Abstract

To better understand adaptation to harsh conditions encountered in hot arid deserts, we report the first complete genome sequence and proteome analysis of a bacterium, Deinococcus deserti VCD115, isolated from Sahara surface sand. Its genome consists of a 2.8-Mb chromosome and three large plasmids of 324 kb, 314 kb, and 396 kb. Accurate primary genome annotation of its 3,455 genes was guided by extensive proteome shotgun analysis. From the large corpus of MS/MS spectra recorded, 1,348 proteins were uncovered and semiquantified by spectral counting. Among the highly detected proteins are several orphans and Deinococcus-specific proteins of unknown function. The alliance of proteomics and genomics high-throughput techniques allowed identification of 15 unpredicted genes and, surprisingly, reversal of incorrectly predicted orientation of 11 genes. Reversal of orientation of two Deinococcus-specific radiation-induced genes, ddrC and ddrH, and identification in D. deserti of supplementary genes involved in manganese import extend our knowledge of the radiotolerance toolbox of Deinococcaceae. Additional genes involved in nutrient import and in DNA repair (i.e., two extra recA, three translesion DNA polymerases, a photolyase) were also identified and found to be expressed under standard growth conditions, and, for these DNA repair genes, after exposure of the cells to UV. The supplementary nutrient import and DNA repair genes are likely important for survival and adaptation of D. deserti to its nutrient-poor, dry, and UV-exposed extreme environment.

Author Summary

D. deserti belongs to the Deinococcaceae, a family of bacteria characterized by an exceptional ability to withstand the lethal effects of DNA-damaging agents, including ionizing radiation, UV light, and desiccation. It was isolated from Sahara surface sands, an extreme and nutrient-poor environment, regularly exposed to intense UV radiation, cycles of extreme temperatures, and desiccation. The evolution of organisms that are able to survive acute irradiation doses of 15,000 Gy is difficult to explain given the apparent absence of highly radioactive habitats on Earth over geologic time. Thus, it seems more likely that the natural selection pressure for the evolution of radiation-resistant bacteria was chronic exposure to nonradioactive forms of DNA damage, in particular those promoted by desiccation. Here, we report the first complete genome sequence of a bacterium, D. deserti VCD115, isolated from hot, arid desert surface sand. Accurate genome annotation of its 3,455 genes was guided by extensive proteome analysis in which 1,348 proteins were uncovered after growth in standard conditions. Supplementary genes involved in manganese import, in nutrient import, and in DNA repair were identified and are likely important for survival and adaptation of D. deserti to its hostile environment.

Introduction

The surface sands of hot arid deserts are exposed to intense ultraviolet (UV) radiation, cycles of extreme temperatures, and desiccation. Nevertheless, an extensive diversity of bacterial species has been identified in such extreme and nutrient-poor environments [1],[2]. To better understand how life is adapted to these specific environmental conditions, we are characterizing Deinococcus deserti strain VCD115, recently isolated from upper sand layers of the Sahara [3].

D. deserti belongs to the Deinococcaceae, a family of extremely radiation tolerant bacteria that comprises more than 30 species in a single genus. Deinococci have been isolated from a wide range of environments, such as soil, water, air, faeces, hot springs and irradiated food [4]. Fourteen of the currently recognized Deinococcus species were isolated from arid environments, like desert soil and antarctic rock. Among the Deinococci, Deinococcus radiodurans is by far the best characterized and was first isolated more than 50 years ago from canned meat that had been exposed to a high dose of ionizing radiation [5]. Its genome sequence was published in 1999 [6]. More recently, the genome sequence of the slightly thermophilic Deinococcus geothermalis, isolated from a hot spring in Italy [7], was determined [8].

Heavy UV- and desiccation-induced damage to membranes, proteins and nucleic acids is lethal to most organisms. Vegetative bacteria that survive these stresses must therefore either protect vital components from damage and/or repair them efficiently, especially upon rehydration [9]. For D. radiodurans, it was suggested that its tolerance to high doses of ionizing radiation is a consequence of its response to natural DNA damaging conditions such as desiccation [10],[11]. Its extreme resistance phenotype has not been fully explained, but has been proposed to result from a combination of different molecular mechanisms and physiological determinants (for reviews, see [4],[12]). Repair of massive DNA damage in D. radiodurans involves widespread DNA repair proteins, such as RecA and PolA [13]. In addition, the use of microarrays resulted in the identification of various hypothetical genes highly induced following gamma irradiation or desiccation [11]. Of these, ddrA, ddrB, ddrC, ddrD and pprA genes were shown to be involved in DNA repair or radiation tolerance [11], and the proteins DdrA (DNA extremity protection) [14] and PprA (stimulation of ligase activity) [15] were characterized in vitro. Tolerance to desiccation and radiation does not only imply DNA repair but also protection of proteins from oxidative damage by a high intracellular Mn/Fe concentration ratio [16]. Moreover, D. radiodurans encodes plant protein homologs involved more exclusively in its tolerance to desiccation [17].

D. radiodurans is one of the first bacteria whose genomes were completely sequenced [6],[18]. Since this pioneering work, more than 600 bacterial genomes have been sequenced. However, very few of these organisms have been thoroughly analyzed at both the genome and proteome levels. Over recent years, various proteomic strategies based on liquid chromatography-coupled tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) technology were developed as an aid to genomic annotation [19]. Validation of the existence of orphan genes, prediction of short genes, annotation of genes with unusual codon usage, accurate determination of start codons, and post-translational modifications can be deduced through detection and sequencing of peptides [20],[21]. Such proteogenomic strategies were initially used to re-analyse previously annotated and published genomes such as the relatively small bacterial genome of Mycoplasma pneumoniae [22], and then larger genomes such as that of Shewanella oneidensis [23]. They were further applied to the primary annotation of a newly sequenced but related bacterium, Mycoplasma mobile [24]. Transcriptomics may also be helpful to validate gene predictions, and may lead to gene discovery when tiling arrays that span the entire genome are used [25].

To learn more about the mechanisms of adaptation of D. deserti to the harsh environmental conditions found in the Sahara desert, we determined and accurately annotated its entire 3.86 Mb genome sequence in parallel with an extensive proteome analysis. After the 777 kb genome of M. mobile, this is the second bacterial genome whose primary annotation was guided by proteomics. We developed a new strategy that allowed 40% coverage of the whole theoretical proteome for a standard cultivation condition only. In addition, the proteome analysis allowed correction of unexpected gene prediction errors. Comparative genomics combined with proteomics data revealed novel Deinococcus-specific proteins that could be involved in stress tolerance mechanisms, as well as specific characteristics of D. deserti VCD115 that may contribute to survival and adaptation of this unique bacterium to dry desert soil.

Results

Resistance of D. deserti to desiccation, UV and gamma radiation

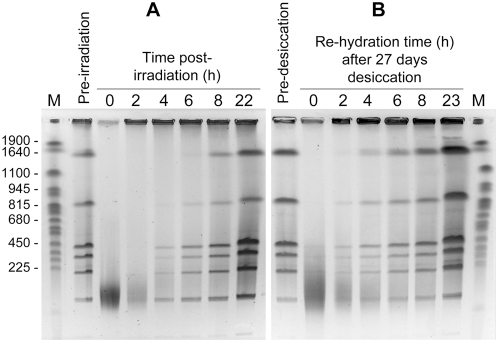

Besides its resistance to high doses of gamma and UV radiation [3], D. deserti also tolerated prolonged desiccation, with about 50% survival after 40 days of desiccation. Genome repair of D. radiodurans has been analyzed with cells grown and recovered in rich medium. As D. deserti is unable to grow in rich media, the fate of its DNA after exposure to a high dose of gamma radiation (6.8 kGy) or after 27 days of desiccation was analyzed with cells pre-grown and recovered in tenfold diluted tryptic soy broth (TSB/10). Like gamma-irradiation, desiccation generated numerous double-strand DNA breaks in D. deserti. An intact genome was reconstituted within six to eight hours under these conditions (Figure 1). Therefore, D. deserti's tolerance to desiccation is related to efficient DNA repair as found in D. radiodurans [10] rather than DNA protection mechanisms as observed in Nostoc commune [26].

Figure 1. Kinetics of genome reconstitution in D. deserti after gamma radiation and after desiccation.

D. deserti cells were subjected to 6.8 kGy gamma rays (Panel A) or 27 days of dessication (Panel B). Genomic DNA, purified from cells before irradiation or desiccation and at different times after irradiation or rehydration, was digested with PmeI and SwaI, resulting in 8 DNA fragments for an intact genome, and separated by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). Lanes M, Yeast Chromosome PFG Marker (New England Biolabs). Lengths (in kb) of several marker fragments are indicated on the left.

Genome sequence and structure: general features

The genome of D. deserti VCD115 is composed of four replicons: a main chromosome (2.82 Mb) and three plasmids, P1 (325 kb), P2 (314 kb) and P3 (396 kb) (Genbank accession numbers CP001114, CP001115, CP001116 and CP001117, respectively). Table 1 presents their main characteristics. Counting of sequence reads gave the relative abundance of each replicon: 1∶1∶1∶1 (±2%). Genome size and equimolarity of the four DNA entities were consistent with PFGE results (data not shown). The main chromosome contains three 16S rRNA genes at different locations, and three clusters located elsewhere that each contain one 23S and one 5S rRNA gene. A single cluster containing one 16S, one 23S and one 5S rRNA gene is also present on plasmid P1. The rRNA genes on P1 are identical to the corresponding genes on the chromosome.

Table 1. General characteristics of the D. deserti genome.

| Molecule | Chromosome | Plasmid P1 | Plasmid P2 | Plasmid P3 | All |

| General characteristics | |||||

| Size (bp) | 2,819,842 | 324,711 | 314,317 | 396,459 | 3,855,329 |

| GC content (%) | 63.38 | 60.7 | 63.53 | 61.41 | 62.96 |

| Coding density (%) | 85.53 | 72.53 | 83.74 | 78.56 | 84.31 |

| rRNAs | 9 | 3 | — | — | 12 |

| tRNAs | 48 | — | — | — | 48 |

| miscRNAsa | 5 | — | — | — | 5 |

| Repeat content (%) | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| IS contentb (%) | 0.3 | 2.05 | 1.46 | 1.97 | 0.71 |

| Proteins | |||||

| Protein-coding genes | 2,594 | 262 | 250 | 349 | 3455 |

| Detected by MS | 1,155 | 44 | 83 | 66 | 1,348 |

| With assigned function | 1,785 | 160 | 191 | 249 | 2,385 |

| Detected by MS | 918 | 34 | 65 | 53 | 1,070 |

| Conserved hypothetical | 611 | 32 | 32 | 45 | 720 |

| Detected by MS | 210 | 4 | 11 | 9 | 234 |

| Hypothetical | 198 | 70 | 27 | 55 | 350 |

| Detected by MS | 27 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 44 |

Other non-coding RNAs: one RNase P RNA, one SRP RNA, one tmRNA, two THI elements (TPP riboswitch).

Complete and partial IS elements.

Nine complete and different insertion sequences (IS), designated ISDds1 to ISDds9 according to the standard IS nomenclature with a total of 13 copies and belonging to 6 distinct IS families, were identified in D. deserti (Table S1; see also www-is.biotoul.fr). One of these, ISDds1 (an IS3 family member), is present in 5 copies, whereas each of the remaining 8 ISs is present in only one copy. Remarkably, D. deserti contains many fewer IS elements than D. radiodurans and D. geothermalis (Table S1): 13, 46 and 72, respectively. The IS family composition also differs in these species; for example, complete IS200/IS605 elements are absent in D. deserti but present in the other two Deinococci, while complete IS3 elements, present in D. deserti, are absent in D. radiodurans and D. geothermalis.

Proteome fractionation and extra-large MS/MS shotgun analysis

We investigated several strategies based on 1D SDS-PAGE and shotgun nanoLC-MS/MS to fractionate the D. deserti proteome from cells collected either in exponential phase or stationary phase: longer migration, increase of the percentage of acrylamide for covering low molecular weight proteins, additional separation by chromatography prior to SDS-PAGE. Ammonium sulphate precipitation followed by phenyl sepharose chromatography was a good means to considerably expand the proteome coverage, as measured by the number of proteins detected and their peptide coverage. Small coding sequences (CDSs) for non-conserved proteins are difficult to predict. Moreover, many small prokaryotic proteins are likely to show low gene expression levels as suggested by their low average codon adaptation index [27]. These low molecular weight proteins (below 50 kDa) represent two thirds of the theoretical proteome. We therefore identified these systematically using appropriate SDS-PAGE conditions. After 369 nanoLC-MS/MS runs on ESI-ion trap mass spectrometers, a large corpus of MS/MS spectra (264,251) was acquired. The MASCOT search engine was then used to identify tryptic peptides using various in-house D. deserti polypeptide databases that will be detailed below. Up to 11,129 unique peptides were identified when stringent search parameters were applied, corresponding to 1,348 proteins (Tables S2 and S3). Such 3D-fractionation resulted in an increased number of protein identifications compared to a single 1D SDS-PAGE shotgun, as well as a better protein sequence coverage with an average of 27% of the protein sequences determined by MS/MS.

Genome annotation guided by proteome data: a continuous back and forth strategy

The complete bacterial genome was automatically searched for CDSs with FrameD, software well suited for gene prediction in GC-rich bacterial genomes [28]. For proteogenomic annotation (Figure 2A), two polypeptide databases were constructed: a first version of CDS list (CDS1) containing 3,051 genes predicted by FrameD, and an open reading frame (ORF) list, ORF0. The latter comprised all six reading frames (65,801) with at least 100 nucleotides of length that were translated. We searched the two polypeptide databases with a preliminary corpus containing 33,480 MS/MS spectra. A large difference between the two lists of identified proteins was observed, i.e. 344 proteins found in CDS1 and 423 in the ORF0 database, indicating that approximately one fifth of the genes were not correctly predicted with the settings chosen for FrameD inspection. These results led us to further annotate intergenic regions with the recently developed Med 2.0 algorithm [29]. A second version of CDS list (CDS2) was established and contained 486 additional polypeptides. The CDS2 and ORF0 polypeptide databases were searched with the final corpus of MS/MS spectra that was collected in the meantime. Again, some differences between the two lists of identified proteins were observed, leading to the discovery and manual validation of 15 new genes. We further manually inspected intergenic regions and found 21 additional genes. Finally, we manually checked the annotation and translational start codons of the entire set of genes to create a refined CDS database, CDS3, containing 3,455 CDSs (Table 1). Using CDS3, 1,348 proteins were validated with stringent search parameters (Tables S2 and S3). These shotgun data indicate that at least 40% of the genes were expressed in the standard growth conditions at a sufficient level to be detected by MS. Among the 3,455 genes found in the D. deserti genome, 720 are predicted to code for conserved hypothetical proteins and 350 for orphans (Table 1). Our MS data definitively validate the expression of 234 of the former and 44 of the latter (Table S2).

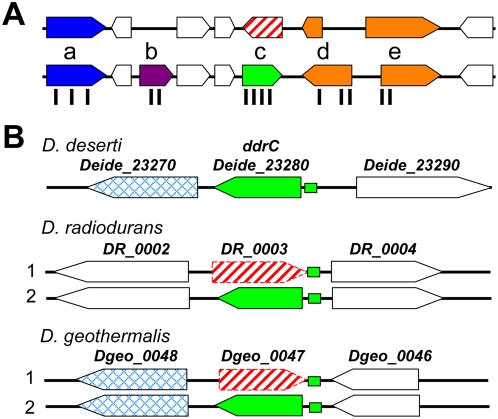

Figure 2. Gene prediction corrections revealed by proteomics and comparative genomics.

(A) Schematic representation of the proteogenomic annotation strategy of D. deserti genome. First, genes were automatically predicted (upper part). Peptides detected by MS, represented by vertical black bars, were then located on the corresponding nucleic acid loci (lower part). Manual validation revealed various cases: (a) validation of predicted genes, (b) detection of non-predicted genes, (c) reversal of gene orientation, and (d, e) correction of start codons. (B) Reversal of ddrC gene orientation in D. radiodurans and D. geothermalis. Several data revealed that the orientation of DR_0003 and Dgeo_0047 (red broken arrows) has to be reversed, resulting in genes highly homologous to correctly predicted Deide_23280 (green arrows). Previous and corrected annotations are labeled 1 and 2, respectively. Green boxes represent the radiation response motif upstream of correct ddrC genes. Flanking genes Deide_23270 and Dgeo_0048 are homologs.

We checked more specifically for N-terminal peptides in the CDS3 and ORF0 lists and verified their adequacy with predicted translational start codons. We found 212 distinct peptide signatures corresponding to 145 N termini of proteins (Table S3). These data confirmed the starts of 112 proteins but also corrected the starts of 33 polypeptides that were incorrectly predicted even after manual inspection.

Reversal of direction of several ORFs upgrades DNA damage response knowledge

Besides detecting non-predicted coding sequences and correcting start codons, comparing theoretical annotation and MS data led to the discovery of another unexpected computational prediction error in D. deserti (Figure 2A). Deide_19980 was first predicted on the forward strand. As four identified peptides correspond exactly to the polypeptide encoded on the reverse strand at the same locus, we corrected the orientation of this gene and replaced Deide_19980 with Deide_19972 in the opposite orientation. Remarkably, comparative genomics with D. radiodurans and D. geothermalis suggests various prediction errors in these species as well (Table 2). For example, we found four different peptides substantiating the existence of Deide_15980, initially thought to be a D. deserti-specific protein (Figure S1). However, protein sequences highly homologous to Deide_15980 are found when DR_0869 (D. radiodurans) and Dgeo_0511 (D. geothermalis) are translated in the reverse direction. Therefore, DR_0869 and Dgeo_0511 should be reassessed, possibly reversing their orientation. D. deserti's genome was further manually scrutinized for such errors. For 35 D. deserti genes, previously unpredicted homologs were identified in D. radiodurans and/or D. geothermalis, and these include nine additional instances of reversal of gene orientation (Table 2). Twenty-six of the conserved but differently annotated loci are present in each of the three sequenced Deinococcus genomes. Interestingly, two of these correspond to DNAdamage response genes ddrC (DR_0003; Dgeo_0047) and ddrH (DR_0438). Their gene products have not been characterized, but DR_0003 has been inactivated, resulting in decreased radiation resistance [11]. Homologs of the reported DdrC and DdrH proteins were not found in the D. deserti protein database. However, when the orientations of DR_0003 and Dgeo_0047 are reversed, proteins highly homologous to Deide_23280 are found (Figures 2B and S2). The data strongly suggest that DR_0003 and Dgeo_0047 were incorrectly annotated and that Deide_23280 and its homologs are the correct genes. Indeed, Deide_23280 and homologs are much more similar to each other than the DR_0003 homologs (Figure S2); specific RT-PCR experiments showed that Deide_23280 is transcribed in D. deserti (Figure S3); and a palindromic motif identified in the upstream regions of genes that are induced upon radiation/desiccation [8] is present upstream of Deide_23280 and its two homologs (Figure 2B). For ddrH, a homolog of DR_0438 was not found in D. geothermalis [8]. However, if DR_0438 is transcribed from the opposite DNA strand, homologs are found in D. geothermalis (Dgeo_0322) and D. deserti (Deide_20641). These protein similarities suggest that Deide_20641 and Dgeo_0322 are the correctly annotated ddrH (Figure S4). The sequences of the bona fide DdrC, DdrH and the other newly recognized Deinococcus-specific proteins (Table 2) do not contain any described domain or motif. Characterization of their function and structure requires further experimental analysis.

Table 2. Differently annotated conserved loci in D. deserti, D. radiodurans, and D. geothermalis.

| D. deserti | D. radiodurans | D. geothermalis a | Comments |

| Deide_06040 (262) | reverse DR_0908 (262) | Dgeo_0637 (266) | conserved |

| Deide_11910 (249) | reverse DR_1566 (251) | Dgeo_1299 (236) | 8 conserved cysteines; Fe-S cluster |

| Deide_13820 (136) | reverse DR_0818 (130) | Dgeo_0854 (133) | Deinococcus-specific |

| Deide_14940 (331) | reverse DR_1660 (327–368) | — | conserved |

| Deide_15980 (192) | reverse DR_0869 (192) | reverse Dgeo_0511 (185) | Deinococcus-specific |

| Deide_16650 (73) | reverse DR_0371 (73) | Dgeo_1881 (73) | Deinococcus-specific |

| Deide_18240 (199) | reverse DR_0931 (frameshift?) | downstream Dgeo_0497 (199) | Deinococcus-specific membrane protein |

| Deide_20641 (82) | reverse DR_0438 (92) | Dgeo_0322 (82) | ddrH |

| reverse Deide_23061 (61) | upstream DR_2438 (59) | Dgeo_2289 (89–171?) | hypothetical |

| Deide_23280 (232) | reverse DR_0003 (231) | reverse Dgeo_0047 (229) | ddrC |

| Deide_1p00840 (283) | reverse DR_A0170 (325) | Dgeo_2841 (304) | intradiol dioxygenase |

| Deide_00870 (136) | DR_2373 (136) | upstream Dgeo_2056 (136) | conserved |

| Deide_01520 (60) | upstream DR_2353 (60–130) | upstream Dgeo_0094 (62) | Deinococcus-specific membrane protein |

| Deide_02110 (236) | DR_2585 (227) | Dgeo_0028 (695nt); not in Genbank; frameshift? | conserved |

| Deide_02380 (106) | downstream DR_2376 (>42?) | Dgeo_0116 (94) | Deinococcus-specific |

| Deide_03200 (56) | downstream DR_1936 (56) | Dgeo_0456 (56) | Deinococcus-specific membrane protein |

| Deide_03861 (126) | DR_1855 (126) | upstream Dgeo_1580 (125) | comEA |

| Deide_04640 (120) | upstream DR_2629 (109) | — | membrane protein |

| Deide_05260 (62) | — | downstream Dgeo_0866 (66) | Deinococcus-specific |

| Deide_07560 (51) | between DR_1662/DR_1663 (46) | upstream Dgeo_0448 (50) | Deinococcus-specific |

| Deide_09630 (147) | downstream DR_1062 (218?) | Dgeo_0746 (144) | conserved membrane protein |

| Deide_10900 (164) | DR_0846 (175) | upstream Dgeo_1265 (167–178) | peroxiredoxin |

| Deide_11240 (103–162?) | between DR_2165/DR_2166 (103–346?) | Dgeo_1280 (170?) | rhodanese-like |

| Deide_11250 (92) | DR_0570 (93) | upstream Dgeo_1280 (101) | rhodanese-like |

| Deide_13440 (57) | upstream DR_2194 (57) | Dgeo_1152 (57) | lysW |

| Deide_14300 (122) | DR_1990 (129) | downstream Dgeo_0594 (123) | Deinococcus-specific; signal peptide |

| Deide_14920 (163) | — | downstream Dgeo_0948 (162) | signal peptide; SCP domain |

| Deide_17020 (290) | upstream DR_2201 (286–303) | Dgeo_1405 (285) | conserved |

| Deide_17971 (53) | DR_1463 (97) (too long? 61 aa?) | downstream Dgeo_1389 (49) | Deinococcus-specific |

| Deide_19480 (133) | upstream DR_2342 (99–289) | Dgeo_2141 (137) | fur |

| Deide_19965 (63) | — | upstream Dgeo_0366 (63) | Deinococcus-specific |

| Deide_20690 (83) | upstream DR_0433 (84) | upstream Dgeo_0316 (82–105) | Deinococcus-specific |

| Deide_1p01660 (346) | — | Dgeo_2813 (920nt); not in Genbank; frameshift? | mannonate dehydratase |

| Deide_2p00970 (81) | — | downstream Dgeo_1505 (78) | Deinococcus-specific |

| Deide_2p00990 (444) | — | downstream Dgeo_0929 (450) | erythromycin esterase |

| Deide_2p01000 (227) | — | downstream Dgeo_0931 (220) | phosphoribosyltransferase |

For the first 11 loci in this table, the orientation of one or two of the predicted genes has to be reversed. For the other loci, a gene was not predicted in one or two species, but found near the indicated locus. The products of the 18 D. deserti genes indicated in bold face were identified in the proteome analysis after standard cultivation. Lengths of gene products are indicated between parentheses.

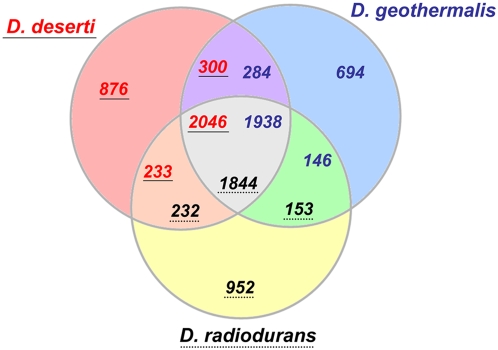

Genome comparisons and Deinococcus-specific genes

Entire genome comparisons showed that 2,046 of the predicted gene products of D. deserti are homologous (at least 30% identity and 70% coverage) to proteins from both D. radiodurans and D. geothermalis (Figure 3). These correspond to 1,844 and 1,938 proteins in D. radiodurans and D. geothermalis, respectively, showing that D. deserti globally has more paralogous CDSs. Multiple paralogs are found for exported S8 peptidases, exported serine proteinases, cold shock proteins, and several DNA repair proteins (see below). For example, each of the three cold shock proteins Deide_09930, Deide_2p00490 and Deide_3p00840 is homologous to only one protein of D. radiodurans (DR_0907) and two of D. geothermalis (Dgeo_0638 and Dgeo_1006). For 876 D. deserti proteins, no homolog was detected in D. radiodurans or D. geothermalis (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Orthologous gene comparison between the three sequenced Deinococcus strains.

Orthologous genes are defined by BLAST search when their gene products shared a minimum of 30% identity and 70% coverage. The circle intersections give the number of genes found in two or three of the compared species, including paralogous CDSs. Numbers of genes specific to each species are represented outside these areas. D. deserti gene numbers are in red and underlined, those of D. radiodurans are in black with dotted underlining, and those of D. geothermalis are in blue and not underlined.

Pairwise comparisons of the different replicons of D. deserti with those of the other two Deinococcus species revealed strong homologous relationships (Table S4) and significant levels of gene order conservation (Figure S5) between the main chromosomes. As determined by reciprocal best hit analysis, the chromosome of D. deserti shares 1,686 and 1,804 gene homologs respectively with those of D. radiodurans and D. geothermalis. Although each of the three D. deserti plasmids contain genes and gene clusters that are conserved in D. radiodurans and D. geothermalis, D. deserti plasmid P2 appeared to have the highest levels of homology with D. geothermalis plasmid pDSM11300 (DG574) and with D. radiodurans chromosome 2 (Table S4). No or very little homology was observed between D. deserti, and D. radiodurans plasmid pCP1 or D. geothermalis plasmid pDGEO02. Overall, a reciprocal best hit with D. radiodurans and/or D. geothermalis was found with 80, 35, 65 and 40% of the genes present on the D. deserti chromosome and plasmids P1, P2, and P3, respectively. Among those without reciprocal best hits are genes related to functions such as signal transduction and regulation, cell envelope biogenesis, DNA repair, nutrient metabolism and transport.

The distinctive characteristics of Deinococcus bacteria are likely in part determined by proteins that are unique in this genus. We have identified 230 proteins, mostly of unknown function and including six identified after reversal of gene orientation, that are specifically conserved in the three sequenced Deinococcus genomes (Table S5). A role in radiotolerance has been demonstrated for a few of these, e.g. IrrE (also called PprI) [30],[31] and PprA [15]. Predicted membrane and exported proteins, accounting for 39% of the Deinococcus-specific proteins, may contribute to cell envelope integrity, stress tolerance and viability. Indeed, two desiccation resistance-associated proteins (Deide_07540 and Deide_09710) have a predicted signal-peptide and are likely functional outside the cytoplasm. Of the 230 Deinococcus-specific proteins, 92 were detected in our proteome analysis (Table S5), many among the highly expressed proteins, strongly suggesting their importance in general metabolism and perhaps cell viability and stress resistance in D. deserti.

Adaptation to extreme environment

D. radiodurans has very high intracellular manganese and low iron levels [32], which are correlated with protection of proteins from oxidative modifications [16]. D. deserti was also found to accumulate Mn, with Mn/Fe ratios of 0.54 and 1.05 in two different growth media (Table S6). These ratios were even higher than found with D. radiodurans in the same experimental conditions: 0.16 and 0.47, respectively. We checked for the presence of Mn- and Fe-transport and regulation related-systems in D. deserti (Table S7). While only one ABC-type Mn/Zn transport system, composed of an ATPase, a permease and a periplasmic component, is present in D. radiodurans and D. geothermalis, several homologs of these components are encoded in D. deserti: three ATPases, five permeases and three periplasmic components. A distantly related homolog of the Nramp family of Mn(II) transporters was also found. The Mn-dependent transcriptional regulator TroR/DtxR is triplicated in D. deserti. For Fe-homeostasis, some differences were observed between the three Deinococcus strains (Table S7). The specific presence in D. deserti genome of an operon comprising two homologous genes specifying siderophore synthetase components is remarkable. Several differences were also observed for proteins related to oxidative stress response (Table S8). Four SoxR-related transcriptional regulators occur in D. deserti while only one and two are found in D. geothermalis and D. radiodurans, respectively.

Like D. radiodurans and D. geothermalis, D. deserti contains four close homologs of plant desiccation resistance-associated proteins (Table S8). Interestingly, three of these were detected in D. deserti after standard cultivation, suggesting their importance for swift adaptation to rapid environmental changes occurring in the hot desert. The products of many other stress response-related genes were also detected in the proteome analysis (Table S8).

Besides having more Mn ABC transporter proteins, D. deserti is also rich in ABC transporters for oligopeptides, amino acids and sugars in comparison to D. radiodurans and D. geothermalis (Table S9). Thirty-one of 90 amino acid and peptide transporter proteins are specific to D. deserti, as are 17 of 54 proteins for sugar transport. Several components of these ABC transporters were detected by the proteome analysis (Table S9), showing that they are used by the bacterium in standard cultivation conditions. A large diversity in ABC transporters is likely important for D. deserti's adaptation to the desert where nutrients are limiting, and for osmoprotection in the case of glycine/betaine transporters.

D. deserti genome contains three recA and three TLS polymerase genes

D. deserti has many DNA repair genes in common with D. radiodurans and D. geothermalis (Table S10), but several interesting specific D. deserti features were also observed (Table 3). Surprisingly, three different recA genes were found. RecA is a key component in DNA repair, and required for extreme radiation tolerance in D. radiodurans. Most other known bacterial species possess a single recA. The presence of multiple recA genes has been reported for only three species: two in Myxococcus xanthus [33] and Bacillus megaterium [34], and seven in the cyanobacterium Acaryochloris marina [35]. The recA genes on plasmid P1 and P3 code for identical proteins. They share 81% identity with the chromosome-encoded RecA. As in D. radiodurans and D. geothermalis, the chromosomal recA of D. deserti is the last gene in an operon that also contains cinA and ligT, encoding a DNA damage/competence-inducible CinA-like protein and a 2′-5′ RNA ligase, respectively. For both the chromosome-encoded RecA (90% identical residues) and the plasmid-encoded RecA (80% identical residues), the best hits in BLAST analyses were the RecA proteins from D. radiodurans and D. geothermalis. Moreover, unlike the other two Deinococci, D. deserti possesses three putative translesion synthesis (TLS) DNA polymerases: a Pol II homolog (PolB); a protein distantly related to members of the DinB subfamily of Y-family DNA polymerases; and DnaE2, a potential error-prone DNA polymerase homologous to the alpha subunit DnaE of the major replicative DNA polymerase III (Table 3). In addition, the D. deserti genome encodes a protein related to DNA repair photolyases, a 5′-3′ exonuclease distantly related to Escherichia coli exonuclease IX, and a large multidomain helicase (Deide_06510) also found in Thermus thermophilus HB27. There are also two DnlJ DNA ligases sharing 57% identity while the other Deinococci contain only one dnlJ gene. D. deserti also possesses two genes encoding proteins highly homologous to DdrO (DR_2574), a proposed regulator of the radiation response regulon in D. radiodurans [8], Deide_20570 and Deide_3p02170 sharing 95% and 85% identity respectively with DR_2574. On the contrary, D. deserti has only one ung/udg homolog for uracil-DNA glycosylase, whereas D. radiodurans has three and D. geothermalis two (Table 3). Four ssb gene homologs were detected in D. geothermalis, while only one is present in the other two Deinococci.

Table 3. Main differences among Deinococci regarding DNA repair proteins.

| D. deserti | D. radiodurans | D. geothermalis | Protein name and description |

| Deide_19450 (355), Deide_1p01260 (344), Deide_3p00210 (344) | DR_2340 (363) | Dgeo_2138 (358) | RecA |

| Deide_1p00180 (765) | — | — | DNA polymerase II |

| Deide_1p01880 (423) | — | — | Y-family DNA polymerase |

| Deide_1p01900 (1058) | — | — | error-prone DNA polymerase DnaE2 |

| Deide_3p02150 (354) | — | — | DNA repair photolyase |

| Deide_20570 (129), Deide_3p02170 (129) | DR_2574 (131) | Dgeo_0336 (140) | DdrO; transcriptional regulator |

| Deide_11320a (731) | DR_1289b (824) | Dgeo_1226b (195) | DNA helicase RecQ |

| Deide_1p01280b (548) | — | — | DNA helicase, RecQ family |

| Deide_06510b (1683) | — | — | Multidomain protein: DnaQ/DinG/RecQ |

| Deide_06520 (849) | — | — | UvrD/REP helicase |

| Deide_17790 (202), Deide_05970 (204) | DR_0856 (197) | Dgeo_1818 (180) | DnaQ |

| Deide_12290 (686), Deide_1p00290 (686) | DR_2069 (700) | Dgeo_0696 (684) | DNA ligase, NAD-dependent |

| Deide_1p00132 (244) | — | — | 5′-3′ exonuclease |

| Deide_00830 (248) | DR_0689 (247), DR_1751 (237), DR_0022 (199) | Dgeo_2059 (245), Dgeo_1556 (230) | Uracil-DNA glycosylase (Ung/Udg) |

| Deide_00120 (297) | DR_0099 (301) | Dgeo_0165 (301), Dgeo_2964 (283), Dgeo_2969 (352), Dgeo_3087 (200) | Single-stranded DNA-binding protein |

Polypeptide lengths are indicated between parentheses.

Two HRDC domains were found in Deide_11320, three in DR_1289, and one in Dgeo_1226.

No detectable HRDC domain.

Among the 92 DNA repair and radiation tolerance-associated proteins of D. deserti listed in Table S10, 36 were identified in the proteome analysis, indicating detectable basal levels of these proteins in the absence of exposure to exogenous DNA damaging agents. Among these are DNA glycosylases, nucleotide excision and recombinational repair proteins, several “house-cleaning” Nudix hydrolases, both DNA ligases, and the DNA repair regulator and putative sensor protein IrrE (PprI). Such basal cellular levels of DNA repair proteins might be expected if DNA damage occurs frequently due to generation of high levels of metabolism-derived reactive oxygen species or if cells must be constantly ready to quickly respond to external stress.

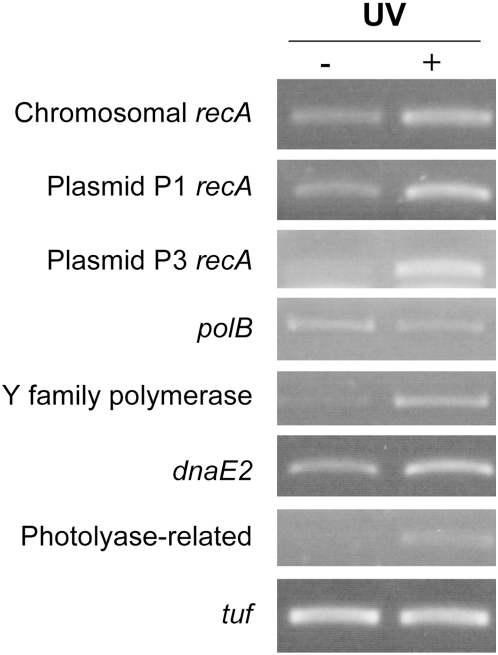

The chromosome-encoded RecA was detected by the proteome analysis, whereas peptides that specifically demonstrate the presence of plasmid-encoded RecA were not identified. Similarly, none of the TLS polymerases was detected after standard cultivation. However, RT-PCR experiments showed that the three recA, the three TLS polymerase genes and the photolyase-related gene were transcribed. Moreover, except for polB, transcription of each of these genes was induced after exposure to UV (Figure 4), indicating a role in the DNA damage response in D. deserti.

Figure 4. RT-PCR analysis of recA and putative translesion DNA polymerase and photolyase genes.

RNA was isolated 30 min after exposure to 0 (−) or 250 (+) J.m−2 UV. The constitutively expressed tuf gene was included as control.

The Deinococcus radiation response regulon is conserved

A potential common radiation response regulon in D. radiodurans and D. geothermalis identified by a palindromic motif has been reported [8]. This radiation/desiccation response motif is found in the upstream regions of radiation-induced genes such as recA, ddrA, ddrO, pprA, uvrA, and gyrA. Induction of transcription of at least recA and pprA is IrrE (PprI)-dependent in D. radiodurans [30],[31]. We searched for such motif in D. deserti and detected its signature in the upstream regions of the same genes and, in addition, upstream of Deide_23280 (the bona fide ddrC) and the two plasmid-encoded recA genes (Table S11). Therefore, the radiation response regulon is a general trait of Deinococcus species. This is further supported by the observation that D. deserti IrrE fully restored radiation resistance when expressed in a D. radiodurans irrE deletion mutant [36]. The motif was not found near the other additional D. deserti DNA repair genes listed in Table 3, including those specifying the photolyase-related protein and TLS DNA polymerases. These may be regulated in another manner. Interestingly, the palindromic motif was also found near several genes that have no obvious relation with DNA repair, notably near Deide_18730, the first of five uncharacterized genes in a putative operon that is conserved in various species but absent from D. radiodurans and D. geothermalis.

Discussion

D. deserti was isolated from the surface sand of the Sahara, an extreme environment, where it is exposed to harsh conditions with concomitant UV irradiation, desiccation and nutrient limitation. To learn more about the adaptation of D. deserti to arid desert as well as the remarkable tolerance to radiation and desiccation of Deinococcaceae in general, we determined the sequence of its entire genome, composed of a chromosome and three large plasmids. Moreover, accurate gene annotation was guided by extensive proteome analysis after growth of D. deserti under standard conditions. Besides validation of about 40% of the predicted genes, peptide data allowed correction of several initiation codons, identification of unpredicted genes and, surprisingly, reversal of incorrectly predicted gene orientation. Comparative genomics and proteomics showed that the orientation of several annotated D. radiodurans and D. geothermalis genes should also be reversed. This is an important matter and to our knowledge has never been reported previously at the genomic scale. Interestingly, transcription of two of these, ddrC and ddrH, was induced in D. radiodurans after exposure to radiation and desiccation [11]. These transcription data may seem contradictory to our results. However, we believe that Tanaka et al. [11], without awareness, measured transcription of the correct ddrC and ddrH genes. Their transcription analyses could not distinguish between one DNA strand and its complementary strand since the DNA spotted on the microarrays were obtained by PCR, and thus included both DNA strands. Moreover, random hexamers were used for initiation of cDNA probe synthesis (A. Earl, personal communication), and these hexamers annealed with any RNA, including the correct ddrC and ddrH mRNA. Several other previously unannotated genes were found in D. geothermalis and/or D. radiodurans, including homologs of Deide_17971 and Deide_19965, genes that were not predicted but whose products were detected by proteomics. These and 5 other genes that were discovered by proteomics, code for very small polypeptides of 4.5–9.6 kDa. Our work shows that a combination of high-throughput proteomic and genomic techniques allows the most accurate genome annotation presently obtainable. By extension, the annotation of the whole Deinococcus-Thermus group may be revisited taking into account evolutionary constraints, a concept already applied to the genera Shewanella and Mycobacterium [20],[21].

Besides proteogenomic annotation, shotgun proteomics allows semi-quantitation of the major proteins by spectral counting. Since the demonstration by Liu et al. [37] that spectral counts of MS/MS spectra for a given protein in a mixture correlated linearly with protein abundance within over two orders of magnitude, numerous semi-quantitative studies have been based on this concept [38]. Among the 264,251 MS/MS spectra that were acquired, 50,461 spectra were confidently assigned to a peptide sequence. Averages of 4.5 spectra per unique peptide and 37 spectra per protein were reached taking into consideration the global set of data. The redundancy is even higher for abundant proteins. Although these data are only semi-quantitative and extracted from the entire set of MS/MS spectra recorded in this study, several interesting features should be noted. In our MS/MS corpus, 50% of the spectra were attributed to 106 proteins, 75% to 281 proteins, and 90% to 547 proteins (Table S2). Interestingly, among the highly detected proteins are several orphans (Deide_3p02433, Deide_15630, and Deide_11191), Deinococcus-specific proteins (Deide_06180, Deide_1p01253, Deide_21340, Deide_11730, Deide_16050, Deide_16110, Deide_09460, Deide_01434, and Deide_15100) and more widely conserved proteins (Deide_3p01280, Deide_21050, Deide_13500, Deide_04930, and Deide_14540) of unknown function, suggesting an important role in D. deserti. The proteome data indicate that plasmids P1 and P3 are underused in our standard growth conditions in comparison to P2 and the chromosome. The products of 17–19% of the genes present on P1 and P3 were detected, compared to 34–45% of those on the chromosome and P2. These data suggest that most of the P1 and P3 genes may be used under more specific conditions (such as in the desert and/or after stress) than the laboratory conditions used here.

Extreme tolerance to radiation and desiccation in Deinococci requires efficient DNA repair. In addition to most of the classical DNA repair genes, the previously identified novel, Deinococcus-specific genes involved in DNA repair and radiotolerance, i.e. ddrA-D, pprA and irrE (pprI), are all conserved in D. deserti. In addition, using epifluorescence microscopy, we have observed that D. deserti (results not shown), like other radioresistant bacteria [39], has a highly condensed nucleoid, which may restrict diffusion of radiation/desiccation-generated DNA fragments. Furthermore, in common with D. radiodurans and D. geothermalis, D. deserti has a high Mn/Fe ratio, important for protein protection.

Besides the common set of genes and characteristics involved in protection or repair, each species has probably also evolved specific functions to adapt to its environment. This is supported by the identification of several genes for which a role in stress resistance and DNA repair has been shown or can be expected, but that are not shared by the Deinococci. For example, homologs of D. radiodurans irrI, associated with radiation resistance [40], and several radiation-induced ddr genes [11], are absent in D. deserti and D. geothermalis (Table S10). As another example, the conserved radiation response motif was found upstream of two D. deserti genes of unknown function with a homolog only in D. geothermalis (Deide_04721) or without homologs in the other Deinococci (Deide_18730). The latter is the first gene of a putative operon encoding five uncharacterized proteins, of which Deide_18710 (related to MoxR-like AAA+ ATPases) could function with Deide_18690 (containing a Von Willebrand Factor Type A domain) as a chaperone system for the folding/activation of specific substrate proteins [41].

Another interesting feature is the presence in D. deserti of TLS DNA polymerase genes, as well as a photolyase-related gene and two supplementary recA, all present on plasmid P1 or P3. All of these genes could be involved in tolerance to UV-light. E. coli RecA plays a major role in recombinational repair of UV-lesions, has a regulatory role in lesion bypass through its coprotease activity, which includes stimulation of self-cleavage of repressor protein LexA, and participates directly in lesion bypass by interacting with TLS Pol V [42],[43]. As the three TLS DNA polymerase genes in D. deserti are located on plasmid P1, it is tempting to speculate that the plasmid-encoded RecA is involved in regulation and/or activation of one or more of these TLS polymerases. Moreover, a lexA homolog, Deide_1p01870, is adjacent and possibly in an operon with the TLS DNA polymerase genes Deide_1p01880 (Y-family DNA polymerase) and Deide_1p01900 (DnaE2). Similar so-called adaptive mutagenesis gene cassettes have been recently described and shown to be under RecA/LexA regulation in several bacterial species [44], and a role for the Y-family DNA polymerase and/or DnaE2 in survival and induced-mutagenesis after exposure to DNA-damaging conditions has been demonstrated in Mycobacterium tuberculosis [45], Caulobacter crescentus [46] and Pseudomonas putida [47].

Taken together, the supplementary nutrient import and DNA repair genes in D. deserti may contribute to survival in nutrient-poor extreme conditions. The additional DNA repair genes likely provide an advantage in an environment where many DNA lesions can be generated due to intense UV irradiation and desiccation. Moreover, TLS polymerases generate mutations that will increase genetic diversity, which may lead to better adaptation to harsh conditions, such as those encountered in the desert [48].

Materials and Methods

Genome sequencing

The complete sequence of D. deserti VCD115 was determined after genomic DNA fragmentation by mechanical shearing or BamHI partial digest for the construction of plasmid and large insert libraries, respectively. The 3 kb (A), 10 kb (B) and 25 kb (C) fragments were cloned into pcDNA2.1 (INVITROGEN), pCNS (pSU18 derived) and pBeloBac11, respectively. Vector DNAs were purified and end-sequenced (49536 (A), 16128 (B) and 7680 (C)) using dye-terminator chemistry on ABI3730 sequencers. A pre-assembly was made without repeat sequences as described [49] using Phred/Phrap/Consed software package (www.phrap.org). The finishing step was achieved by primer walking and PCR. A complement of 665 sequences was needed for gap closure and quality assessment.

Gene prediction and annotation

Protein-coding regions in the assembled genome sequence were identified using FrameD [28] and MED [29]. Predicted proteins larger than 10 amino acids were analysed for sequence similarity against protein databases (SWISSPROT, TREMBL and non-redundant GenBank proteins). Similarity searches were carried out using BLAST programs [50]. Annotation of the complete genome was performed using GenoBrowser, an in-house bioinformatic tool for data management (Ortet et al., submitted). Our tool allows an expert annotation by manual verification and curation of functional protein categories after automatic assignment. Genome regions without match were re-evaluated by using BLASTX as initial search, and ORFs were extrapolated from regions of alignment. rRNA and tRNA genes were identified with BLASTN and tRNA-Scan [51]. miscRNA were identified using INFERNAL software suite with RFAM database [52] version 8.1 containing 607 families. Repeats were identified using RepSeek [53].

Genbank submission

The annotated genome sequence of D. deserti VCD115 was deposited in the GenBank database with accession numbers CP001114, CP001115, CP001116 and CP001117 for the main chromosome, plasmids P1, P2 and P3, respectively.

Comparative genomics

All predicted D. deserti proteins were aligned using BLASTP against the available proteomes of published complete bacterial genomes (625 genomes). The results of these searches, requiring bi-directional best hit (BBH) among all possible pairwise comparisons, were used to determine the presence of homologs in different species.

Proteome fractionation by phenyl sepharose and SDS-PAGE

D. deserti cells grown in tenfold diluted tryptic soy broth (TSB/10) supplemented with trace elements [36] and harvested in exponential growth and in pre-stationary phase (4 g of wet material) were resuspended in 20 mL of cold 100 mM TRIS/HCl buffer (pH 8.0 at 20°C) containing 5 mM EDTA, disrupted and centrifuged. Proteins from 8 mL of both resulting supernatants were subjected to ammonium sulphate precipitation. Proteins still soluble after addition of 50% final (NH4)2SO4 were precipitated with 67% final (NH4)2SO4. The resulting four equivalent pellets were resuspended in 50 mM TRIS/HCl buffer pH 8.0, containing 2.5 mM EDTA and 1.5 M (NH4)2SO4 (Buffer A). Proteins from each of the four samples were applied at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min onto a 5 mL HiTrap Phenyl HP column (Amersham Biosciences) previously equilibrated with Buffer A. After wash with Buffer A, proteins were eluted over a 60 mL linear gradient comprising 1.5–0 M (NH4)2SO4. Eluted proteins (24 fractions per phenyl chromatography) were precipitated by trichloroacetic acid (10% final) and collected by centrifugation. Proteins were dissolved in LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen) and then analyzed by SDS-PAGE on 4–12% gradient NuPAGE (Invitrogen) gels. The gels were stained with Coomassie Safe Blue stain (Invitrogen) and then each relevant lane was excised into 4–10 mm-thick pieces from the top to the bottom polypeptide bands.

In-gel proteolysis

Protein bands were washed with MilliQ water, treated with CH3CN, and then with 100 mM NH4HCO3. Gel pieces were dehydrated with 100% CH3CN and dried for 20 min under vacuum. For in-gel digestion, dry gel pieces were rehydrated for 45 min at 56°C with 100 mM NH4HCO3 containing 10 mM DTT. Gel pieces were rinsed with CH3CN, treated with 100 mM NH4HCO3 containing 55 mM iodoacetamide, then dehydrated with 100% CH3CN and dried for 20 min under vacuum. For in-gel digestion, dry gel pieces were rehydrated with 12 ng/µL trypsin in 25 mM NH4HCO3 (pH 8.5) containing 1% CaCl2. After overnight proteolysis at 37°C, digests were extracted first with 100% HCOOH, then with 56% CH3CN/1% HCOOH, and finally with 100% CH3CN. The resulting pools were dried completely under vacuum and stored at −20°C until MS analysis.

LC-MS/MS analysis

LC-MS/MS experiments were performed on two equipments: (i) a Esquire 3000 plus ion trap (Bruker Daltonics) equipped with a nanoelectrospray online ion source, and coupled to a UltiMate-Switchos-Famos LC system (Dionex-LC Packings), and (ii) a LTQ-Orbitrap XL hybrid mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher) coupled to a UltiMate 3000 LC system (Dionex-LC Packings). Peptide mixtures (0.5–5 pmol) were loaded and desalted online in a reverse phase precolumn (C18 Pepmap column, LC Packings), and resolved on a nanoscale C18 Pepmap TM capillary column (LC Packings) at a flow rate of 0.2–0.3 µL/min with a gradient of CH3CN/0.1% formic acid prior injection in the ion trap mass spectrometer. Peptides were separated using a 90 min-gradient from 5 to 95% solvent B (0.1% HCOOH/80% CH3CN). Solvent A was 0.1% HCOOH/5% CH3CN for the Esquire nanoLC system, and 0.1% HCOOH/0% CH3CN for the LTQ-orbitrap nanoLC system. The full-scan mass spectra were measured from m/z 50 to 2000 with the Esquire ion trap mass spectrometer, and m/z 300 to 1700 with the LTQ-orbitrap XL mass spectrometer. The latter was operated in the data-dependent mode using the TOP7 strategy. In brief, a scan cycle was initiated with a full scan of high mass accuracy in the orbitrap, which was followed by MS/MS scans in the linear ion trap on the 7 most abundant precursor ions with dynamic exclusion of previously selected ions. A total of 326 and 40 samples were analyzed on the mass spectrometers, resulting in 163,779 and 100,472 MS/MS spectra recorded, respectively.

Polypeptide database MS/MS search

Using the MASCOT search engine (Matrix Science), we searched all MS/MS spectra against home made polypeptide sequence database. Searches for trypsic peptides were performed with the following parameters: full-trypsin specificity, a mass tolerance of 5 ppm on the parent ion and 0.5 Da on the MS/MS (LTQ-orbitrap mass spectra) or 0.4 Da for the parent ion and 0.5 Da for the MS/MS (Esquire ion trap mass spectra), static modifications of carboxyamidomethylated Cys (+57.0215), and dynamic modifications of oxidized Met (+15.9949). The maximum number of missed cleavage was set at 1. All peptide matches with a Peptide Score of at least 31 (average threshold for p<0.007 with the final database search using the Esquire ion trap data) and rank 1 were filtered by the IRMa 1.16.0 software (J. Garin&C. Bruley, CEA, DSV, iRTSV, Grenoble). The criteria adopted for protein identification were very conservative with either 1) that at least two peptides with ion score 31 or higher match or 2) that at least one peptide with ion score 50 (average threshold for p<0.0001) or higher matches. A False-Positive rate of 0.2% was estimated using the corresponding decoy database. Further data analysis was performed for semi-trypsin specificity (p<0.001). Spectral count (number of spectra recorded per protein) was performed on the whole set of MS/MS spectra recorded over the entire study. Proteins were then evaluated for their respective abundance after molecular weight normalization.

Kinetics of DNA repair after gamma-irradiation or desiccation-rehydration

For gamma irradiation, cells were grown at 30°C in TSB/10 to an OD600 of 0.5, concentrated to an OD600 of 25, and irradiated on ice to 6,800 Gy at 56.6 Gy/min dose rate (137Cs source). After irradiation, cultures were diluted to an OD600 of 0.2 and incubated at 30°C. At different post-irradiation incubation times, 5 ml aliquots were removed to prepare agarose plugs as described by Harris et al. [14]. The DNA in the plugs was digested with PmeI and SwaI restriction enzymes, and then subjected to pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for 24 h at 12°C using a CHEF MAPPER electrophoresis system (Biorad) with the following conditions: 6.0 V/cm, linear pulse ramp of 60–120 s, and a switching angle of 120° (−60° to +60°). For desiccation, stationary phase cells were concentrated to an OD600 of 20 and placed on sterile glass slides (100 µl cells per slide), dried and stored at room temperature in a sealed desiccator over anhydrous CaSO4. The CaSO4 desiccant is impregnated with CoCl2. This latter chemical compound is a visual moisture indicator: anhydrous CoCl2 is blue while pink in presence of water. After 27 days of desiccation, cells from 5 glass slides were resuspended in 50 ml TSB/10, incubated at 30°C and 5 ml aliquots were taken at different times and treated as described above.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR

For analysis of gene expression after UV exposure, samples from the same exponential phase culture (OD600 0.2–0.4) were exposed to either 0 or 250 J.m−2 of UV-C (4 mL volumes in Petri dishes), and then further incubated. Samples for RNA isolation were taken after 30 min. Cells were treated with RNAprotect Bacteria Reagent (Qiagen) prior to RNA isolation using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA samples were treated twice with DNase. For RT-PCR, cDNA was synthesized in 20 µL reactions using 1 µg of RNA and the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche). DNA fragments of 150–250 bp were then amplified in 25 µL reactions using 1 µL of cDNA from the first step, Taq polymerase (Sigma) and gene-specific primers (Table S12). These amplifications were carried out by incubating reactions at 94°C for 10 min prior to 30 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 30 sec at 56°C and 30 sec at 72°C, followed by a final step at 72°C for 2 min, with modifications for tuf (25 cycles), recA-P3 and dnaE2 (both 35 cycles). Controls for DNA contamination were performed with reactions lacking reverse transcriptase.

Supporting Information

Evidence for correct annotation of Deide_15980. Deide_15980 proteogenomic annotation with four peptides detected by mass spectrometry (A). Multiple sequence alignments of Deide_15980 and homologs found encoded in the reverse orientation of DR_0869 and Dgeo_0511 (B). Multiple sequence alignments of incorrectly predicted DR_0869 and Dgeo_0511 with a protein found when the orientation of Deide_15980 is reversed (C). Identified peptides for Deide_15980 are indicated with black and blue bars in (A). The peptide sequences can be found in Table S3.

(0.07 MB PDF)

Evidence for correct annotation of ddrC in Deinococcus species. Schematic representation of the ddrC loci and flanking genes in D. deserti, D. radiodurans and D. geothermalis (A). Multi-alignment of polypeptide sequences for correct DdrC proteins (B) and wrongly annotated DdrC proteins (Panel C). In Panel A, the predicted genes are labeled with the locus tag number. DR_0003 and Dgeo_0047 are incorrectly predicted, and their orientation has to be reversed. Correct ddrC genes are shown in black arrows, wrong ddrC ORFs in open arrows. The black boxes upstream the correct ddrC genes indicate the radiation response motif. Flanking genes Deide_23270 and Dgeo_0048 are homologs.

(0.05 MB PDF)

Specific RT-PCR showing transcription of correct ddrC (Deide_23280). Genome region of Deide_23280 (A). Deide_23280 is present on the reverse DNA strand. The opposite DNA strand could encode a protein related to DR_0003 and Dgeo_0047 (indicated by the blue ellipse). Green and red bar indicate start and stop codons, respectively. Black bar indicates the radiation/desiccation response motif upstream Deide_23280. RV and FW indicate schematically the orientation of the primers used in the RT-PCR. Specific two-step RT-PCR (B). Either purified primer FW (Dd23280FW) or RV (Dd23280RV) was used to synthesize cDNA in the RT reaction (first step). The PCR in the second step was performed with both primers. When Deide_23280 is the correctly predicted gene, cDNA synthesis and thus an RT-PCR product is expected with primer RV in the RT reaction. RNA was isolated 30 min after the cells were irradiated (+) or not (−) with UV (250 J/m2). N and P indicated negative (no template) and positive (genomic DNA) control, respectively.

(0.11 MB PDF)

Evidence for correct annotation of ddrH. Multi-alignment of correct DdrH protein sequences (A) and wrongly annotated DdrH protein sequences (B). The D. radiodurans protein highly homologous to Deide_20641 and Dgeo_0322 is found when the orientation of DR_0438 (ddrH) is reversed.

(0.03 MB PDF)

Genome dot plots for the chromosomes of sequenced Deinococcus species. Genome dot plots for the chromosome of D. deserti (horizontal axis) vs. D. geothermalis (vertical axis) (A) and vs. D. radiodurans (vertical axis) (B). Each dot represents the location of a pair of Bidirectional Best Hits (with a minimum of 30% identity and 70% coverage) between the two chromosomes.

(0.22 MB PDF)

Insertion sequences identified in the genome of D. deserti and comparison with other Deinococcus/Thermus species.

(0.09 MB PDF)

Proteins identified by LC-MS/MS shotgun.

(0.26 MB XLS)

Peptides identified by LC-MS/MS shotgun.

(2.67 MB XLS)

Homology between the DNA molecules of D. deserti, D. radiodurans and D. geothermalis.

(0.07 MB PDF)

Deinococcus-specific proteins.

(0.16 MB PDF)

Mn/Fe ratio in D. deserti and D. radiodurans.

(0.08 MB PDF)

Mn- and Fe- transport and regulation related systems in D. deserti.

(0.08 MB PDF)

Stress response-related proteins in D. deserti, D. radiodurans and D. geothermalis.

(0.16 MB PDF)

ABC-transporters identified in D. deserti.

(0.15 MB PDF)

DNA repair genes in D. deserti, D. radiodurans and D. geothermalis.

(0.20 MB PDF)

Radiation/desiccation response motif identified in D. deserti.

(0.11 MB PDF)

Primers for RT-PCR.

(0.06 MB PDF)

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Jérôme Garin and Christophe Bruley (IRMa software and discussions), the Institut Curie (137Cs irradiation facilities), Ashlee Earl (for communicating methodological details), as well as Sylvain Fochesato (RT-PCR), Paul Soreau (ICP analysis), Charles Marchetti (fermentor facilities), and V. Favaudon (γ-irradiation) for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Work in our laboratories is supported by the Commissariat à l'Energie Atomique (CEA LRC42V for SS), the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-07-BLAN-0106-02). SS is further supported by the University Paris-Sud XI and Electricité de France. EJ gratefully acknowledges the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique for its support in this work (CNRS post-doctoral fellowship N°1002121). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. This work was carried out in compliance with the current laws governing genetic experimentation in France.

References

- 1.Chanal A, Chapon V, Benzerara K, Barakat M, Christen R, et al. The desert of Tataouine: an extreme environment that hosts a wide diversity of microorganisms and radiotolerant bacteria. Environ Microbiol. 2006;8:514–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rainey FA, Ray K, Ferreira M, Gatz BZ, Nobre MF, et al. Extensive diversity of ionizing-radiation-resistant bacteria recovered from Sonoran Desert soil and description of nine new species of the genus Deinococcus obtained from a single soil sample. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:5225–5235. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.9.5225-5235.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Groot A, Chapon V, Servant P, Christen R, Fischer-Le Saux M, et al. Deinococcus deserti sp. nov., a gamma-radiation-tolerant bacterium isolated from the Sahara Desert. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55:2441–2446. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63717-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blasius M, Hubscher U, Sommer S. Deinococcus radiodurans: what belongs to the survival kit? Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;43:221–238. doi: 10.1080/10409230802122274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson AW, Nordan HC, Cain RF, Parrish G, Duggan D. Studies on a radio-resistant micrococcus. I. Isolation, morphology, cultural characteristics, and resistance to gamma radiation. Food Technol. 1956;10:575–578. [Google Scholar]

- 6.White O, Eisen JA, Heidelberg JF, Hickey EK, Peterson JD, et al. Genome sequence of the radioresistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans R1. Science. 1999;286:1571–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5444.1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferreira AC, Nobre MF, Rainey FA, Silva MT, Wait R, et al. Deinococcus geothermalis sp. nov. and Deinococcus murrayi sp. nov., two extremely radiation-resistant and slightly thermophilic species from hot springs. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:939–947. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-4-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makarova KS, Omelchenko MV, Gaidamakova EK, Matrosova VY, Vasilenko A, et al. Deinococcus geothermalis: the pool of extreme radiation resistance genes shrinks. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e955. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000955. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Potts M. Desiccation tolerance: a simple process? Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:553–559. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02231-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mattimore V, Battista JR. Radioresistance of Deinococcus radiodurans: functions necessary to survive ionizing radiation are also necessary to survive prolonged desiccation. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:633–637. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.633-637.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanaka M, Earl AM, Howell HA, Park MJ, Eisen JA, et al. Analysis of Deinococcus radiodurans's transcriptional response to ionizing radiation and desiccation reveals novel proteins that contribute to extreme radioresistance. Genetics. 2004;168:21–33. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.029249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox MM, Battista JR. Deinococcus radiodurans—the consummate survivor. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:882–892. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zahradka K, Slade D, Bailone A, Sommer S, Averbeck D, et al. Reassembly of shattered chromosomes in Deinococcus radiodurans. Nature. 2006;443:569–573. doi: 10.1038/nature05160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris DR, Tanaka M, Saveliev SV, Jolivet E, Earl AM, et al. Preserving genome integrity: the DdrA protein of Deinococcus radiodurans R1. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020304. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Narumi I, Satoh K, Cui S, Funayama T, Kitayama S, et al. PprA: a novel protein from Deinococcus radiodurans that stimulates DNA ligation. Mol Microbiol. 2004;54:278–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daly MJ, Gaidamakova EK, Matrosova VY, Vasilenko A, Zhai M, et al. Protein oxidation implicated as the primary determinant of bacterial radioresistance. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e92. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050092. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Battista JR, Park MJ, McLemore AE. Inactivation of two homologues of proteins presumed to be involved in the desiccation tolerance of plants sensitizes Deinococcus radiodurans R1 to desiccation. Cryobiology. 2001;43:133–139. doi: 10.1006/cryo.2001.2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Makarova KS, Aravind L, Wolf YI, Tatusov RL, Minton KW, et al. Genome of the extremely radiation-resistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans viewed from the perspective of comparative genomics. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2001;65:44–79. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.1.44-79.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ansong C, Purvine SO, Adkins JN, Lipton MS, Smith RD. Proteogenomics: needs and roles to be filled by proteomics in genome annotation. Brief Funct Genomic Proteomic. 2008;7:50–62. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/eln010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallien S, Perrodou E, Carapito C, Deshayes C, Reyrat JM, et al. Ortho-proteogenomics: multiple proteomes investigation through orthology and a new MS-based protocol. Genome Res. 2009;19:128–135. doi: 10.1101/gr.081901.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta N, Benhamida J, Bhargava V, Goodman D, Kain E, et al. Comparative proteogenomics: combining mass spectrometry and comparative genomics to analyze multiple genomes. Genome Res. 2008;18:1133–1142. doi: 10.1101/gr.074344.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dandekar T, Huynen M, Regula JT, Ueberle B, Zimmermann CU, et al. Re-annotating the Mycoplasma pneumoniae genome sequence: adding value, function and reading frames. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:3278–3288. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.17.3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolker E, Picone AF, Galperin MY, Romine MF, Higdon R, et al. Global profiling of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1: expression of hypothetical genes and improved functional annotations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:2099–2104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409111102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaffe JD, Stange-Thomann N, Smith C, DeCaprio D, Fisher S, et al. The complete genome and proteome of Mycoplasma mobile. Genome Res. 2004;14:1447–1461. doi: 10.1101/gr.2674004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mockler TC, Chan S, Sundaresan A, Chen H, Jacobsen SE, et al. Applications of DNA tiling arrays for whole-genome analysis. Genomics. 2005;85:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shirkey B, McMaster NJ, Smith SC, Wright DJ, Rodriguez H, et al. Genomic DNA of Nostoc commune (Cyanobacteria) becomes covalently modified during long-term (decades) desiccation but is protected from oxidative damage and degradation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2995–3005. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein C, Aivaliotis M, Olsen JV, Falb M, Besir H, et al. The low molecular weight proteome of Halobacterium salinarum. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:1510–1518. doi: 10.1021/pr060634q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schiex T, Gouzy J, Moisan A, de Oliveira Y. FrameD: a flexible program for quality check and gene prediction in prokaryotic genomes and noisy matured eukaryotic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3738–3741. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu H, Hu GQ, Yang YF, Wang J, She ZS. MED: a new non-supervised gene prediction algorithm for bacterial and archaeal genomes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:97. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Earl AM, Mohundro MM, Mian IS, Battista JR. The IrrE protein of Deinococcus radiodurans R1 is a novel regulator of recA expression. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:6216–6224. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.22.6216-6224.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hua Y, Narumi I, Gao G, Tian B, Satoh K, et al. PprI: a general switch responsible for extreme radioresistance of Deinococcus radiodurans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;306:354–360. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00965-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daly MJ, Gaidamakova EK, Matrosova VY, Vasilenko A, Zhai M, et al. Accumulation of Mn(II) in Deinococcus radiodurans facilitates gamma-radiation resistance. Science. 2004;306:1025–1028. doi: 10.1126/science.1103185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norioka N, Hsu MY, Inouye S, Inouye M. Two recA genes in Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4179–4182. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4179-4182.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nahrstedt H, Schroder C, Meinhardt F. Evidence for two recA genes mediating DNA repair in Bacillus megaterium. Microbiology. 2005;151:775–787. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27626-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swingley WD, Chen M, Cheung PC, Conrad AL, Dejesa LC, et al. Niche adaptation and genome expansion in the chlorophyll d-producing cyanobacterium Acaryochloris marina. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2005–2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709772105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vujicic-Zagar A, Dulermo R, Le Gorrec M, Vannier F, Servant P, et al. Crystal structure of the IrrE protein, a central regulator of DNA damage repair in Deinococcaceae. J Mol Biol. 2009;386:704–716. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.12.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu H, Sadygov RG, Yates JR., III A model for random sampling and estimation of relative protein abundance in shotgun proteomics. Anal Chem. 2004;76:4193–4201. doi: 10.1021/ac0498563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mueller LN, Brusniak MY, Mani DR, Aebersold R. An assessment of software solutions for the analysis of mass spectrometry based quantitative proteomics data. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:51–61. doi: 10.1021/pr700758r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zimmerman JM, Battista JR. A ring-like nucleoid is not necessary for radioresistance in the Deinococcaceae. BMC Microbiol. 2005;5:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Udupa KS, O'Cain PA, Mattimore V, Battista JR. Novel ionizing radiation-sensitive mutants of Deinococcus radiodurans. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7439–7446. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.24.7439-7446.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Snider J, Houry WA. MoxR AAA+ ATPases: a novel family of molecular chaperones? J Struct Biol. 2006;156:200–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sommer S, Boudsocq F, Devoret R, Bailone A. Specific RecA amino acid changes affect RecA-UmuD'C interaction. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:281–291. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sutton MD, Smith BT, Godoy VG, Walker GC. The SOS response: recent insights into umuDC-dependent mutagenesis and DNA damage tolerance. Annu Rev Genet. 2000;34:479–497. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Erill I, Campoy S, Mazon G, Barbe J. Dispersal and regulation of an adaptive mutagenesis cassette in the bacteria domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:66–77. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boshoff HI, Reed MB, Barry CE, III, Mizrahi V. DnaE2 polymerase contributes to in vivo survival and the emergence of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell. 2003;113:183–193. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00270-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Galhardo RS, Rocha RP, Marques MV, Menck CF. An SOS-regulated operon involved in damage-inducible mutagenesis in Caulobacter crescentus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:2603–2614. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koorits L, Tegova R, Tark M, Tarassova K, Tover A, et al. Study of involvement of ImuB and DnaE2 in stationary-phase mutagenesis in Pseudomonas putida. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6:863–868. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nohmi T. Environmental stress and lesion-bypass DNA polymerases. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2006;60:231–253. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vallenet D, Nordmann P, Barbe V, Poirel L, Mangenot S, et al. Comparative analysis of Acinetobacters: three genomes for three lifestyles. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001805. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Griffiths-Jones S, Moxon S, Marshall M, Khanna A, Eddy SR, et al. Rfam: annotating non-coding RNAs in complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D121–124. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Achaz G, Boyer F, Rocha EP, Viari A, Coissac E. Repseek, a tool to retrieve approximate repeats from large DNA sequences. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:119–121. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Evidence for correct annotation of Deide_15980. Deide_15980 proteogenomic annotation with four peptides detected by mass spectrometry (A). Multiple sequence alignments of Deide_15980 and homologs found encoded in the reverse orientation of DR_0869 and Dgeo_0511 (B). Multiple sequence alignments of incorrectly predicted DR_0869 and Dgeo_0511 with a protein found when the orientation of Deide_15980 is reversed (C). Identified peptides for Deide_15980 are indicated with black and blue bars in (A). The peptide sequences can be found in Table S3.

(0.07 MB PDF)

Evidence for correct annotation of ddrC in Deinococcus species. Schematic representation of the ddrC loci and flanking genes in D. deserti, D. radiodurans and D. geothermalis (A). Multi-alignment of polypeptide sequences for correct DdrC proteins (B) and wrongly annotated DdrC proteins (Panel C). In Panel A, the predicted genes are labeled with the locus tag number. DR_0003 and Dgeo_0047 are incorrectly predicted, and their orientation has to be reversed. Correct ddrC genes are shown in black arrows, wrong ddrC ORFs in open arrows. The black boxes upstream the correct ddrC genes indicate the radiation response motif. Flanking genes Deide_23270 and Dgeo_0048 are homologs.

(0.05 MB PDF)

Specific RT-PCR showing transcription of correct ddrC (Deide_23280). Genome region of Deide_23280 (A). Deide_23280 is present on the reverse DNA strand. The opposite DNA strand could encode a protein related to DR_0003 and Dgeo_0047 (indicated by the blue ellipse). Green and red bar indicate start and stop codons, respectively. Black bar indicates the radiation/desiccation response motif upstream Deide_23280. RV and FW indicate schematically the orientation of the primers used in the RT-PCR. Specific two-step RT-PCR (B). Either purified primer FW (Dd23280FW) or RV (Dd23280RV) was used to synthesize cDNA in the RT reaction (first step). The PCR in the second step was performed with both primers. When Deide_23280 is the correctly predicted gene, cDNA synthesis and thus an RT-PCR product is expected with primer RV in the RT reaction. RNA was isolated 30 min after the cells were irradiated (+) or not (−) with UV (250 J/m2). N and P indicated negative (no template) and positive (genomic DNA) control, respectively.

(0.11 MB PDF)

Evidence for correct annotation of ddrH. Multi-alignment of correct DdrH protein sequences (A) and wrongly annotated DdrH protein sequences (B). The D. radiodurans protein highly homologous to Deide_20641 and Dgeo_0322 is found when the orientation of DR_0438 (ddrH) is reversed.

(0.03 MB PDF)

Genome dot plots for the chromosomes of sequenced Deinococcus species. Genome dot plots for the chromosome of D. deserti (horizontal axis) vs. D. geothermalis (vertical axis) (A) and vs. D. radiodurans (vertical axis) (B). Each dot represents the location of a pair of Bidirectional Best Hits (with a minimum of 30% identity and 70% coverage) between the two chromosomes.

(0.22 MB PDF)

Insertion sequences identified in the genome of D. deserti and comparison with other Deinococcus/Thermus species.

(0.09 MB PDF)

Proteins identified by LC-MS/MS shotgun.

(0.26 MB XLS)

Peptides identified by LC-MS/MS shotgun.

(2.67 MB XLS)

Homology between the DNA molecules of D. deserti, D. radiodurans and D. geothermalis.

(0.07 MB PDF)

Deinococcus-specific proteins.

(0.16 MB PDF)

Mn/Fe ratio in D. deserti and D. radiodurans.

(0.08 MB PDF)