPAP purchase was sensitive to SES level (income), AHI, family and/or friends' positive experience with CPAP, and reporting that the spouse sleeps separately. The following discussion considers these findings in the light of limitations of our study and current literature.

Study Population

The present study group represents “typical” OSAS patients.27,35,36 Our sleep center provides service to 65% of all the inhabitants in our region; therefore, these patients represent the SES and education levels of most OSAS patients in the area.27,37 According to the Israeli National Health Insurance Law all patients have “free access” (i.e., no charge) to PSG or CPAP titration studies. Physicians do not have any economic incentive to prevent or to deter patients from a PSG study or CPAP purchase.

No single factor has been consistently identified as predictive of CPAP acceptance and adherence. Therefore, understanding obstacles and critical elements associated with a patient's decision to use CPAP is crucial in promoting treatment acceptance and protocol adherence.3,9,17–21,38,39 As part of our routine, our laboratory applied protocols to help OSA patients requiring CPAP accept the device. We used a modification of a previously described approach by Popescu et al.19 and performed a second-night attendant autotitration CPAP study and provided an extensive CPAP support program. Our nighttime and daytime technologists were available to further reinforce the importance of this treatment, to troubleshoot any interface-related problems, to provide supportive information regarding OSAS morbidity and therapeutic options, and minimize technical problems (i.e., mask and humidification of the airway). Despite our support system, CPAP acceptance rates were unacceptably low15—only 40% in this study! This result is in contrast to other reports demonstrating that when receiving support protocol, CPAP acceptance is about 70%.12,13,18,19,40 Fifty-seven (35%) of our patients never started the support program and did not commence therapy after initial diagnosis or CPAP titration, supporting previous findings from Israel15 and Canada.41 CPAP acceptance was greater among patients reporting that their sleep and morning freshness improved following their first-ever CPAP use, compared with patients not reporting such experience. These findings support the need for early education and support in these patients to develop beliefs and expectations about OSAS and CPAP even before they try it.17

Despite the effectiveness of CPAP in reversing upper airway obstruction in OSAS, adherence (defined as continued > 4 h of use nightly) was found to be low. Other studies have reported 29% to 83% of patients to be nonadherent to CPAP treatment.1,13 A recent study17 explored the health belief model to determine the contribution of psychological constructs, compared to biomedical indices, in the prediction of CPAP adherence. Perceptions of risk, outcome expectancies with treatment, and functional limitations in daily life are important early predictors of initiation and continued use of CPAP. Early identification of these beliefs can increase self-efficacy and adherence to CPAP.17,42

In our study, following the 2-week CPAP trial, > 60% of CPAP–accepting patients reported that it improved their snoring, excessive daytime sleepiness, and sleep; only 35% reported that it would improve their associated morbidity (CVD, HTN). Other investigators42 reported that their CPAP-treated patients were more positive about its effect on key outcomes, i.e., 60% of the subjects linked the use of CPAP to feeling better, snoring less, being more active, improving the bed partner's sleep and their relationship. In our study, in support for these findings, more of the patients who slept separately prior to the adaptation period and were encouraged by their partners accepted CPAP.

In contrast to our study, CPAP acceptance in other countries is about 70%. Possible explanations for this gap may include the following:

First, we found that low SES predicts poor acceptance of CPAP treatment, and patients with higher SES are more likely to commence treatment.43 For each increase in income level category, the odds for CPAP acceptance increased by 140%. In the current study, SES was evaluated according to monthly income level.22–24,27 Low-income level was found to be an independent determinant for not accepting CPAP. Low SES was recognized as a potential barrier to chronic treatment due to multiple and complex interactions. Lower SES patients have a greater likelihood of exposure to SES risk behaviors, such as smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, poor diet, nonattendance to health checkups, and poor compliance with chronic treatment.44,45 In addition, copayment policy per se has been found to be a barrier to the purchase of essential drugs and medical technologies among lower SES populations.46 In our study, 29% of the patients identified cost of CPAP as a reason for not accepting CPAP. When CPAP devices were offered free,39 only a 50% acceptance level was obtained. This could be the result of offering the CPAP device to non-selected patients with mild OSAS and not using a support protocol. In a retrospective chart review study, not adjusting for income or education attainment, 42% of patients from minority-serving institutions diagnosed with OSAS failed to follow up for treatment despite having medical insurance coverage for CPAP, compared with 7% in a voluntary hospital group.28 Similar findings were reported among other urban patient populations that had an adherence rate of only 46%.47 It is possible that despite having medical insurance (CPAP is free of out-of-pocket payment), patients with low SES are less knowledgeable about their disease and treatment options. Therefore, they are less compliant with CPAP in contrast to high SES patients.

Second, OSAS severity (AHI ≥ 35 vs. < 35 events/h) in our study was found to be an independent predictor that increased the odds for CPAP acceptance, after adjusting for ESS score > 10. Other investigators have demonstrated that AHI has a weak relationship with CPAP adherence,1,10,48 mainly in symptomatic patients. It is possible that primary care physician recommendations to commence CPAP are based on AHI. However, Brin et al.15 found CPAP acceptance of 35% after analyzing the subgroup of the most severe and symptomatic patients (AHI ≥ 30 or AHI < 30/h and ESS > 10). It is possible that policy criteria only according to AHI may affect physician recommendations to commence CPAP. However, in the current study, the primary care physician impact on patient decision to accept CPAP was probably minimal, since only 16% of our patients reported receiving some information from their physicians regarding OSAS therapeutic options. This finding needs to be further explored.

Third, support (mainly by the partner) had positive influence on CPAP adherence.48,49 Patients' main reasons for seeking attention were symptoms that affect the partner rather than themselves.3,15,18 These findings were consistent with our finding that social support from family and/or friends' positive experience with CPAP was an independent predictor to increase the odds for CPAP acceptance (OR = 2.6 and 2.9 for the whole group and patients living with partners, respectively). Moreover, the partner's decision to sleep in a separate room increased the odds (OR = 4.3) of a patient's acceptance of CPAP. This supports the possibility that CPAP treatment will improve the personal relationship between partners50 and is needed to preserve marital satisfaction, although it did not predict objective CPAP use.51 This study further supports the need to recruit the partner, family members, or friends in order to improve CPAP acceptance.

Fourth, we found that CPAP acceptance was low among young adults. Factors affecting CPAP treatment at < 40 years of age are probably multifactorial. According to accepted guidelines, CPAP is recommended31 therapy to patients with AHI ≥ 30 events per hour of sleep, and patients with an AHI of 5-30 events per hour of sleep accompanied by ESS score ≥ 10 and/or documented CVD and or HTN. These recommendations were based on studies about OSAS comorbidities using cross-sectional population-based studies (based on Sleep Heart Health Study protocol), starting from the age of 40 years.52–54 The prevalence of HTN and CVD is low among young adults.35 Therefore, physicians as well as patients are less likely to commence CPAP in young adults when no symptoms exist or (in case of AHI of 5-30/h) accompanied only by excessive daytime sleepiness (ESS score ≥ 10). It is possible that young adults with OSAS will seek other therapeutic options before accepting CPAP because clinicians may deflect attention and awareness from recommending CPAP treatment at younger ages.55,56

Finally, in our study, > 80% of OSAS patients reported that they did not receive any information from their primary care physician regarding the diagnostic and therapeutic processes in the sleep center. This may suggest that OSAS diagnosis and therapeutic processes are poorly recognized by primary care physicians.55 Usually, medical attention by sleep specialists is sought primarily by patients and their partners as a result of self-diagnosis and not because their condition has been detected by their primary care physician.3,42,57 When primary care physicians and bed partners were strongly supportive, patients were more likely to commence CPAP therapy.21,42 To the best of our knowledge, no professional society has officially addressed the issues of best practice on the initiation of CPAP therapy. We recommend, in addition to patient educational programs, development of tailored programs, according to patient's risk factors, to increase the level of awareness of OSAS and its treatment among physicians.55

Summary

In addition to the already known determinants, low-SES was found to be an independent risk factor discouraging CPAP acceptance. For each increase in income level category, the odds of CPAP acceptance increased by 140%. Therefore SES should be addressed in terms of risk factors in the process of patient educational programs to improve CPAP acceptance and adherence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a Competitive Grant from the Israel Institute for Health Policy and Health Services Research, award no. A/147/2003.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Positive Airway Pressure Task Force; Standards of Practice Committee; American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Gay P, Weaver T, Loube D, Iber C. Evaluation of positive airway pressure treatment for sleep related breathing disorders in adults. Sleep. 2006;29:381–401. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weaver TE, Maislin G, Dinges DF, et al. Relationship between hours of CPAP use and achieving normal levels of sleepiness and daily functioning. Sleep. 2007;30:711–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.6.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McArdle N, Kingshott R, Engleman HM, Mackay TW, Douglas NJ. Partners of patients with sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome: effect of CPAP treatment on sleep quality and quality of life. Thorax. 2001;56:513–8. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.7.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jenkinson C, Davies RJO, Mullins R, et al. Comparison of therapeutic and subtherapeutic nasal continuous positive airway pressure for obstructive sleep apnoea: a randomised prospective parallel trial. Lancet. 1999;353:2100–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10532-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drager LF, Bortolotto LA, Figueiredo AC, Krieger EM, Lorenzi GF. Effects of continuous positive airway pressure on early signs of atherosclerosis in obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:706–12. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-500OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Vicente E, Agusti AG. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: an observational study. Lancet. 2005;365:1046–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71141-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collard P, Pieters T, Aubert G, Delguste P, Rodenstein A. Compliance with nasal CPAP in obstructive sleep apnea patients. Sleep Med Rev. 1997;1:33–44. doi: 10.1016/s1087-0792(97)90004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weaver TE, Kribbs NB, Pack AI, et al. Night to night variability in CPAP use over the first three months of treatment. Sleep. 1997;20:278–83. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.4.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krieger J, Kurtz D, Petiau C, Sforza E, Trautmann D. Long-term compliance with CPAP therapy in obstructive sleep apnea patients and in snorers. Sleep. 1996;19:S136–43. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.suppl_9.s136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Budhiraja R, Parthasarathy S, Drake CL, et al. Early CPAP use identifies subsequent adherence to CPAP therapy. Sleep. 2007;30:320–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scharf SM, Seiden L, DeMore J, Carter-Pokras O. Racial differences in clinical presentation of patients with sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep Breath. 2004;8:173–83. doi: 10.1007/s11325-004-0173-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sin DD, Mayers I, Man GC, Pawluk L. Long-term compliance rates to continuous positive airway pressure in obstructive sleep apnea: a population-based study. Chest. 2002;121:430–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.2.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hui DS, Choy DKL, Li TST, et al. Determinants of continuous positive airway pressure compliance in a group of Chinese patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2001;120:170–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.1.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whittle AT, Douglas NJ. Does the physiological success of CPAP titration predict clinical success? J Sleep Res. 2000;9:201–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brin Y, Reuveni H, Greenberg-Dotan S, Tal A, Tarasiuk A. CPAP purchasing is reduced due to combined effect of patient characteristics and health care policy. Isr Med Assoc J. 2005;7:13–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waldhorn RE, Herrick TW, Nguyen MC, O'Donnell AE, Sodero J, Potolicchio SJ. Long term compliance with nasal continuous positive airway pressure therapy of obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 1990;97:33–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.97.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olsen S, Smith S, Oei T, Douglas J. Health belief model predicts adherence to CPAP before experience with CPAP. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:710–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00127507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoy CJ, Vennelle M, Kingshott RN, Engleman HM, Douglas NJ. Can intensive support improve continuous positive airway pressure use in patients with the sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1096–100. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.4.9808008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Popescu G, Latham M, Allgar V, Elliott MW. Continuous positive airway pressure for sleep apnea/hypopnoea syndrome: usefulness of a 2-week trial to identify factors associated with long term use. Thorax. 2001;56:727–33. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.9.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hui DS, Chan JKW, Choy DKL, et al. Effects of augmented continuous positive airway pressure education and support on compliance and outcome in a Chinese population. Chest. 2000;117:1410–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.5.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weaver TE, Grunstein RR. Adherence to continuous positive airway pressure therapy: the challenge to effective treatment. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:173–8. doi: 10.1513/pats.200708-119MG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fukuda Y, Nakamura K, Takano T. Accumulation of health risk behaviours is associated with lower socioeconomic status and women's urban residence: a multilevel analysis in Japan. BMC Public Health. 2005;5:53. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anand SS, Yusuf S, Jacobs R, et al. Risk factors, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular disease among aboriginal people in Canada: the Study of Health Assessment and Risk Evaluation in Aboriginal Peoples (SHARE-AP) Lancet. 2001;358:1147–53. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06255-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mackenbach JP, Stirbu I, Roskam AJ, et al. European Union Working Group on Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health. Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2468–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0707519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young T, Peppard PE, Gottlieb DJ. Epidemiology of obstructive sleep apnea: a population health perspective. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:1217–39. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2109080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shah BR, Hux JE, Zinman B. Increasing rates of ischemic heart disease in the native population of Ontario, Canada. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1862–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.12.1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tarasiuk A, Greenberg-Dotan S, Simon T, Tal A, Oksenberg A, Reuveni H. Low socioeconomic status is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease among adult OSAS patients requiring treatment. Chest. 2006;130:766–73. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.3.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenberg H, Fleischman J, Gouda HE, et al. Disparities in obstructive sleep apnea and its management between a minority-serving institution and a voluntary hospital. Sleep Breath. 2004;8:185–92. doi: 10.1007/s11325-004-0185-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Safeer RS, Cooke CE, Keenan J. The impact of health literacy on cardiovascular disease. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2006;2:457–64. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.2006.2.4.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mauro M, Taylor V, Wharton S, Sharma AM. Barriers to obesity treatment. Eur J Intern Med. 2008;19:173–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kushida CA, Littner MR, Hirshkowitz M, et al. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Practice parameters for the use of continuous and bilevel positive airway pressure devices to treat adult patients with sleep-related breathing disorders. Sleep. 2006;29:375–80. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540–54. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rotem AY, Sperber AD, Krugliak P, Freidman B, Tal A, Tarasiuk A. Polysomnography and actigraphy evidence of sleep fragmentation in irritable bowel syndrome. Sleep. 2003;26:746–52. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.6.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kump K, Whalen C, Tishler PV, et al. Assessment of the validity and utility of a sleep-symptom questionnaire. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:735–41. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.3.8087345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reuveni H, Greenberg-Dotan S, Simon-Tuval T, Oksenberg A, Tarasiuk A. Young adult males with OSA consume high health care resources due to nonspecific co-morbidity. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:273–9. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00097907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tarasiuk A, Greenberg-Dotan S, Simon T, Tal A, Oksenberg A, Reuveni H. Elderly with obstructive sleep apnea consume high health care resources due to elevated cardiovascular morbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:247–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tarasiuk A, Greenberg-Dotan S, Brin YS, Simon T, Tal A, Reuveni H. Determinants affecting health care utilization in OSAS patients. Chest. 2005;128:1310–4. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olsen S, Smith S, Oei TP. Adherence to continuous positive airway pressure therapy in obstructive sleep apnoea sufferers: A theoretical approach to treatment adherence and intervention. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008 Jul 18; doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.07.004. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rauscher H, Popp W, Wanke T, Zwick H. Acceptance of CPAP therapy for sleep apnea. Chest. 1991;100:1019–23. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.4.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Engleman HM, Wild MR. Improving CPAP use by patients with the sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Sleep Med Rev. 2003;7:81–99. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolkove N, Baltzan M, Kamel H, Dabrusin R, Palayew M. Long-term compliance with continuous positive airway pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea Can Respir J. 2008;15:365–9. doi: 10.1155/2008/534372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weaver TE, Maislin G, Dinges DF, et al. Self-efficacy in sleep apnea: instrument development and patient perceptions of obstructive sleep apnea risk, treatment benefit, and volition to use continuous positive airway pressure. Sleep. 2003;26:727–32. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.6.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Becker MH, Maiman LA. Sociobehavioral determinants of compliance with health and medical care recommendations. Med Care. 1975;13:10–24. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197501000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams LK, Joseph CL, Peterson EL, et al. Race-ethnicity, crime, and other factors associated with adherence to inhaled corticosteroids. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:168–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kripke DF, Ancoli-Israel S, Klauber MR, Wingard DL, Mason WJ, Mullaney DJ. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in ages 40-64 years: a population-based survey. Sleep. 1997;20:65–76. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reuveni H, Sheizaf B, Elhayany A, et al. The effect of drug co-payment policy on the purchase of prescription drugs for children with infections in the community. Health Policy. 2002;62:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(02)00011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kribbs NB, Pack AI, Kline LR, et al. Objective measurement of patterns of nasal CPAP use by patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147:4887–95. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.4.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Joo MJ, Herdegen JJ. Sleep apnea in an urban public hospital: assessment of severity and treatment adherence. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:285–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lewis KE, Seale L, Bartle IE, Watkins AJ, Ebden P. Early predictors of CPAP use for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2004;27:134–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kiely J, McNicholas W. Bed partners' assessment of nasal continuous positive airway pressure therapy in obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 1997;111:1261–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.5.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McFadyen TA, Espie CA, McArdle N, Douglas NJ, Engleman HM. Controlled, prospective trial of psychosocial function before and after continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Eur Respir J. 2001;18:996–1002. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00209301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1378–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005113421901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shahar E, Whitney CW, Redline S, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease: cross-sectional results of the Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:19–25. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.2001008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nieto FJ, Young TB, Lind BK, et al. Association of sleep-disordered breathing, sleep apnea, and hypertension in a large community-based study. Sleep Heart Health Study. JAMA. 2000;283:1829–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.14.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reuveni H, Tarasiuk A, Wainstock T, Ziv A, Elchayani A, Tal A. Awareness level to obstructive sleep apnea syndrome during routine unstructured interviews of a standardized patient by primary care physicians. Sleep. 2004;27:1518–25. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.8.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lavie P. Sleep medicine – Time for a change. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2:207–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Young T, Evans L, Finn L, Palta M. Estimation of the clinically diagnosed proportion of sleep apnea syndrome in middle-aged men and women. Sleep. 1997;20:705–6. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.9.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]