Abstract

P-bodies are cytoplasmic foci that are sites of mRNA degradation and translational repression. It is not known what causes the accumulation of RNA degradation factors in P-bodies, although RNA is required. The yeast Lsm1-7p complex is recruited to P-bodies under certain stress conditions. It is required for efficient decapping and degradation of mRNAs, but not for the assembly of P-bodies. Here we show that the Lsm4p subunit and its asparagine-rich carboxy-terminus are prone to aggregation and that this tendency to aggregate promotes efficient accumulation of Lsm1-7p in P-bodies. The presence of Q/N-rich regions in other P-body components suggests a more general role for aggregation-prone residues in P-body localization and assembly. This is supported by reduced P-body accumulation of Ccr4p, Pop2p and Dhh1p after deletion of these domains, and by the observed aggregation of the Q/N-rich region from Ccr4p.

Keywords: P-body localization, protein aggregation, Q/N-rich domains, stress

INTRODUCTION

Cytoplasmic mRNA processing bodies, or P-bodies, contain a variety of protein factors, some of which are involved directly in decapping (Dcp1p, Dcp2p), some in translational repression and/or activation of decapping (Pat1p, Dhh1p/RCK/p54, Edc1p, Edc2p, Edc3p, Scd6p/RAP55) and others are involved in deadenylation (Ccr4p, Pop2p, Not1-5p, Pan2p, Pan3p) or 5′ to 3′ degradation (Xrn1p). In addition, factors involved in non-sense mediate decay and RNA interference (e.g. Ago1) are present in these foci (reviewed by Parker and Sheth, 2007). P-bodies in higher eukaryotes have also been called GW bodies after GW182 (Eystathioy et al., 2003), a component that is required for their integrity (Liu et al., 2005) and which has a function in miRNA-mediated silencing (Jakymiw et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2005; Rehwinkel et al., 2005). In budding yeast, the cytoplasmic Lsm1-7p complex, which is involved in mRNA decapping and subsequent 5′ to 3′ decay (Bouveret et al., 2000; Tharun et al., 2000), localizes to P-bodies under certain stress conditions (Sheth and Parker, 2003; Teixeira et al., 2005). In higher eukaryotes, Lsm1-7p is present in similar foci, even under normal growth conditions (Ingelfinger et al., 2002; Eystathioy et al., 2003; Cougot et al., 2004). Lsm1-7p is thought to act as a chaperone, remodelling transcript-containing ribonucleoprotein particles (RNPs) at a step following deadenylation, thus promoting decapping (Tharun et al., 2000).

In yeast no single protein component is responsible for P-body assembly but there is a level of interdependence in the recruitment of some of the components to these foci (Teixeira and Parker, 2007). In contrast, in human cells depletion of many components, with the notable exception of Xrn1 and Dcp2, affects localization of the others (reviewed by Jakymiw et al., 2007), suggesting that most components involved in early, but not late stages of mRNA decay are essential for P-body assembly. It is not known what makes any of these factors concentrate in cytoplasmic foci, although in yeast this seems to require RNA (Teixeira et al., 2005). More recently, various proteins in budding yeast have been implicated directly in P-body assembly, and the understanding of their physical and functional interactions is gathering pace. This includes Edc3p, Lsm4p (Decker et al., 2007), Pat1p (Pilkington and Parker, 2008), and Ded1p (Beckham et al., 2008).

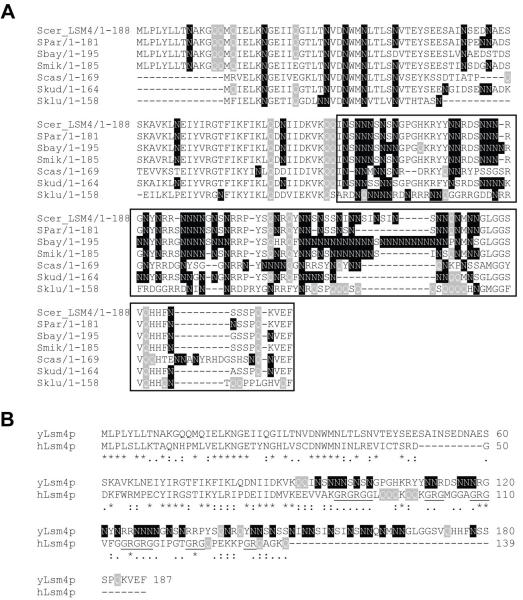

LSM4 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae encodes an essential protein of 187 amino acids. It is one of the seven subunits of the Lsm1-7p and Lsm2-8p complexes, the latter of which is needed for efficient pre-mRNA splicing through its role in U6 snRNA stability (Achsel et al., 1999; Mayes et al., 1999; Pannone et al., 1998; Salgado-Garrido et al., 1999) and localization (Spiller et al., 2007a) as well as U4/U6 di-snRNP formation (Verdone et al., 2004). The amino-terminal 92 amino acids of Lsm4p include the Sm-domain, which is involved in protein-protein and protein-RNA interactions within the Lsm complexes (Cooper et al., 1995; Hermann et al., 1995; Séraphin, 1995). This region is highly conserved between Saccharomyces species (Fig. 1A) and between budding yeast and humans (Fig. 1B). The carboxy-terminal 95 amino acids (aa) are rich in asparagine (N; 36%) and serine (S; 17%), giving this region a highly hydrophylic character. It is less conserved than the N-terminus, however, homologs from various Saccharomyces species contain similar asparagine-rich stretches that vary in length and position. A notable exception is Lsm4p from S. kluyveri that has a glutamine (Q)-rich region (Fig. 1A). This N and/or Q-rich character of the Lsm4p C-terminus is conserved throughout the budding yeasts (Supplementary Fig. S1). In contrast, most Lsm4p homologs from higher organisms have an abundance of arginine and glycine residues in their C-termini, often in the form of RG repeats (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Fig. S2), that are important for interactions with the SMN complex. Symmetrical dimethylation of the arginine residues is thought to be important for regulation of snRNP assembly (Brahms et al., 2001; Paushkin et al., 2002). S. cerevisiae does not have a known SMN complex equivalent, providing a possible explanation for the absence of RG repeats in yeast Lsm4p. Experiments with Lsm4p of Kluyveromyces lactis suggest that the Lsm4p C-terminus may be needed for efficient RNA degradation (Mazzoni et al., 2003a; Mazzoni et al., 2003b).

Fig. 1.

Lsm4p has an asparagine-rich C-terminal region. (A) The N-terminus of Lsm4p (aa 1-92) contains the Sm-domain; the C-terminus (aa 93-187; boxed) contains N-rich (or Q-rich) stretches of variable lengths. Scer = S. cerevisiae; Spar = S. paradoxus; Sbay = S. bayanus; Smik = S. mikatae; Scas = S. castellii; Skud = S. kudriavzevii; Sklu = S. kluyveri (B) Alignment of budding yeast and human Lsm4 proteins. Lsm4p sequences were aligned using ClustalW. Glutamine (Q) residues are highlighted in grey, asparagine (N) residues in black and RG (arginine/glycine) repeats are underlined.

Here we describe the role of yeast Lsm4p and its C-terminus in Lsm protein aggregation. We show that the ability of Lsm4p to aggregate, although not essential, promotes efficient accumulation of Lsm1-7p in P-bodies. Many other P-body components contain Q/N-rich regions suggestive of a more general role for such aggregation-prone residues in efficient accumulation of these factors in P-bodies. In support of this hypothesis we show that the Q/N-rich region of Ccr4p is prone to aggregation under normal growth conditions and shows increased focal localization under stress conditions. Furthermore we show that the Q/N-rich region of Ccr4p is essential for its accumulation in microscopically visible P-bodies, whereas those of Pop2p and Dhh1p, although not essential for P-body localization, promote their efficient accumulation in these cytoplasmic foci.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

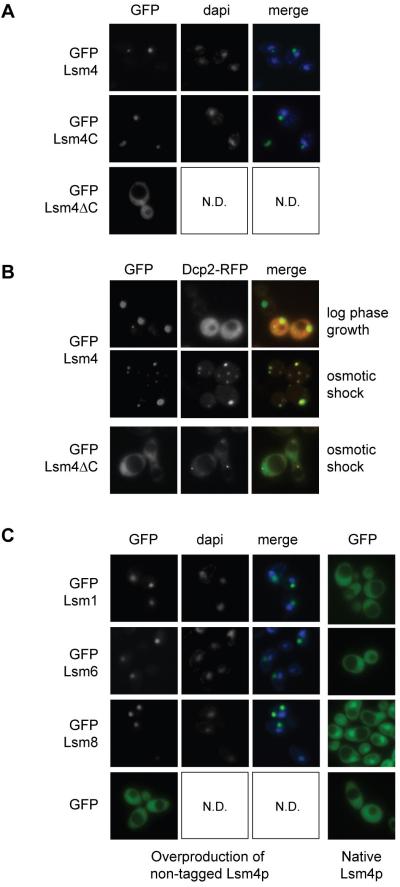

Overproduced Lsm4p or its C-terminus accumulate in foci

While investigating the localization of various GFP-Lsm4p fusions, we observed that GFP fused to full length Lsm4p (GFP-Lsm4) or to its C-terminus (GFP-Lsm4C; aa 92-187) accumulates in cytoplasmic foci as well as in larger aggregates, in a variable percentage of cells (10-60%), whereas GFP fused to the N-terminal half of Lsm4p (GFP-Lsm4∆C; aa 1-92), containing the Sm domain, does not (Fig. 2A). The number of GFP-Lsm4 foci increases after hypo-osmotic shock, indicating that aggregation can be triggered by stress, and that these newly formed foci are probably P-bodies. This is confirmed by co-localization of Dcp2-RFP with GFP-Lsm4p in foci formed after stress. In contrast, Dcp2-RFP is not particularly enriched in the larger Lsm4p aggregates during log phase growth, suggesting that these are probably not P-bodies (Fig. 2B). In cells expressing GFP-Lsm4∆C as the only copy of Lsm4p, Dcp2-RFP localizes to foci after osmotic shock, showing that P-bodies are formed (Fig. 2B). However, GFP-Lsm4∆C localizes throughout the cell, indicating its failure to accumulate in P-bodies even under stress conditions. The virtual absence of GFP-Lsm4∆C in microscopically visible P-bodies is not due to reduced levels of this truncated protein, as shown by Western analysis (Fig. 7E).

Fig. 2.

Overproduction of Lsm4p or its C-terminus leads to aggregation in cytoplasmic foci. (A) GFP-Lsm4 (pMPSLsm4), GFP-Lsm4C (pMPSlsm4D2) and GFP-Lsm4∆C (pMPSLsm4D1) were over-expressed from the MET25 promoter in BY4741 cells grown in SD-Ura-Met. Localization was examined cells during log phase growth. (B) Co-localization of Lsm4p aggregates with Dcp2-RFP (pRP1155) was examined in BY4741 cells grown in SD-Ura-Leu-Met during log phase growth or 20 minutes after hypo-osmotic shock. Dcp2-RFP (pMR171) localization was examined in PGAL-LSM4 cells expressing GFP-Lsm4∆C grown in SD-Ura-His-Met (to prevent competition between GFP-Lsm4∆C and endogenous Lsm4p for incorporation into Lsm1-7p), 20 minutes after hypo-osmotic shock. (C) Localization of GFP-Lsm1 (pGFP-N-Lsm1), GFP-Lsm6 (pMPSLsm6), Lsm8-GFP (pMR83) and GFP (pGFP-N-FUS) was examined in log phase cells over-producing Lsm4p (PGAL-LSM4 cells grown in SDGal-Ura) and in cells with normal levels of Lsm4p (PGAL-LSM4 cells with pUSS1 grown in SD-Ura-Met). Nuclear DNA stained with DAPI is shown in blue.

Other Lsm proteins aggregate upon Lsm4p overproduction

To investigate a potential link between these Lsm4p aggregates and P-bodies, the presence of other proteins was examined. We observed accumulation of all tested GFP-tagged Lsm proteins (Lsm1p, Lsm2p, Lsm6p, Lsm7p and Lsm8p) in similar cytoplasmic aggregates during log phase growth of cells overproducing non-tagged Lsm4p (PGAL-LSM4 strain grown on galactose; Fig. 2C and Supplementary Fig. S3). This was even the case with the normally nuclear Lsm8p, indicating that not only Lsm1-7p but also Lsm2-8p aggregates when Lsm4p is present at high levels. Aggregates were observed mostly in the cytoplasm and occasionally in the nucleolus, judging from co-localization with the nucleolar protein, Nop1p (data not shown). In contrast, normal localization was observed for each of the Lsm proteins in the absence of excess Lsm4p (Fig. 2C), although each of these GFP-tagged proteins was moderately overexpressed from the MET25 promoter. It is therefore likely that these Lsm protein aggregates are not physiologically significant, but simply the results of aggregation of Lsm4p-containing complexes when Lsm4p is present at higher than normal levels. As aggregation was observed with direct interaction partners of Lsm4p in the ring-shaped Lsm complex (Lsm1p, Lsm2p and Lsm8p) as well as with physically more distant subunits (Lsm6p and Lsm7p) it seems likely that overexpressed Lsm4p drives the aggregation of entire Lsm1-7p and Lsm2-8p complexes, probably via its C-terminus. This aggregation is specific to the Lsm proteins, as GFP alone localized throughout the cells regardless of Lsm4p levels (Fig. 2C), and the exclusively nuclear Lhp1p fused with GFP remained nuclear under these conditions and did not form aggregates, although many cells showed abnormal nuclear morphology, which is a phenotype associated with Lsm4p overproduction (Supplementary Fig. S3).

A role for Lsm4p in Lsm1-7p P-body localization

The accumulation of GFP-Lsm4 and GFP-Lsm4C in foci when over-expressed, and failure of GFP-Lsm4∆C to aggregate even under stress conditions, suggests a role for the Lsm4p C-terminus in targeting Lsm1-7p to P-bodies. As a complete Lsm1-7p complex is apparently needed for localization to P-bodies (Ingelfinger et al., 2002; Tharun et al., 2005) the C-terminal deletion is likely to affect localization of the entire Lsm1-7p complex. The localization of GFP-Lsm1 to P-bodies was therefore examined in cells producing either Lsm4p or Lsm4∆Cp (both non-tagged) from the native LSM4 promoter (i.e. not over-produced). In comparison with the accumulation of GFP-Lsm1 in P-bodies (for co-localization of GFP-Lsm1 with Dcp2-RFP see Supplementary Fig. S4) following hypo-osmotic stress of LSM4 cells, there was a reduction in the intensity of GFP-Lsm1 foci that formed in lsm4∆C cells (Fig. 3A), as well as an apparent delay in their formation. To quantify this delay, the number of cells that displayed visible P-bodies 5 minutes and 1 hour after hypo-osmotic shock was counted in the LSM4 and lsm4∆C strains. Whereas 85% of LSM4 cells displayed foci 5 minutes after hypo-osmotic shock, with only a small increase (to 90%) after 1 hour, only 4% of lsm4∆C cells displayed foci after 5 minutes, increasing to 73% after 1 hour (Fig. 3B), with the majority of these foci still weaker than those observed in LSM4 cells. The localization of GFP-Lsm2 and GFP-Lsm6 to P-bodies after hypo-osmotic stress was similarly reduced in the lsm4∆C strain compared to the LSM4 strain (Fig. 3C and D). Taken together, these data strongly suggest that the carboxy-terminal domain of Lsm4p although not actually essential, is nevertheless important for efficient accumulation of Lsm1-7p in P-bodies under stress conditions. As the Lsm4p C-terminal domain seems to be important for efficient recruitment of Lsm1-7p to P-bodies, the C-terminal deletion may also have an effect on the accumulation of other proteins in P-bodies. However, no significant effect was seen on the localization of either Dcp1p or Dcp2p to P-bodies (Fig. 3E and data not shown).

Fig. 3.

The Lsm4 C-terminus is required for efficient localization of Lsm1p to P-bodies. (A) GFP-Lsm1 (pGFP-N-Lsm1) localization 20 minutes after hypo-osmotic shock in LSM4 (MRY71) or lsm4∆C (MRY73) cells (B) The percentage of cells showing GFP-Lsm1 in foci 5 minutes or 1 hour after osmotic shock (n = 100 per time point). (C) GFP-Lsm2 (pMPSLsm2) and (D) GFP-Lsm6 (pMPSLsm6) localization in LSM4 or lsm4∆C cells before and after hypo-osmotic shock (E) Dcp2-RFP (pMR159) localization in log phase LSM4 and lsm4∆C cells grown in SD-His and 20 minutes after osmotic shock. All experiments in this figure were performed with strains expressing non-tagged Lsm4p or Lsm4∆Cp from the native LSM4 promoter.

Detrimental effects of GFP-tagging Lsm4∆Cp

The complete absence of GFP-Lsm4∆C from P-bodies after osmotic shock seems to contradict the mere reduction in P-body accumulation of GFP-Lsm1, Lsm2 and Lsm6 in the lsm4∆C (non-tagged) strain. However, upon closer inspection, GFP-Lsm4∆C was observed to localize weakly to P-bodies after hypo-osmotic shock in a small fraction of cells (< 1%), and to accumulate in cytoplasmic foci in more than 90% of cells grown into late stationary phase (data not shown). Its reduced accumulation in P-bodies is likely to reflect negative effects of the GFP-tag in combination with the C-terminal deletion, possibly by reducing its incorporation into the Lsm1-7p complex. The negative effect of the GFP-tag is emphasized by a slow growth defect of the GFP-Lsm4∆C strain at all temperatures compared to the lsm4∆C strain (with non-tagged protein expressed from its native promoter), which shows slower growth only at 37°C (Supplementary Fig. S5). We cannot formally rule out the possibility that the difference between the non-tagged lsm4∆C and the GFP-Lsm4∆C strains is caused by their different levels of expression (native promoter vs. MET25 promoter), although this would more likely lead to the opposite of what we observe. While this manuscript was in preparation Mazzoni et al. (2007) reported that the asparagine-rich N-terminal region of the K. lactis Lsm4 protein, klLsm4p, which is able to functionally replace its S. cerevisiae homolog, is essential for its own localization to P-bodies in budding yeast (Mazzoni et al., 2007). However, these authors only investigated the localization of a GFP-tagged version of this protein, and not the localization of other Lsm proteins in a strain expressing non-tagged klLsm4∆Cp. Thus the effect of the deletion may not have been distinguished from the additional, detrimental effect of the tag.

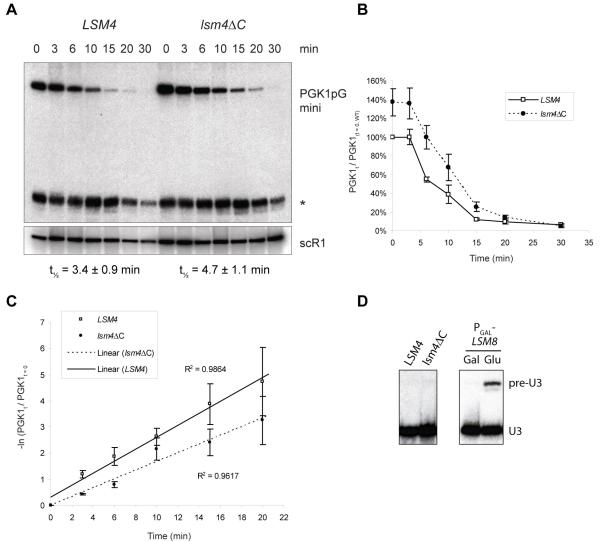

Absence of the Lsm4p C-terminus affects mRNA decay

To determine whether the Lsm4p C-terminal deletion affects mRNA decay, degradation of a PGK1pGmini reporter transcript (Mitchell and Tollervey, 2003) was investigated. This reporter is expressed from the GAL1 promoter, allowing its transcription to be switched off by growth on glucose. The rate of subsequent disappearance of the reporter transcript is used as a measure of its 5′ to 3′ degradation through the major mRNA decay pathway. A small effect was observed, as the mRNA half life increased from 3.4 ± 0.9 minutes in wild type to 4.7 ± 1.1 minutes in the lsm4∆C strain, based on the QRT-PCR data presented in Fig. 4C. Half lives calculated using the Northern data were slightly higher compared to those determined by QRT-PCR, but the relative difference between the two strains was similar. In addition, the steady state level of this transcript appears to be about 40% higher in the lsm4∆C cells compared to the LSM4 cells (Fig. 4B). In contrast, no effect was observed on the splicing of pre-U3 RNA, compared to 12 hours of Lsm8p depletion (Fig. 4D), suggesting that Lsm4∆Cp does not detrimentally affect formation of Lsm2-8p or stability of U6 snRNA. It therefore seems unlikely that the stability or formation of Lsm1-7p is reduced because of this C-terminal deletion, unless the assembly requirements of these two complexes are significantly different. A similar effect on mRNA degradation was reported for klLsm4∆C in K. lactis (Mazzoni et al., 2003a), whereas a seemingly stronger effect was observed for klLsm4∆C in S. cerevisiae (Mazzoni et al., 2003b). The latter may reflect reduced incorporation of the mutant K. lactis Lsm4p into the S. cerevisiae Lsm1-7p complex. Decker et al. (2007) did not find a significant change in the half-lives of PGK1pG or MFA2pG reporter transcripts in the absence of the C-terminal 97 amino acids of Lsm4p, nor did they report on increased steady state levels of these transcripts. The reason for this difference remains unclear; however, the strains used in these studies were constructed in different ways and in different genetic backgrounds. We cannot formally rule out that the effect we see on the PGK1pG half-life is caused by reduced expression and/or stability of Lsm4∆Cp, as we have no antibody to compare its level to that of full-length Lsm4p. However, the absence of an effect on splicing argues against this.

Fig. 4.

The Lsm4 C-terminus is required for efficient mRNA degradation, but not splicing. (A) Degradation of PGK1pGmini reporter transcript in LSM4 (MRY71) or lsm4∆C (MRY73) strains grown in SDGal-Ura after addition of glucose to 4% (w/v); scR1 RNA was used as a loading control; * indicates a stable degradation fragment (B) PGK1pGmini transcript levels over time as a percentage of levels in LSM4 cells at t = 0; averages of three Northerns with vertical bars indicating standard deviations (C) Linearized degradation curves (-ln(PGK1t/PGK1t=0) against time showing averages of QRT-PCR data of 6 RT repeats of two independent biological replicates; vertical bars indicate standard errors; half-lives indicated are based on the linearized QRT-PCR data (D) Northern detecting pre-U3 RNA and U3 RNA in LSM4 and lsm4∆C strains grown in YPDA, and in a PGAL-LSM8 strain (MPS7) before and after 12 hours of growth on glucose.

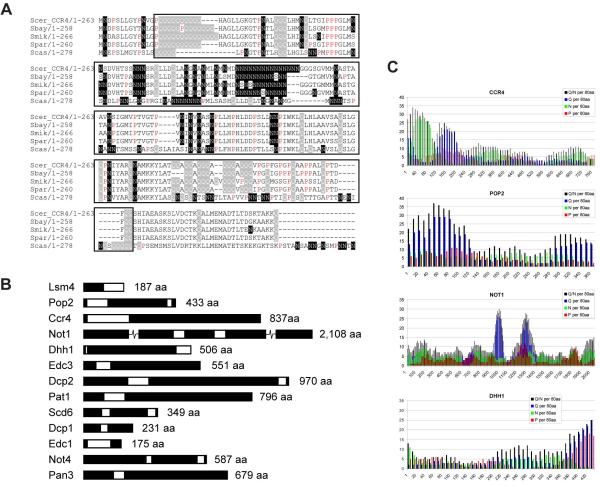

Q/N-rich regions in other P-body components

Investigation of the amino acid sequences of all core components of P-bodies in yeast (Parker and Sheth, 2007) reveals Q and/or N-rich stretches of varying length in many of them, most of which are conserved between various Saccharomyces species (Fig. 5, Table 1 and supplementary Fig. S6). Some (Lsm4p, Ccr4p, Pop2p and Not1p) were previously found in a genome-wide screen looking for yeast proteins with Q/N-rich domains (Michelitsch and Weissman, 2000). Michelitsch and Weissman (2000) used an algorithm to count these residues in consecutive amino acid 80-mers for each of the predicted open reading frames, finding an average Q/N-content of 7.7 per 80-mer in the yeast proteome. We counted Q, N and P residues in a similar fashion in each of the P-body core components. Our results (Table 1) show that all of the 20 proteins tested score above average for Q/N content (Graphic representations are shown in Fig. 5B, C and supplementary Fig. S6). Interestingly, some of the Saccharomyces homologs show further extensions of Q repeats, e.g. Edc3p, Not3p, Not4p and Not5p (supplementary Fig. S6). In addition, many of these polypeptides contain high levels of proline residues in or just downstream of these Q/N-rich regions (Table 1). This is a feature that is also found in other aggregation-prone proteins, e.g. huntingtin, aggregation of which causes Huntington’s disease (Michelitsch and Weissman, 2000). Proline-rich regions often form extended and flexible regions, in many proteins apparently reaching out to facilitate interactions with other proteins, with phosphorylation playing a potential regulatory role. Binding via these proline-rich domains is generally not very specific, but can be both very rapid and strong (Williamson, 1994; Kay et al., 2000). Furthermore, proteins with Q/N-rich domains were previously shown to promote aggregation of heterologous proteins with similar domains (Derkatch et al., 2004). Indeed, Lsm4p was found as one of nine Q/N-rich proteins that, when overproduced, promote de novo appearance of [PSI+], the prion-form of the Q/N-rich Sup35 protein (Derkatch et al., 2001). Based on this behaviour as well as its structural similarities to Sup35p, these authors proposed that Lsm4p itself may be a prion protein. Furthermore, Decker et al. (2007) showed that the prion-like Q/N-rich domain of the Rnq1 prion protein can, at least in part, functionally replace the C-terminal prion-like domain of Lsm4p.

Fig. 5.

Other P-body components contain Q/N-rich regions. (A) Alignment of the N-terminal region of S. cerevisiae Ccr4p with homologs from closely related Saccharomyces species (see Fig. 1 legend for abbreviations). A Q/N -rich region is boxed, with Q residues highlighted in grey, N residues highlighted in black and P residues in red. (B) Schematic representation of P-body components with areas rich in Q and/or N residues indicated in white (approximately to scale; Not1p is broken to fit; lengths are indicated in numbers of amino acids). (C) Q, N and P residues were counted in amino acid 80-mers of Ccr4p, Pop2p, Not1p and Dhh1p starting at position 1, shifting 10 amino acids at a time.

Table 1.

Q, N and P residues counted per amino acid 80-mers in 20 different P-body components

| Protein | Q/N 1 | Q | N | P in Q/N-rich | P (in best 80-mer) 1 | % P (in best 80-mer) | P-rich close to Q/N-rich |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSM4 | 38 | 5 | 33 | 1 | 2 | 2.5% | |

| POP2 | 37 | 29 | 8 | 6 | 12 | 15.0% | yes |

| CCR4 | 34 | 11 | 23 | 4 | 10 | 12.5% | yes |

| NOT1 | 30 | 26 | 4 | 1 | 12 | 15.0% | yes |

| EDC3 | 29 | 19 | 10 | 1 | 5 | 6.3% | |

| DHH1 | 25 | 25 | 0 | 17 | 19 | 23.8% | yes |

| DCP2 | 24 | 13 | 11 | 8 | 20 | 25.0% | yes |

| PAT1 | 23 | 19 | 4 | 18 | 23 | 28.8% | yes |

| SCD6 | 22 | 8 | 14 | 2 | 15 | 18.8% | (yes) 2 |

| DCP1 | 22 | 4 | 18 | 2 | 4 | 5.0% | |

| EDC1 | 22 | 5 | 17 | 10 | 10 | 12.5% | yes |

| NOT4 | 21 | 11 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 12.5% | yes |

| PAN3 | 20 | 0 | 20 | 6 | 15 | 18.8% | yes |

| NOT3 | 19 | 9 | 10 | 2 | 13 | 16.3% | (yes) 2 |

| NOT5 | 15 | 8 | 7 | 3 | 12 | 15.0% | |

| XRN1 | 15 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 24 | 30.0% | (yes) 2 |

| PAN2 | 15 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 10 | 12.5% | |

| LSM1 | 14 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 2.5% | |

| NOT2 | 11 | 8 | 3 | 7 | 8 | 10.0% | |

| EDC2 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 11.3% |

Values indicate the number of residues in the highest scoring 80-mer for that protein.

P-rich region near Q/N-rich region scoring <20

Q/N-rich regions affect P-body localization

It is plausible that Q, N and/or P-rich regions play a role in the accumulation of proteins in P-bodies. We tested Q/N-rich regions from Ccr4p, Pop2p and Dhh1p for their ability to aggregate and/or accumulate in P-bodies when fused to GFP. The Q/N-rich N-terminal region of Ccr4p fused to GFP (Ccr4(1-229)) aggregates in cytoplasmic foci under normal growth conditions (Fig. 6A and B) in approximately 20% of cells, and foci increase in numbers under stress conditions, with more than 50% of cells showing multiple foci per cell. Although the dynamics of increased focal accumulation resembled that of P-body formation, suggesting that the Q/N-rich N-terminus of Ccr4p may be sufficient for P-body localization, we found that the majority did not co-localise with Dcp2-RFP (Fig. 6C). GFP-fusions of the Q/N-rich regions of Pop2p (Pop2(1-156)) and Dhh1p (Dhh1(427-506)) on the other hand do not aggregate under normal growth conditions, but show weak focal concentration in a low percentage of cells (<1%) when stressed, although the majority of cells do not show a change in localization (Fig. 6A). However, GFP-fusions of Pop2p and Dhh1p deleted for these domains (Pop2∆N(147-433) and Dhh1∆C(1-427)) do show decreased P-body localization compared to full-length Pop2p and Dhh1p (Fig. 7A), and Ccr4p deleted for 147 amino acids at its N-terminus (Ccr4∆N(148-837)) completely fails to accumulate in cytoplasmic foci under stress conditions. We quantified the P-body localization of these proteins by counting the number of visible foci per cell at a set time after osmotic shock (Table 2). These numbers are an indication of the level of P-body localization, as a reduction in P-body accumulation will lead to a reduction in the number of visible P-bodies, which generally have variable sizes/intensities. Interestingly, deletion of a further 102 amino acids from the Ccr4p N-terminus (Ccr4∆N2(250-837)) leads to exclusively nuclear localization (Fig. 7B). The latter suggests that Ccr4p normally shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm and that its nuclear export depends on sequences within the N-terminal domain. The tendency for aggregation of these Q/N-rich regions is further emphasized by the fact that full-length Pop2p expressed from the MET25 promoter aggregates in bright nuclear foci when tagged at the C-terminus (Pop2-GFP, Fig. 7C), at a much lower rate when tagged at the (Q/N-rich) N-terminus (data not shown) and not at all in the absence of this N-terminus (Pop2∆N-GFP, Fig. 7C). As these experiments were performed in the presence of natively expressed non-tagged proteins, which may contribute to the observed absence of GFP-Ccr4∆N concentration in P-bodies, we investigated the localization of this protein in ccr4∆ as well as xrn1∆ strains. Whereas GFP-Ccr4∆N still failed to concentrate in microscopically visible foci in the absence of native Ccr4p (Fig. 7D), some weak foci were observed in the absence of Xrn1p (Supplementary Fig. S8), which generally leads to larger and more abundant P-bodies by preventing 5′ to 3′ degradation of transcripts. For Ccr4∆Np and Pop2∆Np the reduced P-body localization is not due to reduced levels of these truncated proteins as Western analysis showed no difference between levels of full length and mutant proteins. As the level of Dhh1∆Cp was only 60% of that of full length Dhh1p we can not rule out that its reduced P-body localization may, in part, be due to the lower protein level.

Fig. 6.

The Q/N-rich region from Ccr4p aggregates in cytoplasmic foci and responds to stress. (A) Localization of GFP-tagged Q/N-rich regions of Ccr4p (aa 1-229; pMR202), Pop2p (aa 1-156; pMR203) and Dhh1p (aa 427-506; pMR204) before and after hypo-osmotic shock (B) GFP-Ccr4(1-229) aggregates localize to the cytoplasm as shown in these fixed cells with DAPI stained nuclear DNA (C) The majority of GFP-Ccr4(1-229) aggregates do not co-localize with Dcp2-RFP (pRP1155) foci after osmotic shock.

Fig. 7.

Q/N-rich regions from Ccr4p, Pop2p and Dhh1p contribute to efficient accumulation of these proteins in P-bodies. (B) Localization of GFP-tagged full-length Ccr4p (pMR212), Pop2p (pMR214), Dhh1p (pMR210) or truncated versions of these proteins (Ccr4∆N(148-837) from pMR218, Pop2∆N(147-433) from pMR215, Dhh1∆C(1-427) from pMR211) before and after osmotic shock. All GFP-fusions were expressed in BY4741 cells and localization was examined in cells during normal growth (normal) or 20-40 minutes after osmotic shock (stress). (B) Localization of GFP-tagged Ccr4∆N(148-837) and Ccr4∆N2 (aa 250-837; pMR213) in fixed cells with DAPI-stained nuclear DNA (C) Localization of C-terminally GFP-tagged full-length Pop2p (pMR216) or Pop2∆Np (pMR217); DAPI-stained nuclear DNA in blue. (D) Localization of GFP-Ccr4, GFP-Ccr4∆N and Dcp2-RFP in ccr4∆ cells (Y10387) 30 min after hypo-osmotic shock (E) Anti-GFP Western analysis of full length and truncated Lsm4, Ccr4, Pop2 and Dhh1 proteins. Curiously, GFP-Ccr4 (122 kDa) migrates faster than GFP-Ccr4∆N (106 kDa), but slower than GFP-Ccr4∆N2 (95 kDa; Fig. 7E), and all three GFP-Ccr4 proteins migrate faster than their predicted molecular weights. The presence or absence of the highly polar N-terminal region of Ccr4p causes a change in the effective charge of the entire protein (predicted charge at pH 7 is -5.8, -4.0 and -5.5 respectively) and may affect protein conformation resulting in unusual migration during SDS-PAGE. Nop1p was used as a loading control.

Table 2.

Quantification of P-body localization

| Protein | Number of foci per cell | Number of cells examined |

|---|---|---|

| Ccr4 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 138 |

| Ccr4∆N (aa148-837) | 0 | > 1000 |

| Pop2 | 4.8 ± 1.6 | 80 |

| Pop2∆N (aa147-433) | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 93 |

| Dhh1 | 10.7 ± 5.3 | 35 |

| Dhh1∆C (aa1-427) | 3.5 ± 1.1 | 83 |

In summary, although not absolutely essential, Q/N-rich sequences in Pop2p, Ccr4p and Dhh1p contribute to efficient accumulation of these proteins in P-bodies under stress conditions. This is most obvious for Ccr4p, which, in the absence of its N-terminal 147 amino acids is not microscopically detectable in P-bodies in otherwise normal cells. Increased focal accumulation of the N-terminal 229 amino acids fused to GFP under stress conditions, suggests that this region is capable of regulated aggregation in response to stress. The fact that the majority of these foci do not co-localise with Dcp2p, suggests that additional parts of Ccr4p are necessary for proper P-body localization, most likely through additional protein-protein interactions. It would therefore be interesting to further investigate the requirements of the Q/N-rich regions as well as other parts of these proteins for these interactions.

Is a mechanism for protein accumulation in P-bodies conserved?

As the C-terminal region of S. cerevisiae Lsm4p is semi-conserved between Saccharomyces species, at least in the high content of N and/or Q residues (Supplementary Fig. S1), the ability to promote Lsm1-7p accumulation in P-bodies is likely to be conserved in these yeasts as well as in other budding yeasts. In fact, this was shown to be true for the budding yeast K. lactis Lsm4p produced in S. cerevisiae (Mazzoni et al., 2007). The human homolog on the other hand does not show a significant enrichment in Q or N residues, apart from a short stretch of 5 glutamines. Indeed, full-length human LSm4 fused to GFP did not aggregate when over-expressed in wild-type yeast cells, nor did it accumulate in foci under stress conditions. Surprisingly, it mostly accumulated in the nucleus instead (data not shown). As it was not able to support viability in the absence of native Lsm4p expression (data not shown), it may be unable to form a functional complex with yeast Lsm proteins. It is possible that residues in other human LSm1-7 complex members normally contribute to its accumulation in P-bodies. Notably, the short N or C-terminal extensions of hLSm1, 2, 3 and 7 proteins contain relatively high levels of glutamine residues. However, if, as we propose, Q/N-rich sequences contribute to a rapid response to stimuli in yeast, this may not be needed in human cells, as hLSm1-7p accumulates in P-bodies even under normal growth conditions.

Q/N-rich regions do not seem to be conserved in the human homologs of budding yeast Ccr4, Pop2 and Dhh1 proteins either; they are significantly shorter, lacking the N-terminal and C-terminal Q/N-rich regions respectively (Supplementary Fig. S7). Perhaps the function of these protein domains has been replaced by alternative domains, possibly in other polypeptides with which they interact. For example, GW182 contains an internal Q/P-rich region that is essential, but not sufficient, for its own P-body localization and that of Ago1 (Behm-Ansmant et al., 2006). Another P-body component specific to higher eukaryotes, Ge-1/Hedls, contains a C-terminal repetitive sequence rich in hydrophobic residues that is essential for P-body localization and parts of which aggregate in cytoplasmic foci that are not P-bodies (Yu et al., 2005). In addition Ge-1/Hedls, Dcp2 and TNRC6B from humans as well as other higher eukaryotes contain high levels of Q and/or N residues (Decker et al., 2007). Thus, alternative aggregation-prone regions may have replaced some of the yeast Q/N-rich domains in higher eukaryotes, at least some of which are likely to play a role in P-body assembly.

Aggregation of P-body components via their Q/N-rich regions could promote efficient P-body formation. Whether this is really the case and, if so, whether this occurs through prion-like aggregation or through specific interactions via putative modular ‘polar zipper’ protein-protein interaction domains (Perutz et al., 1994; Michelitsch and Weissman, 2000) remains to be determined. The importance of the Q/N-rich protein Edc3p/Lsm16p in combination with Lsm4p in P-body assembly in yeast, which came to light while this manuscript was being revised (Decker et al., 2007), is in support of this hypothesis. An intriguing question is how Lsm4p aggregation, and that of other P-body components, is prevented under normal growth conditions. Post-translational modifications, e.g. phosphorylation of Lsm4p or other (Lsm) proteins, likely play a role. Such modifications could allow the cell to respond quickly and efficiently to changes in conditions, and might regulate the levels and intracellular localizations of Lsm1-7p and Lsm2-8p, in addition to promoting P-body localization. Such a mechanism could also regulate the competition between these two complexes that was observed by Spiller et al. (2007b). Similarly, post-translational modifications, e.g. of the N-terminal region of Ccr4p, could allow P-body localization of other proteins involved in RNA degradation. Q-rich regions in TIA-1 and Pum2 have previously been shown to contribute to protein accumulation in stress granules (Gilks et al., 2004; Vessey et al., 2006). We now show that at least some of the Q/N-rich domains in P-body components play a role in assembly of these RNA processing bodies. Presence of Q/N-rich regions in many other proteins involved in various aspects of RNA metabolism (Michelitsch and Weissman, 2000; Decker et al., 2007) hints at the possibility of a more general role for these prion-like domains in functional protein aggregation, in addition to stress granule and P-body assembly.

METHODS

Plasmids and strains

For a complete list of plasmids and strains used see supplementary Table S1 and S2.

Microscopy

Cells were grown at 30°C to mid-log phase in synthetic dropout (SD) medium. To stress cells, cultures were centrifuged and cells were resuspended in water. Live cells were placed on microscopy slides and examined by bright field and/or fluorescence microscopy using a Leica FW4000 fluorescence microscope. Fixing of cells followed by DAPI staining was performed as previously described (Spiller et al., 2007b). Images were captured using LeicaFW4000 software (Scanalytics, Fairfax, VA) with a CH-250 16-bit, cooled CCD camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ).

RNA analyses

Cultures were grown at 30°C in synthetic dropout medium containing 2% (w/v) galactose. Transcription of the PGK1pGmini reporter gene was stopped by the addition of glucose to 4% (w/v) and 10 OD units were snap-chilled at the indicated times after the addition of glucose. RNA extractions and Northern blot analyses of 6% acrylamide/urea gels were as described (Mayes et al., 1999). The following oligonucleotide probes were used for Northern hybridizations: to detect the PGK1pGmini reporter transcript AATTGATCTATCGAGGAATTCC, to detect scR1 RNA ATCCCGGCCGCCTCCATCAC and to detect U3 RNA GGTTATGGGACTCATCA. Northern blots were quantified using a STORM 860 PhosphorImager and ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics).

QRT-PCR (Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR)

Ten μg of total RNA was treated with DNase1 (0.9 U RQ1, Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was prepared from 5 μg of DNase-treated RNA in a 10 μl reaction: 1x First strand synthesis buffer, 2.5 mM DTT, 10 U RNase inhibitor (Roche), 0.75 mM dNTPs, 7.5 U ThermoScript RNaseH- (Invitrogen) and 500 nM of PGK1pGmini-specific primer (AGCGTAAAGGATGGGGAAAGAGAA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A negative control reaction was performed in the absence of reverse transcriptase. Any remaining RNA was hydrolyzed by incubating reactions for 1 hour at 37°C after addition of 15 μl of 0.1 mg/ml RNaseA (Roche). Quantitative PCRs (qPCRs) were performed with SYBR Green JumpStart Taq ReadyMix (Sigma) in a Stratagene MX3005P real-time PCR machine in 10 μl reactions: 6 μl containing 5 μl 2x SYBR Green ReadyMix, 300 nM of each primer (F: ATTGAAATGAAATGAAATCGAAGGAATTTGG; R: AGCGTAAAGGATGGGGAAAGAGAA) and 0.5x ROX, plus 4 μl of cDNA template (diluted 1 in 20 after RT-PCR). Cycling parameters were as follows: 2 min at 94°C, then 50 cycles of 10 s at 94°C, 10 s at 63°C and 20 s at 72°C. Each qPCR reaction was performed in triplicate for each repeat RT reaction.

Western Analysis

For crude protein extracts (Volland et al., 1994) 3 OD600 units of yeast cells were lysed in 0.5 ml of 0.2 M NaOH on ice for 10 minutes, followed by TCA precipitation (final 5% w/v) for 10 minutes on ice. After centrifugation, the pellet was resuspended in 35 μl of dissociation buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 4 mM EDTA, 4% SDS, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 2% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol, 0.02% (w/v) BPB) and 15 μl of 1 M Tris base. Samples were heated at 95°C for 10 min before separation by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membrane and detected with mouse anti-GFP (BD Bioscience) or anti-Nop1p antibodies, and sheep-anti-mouse IgG-HRP (Amersham Bioscience).

Polypeptide alignments

Amino acid sequences of P-body components were obtained from the Saccharomyces Genome Database (http://www.yeastgenome.org/) or the NCBI Entrez Protein database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez). Alignments were made using the ClustalW Multiple Sequence Alignment tool (Thompson et al., 1994) inside Jalview 2.2 (Clamp et al., 2004).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Roy Parker and David Tollervey for reagents, Jon Houseley for critical reading of the manuscript, and David Barrass, Daniela Hahn and Olivier Cordin for assistance. This work was funded by a Wellcome Trust Prize Studentship 71448 and Royal Society support to MAMR, a studentship from The Darwin Trust of Edinburgh to MPS and Wellcome Trust Grant 067311. JDB is the Royal Society Darwin Trust Research Professor.

REFERENCES

- Achsel T, Brahms H, Kastner B, Bachi A, Wilm M, Lührmann R. A doughnut-shaped heteromer of human Sm-like proteins binds to the 3′-end of U6 snRNA, thereby facilitating U4/U6 duplex formation in vitro. EMBO J. 1999;18:5789–5802. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.20.5789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckham C, Hilliker A, Cziko AM, Noueiry A, Ramaswami M, Parker R. The DEAD-Box RNA Helicase Ded1p Affects and Accumulates in Saccharomyces cerevisiae P-Bodies. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:984–993. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-09-0954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behm-Ansmant I, Rehwinkel J, Doerks T, Stark A, Bork P, Izaurralde E. mRNA degradation by miRNAs and GW182 requires both CCR4:NOT deadenylase and DCP1:DCP2 decapping complexes. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1885–1898. doi: 10.1101/gad.1424106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouveret E, Rigaut G, Shevchenko A, Wilm M, Séraphin B. A Sm-like protein complex that participates in mRNA degradation. EMBO J. 2000;19:1661–1671. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.7.1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahms H, Meheus L, de B, Fischer U, Lührmann R. Symmetrical dimethylation of arginine residues in spliceosomal Sm protein B/B’ and the Sm-like protein LSm4, and their interaction with the SMN protein. RNA. 2001;7:1531–1542. doi: 10.1017/s135583820101442x. V. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clamp M, Cuff J, Searle SM, Barton GJ. The Jalview Java alignment editor. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:426–427. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M, Parkes V, Johnston LH, Beggs JD. Identification and characterization of Uss1p (Sdb23p): a novel U6 snRNA-associated protein with significant similarity to core proteins of small nuclear ribonucleoproteins. EMBO J. 1995;14:2066–2075. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07198.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cougot N, Babajko S, Séraphin B. Cytoplasmic foci are sites of mRNA decay in human cells. J. Cell Biol. 2004;165:31–40. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker CJ, Teixeira D, Parker R. Edc3p and a glutamine/asparagine-rich domain of Lsm4p function in processing body assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 2007;179:437–449. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derkatch IL, Bradley ME, Hong JY, Liebman SW. Prions affect the appearance of other prions: the story of [PIN(+)] Cell. 2001;106:171–182. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derkatch IL, Uptain SM, Outeiro TF, Krishnan R, Lindquist SL, Liebman SW. Effects of Q/N-rich, polyQ, and non-polyQ amyloids on the de novo formation of the [PSI+] prion in yeast and aggregation of Sup35 in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:12934–12939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404968101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eystathioy T, Jakymiw A, Chan EK, Séraphin B, Cougot N, Fritzler MJ. The GW182 protein colocalizes with mRNA degradation associated proteins hDcp1 and hLSm4 in cytoplasmic GW bodies. RNA. 2003;9:1171–1173. doi: 10.1261/rna.5810203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilks N, Kedersha N, Ayodele M, Shen L, Stoecklin G, Dember LM, Anderson P. Stress granule assembly is mediated by prion-like aggregation of TIA-1. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:5383–5398. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann H, Fabrizio P, Raker VA, Foulaki K, Hornig H, Brahms H, Lührmann R. snRNP Sm proteins share two evolutionarily conserved sequence motifs which are involved in Sm protein-protein interactions. EMBO J. 1995;14:2076–2088. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingelfinger D, Arndt-Jovin DJ, Lührmann R, Achsel T. The human LSm1-7 proteins colocalize with the mRNA-degrading enzymes Dcp1/2 and Xrnl in distinct cytoplasmic foci. RNA. 2002;8:1489–1501. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakymiw A, Lian S, Eystathioy T, Li S, Satoh M, Hamel JC, Fritzler MJ, Chan EK. Disruption of GW bodies impairs mammalian RNA interference. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7:1267–1274. doi: 10.1038/ncb1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakymiw A, Pauley KM, Li S, Ikeda K, Lian S, Eystathioy T, Satoh M, Fritzler MJ, Chan EK. The role of GW/P-bodies in RNA processing and silencing. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120:1317–1323. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay BK, Williamson MP, Sudol M. The importance of being proline: the interaction of proline-rich motifs in signaling proteins with their cognate domains. FASEB J. 2000;14:231–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Rivas FV, Wohlschlegel J, Yates JR, III, Parker R, Hannon GJ. A role for the P-body component GW182 in microRNA function. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7:1261–1266. doi: 10.1038/ncb1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayes AE, Verdone L, Legrain P, Beggs JD. Characterization of Sm-like proteins in yeast and their association with U6 snRNA. EMBO J. 1999;18:4321–4331. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.15.4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoni C, D’Addario I, Falcone C. The C-terminus of the yeast Lsm4p is required for the association to P-bodies. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:4836–4840. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoni C, Mancini P, Madeo F, Palermo V, Falcone C. A Kluyveromyces lactis mutant in the essential gene KlLSM4 shows phenotypic markers of apoptosis. FEMS Yeast Res. 2003a;4:29–35. doi: 10.1016/S1567-1356(03)00151-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoni C, Mancini P, Verdone L, Madeo F, Serafini A, Herker E, Falcone C. A truncated form of KlLsm4p and the absence of factors involved in mRNA decapping trigger apoptosis in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003b;14:721–729. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-05-0258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelitsch MD, Weissman JS. A census of glutamine/asparagine-rich regions: implications for their conserved function and the prediction of novel prions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:11910–11915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.22.11910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell P, Tollervey D. An NMD pathway in yeast involving accelerated deadenylation and exosome-mediated 3′-->5′ degradation. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:1405–1413. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannone BK, Xue D, Wolin SL. A role for the yeast La protein in U6 snRNP assembly: evidence that the La protein is a molecular chaperone for RNA polymerase III transcripts. EMBO J. 1998;17:7442–7453. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker R, Sheth U. P bodies and the control of mRNA translation and degradation. Mol. Cell. 2007;25:635–646. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paushkin S, Gubitz AK, Massenet S, Dreyfuss G. The SMN complex, an assemblyosome of ribonucleoproteins. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2002;14:305–312. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00332-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perutz MF, Johnson T, Suzuki M, Finch JT. Glutamine repeats as polar zippers: their possible role in inherited neurodegenerative diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994;91:5355–5358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkington GR, Parker R. Pat1 contains distinct functional domains that promote P-body assembly and activation of decapping. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;28:1298–1312. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00936-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehwinkel J, Behm-Ansmant I, Gatfield D, Izaurralde E. A crucial role for GW182 and the DCP1:DCP2 decapping complex in miRNA-mediated gene silencing. RNA. 2005;11:1640–1647. doi: 10.1261/rna.2191905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgado-Garrido J, Bragado-Nilsson E, Kandels-Lewis S, Séraphin B. Sm and Sm-like proteins assemble in two related complexes of deep evolutionary origin. EMBO J. 1999;18:3451–3462. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.12.3451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Séraphin B. Sm and Sm-like proteins belong to a large family: identification of proteins of the U6 as well as the U1, U2, U4 and U5 snRNPs. EMBO J. 1995;14:2089–2098. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07200.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheth U, Parker R. Decapping and decay of messenger RNA occur in cytoplasmic processing bodies. Science. 2003;300:805–808. doi: 10.1126/science.1082320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller MP, Boon KL, Reijns MAM, Beggs JD. The Lsm2-8 complex determines nuclear localization of the spliceosomal U6 snRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007a;35:923–929. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller MP, Reijns MA, Beggs JD. Requirements for nuclear localization of the Lsm2-8p complex and competition between nuclear and cytoplasmic Lsm complexes. J. Cell Sci. 2007b doi: 10.1242/jcs.019943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira D, Parker R. Analysis of P-body assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007;18:2274–2287. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-03-0199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira D, Sheth U, Valencia-Sanchez MA, Brengues M, Parker R. Processing bodies require RNA for assembly and contain nontranslating mRNAs. RNA. 2005;11:371–382. doi: 10.1261/rna.7258505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tharun S, He W, Mayes AE, Lennertz P, Beggs JD, Parker R. Yeast Sm-like proteins function in mRNA decapping and decay. Nature. 2000;404:515–518. doi: 10.1038/35006676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tharun S, Muhlrad D, Chowdhury A, Parker R. Mutations in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae LSM1 gene that affect mRNA decapping and 3′ end protection. Genetics. 2005;170:33–46. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.034322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdone L, Galardi S, Page D, Beggs JD. Lsm proteins promote regeneration of pre-mRNA splicing activity. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:1487–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vessey JP, Vaccani A, Xie Y, Dahm R, Karra D, Kiebler MA, Macchi P. Dendritic localization of the translational repressor Pumilio 2 and its contribution to dendritic stress granules. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:6496–6508. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0649-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volland C, Urban-Grimal D, Geraud G, Haguenauer-Tsapis R. Endocytosis and degradation of the yeast uracil permease under adverse conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:9833–9841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson MP. The structure and function of proline-rich regions in proteins. Biochem. J. 1994;297(Pt 2):249–260. doi: 10.1042/bj2970249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu JH, Yang WH, Gulick T, Bloch KD, Bloch DB. Ge-1 is a central component of the mammalian cytoplasmic mRNA processing body. RNA. 2005;11:1795–1802. doi: 10.1261/rna.2142405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.