Abstract

One selection pressure shaping sequence evolution is the requirement that a protein fold with sufficient stability to perform its biological functions. We present a conceptual framework that explains how this requirement causes the probability that a particular amino acid mutation is fixed during evolution to depend on its effect on protein stability. We mathematically formalize this framework to develop a Bayesian approach for inferring the stability effects of individual mutations from homologous protein sequences of known phylogeny. This approach is able to predict published experimentally measured mutational stability effects (ΔΔG values) with an accuracy that exceeds both a state-of-the-art physicochemical modeling program and the sequence-based consensus approach. As a further test, we use our phylogenetic inference approach to predict stabilizing mutations to influenza hemagglutinin. We introduce these mutations into a temperature-sensitive influenza virus with a defect in its hemagglutinin gene and experimentally demonstrate that some of the mutations allow the virus to grow at higher temperatures. Our work therefore describes a powerful new approach for predicting stabilizing mutations that can be successfully applied even to large, complex proteins such as hemagglutinin. This approach also makes a mathematical link between phylogenetics and experimentally measurable protein properties, potentially paving the way for more accurate analyses of molecular evolution.

Author Summary

Mutating a protein frequently causes a change in its stability. As scientists, we often care about these changes because we would like to engineer a protein's stability or understand how its stability is impacted by a naturally occurring mutation. Evolution also cares about mutational stability changes, because a basic evolutionary requirement is that proteins remain sufficiently stable to perform their biological functions. Our work is based on the idea that it should be possible to use the fact that evolution selects for stability to infer from related proteins the effects of specific mutations. We show that we can indeed use protein evolutionary histories to computationally predict previously measured mutational stability changes more accurately than methods based on either of the two main existing strategies. We then test whether we can predict mutations that increase the stability of hemagglutinin, an influenza protein whose rapid evolution is partly responsible for the ability of this virus to cause yearly epidemics. We experimentally create viruses carrying predicted stabilizing mutations and find that several do in fact improve the virus's ability to grow at higher temperatures. Our computational approach may therefore be of use in understanding the evolution of this medically important virus.

Introduction

Knowledge of the impact of individual amino acid mutations on a protein's stability is valuable both for understanding the protein's natural evolution and for altering its properties for engineering purposes. Experimentally measuring the effects of mutations on protein stability is a laborious process, so a variety of methods have been devised to predict these effects computationally. Most existing methods rely on some type of physicochemical modeling of the mutation in the context of the protein's three-dimensional structure, often augmented by information gleaned from statistical analyses of protein sequences and structures. These types of methods are moderately accurate at predicting the effects of mutations on the stabilities of small soluble proteins [1]–[8]. There is little or no published data evaluating their performance on the larger and more complex proteins that are frequently of greatest biological interest, although it might be expected to be worse given the greater difficulty of modeling larger structures.

An alternative approach to predicting the effects of mutations on protein stability utilizes the information contained in alignments of evolutionarily related sequences. This approach, which was originally introduced by Steipe and coworkers [9], envisions an alignment of related sequences as representing a random sample of all possible sequences that fold into a given protein structure. Based on a loose analogy with statistical physics, the frequency of a given residue in the sequence alignment is assumed to be an exponential function of its contribution to the protein's stability (just as the Boltzmann factor in statistical physics relates the probability of a microscopic state to the exponential of its energy). This is often called the “consensus” approach, since it always predicts that the most stabilizing mutation will be to the most commonly occurring (consensus) residue. The consensus approach has proven to be surprisingly successful, with a wide range of studies supporting the basic notion that stabilizing residues tend to appear more frequently in sequence alignments of homologous proteins [10]–[17].

But although it is often effective, the consensus approach suffers from an obvious conceptual flaw: alignments of natural proteins do not represent random samples of all possible sequences encoding a given structure, but instead are highly biased by evolutionary relationships. A particular residue might occur frequently because it has arisen repeatedly through independent amino acid substitutions, or it might occur frequently simply because it occurred in the common ancestor of many related sequences in the alignment. The sequence evolution of even distantly related protein homologs is non-ergodic (as evidenced by the fact that sequence divergence continues to increase with elapsed evolutionary time), and so this problem will plague all natural sequence alignments. Therefore, it would clearly be desirable to extract information about protein stability from sequence alignments using a method that accounts for evolutionary relationships.

In fact, there are already highly developed mathematical descriptions of the divergence of evolving protein sequences. The widely used likelihood-based methods for inferring protein phylogenies employ explicit models of amino acid substitution to assess the likelihood of phylogenetic trees [18]. However, these methods make no effort to determine how selection for protein stability might manifest itself in the ultimate frequencies of amino acids in an alignment of evolved sequences. Instead, in their simplest form, these phylogenetic methods simply assume that there is a universal “average” tendency for one particular amino acid to be substituted with another (these “average” substitution tendencies are typically given by PAM, BLOSUM, or JTT matrices). More advanced phylogenetic methods sometimes allow for different “average” substitution tendencies for different classes of protein residues (such as surface versus core residues, or residues involved in different types of secondary structures) [19]–[24]. Still other methods use simulations or other structure-based methods to derive site-specific substitution matrices for different positions in a protein [25]–[28]. However, none of these methods relate the substitution probabilities to the effects of mutations on experimentally measurable properties such as protein stability, nor do they provide a method for predicting the effects of the mutations from the protein phylogenies.

Here we present an approach for using protein phylogenies to infer the effects of amino acid mutations on protein stability. We begin by describing a conceptual framework that quantitatively links a mutation's effect on protein stability to the probability that it will be fixed by evolution. We then show how this framework can be used to calculate the likelihood of specific phylogenetic relationships given the stability effects of all possible amino acid mutations to a protein. Our actual goal is to do the reverse, and infer the stability effects given a known protein phylogeny. To robustly accomplish this, we use Bayesian inference with informative priors derived from an established physicochemical modeling program. We compare the inferred stability effects to published experimental values for several proteins, and show that our method outperforms both the physicochemical modeling program and the consensus approach. Finally, we use our method to predict mutations that increase the temperature-stability of influenza hemagglutinin, a complex multimeric membrane-bound glycoprotein for which (to our knowledge) stabilizing mutations have never previously been successfully predicted by any approach. We introduce the predicted stabilizing mutations into hemagglutinin, and experimentally demonstrate that several of them increase the temperature-stability of the protein in the context of live influenza virus. Overall, our work presents a unified framework for incorporating protein stability into phylogenetic analyses, as well as demonstrating a powerful new approach for predicting stabilizing mutations.

Results

A framework relating the biophysical impact of amino acid mutations to the frequency with which they are fixed during neutral evolution

We begin by introducing a conceptual framework that relates the probability that a specific amino acid mutation will be selectively neutral (and so have an opportunity to spread by genetic drift) to its effect on protein stability. Because this conceptual framework forms the starting point for subsequent mathematical inference, it is necessarily highly simplified. It is based on several assumptions which, although motivated by biophysical considerations, are subject to many exceptions. Below we outline these assumptions, and mention some of the exceptions. We hope the reader will become convinced that this conceptual framework strikes a reasonable balance between being realistic and mathematically tractable. The conceptual framework that we describe has previously been successfully employed in simulations [29],[30], and later in theoretical treatments [31],[32], of protein evolution.

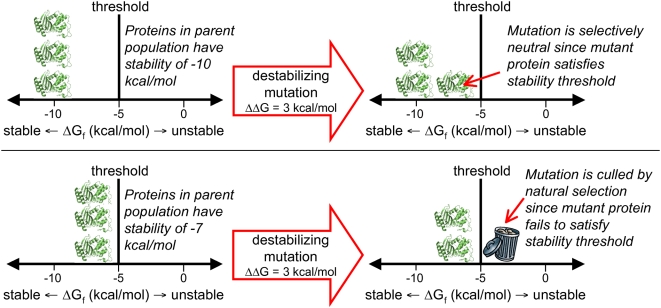

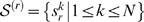

We assume that evolution selects only for a protein's biochemical function, and is indifferent to its precise stability provided that the protein folds with sufficient stability to perform its function. This assumption is imperfect, since some proteins are natively unfolded [33], only kinetically stable [34], or specifically selected for marginal stability in order to aid in regulation [35]. In addition, mildly destabilized proteins might retain partial function while being subject to weak negative selection. This assumption nonetheless captures the overriding idea that most proteins have evolved to fold to stable structures in order to perform biochemical functions that are the actual dominant targets of natural selection. With this assumption, proteins can be viewed as having to satisfy a minimal stability threshold in order to avoid being culled by natural selection (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. A stability threshold model of protein evolution.

Proteins are assumed to be functional if and only if they are more stable

than some minimal threshold (in the figure,  , which is a typical value for natural proteins [53]; note that more stable proteins have more

negative

, which is a typical value for natural proteins [53]; note that more stable proteins have more

negative  values). When a particular destabilizing mutation (

values). When a particular destabilizing mutation ( ) occurs, the evolutionary result will depend on the

stability of the proteins in the parent population. When the parent

proteins are sufficiently stable (top panel), the mutant protein still

satisfies the threshold, and so the mutation has the opportunity to

spread by neutral genetic drift. But when the parent proteins are not

sufficiently stable (bottom panel), the mutant protein fails to stably

fold, and is eliminated by natural selection. Therefore, the probability

that a mutation that induces a stability change of

) occurs, the evolutionary result will depend on the

stability of the proteins in the parent population. When the parent

proteins are sufficiently stable (top panel), the mutant protein still

satisfies the threshold, and so the mutation has the opportunity to

spread by neutral genetic drift. But when the parent proteins are not

sufficiently stable (bottom panel), the mutant protein fails to stably

fold, and is eliminated by natural selection. Therefore, the probability

that a mutation that induces a stability change of  will have an opportunity to spread by neutral genetic

drift is simply the probability that the parent protein has a stability

will have an opportunity to spread by neutral genetic

drift is simply the probability that the parent protein has a stability  .

.

We further assume that all protein mutants that satisfy the stability threshold are equally functional, while all mutants that fail to satisfy the threshold are nonfunctional. This assumption has the mathematically desirable property that it neatly divides all mutants into one of two categories (sufficiently stable or nonfunctional). Of course, we recognize that this assumption is not strictly true, since one could fill many pages documenting mutations that are deleterious despite preserving stability. For example, mutations can specifically interfere with a protein's function (such as altering an enzyme's activity)—but experiments have shown that such mutations are rare compared to the much larger number that affect stability [36]–[39]. Mutations can also be deleterious if they increase a protein's propensity to aggregate [40]–[43] or interfere with its folding [44] or unfolding [16],[45] kinetics—but quantifying a mutation's impact on stability provides a partial proxy for these effects since aggregation propensity [40], folding rate [46]–[49], and kinetic stability [16] are correlated with stability. Mutations can also have other deleterious effects, such as altering mRNA stability [50], codon usage [51], or the accuracy and efficiency of translation [43],[51],[52]. We mention these myriad exceptions to explicitly acknowledge their existence. Nonetheless, from here forward we will use the concept of stability threshold selection to develop a mathematical relationship between protein stability and evolution.

Figure 1 illustrates the

stability threshold view of evolution that we have just described. In this

figure, a protein's stability is quantified by its free energy of

folding (its  ), and the effects of mutations by the change they induce in

the free energy of folding (their

), and the effects of mutations by the change they induce in

the free energy of folding (their  values) [53]. For proteins that do not fold reversibly,

some alternative experimental measure of stability (such as resistance to

thermal denaturation [54] or proteolysis [55]) is clearly required,

but the concept remains the same. The key implication of Figure 1 is that the evolutionary impact of a

mutation can depend on the stability of the parent protein into which it is

introduced, with a moderately destabilizing mutation being neutral in the

context of a stable parent but lethal to a marginally stable parent. That

mutational tolerance is indeed enhanced by extra stability in this fashion has

been experimentally verified for several proteins [56]–[58]. This idea provides a basis for forsaking the

traditional approach of using pre-specificied “average”

amino acid substitution matrices, and instead adopting the view that the

frequency of a particular substitution tells us something about its impact on

protein stability. Much of the rest of this paper deals with the mathematical

mechanics of how to use the substitution frequencies implied by a set of protein

homologs to infer the effects of individual mutations on stability.

values) [53]. For proteins that do not fold reversibly,

some alternative experimental measure of stability (such as resistance to

thermal denaturation [54] or proteolysis [55]) is clearly required,

but the concept remains the same. The key implication of Figure 1 is that the evolutionary impact of a

mutation can depend on the stability of the parent protein into which it is

introduced, with a moderately destabilizing mutation being neutral in the

context of a stable parent but lethal to a marginally stable parent. That

mutational tolerance is indeed enhanced by extra stability in this fashion has

been experimentally verified for several proteins [56]–[58]. This idea provides a basis for forsaking the

traditional approach of using pre-specificied “average”

amino acid substitution matrices, and instead adopting the view that the

frequency of a particular substitution tells us something about its impact on

protein stability. Much of the rest of this paper deals with the mathematical

mechanics of how to use the substitution frequencies implied by a set of protein

homologs to infer the effects of individual mutations on stability.

Sequence evolution without any selection

To introduce the mathematical analysis, begin by considering protein sequence

evolution in the absence of any selection on amino acid composition. Even in the

absence of selection, some amino acid substitutions are more likely than others

due to the structure of the genetic code and unequal frequencies of different

types of nucleotide mutations. In order to express the probabilities of various

types of mutations only in terms of amino acid identities, assume that the

distribution of codons encoding each amino acid is always at equilibrium. For

example, assume that all glycines at all times have the same probability of

being encoded by the GGG codon. With this assumption, the current state of a

residue can be described by its amino acid identity rather than its codon

identity (see [59] for an evolutionary model that operates at

the codon-level). Given that a particular position is currently amino acid  , let

, let  denote the probability that a single nucleotide mutation to

the codon at this position changes the identity to amino acid

denote the probability that a single nucleotide mutation to

the codon at this position changes the identity to amino acid  . Nonsense mutations (to stop codons) are assumed to be

immediately eliminated by selection, and so leave the codon unchanged. All other

mutations are assumed to be neutral. Therefore, all nonsense and synonymous

mutations contribute to

. Nonsense mutations (to stop codons) are assumed to be

immediately eliminated by selection, and so leave the codon unchanged. All other

mutations are assumed to be neutral. Therefore, all nonsense and synonymous

mutations contribute to  , and all nonsynonymous mutations contribute to

, and all nonsynonymous mutations contribute to  with

with  . Denote the set of all

20×20 = 400 values of

. Denote the set of all

20×20 = 400 values of  as

as  . Note that

. Note that  , since each mutation either leads to a new amino acid (

, since each mutation either leads to a new amino acid ( ) or leaves the amino acid unchanged (

) or leaves the amino acid unchanged ( ).

).

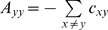

Let  be the 20×20 matrix with off-diagonal elements

be the 20×20 matrix with off-diagonal elements  and diagonal elements

and diagonal elements  . Let

. Let  be the rate at which an individual codon experiences a

nucleotide mutation, so that each codon experiences an average of

be the rate at which an individual codon experiences a

nucleotide mutation, so that each codon experiences an average of  mutations after an elapsed time of

mutations after an elapsed time of  . It is assumed that all codons in the protein experience the

same mutation rate

. It is assumed that all codons in the protein experience the

same mutation rate  . As will be seen below, the full model still allows variation

in the rate at which substitutions accumulate at different residues, but this

variation is caused by selection for stability rather than by differences in the

underlying rate of mutation. Without selection for stability, the probability

that a residue that is initially

. As will be seen below, the full model still allows variation

in the rate at which substitutions accumulate at different residues, but this

variation is caused by selection for stability rather than by differences in the

underlying rate of mutation. Without selection for stability, the probability

that a residue that is initially  will be

will be  after an elapsed time of

after an elapsed time of  is given by the element

is given by the element  of the matrix

of the matrix  [18]. After a sufficiently long period of time (

[18]. After a sufficiently long period of time ( ), the probability to find some specific amino acid

), the probability to find some specific amino acid  is the same across all positions of the protein, and is given

by element

is the same across all positions of the protein, and is given

by element  of the right eigenvector of

of the right eigenvector of  corresponding to the unique zero eigenvalue (the uniqueness of

this eigenvector is guaranteed by the Perron-Frobenius theorems, since

corresponding to the unique zero eigenvalue (the uniqueness of

this eigenvector is guaranteed by the Perron-Frobenius theorems, since  plus the identity matrix will be an irreducible and acyclic

stochastic matrix). Of course, real proteins tend to prefer some amino acids at

certain positions, such as hydrophobic residues in the core. The substitution

model that has just been described fails to account for these preferences. The

next section explains how this problem can be remedied by incorporating

selection for stability.

plus the identity matrix will be an irreducible and acyclic

stochastic matrix). Of course, real proteins tend to prefer some amino acids at

certain positions, such as hydrophobic residues in the core. The substitution

model that has just been described fails to account for these preferences. The

next section explains how this problem can be remedied by incorporating

selection for stability.

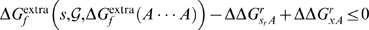

Substitution probabilities in the presence of selection for stability

The situation described in the previous section changes fundamentally in the

presence of selection for protein stability, since mutations will be eliminated

if they destabilize a protein beyond the threshold. Specifically, let  be the stability (free energy of folding [53]) of the parent

protein and let

be the stability (free energy of folding [53]) of the parent

protein and let  be the minimal stability required by the threshold, so that

the protein has extra stability

be the minimal stability required by the threshold, so that

the protein has extra stability  . Only those mutations that leave

. Only those mutations that leave  have a chance to be fixed by evolution (more negative

have a chance to be fixed by evolution (more negative  values indicate more stable proteins). Let

values indicate more stable proteins). Let  be the sequence of a protein of the length

be the sequence of a protein of the length  , and let

, and let  be the extra stability of this protein. Mutating residue

be the extra stability of this protein. Mutating residue  of the protein from its current identity

of the protein from its current identity  to some new amino acid

to some new amino acid  induces a stability change of

induces a stability change of  . Under the stability threshold model, this mutation can become

fixed if and only if

. Under the stability threshold model, this mutation can become

fixed if and only if  .

.

This description, in which  for mutating residue

for mutating residue  is a function of the parent sequence

is a function of the parent sequence  as well as the residue identities

as well as the residue identities  , is completely general. However, it is not useful. The reason

for this lack of utility is that there are

, is completely general. However, it is not useful. The reason

for this lack of utility is that there are  different possible protein sequences

different possible protein sequences  , since each of the

, since each of the  positions in the protein can take on any of the 20 amino

acids. Since

positions in the protein can take on any of the 20 amino

acids. Since  for a typical protein is several hundred residues, the number

of different

for a typical protein is several hundred residues, the number

of different  values exceeds the number of atoms in the Universe. This many

values cannot reasonably be specified a priori or inferred from

available sequence data.

values exceeds the number of atoms in the Universe. This many

values cannot reasonably be specified a priori or inferred from

available sequence data.

However, the situation can be made more tractable by assuming that  is independent of

is independent of  , and so is equal to the same value of

, and so is equal to the same value of  for all sequences. This assumption is equivalent to saying

that the

for all sequences. This assumption is equivalent to saying

that the  values for mutations to different residues are independent and

additive, which implies that the

values for mutations to different residues are independent and

additive, which implies that the  value of a mutation does not depend on the sequence background

in which it appears. This assumption is clearly not completely true, since

protein stability depends on cooperative interactions among many residues.

However, empirically it appears that the assumption of independent and additive

value of a mutation does not depend on the sequence background

in which it appears. This assumption is clearly not completely true, since

protein stability depends on cooperative interactions among many residues.

However, empirically it appears that the assumption of independent and additive  values is nonetheless actually rather good. For example, a

number of biochemical studies have indicated that the

values is nonetheless actually rather good. For example, a

number of biochemical studies have indicated that the  values for a modest number of amino acid mutations are

frequently independent and additive [60]–[65].

Of particular relevance is a study by Fersht and Serrano [65] of the amino acid

substitutions separating the homologous proteins binase and barnase, which have

85% sequence identity. They found that combinations of these

substitutions had additive effects on stability, indicating that the

values for a modest number of amino acid mutations are

frequently independent and additive [60]–[65].

Of particular relevance is a study by Fersht and Serrano [65] of the amino acid

substitutions separating the homologous proteins binase and barnase, which have

85% sequence identity. They found that combinations of these

substitutions had additive effects on stability, indicating that the  values are very nearly constant among the sequences that

occurred during the evolutionary divergence of these two proteins. This high

degree of independence and additivity of experimentally measured

values are very nearly constant among the sequences that

occurred during the evolutionary divergence of these two proteins. This high

degree of independence and additivity of experimentally measured  values may be due to the fact that pairwise amino-acid

interaction potentials can be accurately approximated by independent sites [28],[66]. Regardless of the underlying reasons, at

least at modest levels of sequence divergence, there is experimental evidence

that the approximation of constant

values may be due to the fact that pairwise amino-acid

interaction potentials can be accurately approximated by independent sites [28],[66]. Regardless of the underlying reasons, at

least at modest levels of sequence divergence, there is experimental evidence

that the approximation of constant  values is quite accurate.

values is quite accurate.

Assuming that  is independent of the particular sequence background greatly

reduces the number of these values that need to be determined. To count the

number of unique

is independent of the particular sequence background greatly

reduces the number of these values that need to be determined. To count the

number of unique  values, note that any closed loop in the space of protein

sequences yields no net change in stability. That is,

values, note that any closed loop in the space of protein

sequences yields no net change in stability. That is,  (since there is no stability change when there is no

mutation),

(since there is no stability change when there is no

mutation),  (since mutating

(since mutating  and then back to

and then back to  does not change the sequence), and

does not change the sequence), and  (since this combination of mutations leaves the sequence

unchanged). Therefore, all

(since this combination of mutations leaves the sequence

unchanged). Therefore, all  values can be determined with reference to mutating an

arbitrarily chosen amino acid, which is here taken to be alanine (A). There are

values can be determined with reference to mutating an

arbitrarily chosen amino acid, which is here taken to be alanine (A). There are  different

different  values, since each of the

values, since each of the  residues can be mutated to any of the 19 non-alanine amino

acids. The specification of all

residues can be mutated to any of the 19 non-alanine amino

acids. The specification of all  values allows any

values allows any  value to be calculated as

value to be calculated as

| (1) |

All  values are therefore uniquely determined by the set

values are therefore uniquely determined by the set of

of  values. This paper will show that the elements of

values. This paper will show that the elements of  can be reasonably inferred using informative Bayesian priors.

can be reasonably inferred using informative Bayesian priors.

First, assume that  is known and consider the problem of using this knowledge to

determine whether selection will tolerate a particular mutation to some

specified protein sequence. Let

is known and consider the problem of using this knowledge to

determine whether selection will tolerate a particular mutation to some

specified protein sequence. Let  be the extra stability of a sequence composed entirely of the

alanine reference amino acid. The extra stability of any protein sequence

be the extra stability of a sequence composed entirely of the

alanine reference amino acid. The extra stability of any protein sequence  can be calculated from

can be calculated from  and

and  as

as

| (2) |

where  is the amino acid at residue

is the amino acid at residue  of sequence

of sequence  . Under the stability threshold model, mutating residue

. Under the stability threshold model, mutating residue  of the folded protein with sequence

of the folded protein with sequence  is acceptable to selection if and only if

is acceptable to selection if and only if  . It may be possible to use this formulation to develop a

mathematically tractable description of protein evolution. However, the

situation is complicated by the fact that the acceptability of a mutation

depends on the protein sequence

. It may be possible to use this formulation to develop a

mathematically tractable description of protein evolution. However, the

situation is complicated by the fact that the acceptability of a mutation

depends on the protein sequence  . Therefore, describing protein evolution using Equation 2

requires estimating the stability of each sequence that occurs along the

phylogenetic tree, and averaging over all possible sequence paths. This paper

circumvents this difficult task by making the additional (mean-field)

approximation that the acceptability of a specific mutation depends on the

average distribution of

. Therefore, describing protein evolution using Equation 2

requires estimating the stability of each sequence that occurs along the

phylogenetic tree, and averaging over all possible sequence paths. This paper

circumvents this difficult task by making the additional (mean-field)

approximation that the acceptability of a specific mutation depends on the

average distribution of  , rather than on the exact stability of the protein sequence in

which the mutation occurs. In other words, we take the probability that mutating

residue

, rather than on the exact stability of the protein sequence in

which the mutation occurs. In other words, we take the probability that mutating

residue  from

from  is neutral to be equal to the probability that

is neutral to be equal to the probability that  . This mean-field approximation eliminates all coupling between

substitutions at different sites in the protein.

. This mean-field approximation eliminates all coupling between

substitutions at different sites in the protein.

With this mean-field approximation, the issue becomes determining the average

distribution of stabilities in an evolving population of proteins. This problem

has been treated previously by simulations [29] and mathematically

through matrix [31] and diffusion [32] equation

approaches. The average distribution of stabilities turns out to depend on the

degree of polymorphism in the population, with highly polymorphic populations

(those with the product of the population size  and the per sequence per generation mutation rate

and the per sequence per generation mutation rate  much greater than one) evolving to greater average stabilities

than populations that are mostly monomorphic (those with

much greater than one) evolving to greater average stabilities

than populations that are mostly monomorphic (those with  ) [31],[67],[68].

Here we will consider only the case where the population is mostly monomorphic,

so that all proteins tend to have converged to the same stability before a new

mutation occurs (as is the case for the proteins shown in Figure 1). This choice is dictated by the

fact that we are unclear how to incorporate the secondary selection for

mutational robustness that occurs in highly polymorphic populations [31],[67],[68]. We

acknowledge that some of the proteins that we analyze later in this paper

(particularly influenza hemagglutinin) may actually evolve in populations that

are highly polymorphic, and suggest that a mathematical treatment recognizing

this fact is an area for future research. Given our choice to consider only the

case where the population is mostly monomorphic, we will adopt the mathematical

formalism described in [31] for the limit when

) [31],[67],[68].

Here we will consider only the case where the population is mostly monomorphic,

so that all proteins tend to have converged to the same stability before a new

mutation occurs (as is the case for the proteins shown in Figure 1). This choice is dictated by the

fact that we are unclear how to incorporate the secondary selection for

mutational robustness that occurs in highly polymorphic populations [31],[67],[68]. We

acknowledge that some of the proteins that we analyze later in this paper

(particularly influenza hemagglutinin) may actually evolve in populations that

are highly polymorphic, and suggest that a mathematical treatment recognizing

this fact is an area for future research. Given our choice to consider only the

case where the population is mostly monomorphic, we will adopt the mathematical

formalism described in [31] for the limit when  (the more compact diffusion-equation approach of Shakhnovich

and coworkers [32] cannot be used since it only applies when

(the more compact diffusion-equation approach of Shakhnovich

and coworkers [32] cannot be used since it only applies when  ). Following [31], we discretize the continuous variable of

extra protein stability

). Following [31], we discretize the continuous variable of

extra protein stability  into small bins of width

into small bins of width  , and assign a protein to bin

, and assign a protein to bin  if it has extra stability such that

if it has extra stability such that  , where

, where  . Here

. Here  is some large integer giving an upper limit on the number of

stability bins (so that all proteins in the evolving population have

is some large integer giving an upper limit on the number of

stability bins (so that all proteins in the evolving population have  ). Note that all folded proteins fall into one of these bins,

since proteins with

). Note that all folded proteins fall into one of these bins,

since proteins with  fail to fold under the stability threshold model. Reference

[31] finds that the distribution of average protein

stabilities is well approximated by an exponential (see the middle panels of

Figure 2 of this

reference, or alternatively Figure

2A of [29]), such that the probability

fail to fold under the stability threshold model. Reference

[31] finds that the distribution of average protein

stabilities is well approximated by an exponential (see the middle panels of

Figure 2 of this

reference, or alternatively Figure

2A of [29]), such that the probability  that a protein in the evolving population has extra stability

that falls in bin

that a protein in the evolving population has extra stability

that falls in bin  is

is

|

(3) |

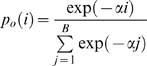

where  is a constant describing the steepness of the exponential.

Figure 2 shows this

distribution of protein stabilities graphically. Note that this exact

mathematical form for

is a constant describing the steepness of the exponential.

Figure 2 shows this

distribution of protein stabilities graphically. Note that this exact

mathematical form for  is not proven in [31], but simply that all

numerical solutions give distributions for

is not proven in [31], but simply that all

numerical solutions give distributions for  that resemble this form. Other mathematical forms could be

chosen for

that resemble this form. Other mathematical forms could be

chosen for  without altering the mathematical analysis that follows,

although they might affect the actual numerical values that are ultimately

inferred for the

without altering the mathematical analysis that follows,

although they might affect the actual numerical values that are ultimately

inferred for the  values. In particular, in highly polymorphic populations, the

distribution of stabilities is peaked at a value slightly below the stability

threshold (see right panels of Figure 2 of [31], Figure 2 of [32], or Figure 2B of [29]) rather than being

an exponential. However, any distribution in which highly stable proteins are

rare and marginally stable proteins are common should lead to qualitatively

similar inferred

values. In particular, in highly polymorphic populations, the

distribution of stabilities is peaked at a value slightly below the stability

threshold (see right panels of Figure 2 of [31], Figure 2 of [32], or Figure 2B of [29]) rather than being

an exponential. However, any distribution in which highly stable proteins are

rare and marginally stable proteins are common should lead to qualitatively

similar inferred  values, since the subsequent analysis only employs the

cumulative distribution function of

values, since the subsequent analysis only employs the

cumulative distribution function of  in a rather coarse manner. Given the definition of

in a rather coarse manner. Given the definition of  in Equation 3, the exact numerical for

in Equation 3, the exact numerical for  simply sets a scale for the

simply sets a scale for the  values (in conjunction with the bin size

values (in conjunction with the bin size  , it determines their units). As is described later in this

paper, in our actual computational implementation, we chose a value for

, it determines their units). As is described later in this

paper, in our actual computational implementation, we chose a value for  that placed the magnitude of the inferred

that placed the magnitude of the inferred  values in the same dynamic range as the informative priors.

values in the same dynamic range as the informative priors.

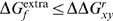

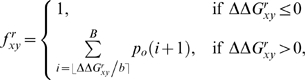

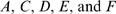

Figure 2. Stability distributions and fixation probabilities.

The panel at left show the probability  that a protein in an evolving population will have

extra stability

that a protein in an evolving population will have

extra stability  , as given by Equation 3. The panel at right shows the

probability

, as given by Equation 3. The panel at right shows the

probability  that a mutation that causes a stability change of

that a mutation that causes a stability change of  will be neutral, as given by Equation 4. The units for

will be neutral, as given by Equation 4. The units for  are arbitrary; for concreteness here we give them

units of kcal/mol.

are arbitrary; for concreteness here we give them

units of kcal/mol.

Using the mean-field approximation for  , the probability that a mutation is neutral can now be

computed from

, the probability that a mutation is neutral can now be

computed from  . Stabilizing mutations are always neutral, while destabilizing

mutations are neutral with a probability equal to the fraction of time they will

not unfold a protein with extra stability drawn from

. Stabilizing mutations are always neutral, while destabilizing

mutations are neutral with a probability equal to the fraction of time they will

not unfold a protein with extra stability drawn from  . Mathematically, the probability

. Mathematically, the probability  that mutating residue

that mutating residue  from

from  is neutral is

is neutral is

|

(4) |

where  is the nearest integer function. Figure 2 graphically illustrates the

probability that a mutation will be neutral given its

is the nearest integer function. Figure 2 graphically illustrates the

probability that a mutation will be neutral given its  value. Define

value. Define  to be the matrix with off-diagonal elements

to be the matrix with off-diagonal elements  and diagonal elements

and diagonal elements  . The probability that a substitution changes position

. The probability that a substitution changes position  of the protein from its original identity of amino acid

of the protein from its original identity of amino acid  to amino acid

to amino acid  after an elapsed time

after an elapsed time  is therefore given by element

is therefore given by element  of the matrix

of the matrix  defined by

defined by

| (5) |

where  is the per codon mutation rate as defined above. The previous

section showed that in the absence of selection for stability, the probability

of finding some specific amino acid at a position was equal for all positions in

the limit of long time. With selection for stability, this is no longer the

case. Let the probability

is the per codon mutation rate as defined above. The previous

section showed that in the absence of selection for stability, the probability

of finding some specific amino acid at a position was equal for all positions in

the limit of long time. With selection for stability, this is no longer the

case. Let the probability  of finding residue

of finding residue  at position

at position  in the long-time limit be given by element

in the long-time limit be given by element  of the vector

of the vector  . The vector

. The vector  represents the stationary solution to Equation 5, and so is

the probability vector (entries sum to one) that satisfies the eigenvector equation

represents the stationary solution to Equation 5, and so is

the probability vector (entries sum to one) that satisfies the eigenvector equation

| (6) |

where  is the identity matrix. Given a value of

is the identity matrix. Given a value of  , the uniqueness of

, the uniqueness of  is guaranteed by the Perron-Frobenius theorems, since

is guaranteed by the Perron-Frobenius theorems, since  is a nonnegative and acyclic stochastic matrix. Since

is a nonnegative and acyclic stochastic matrix. Since  depends on the

depends on the  values for the stability effects of mutations, the

probabilities of observing amino acids at specific positions in the sequence

depends on their stability contributions.

values for the stability effects of mutations, the

probabilities of observing amino acids at specific positions in the sequence

depends on their stability contributions.

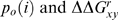

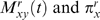

Bayesian framework for inferring  values from sequence data

values from sequence data

The previous section describes how the probabilities of specific substitutions to

an evolving protein are shaped by the set  of

of  values. In practice, we simply have some set

values. In practice, we simply have some set  of homologous protein sequences. The inference problem is how

to estimate

of homologous protein sequences. The inference problem is how

to estimate  from

from  . In so doing, we will also need to estimate

. In so doing, we will also need to estimate  , and the phylogenetic relationship among the sequences. The

approach we will take is to use Bayesian inference [18], [69]–[71] to estimate

, and the phylogenetic relationship among the sequences. The

approach we will take is to use Bayesian inference [18], [69]–[71] to estimate  from

from  . Sadly, the approach is not fully Bayesian, since

computational limitations require some important quantities to be estimated by

alternative means. Hopefully in the future, the computation can be recast in

fully Bayesian terms.

. Sadly, the approach is not fully Bayesian, since

computational limitations require some important quantities to be estimated by

alternative means. Hopefully in the future, the computation can be recast in

fully Bayesian terms.

The inference problem begins with the set  of homologous protein sequences. Here it is assumed that these

proteins have diverged from a common ancestor by point mutations (any

insertions/deletions are ignored), and that there is no recombination within the

protein coding sequences. It is further assumed that all of the homologous

sequences can be aligned in a fashion that puts their residues in a one-to-one

correspondence. In mathematical terms,

of homologous protein sequences. Here it is assumed that these

proteins have diverged from a common ancestor by point mutations (any

insertions/deletions are ignored), and that there is no recombination within the

protein coding sequences. It is further assumed that all of the homologous

sequences can be aligned in a fashion that puts their residues in a one-to-one

correspondence. In mathematical terms,  consists of

consists of  homologous sequences of length

homologous sequences of length  , with

, with  denoting the

denoting the  th sequence. For each sequence

th sequence. For each sequence  , we know the identity

, we know the identity  of the amino acid at position

of the amino acid at position  (where

(where  ). The set of amino acid identities for all

). The set of amino acid identities for all  proteins at a single site

proteins at a single site  is denoted by

is denoted by  . The evolutionary relationship among the sequences is given by

some phylogenetic tree

. The evolutionary relationship among the sequences is given by

some phylogenetic tree  . Here

. Here  is taken to specify both the topology and branch lengths of a

rooted phylogenetic tree, as shown in Figure 3.

is taken to specify both the topology and branch lengths of a

rooted phylogenetic tree, as shown in Figure 3.

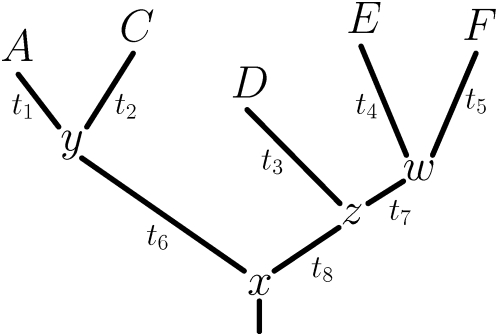

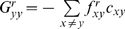

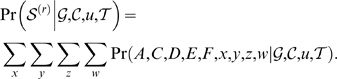

Figure 3. An example phylogenetic tree  .

.

This tree shows the sequence data  for five sequences at a single site

for five sequences at a single site  . The amino acid codes at the tips of the branches (

. The amino acid codes at the tips of the branches ( ) show the residue identities for the five sequences at

this site. The variables at the internal nodes (

) show the residue identities for the five sequences at

this site. The variables at the internal nodes ( ) are the amino acid identities at the site for the

ancestral sequences, and must be inferred. The branch lengths (

) are the amino acid identities at the site for the

ancestral sequences, and must be inferred. The branch lengths ( ) are proportional to the time since the divergence of

the sequences.

) are proportional to the time since the divergence of

the sequences.

Using the prescription of the previous section to calculate the substitution

probabilities, it is possible to calculate the likelihood  of observing some set of sequences given the

of observing some set of sequences given the  values. Here we briefly outline how this calculation would

proceed, closely paralleling the description by Felsenstein [18] of the pruning-based likelihood calculation

method he developed [72],[73]. Making the

standard phylogenetic assumption that evolution at each site is independent,

values. Here we briefly outline how this calculation would

proceed, closely paralleling the description by Felsenstein [18] of the pruning-based likelihood calculation

method he developed [72],[73]. Making the

standard phylogenetic assumption that evolution at each site is independent,

| (7) |

Consider the computation for some specific site  . Figure 3

shows the phylogenetic tree

. Figure 3

shows the phylogenetic tree  giving the evolutionary relationship among

giving the evolutionary relationship among  sequences, and the sequence data

sequences, and the sequence data  for site

for site  of these sequences. Given this tree in Figure 3, the likelihood for site

of these sequences. Given this tree in Figure 3, the likelihood for site  is computed by summing over the twenty possible amino acid

identities at each internal node,

is computed by summing over the twenty possible amino acid

identities at each internal node,

|

(8) |

Assuming the lineages are independent, the probabilities on the right side of Equation 8 can be decomposed as a product,

|

| (9) |

where the  values are calculated from

values are calculated from  using Equations 5 and 6. Note that Equation 9 assumes that the

sequences have evolved for a sufficiently long period of time that the

probability of observing residue

using Equations 5 and 6. Note that Equation 9 assumes that the

sequences have evolved for a sufficiently long period of time that the

probability of observing residue  at position

at position  at the root of the tree is the long-time limit

at the root of the tree is the long-time limit  . Using the pruning approach of Felsenstein, Equations 8 and 9

can be combined to yield

. Using the pruning approach of Felsenstein, Equations 8 and 9

can be combined to yield

|

|

(10) |

Equations 7 and 10 provide a method for computing  . But goal of this analysis is to infer the

. But goal of this analysis is to infer the  values from the sequences, which is equivalent to computing

values from the sequences, which is equivalent to computing  . Using Bayes' Theorem,

. Using Bayes' Theorem,

| (11) |

Solving this equation would yield a fully Bayesian inference of  by summing over the unknown variables

by summing over the unknown variables  . In principle, this equation could also be used to estimate

another phylogenetic variable (such as

. In principle, this equation could also be used to estimate

another phylogenetic variable (such as  ) by swapping this variable with

) by swapping this variable with  in the equation.

in the equation.

However, in practice, the approach taken here will not be the fully Bayesian

estimate given by Equation 11. Instead, to reduce the variable sampling space,

other methods will be used to make single-value estimates for each of  , so that

, so that

| (12) |

where  have been assigned fixed values. Given a prior

have been assigned fixed values. Given a prior  over the

over the  values, the right-hand side of Equation 12 can be estimated

numerically. One attractive aspect of this approach is that there is a basis for

specifying a meaningful prior over

values, the right-hand side of Equation 12 can be estimated

numerically. One attractive aspect of this approach is that there is a basis for

specifying a meaningful prior over  , since

, since  values can be measured experimentally [53],[74], or

more easily predicted with at least mild accuracy by one of the available

physicochemical modeling programs [1]–[8].

Equation 12 can in principle be solved by Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC)

methods [69]–[71] to yield a full

estimate of the probability distribution

values can be measured experimentally [53],[74], or

more easily predicted with at least mild accuracy by one of the available

physicochemical modeling programs [1]–[8].

Equation 12 can in principle be solved by Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC)

methods [69]–[71] to yield a full

estimate of the probability distribution  . But we are interested in obtaining estimates for the

individual

. But we are interested in obtaining estimates for the

individual  values contained in

values contained in  , since it is these values that have physical meaning.

Therefore, we take the

, since it is these values that have physical meaning.

Therefore, we take the  values of the maximum a posteriori value

values of the maximum a posteriori value  , defined as

, defined as

| (13) |

In the next section, we describe the specific computational approach we have used

to solve Equation 13 to obtain the  values from an alignment of homologous protein sequences.

values from an alignment of homologous protein sequences.

Implementation of a computational approach for inferring  values from sequence data

values from sequence data

In this section, we describe the computer program we have developed to infer  values from the sequences of protein homologs by solving

Equation 13. Solving this equation requires specification of the phylogenetic

tree

values from the sequences of protein homologs by solving

Equation 13. Solving this equation requires specification of the phylogenetic

tree  , the underlying amino acid mutation probabilities

, the underlying amino acid mutation probabilities  , the mutation rate

, the mutation rate  , and a prior distribution

, and a prior distribution  over the

over the  values. Solving the equation also requires a numerical method

for maximizing the argument of the

values. Solving the equation also requires a numerical method

for maximizing the argument of the  function. We implemented our strategy using the Python

programming language, and termed the resulting program PIPS

(Phylogenetic Inference of Protein

Stability). This program was used to analyze cold shock

protein, ribonuclease HI, thioredoxin, and H1 influenza hemagglutinin as

described below. The PIPS source code and the full raw data from the analyses in

this paper are available at http://openwetware.org/wiki/User:Jesse_Bloom.

function. We implemented our strategy using the Python

programming language, and termed the resulting program PIPS

(Phylogenetic Inference of Protein

Stability). This program was used to analyze cold shock

protein, ribonuclease HI, thioredoxin, and H1 influenza hemagglutinin as

described below. The PIPS source code and the full raw data from the analyses in

this paper are available at http://openwetware.org/wiki/User:Jesse_Bloom.

We built the phylogenetic tree  from the set

from the set  of homologous protein sequences using the PHYLIP package [75]. The protein sequences of the homologs were

aligned using ProbCons [76] (for cold shock protein, ribonuclease HI, and

thioredoxin) or MUSCLE [77] (for influenza hemagglutinin). Phylogenetic

trees of these aligned protein sequences were then constructed using the

distance-based method of PHYLIP's “neighbor”

program. For cold shock protein, ribonuclease HI, and thioredoxin, the trees

were built using the UPGMA method to create rooted trees that conformed to the

assumption of a molecular clock. For influenza hemagglutinin, the variation in

the date of isolation of the sequences is substantial relative to their

divergence, so the neighbor-joining method (no molecular clock) was used to

construct a tree which was rooted to an outgroup sequence.

of homologous protein sequences using the PHYLIP package [75]. The protein sequences of the homologs were

aligned using ProbCons [76] (for cold shock protein, ribonuclease HI, and

thioredoxin) or MUSCLE [77] (for influenza hemagglutinin). Phylogenetic

trees of these aligned protein sequences were then constructed using the

distance-based method of PHYLIP's “neighbor”

program. For cold shock protein, ribonuclease HI, and thioredoxin, the trees

were built using the UPGMA method to create rooted trees that conformed to the

assumption of a molecular clock. For influenza hemagglutinin, the variation in

the date of isolation of the sequences is substantial relative to their

divergence, so the neighbor-joining method (no molecular clock) was used to

construct a tree which was rooted to an outgroup sequence.

We calculated the underlying amino acid mutation probabilities  under the assumption that each amino acid was equally likely

to be encoded by any of its codons. The probability

under the assumption that each amino acid was equally likely

to be encoded by any of its codons. The probability  that a single mutation changed amino acid

that a single mutation changed amino acid  to

to  was the probability that a random nucleotide mutation to one

of the codons for

was the probability that a random nucleotide mutation to one

of the codons for  yielded a codon for

yielded a codon for  , averaged over all of the codons for

, averaged over all of the codons for  . There is evidence that the transition-to-transversion ratio

for influenza evolving in humans is somewhere in the range of five [78],

so for hemagglutinin we assumed that the nucleotide mutations were made with

this bias. We are aware of no clear evidence about the

transition-to-transversion ratio for cold shock protein, thioredoxin, and

ribonuclease HI, so for these proteins we assumed a ratio of 0.5, which is the

expectation in the absence of any mutational bias [79]. We recognize that

more accurate amino acid mutation probabilities are likely to be derived from a

codon-based model [59], and suggest that incorporating such a model

is an area for future work.

. There is evidence that the transition-to-transversion ratio

for influenza evolving in humans is somewhere in the range of five [78],

so for hemagglutinin we assumed that the nucleotide mutations were made with

this bias. We are aware of no clear evidence about the

transition-to-transversion ratio for cold shock protein, thioredoxin, and

ribonuclease HI, so for these proteins we assumed a ratio of 0.5, which is the

expectation in the absence of any mutational bias [79]. We recognize that

more accurate amino acid mutation probabilities are likely to be derived from a

codon-based model [59], and suggest that incorporating such a model

is an area for future work.

The mutation rate  represents the number of nucleotide mutations to a codon that

occur for each substitution that is fixed along the branches of the phylogenetic

tree (branch lengths are measured in amino acid substitutions per site). Since

our program is not yet sufficiently advanced to co-estimate

represents the number of nucleotide mutations to a codon that

occur for each substitution that is fixed along the branches of the phylogenetic

tree (branch lengths are measured in amino acid substitutions per site). Since

our program is not yet sufficiently advanced to co-estimate  from the sequence data, we had no strong rationale for

assigning a particular value to

from the sequence data, we had no strong rationale for

assigning a particular value to  . We chose a value of

. We chose a value of  , which corresponds to 20% of nucleotide mutations

leading to a tolerated amino acid mutation. While we cannot provide an

independent justification for this choice of

, which corresponds to 20% of nucleotide mutations

leading to a tolerated amino acid mutation. While we cannot provide an

independent justification for this choice of  , the inferred

, the inferred  values were fairly insensitive to the choice of

values were fairly insensitive to the choice of  for values between 3 and 20.

for values between 3 and 20.

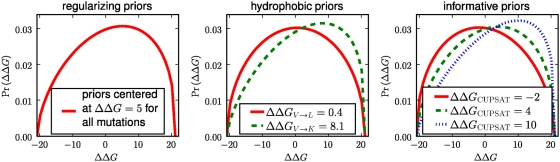

One of the strengths of our approach is that it allows for the use of informative

priors  over the

over the  values. These priors can serve two purposes. One purpose is

simply to prevent overfitting by regularizing [80] the

values. These priors can serve two purposes. One purpose is

simply to prevent overfitting by regularizing [80] the  values by biasing them towards a central reasonable range. A

second purpose is to actively incorporate some of the substantial existing

knowledge about how protein structure and amino-acid character influence

values by biasing them towards a central reasonable range. A

second purpose is to actively incorporate some of the substantial existing

knowledge about how protein structure and amino-acid character influence  values. One piece of this knowledge is simply the general fact

that most mutations to proteins are destabilizing, and so have

values. One piece of this knowledge is simply the general fact

that most mutations to proteins are destabilizing, and so have  . It is also known that mutations that cause large changes in

the hydrophobicity of amino acids are often more destabilizing. At a more

detailed level, there are a number of physicochemical modeling programs that

attempt to make quantitative predictions of

. It is also known that mutations that cause large changes in

the hydrophobicity of amino acids are often more destabilizing. At a more

detailed level, there are a number of physicochemical modeling programs that

attempt to make quantitative predictions of  values from protein structural information [1]–[8]. We tested

phylogenetic inference with priors incorporating information at all three of

these levels, as shown in Figure

4. At the most basic level, we used “regularizing

priors” that simply biased all the

values from protein structural information [1]–[8]. We tested

phylogenetic inference with priors incorporating information at all three of

these levels, as shown in Figure

4. At the most basic level, we used “regularizing

priors” that simply biased all the  values towards the generally observed range of mildly to

moderately destabilizing. A second set of “hydrophobic”

priors were based on the idea that mutations that cause large changes in amino

acid hydrophobicity will tend to be more destabilizing. For these priors, the

prior estimate for each

values towards the generally observed range of mildly to

moderately destabilizing. A second set of “hydrophobic”

priors were based on the idea that mutations that cause large changes in amino

acid hydrophobicity will tend to be more destabilizing. For these priors, the

prior estimate for each  value was equal to the absolute value of the difference in the

hydrophobicities of the wildtype and mutant amino acids, as given by the widely

used Kyte-Doolittle hydrophobicity scale [81]. These hydrophobic

priors therefore predicted that mutations that caused large changes in

hydrophobicity would be highly destabilizing (

value was equal to the absolute value of the difference in the

hydrophobicities of the wildtype and mutant amino acids, as given by the widely

used Kyte-Doolittle hydrophobicity scale [81]. These hydrophobic

priors therefore predicted that mutations that caused large changes in

hydrophobicity would be highly destabilizing ( ), while those that led to small changes in hydrophobicity

would have little effect on stability (

), while those that led to small changes in hydrophobicity

would have little effect on stability ( ). A third set of “informative priors” were

designed to leverage the full available knowledge about the effects of mutations

on stability. This knowledge is most completely encapsulated in various

physicochemically-based prediction programs [1]–[8],

which utilize a wide range of structural and biophysical information to make

quantitative

). A third set of “informative priors” were

designed to leverage the full available knowledge about the effects of mutations

on stability. This knowledge is most completely encapsulated in various

physicochemically-based prediction programs [1]–[8],

which utilize a wide range of structural and biophysical information to make

quantitative  predictions for individual mutations. We chose one of these

programs, CUPSAT [8], to predict

predictions for individual mutations. We chose one of these

programs, CUPSAT [8], to predict  values for all single amino-acid mutations from the protein

crystal structures. We chose the CUPSAT program because it has a publicly

available webserver (http://cupsat.tu-bs.de) and

has reported benchmarks that equal or exceed those of other prediction programs

[8]. The prior estimate for each mutation was then the

values for all single amino-acid mutations from the protein

crystal structures. We chose the CUPSAT program because it has a publicly

available webserver (http://cupsat.tu-bs.de) and

has reported benchmarks that equal or exceed those of other prediction programs

[8]. The prior estimate for each mutation was then the  value predicted by CUPSAT, after rescaling the predictions as

described below. For all three sets of priors, the prior

value predicted by CUPSAT, after rescaling the predictions as

described below. For all three sets of priors, the prior  for mutating residue

for mutating residue  from A to

from A to  was a beta distribution probability density function peaked at

the prior estimate for that mutation. The beta distribution functions were

defined so that the sum of the alpha and beta parameters equaled three, and with

the functions going to zero at the upper and lower limits of the allowed range

for the

was a beta distribution probability density function peaked at

the prior estimate for that mutation. The beta distribution functions were

defined so that the sum of the alpha and beta parameters equaled three, and with

the functions going to zero at the upper and lower limits of the allowed range

for the  values. These prior functions are therefore broad, and loosely

bias the

values. These prior functions are therefore broad, and loosely

bias the  values toward the prior estimates. Examples of the priors are

shown in Figure 4. The

overall prior probability for the set

values toward the prior estimates. Examples of the priors are

shown in Figure 4. The

overall prior probability for the set  of

of  values was defined to the be product of the prior

probabilities for the individual

values was defined to the be product of the prior

probabilities for the individual  values,

values,  .

.

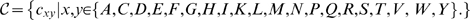

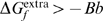

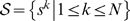

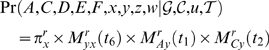

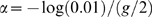

Figure 4. Prior distributions,  , over the

, over the  values.

values.

The “regularizing priors” are peaked at the

moderately destabilizing value of  to capture the general knowledge that most mutations

are destabilizing. The “hydrophobic priors” capture

the knowledge that mutations that cause large changes in hydrophobicity

are often more destabilizing. These priors are peaked at a value equal

the the absolute value of the difference in amino acid hydrophobicity

(as defined by the widely used Kyte-Doolittle scale [81]). For example, the prior for a mutation

from hydrophobic valine (V) to similarly hydrophobic leucine (L) is

peaked near zero, while that for mutation from valine to charged lysine

(K) is peaked at a much more destabilizing value. The

“informative priors” are peaked at the

to capture the general knowledge that most mutations

are destabilizing. The “hydrophobic priors” capture

the knowledge that mutations that cause large changes in hydrophobicity

are often more destabilizing. These priors are peaked at a value equal

the the absolute value of the difference in amino acid hydrophobicity

(as defined by the widely used Kyte-Doolittle scale [81]). For example, the prior for a mutation

from hydrophobic valine (V) to similarly hydrophobic leucine (L) is

peaked near zero, while that for mutation from valine to charged lysine

(K) is peaked at a much more destabilizing value. The

“informative priors” are peaked at the  values predicted by the state-of-the-art

physicochemically based program CUPSAT [8], and so

are designed to leverage extensive pre-existing knowledge about

values predicted by the state-of-the-art

physicochemically based program CUPSAT [8], and so

are designed to leverage extensive pre-existing knowledge about  values. All the priors are fairly loose to make the

values. All the priors are fairly loose to make the  values responsive to their effect on the likelihood.

The priors also help regularize [80] the

values responsive to their effect on the likelihood.

The priors also help regularize [80] the  predictions by biasing them towards a reasonable

range.

predictions by biasing them towards a reasonable

range.

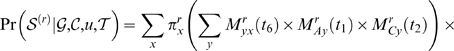

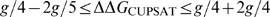

In order for the phylogenetic inference to work effectively, it is necessary that

the priors fall in the same numerical range over which the likelihood function

is responsive to changes in the  values. The actual

values. The actual  values of the phylogenetic inference approach have arbitrary

units, so placing the priors in an appropriate dynamic range simply requires

that the relevant parameters have compatible relative values. We set a

values of the phylogenetic inference approach have arbitrary

units, so placing the priors in an appropriate dynamic range simply requires

that the relevant parameters have compatible relative values. We set a  range of

range of  , so that for all

, so that for all  values,

values,  . The values of the bin size

. The values of the bin size  and the parameter

and the parameter  in Equation 3 are arbitrary, but serve to set the scale for

how

in Equation 3 are arbitrary, but serve to set the scale for

how  values affect the substitution probabilities. We chose a value

of

values affect the substitution probabilities. We chose a value

of  , and a value of

, and a value of  such that

such that  falls to one percent of its previous value every

falls to one percent of its previous value every  bins (this is

bins (this is  ). This scaling means that the substitution probabilities as a

function of the

). This scaling means that the substitution probabilities as a

function of the  values can cover a large dynamic range of four orders of

magnitude given the limits for the

values can cover a large dynamic range of four orders of

magnitude given the limits for the  values set by

values set by  . It is then necessary to choose priors that fall in the same

dynamic range. For the regularizing priors, the prior estimate had a value of

five for all

. It is then necessary to choose priors that fall in the same

dynamic range. For the regularizing priors, the prior estimate had a value of

five for all  values, which corresponds to a moderately destabilizing

mutation. For the hydrophobicity priors, we did not rescale the values obtained

by taking the absolute value of the difference in Kyte-Doolittle

hydrophobicities, since these values already fall in a reasonable range of zero

to nine. For the informative priors, we rescaled the

values, which corresponds to a moderately destabilizing

mutation. For the hydrophobicity priors, we did not rescale the values obtained

by taking the absolute value of the difference in Kyte-Doolittle

hydrophobicities, since these values already fall in a reasonable range of zero

to nine. For the informative priors, we rescaled the  values to bring them into an appropriate range. Specifically,

we rescaled them so that the difference between the values at the 10th and 90th

percentiles was

values to bring them into an appropriate range. Specifically,

we rescaled them so that the difference between the values at the 10th and 90th

percentiles was  and the mean

and the mean  value was

value was  , and truncated outlier values so that

, and truncated outlier values so that  .

.

Solving Equation 13 requires a numerical method for finding the value  of

of  that maximizes the a posteriori probability.

The

that maximizes the a posteriori probability.

The  values for the different positions of the protein are

independent, so we maximized the 19

values for the different positions of the protein are

independent, so we maximized the 19  values for each position separately. For each residue

values for each position separately. For each residue  , we first set the

, we first set the  values to random numbers drawn from a normal distribution with

a mean of zero and a standard deviation of

values to random numbers drawn from a normal distribution with

a mean of zero and a standard deviation of  . For each

. For each  , we then performed a line search to find the value that

represented the nearest local maximum in the a posteriori

probability. We repeated this procedure for the next

, we then performed a line search to find the value that

represented the nearest local maximum in the a posteriori

probability. We repeated this procedure for the next  value, until we had performed line searches for all 19 values.

This constituted one iteration of maximization of the

value, until we had performed line searches for all 19 values.

This constituted one iteration of maximization of the  values; we continued performing iterations until no further

local adjustments in any of the

values; we continued performing iterations until no further

local adjustments in any of the  values increased the a posteriori

probability. This maximization algorithm is stochastic, and we cannot guarantee

that it converges to the global maximum (or indeed converges at all). However,

in practice it always converged rapidly, and repeating the procedure with

different random starting values led to highly similar

values increased the a posteriori

probability. This maximization algorithm is stochastic, and we cannot guarantee

that it converges to the global maximum (or indeed converges at all). However,

in practice it always converged rapidly, and repeating the procedure with

different random starting values led to highly similar  values at the completion of the maximization. We considered

this ample evidence that this rather ad hoc algorithm was a

sufficient method for solving the

values at the completion of the maximization. We considered

this ample evidence that this rather ad hoc algorithm was a

sufficient method for solving the  function of Equation 13. Implementing a more sophisticated

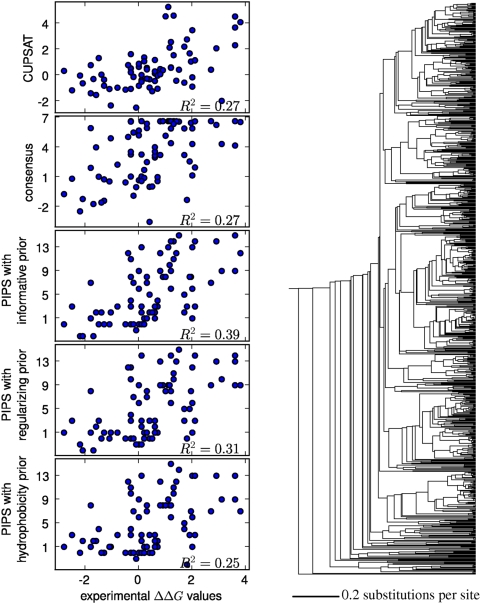

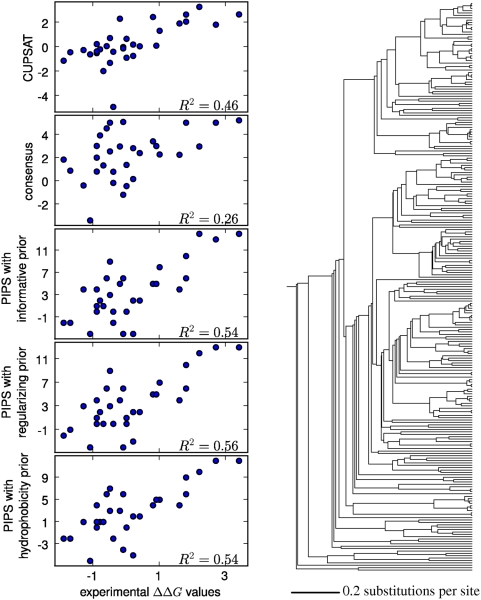

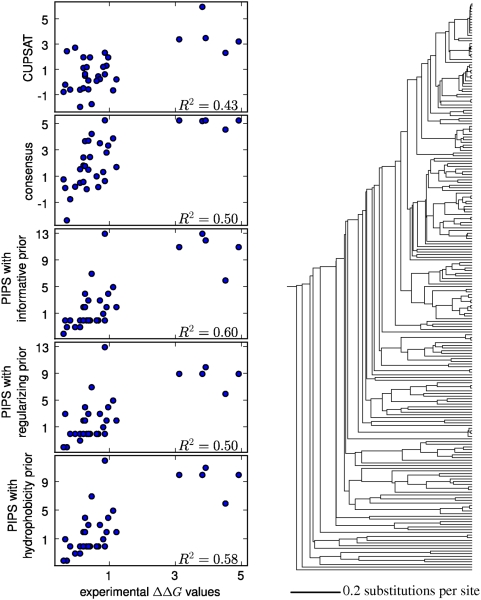

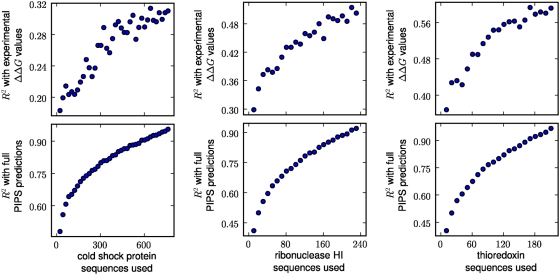

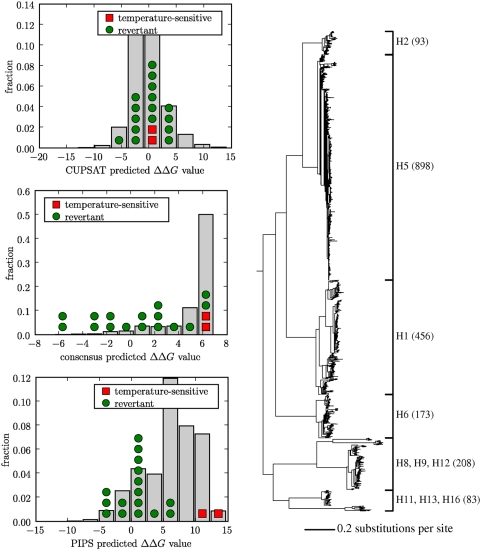

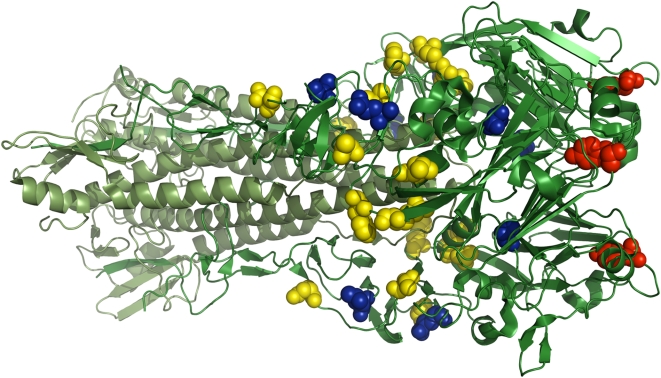

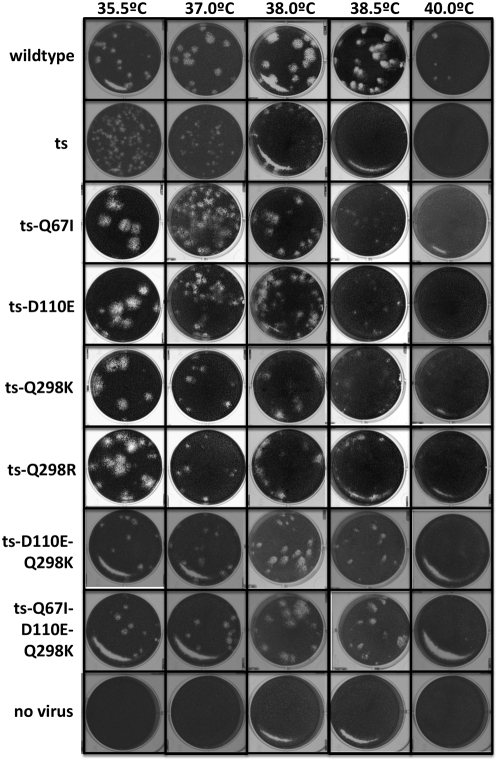

gradient-based maximization is an area for future research, and may lead to