Abstract

Oestrogen receptor β (ERβ) was discovered more than 10 years ago. It is widely distributed in the brain. In some areas, such as the entorhinal cortex, it is present as the only ER, whereas in other regions, such as the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and preoptic area, it can be found co-expressed with ERα, often within the same neurones. These ERs share ligands, and there are several complex relationships between the two receptors. Initially, the relationship between them was labelled as ‘yin/yang’, meaning that the actions of each complemented those of the other, but now, years later, other relationships have been described. Based on evidence from neuroendocrine and behavioural studies, three types of interactions between the two oestrogen receptors are described in this review. The first relationship is antagonistic; this is evident from studies on the role of oestrogen in spatial learning. When oestradiol is given in a high, chronic dose, spatial learning is impaired. This action of oestradiol requires ERα, and when ERβ is not functional, lower doses of oestradiol have this negative effect on behaviour. The second relationship between the two receptors is one that is synergistic, and this is illustrated in the combined effects of the two receptors on the production of the neuropeptide oxytocin and its receptor. The third relationship is sequential; separate actions of the two receptors are postulated in activation and organisation of sexually dimorphic reproductive behaviours. Future studies on all of these topics will inform us about how ER selective ligands might affect oestrogen functions at the organismal level.

Keywords: anxiety, lordosis, sexual behaviour, cognition, oxytocin

The first genetically engineered gene knockout (KO) mouse with direct applications to the study of neuroendocrinology was the oestrogen receptor (ER) knockout mouse (1). At the time that Dr Dennis Lubahn and his colleagues produced this mouse, only one ER had been sequenced (2, 3), and the idea of a second receptor was heretical. The ERKO mouse was phenotyped by a number of laboratories; their data indicated that mice with mutations for this receptor showed severe deficits in reproductive behaviours, and their hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal feedback loop was disrupted (4–8). These data were in agreement with the prevailing view that the ER was essential for reproduction at the level of the gonads, pituitary and brain. In 1996, the second ER (ERβ) was identified from a rat prostate cDNA library (9). Characterisation of ERβ revealed a 97% similarity between the two receptors in the DNA-binding domain, and the ligand-binding domains were 55% identical (10, 11). Initial hopes were that the new receptor would open up novel avenues of investigation that would have far-reaching applications, particularly for women’s health, where selective ligands might be used to individually treat reproductive disorders, cardiovascular disease, cancer, bone health, hot flushes, obesity and cognitive disorders.

The ERβ mouse knockout was created shortly thereafter, and the initial reproductive phenotype was not nearly as dramatic as that described in the ERαKO mouse (12). Females were subfertile, with ovarian defects accounting for fewer and smaller litters, while males were unremarkable; both displayed normal reproductive behaviour (13). The speculation from the results of these studies, along with brain localisation studies which described more ERβ than ERα outside the hypothalamus, particularly in the cerebellum, cortex and hippocampus (14–16), was that ERβ may mediate the effects of oestradiol (E2) on non-reproductive behaviours (10, 17, 18).

Antagonistic actions and cognitive behaviours

The role of oestrogens in cognitive behaviours was an exciting research topic in the 1990s, and the arrival of ERβ was heralded as a potential tool to advance women’s health research. This was before the release of the first data from the National Institutes of Health’s Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) which all but shut down exploration of new oestrogen ligands for hormonal replacement therapy (HRT). The WHI results indicated that the treatment regimes under test (oestrogen and progestins) placed post-menopausal women at increased risk of several diseases, with no benefit for cognition (19–21). Closer consideration of the statistical analysis and design of these studies has since placed such a simplistic conclusion in doubt (22–25).

Soon after the ERβKO mice were made by Dr Jan-Ake Gustaffson and his group (12), we started a colony at the University of Virginia. Our ERαKO colony (provided by Dr Dennis Lubahn) was already established, and we were anxious to compare behaviour in the two mice side by side. Our simplistic hypothesis, based on the phenotype of the ERαKO and the location of ERβ in the brain, was that ERβ mediated the beneficial actions of oestrogens on cognition. Because most of the initial research was conducted in rats, we needed to design a comparable behavioural task for mice. We shrank the Morris water maze down to a negotiable size for mice and increased the time needed to learn the task. Before the ERβKO and their wild-type (WT) littermates were available, we tested the effects of different E2 doses in WT C57BL/6J mice on their performance on the Morris water maze. Because one of our other major interests was in sex differences, we used gonadectomised adult males and females treated with either vehicle or E2. Previous work in rodents had shown that males were superior to females in this spatial task (26, 27). However, the studies were conducted in gonad-intact animals, and thus the sex differences reported might have been caused by neural organisational differences or by differences in hormone levels at the time of testing. We wanted to pinpoint which one of these mechanisms was involved before switching to animals with gene mutations. One of the drawbacks of working with adult knockout mice is that, if a behavioural problem is found, it is impossible to know if the loss of oestrogen receptors during development or in adulthood was critical.

In our pilot studies, we were surprised that gonadectomised males and female mice performed equally well in the water maze; in fact there was a trend for ovariectomised females to escape more rapidly than castrated males (28). Moreover, ERαKO mice of both sexes did well on this task, and counter to the prevalent idea that oestrogens have positive effects on cognition, learning was impaired in E2-injected WT females. Others showed later that the dosage of E2 treatment is a critical factor for the direction of the effects of oestrogens on learning behaviour, and high doses, like the one we used, may impair various types of learning (29–32). While the fact that ERαKO mice behaved as well as, if not better than, their WT littermates was surprising, it allowed us to test our hypothesis that ERβ was the important oestrogen receptor for spatial learning.

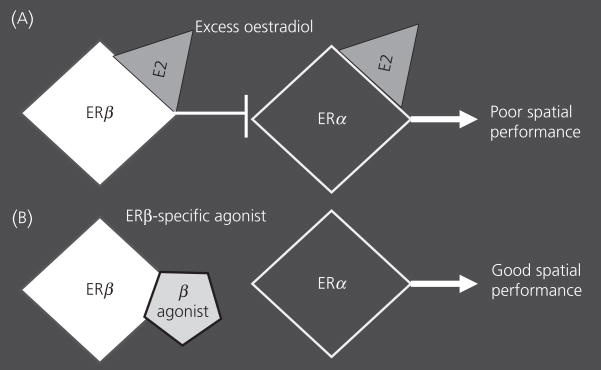

Because the effect of E2 was only noted in females, we restricted our next study to female ERβKO and WT littermates (33). We changed the route of E2 administration from injections to Silastic implants filled with either a high or a low dose of E2. In this study, all of the WT ovariectomised females that were treated or not with E2 exhibited equivalent spatial learning. Only the ERβKO females treated with E2 showed impaired learning. At the low dose, the effect was on the first few testing days and ERβKO females ‘caught up’ with WT females by the last day. Females with the ERβ mutation that were treated with the high E2 dose took significantly longer to escape than WT females. Taken together with the earlier data showing that ERαKO females were less vulnerable to the negative effects of E2, we hypothesised that, in WT females, the detrimental effect of large doses of E2 is mediate by the ERα; when ERβ is present, more E2 is needed to affect behaviour; in contrast, when ERβ is absent, lower doses of E2 can disrupt cognition (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

This cartoon illustrates the antagonistic relationship between the two oestrogen receptors (ERs). The white diamond represents ERβ, the black diamond represents ERα, and the grey triangle is oestradiol activating the receptors. An ERβ-specific agonist is represented by the off-grey pentagon. (A) The example shows the impact of excess oestradiol on the two ERs and the resulting behaviour. (B) The relationship is shown when an ERβ agonist is used.

A recent set of behavioural and electrophysiological studies reported specific facilitatory roles for ERβ in learning spatial tasks using both KO mice and rats (34; Fig. 1B). When provided with E2, or an ERβ-specific agonist (Way-200070), ovariectomised female rats performed well in a radial arm maze task, better than females treated with an ERα-specific agonist (PPT) or vehicle. In a water Y maze task, WT female mice treated with E2 outperformed ERβKO mice regardless of their treatment. These behavioural data complement studies carried out in vitro showing opposite and/or antagonistic actions of ERα and β. Observations from ERα/ERβ heterodimers, which act in the opposite direction to ERα-only heterodimers, support the yin/yang concept (35). When HeLa cells, transfected with ERs, are exposed to the classic oestrogen receptor antagonist tamoxifen, mixed antagonistic and agonistic effects are apparent on ERα transcription; however, tamoxifen has an exclusively antagonistic action on ERβ (36). In addition, when E2 is present, ERα induces transcription of the cyclin D1 gene via the activator protein 1 (AP1) in HeLa cells (37). In contrast, anti-oestrogens activate ERβ to induce cyclin D1. In summary, both in vitro and in vivo data suggest that E2 effects are often caused by antagonistic actions between the two ERs (38).

Synergistic actions of ERα and ERβ in neuroendocrinology

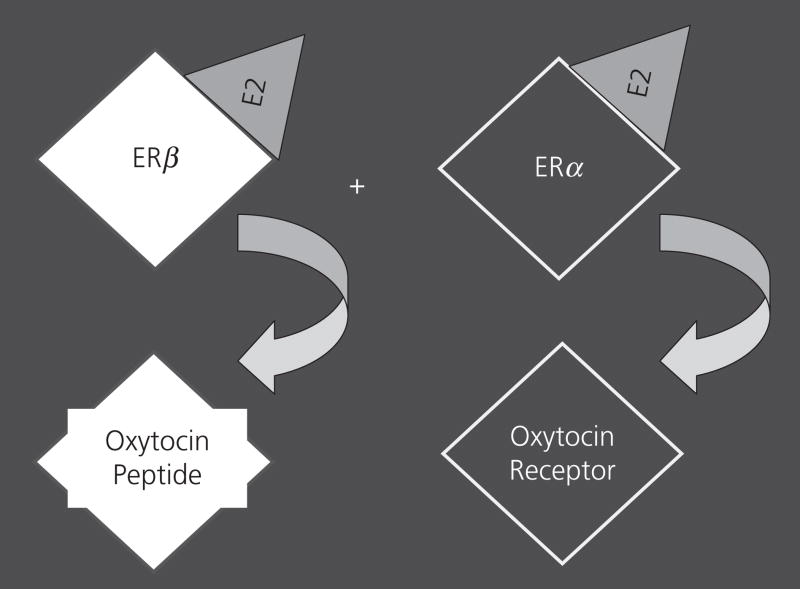

Oestrogen receptors act as transcription factors to regulate many downstream genes, including those encoding neurotransmitters and peptides. Another way to distinguish the actions of ERα and β is to ask which genes are regulated by each ER. Oestrogens can enhance the actions of the neuropeptide oxytocin, by increasing the production of both the peptide and its receptor (39–42). The supraoptic area and the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) contain the vast majority of the oxytocin-producing cells. In rats, ERβ is more highly expressed in the PVN than is ERα, whereas the rest of the hypothalamus has both ERs, with more ERα than ERβ in some locations (i.e. the ventromedial nucleus) (43). Moreover, after ERβ was discovered, several studies reported co-localisation of ERβ within oxytocin-producing neurones in the rat PVN (44–46) and later in the mouse (47). In collaboration with Drs Heather Patisaul and Larry Young, we asked which ER induced oxytocin and its receptor. Using gonadectomised WT and ERαKO mice of both sexes, we treated some animals with E2 and others with vehicle. Regardless of sex, E2 induced oxytocin binding (a reflection of receptor abundance) throughout the hypothalamus. This response was blocked in ERαKO mice (48). In another study we used ERβKO and WT female mice to examine oxytocin mRNA in the PVN. In this study, hormone priming was conducted, followed by in situ hybridisation. Oxytocin mRNA was elevated in the WT PVN after hormone treatment, but not in the ERβKO brain (47). As confirmation of the early data on the oxytocin receptor, in both the WT and ERβKO female mice, receptor message in the hypothalamus and amygdala was induced with hormone priming. This is an example of both an autonomous and a synergistic relationship, as ERβ increases the amount of oxytocin peptide produced, and ERα increases expression of its receptor (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

This cartoon figure illustrates the synergistic relationship between the two oestrogen receptors (ERs). The white diamond represents ERβ, the black diamond represents ERα, and the grey triangle is oestradiol activating the receptors. Below each receptor is the oxytocin gene that it affects.

A different type of ER synergy has been noted in the anteroventral periventricular nucleus (AVPV), a subregion of the medial preoptic area. The cells in this area are sexually dimorphic, with females having more than males (49). Often the population of cells is revealed with immunocytochemistry for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), and the TH-positive labelled neurones in the AVPV are known to produce dopamine. Not only is this a structural sex difference, but it is also functional as the dopamine-containing neurones project to nearby gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH)-containing cells, and are thought to be involved in the ovulatory release of GnRH from these cells (50). Studies with the ERαKO mouse showed that WT females had more cells positive for TH in the AVPV than WT males, ERαKO males or ERαKO females (51). At the time this observation was made, ERβ had just been discovered, and thus little was made of the fact that ERαKO males and females had AVPV cell numbers that were not completely ‘female-like’ and instead were intermediate between WT males and females. A few years ago we decided to revisit this question of ER regulation and labelled neurones in the AVPV with TH in brains of mice from both ERKO strains and double-KO individuals (52). Only in WT individuals was the sex difference in the AVPV present. All the KO mice, both males and females, had ‘female-like’ high numbers of dopaminergic neurones in the AVPV. These data showed that the two ERs work in concert in this region to elaborate the sex difference in cell numbers. We presumed that the actions occurred during development as this sex difference is organised prior to postnatal day 7 in rats (49, 53). Interestingly, ERαKO females lack positive and negative feedback to E2 (8, 54), and ERβKO mice have normal negative feedback but ovulate a reduced number of ova as compared with WT females (12, 55). Afferents from GnRH neurones are specifically associated with ERα-containing neurones in the AVPV, suggesting that the ERα in the AVPV is directly involved in GnRH regulation (54).

Sequential actions of ERα and ERβ

One of the most important and unifying concepts in the field of behavioural neuroendocrinology is that steroid hormones act at two distinct and sequential times in the lifespan to affect behaviours (56, 57). The first occurs during development, in which steroids act (via their receptors) to shape neural cell clusters and connections, and the second occurs in adulthood, in which steroids activate gene transcription which ultimately results in a behavioural change. In many of the animals used for these studies, the major steroid involved at both time-points is E2 (58). When the ERαKO mouse first became available, and tests for sexually differentiated behaviours were conducted by our group and Drs Don Pfaff and Sonoko Ogawa, we found severe deficits in male sexual behaviour, female sexual behaviour, and partner preferences (4, 6, 7, 17, 59–61). Because the ERα gene mutation is present at all times of the lifespan, these data revealed nothing about when ERα is critical.

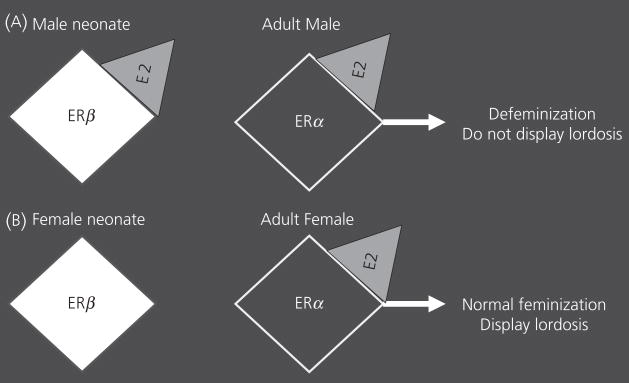

By contrast, ERβKO males display normal male sexual behaviour and partner preferences (13, 62) while the female ERβKO mice have normal, if not enhanced, lordosis (the female receptivity posture) (13, 63). Taken together, these findings suggest that ERβ is not essential for development and for the expression of sex-typical behaviours; lordosis in females, and partner preferences in males. However, a true test of the organisational effects of a specific receptor cannot be performed unless you examine opposite sex-typical behaviours. To do this, you need to determine whether females can display partner preferences or males can perform lordosis. Thus we started by testing ERβKO males for lordosis. When treated with activational hormones, identical to the treatments given to ovariectomised females to hormonally prime them to become sexually receptive, we found that ERβKO males had higher levels of lordosis than WT males (62), but the ERβKO males displayed male partner preferences similar to those of WT males. To confirm our hypothesis that ERβ is required in development for ‘defeminisation’ in males, we asked if treatment with a selective ERβ agonist during the perinatal period would also ‘defeminise’ females. We injected pups from the day of birth for three consecutive days with E2, the ERα agonist PPT, an ERβ agonist (DPN) or vehicle. E2 and DPN animals had reduced lordosis expression in adulthood as compared with females that received PPT or vehicle (64). These data show that the activation of the ERβ during the early postnatal period blocks development of female-typical lordosis (Fig. 3). Our hypothetical model suggests that ERβ is activated normally in the perinatal male, and this activation selectively defeminises adult behavioural potential without affecting masculinization of male-typical behaviours.

Fig. 3.

This cartoon illustrates a sequential relationship between the two oestrogen receptors (ERs) during development. The white diamond represents ERβ, the black diamond represents ERα, and the grey triangle is oestradiol activating the receptors. (A) An illustration of the roles of ERβ activation in neonatal males followed by activation of the ERα in adult males. The end result of the two actions is defeminisation of adult male behaviour. (B) An illustration of the situation in a normal female. Here, the lack of ERβ activation in the neonatal period is responsible for the adult activational effect of oestradiol on lordosis.

Data on neural sexual dimorphisms support this hypothesis. We treated adult WT and ERβKO gonadectomised mice with either vehicle or E2, and then processed their brains for ERα and progestin receptor (PR) immunoreactivity (ir) (65). E2 treatment promoted a reduction in ERα-ir cells in the preoptic area, arcuate nucleus and the ventromedial nucleus (VMN) of WT males when compared with their vehicle-treated male counterparts, but E2 had no effect in these areas in WT females. In ERβKO males, E2 treatment also had no effect. The difference between the WT and ERβKO males and the similarity between WT females and ERβKO males suggests that ERβ activation during development makes ERα in brains of WT males more sensitive to the down-regulatory effects of E2 in adulthood. When we examined PR-ir cell numbers in the same regions, we noted that, in areas and animals were ERα-ir was not decreased by E2, PR-ir was enhanced by this same treatment. Sex differences between WT males and females were noted in the preoptic area and VMN, and ERβKO males again had the same pattern as did WT females. Thus ERβ may act during development in the normal male brain to ‘defeminise’ adult responses to E2.

What does the future hold?

Over the past 10 years much has been uncovered about the relationship between ERα and ERβ, but we have a long way to go to unravel the complexity of relationships between the two receptors. New technologies are being used to enhance the ER ‘tool box’. Examination of the roles of ERα in hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal feedback has been elegantly accomplished with tissue-specific ERαKO mice. In these transgenics the ERα gene is knocked out only in the brain (54). Moreover, development of conditional and tissue-specific KO mice would greatly enhance the possibilities for brain research. Mice with ERβ tagged with green fluorescent protein (GFP) make identification of these cells in vitro or in vivo easier (http://www.gensat.org). Agonists and specific antagonists for the ERs are very useful as they can be used to ask questions about ER actions in any animal, and at any time during development, whereas the KO work has been limited to mice and the classic models remove the receptors at all times in the lifespan. The technologies for the use of siRNA to block specific gene transcription are becoming more specific and simpler all the time (http://www.ambion.com/techlib/tn/131/5.html). We can anticipate new discoveries based on these improved technologies.

Several new developments have broadened our view of ERβ. For example, a metabolite of dihydrotestosterone, 5α-androstane-3β,17β-diol (3β-diol), acts on ERβ, but not ERα (66). ERβ is present in the prostate [this is one of the tissues in which ERβ was discovered (9)] and is activated there not only by oestrogens, but importantly by 3β-diol (66, 67). Moreover, this certainly occurs in the brain. For example, ERβ appears to mediate oestrogen action on anxiety (68, 69). However, ERβ may also mediate anxiolytic actions of testosterone on anxiety (70). The discovery of this endogenous specific ligand for ERβ opens a new frontier for examining independent actions of this ER.

In our laboratory, sex differences are a major research focus and thus we are currently asking how ERβ ‘defeminises’ the male brain during development. Others are also studying this, and one very applicable aspect of this work stems from the fact that environmental oestrogens and phytoestrogens preferential activate the ERβ (71, 72). Documentation of actions of environmental oestrogens and phytoestrogens during development in animal models is underway and the relevance to human development, particularly in infants on soy-based formula, is potentially enormous (72–74). While the scientific community initially hoped that the discovery of ERβ would produce new HRT treatments, through the power and imagination of basic science research we now have several other, equally exciting, ideas about ERβ and the translational value to human medicine is vast.

Acknowledgments

I thank Dr Jin Ho Park for constructive comments on this manuscript. My laboratory is indebted to Aileen Wills and Savera Shetty for expert technical assistance. The work referenced here from my laboratory was funded by NIH (MH057759).

References

- 1.Lubahn DB, Moyer JS, Golding TS, Couse JF, Korach KS, Smithies O. Alteration of reproductive function but not prenatal sexual development after insertional disruption of the mouse estrogen receptor gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11162–11166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green S, Walter P, Greene G, Krust A, Goffin C, Jensen E, Scrace G, Waterfield M, Chambon P. Cloning of the human oestrogen receptor cDNA. J Steroid Biochem. 1986;24:77–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(86)90035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White R, Lees JA, Needham M, Ham J, Parker M. Structural organization and expression of the mouse estrogen receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 1987;1:735–744. doi: 10.1210/mend-1-10-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogawa S, Lubahn DB, Korach KS, Pfaff DW. Behavioral effects of estrogen receptor gene disruption in male mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1476–1481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogawa S, Lubahn DB, Korach KS, Pfaff DW. Aggressive behaviors of transgenic estrogen-receptor knockout male mice. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1996;794:384–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb32549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rissman EF, Early AH, Taylor JA, Korach KS, Lubahn DB. Estrogen receptors are essential for female sexual receptivity. Endocrinology. 1997;138:507–510. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.1.4985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rissman EF, Wersinger SR, Taylor JA, Lubahn DB. Estrogen receptor function as revealed by knockout studies: neuroendocrine and behavioral aspects. Horm Behav. 1997;31:232–243. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1997.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wersinger SR, Haisenleder DJ, Lubahn DB, Rissman EF. Steroid feedback on gonadotropin release and pituitary gonadotropin subunit mRNA in mice lacking a functional estrogen receptor alpha. Endocrine. 1999;11:137–143. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:11:2:137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuiper GG, Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA. Cloning of a novel receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5925–5930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gustafsson JA. Estrogen receptor beta – a new dimension in estrogen mechanism of action. J Endocrinol. 1999;163:379–383. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1630379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harrington WR, Sheng S, Barnett DH, Petz LN, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS. Activities of estrogen receptor alpha- and beta-selective ligands at diverse estrogen responsive gene sites mediating transactivation or transrepression. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;206:13–22. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(03)00255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krege JH, Hodgin JB, Couse JF, Enmark E, Warner M, Mahler JF, Sar M, Korach KS, Gustafsson JA, Smithies O. Generation and reproductive phenotypes of mice lacking estrogen receptor beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15677–15682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogawa S, Chan J, Chester AE, Gustafsson JA, Korach KS, Pfaff DW. Survival of reproductive behaviors in estrogen receptor beta gene-deficient (betaERKO) male and female mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12887–12892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li X, Schwartz PE, Rissman EF. Distribution of estrogen receptor-beta-like immunoreactivity in rat forebrain. Neuroendocrinology. 1997;66:63–67. doi: 10.1159/000127221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shughrue PJ, Komm B, Merchenthaler I. The distribution of estrogen receptor-beta mRNA in the rat hypothalamus. Steroids. 1996;61:678– 681. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(96)00222-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitra SW, Hoskin E, Yudkovitz J, Pear L, Wilkinson HA, Hayashi S, Pfaff DW, Ogawa S, Rohrer SP, Schaeffer JM, McEwen BS, Alves SE. Immunolocalization of estrogen receptor beta in the mouse brain: comparison with estrogen receptor alpha. Endocrinology. 2003;144:2055–2067. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-221069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rissman EF, Wersinger SR, Fugger HN, Foster TC. Sex with knockout models: behavioral studies of estrogen receptor alpha. Brain Res. 1999;835:80–90. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gustafsson JA. New insights in oestrogen receptor (ER) research - the ERbeta. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36(Suppl 4):S16. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rapp SR, Espeland MA, Shumaker SA, Henderson VW, Brunner RL, Manson JE, Gass ML, Stefanick ML, Lane DS, Hays J, Johnson KC, Coker LH, Dailey M, Bowen D. Effect of estrogen plus progestin on global cognitive function in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2663–2672. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.20.2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, Jackson RD, Beresford SA, Howard BV, Johnson KC, Kotchen JM, Ockene J Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, Bassford T, Beresford SA, Black H, Bonds D, Brunner R, Brzyski R, Caan B, Chlebowski R, Curb D, Gass M, Hays J, Heiss G, Hendrix S, Howard BV, Hsia J, Hubbell A, Jackson R, Johnson KC, Judd H, Kotchen JM, Kuller L, LaCroix AZ, Lane D, Langer RD, Lasser N, Lewis CE, Manson J, Margolis K, Ockene J, O’Sullivan MJ, Phillips L, Prentice RL, Ritenbaugh C, Robbins J, Rossouw JE, Sarto G, Stefanick ML, Van Horn L, Wactawski-Wende J, Wallace R, Wassertheil-Smoller S Women’s Health Initiative Steering Committee. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1701–1712. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lemay A. The relevance of the Women’s Health Initiative results on combined hormone replacement therapy in clinical practice. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2002;24:711–715. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30326-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mastorakos G, Sakkas EG, Xydakis AM, Creatsas G. Pitfalls of the WHIs: Women’s Health Initiative. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1092:331– 340. doi: 10.1196/annals.1365.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wise PM, Dubal DB, Rau SW, Brown CM, Suzuki S. Are estrogens protective or risk factors in brain injury and neurodegeneration? Reevaluation after the Women’s health initiative. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:308–312. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Utian WH. NIH and WHI: time for a mea culpa and steps beyond. Menopause. 2007;14:1056–1059. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181589bfe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perrot-Sinal TS, Kostenuik MA, Ossenkopp KP, Kavaliers M. Sex differences in performance in the Morris water maze and the effects of initial nonstationary hidden platform training. Behav Neurosci. 1996;110:1309–1320. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.110.6.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gresack JE, Frick KM. Male mice exhibit better spatial working and reference memory than females in a water-escape radial arm maze task. Brain Res. 2003;982:98–107. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03000-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fugger HN, Cunningham SG, Rissman EF, Foster TC. Sex differences in the activational effect of ERalpha on spatial learning. Horm Behav. 1998;34:163–170. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1998.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galea LA, Wide JK, Barr AM. Estradiol alleviates depressive-like symptoms in a novel animal model of post-partum depression. Behav Brain Res. 2001;122:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00170-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galea LA, Wide JK, Paine TA, Holmes MM, Ormerod BK, Floresco SB. High levels of estradiol disrupt conditioned place preference learning, stimulus response learning and reference memory but have limited effects on working memory. Behav Brain Res. 2001;126:115–126. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00255-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holmes MM, Wide JK, Galea LA. Low levels of estradiol facilitate, whereas high levels of estradiol impair, working memory performance on the radial arm maze. Behav Neurosci. 2002;116:928–934. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.5.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wide JK, Hanratty K, Ting J, Galea LA. High level estradiol impairs and low level estradiol facilitates non-spatial working memory. Behav Brain Res. 2004;155:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rissman EF, Heck AL, Leonard JE, Shupnik MA, Gustafsson JA. Disruption of estrogen receptor beta gene impairs spatial learning in female mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3996–4001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012032699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu F, Day M, Muniz LC, Bitran D, Arias R, Revilla-Sanchez R, Grauer S, Zhang G, Kelley C, Pulito V, Sung A, Mervis RF, Navarra R, Hirst WD, Reinhart PH, Marquis KL, Moss SJ, Pangalos MN, Brandon NJ. Activation of estrogen receptor-beta regulates hippocampal synaptic plasticity and improves memory. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:334–343. doi: 10.1038/nn2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hall JM, McDonnell DP. The estrogen receptor beta-isoform (ERbeta) of the human estrogen receptor modulates ERalpha transcriptional activity and is a key regulator of the cellular response to estrogens and antiestrogens. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5566–5578. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.12.7179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paech K, Webb P, Kuiper GG, Nilsson S, Gustafsson J, Kushner PJ, Scanlan TS. Differential ligand activation of estrogen receptors ERalpha and ERbeta at AP1 sites. Science. 1997;277:1508–1510. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu MM, Albanese C, Anderson CM, Hilty K, Webb P, Uht RM, Price RH, Jr, Pestell RG, Kushner PJ. Opposing action of estrogen receptors alpha and beta on cyclin D1 gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24353–24360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201829200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindberg MK, Moverare S, Skrtic S, Gao H, Dahlman-Wright K, Gustafsson JA, Ohlsson C. Estrogen receptor (ER)-beta reduces ERalpha-regulated gene transcription, supporting a “ying yang” relationship between ERalpha and ERbeta in mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:203–208. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCarthy MM. Estrogen modulation of oxytocin and its relation to behavior. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;395:235–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shughrue PJ, Dellovade TL, Merchenthaler I. Estrogen modulates oxytocin gene expression in regions of the rat supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei that contain estrogen receptor-beta. Prog Brain Res. 2002;139:15–29. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(02)39004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schumacher M, Coirini H, Flanagan LM, Frankfurt M, Pfaff DW, McEwen BS. Ovarian steroid modulation of oxytocin receptor binding in the ventromedial hypothalamus. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1992;652:374–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb34368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bale TL, Dorsa DM. Regulation of oxytocin receptor messenger ribonucleic acid in the ventromedial hypothalamus by testosterone and its metabolites. Endocrinology. 1995;136:5135–5138. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.11.7588251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shughrue PJ, Lane MV, Merchenthaler I. Comparative distribution of estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta mRNA in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 1997;388:507–525. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971201)388:4<507::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laflamme N, Nappi RE, Drolet G, Labrie C, Rivest S. Expression and neuropeptidergic characterization of estrogen receptors (ERalpha and ERbeta) throughout the rat brain: anatomical evidence of distinct roles of each subtype. J Neurobiol. 1998;36:357–378. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19980905)36:3<357::aid-neu5>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hrabovszky E, Kallo I, Hajszan T, Shughrue PJ, Merchenthaler I, Liposits Z. Expression of estrogen receptor-beta messenger ribonucleic acid in oxytocin and vasopressin neurones of the rat supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei. Endocrinology. 1998;139:2600–2604. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.5.6024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simonian SX, Herbison AE. Differential expression of estrogen receptor alpha and beta immunoreactivity by oxytocin neurons of rat paraventricular nucleus. J Neuroendocrinol. 1997;9:803–806. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1997.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patisaul HB, Scordalakes EM, Young LJ, Rissman EF. Oxytocin, but not oxytocin receptor, is regulated by oestrogen receptor beta in the female mouse hypothalamus. J Neuroendocrinol. 2003;15:787–793. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.01061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Young LJ, Wang Z, Donaldson R, Rissman EF. Estrogen receptor alpha is essential for induction of oxytocin receptor by estrogen. Neuroreport. 1998;9:933–936. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199803300-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simerly RB. Hormonal control of the development and regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase expression within a sexually dimorphic population of dopaminergic cells in the hypothalamus. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1989;6:297–310. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(89)90075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Polston EK, Simerly RB. Ontogeny of the projections from the anteroventral periventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus in the female rat. J Comp Neurol. 2006;495:122–132. doi: 10.1002/cne.20874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simerly RB, Zee MC, Pendleton JW, Lubahn DB, Korach KS. Estrogen receptor-dependent sexual differentiation of dopaminergic neurons in the preoptic region of the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14077–14082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.14077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bodo C, Kudwa AE, Rissman EF. Both estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta are required for sexual differentiation of the anteroventral periventricular area in mice. Endocrinology. 2006;147:415–420. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simerly RB. Wired on hormones: endocrine regulation of hypothalamic development. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:81–85. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wintermantel TM, Campbell RE, Porteous R, et al. Definition of estrogen receptor pathway critical for estrogen positive feedback to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons and fertility. Neuron. 2006;52:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Temple JL, Scordalakes EM, Bodo C, Gustafsson JA, Rissman EF. Lack of functional estrogen receptor beta gene disrupts pubertal male sexual behavior. Horm Behav. 2003;44:427–434. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arnold AP, Breedlove SM. Organizational and activational effects of sex steroids on brain and behavior: a reanalysis. Horm Behav. 1985;19:469–498. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(85)90042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Phoenix CH, Goy RW, Gerall AA, Young WC. Organizing action of prenatally administered testosterone propionate on the tissues mediating mating behavior in the female guinea pig. Endocrinology. 1959;65:369–382. doi: 10.1210/endo-65-3-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCarthy MM. Estradiol and the developing brain. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:91–124. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00010.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wersinger SR, Sannen K, Villalba C, Lubahn DB, Rissman EF, De Vries GJ. Masculine sexual behavior is disrupted in male and female mice lacking a functional estrogen receptor alpha gene. Horm Behav. 1997;32:176–183. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1997.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ogawa S, Washburn TF, Taylor J, Lubahn DB, Korach KS, Pfaff DW. Modifications of testosterone-dependent behaviors by estrogen receptor-alpha gene disruption in male mice. Endocrinology. 1998;139:5058–5069. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.12.6358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ogawa S, Eng V, Taylor J, Lubahn DB, Korach KS, Pfaff DW. Roles of estrogen receptor-alpha gene expression in reproduction-related behaviors in female mice. Endocrinology. 1998;139:5070–5081. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.12.6357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kudwa AE, Bodo C, Gustafsson JA, Rissman EF. A previously uncharacterized role for estrogen receptor beta: defeminization of male brain and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4608–4612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500752102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kudwa AE, Rissman EF. Double oestrogen receptor alpha and beta knockout mice reveal differences in neural oestrogen-mediated progestin receptor induction and female sexual behaviour. J Neuroendocrinol. 2003;15:978–983. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kudwa AE, Michopoulos V, Gatewood JD, Rissman EF. Roles of estrogen receptors alpha and beta in differentiation of mouse sexual behavior. Neuroscience. 2006;138:921–928. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Temple JL, Fugger HN, Li X, Shetty SJ, Gustafsson J, Rissman EF. Estrogen receptor beta regulates sexually dimorphic neural responses to estradiol. Endocrinology. 2001;142:510–513. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.1.8054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Weihua Z, Lathe R, Warner M, Gustafsson JA. An endocrine pathway in the prostate, ERbeta, AR, 5alpha-androstane-3beta, 17beta-diol, and CYP7B1, regulates prostate growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13589–13594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162477299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Oliveira AG, Coelho PH, Guedes FD, Mahecha GA, Hess RA, Oliveira CA. 5alpha-Androstane-3beta, 17beta-diol (3beta-diol), an estrogenic metabolite of 5alpha dihydrotestosterone, is a potent modulator of estrogen receptor ERbeta expression in the ventral prostrate of adult rats. Steroids. 2007;72:914–922. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lund TD, Rovis T, Chung WC, Handa RJ. Novel actions of estrogen receptor- beta on anxiety-related behaviors. Endocrinology. 2005;146:797– 807. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Imwalle DB, Gustafsson J-Å, Rissman EF. Lack of functional estrogen receptor β influences anxiety behavior and serotonin content in female mice. Physiol Behav. 2005;84:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Aikey JL, Nyby JG, Anmuth DM, James PJ. Testosterone rapidly reduces anxiety in male house mice (Mus musculus) Horm Behav. 2002;42:448–460. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2002.1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Patisaul HB, Melby M, Whitten PL, Young LJ. Genistein affects ER betabut not ER alpha-dependent gene expression in the hypothalamus. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2189–2197. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.6.8843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Patisaul HB. Phytoestrogen action in the adult and developing brain. J Neuroendocrinol. 2005;17:57–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2005.01268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Strom BL, Schinnar R, Ziegler EE, Barnhart KT, Sammel MD, Macones GA, Stallings VA, Drulis JM, Nelson SE, Hanson SA. Exposure to soy-based formula in infancy and endocrinological and reproductive outcomes in young adulthood. JAMA. 2001;286:807–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.7.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Patisaul HB, Bateman HL. Neonatal exposure to endocrine active compounds or an ERbeta agonist increases adult anxiety and aggression in gonadally intact male rats. Horm Behav. 2008;53:580–588. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]