Introduction

The protein SO4266 (gi|24375750) from the bacterium Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 is annotated as a member of Pfam PF02661. This family consists of Fic (filamentation induced by cAMP) proteins and their relatives, and is characterized by the presence of a well-conserved HPFXXGNG motif 1. The biochemistry of Fic proteins has not been characterized extensively and their exact molecular functions remain unknown. From early studies in Escherichia coli, it is believed that Fic proteins and cAMP may be involved in a regulatory mechanism of cell division, including folate metabolism by the synthesis of p-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) or folate 1. Proteins containing the Fic domain are present in all kingdoms of life and range in size from ~200 to 500 amino acids. The Fic protein family contains 647 members, including two human proteins, according to Pfam (May 2008). Sequence-based clustering 2 of this protein family, at 30% sequence identity, groups these proteins into 18 clusters. Three crystal structures of Fic proteins from bacteria (unpublished) are available in the Protein Data Bank [accession codes 2g03 (194 residues, 2.2 Å), 2f6s (201 residues, 2.5 Å) and 3cuc (262 residues, 2.7 Å)]. The first two of these proteins belong to a single cluster of 16 members and share ~60% sequence identity. The anti-apoptotic bacterial effector protein BepA, which is a type IV secretion (T4S) system substrate, also contains an N-terminal Fic domain 3. In humans, the Fic domain is present in the Huntingtin Interacting Protein E (HYPE; Uniprot entry Q9BVA6_HUMAN), a protein of unknown function that is thought to interact with Huntingtin, one of the major proteins in the Huntington's disease protein interaction network (listed as NAD- or FAD-binding) 4. Bioinformatics analysis of prokaryotic toxin-antitoxin networks 5 suggests that Fic proteins are putative death-on-curing (Doc) toxins that are part of the Phd-Doc system. These proteins likely function as metal-dependent nucleases or RNA-processing enzymes, 5 while more recent studies suggest that Doc toxicity is caused by inhibition of translation elongation 6. SO4266 (Uniprot entry Q8E9K5_SHEON), at 372 amino acids, is one of the largest Fic domain-containing proteins to have its structure determined. Interestingly, both HYPE and SO4266 belong to the largest sequence cluster in this family (n.b. our B. thetaiotaomicron NP_811426.1 structure with PDB id 3cuc also belongs to this cluster), which comprises 466 out of 647 proteins, and share ~32% sequence identity in the Fic domain.

Here, we report the crystal structure of the SO4266 protein at 1.6 Å resolution. The structure reveals a dimeric protein with additional electron density in the vicinity of the highly conserved HPFXXGNG motif in the Fic domain of one subunit that corresponds to the N-terminus of a symmetry-related molecule. In addition, the study also reveals a C-terminal winged-helix DNA-binding domain that sets it apart from the other Fic protein structures. The structure presented here is a representative of the largest sequence cluster and together with the structures of the other Fic proteins paves the way for further structure-based functional characterization.

Materials and Methods

Protein production and crystallization

The S. oneidensis MR-1 SO4266 gene (GenBank: NP_719793.1, GI:24375750) was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from genomic DNA (ATCC: 700550D) using PfuTurbo (Stratagene) and primers corresponding to the predicted 5' and 3' ends. The PCR product was cloned into plasmid pSpeedET, which encodes an expression and purification tag followed by a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavage site (MGSDKIHHHHHHENLYFQG) at the amino terminus of the full-length protein. LC-MS reveals a Cys at position 109, and DNA sequencing indicates a TGC codon. However, the published sequence for SO4266 from strain MR-1 shows a Gly (GGC codon) at this position. It is not clear if this discrepancy is a PCR artifact. The cloning junctions were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Protein expression was performed in a selenomethionine-containing medium using the Escherichia coli strain GeneHogs (Invitrogen). At the end of fermentation, lysozyme was added to the culture to a final concentration of 250 μg/mL, and the cells were harvested. After one freeze/thaw cycle, the cells were homogenized in Lysis Buffer [50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 1 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP)] and passed through a Microfluidizer (Microfluidics). The lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 32,500 × g for 30 min and loaded onto nickel-chelating resin (GE Healthcare) preequilibrated with Lysis Buffer. The resin was washed with Wash Buffer [50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 40 mM imidazole, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mM TCEP], and the protein was eluted with Elution Buffer [20 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 300 mM imidazole, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mM TCEP]. The eluate was buffer exchanged with HEPES Crystallization Buffer [20 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 40 mM imidazole, 1 mM TCEP] using a PD-10 column (GE Healthcare) and treated with 1 mg of TEV protease per 15 mg of eluted protein. The digested eluate was passed over nickel-chelating resin (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated with HEPES Crystallization Buffer, and the resin was washed with the same buffer. The flow-through and wash fractions were combined and concentrated for crystallization assays to 12.4 mg/mL by centrifugal ultrafiltration (Millipore). SO4266 was crystallized using the nanodroplet vapor diffusion method 7 with standard JCSG crystallization protocols 8. Screening for diffraction was carried out using the Stanford Automated Mounting system (SAM) 9 at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL, Menlo Park, CA). The crystallization reagent that produced the crystal used for structure solution contained 0.2 M NaF and 20% (w/v) polyethylene glycol (PEG) 3350 at pH 7.1. PEG 200 was added as a cryoprotectant to the crystal to a final concentration of 15% (v/v). The crystal was indexed in orthorhombic space group P212121 (Table I) 10,11. The molecular weight and oligomeric state of SO4266 were determined using a 1 cm × 30 cm Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare) in combination with static light scattering (Wyatt Technology). The mobile phase consisted of 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.02% (w/v) sodium azide.

Table I.

Summary of crystal parameters, data collection and refinement statistics for PDB 3eqx.

| Space group | P 212121 | ||

| Unit cell parameters | a=71.21Å, b=80.30Å, c=141.00Å | ||

| Data collection | λ1 MAD Se | λ2 MAD Se | λ3 MAD Se |

| Wavelength(Å) | 0.91837 | 0.97905 | 0.97935 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 29.6-1.60 | 29.6-1.60 | 29.5-1.60 |

| Number of observations | 373,102 | 367,969 | 369,908 |

| Number of unique reflections | 106,471 | 106,307 | 106,407 |

| Completeness (%) | 98.7 (98.7)a | 98.0 (99.2) | 98.6 (98.2) |

| Mean I/σ (I) | 13.8 (2.0)a | 16.6 (2.6) | 12.5 (1.9) |

| Rsym on I (%) | 4.2 (52.4)a | 3.3 (39.0) | 4.4 (51.9) |

| Highest resolution shell (Å) | 1.66-1.60 | 1.66-1.60 | 1.66-1.60 |

| Model and refinement statistics | |||

| Resolution range (Å) | 29.6-1.60 | Data set used in refinement | λ 1 |

| No. of reflections (total) | 106,418b | Cutoff criteria | |F|>0 |

| No. of reflections (test) | 5,304 | Rcryst | 0.168 |

| Completeness (%total) | 99.3 | Rfree | 0.197 |

| Stereochemical parameters | |||

| Restraints (RMS observed) | |||

| Bond angle (°) | 1.64 | ||

| Bond length (Å) | 0.018 | ||

| Average isotropic B-value (Å2) | 16.9 | ||

| ESU based on Rfree (Å) | 0.08 | ||

| Protein residues / atoms | 731/6,005 | ||

| Water / PGE molecules | 814/1 | ||

Highest resolution shell

ESU = Estimated overall coordinate error 10,11.

Rsym =Σ|Ii-<Ii>|/Σ|Ii|, where Ii is the scaled intensity of the ith measurement and <Ii> is the mean intensity for that reflection.

Rcryst = Σ||Fobs|-|Fcalc||/Σ|Fobs|, where Fcalc and Fobs are the calculated and observed structure factor amplitudes, respectively.

Rfree = as for Rcryst, but for 5.0% of the total reflections chosen at random and omitted from refinement.

Typically, the number of unique reflections used in refinement is slightly less that the total number that were integrated and scaled. Reflections are excluded due to systematic absences, negative intensities, and rounding errors in the resolution limits and cell parameters.

Data collection, structure solution, and refinement

Multi-wavelength anomalous diffraction (MAD) data were collected at SSRL on beamline 11-1 at wavelengths corresponding to the high energy remote (λ1), peak (λ2) and inflection point (λ3) of a selenium MAD experiment using the BLU-ICE 12 data collection environment. The data sets were collected at 100K using a MarMosaic 325 CCD detector (Mar USA). The MAD data were integrated and reduced using XDS 13 and scaled with the program XSCALE. The heavy atom substructure was solved and sites were refined using SOLVE 14. Density modification was performed with RESOLVE 15 and ARP/wARP 16 was used for automatic model building. Model completion and crystallographic refinement were performed with the λ1 data set using COOT 17 and REFMAC5 10, respectively. Data and refinement statistics are summarized in Table I 10,11.

Validation and deposition

The quality of the crystal structure was analyzed using the JCSG Quality Control server. This server verifies: the stereochemical quality of the model using AutoDepInputTool 18, MolProbity 19, and WHATIF 5.0 20; agreement between the atomic model and the data using SFcheck 4.0 21 and RESOLVE 15, the protein sequence using CLUSTALW 22, atom occupancies using MOLEMAN2 23, consistency of NCS pairs, and evaluates difference in Rcryst/Rfree, expected Rfree/Rcryst and maximum/minimum B-factors by parsing the refinement log-file and PDB header. Protein quaternary structure analysis was performed using the PISA server 24. Figure 1(B) was adapted from an analysis using PDBsum 25, and all others were prepared with PyMOL 26. Atomic coordinates and experimental structure factors for Fic from S. oneidensis MR-1 to 1.6 Å resolution were deposited in the PDB under the accession code 3eqx.

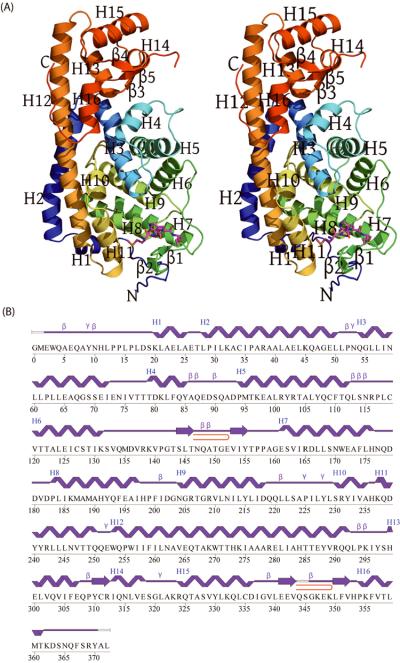

Figure 1.

A) Stereo representation of the crystal structure of the chain A monomer of the SO4266 protein. The peptide modeled as `MEWQ' corresponds to residues 1-4 of the crystallographic symmetry-related B chain and is shown in ball-and-stick. B) Diagram showing the secondary structure elements of SO4266 superimposed on the primary amino acid sequence. The helices, β-strands, γ-turns, and β-turns are indicated. The β-hairpins are indicated as red loops. Residues absent from the monomer A (G0, M1, Q344, S345, A371 and L372) are indicated by lack of a secondary structure trace.

Results and Discussion

The crystal structure of SO4266 [Fig. 1(A)] was determined by MAD phasing to a resolution of 1.6 Å. The final model contains 2 monomers, 814 waters and 1 PGE molecule in the asymmetric unit (ASU). This dimer is the likely oligomeric association as judged from crystal lattice packing and assembly analysis using PISA 24, as well as size exclusion chromatography coupled with static light scattering. Residues A1, A344-A345, A371-A372, B5-B10, and B370-B372 (A and B refer to the chain identifier) and N-terminal glycine left after cleavage of the expression and purification tag were disordered and not modeled. The Matthews' coefficient 27 is 2.4 Å3/Da, with an estimated solvent content of 48.4%. The Ramachandran plot produced by Molprobity 19 shows that 98.9% and 100 % of amino acids are in the favored and allowed regions, respectively.

The secondary structure of this 372-amino acid protein is primarily α-helical (65%), with 16 α-helices (H1-H16) (Fig. 1). Each monomer of SO4266 assumes an overall shape resembling a closed fist, with a back-to-back association of the monomers forming a `transcription factor-like' dimer (Fig. 2). The core of the Fic domain consist of residues 100-290 (Fig. 2, magenta), with a long, mostly α-helical insert region at the N-terminus (1-100; Fig. 2, blue) that is involved in dimerization. Residues 290-370 of the C-terminus form a winged helix-turn-helix DNA-binding domain (Fig. 2, green) similar to that seen in several transcriptional regulators 28,29(e.g. PDB id 2d1h).

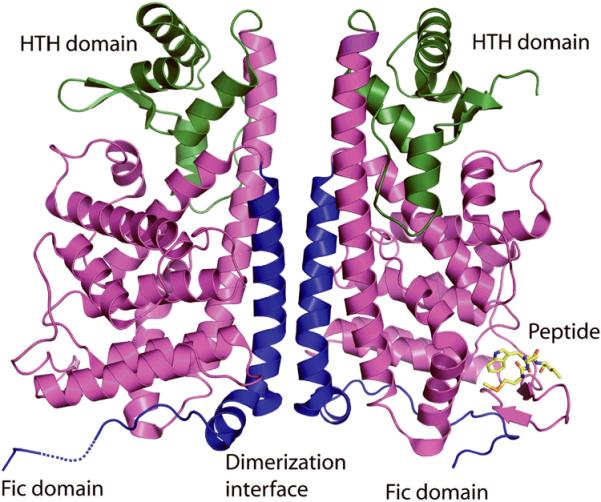

Figure 2.

The monomers of SO4266 assume a closed fist-like shape, with a back-to-back association of the monomers forming a “transcription factor-like” dimer. The core of the Fic domain is made up of residues 100-290 (magenta), with a long, mostly α-helical insert region at the N-terminus (residues 1-100; blue) that is involved in dimerization. Residues 290-370 of the C-terminus form a winged helix-turn-helix (wHTH) DNA-binding domain (green) similar to that seen in several transcriptional regulators (e.g. PDB id 2d1h). The peptide `MEWQ' bound to chain A that corresponds to residues 1-4 of the crystallographic symmetry-related B chain is shown (yellow).

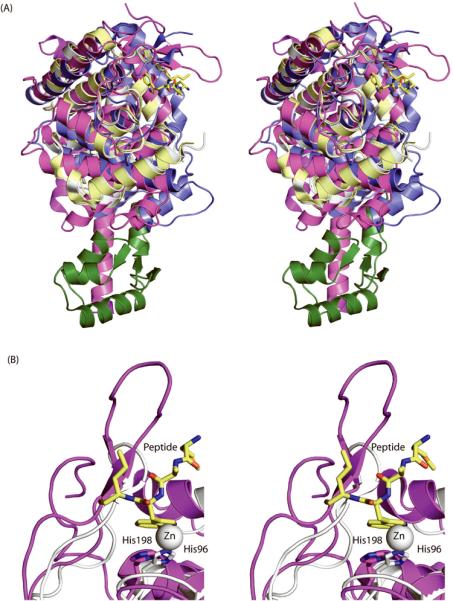

Three other crystal structures of Fic family proteins (unpublished, coordinates deposited in the PDB under accession codes 2g03, 2f6s and 3cuc) from Neisseria meningitidis (194 residues), Helicobacter pylori (201 residues) and Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron vpi- 5482 (262 residues) have been determined recently. The comparison of chain A of SO4266 (magenta) with these proteins (2g03, yellow, 2f6s, grey and 3cuc, blue) reveals the similarity in their overall structures (Fig. 3A). These structures can be superimposed onto SO4266 with Z-scores of 10.5, 10.4 and 18.5 (DaliLite 30) and RMSDs of 3.1 Å, 3.2 Å and 2.8 Å, with sequence identities of 12%, 14% and 16%, respectively. The C-terminal DNA binding domain in SO4266 (Fig 3A, green) is not present in the other Fic protein crystal structures.

Figure 3.

A) Superimposition of the SO4266 monomers (magenta and green) with the Fic family proteins from Neisseria meningitidis (194 residues, 2g03, yellow), Helicobacter pylori (201 residues, 2f6s, grey) and Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron vpi-5482 (262 residues, 3cuc, blue), reveal the similarity in their structures despite the absence of the C-terminal domain of SO4266 (green) in the other Fic proteins. They align on SO4266 with RMSDs of 3.1 Å, 3.2 Å and 2.8 Å, Z-scores of 10.5, 10.4 and 18.5 (DaliLite), and sequence identities of 12%, 14% and 16%, respectively. The peptide is shown (yellow ball-and-stick). B) The structure of the H. pylori Fic protein (grey) contains a zinc ion (grey) interacting with His 96 of the conserved HPFXXGNG motif. In the structure of SO4266 (magenta), the tryptophan residue of the peptide (yellow ball-and-stick) partially overlaps with the location of the Zn2+ ion and it is unlikely that the protein can bind metal and the peptide at the same time (grey).

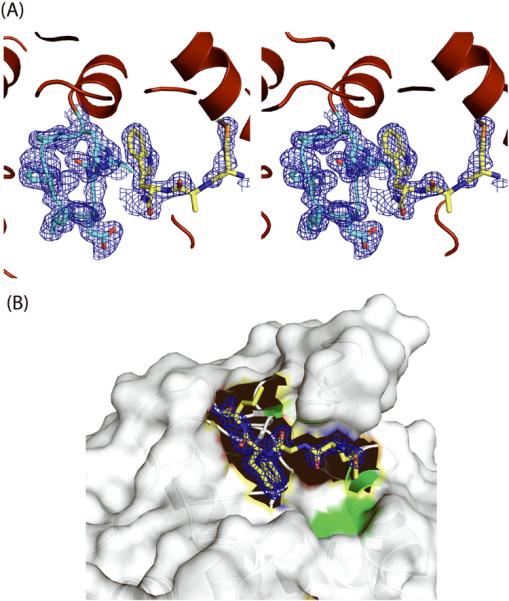

The experimentally phased maps of SO4266 revealed two regions of electron density near the HPFXXGNG motif in chain A. The first section of density, within interaction distance of the His198 of the Fic motif, was identified as the N-terminal region of a crystallographic symmetry-related copy of chain B comprised of residues MEWQ (B1-B4) based on a peak for a selenium atom position of the MSE 1 in the anomalous difference Fourier map and prominent density for a tryptophan (Trp 3). The N-terminal residues of chain B are still likely attached to the rest of the chain, but residues B5-B10 are not observed in the electron density due to disorder and, hence, are not modeled. Modeling experiments suggest that an analog of a folate derivative (COE: Furo[2,3D]Pyrimidine Antifolate), which could be relevant for a Fic family protein, may also approximately fit this density, but the fit is not as reliable as that for the N-terminal B1-B4 residues. Although the interaction of the N-terminal region B1-B4 with the HPFXXGNG site is due to crystal packing and not a likely autoinhibitory function, its presence near the Fic motif may hint at biologically important interactions with ligands and how COE may bind (Fig 3B). The N-terminus of chain B located at the putative binding site of chain A is depicted in Fig. 4A in the initial electron density map at 1.0σ obtained by the density modification of experimental phases. One of the most prominent portions of this density is the tryptophan facing the aromatic ring of His198 (the HPFXXGNG motif spans the region between helices H8 and H9) in chain A. This feature appears to be consistent with classification of the human Fic protein HYPE as NAD- or FAD-binding. The biological relevance of a bound peptide is unclear, but it may mimic natural ligands of the protein and reflect biochemically important interactions of the HPFXXGNG motif. The interaction distance of ~3.6 Å makes it suited for an aromatic ring stacking interaction. The rest of the N-terminal peptide runs almost parallel to residues 143-148 in chain A (at a distance of ~3.0-5.0 Å), which form part of a β-hairpin between helices H6 and H7. This β-hairpin has a different conformation in the other “unliganded” monomer. This region of the protein forms a lid over the binding cleft. Other than this lid, the binding cleft is enclosed between helices H8, H9, and H11. Despite the strong structural similarity between these Fic proteins, the region forming the binding cleft lid is about seven residues longer in SO4266 and in a different conformation. Analysis of the surface rendering of the crystal structure indicates that this peptide is positioned in the most prominent surface cleft (Fig. 4B). The second region of additional electron density in chain A is in a surface-exposed hydrophobic cleft surrounded by Thr248, Leu244, Tyr241, Leu145, Tyr155, and Leu245 and near the previous electron density. These neighboring amino acids are mapped as a yellow patch in Fig. 4B. A PGE (triethylene glycol) molecule which may be a fragment of PEG in the crystallization condition has been modeled into this density.

Figure 4.

A) Density modified electron density map from experimental phases at 1.0 σ with the N-terminal B1-B4 peptide sequence `MEWQ' (yellow) modeled near the HPFXXGNG motif (cyan) in SO4266, with the tryptophan facing and within interaction distance to His198. B) A surface rendering of the most prominent cleft in SO4266, with the B1-B4 peptide shown (`MEWQ', yellow). The rest of the peptide is close to residues 143-148 of chain A, which forms part of a β-hairpin between helices H6 and H7. This region of the protein forms a lid over the binding cleft. In addition to this lid, the binding cleft is situated between helices H8, H9, and H11. The green region corresponds to Thr248, Leu244, Tyr241, Leu145, Tyr155, and Leu245 that are proximal to the other extra electron density that was modeled as a PGE molecule from the crystallization condition.

Inspection of the genomic context of the SO4266 gene reveals that it is positioned between the genes for the restriction or endonuclease (R) and the methylase (M) subunits of the Type 1 Restriction Modification (RMS) system similar to that of a previously reported study of the presence of a Phd (antidote; prevent host death)-Doc (toxin death on cure) module 31 in a type IC hsd loci in enterobacteria 32. So far, evidence for a possible transcriptional regulation of the Type 1 RMS systems has remained elusive despite belief that such a mechanism should exist 32-35. Doc-like toxins of the prokaryotic toxin-antitoxin networks have been suggested to function as metal-dependent nucleases or RNA-processing enzymes 5. Indeed, the structure of the Fic protein from H. pylori (PDB 2f6s) contains a zinc-binding site with the zinc ion chelated by His96 of the conserved HPFXXGNG motif (Fig. 3B). However, in SO4266 structure, the tryptophan side-chain of the bound peptide overlaps with the location of the Zn2+ ion and it is unlikely that the protein can bind metal and ligand simultaneously. Structural analysis reveals that the distance between the C-terminal winged helix-turn-helix DNA-binding domains in the SO4266 dimer may be suitable for accommodating dsDNA (Figs. 1 and 2).

Taken together, the results presented here tempt us to speculate that the SO4266 protein may have a role in the regulation of the Type 1 RMS genes and possibly also possess metal-dependent, nuclease activity. However, the Phd gene, which is usually found next to the Doc gene, is not present in S. oneidensis. Therefore, it is possible that there are additional roles for these proteins.

The primary goal of the PSI is to efficiently expand the coverage of protein fold space and to target large protein superfamilies for structural characterization. During target selection, we focus on proteins that are essential for fundamental biological processes and have a broad phylogenetic distribution. The crystal structure presented here provides important information about potential structure-function relationships in Fic proteins. The presence of electron density near the signature motif of this family indicates the possibility of this being the functionally relevant ligand binding site. The presence of a C-terminal DNA binding domain and genomic context indicates that this protein may be involved in transcriptional regulation of its neighboring genes. Mechanistic and mutagenesis studies based on our structure should confirm and elucidate residues important for molecular function and substrate specificity and advance our knowledge of the precise function of Fic proteins. Furthermore, detailed structural and biochemical knowledge of Fic proteins in bacteria and extension to human Fic proteins may lead to cellular pathway interventions of therapeutic value.

The JCSG has developed The Open Protein Structure Annotation Network (TOPSAN), a wiki-based community project to collect, share, and distribute information about protein structures determined at PSI centers. TOPSAN offers a combination of automatically generated, as well as comprehensive, expert-curated annotations, provided by JCSG personnel and members of the research community. Additional information about SO4266 is available at http://www.topsan.org/explore?PDBid=3eqx

Acknowledgements

Portions of this research were performed at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL). The SSRL is a national user facility operated by Stanford University on behalf of the United States Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health (National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences or the National Institutes of Health. Genomic DNA from Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 (ATCC Number: 700550D) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC).

Grant Sponsor: National Institute of General Medical Sciences, Protein Structure Initiative; Grant Number: U54 GM074898.

References

- 1.Komano T, Utsumi R, Kawamukai M. Functional analysis of the fic gene involved in regulation of cell division. Res Microbiol. 1991;142:269–277. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(91)90040-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li W, Godzik A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1658–1659. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmid MC, Scheidegger F, Dehio M, Balmelle-Devaux N, Schulein R, Guye P, Chennakesava CS, Biedermann B, Dehio C. A translocated bacterial protein protects vascular endothelial cells from apoptosis. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e115. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark HF, Gurney AL, Abaya E, Baker K, Baldwin D, Brush J, Chen J, Chow B, Chui C, Crowley C, Currell B, Deuel B, Dowd P, Eaton D, Foster J, Grimaldi C, Gu Q, Hass PE, Heldens S, Huang A, Kim HS, Klimowski L, Jin Y, Johnson S, Lee J, Lewis L, Liao D, Mark M, Robbie E, Sanchez C, Schoenfeld J, Seshagiri S, Simmons L, Singh J, Smith V, Stinson J, Vagts A, Vandlen R, Watanabe C, Wieand D, Woods K, Xie MH, Yansura D, Yi S, Yu G, Yuan J, Zhang M, Zhang Z, Goddard A, Wood WI, Godowski P, Gray A. The secreted protein discovery initiative (SPDI), a large-scale effort to identify novel human secreted and transmembrane proteins: a bioinformatics assessment. Genome Res. 2003;13:2265–2270. doi: 10.1101/gr.1293003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anantharaman V, Aravind L. New connections in the prokaryotic toxin-antitoxin network: relationship with the eukaryotic nonsense-mediated RNA decay system. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R81. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-12-r81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu M, Zhang Y, Inouye M, Woychik NA. Bacterial addiction module toxin Doc inhibits translation elongation through its association with the 30S ribosomal subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5885–5890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711949105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santarsiero BD, Yegian DT, Lee CC, Spraggon G, Gu J, Scheibe D, Uber DC, Cornell EW, Nordmeyer RA, Kolbe WF, Jin J, Jones AL, Jaklevic JM, Schultz PG, Stevens RC. An approach to rapid protein crystallization using nanodroplets. J Appl Crystallogr. 2002;35:278–281. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lesley SA, Kuhn P, Godzik A, Deacon AM, Mathews I, Kreusch A, Spraggon G, Klock HE, McMullan D, Shin T, Vincent J, Robb A, Brinen LS, Miller MD, McPhillips TM, Miller MA, Scheibe D, Canaves JM, Guda C, Jaroszewski L, Selby TL, Elsliger MA, Wooley J, Taylor SS, Hodgson KO, Wilson IA, Schultz PG, Stevens RC. Structural genomics of the Thermotoga maritima proteome implemented in a high-throughput structure determination pipeline. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11664–11669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142413399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen AE, Ellis PJ, Miller MD, Deacon AM, Phizackerley RP. An automated system to mount cryo-cooled protein crystals on a synchrotron beamline, using compact sample cassettes and a small-scale robot. J Appl Crystallogr. 2002;2002:720–726. doi: 10.1107/s0021889802016709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tickle IJ, Laskowski RA, Moss DS. Error estimates of protein structure coordinates and deviations from standard geometry by full-matrix refinement of gammaB- and betaB2-crystallin. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:243–252. doi: 10.1107/s090744499701041x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McPhillips TM, McPhillips SE, Chiu HJ, Cohen AE, Deacon AM, Ellis PJ, Garman E, Gonzalez A, Sauter NK, Phizackerley RP, Soltis SM, Kuhn P. Blu-Ice and the Distributed Control System: software for data acquisition and instrument control at macromolecular crystallography beamlines. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2002;9:401–406. doi: 10.1107/s0909049502015170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kabsch W. Automatic processing of rotation diffraction data from crystals of initially unknown symmetry and cell constants. J Appl Crystallog. 1993;26:795–800. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terwilliger T, Berendzen J. Automated MAD and MIR structure solution. Acta Cryst. 1999;D55:849–861. doi: 10.1107/S0907444999000839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Terwilliger TC. Maximum-likelihood density modification. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2000;56:965–972. doi: 10.1107/S0907444900005072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langer G, Cohen SX, Lamzin VS, Perrakis A. Automated macromolecular model building for X-ray crystallography using ARP/wARP version 7. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1171–1179. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang H, Guranovic V, Dutta S, Feng Z, Berman HM, Westbrook JD. Automated and accurate deposition of structures solved by X-ray diffraction to the Protein Data Bank. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:1833–1839. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis IW, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MOLPROBITY: structure validation and all-atom contact analysis for nucleic acids and their complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W615–619. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vriend G. WHAT IF: a molecular modeling and drug design program. J Mol Graph. 1990;8:52–56. 29. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(90)80070-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaguine AA, Richelle J, Wodak SJ. SFCHECK: a unified set of procedures for evaluating the quality of macromolecular structure-factor data and their agreement with the atomic model. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:191–205. doi: 10.1107/S0907444998006684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleywegt GJ. Validation of protein crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2000;56:249–265. doi: 10.1107/s0907444999016364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Detection of protein assemblies in crystals. Computational Life Sciences: Proceedings of the First International Symposium, Complife Berlin Heidelberg; Springer-Verlag; 2005. pp. 163–174. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laskowski RA, Chistyakov VV, Thornton JM. PDBsum more: new summaries and analyses of the known 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D266–268. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matthews BW. Solvent content of protein crystals. J Mol Biol. 1968;33:491–497. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohlendorf DH, Anderson WF, Matthews BW. Many gene-regulatory proteins appear to have a similar alpha-helical fold that binds DNA and evolved from a common precursor. J Mol Evol. 1983;19:109–114. doi: 10.1007/BF02300748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aravind L, Anantharaman V, Balaji S, Babu MM, Iyer LM. The many faces of the helix-turn-helix domain: transcription regulation and beyond. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2005;29:231–262. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holm L, Park J. DaliLite workbench for protein structure comparison. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:566–567. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lehnherr H, Maguin E, Jafri S, Yarmolinsky MB. Plasmid addiction genes of bacteriophage P1: doc, which causes cell death on curing of prophage, and phd, which prevents host death when prophage is retained. J Mol Biol. 1993;233:414–428. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tyndall C, Lehnherr H, Sandmeier U, Kulik E, Bickle TA. The type IC hsd loci of the enterobacteria are flanked by DNA with high homology to the phage P1 genome: implications for the evolution and spread of DNA restriction systems. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:729–736. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2531622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kulik EM, Bickle TA. Regulation of the activity of the type IC EcoR124I restriction enzyme. J Mol Biol. 1996;264:891–906. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loenen WA, Daniel AS, Braymer HD, Murray NE. Organization and sequence of the hsd genes of Escherichia coli K-12. J Mol Biol. 1987;198:159–170. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90303-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prakash-Cheng A, Ryu J. Delayed expression of in vivo restriction activity following conjugal transfer of Escherichia coli hsdK (restriction-modification) genes. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4905–4906. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.15.4905-4906.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]