Abstract

A case of maxillofacial zygomycosis caused by Mucor circinelloides, identified by phenotypic and molecular methods and treated successfully with liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome) and surgical debridement, is described. The isolate was resistant to posaconazole. This report underscores the importance of prior susceptibility testing of zygomycetes to guide therapy with the most effective antifungal agent for an improved prognosis.

CASE REPORT

A 40-year-old male motor mechanic was referred to the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Unit, Farwanya Hospital, Kuwait, by his dentist in the middle of March 2007. He presented with a nonhealing extraction wound on the right maxilla. About 2 months previously, he underwent an extraction procedure in his native country for teeth 24 and 25 due to pain and mobility. Although the extraction procedure was reported to be quick and uneventful, the patient subsequently developed swelling and pain, which led to systemic anti-inflammatory treatment, but the symptoms persisted. A closer examination of the lesion revealed soft-tissue necrosis and bone involvement extending into the adjacent maxillary area. The patient history revealed no recognizable abnormality except that he was found to be diabetic, with a blood glucose level ranging between 7.9 and 8.6 mmol/liter during hospitalization. He was maintained on metformin (Glucophage) for control of his diabetes. The initial diagnostic procedures included plain X-ray and bone scintigraphy, which revealed considerable local pathology and bone involvement. At this stage, the patient was subjected to explorative antrostomy and alveolar resection under general anesthesia. Necrotic bone and surrounding soft tissues were removed, and the maxillary sinus was left wide open. Two specimens (a portion of the maxilla and adherent soft tissue) were sent to the Mycology Reference Laboratory, Faculty of Medicine, for fungal investigations. The direct microscopic examination of the digested tissue in 10% potassium hydroxide mounts with and without calcofluor (0.1%) revealed broad, sparsely septate hyphae suggestive of a zygomycotic infection. A fast-growing mold grew from the biopsy material on Sabouraud dextrose agar (Difco Becton Dickinson & Company, Sparks, MD) plates, which was provisionally identified as a Mucor species. No significant bacterial pathogens warranting treatment were grown from the biopsy material. The patient was readmitted for a complex treatment regimen, which started with an intensive preoperative antifungal course of liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome) (Gilead, Cambridge, United Kingdom) with a dose of 5 mg/kg of body weight for 2 weeks. After this course, radical surgery was performed, which included a maxillectomy and resection of the orbital floor of the right side up to the margins of the healthy tissue. The repeat sampling, comprising a portion of maxillary bone and adherent soft tissue, also demonstrated fungal hyphae and yielded the same fungus in culture, thus confirming the previous observations. After a short recovery period of 5 days, the patient was again started on liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg) treatment. Since there was evidence of partial kidney toxicity, the amphotericin B dose was reduced to 2.5 mg/kg, coupled with local instillation of amphotericin B (150 μg/ml). This postoperative course of amphotericin B lasted for 3 weeks. The postoperative local defect was covered by a temporal palatal plane splint. The patient made a good recovery, and there was no recurrence during 6 months of follow-up.

Mycological identification and antifungal susceptibility.

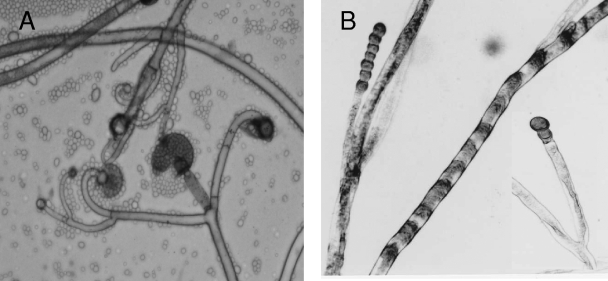

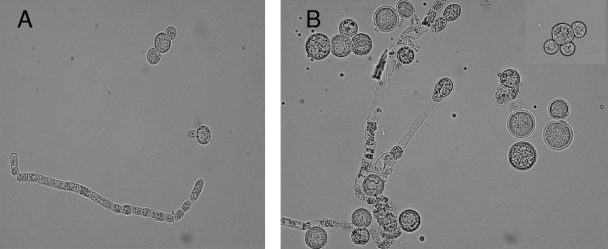

The isolate (accession no. 1378/07) cultured from debrided maxillary tissue yielded a fast-growing mold on Sabouraud dextrose agar. On the basis of microscopic morphology, it was provisionally identified as a Mucor species. After 3 days of incubation on potato dextrose agar (PDA) (Difco Becton Dickinson & Company), the growth attained a diameter of 8.2 cm at 30°C and 6.0 cm at 37°C, with no growth at 40°C. Colonies on PDA at 30°C were initially yellowish and became yellowish brown on aging. Microscopic examination revealed globose yellowish brown sporangia, measuring 30 to 67 μm in diameter (Fig. 1). Columellae were subglobose to pyriform and about 35 μm wide. Collars were seen. Sporangiophores were either long and erect or short with slightly recurved (circinate) lateral branches, characterizing the species as Mucor circinelloides (Fig. 1A). Sporangiospores were hyaline and ellipsoidal to obovoidal and measured 4.0 to 7.0 μm in length and 3.5 to 5.0 μm in width. Chains of thick-walled intercalary and terminal chlamydospores were produced (Fig. 1B). The identity of the isolate as M. circinelloides was also supported by its ability to convert into yeast forms when grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Difco Becton Dickinson & Company) in shake cultures for 4 to 5 days at 37°C (Fig. 2A and B). The isolate was found to be completely resistant (MIC > 32 μg/ml) to posaconazole, voriconazole, and caspofungin (MIC > 32 μg/ml) but susceptible to amphotericin B (0.023 μg/ml) as determined by Etest on RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2% glucose at both a 24-h and 48-h reading.

FIG. 1.

(A) Branched circinate sporangiophores, sporangia, and collumellae; (B) chlamydospores of M. circinelloides formed successively in chains. Magnification, ×400.

FIG. 2.

(A and B) Growth of M. circinelloides in BHI agar at 37°C, showing hyphae with arthroconidium formation and yeast forms with single, bipolar, and multipolar buds. Magnification, ×600.

Molecular identification.

The DNA from the maxillary biopsy and from culture isolated from the biopsy material was prepared as described previously (3) and was used as a template in PCR amplification. The internally transcribed spacer (ITS) region of ribosomal DNA (rDNA) containing the ITS-1, 5.8S rRNA, and the ITS-2 was amplified by using the ITS1 and ITS4 primers, while the D1/D2 region of the 28S rRNA gene was amplified by using the NL-1 and NL-4 primers, as described previously (2, 18). Both strands of amplified DNA were sequenced as described previously (2, 18). The sequencing primers, in addition to the amplification primers, included ITS1FS, ITS2, ITS3, and ITS4RS for the ITS region and NL-2A, NL-3A, and NLR3R (18), and at least two reactions were carried out for each primer. Reverse complements were generated using the Bioinformatics site (http://www.bioinformatics.org/sms/rev_comp.html) and aligned with forward sequences using ClustalW (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/clustalw/index.html). GenBank basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) searches (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) were performed for species identification. An amplicon of ∼600 bp obtained for the ITS region was sequenced, and the BLAST search revealed complete identity (100%) in the ITS-1 and ITS-2 regions with the corresponding sequences available in the data bank from two reference strains, CBS108.16 (GenBank accession no. AF412286) and CNRMA 04.805 (GenBank accession no. DQ118990) of M. circinelloides. Similarly, an amplicon of ∼700 bp obtained for the D1/D2 region was sequenced, and the BLAST search revealed nearly complete identity (one or two nucleotide differences) with the corresponding sequences available in the data bank from two strains, IFM 40507 (GenBank accession no. AB363774) and UWFP 1079 (GenBank accession no. AY213710) of M. circinelloides. Based on the above data and the observations made previously that the strains belonging to the same fungal species have >99% nucleotide identity in the ITS-1 and ITS-2 regions as well as the D1/D2 regions of rDNA (18, 30, 33), the molecular identity of our isolate is described as M. circinelloides.

Conclusions.

The case described here is noteworthy in several respects; first, the etiologic role of M. circinelloides in invasive maxillofacial zygomycosis has been unequivocally established for the first time by identifying the isolate using phenotypic and molecular methods; second, the site of initiation of infection was oral following the tooth extraction and not the nasal/paranasal sinuses as has been the case in most of the reported instances; third, the patient was apparently healthy and was occupationally functional; and fourth, the isolate was found to be completely resistant to posaconazole. The report underscores the emerging role of M. circinelloides in invasive zygomycosis and cautions about the therapeutic use of posaconazole without prior susceptibility testing. The patient was successfully treated with a lipid formulation of amphotericin B and complete debridement of the infected tissue.

A review of the literature revealed only eight cases of zygomycosis in adults caused by M. circinelloides (Table 1). Six of the cases with cutaneous or subcutaneous involvement were either known or suspected to have sustained trauma (Table 1). Hematological malignancy was the underlying disease in four cases (acute myelocytic leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome in two patients each) (6, 12, 15, 31), one had multiple underlying conditions (insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus with metabolic acidosis, alcoholism, cirrhosis, and corticosteroid treatment) (24), and one had short gut syndrome with multiple surgical interventions (7). Two of the patients had no recognizable underlying condition (11a, 40). Our patient was a 40-year-old man who apparently had no underlying disease except non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, which is a frequently associated condition among patients developing zygomycosis, particularly the rhinocerebral form of the disease (20). However, diabetes mellitus in our patient was well controlled by oral antidiabetics, and the patient was apparently healthy and occupationally functional.

TABLE 1.

Salient findings in eight published cases caused by Mucor circinelloidesa

| Case no. | Age, sex | Predisposition | Underlying disease | Affected site | Diagnosis | Treatment | Outcome | Comment | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NA | i.v. drug abuser | None | Cutaneous injection site | Culture | Amphotericin B, debridement | Resolved | None | 12 |

| 2 | 34, F | Farmer, trauma? | None | Dorsum, rt. hand, localized | Histopathology, culture | None | Remained localized, self-healed | 17 yr to develop | 41 |

| 3 | 63, M | Barrier breakage, Steroid treatment | DMID, cirrhosis, alcoholism | Cutaneous/ subcutaneous | Histopathology, culture | Amphotericin B, debridement | Died, septic shock | None | 25 |

| 4 | 23, F | Trauma, Insect bite? | AML, neutropenia of <500 cells/ml | Several cutaneous lesions | Histopathology, culture | Amphotericin B (1 mg/kg, 10 days; 3 1/2 mg/kg every other day) | Resolved | M. circinelloides isolated from nasal swabs | 13 |

| 5 | 62, F | Trauma | MDS | Forearm, black scar | Histopathology, culture | Debridement | Resolved; died due to malignancy | None | 6 |

| 5 | 48, M | Abdominal surgery, TPN | Short gut syndrome | Blood | Culture from blood, CVC | Liposomal amphotericin B, fluconazole, CVC removal | Resolved | Concomitant C. albicans fungemia | 7 |

| 6 | 59, M | Voriconazole prophylaxis | AML, GVHD | Pulmonary | Sputum culture | Amphotericin B | Died, massive hemoptysis | Aspergillosis, treated with amphotericin B + micafungin | 32 |

| 8 | 90, M | Trauma, while trimming shrubs | MDS, DMID, pancytopenia | Cutaneous, leg lesion | Histopathology, culture | Amphotericin B (Abelcet) (5 mg/kg), debridement | Resolved | Chlamydospores in skin lesions | 16 |

Abbreviations: F, female; M, male; i.v., intravenous; DMID, diabetes mellitus, insulin dependent; AML, acute myelogenous leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; rt., right; TPN, total parenteral nutrition; CVC, central venous catheter; NA, not available.

Several species of zygomycetes belonging to the order Mucorales are associated with human infections. Some of these species are recognized pathogens, while others are emerging or reemerging (8, 14, 16). Their properties of angioinvasiveness, thermotolerance, and rapidity of growth make them unique among filamentous fungi in causing a rapidly fulminating disease in human hosts (27). In an excellent retrospective review of 929 published cases of zygomycosis, the species belonging to the genus Rhizopus were isolated from 47% of culture-proven cases. The Mucor species were isolated from another 18% cases, whereas Cunninghamella bertholletiae, Apophysomyces elegans, Absidia species, Saksenaea species, and Rhizomucor pusillus were isolated from only 4% to 7% of the cases (28). Although the genus Mucor comprises more than 50 validly described species, only a few are known to be pathogenic for humans. These include Mucor circinelloides, Mucor indicus (Mucor rouxianus), and Mucor ramosissimus (8, 27).

In most of the diagnostic laboratories, species-level identification of zygomycetes is not undertaken due to a lack of expertise (or the diagnosis is based on histopathologic evidence alone in the absence of culture results). Therefore, the exact frequency for each species involved in human infections remains unknown. Perhaps due to these reasons, M. circinelloides has rarely been described as an etiologic agent of zygomycosis, although Mucor species have been associated with a variety of invasive diseases. Even the identification of the isolates to the species level by morphology alone may not be reliable (19). To overcome this limitation, molecular techniques are now being increasingly applied to identify zygomycetes in grown cultures (15, 39). Consistent with this approach, we identified our isolate by DNA sequencing of rDNA, thus validating the morphological/physiologic identification features, such as the ability to grow at 37°C, the presence of intercalary and terminal chlamydospores forming successively in chains, the ability to undergo mold-yeast conversion in BHI broth at 37°C, producing unipolar, bipolar, and multipolar budding forms, and the presence of circinate conidiophores—a hallmark of its morphological identification (22).

While zygomycetes are known to differ in their virulence potential (27), it is not clear if there are also host-related interspecies preferences determined by underlying risk factors. The optimum growth temperature of M. circinelloides is about 30°C, which makes it less virulent than some other species of zygomycetes, particularly those belonging to the genus Rhizopus. Of the eight cases of M. circinelloides summarized in Table 1, six had cutaneous or subcutaneous involvement, probably a reflection of the limited ability of this species to cause deep-seated infection where the temperature is higher than the cutaneous or peripheral sites. In this context, our case and the one described by Shindo et al. (31) are notable since this species caused deep-seated infection involving maxillary tissue (including bones) and lungs, respectively. There are very few reports of zygomycosis secondary to use of unsterile instruments in the oral cavity by nonqualified practitioners (9). This also appears to be the case for our patient. Although speculative, another possible source of infection in our patient could be related to the consumption of dates following tooth extraction. The dates are grown and eaten quite frequently in the Middle East, and a recent report suggests that dates could serve as a natural substrate for M. circinelloides (Y. A. M. H. Gherbawy et al., unpublished data under GenBank entry AM933552).

Posaconazole has a broad-spectrum of in vitro activity against yeasts, dimorphic fungi, and molds, including zygomycetes (23, 36), and it has been successfully used in primary and salvage therapy for invasive zygomycosis (11, 23, 25). In fact, we seriously considered using posaconazole as a primary therapy in the present case. However, since this drug was not available in the pharmacy, we used liposomal amphotericin B. A review of the antifungal susceptibility data indicates that Mucor species are relatively less susceptible to posaconazole than species of some other genera within the zygomycetes (Table 2). Recently Torres-Narbona et al. (36) compared in vitro activities of posaconazole against 45 clinical isolates of zygomycetes that belonged to six different genera. Mucor species showed much higher MICs at which 90% of organisms were inhibited (2 μg/ml) than species belonging to other genera (0.5 to 1.0 μg/ml). Similar observations were made by Almyroudis et al. (4). In that study, while 14 of 20 Mucor species isolates were considered susceptible (MIC ≤ 0.5 μg/ml) to posaconazole, all three isolates of M. circinelloides were found to be resistant, with a MIC range of 1 to 2 μg/ml. As yet, there are no CLSI approved interpretive susceptibility breakpoints available for posaconazole for either yeasts or molds.

TABLE 2.

In vitro activities of posaconazole against Rhizopus and Mucor species

| Genus/species (na) | Method (CLSI) | Reading time point(s) (h) | MIC (μg/ml)

|

Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 90% | GMc | ||||

| Rhizopus spp. (10) | M38-P | 48 | 0.25-8 | 8.0 | 2.73 | 35 |

| Mucor spp. (7) | M38-P | 48 | 0.125-8 | 1.0 | 1.54 | 35 |

| Rhizopus spp. (15) | M38-P | 48 | 0.125-1 | 0.50 | 0.27 | 10 |

| Mucor spp. (6) | M38-P | 48 | 0.5-2 | ND | 1.15 | 10 |

| Rhizopus spp. (66) | M38-A | 48 | 0.06-4 | 1.0 | ND | 4 |

| Mucor spp. (20) | M38-A | 48 | 0.06-2 | 2.0 | ND | 4 |

| Mucor circinelloides (3b) | M38-A | 48 | 1-2 | ND | ND | 4 |

| Rhizopus spp. (11) | M38-A | 24 | 0.125-1 | 0.5 | ND | 37 |

| 48 | 0.25->16 | 1.0 | ND | |||

| Mucor spp. (19) | M38-A | 24 | 0.25-2 | 2.0 | ND | 37 |

| 48 | 0.25->16 | 2.0 | ND | |||

n, no. of isolates.

All three isolates were considered resistant to posaconazole, with a suggested MIC breakpoint of >1 μg/ml.

GM, geometric mean.

Currently, the major role of posaconazole in clinical practice is in prophylaxis of neutropenic patients with a significant risk for infections with filamentous fungi. Whether the reduced susceptibility of M. circinelloides to posaconazole could contribute to the emergence of this species as an agent of breakthrough zygomycosis is yet to be documented. If this happens, the situation would be analogous to cases of breakthrough zygomycosis occurring in patients receiving voriconazole prophylaxis or treatment for the control of invasive aspergillosis (19, 21, 31). In view of the differences in susceptibilities of zygomycetes to antifungal agents (4, 34), it is important to perform in vitro susceptibility testing prior to initiating therapy. However, it may not always be feasible in cases of zygomycosis, where a majority of specimens positive by direct microscopic examination fail to yield the etiologic species in culture (35). The precise reason for this discrepancy is unclear, but it is believed that fungi probably die during culture procedures, particularly when tissue is homogenized (26, 32). This may be more applicable to zygomycetes, which possess much broader hyphal structures that are susceptible to rupture. In such cases where cultures are negative, the characteristic tissue morphology of zygomycetes may help in the diagnosis. However, it does not solve the therapeutic dilemma the clinicians are faced with while deciding to choose the most effective antifungal agent. In recent years, application of molecular methods has provided alternative diagnostic tools which have been used for species-specific identification of the etiologic fungus even in the absence of a positive culture (1, 5, 17, 30). We have used this approach for confirming the identity of our isolate as M. circinelloides.

With the background of increasing reports of breakthrough zygomycosis in patients receiving voriconazole (21, 37) and the recommended use of posaconazole as a prophylaxis and salvage therapy in refractory cases (13, 29, 38) and more recently even for primary therapy (25), the present report assumes considerable significance. Since Mucor species are relatively less susceptible to posaconazole (4) and the M. circinelloides isolate in our case was completely resistant to this agent, this report underscores the importance of prior antifungal susceptibility testing to guide specific therapy for zygomycosis.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The DNA sequence data of our isolate have been deposited in the EMBL data bank under accession no. AM745433 and FM246460.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the excellent technical support of Leena Joseph, Daad Farhat, and Salwa Al-Hajri in the identification of the fungal isolate described in this publication.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 January 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmad, S., Z. Khan, A. S. Mustafa, and Z. U. Khan. 2002. Seminested PCR for diagnosis of candidemia: comparison with culture, antigen detection, and biochemical methods for species identification. J. Clin. Microbiol. 402483-2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmad, S., M. Al-Mahmeed, and Z. U. Khan. 2005. Characterization of Trichosporon species isolated from clinical specimens in Kuwait. J. Med. Microbiol. 54639-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmad, S., Z. U. Khan, and A. M. Theyyathel. 2007. Value of Aspergillus terreus-specific DNA, (1-3)-β-D-glucan and galactomannan detection in serum and bronchoalveolar lavage specimens of experimentally infected mice. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 59165-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almyroudis, N. G., D. A. Sutton, A. W. Fothergill, M. G. Rinaldi, and S. Kusne. 2007. In vitro susceptibilities of 217 clinical isolates of zygomycetes to conventional and new antifungal agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 512587-2590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borman, A. M., C. J. Linton, S. J. Miles, and E. M. Johnson. 2008. Molecular identification of pathogenic fungi. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61(Suppl. 1)i7-i12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandra, S., and A. Woodgyer. 2002. Primary cutaneous zygomycosis due to Mucor circinelloides. Australas. J. Dermatol. 4339-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan-Tack, K. M., L. L. Nemoy, and E. N. Perencevich. 2005. Central venous catheter-associated fungemia secondary to mucormycosis. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 37925-927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chayakulkeeree, M., M. A. Ghannoum, and J. R. Perfect. 2006. Zygomycosis: the re-emerging fungal infection. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 25215-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chopra, H., K. Dua, S. Bhatia, N. Dua, and V. Mittal. 13 August 2008, posting date. Invasive rhino-orbital fungal sinusitis following dental manipulation. Mycoses. [Epub ahead of print.] doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01600.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Dannaoui, E., J. Meletiadis, J. W. Mouton, J. F. Meis, P. E. Verweij, and Eurofung Network. 2003. In vitro susceptibilities of zygomycetes to conventional and new antifungals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 5145-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferguson, T. D., S. D. Schniederjan, J. Dionne-Odom, M. E. Brandt, M. G. Rinaldi, F. S. Nolte, A. Langston, and S. M. Zimmer. 2007. Posaconazole treatment for Apophysomyces elegans rhino-orbital zygomycosis following trauma for a male with well-controlled diabetes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 451648-1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11a.Fetchick, R. J., M. G. Rinaldi, and S. H. Sun. 1986. Zygomycosis due to Mucor circinelloides, a rare agent of human fungal diseases, abstr. F-42, p. 404. Abstr. Annu. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 12.Fingeroth, J. D., R. S. Roth, J. A. Talcott, and M. G. Rinaldi. 1994. Zygomycosis due to Mucor circinelloides in a neutropenic patient receiving chemotherapy for acute myelogenous leukemia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 19135-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenberg, R. N., K. Mullane, J. A. van Burik, L. Raad, M. J. Abzug, G. Anstead, R. Herbrecht, A. Langston, K. A. Marr, G. Schiller, M. Schuster, J. R. Wingard, C. E. Gonzalez, S. G. Revankar, G. Corcoran, R. J. Kryscio, and R. Hare. 2006. Posaconazole as salvage therapy for zygomycosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50126-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenberg, R. N., L. J. Scott, H. H. Vaughn, and J. A. Ribes. 2004. Zygomycosis (mucormycosis): emerging clinical importance and new treatments. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 17517-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iwen, P. C., L. Sigler, R. K. Noel, and A. G. Freifeld. 2007. Mucor circinelloides was identified by molecular methods as a cause of primary cutaneous zygomycosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45636-640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kauffman C. A. 2004. Zygomycosis: reemergence of an old pathogen. 39588-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan, Z. U., S. Ahmad, E. Mokaddas, T. Said, M. P. Nair, M. A. Halim, M. R. Nampoory, and M. R. McGinnis. 2007. Cerebral aspergillosis diagnosed by detection of Aspergillus flavus-specific DNA, galactomannan and (1→3)-beta-D-glucan in clinical specimens. J. Med. Microbiol. 56129-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan, Z. U., S. Ahmad, E. Mokaddas, R. Chandy, J. Cano, and J. Guarro. 2008. Actinomucor elegans var. kuwaitiensis isolated from the wound of a diabetic patient. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 94343-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kontoyiannis, D. P., M. S. Lionakis, R. E. Lewis, G. Chamilos, M. Healy, C. Perego, A. Safdar, H. Kantarjian, R. Champlin, T. J. Walsh, and I. I. Raad. 2005. Zygomycosis in a tertiary-care cancer center in the era of Aspergillus-active antifungal therapy: a case-control observational study of 27 recent cases. J. Infect. Dis. 1911350-1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kontoyiannis, D. P., and R. E. Lewis. 2006. Invasive zygomycosis: update on pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and management. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 20581-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marty, F. M., L. A. Cosimi, and L. R. Baden. 2004. Breakthrough zygomycosis after voriconazole treatment in recipients of hematopoietic stem-cell transplants. N. Engl. J. Med. 350950-952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McIntyre, M., J. Baum, J. Arnau, and J. Nielsen. 2002. Growth physiology and dimorphism of Mucor circinelloides (syn. racemosus) during submerged batch cultivation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 58495-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagappan, V., and S. Deresinski. 2007. Reviews of anti-infective agents: posaconazole: a broad-spectrum triazole antifungal agent. Clin. Infect. Dis. 451610-1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palacio, A. D., M. J. Ramos, A. Perez, A. Arribi, I. Amondarian, S. Alonso, and Y. M. Cru Ortiz. 1999. Zigomicosis. Aprospito de cinco casos. Rev. Iberaom. Micol. 1650-56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peel, T., J. Daffy, K. Thursky, P. Stanley, and K. Buising. 2008. Posaconazole as first line treatment for disseminated zygomycosis. Mycoses 51542-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pyrgos, V., S. Shoham, and T. J. Walsh. 2008. Pulmonary zygomycosis. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 29111-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ribes, J. A., C. L Vanover-Sams, and D. J. Baker. 2000. Zygomycetes in human disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13236-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roden, M. M., T. E. Zaoutis, W. L. Buchanan, T. A. Knudsen, T. A. Sarkisova, R. L. Schaufele, M. Sein, T. Sein, C. C. Chiou, J. H. Chu, D. P. Kontoyiannis, and T. J. Walsh. 2005. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41634-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rogers, T. R. 2008. Treatment of zygomycosis: current and new options. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61(Suppl. 1)i35-i40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwarz, P., S. Bretagne, J. C. Gantier, D. Garcia-Hermoso, O. Lortholary, F. Dromer, and E. Dannaoui. 2006. Molecular identification of zygomycetes from culture and experimentally infected tissues. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44340-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shindo, M., K. Sato, J. Jimbo, T. Hosoki, K. Ikuta, A. Sano, K. Nishimura, Y. Torimoto, and Y. Kohgo. 2007. Breakthrough pulmonary mucormycosis during voriconazole treatment after reduced-intensity cord blood transplantation for a patient with acute myeloid leukemia. Rinsho Ketsueki 48412-417. (In Japanese.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spellberg, B., J. Edwards, Jr., and A. Ibrahim. 2005. Novel perspectives on mucormycosis: pathophysiology, presentation, and management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18556-569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sugita, T., A. Nishikawa, R. Ikeda, and T. Shinoda. 1999. Identification of medically relevant Trichosporon species based on sequences of internal transcribed spacer regions and construction of a database for Trichosporon identification. J. Clin. Microbiol. 371985-1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun, Q. N., A. W. Fothergill, D. L. McCarthy, M. G. Rinaldi, and J. R. Graybill. 2002. In vitro activities of posaconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, amphotericin B, and fluconazole against 37 clinical isolates of zygomycetes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 461581-1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tarrand, J. J., M. Lichterfeld, I. Warraich, M. Luna, X. Y. Han, G. S. May, and D. P. Kontoyiannis. 2003. Diagnosis of invasive septate mold infections. A correlation of microbiological culture and histologic or cytologic examination. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 119854-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Torres-Narbona, M., J. Guinea, J. Martínez-Alarcón, T. Peláez, and E. Bouza. 2007. In vitro activities of amphotericin B, caspofungin, itraconazole, posaconazole, and voriconazole against 45 clinical isolates of zygomycetes: comparison of CLSI M38-A, Sensititre YeastOne, and the Etest. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 511126-1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trifilio, S. M., C. L. Bennett, P. R. Yarnold, J. M. McKoy, J. Parada, J. Mehta. G. Chamilos, F. Palella, L. Kennedy, K. Mullane, M. S. Tallman, A. Evens, M. H. Scheetz, W. Blum, and D. P. Kontoyiannis. 2007. Breakthrough zygomycosis after voriconazole administration among patients with hematologic malignancies who receive hematopoietic stem-cell transplants or intensive chemotherapy. Bone Marrow Transplant. 39425-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Burik, J. A., R. S. Hare, H. F. Solomon, M. L. Corrado, and D. P. Kontoyiannis. 2006. Posaconazole is effective as salvage therapy in zygomycosis: a retrospective summary of 91 cases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42e61-e65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Voigt, K., E. Cigelnik, and K. O'Donnell. 1999. Phylogeny and PCR identification of clinically important zygomycetes based on nuclear ribosomal-DNA sequence data. J. Clin. Microbiol. 373957-3964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang, J. J., H. Satoh, H. Takahashi, and A. Hasegawa. 1990. A case of cutaneous mucormycosis in Shanghai, China. Mycoses 33311-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]