Abstract

In eukaryotic organisms, initiation of mRNA turnover is controlled by progressive shortening of the poly-A tail, a process involving the mega-Dalton Ccr4-Not complex and its two associated 3′-5′ exonucleases, Ccr4p and Pop2p (Caf1p). RNA degradation by the 3′-5′ DEDDh exonuclease, Pop2p, is governed by the classical two metal ion mechanism traditionally assumed to be dependent on Mg2+ ions bound in the active site. Here, we show biochemically and structurally that fission yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe) Pop2p prefers Mn2+ and Zn2+ over Mg2+ at the concentrations of the ions found inside cells and that the identity of the ions in the active site affects the activity of the enzyme. Ion replacement experiments further suggest that mRNA deadenylation could be subtly regulated by local Zn2+ levels in the cell. Finally, we use site-directed mutagenesis to propose a mechanistic model for the basis of the preference for poly-A sequences exhibited by the Pop2p-type deadenylases as well as their distributive enzymatic behavior.

Keywords: mRNA turnover, deadenylation, Ccr4–Not, Pop2p, DEDD exonuclease, zinc

INTRODUCTION

Regulation of the rate of cytoplasmic mRNA turnover is crucial for the abundance of transcripts available to the protein synthesis apparatus and therefore constitutes a central control point in gene expression. In eukaryotes, the main cytoplasmic mRNA degradation pathway begins with progressive shortening of the poly-A tail (deadenylation), a process which is normally followed by removal of the 5′ cap structure (decapping) and 5′-3′ exonucleolytic degradation (for reviews, see Parker and Song 2004; Goldstrohm and Wickens 2008). A secondary pathway involves transcripts being degraded in the 3′-5′ direction by the RNA exosome immediately following deadenylation (Parker and Song 2004). In budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, deadenylation is mainly controlled by the mega-Dalton Ccr4-Not complex consisting of at least nine proteins, Ccr4p, Pop2p (Caf1p), Not1/2/3/4/5p, Caf40p, and Caf130p (Chen et al. 2001). The complex has been implicated in a wide range of cellular functions, but the actual deadenylase activity has been mapped to the Ccr4p and Pop2p subunits, containing exonuclease–endonuclease–phosphatase (EPP) and DEDD exonuclease domains, respectively (Tucker et al. 2001; Goldstrohm and Wickens 2008). It is not presently known whether the cell requires both types of nucleases to cope with all cytoplasmic deadenylation or only uses one of the enzymes. Consistent with the second model, functional studies carried out both in vivo and in vitro indicate that Ccr4p may be the main nuclease (Chen et al. 2002; Tucker et al. 2002). Nevertheless, deletion of the Pop2p gene does affect the rate of deadenylation (Daugeron et al. 2001; Tucker et al. 2001) and yeast two-hybrid interaction studies have further suggested a direct interaction between Ccr4p and Pop2p (Bai et al. 1999). It was therefore proposed that Pop2p might form a physical bridge between Ccr4p and the rest of Ccr4-Not without being directly involved in catalysis (Bai et al. 1999). Pop2p is a member of the DEDDh class of 3′-5′ exonucleases, but the consensus DEDD motif is replaced by SEDQ in S. cerevisiae, so that the enzyme in budding yeast lacks several highly conserved residues essential for catalysis. This observation supports the idea that Pop2p might serve as a mere architectural role and that the active site therefore has diverged through the course of evolution. However, the crystal structure of the S. cerevisiae Pop2p confirmed its overall structural similarity to the DEDD nucleases and, moreover, the noncanonical enzyme was shown to function as an active exonuclease on several monotonous RNA sequences in vitro (poly-U, poly-A, and poly-C) with a subtle preference for poly-A (Daugeron et al. 2001; Thore et al. 2003).

To understand the involvement of the eukaryotic Pop2p protein in deadenylation, we have undertaken a structural and functional investigation of the homologous protein from fission yeast, Schizosaccharomyces pombe. While much less is known about the RNA turnover processes in S. pombe, the strong conservation of the caf1 gene and the Ccr4-Not complex in eukaryotes from yeast to humans led us to suggest that Pop2p maintains a similar function in S. pombe as has been observed in other eukaryotes (Albert et al. 2000; Bianchin et al. 2005). Most importantly, the S. pombe ortholog has a fully conserved DEDDh active site, and combined structural and functional data subsequently showed that the protein is a functional 3′-5′ exonuclease specific to RNA with a tuneable preference for poly-A sequences (Jonstrup et al. 2007). Structural studies of a number of related hydrolytic exonucleases active on both DNA and RNA have shown that they invariably contain two adjacent divalent metal ion binding sites termed “A” and “B” (Beese and Steitz 1991; Yang et al. 2006; Yang 2008). The two metal ions play essential roles in catalysis by neutralizing the negatively charged RNA, activating the hydrolytic water molecule for a nucleophilic attack on the phosphodiester backbone, and stabilizing the negatively charged transition state and the new 3′ end after hydrolysis (Steitz and Steitz 1993). Due to the relatively high intracellular concentration of Mg2+ (5–10 mM) compared to other divalent metal ions, it has generally been assumed that the exonucleases use Mg2+ in both their active site positions in vivo (Yang et al. 2006; Yang 2008). But the true identity of the ions in vivo has in many cases remained elusive as it is exceedingly difficult to isolate the enzymes from native source without affecting the constituents of the active site as well as determine the identity and location of the ions from prepared protein.

In this paper, we show by using X-ray crystallography that, at the approximate concentrations of Mg2+, Zn2+, and Mn2+ found inside cells, Pop2p specifically picks up Zn2+ in the A site and Mn2+ in the B site despite a large excess of Mg2+. At lower Zn2+ concentrations, Mg2+ replaces Zn2+ in the A site, but Mn2+ always occupies the B site. We also show that the identity of ions in the active site affects the speed of the RNA degradation reaction on defined mRNA mimics in vitro and, to a limited extent, base selectivity. Finally, using site-directed mutagenesis, we identify specific conserved side chains in the active site of the enzyme which are responsible for both poly-A selectivity and the distributive enzymatic behavior of the Pop2p-type deadenylases and correlate this with the structural changes observed in the presence of the various ions.

RESULTS

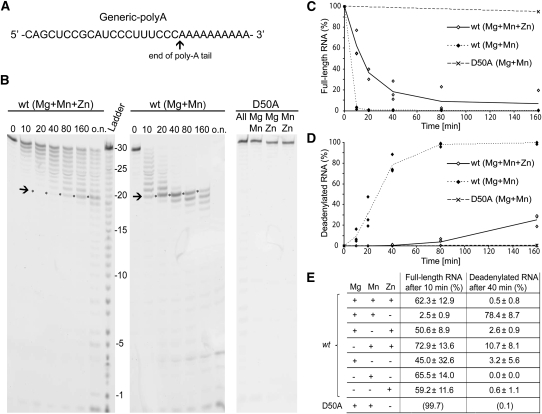

The kinetics of deadenylation by Pop2p are affected by the available ions

In order to be able to assess the effects of different combinations of divalent metal ions on the activity and selectivity of isolated S. pombe Pop2p in vitro, we set up deadenylation assays using a defined RNA substrate (“Generic-polyA”), consisting of a 20-nucleotide (nt) general RNA sequence with little or no secondary structure followed by a 10-nt poly-A tail mimic in the 3′ end (Fig. 1A). The in vitro deadenylation reactions were carried out in 50 mM KCl at pH 8.0 and approximate intracellular ionic conditions of the divalent metal ions Mg2+, Mn2+, and Zn2+ as measured inside eukaryotic cells by atomic absorption spectroscopy (7.1 mM Mg2+, 75 μM Mn2+, and 220 μM Zn2+) (Tholey et al. 1988; Jonstrup et al. 2007). To clearly define the composition of the active site and examine differential effects of combinations of ions, the enzyme was first equilibrated into the appropriate buffer by gel filtration. The extent of deadenylation by Pop2p was then measured by the degree of 3′ degradation of the defined, fluorescently labeled RNA substrate visualized by high-resolution denaturing urea-acrylamide electrophoresis (Fig. 1B). When Pop2p is equilibrated into a mixture of all thee ions (Mg2+, Mn2+, Zn2+) at their physiological concentrations, deadenylation of the substrate is slow and unspecific as indicated by a ladder of intermediate RNA sizes between 20 and 30 nt at most time points (Fig. 1B, left). Under these conditions, only ∼25% of the substrates are completely deadenylated after 160 min, as measured by the appearance of a 20-nt-long RNA species corresponding to removal of the 10-nt poly-A sequence in the 3′ end of the RNA substrate (Fig. 1B, marked with →; Fig. 1D, ◇). In addition, bands smaller than the fully deadenylated product appear before all substrates are fully deadenylated (Fig. 1B, left, lane “o.n.”). To ensure that the observed degradation pattern is indeed due to the specific activity of Pop2p, the experiments were repeated with a Pop2p D50A mutant, which is completely inactive because the conserved bidentate aspartate in the active site has been removed (Jonstrup et al. 2007). As can be seen in Figure 1B, there is no degradation of the RNA at any of the conditions in the presence of the active site mutant. The degradation behavior of the wild-type (wt) enzyme was not significantly affected within a generous range of salt concentrations and pH (10–500 mM KCl at pH 6–8) (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

In vitro deadenylation activity of S. pombe Pop2p. (A) Sequence of the “Generic-polyA” RNA substrate. ↑ indicates the end of the poly-A tail after 20 nt. The RNA contains a 5′ fluorescein modification (not shown). (B) Time course deadenylation experiments at the indicated combinations of 7.1 mM Mg2+, 75 μM Mn2+, and 220 μM Zn2+. The ladder shows individual base steps with → indicating the fully deadenylated product (20 nt). “D50A” shows equivalent experiments carried out with the D50A active site mutant as negative control. (C) Quantification of the Pop2p-mediated degradation showing the decay of full-length substrate and (D) build-up of the completely deadenylated RNA with time. Percentages are calculated as the integrated density of either the intact RNA band or the 20 nt intermediate product + smaller bands, normalized by the total lane density. The lines represent averages of three independent experiments with individual experiments shown with markers. (E) The relative activity of Pop2p in either initiating degradation [“Full-length RNA after 10 min (%)”] or completing deadenylation [“Deadenylated RNA after 40 min (%)”] at various conditions. The numbers for the D50A mutant are approximated based on the 160-min end point. Except for the D50A control, all numbers represent the average of three independent experiments ± standard deviation.

As most intracellular zinc is bound to proteins or located in zinc storage compartments (Jacob et al. 1998; MacDiarmid et al. 2000), we also carried out the experiments in the absence of zinc to investigate the effect on the RNA degradation kinetics. Surprisingly, Pop2p purified in the presence of just Mg2+ and Mn2+ quickly and specifically degrades the entire poly-A tail of the RNA substrate, and under these conditions 78% of the RNA is completely deadenylated after just 40 min (Fig. 1B,D, ◆; Fig. 1E). Particularly, and in contrast to the previous experiment, the 20-nt fully deadenylated RNA species appears to be transiently stabilized before degradation proceeds into non-poly-A RNA. In other words, both activity and selectivity of the enzyme are affected by the nature of the available ions. The effects can also be illustrated by quantitating how quickly Pop2p removes full-length RNA substrates at the two conditions (Fig. 1C). When only Mg2+ and Mn2+ are available, the enzyme quickly removes almost all full-length substrate and leaves only 2.5% of the RNA intact after 10 min (Fig. 1C, ◆; Fig. 1E). On the other hand, when Pop2p is incubated with all three ions, degradation is initiated much more slowly, and ∼62% of the full-length RNA still remains after 10 min (Fig. 1C, ◇; Fig. 1E). Figure 1E summarizes the activities of Pop2p at various conditions with one, two, or three ions present. The large standard deviation for some of the single-ion experiments, particularly Mg2+, is believed to be a result of partial carry-over of ions in the active site during purification of the enzyme. A comparison of the ability of the enzyme to initiate degradation, characterized by removal of the 3′-most nucleotide of the full-length substrate, shows that, in the presence of Mg2+ and Mn2+, the enzyme is some 20–30 times faster than at any of the other conditions (Fig. 1E). Similarly, when looking at the ability to produce fully deadenylated products, Pop2p is much faster in the presence of Mg2+ and Mn2+, which is the only condition producing a significant amount of deadenylated product after 40 min compared to any of the other conditions. In summary, our results show that Pop2p exhibits two distinct functional states: A “fast” state characterized by the presence of Mg2+ and Mn2+ and a “slow” state that prevails when Zn2+ is available.

The functional states can be verified by structural analysis

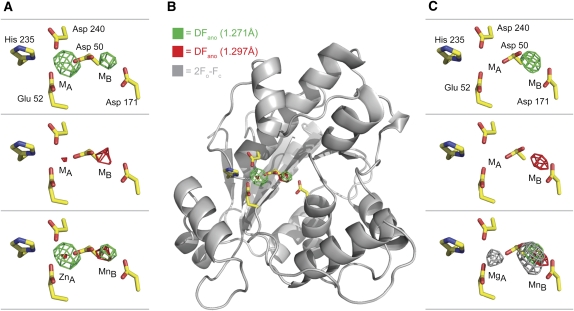

As indirect effects such as secondary ion binding sites on the protein or ions interacting with RNA cannot formally be ruled out as causes of the observed variations in the activity and selectivity of Pop2p described above, we next decided to crystallize the protein in the presence and absence of zinc to look for structural variations. To analyze the Zn2+-bound state, the protein was purified and crystallized under near-physiological concentrations of all three ions (7.1 mM Mg2+, 75 μM Mn2+, and 220 μM Zn2+), a condition which promotes slow kinetics in vitro. Two complete X-ray diffraction data sets were collected on a single crystal at 1.271 Å and 1.297 Å corresponding to the high and low sides of the Zn anomalous K-edge, respectively (Table 1). The structure was determined by molecular replacement using the known high resolution structure of S. pombe Pop2p (PDB ID 2P51) as search model (Jonstrup et al. 2007). An anomalous difference (ΔFano) Fourier map calculated from the data collected at 1.271 Å, at which both Zn2+ and Mn2+ have significant anomalous contributions of 3.8 e− and 2.0 e−, respectively, while the contribution from Mg2+ is negligible (0.1 e−), showed two electron density peaks in the active site corresponding to the position of the A and B sites (Fig. 2A, top panel, green density). As Mg2+ has no anomalous signal at the wavelengths used, this shows that Mg2+ is not present in the active site under these conditions, and therefore, that the protein picks up Mn2+ and/or Zn2+ from the buffer, even though their concentrations are much lower than that of Mg2+. Comparison with the data collected on the other side of the Zn2+ anomalous edge at 1.297 Å allows distinction between Mn2+ and Zn2+, as Zn2+ has a dramatically reduced anomalous signal at this X-ray energy (0.5 e−) while Mn2+ retains more or less the same signal as before (2.0 e−). In this case, the anomalous difference map shows a very small peak of electron density in the A site whereas the density in the B site is practically unchanged (Fig. 2A, middle panel, red density). This is more clearly seen when the two maps are superimposed (Fig. 2A, bottom panel), and shows that Zn2+ occupies the A site and Mn2+ the B site at near-physiological conditions. There are no other parts of the anomalous difference maps that have significant density, and only minor shifts of the side chains in the active site are seen compared to the original, Mg2+-bound structure (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Fig. 2). Taken together, this leads us to exclude any additional allosteric effects of Mn2+ and Zn2+. To visualize the configuration of the enzyme bound to Mg2+ and Mn2+, crystals of Pop2p grown in 200 mM magnesium acetate were soaked in a buffer containing physiological concentrations of Mg2+ and Mn2+ (7.1 mM and 75 μM, respectively), but no Zn2+. Two complete data sets were again collected on this crystal again on either side of the Zn K-edge (Table 1). The anomalous difference map calculated from data collected at the high side of the Zn absorption edge (1.271 Å) shows a clear peak of density in the B site but none in the A site (Fig. 2C, green density, top panel). The same is the case for the anomalous difference map calculated from data collected on the low side of the Zn edge (1.297 Å) (Fig. 2C, red density, middle panel). Together, the results show that, under these conditions, the B site is occupied by a Mn2+ ion. The fact that the enzyme retains its activity indicates that the A site most likely is occupied by a Mg2+ ion, which has no significant anomalous signal at either wavelength and is therefore not seen in the anomalous difference maps. This is confirmed by analysis of the 2Fo-Fc map calculated after refinement of the structure without ions, which clearly shows that there indeed are two ions in the active site (Fig. 2C, bottom panel, gray density), but only one of which exhibits X-ray absorption. Thus, we can conclude that, at conditions where the enzyme displays fast kinetics, Mg2+ replaces Zn2+ in the A site, whereas Mn2+ remains unaffected in the B site in both situations.

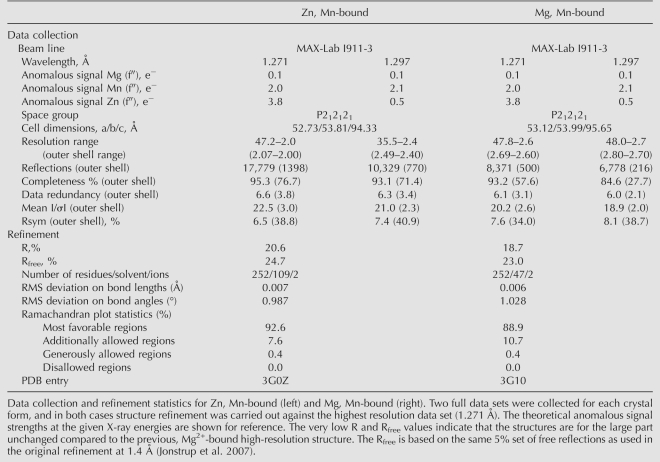

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

FIGURE 2.

Structural identification of the active site ions. (A) The active site of the refined structure of Pop2p crystallized at physiological concentrations of Mg2+, Mn2+, and Zn2+ (see the main text for details). The anomalous difference densities calculated from data collected at the high (1.271 Å, top, green density) and low (1.297 Å, middle, red density) side of the Zn anomalous edge. The bottom panel shows the two densities superimposed. The intensities of the peaks are 12.7 σ (A site, 1.271 Å, top), 8.0 σ (B site, 1.271 Å, top), 4.6 σ (A site, 1.297 Å, middle), and 6.2 σ (B site, 1.297 Å, middle). (B) Overall structure of S. pombe Pop2p shown as cartoon with the active site residues as sticks and the anomalous densities from A as overlay. (C) The active site of the refined structure of Pop2p determined from crystals soaked in physiological concentrations of Mg2+ and Mn2+, but in the absence of Zn2+, with anomalous difference maps at the two wavelengths superimposed on the structure as in A (top and middle panels), and bottom, superimposed on the 2Fo-Fc refined map from the data collected at 1.271 Å (gray). The intensities of the peaks are 5.7 σ (B site, 1.271 Å, top), 4.4 σ (B site, 1.297 Å, middle), 2.6 σ (A site, 2Fo-Fc, bottom), and 4.6 σ (B site, 2Fo-Fc, bottom).

The deadenylation activity can be dynamically modulated

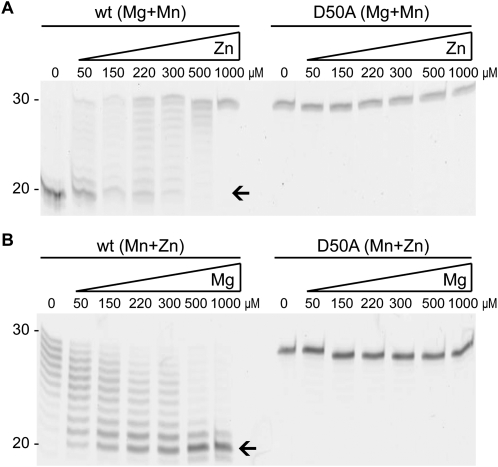

To test whether the activity of Pop2p can be modulated in a dynamic fashion, we next performed titration experiments to see if increasing concentration of the individual ions could affect the activity of the enzyme. When Pop2p binds Mg2+ and Mn2+, it processes the poly-A tail of the Generic-polyA substrate completely in ∼60 min in our assay (Fig. 3A, lane “0”). As the concentration of Zn2+ increases, the rate of deadenylation is reduced concomitantly and, at a concentration between 500 μM and 1 mM Zn2+, the enzyme is completely inactivated (Fig. 3A, left). There is no degradation of the RNA at any concentration of Zn2+ in the presence of the D50A active site mutant of Pop2 (Fig. 3A, right). The titration experiments confirm that the active enzyme either displays fast (0–150 μM Zn2+) or slow (500–1000 μM Zn2+) kinetics, with a switch point very close to the measured physiological concentration of Zn2+ of ∼200 μM. To analyze whether Zn2+ inactivates the enzyme in a reversible fashion, the reverse experiment was carried out in which the starting point was the slow form of Pop2p binding Mn2+ and Zn2+ (Fig. 3B, left). Under these initial conditions, the enzyme degrades the RNA very slowly and no completely deadenylated RNA species are visible even after 60 min of incubation (Fig. 3B, lane “0”). Gradual increase of the Mg2+ concentration leads to progressively more of the deadenylated product, indicating that Mg2+ substitutes Zn2+ in the A site. At a concentration of 500 μM–1 mM Mg2+, the enzyme has regained its full activity and degrades almost all poly-A during the 60-min reaction (Fig. 3B). We conclude that Pop2p is able to switch reversibly between different modes of degradation depending upon the availability of ions.

FIGURE 3.

Dynamic modulation of Pop2p deadenylase activity. (A) Titration experiments in which Pop2p equilibrated in physiological concentrations of Mg2+ and Mn2+ is gradually inactivated by addition of increasing amounts of Zn2+ as indicated. Only the region of the gels corresponding to RNA fragments sized between 20 and 30 nt is shown for clarity. (B) Reactivation of the Zn2+-bound form of Pop2p by gradual increase of the concentration of Mg2+ in the presence of Mn2+ and Zn2+ as indicated. The active site D50A mutant of Pop2p is shown as a negative control for both experiments.

The specificity and processivity of Pop2p are determined by residues in the active site

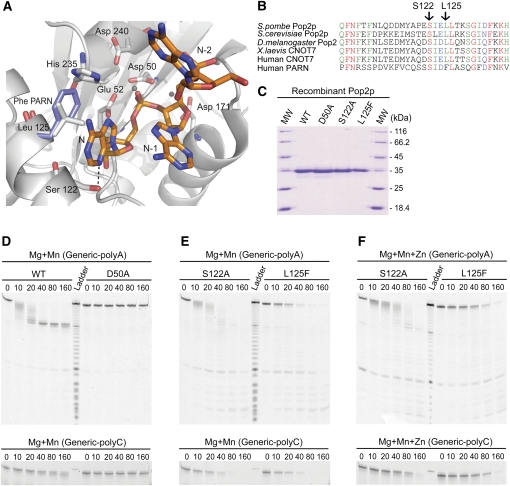

In order to explain the relationship between the variations in catalysis and the composition of ions in the active site, several point mutations were introduced and the mutant enzymes tested for their reaction kinetics. No co-crystal structures exist of S. pombe Pop2p bound to RNA as the active site is blocked by residues from a neighboring molecule in the crystal. However, based on careful superposition of several homologous enzymes, including PARN and the exonuclease domain of DNA polymerase I, a highly detailed model has been proposed for the binding of the 3′ end of poly-A RNA to the active site of Pop2p in the pre-hydrolysis state (Fig. 4A; Jonstrup et al. 2007). As our high resolution gels indicate that Pop2p degrades the poly-A tail down to the very last residue (see, e.g., Fig. 1B), any recognition of adenosine was expected to involve the very 3′ end of the substrate. Based on the superposition model of Pop2p and poly-A RNA, we identified two positions, S122 and L125, which could potentially interact directly with the last adenine base according to the model (Fig. 4A). S122 is conserved in Pop2p proteins from almost all species and is also found in the human poly-A specific ribonuclease (PARN), an additional deadenylase found in metazoa (Fig. 4B). On the other hand, L125 is conserved only in Pop2p-type deadenylase enzymes but substituted for phenylalanine in PARN, where it has been shown to stack with the last base of the bound RNA substrate (Fig. 4B; Wu et al. 2005). In our model of RNA-binding by Pop2p, S122 could form a hydrogen bond to the N3 of the ultimate adenosine, potentially allowing distinction between purine and pyrimidine bases, but not necessarily between A and G. However, with a guanine base, the exocyclic N2 group would most likely prevent the interaction, making direct recognition of adenosine a formal possibility. The hydrophobic side chain of L125 is located at a right angle to the base plane, potentially stabilizing the aromatic system in the active site (Fig. 4A). To assess the importance of the two positions for the activity and selectivity, both S122A and L125F mutants of Pop2p were constructed, purified to homogeneity, and analyzed using in vitro competition deadenylation assays (Fig. 4C–F). In these assays, the Generic-polyA RNA substrate was mixed in 1:1 molar ratio with a second substrate where the poly-A sequence had been replaced by 10 cytidine residues (Generic-polyC). In addition, Generic-polyC had a 5-carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA) fluorophore at the 5′ end which shows different excitation and emission characteristics compared to the fluorescein group used on Generic-polyA, thus allowing us to track the activity of Pop2p on the two substrates separately.

FIGURE 4.

Effects of active site mutations on kinetics and selectivity. (A) The RNA-bound form of Pop2p modeled by superposition of poly-A RNA from the structure of the human PARN (PDB ID 2A1R) (Wu et al. 2005), shown along with the active site residues and ions involved in catalysis or base recognition. The phenylalanine found in the human PARN structure corresponding to Leu125 in Pop2p is shown in blue stacking with the 3′ adenine base. (B) Alignment of the sequence region of interest around Ser122 and Leu125 in Pop2p homologs. Shown are S. pombe Pop2p (this study), S. cerevisiae Pop2p, Drosophila melanogaster Pop2, Xenopus laevis CNOT7, and human CNOT7 along with the corresponding region in human PARN. (C) Coomassie-blue stained SDS-PAGE gel showing the recombinant, purified wt, D50A, S122A, and L125F Pop2p proteins used for in vitro RNA degradation assays. (D–F) Time course competition deadenylation experiments using wt Pop2p, D50A, S1222A, or L125F and a 1:1 molar ratio of Generic-polyA (top) and Generic-polyC RNA substrates (bottom, showing full-length band only) in the presence of either Mg2+ and Mn2+ or all thee ions, Mg2+, Mn2+, and Zn2+, at physiological concentrations.

In the competition assay, wt Pop2p in the presence of Mg2+ and Mn2+ shows essentially the same degradation behavior with Generic-polyA as in the absence of the competitor, while Generic-polyC is degraded to a very limited extent during the 160-min experiment (Fig. 4D). After ∼40 min, all poly-A tails have been completely processed and the deadenylated product seems to be stabilized. Degradation of the poly-C tail is weak and only starts upon complete removal of the poly-A tails of the other substrate. Consistent with our results, it has previously been shown that S. cerevisiae Pop2p shows a subtle preference for poly-A in competition experiments (Daugeron et al. 2001). In order to assess whether the observed selectivity is restricted to the competition situation or is a general feature of the enzyme, we repeated the experiments with the isolated RNAs at the same concentration of RNA and ions (Mg + Mn) (Supplemental Fig. 1). The results are virtually indistinguishable from the competition assays, indicating that at least S. pombe Pop2p has an intrinsic poly-A selectivity and not just a subtle preference for A. The D50A mutant is completely inactive on both substrates. When the experiment was repeated using the S122A mutant, we observed the same initial behavior, namely that all full-length substrates are immediately removed. However, in this case the degradation of the Generic-polyA substrate does not pause after removal of the poly-A tail (Fig. 4E). In addition, the mutant enzyme is active on the poly-C tails, which are removed almost as fast as the poly-A tails, but also without the appearance of a partially stabilized degradation product (not shown). This clearly shows that S122 is involved in adenosine recognition as the enzyme loses the ability to distinguish between adenosine and cytidine upon mutation of the residue. Not only is the mutant able to degrade past the poly-A tail of Generic-polyA, but it will also initiate degradation of non-poly-A tails. The L125F mutant is also able to degrade both substrates, but unlike S122A, the full-length substrate persists much longer and no intermediate bands are observed. We interpret this as an increased processivity of the enzyme in the context of the L125F mutation as all encountered substrates appear to be completely degraded. This behavior is similar to what has been observed for PARN in the presence of a 5′ cap homolog, which stimulates the enzyme and increases its apparent processivity (Martinez et al. 2001). When looking at the reaction rates of the mutants in the presence of zinc (Fig. 4F), we observe no significant changes in selectivity or processivity, but note again that the enzyme becomes somewhat slower. This is consistent with the results shown above for the wt enzyme and indicates that zinc primarily alters the rate of catalysis and, to a lesser extent, the processivity and selectivity of the enzyme.

DISCUSSION

In this paper we have shown that the activity of the S. pombe deadenylation enzyme, Pop2p, is dependent on the composition of the divalent metal ions in the active site. Because the enzyme has a higher affinity for Zn2+ and Mn2+ than Mg2+, it will take up these ions from the surroundings even in the presence of up to 100-fold excess of Mg2+. By X-ray crystallography we have unambiguously shown that the A site of Pop2p can bind either Zn2+ or Mg2+ depending on the conditions but that the B site prefers to bind Mn2+ when this ion is available. The idea that the ion in the A site is variable is consistent with measured ionic radii of the elements in question, as Zn2+ and Mg2+ have very similar radii for a given number of ligands (0.74 Å and 0.74 Å for six ligands, respectively), while Mn2+ is somewhat larger (0.83 Å). Finally, we have shown that variations in the Zn2+ concentration in the range 150–250 μM cause dynamic exchange between Zn2+ and Mg2+ in position A of the active site. This raises the interesting possibility that relatively small variations in the intracellular Zn2+ concentration could alter the kinetics of deadenylation by Pop2p-type deadenylases in vivo. The amount of Zn2+ is tightly regulated in all cells by a combination of regulated uptake and efflux, controlled transport into internal zinc vacuolar storages (MacDiarmid et al. 2000), and through binding by metalloproteins that actively regulate the amount of freely available Zn2+ (Krezel and Maret 2008). Studies of the molecular effects of cellular Zn2+ fluctuations have shown that the ion is able to actively modulate the activity of some enzymes (e.g., protein tyrosine phosphatase) and several proteins involved in signaling, such as p70 S6 kinase, the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MARK), epidermal growth factor (EGF), and the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors (see Haase and Maret [2003] and references therein). Interestingly, it has also been shown that zinc-treated mammalian cells accumulate c-fos and TTP mRNAs, suggesting that zinc inhibits turnover of labile mRNAs (Taylor and Blackshear 1995). This observation is in agreement with a general model in which a high cellular concentration of zinc reduces mRNA degradation possibly by reducing the rate of deadenylation. Increased RNA turnover has likewise been demonstrated in another study where rats fed on a zinc-deficient diet were shown to exhibit reduced abundance of specific mRNAs (Stallard and Reeves 1997), which could reflect a situation where deadenylation is promoted. Recently, a comprehensive microarray study looking at global mRNA levels in S. pombe in response to zinc deficiency showed that the quantities of many mRNAs are regulated by the intracellular zinc status (Dainty et al. 2008).

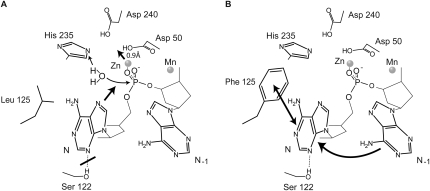

In the general two metal ion model for hydrolysis of RNA and DNA by 3′–5′ exonucleases it is usually assumed that two Mg2+ ions are involved due to the high intracellular concentration of this ion (Yang et al. 2006; Yang 2008). However, the exact active site configuration of enzymes in vivo is very difficult to address for two reasons. First, it is nearly impossible to purify the enzymes from native source without altering the composition of ions in the active site, and secondly, it is very difficult to distinguish between the various ions by classical structural methods. Our approach to these challenges has therefore been to supply the enzyme with concentrations of ions that are as close as possible to the known concentrations inside cells (Tholey et al. 1988) and observe which ions the enzyme binds. And as we have shown, the problem with identification of the ions can convincingly be dealt with using modern structural methods by analyzing the specific X-ray absorption characteristics of the various metals. Using this approach, we have clearly shown that Pop2p prefers Mn2+ or Zn2+ over Mg2+ at both its active site positions. Similarly, it has previously been shown that the proofreading domain of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I, which is a related 3′-5′ exonuclease of the DEDDy type, also has a high affinity for Zn2+ in its A site and Mn2+ in its B site (Brautigam et al. 1999). However, in this case, only two defined ions were supplied at a time, and only at millimolar concentrations, thus not addressing the question of relative affinities at physiological concentrations. Structural studies of the nuclear exosome-associated 3′-5′ exonuclease, Rrp6p, which is of the DEDDy type, showed that it was only possible to detect density in the active site for monophosphate nucleotides; the products of the reaction, when a combination of Zn2+ and Mn2+ was used during crystal soak experiments. No density was observed when Zn2+ or Mn2+ were used alone, nor with a combination of Zn2+ and Mg2+ (Midtgaard et al. 2006). This may reflect that the product is bound more tightly in the Zn2+-bound state, and therefore can be observed in the crystal, an effect which also could account for the lower exonuclease activity observed for Pop2p with these ions in vitro. Our RNA degradation assays using the S122A and L125F Pop2p mutants further showed that selectivity is not controlled directly by the nature of the ions but that the ions primarily affect the catalytic rate. We thus propose that the differences in catalytic rate observed for Mg2+ and Zn2+ are caused by differences in coordination geometry as the ion in the A site also interacts with the water molecule that carries out the nucleophilic attack on the phosphodiester backbone during the reaction (Fig. 5A). Close inspection of the two structures of Pop2p presented here shows that the Zn2+ ion in the A site is shifted ∼0.9 Å further into the active site compared to the Mg2-bound structure, which could account both for the lower reaction rate and a lower rate of release of the monophosphate product (tighter binding). To accommodate the shift, the side chains of Asp50 and Glu52 undergo concerted movements of 0.7 Å and 0.6 Å, respectively. In addition to affecting the affinity for the product nucleotide, the alteration of the active site could potentially break the interaction between the base and Ser122, hence also affecting selectivity (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5.

Mechanistic model for RNA selectivity and processivity in Pop2p. (A) The hydrolysis reaction involves activation of a water molecule by His235 for nucleophilic attack on the last phosphodiester bond (thin arrows). The last adenosine residue (N) is possibly recognized at the N3 position by Ser122. Exchange of the Mg2+ ion in the A site for Zn2+ causes a shift of the ion and concomitantly the phosphate and the last nucleotide toward Asp50 of 0.9 Å (thick arrows), potentially resulting in a slower rate of product (AMP) release. The movement would also weaken the interaction with Ser122 and therefore reduce the preference for adenosine. (B) Mutation of Leu125 to phenylalanine increases the stacking interaction with the last base (N) and reduces the importance of the Ser122 interaction. Upon hydrolysis and release of AMP in the context of the L125F mutation, the nucleotide at the new 3′ end (N−1) has higher affinity for the position occupied by the leaving nucleotide than in the wt case, accounting for the observed increase in processive behavior.

The mutation L125F had the double effect of both removing the poly-A preference and causing the enzyme to appear more processive, i.e., not dissociate between successive degradation steps. This conclusion is supported by the conservation of leucine in the distributive Pop2-type deadenylases and phenylalanine in the processive PARN-type deadenylases (Martinez et al. 2000). It is therefore quite likely that the equivalent of position 125 is one of the main determinants of processivity among the deadenylase enzymes. Our mechanistic interpretation of this result is that the large side chain of phenylalanine creates a powerful hydrophobic platform for interaction with the base plane of the 3′ nucleotide in the pre-hydrolysis state of the enzyme (Fig. 5B). Structural rearrangements upon hydrolysis are likely to destabilize this interaction and lead to release of the product nucleotide, while causing the nearby base at the new 3′ end to be “pulled” toward the aromatic side chain. In this model, the presence of the aromatic side chain reduces the likelihood that the substrate will dissociate from the active site between successive degradation steps and therefore is consistent with the observation that the enzyme appears more processive. Although S122 is conserved in PARN, it may be that the presence of the additional hydrophobic binding energy suppresses the energetic benefit of the S122-N3 interaction, thus making the enzyme less selective with respect to RNA sequence. This is supported by in vitro experiments showing that PARN is able to degrade A and U but not G and C (Martinez et al. 2000). In summary, we believe that our studies of the kinetics of wt Pop2p and the S122A and L125F mutants provide possible molecular and mechanistic explanations for both the observed subtle preference for adenosine in the two deadenylases, Pop2p and PARN, and some of the variations in processivity that these enzymes exhibit.

In our competition assays, S. pombe Pop2p showed a clear preference for adenosine over cytidine in the 3′ end of RNA substrates. The enzyme appeared to pause at the end of the poly-A stretch in the Generic-polyA substrate, but continued after prolonged incubation, showing that there is a preference for, but not a strict specificity toward, adenosine. When S122 was mutated to alanine, the enzyme lost its preference and degraded all sequences with little discrimination. Together these data may indicate that there has been only a weak evolutionary pressure toward strict poly-A specificity for the deadenylases as any deadenylated and unstructured RNAs that the enzyme will likely encounter in the eukaryotic cytoplasm are mRNAs already destined for degradation. The observation may also be related to the interplay between 3′-5′ exonucleases with different specificities found in eukaryotes. In the cytoplasm, the poly-A tail has a strongly stabilizing role through its interaction with the poly-A binding protein (PABP), while in the nucleus, attachment of a short oligo-A tail by the TRAMP polyadenylation complex serves as a mark for exosomal destruction (Andersen et al. 2008). Though many of the proteins in the eukaryotic exosome complex have exonuclease signature motifs, it has recently been shown that only two of them are in fact active, functional nucleases. It thus appears that, in the cytoplasmic exosome, the only active nuclease is the 3′-5′ hydrolytic enzyme, Rrp44p (Dis3p) (Dziembowski et al. 2007), while in the nucleus, the major nuclease activity of the exosome can be attributed to Rrp6p (Liu et al. 2006). Functional assays carried out with Rrp44p both in isolated form and in association with the exosome have shown that the cytoplasmic nuclease is not very active on poly-A substrates, while AU-rich and other substrates are readily degraded (Liu et al. 2006). Conversely, the nuclear exonuclease, Rrp6p, is highly active on poly-A substrates, while less active on generic RNA sequences. The combined results from studies of the exosome and the deadenylation enzymes therefore suggest that, while the adenosine specificity of Rrp6p is consistent with the poly-A tail as a mark for destruction in the nucleus, the lack of poly-A activity of the cytoplasmic Rrp44p fits well with the observation that specific deadenylation enzymes are required for removing the poly-A tail from mRNAs. In other words, the cytoplasmic exosome will not initiate 3′-5′ degradation of mRNAs unless the poly-A tail has been completely removed by the rate-limiting deadenylation step. A strong poly-A specificity of the deadenylases may therefore not be required, and the high speed with which the exosome processes non-poly A RNA probably means that the presence of nonspecific deadenylases will not affect the process. This idea emphasizes the importance of deadenylation reaction in the control of the overall gene expression pathway where variations in the cellular Zn2+ levels could be one of several ways of regulating the overall rate of mRNA turnover.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In vitro deadenylation assays

Full-length wt and D50A preparations of Pop2p from S. pombe were purified as described previously (Jonstrup et al. 2007). The S122A and L125F mutants were constructed by site-directed mutagenesis using the primers 5′-ATGTACGCTCCGGAAGCCATAGAGTTACTCAC-3′ (sense, underlined = mutation) and 5′-GAGTAACTCTATGCTGAGCGGAGCGTACATATC-3′ (anti-sense) for S122A, and 5′-GGAAAGCATAGAGTTCCTCACAAAAAGTGGC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GCCACTTTTTGTGAGGAACTCTATGCTTTCC-3′ (anti-sense) for L125F, and confirmed by sequencing. The availability of divalent cations was controlled by performing the final gel filtration step in defined buffers containing 50 mM Tris-Cl at pH 8.0, 100 mM KCl, and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol in addition to the required combinations of 7.1 mM Mg2+, 75 μM Mn2+, and/or 220 μM Zn2+. The RNA substrates, Generic-polyA (5′-CAGCUCCGCAUCCCUUUCCCAAAAAAAAAA-3′) (Invitrogen) and Generic-polyC (5′-CAGCUCCGCAUCCCUUUCCCCCCCCCCCCC-3′) (Dharmacon), were synthesized with either a fluorescein or a 5-carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA) group covalently attached to the 5′ end and gel-purified. All in vitro reactions contained a 50-fold excess of enzyme (0.5 μM) over RNA (10 nM) and were carried out in 10 mM Tris-Cl at pH 8.0, 50 mM KCl and 7.1 mM Mg2+, 75 μM Mn2+, and/or 220 μM Zn2+ as appropriate. The requirement for a large excess of enzyme is thought to be a result of very low specific activity as the activity would quickly diminish over time following the purification and storage on ice. This assumption is also supported by the observation that, in several experiments, the full-length product persisted for a long time, which would not be the case if an excess of enzymes were fully active. To allow comparison, all experiments were done with freeze stocks of enzyme of comparable activity. Reactions were allowed to proceed at 30°C for the required amount of time after which they were quenched with RNA loading buffer, separated by denaturing gel electrophoresis in 20% urea-acrylamide gels running at 15 W (Bio-Rad), and visualized using a Typhoon Trio imager (GE Healthcare). The RNA ladder was constructed by limited alkaline hydrolysis of the Generic-polyA RNA by incubation in 50 mM NaCO3 at pH 8.9 for 10 min at 96°C followed by neutralization with 300 mM Na(CH3COO) at pH 4.5. For the titration experiments, Pop2p was first changed into a buffer containing 7.1 mM Mg2+ and 75 μM Mn2+ by gel filtration. The concentration of these ions was kept constant in a subsequent series of experiments with increasing Zn2+ concentrations (0, 50, 150, 220, 300, 500, or 1000 μM) in a constant reaction volume. In the second titration series, Pop2p was first changed into a buffer with 75 μM Mn2+ and 220 μM Zn2+ and diluted in the reactions to final concentrations of 7.5 μM Mn2+ and 22 μM Zn2+, while Mg2+ was added in increasing concentrations (0, 50, 150, 220, 300, 500, and 1000 μM) still in a constant total volume. Data quantification was carried out using ImageJ (Rasband 1997–2008; Abramoff et al. 2004) by integrating the intensity of either the full-length band or the fully deadenylated product, normalized by the total intensity in each lane. The bands <20 nt were included in the integration when estimating the amount of fully deadenylated product, i.e., the values for fully deadenylated product represent the fraction of RNAs which were ≤20 nt.

Crystallization

The protein used for crystallization of Pop2p at physiological concentrations of all three ions was equilibrated into a buffer containing 100 mM KCl, 50 mM Tris-Cl at pH 8.0, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 7.1 mM Mg2+, 75 μM Mn2+, and 220 μM Zn2+ on a gel filtration column and concentrated to 5–10 mg/mL by spin filtration. Crystallization was achieved by the sitting drop vapor diffusion technique by mixing 1 μL protein solution and 1 μL reservoir solution (18% PEG 3350, 200 mM sodium formate, and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol) and equilibrating against a 400 μL reservoir at 4°C. Single crystals grew to full size (100–200 μm) within one week at these conditions. Crystals were cryo-protected by stepwise transfer into solutions containing 20%–30% PEG 3350 before flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen. Crystals used to visualize the Zn-deficient state were grown in 18% PEG 8000, 200 mM magnesium acetate, and 100 mM MES at pH 6.5, as described previuosly (Jonstrup et al. 2007). Preformed crystals were then soaked for 2 h in a buffer containing 18% PEG 8000, 200 mM K(CH3COO), 100 mM MES at pH 6.5, 7.1 mM Mg2+, and 75 μM Mn2+ before cryo-protection.

Data collection and structure determination

For both structures, complete and highly redundant data sets were collected on single crystals at the I911-3 MAD beam line at MAX-Lab at both 1.271 Å and 1.297 Å (Table 1). The crystals belong to the orthorhombic space group P212121 with one molecule in the asymmetric unit and diffract at best to 1.4 Å (Jonstrup et al. 2007). Diffraction data were integrated using HKL2000 (Otwinowski and Minor 1997). Data from crystals grown under physiological concentrations of ions extended to 2.1 Å for the first data set collected at 1.271 Å, and to 2.6 Å for the second data set collected at 1.297 Å, due to radiation damage. The two data sets collected from the crystals grown in the absence of zinc were processed to 2.6 Å and 2.7 Å, respectively. The structures were determined by molecular replacement using the known structure of S. pombe Pop2p (PDB ID 2P51) and the program Phaser by removing side chains, solvent, and ions (McCoy et al. 2007). Anomalous differences calculated for both pairs of data sets were used in the Fourier transform using the program FFT (Collaborative Computational Project 1994). Structure refinement was carried out iteratively with the program Phenix (Adams et al. 2002) with manual rebuilding in Coot (Table 1; Emsley and Cowtan 2004).

Coordinates

The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession codes 3G0Z (Zn, Mn-bound) and 3G10 (Mg, Mn-bound).

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material can be found at http://www.rnajournal.org.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank MAX-Lab and Dr. Thomas Ursby at I911-3 for help during data collection and Dr. Simon Whitehall at Newcastle University, for helpful discussions concerning the cellular effects of zinc in S. pombe. The work was supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation. A.T.J. was supported by post-doctoral fellowships from The Lundbeck Foundation and The Carlsberg Foundation and K.R.A. was supported by a Ph.D. program grant from The Danish National Research Foundation, Centre for mRNP Biogenesis and Metabolism.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.1489409.

REFERENCES

- Abramoff M.D., Magelhaes P.J., Ram S.J. Image processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics Int. 2004;11:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Adams P.D., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Hung L.W., Ioerger T.R., McCoy A.J., Moriarty N.W., Read R.J., Sacchettini J.C., Sauter N.K., Terwilliger T.C. PHENIX: Building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2002;58:1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert T.K., Lemaire M., van Berkum N.L., Gentz R., Collart M.A., Timmers H.T. Isolation and characterization of human orthologs of yeast CCR4-NOT complex subunits. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:809–817. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.3.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen K.R., Jensen T.H., Brodersen D.E. Take the “A” tail—Quality control of ribosomal and transfer RNA. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1779:532–537. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y., Salvadore C., Chiang Y.C., Collart M.A., Liu H.Y., Denis C.L. The CCR4 and CAF1 proteins of the CCR4-NOT complex are physically and functionally separated from NOT2, NOT4, and NOT5. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:6642–6651. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.6642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beese L.S., Steitz T.A. Structural basis for the 3′-5′ exonuclease activity of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I: A two metal ion mechanism. EMBO J. 1991;10:25–33. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07917.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchin C., Mauxion F., Sentis S., Seraphin B., Corbo L. Conservation of the deadenylase activity of proteins of the Caf1 family in human. RNA. 2005;11:487–494. doi: 10.1261/rna.7135305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brautigam C.A., Sun S., Piccirilli J.A., Steitz T.A. Structures of normal single-stranded DNA and deoxyribo-3′-S-phosphorothiolates bound to the 3′-5′ exonucleolytic active site of DNA polymerase I from Escherichia coli . Biochemistry. 1999;38:696–704. doi: 10.1021/bi981537g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Rappsilber J., Chiang Y.C., Russell P., Mann M., Denis C.L. Purification and characterization of the 1.0 MDa CCR4-NOT complex identifies two novel components of the complex. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;314:683–694. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Chiang Y.C., Denis C.L. CCR4, a 3′-5′ poly(A) RNA and ssDNA exonuclease, is the catalytic component of the cytoplasmic deadenylase. EMBO J. 2002;21:1414–1426. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.6.1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4. The CCP4 suite: Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dainty S.J., Kennedy C.A., Watt S., Bahler J., Whitehall S.K. Response of Schizosaccharomyces pombe to zinc deficiency. Eukaryot. Cell. 2008;7:454–464. doi: 10.1128/EC.00408-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugeron M.C., Mauxion F., Seraphin B. The yeast POP2 gene encodes a nuclease involved in mRNA deadenylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2448–2455. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.12.2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziembowski A., Lorentzen E., Conti E., Seraphin B. A single subunit, Dis3, is essentially responsible for yeast exosome core activity. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:15–22. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P., Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstrohm A.C., Wickens M. Multifunctional deadenylase complexes diversify mRNA control. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:337–344. doi: 10.1038/nrm2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase H., Maret W. Intracellular zinc fluctuations modulate protein tyrosine phosphatase activity in insulin/insulin-like growth factor-1 signaling. Exp. Cell Res. 2003;291:289–298. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00406-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob C., Maret W., Vallee B.L. Control of zinc transfer between thionein, metallothionein, and zinc proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998;95:3489–3494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonstrup A.T., Andersen K.R., Van L.B., Brodersen D.E. The 1.4-Å crystal structure of the S. pombe Pop2p deadenylase subunit unveils the configuration of an active enzyme. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3153–3164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krezel A., Maret W. Thionein/metallothionein control Zn(II) availability and the activity of enzymes. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2008;13:401–409. doi: 10.1007/s00775-007-0330-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Greimann J.C., Lima C.D. Reconstitution, activities, and structure of the eukaryotic RNA exosome. Cell. 2006;127:1223–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDiarmid C.W., Gaither L.A., Eide D. Zinc transporters that regulate vacuolar zinc storage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . EMBO J. 2000;19:2845–2855. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.12.2845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez J., Ren Y.G., Thuresson A.C., Hellman U., Astrom J., Virtanen A. A 54-kDa fragment of the poly(A)-specific ribonuclease is an oligomeric, processive, and cap-interacting poly(A)-specific 3′ exonuclease. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:24222–24230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001705200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez J., Ren Y.G., Nilsson P., Ehrenberg M., Virtanen A. The mRNA cap structure stimulates rate of poly(A) removal and amplifies processivity of degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:27923–27929. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102270200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy A.J., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Adams P.D., Winn M.D., Storoni L.C., Read R.J. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midtgaard S.F., Assenholt J., Jonstrup A.T., Van L.B., Jensen T.H., Brodersen D.E. Structure of the nuclear exosome component Rrp6p reveals an interplay between the active site and the HRDC domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006;103:11898–11903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604731103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z., Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. In: Carter C.W. Jr, Sweet R.M., editors. Methods in enzymology: Macromolecular crystallography, part A. Vol. 276. Academic Press; New York: 1997. pp. 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker R., Song H. The enzymes and control of eukaryotic mRNA turnover. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:121–127. doi: 10.1038/nsmb724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasband W.S. ImageJ. U.S. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD: 1997–2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stallard L., Reeves P.G. Zinc deficiency in adult rats reduces the relative abundance of testis-specific angiotensin-converting enzyme mRNA. J. Nutr. 1997;127:25–29. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steitz T.A., Steitz J.A. A general two-metal-ion mechanism for catalytic RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1993;90:6498–6502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor G.A., Blackshear P.J. Zinc inhibits turnover of labile mRNAs in intact cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 1995;162:378–387. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041620310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tholey G., Ledig M., Mandel P., Sargentini L., Frivold A.H., Leroy M., Grippo A.A., Wedler F.C. Concentrations of physiologically important metal ions in glial cells cultured from chick cerebral cortex. Neurochem. Res. 1988;13:45–50. doi: 10.1007/BF00971853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thore S., Mauxion F., Seraphin B., Suck D. X-ray structure and activity of the yeast Pop2 protein: A nuclease subunit of the mRNA deadenylase complex. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:1150–1155. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker M., Valencia-Sanchez M.A., Staples R.R., Chen J., Denis C.L., Parker R. The transcription factor associated Ccr4 and Caf1 proteins are components of the major cytoplasmic mRNA deadenylase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Cell. 2001;104:377–386. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00225-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker M., Staples R.R., Valencia-Sanchez M.A., Muhlrad D., Parker R. Ccr4p is the catalytic subunit of a Ccr4p/Pop2p/Notp mRNA deadenylase complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . EMBO J. 2002;21:1427–1436. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.6.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M., Reuter M., Lilie H., Liu Y., Wahle E., Song H. Structural insight into poly(A) binding and catalytic mechanism of human PARN. EMBO J. 2005;24:4082–4093. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W. An equivalent metal ion in one- and two-metal-ion catalysis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:1228–1231. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., Lee J.Y., Nowotny M. Making and breaking nucleic acids: Two-Mg2+-ion catalysis and substrate specificity. Mol. Cell. 2006;22:5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]