Abstract

Uterine leiomyomas, benign uterine smooth muscle tumors that affect 30% of reproductive-aged women, are a significant health concern. The initiation event for these tumors is unclear, but 17β-estradiol (E2) is an established promoter of leiomyoma growth. E2 not only alters transcription of E2-regulated genes but also can rapidly activate signaling pathways. The aim of our study is to investigate the role of rapid E2-activated cytoplasmic signaling events in the promotion of leiomyomas. Western blot analysis revealed that E2 rapidly increases levels of phosphorylated protein kinase Cα (PKCα) in both immortalized uterine smooth muscle (UtSM) and leiomyoma (UtLM) cell lines, but increases levels of phosphorylated ERK1/2 only in UtLM cells. Our studies demonstrate a paradoxical effect of molecular and pharmacological inhibition of PKCα on ERK1/2 activation and cellular proliferation in UtLM and UtSM cells. PKCα inhibition decreases levels of phosphorylated ERK1/2 and proliferation in UtLM cells but raises these levels in UtSM cells. cAMP-PKA signaling is rapidly activated only in UtSM cells with E2 and inhibits ERK1/2 activation and proliferation. We therefore propose a model whereby E2’s rapid activation of PKCα and cAMP-PKA signaling plays a central role in the maintenance of a low proliferative index in normal uterine smooth muscle via its inhibition of the MAPK cascade and these pathways are altered in leiomyomas to promote MAPK activation and proliferation. These studies demonstrate that rapid E2-signaling pathways contribute to the promotion of leiomyomas.

Estradiol-17β initiates rapid signaling events that promote the growth of uterine leiomyoma cells but inhibits the growth of normal uterine smooth muscle cells.

Uterine leiomyomas, or fibroids, are benign uterine smooth muscle tumors and are a significant women’s health issue due to their high incidence and morbidity. Whereas one third of all premenopausal women are symptomatic for uterine leiomyomas, it is suspected that up to 80% of women develop these tumors (1,2). Uterine leiomyomas can lead to abnormal bleeding, pregnancy complications, and infertility and are a leading cause of hysterectomies (3).

Although predisposing factors for the development of uterine leiomyomas exist and include ethnicity (2,4), early use of oral contraceptives (5,6), prenatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol (7,8,9,10), and obesity (11), the initiation event for these tumors is unclear and may be due to genetic or epigenetic alterations (12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19). It is clear, however, that enhanced proliferation is a primary factor in uterine leiomyoma tumor growth (20,21). Moreover, it is generally accepted that estrogens are an important driving force behind this increased proliferation (22,23,24). Evidence for the dependence of leiomyomas on the steroid hormone 17β-estradiol (E2) include: 1) the onset of leiomyomas only after puberty; 2) the regression of leiomyoma tumors with a reduction in circulating E2 levels as a result of menopause or treatment with GnRH agonists (25); 3) the decrease in E2-induced proliferation of leiomyomas with estrogen receptor (ER) antagonists, including selective ER modulators (23,26,27); and 4) the inhibition of leiomyoma growth in mice with inactive or down-regulated ERs (28,29). The role of progesterone in leiomyoma growth is less clear. Progesterone has been shown to up-regulate Bcl-2, an antiapoptotic factor, in leiomyoma cells (30) but can also lower factor signaling (31) to reduce E2-stimulated leiomyoma growth. A reduced proliferative signaling with progesterone may help account for the protective effect that pregnancy can have on leiomyoma expansion (32).

Uterine leiomyomas arise from the smooth muscle layer of the uterus, which is normally quiescent. In early gestation, the smooth muscle cells of the uterus demonstrate a dramatic increase in proliferation in response to the hormonal cues such as increasing levels of E2 and human chorionic gonadotropin (33). A question of interest that has not yet been investigated is what prevents normal uterine smooth muscle cells from proliferating in the face of similar hormonal cues (i.e. estrogens) in the nonpregnant state? Also, can these processes provide clues as to what is altered in leiomyomas?

Estrogens may exert effects on normal uterine smooth muscle and leiomyoma cells through several mechanisms. In addition to altering transcription of E2-regulated genes, E2 can rapidly initiate cytoplasmic signaling pathways in a variety of cell types. As reviewed by many authors, various signaling molecules, including protein kinases and G protein-coupled receptors, can be activated by E2 within minutes, depending on the cellular context (34,35,36,37,38,39,40). The rapid activation of these signaling cascades ultimately converge at the nucleus to affect gene transcription (41,42,43,44).

Genetic studies of uterine leiomyomas have not discovered key altered genes and expression of E2-regulated genes such as c-myc, cyclin D1, and pS2 is not as high as expected for a disease that is driven by E2 (45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52). As demonstrated in breast cancer cells, high levels of rapid E2 signaling may exist, even without a robust genomic estrogenic response in classic E2-responsive genes (53). Several studies suggest that growth factor signaling is important to leiomyoma growth (50,54,55,56,57). Rapid E2 and growth factor signaling can converge because both E2 and growth factors can trigger multiple pathways, including MAPK, to promote cell cycle progression in several cell types (58,59). Moreover, rapid E2 signaling and growth factor signaling cross talk has been reported in E2-dependent breast cancer and can act synergistically to stimulate cell proliferation (60). To date, there is no detailed knowledge of how rapid E2 signaling may be contributing to leiomyoma growth.

In this study, we investigated the contribution of rapid E2 signaling events to both the proliferation of leiomyoma cells and the maintenance of low levels of proliferation in normal uterine smooth muscle cells. Our results demonstrate that E2 activates multiple signaling pathways in these cell types that converge on MAPK to modulate the cells proliferative response to E2. We report that cAMP-protein kinase A (PKA) signaling is initiated by E2 and has an inhibitory effect on MAPK signaling and proliferation in the normal uterine smooth muscle but that this pathway is absent in the leiomyoma cells. Moreover, E2’s elevation of phospho-protein kinase C (PKC)-α levels and PKCα’s paradoxical effects on ERK1/2 activation play a pivotal role in the pathological growth of uterine leiomyoma cells and in the repression of proliferation in normal uterine smooth muscle cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Uterine leiomyoma (UtLM-ht) and normal uterine smooth muscle (UtSM-ht) cell lines, immortalized via retroviral transfection (PLX1N vector; CLONTECH, Palo Alto, CA) of human telomerase, were graciously donated by Darlene Dixon (National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; Research Triangle Park, NC). Cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen Life Technologies; Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 1% essential and nonessential amino acids, 1% sodium pyruvate, and 0.14% geneticin (30 mg/ml).at 37 C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

In vivo xenograft studies

Twenty ovariectomized female nude mice (ν/ν) mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories, Inc. (Wilmington, MA). Ten mice were sc injected with 10 × 106 UtLM-ht cells and ten were sc injected with 5 × 106 UtSM-ht cells in each dorsal flank. Five of the UtLM-ht and UtSM-ht injected mice were given E2 pellets (0.72 mg per 60 d release; Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL), and the other five were given blank pellets. Tumors were measured biweekly and animals were killed at d 25. Tumor volume and weight was then measured.

All procedures involving these animals were conducted in compliance with state and federal laws, standards of the United States Department of Health and Human Services and guidelines established by Tulane University Animal Care and Use Committee. The facilities and laboratory animals program of Tulane University are accredited by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from treated cells using an RNAeasy mini kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA (2 μg) was reversed transcribed using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Aliquot of 10× diluted cDNA, iQ SYBR Green (Bio-Rad), and specific primers were amplified using a Bio-Rad iCycler iQ real-time PCR detection system. Primers were designed using Beacon Designer 2 software (Palo Alto, CA) and ordered through Invitrogen primer division. Primers were: progesterone receptor (TACCCGCCCTATCTCAACTACC) and β-actin (TGAGCGCGGCTACAGCTT). PCR parameters were denature at 95 C for 3 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 C for 20 sec and annealing/extension at 60 C for 1 min. Melt curves were generated to confirm each primer and data were analyzed by δ-quantitative comparative threshold value method as determined by the iCycler software system.

Western blot analysis

Briefly, cells were washed and phenol-free DMEM containing 5% charcoal-stripped FBS was added to the cells 72 h before treatment. Cells were then pretreated with 0.1% ethanol, 1 μm ICI 182, 780 (Tocris, Ellisville, MO), 5 μm H-89, 10–100 nm Ro 31,8220 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), or 100 pm-15 nm bisindolymaleimide × hydrochloride (Bis10) (Sigma) and then treated with 1 nm E2 (Sigma; St. Louis, MO) for 5 min. Dosage ranges for the inhibitors were calculated based on specificity to PKCα and PKA and toxicity. Cells were immediately lysed and protein was resolved by SDS-PAGE on a 4–12% gradient gel. Protein was transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and the membranes were incubated with specific antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA) at 4 C. Membranes were then incubated first with antirabbit IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase and then with a chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL) to detect antibody-antigen complexes. Densitometry of the bands was used for quantification, and results of at least three experiments were combined for statistical analysis.

Transfection of constitutive-active and dominant-negative PKCα

Plasmid DNA, graciously donated by Barbara Beckman (Tulane University, New Orleans, LA), was introduced to cells maintained for 72 h in phenol-free DMEM containing 5% charcoal-stripped FBS by nucleofection (AmaxaBiosystems, Gaithersburg, MD; primary smooth muscle kit). Transfected cells were allowed to adhere overnight in six-well plates and then treated and harvested as described above for Western blot analysis. Experiments were repeated three times.

Proliferation assays

Cells were changed to phenol-free DMEM containing 5% charcoal-stripped FBS 72 h before plating. Then 2 × 103 cells/well were seeded onto 48-well plates, and 18 h after plating, medium was changed to phenol-free DMEM containing 5% charcoal-stripped FBS and one of the following treatments: 0.1% ethanol, 1–10 nm E2 (Sigma), 1 μm ICI 182, 780 (Tocris), 50 nm Ro 31, 8220 (Sigma), 50 μm 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX; Sigma), 100 μm 8-bromoadenosine-3′,5′cyclic monophosphate (8brcAMP; Sigma), or 100 pm Bis 10 (Sigma). Cells were maintained in treatment medium until proliferation was measured using the CellTiter 96 AQueous nonradioactive cell proliferation assay kit [Promega, Madison, WI; 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt (MTS) assay]. Absorbance of the formazan product was measured on a FL600 microplate reader (Bio-Tek, Winsookie, VT). Experiments were repeated at least three times.

cAMP assays

cAMP levels with vehicle, E2 (Sigma), or 100 nm Ro 31,8220 (Sigma) were assessed with the use of a cAMP competitive EIA kit (Zymed Laboratories, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Briefly, cell media were changed to 5% charcoal-stripped FBS 72 h before treatment. Cells were then treated for the specific time increments. Cells were washed with PBS and flooded with 5% trichloroacetic acid, followed by a water wash. Supernatants were then incubated with enzyme-labeled cAMP and antibody. The reaction was then stopped and absorbance read using a Bio-Tek FL 600 microplate reader at 410 nm. cAMP concentration was calculated using a standard curve. Assay was completed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

Prism 3.0 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) was used to conduct a one-way ANOVA with Tukey posttest for the data sets. Confidence interval was set at 95%.

Results

Genomic signaling and proliferative response in leiomyoma cells with E2 treatment

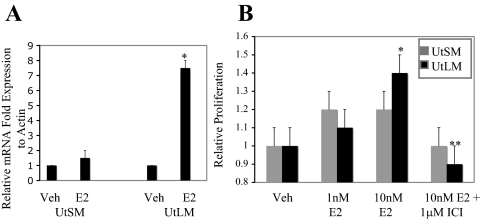

RT-PCR of progesterone receptor expression, an E2-responsive gene, demonstrates that genomic E2 signaling is intact in both UtSM-ht and UtLM-ht cells but is higher in the UtLM-ht cells (Fig. 1A). This is in agreement with studies that demonstrate that leiomyomas have a greater transcriptional response to E2 compared with the adjacent myometrium (61).

Figure 1.

Normal UtSM-ht and UtLM-ht cell genomic and proliferative response to E2 treatment. A, RT-PCR of UtSM-ht or UtLM-ht cells with 18 h EtOH (Veh; vehicle) or 1 nm E2 treatment. UtSM-ht: P > 0.05; UtLM-ht: progesterone receptor expression with E2 treatment was significantly greater than vehicle-treated cells (*, P < 0.05). B, Proliferation was measured in UtLM-ht and UtSM-ht cells by MTS assay on d 5 with vehicle (control), 1 nm E2, 10 nm E2, or 10 nm E2 + 1 μm ICI 182, 780. UtSM-ht, P > 0.05; UtLM-ht: cells treated with 10 nm E2 had significantly greater proliferation than vehicle-treated cells (*, P < 0.05). Cells treated with E2 and ICI 182, 780 had significantly reduced levels of proliferation compared with cells treated with E2 alone (**, P < 0.05).

A hallmark of leiomyoma cells is their increased sensitivity to the mitogenic effects of E2 (27). Initially, an increased proliferative index with E2 treatment was established for the immortalized leiomyoma (UtLM-ht) cell line compared with the normal uterine smooth muscle (UtSM-ht) cell line (Fig. 1B). This increase in proliferation is blocked by treatment with ICI 182, 780 (Fig. 1B), thus indicating an ER-dependent process. The statistically significant level of increase in the rate of proliferation in leiomyoma cells treated with E2 is expected for cells of benign, smooth muscle origin. Although studies with animal models have found decreased levels of apoptosis in leiomyoma cells (62), findings from our laboratory are in agreement with others (20,21) that demonstrate higher rates of proliferation, rather than differences in apoptosis, are critical for leiomyoma growth (supplemental data Fig. 1, published as supplemental data on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http:// endo.endojournals.org).

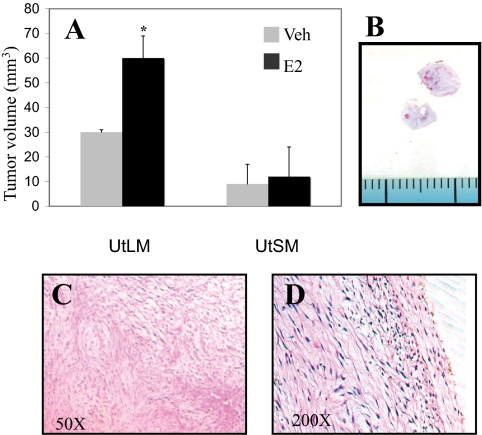

In vivo xenograft studies whereby ovariectomized female nude mice were injected with either UtLM-ht or UtSM-ht cells and given blank or E2 pellets demonstrate that injected UtLM-ht cells form E2-responsive tumors that are larger than those formed by injection of UtSM-ht cells (Fig. 2A). Thus, we conclude that the proliferation rate observed in UtLM-ht cells with E2 is biologically significant.

Figure 2.

UtLM-ht and UtSM-ht xenografts. A, Volume of tumors formed by sc flank injection of UtLM-ht and UtSM-ht cells into nude ovariectomized mice with blank or E2 pellets. UtSM-ht (P > 0.05); UtLM-ht: tumors with E2 pellets had significantly larger tumors than those with blank pellets (*, P < 0.05). B, Cross-section of UtLM-ht tumors. Microscopic pictures of UtLM-ht tumors, magnification, ×50 (C); magnification, ×200 (D). Veh, Vehicle-treated cells.

E2 rapidly activates ERK1/2 in leiomyoma cells but not in normal uterine smooth muscle cells

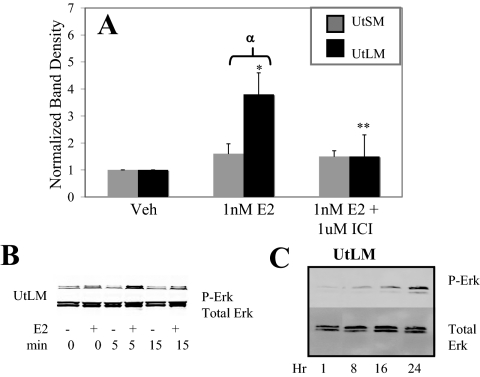

Treatment of uterine leiomyoma cells with 1 nm E2 for 5 min results in a rapid increase in levels of phospho-ERK1/2 (Fig. 3, A and B). Similar results were observed with 0.1 and 10 nm E2 exposure (data not shown). ERK1/2 is the downstream effector of the MAPK cascade, which is typically activated in response to growth factor activation of receptor tyrosine kinases. Pretreatment with the ER antagonist ICI 182, 780 prevents this increase in phospho-ERK1/2 levels, thus demonstrating that E2’s rapid activation of ERK1/2 is an ER-dependent process (Fig. 3A). Treatment with agonists specific for ΕRα and ΕRβ, 1,3,5-Tris(4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-propyl-1H-pyrazole, and 2,3-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-propionitrile, respectively, demonstrates that ERα is the primary contributing isoform to ERK1/2 activation in this cell type (supplemental data Fig. 2). Α rapid increase in ERK1/2 activation with 3 min E2 exposure is first detectable by Western blot analysis at 5 min but diminishes by 15 min (Fig. 3B). A second increase in phosphorylated ERK1/2 levels can be detected 16 h after rapid E2 treatment in leiomyoma cells (Fig. 3C). This second increase suggests that rapid E2 treatment can initiate longer-term MAPK activation that can contribute to proliferation.

Figure 3.

Rapid ERK1/2 phosphorylation in response to E2 treatment in UtLM-ht cells and normal UtSM-ht cells. Western blot analysis (antiphospho-ERK1/2; anti-ERK1/2) of cells treated for 5 min with vehicle (Veh; control), 1 nm E2, or 1 nm E2 with 1 μm ICI 182, 780 pretreatment. Cells were immediately harvested and lysed after treatment. A, Densitometric graph compiled for four blots by normalizing phospho-ERK1/2 (P-Erk) band density to total ERK1/2 band density and then to control. UtLM-ht cells treated with E2 exhibit significantly higher phospho-ERK1/2 levels compared with vehicle-treated cells (*, P < 0.001). UtLM-ht cells treated with E2 and ICI demonstrate significantly reduced levels of phospho-ERK1/2 compared with cells treated with E2 alone (**, P < 0.05). UtLM-ht cells have significantly higher levels of phospho-ERK1/2 than UtSM-ht cells with E2 treatment (α, P < 0.05). B, Representative blot of phospho-ERK1/2 levels in UtLM-ht and UtSM-ht cells treated for 0–15 min with 1 nm E2. C, Representative blot of phospho-ERK1/2 levels in UtLM-ht cells treated with 1 nm E2 for 1–24 h.

However, unlike leiomyoma cells, normal uterine smooth muscle cells treated for 5 min with E2 did not demonstrate increased levels of phospho-ERK1/2 (Fig. 3A). Basal levels of ERK1/2 and PKCα are similar between the two cell lines (supplemental data Fig. 3, A and B).

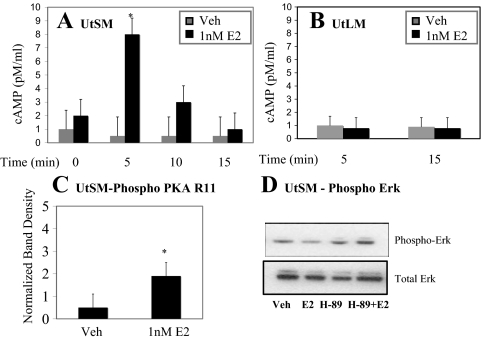

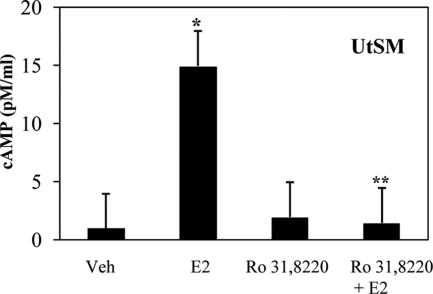

E2 induces cAMP production and increased phospho-PKA levels in normal uterine smooth muscle cells but not leiomyoma cells, and this pathway inhibits ERK1/2 activation and proliferation

Treatment with 1 nm E2 results in a rapid increase in cAMP levels by 5 min in UtSM-ht cells but not UtLM-ht cells (Fig. 4, A and B). Moreover, levels of phospho-PKA also increase with 5 min E2 treatment in UtSM-ht cells (Fig. 4C). Increasing levels of cAMP results in activation of cAMP-dependent PKA, which in turn has been previously shown to interact with MAPK signaling (63,64,65). Inhibition of PKA with the pharmacological inhibitor H-89 results in increased levels of phospho-ERK1/2 in UtSM-ht treated with E2 (Fig. 4D). These data suggest that E2-induced PKA signaling has an inhibitory interaction with the MAPK cascade in UtSM-ht cells and may thus contribute to the low levels of phospho-ERK1/2 observed with E2 in this cell type. PKA has been shown by other laboratories to have an inhibitory effect on Raf activation (63,64,65). Interestingly, this pathway is not induced by E2 in the UtLM-ht cells that have high levels of phospho-ERK1/2 with E2 treatment.

Figure 4.

cAMP-PKA signaling in normal UtSM-ht and UtLM-ht cells. cAMP levels in UtSM-ht (A) and UtLM-ht cells (B) with 0–15 min vehicle (Veh) or E2 treatment. E2-treated UtSM-ht cells have significantly higher levels of cAMP compared with vehicle-treated cells (*, P < 0.05). UtLM-ht, P > 0.05. C, Western blot analysis (anti-PKA RII; anti-β actin) of UtSM-ht cells treated with EtOH (vehicle) or 1 nm E2 for 15 min and immediately harvested and lysed after treatment. Densitometric graph compiled for three blots by normalizing phospho-PKA band density with β-actin band density (*, P < 0.05). D, Representative Western blot analysis (antiphospho-ERK1/2; anti-ERK1/2) of UtSM-ht treated for 5 min EtOH (vehicle), 1 nm E2, or 1 nm E2 with 5 μm H-89 pretreatment.

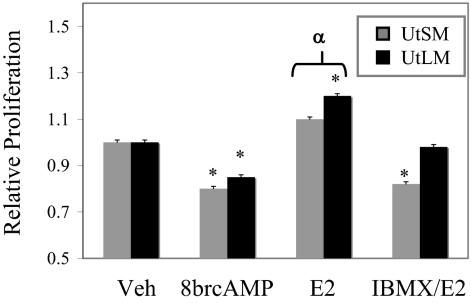

Proliferation studies using the cAMP analog 8brcAMP, an active form of cAMP, demonstrate that cAMP signaling inhibits proliferation in both UtSM-ht and UtLM-ht cells (Fig. 5). Treatment of IBMX stabilizes cAMP from phosphodiesterase action and only UtSM-ht cells demonstrate reduced proliferative rates with IBMX and E2 treatment (Fig. 5). These results suggest that E2 initiates the production of cAMP, which in turn is stabilized by IMBX. This attenuated cAMP signal further inhibits proliferation of UtSM-ht cells with E2. Thus, the results of these experiments demonstrate that E2’s rapid activation of the cAMP-PKA pathway may be important in modulating MAPK activity and proliferation in normal uterine smooth muscle cells and that this pathway is not activated in leiomyoma cells.

Figure 5.

Proliferation in normal UtSM-ht and UtLM-ht cells with cAMP signaling. Proliferation of UtSM-ht and UtLM-ht cells treated with dimethylsulfoxide (Veh; vehicle), 100 μm 8brcAMP, 10 nm E2, or 50 μm IBMX and 1 nm E2 was measured on d 5 by MTS assay. Both UtSM-ht and UtLM-ht cells with 8brcAMP treatment had significantly reduced growth compared with vehicle-treated cells (*, P < 0.001). UtLM-ht cells treated with E2 had significantly greater proliferation than vehicle-treated cells (*, P < 0.001), and rates of proliferation between E2-treated UtSM-ht and UtLM-ht were significantly different (α, P < 0.05). UtSM-ht cells treated with both IBMX and E2 had significantly reduced growth compared with vehicle and E2-treated cells (*, P < 0.05).

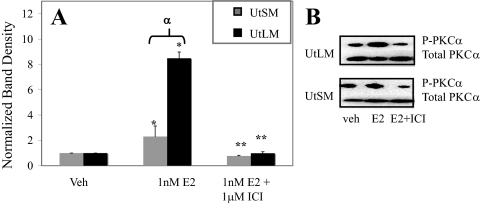

E2 rapidly elevates phospho-PKCα levels in both normal uterine smooth muscle and leiomyoma cells and is dependent on the ER

Western blot analysis revealed that treatment of both UtLM-ht and UtSM-ht cells with E2 for 5 min results in significant increases in levels of phospho-PKCα (Fig. 6, A and B). Pretreatment of both UtSM-ht and UtLM-ht cells with the ER antagonist ICI 182, 780 (1 μm) prevented this increase in phospho-PKCα with E2, thus indicating an ER-dependent process (Fig. 6, A and B). Higher levels of phospho-PKCα are seen in UtLM-ht compared with UtSM-ht cells with E2 treatment (Fig. 6A). Phosphorylation of other PKC isoforms (δ, λ, θ, ζ) was not detected with a 5-min E2 incubation (data not shown). However, the possibility of PKCβ phosphorylation could not be eliminated due to the nature of the antibodies used.

Figure 6.

Rapid PKCα phosphorylation in response to E2 treatment in UtLM-ht and normal UtSM-ht cells. Western blot analysis of cells treated for 5 min with vehicle (Veh; control), 1 nm E2, or 1 nm E2 with 1 μm ICI 182, 780 pretreatment. Cells were immediately harvested and lysed after treatment. A, Densitometric graph compiled for four blots by normalizing phospho-PKCα band density to β-actin. UtLM-ht and UtSM-ht treated with E2 have significantly higher levels of phospho-PKCα than vehicle-treated cells (*, P < 0.001, P < 0.05, respectively). E2- and ICI-treated UtLM-ht and UtSM-ht cells have significantly reduced phospho-PKCα levels compared with cells treated with E2 alone (**, P < 0.001). UtLM-ht cells have significantly higher levels of phospho-PKCα with E2 treatment than UtSM-ht (α, P < 0.001). B, Representative blot of phospho-PKCα levels.

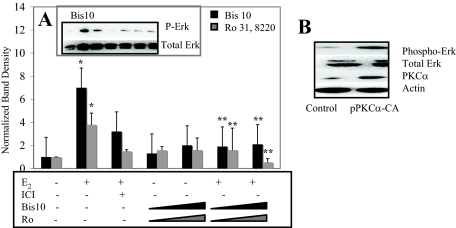

PKCα promotes rapid ERK1/2 activation in leiomyoma cells but inhibits rapid ERK1/2 activation in normal uterine smooth muscle cells

Results from the following experiments demonstrate that PKCα differentially affects levels of ERK1/2 phosphorylation between leiomyoma and normal uterine smooth muscle cells. Our approach was to use a combination of both pharmacological and molecular tools to determine whether PKCα interacts with the MAPK cascade in this cellular system. Bis10 is a potent, selective inhibitor of PKC that inhibits PKC by interacting with its catalytic subunit (66), and Ro 31-8220 is a selective inhibitor of PKC at concentrations less than 1 μm (67). Pharmacological inhibition of PKCα in uterine leiomyoma cells results in a reduction of phospho-ERK1/2 levels with E2 treatment (Fig. 7A). Moreover, transfection of a constitutive-active PKCα resulted in increased levels of phosphorylated ERK1/2 compared with control transfected cells (Fig. 7B), thus confirming a positive relationship between PKCα and ERK1/2 activation that can then be disrupted by inhibitors of PKCα.

Figure 7.

ERK1/2 phosphorylation in UtLM-ht cells with pharmacological inhibition of PKCα and transfection a constitutive-active (CA) PKCα. A, Western blot analysis (antiphospho-ErkRK1/2; anti-ErkRK1/2; anti-PKCα; anti-β-actin) of the following: UtLM-ht cells pretreated with 1 μm ICI 182, 780, 1–100 nm Ro 31,8220, or 100 pm-15 nm Bis10 and then treated for 5 min with 1 nm E2. Cells were immediately harvested and lysed after treatment. Representative blot and densitometric graph compiled by normalizing phospho-ERK1/2 (P-Erk) band density with β-actin (loading control) and then to control. E2-treated cells had significantly increased levels of phospho-ERK1/2 compared with vehicle-treated cells (*, P < 0.05). Cells pretreated with all concentrations of Bis10 and 100 nm Ro 31,8220 and then treated with E2 had significantly reduced phospho-ERK1/2 levels compared with cells treated with E2 alone (**, P < 0.05). B, Representative blot of UtLM-ht cells transfected with either a vector control or pPKCα-CA.

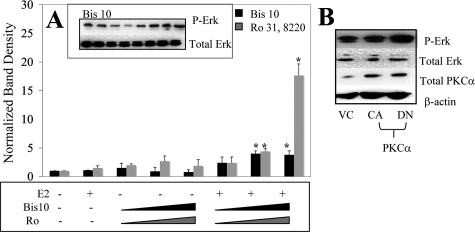

In contrast to leiomyoma cells, pharmacological inhibition of PKCα in normal uterine smooth muscle cells results in increased levels of phospho-ERK1/2 with E2 treatment (Fig. 8A). Transfection of normal uterine smooth muscle cells with a dominant-negative PKCα followed by exposure to E2 led to a rise in phospho-ERK1/2 levels (Fig. 8B). The reduction of active PKCα leading to an increase in phospho-ERK1/2 levels with E2 treatment implies that active PKCα inhibits phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in normal uterine smooth muscle cells.

Figure 8.

ERK1/2 phosphorylation in normal UtSM-ht with pharmacological inhibition of PKCα and transfection of constitutive-active (CA) and dominant-negative (DN) mutants of PKCα. A, Western blot analysis (antiphospho-ERK1/2; anti-ERK1/2; anti-PKCα; anti-β-actin) of the following: UtSM-ht cells pretreated with either 1 μm ICI 182, 780, 1–100 nm Ro 31,8220, or 100 pm-15 nm Bis10 and then treated for 5 min with 1 nm E2. Cells were immediately harvested and lysed after treatment. Representative blot and densitometric graph compiled by normalizing phsopho-ERK1/2 band density to β-actin and then to vehicle control (VC). UtSM-ht cells treated with Bis10 and Ro31,8220 (Ro) and E2 had significantly higher phospho-ERK1/2 (P-Erk) levels compared with vehicle and E2-treated cells (*, P < 0.001). B, Representative blot of UtSM-ht cells transfected with vector control, pPKCα-CA, or pPKCα-DN and treated for 5 min with 1 nm E2.

Pretreatment of normal uterine smooth muscle cells with a pharmacological inhibitor of PKCα followed by rapid E2 treatment results in reduced cAMP levels compared with cells treated with E2 alone (Fig. 9). This reduction in cAMP signaling with PKCα inhibition suggests that these two pathways are not independent and PKCα’s contribution to cAMP-PKA signaling may be a potential mechanism of inhibition of MAPK signaling with E2’s rapid activation of PKCα in normal uterine smooth muscle cells.

Figure 9.

cAMP signaling in normal UtSM-ht cells with PKC inhibition. cAMP levels in UtSM-ht cells pretreated with either vehicle (Veh) or 100 nm Ro31,8220 and then treated for 5 min with either vehicle or 1 nm E2. Cells treated for 5 min with E2 alone had significantly higher cAMP levels than cells treated with vehicle alone (*, P < 0.001). Cells pretreated with 100 nm Ro31,8220 and then treated for 5 min with 1 nm E2 had significantly reduced cAMP levels compared with E2-treated cells (**, P < 0.001).

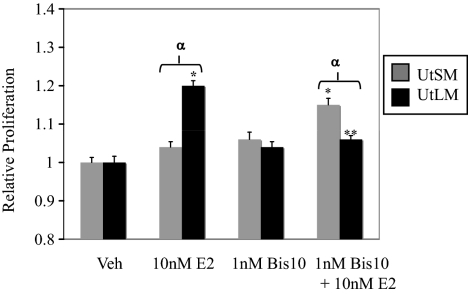

Inhibition of conventional PKCs results in reduced proliferation in leiomyoma cells but increased proliferation in normal uterine smooth muscle cells

Pharmacological inhibition of PKC in leiomyoma cells led to reduced proliferation in response to E2 treatment (Fig. 10). In fact, PKC inhibition reduced E2-stimulated proliferation in leiomyoma cells to that observed in normal smooth muscle cells. This finding is in agreement with our observation that PKCα inhibition results in lowered levels of phosphorylated proliferation-associated ERK1/2 in leiomyoma cells.

Figure 10.

Proliferation of normal UtSM-ht and UtLM-ht cells with PKC inhibition. Proliferation was measured by MTS assay on d 5 with either vehicle (Veh; control), 10 nm E2, 100 pm Bis10, or 100 pm Bis10 + 10 nm E2. For UtLM-ht, cells treated with 10 nm E2 had significantly higher levels of proliferation than vehicle-treated cells (*, P < 0.001). Cells treated with 10 nm E2 and Bis10 had significantly reduced levels of proliferation compared with E2-treated cells (**, P < 0.001). For UtSM-ht, cells treated with Bis10 and E2 had significantly higher proliferation than cells treated with vehicle or E2 (*, P < 0.001). Rates of proliferation were significantly different between UtLM-ht and UtSM-ht cells (α, P < 0.01).

On the other hand, pharmacological inhibition of conventional PKCs in normal uterine smooth muscle cells led to increased proliferation in response to E2 treatment (Fig. 10). Again, this data are in agreement with our finding that PKCα inhibition raises levels of phospho-ERK1/2, a proliferative signal, in E2-treated normal uterine smooth muscle cells.

Discussion

All experiments were conducted with immortalized UtSM-ht and UtLM-ht cells. Studies characterizing these cells have found that, unlike primary uterine leiomyoma cells (68), ER and progesterone receptor expression is maintained, thus allowing for the study of ER-dependent processes (69). In our laboratory, UtLM-ht cells express increased ER mRNA and protein levels compared with normal uterine smooth muscle cells (supplemental Fig. 4). This finding is consistent with other laboratories that have found increased levels of ERα in leiomyoma cells (70). Genomic signaling and E2 sensitivity in this leiomyoma cell line is intact and the use of these immortalized cell lines allows for the manipulation and study of rapid E2 signaling pathways.

In this study, we found differential rapid E2 signaling between the normal uterine smooth muscle and leiomyoma cells. Normal uterine smooth muscle is normally quiescent except during pregnancy. Our studies found that E2 does not promote ERK1/2 activation in our uterine smooth muscle cells but instead triggers pathways that are inhibitory to MAPK activation and proliferation. In contrast, we observe that these rapid E2 signaling pathways are altered or absent in leiomyoma cells to promote ERK1/2 activation and proliferation.

E2 triggers a rapid increase in levels of phosphorylated ERK1/2 via an ER-dependent mechanism in immortalized human uterine leiomyoma cells. ERK1/2 is the downstream effector of the proproliferative MAPK cascade that is typically activated by growth factors. Growth factor signaling pathways have been previously identified as being important to the expansion of leiomyomas. Leiomyomas may therefore be particularly susceptible to rapid effects of estrogens due to the integration of E2 and growth factor signaling (58,71,72,73). For example, previous findings from our laboratory (Martin M, Nierth-Simpson E, T.C. Chiang, and J.A. McLachlan JA, unpublished data) and others found that E2 treatment leads to the up-regulation of IGF-I (50,54,56,74). The findings of this study suggest that rapid actions of estrogens may increase the sensitivity of leiomyoma cells to proliferation by jump-starting growth factor loops, via the rapid activation of ERK1/2, that then sustain proliferation in leiomyoma cells.

The formation of cAMP in response to E2 in the uterus is one of the first described rapid E2 actions (75). We also found a rapid E2-induced increase in cAMP levels in normal uterine smooth muscle cells Increasing levels of cAMP triggers the activation of cAMP-dependent PKA, which has been shown to interact with the MAPK cascade (63,65). Depending on the cellular context, cAMP-PKA signaling may promote MAPK activation or inhibit Ras and Raf interaction (63,65). cAMP plays important roles in maintaining quiescence in uterine smooth muscle (76) and may also be important in reducing a proliferative response to estrogens because our study demonstrates that E2-induced cAMP-PKA signaling reduces ERK1/2 phosphorylation and proliferation in normal uterine smooth muscle cells. Although we demonstrate that cAMP signaling can reduce proliferation in leiomyoma cells, an increase in cAMP is not observed in leiomyoma cells with E2. The absence of this antiproliferative pathway may contribute to leiomyoma growth. Interestingly, cAMP signaling rapidly initiated by E2 may also suppress a transcriptional response to E2 because treatment of normal uterine smooth muscle cells with E2 and the PKA inhibitor H-89 results in significantly higher levels of E2-responsive progesterone receptor transcripts (supplemental Fig. 5). This finding is in agreement with a growing body of evidence that demonstrates that nongenomic/rapid signaling events can influence genomic events (77).

E2 has also been shown to differentially activate PKC isoforms (78,79) to influence proliferation in several cell lines (80). PKCα is a conventional PKC isoform that is similarly expressed between leiomyoma and normal uterine smooth muscle and, in addition to PKCζ, is the predominantly expressed isoform in uterine smooth muscle (81,82). Our data demonstrate that E2 rapidly increases levels of phospho-PKCα in both leiomyoma and normal uterine smooth muscle cells. Phosphorylation of the activation loop of PKCα is central to PKCα activity (83). When levels of Ca2+ and diacylglycerol rise, phosphorylated PKCα is recruited to the membrane for receptor-mediated targeting (84). Estrogens may affect PKCα activation via several mechanisms. First, we have shown that it can increase levels of phospho-PKCα. Second, we have found increased levels of active phospholipase C-β and -γ enzymes with E2 treatment (data not shown). Phospholipase C enzymes generate the Ca2+ and diacylglycerol necessary for full PKCα activation.

In this study, we report that E2-induced phospho-PKCα interacts with the proliferative MAPK cascade to inhibit phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in normal uterine smooth muscle cells. The effect of E2’s rapid increase in phospho-PKCα on inhibition of uterine smooth muscle proliferation may be 2-fold. First, we have shown that PKCα can inhibit ERK1/2 activation and that its promotion of cAMP-PKA signaling may be an important contributing mechanism to this inhibition. Second, it has been shown that PKC modifies ER binding by decreasing levels of cytosolic ER, thus lowering responsiveness to E2 in uteri (85). E2 has also been found to increase membrane-associated PKC isozyme expression in uterine muscle (86), which could further potentiate this antiproliferative effect. The inhibition of MAPK and cell growth with E2, although not generally observed in cells of epithelial origin, is not unique to uterine smooth muscle (87). Interestingly, it also occurs in another smooth muscle type: vascular smooth muscle (88).

Although we also observe an E2-induced increase in phospho-PKCα in leiomyoma cells, PKCα promotes ERK1/2 activation and proliferation in this cell type. PKCα has been shown to increase Ras activation (71,89,90) and can directly phosphorylate Raf (91), both of which are upstream of ERK1/2, in a variety of cell systems. Elevated levels of ERα may partially account for the greater levels of E2-induced phospho-PKCα, an ER-dependent process, in the leiomyoma vs. the normal uterine smooth muscle cells.

Interestingly, like cAMP-PKA signaling, PKCα also has important functions in uterine smooth muscle because it is involved in endothelin-1 and platelet-derived growth factor-induced ERK1/2 activation, human chorionic gonadotropin action (92), and growth in human and rat uterine smooth muscle cells during pregnancy (93,94). It has been proposed that uterine leiomyomas share characteristics with pregnant uterine smooth muscle cells (95), and a gene expression profile in an animal model shows that leiomyomas express several pregnancy-related genes (96). In this investigation, we demonstrate a mechanistic similarity between pregnant uterine smooth muscle and leiomyoma cells, PKCα’s interaction with the MAPK cascade.

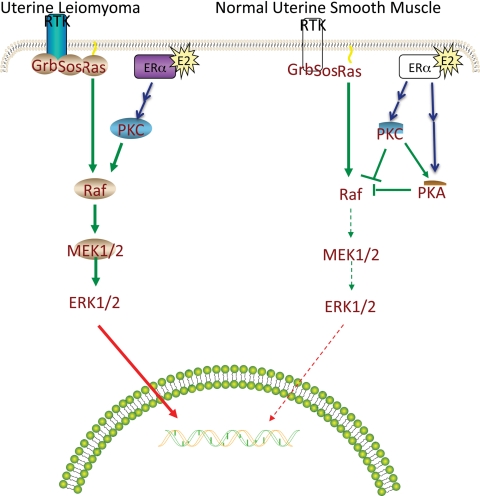

This study presents a unique model system to investigate both mechanisms and biological impacts of rapid E2 signaling. Moreover, due to the noncancerous nature of leiomyomas, it allows for the study of pathways important to proliferation in the absence of neoplastic transformation. In conclusion, this report demonstrates that E2’s rapid activation of PKCα and cAMP signaling inhibits ERK1/2 activation in normal uterine smooth muscle cells and serves to prevent growth in this normally quiescent tissue (Fig. 11). However, this signaling becomes altered in the case of uterine leiomyoma disease such that an antiproliferative signal is either absent, as in the case of cAMP signaling, or is converted to a signal that promotes ERK1/2 activation and proliferation (PKCα signaling). Further investigation into upstream targets of E2 that result in the differential rapid signaling between normal uterine smooth muscle and leiomyoma cells should prove useful in finding a therapeutic target for the treatment of leiomyoma disease.

Figure 11.

Proposed pathway. In this model, E2 binds to the ER, resulting in PKCα activation, which in turn promotes ERK1/2 activation and proliferation in leiomyoma cells. Likewise, E2 binds to the ER in normal UtSM-ht cells to activate PKCα in normal UtSM-ht cells. However, activated PKCα promotes cAMP-PKA signaling, which in turn inhibits ERK1/2 activation, E2-dependent genomic response, and proliferation in normal uterine smooth muscle. RTK, Receptor: tyrosine kinase; MEK, mitogen-activated/extracellular signal-regulated kinase.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Darlene Dixon, Ph.D., for the generous donation of the UtLM-ht and UtSM-ht cell lines. We also thank Barbara Beckman, Ph.D., for her donation of the constitutive-active and dominant-negative PKC plasmids. Lastly, we thank Syreeta Tilgman, Ph.D., Melyssa Bratton, Ph.D., and Ashley Fornerette for technical advice and manuscript revision.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Grant N000140611136 from the Office of Naval Research, Grant DK059389 from the National Institutes of Health, and a postdoctoral fellowship from the Louisiana Cancer Research Consortium.

Disclosure Summary: The authors of this manuscript have nothing to declare.

First Published Online January 29, 2009

Abbreviations: Bis10, Bisindolymaleimide × hydrochloride; 8brcAMP, 8-bromoadenosine-cAMP; E2, 17β-estradiol; ER, estrogen receptor; FBS, fetal bovine serum; IBMX, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine; MTS, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt; PKA, protein kinase A; PKC, protein kinase C; UtLM-ht, Uterine leiomyoma; UtSM-ht, uterine smooth muscle.

References

- Flake GP, Andersen J, Dixon D 2003 Etiology and pathogenesis of uterine leiomyomas: a review. Environ Health Perspect 111:1037–1054 (Review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbold RR, DiAugustine RP, Risinger JI, Everitt JI, Walmer DK, Parrott EC, Dixon D 2000 Advances in uterine leiomyoma research: conference overview, summary, and future research recommendations. Environ Health Perspect 108(Suppl 5):769–773 (Review) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumsden MA, Wallace EM 1998 Clinical presentation of uterine fibroids. Baillieres Clin Obstet Gynaecol 12:177–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hendy A, Salama SA 2006 Ethnic distribution of estrogen receptor-alpha polymorphism is associated with a higher prevalence of uterine leiomyomas in black Americans. Fertil Steril 86:686–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross RK, Pike MC, Vessey MP, Bull D, Yeates D, Casagrande JT 1986 Risk factors for uterine fibroids: reduced risk associated with oral contraceptives. Br Med J Clin Res Ed [Erratum (1986) 293:1027] 293:359–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall LM, Spiegelman D, Goldman MB, Manson JE, Colditz GA, Barbieri RL, Stampfer MJ, Hunter DJ 1998 A prospective study of reproductive factors and oral contraceptive use in relation to the risk of uterine leiomyomata. Ferti Steril 70:432–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JD, Davis BJ, Cai SL, Barrett JC, Conti CJ, Walker CL 2005 Interaction between genetic susceptibility and early-life environmental exposure determines tumor-suppressor-gene penetrance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:8644–8649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbold RR, Moore AB, Dixon D 2002 Characterization of uterine leiomyomas in CD-1 mice following developmental exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES). Toxicol Pathol 30:611–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird DD, Newbold R 2005 Prenatal diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure is associated with uterine leiomyoma development. Reprod Toxicol 20:81–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan JA, Newbold RR, Bullock BC 1980 Long-term effects on the female mouse genital tract associated with prenatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol. Cancer Res 40:3988–3999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall LM, Spiegelman D, Manson JE, Goldman MB, Barbieri RL, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Hunter DJ 1998 Risk of uterine leiomyomata among premenopausal women in relation to body size and cigarette smoking. Epidemiology 9:511–517 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedeutour F, Ligon AH, Morton CC 1999 [Genetics of uterine leiomyomata] (French). Bull Cancer 86:920–928 (Review) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligon AH, Morton CC 2001 Leiomyomata: heritability and cytogenetic studies. Hum Reprod Update 7:8–14 (Review) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sornberger KS, Weremowicz S, Williams AJ, Quade BJ, Ligon AH, Pedeutour F, Vanni R, Morton CC 1999 Expression of HMGIY in three uterine leiomyomata with complex rearrangements of chromosome 6. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 114:9–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rein MS, Powell WL, Walters FC, Weremowicz S, Cantor RM, Barbieri RL, Morton CC 1998 Cytogenetic abnormalities in uterine myomas are associated with myoma size. Mol Hum Reprod 4:83–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampath D, Zhu Y, Winneker RC, Zhang Z 2001 Aberrant expression of Cyr61, a member of the CCN (CTGF/Cyr61/Cef10/NOVH) family, and dysregulation by 17β-estradiol and basic fibroblast growth factor in human uterine leiomyomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:1707–1715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Chiang TC, Davis GR, Williams RM, Wilson VP, McLachlan JA 2001 Decreased expression of Wnt7a mRNA is inversely associated with the expression of estrogen receptor-α in human uterine leiomyoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:454–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Chiang TC, Richard-Davis G, Barrett JC, Mclachlan JA 2003 DNA hypomethylation and imbalanced expression of DNA methyltransferases (DNMT1, 3A, and 3B) in human uterine leiomyoma. Gynecol Oncol 90:123–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, McLachlan JA 2001 Estrogen-associated genes in uterine leiomyoma. Ann NY Acad Sci 948:112–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi K, Fujii S, Konishi I, Iwai T, Nanbu Y, Nonogaki H, Ishikawa Y, Mori T 1991 Immunohistochemical analysis of oestrogen receptors, progesterone receptors and Ki-67 in leiomyoma and myometrium during the menstrual cycle and pregnancy. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol 419:309–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon D, Flake GP, Moore AB, He H, Haseman JK, Risinger JI, Lancaster JM, Berchuck A, Barrett JC, Robboy SJ 2002 Cell proliferation and apoptosis in human uterine leiomyomas and myometria. Virchows Arch 441:53–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruo T, Ohara N, Wang J, Matsuo H 2004 Sex steroidal regulation of uterine leiomyoma growth and apoptosis. Hum Reprod Update 10:207–220 (Review) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JD, Walker CL 2004 Treatment strategies for uterine leiomyoma: the role of hormonal modulation. Semin Reprod Med 22:105–111 (Review) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker CL 2002 Role of hormonal and reproductive factors in the etiology and treatment of uterine leiomyoma. Rec Prog Horm Res 57:277–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman AJ, Hoffman DI, Comite F, Browneller RW, Miller JD 1991 Treatment of leiomyomata uteri with leuprolide acetate depot: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. The Leuprolide Study Group. Obstet Gynecol 77:720–725 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker CL, Burroughs KD, Davis B, Sowell K, Everitt JI, Fuchs-Young R 2000 Preclinical evidence for therapeutic efficacy of selective estrogen receptor modulators for uterine leiomyoma. J Soc Gynecol Investig 7:249–256 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs-Young R, Howe S, Hale L, Miles R, Walker C 1996 Inhibition of estrogen-stimulated growth of uterine leiomyomas by selective estrogen receptor modulators. Mol Carcinogen 17:151–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hendy A, Lee EJ, Wang HQ, Copland JA 2004 Gene therapy of uterine leiomyomas: adenovirus-mediated expression of dominant negative estrogen receptor inhibits tumor growth in nude mice. Am J Obstet Gynecol 191:1621–1631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hendy A, Salama S 2006 Gene therapy and uterine leiomyoma: a review. Hum Reprod Update 12:385–400 (Review) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruo T, Matsuo H, Shimomura Y, Kurachi O, Gao Z, Nakago S, Yamada T, Chen W, Wang J 2003 Effects of progesterone on growth factor expression in human uterine leiomyoma. Steroids 68:817–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T, Nakago S, Kurachi O, Wang J, Takekida S, Matsuo H, Maruo T 2004 Progesterone down-regulates insulin-like growth factor-I expression in cultured human uterine leiomyoma cells. Hum Reprod 19:815–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker CL, Cesen-Cummings K, Houle C, Baird D, Barrett JC, Davis B 2001 Protective effect of pregnancy for development of uterine leiomyoma. Carcinogenesis 22:2049–2052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shynlova O, Oldenhof A, Dorogin A, Xu Q, Mu J, Nashman N, Lye SJ 2006 Myometrial apoptosis: activation of the caspase cascade in the pregnant rat myometrium at midgestation. Biol Reprod 74:839–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ER 2001 Cell localization, physiology, and nongenomic actions of estrogen receptors. J Appl Physiol 91:1860–1867 (Review) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cato AC, Nestl A, Mink S 2002 Rapid actions of steroid receptors in cellular signaling pathways. Sci STKE:RE9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman KM, Smith CL 2001 Intracellular signaling pathways: nongenomic actions of estrogens and ligand-independent activation of estrogen receptors. Front Biosci 6:D1379–D1391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driggers PH, Segars JH 2002 Estrogen action and cytoplasmic signaling pathways. Part II: the role of growth factors and phosphorylation in estrogen signaling. Trends Endocrinol Metab 13:422–427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenstein E, Tillmann HC, Christ M, Feuring M, Wehling M 2000 Multiple actions of steroid hormones—a focus on rapid, nongenomic effects. Pharmacol Rev 52:513–556 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ER 2005 Integration of the extranuclear and nuclear actions of estrogen. Mol Endocrinol 19:1951–1959 (Review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MJ, Levin ER 2001 Rapid actions of plasma membrane estrogen receptors. Trends Endocrinol Metab 12:152–156 (Review) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Katzenellenbogen BS 1993 Synergistic activation of estrogen receptor-mediated transcription by estradiol and protein kinase activators. Mol Endocrinol 7:441–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedram A, Razandi M, Aitkenhead M, Hughes CC, Levin ER 2002 Integration of the non-genomic and genomic actions of estrogen. Membrane-initiated signaling by steroid to transcription and cell biology. J Biol Chem 277:50768–50775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan N, Kow LM, Pfaff DW 2001 Early membrane estrogenic effects required for full expression of slower genomic actions in a nerve cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:12267–12271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acconcia F, Marino M 2003 Synergism between genomic and non genomic estrogen action mechanisms. IUBMB Life 55:145–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn WS, Kim KW, Bae SM, Yoon JH, Lee JM, Namkoong SE, Kim JH, Kim CK, Lee YJ, Kim YW 2003 Targeted cellular process profiling approach for uterine leiomyoma using cDNA microarray, proteomics and gene ontology analysis. Int J Exp Pathol 84:267–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catherino WH, Leppert PC, Stenmark MH, Payson M, Potlog-Nahari C, Nieman LK, Segars JH 2004 Reduced dermatopontin expression is a molecular link between uterine leiomyomas and keloids. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 40:204–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman PJ, Milliken DB, Gregg LC, Davis RR, Gregg JP 2004 Molecular characterization of uterine fibroids and its implication for underlying mechanisms of pathogenesis. Fertil Steril 82:639–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quade BJ, Wang TY, Sornberger K, Dal Cin P, Mutter GL, Morton CC 2004 Molecular pathogenesis of uterine smooth muscle tumors from transcriptional profiling. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 40:97–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skubitz KM, Skubitz AP 2003 Differential gene expression in uterine leiomyoma. J Lab Clin Med 141:297–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz CD, Afshari CA, Yu L, Hall KE, Dixon D 2005 Estrogen-induced changes in IGF-I, Myb family and MAP kinase pathway genes in human uterine leiomyoma and normal uterine smooth muscle cell lines. Mol Hum Reprod 11:441–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsibris JC, Segars J, Coppola D, Mane S, Wilbanks GD, O'Brien WF, Spellacy WN 2002 Insights from gene arrays on the development and growth regulation of uterine leiomyomata. Fertil Steril 78:114–121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Mahadevappa M, Yamamoto K, Wen Y, Chen B, Warrington JA, Polan ML 2003 Distinctive proliferative phase differences in gene expression in human myometrium and leiomyomata. Fertil Steril 80:266–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massarweh S, Osborne CK, Creighton CJ, Qin L, Tsimelzon A, Huang S, Weiss H, Rimawi M, Schiff R 2008 Tamoxifen resistance in breast tumors is driven by growth factor receptor signaling with repression of classic estrogen receptor genomic function. Cancer Res 68:826–833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tommola P, Pekonen F, Rutanen EM 1989 Binding of epidermal growth factor and insulin-like growth factor I in human myometrium and leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol 74:658–662 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar Y, Heiner J, Osuamkpe C, Nagamani M 1992 Insulin-like growth factor I and II binding in human myometrium and leiomyomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol 166(1 Pt 1):64–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ven LT, Roholl PJ, Gloudemans T, Van Buul-Offers SC, Welters MJ, Bladergroen BA, Faber JA, Sussenbach JS, Den Otter W 1997 Expression of insulin-like growth factors (IGFs), their receptors and IGF binding protein-3 in normal, benign and malignant smooth muscle tissues. Br J Cancer 75:1631–1640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burroughs KD, Howe SR, Okubo Y, Fuchs-Young R, LeRoith D, Walker CL 2002 Dysregulation of IGF-I signaling in uterine leiomyoma. J Endocrinol 172:83–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acconcia F, Totta P, Ogawa S, Cardillo I, Inoue S, Leone S, Trentalance A, Muramatsu M, Marino M 2005 Survival versus apoptotic 17β-estradiol effect: role of ERα and ERβ activated non-genomic signaling. J Cell Physiol 203:193–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlert S, Nuedling S, van Eickels M, Vetter H, Meyer R, Grohe C 2000 Estrogen receptor α rapidly activates the IGF-1 receptor pathway. J Biol Chem 275:18447–18453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surmacz E, Bartucci M 2004 Role of estrogen receptor α in modulating IGF-I receptor signaling and function in breast cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 23:385–394 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen J, DyReyes VM, Barbieri RL, Coachman DM, Miksicek RJ 1995 Leiomyoma primary cultures have elevated transcriptional response to estrogen compared with autologous myometrial cultures. J Soc Gynecol Investig 2:542–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burroughs KD, Fuchs-Young R, Davis B, Walker CL 2000 Altered hormonal responsiveness of proliferation and apoptosis during myometrial maturation and the development of uterine leiomyomas in the rat. Biol Reprod 63:1322–1330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook SJ, McCormick F 1993 Inhibition by cAMP of Ras-dependent activation of Raf. Science 262:1069–1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerits N, Kostenko S, Shiryaev A, Johannessen M, Moens U 2008 Relations between the mitogen-activated protein kinase and the cAMP-dependent protein kinase pathways: comradeship and hostility. Cell Signal 20:1592–1607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Dent P, Jelinek T, Wolfman A, Weber MJ, Sturgill TW 1993 Inhibition of the EGF-activated MAP kinase signaling pathway by adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate. Science 262:1065–1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bit RA, Davis PD, Elliott LH, Harris W, Hill CH, Keech E, Kumar H, Lawton G, Maw A, Nixon JS, et al 1993 Inhibitors of protein kinase C. 3. Potent and highly selective bisindolylmaleimides by conformational restriction. J Med Chem 36:21–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twomey B, Muid RE, Nixon JS, Sedgwick AD, Wilkinson SE, Dale MM 1990 The effect of new potent selective inhibitors of protein kinase C on the neutrophil respiratory burst. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 171:1087–1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severino MF, Murray MJ, Brandon DD, Clinton GM, Burry KA, Novy MJ 1996 Rapid loss of oestrogen and progesterone receptors in human leiomyoma and myometrial explant cultures. Mol Hum Reprod 2:823–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney SA, Tahara H, Swartz CD, Risinger JI, He H, Moore AB, Haseman JK, Barrett JC, Dixon D 2002 Immortalization of human uterine leiomyoma and myometrial cell lines after induction of telomerase activity: molecular and phenotypic characteristics. Lab Invest 82:719–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benassayag C, Leroy MJ, Rigourd V, Robert B, Honore JC, Mignot TM, Vacher-Lavenu MC, Chapron C, Ferre F 1999 Estrogen receptors (ERα/ERβ) in normal and pathological growth of the human myometrium: pregnancy and leiomyoma. Am J Physiol 276(6 Pt 1):E1112–E1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evinger 3rd AJ, Levin ER 2005 Requirements for estrogen receptor α membrane localization and function. Steroids 70:361–363 (Review) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan JA, Nelson KG, Takahashi T, Bossert NL, Newbold RR, Korach KS 1991 Do growth factors mediate estrogen action in the uterus? In: Hochberg RB, Naftolin F, eds. The new biology of steroid hormones. New York: Raven Press; 337–344 [Google Scholar]

- Ignar-Trowbridge DM, Pimentel M, Teng CT, Korach KS, McLachlan JA 1995 Cross-talk between peptide growth factor and estrogen receptor signaling systems. Proceedings of the Conference on Estrogens in the Environment III: Global Health Implications. Environ Health Perspect 103(Suppl 7):35–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z, Matsuo H, Wang Y, Nakago S, Maruo T 2001 Up-regulation by IGF-I of proliferating cell nuclear antigen and Bcl-2 protein expression in human uterine leiomyoma cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:5593–5599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szego CM, Davis JS 1967 Adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate in rat uterus: acute elevation by estrogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 58:1711–1718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price SA, Bernal AL 2001 Uterine quiescence: the role of cyclic AMP. Exp Physiol 86:265–272 (Review) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acconcia F, Kumar R 2006 Signaling regulation of genomic and nongenomic functions of estrogen receptors. Cancer Lett 238:1–14 (Review) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyan BD, Sylvia VL, Frambach T, Lohmann CH, Dietl J, Dean DD, Schwartz Z 2003 Estrogen-dependent rapid activation of protein kinase C in estrogen receptor-positive MCF-7 breast cancer cells and estrogen receptor-negative HCC38 cells is membrane-mediated and inhibited by tamoxifen. Endocrinology 144:1812–1824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvia VL, Hughes T, Dean DD, Boyan BD, Schwartz Z 1998 17β-Estradiol regulation of protein kinase C activity in chondrocytes is sex-dependent and involves nongenomic mechanisms. J Cell Physiol 176:435–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino M, Distefano E, Caporali S, Ceracchi G, Pallottini V, Trentalance A 2001 β-Estradiol stimulation of DNA synthesis requires different PKC isoforms in HepG2 and MCF7 cells. J Cell Physiol 188:170–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tertrin-Clary C, Eude I, Fournier T, Paris B, Breuiller-Fouche M, Ferre F 1999 Contribution of protein kinase C to ET-1-induced proliferation in human myometrial cells. Am J Physiol 276:E503–E511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eude I, Tertrin-Clary C, Vacher-Lavenu MC, Chapron C, Ferré F, Breuiller-Fouché M 2001 Differential regulation of protein kinase C isoforms in human uterine leiomyoma. Gynecol Obstet Invest 51:191–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki T, Matsubayashi H, Amano T, Shirai Y, Saito N, Sakai N 2005 Phosphorylation of PKC activation loop plays an important role in receptor-mediated translocation of PKC. Genes Cells 10:225–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pears C, Stabel S, Cazaubon S, Parker PJ 1992 Studies on the phosphorylation of protein kinase Cα. Biochem J 283(Pt 2):515–518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliaccio S, Washburn TF, Fillo S, Rivera H, Teti A, Korach KS, Wetsel WC 1998 Modulation of estrogen receptor levels in mouse uterus by protein kinase C isoenzymes. Endocrinology 139:4598–4606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzycky AL, Kulick A 1996 Estrogen increases the expression of uterine protein kinase C isozymes in a tissue specific manner. Eur J Pharmacol 313:257–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey RK, Gillespie DG, Mi Z, Rosselli M, Keller PJ, Jackson EK 2000 Estradiol inhibits smooth muscle cell growth in part by activating the cAMP-adenosine pathway. Hypertension 35(1 Pt 2):262–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey AK, Pedram A, Razandi M, Prins BA, Hu RM, Biesiada E, Levin ER 1997 Estrogen and progesterone inhibit vascular smooth muscle proliferation. Endocrinology 138:3330–3339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington WR, Kim SH, Funk CC, Madak-Erdogan Z, Schiff R, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS 2006 Estrogen dendrimer conjugates that preferentially activate extranuclear, nongenomic versus genomic pathways of estrogen action. Mol Endocrinol 20:491–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliaccio A, Di Domenico M, Castoria G, de Falco A, Bontempo P, Nola E, Auricchio F 1996 Tyrosine kinase/p21ras/MAP-kinase pathway activation by estradiol-receptor complex in MCF-7 cells. EMBO J 15:1292–1300 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolch W, Heidecker G, Kochs G, Hummel R, Vahidi H, Mischak H, Finkenzeller G, Marmé D, Rapp UR 1993 Protein kinase Cα activates RAF-1 by direct phosphorylation. Nature 364:249–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisielewska J, Flint AP, Ziecik AJ 1996 Phospholipase C and adenylate cyclase signalling systems in the action of hCG on porcine myometrial smooth muscle cells. J Endocrinol 148:175–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eude I, Dallot E, Ferré F, Breuiller-Fouché M 2002 Protein kinase Cα is required for endothelin-1-induced proliferation of human myometrial cells. Biol Reprod 66:44–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes LE, Moore LG, Walchak SJ, Dempsey EC 1996 Pregnancy-stimulated growth of vascular smooth muscle cells: importance of protein kinase C-dependent synergy between estrogen and platelet-derived growth factor. J Cell Physiol 166:22–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesen-Cummings K, Walker CL, Davis BJ 2000 Lessons from pregnancy and parturition: uterine leiomyomas result from discordant differentiation and dedifferentiation responses in smooth muscle cells. Med Hypotheses 55:485–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesen-Cummings K, Houston KD, Copland JA, Moorman VJ, Walker CL, Davis BJ 2003 Uterine leiomyomas express myometrial contractile-associated proteins involved in pregnancy-related hormone signaling. J Soc Gynecol Investig 10:11–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.