Abstract

Monoclonal antibodies have emerged as effective therapeutic agents for many human malignancies. However, the ability of antibodies to initiate tumor antigen-specific immune responses has not received as much attention as other mechanisms of antibody action. Here we describe the rationale and evidence for developing anti-cancer antibodies that can stimulate host tumor antigen-specific immune responses. This may be accomplished by inducing antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, by promoting antibody-targeted cross-presentation of tumor antigens or by triggering the idiotypic network. Future treatment modifications or combinations should be able to prolong, amplify and shape these immune responses to increase the clinical benefits of antibody therapy of human cancer.

Keywords: Monoclonal antibody, antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, dendritic cells, cross presentation, anti-idiotype

Introduction

Monoclonal antibodies have emerged as effective therapeutic agents for an increasing number of human malignancies. They have become one of the largest classes of new agents approved for the treatment of human cancer in the last decade (Table 1). An unconjugated antibody and two radioimmunoconjugates directed against CD20 exhibit significant anti-tumor activity 1–4, and have been shown to improve survival in both indolent as well as aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkins lymphoma. An anti-CD33 antibody-calicheamicin conjugate has been approved for use in refractory acute myeloid leukemia 5. Immunotoxins directed against CD22 demonstrate anti-tumor activity in hairy cell leukemia as well 6. An unconjugated anti-HER2/neu antibody is widely used alone and in combination with chemotherapy agents in breast cancer 7–9. Recently, this antibody has been shown to significantly improve relapse-free survival when used as a component of adjuvant therapy of HER2/neu expressing breast cancer 10. An unconjugated antibody directed against vascular endothelial growth factor improves survival in metastatic colorectal cancer 11. Unconjugated antibodies directed against the B-cell idiotype 12 and CD22 13 exhibit utility in the therapy of lymphomas, and one anti-CD20 antibody has become a widely used agent to treat lymphomas. An anti-CD52 antibody that fixes complement has been approved for use in chemotherapy-refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia 14. Antibodies directed against the extracellular domain of the epidermal growth factor receptor are clinically active in advanced colorectal cancer 15,16. In addition, antibodies that enhance host immune responses to self-tumor antigens by blocking the function of the CTLA-4 co-receptor on T-cells exhibit pre-clinical and clinical promise 17,18.

Table 1.

Therapeutic Monoclonal Antibodies Approved for Use in Oncology

| Generic Name (Trade Name) | Species of Origin | Isotype | Toxic Payload | Target | Indication | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconjugated Antibodies | ||||||

| Trastuzumab (Herceptin) | Humanized | IgG1 | - | HER2/neu | Breast Cancer | 7–10 |

| Rituximab (Rituxan) | Murine-human Chimeric | IgG1 | - | CD20 | Lymphoma | 1,2 |

| Cetuximab (Erbitux) | Murine- human Chimeric | IgG1 | - | EGF Receptor | Colorectal Cancer | 15 |

| Bevacizumab (Avastin) | Murine-human Chimeric | IgG1 | - | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor | Colorectal, Lung, Breast Cancers | 11 |

| Alemtuzumab (Campath-1H) | Humanized | IgG1 | - | CD52 | Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia | 14 |

| Immunoconjugates | ||||||

| Ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin) plus | Murine | IgG1 | 90 Yttrium | CD20 | Lymphoma | 3 |

| Rituximab | Human | IgG1 | ||||

|

131ITositumomab plus

Tositumomab (Bexxar) |

Murine | IgG2a | 131Iodine | CD20 | Lymphoma | 4 |

| Gemtuzumab (Myelotarg) | Human | IgG4 | Calicheamicin | CD33 | Acute myelogenous | 5 |

Multiple mechanisms have been proposed to explain the antitumor activity of unconjugated tumor antigen-specific monoclonal antibodies. However, in the past few years most attention has focused on the ability of such antibodies to manipulate critical signaling pathways that sustain the malignant phenotype and to trigger or enhance self-tumor antigen-specific immune responses. The capacity of antibodies to promote anti-tumor effects by modulating tumor antigen-specific immune responses has not received the attention it deserves. This review will examine the potential of monoclonal antibodies as immunotherapy vehicles. While many potential immunomodulatory mechanisms can be considered (e.g., complement activation, interference with inhibitory costimulation), we focus here on three key mechanisms: 1) mediating cellular cytotoxicity of tumor cells, 2) targeting Fc receptors on DCs to promote antigen presentation and induction of adaptive immune responses, and 3) eliciting tumor antigen-specific immune responses by triggering the idiotypic network.

Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC)

ADCC occurs when antibodies bind to antigens on tumor cells and the antibody Fc domains engage Fc receptors on the surface of immune effector cells 19. Several families of Fcγ receptors have been identified, and specific cell populations characteristically express defined Fcγ receptors 20. The engagement of activating Fcγ receptors by antibodies facilitates the recruitment of adaptor proteins and activation of immune effector cells 21. Even though many tumor antigen-specific antibodies have been shown to mediate in vitro ADCC, the relevance of this putative mechanism of action to clinical efficacy has been difficult to prove. Ravetch and his collaborators have evaluated the importance of Fc domain: Fcγ receptor interactions by examining the ability of clinically effective tumor antigen-specific monoclonal antibodies to control human tumor xenografts growing in either wild-type mice or in murine FcγRII/III knockout mice. Anti-tumor activity was diminished in the Fcγ receptor knockout mice, and was preserved when only the inhibitory Fcγ receptor isoform was deleted. These data support the concept that Fc domain: Fcγ receptor interactions underlie anti-tumor efficacy in mice, and suggest that such interactions with antibodies may be important for the anti-tumor activity of selected antibodies in the clinic 22. This mechanism may account for the substantially greater efficacy of rituximab in patients with lymphoma with “high responder” Fcγ receptor polymorphisms 23,24. Furthermore, these findings indicate that antibody Fc domain: Fc receptor interactions underlie at least some of the clinical benefit of rituximab, and imply the clinical relevance of ADCC, which depends upon such interactions. We discuss below the potential for manipulating antibody interactions with activating and inhibitory Fcγ receptors. The effector cell populations required for these effects have not been defined, but are presumed to include mononuclear phagocytes and/or natural killer cells. Manipulations of Fc domain structure can customize antibody clearance and the interaction of Fc domains with cellular Fcγ receptors 25–27. Considerable effort has been expended by the pharmaceutical industry to generate monoclonal antibodies that more effectively promote ADCC due to more efficient interactions with human Fcγ receptors.

Role of ADCC in anti-tumor efficacy of tumor antigen-specific antibodies

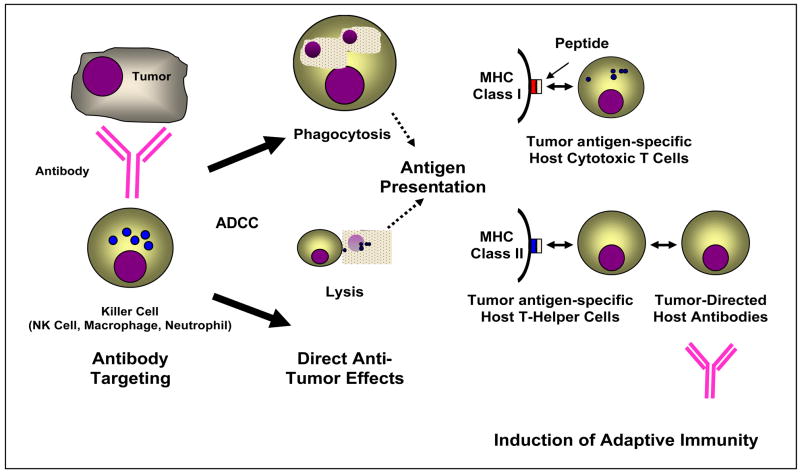

ADCC has long been viewed as a potentially independent mechanism of anti-tumor activity of tumor antigen-specific antibodies, but direct evidence supporting its relevance to the efficacy of antibody-based immunotherapy is not abundant, despite the compelling preclinical data of Ravetch and his collaborators discussed above. Therapy with an ADCC-inducing bispecific antibody can induce HER2/neu-specific antibodies 28. Accordingly, ADCC may be viewed as a mechanism to directly induce a variable degree of immediate tumor destruction that leads to antigen presentation and the induction of “cross-primed” tumor antigen-specific T-cell responses (Figure 1). As tumor cells by themselves are poor at initiating host-protective immunity, the generation of tumor antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses in vivo depends on the uptake by dendritic cells (DCs) of tumor antigens and their presentation to both CD4 helper and CD8 killer T cells. Typically, antigens derived from intracellular proteins are processed and presented on MHCI molecules to activate CD8+ killer T cells. However some antigen presenting cells such as DCs can process antigen from tumor cells and present the peptides on MHCI to CD8+ T cells, a process termed as “cross-presentation” 29. This model has potentially important implications for the development of unconjugated antibodies that mediate ADCC. Firstly, the model predicts that the in vivo induction of ADCC will lead to the induction of tumor antigen-specific T cell responses and host-derived antibody responses; such events could be viewed as the “footprints” of ADCC and could function as biomarkers of this antibody effect. Next, the induction of such immune responses may underlie or contribute to the clinical efficacy of unconjugated antibodies. It is plausible to assume that this vaccine-like property of antibody therapy can be exploited to selectively amplify or bias the resulting adaptive immune response by promoting the processes of antigen presentation, host antibody production, and expansion of tumor antigen-specific CTL. Such immune responses should be directed against not only the targeted tumor antigen, but also against other antigens that are processed and presented in the context of ADCC. ADCC effects also may enhance or be abetted by antibody-directed signaling perturbation and the induction of direct anti-tumor effects.

Figure 1. A proposed model for the induction of adaptive immune responses by ADCC.

An anti-tumor monoclonal antibody binds to an antigen on a tumor cell, and engages an Fc receptor on a killer cell. This induces antibody-promoted phagocytosis or direct cytolysis, resulting in antigen processing and presentation via MHC Class I or Class II molecules on antigen-presenting cells. This leads to the induction of host anti-tumor immunity manifested by either the production of tumor-directed host cytotoxic T-lymphocytes and/or antibodies.

Monoclonal antibodies as adjuvants: effects on adaptive immunity

Much of the early attention on the immune effects on tumor antigen-specific monoclonal antibodies was on their ability to recruit innate mechanisms such as ADCC by Fc receptor bearing killer cells and complement activation, as discussed above. However a growing body of evidence now suggests that monoclonal antibodies may also have the capacity to recruit adaptive tumor antigen-specific immunity 30,31.

DCs express Fcγ receptors and are efficient at uptake of opsonized antigens such as dying antibody coated tumor cells 31. Uptake of tumor cells by DCs can in principle lead to the induction of either immunity or tolerance, depending on the context of cell death, the nature of the phagocytic cargo and other signals from the tumor microenvironment 32. As several types of tumors do not express MHC II, uptake of tumor antigens by antigen presenting cells is also important for the induction of CD4+ T helper responses. Even in some settings when tumors express MHCII (as in the case of some hematologic tumors), defects in MHCII antigen processing correlate with outcome 33. Several studies with both human and murine DCs have now shown that the uptake of opsonized tumor antigens by DCs via Fcγ receptors leads to enhancement of cross presentation and efficient generation of both tumor antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses, both in vitro and in vivo 31, 34–44. The mechanism of Fcγ receptor mediated enhancement of cross presentation is not fully understood, but requires signaling via the activating Fcγ receptors 41, and may involve access of internalized antigen to the cytosol of the antigen presenting cell 42, or specialized signaling networks such as activation of interferon pathways 45. The ability of antibodies to enhance immunity may also enable improvements in DC therapies 46, and other cancer vaccines as well 47.

The preclinical data argue in favor of the possibility that tumor antigen-specific T cell responses may be generated in patients with malignant disease following antibody-based immunotherapy. Evidence to support this possibility has been provided by the recently described induction of MUC-1 specific T cell responses in patients treated with an anti-MUC-1 antibody 44. Similarly, enhanced immunity to Her2 was documented in breast cancer patients treated with trastuzumab and chemotherapy 48. However at present, the data about the induction of T cell immunity in antibody treated patients are too preliminary to permit any definitive conclusions or clinical correlations. In particular, studies to evaluate the nature of the tumor antigen-specific T cell response in the tumor microenvironment after antibody therapy have not yet been described.

The ability of monoclonal antibody therapy to recruit tumor antigen-specific T cells may be particularly important for the durability of anti-tumor responses. Immunologic memory associated with T cells may also help improve responses with repeated administration of the antibody 48,49. It has been suggested that repeated administration of rituximab in patients with relapsed lymphoma may lead to more durable responses than those achieved after initial administration 50. While this may be explained by greater B cell depletion with repeat mAb administration in the setting of minimal residual disease, an alternate possibility is the induction of adaptive immunity and immunologic memory to tumor cells. The generation of T cell responses against antigens other than those targeted by the antibody may also help prevent the emergence of therapeutic resistance due to antigen loss variants of tumor cells 51.

Effects of the balance of activating and inhibitory Fcγ receptors on the outcome of antigen presentation

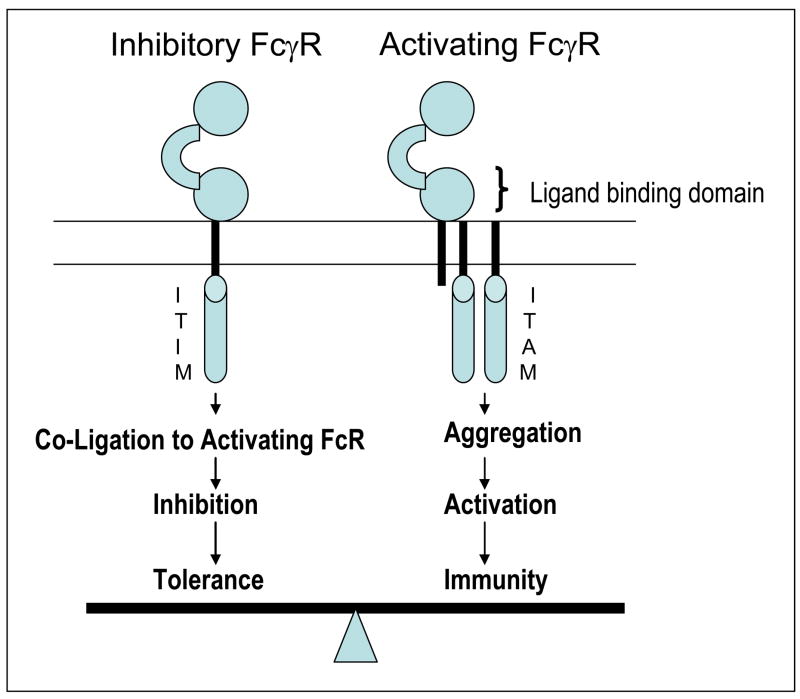

As mentioned above, Fcγ receptors of the activating type allow DCs to take up and process antigens and to present antigen derived peptides on MHC class I and class II to CD8+ and CD4+ T lymphocytes, respectively. However, in addition to antigen uptake and processing, the immunologic outcome depends on the state of DC differentiation or maturation. During the steady state, DCs reside in an immature form, and can promote immune tolerance 52. Exposure to stimuli such as pathogens activates or matures DCs and initiates immunity. The type of immunity depends upon the particular maturation stimulus that the DC encounters. Fcγ receptors not only mediate antigen uptake, but they also influence DC maturation, and the balance between activating versus inhibitory Fcγ receptors is critical to this process (Figure 2) 53. Conventional DCs express both activating FcγRIIa and FcγRIIIa receptors as well as inhibitory FcγRIIb receptors 54 while the subset of plasmacytoid DCs lacks inhibitory FcγRIIB, expressing only the activating isoform 55. Thus binding of immune complexes by plasmacytoid DCs in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus reliably activates these cells to produce large amounts of type I interferons, a hallmark of immune activation 56. The role of plasmacytoid DCs in immune responses following administration of tumor antigen-specific monoclonal antibodies remains to be defined. Initial studies with murine DCs demonstrated that signaling via activating Fc receptors leads to DC maturation 57 and that DCs from mice lacking the inhibitory Fcγ receptors have enhanced capacity for antigen presentation in vitro and in vivo 58. In addition to the effect on the generation of T cell responses, uptake of antigen via inhibitory Fcγ receptors on DCs can also lead to the generation of B cell responses 59.

Figure 2. Fc receptors and immune balance.

Signaling via Fcγ receptors (FcγR) is regulated by a balance of activating versus inhibitory FcγR, which carry immune tyrosine activating motif (ITAM) versus immune tyrosine inhibitory motifs (ITIM). Fc domains of monoclonal antibodies can generally engage both forms of receptors. The balance of net engagement of activating versus inhibitory receptors depends on both host and antibody related factors and determine antibody mediated activation of immunity.

The recent development of monoclonal antibodies that specifically block the inhibitory FcγRIIB receptor in humans has facilitated the selective manipulation of the balance of Fcγ receptors in human DCs 60,61. The blockade of the inhibitory Fc receptor on human DCs leads to enhanced dendritic cell maturation 60,61 and, more importantly, augments their ability to generate tumor antigen-specific T cells in vitro 61. Therefore monoclonal antibodies that preferentially target activating Fcγ receptors may serve a dual role, not only by providing an efficient pathway for the uptake of tumor antigens, but also by delivering a potent maturation stimulus to the antigen presenting DC. Together, these studies suggest that the balance of engagement of activating versus inhibitory Fcγ receptors on human DCs by monoclonal antibodies may be a critical determinant of their ability to boost adaptive immunity.

The recruitment of activating versus inhibitory Fcγ receptors by therapeutic monoclonal antibodies in vivo also depends on host-related features (e.g. Fcγ receptor polymorphisms 24 and cytokine mediated regulation of Fcγ receptors), as well as on the properties of the antibody itself (such as its isotype and glycosylation or sialylation status) 62. Translation of this biology into improved antibody engineering (e.g. variants with enhanced binding to FcγRIIa or FcγRIIIa), use of bispecific antibodies selectively targeting tumor antigen and activating Fcγ receptors 63,64 or combining current monoclonal antibodies with agents that selectively manipulate signaling via activating and inhibitory Fcγ receptors may lead to improved therapeutic outcome with the next generation of monoclonal antibody trials in patients with malignant disease.

Anti-idiotypic antibodies as tumor antigen mimics

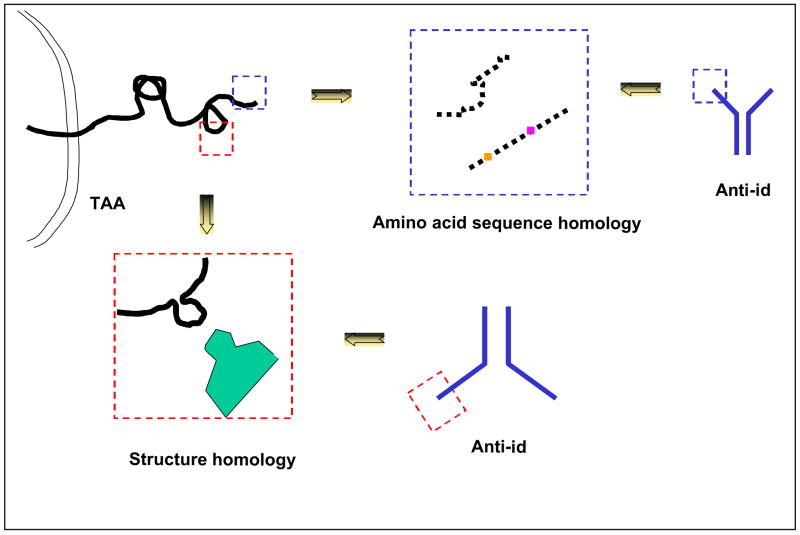

The high diversity of the amino acid sequence of heavy and light chain variable regions of an antibody is reflected in the expression of conformational and structural antigenic determinants which are unique or expressed on a few antibody populations. These determinants, which are named idiotopes because of their restricted distribution on antibody populations, are recognized as foreign by the host immune system and therefore can trigger an immune response. Some idiotopes are located in the area of the antigen binding site of the antibody which interacts with the corresponding antigen. As a result they are complementary to the corresponding antigenic determinant. Others, although located in the combining site of the antibody, are not directly involved in its binding of the corresponding antigen and therefore have no complementarity with the corresponding epitope. According to Jerne’s idiotypic network theory 65 the induction of an antibody triggers the idiotypic cascade in a host (Figure 3). As a result the elicited antibody induces antibodies to its idiotopes which are referred to as anti-idiotypic antibodies. Some of them may recognize idiotope(s) complementary to the antigenic determinant which has triggered the idiotypic network and therefore react with the same area(s) of the antigen binding site of the antibody which binds to the nominal antigen. The similarity in reactivity between the nominal antigen and some anti-idiotypic antibodies reflects homology between the involved antigenic determinant and portion(s) of the variable regions of the anti-idiotypic antibody. This homology, which is conformational in most of the cases and structural only in a few 66,67,68, accounts for the ability of some anti-idiotypic antibodies to act as surrogate antigens and to elicit an immune response to the nominal antigen (Figure 4). Anti-idiotypic antibodies which mimic tumor antigens represent attractive vaccines, since they can overcome patients’ unresponsivness to tumor antigens, most of which have low or no immunogenicity because of their self-nature. Furthermore, taking advantage of hybridoma methodology, anti-idiotypic antibodies with well defined characteristics can be produced in large amounts in a reproducible fashion, thus facilitating the standardization of vaccines for clinical use.

Figure 3. Triggering of the idiotypic network by immunization with a tumor antigen.

The antibody, referred to as Ab1, elicited by a tumor antigen induces anti-idiotypic antibodies to the idiotopes expressed on its variable region. Some anti-idiotypic antibodies, referred to as Ab2β, react with the area of the Ab1 variable region, which binds to the nominal antigen. These anti-idiotypic antibodies bear the internal image of the nominal antigen and therefore can induce tumor antigen binding antibodies, referred to as Ab3. Other anti-idiotypic antibodies, referred to as Ab2γ, react with areas of the Ab1 variable region, which do not bind to the nominal antigen. They can interfere with the binding of Ab1 to the nominal antigen, and induce anti-anti-idiotypic antibodies which do not bind to the nominal antigen. Other anti-idiotypic antibodies, referred to as Ab2α, react with areas of the Ab1 variable region outside its antigen combining site. They do not interfere with the binding of Ab1 to the nominal antigen, and induce anti-anti-idiotypic antibodies which do not bind to the nominal antigen.

Figure 4. Molecular basis of tumor antigen mimicry by an anti-idiotypic antibody.

The mimicry of a tumor antigen by an anti-idiotypic antibody may reflect the homology of an amino acid sequence stretch of a tumor antigen with a stretch of the anti-idiotypic antibody variable region amino acid sequence or conformational similarity between a tumor antigen determinant and an anti-idiotypic antibody idiotope.

Triggering of the idiotypic cascade by antibody-based immunotherapy

As discussed above, tumor antigen-specific antibodies can have antitumor effects by activating immunological mechanisms and/or by interfering with the function of molecules which are crucial for the survival and/or proliferation of tumor cells. Emerging evidence is compatible with the possibility that tumor antigen-specific antibodies also may contribute to anti-tumor effects by triggering the idiotypic cascade and inducing a tumor antigen-specific immune response. A variable percentage of patients with neuroblastoma, colorectal cancer, pancreas carcinoma, ovarian carcinoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma and melanoma has been found to develop anti-idiotypic antibodies following the administration of tumor antigen-specific antibodies for diagnostic and/or therapeutic purposes 71–81. Although the induced anti-idiotypic antibodies may shorten the half life of the injected tumor antigen-specific antibody and interfere with its targeting of tumor cells, the triggering of the idiotypic cascade has been reported to be associated with a favorable clinical response to antibody-based therapy in patients with neuroblastoma, colorectal carcinoma, ovarian carcinoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma 71,72,77,79,80,81. This association may reflect the development of cellular and/or humoral immunity specific for the tumor antigen targeted by the administered antibody, since the induced anti-idiotypic antibodies mimic the targeted tumor antigen. In this regard, anti-idiotypic antibodies which can induce a cellular immune response to the CD55 glycoprotein in patients with colorectal carcinoma 82 and a humoral immune response to GD2 ganglioside and to CEA 79,82 in xenogeneic hosts have been isolated from patients with melanoma, or pancreas carcinoma treated with antibody-based immunotherapy. Furthermore GD2 ganglioside-specific antibodies have been induced in patients with neuroblastoma treated with GD2 ganglioside antibodies 87 and colorectal carcinoma antigen CO17-1A-specific cellular and/or humoral immunity has been detected in patients with colorectal carcinoma treated with the monoclonal antibody CO17-1A 78, 79 Whether these responses can mediate tumor regressions needs further evaluation and optimization. Furthermore it remains to be determined why the idiotypic cascade is not triggered in a variable proportion of the patients treated with tumor antigen-specific monoclonal antibodies. Does this reflect immunological dysfunction caused by the underlying malignant disease?

Anti-idiotype antibodies as vaccines in malignant diseases

Anti-idiotype antibodies which mimic tumor antigens have been utilized as immunogens in patients with malignant diseases to overcome the lack or low immunogenicity of tumor antigens, which are for the most part self-antigens expressed at higher levels by malignant cells than by their normal counterparts. The induction of self-tumor antigen-specific immune responses by anti-idiotype antibodies reflects their ability to stimulate T and B cell clones which have not been deleted during the establishment of self-identity because their affinity for self-tumor antigens is below the threshold required for deletion. As a result the tumor antigen-specific immune responses elicited by anti-idiotype antibodies like that induced by other types of mimics are in general weak.

Anti-idiotype antibodies which mimic both protein and ganglioside tumor antigens have been utilized to implement active specific immunotherapy in patients with melanoma, breast, colorectal or ovarian carcinoma 78,85,86,87,88,89,90. With few exceptions 78,90 the anti-idiotype antibodies used have been mouse monoclonal antibodies. Although they have elicited high titer anti-mouse immunoglobulin antibodies, repeated administrations of mouse anti-idiotype antibodies have not caused side effects. Most, although not all the anti-idiotype antibodies used have elicited a tumor antigen-specific humoral immune response in a variable percentage of the immunized patients. Although there is variability in the immune response among the immunized patients as well as among the immunizing anti-idiotype antibodies, the level of the elicited tumor antigen-specific antibodies is in general low. This finding is likely to reflect the stimulation of B cell clones with low reactivity with self-tumor antigen because the immunizing anti-idiotype antibody resembles, but is not identical to the nominal tumor antigen. Furthermore, it remains to be determined whether the differential immunogenicity of the anti-idiotype antibodies reflects the different extent of tumor antigen mimicry, the different immunization schedule and/or the characteristics of the immunized patient population.

Anti-idiotypic antibodies which mimic CD55 and high molecular weight-melanoma associated antigen have been found to elicit HLA class I antigen restricted, tumor antigen-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes 91,92. This finding, which challenges the general belief that anti-idiotypic antibodies cannot elicit a tumor antigen-specific cytotoxic T-cell response, appears to reflect the presence in the anti-idiotypic antibody variable region of amino acid sequence stretches with HLA class I anchor motifs and with structural or conformational homology with the amino acid sequence of the nominal tumor antigen 93.

The tumor antigen-specific immune response elicited by anti-idiotype antibodies has been found to be associated with regression of metastases and/or with survival prolongation in patients with melanoma or colorectal or ovarian carcinoma 85, 89, 90. The association between clinical benefit and induction of tumor antigen-specific immunity, which is not absolute, as observed in other types of active specific immunotherapy, requires further studies.

Future Directions

The induction of adaptive tumor antigen-specific immune responses continues to hold enormous promise for cancer prevention and therapy. Monoclonal antibodies provide underappreciated opportunities for immunization against cancer. This may be accomplished by tumor-directed antibodies, by anti-idiotype antibodies or by combinations that include these approaches in concert with other immune manipulations strategies. Monoclonal antibody therapy-promoted ADCC can directly cause tumor destruction, and subsequent antigen uptake, processing and presentation by DCs and related professional antigen presenting cells, leading to adaptive T-cell-mediated immune responses. Monoclonal antibodies can be engineered to mediate improved ADCC, which should enhance antigen presentation and T cell activation. This can be accomplished by increasing antibody affinity for tumor antigen targets, or by manipulating antibody Fcγ domains to increase their affinity for Fcγ receptor(s). As discussed above, it may prove possible to further refine such antibody engineering to selectively engage activating, as opposed to inhibitory Fcγ receptors. Alternatively, it may be advantageous to generate antibodies that selectively block the interactions of tumor antigen-specific antibodies with inhibitory Fcγ receptors. Antibody structures can be further modified to contain immunostimulatory motifs that selectively induce, shape and amplify antigen processing, presentation and costimulation to favor the induction of clinically effective host anti-tumor immune responses. In lieu of direct modification of antibody structures, tumor antigen-specific antibodies might be combined with other agents that promote antigen presentation (e.g., toll receptor agonists), costimulation (e.g., anti-CTLA-4 antibody), or T-cell activation or expansion (e.g., interleukin-2). Antibody therapy may also help enhance the efficacy of other immune therapies such as DC vaccines 46. It should not be forgotten that several clinically useful antibodies that mediate ADCC are routinely combined with chemotherapy agents; further studies are required to determine if chemotherapy-based tumor destruction cooperates with monoclonal antibody therapy to promote adaptive, tumor antigen-specific immunity.

The association between tumor antigen-specific immune responses elicited by anti-idiotypic antibodies and clinical responses emphasizes the need for randomized clinical trials to obtain clinical proof-of-concept about the validity of this immunization strategy. Furthermore approaches should be developed to enhance the ability of anti-idiotype antibodies to elicit a strong tumor antigen-specific immune response with the expectation that this will improve its anti-tumor effects. These studies will benefit from the characterization of the structural basis of tumor antigen mimicry by the corresponding anti-idiotypic antibodies and of the relationship between the extent of antigen mimicry and immunogenicity of a mimic. This information, in turn, will facilitate the replacement of anti-idiotypic antibodies with peptide mimics which are more amenable to manipulations to enhance their immunogenicity.

Acknowledgments

CA51008, CA50633, CA121033, (LMW); CA106802, CA109465, Damon Runyon Cancer Research Fund, Dana Foundation (MVD); and CA 105500 (SF).

References

- 1.McLaughlin P, Grillo-Lopez AJ, Link BK, et al. Rituximab chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy for relapsed indolent lymphoma: half of patients respond to a four-dose treatment program. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2825–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.8.2825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaminski MS, Estes J, Zasadny KR, et al. Radioimmunotherapy with iodine (131)I tositumomab for relapsed or refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: updated results and long-term follow-up of the University of Michigan experience. Blood. 2000;96:1259–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coiffier B. Rituximab in combination with CHOP improves survival in elderly patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Semin Oncol. 2002;29(2 Suppl 6):18–22. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.32749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Witzig TE, Gordon LI, Cabanillas F, et al. Randomized controlled trial of yttrium-90-labeled ibritumomab tiuxetan radioimmunotherapy versus rituximab immunotherapy for patients with relapsed or refractory low-grade, follicular, or transformed B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;20:2453–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sievers EL, Appelbaum FR, Spielberger RT, et al. Selective ablation of acute myeloid leukemia using antibody-targeted chemotherapy: a phase I study of an anti-CD33 calicheamicin immunoconjugate. Blood. 1999;93:3678–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kreitman RJ, Wilson WH, Bergeron K, et al. Efficacy of the anti-CD22 recombinant immunotoxin BL22 in chemotherapy-resistant hairy-cell leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:241–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107263450402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cobleigh MA, Vogel Cl, Tripathy D, et al. Multinational study of the efficacy and safety of humanized anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody in women who have HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer that has progressed after chemotherapy for metastatic disease. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2639–48. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.9.2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:783–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vogel CL, Cobleigh MA, Tripathy D, et al. Efficacy and safety of trastuzumab as a single agent in first-line treatment of HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:719–26. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.3.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J, et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1673–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller RA, Maloney DG, Warnke R, et al. Treatment of B-cell lymphoma with monoclonal anti-idiotype antibody. N Eng J Med. 1982;306:517–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198203043060906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leonard JP, Link BK. Immunotherapy of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with hLL2 (epratuzumab, an anti-CD22 monoclonal antibody) and Hu1D10 (apolizumab) Semin Oncol. 2002;29(1 Suppl 2):81–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lundin J, Kimby E, Bjorkholm M, et al. Phase II trial of subcutaneous anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody alemtuzumab (Campath-1H) as first-line treatment for patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) Blood. 2002;100:768–73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Figlin RA, Belldegrun AS, Crawford J, Lohner M, Roskos L, Yang X-D, Foon K, Schwab G, Weiner L. ABX-EGF, a fully human anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) monoclonal antibody (mAb) in patients with advanced cancer: phase 1 clinical results. Proceedings ASC0. 2002;21:35. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cunningham D, Humblet Y, Siena S, et al. Cetuximab monotherapy and cetuximab plus irinotecan in irinotecan-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:337–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.0egen JG, Kuhns MS, Allison JP. CTLA-4: new insights into its biological function and use in tumor immunotherapy. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:611–18. doi: 10.1038/ni0702-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phan GQ, Yang JC, Sherry RM, et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity induced by cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 blockade in patients with metastatic melanoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8372–77. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533209100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steplewski Z, Lubeck MD, Koprowski H. Human macrophages armed with murine immunoglobulin G2a antibodies to tumors destroy human cancer cells. Science. 1983;221:865–67. doi: 10.1126/science.6879183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heijnen IA, van de Winkel JG. Human IgG Fc receptors. Int Rev Immunol. 1997;16:29–55. doi: 10.3109/08830189709045702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sulica A, Morel P, Metes D, et al. Ig-binding receptors on human NK cells as effecter and regulatory surface molecules. Int Rev Immunol. 2001;20:371–414. doi: 10.3109/08830180109054414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clynes RA, Towers TL, Presta LG, et al. Inhibitory Fc receptors modulate in vivo cytoxicity against tumor targets. Nat Med. 2000;6:443–46. doi: 10.1038/74704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cartron G, Dacheux L, Salles G, et al. Therapeutic activity of humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and polymorphism in IgG Fc receptor FcgammaRIIIa gene. Blood. 2002;99:754–58. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weng WK, Levy R. Two immunoglobulin G fragment C receptor polymorphisms independently predict response to rituximab in patients with follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3940–47. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Umana P, Jean-Mairet J, Moudry R, et al. Engineered glycoforms of an antineuroblastoma IgG1 with optimized antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxic activity. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:176–80. doi: 10.1038/6179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghetie V, Ward ES. Multiple roles for the major histocompatibility complex class I-related receptor FcRn. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:739–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shields RL, Namenuk AK, Hong K, et al. High resolution mapping of the binding site on human IgG1 for Fc gamma RI, Fc gamma RII, Fc gamma RIII, and FcRn and design of IgG1 variants with improved binding to the Fc gamma R. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6591–604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009483200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark JI, Alpaugh RK, von Mehren M, et al. Induction of multiple anti-c-erbB-2 specificities accompanies a classical idiotypic cascade following 2B1 bispecific monoclonal antibody treatment. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1997;44:265–72. doi: 10.1007/s002620050382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heath WR, Carbone FR. Cross-presentation, dendritic cells, tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:47–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amigorena S. Fc gamma receptors and cross-presentation in dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:F1–3. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dhodapkar KM, Dhodapkar MV. Recruiting dendritic cells to improve antibody therapy of cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:6243–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502547102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dhodapkar MV, Dhodapkar KM, Palucka AK. Interactions of tumor cells with dendritic cells: balancing immunity and tolerance. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:39–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chamuleau ME, Souwer Y, Van Ham SM, et al. Class II-associated invariant chain peptide expression on myeloid leukemic blasts predicts poor clinical outcome. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5546–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.den Haan JM, Bevan MJ. Constitutive versus activation dependent cross presentation of immune complexes by CD8+ and CD8− dendritic cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2002;196:817–27. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dhodapkar KM, Krasovsky J, Williamson B, et al. Antitumor monoclonal antibodies enhance cross-presentation of cellular antigens and the generation of myeloma-specific killer T cells by dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:125–33. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagata Y, Ono S, Matsuo M, et al. Differential presentation of a soluble exogenous tumor antigen, NY-ESO-1, by distinct human dendritic cell populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10629–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112331099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rafiq K, Bergtold A, Clynes R. Immune complex-mediated antigen presentation induces tumor immunity. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:71–79. doi: 10.1172/JCI15640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schuurhuis DH, Ioan-Facsinay A, Nagelkerken B, et al. Antigen-antibody immune complexes empower dendritic cells to efficiently prime specific CD8+ CTL responses in vivo. J Immunol. 2002;168:2240–46. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.5.2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Selenko N, Majdic O, Jager U, et al. Cross-priming of cytotoxic T cells promoted by apoptosis-inducing tumor cell reactive antibodies? J Clin Immunol. 2002;22:124–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1015463811683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akiyama K, Ebihara S, Yada A, et al. Targeting apoptotic tumor cells to FcR provides efficient and versatile vaccination against tumors by dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:1641–48. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Groh V, Li YQ, Cioca D, et al. Efficient cross-priming of tumor antigen specific T cells by dendritic cells sensitized with diverse anti-MICA opsonized tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:6461–66. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501953102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sedlik C, Orbach D, Veron P, et al. A critical role for Syk protein tyrosine kinase in Fc receptor-mediated antigen presentation and induction of dendritic cell maturation. J Immunol. 2003;170:846–52. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.2.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rodriguez A, Regnault A, Kleijmeer M, et al. Selective transport of internalized antigens to the cytosol for MHC class I presentation in dendritic cells. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:362–68. doi: 10.1038/14058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Banerjee D, Matthews P, Matayeva, et al. Enhanced T cell responses to glioma cells coated with anti-EGF receptor antibody and targeted to activating FcgRs on human dendritic cells. J Immunotherapy. 2008 doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31815a5892. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Bono JS, Rha SY, Stephenson J, et al. Phase I trial of a murine antibody to MUC1 in patients with metastatic cancer: evidence for the activation of humoral and cellular antitumor immunity. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1825–33. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dhodapkar KM, Banerjee D, Connolly, et al. Selective blockade of the inhibitory Fc{gamma} receptor (Fc{gamma}RIIB) in human dendritic cells and monocytes induces a type I interferon response program. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1359–69. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Franki SN, Steward KK, Betting, et al. Dendritic cells loaded with apoptotic antibody-coated tumor cells provide protective immunity against B-cell lymphoma in vivo. Blood. 2008;111:1504–11. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-080507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jinushi M, Hodi FS, Dranoff G. Therapy-induced antibodies to MHC class I chain-related protein A antagonize immune suppression and stimulate antitumor cytotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9190–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603503103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taylor C, Hershman D, Shah N, et al. Augmented HER-2 specific immunity during treatment with trastuzumab and chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5133–43. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weng WK. Immune mediated antitumor effects with antibody therapy. ASCO Annual Meeting Educational Book. 2005:200–204. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davis TA, Grillo-Lopez AJ, White CA, et al. Rituximab anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: safety and efficacy of re-treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3135–43. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.17.3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davis TA, Czerwinski DK, Levy R. Therapy of B-cell lymphoma with anti-CD20 antibodies can result in the loss of CD20 antigen expression. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:611–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mellman I, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells: specialized and regulated antigen processing machines. Cell. 2001;106:255–58. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00449-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ravetch JV, Bolland S. IgG Fc receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:275–90. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Amigorena S, Bonnerot C. Fc receptors for IgG and antigen presentation on MHC class I and class II molecules. Semin Immunol. 1999;11:385–90. doi: 10.1006/smim.1999.0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bave U, Magnusson M, Eloranta ML, et al. Fc gamma RIIa is expressed on natural IFN-alpha-producing cells (plasmacytoid dendritic cells) and is required for the IFN-alpha production induced by apoptotic cells combined with lupus IgG. J Immunol. 2003;171:3296–302. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.3296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Means TK, Latz E, Hayashi F, et al. Human lupus autoantibody-DNA complexes activate dendritic cells through cooperation of CD32 and TLR9. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:407–17. doi: 10.1172/JCI23025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Regnault A, Lankar D, Lacabanne V, et al. Fcgamma receptor-mediated induction of dendritic cell maturation and major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted antigen presentation after immune complex internalization. J Exp Med. 1999;189:371–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kalergis AM, Ravetch JV. Inducing tumor immunity through the selective engagement of activating Fc receptors on dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1653–59. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bergtold A, Desai DD, Gavhane A, et al. Cell surface recycling of internalized antigen permits dendritic cell priming of B cells. Immunity. 2005;23:503–14. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boruchov AM, Heller G, Veri MC, et al. Activating and inhibitory IgG Fc receptors on human dendritic cells mediate opposing functions. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2914–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI24772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kaneko Y, Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Anti-inflammatory activity of immunoglobulin G resulting from Fc sialylation. Science. 2006;313:670–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1129594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dhodapkar KM, Kaufman JL, Ehlers M, et al. Selective blockade of inhibitory Fc{gamma} receptor enables human dendritic cell maturation with IL-12p70 production and immunity to antibody-coated tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2910–15. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500014102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Divergent immunoglobulin g subclass activity through selective Fc receptor binding. Science. 2005;310:1510–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1118948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shahied LS, Tang Y, Alpaugh RK. Bispecific minibodies targeting HER2/neu and CD16 exhibit improved tumor lysis when placed in a divalent tumor antigen binding format. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53907–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407888200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fischer N, Leger O. Bispecific antibodies: molecules that enable novel therapeutic strategies. Pathobiology. 2007;74:3–14. doi: 10.1159/000101046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jerne NK. Towards a network theory of the immune system. Ann Immunol (Paris) 1974;125C:373–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Spendlove L, Li L, Potter V, et al. A therapeutic human anti-idiotypic antibody mimics CD55 in three distinct regions. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:2944–53. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200010)30:10<2944::AID-IMMU2944>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chatterjee SK, Tripathi PK, Chakraborty M, et al. Molecular mimicry ofcarcinoembryonic antigen by peptides derived from the structure of an anti-idiotype antibody. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1217–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chang CC, Hernandez-Guzman FG, Luo W, Wang X, Ferrone S, Ghosh D. Structural basis of antigen mimicry in a clinically relevant melanoma antigen system. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:41546–552. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507562200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Koprowski H, Herlyn D, Lubeck M, et al. Human anti-idiotype antibodies in cancer patients: Is the modulation of the immune response beneficial for the patient? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:216–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.1.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Steinitz M, Tamir S, Frodin JE, et al. Human monoclonal anti-idiotypic antibodies. I. Establishment of immortalized cell lines from a tumor patient treated with mouse monoclonal antibodies. J Immunol. 1988;141:3516–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Austin EB, Robins RA, Durrant LG, et al. Human monoclonal anti-idiotypic antibody to the tumour-associated antibody 791T/36. Immunology. 1989;67:525–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wettendorff M, Iliopoulos D, Tempero M, et al. Idiotypic cascades in cancer patients treated with monoclonal antibody CO17-1A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:3787–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Losman MJ, Hansen HJ, Sharkey RM, et al. Human response against NP-4, a mouse antibody to carcinoembryonic antigen: human anti-idiotype antibodies mimic an epitope on the tumor antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:3421–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Saleh MN, Stapleton JD, Khazaeli MB, LoBuglio AF. Generation of a human anti-idiotypic antibody that mimics the GD2 antigen. J Immunol. 1993;151:3390–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cheung NK, Cheung IY, Canete A, et al. Antibody response to murine anti-GD2 monoclonal antibodies: correlation with patient survival. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2228–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fagerberg J, Steinitz M, Wigzell H, et al. Human anti- idiotypic antibodies induced a humoral and cellular immune response against a colorectal carcinoma-associated antigen in patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:4773–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schultes BC, Baum RP, Niesen A, et al. Anti-idiotypeinduction therapy: anti-CA125 antibodies (Ab3) mediated tumor killing in patients treated with Ovarex mAb B43.13 (Ab1) Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1998;46:201–12. doi: 10.1007/s002620050479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cheung NK, Guo HF, Heller G, et al. Induction of Ab3 and Ab3′ antibody was associated with long-term survival after anti-G(D2) antibody therapy of stage 4 neuroblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2653–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bradt BM, DeNardo SJ, Mirick GR, et al. Documentation of idiotypic cascade after Lym-1 radioimmunotherapy in a patient with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: basis for extended survival? Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:4007S–12S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Robins RA, Denton GW, Hardcastle JD, et al. Antitumor immune response and interleukin 2 production induced in colorectal cancer patients by immunization with human monoclonal anti-idiotypic antibody. Cancer Res. 1991;51:5425–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fagerberg J, Frodin JE, Wigzell H, et al. Induction of an immune network cascade in cancer patients treated with monoclonal antibodies (ab1). I May induction of ab1-reactive T cells and anti-anti-idiotypic antibodies (ab3) lead to tumor regression after mAb therapy? Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1993;37:264–70. doi: 10.1007/BF01518521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fagerberg J, Hjelm AL, Ragnhammar P, et al. Tumor regression in monoclonal antibody-treated patients correlates with the presence of anti-idiotype-reactive T lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1824–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mittelman A, Chen ZJ, Yang H, et al. Human high molecular weight melanoma-associated antigen (HMW-MAA) mimicry by mouse anti-idiotypic monoclonal antibody MK2-23: induction of humoral anti-HMW-MAA immunity and prolongation of survival in patients with stage IV melanoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:466–470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.2.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yao TJ, Meyers M, Livingston PO, et al. Immunization of melanoma patients with BEC2-keyhole limpet hemocyanin plus BCG intradermally followed by intravenous booster immunizations with BEC2 to induce anti-GD3 ganglioside antibodies. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:77–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Foon KA, Chakraborty M, John WJ, et al. Immune response to the carcinoembryonic antigen in patients treated with an anti-idiotype antibody vaccine. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:334–342. doi: 10.1172/JCI118039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Foon KA, Sen G, Hutchins L, et al. Antibody responses in melanoma patients immunized with an anti-idiotype antibody mimicking disialoganglioside GD2. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:1117–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wagner U, Kohler S, Reinartz S, et al. Immunological consolidation of ovarian carcinoma recurrences with monoclonal anti-idiotype antibody ACA125: immune responses and survival in palliative treatment. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1154–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Herlyn D, Birebent B, Akis N, et al. Colon cancer antigen and anti-idiotype vaccines. Cancer Chemother Biol Response Modif. 2003;21:287–98. doi: 10.1016/s0921-4410(03)21014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Durrant LG, Parsons T, Moss R, et al. Human anti-idiotypic antibodies can be good immunogens as they target Fc receptors on antigen-presenting cells allowing efficient stimulation of both helper and cytotoxic T-cell responses. Int J Cancer. 2001;92:414–20. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Murray JL, Gillogly M, Kawano K, et al. Fine specificity of high molecular weight-melanoma-associated antigen specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes elicited by anti-idiotypic monoclonal antibodies in patients with melanoma. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5481–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kawano K, Ferrone S, Ioannides C. Functional Idiotopes: Tumor antigen directed expression of CD8+ T-cell epitopes nested in unique NH2-terminal VH sequence of antiidiotypic antibodies? Cancer Res. 2005;65:6002–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]