Abstract

Obesity and age are important risk factors for cardiovascular disease. However, the signaling mechanism linking obesity with age-related vascular senescence is unknown. Here we show that mice fed a high-fat diet show increased vascular senescence and vascular dysfunction compared to mice fed standard chow and are more prone to peripheral and cerebral ischemia. All of these changes involve long-term activation of the protein kinase Akt. In contrast, mice with diet-induced obesity that lack Akt1 are resistant to vascular senescence. Rapamycin treatment of diet-induced obese mice or of transgenic mice with long-term activation of endothelial Akt inhibits activation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)–rictor complex 2 and Akt, prevents vascular senescence without altering body weight, and reduces the severity of limb necrosis and ischemic stroke. These findings indicate that long-term activation of Akt-mTOR signaling links diet-induced obesity with vascular senescence and cardiovascular disease.

INTRODUCTION

The risk of cardiovascular diseases increases markedly with age and body mass index (1, 2). Although other risk factors, such as diabetes and hypertension, are associated with age and obesity, obesity and age per se are direct risk factors for cardiovascular disease (1, 2). The mechanisms linking obesity and age to increased cardiovascular disease, however, remain unknown.

Cellular senescence is associated with aging and is often defined biologically as a tendency toward cell cycle arrest or decreased replicative potential (3). It has been used as a model for mammalian aging and contributes to tumor suppression (4). Some studies suggest that cellular senescence may be an important cause or consequence of obesity and obesity-induced vascular complications (5, 6). However, it remains unclear how obesity could induce cellular senescence and whether vascular dysfunction associated with senescence of cells in the vasculature (vascular senescence) contributes to diet-induced cardiovascular disease.

Deletion of either protein kinases Akt or mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) prevents cellular senescence in yeast (7, 8). mTOR and Akt are nutrient sensors (9, 10) that are involved in regulating cellular metabolism (11), obesity (12), cell survival (13), and cellular responses to injury (14). Thus, Akt and mTOR could provide a link between obesity, vascular senescence, and vascular complications of obesity. Akt activation depends on two sequential phosphorylations: the first on Thr308 by phosphatidylinositol-dependent kinase–1 (PDK-1) and the second on Ser473 by mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) (15–17). mTOR exists in two distinct complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2. mTORC1, which consists of mTOR and raptor (regulatory-associated protein of mTOR), regulates cell growth through S6 kinase 1 (S6 K1) and the eIF-4E–binding protein 1 (4E-BP1); mTORC2, which consists of mTOR, rictor (rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR), and SIN1 (stress-activated protein kinase–interacting protein 1), phosphorylates Akt, thereby contributing to its phosphorylation-dependent activation (18). The two mTORC complexes are differentially sensitive to rapamycin. Because mTORC2 is relatively rapamycin resistant, most of the inhibitory effects of rapamycin are thought to be due to pathways mediated by mTORC1 (19). However, recent reports indicate that rapamycin can also suppress the assembly and function of mTORC2 and thereby inhibit Akt phosphorylation and activation (20–22).

Akt was originally identified as an oncogene (23) and later shown to be important in mediating vascular function (14). It mediates the effects of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) on endothelial survival and migration (24). In addition, endothelium-dependent vasodilatation is mediated by Akt-dependent phosphorylation and activation of endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase (eNOS) (25, 26). Indeed, short-term overexpression of constitutively active Akt in the vascular endothelium increases blood flow, NO production, and vascular protection (27). However, the long-term effects of Akt activation and its relationship to vascular senescence and function remain to be determined.

We hypothesized that long-term increase in food intake may increase obesity- and age-related cardiovascular disease through the induction of vascular senescence. Because Akt is an important mediator of cell metabolism and obesity, and deletion of Akt can improve yeast life span, we hypothesized this obesity-related vascular senescence could be related to excessive Akt activation. Here we show that diet-induced obesity in mice causes vascular senescence and dysfunction through long-term intermittent activation of Akt.

RESULTS

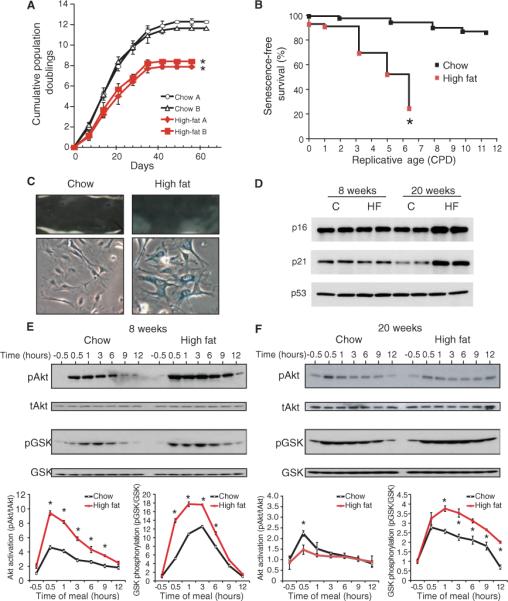

High-fat diet increases vascular senescence and Akt signaling

To determine whether obesity and vascular senescence are linked, we first investigated whether obesity could increase vascular senescence in mice fed a high-fat diet, where 60% of the total calories consumed is in the form of fat. Two parallel sets of independent experiments were performed on mice (three to five per group) fed chow or a high-fat diet for 12 weeks (from 4 to 16 weeks of age). Compared to mice fed a chow diet, mice fed a high-fat diet developed a 53% increase in body weight and had increased concentrations of serum cholesterol, triglyceride, glucose, and insulin (Table 1). Endothelial cells isolated from the aortas of these mice were subjected to serial passages to test their replicative capacity as a measure of cellular senescence. Endothelial cells from mice fed a high-fat diet showed early replicative senescence compared to that of endothelial cells from mice fed chow diet. The cumulative population doublings of endothelial cells from mice on a high-fat diet were 30% less than those from mice fed a chow diet (8.13 ± 0.27 versus 11.94 ± 0.45) (Fig. 1A). This decrease in cumulative population doubling correlated with increased cellular senescence as determined by the fraction of cells showing senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β) staining. Whereas, after five passages, more than 80% of the cells from the group fed a high-fat diet were positive for SA-β staining, even when maintained for 10 passages, less than 10% of the cells from the groups fed a chow diet showed positive SA-β staining (Fig. 1, B and C). To verify that the endothelial cell phenotype was maintained through repeated passages, we stained the cells with endothelial cell–specific CD31 antibody. CD31-positive cells accounted for around 95 to 97% of cells after isolation and around 90 to 92% of cells after five passages. The en face aortic surface, which is composed mostly of endothelial cells, of the high-fat diet group also showed increased SA-β staining compared to that of the chow diet group (Fig. 1C), excluding the possibility of false-positive results caused by isolation, propagation, and clonal outgrowth of different populations of endothelial cells. Aortic lysates from the 20-week group of mice fed a high-fat diet also showed increased p16 and p21, features consistent with increased cellular senescence (Fig. 1D).

Table 1.

Body weight and serum measurements in mice at 20 weeks of age. Metabolic parameters in mice fed a high-fat or chow diet. Body weight, serum triglyceride, cholesterol, glucose, and insulin were determined in 20-week–old mice (mean ± SD, n = 8 mice per group).

| Chow diet | High-fat diet | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (g) | 26.3 ± 1.9 | 40.1 ± 2.5 | <0.01 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 143 ± 5.2 | 231 ± 21 | <0.01 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | 65 ± 3.1 | 113 ± 6.3 | <0.01 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 113 ± 23 | 278 ± 40 | <0.01 |

| Insulin (ng/ml) | 0.78 ± 0.33 | 4.78 ± 0.87 | <0.01 |

Fig. 1.

High-fat diet induces vascular senescence and promotes phosphorylation of endothelial Akt. (A) Analysis of in vitro life span of aortic endothelial cells from mice fed a high-fat or chow diet based on cumulative population doubling (CPD). Obtained from two independent sets of experiments (n = 3 mice in group Aand n = 5 mice in group B). (B) Senescence-free survival analysis of aortic endothelial cells (assessed by the presence or absence of β-galactosidase staining). A 100% senescence-free value corresponds to no β-galactosidase staining. (n = 5 mice per group). (C) Aortic endothelial cells and aortic en face staining with senescence-related β-galactosidase (n = 5 aortas in high-fat or chow group for 12 weeks). (D) Aortic p16, p21, and p53 abundance assessed by Western blot. C, chow; HF, high fat. (E) Immunoblots showing time-dependent effects of high-fat or chow diet on Akt phosphorylation and Akt activity (determined by phospho-Akt/total Akt (tAkt) and phospho-GSK/total GSK, respectively) after feeding at 8 and (F) 20 weeks. Densitometric analyses of each blot are shown at the bottom panels. Results are presented as mean ± SD. Each lane represents one or two mice. Each experiment was performed three times. *P < 0.05 compared to chow diet.

We then examined whether Akt activity was altered by a high-fat diet and whether this correlated with increased vascular senescence. We first investigated the acute effects of a high-fat meal on Akt activation. Mouse aortas were isolated 30 min before and at selected intervals from 30 min to 12 hours after a meal. The postprandial activation of aortic Akt, assessed by phosphorylation of Akt and that of its substrate glycogen synthase kinase (GSK), was substantially greater and remained increased for a longer duration in 8-week–old mice fed a high-fat meal compared to those fed a meal of regular chow (high fat versus chow, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1E). Twenty-week–old mice that had previously been on a high-fat diet (12 weeks on high-fat followed by 4 weeks on regular chow diet) developed insulin resistance (Table 1) and showed decreased postprandial Akt phosphorylation but increased GSK phosphorylation compared to mice fed for 16 weeks on chow (high fat versus chow, P < 0.05) (Fig. 1F). The discordance between postprandial Akt and GSK phosphorylation is unknown, but may be due to additional GSK regulation by GSK phosphatases (28). To determine if the increase in phosphorylated Akt (pAkt) was sustained or occurred only after a high-fat meal, we followed the effect of repeated high-fat meals over 24 hours from different mice that were fed at the same time. On day 1, the baseline fraction of pAkt to total Akt before a meal was similar. Postprandial Akt phosphorylation increased to a similar degree after each meal. On day 2, baseline pAkt was increased 1.3 times compared to baseline on day 1 (day 1 versus day 2, P < 0.05) (fig. S1A). These findings suggest that pAkt and Akt activity in the mouse aorta are persistently increased after a high-fat diet meal.

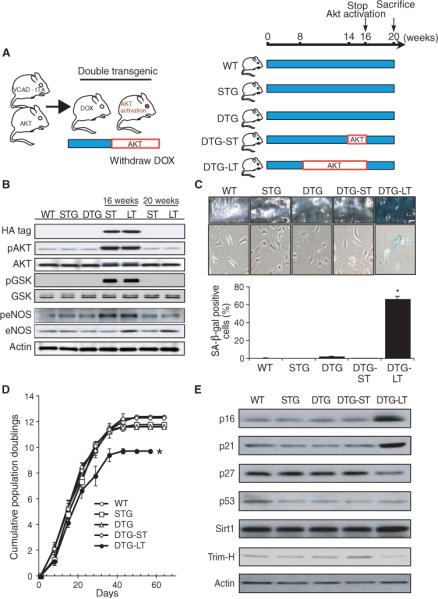

Endothelial Akt activation increases vascular senescence

To determine whether Akt activation could lead to increased vascular senescence in vivo, we assessed vascular senescence in a line of transgenic mice in which we could conditionally induce activation of endothelial Akt to mimic endothelial Akt activation during excessive long-term food intake (27). Wild-type (WT) mice, single transgenic mice [tet-myrAkt without vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-cadherin)-tTA] and double transgenic Akt mice (VE-cadherin-tTA/tet-myrAkt) in which Akt expression was not induced were used as controls. For short-term activation, the Akt transgene was induced for 2 weeks from age 14 to 16 weeks. For long-term activation, the Akt transgene was induced for 8 weeks from age 8 to 16 weeks. To control for immediate vascular effects secondary to Akt activation, the Akt transgene was then suppressed in both groups of mice for an additional 4 weeks by reinstitution of doxycycline (Fig. 2A). The induction and suppression of the Akt transgene as well as the consequent changes in Akt activity [assessed by phosphorylation of GSK and of eNOS (also a downstream target of Akt)] were confirmed in aortic tissue from both short- and long-term groups at 16 and 20 weeks (Fig. 2B). In contrast to control and double transgenic mutant mice with short-term Akt activation, double transgenic mutant mice with long-term Akt activation showed increased aortic vascular senescence, with increased SA-β staining in en face aortic surface and isolated aortic endothelial cells (SA-β–positive cells in long-term versus short-term: 67% versus 2.3%, respectively, P < 0.01) (Fig. 2C). Aortic endothelial cells isolated from mutant mice with long-term Akt activation also showed a decrease in cumulative population doubling (long-term versus other four control groups, P < 0.01) (Fig. 2D). This was associated with increased expression of p16 and p21 and decreased expression of p27 and trimethyl histone—features that are consistent with increased cellular senescence (29–32) (Fig. 2E). Mitochondrial membrane potential, which is reduced in senescent cells, was decreased by long-term, but not short-term, Akt activation and by a high-fat diet (fig. S2). These findings suggest that long-term Akt activation, either by transgene induction or by a high-fat diet, leads to vascular senescence.

Fig. 2.

Chronic Akt activation increases vascular senescence. (A) Strategy for generating double transgenic mice (VE-cadherin-tTA/tet-myrAkt) with endothelial-specific, inducible expression of myrAkt transgene. Inducible expression is accomplished by doxycycline (DOX) withdrawal (left). Protocol for short-term (ST, 2 weeks) and long-term (LT, 8 weeks) induction of Akt transgene expression followed by its suppression for 4 weeks (right). WT, wild-type; STG, single transgenic mice (tet-myrAkt); DTG, double transgenic mice (VE-cadherin-tTA/tet-myrAkt). (B) Immunoblot analyses of transgene marker (HA tag) and phosphorylation of Akt and its downstream targets, GSK and eNOS, in mice aortic lysates. Actin is included as a loading control. (C) SA-β staining of aorta and aortic endothelial cells from WT and mutant Akt mice with short-term (ST) and long-term (LT) Akt transgene expression. Results are expressed as mean ± SD, n > 5 aortas per group. *P < 0.01 compared to the other four groups of mice. (D) Cumulative population doubling analysis of in vitro life span of aortic endothelial cells from WT and Akt mutant mice. *P < 0.01 compared to the other four groups of mice. (E) Immunoblot analyses of cell cycle proteins (p16, p21, p27, and p53) and senescence-related markers (Sirt1 and Trim-H) in endothelial cells from WT and Akt mutant mice.

Long-term activation of endothelial Akt impairs vascular function

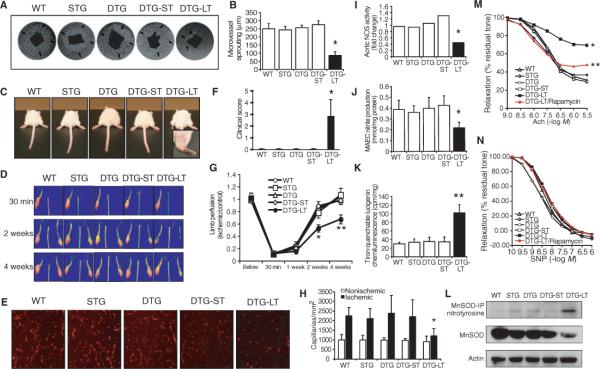

To determine whether endothelial senescence has pathophysiological relevance, we investigated whether angiogenesis and blood flow recovery in response to limb ischemia are altered in mutant mice with long-term activation of endothelial Akt. Previous studies have shown that endothelial Akt regulates pathological angiogenesis and vascular permeability (22, 33). However, in contrast to previous studies showing that short-term Akt activation of less than 2 weeks promotes angiogenesis (14), long-term endothelial Akt activation decreased microvessel sprouting from aorta ex vivo (Fig. 3, A and B), caused greater distal limb necrosis (Fig. 3, C and F), and decreased blood flow recovery (Fig. 3, D and G) after hindlimb ischemia. The reduced angiogenic response corresponded with a 46% decrease in capillary density formation in the ischemic limb (Fig. 3, E and H). In isolated aortas, long-term Akt activation led to a 58% decrease in eNOS activity (Fig. 3I) and a 45% decrease in NO production (Fig. 3J). This correlated with increased vascular oxidative stress as determined by tiron-inhibitable lucigenin chemiluminescence (Fig. 3K) and increased tyrosine nitrosylation of manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) (Fig. 3L) in the isolated mouse aorta and aortic lysates. Interestingly, the total MnSOD concentration was also reduced by long-term Akt activation. Consistent with the decrease in NO production, endothelium-dependent, but not endothelium-independent, relaxation was impaired in aortas from mutant mice with long-term Akt activation (Fig. 3, M and N).

Fig. 3.

Impaired vascular function in mice with chronic Akt activation. (A) Sprouting of microvessels in Matrigel (arrows) from aortas derived from WT, single transgenic (STG), and double transgenic (DTG) mice with short-term (ST) and long-term (LT) Akt activation (n = 6 mice in each group). (B) Quantification of the microvessel sproutings from aortic ring. (C and F) Clinical score and photograph of leg gangrene in WT, STG, and DTG mice with and without short-term Akt activation and long-term Akt activation. Mice in the first four groups are normal, with a clinical score of 0. The DTG mice with long-term activation of Akt exhibited leg gangrene, with a clinical score of 2.9 (n = 6 to 8 mice in each group). (D and G) Laser Doppler images of hindlimb blood flow and quantification of blood flow in the lower limb after hindlimb ischemia in WT and mutant Akt mice (n = 6 to 8 mice in each group). (E and H) Representative images of microcapillaries in the hindlimb adductor muscle with quantification using Alexa 568–linked Isolectin B4 antibody (n = 6 to 8 mice in each group). (I) Measurements of eNOS activity in aortic lysates of WT and mutant Akt mice. (J) Nitrite accumulation from aortic endothelial cells (MAEC) derived from WT and mutant Akt mice. (K) Production of superoxide anion from mouse aorta as determined by lucigenin chemiluminescence assay. (L) Immunoblot analyses nitrotyrosinylation and expression of MnSOD in WT and mutant Akt mice. For nitrotyrosinylation of MnSOD, MnSOD was immunoprecipitated (IP) followed by immunoblotting with nitrotyrosine antibody. Results are presented as mean ± SD, n = 6 mice in each group. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 when compared to other four groups. Relaxation of aorta to (M) acetylcholine (Ach) (endothelium-dependent) and (N) to sodum nitroprusside (SNP) in the presence of L-NAME (endothelium-independent) in WT, STG, and DTG mice, with and without short-term (ST) or long-term (LT) activation of Akt, and DTG mice with long-term Akt activation with rapamycin (DTG-LT/rapamycin). Relaxation is shown as percent of residual tone. (n > 6 aortas in each group, *P < 0.05 when compared to other groups, **P < 0.05 when compared to DTG-LT/rapamycin group.)

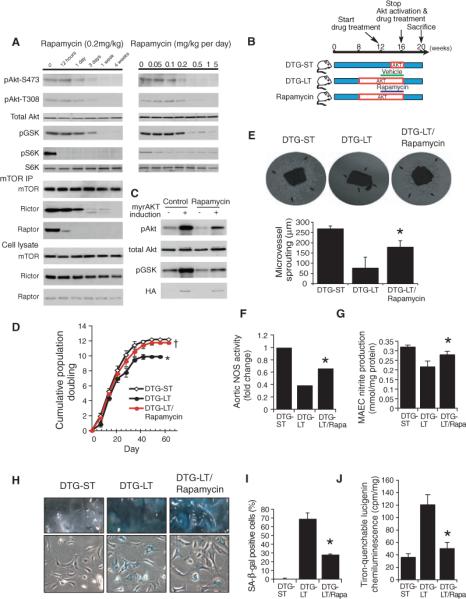

Akt inhibition decreases cellular senescence and enhances vascular function

Although mTORC2, which phosphorylates and activates Akt (16, 34), is relatively rapamycin insensitive, several studies suggest that under certain conditions, rapamycin can inhibit mTORC2 and, thereby, Akt activation (20–22). Using implantable subcutaneous pumps, we administered rapamycin to mice for varying amounts of time and determined aortic Akt activity 30 min after a meal. We found that aortic Akt phosphorylation was decreased after 1 week of treatment with rapamycin (0.2 mg/kg per day) (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, immunoprecipitation of mTOR showed that like mTORC1, mTORC2 complex dissociated after treatment with rapamycin (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of Akt-induced vascular senescence by rapamycin. (A) Dose- and time-dependent inhibition of Akt phosphorylation and mTORC2 complex formation by rapamycin. Mice were treated with rapamycin for indicated times and duration. Aortic lysates and mTOR immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blot. (B) Rapamycin treatment protocol. Rapamycin was administered from 12 to 16 weeks. (C) Validation of inhibition of Akt activation by rapamycin (1 mg/kg per day, 4 weeks) in Akt mutant mice in aorta by Western blot. Blots are representative of six mice in each group. (D) Cumulative population doublings of aortic endothelial cells from mutant mice with short-term and long-term Akt activation, with and without rapamycin (n = 6 mice in each group). *P < 0.05 compared to short-term and rapamycin group. †P = 0.11 compared to acute group. (E) Microvessel sprouting (arrows) from aortas of mice with short-term or long-term Akt activation with or without rapamycin treatment. *P < 0.05 compared to long-term group. (F and G) Aortic NOS activity and NO in mutant mice with long-term Akt activation with and without rapamycin (Rapa) (n = 6 mice in each group). (H) SA-β staining of endothelial cells and en face aortas from double transgenic Akt mutant mice (DTG) with no transgene induction, and with short-term or long-term Akt induction with or without rapamycin (Rapa) treatment. (I) Quantification of SA-β staining positive cells (n = 6 mice in each group). *P < 0.05 compared with chronic groups. (J) Lucigenin chemiluminescence as a measure of intracellular oxidative stress in DTG mice with short- and long-term Akt activation with and without rapamycin (n = 6 mice in each group). *P < 0.05 compared with the DTG-LT group.

To confirm whether this inhibition of Akt activation by rapamycin has pathophysiological relevance and could prevent the senescence phenotype and impaired angiogenesis caused by a high-fat diet or long-term Akt activation, we treated WT mice on a high-fat diet or double transgenic mice with long-term Akt activation with rapamycin (35, 36). In both cases, rapamycin or vehicle was administered (Fig. 4B) and inhibition of aortic Akt phosphorylation, but not Akt expression, was confirmed by Western analysis (Fig. 4C). Rapamycin (0.2 to 1 mg/kg per day) did not alter food intake, body weight, blood glucose, or serum insulin and lipid concentrations (Table 2). Endothelial cells from transgenic mice with long-term Akt activation that were treated with rapamycin (1 mg/kg per day, 4 weeks) showed an increased replicative life span (Fig. 4D), endothelial sprouting (Fig. 4E), eNOS activity (Fig. 4, F and G), and endothelium-mediated vasorelaxation (Fig. 5, G and H) and decreased SA-β staining (Fig. 4, H and I) and oxidative stress (Fig. 4J). This correlated with improved angiogenic response (Fig. 5A), blood flow recovery (Fig. 5B), limb necrosis (Fig. 5C), and capillary density (Fig. 5D) after hindlimb ischemia.

Table 2.

Body weight and serum measurements in mice with or without rapamycin at 20 weeks of age. Metabolic parameters in mice fed a high-fat or chow diet. Body weight, serum triglyceride, cholesterol, glucose, and insulin were determined in 20-week–old mice (mean ± SD, n = 10 mice per group).

| Chow/control | Chow/rapamycin | High fat/control | High fat/rapamycin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (g) | 32.7 ± 0.6 | 31.9 ± 1.1 | 40.4 ± 2.0 | 41.1 ± 1.9 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 123 ± 5.1 | 118 ± 1.6 | 146 ± 2.4 | 154 ± 3.3 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | 76 ± 4.2 | 69 ± 3.0 | 132 ± 1.7 | 137 ± 2.3 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 132 ± 32 | 125 ± 33 | 181 ± 24 | 190 ± 39 |

| Insulin (ng/mL) | 0.74 ± 0.23 | 0.69 ± 0.43 | 5.12 ± 0.42 | 4.99 ± 0.58 |

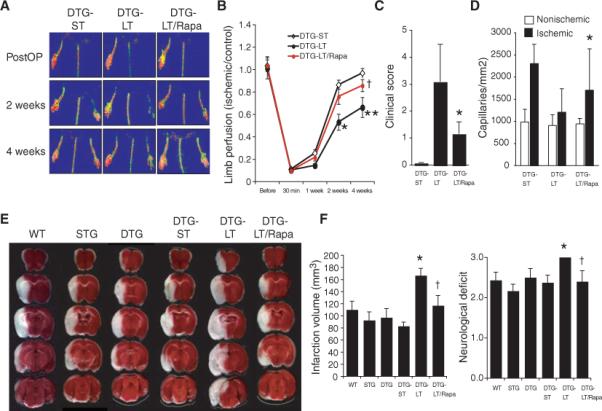

Fig. 5.

Reversal of Akt-induced impaired vascular function with rapamycin. (A) Representative laser Doppler blood flow imaging of hindlimb after femoral artery ligation (PostOP) in double transgenic (DTG) Akt mutant mice with no, short-term (ST), and long-term (LT) activation of Akt, with and without rapamycin (Rapa). (B) Blood flow recovery in ischemic limb after hindlimb ligation. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 7 in each group). †P > 0.05 compared to DTG-ST group. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared to DTG-ST and DTG-LT + rapamycin groups, respectively. (C and D) Quantification of clinical score and capillary densities after hindlimb ischemia in DTG mice with short-term and long-term activation of Akt, with and without rapamycin (n = 7 in each group). *P < 0.05 compared with DTG-LT group. (E) Photomicrographs of coronal triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC)–stained brain sections after transient MCA occlusion (n = 6 to 9 mice in each group). (F) Stroke infarction volumes and neurological deficit scores in wild-type (WT), single transgenic (STG), and double transgenic (DTG) Akt mutant mice with and without short- and long-term induction of myrAkt trans-gene, with and without rapamycin (rapa) treatment (n = 6 to 9 mice per group). *P < 0.01 compared to DTG-ST mice; †P < 0.05 compared to DTG-LT mice.

Similar findings were observed in a mouse model of another vascular disease associated with aging—ischemic stroke. Following transient middle cerebral artery occlusion, transgenic mice with long-term Akt activation had substantially larger cerebral infarct size and worse neurological deficits than did WT or the various control mice (Fig. 5E). Treatment with rapamycin reduced cerebral infarct size and attenuated neurological deficits in mutant mice with long-term Akt activation (Fig. 5F).

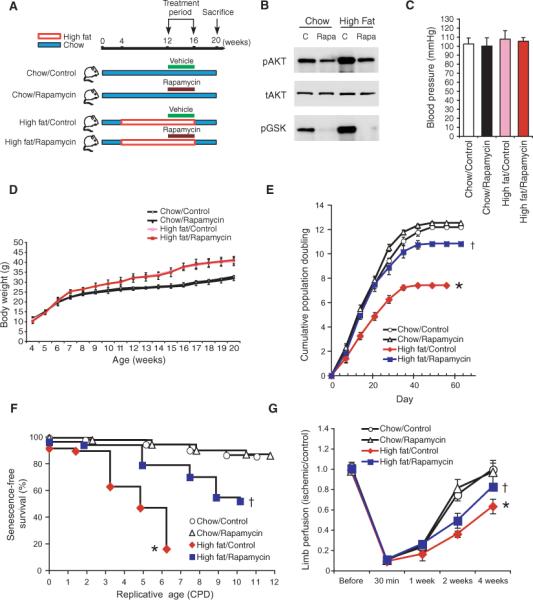

To determine whether inhibition of Akt activation attenuates obesity-induced vascular senescence, mice fed a high-fat or chow diet were treated with rapamycin (0.2 mg/kg per day) or vehicle for 4 weeks (Fig. 6A). Inhibition of Akt activation by a high-fat diet was confirmed in aortic tissue by Western analysis (Fig. 6B). Mice receiving rapamycin did not show changes in systemic blood pressure, body weight, blood glucose, insulin, and lipid concentrations (Fig. 6, C and D, and Table 2). Aortic endothelial cells from WT mice on a high-fat diet treated with rapamycin showed increased cumulative population doublings (10.8 versus 7.4, P < 0.01) (Fig. 6E) and decreased SA-β staining (Fig. 6F) compared to those from WT mice on a high-fat diet not given rapamycin treatment. Indeed, limb ischemia and necrosis were attenuated by rapamycin in WT mice on a high-fat diet (Fig. 6G), suggesting that rapamycin can ameliorate obesity-induced vascular senescence.

Fig. 6.

Reversal of diet-induced vascular senescence with rapamycin. (A) Schematic diagram showing the protocol for high-fat and chow diets with and without rapamycin treatment. (B) Confirmation of Akt inhibition by rapamycin (0.2 mg/kg per day, 4 weeks) in aortas from mice fed both a chow diet and a high-fat diet. Blots are representative of four mice in each group. (C) Blood pressure (mmHg) of WT mice on a regular chow or a high-fat diet, with and without rapamycin treatment (n = 10 mice in each groups). (D) Body weight (grams) of mice fed regular chow or a high-fat diet, with or without vehicle (control) or rapamycin treatment. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 10 mice in each group). (E) Cumulative population doublings (CPDs) of aortic endothelial cells from mice fed regular chow or a high-fat diet, with or without vehicle (control) or rapamycin treatment (n = 6 mice in each group). †Not significant when compared to mice fed a chow diet. *P < 0.01 compared to mice fed a high-fat diet without rapamycin. (F) SA-β staining of aortic endothelial cells isolated from mice fed a high-fat or chow diet, with and without vehicle or rapamycin (n = 5 mice per group). †Not significant when compared to chow diet. *P < 0.01 compared to mice fed a high-fat diet without rapamycin. (G) Blood flow recovery in ischemic limb after femoral artery ligation. Results are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 4 to 5. †P > 0.05 compared to acute group. *P < 0.05 compared to the high-fat diet group without rapamycin.

Decreased obesity-induced vascular senescence in mice lacking Akt1

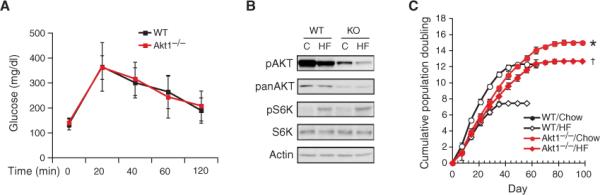

High-fat diet could activate many signaling pathways other than those involving Akt. For example, S6 K phosphorylation by mTOR could be increased by a high-fat diet through mechanisms independent of Akt activation (fig. S1, B and C). To determine whether Akt mediates obesity-induced vascular senescence, we assessed vascular function and senescence in mice lacking Akt1 (Akt1 null mice) fed a high-fat diet. The Akt1 null mice were used because Akt1 is the predominant Akt isoform in vasculature (33). In agreement with previous studies (37, 38), we found that Akt1 null mice had a 31% smaller body weight than did WT mice but showed no differences in glucose tolerance test when fed a high-fat diet (Fig. 7A). The percentage weight gain in Akt1 null mice on a high-fat diet was comparable to that of WT mice. Although aortas from Akt1 null mice showed decreased Akt phosphorylation, S6 K phosphorylation was comparable to that of WT mice (Fig. 7B). Furthermore, endothelial cells from Akt1 null mice fed a high-fat diet exhibited improved cumulative population doublings compared to that of WT mice (14% versus 40% decrease compared to mice fed chow, respectively) (Fig. 7C). Finally, treatment with rapamycin has no effect on vascular function or senescence in Akt1 null mice. These findings indicate that Akt is the predominant mediator of obesity-induced vascular senescence and that inhibition of Akt by rapamycin can prevent obesity-induced vascular senescence.

Fig. 7.

Akt1 null mice are resistant to obesity-induced vascular senescence. (A) Glucose tolerance test in WT and Akt1−/− mice after 12 weeks on a high-fat diet (n = 10 in each group). (B) Aortic Akt and S6 K phosphorylation levels in WT and Akt1−/− mice. Blots are representative of six mice in each group. (C) Cumulative population doublings (CPD) of aortic endothelial cells from WT and Akt1−/− mice fed a high-fat (HF) or a chow diet (n = 6 mice in each group). *Not significant when compared to mice fed a high-fat diet. †P < 0.01 compared to WT mice fed a high-fat diet.

DISCUSSION

Obesity and age-related vascular senescence are evolving processes, which are mechanistically linked and involve the long-term intermittent activation of Akt. Our findings indicate that a high-fat diet not only leads to obesity, but also to premature vascular senescence, as defined by vascular dysfunction due to cellular senescence of vascular wall cells. Although the canonical role of Akt is in cell growth and survival (18, 39), under chronic conditions, Akt activation may also increase cellular senescence and impair vascular function (30, 40). Vascular senescence is a phenotype of aging (41); however, the mechanistic link between aging and vascular senescence is not known. Nevertheless, vascular senescence could impair vascular function and thereby increase the susceptibility to age-related vascular pathologies such as peripheral ischemia and stroke.

Previous work has shown that Akt activation increases angiogenesis and that total loss of Akt is detrimental to vascular function (22, 24, 42). Our data indicate that excessive activation of Akt is also detrimental to vascular function. These observations suggest that a fine balance of Akt signaling is crucial in cellular physiology. Consistent with our study, over-activation of Akt by VEGF receptor-2 or mutation of the circadian gene, Per2, leads to increased vascular senescence (40, 43). We found that rapamycin inhibited aortic Akt phosphorylation induced by a high-fat diet. This was surprising because rapamycin is generally thought to target only mTORC1 (19, 44), which is downstream of Akt. However, recent studies showed that, in some cases, prolonged treatment with rapamycin could inhibit mTORC2 assembly and function (21, 22). Indeed, mTORC1 and mTORC2 are both important in endothelial function (45), and TORC2 has been shown to be critical in regulating Akt activity in Drosophila (46) and mice (17). Therefore, our findings that rapamycin inhibits mTORC2 complex strongly suggest that aortic Akt phosphorylation is directly inhibited by rapamycin and that rapamycin can prevent vascular senescence induced by a high-fat diet or long-term Akt activation.

Although mTOR signaling in the hypothalamus regulates food intake (10) and absence of S6 K enhances insulin sensitivity and protects against diet- and age-related obesity (12), our findings in Akt1 null mice fed a high-fat diet suggest that Akt, rather than mTOR, is the critical mediator of vascular senescence because mTOR activity was increased to a similar extent by a high-fat diet in WT and Akt1 null mice. However, we cannot completely exclude an additional role of mTOR or S6 K in this process. Despite mTOR's role as a homeostatic nutrient sensor (9), rapamycin, at the concentrations used in this study, did not alter food intake or body weight. These findings, therefore, provide a mechanistic link between diet-induced obesity and cellular senescence and suggest that inhibition of Akt signaling with rapamycin therapy may have clinical benefits in obesity- and age-related vascular disease.

We conclude that chronic, long-term activation of Akt is an important mediator of vascular senescence. Furthermore, blocking Akt phosphorylation with rapamycin leads to inhibition of vascular senescence in both the transgenic mice and high-fat diet–induced obese mice, suggesting that rapamycin may be a useful therapy. Because rapamycin is not a specific Akt inhibitor, it is possible that rapamycin could affect other signaling pathways that mediate senescence. However, rapamycin had no effect on vascular function and senescence in Akt1 null mice, suggesting that Akt is the rapamycin target for reducing vascular senescence and improving vascular function. Nevertheless, further studies are required to determine whether rapamycin could exert other effects, such as preventing mitochondrial dysfunction or reducing oxidative stress, which could contribute to its antisenescent effect.

The downstream target of Akt that mediates vascular senescence is not known. Previous studies have shown that alterations in the expression of important cell cycle regulators, such as p16, p21, p27, and trimethyl histone, are correlated with increased vascular senescence (29–32). Indeed, expression of p16, p21, p27, and trimethyl histone was altered in the vasculature of diet-induced obese mice. Furthermore, FOXO transcription factors, which mediate oxidative stress and cellular senescence signaling, are also phosphorylated by Akt and thus may involved in mediating vascular senescence (47). In addition, Akt has been shown to inhibit the transcriptional coactivator peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor coactivator 1α (PGC-1α) (48). PGC-1α is a global regulator of mitochondrial function, energy expenditure, skeletal muscle type switching, and hepatic metabolism, which are important contributors to the development of obesity and diabetes mellitus (49, 50). Because PGC-1α, FOXO, p21, and p27 signaling pathways are downstream of Akt and are implicated in cellular senescence, modulation of Akt may have therapeutic benefits in preventing age-related cardiovascular disease. However, the vascular senescence induced by obesity may not be exclusively due to Akt. Indeed, the decrease of population doublings in endothelial cells caused by long-term activation of Akt in double transgenic mice was less than that observed in endothelial cells from WT mice fed a high-fat diet. This suggests that other factors could contribute to obesity-induced vascular senescence. It remains to be determined what other signaling pathways are involved in obesity-induced senescence and whether these pathways complement the Akt pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and reagents

Antibodies directed against phospho-Akt (Ser473/Thr308), Akt, phospho-GSK (GSK 3β/Ser9), GSK, phospho-S6 K (Thr389), S6 K, mTOR, rictor, raptor, nitrotyrosine, p16, p21, and p53 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Beverly, MA). Unless specified, the phospho-Akt antibody used was directed against Ser473. Antibodies against phospho-eNOS (Ser1177) and eNOS were from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Antibodies against Sirt1 and trimethyl histone H3 were from Upstate Bio-technology (Lake Placid, NY). Doxycycline was from American Bioanalytical (Natick, MA). Rapamycin was from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA). Miniosmotic pumps were from Alzet (Cupertino, CA). The 60% high-fat diet was from Purina Mills (St. Louis, MO). The Nitric Oxide Synthase Kit was from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA).

Mouse models and isolation of aortic endothelial cells

The double transgenic mouse model that expresses myrAkt1 in endothelial cells under doxycycline control (VE-cadherin-tTA/tet-myrAkt) has been previously described (22, 27). The Akt1 null mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). All experimental protocols were approved by the Standing Committee on Animal Care at Harvard Medical School (Boston, MA). The isolation of mice aortic endothelial cells was previously described by using two-step sorting with antibody-coated magnetic beads [Dynabeads coated with antibodies specific for platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule–1 (PECAM-1) and intercellular adhesion molecule–2) (51). We generally obtain 5 × 104 cells from individual aortas. Endothelial cells are identified by immunofluorescence with an antibody to von Willebrandt factor.

Protocol for diet-induced obesity in mice

Male C57BL/6 J mice were trained for 7 days to consume a meal when it was presented. On day 7, animals were analyzed at seven different time points relative to the start of the meal. For high-fat diet experiments, mice were fed a high-fat diet (D12492, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) or chow diet from 4 to 16 weeks.

In vitro cell life-span analysis and cellular marker of senescence

Aortic endothelial cells were passaged weekly. Population doubling at each passage was calculated from the cell count by using the equation (52):

where N1 is inoculum number, NH is cell harvest number, and X is population doublings. The calculated population doublings were added up to yield cumulative population doubling. Replicative senescence was defined by X <1 for 3 weeks. SA-β staining was performed at pH 5.5 as previously described for endothelial cells and en face aortas (53).

Physiological and biochemical analyses

NOS activity assay

NOS activity was determined in aortic lysages by measuring the conversion of l-[3H]arginine to l-[3H]citrulline with the use of a NOS assay kit (Calbiochem) as previously described (27).

NOS activity assayed through NO production

Nitrite accumulation in the culture media was determined by chemiluminescence with the use of a nitric analyzer (NOA280i; Sievers Instruments, Inc). Nonspecific chemiluminescence was determined in the presence of l-NG-arginine methylester (L-NAME; 2 mmol/liter).

Lucigenin chemiluminescence

Oxidative stress as measured by NADPH (reduced form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate) oxidase activity in aortic lysates was determined with a microplate luminometer (MicroLumat Plus LB96 V; Berthold Technologies, Oak Ridge, TN) (54). Proteins or aortas were collected in modified Hepes buffer (140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 0.8 mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM Na2HPO4, 25 mM Hepes, and 1% glucose, pH 7.2) and distributed (100 mg per well) into a 96-well microplate. NADPH (100 mM) and dark-adapted lucigenin (5 mM) were added just before reading. Lucigenin chemiluminescence was recorded for 5 min and was expressed as units per minute per milligram of weight. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Organ chamber experiments

Thoracic aortas were carefully dissected and placed in ice-cold Krebs solution with the following composition (mM): NaCl 121, KCl 4.7, NaHCO3 24.7, MgSO4 12.2, CaCl2 2.5, KH2PO4 1.2, and glucose 5.8. Isolated aortic rings (5 mm) were mounted vertically in organ chamber myographs filled with Krebs solution. Isometric tension was recorded with a force transducer. To evaluate the basal release of endothelial NO, contractile response to cumulative concentrations of L-NAME was determined. Contractions were normalized and expressed as percentage of the amplitude of precontractions elicited by saline containing 100 mM KCl.

Methods for assessing angiogenesis

Aortic explants

The aortic explant studies were performed as previously described (51). Descending thoracic aortas were harvested and placed in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The aorta was flushed with ice-cold PBS until free of blood. The adventitia was dissected free, and the aorta was cut into multiple 1-mm rings under a dissecting microscope. Twenty-four–well culture plates were coated with 500 μl per well of growth factor–reduced Matrigel (BD Bioscience) and then allowed to polymerize for 30 min at 37°C. Rings were then embedded on the growth factor–reduced Matrigel supplemented with Medium 199, 1% fetal bovine serum, heparin (10 U/ml), antibiotics, and VEGF (50 ng/ml, Peprotech Inc.). Quantitative analysis of endothelial sprouting was performed using images from day 6, and sprout length was quantified in NIH Image program with a calibrated micrometer. The greatest distance from the aortic ring body to the end of the vascular sprouts was measured at three distinct points per ring and in three different rings per treatment group. Experiments were performed with aortic rings from six mice per group. The presence of endothelial cells in the sprouting microvessels was confirmed by Isolectin IB4 and Dil-Ac-LDL staining.

Surgical induction of hindlimb ischemia

The left femoral artery and vein were excised from the proximal portion of the femoral artery to the distal portion of the saphenous artery. The remaining arterial branches, including the perforator, were also excised. Blood flow was monitored with a laser Doppler blood flow (LDBF) analyzer (Moor LDI; Moor Instruments) before and 30 min after surgery and on postoperative days 7, 14, and 28. Hindlimb blood flow was expressed as the ratio of left (ischemic) to right (nonischemic) LDBF. Microcapillary density was measured with Alexa 568–linked Isolectin IB4 (Molecular Probe) (51). The clinical score after hindlimb ischemia was categorized at day 28 using the following criteria: 0, normal; 1, pale foot or gait abnormality; 2, gangrenous tissue in less than half the foot without lower limb necrosis; 3, gangrenous tissue in less than half the foot with lower limb necrosis; 4, gangrenous tissue in more than half the foot; 5, loss of half lower limb.

Model of ischemic stroke: middle cerebral artery occlusion

Transient intraluminal occlusion of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) was performed as described (55). Mice were anesthetized with 2% halothane in 70% nitrogen oxide and 30% oxygen and then maintained on 1% halothane in a similar gaseous mixture. Transient focal cerebral ischemia was performed by using an 8−0 nylon monofilament coated with silicone, which was introduced into the internal carotid artery via the external carotid artery and then advanced 10 mm distal to the carotid bifurcation to occlude the MCA. Laser Doppler flowmetry of cerebral blood flow was used to verify successful occlusion (<20% baseline value). The MCA was occluded for 2 hours followed by withdrawal of filament and reperfusion for 22 hours.

Cerebral infarct volume and neurological deficit score (NDS) were measured after reperfusion. Infarct area was measured in 2-mm–thick coronal brain sections stained with 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride and quantitated with an image-analysis system (Bioquant IV, R&M Biometrics, Nashville, TN). Cerebral infarct volume was determined by summing the infarcted areas. To eliminate the effects of edema, infarct size was also calculated as the (contralateral hemisphere – ipsilateral nonischemic hemisphere)/contralateral hemisphere. NDS was determined as follows: 0, no motor deficits (normal); 1, flexion of the contralateral torso and forelimb on lifting the animal by the tail (mild); 2, circling to the contralateral side but normal posture at rest (moderate); 3, leaning to the contralateral side at rest (severe); 4, no spontaneous movement (critical).

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. All data except neurologic deficit score were analyzed by means of Student's t test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Fisher exact test for post hoc analyses. Neurologic deficit score was analyzed by Mann-Whitney test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Materials for

Obesity Increases Vascular Senescence and Susceptibility to Ischemic Injury Through Chronic Activation of Akt and mTOR

Chao-Yung Wang, Hyung-Hwan Kim, Yukio Hiroi, Naoki Sawada, Salvatore Salomone, Laura E. Benjamin, Kenneth Walsh, Michael A. Moskowitz, James K. Liao*

*To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: jliao@rics.bwh.harvard.edu

Published 17 March 2009, Sci. Signal. 2, ra11 (2009) DOI: 10.1126/scisignal.2000143

This PDF file includes:

Fig. S1. Increased Akt and mTOR activation following a high-fat diet.

Fig. S2. Endothelial mitochondrial membrane potential.

Fig. S1. Increased Akt and mTOR activation following high-fat diet.

(A) Akt is activated to a greater extent after each high-fat diet meal. Aortic tissues were isolated from mice trained to receive 3 high-fat diet meals a day at 0, 6 or 12 hours. Akt phosphorylation was determined before (Pre) or after (Post) each meal. Each group contained 3 mice. *P<0.05 when compared to value at 0 hr. (B&C) Immunoblots showing time-dependent effects of high fat or chow diet on S6K phosphorylation and pS6K/S6K ratio following feeding at 8 and 20 weeks. *P<0.05 when compared to chow diet. Densitometric analyses of the ratio for each blot are shown in the bottom panels. Results are presented as mean ± SD. Each lane represents one or two mice. Each experiment was performed three times.

Fig. S2. Endothelial mitochondrial membrane potential.

Mitochondrial membrane potentials were analyzed in aortic endothelial cells from (A) WT, wild-type; STG, single transgenic mice (tet-myrAkt); DTG, double transgenic mice (VE-cadherin-tTA/tet-myrAkt) without induction and with short-term (ST) or long-term (LT) Akt induction. (*P<0.05 when compared to DTG and DTG-ST), (B) Double mutant Akt mice (DTG) with short-term (DTG-ST) or long-term Akt activation with vehicle (DTG-LT) or rapamycin (DTG-LT/Rapa) treatment (*P<0.05 when compared to DTG-LT, †P=0.23 when compared to DTG-ST) and (C) Chow diet or High fat diet fed mice receiving rapamycin or vehicle (control) treatment (**P<0.05 when compared to high fat fed group without rapamycin; †P=0.017 when compared to chow diet fed group). Experiments were performed three times using the fluorescence probe, tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE, Molecular probes).

Footnotes

www.sciencesignaling.org/cgi/content/full/2/62/ra11/DC1

Fig. S1. Increased Akt and mTOR activation following a high-fat diet.

Fig. S2. Endothelial mitochondrial membrane potential.

Citation: C.-Y. Wang, H.-H. Kim, Y. Hiroi, N. Sawada, S. Salomone, L. E. Benjamin, K. Walsh, M. A. Moskowitz, J. K. Liao, Obesity increases vascular senescence and susceptibility to ischemic injury through chronic activation of Akt and mTOR. Sci. Signal. 2, ra11 (2009).

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Hubert HB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, Castelli WP. Obesity as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease: A 26-year follow-up of participants in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1983;67:968–977. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.67.5.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castelli WP. Epidemiology of coronary heart disease: The Framingham study. Am. J. Med. 1984;76:4–12. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(84)90952-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campisi J. Replicative senescence: An old lives’ tale? Cell. 1996;84:497–500. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun P, Yoshizuka N, New L, Moser BA, Li Y, Liao R, Xie C, Chen J, Deng Q, Yamout M, Dong M-Q, Frangou CG, Yates JR, III, Wright PE, Han J. PRAK is essential for ras-induced senescence and tumor suppression. Cell. 2007;128:295–308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayashi T, Matsui-Hirai H, Miyazaki-Akita A, Fukatsu A, Funami J, Ding Q-F, Kamalanathan S, Hattori Y, Ignarro LJ, Iguchi A. Endothelial cellular senescence is inhibited by nitric oxide: Implications in atherosclerosis associated with menopause and diabetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:17018–17023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607873103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosso A, Balsamo A, Gambino R, Dentelli P, Falcioni R, Cassader M, Pegoraro L, Pagano G, Brizzi MF. p53 mediates the accelerated onset of senescence of endothelial progenitor cells in diabetes. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:4339–4347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509293200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fabrizio P, Pozza F, Pletcher SD, Gendron CM, Longo VD. Regulation of longevity and stress resistance by Sch9 in yeast. Science. 2001;292:288–290. doi: 10.1126/science.1059497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaeberlein M, Powers RW, III, Steffen KK, Westman EA, Hu D, Dang N, Kerr EO, Kirkland KT, Fields S, Kennedy BK. Regulation of yeast replicative life span by TOR and Sch9 in response to nutrients. Science. 2005;310:1193–1196. doi: 10.1126/science.1115535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dennis PB, Jaeschke A, Saitoh M, Fowler B, Kozma SC, Thomas G. Mammalian TOR: A homeostatic ATP sensor. Science. 2001;294:1102–1105. doi: 10.1126/science.1063518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cota D, Proulx K, Smith KA, Kozma SC, Thomas G, Woods SC, Seeley RJ. Hypothalamic mTOR signaling regulates food intake. Science. 2006;312:927–930. doi: 10.1126/science.1124147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho H, Mu J, Kim JK, Thorvaldsen JL, Chu Q, Crenshaw EB, III, Kaestner KH, Bartolomei MS, Shulman GI, Birnbaum MJ. Insulin resistance and a diabetes mellitus-like syndrome in mice lacking the protein kinase Akt2 (PKBβ). Science. 2001;292:1728–1731. doi: 10.1126/science.292.5522.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Um SH, Frigerio F, Watanabe M, Picard F, Joaquin M, Sticker M, Fumagalli S, Allegrini PR, Kozma SC, Auwerx J, Thomas G. Absence of S6K1 protects against age- and diet-induced obesity while enhancing insulin sensitivity. Nature. 2004;431:200–205. doi: 10.1038/nature02866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brunet A, Bonni A, Zigmond MJ, Lin MZ, Juo P, Hu LS, Anderson MJ, Arden KC, Blenis J, Greenberg ME. Akt promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a Forkhead transcription factor. Cell. 1999;96:857–868. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shiojima I, Walsh K. Role of Akt signaling in vascular homeostasis and angiogenesis. Circ. Res. 2002;90:1243–1250. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000022200.71892.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Datta SR, Brunet A, Greenberg ME. Cellular survival: A play in three Akts. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2905–2927. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guertin DA, Stevens DM, Thoreen CC, Burds AA, Kalaany NY, Moffat J, Brown M, Fitzgerald KJ, Sabatini DM. Ablation in mice of the mTORC components raptor, rictor, or mLST8 reveals that mTORC2 is required for signaling to Akt-FOXO and PKCα, but not S6K1. Dev. Cell. 2006;11:859–871. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frias MA, Thoreen CC, Jaffe JD, Schroder W, Sculley T, Carr SA, Sabatini DM. mSin1 is necessary for Akt/PKB phosphorylation, and its isoforms define three distinct mTORC2s. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:1865–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhaskar PT, Hay N. The two TORCs and Akt. Dev. Cell. 2007;12:487–502. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmelzle T, Hall MN. TOR, a central controller of cell growth. Cell. 2000;103:253–262. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeng Z, Sarbassov DD, Samudio IJ, Yee KW, Munsell MF, Ellen Jackson C, Giles FJ, Sabatini DM, Andreeff M, Konopleva M. Rapamycin derivatives reduce mTORC2 signaling and inhibit AKT activation in AML. Blood. 2007;109:3509–3512. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-030833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sengupta S, Sheen JH, Hsu PP, Bagley AF, Markhard AL, Sabatini DM. Prolonged rapamycin treatment inhibits mTORC2 assembly and Akt/PKB. Mol. Cell. 2006;22:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phung TL, Ziv K, Dabydeen D, Eyiah-Mensah G, Riveros M, Perruzzi C, Sun J, Monahan-Earley RA, Shiojima I, Nagy JA, Lin MI, Walsh K, Dvorak AM, Briscoe DM, Neeman M, Sessa WC, Dvorak HF, Benjamin LE. Pathological angiogenesis is induced by sustained Akt signaling and inhibited by rapamycin. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Altomare DA, Guo K, Cheng JQ, Sonoda G, Walsh K, Testa JR. Cloning, chromosomal localization and expression analysis of the mouse Akt2 oncogene. Oncogene. 1995;11:1055–1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ackah E, Yu J, Zoellner S, Iwakiri Y, Skurk C, Shibata R, Ouchi N, Easton RM, Galasso G, Birnbaum MJ, Walsh K, Sessa WC. Akt1/protein kinase Bα is critical for ischemic and VEGF-mediated angiogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:2119–2127. doi: 10.1172/JCI24726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dimmeler S, Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, Hermann C, Busse R, Zeiher AM. Activation of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells by Akt-dependent phosphorylation. Nature. 1999;399:601–605. doi: 10.1038/21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fulton D, Gratton J-P, McCabe TJ, Fontana J, Fujio Y, Walsh K, Franke TF, Papapetropoulos A, Sessa WC. Regulation of endothelium-derived nitric oxide production by the protein kinase Akt. Nature. 1999;399:597–601. doi: 10.1038/21218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mukai Y, Rikitake Y, Shiojima I, Wolfrum S, Satoh M, Takeshita K, Hiroi Y, Salomone S, Kim H-H, Benjamin LE, Walsh K, Liao JK. Decreased vascular lesion formation in mice with inducible endothelial-specific expression of protein kinase Akt. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:334–343. doi: 10.1172/JCI26223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lohi H, Ianzano L, Zhao X-C, Chan EM, Turnbull J, Scherer SW, Ackerley CA, Minassian BA. Novel glycogen synthase kinase 3 and ubiquitination pathways in progressive myoclonus epilepsy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:2727–2736. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alexander K, Hinds PW. Requirement for p27KIP1 in retinoblastoma protein-mediated senescence. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:3616–3631. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.11.3616-3631.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyauchi H, Minamino T, Tateno K, Kunieda T, Toko H, Komuro I. Akt negatively regulates the in vitro lifespan of human endothelial cells via a p53/p21-dependent pathway. EMBO J. 2004;23:212–220. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janzen V, Forkert R, Fleming HE, Saito Y, Waring MT, Dombkowski DM, Cheng T, DePinho RA, Sharpless NE, Scadden DT. Stem-cell ageing modified by the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16INK4a. Nature. 2006;443:421–426. doi: 10.1038/nature05159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Braig M, Lee S, Loddenkemper C, Rudolph C, Peters AH, Schlegelberger B, Stein H, Dörken B, Jenuwein T, Schmitt CA. Oncogene-induced senescence as an initial barrier in lymphoma development. Nature. 2005;436:660–665. doi: 10.1038/nature03841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen J, Somanath PR, Razorenova O, Chen WS, Hay N, Bornstein P, Byzova TV. Akt1 regulates pathological angiogenesis, vascular maturation and permeability in vivo. Nat. Med. 2005;11:1188–1196. doi: 10.1038/nm1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 2005;307:1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sabatini DM, Barrow RK, Blackshaw S, Burnett PE, Lai MM, Field ME, Bahr BA, Kirsch J, Betz H, Snyder SH. Interaction of RAFT1 with gephyrin required for rapamycin-sensitive signaling. Science. 1999;284:1161–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5417.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brunn GJ, Hudson CC, Sekulić A, Williams JM, Hosoi H, Houghton PJ, Lawrence JC, Jr., Abraham RT. Phosphorylation of the translational repressor PHAS-I by the mammalian target of rapamycin. Science. 1997;277:99–101. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen WS, Xu P-Z, Gottlob K, Chen M-L, Sokol K, Shiyanova T, Roninson I, Weng W, Suzuki R, Tobe K, Kadowaki T, Hay N. Growth retardation and increased apoptosis in mice with homozygous disruption of the akt1 gene. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2203–2208. doi: 10.1101/gad.913901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cho H, Thorvaldsen JL, Chu Q, Feng F, Birnbaum MJ. Akt1/PKBα is required for normal growth but dispensable for maintenance of glucose homeostasis in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:38349–38352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100462200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hemmings BA. Akt signaling: Linking membrane events to life and death decisions. Science. 1997;275:628–630. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishi J-I, Minamino T, Miyauchi H, Nojima A, Tateno K, Okada S, Orimo M, Moriya J, Fong G-H, Sunagawa K, Shibuya M, Komuro I. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 regulates postnatal angiogenesis through inhibition of the excessive activation of Akt. Circ. Res. 2008;103:261–268. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.174128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herbig U, Ferreira M, Condel L, Carey D, Sedivy JM. Cellular senescence in aging primates. Science. 2006;311:1257. doi: 10.1126/science.1122446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fernández-Hernando C, Ackah E, Yu J, Suárez Y, Murata T, Iwakiri Y, Prendergast J, Miao RQ, Birnbaum MJ, Sessa WC. Loss of akt1 leads to severe atherosclerosis and occlusive coronary artery disease. Cell Metab. 2007;6:446–457. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang C-Y, Wen M-S, Wang H-W, Hsieh I-C, Li Y, Liu P-Y, Lin F-C, Liao JK. Increased vascular senescence and impaired endothelial progenitor cell function mediated by mutation of circadian gene Per2. Circulation. 2008;118:2166–2173. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.790469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin DE, Hall MN. The expanding TOR signaling network. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2005;17:158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li W, Petrimpol M, Molle KD, Hall MN, Battegay EJ, Humar R. Hypoxia-induced endothelial proliferation requires both mTORC1 and mTORC2. Circ. Res. 2007;100:79–87. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000253094.03023.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hietakangas V, Cohen SM. Re-evaluating AKT regulation: Role of TOR complex 2 in tissue growth. Genes Dev. 2007;21:632–637. doi: 10.1101/gad.416307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kenyon C. The plasticity of aging: Insights from long-lived mutants. Cell. 2005;120:449–460. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li X, Monks B, Ge Q, Birnbaum MJ. Akt/PKB regulates hepatic metabolism by directly inhibiting PGC-1α transcription coactivator. Nature. 2007;447:1012–1016. doi: 10.1038/nature05861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Handschin C, Spiegelman BM. The role of exercise and PGC1α in inflammation and chronic disease. Nature. 2008;454:463–469. doi: 10.1038/nature07206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Handschin C, Spiegelman BM. Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor γ coactivator 1 coactivators, energy homeostasis, and metabolism. Endocr. Rev. 2006;27:728–735. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takeshita K, Satoh M, Ii M, Silver M, Limbourg FP, Mukai Y, Rikitake Y, Radtke F, Gridley T, Losordo DW, Liao JK. Critical role of endothelial Notch1 signaling in postnatal angiogenesis. Circ. Res. 2007;100:70–78. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000254788.47304.6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cristofalo VJ, Allen RG, Pignolo RJ, Martin BG, Beck JC. Relationship between donor age and the replicative lifespan of human cells in culture: A reevaluation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:10614–10619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Narita M, Nuñez S, Heard E, Narita M, Lin AW, Hearn SA, Spector DL, Hannon GJ, Lowe SW. Rb-mediated heterochromatin formation and silencing of E2F target genes during cellular senescence. Cell. 2003;113:703–716. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00401-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Satoh M, Ogita H, Takeshita K, Mukai Y, Kwiatkowski DJ, Liao JK. Requirement of Rac1 in the development of cardiac hypertrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:7432–7437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510444103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hiroi Y, Kim H-H, Ying H, Furuya F, Huang Z, Simoncini T, Noma K, Ueki K, Nguyen N-H, Scanlan TS, Moskowitz MA, Cheng S-Y, Liao JK. Rapid nongenomic actions of thyroid hormone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:14104–14109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601600103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.This work was support by grants from the NIH (HL052233, HL080187, and NS010828) and the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CMRPG370811). There are no disclosures or conflicts regarding this work for all of the authors.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials for

Obesity Increases Vascular Senescence and Susceptibility to Ischemic Injury Through Chronic Activation of Akt and mTOR

Chao-Yung Wang, Hyung-Hwan Kim, Yukio Hiroi, Naoki Sawada, Salvatore Salomone, Laura E. Benjamin, Kenneth Walsh, Michael A. Moskowitz, James K. Liao*

*To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: jliao@rics.bwh.harvard.edu

Published 17 March 2009, Sci. Signal. 2, ra11 (2009) DOI: 10.1126/scisignal.2000143

This PDF file includes:

Fig. S1. Increased Akt and mTOR activation following a high-fat diet.

Fig. S2. Endothelial mitochondrial membrane potential.

Fig. S1. Increased Akt and mTOR activation following high-fat diet.

(A) Akt is activated to a greater extent after each high-fat diet meal. Aortic tissues were isolated from mice trained to receive 3 high-fat diet meals a day at 0, 6 or 12 hours. Akt phosphorylation was determined before (Pre) or after (Post) each meal. Each group contained 3 mice. *P<0.05 when compared to value at 0 hr. (B&C) Immunoblots showing time-dependent effects of high fat or chow diet on S6K phosphorylation and pS6K/S6K ratio following feeding at 8 and 20 weeks. *P<0.05 when compared to chow diet. Densitometric analyses of the ratio for each blot are shown in the bottom panels. Results are presented as mean ± SD. Each lane represents one or two mice. Each experiment was performed three times.

Fig. S2. Endothelial mitochondrial membrane potential.

Mitochondrial membrane potentials were analyzed in aortic endothelial cells from (A) WT, wild-type; STG, single transgenic mice (tet-myrAkt); DTG, double transgenic mice (VE-cadherin-tTA/tet-myrAkt) without induction and with short-term (ST) or long-term (LT) Akt induction. (*P<0.05 when compared to DTG and DTG-ST), (B) Double mutant Akt mice (DTG) with short-term (DTG-ST) or long-term Akt activation with vehicle (DTG-LT) or rapamycin (DTG-LT/Rapa) treatment (*P<0.05 when compared to DTG-LT, †P=0.23 when compared to DTG-ST) and (C) Chow diet or High fat diet fed mice receiving rapamycin or vehicle (control) treatment (**P<0.05 when compared to high fat fed group without rapamycin; †P=0.017 when compared to chow diet fed group). Experiments were performed three times using the fluorescence probe, tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE, Molecular probes).