Abstract

Isolates of Branhamella catarrhalis from 13 patients with pneumonia, 6 patients with tracheobronchitis, and 8 patients who were colonized with the organism were studied with respect to susceptibility to the bactericidal action of normal human serum (NHS), glass slide hemagglutination (HA) of group O human erythrocytes, beta-lactamase production, and susceptibility to selected antimicrobial agents and laboratory drugs. A total of 18 of 27 isolates were serum resistant, 22 of 27 produced HA, and 21 of 27 were beta-lactamase positive. Statistically significant correlations were found between susceptibility to NHS and susceptibility to trypsin (r = +0.47; P = 0.01) and between susceptibility to NHS and HA (r = -0.48; P = 0.009). Significant correlations were also observed among several pairs of antimicrobial drugs. Analysis of variance showed that mean ampicillin MICs correlated with isolate group (r = -0.49; P = 0.03) in that the pneumonia isolates had higher MICs. Some phenotypic characteristics appeared to be independent of each other. These data suggest that important differences exist among clinically significant B. catarrhalis strains and that these differences may be due to differences in the cell wall envelope of the organism.

Full text

PDF

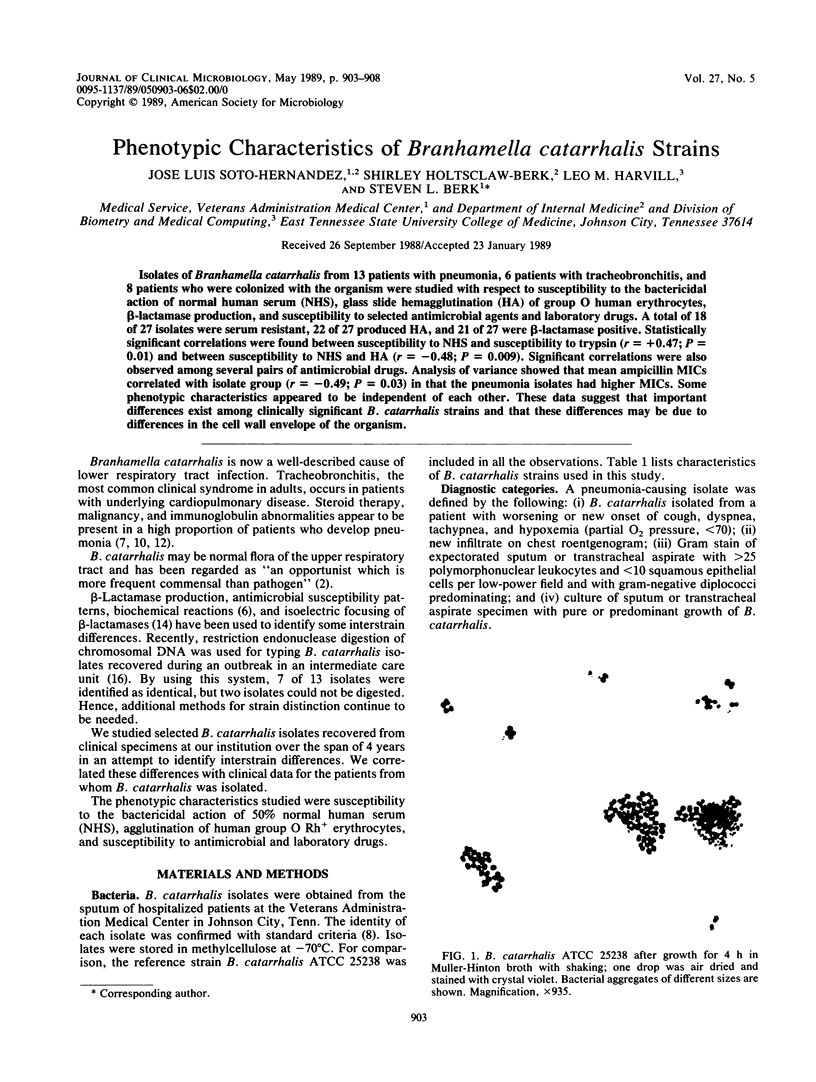

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alvarez S., Jones M., Holtsclaw-Berk S., Guarderas J., Berk S. L. In vitro susceptibilities and beta-lactamase production of 53 clinical isolates of Branhamella catarrhalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985 Apr;27(4):646–647. doi: 10.1128/aac.27.4.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apicella M. A., Westerink M. A., Morse S. A., Schneider H., Rice P. A., Griffiss J. M. Bactericidal antibody response of normal human serum to the lipooligosaccharide of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Infect Dis. 1986 Mar;153(3):520–526. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.3.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake M. S., Gotschlich E. C., Swanson J. Effects of proteolytic enzymes on the outer membrane proteins of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect Immun. 1981 Jul;33(1):212–222. doi: 10.1128/iai.33.1.212-222.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman A. J., Jr, Musher D. M., Jonsson S., Clarridge J. E., Wallace R. J., Jr Development of bactericidal antibody during Branhamella catarrhalis infection. J Infect Dis. 1985 May;151(5):878–882. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.5.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen J. J., Gadeberg O., Bruun B. Branhamella catarrhalis: significance in pulmonary infections and bacteriological features. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand B. 1986 Apr;94(2):89–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1986.tb03025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond L. A., Lorber B. Branhamella catarrhalis pneumonia and immunoglobulin abnormalities: a new association. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984 May;129(5):876–878. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.129.5.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doern G. V., Morse S. A. Branhamella (Neisseria) catarrhalis: criteria for laboratory identification. J Clin Microbiol. 1980 Feb;11(2):193–195. doi: 10.1128/jcm.11.2.193-195.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstein B. I., Lee T. J., Sparling P. F. Penicillin sensitivity and serum resistance are independent attributes of strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae causing disseminated gonococcal infection. Infect Immun. 1977 Mar;15(3):834–841. doi: 10.1128/iai.15.3.834-841.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hager H., Verghese A., Alvarez S., Berk S. L. Branhamella catarrhalis respiratory infections. Rev Infect Dis. 1987 Nov-Dec;9(6):1140–1149. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.6.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James J. F., Swanson J. Studies on gonococcus infection. XIII. Occurrence of color/opacity colonial variants in clinical cultures. Infect Immun. 1978 Jan;19(1):332–340. doi: 10.1128/iai.19.1.332-340.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnad A., Alvarez S., Berk S. L. Branhamella catarrhalis pneumonia in patients with immunoglobulin abnormalities. South Med J. 1986 Nov;79(11):1360–1362. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198611000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maness M. J., Sparling P. F. Multiple antibiotic resistance due to a single mutation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Infect Dis. 1973 Sep;128(3):321–330. doi: 10.1093/infdis/128.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash D. R., Wallace R. J., Jr, Steingrube V. A., Shurin P. A. Isoelectric focusing of beta-lactamases from sputum and middle ear isolates of Branhamella catarrhalis recovered in the United States. Drugs. 1986;31 (Suppl 3):48–54. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198600313-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson T. F., Patterson J. E., Masecar B. L., Barden G. E., Hierholzer W. J., Jr, Zervos M. J. A nosocomial outbreak of Branhamella catarrhalis confirmed by restriction endonuclease analysis. J Infect Dis. 1988 May;157(5):996–1001. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.5.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor P. W. Bactericidal and bacteriolytic activity of serum against gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1983 Mar;47(1):46–83. doi: 10.1128/mr.47.1.46-83.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]