Abstract

Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase I (Tdp1) resolves topoisomerase I (Top1)-DNA adducts accumulated from natural DNA damage, as well as from the action of certain anticancer drugs. Tdp1 catalyzes the hydrolysis of the phosphodiester bond between the catalytic tyrosine residue of Top1 and the DNA 3′ phosphate. Only a limited number of weak inhibitors have been reported for Tdp1, and there is an unmet need to identify novel chemotypes through screening of chemical libraries. Herein we present an easily configured, highly-miniaturized, and robust Tdp1 assay utilizing the AlphaScreen technology. Uninhibited enzyme reaction is associated with low signal while inhibition leads to a gain of signal, making the present assay format especially attractive for automated large-collection high-throughput screening. We report the identification and initial characterization of four previously-unreported inhibitors of Tdp1. Among them, suramin, NF449 and methyl-3,4-dephostatin are phosphotyrosine mimetics that may act as Tdp1 substrate decoys. We also report a novel biochemical assay using the SCAN1 Tdp1 mutant to study the mechanism of action of methyl-3,4 dephostatin.

INTRODUCTION

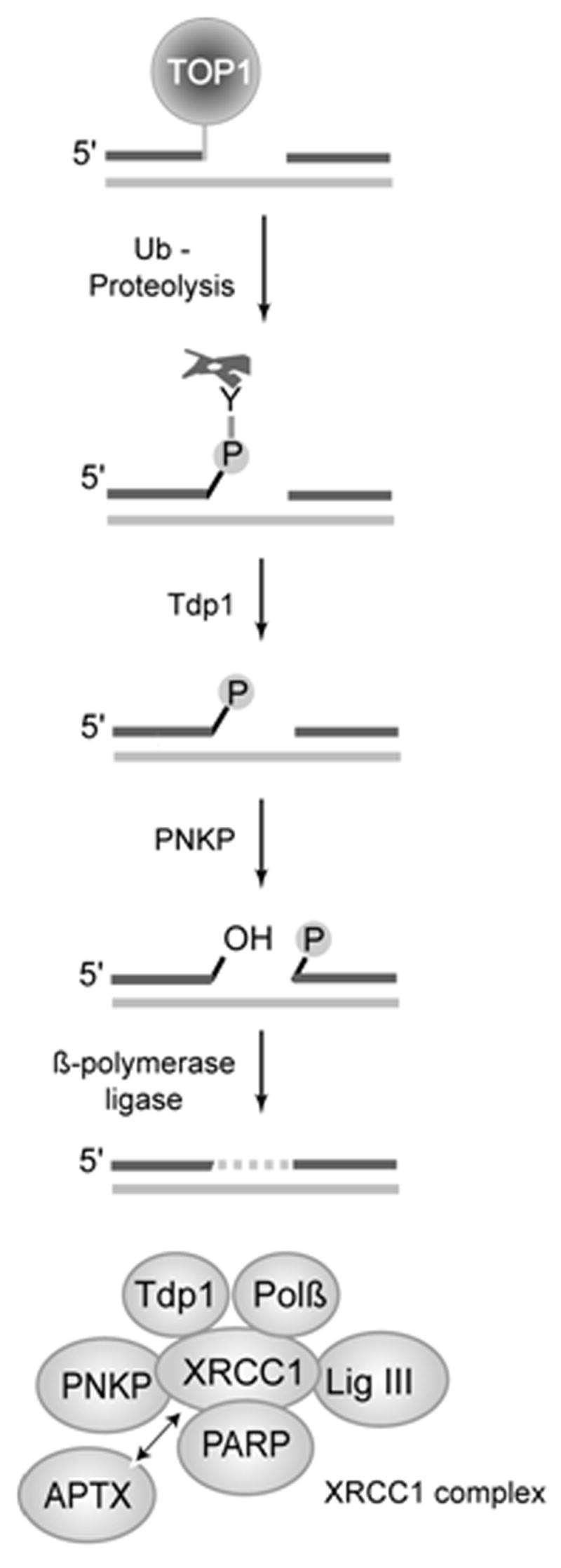

Human tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase I (Tdp1) is a newly discovered enzyme involved in the repair of DNA lesions created by the trapping of human topoisomerase I (Top1) on DNA. Top1 can be trapped by abasic sites, oxidative and methylation base damage, carcinogenic adducts and strand breaks (3) or following treatment by anticancer agents such as camptothecins and indenoisoquinolines [for review see, (1,2)]. Tdp1 belongs to the phospholipase D superfamily (4) and was discovered by Nash and coworkers (5) as the enzyme capable of hydrolyzing the covalent bond between the Top1 catalytic tyrosine and the 3′-end of the DNA (6). The hydrolysis leads to a 3′-phosphate DNA end, which is further processed by a 3′-phosphatase called polynucleotide kinase phosphatase (PNKP) (Fig. 1). In humans, Tdp1 and PNKP form a multiprotein complex with XRCC1, poly(ADP)ribose-polymerase (PARP), β-polymerase and ligase III (7,8) (Fig. 1, bottom). This complex contains the critical elements for base excision repair.

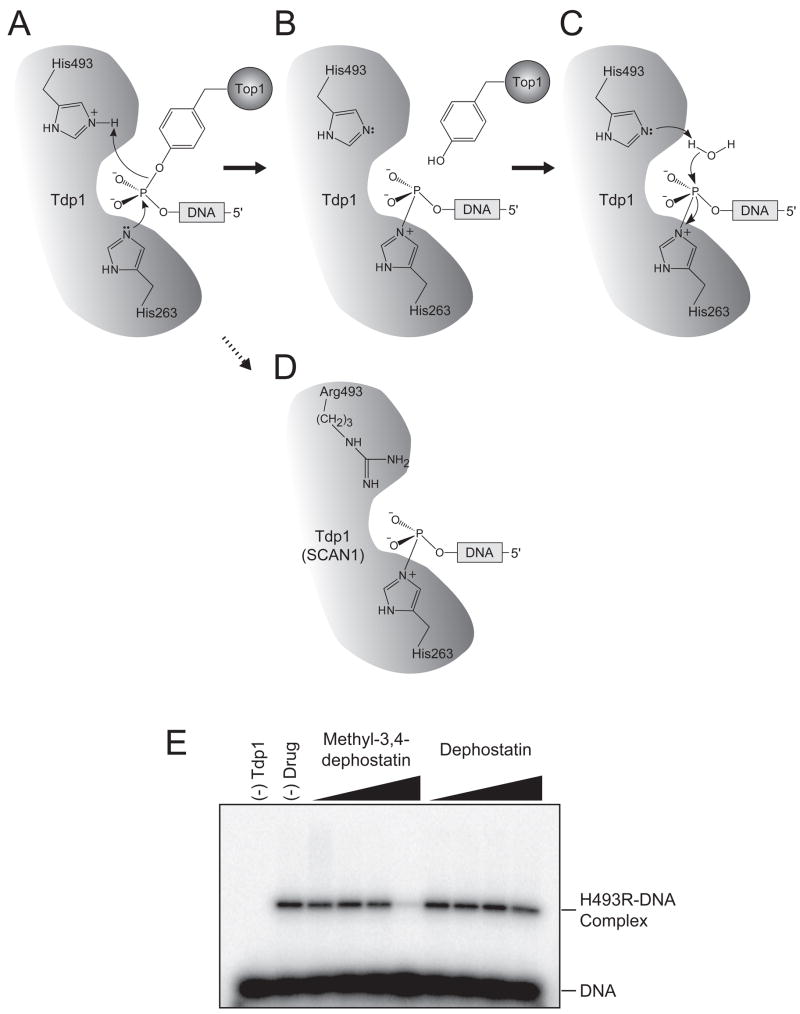

Figure 1. Function of Tdp1.

Topoisomerase 1 (Top1) excision by tyrosyl DNA phosphodiesterase 1 (Tdp1) requires prior proteolysis (41) or denaturation (21) of Top1 to expose the phosphotyrosyl bond to be attacked. Tdp1 generates a 3′-phosphate DNA end, which is hydrolyzed by polynucleotide kinase phosphatase (PNKP). PNKP also catalyzes the phosphorylation of the 5′ end of the DNA. Tdp1 and PNKP are part of the XRCC1 complex (shown at the bottom) (2,7).

Tdp1 is ubiquitous in eukaryotes and physiologically important since the homozygous mutation H493R in its catalytic pocket causes spinocerebellar ataxia with axonal neuropathy (SCAN1) (10). This mutation inactivates Tdp1 by trapping Tdp1-DNA intermediates (11). SCAN1 cells are hypersensitive to camptothecin (8,11–14) and ionizing radiation (15), but not to etoposide or bleomycin (11). The budding yeast TDP1 knock-out is viable (5) and hypersensitive to camptothecin only when the checkpoint gene Rad9 is simultaneously inactivated (16) or when some endonuclease repair pathways (Rad1/Rad10 and Slx1/Slx4) are defective (17–19). Tdp1 function is probably not limited to the repair of Top1 cleavage complexes as it could also be involved in the repair of DNA lesion created by the trapping of topoisomerase II (12,20). Tdp1 can also remove 3′-phosphoglycolate generated by oxidative DNA damage (15,21), suggesting a broader role in the maintenance of genomic stability (22), and making it a rational anticancer target (1).

Aminoglycoside antibiotics and ribosome inhibitors inhibit Tdp1 at millimolar concentrations (23). Vanadate and tungstate act as phosphate mimetics in co-crystal structures and also block Tdp1 activity at millimolar concentrations (24). Furamidine inhibits Tdp1 at micromolar concentrations but may have additional targets due to its DNA binding activities (25). It is therefore rational to develop Tdp1 inhibitors for cancer treatment in combination with camptothecins and indenoisoquinolines. The anticancer activity of Tdp1 inhibitors may prove to be dependent on the presence of cancer-related genetic abnormalities, since hypersensitivity to camptothecin in Tdp1-defective yeast is conditional for deficiencies in the Rad9 checkpoint (see above) (5,17,18), leading one to speculate that Tdp1 is primarily required when checkpoints are deficient.

There is an obvious need to identify new Tdp1-inhibiting chemotypes but simple homogeneous assays amenable to high-throughput screening (HTS) have been lacking. Standard activity assay involves radiolabeled DNA-phosphotyrosine substrates with polyacrylamide gel analysis (6). Though this separation-based approach is thorough, in that both substrate and product are accounted for, it is not suitable for HTS. Screening-friendly schemes have included chromogenic [para-nitrophenyl based (6,26)] and fluorogenic [4-methylumbelliferone based (27)] substrates. However, these assays were either relatively insensitive, requiring high enzyme and substrate levels (to develop the color of the para-nitrophenyl reporter), or utilized an incomplete substrate (the DNA-phospho-4-methylumbelliferyl substrate is missing the tyrosine moiety). Additionally, the fluorogenic assay operated in the blue-shifted region of light detection where the most interference from compound autofluorescence has been shown to occur (28) and the released 4-methylumbelliferone was fluorescent in strictly basic pH environment.

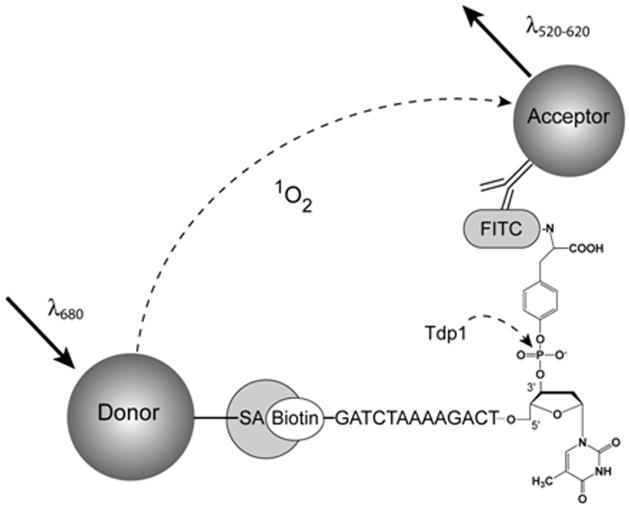

We recently reported an electrochemiluminescent (ECL) assay for the discovery of Tdp1 inhibitors (25). Due to its high cost (over 60 cents per well), its applicability strictly to 96-well format, and its requirement for washing steps and the use of specialized detector, the ECL assay was unsuitable for application in highly-miniaturized automated systems designed to screen millions of samples. Our present approach is based on the use of the AlphaScreen (Amplified Luminescence Proximity Homogenous Assay) bead system, originally designed as an ultrasensitive, low-background immunoassay (29), but nowadays a method which is finding an increased use in HTS. AlphaScreen beads are true colloidal size, hydrophilic and stable, and are processed by liquid dispensers in the same manner as ordinary homogeneous solutions. Upon illumination with 680 nm centered light (see Fig. 2), a phthalocyanine photosensitizer contained within the donor bead converts ambient oxygen molecules in its vicinity to singlet oxygen. The latter can diffuse approximately 200 nm in solution within its 4 μsec half-life. If an acceptor bead is within that proximity, for example as a ternary complex with an analyte and a donor bead, the singlet oxygen can react with and trigger light release from the thioxene, anthracene and rubene derivatives contained within the acceptor bead, ultimately resulting in a light emission in the 520–620 nm range. Due to this unique signal generation mechanism, the AlphaScreen technology offers very high sensitivity in combination with very low background and has been used to configure a wide range of assays, including SNP genotyping and HTS for proteases, cAMP, kinases, inositol phosphatases, and protein-protein interactions. Herein we describe the development of a simple homogeneous AlphaScreen assay for Tdp1 and demonstrate its suitability for large scale high-throughput screening. Further, we report the identification and initial characterization of four inhibitors of the enzyme out of a pilot screen of the LOPAC1280 collection.

Figure 2. Assay Design.

The Tdp1-catalyzed hydrolysis is indicated by an arrow. Upon red-shifted light excitation (λ680) of the donor bead, singlet oxygens are generated. When singlet oxygen encounters an acceptor bead within its traveling range, it triggers the emission of blue-shifted light (λ580–620).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Tween-20, KCl, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), and PBS were procured from Sigma-Aldrich. DMSO certified ACS grade was obtained from Fisher. The AlphaScreen FITC/streptavidin detection kit was from PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences (Waltham, MA). AlphaScreen Assay buffer consisted of PBS, pH 7.4, 80 mM KCl and 0.05% Tween-20. Recombinant Tdp1 was expressed and purified as described previously (25). The Sigma-Aldrich LOPAC1280 library of 1280 known bioactives was received as DMSO solutions at initial concentration of 10 mM and plated as described previously (30,31).

AlphaScreen Substrate

The biotinylated phosphotyrosine deoxyoligonucleotide (5′ biotin-GATCTAAAAGACTT-pY) was synthesized, purified, and QC-tested by Midland Certified Reagent Company, Midland, TX. Standard overnight 4°C FITC coupling was performed in-house. The FITC-labeled substrate was purified on Biospin-6 desalting columns (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and its concentration was determined by UV-vis spectrophotometry.

Assay Development and Optimization

Assay reaction mixtures and substrate/beads titrations were initially performed at 20 μl final volume in 384-well plates. For the subsequent 1,536-well based experiments, Flying Reagent Dispenser (FRD, Aurora Discovery, presently Beckman-Coulter) (32) was used to dispense reagents into the assay plates, while a pintool was used to deliver DMSO solutions of the test inhibitors. Plates were read on Envision plate reader (PerkinElmer) equipped with AlphaScreen optical detection module. For testing the effect of enzyme reaction conditions on the IC50 values for select inhibitors, the respective compounds were prepared as 24-point twofold intra-plate dilution series and assayed as described.

qHTS Protocol and Data Analysis

Three μl of reagents (buffer in columns 3 and 4 as negative control and 1.33 nM Tdp1 in columns 1, 2, 5 – 48) were dispensed into 1,536-well black solid bottom plate. Compounds (final concentrations in the range of 0.7 nM to 57 μM) were transferred via Kalypsys pintool equipped with 1,536-pin array (33). The plate was incubated for 15 min at room temperature, and then 1 μl of substrate (15 nM final concentration) was added to start the reaction. After 5 min incubation at room temperature, 1 μl of bead mix (15 μg/mL final concentration) was added and the plate was further incubated for 10 min at room temperature prior to signal measurement. Substrate and beads were prepared and kept in amber bottles to prevent photo-degradation. Library plates were screened starting from the lowest and proceeding to the highest concentration. Vehicle-only plates, with DMSO being pin-transferred to the entire column 5 – 48 compound area, were included at the beginning and the end of the screen in order to record any systematic shifts in assay signal. Screening data were corrected, normalized, and curve-fitted (34) by using in-house developed algorithms.

Secondary Assays

One nanomolar of 5′-32P-labeled substrate (N14Y; 5′-GATCTAAAAGACTT-Tyrosine-3′) was incubated with 0.1 nM recombinant Tdp1 in the absence or presence of inhibitor for 20 min at 25° C in AlphaScreen assay buffer. Reactions were terminated by the addition of one volume of gel loading buffer (96% (v/v) formamide, 10 mM EDTA, 1% (w/v) xylene cyanol and 1% (w/v) bromphenol blue). The samples were subsequently heated to 95° C for 5 min and subjected to 20% denaturing PAGE. When the Tdp1 mutant H493R (100 nM) was employed, the reactions were stopped with one volume of SDS loading dye and analyzed by 4–20% SDS-PAGE. All gels were dried and exposed on a PhosphorImager screen. Imaging and quantification were done using a Typhoon 8600 and ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ).

RESULTS

Assay Design

To configure a new assay for Tdp1, we utilized the ability of the AlphaScreen system to report on the integrity of the phosphotyrosine-based substrate, viewed here as a multi-site analyte. The AlphaScreen signal is a direct consequence of the close proximity of donor and acceptor beads, which is achieved by the formation of a ternary donor-analyte-acceptor recognition complex. To realize the AlphaScreen assay using the DNA-pY substrate for Tdp1, 5′GATCTAAAAGACTTpY (7,23,25), recognition elements for both bead types had to be introduced. To this end, we coupled a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) to the amino group of tyrosine in a phosphotyrosine-containing single-stranded DNA substrate bearing a biotin at its 5′-end (Fig. 2). Thus, intact substrate, when mixed with streptavidin-donor and anti-FITC antibody-acceptor beads, was expected to yield a high AlphaScreen signal, while the Tdp1-catalyzed substrate hydrolysis would result in a decreased signal. Conversely, if the Tdp1 catalysis was inhibited, an elevated signal would be observed for that sample.

Assay Set-up and Optimization in 384-well Plates

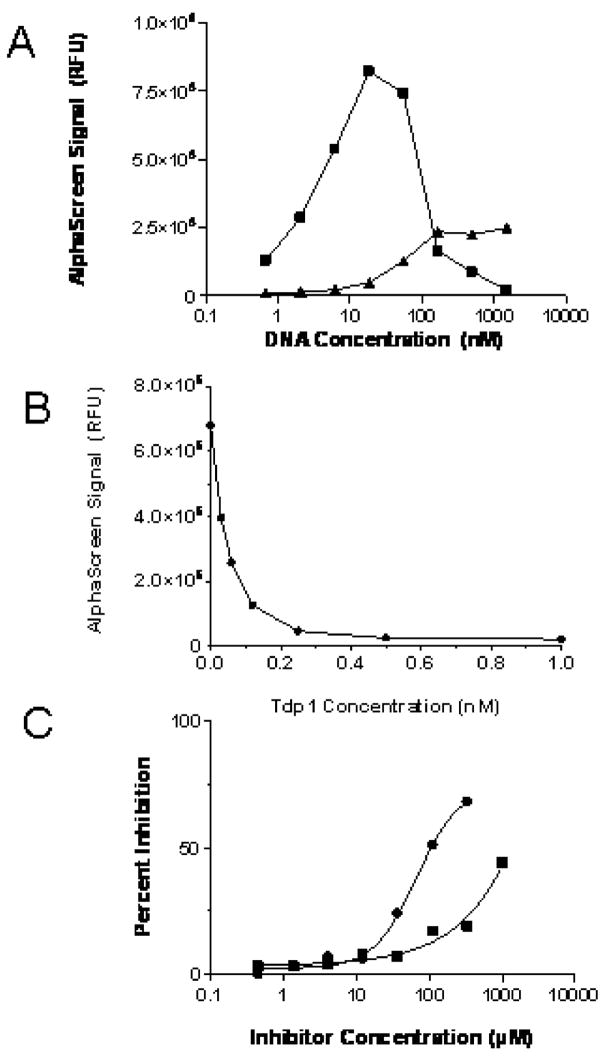

In a 384-well plate, the addition of an equimolar mix of anti-FITC-acceptor and streptavidin-donor AlphaScreen beads to FITC-DNA substrate generated a strong signal while omission of substrate resulted in background readings. The concentration-response curve of the FITC-DNA substrate titrated against constant bead concentration (Fig. 3A) exhibited a maximum around 15 nM followed by a signal decrease to background levels as the substrate concentration was further increased. The biphasic behavior is characteristic of such polyvalent interactions and in this case was due to the saturation of all available binding sites on the beads and the built-up of bipartite populations of beads saturated exclusively by substrate molecules at the expense of tripartite donor-substrate-acceptor assemblies. The maximum-signal concentration of 15 nM falls below the previously reported Km value of Tdp1 of 80 ± 20 nM (35), thus ensuring good assay sensitivity with respect to potential inhibitors.

Figure 3. Assay Optimization.

A) Signal generated by increasing concentration of AlphaScreen Tdp1 DNA substrate (squares) and Tdp1 DNA substrate lacking the 3′ FITC (triangles). B) Detection of substrate cleavage in the presence of increasing concentrations of Tdp1. C) Inhibition of Tdp1 by vanadate (circles) and neomycin (squares).

When the same-sequence construct devoid of FITC was tested, a weak and considerably right-shifted signal evolution was noted (Fig. 3A). While this result points to some non-specific binding, the contribution of the latter to the total signal at the 15 nM point appears to be minimal. Moreover, the Tdp1-induced cleavage of the FITC-DNA substrate, when driven to completion, yielded background signal (Fig. 3B), thus indicating that the small signal increase observed here was likely due to the interaction between the acceptor bead and the tyrosine moiety. In the presence of increasing concentrations of Tdp1, the FITC-coupled tyrosine group was released, preventing anti-FITC acceptor bead positioning close to the donor bead and subsequently leading to an enzyme-dependent loss of signal (Fig. 3B). DMSO had no effect on the enzymatic reaction (data not shown). Neomycin and vanadate, two previously described weak Tdp1 inhibitors, both inhibited Tdp1 in this assay (Fig. 3C). The test method and reaction conditions of the original studies of neomycin and vanadate (23,24) differ from those used in the present assay; nevertheless, the potencies of the two compounds determined here were in agreement with these prior publications, with neomycin being a weak low-millimolar inhibitor and vanadate exhibiting its inhibition in the sub-millimolar range.

Assay Optimization in 1536-well Format and Pilot Screens of the LOPAC1280 Collection

The assay was further miniaturized to a final volume of 5 μl in 1,536-well format by direct volume reduction. The inclusion of Tween-20 in the assay buffer helped prevent enzyme absorption to the polystyrene wells and minimized the interfering effect of promiscuous inhibitors acting via colloidal aggregate formation (36). In order to verify assay integrity over the intended timeline for automated robotic screening, reagent stability over time was assessed by running the assay at multiple time points while storing the working reagents at 4°C. Reagents remained stable for almost 2 days of storage (Fig. S1), considerably beyond the overnight period needed for a robotic screen.

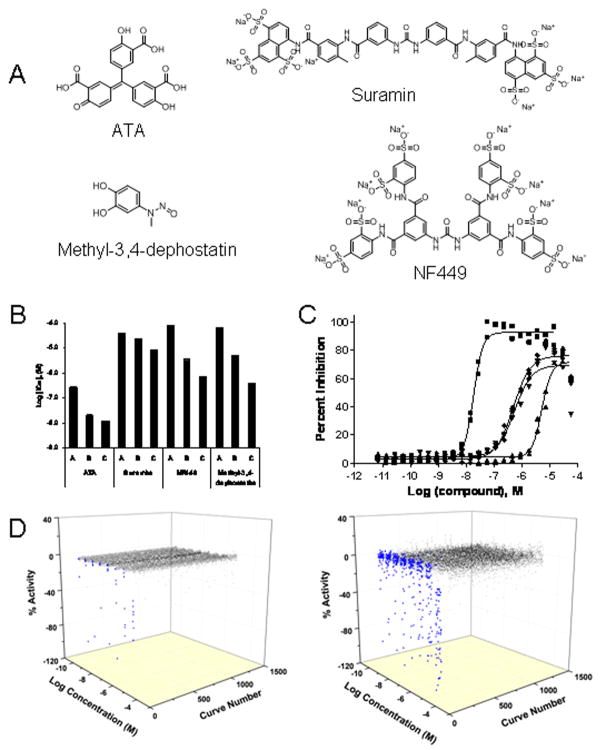

To further validate the present assay in a real 1536-well based HTS context, the LOPAC1280 Library of Pharmacologically Active Compounds was screened in qHTS mode as eight-point concentration series (30,31). The pilot screen performed robustly, yielding average Z′ factor (37) of 0.71. After data analysis, four active compounds were selected for further studies. These included the highly-potent aurintricarboxylic acid (ATA), the known protein tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor methyl-3,4-dephostatin, and the Gα-specific G-protein antagonists suramin and NF449 (Fig. 4A). In enzyme turnover assays, the extent of substrate conversion plays a role in determining the assay sensitivity toward inhibitors. Figure 4B shows the IC50 potencies of the four inhibitors identified from the above pilot screen, as a function of changing reaction conditions designed to achieve a gradual decrease in the fraction of substrate consumed. For all four inhibitors, a significant downward shift in IC50 was observed upon progression to the assay with the lowest substrate conversion (IC50 trends in Fig. 4B and concentration-response curves derived from condition C in Fig. 4C), in agreement with published analyses (38). As expected, a second pilot screen, run at the more sensitive assay conditions, resulted in the appearance of additional actives (Fig. 4D, right panel versus left panel), all of which were less potent than the originally-identified four compounds.

Figure 4. LOPAC1280 Screens in 1536-well Plates.

A) Structures of the four hits identified from the pilot screen. B) The hits were tested in dose-response under three reaction conditions: 1 nM enzyme and 5 minute reaction (condition A), 1 nM enzyme and 2 minute reaction (condition B), and 0.2 nM enzyme and 2 minute reaction (condition C). As the substrate conversion decreased, a progressive decrease in IC50 values was observed for all four inhibitors. C) Dose-response curves of the hits tested under condition C. Shown from left to right are the responses for ATA (squares), methyl-3,4-dephostatin (rhombs), NF449 (inverted triangles), and suramin (triangles). D) 3-D scatter plots of qHTS data lacking (black) or showing (blue) concentration–response relationships are shown for the screens of the LOPAC1280 collection performed under conditions of high (left plot, reaction condition A) and low (right plot, reaction condition C) substrate conversion. The increased sensitivity of the second screen is evident from the increase in the number of samples showing stronger inhibition (blue dots).

Hit Validation by Secondary Assays and Mechanistic Studies of methyl-3,4-dephostatin

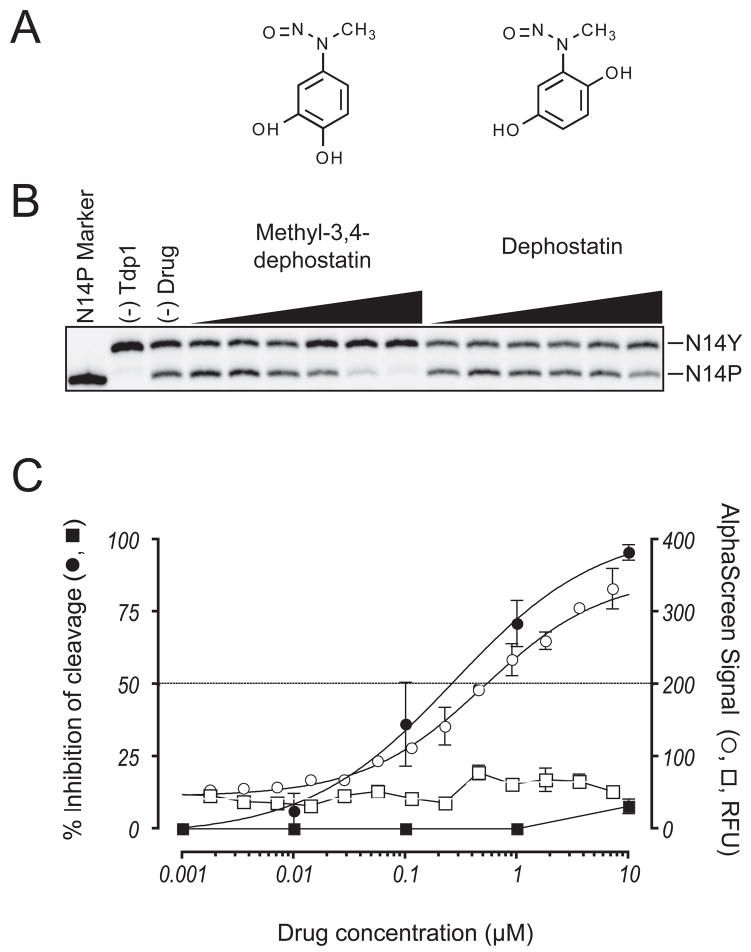

The four inhibitors were purchased separately and tested in secondary radiolabel gel-based assays (22,24). All were found to be active against recombinant Tdp1 enzyme. Methyl-3,4-dephostatin, a stable analog of the nitrosoaniline dephostatin (Fig. 5A) inhibited Tdp1 in our gel-based assay with an IC50 value of 0.36 ± 0.20 μM (Fig. 5B & C). In contrast, dephostatin, which differs from methyl-3,4-dephostatin by the position of one of its hydroxyl groups (Fig. 5A), displayed only a trace level of inhibition within the same concentration range (Fig. 5B & C), suggesting that specific structure modification on the nitrosoaniline motif is sufficient to determine Tdp1 inhibition. The inhibition curves obtained for methyl-3,4-dephostatin in both the primary and the secondary assay had a similar shape and were almost superimposable (Fig. 5C). These results demonstrate the high sensitivity of the Tdp1 AlphaScreen assay and further validate it biochemically, with its output being comparable to that of conventional separation-based assays.

Figure 5. Hit confirmation and characterization in gel-based secondary assay.

A) Structures of methyl-3,4-dephostatin and dephostatin. B) Representative gel image demonstrating dose-dependent inhibition by methyl-3,4-dephostatin. C) Inhibition curves for methyl-3,4 dephostatin (circles) and dephostatin (squares) derived from gels similar to the one presented in panel B (closed symbols) and from follow-up experiments using the HTS assay (open symbols). Error bars represent SEM from at least 3 independent experiments for the gel assays and SEM from duplicates for the AlphaScreen assays.

To gain additional insight into the mechanism of action of methyl-3,4 dephostatin, experiments were carried out using the SCAN1 mutant of Tdp1 (10). This mutant bears an H493R substitution affecting one of the two catalytic histidine residues [for review see Figure 3 in (1)]. The two catalytic histidines, H263 and H493, participate sequentially in the Tdp1 cleavage reaction. H263 is first responsible for the nucleophilic attack on the phosphotyrosyl bond while H493 donates a proton to the tyrosyl-peptide-leaving group (Fig. 6A). The resulting transient Tdp1-DNA covalent complex (Fig. 6B) is then hydrolyzed by a water molecule activated by H493 (Fig. 6C). It has been shown that this transient Tdp1-DNA complex accumulates in SCAN1 cells (Fig. 6D) and suggested that this Tdp1 trapping could be responsible for the SCAN1 phenotype (11,39). We took advantage of this characteristic of the SCAN1 Tdp1 mutant to investigate whether an inhibitor acts before or after Tdp1 forms a transient covalent intermediate with DNA (Fig. 6B). When incubated with the H493R Tdp1 mutant, methyl-3,4 dephostatin completely prevented the accumulation of the covalent Tdp1-DNA intermediate at 10 μM concentration (estimated IC50 of 3 μM), whereas dephostatin had a much weaker effect at this concentration (Fig. 6E). This result suggests that methyl-3,4-dephostatin likely interacts with Tdp1 before the enzyme forms a transient covalent intermediate with DNA and therefore interferes with the binding of the DNA substrate inside the Tdp1 catalytic site.

Figure 6. SCAN1 Tdp1 mutant binding experiments.

The reaction catalyzed by Tdp1 is a two-step process in which the two catalytic histidine residues (H263 & H493) participate sequentially. A) The first step involves the nucleophilic attack of the phosphotyrosyl bond by the H263 residue and the donation of a proton by the H493 residue to the tyrosine-containing peptide-leaving group. B) This results in the formation of a transient covalent Tdp1-DNA intermediate. C) The H493 residue then activates a water molecule to hydrolyze the covalent intermediate. D) The presence of the SCAN1 H493R Tdp1 mutation leads to the accumulation of the covalent Tdp1-DNA intermediate. E) Representative SDS-PAGE gel showing the inhibition of Tdp1H493R-DNA complex formation by methyl-3,4-dephostatin.

DISCUSSION

Tdp1 catalyzes the hydrolysis of a variety of substrates, including 3′-phosphotyrosyl oligonucleotides, protein-DNA 3′-phosphoamide linkages, and 3′-phosphoglycolate adducts (15,21). A major biological function ascribed to Tdp1 is the liberation of genomic DNA from the covalently-trapped Top1 to allow further repair of the strand break by repair enzymes such as polynucleotide kinase 3′-phosphate (PNKP) in the base excision repair and single-strand break repair pathways (40). A point mutation in the Tdp1 gene is responsible for the SCAN1 disorder where cells exhibit hypersensitivity to Top1 inhibitors (8,11,14) suggesting that inhibitors of Tdp1 could be used in association with Top1 inhibitors in a combined anticancer therapeutic regimen. Tdp1 has been shown to preferentially process short oligonucleotide DNA substrates with an exposed 3′-phosphotyrosyl bond (Top1-DNA junction) (2,6,41). Thus, in order to design the most relevant assay for Tdp1, the DNA-pY-Top1 consensus sequence 5′GATCTAAAAGACTTpY was used (7). The need to use the substrate at nanomolar concentrations (close to the 50–100 nM Km range reported for Tdp1 (35), in order to maintain assay sensitivity) meant that the sensor component(s) to be utilized in this assay had to both possess high affinity and to afford high signal amplification.

The AlphaScreen system fulfilled the above requirements and appeared to be superior to traditional dual-label FRET (fluorescence resonance energy transfer) or donor-quencher based approaches. For a successful FRET assay, fluorophore and acceptor need to be matched in terms of excitation and emission; additionally, the strong dependence of FRET signal on the precise distance between donor and acceptor labels necessitates investigation of multiple candidate substrates. Lastly, due to the nature of the substrate, the labeling of the latter with two tags at varying locations to explore the best FRET pair is not synthetically feasible and might result in constructs not accepted by Tdp1 as substrates (Marchand and Simeonov, unpublished observations). On the other hand, an AlphaScreen format appeared feasible for this biochemical system due to the relaxed distance requirements for donor and acceptor bead binding: even if fully stretched in solution, the length of a terminally-labeled 14-mer phosphotyrosine-oligo substrate (approximately 5 nm) was expected to be well within the diffusion distance of singlet oxygen of approximately 200 nm (29).

The Tdp1 AlphaScreen substrate had to contain recognition elements for the donor and acceptor beads such that the Tdp1-dependent event of phosphate bond hydrolysis could be reported on. The previously utilized 5′-biotin was the natural choice for the donor bead attachment due to both the ease of 5′-biotin incorporation during oligo synthesis and the availability of streptavidin-coated donor beads as a standard reagent. On the phosphotyrosine end of the substrate, we surmised that the tyrosine free amine was both most distal to the phosphodiester bond and offered the opportunity for standard conjugation chemistries. In choosing a recognition pair for that site, we were similarly guided by the desire to use as many standard reagents as possible. We thus selected a fluorescein label in combination with anti-fluorescein antibody-coated acceptor bead due to the availability of the latter as a standard catalogue item. The excellent reproducibility and reagent stability associated with the assay make it especially suitable for high-throughput screening. Furthermore, the AlphaScreen format did appear to be less susceptible to light interference as the large number of colored and fluorescent compounds known to be present in the LOPAC1280 collection (28) failed to produce activity in this assay.

The present studies led to the identification of several potent new inhibitors of Tdp1. Aurintricarboxylic acid (ATA, IC50 of 12 nM) has been noted in the literature as a potent inhibitor of a variety of DNA-interacting enzymes. As such, its identification was not unexpected but rather served as an additional biochemical validation of the assay. The other three inhibitors vary in potency but all bear resemblance to the phosphotyrosine-oligo substrate. While the exact mechanism of Tdp1 inhibition by suramin, NF449 and methyl-3,4-dephostatin has yet to be established, it appears unlikely that these compounds act as single-stranded DNA binders. Suramin blocks the binding of various growth factors, including insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I), epidermal growth factor (EGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and tumor growth factor-beta (TGF-beta), to their receptors, thereby inhibiting endothelial cell proliferation and migration (43). Both suramin and its analogue NF449 have been recognized as Gsα-selective G protein (44) and P2 receptor antagonists (45). Herein, they may be acting as decoys as Tdp1 may perceive their extended sulfone group network as multiple phosphotyrosine sites.

The nitrosoaniline methyl-3,4-dephostatin is a stable analog of dephostatin and is the smallest of the four active compounds (Fig. 4A & 5A); of note, it is considerably more potent than vanadate and neomycin (23). Dephostatin and its analog are known protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) inhibitors (46,47) that also probably act as phosphotyrosine mimetics. Methyl-3,4-dephostatin, in contrast to dephostatin, does not inhibit CD-45 associated PTP, pointing to the exclusivity of the respective binding site. We found that methyl-3,4-dephostatin inhibited Tdp1 at sub-micromolar concentration in both the primary and secondary assays (Fig. 5B & C), and therefore represents the most potent Tdp1 inhibitor reported to date. Dephostatin itself was not identified as a hit in our pilot screen and showed only trace inhibition when procured subsequently and tested in both the AlphaScreen HTS assay and the secondary assay (Fig. 5C). Therefore, dephostatin could be of value as a negative-control counterpart of me-3,4-dephostatin when these compounds are used as small molecule probes of Tdp1 mechanism and function.

To probe which step of the catalytic reaction was inhibited by methyl-3,4-dephostatin [i.e. cleavage of the phosphotyrosyl group (Fig. 6A & B) or release of the DNA from the transient covalent complex (Fig. 6B & C)], DNA trapping experiments were performed using the SCAN1 Tdp1 mutant (11). The results indicate that methyl-3,4-dephostatin interferes with the early catalytic step, the binding of the Tdp1 DNA substrate, whereas dephostatin has almost no effect on this activity. These marked differences in potency for the two isomers (Fig. 5A), suggest that the position of the two hydroxyls on the nitrosoaniline motif is critical for Tdp1 inhibition.

In summary, we have developed a robust 1536-well based assay for the identification of inhibitors of Tdp1. The assay utilizes commercially available common reagents and what we believe to be the most active-site relevant Tdp1 substrate reported to date. The general assay scheme presented here should be applicable to the testing of other DNA repair enzymes where a cleavage step is involved. Furthermore, the assay is tunable and responsive to a wide range of inhibitor potencies, and its low cost of approximately 3 cents per well makes it attractive for both large-scale automated HTS and secondary screening. Methyl-3,4-dephostatin was identified from our pilot qHTS and represents the most potent Tdp1 inhibitor known to date. Extended SAR studies on dephostatin analogs are warranted in order to further understand the mechanism of action of methyl-3,4-dephostatin and determine its value as a Tdp1 lead inhibitor.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the Molecular Libraries Initiative of the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research and the Intramural Research Program of the NHGRI, NIH, and by the Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, NIH. The research presented here was also funded in part by a 2007 National Cancer Institute Director’s Intramural Innovation Award to CM. The SCAN1 mutant Tdp1 construct was a generous gift from Drs J. J. Champoux (University of Washington) and H. Interthal (University of Edinburgh). We thank Carl Apgar for expert advice during the initial adoption of the AlphaScreen assay.

References

- 1.Dexheimer TS, Antony S, Marchand C, Pommier Y. Tyrosyl-DNA Phosphodiesterase as a Target for Anticancer Therap. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2008;8:381–389. doi: 10.2174/187152008784220357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pommier Y, Barcelo JM, Rao VA, Sordet O, Jobson AG, Thibaut L, Miao ZH, Seiler J, Zhang H, Marchand C, et al. In: Progress in Nucleic Acids Research and Molecular Biology. Moldave K, editor. Vol. 81. Academic Press; 2006. pp. 179–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pommier Y, Redon C, Rao A, Seiler JA, Sordet O, Takemura H, Antony S, Meng LH, Liao ZY, Kohlhagen G, et al. Repair of and Checkpoint Response to Topoisomerase I-Mediated DNA Damage. Mutat Res. 2003;532:173–203. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Interthal H, Pouliot JJ, Champoux JJ. The tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase Tdp1 is a member of the phospholipase D superfamily. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12009–12014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211429198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pouliot JJ, Yao KC, Robertson CA, Nash HA. Yeast gene for a Tyr-DNA phosphodiesterase that repairs topo I covalent complexes. Science. 1999;286:552–555. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang SW, Burgin AB, Huizenga BN, Robertson CA, Yao KC, Nash HA. A eukaryotic enzyme that can disjoin dead-end covalent complexes between DNA and type I topoisomerases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11534–11539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plo I, Liao ZY, Barcelo JM, Kohlhagen G, Caldecott KW, Weinfeld M, Pommier Y. Association of XRCC1 and tyrosyl DNA phosphodiesterase (Tdp1) for the repair of topoisomerase I-mediated DNA lesions. DNA Repair (Amst) 2003;2:1087–1100. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(03)00116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Khamisy SF, Saifi GM, Weinfeld M, Johansson F, Helleday T, Lupski JR, Caldecott KW. Defective DNA single-strand break repair in spinocerebellar ataxia with axonal neuropathy-1. Nature. 2005;434:108–113. doi: 10.1038/nature03314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatterjee S, Cheng MF, Trivedi D, Petzold SJ, Berger NA. Camptothecin hypersensitivity in poly(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase-deficient cell lines. Cancer Commun. 1989;1:389–394. doi: 10.3727/095535489820875129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takashima H, Boerkoel CF, John J, Saifi GM, Salih MA, Armstrong D, Mao Y, Quiocho FA, Roa BB, Nakagawa M, et al. Mutation of TDP1, encoding a topoisomerase I-dependent DNA damage repair enzyme, in spinocerebellar ataxia with axonal neuropathy. Nat Genet. 2002;32:267–272. doi: 10.1038/ng987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Interthal H, Chen HJ, Kehl-Fie TE, Zotzmann J, Leppard JB, Champoux JJ. SCAN1 mutant Tdp1 accumulates the enzyme--DNA intermediate and causes camptothecin hypersensitivity. Embo J. 2005;24:2224–2233. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barthelmes HU, Habermeyer M, Christense MO, Mielke C, Inthertal H, Pouliot JJ, Boege F, Marko D. TDP1 overexpression in human cells counteracts DNA damage mediated by topoisomerases I and II. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:55618–55625. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405042200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nivens MC, Felder T, Galloway AH, Pena MM, Pouliot JJ, Spencer HT. Engineered resistance to camptothecin and antifolates by retroviral coexpression of tyrosyl DNA phosphodiesterase-I and thymidylate synthase. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2004;53:107–115. doi: 10.1007/s00280-003-0717-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miao ZH, Agama K, Sordet O, Povirk L, Kohn KW, Pommier Y. Hereditary ataxia SCAN1 cells are defective for the repair of transcription-dependent topoisomerase I cleavage complexes. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5:1489–1494. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou T, Lee JW, Tatavarthi H, Lupski JR, Valerie K, Povirk LF. Deficiency in 3′-phosphoglycolate processing in human cells with a hereditary mutation in tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase (TDP1) Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:289–297. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pouliot JJ, Robertson CA, Nash HA. Pathways for repair of topoisomerase I covalent complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Cells. 2001;6:677–687. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu C, Pouliot JJ, Nash HA. Repair of topoisomerase I covalent complexes in the absence of the tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase Tdp1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14970–14975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182557199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vance JR, Wilson TE. Yeast Tdp1 and Rad1-Rad10 function as redundant pathways for repairing Top1 replicative damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13669–13674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202242599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deng C, Brown JA, You D, Brown JM. Multiple endonucleases function to repair covalent topoisomerase I complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2005;170:591–600. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.028795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nitiss KC, Malik M, He X, White SW, Nitiss JL. Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase (Tdp1) participates in the repair of Top2-mediated DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8953–8958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603455103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Interthal H, Chen HJ, Champoux JJ. Human Tdp1 cleaves a broad spectrum of substrates including phosphoamide linkages. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:36518–36528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508898200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inamdar KV, Pouliot JJ, Zhou T, Lees-Miller SP, Rasouli-Nia A, Povirk LF. Conversion of phosphoglycolate to phosphate termini on 3′ overhangs of DNA double-strand breaks by the human tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase hTdp1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27162–27168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204688200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liao Z, Thibaut L, Jobson A, Pommier Y. Inhibition of human tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase by aminoglycoside antibiotics and ribosome inhibitors. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:366–372. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.021865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davies DR, Interthal H, Champoux JJ, Hol WG. Insights into substrate binding and catalytic mechanism of human tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase (Tdp1) from vanadate and tungstate-inhibited structures. J Mol Biol. 2002;324:917–932. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01154-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antony S, Marchand C, Stephen AG, Thibaut L, Agama KK, Fisher RJ, Pommier Y. Novel high-throughput electrochemiluminescent assay for identification of human tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase (Tdp1) inhibitors and characterization of furamidine (NSC 305831) as an inhibitor of Tdp1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:4474–4484. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woodfield G, Cheng C, Shuman S, Burgin AB. Vaccinia topoisomerase and Cre recombinase catalyze direct ligation of activated DNA substrates containing a 3′-para-nitrophenyl phosphate ester. Nucleic Acids Research. 2000;28:3323–3331. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.17.3323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rideout MC, Raymond AC, Burgin AB., Jr Design and synthesis of fluorescent substrates for human tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase I. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:4657–4664. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simeonov A, Jadhav A, Thomas C, Wang Y, Huang R, Southall N, Shinn P, Smith J, Austin C, Auld D, et al. Fluorescent Spectroscopic Profiling of Compound Libraries. J Med Chem. 2008;51:2363–2371. doi: 10.1021/jm701301m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ullman EF, Kirakossian H, Switchenko AC, Ishkanian J, Ericson M, Wartchow CA, Pirio M, Pease J, Irvin BR, Singh S, et al. Luminescent oxygen channeling assay (LOCI): sensitive, broadly applicable homogeneous immunoassay method. Clin Chem. 1996;42:1518–1526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inglese J, Auld DS, Jadhav A, Johnson RL, Simeonov A, Yasgar A, Zheng W, Austin CP. Quantitative high-throughput screening: a titration-based approach that efficiently identifies biological activities in large chemical libraries. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11473–11478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604348103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yasgar A, Shinn P, Michael S, Zheng W, Jadhav A, Auld D, Austin C, Inglese J, Simeonov A. Compound Management for Quantitative High-Throughput Screening. J Assoc Lab Automat. 2008;13:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jala.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niles WD, Coassin PJ. Piezo- and Solenoid Valve-Based Liquid Dispensing for Miniaturized Assays. Assay Drug Devel Technol. 2005;3:189–202. doi: 10.1089/adt.2005.3.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cleveland PH, Koutz PJ. Nanoliter dispensing for uHTS using pin tools. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2005;3:213–225. doi: 10.1089/adt.2005.3.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hill AV. The Possible Effects of the Aggregation of the Molecule of Haemoglobin on its Dissociation Curves. J Physiol (London) 1910;40:4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raymond AC, Staker BL, Burgin AB., Jr Substrate Specificity of Tyrosyl-DNA Phosphodiesterase I (Tdp1) J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22029–22035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502148200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feng BY, Simeonov A, Jadhav A, Babaoglu K, Inglese J, Shoichet BK, Austin CP. A high-throughput screen for aggregation-based inhibition in a large compound library. JMed Chem. 2007;50:2385–2390. doi: 10.1021/jm061317y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang JH, Chung TD, Oldenburg KR. A Simple Statistical Parameter for Use in Evaluation and Validation of High Throughput Screening Assays. J Biomol Screen. 1999;4:67–73. doi: 10.1177/108705719900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu G, Yuan Y, Hodge CN. Determining appropriate substrate conversion for enzymatic assays in high-throughput screening. Journal of Biomolecular Screening. 2003;8:694–700. doi: 10.1177/1087057103260050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirano R, Interthal H, Huang C, Nakamura T, Deguchi K, Choi K, Bhattacharjee MB, Arimura K, Umehara F, Izumo S, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia with axonal neuropathy: consequence of a Tdp1 recessive neomorphic mutation? EMBO J. 2007;26:4732–4743. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson DMI. Processing ofNonconventional DNA Strand Break Ends. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2007;48:772–782. doi: 10.1002/em.20346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Debethune L, Kohlhagen G, Grandas A, Pommier Y. Processing of nucleopeptides mimicking the topoisomerase I-DNA covalent complex by tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:1198–1204. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.5.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Macarron R, Hertzberg RP. Design and implementation of high throughput screening assays. Meth Mol Biol. 2002;190:1–29. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-180-9:001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eisenberger MA, Reyno LM. Suramin. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 1994;20:259–273. doi: 10.1016/0305-7372(94)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hohenegger M, Waldhoer M, Beindl W, Boing B, Kreimeyer A, Nickel P, Nanoff C, Freissmuth M. Gsalpha -selective G protein antagonists. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:346–351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hausmann R, Rettinger J, Gerevich Z, Meis S, Kassack MU, Illes P, Lambrecht G, Schmalzing G. The suramin analog 4,4′,4″,4tprime;-(carbonylbis(imino-5,1,3-benzenetriylbis (carbonylimino)))tetra-kis-benzenesulfonic acid (NF110) potently blocks P2X3 receptors: subtype selectivity is determined by location of sulfonic acid groups. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:2058–2067. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.022665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Imoto M, Kakeya H, Sawa T, Chigusa H, Hamada M, Takeuchi T, Umezawa K. Dephostatin, a novel proteintyrosine phosphatase inhibitor produced by Streptomyces. J Antibiotics (Tokyo) 1993;45:1342–1346. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.46.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Umezawa K. Isolation and biological activities of signal transduction inhibitors from microorganisms and plants. Advances in Enzyme Regulation. 1995;35:43–53. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(94)00018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]