Abstract

IgaA is a membrane protein that prevents overactivation of the Rcs regulatory system in enteric bacteria. Here we provide evidence that igaA is the first gene in a σ70-dependent operon of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium that also includes yrfG, yrfH, and yrfI. We also show that the Lon protease and the MviA response regulator participate in regulation of the igaA operon. Our results indicate that MviA regulates igaA transcription in an RpoS-dependent manner, but the results also suggest that MviA may regulate RcsB activation in an RpoS- and IgaA-independent manner.

In Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, the igaA gene is located at centisome 75, between genes yrfE and yrfG (60). igaA encodes an inner membrane protein of 710 amino acids which is predicted to contain five transmembrane domains (28). igaA is homologous to yrfF in Escherichia coli and umoB in Proteus mirabilis (29) and was identified by analysis of a mutant with an increased growth rate in fibroblasts (16). This mutant harbored a substitution mutation, and the resulting allele was designated igaA1 (16). Mutants in the same gene (also named mucM) were independently isolated on the basis of their resistance to amdinocillin (23). igaA1 and other igaA point mutants are mucoid (due to upregulation of the wca genes), show a defect in motility (due to repression of the flhDC operon), and are attenuated for virulence (16). The attenuation is not explained by the motility defect but is partially explained by the overproduction of colanic acid capsule (28, 40). Different mucoid igaA point mutants display similar phenotypes but in different degrees that correlate with the degree of activation of the Rcs system (28). igaA is an essential gene (15). The phenotypes of viable (leaky) igaA point mutants and the lethality of null alleles are suppressed by mutations in rcsC, rcsD (previously named yojN), or rcsB (15, 23, 24, 28, 58), suggesting that loss of IgaA results in overactivation of the Rcs system.

Rcs is a phosphorelay initially characterized in E. coli as a regulator of colanic acid capsule synthesis (12, 43, 73). RcsC is a hybrid histidine kinase, RcsD is an intermediate phosphotransmitter (19, 78), and RcsB is the transcriptional regulator of the system. Other components of the system are RcsA, a second transcriptional activator (74), and RcsF (41), an outer membrane protein that lies upstream of RcsC in the signaling pathway RcsF → RcsC → RcsD → RcsB (54, 55). In addition, recent evidence suggests that RcsB can directly receive signals by accepting the phosphoryl group from acetyl phosphate (37).

The Rcs system participates in many processes in addition to the production of colanic acid capsule. The list includes synthesis of other exopolysaccharides (8, 66), synthesis of flagella (15, 36), swarming (4, 19, 44, 47), cell division (17), resistance to cell envelope stress (22, 50), and biofilm formation (35). Rcs also plays a role in the control of Salmonella virulence. rcsC mutants display modest attenuation in mice (27), and mutations in either igaA (28) or rcsC (40, 63) that hyperactivate the system show a much more pronounced effect, with extremely low competitive indices (CIs). This effect is partially suppressed by mutations that prevent colanic acid capsule synthesis (40, 63), suggesting that overproduction of capsule is one of the causes of attenuation in these mutants. However, additional loci involved in Salmonella virulence are also regulated by Rcs, including genes in Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1) (63, 84), SPI-2 (84), and SPI-4 (39). IgaA seems to prevent activation of the Rcs system during early stages of infection (28). However, this system also activates virulence genes required at later stages of infection (27, 31, 84).

The Rcs system can be transiently or moderately activated by certain environmental signals, including osmotic upshift (72) and a combination of low temperature and glucose or zinc (45). In addition, mutations in some genes or overexpression of others can lead to permanent activation of the Rcs signal transduction pathway. As mentioned above, this is the case for viable igaA alleles in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (28). Such mutants have been successfully exploited for the study of the Salmonella Rcs regulon (28, 39, 84). The igaA, rcsB, rcsD, and rcsC loci are present exclusively in enterobacteria and, interestingly, no bacterium whose genome has been sequenced has been found to contain only igaA or only the rcs genes. Such a coincidence is reminiscent of related functions (28) and suggests that the study of igaA is necessary for a full understanding of the Rcs system.

This work was undertaken to characterize the igaA transcriptional unit and to identify regulators of the expression of this gene. We show that igaA is the first gene in an operon driven by a σ70-dependent promoter. We also show that MviA, a response regulator that participates in the degradation of RpoS, modulates the expression of igaA and hence the activation of the Rcs system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, bacteriophage, and strain construction.

E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains used in this study are described in Table 1. Unless otherwise indicated, Salmonella strains are derived from the mouse-virulent strain ATCC 14028. Transductional crosses using phage P22 HT 105/1 int201 (71) were used for strain construction (56). To obtain phage-free isolates, transductants were purified by streaking on green plates (18). Phage sensitivity was tested by cross-streaking with the clear plaque mutant P22 H5.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strainsa

| Strain | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | supE44 ΔlacU169 (φ80 lacZΔM15) hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | 46 |

| UQ285 | lacZ4 rpoD285(ts) argG75 | 48 |

| S. enterica strains | ||

| 14028 | Wild type | ATCC |

| 55130 | pho-24 (PhoP constitutive) | E. A. Groisman |

| LT2 | Wild type | ATCC |

| SV4582 | φ(igaA-lacZY) Kmr ΔrcsC::MudQ | Laboratory stock |

| SV5590 | φ(igaA-lacZ)hyb Kmr ΔrcsB | This work |

| SV5663 | lon::Tn10dTc | This work |

| SV5664 | mviA::Tn10dTc | This work |

| SV4003 | rpoS::Apr | Laboratory stock |

| SV5614 | LT2 hns | Laboratory stock |

| SV4917 | flgK::MudJ | Laboratory stock |

| SV4610 | flhC5213::MudA | Laboratory stock |

| SV5737 | Φ(rcsB-lacZY) Kmr | This work |

| SV5738 | rcsB::3xFlag Kmr | 28 |

Derivatives of some of these strains were used as indicated in the text.

Media and chemicals.

The standard culture medium for S. enterica was Luria-Bertani (LB) broth. Solid LB contained agar at a 1.5% final concentration. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: kanamycin (Km), 50 μg ml−1; chloramphenicol (Cm), 20 μg ml−1; ampicillin (Ap), 100 μg ml−1. For some experiments 40 μg ml−1 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside and 0.2% glucose or arabinose were added to LB. Motility assays were carried out in LB prepared without yeast extract (42). Motility agar contained agar at a 0.25% final concentration.

DNA amplification by PCR.

Amplification reactions were carried out in a GeneAmp PCR System 2400 (Perkin-Elmer Cetus). The final volume of reaction mixtures was 50 to 100 μl, and the final concentration of MgCl2 was 1 mM. Reagents were used at the following concentrations: deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 200 μM; primers, 1 μM; Taq polymerase (Expand High Fidelity PCR system; Roche Diagnostics SL), 1 unit per reaction mixture. The thermal program included the following steps: (i) initial denaturation, 2 min at 94°C; (ii) 25 cycles of denaturation (94°C, 30 s), annealing (55°C, 30 s), and extension (72°C, 1 to 3 min); (iii) final incubation at 72°C for 7 min, to complete extension.

Construction of plasmid pIZ1586.

DNA from strain 14028 was used as a template for PCR amplification with primers igaApro5′ and igaApro3′ (Table 2). The amplified fragment was purified, digested with BamHI and BglII, and cloned on BglII-digested pIC552. The resulting plasmid (pIZ1586) carries a igaA::lac transcriptional fusion.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| A | GCGTGTATACCGATGCCAAC |

| A′ | CGCTGCTGGTGTTGTTTATG |

| F | CAGCTTTCATAGTATTCCTGG |

| G | GTTTCCGGTACCAGCTTTTG |

| H | GTAAGGGTTGCGTTCAGCTC |

| I | GAGCTGTACCGTAATGTCAC |

| igaApro5′ | GTCAGAATTCCAGCGTACCTGCGGCAATGG |

| igaApro3′ | CGTAGGATCCAGAGAGCAGGCCAGCAAAGC |

| Tn10d5′ | CTTTCTAAGGCAGACCAACC |

| Tn10d3′ | CACGCACAACAGATTTTACG |

| igaA-P1 | TCAGATGAGATTTTCCGGAGAGACGGTTAACCTGGGATGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| igaA-P4 | CGTTTTTGTACCGTGGATGATAGGCGGCGCGATCCTGCTGATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC |

| rcsB-P1 | ATTATTGCCGATGACCACCCGATTGTACTGTTCGGTATTCGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| rcsB-P2 | AGAGAGATAGTTGAGCAGCGCGATATCATTCTCTACGCCCCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG |

Construction of chromosomal lacZ fusions.

Disruption and replacement of igaA with a Cm resistance gene were performed as described previously (26). Briefly, the Cm resistance gene from plasmid pKD13 was PCR amplified with primers igaA-P1 and igaA-P4. The sequences of the primers used are shown in Table 2. The PCR product was used to transform the wild-type strain carrying the Red recombinase expression plasmid pKD46. The antibiotic resistance cassette introduced by the gene-targeting procedure was eliminated by recombination using the FLP helper plasmid pCP20 (26). The FRT site generated by excision of the antibiotic resistance cassette was used to integrate plasmid pCE40 to generate a translational lac fusion (30). The method for the construction of a transcriptional rcsB-lacZ fusion was similar except that the Km resistance gene from pKD4 was amplified with primers rcsB-P1 and rcsB-P4 and integration of pCE36 was used to generate the fusion (30).

RNA extraction.

Two protocols were used, one for primer extension and a different one for reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) experiments. In the first protocol, RNA preparations were obtained by guanidinium isothiocyanate lysis and phenol-chloroform extraction (20). Saturated cultures were immersed in liquid N2, and 1.4 ml of lysis solution (5 M guanidinium isothiocyanate, 50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 10 mM EDTA, 8% [vol/vol] β-mercaptoethanol) was added. Each mixture was incubated at 60°C for 10 min and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed and 0.28 ml of chloroform was added. After gentle shaking and incubation for 10 min at room temperature, the samples were centrifuged at 9,000 rpm for 10 min and 0.66 ml of isopropanol was added to the supernatant. The samples were incubated at −20°C for 15 min and centrifuged again at 9,000 rpm for 15 min. The pellets were then rinsed with 70% ethanol and dried. After resuspension in 75 μl of water (with 0.1% [vol/vol] diethyl pyrocarbonate), the samples were subjected to standard treatments with DNase and proteinase K, followed by extraction with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol and chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (70). The aqueous phase was precipitated with a 1/10 volume of 3 M sodium acetate, pH 4.8, and 2.5 volumes of absolute ethanol. The samples were then kept at −80°C for at least 30 min, centrifuged, and washed with 70% ethanol. Finally, the precipitates were dried and resuspended in 20 to 40 μl of diethyl pyrocarbonate-water. In the second protocol, to prepare cells for RNA extraction, 5 ml of fresh LB was inoculated 1:100 from an overnight culture and grown under antibiotic selection with shaking. Three biological replicates were performed for each strain, and RNA was extracted at an optical density at 600 nm of ∼3 (stationary phase). RNA extractions were performed as described by Mangan et al. (57). Briefly, 20% (vol/vol) ice-cold RNA stabilization solution (5% [vol/vol] phenol-95% ethanol) was added with mixing and the cultures were immediately incubated on ice for 30 min. The cultures were pelleted by centrifugation (3,100 × g for 30 min at 4°C) and pellets were stored at −80°C until required. RNA was extracted using a Promega SV total RNA purification kit. The RNA concentration was determined by the absorbance at 260 nm, and their quality was assessed on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer.

Primer extension.

The oligonucleotide igaApro3′ (Table 2), complementary to an internal region of the igaA gene, was end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and annealed to 25 μg of total RNA prepared from S. enterica strains. For annealing, 105 cpm of oligonucleotide was used. The end-labeled primer was extended with avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) under conditions described previously (59). The products of reverse transcription were analyzed in urea-polyacrylamide gels. For autoradiography, the gels were exposed to Kodak Biomax MR film.

RT-PCR.

Three micrograms of total RNA were treated with 1 U of Turbo DNA-free (Ambion, Inc., Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA by using MultiScribe reverse transcriptase with the random hexamers included in the kit. Then, 2 μl of each retrotranscription reaction mixture was subjected to PCR by using Taq DNA polymerase (Promega). Positive controls were performed with genomic DNA, and negative controls were performed with RNA that had been treated with TURBO DNA-free, and 5 U of RNase H from E. coli (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI) was reverse transcribed into cDNA and subjected to PCR.

Mutagenesis with Tn10dTc.

Strain ATCC 14028 was mutagenized with Tn10dTc (80). Pools of 4,500 colonies, each carrying an independent Tn10dTc insert, were then prepared and lysed with phage P22 HT. The lysates were used to transduce strains SV4582 and SV5590, selecting tetracycline (Tc)-resistant transductants on LB or minimal medium E plates supplemented with X-Gal, Tc, and Km.

Cloning and molecular characterization of Tn10dTc inserts.

Genomic DNA from each Tn10dTc-carrying isolate was digested with BamHI or XhoI and ligated with T4 DNA ligase to BamHI- or XhoI-digested pBlueScript II (SK). The ligations were transformed into E. coli DH5α cells, and Tn10dTc-containing transformants were selected on LB plates supplemented with Tc. The DNA sequences of the fusion junctions and the flanking DNA were obtained by sequencing with an automated DNA sequencer (Sistemas Genómicos SL, Valencia, Spain) using the primers Tn10d5′ and Tn10d3′.

DNA sequencing.

Sequencing reactions were carried out with the Sequenase 2.0 sequencing kit (U.S. Biochemical Corp., Cleveland, OH). The manufacturer's instructions were followed. Additionally, 1 μl of unlabeled dATP (10 μM) was added to the reaction mixtures. Sequencing gels were prepared in Tris-borate-EDTA and contained 6% acrylamide and 500 g/liter urea. The gels were run in a Poker Face SE1500 sequencer (Hoefer Scientific Instruments, San Francisco, CA), dried in a Slab gel dryer (model SE1160; Hoefer Scientific Instruments), and developed by exposure to X-ray film.

Sequence analysis.

Sequence analysis was performed with molecular biology algorithms from the National Center for Biotechnology Information at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov and the European Bioinformatics Institute at www.ebi.ac.uk.

β-Galactosidase assays.

Levels of β-galactosidase activity were assayed for exponential- and stationary-phase cultures in LB medium or in minimal medium as described previously (62), using the CHCl3-sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) permeabilization procedure.

Motility assays.

Liquid cultures were prepared in motility medium and incubated at 37°C with shaking. At the stage of mid-exponential growth, 5 μl of the culture was spotted in the center of a motility agar plate. The plate was incubated at 37°C. The diameter of the bacterial growth halo was measured every hour.

Mouse mixed infections and determination of CIs.

Eight-week-old female BALB/c mice (Charles River Laboratories, Santa Perpetua de Mogoda, Spain) were subjected to mixed infections. Groups of three to four animals were inoculated with a 1:1 ratio of two strains. Bacteria were grown overnight at 37°C in LB with shaking, diluted into fresh medium (1:100), and grown until an optical density at 600 nm of 0.3 to 0.6. Intraperitoneal inoculation was performed with 0.2 ml of saline containing 105 CFU. Bacteria were recovered from spleens 48 h after inoculation and CFU were enumerated on LB and on selective medium. A CI for each mutant was calculated as the ratio between the mutant and the wild-type strain in the output (bacteria recovered from the host after infection) divided by their ratio in the input (initial inoculum) (9, 38, 79).

Statistical analysis.

Each reported CI or β-galactosidase activity value is the mean of at least three independent experiments ± the standard error. Student's t test was used to analyze results. P values of 0.05 or less are considered significant.

Western blotting and antibodies.

Salmonella strains were grown overnight in LB. The bacteria were then pelleted by centrifugation, resuspended in NP-40 buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 10% glycerol) supplemented with protease inhibitors (1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1% aprotinin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin), and submitted to sonication and centrifugation. The soluble proteins contained in the supernatants were quantified and aliquots of each lysate were submitted to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on 10% acrylamide gels and electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose filters for immunoblot analysis using anti-Flag M2 monoclonal antibodies (1:5,000; Sigma). Goat anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies (Bio-Rad) were used as secondary antibodies. For stability tests, bacterial cultures were treated with chloramphenicol at 100 μg/ml and aliquots were removed at timed intervals for lysis and Western blotting.

RESULTS

Characterization of the igaA transcriptional unit.

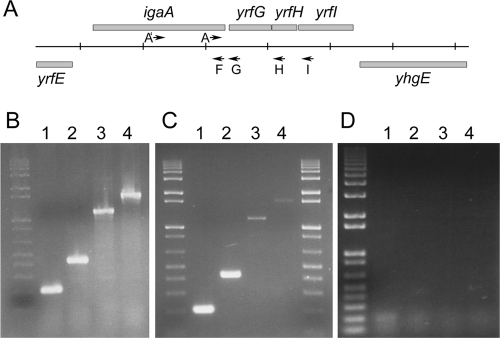

The igaA gene is annotated as yrfF in the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 complete sequence (60). This open reading frame (ORF) is located at centisome 75 flanked by yrfE, which is divergently transcribed, and yrfG (Fig. 1A). Analysis of this region with the OperonDB algorithm (http://www.cbcb.umd.edu/cgi-bin/operons/operons.cgi) (32) suggests that igaA could be the first gene in an operon that includes yrfG, yrfH, and yrfI. This prediction is based on codirectional transcription, distance between genes, and conservation of adjacency in other genomes. The analysis indicates that these four genes are consecutive on the same DNA strand in 15 other genomes, from bacterial species included in the genera Salmonella, Escherichia, Shigella, Yersinia, and Photorhabdus, and gives an 86% confidence to the conclusion that they belong to the same transcriptional unit. To get experimental support for this hypothesis, RT-PCR was performed by using oligonucleotide pairs designed to amplify regions that included a portion of igaA and downstream DNA sequences of various lengths. The efficacy of the primer pairs was first confirmed by carrying out PCR on genomic DNA (Fig. 1B). RT amplification products of the expected sizes (202 bp, 422 bp, 1,155 bp, and 1,621 bp) were observed with the four primer pairs used (Fig. 1C). A possible artifact due to DNA contamination was discarded by performing RT-PCR on an RNA sample previously treated with RNase H (Fig. 1D). In addition these results were confirmed by carrying out RT-PCRs using a different direct primer (A′) and the same reverse primers (G, H, and I). Amplification of products of the expected sizes (1,051 bp, 1,271 bp, 2,004 bp, and 2,470 bp) was obtained (not shown). In summary, these experiments provide evidence that igaA, yrfG, yrfH, and yrfI are transcriptionally linked.

FIG. 1.

Transcriptional organization of the igaA region. (A) Organization of the region containing the igaA gene in the Salmonella chromosome. Vertical lines are separated by 1 kb. The igaA (yrfF) ORF starts at position 3650187 and the yrfI ORF finishes at position 3654367 in the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 complete sequence. The arrows indicate the positions and orientations of the primers A′, A, F, G, H, and I that were used for RT-PCR. (B) Agarose gel of the products obtained when the PCR was performed with genomic DNA. Lanes: 1, primers A and F; 2, primers A and G; 3, primers A and H; 4, primers A and I. (C) Agarose gel of the RT-PCR products obtained with the same primers as for panel B. The molecular weight marker is the 1-kb ladder (Life Technologies). The expected sizes of the products are 202 bp, 422 bp, 1,155 bp, and 1,621 bp, respectively. (D) RT-PCR results for a sample of the RNA used for panel C, previously treated with RNase H; no products were observed.

σ70 dependence of the igaA operon transcription.

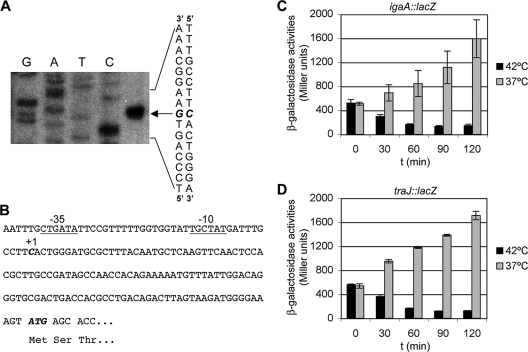

The next step in the characterization of the igaA transcriptional unit was the identification of the transcriptional start site. The intergenic region between yrfE and igaA, together with the first part of the coding region of igaA, was cloned in the plasmid pIC552 to generate a transcriptional fusion with the lacZ gene. This construct, pIZ1586, was introduced in strain 14028. Preliminary β-galactosidase activity measurements confirmed that the cloned region was enough to ensure expression. RNA isolated from the strain carrying the plasmid was used in primer extension experiments with the oligonucleotide igaApro3′. Primer extension results are shown in Fig. 2A. Transcription starts at a C located 125 bases upstream of the initiator AUG codon. Visual inspection reveals the presence of −10 and −35 regions related to the consensus sequences of σ70-dependent promoters (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

σ70-dependent transcription of igaA. (A) Primer extension was performed on strain 14028/pIZ1586. Lanes G, A, T, and C are the sequencing ladder. The base in italics is the transcriptional start site. (B) The sequence surrounding the transcriptional start site (in italics) and the translation initiator codon (in italics) are shown. Putative σ70 promoter consensus sequences are underlined. (C) Exponential-phase cultures of E. coli strain UQ285 (rpoD thermo-sensitive)/pIZ1586 (igaA::lac transcriptional fusion) were either maintained at 37°C (permissive temperature) or shifted to 42°C (restrictive temperature), and β-galactosidase activities were measured at the indicated times (in minutes). (D) Same experiment as in panel C but for a traJ::lac transcriptional fusion (plasmid pIZ898).

To test whether σ70 was necessary for igaA transcription, we studied the effect of a thermo-sensitive rpoD mutation on the expression of an igaA::lac fusion. For this purpose plasmid pIZ1586 was electroporated into the E. coli strain UQ285, which carries a thermo-sensitive rpoD allele. Exponential-phase cultures grown in LB with Ap at 37°C (permissive temperature) were split in two; one-half was maintained at the permissive temperature and the other was shifted to 42°C (restrictive temperature). At different time points aliquots were extracted and β-galactosidase activities were measured. A traJ::lac fusion in plasmid pIZ898 (14, 81) was also used as a control for a σ70-dependent gene. As shown in Fig. 2C and D, activities decreased over time at the restrictive temperature. Two hours after the shift, the activity of the igaA::lac fusion was 15-fold higher at 37°C than at 42°C. These results provide evidence that transcription of the igaAyrfGHI operon requires the rpoD-encoded σ70 factor.

Genetic screens for identification of genes regulating the igaA operon.

In order to identify genes that regulate igaA expression, we devised two genetic screens, one based on a chromosomal igaA::lac fusion and the other based on a translational fusion. Both fusions produce null alleles of the igaA gene, which are expected to be lethal. To avoid lethality, the fusions were obtained in an RcsB− background. Mutagenesis was carried out on the wild-type strain with the defective transposon Tn10dTc. Pools were prepared with resulting Tc-resistant colonies, each pool containing 4,500 independent insertions. These pools were used as donors in P22-mediated transduction experiments with the rcsB strains carrying the igaA::lac fusions as recipients. Transductants were selected in LB or minimal medium supplemented with Tc (the transposable element confers resistance to this antibiotic), Km (a resistance gene is associated with the lac fusions), and X-Gal (a chromogenic indicator for the activity of the fusions). With these screens we expected to detect insertions in genes for igaA activators (white colonies in indicator plates) and in genes for igaA repressors (darker colonies). Candidates were submitted to reconstruction crosses, in which the Tn10dTc element was transduced to the original strain, in order to ascertain that the observed phenotypes were associated with the insertions. β-Galactosidase activities of the igaA::lac fusions were measured from liquid cultures of every candidate. A total of 45,000 independent insertions were analyzed, both in LB and in minimal medium, and two of them significantly altered the expression of the fusions. To identify the loci where the Tn10dTc had inserted, chromosomal fragments containing the defective transposon were cloned in pBluescript SK (II). DNA sequencing was performed using primers Tn10d5′ and Tn10d3′ (Table 2). The genes identified in these screens were lon and mviA. Both genes appear to regulate the expression of the transcriptional (Table 3) and the translational (not shown) igaA::lac fusions. Lon protease could have an indirect effect on igaA expression, perhaps through the degradation of a transcriptional regulator. On the other hand, MviA was of interest as it is a response regulator from a two-component system involved in the control of virulence in Salmonella (5, 7, 76). For this reason, we decided to further characterize the effect of MviA on igaA expression.

TABLE 3.

igaA regulators found in screens with lac fusions

| Screen | Gene interrupted | Activity of transcriptional igaA::lacZ fusion (Miller units)

|

References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMa

|

LBb

|

|||||

| WT | Mutant | WT | Mutant | |||

| Transcriptional fusion in minimal medium | lon | 157.5 ± 8.3 | 82.0 ± 5.9 | 65.1 ± 1.7 | 50.5 ± 0.2 | 13, 21, 87 |

| Translational fusion in LB | mviA | 71.3 ± 12.8 | 37.4 ± 3.9 | 51.3 ± 2.7 | 26.7 ± 1.4 | 6, 75 |

Activities were measured from cultures in minimal medium (MM).

Activities were measured from cultures in LB medium. Data are the means ± standard deviations from three measures. WT, wild type.

Regulation of igaA by MviA is mediated by RpoS.

A null mutation in mviA (for mouse virulence gene A [7]) leads to avirulence in mice in almost all the S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains examined (77). The exception is LT2, a strain that was originally described as virulent for mice in 1948 (53). Avirulent LT2 derivatives become virulent by inactivating mviA (7). In all strains except LT2, avirulence caused by mviA mutations is correlated with a growth defect reflected in the small size (Scm+ phenotype) of the colonies formed on agar plates. The E. coli mviA homolog is known as rssB (64) or sprE (69). The N-terminal region of MviA/RssB is very similar to CheY and other response regulators, including an aspartate at position 58 that is predicted to be phosphorylated, causing MviA activation. The way this phosphorylation is controlled is not clear, but involvement of acetyl phosphate (10, 25) and the histidine kinase ArcB (61) have been suggested. The C-terminal region of MviA has no similarity with other known proteins and apparently does not contain a DNA binding domain. In contrast, MviA is involved in posttranslational regulation of the σ factor RpoS. mviA mutants show increased levels of RpoS that are at least partially responsible for their phenotypes (3, 64, 69). In this context, the function of MviA is in binding RpoS and acting as an adaptor for recognition and degradation by the ClpXP protease (49, 89).

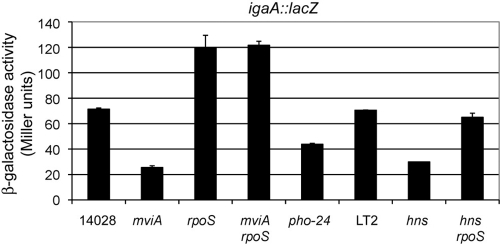

To test if the increased levels of RpoS were responsible for the repression of igaA transcription in the mviA mutant, we measured expression of the igaA::lacZ transcriptional fusion in different genetic backgrounds combining mviA and rpoS null mutations. As shown in Fig. 3, a mutation in rpoS led to a small but significant increase in the activity of the fusion and suppressed the effect of the mviA mutation. These results are consistent with the idea that igaA regulation by MviA is mediated by RpoS.

FIG. 3.

igaA transcription is regulated by MviA, RpoS, PhoP, and H-NS. Expression levels of igaA were monitored with a lacZ transcriptional fusion in the indicated genetic backgrounds. hns and hns rpoS strains should be compared to LT2, and the rest should be compared to 14028. The data represent the means and standard deviations from at least two experiments. According to the Student t test differences between the single mutant backgrounds and the corresponding wild-type backgrounds were statistically significant.

Other genes involved in posttranslational control of RpoS also regulate igaA.

In E. coli, the nucleoid-associated protein H-NS affects both RpoS mRNA translation and RpoS turnover in logarithmic growth: a 10-fold increase in the RpoS synthesis rate, as well as a 10-fold increase in RpoS stability, is observed in hns mutants (2, 86). An hns mutant of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium is also defective in RpoS turnover (25). In E. coli the effect on stability is mediated by RssB (MviA). An unidentified antiadaptor, negatively regulated by H-NS, may prevent the action of RssB on RpoS (11, 88). According to our hypothesis, a similar relationship between MviA and H-NS in Salmonella would lead to a decrease in the expression of igaA in an hns mutant.

In Salmonella, but not in E. coli, the response regulator PhoP controls RpoS stability through the transcriptional activation of iraP, whose product is an antiadaptor that prevents degradation of RpoS through a direct interaction with MviA (11, 83). Thus, one would predict a negative effect of PhoP on the expression of igaA.

Bearing these precedents in mind we tested the effect of hns and phoP/phoQ mutations on igaA::lacZ. Mutations in Salmonella hns are lethal unless accompanied by compensatory mutations in other regulatory loci, like rpoS (67). For this reason, experiments involving hns mutations were carried out in an LT2 background, in which lethality is prevented due to a leaky, rpoS mutation (52). For the PhoPQ two-component system, a mutation that confers constitutive activation of the system (pho-24) was used. Both an hns null mutation and the pho-24 mutation caused decreases in igaA expression that were statistically significant (P < 0.001) and that agreed with our predictions (Fig. 3).

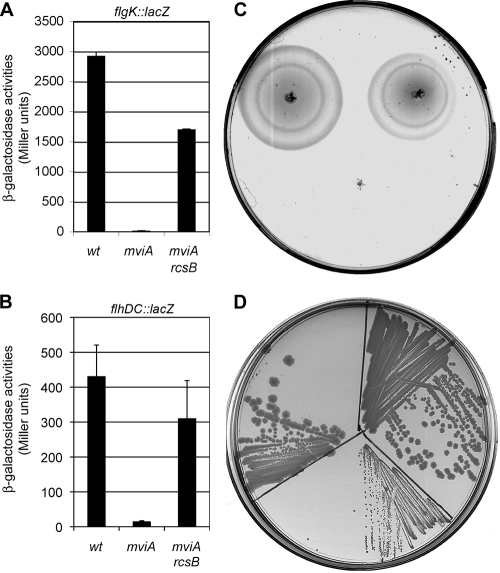

Some of the phenotypes of the mviA mutant are mediated by RcsB.

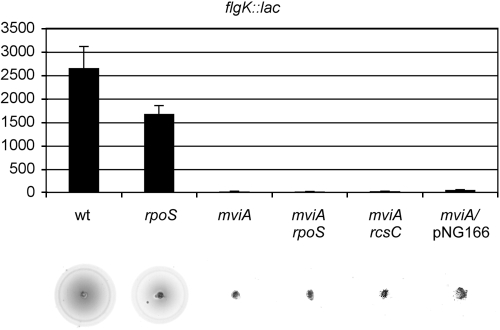

The fact that igaA is regulated by MviA, together with the role of igaA as an inhibitor of the activity of the Rcs system, suggests that some of the effects of the mviA mutation could be due to activation of the Rcs system. This system regulates flagellum synthesis through repression of the flhDC operon (16). To test the effect of an mviA mutation on flagellar genes we used a flgK::lacZ transcriptional fusion. This gene was completely repressed in an mviA background (Fig. 4A), a result that was in agreement with the idea that this mutation activates the Rcs system. Partial suppression of this effect by an rcsB mutation gave support to this view (Fig. 4A). To establish the generality of these findings we studied the effects of the mviA mutation on the master flagellar operon flhDC and we got similar results: a flhDC::lacZ transcriptional fusion was repressed in the mviA mutant and this repression was suppressed by an rcsB mutation (Fig. 4B). These results were confirmed by comparing the wild-type and the mutant strains on motility agar plates. Figure 4C shows that the mviA mutant is nonmotile and that a mutation in rcsB partially suppresses this phenotype. The fact that this new phenotype (lack of motility) of the mviA mutant is mediated by RcsB suggests that other phenotypes of this mutant could also be mediated by this regulatory system. The most conspicuous phenotype of the mviA mutant is the small colony morphology (Scm+). Comparison of the growth on LB agar of the wild type and the mviA and mviA rcsB mutants suggests that, in fact, the activity of the Rcs system is involved in this phenotype (Fig. 4D).

FIG. 4.

MviA regulates the Rcs system. (A) Expression of an flgK::lacZ transcriptional fusion in wild-type, mviA, or mviA rcsB backgrounds. The data shown are means and standard deviations from three experiments. (B) Expression of an flhDC::lacZ transcriptional fusion in wild-type, mviA, or mviA rcsB strains. The data shown are means and standard deviations from three experiments. (C) Motility of the wild-type strain (upper left), the mviA mutant (center), and the mviA rcsB double mutant (upper right). Bacteria were spotted onto motility agar and incubated for 6 h at 37°C. (D) Colony morphology of the wild-type strain (upper left), the mviA mutant (center), and the mviA rcsB double mutant (upper right). The Scm+ phenotype of the mviA mutant is suppressed by an rcsB mutation.

One of the most interesting phenotypes of Salmonella mviA mutants is avirulence in mice (77). The prevalent view is that this virulence defect is caused by increased levels of RpoS (77, 85). However, this hypothesis has not been directly tested because Salmonella rpoS null mutants are also avirulent (33). Since decreased levels of IgaA lead to activation of RcsB (28) and overactivation of Rcs causes attenuation (28, 40), a possibility is that avirulence of the mviA mutant is, at least partially, mediated by the Rcs system. A prediction of this hypothesis is that a null mutation in rcsB would suppress avirulence of the mviA mutant. To test this possibility, competitive indexes in mice were calculated both for the mviA single mutant and the mviA rcsB double mutant after mixed infections with the wild type by the intraperitoneal route. The results (means of three experiments ± standard deviations) were as follows: whereas the single mutant had a CI of 0.0006 ± 0.0002, the CI for the double mutant was 0.12 ± 0.06. This indicates that the double mutant is much more virulent than the single mutant but less virulent than the wild type and suggests partial suppression of the avirulence of the mviA mutant by the rcsB null mutation, which is in agreement with our hypothesis.

MviA also regulates RcsB in an RpoS- and IgaA-independent fashion.

The simplest interpretation of the data presented here is that the mviA mutation activates RcsB through a decrease in the levels of IgaA, which is in turn due to an increased RpoS level. In this context we would expect that the phenotypes of the mviA mutant that are suppressed by null rcsB mutations were also suppressed by null rpoS mutations. In support of this idea, the Scm+ phenotype, which is suppressed by the rcsB mutation, is also suppressed by an rpoS mutation (76) (data not shown). On the other hand this mutation is not able to suppress attenuation of the mviA mutant, since the rpoS mutant is itself avirulent, as mentioned above. We decided to examine the effects on flagellum synthesis and, surprisingly, we found that the rpoS mutation does not suppress the effect of the mviA mutation on the expression of flgK (Fig. 5). In addition, the mviA rpoS double mutant was nonmotile (Fig. 5). These results suggest that MviA may control the activity of RcsB through an RpoS- and IgaA-independent pathway. To further explore this possibility, we took advantage of a mutation in rcsC, the gene that mediates the effects of IgaA on the Rcs system. This mutation was unable to suppress the effects of the mviA mutation on flgK expression, motility (Fig. 5), or small colony morphology (not shown). In addition, the introduction of plasmid pNG1166, a pBAD18 derivative that carries the igaA gene under the control of the PBAD promoter, does not alter the phenotypes of the mviA mutant (Fig. 5 and data not shown).

FIG. 5.

MviA regulation of flgK transcription is RcsB dependent but RpoS, RcsC, and IgaA independent. β-Galactosidase activities (in Miller units) of the flgK::lac fusion were measured in the indicated backgrounds using stationary-phase cultures in LB medium. The data are the means ± standard deviations of two independent experiments. The results of a motility assay for each strain are also shown.

MviA controls levels of RcsB.

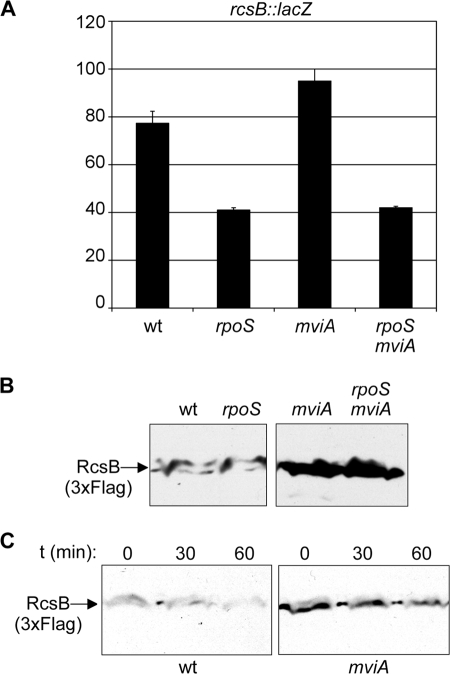

A tentative explanation for the results in the preceding section is that MviA, in addition to controlling the IgaA-RcsC-RcsD-RcsB pathway through RpoS, might regulate RcsB expression at the transcriptional or posttranscriptional level. To test the effect of mviA on rcsB transcription, we used an rcsB::lacZ transcriptional fusion. Expression of this fusion was only slightly altered in the mviA background (Fig. 6A). To test whether posttranscriptional regulation might occur, we used a strain carrying a 3xFlag tag at the 3′ end of the rcsB gene. Immunoblot analysis revealed an increased level of RcsB in an mviA background (Fig. 6B). Although an rpoS mutation had a slight effect on rcsB transcription (Fig. 6A) it did not suppress the effect of mviA on the RcsB level (Fig. 6B). These results suggest that defects in MviA could alter either the translational efficiency or rcsB mRNA or proteolytic turnover of the RcsB protein. To ascertain between these alternatives, we tested the effect of an mviA mutation on RcsB turnover. Cultures of mviA+ and mviA strains were treated with chloramphenicol to prevent further synthesis of RcsB, and samples for Western blot analysis were collected at defined time intervals. As seen in Fig. 6C, although the levels of RcsB were increased in the mviA strain, the stability of the protein did not appear to be altered. These results suggest that, aside from influencing activation of the Rcs system through RpoS and IgaA, MviA may also control the level of RcsB protein in an RpoS-independent manner.

FIG. 6.

MviA regulation of RcsB. (A) β-Galactosidase activities (in Miller units) of an rcsB::lac fusion in wild-type (wt), rpoS, mviA, and mviA rpoS backgrounds. The data are the means ± standard deviations of two independent experiments. (B) Immunoblot analysis of the levels of RcsB-3xFlag in the wild-type, rpoS, mviA, and mviA rpoS backgrounds. Strains were cultured in LB medium. Protein extracts were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE. The same amount of protein was loaded in each lane. Immunoblotting was performed with a monoclonal anti-Flag antibody. (C) Stability of RcsB-3xFlag in wild-type and mviA strains. The level of RcsB-3xFlag was analyzed by immunoblotting 0, 30, and 60 min after the addition of chloramphenicol to cultures in LB.

DISCUSSION

As an essential gene involved in the control of virulence in Salmonella, igaA is an attractive subject of research. However, most of the interest of the study of igaA has resulted from its use as a tool for the study of the Rcs system. In fact, the use of different igaA mutant alleles has uncovered new aspects of the Rcs system in Salmonella, including its role in the regulation of virulence (28). In this work, we decided to focus on igaA itself, and we have been able to show that (i) igaA is the first gene in an operon that includes four genes, (ii) its promoter is σ70 dependent, and (iii) its transcription is regulated by Lon and MviA. In addition we have unveiled relationships between the Rcs system, RpoS, and MviA.

None of the phenotypes of igaA mutants seems to be due to polar effects on downstream genes: first, most of the mutants used are nonpolar, point mutants (15, 16, 28, 84); second, a polar insertion in the second gene of the operon, yrfG, is not lethal and does not produce any of the phenotypes associated with igaA mutations (15); third, a plasmid-borne igaA+ allele is able to complement an igaA null mutation (15). There are no experimental data about the function of yrfG, yrfH, or yrfI, although sequence similarities suggest that they may encode a hydrolase and two heat shock proteins (Hsp15 and Hsp30), respectively.

Analysis of six viable (leaky) igaA mutants revealed that none of the corresponding mutations compromised the level of the protein in exponential growth phase. However, three mutations mapping in the putative cytoplasmic domains caused a significant IgaA decrease in stationary phase, and this loss of protein correlated with activation of the Rcs phosphorelay (28). These previous results support the idea that the control of igaA expression could be a way to regulate the activation of the Rcs system. The results presented here show that, in fact, Lon and MviA regulate igaA at the transcriptional level.

Although early studies in E. coli identified Lon as a DNA binding protein, its ability for sequence-specific binding remains unclear. In contrast it has been clearly established that Lon is an ATP-dependent protease highly conserved in archaea, eubacteria, and eukaryotic mitochondria and peroxisomes (reviewed in reference 51). Therefore, our results are more likely explained by an indirect effect of Lon. As a heat shock protein, one of the main functions of Lon is to act as a quality control protease. However it is also important for the degradation of short-lived regulatory proteins. A possibility is that Lon may degrade an unidentified repressor of igaA. Interestingly, Lon is known to degrade RcsA (82), a coactivator necessary for the transcription of a subset of the Rcs-regulated genes. igaA is not itself regulated by the Rcs system, since an rcsB mutation does not modify the expression of the igaA::lacZ transcriptional fusion (data not shown). Our results suggest that Lon could be negatively controlling the Rcs system in two ways: directly lowering the levels of RcsA and indirectly increasing the levels of IgaA.

Although MviA is a response regulator for a two-component regulatory system, it does not appear to contain a DNA binding domain. This suggests that its effect on the igaA transcription may be indirect. Our results show that this effect is mediated by RpoS. This is in agreement with the known role of MviA in the control of RpoS stability. In addition, we have shown that a mutation in RpoS is able not only to suppress the effect of an mviA mutation but also to increase the levels of igaA transcription. At least two hypotheses can explain the negative action of RpoS on a σ70-dependent operon: (i) RpoS might control transcription of an igaA repressor; (ii) RpoS might compete with σ70 for core RNA polymerase. Sigma factor competition is not a new idea (90), and it has been proposed as a general mechanism to explain RpoS-dependent repression of σ70-dependent genes (34, 68).

MviA acts as an adaptor for the protease ClpXP. The action of MviA is controlled by other proteins, called antiadaptors (11). One such antiadaptors is negatively regulated by H-NS (88) and another is positively regulated by the PhoPQ two-component system (83). Our results showing that both a null mutation in hns and a “constitutive” mutation in phoP result in a decrease in igaA transcription are consistent with the previously described relationships between these regulatory proteins and give additional support to the finding that igaA is regulated by MviA and RpoS.

The only known function of IgaA is repression of the Rcs system. Conditions like the mviA mutation that decrease the levels of IgaA are expected to result in activation of the Rcs system. Several results in this paper are consistent with this prediction: the phenotypes of avirulence, lack of motility, lack of expression of flagellar genes, and small colony type are suppressed, at least partially, by an rcsB null mutation. Based on the results presented above, we propose a model in which RpoS has a negative effect on igaA transcription by competing with σ70. Through degradation of RpoS, MviA positively controls the expression of igaA. H-NS and PhoP would fit in this model because they control the expression of antiadaptors that antagonize the action of MviA. Recent microarray data show that the Rcs system normally functions as a positive regulator of SPI-2 and other genes important for the growth of Salmonella in macrophages, although when highly activated the system completely represses the SPI-1/SPI-2 virulence, flagellar, and fimbrial biogenesis pathways (84). It is tempting to speculate that activation of phoP in the intracellular environment would modulate degradation of RpoS, leading to repression of igaA and activation of the Rcs system, giving physiological significance to our results.

Although most of our data are consistent with the model proposed above, some results are puzzling: the repression of flagellum genes in the mviA mutant is suppressed by an rcsB mutation but not by an rpoS mutation, by an rcsC mutation, or by overexpression of igaA. These results do not fit the model but can be explained if we assume that MviA can also repress RcsB activity in an RpoS-, IgaA-, and RcsC-independent way. The idea that MviA does not act exclusively through RpoS is consistent with previous data from Erwinia carotovora. The ortholog of mviA in this plant pathogen is expM. An expM mutant exhibits reduced virulence in tobacco and is affected in production and secretion of extracellular enzymes. Suppression of both phenotypes by an rpoS mutation can be tested in this pathogen, since rpoS mutants of Erwinia carotovora are not avirulent (65). The conclusion is that overproduction of RpoS is an important factor to explain the phenotypes of the expM mutant. However an expM rpoS double mutant exhibits decreased virulence and secretion of extracellular enzymes in comparison with an rpoS single mutant, suggesting that ExpM in addition to RpoS acts on other targets (1). According to the results presented here, RcsB could be one such target in Salmonella. It is interesting that some of the phenotypes of the mviA mutant could be the result of the simultaneous effect on different targets. For instance, the Scm+ phenotype is suppressed by both an rpoS mutation and an rcsB mutation (but not an rcsC mutation), indicating that an increase in RpoS level and RcsB overactivation are simultaneously necessary to produce this phenotype.

There are at least three hypotheses to explain this effect of MviA on RcsB: (i) the mviA mutation alters RcsB activation through cross-phosphorylation, perhaps using another histidine kinase or acetyl phosphate; (ii) MviA represses rcsB transcription; (iii) MviA alters the levels of the RcsB protein influencing mRNA translation efficiency or protein stability. Hypotheses ii and iii are based on the fact that overexpression of rcsB mimics overactivation of the Rcs system (39).

The differences detected in the immunoblot analysis shown in Fig. 6B cannot be explained by the slight differences observed in rcsB transcription (Fig. 6A) and support RpoS-independent, posttranscriptional control of rcsB by MviA. Data presented in Fig. 6C are more consistent with an effect in translation efficiency, since the stability of the RcsB protein does not appear to be altered in an mviA background.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants BIO2007-67457-C02-02 (to J.C.) and SAF2007-60738 (to F.R.-M.) from the Ministry of Education and Science of Spain and the European Regional Development Fund. C.G.-C. is a Ph.D. student supported by a predoctoral grant from the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science.

We are grateful to Francisco García-del Portillo and Gustavo Domínguez-Bernal for discussions and for the generous gift of some strains and to Modesto Carballo and Alberto García-Quintanilla (Servicio de Biología, CITIUS, Universidad de Sevilla) for help in certain experiments.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 February 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersson, R. A., E. T. Palva, and M. Pirhonen. 1999. The response regulator expM is essential for the virulence of Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora and acts negatively on the sigma factor RpoS (sigma s). Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 12575-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barth, M., C. Marschall, A. Muffler, D. Fischer, and R. Hengge-Aronis. 1995. Role for the histone-like protein H-NS in growth phase-dependent and osmotic regulation of sigma S and many sigma S-dependent genes in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1773455-3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bearson, S. M., W. H. Benjamin, Jr., W. E. Swords, and J. W. Foster. 1996. Acid shock induction of RpoS is mediated by the mouse virulence gene mviA of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 1782572-2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belas, R., R. Schneider, and M. Melch. 1998. Characterization of Proteus mirabilis precocious swarming mutants: identification of rsbA, encoding a regulator of swarming behavior. J. Bacteriol. 1806126-6139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benjamin, W. H., Jr., C. L. Turnbough, Jr., J. D. Goguen, B. S. Posey, and D. E. Briles. 1986. Genetic mapping of novel virulence determinants of Salmonella typhimurium to the region between trpD and supD. Microb. Pathog. 1115-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benjamin, W. H., Jr., X. Wu, and W. E. Swords. 1996. The predicted amino acid sequence of the Salmonella typhimurium virulence gene mviA+ strongly indicates that MviA is a regulator protein of a previously unknown S. typhimurium response regulator family. Infect. Immun. 642365-2367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benjamin, W. H., Jr., J. Yother, P. Hall, and D. E. Briles. 1991. The Salmonella typhimurium locus mviA regulates virulence in Itys but not Ityr mice: functional mviA results in avirulence; mutant (nonfunctional) mviA results in virulence. J. Exp. Med. 1741073-1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bereswill, S., and K. Geider. 1997. Characterization of the rcsB gene from Erwinia amylovora and its influence on exopolysaccharide synthesis and virulence of the fire blight pathogen. J. Bacteriol. 1791354-1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beuzón, C. R., and D. W. Holden. 2001. Use of mixed infections with Salmonella strains to study virulence genes and their interactions in vivo. Microbes Infect. 31345-1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bouche, S., E. Klauck, D. Fischer, M. Lucassen, K. Jung, and R. Hengge-Aronis. 1998. Regulation of RssB-dependent proteolysis in Escherichia coli: a role for acetyl phosphate in a response regulator-controlled process. Mol. Microbiol. 27787-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bougdour, A., C. Cunning, P. J. Baptiste, T. Elliott, and S. Gottesman. 2008. Multiple pathways for regulation of σS (RpoS) stability in Escherichia coli via the action of multiple anti-adaptors. Mol. Microbiol. 68298-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brill, J. A., C. Quinlan-Walshe, and S. Gottesman. 1988. Fine-structure mapping and identification of two regulators of capsule synthesis in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 1702599-2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bukhari, A. I., and D. Zipser. 1973. Mutants of Escherichia coli with a defect in the degradation of nonsense fragments. Nat. New Biol. 243238-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Camacho, E. M., and J. Casadesús. 2002. Conjugal transfer of the virulence plasmid of Salmonella enterica is regulated by the leucine-responsive regulatory protein and DNA adenine methylation. Mol. Microbiol. 441589-1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cano, D. A., G. Domínguez-Bernal, A. Tierrez, F. García-del Portillo, and J. Casadesús. 2002. Regulation of capsule synthesis and cell motility in Salmonella enterica by the essential gene igaA. Genetics 162:1513-1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cano, D. A., M. Martinez-Moya, M. G. Pucciarelli, E. A. Groisman, J. Casadesus, and F. Garcia-Del Portillo. 2001. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium response involved in attenuation of pathogen intracellular proliferation. Infect. Immun. 696463-6474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carballès, F., C. Bertrand, J. P. Bouché, and K. Cam. 1999. Regulation of Escherichia coli cell division genes ftsA and ftsZ by the two-component system rcsC-rcsB. Mol. Microbiol. 34442-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan, R. K., D. Botstein, T. Watanabe, and Y. Ogata. 1972. Specialized transduction of tetracycline resistance by phage P22 in Salmonella typhimurium. II. Properties of a high-frequency-transducing lysate. Virology 50883-898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen, M. H., S. Takeda, H. Yamada, Y. Ishii, T. Yamashino, and T. Mizuno. 2001. Characterization of the RcsC→YojN→RcsB phosphorelay signaling pathway involved in capsular synthesis in Escherichia coli. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 652364-2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chomczynski, P., and N. Sacchi. 1987. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal. Biochem. 162156-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chung, C. H., and A. L. Goldberg. 1981. The product of the lon (capR) gene in Escherichia coli is the ATP-dependent protease, protease La. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 784931-4935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conter, A., R. Sturny, C. Gutierrez, and K. Cam. 2002. The RcsCB His-Asp phosphorelay system is essential to overcome chlorpromazine-induced stress in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1842850-2853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Costa, C. S., and D. N. Antón. 2001. Role of the ftsA1p promoter in the resistance of mucoid mutants of Salmonella enterica to mecillinam: characterization of a new type of mucoid mutant. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 200201-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Costa, C. S., M. J. Pettinari, B. S. Mendez, and D. N. Anton. 2003. Null mutations in the essential gene yrfF (mucM) are not lethal in rcsB, yojN or rcsC strains of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 22225-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cunning, C., and T. Elliott. 1999. RpoS synthesis is growth rate regulated in Salmonella typhimurium, but its turnover is not dependent on acetyl phosphate synthesis or PTS function. J. Bacteriol. 1814853-4862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 976640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Detweiler, C. S., D. M. Monack, I. E. Brodsky, H. Mathew, and S. Falkow. 2003. virK, somA and rcsC are important for systemic Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection and cationic peptide resistance. Mol. Microbiol. 48385-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Domínguez-Bernal, G., M. G. Pucciarelli, F. Ramos-Morales, M. García-Quintanilla, D. A. Cano, J. Casadesús, and F. García-del Portillo. 2004. Repression of the RcsC-YojN-RcsB phosphorelay by the IgaA protein is a requisite for Salmonella virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 531437-1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dufour, A., R. B. Furness, and C. Hughes. 1998. Novel genes that upregulate the Proteus mirabilis flhDC master operon controlling flagellar biogenesis and swarming. Mol. Microbiol. 29741-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ellermeier, C. D., A. Janakiraman, and J. M. Slauch. 2002. Construction of targeted single copy lac fusions using lambda Red and FLP-mediated site-specific recombination in bacteria. Gene 290153-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Erickson, K. D., and C. S. Detweiler. 2006. The Rcs phosphorelay system is specific to enteric pathogens/commensals and activates ydeI, a gene important for persistent Salmonella infection of mice. Mol. Microbiol. 62883-894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ermolaeva, M. D., O. White, and S. L. Salzberg. 2001. Prediction of operons in microbial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 291216-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fang, F. C., S. J. Libby, N. A. Buchmeier, P. C. Loewen, J. Switala, J. Harwood, and D. G. Guiney. 1992. The alternative sigma factor katF (rpoS) regulates Salmonella virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 8911978-11982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farewell, A., K. Kvint, and T. Nystrom. 1998. Negative regulation by RpoS: a case of sigma factor competition. Mol. Microbiol. 291039-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferrières, L., and D. J. Clarke. 2003. The RcsC sensor kinase is required for normal biofilm formation in Escherichia coli K-12 and controls the expression of a regulon in response to growth on a solid surface. Mol. Microbiol. 501665-1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Francez-Charlot, A., B. Laugel, A. Van Gemert, N. Dubarry, F. Wiorowski, M. P. Castanie-Cornet, C. Gutierrez, and K. Cam. 2003. RcsCDB His-Asp phosphorelay system negatively regulates the flhDC operon in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 49823-832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fredericks, C. E., S. Shibata, S. Aizawa, S. A. Reimann, and A. J. Wolfe. 2006. Acetyl phosphate-sensitive regulation of flagellar biogenesis and capsular biosynthesis depends on the Rcs phosphorelay. Mol. Microbiol. 61734-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Freter, R., P. C. O'Brien, and M. S. Macsai. 1981. Role of chemotaxis in the association of motile bacteria with intestinal mucosa: in vivo studies. Infect. Immun. 34234-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.García-Calderón, C. B., J. Casadesús, and F. Ramos-Morales. 2007. Rcs and PhoPQ regulatory overlap in the control of Salmonella enterica virulence. J. Bacteriol. 1896635-6644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.García-Calderón, C. B., M. García-Quintanilla, J. Casadesús, and F. Ramos-Morales. 2005. Virulence attenuation in Salmonella enterica rcsC mutants with constitutive activation of the Rcs system. Microbiology 151579-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gervais, F. G., and G. R. Drapeau. 1992. Identification, cloning, and characterization of rcsF, a new regulator gene for exopolysaccharide synthesis that suppresses the division mutation ftsZ84 in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 1748016-8022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gillen, K. L., and K. T. Hughes. 1991. Negative regulatory loci coupling flagellin synthesis to flagellar assembly in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 1732301-2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gottesman, S., P. Trisler, and A. Torres-Cabassa. 1985. Regulation of capsular polysaccharide synthesis in Escherichia coli K-12: characterization of three regulatory genes. J. Bacteriol. 1621111-1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gygi, D., M. M. Rahman, H. C. Lai, R. Carlson, J. Guard-Petter, and C. Hughes. 1995. A cell-surface polysaccharide that facilitates rapid population migration by differentiated swarm cells of Proteus mirabilis. Mol. Microbiol. 171167-1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hagiwara, D., M. Sugiura, T. Oshima, H. Mori, H. Aiba, T. Yamashino, and T. Mizuno. 2003. Genome-wide analyses revealing a signaling network of the RcsC-YojN-RcsB phosphorelay system in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1855735-5746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hanahan, D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166557-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harshey, R. M., and T. Matsuyama. 1994. Dimorphic transition in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: surface-induced differentiation into hyperflagellate swarmer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 918631-8635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Isaksson, L. A., S. E. Skold, J. Skjoldebrand, and R. Takata. 1977. A procedure for isolation of spontaneous mutants with temperature sensitive of RNA and/or protein. Mol. Gen. Genet. 156233-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klauck, E., M. Lingnau, and R. Hengge-Aronis. 2001. Role of the response regulator RssB in sigma recognition and initiation of sigma proteolysis in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 401381-1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laubacher, M. E., and S. E. Ades. 2008. The Rcs phosphorelay is a cell envelope stress response activated by peptidoglycan stress and contributes to intrinsic antibiotic resistance. J. Bacteriol. 1902065-2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee, I., and C. K. Suzuki. 2008. Functional mechanics of the ATP-dependent Lon protease: lessons from endogenous protein and synthetic peptide substrates. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1784727-735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee, I. S., J. Lin, H. K. Hall, B. Bearson, and J. W. Foster. 1995. The stationary-phase sigma factor sigma S (RpoS) is required for a sustained acid tolerance response in virulent Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 17155-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lillengen, K. 1948. Typing Salmonella typhimurium by means of bacteriophage. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. Suppl. 7711-125. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Majdalani, N., and S. Gottesman. 2005. The Rcs phosphorelay: a complex signal transduction system. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 59379-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Majdalani, N., M. Heck, V. Stout, and S. Gottesman. 2005. Role of RcsF in signaling to the Rcs phosphorelay pathway in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1876770-6778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maloy, S. R. 1990. Experimental techniques in bacterial genetics. Jones & Barlett, Boston, MA.

- 57.Mangan, M. W., S. Lucchini, V. Danino, T. O. Croinin, J. C. Hinton, and C. J. Dorman. 2006. The integration host factor (IHF) integrates stationary-phase and virulence gene expression in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 591831-1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mariscotti, J. F., and F. Garcia-Del Portillo. 2008. Instability of the Salmonella RcsCDB signalling system in the absence of the attenuator IgaA. Microbiology 1541372-1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marques, S., J. L. Ramos, and K. N. Timmis. 1993. Analysis of the mRNA structure of the Pseudomonas putida TOL meta fission pathway operon around the transcription initiation point, the xylTE and the xylFJ regions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1216227-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McClelland, M., K. E. Sanderson, J. Spieth, S. W. Clifton, P. Latreille, L. Courtney, S. Porwollik, J. Ali, M. Dante, F. Du, S. Hou, D. Layman, S. Leonard, C. Nguyen, K. Scott, A. Holmes, N. Grewal, E. Mulvaney, E. Ryan, H. Sun, L. Florea, W. Miller, T. Stoneking, M. Nhan, R. Waterston, and R. K. Wilson. 2001. Complete genome sequence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2. Nature 413852-856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mika, F., and R. Hengge. 2005. A two-component phosphotransfer network involving ArcB, ArcA, and RssB coordinates synthesis and proteolysis of sigmaS (RpoS) in E. coli. Genes Dev. 192770-2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 63.Mouslim, C., M. Delgado, and E. A. Groisman. 2004. Activation of the RcsC/YojN/RcsB phosphorelay system attenuates Salmonella virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 54386-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Muffler, A., D. Fischer, S. Altuvia, G. Storz, and R. Hengge-Aronis. 1996. The response regulator RssB controls stability of the σS subunit of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 151333-1339. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mukherjee, A., Y. Cui, W. Ma, Y. Liu, A. Ishihama, A. Eisenstark, and A. K. Chatterjee. 1998. RpoS (sigma-S) controls expression of rsmA, a global regulator of secondary metabolites, harpin, and extracellular proteins in Erwinia carotovora. J. Bacteriol. 1803629-3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nassif, X., N. Honore, T. Vasselon, S. T. Cole, and P. J. Sansonetti. 1989. Positive control of colanic acid synthesis in Escherichia coli by rmpA and rmpB, two virulence-plasmid genes of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 31349-1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Navarre, W. W., S. Porwollik, Y. Wang, M. McClelland, H. Rosen, S. J. Libby, and F. C. Fang. 2006. Selective silencing of foreign DNA with low GC content by the H-NS protein in Salmonella. Science 313236-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nystrom, T. 2004. Growth versus maintenance: a trade-off dictated by RNA polymerase availability and sigma factor competition? Mol. Microbiol. 54855-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pratt, L. A., and T. J. Silhavy. 1996. The response regulator SprE controls the stability of RpoS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 932488-2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 71.Schmieger, H. 1972. Phage P22-mutants with increased or decreased transduction abilities. Mol. Gen. Genet. 11975-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sledjeski, D. D., and S. Gottesman. 1996. Osmotic shock induction of capsule synthesis in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 1781204-1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stout, V., and S. Gottesman. 1990. RcsB and RcsC: a two-component regulator of capsule synthesis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 172659-669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stout, V., A. Torres-Cabassa, M. R. Maurizi, D. Gutnick, and S. Gottesman. 1991. RcsA, an unstable positive regulator of capsular polysaccharide synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 1731738-1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Swords, W. E., and W. H. Benjamin, Jr. 1994. Mouse virulence gene A (mviA+) is a pleiotropic regulator of gene expression in Salmonella typhimurium. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 730295-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Swords, W. E., B. M. Cannon, and W. H. Benjamin, Jr. 1997. Avirulence of LT2 strains of Salmonella typhimurium results from a defective rpoS gene. Infect. Immun. 652451-2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Swords, W. E., A. Giddings, and W. H. Benjamin, Jr. 1997. Bacterial phenotypes mediated by mviA and their relationship to the mouse virulence of Salmonella typhimurium. Microb. Pathog 22353-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Takeda, S., Y. Fujisawa, M. Matsubara, H. Aiba, and T. Mizuno. 2001. A novel feature of the multistep phosphorelay in Escherichia coli: a revised model of the RcsC → YojN → RcsB signalling pathway implicated in capsular synthesis and swarming behaviour. Mol. Microbiol. 40440-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Taylor, R. K., V. L. Miller, D. B. Furlong, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1987. Use of phoA gene fusions to identify a pilus colonization factor coordinately regulated with cholera toxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 842833-2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Torreblanca, J., and J. Casadesús. 1996. DNA adenine methylase mutants of Salmonella typhimurium and a novel dam-regulated locus. Genetics 14415-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Torreblanca, J., S. Marqués, and J. Casadesús. 1999. Synthesis of FinP RNA by plasmids F and pSLT is regulated by DNA adenine methylation. Genetics 15231-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Torres-Cabassa, A. S., and S. Gottesman. 1987. Capsule synthesis in Escherichia coli K-12 is regulated by proteolysis. J. Bacteriol. 169981-989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tu, X., T. Latifi, A. Bougdour, S. Gottesman, and E. A. Groisman. 2006. The PhoP/PhoQ two-component system stabilizes the alternative sigma factor RpoS in Salmonella enterica. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10313503-13508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang, Q., Y. Zhao, M. McClelland, and R. M. Harshey. 2007. The RcsCDB signaling system and swarming motility in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium: dual regulation of flagellar and SPI-2 virulence genes. J. Bacteriol. 1898447-8457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wilmes-Riesenberg, M. R., J. W. Foster, and R. Curtiss, 3rd. 1997. An altered rpoS allele contributes to the avirulence of Salmonella typhimurium LT2. Infect. Immun. 65203-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yamashino, T., C. Ueguchi, and T. Mizuno. 1995. Quantitative control of the stationary phase-specific sigma factor, sigma S, in Escherichia coli: involvement of the nucleoid protein H-NS. EMBO J. 14594-602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zehnbauer, B. A., E. C. Foley, G. W. Henderson, and A. Markovitz. 1981. Identification and purification of the Lon+ (capR+) gene product, a DNA-binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 782043-2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhou, Y., and S. Gottesman. 2006. Modes of regulation of RpoS by H-NS. J. Bacteriol. 1887022-7025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhou, Y., S. Gottesman, J. R. Hoskins, M. R. Maurizi, and S. Wickner. 2001. The RssB response regulator directly targets σS for degradation by ClpXP. Genes Dev. 15627-637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhou, Y. N., W. A. Walter, and C. A. Gross. 1992. A mutant sigma 32 with a small deletion in conserved region 3 of sigma has reduced affinity for core RNA polymerase. J. Bacteriol. 1745005-5012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]