ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE

To understand cross-cultural hospital-based end-of-life care from the perspective of bereaved First Nations family members.

DESIGN

Phenomenologic approach using qualitative in-depth interviews.

SETTING

A rural town in northern Ontario with a catchment of 23 000 Ojibway and Cree aboriginal patients.

PARTICIPANTS

Ten recently bereaved aboriginal family members.

METHODS

Semi-structured interviews were conducted, audiotaped, and transcribed. Data were analyzed using crystallization and immersion techniques. Triangulation and member-checking methods were used to ensure trustworthiness.

MAIN FINDINGS

First Nations family members described palliative care as a community and extended family experience. They expressed the need for rooms and services that reflect this, including space to accommodate a larger number of visitors than is usual in Western society. Informants described the importance of communication strategies that involve respectful directness. They acknowledged that all hospital employees had roles in the care of their loved ones. Participants generally described their relatives’ relationships with nurses and the care the nurses provided as positive experiences.

CONCLUSION

Cross-cultural care at the time of death is always challenging. Service delivery and communication strategies must meet cultural and family needs. Respect, communication, appropriate environments, and caregiving were important to participants for culturally appropriate palliative care.

RÉSUMÉ

OBJECTIF

Comprendre le point de vue des membres des Premières nations concernant les soins palliatifs prodigués en fin de vie à un de leurs proches.

TYPE D’ÉTUDE

Approche phénoménologique utilisant des entrevues en profondeur qualitatives.

CONTEXTE

Une municipalité du nord de l’Ontario avec une population de 23 000 autochtones des nations des Ojibways et des Cris.

PARTICIPANTS

Dix autochtones ayant récemment vécu la mort d’un proche.

MÉTHODES

Les entrevues semi-structurées ont été enregistrées sur ruban magnétique et transcrites. Les données sont été analysées par des techniques de cristallisation et d’immersion. Des méthodes de triangulation et de vérification par les pairs ont été utilisées pour s’assurer de la fiabilité de l’analyse.

PRINCIPALES OBSERVATIONS

Les membres des familles des Premières nations voient les soins palliatifs comme une expérience touchant la communauté et la famille élargie. Ils ont souhaité avoir accès à des chambres et services respectant ces besoins, notamment un espace permettant d’accueillir plus de visiteurs que ce qui est habituel dans la société occidentale. Les participants ont souligné l’importance de stratégies de communication franches et respectueuses. Ils reconnaissaient que tous les employés de l’hôpital avaient un rôle dans les soins de leurs proches. Ils estimaient que les relations de leurs proches avec les infirmières et les soins que ces dernières prodiguaient étaient des expériences positives.

CONCLUSION

Prodiguer les soins aux mourants de culture différente pose toujours un défi. La prestation des services et les stratégies de communication doivent répondre aux besoins des familles et de leur culture. Pour les participants, respect, communication, milieux appropriés et bons soins étaient des aspects importants pour que les soins palliatifs respectent leur culture.

Most patients die in hospital1; this is close to home and culturally appropriate for many urban and rural patients. For First Nations patients from distant communities, however, dying in a hospital means being far from home and family, and being in an unfamiliar cultural milieu. We wanted to understand what the hospital experience was like from the perspective of bereaved First Nations family members. The results from this study have helped us gain an understanding of what our facility is doing well and what could be improved. The participants’ experiences will inform future program development by incorporating changes in services, cultural practices, and physical surroundings.

The Meno Ya Win Health Centre in northwestern Ontario has been designated as a centre of excellence for aboriginal care.2 The hospital’s mission is based on culturally responsive values, providing traditional healing options, interpreter services, and traditional foods.3 Its new facilities, slated to open in 2010, will include a smudge room and a palliative care area large enough for extended family. Information gleaned from this study will complement the centre’s approach to care and optimal palliative care services for aboriginal patients in this region.

International qualitative studies document the common aboriginal preference to die at home.4–8 Limitations in community resources hinder this option in remote areas.9–11 Despite the fact that many aboriginal patients die in hospital, few studies provide practical knowledge that can be applied to their hospital-based care. This is the first study to explore hospital-based end-of-life (EOL) care from the perspective of aboriginal family members.

Many interconnected factors challenge high-quality EOL care for First Nations patients. Geographic, communication, cultural, and institutional issues can all be involved.12 A 2007 Canadian literature review of aboriginal EOL care identified the main themes: family and community values, traditional and holistic concepts of health and dying, respectful communication, and the challenges surrounding geographic isolation.13

Literature review

Researchers in 2 previous studies of nonaboriginal patients interviewed family members to assess quality of EOL care14,15: one study identified trust in the treating physician14 as the most important element while the other found physician honesty ranked first.15 Three studies assessing aboriginal EOL care performed community-based assessments.4,6,8 Hotson and colleagues’ interviews with key informants in remote First Nations communities in northern Manitoba identified patient relocation and isolation from family members as important challenges. Hotson et al recommended improving access to family supports.4 Distance from family was the main theme that emerged from Prince and Kelley’s focus groups and surveys in 10 northwestern Ontario First Nations communities.6 The Helping Hands Program in Alaska addressed similar challenges faced by aboriginal residents of remote communities by creating the infrastructure to provide more of them with the option of dying at home.6 McRae and collegues’ study, which interviewed 13 aboriginal and nonaboriginal families about EOL services, on Manitoulin Island in 2000 found that access to care and symptom control were issues.16

In a 2006 multicity study of urban Canadian palliative care services, Heyland et al found communication with family members and other health professionals was problematic, particularly when transferring care out of hospital. They found in general that delivery of EOL care was rated as poor by family members when their loved ones were treated in tertiary care centres. They recommended multiple areas of improvement, including intensive care unit residency training in EOL care.14

Communication and culture

Contrasting styles of communication can complicate care. A qualitative study by Kelly and Brown looked at communicating with First Nations patients in northwestern Ontario and discussed the use of nonverbal communication with an emphasis on listening and accepting silence.17 Similarly, McGrath’s qualitative study of pain management signaled the need to attend to nonverbal cues when assessing levels of pain in Australian aboriginal patients.18 Several articles discuss the role of interpreters in facilitating cross-cultural communication.9,10,19–21 Interpreters often act as advocates and mediators between different sets of values and are therefore a source of empowerment for patients.15–18 Kaufert and Smylie both describe the disadvantages of family members acting as medical interpreters, including the possibility that they might not inform patients of bad news.10,22

Cultural and institutional barriers negatively affect aboriginal EOL care. Kaufert and O’Neil describe the fundamental conflict that dying in hospital presents for some First Nations patients.9,10,23 Traditional values regarding family and community imply taking care of each other until death.9,10 Additionally, hospital policies might pose barriers to traditional practices and cultural grieving processes.4–7,9 Restrictions on number of visitors and time limitations challenge the valued aboriginal tradition of being surrounded by the entire family throughout the EOL stages.6,7,12 Traditional practices such as sweet grass ceremonies and smudging are often prohibited.23

There is a recent emergence of dialogue and initiatives among organizations. The Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association,1 Assembly of First Nations,24 and the National Aboriginal Health Association25 have released documents and recommendations for improving EOL services for First Nations patients.

METHODS

Participants

Ten aboriginal family members whose relatives had died at the Meno Ya Win Health Centre in Sioux Lookout, Ont, consented to interviews. They were considered key informants who would share their experiences and thoughts. We were limited by the availability of informants who lived near Sioux Lookout or who were visiting the community from the north. Participants’ family members had received palliative care as recently as several months and up to several years before the interviews. Most had family members who had received such care within the past year. All had lost a parent or spouse. They gave us either written consent or verbal audio-taped consent. Participants were given access to a confidential grief counselor if they felt so inclined after the interviews. Ethics approval was granted by the Meno Ya Win Health Centre Research Review Committee.

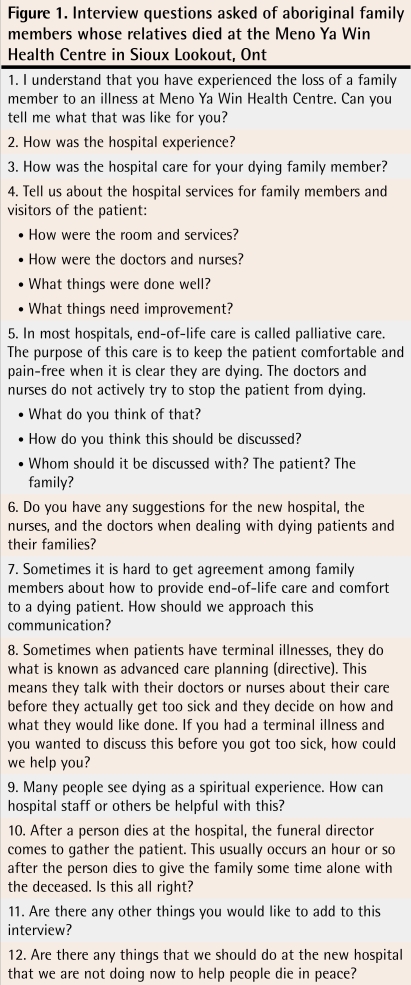

Data gathering

The semi-structured interview questions were developed in a bicultural, interdisciplinary setting (Figure 1). The interviews were conducted in English with some Ojibway-Cree words intermingled. The 2 interviewers were experienced nurses with extensive backgrounds in palliative care and they had not been involved in the care of the patients. Each interview was conducted by a single interviewer, accompanied by a research assistant who looked after the audiotaping, took field notes, and ensured that no topics went uncovered. One participant consented to field notes only without audiotaping.

Figure 1.

Interview questions asked of aboriginal family members whose relatives died at the Meno Ya Win Health Centre in Sioux Lookout, Ont

The research design team was an interdisciplinary and cross-cultural group of researchers. The process was informative from the start. We decided not to include questions about organ donation. We learned from the First Nations members of the team that discussing organ donation would distract from exploring EOL care.

Data analysis

The interviews were analyzed by 4 researchers independently. There was 1 collating analyst. The interviews were subjected to immersion and crystallization, using a phenomenologic approach. By steeping themselves in the documents, the analysts were able to understand and experience some of the feelings expressed by the participants. Beyond this triangulation of researchers, member checking with the interviewers was undertaken to ensure trustworthiness.

FINDINGS

Three themes arose from content analysis of the transcripts: communication, caregiving, and environment (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Themes of end-of-life care for First Nations people

Communication

Communication was the most extensively discussed participant issue and included communication with or between physicians, family members, and interpreters.

Communication with physicians

Bereaved aboriginal family members expressed the need for physicians to communicate directly: “The doctor … he was helpful and telling us straight out that it was terminal.” They wanted physicians to communicate respectfully and to take the time:

I guess it’s all part of our culture with respecting a dying person.

The underlying principle of the health care system has to be respect—respect for the differences we have. For me, that’s the underlying principle of the work of the hospital.

They wanted communication to include words of encouragement:

The most encouraging words I heard was when she died, a doctor said that she wasn’t defeated by the cancer. Every day she fought to be with us. It didn’t defeat her. It’s the words that people use with us.

They did not want false hope:

I think that the facts are good and not giving the patient false hope.

[One physician] was different from the others. He gave a false sense of hope. I didn’t like that.

The doctor told me that [my spouse] had 6 months to a year, and she didn’t even last a month.

The value of experienced physicians was identified:

It depends on the individual [physician] and how much they know of the people and how long they’ve been around here, you know. If they know our ways and, you know. I think those are the better doctors for an elderly [patient] dying rather than a new student coming in from medical school.

Not all feedback on communication was positive:

I didn’t see enough, personally, like the doctor coming in enough to give us information.

The doctors were very busy, especially the specialists in the city. There was one that would come in and then leave without telling us what he found. Until we asked, then he took the time to explain. I thought he probably thinks that we don’t have a good grasp of the English language that we wouldn’t understand the medical terminology and that he thought his time would be wasted on us. That bothered me. I know they are overrun but as long as they take the time. We need to know what’s going on throughout, because it’s a progressive disease.

Communication within the family

End-of-life care is a stressful time for families:

Like, when it comes to that point of somebody dying and I wonder why they [the families] choose to have a big fight then.

It’s very hard when there is fighting.

For other families things went smoothly:

I don’t think me and my family really had any chances to disagree on anything. Just whatever one person said, we just went along with it, that way things just went smoother.

I think it is to support each other in the family and if you have a disagreement … I think there has to be one spokesperson for the family as hard as that is. One to make the decisions.

Culture played a role in family communication and decision making:

It’s always the elder we go to, in our family anyways, and in most other families that I know.

I find with Native people … that they don’t want to say this or that. They don’t want to make choices, especially when the person that is dying is not in that right state of mind.

Advanced care planning

Research questions about advanced care planning were not particularly fruitful. They did, however, lead to elaboration on individual family decision styles. Some patients gave specific instructions to the family:

We didn’t have any decisions to make. She had it all planned out and it was easier for us.

She prepared and told us what to do after she was gone …. She told me how to make a white kerchief for her, just to use the white material.

For other families, however, not speaking of illnesses was the tradition:

She didn’t know she had cancer. I don’t think she ever really found out what was wrong with her. They asked my dad. My dad decided not to tell her. It was too far along. Dad didn’t want her to know. I don’t think that was a good thing to do.

In a Native way, nobody really doesn’t make those kind of plans.

I think it is difficult for us because we see so many unnatural deaths, people dying so early and this causes fear. People think that the more they talk about it, it will come.

Interpreters or translators

One of the key elements of communication with aboriginal patients was the use of interpreters. Family members were able to speak in the language of their relatives, but they expressed concern when interpreters were not available:

Most of the elders cannot express what they need .... The only people that can really talk to the patient … are the interpreters.

I would often think that the people taking care of her could know what she was saying in her language. She would compliment and encourage them and I wish they could have heard it. I think it would mean something to them.

She got upset all the time and she was crying and would say, “When I want to talk to someone that speaks my language …” Or “If I want to go to the bathroom …” You know, things like that.

Interpreters played a role in EOL care that went beyond language translation: “Interpreters are not really trained to be palliative … a lot of people are uncomfortable.”

Caregiving

The second theme was caregiving. Participants were generally comfortable with the symptom control their family members received and almost always had positive comments about the care:

You know that she was going to die but you’re really happy when the doctors and nurses come, even though you know there’s nothing they can do for her. You feel relief when they come because it shows they care.

Nursing care

Family members made the following statements about the nurses:

Everybody looked after him. The nurses were very good.

I found that the hospital staff, the nurses, and doctors were all very supportive of our family.

I still talk to all the nurses that were helping my mom. They were really friendly … [but] it always seems like there’s one nurse that just kinda makes it a bit difficult.

Spiritual care

Spiritual care was mentioned as important by most families:

Because Nishnabe believe in the bible, they [Nishnabe people] believe I don’t know what else they believe in. But it’s different for everyone and that we should respect.

The minister was here all the time and she brought communion every Sunday and the traditional people would come in and do that too.

Praying and singing were often synonymous:

Patients … ask me if I can pray or if I can sing [with them].

And there were a few people that were around his place and they were able to play the guitar and those things—in the hospital—and nobody complained about that either, even all the nurses, and we asked .… Everybody liked it. Even some patients want to come out in the hallway to listen to it, to hymns and guitar.

With us, her death was at 5 AM and they took the body at 9 AM. We sat with the body and had prayers. My sisters and I would sing. The nurses told us we were too noisy for the others across the room. That’s what we do when somebody dies.

Attendance after death

Families expressed a need for flexibility in removal of the remains of their loved ones after passing. This often meant personal or family time, or consideration for relatives traveling from the north:

We were told it was up to us when the body was removed. I needed that. I needed to wait until all my children came in. Two of my children came after midnight.

I know there are times when we’ve had the deceased laying there for more than 3 hours, just so that we can meet the family’s requests .… I think the hospital is good with families in that respect, for giving them their room and their privacy during this time.

The elders will place the body in a certain way. They have different practices and the [hospital staff] have to be aware of that … allow people to create the environment they want.

Death at home

Although we were asking about hospital EOL care, the option of dying at home came up:

The doctor told me 3 days before he knew that it was almost time and I should make arrangements for her to go back up north. But then I talked to her. She said, “I’ll just stay here and let the nurses take care of me.”

Other elders I have worked with, they have asked to go home and they wanted to die at home. Mom could have gone home, but we were here and she seemed quite happy. But with my aunt, she said, “Now that I know I’m dying, I want to go home and see my children and my grandchildren. I haven’t seen them in a long time.” I’m glad she got home because she could still remember. She could still see. So I’m glad it was possible for her.

Environment

Appropriate facilities

Aboriginal EOL care involves the whole family and other community members, so the facility needs to comfortably accommodate such large groups. In many ways, the culture combines the Western practice of a wake and EOL care.

Especially in our culture, towards the end you need more people. We want not just the family, but friends there too. Not just immediate family.

She would name names and then we would call them and they would come down. We would have 20 people in the room and that was really hard because there was no room for us all. She wanted us there all the time.

Like with Native people, even when we have family dying at home, there are always people at night that want to be there with family. It would be nice to have a room just for that so they don’t disturb anyone else and that they have their privacy and make sure the patient sleeps well at night.

Kitchen service

When family member participants were asked general questions about hospital services, they all lauded the practice of the kitchen staff and nurses arranging refreshment trays of tea and cookies. Sharing tea is a part of common social discourse.

I believe the hospital was really good to us at that time. They provided us with tea, you know, because we knew Dad’s time was short, so we didn’t have to go very far to have a cup of tea and I really appreciated that.

Involvement of all hospital staff

Just as the whole family played a role in EOL care, bereaved participants identified that all of the hospital staff were involved in EOL care.

Because all staff are affected, you know, when someone is dying on the floor or even patients down the hall kinda know. They can sense that something is happening. I think that everybody should be educated on the circle of life.

At times I saw how the people at the hospital were affected by her passing. I now think that I should have reached out to the caregivers and [told] them that we were grateful and to acknowledge them.

DISCUSSION

Our study confirmed some things that we already knew about our institution: our rooms are too small for large extended family visiting palliative patients and visiting hours inhibit family attendance. We were surprised to learn that the long-established practice of bringing tea and cookies to family members was universally praised. This practice was developed over the years by our nursing and kitchen staff with no formal program, without us noticing its positive effect on families.

We discovered that the extended family and community were important members of the care and attendance team—as identified in the 2007 literature review by Kelly and Minty.13 Our findings brought us a step closer to understanding that the whole hospital staff is also involved in the delivery of palliative care, including the kitchen and housekeeping staff. In our small hospital, First Nations palliative care is not only a whole family event, but also a whole hospital staff experience. This was particularly true for the interpreters who were identified as key personnel involved in EOL care; as Kaufert et al documented, they function as cultural navigators as well as translators.20

We now recognize that all hospital staff are involved, and they might need training and debriefing. We further outlined that the physical environment needs to accommodate reasonably large numbers of extended family members, who appreciate some privacy and kitchen service.

It was no surprise that communication arose as a theme, which it often does in patient care. We discovered several specific issues: false hope was not appreciated by family members; insufficient physician communication was sometimes ascribed to possible physician misperception that the aboriginal patient or family member might not understand his or her explanation; and family members preferred direct, respectful communication. Respect, music, and spirituality were all perceived to be part of good caregiving, which had previously been documented in the aboriginal literature.7,13

Unlike the studies by Heyland et al14 and McRae et al,16 symptom control was not identified as an issue. This might be because it was appropriately managed or that it was not attested to by participants, despite the use of probe questions relating to it.

Limitations and directions for future research

Our study is limited by the fact that our participants were all local, and these results might not apply to other palliative care providers in other First Nations regions. We have learned many important lessons to guide us to move forward in an area that might always remain challenging. Our interviews took place in English, although we offered translation services if needed. Because we interviewed locally represented English-speaking family members, we might have missed issues specific to non–English-speaking families and missed concerns of distant families, as geographic distance might create additional issues.

Future research should include understanding the question of First Nations organ donation—perhaps a focus group with our hospital Elders Council could help understand this issue. We are contemplating instituting a brief telephone follow-up 2 to 3 weeks after the death of a palliative care patient from our institution to ensure quality of palliative care and ongoing learning.

Conclusion

Family members generally believed their loved ones received good nursing and medical care in our rural hospital. They emphasized the importance of respectful care. This involves directness in communication, assisting intrafamily communication, and frequent use of interpreters when needed.

Caregiving should include access to various spiritual modalities, compassionate nursing care, and allowing time with the deceased after death.

The facility needs to allow for large groups of extended family to spend time with dying patients. Because all hospital staff might be affected, palliative care training should be universally available. These findings will inform the planning and program development of the new Meno Ya Win Health Centre, opening in 2010.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Aboriginal family members of palliative care patients emphasized the importance of respectful and compassionate care. Their experiences outline the need for changes in services and physical surroundings.

Involvement of the whole hospital staff (eg, housekeeping, kitchen staff) is important in the delivery of palliative care; as such, palliative care training should be universally available.

Palliative care of First Nations people will always remain a challenge. Ongoing learning is required in order to move forward in this area.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Les proches des patients autochtones en soins palliatifs ont insisté sur l’importance du respect et de la compassion dans les soins. Leur expérience souligne la nécessité de changements dans les services et l’environnement physique.

Il est important que tout le personnel hospitalier (incluant celui de l’entretien et de la cuisine) participe aux soins palliatifs; en ce sens, la formation en soins palliatifs devrait être accessible à tous.

Prodiguer des soins palliatifs aux personnes des Premières nations constituera toujours un défi. Tout progrès dans ce domaine devra s’appuyer sur une formation continue.

Footnotes

Contributors

Dr Kelly designed the overall study and wrote all drafts. Ms Linkewich and Ms Cromarty helped design the semi-structured questions, did the interviews, and approved theme extraction. Ms St Pierre-Hansen attended, recorded, and analyzed all interviews, and assisted in writing drafts. Drs Antone and Gilles assisted in the development of questions and analyzed the interviews. All authors approved the final draft.

Competing interests

None declared

This article has been peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association. Moving forward by building on strengths: a discussion document on aboriginal hospice palliative care in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Hanson and Associates; 2007. [Accessed 2009 Jan 26]. Available from: www.chpca.net/interest_groups/aboriginal_issues/AHPC_Final_Paper_March_29_2007_English.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care [website] Government of Canada announces funding for the Sioux Lookout Meno-Ya-Win Health Centre. Toronto, ON: Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2005. [Accessed 2009 Jan 26]. Available from: www.health.gov.on.ca/english/media/news_releases/archives/nr_05/nr_091305. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meno Ya Win Health Centre [website] Traditional healing, medicine, foods and support program. Sioux Lookout, ON: Meno Ya Win Health Centre; 2009. [Accessed 2007 Sep 4]. Available from: www.slmhc.on.ca/downloads/MYWConfDisplayPOS-August2006.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hotson KE, Macdonald S, Martin B. Understanding death and dying in select First Nations communities in northern Manitoba: issues of culture and remote service care delivery in palliative care. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2004;63(1):25–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGrath P. ‘I don’t want to die in that big city; this is my country here’: research findings on Aboriginal peoples’ preference to die at home. Aust J Rural Health. 2007;15(4):264–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2007.00904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prince H, Kelley ML. Palliative care in First Nations communities: the perspectives and experiences of Aboriginal elders and the educational needs of their community caregivers. Thunder Bay, ON: Lakehead University; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGrath P, Holewa H. Australia: Researchman; 2006. The “living model.” A resource manual for indigenous palliative care service delivery. Toowong. [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeCourtney CA, Jones K, Merriman MP, Heavener N, Branch PK. Establishing a culturally sensitive palliative care program in rural Alaska Native American communities. J Palliat Med. 2003;6(3):501–9. doi: 10.1089/109662103322144871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaufert J, O’Neil J. Cultural mediation of dying and grieving among Native Canadian patients in urban hospitals. In: DeSpelder LA, Strickland AL, editors. The path ahead: readings in death and dying. Palo Alto, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company; 1995. pp. 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaufert J. Cultural mediation in cancer diagnosis and end-of-life decision-making: the experience of Aboriginal patients in Canada. Anthropol Med. 1999;6(3):405–21. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGrath P. Exploring Aboriginal people’s experience of relocation for treatment during end-of-life care. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2006;12(3):102–8. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2006.12.3.20692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smylie J. A guide for health professionals working with aboriginal peoples: executive summary. J SOGC. 2000;22(12):1056–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly L, Minty A. End-of-life issues for aboriginal patients: a literature review. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53:1459–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heyland D, Dodek P, Rocker G, Groll D, Gafni A, Pichora D, et al. What matters most in end-of-life care: perceptions of seriously ill patients and their family members. CMAJ. 2006;174(5):627–33. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wenrich MD, Curtis JR, Shannon SE, Carline JD, Ambrozy DM, Ramsey PG. Communicating with dying patients within the spectrum of medical care from terminal diagnosis to death. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(6):868–74. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.6.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McRae S, Caty S, Nelder M, Picard L. Palliative care on Manitoulin Island. Views of family caregivers in remote communities. Can Fam Physician. 2000;46:1301–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly L, Brown JB. Listening to Native patients. Changes in physicians’ understanding and behaviour. Can Fam Physician. 2002;48:1645–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGrath P. “The biggest worry...”: research findings on pain management for Aboriginal peoples in Northern Territory, Australia. Rural Remote Health. 2006;6(3):549–63. Epub 2006 Jul 10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaufert J, O’Neil J. Biomedical rituals and informed consent: Native Canadians and the negotiation of clinical trust. In: Weisz G, editor. Social science perspectives on medical ethics. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1989. pp. 41–63. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaufert JM, Putsch RW, Lavallée M. Experience of Aboriginal health interpreters in mediation of conflicting values in end-of-life decision making. Int J Circumpolar Health. 1998;57(Suppl 1):43–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaufert J, Putsch RW, Lavallée M. End-of-life decision making among Aboriginal Canadians: interpretation, mediation, and discord in the communication of “bad news. J Palliat Care. 1999;15(1):31–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smylie J. A guide for health professionals working with aboriginal peoples: cross cultural understanding. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2001;23(2):157–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Neil J. Referrals to traditional healers: the role of medical interpreters. In: Young D, editor. Health care issues in the Canadian north. Edmonton, AB: Boreal Institute for Northern Studies; 1988. pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Assembly of First Nations. First Nations action plan on continuing care. Ottawa, ON: Assembly of First Nations; 2005. [Accessed 2009 Jan 26]. Available from: www.afn.ca/cmslib/general/CCAP.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Aboriginal Health Organization. Discussion paper on end of life care for aboriginal peoples. Ottawa, ON: National Aboriginal Health Organization; 2002. [Accessed 2009 Jan 26]. Available from: www.naho.ca/english/pdf/re_briefs2.pdf. [Google Scholar]