Abstract

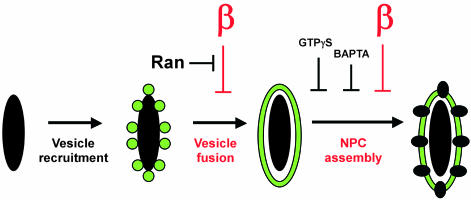

Assembly of a eukaryotic nucleus involves three distinct events: membrane recruitment, fusion to form a double nuclear membrane, and nuclear pore complex (NPC) assembly. We report that importin β negatively regulates two of these events, membrane fusion and NPC assembly. When excess importin β is added to a full Xenopus nuclear reconstitution reaction, vesicles are recruited to chromatin but their fusion is blocked. The importin β down-regulation of membrane fusion is Ran-GTP reversible. Indeed, excess RanGTP (RanQ69L) alone stimulates excessive membrane fusion, leading to intranuclear membrane tubules and cytoplasmic annulate lamellae-like structures. We propose that a precise balance of importin β to Ran is required to create a correct double nuclear membrane and simultaneously to repress undesirable fusion events. Interestingly, truncated importin β 45–462 allows membrane fusion but produces nuclei lacking any NPCs. This reveals distinct importin β-regulation of NPC assembly. Excess full-length importin β and β 45–462 act similarly when added to prefused nuclear intermediates, i.e., both block NPC assembly. The importin β NPC block, which maps downstream of GTPγS and BAPTA-sensitive steps in NPC assembly, is reversible by cytosol. Remarkably, it is not reversible by 25 μM RanGTP, a concentration that easily reverses fusion inhibition. This report, using a full reconstitution system and natural chromatin substrates, significantly expands the repertoire of importin β. Its roles now encompass negative regulation of two of the major events of nuclear assembly: membrane fusion and NPC assembly.

INTRODUCTION

In cells from yeast to mammals, importin α and β act together to ferry classical nuclear localization signal (NLS)-bearing proteins into the nucleus (Gorlich and Kutay, 1999; Stoffler et al., 1999; Damelin and Silver, 2000; Rout et al., 2000; Conti and Izaurralde, 2001; Vasu and Forbes, 2001; Damelin et al., 2002; Weis, 2003). Once in the nucleus the small GTPase Ran binds to importin β, displacing importin α and the NLS cargo, thus completing import. In the nucleus, Ran is kept in a GTP state by the constant action of its chromatinbound Ran-GEF, RCC1 (Melchior and Gerace, 1998; Macara, 2001; Dasso, 2002; Kalab et al., 2002; Schwoebel et al., 2002; Steggerda and Paschal, 2002). In contrast, RanGDP is the predominant form found in the cytoplasm due to the cytoplasmic localization of RanGAP.

The horizons for importin α and β were unexpectedly broadened when they were found to play a very different role at mitosis. In metazoans, importin α and β are released to the cytosol by nuclear breakdown, where they act to inhibit proteins essential for mitotic spindle assembly. However, the inhibition of spindle assembly is reversed by Ran in the vicinity of mitotic chromosomes, where RanGTP continues to be produced by chromatin-bound RCC1 (Kalab et al., 1999; Gruss et al., 2001; Nachury et al., 2001; Wiese et al., 2001; Dasso, 2002). Thus, a spindle forms only around the mitotic (ER) chromosomes and not elsewhere in the cytoplasm.

At the end of mitosis, in vivo membranes are recruited to the chromatin, likely in the form of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) sheets, and fuse side to side to encompass the DNA with an intact double nuclear membrane (Ellenberg et al., 1997; Yang et al., 1997). It has been shown in vitro that nuclei assemble spontaneously in Xenopus egg extracts: a double nuclear membrane with nuclear pores forms around added chromatin, whether natural sperm chromatin substrate or exogenously added prokaryotic DNA is used (Forbes et al., 1983; Lohka and Masui, 1984; Blow and Laskey, 1986; Newport, 1987; Bauer et al., 1994; Powers et al., 1995; Ullman and Forbes, 1995; Macaulay and Forbes, 1996; Goldberg et al., 1997; Hetzer et al., 2001). In the in vitro situation, nuclear membrane/endoplasmic reticulum-derived vesicles are the source of the future nuclear membrane. Interestingly, the assembly of the nuclear membranes in Xenopus extracts is promoted by RanGTP (Zhang and Clarke, 2000; Hetzer et al., 2000). In this robust in vitro system, even Sepharose beads coated with DNA or Ran recruit membrane vesicles and form nuclear membranes with functional nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) (Heald et al., 1996; Zhang and Clarke, 2000). The subsequent finding that importin β-coated beads could form a nuclear envelope led to the suggestion that importin β positively regulates nuclear assembly in vivo by recruiting membrane vesicles to chromatin through its ability to bind RanGTP on the chromatin and unknown FG nucleoporins (nucleoporins possessing FXFG repeats; FG Nups) on membranes (Zhang et al., 2002b; for review, see Dasso, 2002). Although the way in which this would be accomplished is unclear, since importin β in vitro binds either RanGTP or FG nucleoporins, but not both (Bayliss et al., 2000a,b; Ben-Efraim and Gerace, 2001; Allen et al., 2002), the study raised the interesting possibility that importin β could be involved in regulating nuclear assembly.

In vivo experiments involving mutant importin β in Drosophila embryos or interference RNA-targeted destruction of importin α, β, and Ran in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos have also suggested that these proteins could act at some step in nuclear envelope assembly, although the multifaceted in vivo phenotypes complicate the interpretation (Askjaer et al., 2002; Geles et al., 2002; Timinszky et al., 2002). Herein, we have determined, using natural chromatin substrates and probing individual intermediates in nuclear assembly, that importin β negatively regulates 1) the fusion events required to form a double nuclear membrane, and 2) nuclear pore complex assembly into fused nuclear membranes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Nuclear Reconstitution and Immunofluorescence

Xenopus egg extracts and the membrane vesicle and cytosolic fractions thereof were prepared as in Harel et al. (2003). Full-length human importin α, importin β, and importin β 45–462 (Kutay et al., 1997) were expressed in bacteria, purified on Ni2+-NTA resin (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA), dialyzed into 5%glycerol/phosphate-buffered saline, and concentrated using Ultrafree-4 microconcentrators (Millipore, Bedford, MA) before use. RanQ69L in pET28A was expressed, purified, and loaded with GTP essentially as described in Kutay et al. (1997).

Nuclei were reconstituted by mixing Xenopus egg membrane vesicle and cytosolic fractions at a 1:20 ratio with an ATP-regeneration system and sperm chromatin (Macaulay and Forbes, 1996). Protein addition was generally kept to 10% (vol/vol), with the equivalent buffer (5% glycerol/phospate-buffered saline) serving as a control. To accommodate 20 μM importin β plus 25 μM RanQ69L, the total volume addition was raised to 30% β+Ran or 30% buffer. For every expressed protein, the filtrate from its microconcentration was tested in parallel and found to have no effect on nuclear assembly. Importin α had no deleterious effects when tested up to 30 μM. Additional control proteins tested at 20–150 μM included: ovalbumin, bovine serum albumin, green fluorescent protein, glutathione S-transferase, GST-Tet repressor, 6-His-NLS-β-galactosidase, 6-His-zz tag control fragment (Vasu et al., 2001), hNup153 aa 1–335 (Vasu et al., 2001), and rNup98 aa 470–824 (Vasu et al., 2001). To assay for the presence of nuclear pores and nuclear import, directly labeled Oregon Green-mAb414 antibody (Covance, Berkeley, CA; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR; labeled as in Harel et al., 2003), and TRITC-SV40 NLS-HSA transport substrate were added to reconstituted nuclei 60 min after the start of assembly and fixed 30–60 min later in 3% paraformaldehyde. Nuclear membrane formation was assayed by the ability to exclude tetramethylrhodamine B isothiocyanate (TRITC)-150-kDa dextran or fluorescein isothiocyanate-18-kDa dextran (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) after fixation and by continuous rim staining with the lipophilic dye 3,3-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide (DHCC) (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). Nuclei were visualized with an Axioskop 2 microscope (63× objective; Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY).

Ordering of Nuclear Assembly Intermediates

Importin β 45–462-inhibited nuclear intermediates were formed by the addition of 5 μM importin β 45–462 to a nuclear reconstitution reaction at t = 0. After 60 min, the reaction containing importin β 45–462–inhibited nuclei was diluted 1:10 into Xenopus egg cytosol or egg cytosol containing 5 mM 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA) (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA). The reactions were incubated for an additional 45 min, after which Oregon Green mAb414 was added to assay for FG nucleoporin incorporation.

BAPTA-inhibited, membrane-enclosed nuclear intermediates were formed by the inclusion of 5 mM BAPTA at the start of a nuclear reconstitution reaction (Macaulay and Forbes, 1996). The BAPTA block was released by dilution of 1 volume of the nuclear intermediate reaction into nine volumes of a 1:1 mixture of cytosol and importin β, importin β 45–462, RanQ69L-GTP, or buffer. After 45 min of incubation, nuclei were assayed for presence of nuclear pores with Oregon Green-mAb414.

Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM)

Control and importin β 45–462–inhibited nuclei were assembled for 60 min as described above and then prepared essentially as described in Walther et al. (2002) and references therein. Samples were critical point dried from ultra-dry CO2 (CPD 030; Bal-Tec, Balzers, Switzerland), sputter coated with 3.4-nm chromium (EMITECH K575 ×), and examined using a Philips field emission scanning electron microscope (XL30 ESEM FEG).

RESULTS

Importin β Negatively Regulates Nuclear Membrane Fusion

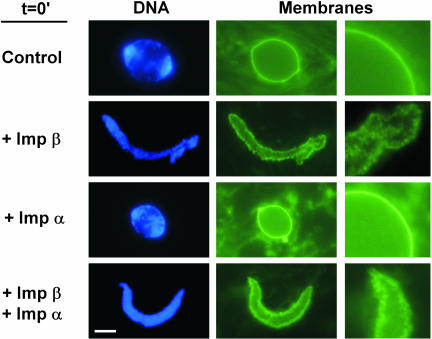

Importin β regulates nuclear import in interphase and spindle assembly in metaphase. To ask whether importin β might act as a global regulator of events throughout the cell cycle, we used a nuclear assembly system derived from Xenopus egg extracts. In this system, robust assembly of functional nuclei occurs around added chromatin templates. We reasoned that disturbing the balance of importin β in the extract could reveal the step(s) at which such regulation might take place. Recombinant importin β was added to a reconstitution reaction consisting of cytosol, membrane vesicles, and natural chromatin substrate. Normally, importin β is present at ∼3 μM concentration in Xenopus cytosol (Kutay et al., 1997). In control reactions (Figure 1, control) or reactions to which excess importin α (Figure 1, +Imp α; 15 μM) or nine unrelated soluble proteins were added (our unpublished data; see MATERIALS AND METHODS), nuclei assembled normally. When recombinant importin β was added at 5 μM, membrane vesicles were also recruited to chromatin and fused to form nuclear membranes (our unpublished data). When, however, importin β was added at 15–25 μM, membrane vesicles were recruited to the chromatin in abundance, but failed to fuse (Figure 1, + Imp β). The chromatin surfaces showed a discontinuous stain with the membrane dye DHCC, characteristic of unfused vesicles. Indeed, excess importin β completely blocked nuclear membrane fusion in a manner indistinguishable from the chemical fusion inhibitors GTPγS (a nonhydrolysable analog of GTP) or NEM (N-ethyl maleimide) (Macaulay and Forbes, 1996; Hetzer et al., 2000).

Figure 1.

Excess importin β blocks nuclear membrane fusion. Nuclear reconstitution reactions were set up and supplemented at t = 0 with buffer (control), importin β (Imp β), importin α (Imp α), or importin β plus importin α (Imp β + Imp α). Protein additions were at 15 μM. The formation of nuclear membranes was assessed at 1 h with the fluorescent membrane dye DHCC (green). Bar, 10 μm. The enlargements at the right are magnified 3×.

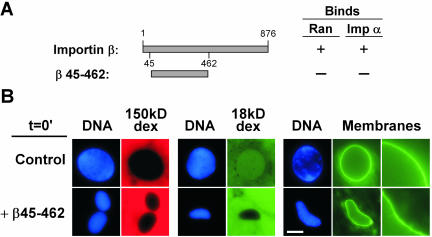

In previous studies, a truncated form of importin β (aa 45–462) acted as a powerful dominant negative inhibitor of nuclear transport (Kutay et al., 1997). This form of importin β contains the central or nucleoporin-binding domain, but lacks the Ran- and importin α-binding domains (Figure 2A). When importin β 45–462 was added to the nuclear assembly reaction at t = 0, we found it had no effect on nuclear membrane fusion even at concentrations up to 40 μM (Figure 2B). Complete nuclear membranes formed, as was clear from the sharp continuous DHCC rim stain characteristic of fused nuclear membranes and from the ability to exclude both 150-kDa and 18-kDa dextran (Figure 2B). Thus, excess full-length importin β blocks nuclear vesicle fusion, but the truncated β 45–462 form does not.

Figure 2.

Importin β 45–462 does not block nuclear membrane fusion. (A) Binding characteristics of importin β and importin β 45–462 (Kutay et al., 1997). (B) Importin β 45–462 does not block nuclear membrane assembly. Importin β 45–462 (β 45–462; 15 μM) or buffer (control) were added at t = 0 to nuclear reconstitution reactions. After 1 h, the integrity of the nuclear envelope was determined by assaying exclusion of TRITC-150-kDa dextran, fluorescein isothiocyanate-18-kDa dextran, and continuous DHCC stain of the nuclear membrane. Bar, 10 μm. The enlargements at right are magnified 3×.

Importin β Acts on Membrane Fusion through Ran

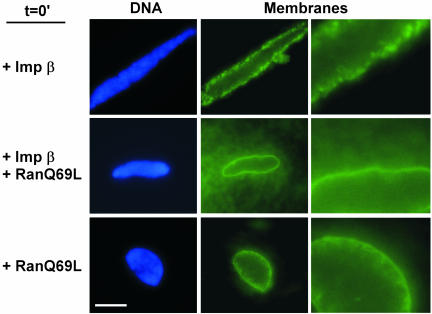

The above-mentioned result implied that for full-length importin β, either its importin α-binding domain or its Ran-binding domain could be involved in the strong block to membrane fusion. Addition of increasing amounts of importin α did not, however, reverse importin β's inhibitory effect (Figure 1, Imp β + Imp α). We asked whether the fusion defect could be reversed by Ran. RanQ69L, a mutant form unable to hydrolyze GTP, was used because Ran-GTP is the form that normally reverses importin β action within the cell (Kutay et al., 1997; Macara, 2001; Dasso, 2002). When excess RanQ69L (25 μM; preloaded with GTP) was added together with full-length importin β (20 μM), membrane fusion now occurred (Figure 3). RanQ69L alone did not block membrane fusion at this high concentration (Figure 3). Indeed, RanQ69L stimulated excess membrane fusion in the form of intranuclear membrane tubules (Figure 3). These results argue that importin β negatively regulates nuclear membrane fusion. It seems to do so, not by interacting with nucleoporins, because the importin β 45–462 form clearly does not block membrane fusion, but through an interplay with RanGTP itself.

Figure 3.

RanGTP reverses the importin β block to membrane fusion. Nuclear reconstitution reactions were set up at t = 0 with full-length importin β (20 μM), RanQ69L (25 μM), or both full-length importin β (20 μM) and RanQ69L (25 μM). After 1-h incubation, nuclear membranes were visualized with DHCC. Bar, 10 μm. The enlargements at right are magnified 3×.

Importin β Negatively Regulates NPC Assembly

We turned next to potential regulation of downstream assembly events. Addition of truncated importin β 45–462 does not prevent fusion to form a double nuclear membrane, but the resulting nuclei are small and defective for nuclear import (Figure 4, import). This could result either from a simple inhibition of nuclear import through assembled pores, or from a more severe defect in the NPCs themselves. The exclusion of 18-kDa dextran by such nuclei (Figure 2B) implied the latter might indeed be the case. To test this, the presence of nuclear pore complexes was analyzed using Oregon Green mAb414 antibody, which recognizes FG nucleoporins (Wente et al., 1992). This antibody gave a strong punctate nuclear rim on control nuclei (Figure 4). Remarkably, no mAb414 signal was observed on importin β 45–462–treated nuclei (Figure 4), indicating no accessible FG nucleoporins are present. A full block of mAb414 staining was consistently seen when 5–10 μM importin β 45–462 was added. This suggested that importin β 45–462 causes a defect in NPC assembly itself.

Figure 4.

Importin β 45–462 blocks NPC assembly. Importin β 45–462 (5 μM) or buffer (control) were added at t = 0 to nuclear reconstitution reactions. Import was assayed with TRITC-SV40 NLS-HSA and FG nucleoporins were detected with Oregon Green mAb414 antibody. Bar, 10 μm.

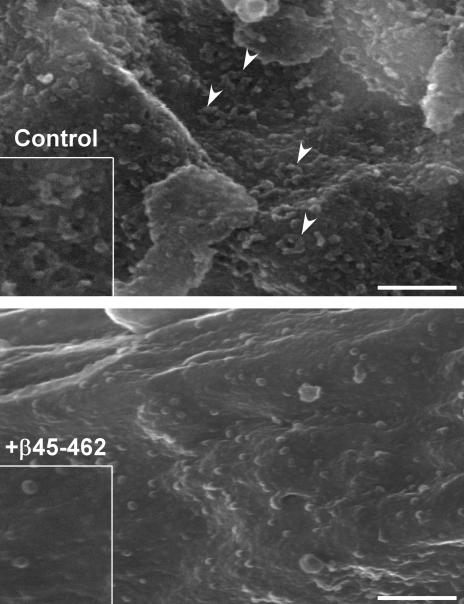

Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) is a high-resolution and sensitive probe for the presence of nuclear pore complexes and their intermediates (Goldberg et al., 1997; Walther et al., 2002). FESEM was used to analyze importin β 45–462–arrested nuclei and indicated that these membrane-enclosed nuclei lack any external sign of NPC structure (Figure 5). Thus, importin β 45–462 blocks NPC assembly at or near its inception.

Figure 5.

Importin β 45–462–arrested nuclei lack NPCs. Typical views of control nuclei and 10 μM importin β 45–462–arrested nuclei are shown, as visualized with FESEM. Sample nuclear pore complexes are highlighted with arrowheads. Smaller single granules remaining on the nuclear surface in the lower panel are ribosomes (Goldberg et al., 1997). Insets are 1.6× higher magnification. Bars, 250 nm.

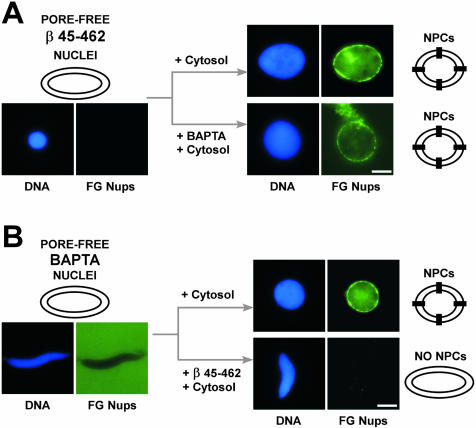

To test whether the NPC block is reversible, importin β 45–462–arrested nuclei were diluted into fresh cytosol for 45 min and then mixed with Oregon Green-labeled mAb414 to probe for the presence of NPCs. The nuclei were found to contain abundant NPCs, indicating reversal of the defect (Figure 6A). Rescue allowed us to attempt to order the importin β 45–462 block with respect to previously identified chemical inhibitors. Three early steps in nuclear envelope assembly were defined by chemical inhibitors (Boman et al., 1992; Macaulay and Forbes, 1996). GTPγS blocks at two points: at membrane-membrane vesicle fusion and at a very early step in NPC assembly (Boman et al., 1992; Macaulay and Forbes, 1996; Hetzer et al., 2000). BAPTA, a Ca2+ chelator, blocks slightly downstream from this second GTPγS-sensitive step of NPC assembly (Macaulay and Forbes, 1996). BAPTA allows membrane enclosure but prevents any connection between inner and outer nuclear membranes to form an NPC (Macaulay and Forbes, 1996). When importin β 45–462–arrested nuclear intermediates were diluted into cytosol plus GTPγS (our unpublished data) or cytosol plus BAPTA (Figure 6A), nuclear pores formed. This indicates that importin β 45–462 acts downstream from BAPTA to regulate NPC assembly. For the converse experiment, BAPTA-arrested pore-free nuclei were diluted 1:10 into cytosol plus or minus importin β 45–462. The BAPTA block was rescued by fresh cytosol, but no NPCs were formed when importin β 45–462 was included (Figure 6B). These experiments demonstrate a novel importin β 45–462-sensitive step in nuclear pore assembly.

Figure 6.

Importin β 45–462 blocks NPC assembly after the BAPTA inhibition step. (A) Importin β 45–462–arrested nuclei were formed by adding 5 μM importin β 45–462 to a nuclear reconstitution reaction at t = 0. After 60 min, the arrested nuclei did not stain with Oregon Green mAb414 (pore-free β 45–462 nuclei; left). To assess rescue and order the β 45–462 block with respect to BAPTA, the importin β 45–462–arrested nuclei were diluted 1:10 into egg cytosol (cytosol) or egg cytosol with 5 mM BAPTA (cytosol + BAPTA), followed by incubation for 45 min. FG nucleoporins incorporated (FG Nups; NPCs) in both types of nuclei, as shown by the punctate nuclear rim staining with Oregon Green mAb414. (B) BAPTA-arrested nuclei were assembled by adding 5 mM BAPTA at t = 0 to a nuclear reconstitution reaction. After 60 min, Oregon Green mAb414 did not stain the nuclear intermediates and was excluded, indicative of a sealed nuclear membrane, as shown in an overexposed image (left). To order the BAPTA- and β 45–462–inhibited steps, reactions containing pore-free BAPTA-arrested nuclei were diluted 1:10 into egg cytosol plus or minus 5 μM importin β 45–462 and incubated for 45 min. Importin β 45–462 prevented FG nucleoporins from incorporating into BAPTA nuclei, as seen by lack of Oregon Green mAb414 staining (NO NPCs). Thus, the β 45–462 block to NPC assembly occurs after the BAPTA block. Bars, 10 μm.

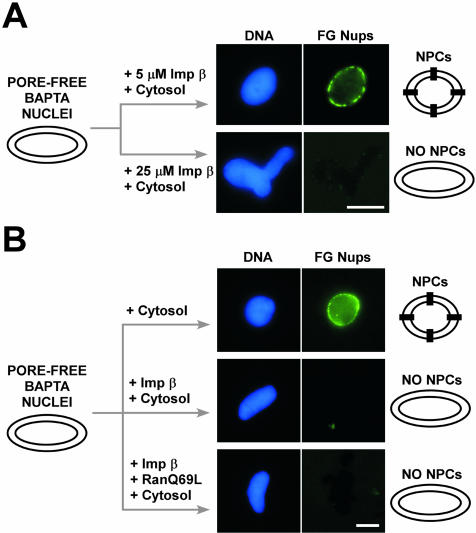

The ability to form membrane-enclosed pore-free nuclear intermediates with BAPTA allowed us to ask whether full-length importin β itself plays a regulatory role in NPC assembly. Low concentrations of importin β (5 μM) did not interfere with the ability of cytosol to rescue NPC assembly in BAPTA-blocked nuclei (Figure 7A). However, higher concentrations of importin β (15–25 μM) completely blocked NPC assembly in these prefused nuclear intermediates (Figure 7A). We asked whether an excess of RanGTP could reverse importin β's inhibitory action on NPC assembly. Most surprisingly, RanQ69L (25 μM) was completely unable to reverse the block (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Excess full-length importin β blocks NPC assembly. (A) Excess full-length importin β also blocks NPC assembly. Membrane-enclosed, pore-free nuclear intermediates were first formed in a nuclear reconstitution reaction containing 5 mM BAPTA. After 1 h, the pore-free BAPTA nuclei were diluted 1:10 into cytosol containing 5 μM full-length importin β or 25 μM full-length importin β and incubated for 45 min. The presence of 25 μM full-length importin β clearly prevented FG nucleoporin incorporation, as assayed with Oregon Green-mAb414. (B) RanQ69L at 25 μM does not reverse the full-length importin β block of NPC assembly into fused nuclear membranes. Pore-free BAPTA nuclei, formed as in A for 1 h, were diluted 1:10 into cytosol, cytosol with full-length importin β (15 μM), or cytosol with full-length importin β (15 μM) plus RanQ69L (25 μM). FG nucleoporins did not incorporate even when 25 μM RanQ69L was included with importin β, as assayed with Oregon Green-mAb414, i.e., the rescue of NPC assembly was prevented if importin β or importin β + RanQ69L were present. Bars, 10 μm.

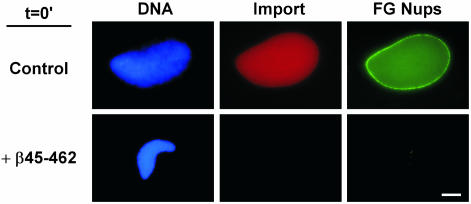

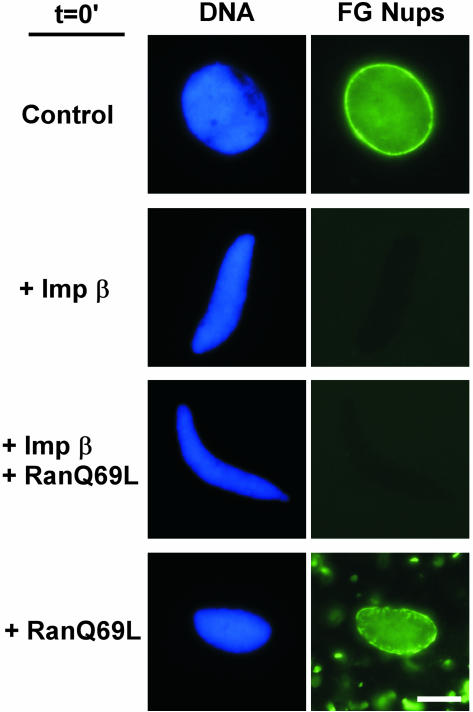

Together, our results indicate that importin β acts at two distinct steps in nuclear assembly. In light of this, we would predict that when excess importin β and RanQ69L are present in a reconstitution reaction from t = 0 (as in Figure 3), the block to membrane fusion would be relieved by RanQ69L but the block to NPC assembly would not. Indeed, when we performed this experiment, the resulting nuclei contained fused membranes (Figure 3, +Imp β +RanQ69L) but did not stain with FG antibodies (Figure 8, +Imp β+RanQ69L), indicating no NPCs were formed. RanQ69L alone did not prevent NPC assembly (Figure 8, +RanQ69L). Interestingly, RanQ69L induced the assembly of additional structures outside the nucleus that stain with anti-FG antibody. Importin β suppressed the FG-staining extranuclear structures (Figure 8, +Imp β+RanQ69L), presumably the well-characterized cytoplasmic stacks of NPC-containing membranes, termed annulate lamellae (Dabauvalle et al., 1991; Miller and Forbes, 2000, and references therein). Overall, the data demonstrate that importin β blocks the insertion of NPCs into fused nuclear membranes and suggest that the reversal of this blocked step is different than the fusion step.

Figure 8.

RanQ69L reverses the full-length importin β block to membrane fusion, but not the block to NPC assembly. Nuclear reconstitution reactions containing chromatin, cytosol, and membranes were supplemented at t = 0 with 30% volume buffer, full-length importin β (20 μM), full-length importin β (20 μM) plus RanQ69L (25 μM), or RanQ69L (25 μM) alone. The reactions containing importin β, or importin β plus RanQ69L, failed to incorporate FG nucleoporins as detected with Oregon Green-mAb414. FG nucleoporins incorporated into nuclear envelopes in reactions supplemented with buffer or RanQ69L. The RanQ69L reactions also showed FG-containing structures forming outside of the nucleus, presumed annulate lamellae. Additionally, the nuclei in the RanQ69L reactions contained areas of the nuclear envelope devoid of FG nucleoporin staining. These corresponded to outer nuclear membrane bubbles, which appear as gaps in the mAb414 stain (this figure) or as bubbles when DHCC membrane dye is used (our unpublished data). Bar, 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

Nuclear assembly on natural chromatin substrates in vitro involves: vesicle recruitment to the chromatin, vesicle-vesicle fusion, and NPC insertion into the fused nuclear membranes. We have demonstrated that importin β acts at two of these vital steps: nuclear membrane fusion and the subsequent assembly of nuclear pore complexes. Specifically, excess importin β blocks vesicle-vesicle fusion around natural chromatin substrates. This inhibitory action, like importin β's inhibition of spindle assembly, is reversible by RanGTP. Importin β 45–462, unable to bind Ran, does not block membrane fusion, but interestingly, blocks downstream NPC assembly. This second block occurs near the inception of NPC formation, as shown by FESEM, and results in nuclei lacking any visible NPC structures. Excess full-length importin β also blocks NPC assembly, if added to prefused nuclear intermediates. Remarkably, the full-length importin β block of NPC assembly is not reversible by 25 μM RanQ69L-GTP. The NPC block maps downstream from BAPTA- and GTPγS-sensitive steps in NPC assembly. Our data thus support a new model of stepwise nuclear assembly regulated at multiple points by importin β, as summarized in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

A model of novel importin β-regulated steps in nuclear membrane fusion and NPC assembly. Chromatin is depicted as a large black oblong; vesicles and membranes are shown by black lines enclosing green lumenal contents. NPCs are depicted as black ovals spanning the inner and outer nuclear membranes. Importin β and the importin β-regulated steps observed in this study are shown in red.

One of the first visible steps in nuclear assembly in vitro is the recruitment of membrane vesicles to chromatin. A previous study observed nuclear envelope assembly on importin β-coated beads (Zhang et al., 2002b). This led to the hypothesis that, in vivo, importin β might positively induce membrane recruitment through its ability to bind RanGTP on the chromatin and undetermined FG nucleoporins on the membranes, either simultaneously or sequentially (Zhang et al., 2002b; for review, see Dasso, 2002). A clear expectation of this hypothesis would be that importin β 45–462, which cannot bind RanGTP, should block membrane recruitment. We found no evidence for inhibition of membrane recruitment to natural chromatin substrates by importin β 45–462; fully fused nuclear membranes formed in its presence. Thus, although importin β may be involved in membrane recruitment in some way, our experiments indicate it cannot be playing an exclusive role. Because nuclear lamins and LAPs (lamina-associated polypeptides) are known to mediate interaction between membranes and chromatin (Foisner and Gerace, 1993; Drummond et al., 1999; Gant et al., 1999; Raharjo et al., 2001; Goldman et al., 2002), ample evidence for alternative mechanisms for membrane recruitment exist.

Our data strongly indicate that importin β acts to negatively regulate the vesicle-vesicle fusion step of nuclear assembly. Why would such regulation be required? Ran has previously been shown to promote nuclear membrane fusion, working through an unknown partner (Pu and Dasso, 1997; Hetzer et al., 2000; Zhang and Clarke, 2000, 2001). We show that importin β blocks membrane fusion, thus counteracting Ran. In vivo, we would predict that it is the strict ratio of importin β to RanGTP that ensures fusion in the correct location and proportion. We hypothesize that importin β is needed in vivo to carefully regulate membrane fusion where RanGTP is high, such as at the surface of telophase chromosomes. There, fusion to form the surrounding nuclear membranes is desirable, but undesirable fusion would need to be repressed. Examples of undesirable fusion include fusion that is spatially undesirable such as the formation of intranuclear membrane tubules, and fusion that is proportionately undesirable such as excess growth of the outer nuclear membrane relative to the inner. Interestingly, we find that when high RanQ69L is added alone to an extract, it does indeed promote the appearance of excess intranuclear membranes and outer nuclear membrane bubbles (Figures 3 and 8; our unpublished data), indicating that the normal regulatory balance is disturbed toward fusion. Combining excess importin β and excess RanQ69L not only reverses the importin β block to fusion, but also reverses the RanQ69L stimulation of intranuclear membranes (Figure 3). In this case, correct nuclear membranes form, suggesting the required balance of importin β and RanGTP has been restored.

These conclusions were reinforced when the presence of nuclear pore complexes in nuclei was assessed with anti-FG antibody. When high RanQ69L was added, excess FG-staining NPCs were observed in the nuclear envelope, in intranuclear tubules, and extranuclearly in presumed annulate lamellae. No NPCs were seen if excess importin β was present along with the Ran (Figure 8). Together, our data suggest that a balance of RanGTP to importin β is necessary not only to promote a correctly positioned nuclear envelope but also to repress intranuclear and cytoplasmic annulate lamellae.

Our experiments were conducted in a full nuclear assembly reaction, using abundant membranes and natural chromatin substrates, a situation that most closely approximates the in vivo situation. Other cases where individual proteins are immobilized on beads, or chromatin is incubated in limiting membranes, may not necessarily recapitulate the correct steps of nuclear assembly. For example, in previous experiments where membranes were very limiting or chemically modified, RanQ69L reportedly blocked membrane fusion (Hetzer et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2002a). Perhaps these experiments, while not mimicking in vivo conditions, nevertheless reveal that the ratio of Ran to an essential membrane protein is important. In the opposite vein, overexpression of certain nucleoporins in vivo can cause excess intranuclear membrane tubules (Bodoor et al., 1999; Marelli et al., 2001; Burke and Ellenberg, 2002; Lusk et al., 2002). This suggests that the relative concentrations of key nucleoporins ultimately should not be left out of the picture.

A second and distinct step of importin β negative regulation was unexpectedly revealed: control of NPC assembly (Figure 9). This step is blocked both by excess importin β and by importin β 45–462. Surprisingly, although the NPC inhibition can be rescued by fresh cytosol, it is not reversible by RanQ69L (25 μM). This is in marked contrast to the membrane fusion step, which is Ran-reversible at 25 μM. Although the possibility remains that an unusually high RanQ69L concentration might be required to reverse NPC assembly inhibition, experiments where high importin β and high RanQ69L are added together at t = 0 show membrane fusion, but no trace of NPC formation (Figures 3 and 8). At the very least, this result indicates that we are not near the threshold of any potential Ran reversibility.

Importin β is known to bind to a subset of vertebrate FG nucleoporins: Nup358, Nup153, Nup62, as well as the NPC-associated protein Tpr. However, these interactions are all disrupted by high Ran-GTP or GMP-PNP (Shah et al., 1998; Bayliss et al., 2000a,b; Ben-Efraim and Gerace, 2001; Conti and Izaurralde, 2001; Allen et al., 2002). Because of the relative insensitivity to RanQ69L described above and the fact that none of the FG Nups are essential for NPC assembly (Finlay and Forbes, 1990; Meier et al., 1995; Walther et al., 2001, 2002), importin β cannot be blocking NPC assembly simply by sequestering free FG nucleoporins.

This suggests that importin β must instead regulate either an essential nucleoporin or unknown NPC assembly factor. An attractive target is the Nup107–160 complex, because nuclei assembled in the absence of this complex lack nuclear pores (Harel et al., 2003; Walther et al., 2003; see also Boehmer et al., 2003). Other possibilities include gp210, an integral membrane protein involved in pore assembly (Drummond and Wilson, 2002), and nucleoporins not yet characterized for roles in NPC assembly, such as Nup155 or the WD repeat Nups (Cronshaw et al., 2002). We are currently investigating these and other potential targets.

Importin β likely binds to many nucleoporins in the mature NPC during transport. It may be that importin β plays dual roles with respect to these nucleoporins, binding to them in interphase NPCs during transport, but in mitosis acting to keep the same Nups in a disassembled state. The story could also have additional layers, in the sense that not all Nups that are blocked by importin β need be regulated in the same manner. Certain Nups, such as the FG Nups, might be bound by importin β and prevented from assembly, but the binding be easily reversible by Ran-GTP. Other Nups could bind importin β and be similarly blocked for NPC assembly, but either require much more Ran-GTP, or require a completely different regulatory protein for reversal of their importin β block. There are multiple examples of Ran independence in nuclear transport, including the import of snRNPs, ribosomal protein L5, and cyclin B1 (Takizawa et al., 1999; Rudt and Pieler, 2001; Huber et al., 2002), and the export of mRNA (Clouse et al., 2001). This independence of transport opens the possibility that there could be a similar Ran-independence in some of importin β 's inhibitory interactions of NPC assembly.

Evidence for a Ran-sensitive step in NPC assembly was recently found in yeast (Ryan et al., 2003). Certain mutant alleles of Ran cycle enzymes disrupt NPC assembly. This Ran-sensitive step in yeast was suggested to correspond to the GTPγS-sensitive step of NPC assembly in vertebrates (Figure 9). We have mapped importin β regulation of NPC assembly downstream from the GTPγS- and BAPTA-inhibited steps. Together, these results indicate that there may well be multiple control points for regulating NPC assembly.

In vertebrates, NPCs assemble at two different stages of the cell cycle: at telophase in newly forming nuclear envelopes, and at S phase in existing nuclear envelopes. We have used templates corresponding to both phases and find that importin β regulates NPC assembly in each. When one starts with telophase-like sperm chromatin substrates, importin β 45–462 allows membrane fusion, but clearly blocks NPC assembly. When prefused nuclear membrane intermediates, which resemble S phase nuclei, are formed and importin β or β45–462 is added, NPC assembly is blocked. This result demonstrates that importin β acts after membrane fusion to regulate a vital step required for NPC assembly. At concentrations up to 25 μM, the highest we were able to achieve, this importin β block is not sensitive to RanGTP. There is an inherent logic to this apparent Ran insensitivity, insensitivity: normally the major source of Ran-GTP, chromatinbound RCC1, is shielded once the chromatin becomes membrane enclosed.

In vivo a small subset of nucleoporins show affinity for the surface of mammalian mitotic chromosomes, either for kinetochores (Belgareh et al., 2001; Harel et al., 2003) or for the surface of telophase chromosomes (Bodoor et al., 1999; Haraguchi et al., 2000; Daigle et al., 2001). With this in mind, it was recently proposed that NPC assembly might occur very differently on telophase chromosomes than it is known to occur in yeast, in vertebrate S phase nuclei, or in annulate lamellae. This inverse order assembly model (Walther et al., 2003) proposed that soluble nucleoporins bind to the surface of chromosomes, recruit other nucleoporins into pre-NPCs, and attract membranes only at the end of the NPC assembly process. The model was based on observation of punctate Nup staining on sperm chromatin that had been incubated in Xenopus cytosol thought to be devoid of membranes. However, in our hands and those of others, it is not possible to completely remove membranes from egg cytosol by high-speed centrifugation (200,000 × g). Indeed, Allen and colleagues have studied nuclear membrane and NPC assembly by FESEM in reactions performed entirely in cytosol (HSS, high-speed supernatant), clearly demonstrating that significant quantities of membranes are present (Zhang et al., 2002a). Thus, the immunofluorescent Nup staining on chromatin (Walther et al., 2003) likely coincides with NPCs that have formed in fused membrane patches in the typical NPC assembly process. We advocate a unified model for NPC assembly relevant to all stages of the cell cycle in yeast and vertebrates, with NPC assembly initiating only in fused nuclear membranes (Macaulay and Forbes, 1996; this work). Our use of telophase-like and S phase-like templates demonstrates that importin β regulates NPC assembly in both.

In summary, we have shown using natural chromatin substrates that importin β negatively regulates two distinct steps in nuclear assembly: the vesicle-vesicle fusion required to form double nuclear membranes and the assembly of nuclear pore complexes into fused nuclear membranes.

Note added in proof. Following acceptance of this work, Walther et al. (2003) reported related results on the NPC assembly step in a study entitled “RanGTP mediates nuclear pore complex assembly” (Nature 424, 689–694).

Acknowledgments

This work is dedicated to the late Dr. Ira Herskowitz, an excellent scientist, mentor, and friend. We thank D. Gorlich for the importin β, importin β 45–462, and importin α clones. We also thank Art Orjalo, Valerie Delmar, Wendell Smith, Tony Nguyen, and Margaux Aviguetero for technical help and stimulating discussions. This work was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM-33279) to D.F. and a United States-Israel Binational Science Foundation grant to M.E. and D.F.

References

- Allen, N.P., Patel, S.S., Huang, L., Chalkley, R.J., Burlingame, A., Lutzmann, M., Hurt, E.C., and Rexach, M. (2002). Deciphering networks of protein interactions at the nuclear pore complex. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 1, 930-946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askjaer, P., Galy, V., Hannak, E., and Mattaj, I.W. (2002). Ran GTPase cycle and importins alpha and beta are essential for spindle formation and nuclear envelope assembly in living Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 4355-4370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, D.W., Murphy, C., Wu, Z., Wu, C.H., and Gall, J.G. (1994). In vitro assembly of coiled bodies in Xenopus egg extract. Mol. Biol. Cell 5, 633-644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss, R., Corbett, A.H., and Stewart, M. (2000a). The molecular mechanism of transport of macromolecules through nuclear pore complexes. Traffic 1, 448-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss, R., Littlewood, T., and Stewart, M. (2000b). Structural basis for the interaction between FxFG nucleoporin repeats and importin-beta in nuclear trafficking. Cell 102, 99-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belgareh, N., et al. (2001). An evolutionarily conserved nuclear pore subcomplex, which redistributes in part to kinetochores in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 152, 1147-1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Efraim, I., and Gerace, L. (2001). Gradient of increasing affinity of importin beta for nucleoporins along the pathway of nuclear import. J. Cell Biol. 152, 411-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blow, J.J., and Laskey, R.A. (1986). Initiation of DNA replication in nuclei and purified DNA by a cell-free extract of Xenopus eggs. Cell 47, 577-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodoor, K., Shaikh, S., Salina, D., Raharjo, W.H., Bastos, R., Lohka, M., and Burke, B. (1999). Sequential recruitment of NPC proteins to the nuclear periphery at the end of mitosis. J. Cell Sci. 112, 2253-2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehmer, T., Enninga, J., Dales, S., Blobel, G., and Zhong, H. (2003). Depletion of a single nucleoporin, Nup107, prevents the assembly of a subset of nucleoporins into the nuclear pore complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 981-985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boman, A.L., Delannoy, M, R., and Wilson, K.L. (1992). GTP hydrolysis is required for vesicle fusion during nuclear envelope assembly in vitro. J. Cell Biol. 116, 281-294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke, B., and Ellenberg, J. (2002). Remodeling the walls of the nucleus. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 3, 487-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouse, K.N., Luo, M.J., Zhou, Z., and Reed, R. (2001). A Ran-independent pathway for export of spliced mRNA. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 97-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti, E., and Izaurralde, E. (2001). Nucleocytoplasmic transport enters the atomic age. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13, 310-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronshaw, J.M., Krutchinsky, A.N., Zhang, W., Chait, B.T., and Matunis, M.J. (2002). Proteomic analysis of the mammalian nuclear pore complex. J. Cell Biol. 158, 915-927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabauvalle, M.C., Loos, K., Merkert, H., and Scheer, U. (1991). Spontaneous assembly of pore complex-containing membranes (“annulate lamellae”) in Xenopus egg extract in the absence of chromatin. J. Cell Biol. 112, 1073-1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daigle, N., Beaudouin, J., Hartnell, L., Imreh, G., Hallberg, E., Lippincott-Schwartz, J., and Ellenberg, J. (2001). Nuclear pore complexes form immobile networks and have a very low turnover in live mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 154, 71-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damelin, M., and Silver, P.A. (2000). Mapping interactions between nuclear transport factors in living cells reveals pathways through the nuclear pore complex. Mol. Cell 5, 133-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damelin, M., Silver, P.A., and Corbett, A.H. (2002). Nuclear protein transport. Methods Enzymol. 351, 587-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasso, M. (2002). The Ran GTPase: theme and variations. Curr. Biol. 12, R502-R508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond, S., Ferrigno, P., Lyon, C., Murphy, J., Goldberg, M., Allen, T., Smythe, C., and Hutchison, C.J. (1999). Temporal differences in the appearance of NEP-B78 and an LBR-like protein during Xenopus nuclear envelope reassembly reflect the ordered recruitment of functionally discrete vesicle types. J. Cell Biol. 144, 225-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond, S.P., and Wilson, K.L. (2002). Interference with the cytoplasmic tail of gp210 disrupts “close apposition” of nuclear membranes and blocks nuclear pore dilation. J. Cell Biol. 158, 53-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellenberg, J., Siggia, E.D., Moreira, J.E., Smith, C.L., Presley, J.F., Worman, H.J., and Lippincott-Schwartz, J. (1997). Nuclear membrane dynamics and reassembly in living cells: targeting of an inner nuclear membrane protein in interphase and mitosis. J. Cell Biol. 138, 1193-1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay, D.R., and Forbes, D.J. (1990). Reconstitution of biochemically altered nuclear pores: transport can be eliminated and restored. Cell 60, 17-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foisner, R., and Gerace, L. (1993). Integral membrane proteins of the nuclear envelope interact with lamins and chromosomes, and binding is modulated by mitotic phosphorylation. Cell 73, 1267-1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, D.J., Kirschner, M.W., and Newport, J.W. (1983). Spontaneous formation of nucleus-like structures around bacteriophage DNA microinjected into Xenopus eggs. Cell 34, 13-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gant, T.M., Harris, C.A., and Wilson, K.L. (1999). Roles of LAP2 proteins in nuclear assembly and DNA replication: truncated LAP2beta proteins alter lamina assembly, envelope formation, nuclear size, and DNA replication efficiency in Xenopus laevis extracts. J. Cell Biol. 144, 1083-1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geles, K.G., Johnson, J.J., Jong, S., and Adam, S.A. (2002). A role for Caenorhbiditis elegans importin IMA-2 in germ line and embryonic mitosis. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 3138-3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, M.W., Wiese, C., Allen, T.D., and Wilson, K.L. (1997). Dimples, pores, star-rings, and thin rings on growing nuclear envelopes: evidence for structural intermediates in nuclear pore complex assembly. J. Cell Sci. 110, 409-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, R.D., Gruenbaum, Y., Moir, R.D., Shumaker, D.K., and Spann, T.P. (2002). Nuclear lamins: building blocks of nuclear architecture. Genes Dev. 16, 533-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorlich, D., and Kutay, U. (1999). Transport between the cell nucleus and the cytoplasm. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 15, 607-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruss, O.J., Carazo-Salas, R.E., Schatz, C.A., Guarguaglini, G., Kast, J., Wilm, M., Le Bot, N., Vernos, I., Karsenti, E., and Mattaj, I.W. (2001). Ran induces spindle assembly by reversing the inhibitory effect of importin alpha on TPX2 activity. Cell 104, 83-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraguchi, T., Koujin, T., Hayakawa, T., Kaneda, T., Tsutsumi, C., Imamoto, N., Akazawa, C., Sukegawa, J., Yoneda, Y., and Hiraoka, Y. (2000). Live fluorescence imaging reveals early recruitment of emerin, LBR, RanBP2, and Nup153 to reforming functional nuclear envelopes. J. Cell Sci. 113, 779-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harel, A., Orjalo, A.V., Vincent, T., Lachish-Zalait, A., Vasu, S., Shah, S., Zimmerman, E., Elbaum, M., and Forbes, D.J. (2003). Removal of a single subcomplex results in vertebrate nuclei devoid of nuclear pores. Mol. Cell 11, 853-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heald, R., Tournebize, R., Blank, T., Sandaltzopoulos, R., Becker, P., Hyman, A., and Karsenti, E. (1996). Self-organization of microtubules into bipolar spindles around artificial chromosomes in Xenopus egg extracts. Nature 382, 420-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetzer, M., Bilbao-Cortes, D., Walther, T.C., Gruss, O.J., and Mattaj, I.W. (2000). GTP hydrolysis by Ran is required for nuclear envelope assembly. Mol. Cell 5, 1013-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetzer, M., Meyer, H.H., Walther, T.C., Daniel Bilbao-Cortes, D., Warren, G., and Mattaj, I.W. (2001). Distinct AAA-ATPase p97 complexes function in discrete steps of nuclear assembly. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 1086-1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber, J., Dickmanns, A., and Luhrmann, R. (2002). The importin-beta binding domain of snurportin1 is responsible for the Ran- and energy-independent nuclear import of spliceosomal U snRNPs in vitro. J. Cell Biol. 156, 467-479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalab, P., Pu, R.T., and Dasso, M. (1999). The Ran GTPase regulates mitotic spindle assembly. Curr. Biol. 9, 481-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalab, P., Weis, K., and Heald, R. (2002). Visualization of a Ran-GTP gradient in interphase and mitotic Xenopus egg extracts. Science 295, 2452-2456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutay, U., Izaurralde, E., Bischoff, F.R., Mattaj, I., and Gorlich, D. (1997). Dominant-negative mutants of importin-beta block multiple pathways of import and export through the nuclear pore complex. EMBO J. 16, 1153-1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohka, M.J., and Masui, Y. (1984). Roles of cytosol and cytoplasmic particles in nuclear envelope assembly and sperm pronuclear formation in cell-free preparations from amphibian eggs. J. Cell Biol. 98, 1222-1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusk, C.P., Makhnevych, T., Marelli, M., Aitchison, J.D., and Wozniak, R.W. (2002). Karyopherins in nuclear pore biogenesis: a role for Kap121p in the assembly of Nup53p into nuclear pore complexes. J. Cell Biol. 159, 267-278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macara, I.G. (2001). Transport into and out of the nucleus. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65, 570-594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macaulay, C., and Forbes, D.J. (1996). Assembly of the nuclear pore: biochemically distinct steps revealed with NEM, GTPγS, and BAPTA. J. Cell Biol. 132, 5-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marelli, M., Lusk, C.P., Chan, H., Aitchison, J.D., and Wozniak, R.W. (2001). A link between the synthesis of nucleoporins and the biogenesis of the nuclear envelope. J. Cell Biol. 153, 709-724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier, E., Miller, B., and Forbes, D.J. (1995). Nuclear pore complex assembly studied with a biochemical assay for annulate lamellae formation. J. Cell Biol., 129, 1459-1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchior, F., and Gerace, L. (1998). Two-way trafficking with Ran. Trends Cell Biol. 8, 175-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, B.R., and Forbes, D.J. (2000). Purification of the vertebrate nuclear pore by biochemical criteria. Traffic 1, 941-951. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachury, M.V., Maresca, T.J., Salmon, W.C., Waterman-Storer, C.M., Heald, R., and Weis, K. (2001). Importin beta is a mitotic target of the small GTPase Ran in spindle assembly. Cell 104, 95-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newport, J. (1987). Nuclear reconstitution in vitro: stages of assembly around protein-free DNA. Cell 48, 205-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers, M.A., Macaulay, C., Masiarz, F.R., and Forbes, D.J. (1995). Reconstituted nuclei depleted of a vertebrate GLFG nuclear pore protein, p97 (Nup98), import but are defective in nuclear growth and replication. J. Cell Biol. 128, 721-736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu, R.T., and Dasso, M. (1997). The balance of RanBP1 and RCC1 is critical for nuclear assembly and nuclear transport. Mol. Biol. Cell 8, 1955-1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raharjo, W.H., Enarson, P., Sullivan, T., Stewart, C.L., and Burke, B. (2001). Nuclear envelope defects associated with LMNA mutations cause dilated cardiomyopathy and Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. J. Cell Sci. 114, 4447-4457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rout, M.P., Aitchison, J.D., Suprapto, A., Hjertaas, K., Zhao, Y., and Chait, B.T. (2000). The yeast nuclear pore complex. Composition, architecture, and transport mechanism. J. Cell Biol. 148, 635-652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudt, F., and Pieler, T. (2001). Cytosolic import factor- and Ran-independent nuclear transport of ribosomal protein L5. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 80, 661-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, K.J., McCaffery, J.M., and Wente, S.R. (2003). The Ran GTPase cycle is required for yeast nuclear pore complex assembly. J. Cell Biol. 160, 1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwoebel, E.D., Ho, T.H., and Moore, M.S. (2002). The mechanism of inhibition of Ran-dependent nuclear transport by cellular ATP depletion. J. Cell Biol. 157, 963-974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah, S., Tugendreich, S., and Forbes, D. (1998). Major binding sites for the nuclear import receptor are the internal nucleoporin Nup153 and the adjacent nuclear filament protein Tpr. J. Cell Biol. 141, 31-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steggerda, S.M., and Paschal, B.M. (2002). Regulation of nuclear import and export by the GTPase Ran. Int. Rev. Cytol. 217, 41-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoffler, D., Fahrenkrog, B., and Aebi, U. (1999). The nuclear pore complex: from molecular architecture to functional dynamics. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 11, 391-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takizawa, C.G., Weis, K., and Morgan, D.O. (1999). Ran-independent nuclear import of cyclin B1-Cdc2 by importin beta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 7938-7943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timinszky, G., Tirián, L., Nagy, F.T., Tóth, G., Perczel, A., Kiss-László, Z., Boros, I., Clarke, P.R., and Szabad, J. (2002). The importin-beta P446L dominant-negative mutant protein loses RanGTP binding ability and blocks the formation of intact nuclear envelope. J. Cell Sci. 115, 1675-1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman, K.S., and Forbes, D.J. (1995). RNA polymerase III transcription in synthetic nuclei assembled in vitro from defined DNA templates. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 4873-4883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasu, S. and Forbes, D.J. (2002). Nuclear pores and nuclear assembly. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13, 363-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasu, S., Shah, S., Orjalo, A., Park, M., Fischer, W.H., and Forbes, D.J. (2001). Novel vertebrate nucleoporins Nup133 and Nup160 play a role in mRNA export. J. Cell Biol. 155, 339-354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther, T.C., et al. (2003). The conserved Nup107–160 complex is critical for nuclear pore complex assembly. Cell 113, 195-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther, T.C., Fornerod, M., Pickersgill, H., Goldberg, M., Allen, T.D., and Mattaj, I.W. (2001). The nucleoporin Nup153 is required for nuclear pore basket formation, nuclear pore complex anchoring and import of a subset of nuclear proteins. EMBO J. 20, 5703-5714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther, T.C., Pickersgill, H.S., Cordes, V.C., Goldberg, M.W., Allen, T.D., Mattaj, I.W., and Fornerod, M. (2002). The cytoplasmic filaments of the nuclear pore complex are dispensable for selective nuclear protein import. J. Cell Biol. 158, 63-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis, K. (2003). Regulating access to the genome: nucleocytoplasmic transport throughout the cell cycle. Cell 112, 441-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wente, S.R., Rout, M.P., and Blobel, G. (1992). A new family of yeast nuclear pore complex proteins. J. Cell Biol. 119, 705-723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese, C., Wilde, A., Moore, M.S., Adam, S.A., Merdes, A., and Zheng, Y. (2001). Role of importin-beta in coupling Ran to downstream targets in microtubule assembly. Science 291, 653-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L., Guan, T., and Gerace, L. (1997). Integral membrane proteins of the nuclear envelope are dispersed throughout the endoplasmic reticulum during mitosis. J. Cell Biol. 137, 1199-1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C., and Clarke, P.R. (2000). Chromatin-independent nuclear envelope assembly induced by Ran GTPase in Xenopus egg extracts. Science 288, 1429-1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C., and Clarke, P.R. (2001). Roles of Ran-GTP and Ran-GDP in precursor vesicle recruitment and fusion during nuclear envelope assembly in a human cell-free system. Curr. Biol. 11, 208-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C., Goldberg, M.W., Moore, W.J., Allen, T.D., and Clarke, P.R. (2002a). Concentration of Ran on chromatin induces decondensation, nuclear envelope formation and nuclear pore complex assembly. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 81, 623-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C., Hutchins, J.R., Muhlhausser, P., Kutay, U., and Clarke, P.R. (2002b). Role of importin-beta in the control of nuclear envelope assembly by Ran. Curr. Biol. 12, 498-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]