Abstract

Background:

Conflicting perspectives about the diagnosis and prognosis of the persistent vegetative state (PVS) as well as end-of-life (EOL) decision-making were disseminated in the Terri Schiavo case. This study examined print media coverage of these features of the case.

Methods:

We retrieved print media coverage of the Schiavo case from the LexisNexis Academic database and used content analysis to examine headlines and text of articles describing Schiavo’s neurologic condition, behavioral repertoire, prognosis, and withdrawal of life support. The accuracy of claims about PVS was assessed.

Results:

Our search yielded 1,141 relevant articles published (1990–2005) in the four most prolific American newspapers for this case. The most frequent headline themes featured legal (31%), EOL (25%), and political (22%) aspects of the case. Of the articles analyzed, 21% reported that Schiavo “might improve” and 7% that she “might recover.” Statements explicitly denying the PVS diagnosis were found in 6% of articles. Explanations of PVS and other chronic disorders of consciousness were rare (≤1%). Most frequently cited descriptions of behaviors were that the patient responds (10%), reacts (9%), is incapacitated (6%), smiles (5%), and laughs (5%). Withdrawal of life support was described as murder in 9% of articles.

Conclusions:

Media coverage included refutations of the persistent vegetative state (PVS) diagnosis, attributed behaviors inconsistent with PVS, and used charged language to describe end of life decision-making. Strategies are needed to achieve better internal agreement within the professional community and effective communication with patient communities, families, the media, and stakeholders.

GLOSSARY

- CDC

= chronic disorders of consciousness;

- EOL

= end-of-life;

- PVS

= persistent vegetative state.

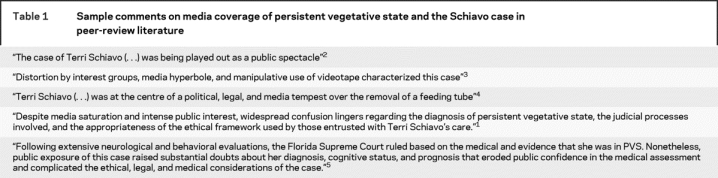

In 1990, Terri Schiavo suffered hypoxic-ischemic brain damage during cardiac arrest and evolved into a persistent vegetative state (PVS).1 Among the abundant scholarly peer reviews of this case, many highlighted the role that the media played in fueling controversy (table 1). Media coverage could have radicalized already tense public debates about end-of-life (EOL) decision-making in PVS and reported conflicting messages about her diagnosis, behavioral repertoire, and prognosis. To gain a deeper understanding of this phenomenon, we reviewed how Schiavo’s neurologic condition, behavioral repertoire, prognosis, and withdrawal of life support were depicted in American print media.

Table 1 Sample comments on media coverage of persistent vegetative state and the Schiavo case in peer-review literature

METHODS

We used the guided news search function of the LexisNexis Academic database with keyword searches to find news articles about the case of Terri Schiavo published in American print media between 1990 and 2005. We selected the four sources with the most prolific coverage of the case. This sample also incorporated a balance of two national elite news sources (The New York Times, The Washington Post) and two regional news sources (The Tampa Tribune, St.-Petersburg Times). Elite sources frequently serve as a basis for the coverage presented by other newspapers in the United States and worldwide.6 The regional Florida state coverage occurred first chronologically.

We ran keyword searches using the expressions “Theresa Schiavo” or “Terri Schiavo” on headlines, lead paragraphs, and body terms to maximize search yields. Articles were screened for relevance and those that did not minimally discuss the case of Terri Schiavo were discarded from the sample. All articles were systematically coded by two independent coders based on the instructions contained in a coding guide. This guide was developed for this study specifically based on the research objectives of this work as well as on previous studies of media coverage of neuroscience principles and technology.7–9 All coding options were generated based on extensive pretesting and the qualitative research principle of theoretical saturation. The final coding structure applied to all articles included the identification of 1) authorship (e.g., report, editorial, press agency); 2) topics featured in the headline (e.g., legal, political, ethical, and EOL decision-making); 3) description of prognosis (e.g., “recover,” “improve”); 4) description of neurologic condition (e.g., persistent vegetative state, brain injury, minimally conscious state); 5) description of behavioral repertoire (e.g., “reacts,” “is aware,” “responds”); 6) description of withdrawal of life support (e.g., “murder,” “peaceful death,” “starvation”). Coding for items 3 through 6 included the identification of who was cited supporting the claim (e.g., Schiavo party [Michael Schiavo, husband of Terri Schiavo, and lawyers representing his views], the Schindler party [family of Terri Schiavo and lawyers representing their views], courts, politicians). We also coded the varying claims about the patient’s condition (e.g., affirmation that Terri Schiavo is in PVS; refutation that she is in PVS; equivocal or divided opinion about her PVS diagnosis). If the content of an article fit in more than one category (e.g., a headline featuring both legal and ethical aspects of the case), it was coded as many times as appropriate to the data (rich coding strategy). A blind test for coding reliability on a subsample of 125 articles yielded a 0.99 intercoder agreement.

We use descriptive statistics to characterize the composition and properties of the sample. We assessed the accuracy of the descriptions of Schiavo’s neurologic condition, behaviors, and prognosis based on common medical understandings of PVS.10–15 This study is part of a larger project that includes a separate analysis of letters to the editor (n = 451) and further analysis of differences between regional and national elite coverage of the case.

RESULTS

We retrieved a total of 1,141 relevant articles published in the St.-Petersburg Times (n = 466; 41%), The Tampa Tribune (n = 351; 31%), The Washington Post (n = 163; 14%), and The New York Times (n = 161; 14%) from 1990 to 2005. Most articles were journalist reports (n = 860; 75%); 173 (15%) were editorials or columns, and 98 (9%) newswire reports. The majority of the coverage occurred in 2005 (n = 634; 56%). Only three articles were published prior to 2000 (all in the St.-Petersburg Times).

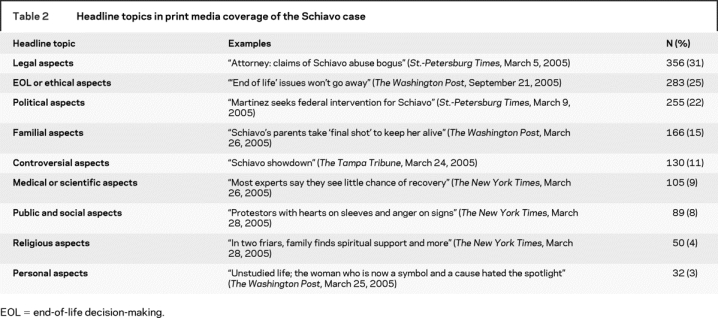

Table 2 presents the most common topics found in headlines of articles covering the Terri Schiavo case. Headline themes most frequently focused on the legal aspects of the case, ethics and EOL issues, and disagreements based on political views. We found medical and scientific aspects of the case, such as information about diagnosis and treatment, in 9% of headlines.

Table 2 Headline topics in print media coverage of the Schiavo case

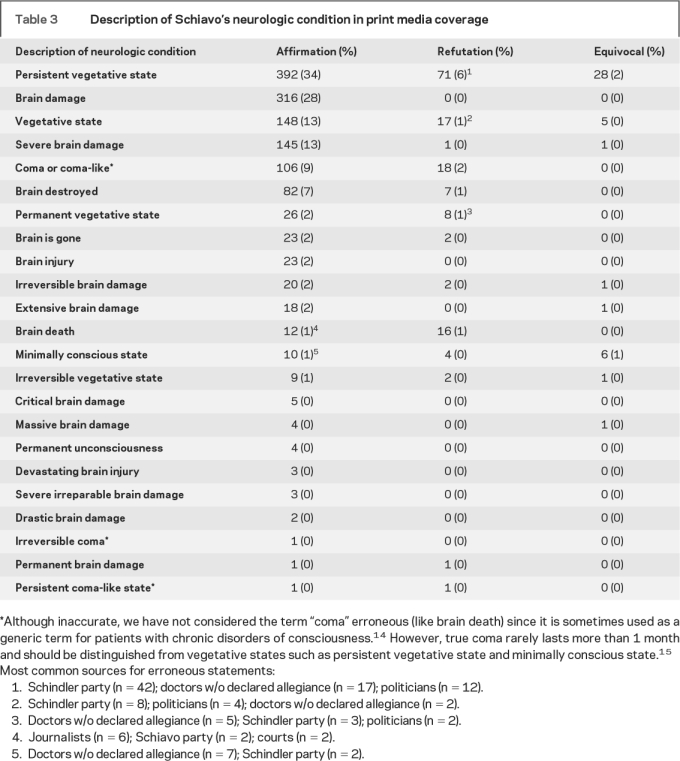

The most frequently used terms to describe Schiavo’s neurologic condition and diagnosis were “persistent vegetative state,” “brain damage,” “vegetative state,” “severe brain damage,” and “coma” (table 3). The term “brain damage” was mostly used by journalists while the term “PVS” was often used by physicians cited in the articles (e.g., “doctors say she’s in PVS”). We found statements denying the PVS diagnosis in 71 (6%) articles and statements claiming that she was brain dead in 12 articles (1%) and minimally conscious in 10 articles (1%). We also found explanations of chronic disorders of consciousness (CDC) like the persistent vegetative state in 16 articles (1.4%), coma in 6 articles (0.5%), the minimally conscious state in 4 articles (0.4%), and brain death (although not a CDC) in a single article (0.1%).

Table 3 Description of Schiavo's neurologic condition in print media coverage

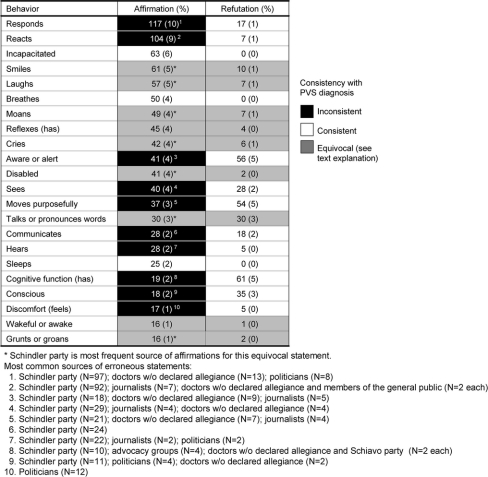

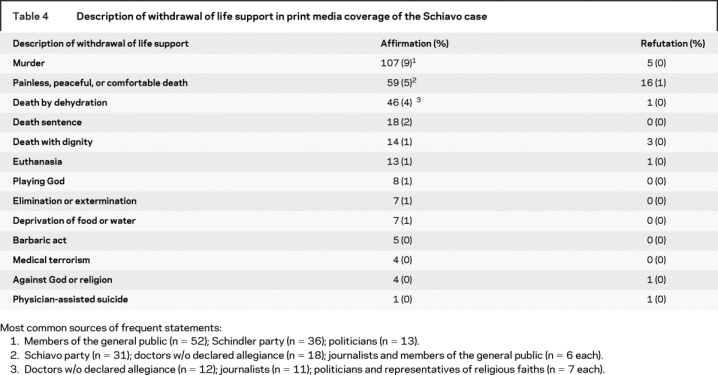

The most common claims about the behavioral repertoire of the patient are shown in the figure. That “she responds” or “she reacts” are clearly inconsistent with PVS (highlighted in black). Other claims (highlighted in gray) that are more consistent with the diagnosis (e.g., she “smiles,” she “laughs”) were used equivocally (e.g., by the Schindlers) to describe meaningful purposeful behaviors instead of sheer reflexive behavior.13–16 The terms used to describe withdrawal of life support are presented in table 4. Many of those terms reflect an objection to the withdrawal of life support described as “murder” or “death by starvation.”

Figure Description of Schiavo’s behaviors in print media coverage and consistency with persistent vegetative state diagnosis

Table 4 Description of withdrawal of life support in print media coverage of the Schiavo case

We found that 237 articles (21%) in our sample contained statements that Schiavo “might improve” and 76 (7%) had statements that she “might recover.” In contrast, 143 (13%) articles included statements that she will not improve and 151 (13%) that she will not recover.

DISCUSSION

This study examined American print media coverage of the Terri Schiavo case to identify challenges in public understanding of PVS and EOL. We specifically focused on the description of Schiavo’s neurologic condition, behavioral repertoire, prognosis, and withdrawal of life support. Key findings are the focus on legal, ethical, and political aspects of the case in headlines, varying descriptions of Schiavo’s neurologic condition, refutations of her diagnosis, attribution of meaningful behaviors inconsistent with the PVS diagnosis, and the use of charged language to describe with-drawal of life support. Overall, explanations of the basic concept of PVS and other CDCs were rare. A limitation of this study is its focus on the print media and only a few, however prolific, American newspapers. We recognize that other forms of media can have an impact on patient behaviors and public understanding of contemporary biomedical science.17,18 However, our design can be justified by the practical availability of databases for newspapers, and the conceptual role that the print media play in the construction of other media such as television and radio.

Given the centrality of the PVS diagnosis in the Schiavo case, our results highlight areas critical for the public understanding of CDCs.15 The results confirm concerns expressed in the peer-review literature that media coverage of the case of Terri Schiavo included both inaccurate statements about her diagnosis and charged language about EOL decision-making.1,3 These observations alone are powerful messages supporting the need for active and concerted collaboration of the medical and bioethics communities to broaden communication and public education about EOL decision-making in PVS. The recent position statement by the American Academy of Neurology on patients lacking decision-making capacity is a welcome step in that direction.19 The data are also consistent with the political and legal pressures that were seen to challenge, if not jeopardize, accepted standards and procedures for EOL decision-making for patients with CDCs. Recently, in response to the turmoil provoked by the Schiavo case, state legislators have proposed bills that challenge standard proxy decision-making. Some bills introduce a default presumption favoring life-sustaining artificial hydration and nutrition in patients lacking capacity unless there is clear and convincing written evidence stating otherwise.19 Such legislation could increase chances that a patient’s previous wishes be disregarded.

The results also illustrate a gap between lay and expert perspectives on EOL decision-making and fundamental aspects of PVS, including the interpretation of behaviors and prognosis. For example, the behavioral repertoire of a patient in PVS like Terri Schiavo can lead to irreconcilable interpretations of specific behaviors. Descriptions of nonpurposeful behaviors as purposeful—smiling, laughing—can cause confusion and misunderstanding.20 The net effect of such statements yields legitimate, but puzzling questions for family members: What is the evidence supporting claims that PVS patients do not feel pain and no not process language? How does new evidence from neuroimaging of CDCs support or refute existing medical views about the diagnosis and recovery of patients in PVS? How are reflexive behaviors distinguished from meaningful ones? The challenges created by potential misunderstandings and misinterpretations of nonmeaningful behaviors of patients in PVS can fuel mistrust toward a medical team.21 Disquieting levels of diagnostic inaccuracy in PVS22–24 and confusion among healthcare providers themselves about the behavioral repertoire of patients in PVS25 could perpetuate a gap between expert and lay understandings of PVS and CDCs.

Even though Schiavo’s chances of recovery were practically nonexistent after years in PVS, claims that she would or might improve or recover were frequent in media coverage. Evidence suggests that recovery from PVS after 3 months in nontraumatic brain injury is rare and recovery after 12 months in traumatic brain injury is seldom encountered.10 Our finding is consistent with results of a study that showed that more than one fifth of family members of brain dead patients still have hope for recovery of their loved ones.26 Some journalists reported that Schiavo might improve or recover based on the claims of physicians, including some tied to the Schindlers, without distinguishing among experts, their credentials, the level of evidence for their claims, or their possible biases. Given this confusion, clarification of the diagnosis of PVS or other CDCs should therefore not be assumed to lead automatically to a clear understanding of neurologic prognosis, especially, when for families, emotional factors and narratives constructed about specific behaviors can interfere with the acceptance of a poor neurologic prognosis.20

The evolution of the Schiavo case and the dissemination of information about it in the media shook the medical, legal, and bioethics communities. Analysis of a sample of American print media reveals that the public has been provided conflicting information about medical diagnosis and prognosis of PVS. Statements conveying false hopes for recovery were disseminated in a general absence of adequate critical examination and background information about PVS and CDCs. Since the media and other forms of public information27 can shape expectations and beliefs about health, pervasive challenges in communication about the diagnosis and prognosis of CDCs are likely to persist in the post-Schiavo era. Indeed, the extensive media coverage in the months preceding Schiavo’s death did not translate into concerted efforts by journalists and the media to educate about the diagnosis and prognosis of CDCs. Even if a few news articles conveyed some explanations and background information, much of the coverage focused on the controversial political and legal aspects of the case. Our results support the need for research into strategies that will lead to better internal agreement within the professional community and effective communication with patient communities, families, and stakeholders that the professional community serves.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Nicole Palmour, Zoë Costa-von Aesch, Amaryllis Ferrand, and Vivian Chau for assistance.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Eric Racine, Director, Neuroethics Research Unit, IRCM, 110 Pine Avenue West, Montreal, Quebec, Canada H2W 1R7 Eric.racine@ircm.qc.ca

Editorial, page 964

e-Pub ahead of print on August 6, 2008, at www.neurology.org.

Supported by NIH/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke RO1 #NS045831-04 (J.I.), the Institut de recherches cliniques de Montréal (E.R.), the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (E.R.), and The Greenwall Foundation (J.I.).

Disclosure: The authors report no disclosures.

Received December 10, 2007. Accepted in final form May 2, 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Perry JE, Churchill LR, Kirshner HS. The Terri Schiavo case: legal, ethical, and medical perspectives. Ann Intern Med 2005;143:744–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Annas GJ. “Culture of life politics” at the bedside: the case of Terri Schiavo. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1710–1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quill TE. Terri Schiavo: a tragedy compounded. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1630–1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weijer C. A death in the family: reflections on the Terri Schiavo case. CMAJ 2005;172:1197–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirsch J. Raising consciousness. J Clin Invest 2005;115:1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ten Eyck TA, Williment M. The national media and things genetic. Sci Commun 2003;25:129–152. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mountcastle-Shah E, Tambor E, Bernhardt BA, et al. Assessing mass media reporting of disease-related genetic discoveries. Sci Commun 2003;24:458–478. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Racine E, Bar-Ilan O, Illes J. fMRI in the public eye. Nat Rev Neurosci 2005;6:159–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Racine E, Bar-Ilan O, Illes J. Brain imaging: a decade of coverage in the print media. Sci Commun 2006;28:122–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Multi-Society Task Force on PVS. Medical aspects of the persistent vegetative state (2). N Engl J Med 1994;330:1572–1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Multi-Society Task Force on PVS. Medical aspects of the persistent vegetative state (1). N Engl J Med 1994;330:1499–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giacino JT, Ashwal S, Childs N, et al. The minimally conscious state: definition and diagnostic criteria. Neurology 2002;58:349–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laureys S, Owen AM, Schiff ND. Brain function in coma, vegetative state, and related disorders. Lancet Neurol 2004;3:537–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevens RD, Bhardwaj A. Approach to the comatose patient. Crit Care Med 2006;34:31–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernat JL. Chronic disorders of consciousness. Lancet 2006;367:1181–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Academy of Neurology. Position of the American Academy of Neurology on certain aspects of the care and management of the persistent vegetative state. Neurology 1989;39:125–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berger M, Wagner TH, Baker LC. Internet use and stigmatized illness. Soc Sci Med 2005;61:1821–1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Racine E, Van der Loos HZA, Illes J. Internet marketing of neuroproducts: new practices and healthcare policy challenges. Cam Q Healthc Ethics 2007;16:181–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bacon D, Williams MA, Gordon J. Position statement on laws and regulations concerning life-sustaining treatment, including artificial nutrition and hydration, for patients lacking decision-making capacity. Neurology 2007;68:1097–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernat JL. Ethical aspects of determining and communicating prognosis in critical care. Neurocrit Care 2004;1:107–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fins JJ. Rethinking disorders of consciousness: new research and its implications. Hastings Cent Rep 2005;35:22–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Childs NL, Mercer WN, Childs HW. Accuracy of diagnosis of persistent vegetative state. Neurology 1993;43:1465–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrews K, Murphy L, Munday R, Littlewood C. Misdiagnosis of the vegetative state: retrospective study in a rehabilitation unit. BMJ 1996;313:13–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson FC, Harpur J, Watson T, Morrow JI. Vegetative state and minimally responsive patients–regional survey, long-term case outcomes and service recommendations. NeuroRehabilitation 2002;17:231–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Payne K, Taylor RM, Stocking C, Sachs GA. Physicians’ attitudes about the care of patients in the persistent vegetative state: a national survey. Ann Intern Med 1996;125:104–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siminoff LA, Mercer MB, Arnold R. Families’ understanding of brain death. Prog Transplant 2003;13:218–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mettner J. Lights, coma, action. Minn Med 2006;89:12–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]