Abstract

Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) can regulate the activity of many neurotransmitter pathways throughout the central nervous system and are considered important modulators of cognition and emotion. nAChRs also are the primary site of action in the brain for nicotine, the major addictive component of tobacco smoke. nAChRs consist of five membrane-spanning subunits (α and β isoforms) that can associate in various combinations to form functional nAChR ion channels. Because of a dearth of nAChR subtype-selective ligands, the precise subunit composition of the nAChRs that regulate the rewarding effects of nicotine and the development of nicotine dependence are unknown. However, the advent of mice with genetic nAChR subunit modifications has provided a useful experimental approach to assess the contribution of individual subunits in vivo. Here we review data generated from nAChR subunit knockout and genetically modified mice supporting a role for discrete nAChR subunits in nicotine reinforcement and dependence processes. Importantly, the rates of tobacco dependence are far higher in patients suffering from comorbid psychiatric illnesses compared with the general population, which may at least partly reflect disease-associated alterations in nAChR signaling. An understanding of the role of nAChRs in psychiatric disorders associated with high rates of tobacco addiction, therefore, may reveal novel insights into mechanisms of nicotine dependence. Thus, we also briefly review data generated from genetically modified mice to support a role for discrete nAChR subunits in anxiety disorders, depression, and schizophrenia.

Keywords: Nicotine, nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, knockout, acetylcholine, addiction, anxiety, depression, schizophrenia

Cigarette smoking is one of the largest preventable causes of death and disease in developed countries. Nevertheless, approximately 24% of adults were current smokers in the United States in 1997-1998 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2002). Tobacco-related disease is responsible for approximately 440,000 deaths annually and results in approximately $160 billion in health-related costs in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2002). Moreover, by 2020, tobacco-related disease is projected to become the largest single health problem worldwide, resulting in approximately 8.4 million deaths each year (Murray and Lopez, 1997). Despite the well-known negative health consequences associated with the tobacco smoking habit, only about 10% of smokers who attempt to quit annually remain abstinent after 1 year.

Nicotine contained in tobacco smoke is one of the most widely consumed psychotropic agents in the world. Nicotine is considered the primary reinforcing component of tobacco responsible for addiction in human smokers (Stolerman and Jarvis, 1995). Nevertheless, many other components of tobacco smoke also may contribute to tobacco addiction, perhaps by increasing the reinforcing effects of nicotine (Fowler et al., 1996; Agatsuma et al., 2006; Guillem et al., 2006; Rose, 2006; Villegier et al., 2007; Guillem et al., 2008). Consistent with a role for nicotine in the tobacco smoking habit, nicotine elicits a positive affective state in both human smokers and non-smokers (Barr et al., 2007; Sofuoglu et al., 2008) and is self-administered by humans (Henningfield et al., 1983; Rose et al., 2003; Sofuoglu et al., 2008), non-human primates (Goldberg et al., 1981; Le Foll et al., 2007), and rodents (Corrigall and Coen, 1989; Picciotto et al., 1998; Watkins et al., 1999).

Importantly, the tobacco smoking habit may depend not only on the positive reinforcing actions of nicotine, but also on escape from the aversive consequences of nicotine withdrawal (i.e., negative reinforcement) (Doherty et al., 1995; Kenny and Markou, 2001; George et al., 2007). Prolonged tobacco consumption can result in the development of nicotine dependence, and smoking cessation can elicit an aversive withdrawal syndrome in nicotine-dependent human smokers (Shiffman and Jarvik, 1976; Hughes et al., 1991). The duration and severity of nicotine withdrawal may predict relapse in abstinent human smokers (Piasecki et al., 1998; Piasecki et al., 2000; Piasecki et al., 2003). Furthermore, the efficacy of nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation may be related to the reduction of nicotine withdrawal in abstinent smokers, at least in certain individuals (Fagerstrom, 1988; Sachs and Leischow, 1991).

Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) are the primary site of action for nicotine in the brain. As such, nAChRs are considered important targets for the development of therapeutic agents that may facilitate smoking cessation efforts. For example, varenicline (Chantix), a partial agonist at nAChRs, was approved recently by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a pharmacological aid for smoking cessation and is effective in preventing relapse to tobacco smoking during abstinence (Gonzales et al., 2006; Jorenby et al., 2006; West et al., 2007). Thus, identification of the nAChRs at which nicotine acts in the brain to elicit its reinforcing effects, and also the nAChRs at which nicotine acts to induce the development of dependence and expression of withdrawal, may provide valuable insights into the neurobiology of the nicotine habit in human tobacco smokers and facilitate the development of novel therapeutic strategies for the treatment of tobacco addiction (for review, see Domino, 2000). However, little is known regarding the nAChR subtypes that regulate the reinforcing actions of nicotine in vivo. This lack of knowledge reflects an absence of small-molecule ligands that are selective for specific nAChR subtypes. Although many nAChR ligands may be more selective for certain nAChR subtypes, they nonetheless exhibit binding affinities for other nAChR subtypes. Therefore, attributing any particular behavioral effect of nicotine to an action at a discrete nAChR subtype has been difficult. The construction of genetically modified mice with null mutations in the genes that encode individual nAChR subunits offers a promising approach to identifying the nAChR subtypes that regulate the actions of nicotine in vivo and the contribution of specific nAChR subtypes to physiology and disease. Indeed, as summarized in Table 1, nAChR mutant mice have been employed extensively over recent years to examine the roles of nAChR subunits in a broad range of physiological processes. Although the use of knockout mice is a promising strategy, certain limitations should be taken into account with interpretation of the data. First of all, the animal has been without the gene for the duration of development, and physiological compensation may have occurred. For example, the α7 knockout exhibits increased expression of both the α3 and α4 subunits (Yu et al., 2007), whereas the β3 knockout displays decreased α6 subunit expression (Gotti et al., 2005). Secondly, primary effects on behavior may be noted in secondary measures. For instance, decreased open field activity may be indicative of increased anxiety, rather than decreased locomotion. In this respect, it is important to employ varying techniques and behavioral measures to fully address the research questions. Until the development of more sophisticated methods that afford precise control over anatomical and temporal factors, as well as the pharmacological development of specific ligands, knockout mice remain an essential tool in defining the mechanisms underlying addiction processes. In this review, we will outline the progress that has been made in identifying nAChR subunit components of the nicotinic receptors that regulate the rewarding properties of nicotine, as well as those that contribute to nicotine dependence and withdrawal. In particular, we will highlight those studies that have utilized mice with genetic modifications of nAChR subunits.

Table 1.

Behavioral and pharmacological effects of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit knockout in mice (in vivo only; no binding studies included).

| Knockout | Baseline phenotype | Effects of nicotine in knockout vs. wildtype | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| α3 | impaired growth dilated pupils do not constrict to light enlarged bladder, dribbling urination, urinary tract infection, bladder stones lethal postnatal (1 day to 3 months) |

lack of nicotine-induce bladder contractility | (Xu et al., 1999a) |

| α4 | ↑ locomotor activity ↑ sniffing ↑ rearing ↑ striatal dopamine levels ↑ CD40-stimulated B lymphocytes ↑ dopamine neuron terminal arbors ↓ exploration in elevated plus maze ↓ serum IgG ↓ IgG-producing cells in spleen |

↑ recovery from nicotine-induced depression of locomotor activity ↓ antinociception ↓ raphe magnus neuronal response ↓ thalamic neuronal response ↓ tolerance to hypothermia ↓ locomotor activity no nicotine-induced ↑ in dopamine release — dopamine neuron terminal arbor size — dopamine transporter immunoreactivity in dorsal striatum |

(Marubio et al., 1999; Ross et al., 2000; Marubio et al., 2003; Parish et al., 2005; Skok et al., 2005; Tapper et al., 2007) |

| α5 | ↓ α3 receptor expression ↑ experimental colitis normal hearing normal spiral ganglion neurons |

↑ seizure activity ↓ seizure activity no effect in open field ameliorates colitis |

(Salas et al., 2003a; Kedmi et al., 2004; Bao et al., 2005; Orr-Urtreger et al., 2005) |

| α6 | not tested | not tested | (Champtiaux et al., 2002) |

| α7 | ↑— y-maze activity ↑ open-field activity ↑ sympathetic response (↑ heart rate) to sodium nitroprusside-induced vasodilation ↑ CD40-stimulated B lymphocytes ↑ α4 receptors ↑ α3 receptors ↓ appetitive learning ↓ serum IgG ↓ delayed-matching-to-place performance ↓ IgG-producing cells in spleen ↓ 5-choice serial reaction time task performance (i.e., ↑ impulsivity) ↓ limbic c-fos expression induced by α7 agonist ↓ β-amyloid1-41-induced dopamine release in prefrontal cortex — sperm number, morphology, viability — dopamine neuron firing rate/bursts — brain injury-induced tissue loss or brain inflammation — object recognition task no facilitatory effect of α7 agonist in object recognition task |

— somatic signs of withdrawal — operant responding for nicotine — 5-choice serial reaction time task performance — antinociception in tail flick test — increase in spinal calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II ↓ hyperalgesia during withdrawal ↓ sperm motility ↓ B lymphocytes in spleen ↓ dopamine neuron firing rate/bursts exhibit conditioned place preference — contextual cued fear conditioning — trace cued fear conditioning — nicotine withdrawal-induced deficits in contextual fear conditioning |

(Franceschini et al., 2000; Tritto et al., 2004; Bowers et al., 2005; Bray et al., 2005; Grabus et al., 2005; Keller et al., 2005; Naylor et al., 2005; Skok et al., 2005; Fernandes et al., 2006; Hoyle et al., 2006; Kelso et al., 2006; Mameli-Engvall et al., 2006; Walters et al., 2006; Damaj, 2007; Hansen et al., 2007; Pichat et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2007; Yu et al., 2007; Portugal et al., 2008) |

| α9 | ↓ number of outer hair cells in cochlea ↓ olivocochlear function abnormal cochlear terminal morphology |

not tested | (Vetter et al., 1999) |

| β2 | ↑ passive avoidance latency ↑ corticosterone levels ↑ visual response latency ↑ preference for higher temporal frequencies ↑ contrast sensitivity ↑ CD40-stimulated B lymphocytes ↑ B lymphocytes in bone marrow ↓ freezing in tone-conditioned fear (aged mice) ↓ visual acuity at cortical level ↓ locomotor activity in familiar environment ↓ hippocampal pyramidal neurons ↓ spatial learning ↓ serum IgG ↓ IgG-producing cells in spleen ↓ spiral ganglion neurons ↓ dopamine neuron firing rate/bursts ↓ antidepressant-like effect of mecamylamine in forced swim test abnormal cholinergic transmission neural tissue atrophy neocortical hypotrophy astrogliosis microgliosis hearing loss do not self-administer intra-VTA nicotine self-administer intra-VTA morphine normal nicotine withdrawal syndrome normal β-amyloid1-41-induced dopamine release in prefrontal cortex |

↑ locomotor activity (initial low dose) — locomotor activity (repeated high dose) ↑ body temperature (initial low dose) — body temperature (repeated high dose) ↑ passive avoidance latency ↓ startle ↓— nicotine self-administration ↓ dopamine response in substantia nigra ↓ dopamine response in ventral tegmental area ↓ thalamic neuronal response ↓ raphe magnus neuronal response ↓ antinociception ↓ CD40-stimulated B lymphocytes ↓ B lymphocytes in bone marrow ↓ antinociception in tail flick test ↓ increase in spinal calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II ↓ contextual cued fear conditioning ↓ trace cued fear conditioning ↓ nicotine withdrawal-induced deficits in contextual fear conditioning — B lymphocytes in spleen — dopamine neuron firing rate/bursts no conditioned place preference |

(Picciotto et al., 1995; Marubio et al., 1999; Zoli et al., 1999; Caldarone et al., 2000; Rossi et al., 2001; Owens et al., 2003; Grubb and Thompson, 2004; King et al., 2004; Tritto et al., 2004; Bao et al., 2005; Skok et al., 2005; Besson et al., 2006; Mameli-Engvall et al., 2006; McCallum et al., 2006; Rabenstein et al., 2006; Skok et al., 2006; Walters et al., 2006; Damaj, 2007; Davis and Gould, 2007; Wu et al., 2007; Portugal et al., 2008) |

| β3 | ↑ open field activity ↓ prepulse inhibition of startle ↓ nigrostriatal dopamine release ↓ α6 receptor expression |

↑ striatal dopaminergic transmission | (Cui et al., 2003; Gotti et al., 2005) |

| β4 | ↑ heart rate ↑ exploration in elevated plus maze ↑ activity in stair case test ↓ α3 receptor expression impaired bladder contractility ↓ core body temperature |

↓ seizure activity ↓ somatic withdrawal signs ↓ hyperalgesia ↓ hypothermic response |

(Xu et al., 1999b; Salas et al., 2003b; Kedmi et al., 2004; Sack et al., 2005) |

| α5β4 | ↓ α3 receptor expression | ↓ seizure activity | (Kedmi et al., 2004) |

| α7β2 | ↑ rotarod performance ↓ passive avoidance latency |

(Marubio and Paylor, 2004) | |

| β2β4 | dilated pupils do not contract to light impaired bladder contractility, enlarged bladder, dribbling urination, urinary tract infection, bladder stones lethal at 1-3 weeks postnatal |

not tested | (Xu et al., 1999b) |

↓, decreased measure; ↑, increased measure; —, no change; parts of the table are reproduced with permission from (Koob and Le Moal, 2006), and modified and updated from (Cordero-Erausquin et al., 2000).

Strong epidemiological evidence suggests that the rate of tobacco dependence is far higher in individuals who suffer from psychiatric illnesses, such as anxiety disorders, depression, or schizophrenia, compared with the rate of tobacco dependence observed in the general population (Dani and Harris, 2005). Thus, the increased susceptibility to tobacco addiction in patients with comorbid psychiatric illness may reflect disease-associated deficits in nAChR signaling. An alternative, but not mutually exclusive, explanation is that smoking represents an attempt at self-medication of disease-associated symptoms through consumption of nicotine (see below for more detailed discussion of these possibilities). Based on these observations, the role of nAChRs in psychiatric disorders associated with high levels of tobacco addiction is an important consideration because such knowledge may reveal important clues regarding the role and identity of nAChR subtypes in nicotine dependence and disease states. We also will briefly discuss recent advances in our knowledge related to the role of nAChRs in anxiety disorders, depression, and schizophrenia, again focusing on data generated from mice with genetic modifications of nAChR subunits. Throughout this paper, the asterisk (*) annotation beside a specific subunit denotes a nAChR that contains the indicated subunit but for which the complete subunit composition is unknown.

Structural architecture and brain distribution of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors

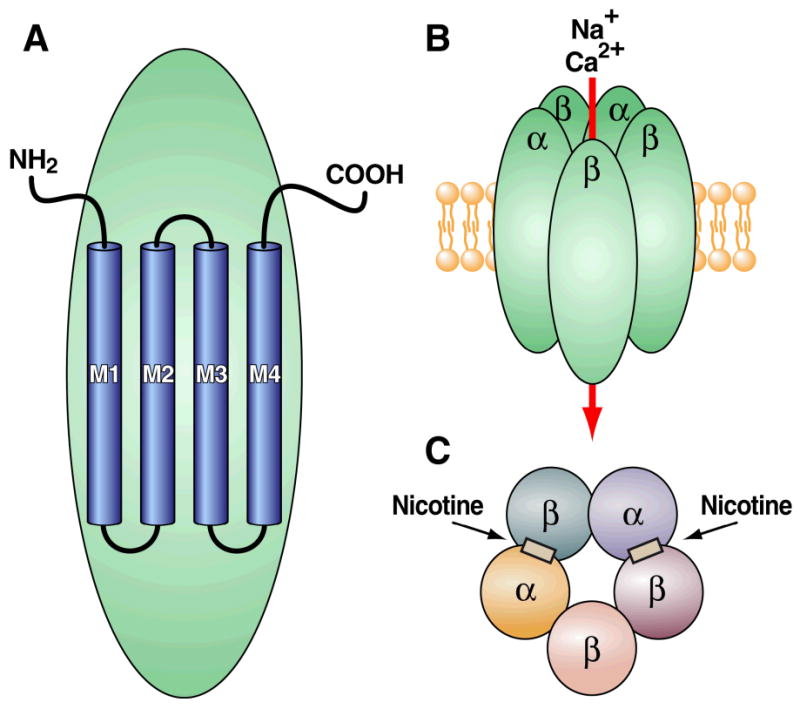

nAChRs are composed of five distinct membrane-spanning subunits (α and β subunits) that combine to form a functional receptor (Albuquerque et al., 1995; Lena and Changeux, 1998) (Fig. 1). Each subunit comprises four membrane-spanning helices (M1-M4 domains). These membrane-spanning domains are arranged in concentric layers around a central aqueous pore with the M2 domain lining the pore (Unwin, 1995; Grosman and Auerbach, 2000; Miyazawa et al., 2003; Taly et al., 2005; Unwin, 2005; Cymes and Grosman, 2008). Domains M1 and M3 shield M2 from the surrounding lipid bilayer, and M4 is the outermost and most lipid-exposed segment (Unwin, 1995; Grosman and Auerbach, 2000; Miyazawa et al., 2003; Taly et al., 2005; Unwin, 2005; Cymes and Grosman, 2008). Upon nAChR activation by an endogenous agonist (e.g., acetylcholine) or exogenous agonist (e.g., nicotine), the domains of each of the five nAChR subunits rearrange such that the central pore opens and permits cationic trafficking. The nAChR α subunit exists in nine isoforms (α2-α10), whereas the neuronal β subunit exists in three isoforms (β2-β4) (Chini et al., 1994; Elgoyhen et al., 2001; Le Novere et al., 2002; Lips et al., 2002). The receptor subunits arrange in various combinations to form functionally distinct pentameric nAChR subtypes, with α and β subunits combining with a putative stoichiometry of 2α:3β (Deneris et al., 1991; Sargent, 1993) (Fig. 1). However, α7, α8, and α9 subunits usually form homopentameric complexes composed of five α subunits and no β subunits, with only the α7 pentameric nAChR present in the central nervous system (CNS).

Figure 1.

Because of the large number of subunits, potentially many nAChR subtypes can exist, each composed of various combinations of α and β subunits. However, the assembly of nAChRs is a tightly regulated process that requires appropriate subunit interactions to produce functional nAChRs. As a result, the number of functional nAChR subtypes appears to be far less than that which could be generated theoretically (Table 2). As noted above, because of a lack of receptor agonists and antagonists with selectivity for individual nAChR subunits, the precise combinations of nAChR subunits that constitute functional neuronal nAChR subtypes in vivo are unknown. However, recent studies have begun to identify the nAChR subunits expressed by individual neurons in the brain. For example, single-cell reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) coupled with patch-clamp recordings suggests that approximately 90-100% of neurons located in the medial habenula (MH) express the α3, α4, α5, β2, and β4 nAChR subunits (Sheffield et al., 2000). In contrast, only about 40% of MH neurons express the α6, α7, and β3 subunits, whereas the α2 subunit was not found (Sheffield et al., 2000). Similar techniques revealed a significant co-expression of α3 and α5, α4 and β2, α4 and β3, α7 and β2, β2 and β3, and β3 and β4 within individual neurons in the rat hippocampus (Sudweeks and Yakel, 2000). Such investigations eventually may reveal the subunit composition of nAChR subtypes that are expressed by distinct cell populations.

Table 2.

Likely combinations of α and β subunits that produce functional neuronal nAChR subtypes in the central nervous system. Evidence for the existence of particular subunit combinations is summarized from electrophysiological and immunoprecipitation data obtained from oocyte and mammalian cell line expression systems.

| α Subunit | Combines with β subunits | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| α2 | β2 or β4 | (Duvoisin et al., 1989; Papke et al., 1989) |

| α3 | β2 or β4; β3 and 4 | (Duvoisin et al., 1989; Papke et al., 1989; Groot-Kormelink et al., 1998) |

| α4 | β2 or β4; β2 and β3 and β4 | (Duvoisin et al., 1989; Papke et al., 1989) |

| α6 | β2 or β4; β3 and β4 | (Gerzanich et al., 1997; Fucile et al., 1998; Kuryatov et al., 2000) |

| α7 | None (pentamer) | (Couturier et al., 1990) |

| α2 and α5 | β2 | (Balestra et al., 2000) |

| α3 and α5 | β2 or β4; β2and β4 | (Conroy and Berg, 1995; Wang et al., 1996) |

| α3 and α6 | β2 or β4; β3 and β4 | (Vailati et al., 1999; Kuryatov et al., 2000) |

| α4 and α5 | β2 | (Ramirez-Latorre et al., 1996) |

| α6 and α5 | β2 | (Kuryatov et al., 2000) |

| α4 and α6 and α5 | β2 | (Klink et al., 2001) |

In situ hybridization has been utilized to examine the distribution of messenger RNAs (mRNAs) for each nAChR subunit throughout the CNS of humans, non-human primates, rats, and mice (Table 3) (for review, see Drago et al., 2003). These experiments demonstrate marked differences in the distribution and density of the various subunits throughout the mammalian brain. Overall, α4, β2, and α7 subunits are the most widely expressed, whereas α2, α5, α6, β3, and β4 subunits demonstrate a more restricted expression profile (Table 2). In addition, although their relative densities may vary, considerable overlap exists in the expression profiles of the α4 and β2 subunits, suggesting that α4β2 nAChRs represent a major subtype of nAChR in the brain. Importantly, α2, α3, α4, α5, α6, α7, β2, and β3 subunits are expressed in brain regions that are known to play a role in the reinforcing effects of addictive drugs and in the cognitive and emotional deficits associated with various neuropsychiatric disorders. Indeed, these nAChR subunits are abundantly expressed in the amygdala, nucleus accumbens (NAc), ventral tegmental area (VTA), hippocampus, and throughout cortical areas (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of the brain regions that demonstrate a significant density of each nAChR subunit throughout the mammalian brain.

| Subunit | Brain region | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| α2 | interpeduncular nucleus hippocampus subiculum |

(Wada et al., 1989) |

| α3 | medial habenula entorhinal cortex thalamus hypothalamus ventral tegmental area |

(Wada et al., 1989; Champtiaux et al., 2002) |

| α4 | amygdala hippocampus hypothalamus medial habenula substantia nigra pars compacta |

(Wada et al., 1989) |

| α5 | interpeduncular nucleus ventral tegmental area substantia nigra pars compacta |

(Wada et al., 1990) |

| α6 | substantia nigra pars compacta ventral tegmental area locus coeruleus medial habenula interpeduncular nucleus |

(Le Novere et al., 1996) |

| α7 | amygdala hypothalamus hippocampus |

(Seguela et al., 1993) |

| α8 | not expressed in mammalian brain? | (Gotti et al., 1997) |

| α9 | not expressed in mammalian brain? | (Park et al., 1997) |

| α10 | not expressed in mammalian brain? | (Elgoyhen et al., 2001) |

| α2 | Thalamus substantia nigra pars compacta ventral tegmental area entorhinal cortex |

(Wada et al., 1989) |

| α3 | ventral tegmental area substantia nigra pars compacta thalamus medial habenula |

(Deneris et al., 1989) |

| α4 | interpeduncular nucleus medial habenula |

(Wada et al., 1989) |

Nicotinic receptors within the CNS are situated mainly on presynaptic terminals (Wonnacott, 1997) but also are found at somatodendritic, axonal, and postsynaptic locations (for review, see Sargent, 1993). One of the predominant roles of nAChRs in the CNS has been proposed to be the modulation of transmitter release as heteroreceptors (Wonnacott, 1997). Accordingly, nicotine has been shown to stimulate the release of most neurotransmitters in the brain, including dopamine, glutamate, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), norepinephrine, and serotonin (Carboni et al., 2000; Kenny et al., 2000b; Mansvelder and McGehee, 2000; Fu et al., 2003). Importantly, although not discussed in detail in the present review, the stimulatory action of nicotine on neurotransmitter release and on cell excitability is hypothesized to regulate many of the behavioral actions of nicotine in human tobacco smokers (for review, see Benowitz, 2008).

Neurobiological mechanisms of nicotine reinforcement

In order to identify the subunit composition of the nAChRs that regulate the reinforcing effects of nicotine, it is important to have an understanding of the neurobiological mechanisms by which nicotine acts in the brain to elicit its effects. Attention can thereby be focused on identifying those nAChRs located within reinforcement-related neural circuitries. It is important to note that dynamic rearrangement of the subunit content of constitutively expressed nAChRs in reinforcement circuitries may occur upon repeated exposure to rewarding doses of nicotine. Chronic exposure to nicotine in vitro robustly upregulates α4* and β2* nAChRs, whereas the α7, α3*, and β4* nAChRs are more resistant to upregulation (for review see Gentry and Lukas, 2002). Consistent with this in vitro observation, increased expression of α4β2* receptors is found in postmortem brain tissues of human smokers (Benwell et al., 1988; Breese et al., 1997). The α5 nAChR subunit appears to plays an important modulatory role within nAChRs. In Xenopus oocytes, inserting the α5 subunit into α4β2, α3β2 or α3β4 nAChRs increases receptor desensitization in response to nicotine (Wang et al., 1996; Ramirez-Latorre et al., 1996). Interestingly, the α3α5β2 subunit combination has increased affinity for nicotine compared with the α3β2 subtype (Wang et al., 1996), an alteration in vivo which could result in altered susceptibility to nicotine reward and vulnerability to tobacco addiction. Thus, nicotine-induced alterations in the expression of nAChR subunits may have a profound impact on the function of nAChRs in brain reward circuitries that may contribute to tobacco addiction. However, because current knowledge regarding nicotine-induced alterations in the subunit content of nAChRs in vivo is very limited, the contribution of this process to tobacco addiction is not reviewed in detail here.

Similar to other major drugs of abuse, nicotine enhances mesocorticolimbic dopamine transmission, and this action is hypothesized to play an important role in the positive reinforcing effects of nicotine (Merlo-Pich et al., 1997; Pidoplichko et al., 1997; Balfour et al., 2000; Koob and Le Moal, 2006). In vivo microdialysis studies have demonstrated that subcutaneous injections of nicotine (0.1 mg/kg) or cocaine (3 mg/kg) increases accumbal dopamine release by a similar magnitude (Zernig et al., 1997). The powerful impact of nicotine on the brain reward pathways is further evidenced by the significant lowering of intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS) thresholds (see below) observed in rats in response to intravenously self-administered nicotine. Indeed, although rats self-administer relatively low numbers of nicotine infusions compared with the amouts of cocaine consumed under similar conditions, rats nevertheless titrate their nicotine intake at a level that significantly lowers ICSS thresholds, with a magnitude of effect comparable with that induced by self-administered heroin or cocaine (Kenny et al., 2003; Kenny, 2006; Kenny and Markou, 2006; Kenny et al., 2006). Taken together, these observations suggest that nicotine can impact brain reward circuitries and facilitate their activity in a manner similar to other major drugs of abuse.

Whole-cell electrophysiological and in vivo microdialysis studies have demonstrated that systemic or direct VTA administration of nicotine increases the firing rate of mesoaccumbens dopamine neurons and increases dopamine release in the NAc (Andersson et al., 1981; Di Chiara and Imperato, 1988; Benwell and Balfour, 1992), particularly the shell region of the NAc (Pontieri et al., 1996), but also in other mesolimbic terminal regions, such as the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) (Carboni et al., 2000). Systemic nicotine-induced dopamine release in the NAc can be blocked by infusion of the nAChR antagonist mecamylamine into the VTA but not into the NAc; however, site-specific infusion of nicotine into the VTA or NAc can increase extracellular accumbal dopamine levels (Nisell et al., 1994). Thus, nicotine likely acts preferentially in the VTA to increase mesoaccumbens dopamine transmission but also may act directly in the striatum to modulate dopamine transmission. Furthermore, systemic administration of dopamine receptor antagonists (Corrigall and Coen, 1991) or lesions of the NAc (Corrigall et al., 1992) attenuate the reinforcing effects of nicotine, reflected in decreased intravenous nicotine self-administration in rats. Infusion of the nAChR antagonist dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE) directly into the VTA decreases nicotine self-administration in rats (Corrigall et al., 1994). Accumulating evidence suggests that, in addition to the direct stimulatory action of nicotine at postsynaptic nAChRs located on dopamine-containing VTA neurons, nicotine may increase mesoaccumbens dopamine transmission by indirect actions involving glutamate and GABA transmission in the VTA. Indeed, nicotine activates nAChRs located on VTA glutamate terminals (Grillner and Svensson, 2000; Mansvelder and McGehee, 2000; Jones and Wonnacott, 2004), and thereby induces a persistent increase in glutamate transmission in this brain site (Fu et al., 2000; Grillner and Svensson, 2000; Schilstrom et al., 2000). In turn, this enhanced glutamate transmission stimulates postsynaptic glutamate receptors located on dopamine-containing neurons, thereby increasing their burst firing (Kalivas, 1993; Hu and White, 1996; Schilstrom et al., 1998; Fu et al., 2000; Mansvelder and McGehee, 2000; Kosowski et al., 2004). In addition, nicotine activates nAChRs located on GABAergic neurons in the VTA (Mansvelder et al., 2002), resulting in a transient increase in inhibitory GABAergic transmission. However, nAChRs located on GABAergic neurons in the VTA appear to be very sensitive to nicotine-induced desensitization, and following nicotine-induced activation may become nonfunctional for prolonged periods of time (Mansvelder et al., 2002). Additionally, nAChRs located presynaptically on cholinergic fibers into the VTA also may regulate mesoaccumbens dopamine transmission (Maskos, 2008). Identification of the subunit composition of nAChRs in the VTA, especially those located on dopamine-, glutamate-, and GABA-containing neurons but also located on cholinergic neurons, is likely to provide important insights to the identity of the nAChR subtypes that regulate nicotine reinforcement. Similarly, identification of the nAChR subunits expressed in terminals brain regions of VTA dopamine neurons, such as the NAc, also may provide important clues to the nAChR subtypes that regulate nicotine reinforcement. The data outlined below describe recent advances in our understanding of the nAChR subunits that are expressed in the VTA and NAc and highlight the utility of nAChR genetically modified mice in this regard. Importantly, although not reviewed in detail here, nicotine exerts actions in reward-relevant brain regions other than the VTA and NAc, and extra-mesolimbic nAChRs also play a central role in nicotine reinforcement (Kenny et al., 2008).

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits that regulate the positive reinforcing effects of nicotine: In vitro evidence

Based on accumulating evidence that the VTA is a core brain site regulating behavioral actions of nicotine with relevance to addiction, much effort has been directed toward elucidating the nicotinic subunits expressed in this site. Charpantier and colleagues (1998) used RT-PCR to analyze mRNA content of individual nAChR subunits in the VTA following unilateral lesions of the mesoaccumbens system in rats. In contrast to the unlesioned side, mRNA signals for α2, α3, α5, α6, α7, and β4 subunits were absent in the VTA of the lesioned hemisphere (Charpantier et al., 1998). These nAChR subunits, therefore, may be expressed preferentially in dopamine-containing neurons that originate in the VTA. Interestingly, mRNA for α4, β2, and β3 subunits was detected after the dopamine lesion (Charpantier et al., 1998), suggesting that these subunits may be expressed in both dopamine-containing, as well as GABAergic, neurons in the VTA. Klink and colleagues (2001) utilized RT-PCR and single-cell electrophysiological recordings in wildtype and nAChR knockout mice to investigate subunit composition of nAChR subtypes expressed in the VTA. Almost 100% of cells in the VTA (i.e., dopamine- and GABA-containing) expressed mRNA for the α4 and β2 subunit (Klink et al., 2001), suggesting that these subunits may be incorporated into many nAChR subtypes in this area. Approximately 90% of dopamine-containing cells and 20% of GABA-containing cells in the VTA contained β3 nAChR subunits (Klink et al., 2001). Similarly, approximately 70% of dopamine-containing neurons in the VTA expressed α5 nAChR mRNA, with a much lower proportion of GABAergic cells (<20%) expressing this subunit (Klink et al., 2001). Approximately 75% of dopamine-containing cells in the VTA expressed α6 nAChR subunits, compared with about 10% of GABAergic cells. Around 40% of both dopamine and GABAergic cells expressed mRNA for the α7 nAChR subunit (Klink et al., 2001). A relatively low concentration of β4 mRNA was observed in VTA cells, consistent with the high concentrations of this subunit that are restricted to the MH and IPN. Therefore, the majority of dopamine neurons in the VTA expressed α4, α5, α6, β2, and β3 mRNA, whereas the majority of GABA neurons expressed α4 and β2 subunits, with α7 subunits demonstrating a similar incidence in both cell types. Interestingly, in the VTA, electrophysiological analyses suggested that the only currents elicited by acetylcholine in β2 knockout mice were regulated by α7 pentameric nAChRs subunit (Klink et al., 2001). In α4 knockout mice, acetylcholine-evoked currents were qualitatively similar but quantitatively smaller than those observed in wildtype mice (Klink et al., 2001). Finally, in α7 knockout mice, acetylcholine-evoked currents were qualitatively and quantitatively similar to those observed in wildtype mice, with the exception that putative α7-mediated currents were absent. Based on the above, three subtypes of pentameric nAChRs were proposed to be putatively functional on VTA dopamine-containing neurons: α4α6α5(β2)2, (α4)2α5(β2)2, and (α7)5. On VTA GABAergic neurons, two nAChR subtypes predominated: (α4)3(β4)2 and (α7)5.

Interestingly, although mRNA for the β3 nAChR is abundant in the VTA, this subunit does not appear to contribute to functional nAChRs in this brain site. Instead, the β3 subunit may be targeted to terminal domains in the NAc where it contributes to the stimulatory effects of nicotine on accumbal dopamine transmission. Immunocytochemical analyses demonstrated that β3 subunits are transported to the projection areas of VTA neurons (Forsayeth and Kobrin, 1997) and that the striatum has high β3 protein concentrations (Forsayeth and Kobrin, 1997; Reuben et al., 2000). Using experimental approaches similar to those described above, much progress has been made in elucidating putative nAChR subtypes in the striatum that regulate the stimulatory effects of nicotine on dopamine transmission in this brain region. This work has been facilitated by combining data generated from nAChR mutant mice with classical pharmacological approaches. In particular, the discovery that the novel nAChR antagonist α-conotoxin MII (α-CtxMII) can attenuate, but not fully block, the stimulatory effects of nicotine on striatal dopamine release suggested that at least two sub-populations of nAChRs regulate the actions of nicotine, a finding that has proven to be very useful in characterizing putative nAChR subtypes in the striatum. Zoli and colleagues (2002) used α-CtxMII combined with immunoprecipitation and targeted brain lesion to provide evidence that four species of nAChRs may be expressed on the terminals of mesoaccumbens dopamine neurons in the striatum that contain the following subunits: α4β2*, α4α5β2*, α4α6β2β3*, or α6β2β3* (Zoli et al., 2002). Interestingly, by using α-CtxMII and various nAChR ligands in combination with nAChR knockout mice, Salminen and colleagues similarly concluded that α4β2*, α4α5β2*, α4α6β2β3*, and α6β2β3* nAChRs may be located on dopamine terminals in the striatum, where they can regulate the stimulatory effects of nicotine on mesoaccumbens dopamine transmission (Salminen et al., 2004). In addition, two further putative nAChR subtypes were identified in these studies: α6β2β3* and α6β2* (for recent review, see Grady et al., 2007). The effects of acetylcholine-evoked dopamine release from striatal synaptosomes and nicotine-evoked striatal dopamine release measured by in vivo microdialysis have been assessed in α4, α6, α4α6, and β2 knockout mice (Champtiaux et al., 2003). α4β2*, α6β2*, and α4α6β2* nAChRs were shown to be expressed on dopamine terminal fields in the striatum. Additionally, α6β2* nAChRs were found to be functional and sensitive to α-CtxMII inhibition but do not contribute to dopamine release evoked by systemic nicotine administration, and somatodendritic (non-α6)α4β2* nAChRs were posited to be the most likely contribution to nicotine reinforcement (Champtiaux et al., 2003). Taken together, the above data suggest that α4, α5, α6, β2, and β3 may be important components of functionally expressed nAChR subtypes in the VTA and striatum. These nAChR subunits likely play an important role in regulating nicotine reinforcement processes.

Electrophysiological investigations also have provided important insights into the nAChR subtypes likely to be expressed in the VTA and striatum that may regulate nicotine reinforcement. Initially, Picciotto and colleagues (1998) found that nicotine increased the discharge frequency of mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons from wildtype but not β2 knockout mice. Mameli-Engvall and colleagues (2006) extended these findings specifically within VTA dopamine-containing neurons; basal levels of firing were decreased and burst firing was absent in VTA dopaminergic neurons from β2 knockout mice. Furthermore, the stimulatory effect of intravenous nicotine on VTA dopamine cells was abolished in β2 knockout mice (Mameli-Engvall et al., 2006). The role of β2* nAChRs in regulating the effects of endogenous cholinergic transmission on dopamine release from mouse striatal slices also has been assessed (Zhou et al., 2001). β2 knockout mice were shown to have reduced levels of electrically evoked dopamine release compared with wildtype controls (Zhou et al., 2001). These electrophysiological data from nAChR knockout mice support the hypothesis that β2* nAChRs play an important role in regulating the effects of nicotine on the neuroanatomical substrates that are implicated in nicotine reinforcement.

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits that regulate the positive reinforcing effects of nicotine: In vivo evidence

In addition to the in vitro approaches described above, in vivo studies are beginning to shed more direct light on nAChR subunits involved in nicotine reinforcement and dependence processes. Many of the published studies assessing the role of nAChR subtypes in nicotine reinforcement have utilized the intravenous nicotine self-administration procedure. This procedure is considered the most direct and reliable measure of the reinforcing properties of drugs of abuse. Indeed, the majority of drugs that are abused by humans are also self-administered by animals (Weeks, 1962; Wilson and Schuster, 1972; Risner and Jones, 1975; Griffiths and Balster, 1979; Griffiths et al., 1981; Criswell and Ridings, 1983; Donny et al., 1995). Consistent with a role for nicotine in initiating and maintaining the tobacco smoking habit in humans, nicotine acts as a reinforcer and is self-administered by humans (Harvey et al., 2004), non-human primates (Goldberg et al., 1981), dogs (Risner and Goldberg, 1983) and rats (Corrigall and Coen, 1989; Watkins et al., 1999). Nicotine self-administration produces an inverted U-shaped dose-response curve in all cases, similar to that obtained for other reinforcing drugs such as opiates and cocaine. It is likely that the shape of the nicotine dose-response curve is the result of the competing positive and negative effects of nicotine at different doses. Thus, the increased responding for nicotine over the ascending limb of the curve may reflect the increasing reinforcing effects of nicotine as the unit dose per infusion increases. In contrast, the decreased responding over the descending limb of the curve may reflect increasing aversive properties of nicotine. Consistent with the hypothesis that nicotine may elicit both positive and negative effects, doses of nicotine self-administered by non-human primates can also serve as the substrate for negative reinforcement to occur, and monkeys will work to avoid such IV nicotine infusions (Spealman and Goldberg, 1982). Further, anxiety-like behavior was increased in rats following volitional intravenous self-administration of nicotine (Irvine et al., 2001a), and benzodiazepine treatment, which counters the aversive properties of nicotine, increased nicotine self-administration in rats (Hanson et al., 1979). Finally, it is important to note that the nicotine dose-response curve is ‘shallow’ and ‘narrow’ compared with that obtained for opiates or cocaine, suggesting that responding for nicotine is relatively insensitive to alterations in the dose available for infusion, and that nicotine is reinforcing over a narrow range of doses only.

Consistent with a role for neuronal nAChRs in regulating nicotine reinforcement, administration of antagonists at neuronal nAChRs decreases nicotine self-administration in non-human primates and rats (see below). This decrease in nicotine intake is in contrast to human tobacco smokers, in which there was a transient increase in smoking behavior (Stolerman et al., 1979) or intravenous nicotine self-administration (Rose et al., 1989), after antagonist blockade of nAChRs. This finding in rats is also in contrast to findings with other drugs of abuse such as opiates or cocaine, where administration of opioid or dopamine receptor antagonists increased opiate or cocaine intake, respectively. Such compensatory increases in drug intake likely occur to counter antagonist-induced reductions in the reward value of unit injections of drugs of abuse. Thus, the net effect of antagonist treatment is usually a right-ward shift in the dose-response curve. One possible explanation for the absence of such antagonist-induced compensatory increases in nicotine intake in laboratory animals may be that different subtypes of nAChRs regulate nicotine's reinforcing properties and its aversive properties, and nAChR antagonists in these animals may selectively block the reinforcing effects of nicotine but not its aversive effects. Such an action of nAChR antagonists would prevent laboratory animals from self-administering compensatory nicotine injections. Whatever the explanation, the net effect of decreasing the reinforcing properties of nicotine in rodents appears to be a shift the nicotine self-administration dose-response curve down-ward instead of right-ward, resulting in an overall decrease in responding for nicotine at each unit dose of nicotine available. Thus, pharmacological or genetic manipulations that decrease nicotine reinforcement may be expected to result in a decrease in responsing for nicotine self-administration.

Systemic or intra-VTA administration of the neuronal nAChR antagonist DHβE decreases nicotine self-administration in rats (Corrigall and Coen, 1989; Watkins et al., 1999). In addition, DHβE reduces the stimulatory effects of nicotine on brain reward systems, demonstrated by attenuated nicotine-induced lowering of ICSS thresholds in rats (Ivanova and Greenshaw, 1997; Harrison et al., 2002). DHβE is relatively selective for α4* and β2* nAChRs compared with other classes of nAChRs (Harvey and Luetje, 1996; Harvey et al., 1996). The novel nAChR ligand SSR591813, considered a partial agonist at nAChRs containing α4 and β2 subunits, decreases nicotine self-administration in rats (Cohen et al., 2003). Similarly, the novel nAChR ligand UCI-30002, a partial agonist at α4β2* nAChRs (but also with actions at α7 and α3β4-containing nAChRs), also decreases nicotine self-administration in rats (Yoshimura et al., 2007). Varenicline, a partial agonist at α4β2* nAChRs (but a full agonist at α7* nAChRs) (Mihalak et al., 2006), dose-dependently decreases nicotine self-administration in rats (Rollema et al., 2007). Liu and colleagues have shown that 5-iodo-A-85380, a putative agonist at β2* nAChRs, is actively self-administered by rats (Liu et al., 2003). Full dose-response analyses of these novel drugs should be determined in further studies. Nevertheless, these pharmacological data suggest that α4* and β2* nAChRs play an important role in nicotine reinforcement.

Recent observations in nAChR mutant mice also support the role of these receptor subunits in nicotine addiction. To date, the reinforcing effects of intravenously self-administered nicotine have been assessed only in β2 knockout mice (Picciotto et al., 1998; Epping-Jordan et al., 1999). In these studies, β2 knockout mice and their wildtype counterparts were trained to nose-poke for cocaine under a fixed-ratio 2, time-out 20 s schedule of reinforcement, in which two nose-pokes into an “active” nose-poke hole resulted in an intravenous infusion of cocaine (0.8 mg/kg/infusion) (Picciotto et al., 1998). Under this schedule of reinforcement, β2 knockout and wildtype mice demonstrated similar responding for cocaine (Picciotto et al., 1998; Epping-Jordan et al., 1999). However, when cocaine was substituted with nicotine infusions (0.03 mg/kg/infusion), wildtype mice persisted in responding for nicotine, whereas β2 knockout mice rapidly extinguished operant responding in a manner similar to that observed in wildtype mice when cocaine was substituted with saline (Picciotto et al., 1998; Epping-Jordan et al., 1999). Most recently, Maskos and colleagues (2005) utilized lentivirus-mediated gene transfer to re-express β2 nAChR subunits in the VTA of β2 knockout mice. In these “rescued” β2 knockout mice, systemic nicotine administration significantly increased dopamine transmission in the NAc similar to wildtype mice, an effect absent in non-rescued β2 knockout mice (Maskos et al., 2005). Moreover, wildtype and rescued β2 knockout mice demonstrated preference for the arm of a Y-maze paired with the delivery of intra-VTA nicotine infusions upon arm entry. In contrast, non-rescued β2 knockout mice did not display preference for either the nicotine-paired or non-paired arm of the Y-maze (Maskos et al., 2005). Additionally, Walters and colleagues (2006) found that β2 knockout mice do not demonstrate a conditioned place preference for an environment previously paired with nicotine injections. Furthermore, using β2 knockout mice, Shoaib and colleagues (2002) showed that β2* nAChRs regulate the discriminative stimulus properties of nicotine. The above observations suggest that β2 nAChR subunits play a central role in nicotine reinforcement, consistent with the high density of these subunits in the VTA and other reward-relevant brain regions.

In addition to gene knockout technology, Tapper and colleagues (2004) utilized a complementary approach to investigate the role of α4 nAChR subunits in regulating the reinforcing effects of nicotine. Specifically, an endogenous exon of the α4 nAChR gene was replaced in mice with one containing a single point mutation (Leu 9′ П Ala 9′). This point mutation renders mutant “knock-in” α4-containing receptors hypersensitive to nicotine. Using these α4 knock-in mice, nicotine was shown to induce a significant conditioned place preference, a measure of the conditioned rewarding effects of drugs of abuse, at doses 50-fold lower than those necessary to induce a place preference in wildtype mice (Tapper et al., 2004). These data suggest that, similar to β2 nAChR subunits, α4 subunits also likely are important regulators of nicotine reinforcement processes. Importantly, however, the role of α4 subunits in nicotine reinforcement has not yet been directly tested by intravenous nicotine self-administration behavior in α4 nAChR knockout mice.

In contrast to most other nAChR subunits expressed in the CNS, the α5 nAChR subunit does not form functional receptors when expressed alone or when co-expressed with β subunits in Xenopus oocytes (Ramirez-Latorre et al., 1996; Yu and Role, 1998). Rather, the function of the α5 nAChR subunit is restricted to a modulatory role when incorporated into functional nAChRs, regulating the activation and desensitization kinetics and other characteristics of nAChRs (Girod et al., 1999; Nelson and Lindstrom, 1999). Unfortunately, compounds selective for α5* nAChRs are not available. Therefore, in vivo pharmacological data supporting a role for α5 subunits in nicotine self-administration has not been generated. Nevertheless, accumulating circumstantial evidence suggests that α5* nAChRs may play a key role in nicotine reward and dependence processes. As stated above, the α5 nAChR subunit is expressed at high concentrations in the VTA (Klink et al., 2001), an important neuroanatomical substrate that regulates nicotine reward. Indeed, the α5 subunit is considered an important component of two putative functional nAChR subtypes expressed on VTA dopamine neurons (Klink et al., 2001): α4α6α5(β2)2 and (α4)2α5(β2)2. Furthermore, α5 knockout mice have decreased behavioral sensitivity to the effects of nicotine, measured by nicotine-induced seizures and hypolocomotion (Salas et al., 2003a). The most convincing evidence supporting a role for α5* nAChRs in nicotine dependence has been generated from genetic analyses of human smokers. A non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the α5 nAChR gene was associated with a two-fold increase in the risk of developing nicotine dependence in humans after they were exposed to cigarette smoking (Saccone et al., 2007). Similarly, Schlaepfer and colleagues (2007) found that two linked SNPs on the gene cluster that incorporates the α3, α5, and β4 nAChR subunits predicted early-onset tobacco use in young adults. Berrettini and colleagues (2008) showed in three independent populations of human samples, totaling approximately 15000 individuals, that a common genetic haplotype in the α3/α5/β4 gene cluster predisposes individuals to nicotine dependence. Recently, polymorphism in the α3/α5/β4 gene cluster, most notably in the α5 nAChR subunit gene, predisposed smokers to increased risk of developing lung cancer (Hung et al., 2008), perhaps by increasing the reinforcing effects of tobacco smoke, resulting in greater tobacco intake and associated carcinogens, and increased risk of developing cancer (Thorgeirsson et al., 2008). Interestingly, polymorphism in the α5 nAChR subunit gene was found to be protective against cocaine dependence (Grucza et al., 2008), a finding suggesting that nicotine and cocaine reinforcement may be dissociated at the level of α5* nAChRs. Taken together, these data suggest that the α5 nAChR subunit likely plays a critical role in nicotine dependence processes. Nevertheless, direct assessment of the reinforcing effects of nicotine in α5 knockout mice will be necessary to support this conclusion.

Much interest has centered on the potential role of α6 nAChR subunits in regulating nicotine reinforcement processes. This interest has arisen, in large part, because of the high concentrations and relatively restricted patterns of expression of mRNA transcripts for α6 subunits in the VTA (Quik et al., 2000; Azam et al., 2002; Champtiaux et al., 2002). The expression of α6 nAChR subunits was shown to undergo robust upregulation in rats following repeated exposure to intravenous nicotine self-administration (Parker et al., 2004). More recently, pharmacological data have emerged that further support a role for this subunit in nicotine reinforcement. Neugebauer and colleagues demonstrated that the novel nAChR antagonist bPiDDB, which may selectively antagonize α6* and/or α3* nAChRs (Dwoskin et al., 2004; Neugebauer et al., 2006), dose-dependently decreases nicotine self-administration in rats and the hyperactivity induced by acute and repeated nicotine administration (Neugebauer et al., 2006). Furthermore, Le Novere and colleagues (1999) demonstrated that knockdown of α6 mRNA through the use of antisense oligonucleotides attenuates the locomotor stimulatory effects of nicotine in mice. These data provide circumstantial evidence implicating α6-containing nAChRs in nicotine reinforcement processes, but the role for this subunit has not yet been directly tested.

The nAChR antagonist methyllycaconitine (MLA) is considered relatively selective for α7 pentameric nAChRs (Ward et al., 1990), and a high concentration of α7 nAChRs exists in the VTA and other reward-related brain sites, including the amygdala (Seguela et al., 1993). MLA was shown to attenuate the conditioned rewarding effects of nicotine following direct intra-VTA administration in rats (Laviolette and van der Kooy, 2003). Furthermore, intra-VTA administration of MLA attenuated the ICSS threshold-lowering effects of nicotine in rats (Panagis et al., 2000). More importantly, Markou and Paterson (2001) demonstrated that MLA decreased intravenous nicotine self-administration in rats. These observations suggest that α7 nAChRs play a role in nicotine reinforcement. In contrast, Grottick and co-workers (2000) demonstrated that MLA did not alter nicotine self-administration or nicotine-stimulated locomotor activity in rats. Based on these findings, α7 nAChRs were speculated to play no role in regulating nicotine reinforcement (Grottick et al., 2000). Consistent with this conclusion, nicotine was shown to elicit a conditioned place preference in α7 mice that was very similar to that observed in wildtype mice (Walters et al., 2006). Thus, the precise role of α7 nAChRs in nicotine reinforcement remains unclear, and testing of α7 knockout mice in the intravenous nicotine self-administration procedure may provide important insights into the role of this receptor subunit in nicotine reinforcement. Overall, the above data support a role for α4 and β2, and perhaps α5, α6, and α7, nAChR subunits in regulating the positive reinforcing effects of nicotine. In addition, these data demonstrate the utility of nAChR knockout mice for investigating the nAChR subtypes that regulate nicotine reinforcement.

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits regulate the positive reinforcing effects of other drugs of abuse

Accumulating evidence suggests that nAChRs may play a role in the reinforcing effects of drugs of abuse other than nicotine, such as cocaine and alcohol. Cue-induced cocaine craving is potentiated by nicotine pretreatment in human cocaine users whom are also cigarette smokers (Reid et al., 1998). In rats, the development of escalated levels of cocaine intake that is associated with extended daily access to the drug was abolished by co-administration of the nAChR antagonist mecamylamine (Hansen and Mark, 2007). This observation suggests that nAChRs may regulate the development of compulsive cocaine-seeking. Perfusion of mecamylamine or co-perfusion of the nAChR antagonists DHβE and MLA (see above) into the NAc blocked the stimulatory effects of cocaine on NAc dopamine release (Zanetti et al., 2007). More importantly, β2 knockout mice appear to be less sensitive to the conditioned rewarding effects of cocaine (Zachariou et al., 2001). Furthermore, induction of chronic Fos-related antigens by cocaine, which may contribute to cocaine-associated neuroplasticity, was abolished in β2 knockout mice compared with wildtype siblings, implying that the actions of cocaine downstream of membrane-expressed receptors may be regulated by β2* nAChRs (Zachariou et al., 2001).

In addition to cocaine, nAChRs play a role in alcohol dependence. In human populations, polymorphisms in the α3/α5/β4 nAChR gene cluster were associated with increased vulnerability to alcoholism (Schlaepfer et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2008), as well as with altered steady-state levels of α5 nAChR mRNA in the brain (Wang et al., 2008). Mecamylamine decreased the desire to consume alcohol in humans (Young et al., 2005) and blocked the self-reported euphoric effects of alcohol (Chi and de Wit, 2003). In rats, mecamylamine decreased ethanol intake (Blomqvist et al., 1996; Ericson et al., 1998; Le et al., 2000) and attenuated the stimulatory effects of ethanol on dopamine release in the NAc when administered either systemically (Blomqvist et al., 1993) or directly into the anterior, but not posterior, VTA (Ericson et al., 2008). Systemic or direct intra-NAc administration of mecamylamine decreased ethanol consumption by rats (Nadal et al., 1998; Le et al., 2000). Similarly, the α4β2* nAChR partial agonist varenicline was shown recently to decrease ethanol consumption by rats (Steensland et al., 2007). Interestingly, chronic ethanol consumption decreased the expression of α7 and α4β2* nAChRs in the hippocampus (Robles and Sabria, 2008). Patch-clamp recordings from human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells that heterologously express human nAChR subunits have shown that ethanol can act directly at nAChRs to potentiate the activity α4* nAChRs (Zuo et al., 2001; Zuo et al., 2002). These data suggest that nAChRs play a role in the neurochemical actions of alcohol that participate in the regulation of alcohol intake. Interestingly, α7 knockout mice are more sensitive than wildtype mice to some of the behavioral actions of ethanol (Bowers et al., 2005), including ethanol-induced locomotor stimulation and loss of righting reflex (Bowers et al., 2005). However, little is known about the reinforcing effects of alcohol in α7* knockout and other strains of nAChR knockout mice. Taken together, the above data support an important role for nAChRs, particularly those containing β2 subunits but perhaps also α5* and α7* subunits, in the reinforcing actions of cocaine and alcohol, as well as in the neuroplasticity induced by these drugs that may contribute to compulsive drug-seeking.

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits in nicotine dependence and withdrawal

Addiction to tobacco smoking depends not only on the positive reinforcing and hedonic actions of nicotine, but also on escape from the aversive consequences of nicotine withdrawal (Doherty et al., 1995; Kenny and Markou, 2001). Indeed, prolonged nicotine exposure results in the development of nicotine dependence, and smoking cessation commonly elicits an aversive nicotine withdrawal syndrome in human smokers (Shiffman and Jarvik, 1976; Hughes et al., 1991). This syndrome can be directly attributed to a reduction of nicotine intake in nicotine-dependent individuals (West et al., 1984). Importantly, withdrawal duration and severity can predict relapse in abstinent human smokers (Piasecki et al., 1998; Piasecki et al., 2000; Piasecki et al., 2003). Furthermore, the efficacy of nicotine replacement therapy, at least in certain individuals (Fagerstrom, 1988; Sachs and Leischow, 1991), is related to its ability to prevent the onset and reduce the duration of nicotine withdrawal.

Isola and colleagues have shown that spontaneous or mecamylamine-precipitated withdrawal from chronic nicotine injections (2 mg/kg salt, four times daily for 14 days) resulted in increased expression of physical or “somatic” withdrawal signs (e.g., rearing, jumping, shakes, abdominal constrictions, chewing, scratching, facial tremor) in mice (Isola et al., 1999). Similarly, spontaneous or antagonist-precipitated withdrawal from nicotine delivered via osmotic minipump (24-48 mg/kg/day free-base, 7-60 day continuous treatment) also increased somatic withdrawal signs, and these signs were increased by a greater magnitude in C57BL/6 than in 129/SvEv strains of mice (Damaj et al., 2003). This strain difference is important to note because most nAChR knockout mice are bred on a C57BL/6 background. Besson and colleagues have shown that somatic withdrawal signs were increased by a similar magnitude in wildtype and β2 knockout mice during mecamylamine-precipitated withdrawal from nicotine delivered via osmotic minipump (2.4 mg/kg/day free-base, 28 day continuous treatment) (Besson et al., 2006). The α7-selective nAChR antagonist MLA increased somatic withdrawal signs in wildtype and β2 knockout mice following chronic nicotine treatment (24-36 mg/kg/day free-base via osmotic minipump, 13-28 day continuous treatment) (Salas et al., 2004; Jackson et al., 2008). However, under similar treatment conditions, somatic withdrawal signs were diminished in α5, α7, and β4 knockout mice (Salas et al., 2004; Salas et al., 2007; Jackson et al., 2008). Based on these observations, α5, α7, and β4, but not β2, subunits likely are components of the nAChRs that regulate the development of physical dependence on nicotine and the expression of somatic withdrawal signs.

Affective components of nicotine and tobacco withdrawal include depressed mood, dysphoria, anxiety, irritability, difficulty concentrating, and craving (Parrott, 1993; Doherty et al., 1995; Kenny and Markou, 2001). Accumulating evidence suggests that affective components of withdrawal may play a more important role than somatic aspects in the maintenance of dependence to drugs of abuse, including nicotine (Markou et al., 1998; Kenny and Markou, 2001; George et al., 2007). In mice, withdrawal from nicotine delivered via osmotic minipump (Damaj et al., 2003; Jonkman et al., 2005) or repeated daily injections (Costall et al., 1989) increased the expression of anxiety-like behaviors in mice. Similarly, the time spent immobile in the forced swim test, considered an index of depression-like behavior, was increased in mice undergoing withdrawal from nicotine (2 mg/kg, four injections daily for 15 days) compared with saline-treated controls (Mannucci et al., 2006). Recent findings in nAChR knockout mice have provided insights into the nAChR subunits that may regulate affective aspects of nicotine withdrawal. Affective signs of spontaneous or mecamylamine-precipitated nicotine withdrawal (36 mg/kg/day via osmotic minipump for 14 or 28 days), reflected in increased anxiety-related behavior and induction of a conditioned place aversion, were absent in β2 knockout mice but were readily observed in α5 knockout and α7 knockout mice (Jackson et al., 2008). Furthermore, the deficits in fear conditioning typically observed in mice undergoing withdrawal from nicotine (6.3 mg/kg/day free-base via osmotic minipump, 12 day treatment) were intact in α7 knockout mice but were greatly diminished in β2 knockout mice (Portugal et al., 2008). Therefore, β2*, but not α5* or α7*, nAChRs may contribute to the affective components of the nicotine withdrawal syndrome.

Withdrawal from nicotine and other major drugs of abuse decreases brain reward function, reflected in elevated ICSS thresholds in rats (Epping-Jordan et al., 1998; Watkins et al., 2000; Kenny and Markou, 2005). Such reward deficits are considered a particularly important affective component of withdrawal that maintains drug-taking behavior (Koob and Le Moal, 2005; Kenny, 2006). Systemic administration of the nAChR antagonist DHβE, but not MLA, precipitated withdrawal-associated elevations of ICSS thresholds in nicotine-dependent rats (3.16 mg/kg/day for 7-14 days) (Ivanova and Greenshaw, 1997; Markou and Paterson, 2001; Harrison et al., 2002). Infusion of DHβE into the VTA also precipitated elevations of ICSS thresholds in nicotine-dependent, but not control, rats (Bruijnzeel and Markou, 2004). As stated above, DHβE is relatively selective for α4* and β2* nAChRs (Harvey and Luetje, 1996; Harvey et al., 1996). Therefore, these data provide pharmacological support for a role of α4* and β2* nAChR subtypes, particularly those located in the VTA, in regulating the development of nicotine dependence and the expression of nicotine withdrawal. Nevertheless, the role of these or other nAChR subunits in regulating the reward deficits associated with nicotine withdrawal has not been directly tested in nAChR knockout mice. However, recent data from our laboratory has shown that nicotine withdrawal does indeed elevate ICSS thresholds in mice similar to rats (Johnson et al., 2008), highlighting the potential utility of the ICSS procedure for assessing nicotine withdrawal-associated reward deficits in nAChR knockout mouse strains (Johnson et al., 2008).

Finally, in a series of interesting studies, Nashmi and colleagues (2007) generated genetically modified mice in which the α4 nAChR subunit was altered to express a fluorescent tag (yellow fluorescent protein [YFP]), and these mice were used to assess the effects of chronic nicotine administration on the expression of α4* nAChRs in cell populations located in the VTA (Nashmi et al., 2007). The α4*-YFP mice were treated continuously for 10 days with nicotine (48 mg/kg/day) via osmotic minipump. Levels of α4-YFP in VTA dopamine-containing cells were not significantly altered by chronic nicotine exposure. In contrast, α4-YFP levels were dramatically increased in GABAergic cells in the VTA. A similar increase in α4-YFP expression in VTA GABAergic cells also was observed in mice chronically treated with a lower dose of nicotine (9.6 mg/kg/day). These data demonstrate that VTA cell populations are differentially sensitive to nicotine-induced plasticity in α4* nAChR expression and suggest that α4* nAChRs located in VTA GABAergic cells may be a particularly important target for the induction of nicotine dependence (Nashmi et al., 2007).

Anxiety disorders and subtypes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors

Anxiety may be defined as an emotional condition characterized by an unpleasant and diffuse sense of apprehension usually accompanied by autonomic symptoms such as headache or palpitations (Millet et al., 1998). Anxiety is distinguished from fear by the fact that in anxiety a threat generated “internally” results in an emotional response, whereas in the case of fear, the threat is external and known. In humans, anxiety disorders encompass a number of related conditions, including generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder, phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Many pharmacological agents used to treat anxiety disorders, including fluoxetine (Prozac) or buspirone (Buspar), have direct actions on nAChRs (Dilsaver and Davidson, 1987; Fryer and Lukas, 1999; Hennings et al., 1999; Lopez-Valdes and Garcia-Colunga, 2001; Miller et al., 2002; Garwood and Potts, 2007), suggesting a role of nAChR modulation in the therapeutic actions of these compounds. A high prevalence of tobacco addiction exists among individuals who suffer from anxiety disorders (Koenen et al., 2006; Morissette et al., 2007; Goodwin et al., 2008). Indeed, Hughes and colleagues reported that the incidence of smoking was approximately 47% in patients suffering from an anxiety disorder compared with 30% in control patients (Hughes et al., 1986). However, patients suffering from OCD may have reduced rates of tobacco dependence compared with the general population (Bejerot and Humble, 1999; Lopes et al., 2002). Many smokers report that cigarettes have an anxiety-reducing influence (Speilberger, 1986) and that mood control is a core reason for maintaining their smoking habit (Parrott, 1994). Conversely, smoking abstinence and associated nicotine withdrawal is known to increase subjective levels of anxiety in smokers (Hughes et al., 1991). Thus, nicotine in tobacco smoke appears to have subjective anxiolytic effects that are important in maintaining the tobacco habit and may be particularly important in individuals with comorbid anxiety disorders. Nevertheless, the precise relationship between nicotine consumption and anxiety state is unclear. Although accumulating evidence suggests that nicotine in tobacco smoke may have subjective anxiety-reducing properties, nicotine itself actually may contribute to the development of anxiety disorders (West and Hajek, 1997; Isensee et al., 2003). Taken together, the above observations are consistent with the notion that deficits may exist in nAChR signaling pathways in the brains of smokers who suffer from comorbid anxiety disorders, and these deficits may enhance the reinforcing effects of nicotine and result in higher rates of tobacco dependence in such individuals.

In rodents, acute administration of nicotine or nAChR agonists has complex actions on anxiety-related behaviors (Brioni et al., 1993; Kenny et al., 2000a). Nicotine can increase or decrease anxiety-like behaviors in rats, depending on the dose of nicotine and the baseline state of anxiety-like behavior at testing (File et al., 1998b). Similarly, nAChR antagonists also have complex actions on anxiety-like behavior (File et al., 1998a; Newman et al., 2001; Newman et al., 2002). This complexity likely reflects populations of nAChRs located in different neurotransmitter systems in the brain that have opposing actions on anxiety behaviors (for reviews, see File et al., 2000a; File et al., 2000b). Consistent with this interpretation, administration of nicotine into the dorsal hippocampus increased anxiety-like behaviors in rats, and this effect was blocked by co-administration of the α7* nAChR-selective antagonist MLA (Tucci et al., 2003). Conversely, nicotine administered into the dorsal raphe nucleus decreased anxiety-like behaviors in rats, and this effect was abolished by DHβE (Cheeta et al., 2001a; Cheeta et al., 2001b). Interestingly, α7 knockout mice were shown to spend significantly more time in the center of an open-field apparatus than wildtype controls, suggesting that α7 knockout mice may have reduced levels of anxiety (Paylor et al., 1998). Importantly, however, Salas and colleagues did not observe any difference in anxiety-like behaviors between α7 knockout mice and wildtype controls (Salas et al., 2007). Recent data suggest that β3 nAChR knockout mice may display reduced anxiety-like behaviors compared with wildtype mice, reflected in more time spent on the open arm of an elevated plus-maze compared to wildtype littermates (Booker et al., 2007). β4 knockout mice also displayed decreased anxiety-like behaviors on an elevated plus-maze and staircase maze compared with wildtype mice (Salas et al., 2003b). The reduction in anxiety-like behaviors in β4 knockout mice compared with wildtype mice on the elevated plus maze was supported by telemetry measures of heart rate; the β4 knockout exhibited lower increases in heart rate than controls (Salas et al., 2003b). Therefore, these data suggest a role for the β3* and β4* nAChRs in anxiety-like behaviors in mice. In contrast to β3 and β4 knockout mice, α4 knockout mice were shown to spend significantly less time on the open arm of an elevated plus-maze apparatus than wildtypes (Ross et al., 2000), suggesting that α4 knockout mice may have an anxiogenic-like phenotype. Paradoxically, mice with a point mutation in the α4 nAChR subunit gene, which renders α4* nAChRs hypersensitive, also exhibited increased anxiety-like behaviors compared with wildtype controls (Labarca et al., 2001). Finally, anxiety-like behaviors were unaltered relative to wildtype controls in mice simultaneously lacking both the α7 and β2 nAChR subunits, although these mice exhibited deficits in a test of fear-based learning (Marubio and Paylor, 2004). These behavioral genetics data suggest that β3 nAChR subunits, and perhaps α7 and α4 subunits, may regulate anxiogenic-like actions of endogenous cholinergic transmission in the brains of mice. Furthermore, these observations highlight the complex and sometimes contradictory nature of nAChR modulation of anxiety states.

In common with abstinent human tobacco smokers, nicotine withdrawal elicits an anxiogenic-like state in rodents (Cheeta et al., 2001a; Irvine et al., 2001a; Irvine et al., 2001b; Biala and Weglinska, 2005; Jonkman et al., 2005). The nAChR antagonist DHβE increases anxiety-like behaviors in nicotine-dependent mice (Damaj et al., 2003). β2 knockout mice do not shown the decreased time spent on the open arm of an elevated plus-maze (i.e., increased anxiety-like behavior) usually observed in wildtype mice during mecamylamine-precipitated nicotine withdrawal (Jackson et al., 2008). Importantly, nicotine withdrawal elicits an increase in anxiety-like behavior in α5 and α7 knockout mice that is similar to the magnitude observed in wildtype mice (Jackson et al., 2008), suggesting that these nAChR subunits are not involved in the expression of nicotine withdrawal-associated increases in anxiety-like behaviors. Thus, α4* and β2*, but not α5* nor α7*, nAChRs likely regulate the anxiogenic-like state associated with nicotine withdrawal.

Finally, increased activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) may play an important role in the etiology of anxiety disorders, as well as depression and schizophrenia (see below). Accumulating evidence indicates that nAChRs regulate HPA function, possibly by modulating corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) and corticosterone levels. Axon terminals in the median eminence appear to contain CRF-like immunoreactive synaptic vesicles and membrane-bound nAChRs (Okuda et al., 1993). In rats, nicotine administered systemically or by self-administration acutely increased plasma levels of corticosterone and adrenocorticotropic hormone (Cam and Bassett, 1983; Chen et al., 2008), whereas chronic self-administration decreased CRF mRNA expression in the paraventricular nucleus (Yu et al., 2008). Mecamylamine-precipitated nicotine withdrawal enhanced anxiety-associated behaviors and CRF-like immunoreactivity in the amygdala, likely via CRF1 receptors (George et al., 2007), and CRF antagonism prevented, but could not reverse, the elevation of ICSS brain reward thresholds found during mecamylamine-precipitated nicotine withdrawal (Bruijnzeel et al., 2007). The nAChR subtypes that participate in the regulation of these effects on the HPA are unclear. Interestingly, however, β3 knockout mice had increased basal and stress-induced corticosterone levels compared with wildtype controls (Cui et al., 2003; Booker et al., 2007), suggesting increased stress responsively. Previously, systemic corticosterone administration was shown to reduce anxiety-like behavior in rats (File et al., 1979), possibly through feedback inhibition of stress cascades in the brain. Thus, the lower levels of anxiety-like behavior observed in β3 knockout mice may be secondary increased anxiety-reducing corticosterone. Further, these data implicate the β3* nAChR or non-β3* nAChRs that have undergone adaptation in the β3 knockout mice, in regulation of the HPA system.

Depression and subtypes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors

In humans, major depression often is comorbidly expressed with tobacco addiction, similar to the relationship described above between tobacco smoking and anxiety disorders (Breslau, 1995; Diwan et al., 1998). Human tobacco smokers are more likely than the general population to display symptoms of depression and to be diagnosed with major depression (Covey et al., 1997; Laje et al., 2001). Nicotine is reported to have mood-enhancing effects in smokers (Foulds et al., 1997), whereas cessation of the tobacco habit can precipitate depression-like systems in smokers (Glassman et al., 1990). Many antidepressant agents that are used to treat major depression can potently antagonize nAChRs (Fryer and Lukas, 1999; Miller et al., 2002; Shytle et al., 2002), and this action may contribute to their therapeutic effects. Thus, cigarette smoking may represent a form of self-medication behavior in depressed individuals in which the nicotine contained in tobacco smoke may induce antidepressant or other beneficial effects (Rabenstein et al., 2006).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants can increase limbic serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) transmission, and this action is hypothesized to contribute to their antidepressant actions. Additionally, antidepressants also increase the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in limbic brain regions, and this action also may contribute to the therapeutic utility of these agents (Nibuya et al., 1996; Duman et al., 1997). Consistent with an antidepressant-like action of nicotine, previous studies have shown that nicotine increases the release of serotonin from superfused hippocampal slices (Kenny et al., 2000b). Furthermore, chronic nicotine exposure increased BDNF mRNA in the hippocampus of rats (Kenny et al., 2000c), whereas nicotine withdrawal decreased hippocampal BDNF mRNA expression (Kenny et al., 2000c). These effects of nicotine could potentially contribute to the subjective mood-enhancing effects of the drug in human smokers, as well as the negative affect associated with nicotine withdrawal. Intriguingly, mecamylamine also increases hippocampal serotonin release similar to the stimulatory effects of nicotine (Kenny et al., 2000b), and also has antidepressant-like effects in animals (Caldarone et al., 2004; Rabenstein et al., 2006). Indeed, both nicotine and nAChR antagonists can potentiate the antidepressant-like effects of tricyclic antidepressant drugs in mice (Popik et al., 2003). These observations likely reflect preferential actions of nicotine and mecamylamine at different populations of nAChRs that have opposing actions, similar to the scenario described above for nAChR modulation of anxiety-like behaviors. Such an explanation would account for the apparently contradictory findings in which both an agonist (nicotine) and antagonist (mecamylamine) at nAChRs can elicit similar neurochemical and behavioral effects.