Abstract

It has recently been shown that the epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) is compartmentalized in caveolin-rich lipid rafts and that pharmacological depletion of membrane cholesterol, which disrupts lipid raft formation, decreases the activity of ENaC. Here we show, for the first time, that a signature protein of caveolae, caveolin-1 (Cav-1), down-regulates the activity and membrane surface expression of ENaC. Physical interaction between ENaC and Cav-1 was also confirmed in a coimmunoprecipitation assay. We found that the effect of Cav-1 on ENaC requires the activity of Nedd4-2, a ubiquitin protein ligase of the Nedd4 family, which is known to induce ubiquitination and internalization of ENaC. The effect of Cav-1 on ENaC requires the proline-rich motifs at the C termini of the β- and γ-subunits of ENaC, the binding motifs that mediate interaction with Nedd4-2. Taken together, our data suggest that Cav-1 inhibits the activity of ENaC by decreasing expression of ENaC at the cell membrane via a mechanism that involves the promotion of Nedd4-2-dependent internalization of the channel.

Amiloride-sensitive epithelial Na+ channels (ENaC)3 are membrane proteins that are expressed in salt-absorptive epithelia, including the distal collecting tubules of the kidney, the mucosa of the distal colon, the respiratory epithelium, and the excretory ducts of sweat and salivary glands (1–4). Na+ absorption via ENaC is critical to the normal regulation of Na+ and fluid homeostasis and is important for maintaining blood pressure (5) and the volume of fluid in the respiratory passages (6). Increased ENaC activity has been implicated in the salt-sensitive inherited form of hypertension, Liddle's syndrome (7), and dehydration of the surface of the airway epithelium in the pathology associated with cystic fibrosis lung disease (8).

Expression of ENaC at the cell membrane surface is regulated by the E3 ubiquitin protein ligase, Nedd4-2 (neural precursor cell expressed developmentally down-regulated protein 4) (9). Interaction between the WW domains of Nedd4-2 and the proline-rich PY motifs (PPPXY) on ENaC is essential for Nedd4-2 to exert a negative effect on the channel (10, 11). This interaction leads to ubiquitination-dependent internalization of ENaC (12, 13). Several regulators of ENaC exert their effects on the channel by modulating the action of Nedd4-2. For instance, serum and glucocorticoid-dependent protein kinase (14), protein kinase B (15), and G protein-coupled receptor kinase (16) up-regulate activity of ENaC by inhibiting Nedd4-2. Although the details of cellular mechanisms that underlie internalization of ENaC remain to be elucidated, the physiological significance of Nedd4-dependent internalization of the channel has been well established. For instance, heritable mutations that delete the cytosolic termini of the β-or γ-subunit of ENaC, which contain the proline-rich motifs, are known to cause hyperactivity of ENaC in the kidney (17) and increase cell surface expression of the channel (7, 18).

The plasma membranes of most cell types contain lipid raft microdomains that are enriched with glycosphingolipid and cholesterol (19), that have distinctive biophysical properties, and that selectively include or exclude signaling molecules (20). These microdomains promote clustering of an array of integral membrane proteins in the membrane leaflets (21) and may be important for organizing cascades of signaling molecules (22, 23). Processes in which raft microdomains are involved include the intracellular transport of proteins and lipids to the cell membrane (24), the endocytotic retrieval of membrane proteins (25, 26), and signal transduction (27, 28). In addition, segregation of signaling molecules within lipid rafts may facilitate cross-talk between signal transduction pathways (29), a phenomenon that may be important in ensuring rapid and efficient integration of multiple cellular signaling events (30, 31). Of particular interest is the subpopulation of lipid rafts enriched with caveolin proteins. Caveolin-1 (Cav-1), a major caveolin isoform expressed in nonmuscle cells, has been identified as being involved in diverse cellular functions, such as vesicular transport, cholesterol homeostasis, and signal transduction (32). Cav-1 also regulates the activity and membrane expression of ion channels and transporters (28).

In epithelia, the majority of lipid rafts exist at the apical membrane surface (22). Pools of ENaC (33–36) and several proteins that regulate activity of ENaC, such as Nedd4 (37), protein kinase B (38), protein kinase C (39), Go (40), and the G protein-coupled receptor kinase (41), have been identified in detergent-insoluble and cholesterol-rich membrane fractions from a variety of cell types, consistent with localization of these proteins in lipid rafts. Furthermore, detergent-free buoyant density separation of lipid rafts has revealed the presence of Cav-1 with ENaC in the lipid raft-rich membrane fraction (35). The physiological role of lipid rafts in the regulation of ENaC has been the subject of many recent investigations. Most of these studies used a pharmacological agent, methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD), to promote redistribution of proteins away from the cholesterol-enriched membrane domains. The results were, however, inconclusive. In some studies, MβCD treatment was found to inhibit open probability (42) or cell surface expression of ENaC (35), whereas others found no direct effect of MβCD on the channel (33, 43).

Despite a number of studies into the role of lipid rafts on the regulation of ENaC, little is known about the physiological relevance of caveolins to the function of this ion channel. In the present study, we use gene interference and gene expression techniques to determine the role of Cav-1 in the regulation of ENaC activity. We provide evidence of the association of Cav-1 with ENaC and evidence that Cav-1 negatively regulates both activity and abundance of ENaC at the surface of epithelial cells. Importantly, we demonstrate, for the first time, that the mechanism by which Cav-1 regulates activity of ENaC involves the E3 ubiquitin protein ligase, Nedd4-2.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

DNA Constructs—Mouse α-, β-, and γ-ENaC (in pBluescript) were a gift from Thomas R. Kleyman (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA). ENaC subclones with C-terminal FLAG tags were provided by Angeles Sanchez-Perez (University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia). Cav-1 fused with monomeric red protein (mRed) in pcDNA3.1 was obtained from Richard E. Pagano (Mayo Clinic and Foundation, Rochester, MN), Cav-1 S80E was obtained from Michael B. Robinson (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA). Wild-type Nedd4-2 in pcDNA3.1 was generated as described previously (11).

Cell Culture and Transfection and Reagents—Fischer rat thyroid (FRT) cells were a gift from Lucio Nitsch (University of Naples, Naples, Italy), and M1 mouse collecting duct cells, originally generated by Stoos et al. (44), were a gift from Christoph Korbmacher (Universität Erlangen, Nürnberg, Germany). Both cell types were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 medium with 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37 °C. The medium for FRT cells contained 5% fetal bovine serum, whereas the medium for M1 cells contained 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 nm dexamethasone. The cells were seeded onto permeable filter supports (Millicell PCF, 0.4-μm pore size; Millipore). One day after seeding, FRT cells were cotransfected with cDNA of α-, β-, and γ-mENaC-FLAG (0.7 μg/ml each). When appropriate, FRT and M1 cells were transfected with cDNA of mRED-tagged Cav-1 (3 μg/ml), siRNA against Nedd4-2 (0.5 μg/ml) or siRNA against Cav-1 (0.5 μg/ml). In short, cDNA or siRNA were mixed with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) in Opti-MEM reduced serum medium (Invitrogen) and incubated for 20 min at room temperature before being transferred to the apical side of the monolayer and further incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. The transfection medium was then replaced with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 medium containing fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. In addition, the medium also contained dexamethasone (100 nm) for M1 cells or amiloride (10 μm) for FRT cells. All of the siRNAs were obtained from Qiagen, and all of the reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise specified. Water-soluble cholesterol for the cholesterol replenishment study was from Sigma (catalogue number C4951).

Immunoblotting—Two days after transfection, the cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline before treatment with a lysis buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, 150 mm NaCl, 10 mm EDTA with 10% glycerol and 1% Triton X-100 plus Complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science). After the protein concentration of each lysate was determined, an equal amount of protein lysate was loaded onto a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Following electrophoresis, the protein was transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and incubated overnight with anti-caveolin-1 or anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody. The blots were washed to remove unbound antibodies before incubating with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. The blots were then washed with a Tris-buffered saline buffer containing 0.1% Tween 20. The proteins of interest were then visualized using an ECL™ Western blotting kit (GE Healthcare) and quantitated by densitometric analysis with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). The data are representative of at least three experiments.

Immunoprecipitation—The lysates obtained from 1–2 × 107 cells were mixed with anti-FLAG antibodies (2 μg/ml) for 4 h or overnight and then incubated with 40 μl of protein A/G-agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 4 h at 4 °C. Immune complexes were washed five times with lysis buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, 150 mm NaCl, 10 mm EDTA, 10% glycerol, and 1% Triton X-100 plus Complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science). After boiling in SDS-PAGE sample buffer, the samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and electro-transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were immunoblotted with the indicated primary antibodies followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. The bands were visualized by chemiluminescence.

Quantitation of Amiloride-sensitive Na+ Current—After the monolayer became confluent, normally within 2–3 days following transfection, the Millicell PCF insert was transferred to a modified Ussing chamber. The apical and basolateral surfaces of the monolayer were simultaneously perfused with a solution containing 130 mm NaCl, 1 mm CaCl2, 1 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 5 mm glucose, 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, maintained at 37 °C. The experiments were carried out under open circuit conditions (45). Transepithelial resistance was measured by applying short (1 s) repetitive 10-μA current pulses across the epithelium. The transepithelial potential differences (Vte) were measured with reference to the luminal side of the epithelium, and the equivalent short circuit current was calculated according to Ohm's law. Amiloride-sensitive equivalent short circuit current (Iami) was determined as the change in current following the addition of amiloride (10 μm) to the apical bathing solution. The data were normalized by dividing the amiloride-sensitive short circuit current by that observed in control cells transfected with ENaC and studied on the same day. This ratio was reported as relative amiloride-sensitive equivalent short circuit current (Iami (relative)). The data for each experiment were obtained from at least three different batches of cells and are reported as the means ± S.E. with the number of experiments in parentheses. Statistical significance was assessed using Student's t test.

Quantitation of Na+/K+ ATPase Activity—M1 cell monolayers were mounted in a modified Ussing chamber bathed symmetrically with the physiological solution. The chamber was connected to a VCC MC8 multichannel voltage/current clamp amplifier (Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, CA) together with the Acquire & Analyze data acquisition system (V2.3.177; Physiologic Instruments) and used to current clamp the monolayers at zero current (open circuit), monitor the transepithelial voltage with reference to the basolateral side of the epithelium, and inject intermittent current pulses to determine the transepithelial resistance. The equivalent short circuit current was calculated using Ohm's law and plotted by the software. Activity of the Na+/K+-ATPase was determined as previously described (46). In short, amiloride (10 μm) was added to the apical bathing solution to inhibit activity of ENaC. Nystatin (360 μg/ml) was then added to the apical solution to permeablize this membrane and to eradicate any rate limitation associated with the apical Na+ entry. Isc was allowed to stabilize for 30 min before the addition of 1 mm ouabain, an inhibitor of the Na+/K+-ATPase, to the basolateral solution. The change in short circuit current (Isc) following the addition of ouabain was used to estimate the activity of the Na+/K+-ATPase.

Surface Expression of ENaC—FRT cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged α-, β-, and γ-mENaC. Two days after transfection, the cells were washed three times with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and then incubated for 30 min in 5 ml of cell-impermeant Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin solution (0.5 mg/ml; Pierce) at 4 °C. The reaction was stopped by quenching with Tris-buffered saline. The cells were solubilized in lysis buffer, and the lysate was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and mixed with 250 μl of NeutrAvidin™ gel slurry (Pierce) before incubating with gentle rocking for 60 min at room temperature. After incubation, the sample was centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 2 min. The precipitant, containing the biotinylated proteins, was washed five times with lysis buffer. Finally, the biotinylated proteins were eluted by the addition of SDS sample buffer and analyzed by Western blot using anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody.

RESULTS

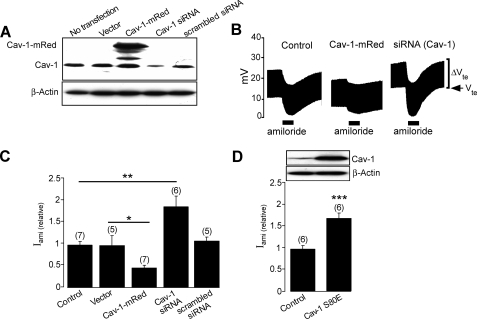

Caveolin-1 Down-regulates Activity of ENaC—To determine the physiological role of Cav-1 in the regulation of ENaC activity and membrane surface expression, we first investigated whether interfering with Cav-1 expression could alter the activity of endogeneous ENaC in M1 cells. Immunoblot analysis revealed that transfecting the M1 cells with an siRNA directed against Cav-1 substantially suppressed endogenous Cav-1 protein level (Fig. 1A). The effect of Cav-1 knockdown on the activity of ENaC was then determined in Ussing chamber experiments (Fig. 1, B and C). We found that the normalized amiloride-sensitive Na+ current in Cav-1 siRNA transfected cells (1.92 ± 0.26, n = 6) is significantly higher than that of the nontransfected cells (1.00 ± 0.08, n = 7; p < 0.01). The absence of any detectable effect of the scrambled siRNA on either the level of endogenous expression of Cav-1 protein or on the amiloride-sensitive Na+ current (1.11 ± 0.09, n = 5; p > 0.05) indicates that increased activity of ENaC in Cav-1 knockdown cells is not attributable to a nonspecific effect of the siRNA used and, hence, that the basal activity of Cav-1 may be physiologically a negative regulator of ENaC. To confirm this finding, we inhibited Cav-1 activity in M1 cells by overexpressing Cav-1 S80E (Fig. 1D), a known dominant-negative variant that mimics the phosphorylated form of Cav-1 (47) and that has a profound inhibitory effect on the function of Cav-1 (48, 49). Expression of Cav-1 S80E increases activity of ENaC (Fig. 1D) by 66 ± 0.62% (n = 6, p < 0.001). On the other hand, overexpression of mRed-tagged wild-type Cav-1 significantly inhibited activity of ENaC (Fig. 1, B and C).

FIGURE 1.

Caveolin-1 decreases ENaC activity. A, immunoblot analysis of M1 cells transfected with vector, Cav-1-mRed, an siRNA directed against Cav-1 (Cav-1 siRNA) or scrambled siRNA with β-actin used as control protein. B, representative recordings of transepithelial potential (Vte) of M1 mouse collecting duct cells expressing Cav-1-mRed or siRNA against Cav-1 (5′-CAGCCGTGTCTATTCCATCTA-3′) showing the response to 10 μm amiloride (solid bar), Vte denotes the transepithelial potential, and ΔVte denotes the voltage deflection in response to 10 μA current pulses. C, relative amiloride-sensitive short circuit current (Iami (relative)) in M1 cells transfected with vector, Cav-1-mRed, an siRNA directed against Cav-1 (Cav-1 siRNA), or scrambled siRNA. D, relative amiloride-sensitive short circuit current from untransfected M1 cells (Control) or cells transfected with rat caveolin-1 S80E mutant (Cav-1 S80E) (lower panel) and a immunoblot of the corresponding experiments with β-actin used as control protein (upper panel). *, **, and *** indicate p < 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001, respectively. The number of experiments is shown in parentheses.

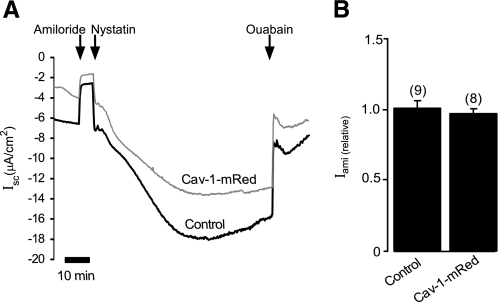

It has been previously reported that interfering with basolateral cholesterol content alters Na+ transport in A6 amphibian kidney cells (43), suggesting that lipid rafts may indirectly regulate Na+ transport via ENaC by modulating the activity of the basolateral Na+/K+-ATPase. In addition, Cav-1 has been shown to play an important role in regulating the internalization of the Na+/K+-ATPase in renal epithelia (50, 51). To eliminate the possibility that modifying expression of Cav-1 might alter activity of the basolateral Na+/K+-ATPase, which would, in turn, affect the electrochemical driving force for apical influx of Na+ via ENaC, we examined the effect of Cav-1 overexpression on the activity of the Na+/K+-ATPase in M1 cells (Fig. 2A) using the method described under “Experimental Procedures.” As shown in Fig. 2B, the normalized ouabain-sensitive current, which represents activity of the Na+/K+-ATPase, in cells transfected with Cav-1 (0.95 ± 0.02, n = 8) is not significantly different from that of the control cells (1.0 ± 0.05, n = 9; p > 0.05), suggesting that the activity of Cav-1 does not significantly influence the activity of the basolateral Na+/K+-ATPase.

FIGURE 2.

Na+/K+ ATPase activity in M1 cells. A, continuous short circuit current recording of M1 cell monolayer transfected with Cav-1 (Cav-1-mRed) or without (Control). Application of 10 μm amiloride to the apical solution was as indicated. The membrane was then permeabilized by adding nystatin (360 μg/ml) to the solution bathing the apical membrane. After allowing 30 min for stabilization of the Isc, ouabain (1 mm) was added to the solution bathing the basolateral membrane, resulting in a shift in Isc that represents activity of the basolateral Na+/K+-ATPase. B, normalized ouabain-sensitive current of experiments in A.

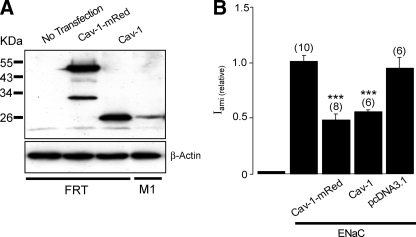

Cav-1 Regulates Activity of ENaC in FRT Cells—Cav-1 has been shown to interact with and regulate the function and trafficking of an array of membrane proteins (52, 53), including ion channels and transporters (25, 49, 54, 55). To establish a cell model that then can be used to investigate whether Cav-1 regulates membrane expression of ENaC, we determined the effect of Cav-1 on the activity of ENaC exogenously expressed in FRT cells (Fig. 3). This cell type has been used extensively to investigate physiological regulation of ENaC (12, 14, 56) and has been previously reported to lack morphological caveolae (57) and Cav-1 protein expression (58). Overexpression of Cav-1, however, induces formation of the typical flask-shaped caveolae in FRT cells (57). Consistent with these reports, our immunoblot analysis failed to detect expression of Cav-1 in FRT cells grown on permeable supports (Fig. 3A). We then determined the role of Cav-1 in the regulation of ENaC by coexpressing Cav-1-mRed or untagged wild-type Cav-1 together with FLAG-tagged ENaC in FRT cells. The expression of Cav-1 was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 3A). We found that expression of either form of Cav-1 is effective in inhibiting the activity of ENaC expressed in FRT cells (Fig. 3B). These data also confirmed that tagging mRed at the C-terminal of Cav-1 has no effect on the function of the protein.

FIGURE 3.

Cav-1 down-regulates ENaC activity in FRT cells. A, immunoblot analysis of Cav-1 in untransfected FRT cells or FRT cells transfected with Cav-1-mRed or Cav-1. Detection of endogenous Cav-1 from M1 cell lysates (fourth lane) and β-actin were used as a positive control and control protein, respectively. B, relative amiloride-sensitive short circuit current measured in FRT cells untransfected or transfected with three subunits of mouse ENaC (ENaC) alone, cotransfected with ENaC subunits and Cav-1-mRed or untagged Cav-1 (Cav-1) or pcDNA3.1 empty vector. *** indicates p < 0.001.

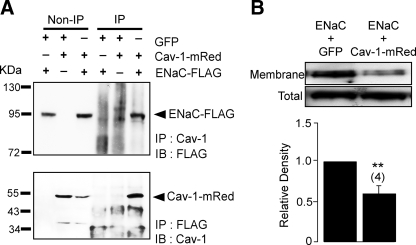

Cav-1 and ENaC Are Associated—To determine the relationship between Cav-1 and ENaC, FRT cells were cotransfected with Cav-1-mRed and FLAG-tagged ENaC. Cav-1 in lysates from the cotransfected cells was then immunoprecipitated, and the product was probed with an anti-FLAG antibody (Fig. 4A, upper panel). In a complementary study, ENaC in the cell lysates was immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody, and the precipitant was probed with an antibody specific to Cav-1 (Fig. 4A, lower panel). The presence of FLAG-tagged protein in the precipitant pulled down by antibody against Cav-1 (Fig. 4A, upper panel) and Cav-1 in the precipitant pulled down by anti-FLAG antibody (Fig. 4A, lower panel) suggests that Cav-1 and ENaC are physically associated. To investigate whether Cav-1 regulates the abundance of ENaC at the cell surface, membrane proteins of FRT cells cotransfected with ENaC-FLAG and wild-type Cav-1 were biotinylated, and the biotinylated proteins were subsequently pulled down with NeutrAvidin and probed with an anti-FLAG antibody to determine membrane expression of ENaC, as previously described (14). We found that expression of Cav-1 significantly reduces the surface abundance of ENaC-FLAG (Fig. 4B), suggesting that membrane expression of ENaC is negatively influenced by Cav-1.

FIGURE 4.

Cav-1 interacts with ENaC and modulates surface expression of the channel. A, immunoprecipitation assay of total cell lysates from FRT cells. The cells were transiently transfected with or without GFP plasmid, Cav-1-mRed, and ENaC subunits (α-, β-, and γ-subunits, each of which was tagged with FLAG) as indicated. Non-IP cell lysates were probed with either anti-FLAG antibody (upper panel) or anti-Cav-1 antibody (lower panel) without being immunoprecipitated. IP lanes cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with either Cav-1 specific antibody (upper panel) or anti-FLAG antibody (lower panel) and probed with anti-FLAG antibody or Cav-1 specific antibody, respectively. IP, immunoprecipitation; IB, immunoblot. B, a representative image of immunoblot analysis for FLAG-tagged membrane protein in nonpolarized FRT cells transfected with α-, β-, and γ-ENaC-FLAG together with GFP or with Cav-1-mRed. Proteins at the membrane surface of FRT cells were biotinylated and pulled down with NeutrAvidin and detected by immunoblotting using anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody. FLAG-tagged proteins in the total cell lysates of each group were detected, and the relative density of the FLAG-tagged membrane protein to that of the FLAG-tagged protein in total cell lysates was determined by densitometric analysis and shown in the lower panel. ** indicates p < 0.01 (n = 4).

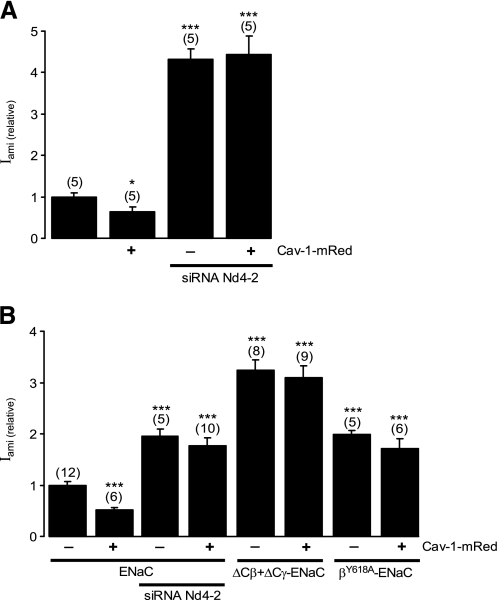

Caveolin-1 Down-regulates ENaC by a Nedd4-2-dependent Mechanism—Given the importance of the ubiquitin protein ligases of the Nedd4 family, particularly Nedd4-2, in regulating membrane expression of ENaC (12, 56), and the presence of Nedd4 in lipid raft microdomains (37), we investigated whether Nedd4-2 is involved in Cav-1-dependent down-regulation of ENaC. To do so, we first determined whether inhibiting Nedd4-2 activity altered regulation of ENaC by Cav-1. In this experiment, M1 cell monolayers were transfected with either Cav-1 or siRNA directed against Nedd4-2, or both (Fig. 5A). We found that, in agreement with our previous report (14), knocking down Nedd4-2 expression by transfecting cells with siRNA against Nedd4-2 significantly increased the activity of ENaC (Fig. 5A). The inhibitory effect of Cav-1 on ENaC, however, was not observed in M1 cells in which Nedd4-2 expression had been suppressed (Fig. 5A), suggesting that the activity of Nedd4-2 is required for Cav-1 to mediate its effect on ENaC.

FIGURE 5.

Cav-1 decreases ENaC activity in a Nedd4-2-dependent manner. A, relative amiloride-sensitive short circuit current in M1 mouse collecting duct cells transfected with Cav-1-mRed, transfected siRNA against Nedd4-2 (siRNA Nd4–2), or cotransfected with Cav-1-mRed and siRNA against Nedd4-2. B, relative amiloride-sensitive short circuit current of FRT cells cotransfected with wild-type α-, β-, and γ-mENaC, or wild-type α-ENaC with mutant β-ENaC that is truncated at amino acid Cys594 (ΔCβ) and γ-ENaC that is truncated at amino acid Phe610 (ΔCγ), or with wild-type α- and γ-ENaC and βY618A-ENaC mutant. The cells were cotransfected with siRNA against Nedd4-2 (siRNA Nd4–2) or Cav-1-mRed as indicated. * and *** indicate p < 0.05 and 0.001, respectively.

It is well established that Nedd4-2 induces ubiquitin-dependent internalization of ENaC by directly interacting with the cytosolic Proline-rich PY motifs at the C-terminal of the β- and γ-subunits of ENaC (15). To investigate whether binding of Nedd4-2 to ENaC is essential for Cav-1-mediated down-regulation of the channel, we generated: (i) a clone of the β subunit of ENaC, β-ENaC Y618A, in which tyrosine 618 was replaced with alanine to mutate the binding site for Nedd4-2, and (ii) β- and γ-ENaC clones, in which the proline-rich motifs at their C-terminals were truncated at amino acids Cys594 (ΔCβ) and Phe610 (ΔCγ), respectively, to completely remove the Nedd4-2-binding sites. When cotransfected into FRT cells together with wild-type α-or α- and γ-ENaC subunits as appropriate (Fig. 5B), the relative Iami in cells expressing the mutated ENaC subunits, either β-ENaC Y618A (2.05 ± 0.10, n = 5) or ΔCβ- and ΔCγ-ENaC (3.11 ± 0.17, n = 8), were significantly higher than in cells in control experiments that expressed only wild-type α-, β-, and γ-ENaC (1.00 ± 0.08, n = 12; p < 0.001). Importantly, expression of Cav-1 did not inhibit activity of ENaC in cells expressing β-ENaC Y618A or ΔCβ- and ΔCγ-ENaC (Fig. 5B). Together, these data indicate that interaction between Nedd4-2 and ENaC is an essential component of the mechanism by which Cav-1 down-regulates ENaC activity.

DISCUSSION

Biochemical and functional evidence indicates that, at the cell membrane, many receptors and ion channels localize to lipid raft microdomains (60). It has been suggested that a proportion of ENaC is localized into cholesterol-rich lipid raft submembrane domains (34–36) and that ENaC are associated with a protein marker of caveolae, Cav-1 (35). Our coimmunoprecipitation data from FRT cells cotransfected with Cav-1 and ENaC confirm that a physical interaction exists between these two proteins (Fig. 4A). Using gene knockdown by siRNA to modulate Cav-1 expression in M1 cells, we demonstrate that suppression of endogenous Cav-1 expression increases activity of ENaC, and conversely, increasing expression of Cav-1 inhibits activity of the channel.

The conclusion of our study that Cav-1 is a negative regulator of ENaC, at first glance, seems to conflict with previous reports, which have used MβCD to disperse membrane cholesterol and disrupt lipid raft formation (33, 35, 42, 43). Most of these studies suggest that the activity of ENaC is increased by the presence of lipid rafts at the cell membrane. This apparent contradiction, however, may be due to the impact of cholesterol-depleting agents such as MβCD on general cell physiology (61–65). In particular, cholesterol depletion does not discriminate between different types of cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains, and its effects are not limited to caveolin-rich lipid rafts. If ENaC in caveolin-rich and caveolin-free rafts are differentially regulated, it is possible that, in cholesterol depletion studies, the effect of disrupting other classes of lipid rafts could mask the effect of Cav-1 on ENaC.

Our siRNA data are confirmed by the study in which we express the Cav-1 S80E dominant-negative mutant. Consistent with its action as an inhibitor of Cav-1, expression of Cav-1 S80E slows down endocytosis of cholera toxin (64, 66), the glutamate transporter (49), and glucose transporter type 4 (64, 67) and inhibits Cav-1-dependent inhibition of large conductance K+ channel (30). The effect of Cav-1 S80E on ENaC, although supported by our siRNA data, contrasts with the report by Hill et al. (35) that basal activity of ENaC in the mouse collecting duct cell line, MPKCCD14, was inhibited by expressing a Cav-1 tagged at the N-terminal with enhanced GFP (Cav-1-eGFP) or by expressing a mutant caveolin-3 lacking the first 53 amino acids, Cav-3DGV. Hill et al. (35) interpreted these findings as indicating that Cav-1 promotes trafficking of ENaC from the cytosolic pool to the cell membrane (35). Although our data cannot exclude this possibility, the inhibitory effect of Cav-1 on membrane expression of ENaC that we have observed suggests that Cav-1 must increase retrieval of membrane ENaC at a greater rate than any effect on replenishment of cell surface ENaC from the cytosolic pool. One possible explanation for this negative effect of N-terminal mutated caveolin on activity of ENaC is that Cav-1-eGFP and Cav-3DGV may interfere with cholesterol homeostasis, as is evident from the observation that the inhibitory effect of Cav-3DGV on H-Ras signaling is completely reversed by cholesterol replenishment (68). In this regard, N-terminal mutated caveolin mimics the effect of MβCD on cholesterol-rich membranes, and hence, expression of N-terminal mutated caveolin might have a broader effect on cell physiology than that of blocking the activity of caveolins.

Another significant outcome of our work is that the activity of Nedd4-2 and its interaction with ENaC are essential for Cav-1-mediated down-regulation of ENaC activity. Nedd4-2-dependent ubiquitination of ENaC is a common internalization signal required for the first step of its endocytosis. The role of Nedd4-2 in Cav-1-dependent down-regulation of ENaC activity and the negative effect of Cav-1 on the abundance of ENaC at the cell membrane favors the possibility that Cav-1 might control activity of ENaC by regulating internalization of the channel. A wealth of experimental evidence has established that after Nedd4-dependent ubiquitination, membrane ENaC is internalized exclusively via a clathrin-dependent pathway (69). Emerging data suggest, however, that in some situations, lipid rafts and clathrin-dependent endocytosis may not be mutually exclusive (64, 70). For instance proteins associated with caveolae and lipid rafts, such as cholera toxin (71), anthrax toxin (72), tetanus toxin (73), and apolipoprotein E receptor 2 (74), internalize via clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Moreover, localization of proteins, such as the B-cell receptor and CD317, to lipid raft microdomains facilitates their internalization via clathrin-dependent mechanisms (59, 70, 75). Our data indicate that endocytosis of ENaC may be another example of clathrin-dependent endocytosis that is regulated by caveolin.

This work was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Grant 508086 and Australian Research Council Grant DP0774320.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: ENaC, epithelial Na+ channel; Cav-1, caveolin-1; MβCD, methyl-β-cyclodextrin; E3, ubiquitin-protein isopeptide ligase; FRT, Fischer rat thyroid; siRNA, small interfering RNA.

References

- 1.Duc, C., Farman, N., Canessa, C. M., Bonvalet, J. P., and Rossier, B. C. (1994) J. Cell Biol. 127 1907–1921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez de la Rosa, D., Canessa, C. M., Fyfe, G. K., and Zhang, P. (2000) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 62 573–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farman, N., Talbot, C. R., Boucher, R., Fay, M., Canessa, C., Rossier, B., and Bonvalet, J. P. (1997) Am. J. Physiol. 272 C131–C141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsushita, K., McCray, P. B., Jr., Sigmund, R. D., Welsh, M. J., and Stokes, J. B. (1996) Am. J. Physiol. 271 L332–L339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hummler, E., and Horisberger, J. D. (1999) Am. J. Physiol. 276 G567–G571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matalon, S., and O'Brodovich, H. (1999) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 61 627–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snyder, P. M., Price, M. P., McDonald, F. J., Adams, C. M., Volk, K. A., Zeiher, B. G., Stokes, J. B., and Welsh, M. J. (1995) Cell 83 969–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zabner, J., Smith, J. J., Karp, P. H., Widdicombe, J. H., and Welsh, M. J. (1998) Mol. Cell 2 397–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raikwar, N. S., and Thomas, C. P. (2008) Am. J. Physiol. 294 F1157–F1165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harvey, K. F., Dinudom, A., Cook, D. I., and Kumar, S. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 8597–8601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fotia, A. B., Dinudom, A., Shearwin, K. E., Koch, J. P., Korbmacher, C., Cook, D. I., and Kumar, S. (2003) FASEB J. 17 70–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou, R., Patel, S. V., and Snyder, P. M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 20207–20212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malik, B., Yue, Q., Yue, G., Chen, X. J., Price, S. R., Mitch, W. E., and Eaton, D. C. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. 289 F107–F116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee, I. H., Dinudom, A., Sanchez-Perez, A., Kumar, S., and Cook, D. I. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 29866–29873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee, I. H., Campbell, C. R., Cook, D. I., and Dinudom, A. (2008) Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 35 235–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dinudom, A., Fotia, A. B., Lefkowitz, R. J., Young, J. A., Kumar, S., and Cook, D. I. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101 11886–11890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamynina, E., Debonneville, C., Hirt, R. P., and Staub, O. (2001) Kidney Int. 60 466–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Firsov, D., Schild, L., Gautschi, I., Merillat, A. M., Schneeberger, E., and Rossier, B. C. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93 15370–15375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurzchalia, T. V., and Parton, R. G. (1999) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 11 424–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Callera, G. E., Montezano, A. C., Yogi, A., Tostes, R. C., and Touyz, R. M. (2007) Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 16 90–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foster, L. J., De Hoog, C. L., and Mann, M. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 5813–5818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simons, K., and Ikonen, E. (1997) Nature 387 569–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson, R. G. (1998) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67 199–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salaun, C., James, D. J., and Chamberlain, L. H. (2004) Traffic 5 255–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lajoie, P., and Nabi, I. R. (2007) J. Cell. Mol. Med. 11 644–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanzal-Bayer, M. F., and Hancock, J. F. (2007) FEBS Lett. 581 2098–2104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simons, K., and Toomre, D. (2000) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1 31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patel, H. H., Murray, F., and Insel, P. A. (2008) Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 48 359–391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schlegel, A., Volonte, D., Engelman, J. A., Galbiati, F., Mehta, P., Zhang, X. L., Scherer, P. E., and Lisanti, M. P. (1998) Cell. Signal. 10 457–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang, X. L., Ye, D., Peterson, T. E., Cao, S., Shah, V. H., Katusic, Z. S., Sieck, G. C., and Lee, H. C. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 11656–11664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patra, S. K. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1785 182–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Razani, B., Woodman, S. E., and Lisanti, M. P. (2002) Pharmacol. Rev. 54 431–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shlyonsky, V. G., Mies, F., and Sariban-Sohraby, S. (2003) Am. J. Physiol. 284 F182–F188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hill, W. G., An, B., and Johnson, J. P. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 33541–33544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hill, W. G., Butterworth, M. B., Wang, H., Edinger, R. S., Lebowitz, J., Peters, K. W., Frizzell, R. A., and Johnson, J. P. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 37402–37411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prince, L. S., and Welsh, M. J. (1999) Am. J. Physiol. 276 C1346–C1351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plant, P. J., Lafont, F., Lecat, S., Verkade, P., Simons, K., and Rotin, D. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 149 1473–1484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adam, R. M., Mukhopadhyay, N. K., Kim, J., Di Vizio, D., Cinar, B., Boucher, K., Solomon, K. R., and Freeman, M. R. (2007) Cancer Res. 67 6238–6246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weerth, S. H., Holtzclaw, L. A., and Russell, J. T. (2007) Cell Calcium 41 155–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guzzi, F., Zanchetta, D., Chini, B., and Parenti, M. (2001) Biochem. J. 355 323–331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carman, C. V., Lisanti, M. P., and Benovic, J. L. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 8858–8864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balut, C., Steels, P., Radu, M., Ameloot, M., Driessche, W. V., and Jans, D. (2006) Am. J. Physiol. 290 C87–C94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.West, A., and Blazer-Yost, B. (2005) Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 16 263–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stoos, B. A., Naray-Fejes-Toth, A., Carretero, O. A., Ito, S., and Fejes-Toth, G. (1991) Kidney Int. 39 1168–1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kunzelmann, K., Beesley, A. H., King, N. J., Karupiah, G., Young, J. A., and Cook, D. I. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97 10282–10287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramminger, S. J., Baines, D. L., Olver, R. E., and Wilson, S. M. (2000) J. Physiol. 524 539–547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schlegel, A., Arvan, P., and Lisanti, M. P. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 4398–4408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trouet, D., Hermans, D., Droogmans, G., Nilius, B., and Eggermont, J. (2001) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 284 461–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gonzalez, M. I., Krizman-Genda, E., and Robinson, M. B. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 29855–29865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu, J., Liang, M., Liu, L., Malhotra, D., Xie, Z., and Shapiro, J. I. (2005) Kidney Int. 67 1844–1854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu, J., and Shapiro, J. I. (2007) Pathophysiology 14 171–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hommelgaard, A. M., Roepstorff, K., Vilhardt, F., Torgersen, M. L., Sandvig, K., and van Deurs, B. (2005) Traffic 6 720–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cohen, A. W., Hnasko, R., Schubert, W., and Lisanti, M. P. (2004) Physiol. Rev. 84 1341–1379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cha, S. K., Wu, T., and Huang, C. L. (2008) Am. J. Physiol. 294 F1212–F1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fecchi, K., Volonte, D., Hezel, M. P., Schmeck, K., and Galbiati, F. (2006) FASEB J. 20 705–707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kabra, R., Knight, K. K., Zhou, R., and Snyder, P. M. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 6033–6039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lipardi, C., Mora, R., Colomer, V., Paladino, S., Nitsch, L., Rodriguez-Boulan, E., and Zurzolo, C. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 140 617–626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zurzolo, C., van't Hof, W., van Meer, G., and Rodriguez-Boulan, E. (1994) EMBO J. 13 42–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stoddart, A., Dykstra, M. L., Brown, B. K., Song, W., Pierce, S. K., and Brodsky, F. M. (2002) Immunity 17 451–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martens, J. R., O'Connell, K., and Tamkun, M. (2004) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 25 16–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rodal, S. K., Skretting, G., Garred, O., Vilhardt, F., van Deurs, B., and Sandvig, K. (1999) Mol. Biol. Cell 10 961–974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Subtil, A., Gaidarov, I., Kobylarz, K., Lampson, M. A., Keen, J. H., and McGraw, T. E. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96 6775–6780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Parton, R. G., and Richards, A. A. (2003) Traffic 4 724–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shigematsu, S., Watson, R. T., Khan, A. H., and Pessin, J. E. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 10683–10690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kwik, J., Boyle, S., Fooksman, D., Margolis, L., Sheetz, M. P., and Edidin, M. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 13964–13969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jayanthi, L. D., Samuvel, D. J., and Ramamoorthy, S. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 19315–19326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yuan, T., Hong, S., Yao, Y., and Liao, K. (2007) Cell Res. 17 772–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roy, S., Luetterforst, R., Harding, A., Apolloni, A., Etheridge, M., Stang, E., Rolls, B., Hancock, J. F., and Parton, R. G. (1999) Nat. Cell Biol. 1 98–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lu, C., Pribanic, S., Debonneville, A., Jiang, C., and Rotin, D. (2007) Traffic 8 1246–1264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rollason, R., Korolchuk, V., Hamilton, C., Schu, P., and Banting, G. (2007) J. Cell Sci. 120 3850–3858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hansen, G. H., Dalskov, S. M., Rasmussen, C. R., Immerdal, L., Niels-Christiansen, L. L., and Danielsen, E. M. (2005) Biochemistry (Mosc.) 44 873–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Abrami, L., Liu, S., Cosson, P., Leppla, S. H., and van der Goot, F. G. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 160 321–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Deinhardt, K., Berninghausen, O., Willison, H. J., Hopkins, C. R., and Schiavo, G. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 174 459–471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cuitino, L., Matute, R., Retamal, C., Bu, G., Inestrosa, N. C., and Marzolo, M. P. (2005) Traffic 6 820–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cheng, P. C., Dykstra, M. L., Mitchell, R. N., and Pierce, S. K. (1999) J. Exp. Med. 190 1549–1560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]