Abstract

Available instances of inheritance of epigenetic transgenerational phenotype are limited to environmental exposures during embryonic and adult gonadal development. Adult exposures can also affect gametogenesis and thereby potentially result in reprogramming of the germline. Although examples of epigenetic effects on gametogenesis exist, it is notable that transgenerational inheritance of environment-induced adult phenotype has not yet been reported. Epigenetic codes are considered to be critical in neural plasticity. A Drosophila systems model of pentylenetetrazole (PTZ) induced long-term brain plasticity has recently been described. In this model, chronic PTZ treatment of adult males causes alterations in CNS transcriptome. Here, we describe our search for transgenerational spermatogenic inheritance of PTZ induced gene expression phenotype acquired by adult Drosophila males. We generated CNS transcriptomic profiles of F1 adults after treating F0 adult males with PTZ and of F2 adults resulting from a cross between F1 males and normal females. Surprisingly, microarray clustering showed F1 male profile as closest to F1 female and F0 male profile closest to F2 male. Differentially expressed genes in F1 males, F1 females and F2 males showed significant overlap with those caused by PTZ. Interestingly, microarray evidence also led to the identification of upregulated rRNA in F2 males. Next, we generated microarray expression profiles of adult testis from F0 and F1 males. Further surprising, clustering of CNS and testis profiles and matching of differentially expressed genes in them provided evidence of a spermatogenic mechanism in the transgenerational effect observed. To our knowledge, we report for the first time detection of transgenerational spermatogenic inheritance of adult acquired somatic gene expression characteristic. The Drosophila systems model offers an excellent opportunity to understand the epigenetic mechanisms underlying the phenomenon. The finding that adult acquired transcriptomic alteration in soma is spermatogenically inherited across generations has potential implications in human health and evolution.

Introduction

Environmental exposures influence health and disease. Understanding environment-genome interactions is crucial for dissecting the underlying mechanisms. Whereas only a few of the environmental factors that cause disease susceptibility have been shown to promote mutation in DNA sequence, emerging evidence suggests that environmental influences may mainly be mediated by epigenetics, i.e., the processes that lead to changes in gene expression without a change in the DNA sequence [1], [2], [3]. Because epigenetic changes can alter whole-genome expression profiles of various cell types that constitute different tissues and organs, these modifications provide plausible basis for transcriptomic alterations that are associated with various diseases [4], [5]. Epigenetic alterations can be mitotically inherited in somatic cells and can exert long-term effect on gene expression. This mechanism is supposed to underlie risk of developing diseases secondary to prenatal and early postnatal environmental exposures [6], [7], [8], [9]. Importantly, increasing evidence suggests that meiotically heritable epigenetic modifications may also be transgenerationally inherited [2], [10], [11], [12], [13]. Available instances of inheritance of epigenetic transgenerational phenotype are limited to environmental exposures during embryonic and adult gonadal development [14], [15]. Adult exposures can also affect gametogenesis and thereby potentially result in reprogramming of the germline [14]. Although examples of epigenetic effects on gametogenesis exist, it is notable that transgenerational inheritance of environment-induced adult phenotype has not yet been reported [14], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20].

Model organisms have proven highly valuable in understanding epigenetic mechanisms of gene regulation [21]. Vertebrate and invertebrate species share numerous aspects of germ cell behavior, migration and gonadal development [22], [23]. Certain molecular aspects of germ cells and gonadal development are also suggested to be similar in different organisms [22], [23]. Notably, available data suggests that major features of chromatin condensation in Drosophila spermatogenesis correspond to those of the epigenetic event in mammalian species [24]. All stages of spermatogenesis, from germline stem cell division to functional sperm production, are present in adult Drosophila testes [25]. We selected Drosophila to search for evidence of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance of environmental effect following exposure of adult males. Epigenetic codes are considered to be critical in neural plasticity [26]. A Drosophila systems model of pentylenetetrazole (PTZ) induced long-term brain plasticity has recently been described [27]. In this model, chronic PTZ treatment of adult males causes alterations in CNS transcriptome [27]. Readily available microarray data showing transcriptomic alteration in heads of PTZ treated male flies motivated us to search for transgenerational effect of the drug, if any, at gene expression level. Transgenerational transcriptomes have earlier been analyzed after embryonic germline exposure [3], [28], [29]. Our focus here was to specifically analyze transgenerational transcriptome after adult spermatogenic exposure. Use of genetically identical animals is required for demonstrating a transgenerational epigenetic effect [30]. We thus used a freshly generated isogenic line of Drosophila in our analysis. The wild-type strain was the same that was used previously for developing the PTZ model [27].

Results

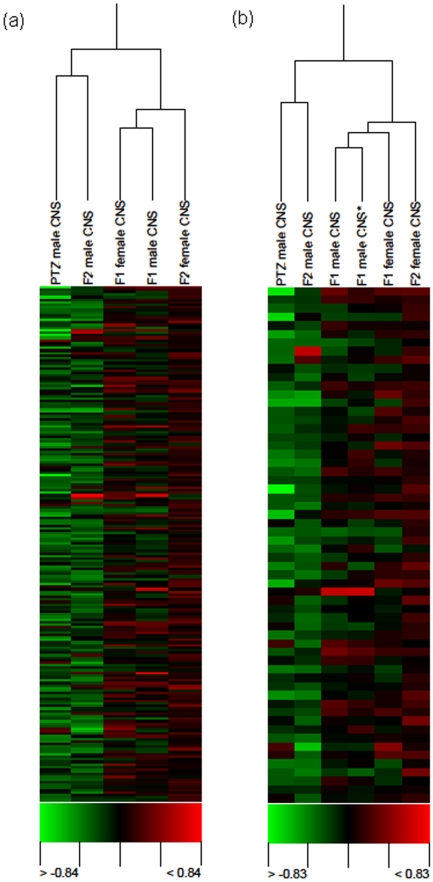

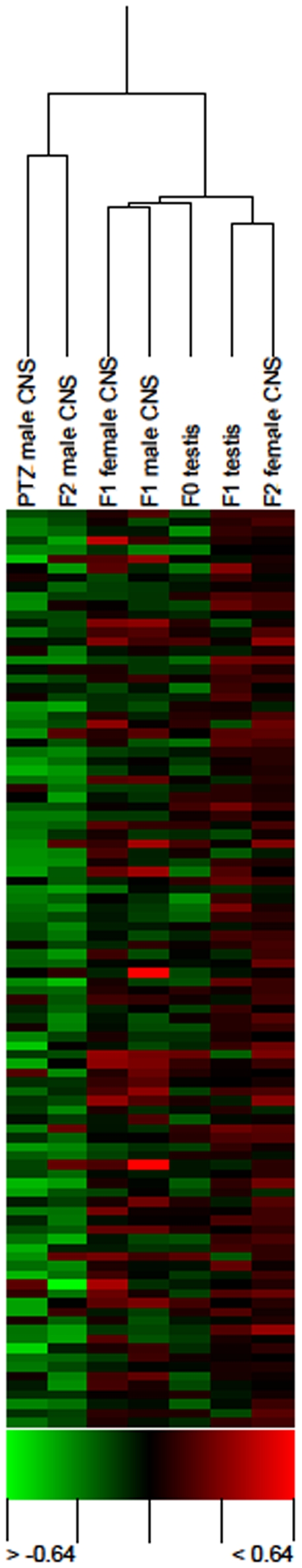

The previous study reported microarray gene expression profiles after chronic exposure of unmated males with PTZ for up to seven days [27]. We treated unmated adult F0 males with PTZ for seven days and after a washout period of seven days mated them with normally grown females in vials containing normal food (NF). PTZ was never used anytime henceforth. Head gene expression profiles were generated for unmated F1 males and virgin F1 females resulting from the above cross. Demonstrating transgenerational inheritance secondary to adult exposure requires analysis of F2 generation [14]. To raise F2, we mated F1 males with independently obtained normal females having no history of PTZ exposure in earlier generation. Heads of unmated F2 males and virgin F2 females were used for generating microarray profiles. Clustering of these profiles along with previously reported [27] PTZ male profile showed similarity between F2 male and the latter and between F1 male and F1 female ( Fig. 1a ). F2 female profile was distinct from F2 male ( Fig. 1a ). The above result showed that PTZ induced transcriptomic alteration is transmitted to F2 generation, with the mode of transmission being complex. To examine robustness of this microarray profiling based evidence, we generated another set of F1 male CNS microarrays. Importantly, the two F1 male profiles clustered together ( Fig. 1b ). This demonstrated that our expression profiles were robust enough for deriving valid inferences. Next, we examined differentially expressed genes in our microarrays. Presence of differentially expressed genes in all the samples – F1 males and females, and F2 males and females - provided further evidence that PTZ exposure in F0 causes genomewide expression perturbation across generations ( Table S1 , supporting material). Gene ontology (GO) based analysis showed enrichment of various biological processes in differentially expressed genes ( Table S2 , supporting material).

Figure 1. Hierarchical clustering of CNS expression profiles.

City Block similarity metric and average linkage methods were used for hierarchical clustering of arrays. The cluster was generated using Acuity 4.0 (Molecular Devices). Each time point represents mean of normalized log2 ratio (635/534) of four biological replicates with balanced dye-swaps. Note clustering of PTZ treated males' profile with their grandsons (a). Cluster shown in (b) represents all the profiles in (a) and a freshly generated F1 male profile. Reproducibility of expression profiling is evident from similarity between the two F1 male profiles (b). PTZ profile shown here was derived from previously reported [27] microarray data related to seven days of drug treatment. * indicates replication set.

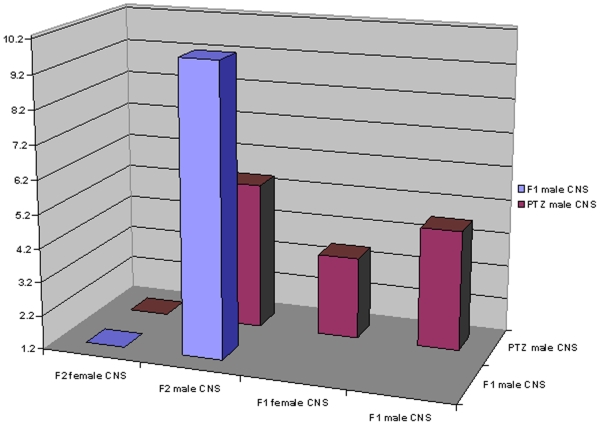

We reasoned that if drug-induced transcriptomic perturbation is transgenerationally inherited then statistically significant overlap may be observed between genes regulated by PTZ [27] and those differentially expressed in F1 and F2. Interestingly, F1 males, F1 females and F2 males showed significant overlap ( Fig. 2 ). Besides, genes in F1 males significantly overlapped with those in F2 males ( Fig. 2 ). A lack of overlap in F2 females suggested that pattern of inheritance from F0 to F1 is different than that from F1 to F2. Cumulatively, our results demonstrated that PTZ's transcriptomic effect is transgenerationally inherited.

Figure 2. Overlap between differentially expressed CNS genes.

PTZ genes used in this analysis was derived from previously reported [27] microarray data related to seven days of drug treatment. PTZ genes were compared to those in F1 and F2 generations, whereas F1 male genes were compared only to F2. Hypergeometric distribution p values (−log10) are plotted on y-axis. Note significant overlap (≥1.3) in all except F2 female pair-wise comparisons. Differentially expressed genes used in the analysis are listed in Table S1.

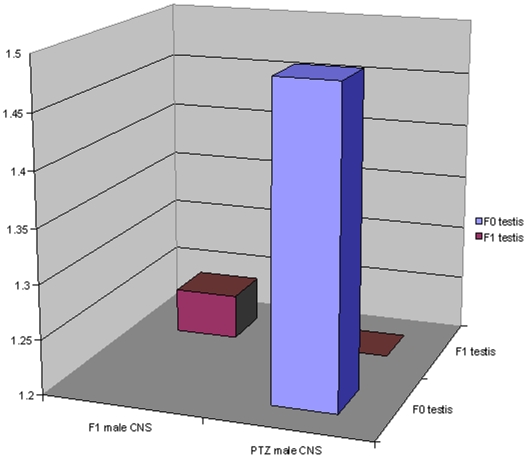

We next examined if a gametogenic mechanism is involved in the transgenerational effects observed. Majority of transcription in adult Drosophila testis occurs in spermatocytes products of which are required for spermatid differentiation [31]. We thus generated microarray expression profiles of F0 and F1 adult testis. Interestingly, both F0 and F1 showed transcriptomic alteration. Differentially expressed genes were identified in F0 as well as F1 testis ( Table S3 , supporting material). These genes were found to enrich a few GO biological processes ( Table S4 , supporting material). Importantly, PTZ regulated CNS genes [27] showed significant overlap with differentially expressed F0 testis genes ( Fig. 3 ). Also, genes in F1 male CNS and F1 testis overlapped with a borderline significance ( Fig. 3 ). A lack of overlap between F0 and F1 testis genes supported the above observation that genomic mechanism underlying F0 to F1 transmission is different from that of F1 to F2. To further examine if what we observe is a case of transgenerational spermatogenic inheritance, we clustered CNS and testis microarrays together. Interestingly, F0 testis clustered with F1 male and F1 females whereas F1 testis clustered with F2 female ( Fig. 4 ). Cumulatively, the above results provided evidence that transcriptomic perturbation set off by PTZ in CNS perpetuates to future generations by gametic involvement.

Figure 3. Overlap between differentially expressed testis and CNS genes.

PTZ genes used in this analysis was derived from previously reported [27] microarray data related to seven days of drug treatment. PTZ CNS genes were compared to those in PTZ testis (F0) and F1 CNS, whereas F1 testis genes were compared only to F1 CNS. Hypergeometric distribution p values (−log10) are plotted on y-axis. Note significant overlap (≥1.3) between PTZ CNS and F0 testis genes and an overlap between F1 CNS and F1 testis genes with borderline significance (1.24). Differentially expressed genes used in the analysis are listed in Table S1 and S3.

Figure 4. Hierarchical clustering of expression profiles of testis and CNS.

City Block similarity metric and average linkage methods were used for hierarchical clustering of arrays. The cluster was generated using Acuity 4.0 (Molecular Devices). Each time point represents mean of normalized log2 ratio (635/534) of four biological replicates with balanced dye-swaps. PTZ profile shown here was derived from previously reported [27] microarray data related to seven days of drug treatment.

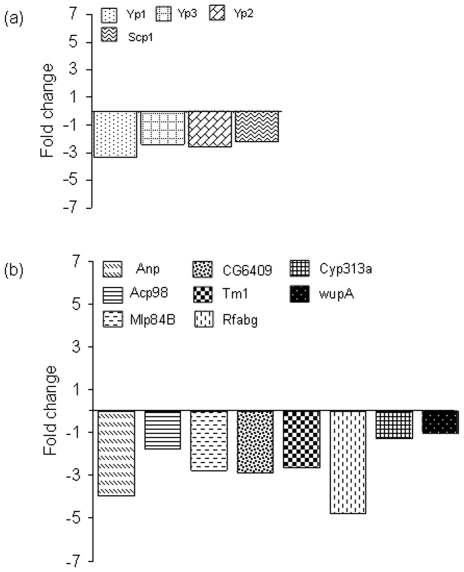

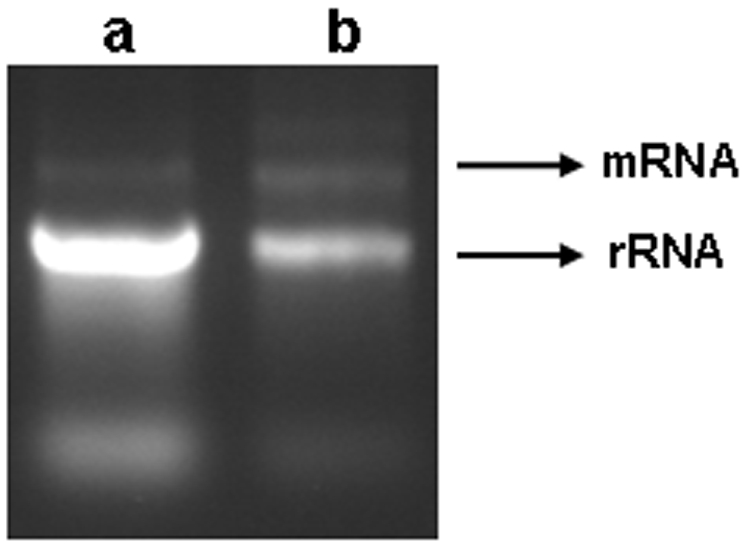

Microarray expression profiling provided evidence of transgenerational spermatogenic inheritance at overall transcriptomic level. To confirm individual gene expression differences, we selected four genes showing upregulation in F2 male microarrays ( Table S1 , supporting material) and assessed their expression using quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Intriguingly, all four genes showed downregulation in RT-PCR ( Fig. 5a ). To investigate the discrepancy, we selected eight genes which were not differentially expressed in F2 male microarrays ( Table S1 , supporting material) and analyzed their expression using RT-PCR. Unexpectedly, these genes in general also showed downregulation ( Fig. 5b ). One possible explanation of this finding could have been that the endogenous control used in RT-PCR, 18S rRNA, may itself be upregulated in F2. Most remarkably, comparison of total RNA isolated from heads of control F2 and F2 adult males with history of PTZ exposure in F0 showed higher abundance of rRNA in the latter ( Fig. 6 ). This result was surprising. Synthesis of rRNA is known to be upregulated by enriched nutritional conditions [32]. Remarkably, all three genes encoding yolk proteins in D. melanogaster, Yp1, Yp2 and Yp3, used for nutritional purpose, were among the total 16 upregulated genes in F2 male CNS ( Table S1 , supporting material). These three genes together represented the most significantly enriched biological process, vitellogenesis, in these males ( Table S2 , supporting material). Considering that Yp1, Yp2 and Yp3 are female specific genes [33], it was interesting to note their expression in males.

Figure 5. Validation of microarrays using RT-PCR.

Genes were either upregulated (a) or not differentially regulated (b) in F2 male microarrays. Equal amount of F2 male RNA samples from all the four biological replicates used in microarray experiment represented in Figure 1 were pooled together for use in RT-PCR. Fold-change values are plotted on y-axis. Note general downregulation of gene expression in RT-PCR.

Figure 6. Electrophoretic analysis of F2 male CNS total cellular RNA.

Equal amount of F2 male RNA samples from all the four biological replicates used in microarray experiment represented in Figure 1 were pooled together for electrophoretic analysis. Note higher amount of rRNA in experimental flies (a) compared to control (b).

Discussion

We have shown here that exposure of a neuroactive compound to adult Drosophila males causes gene expression alteration in CNS of not only the individuals exposed but also their future generations. The genes affected reveal statistically significant overlap across generations. Further, gene expression in adult gonads also shows alterations across generations. The affected genes in testis show some overlap with those in CNS. Transcriptomic similarity thus provides credible evidence that drug induced gene expression alterations leaks to future generations through gametes. Interestingly, we also find that drug exposure causes abnormal expression of rRNA in grandsons of exposed individuals.

Notwithstanding its Lamarckian flavor, transgenerational spermatogenic inheritance has been detected in our search. To our knowledge, this is the first evidence of gametogenic inheritance of adult male acquired somatic characteristic across generations. Given this, our fly model offers an excellent opportunity to further dissect mechanisms underlying the epigenetic inheritance involved. Notably, the model can readily be used as a simple means to test agents for their potential in causing transgenerational effects or erasure thereof. For example, differential expression of rRNA in F2 generation may be used as a rapid screen to test agents producing or modifying transgenerational effects.

Although it is difficult to predict the exact mechanism of epigenetic inheritance observed, involvement of some kind of nervous system-gametogenesis connectivity may possibly be hypothesized. It is interesting to speculate here, for example, a role of neuropeptides as a connecting link. These peptides regulate most, if not all, biological processes across animal species including Drosophila and humans [34]. Neuropeptides are expressed by neurosecretary cells and may be released into the circulatory system to act as neurohormones [35]. Neuropeptides and their receptors are known to express in germ cells [36], [37]. Neuropeptide mediated synaptic plasticity is known to involve regulation of gene expression and chromatin structure [38]. It is tempting to speculate that inheritance of gene expression alteration induced by brain plasticity interfering drugs is mediated by epigenetic changes in the gametes caused through some kind of nervous system- spermatogenesis axis. Alternatively, a direct effect of environmental agents on gametogenesis, besides CNS, may also be possible.

The evidence that gene expression phenotype acquired by an adult can be transmitted to future generations has obvious implications in human health and evolution. Recent epidemiological evidence supports existence of sex-specific, male line transgenerational responses in humans [39]. The experimental evidence presented here warrants systematic investigations to examine if epigenetic inheritance of environmentally induced characteristics exists in man. A topical example to underscore the necessity of such efforts is the ongoing debate whether the use of cognitive enhancement drugs by normal healthy individuals is ethical [40]. Evidence supporting transgenerational inheritance of effects produced by these drugs would compel the present argumentation in a radically new direction.

Materials and Methods

Fly handling and drug treatment

Unless mentioned otherwise, previously described materials and methods were used [27]. In brief, standard fly medium consisting of agar-agar, maize powder, brown sugar, dried yeast and nipagin was used. An isogenic line of D. melanogaster Oregon-R strain was used. Standard methods of fly handling and manipulation were followed. Final concentration of PTZ (Sigma-Aldrich) in the fly medium was 8 mg/ml. Unmated males were first treated with PTZ for seven days and then crossed with virgin females in groups seven days after withdrawing PTZ, to obtain F1. Unmated males and virgin females of F1 generation were collected separately. The F1 males were crossed to normally grown females, without any history of PTZ exposure in earlier generation, in groups to obtain F2 progeny. Unmated males and virgin females of F2 generation were collected separately. For use as control in expression analysis, flies were treated with vehicle (water) instead of PTZ in parallel.

Microarrays

Unless mentioned otherwise, previously described materials and methods were used [27]. In brief, total RNA was isolated from frozen fly heads or testis using TRI REAGENT (Sigma), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Microarray -cDNA Synthesis Kit, -Target Purification Kit, and -RNA Target Synthesis Kit (Roche) were used to generate labeled antisense RNA. Four biological replicates, with balanced dye-swap, were used for generating expression profiles. Each replicate compared experimental versus control flies. The hybridization mixture was denatured at 65°C and applied onto cDNA microarray slides (14Kv1, CDMC, Canada). Analyzable spots in at least three of four biological replicates performed were retrieved for downstream analysis using SAM 3.0 (Excel Add-In) [41]. Wherever absent in the fourth replicate, the values were imputed using SAM. For cluster analysis, all four values in the entire set were used. City Block similarity metric and average linkage methods were used for hierarchical clustering of arrays. The cluster was generated using Acuity 4.0 (Molecular Devices). For identifying differentially expressed genes, both false discovery rate (FDR) in SAM and fold change (FC) in Acuity were used separately. Previously, microarray profiling using the same methods used here identified reported no gene as differentially expressed below 96% FDR [27]. In the present SAM analysis, genes were considered differentially expressed if found within 20% FDR in SAM. For FC analysis, equal or more than 1.3 FC was used for all profiles except F1 testis where 1.2 was used instead of 1.3. Significant match was found between SAM and FC sets of differentially expressed genes. As number of differentially expressed genes identified by either method was smaller, both sets were combined together for further analysis. As differentially expressed genes matched significantly between two replicates of F1 male profiles, the two sets were combined together for further analysis. GOTool Box [42] was used to retrieve overrepresented biological processes in up- or down- regulated genes, under the settings, ontology, biological process; mode, all terms; reference, genome; evidence, all-all evidence; species, D. melanogaster; GO-stats; statistic test, hypergeometric, Bonferroni adjustment. Hypergeometric distribution probabilities for matching of differentially expressed genes between profiles were calculated assuming population sizes of 12000, approximately the number of unique genes in the microarrays. The full microarray data set has been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession series GSE15136.

Real-Time PCR

Equal amount of RNA samples from all the four biological replicates used in microarray experiment were pooled together for use in RT-PCR. Unless mentioned otherwise, previously described materials and methods were used [27]. In brief, RT-PCR amplification reactions were carried out in an ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). ABI gene expression assay IDs used were Dm02151842_g1, Dm01813277_g1, Dm01813506_g1, Dm01813276_g1, Dm02152877_s1, Dm03420546_m1, Dm02361408_s1, Dm02367441_s1, Dm02149362_m1, Dm01825573_m1, Dm02140334_g1 and Dm01828736_m1, for Anp, Yp1, Yp3, Yp2, Acp98, Scp1, Mlp84B, CG6409, Tm1, Rfabg, Cyp313a1 and wupA, in that order.

Gel electrophoresis

Equal amount of RNA samples from all the four biological replicates used in microarray experiment were pooled together for electrophoretic analysis. Standard methods of RNA agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining were followed.

Supporting Information

Differentially expressed genes in CNS. Up- and down-regulated genes in F1 and F2 male and female CNS are listed. Except F1 male, each set of genes were identified using four biological microarray replicates with balanced dye-swaps. In F1 males, an additional batch of four microarrays were generated. Differentially expressed genes identified using each batch showed significant overlap and were therefore pooled together. See text for further details.

(0.30 MB XLS)

Enriched biological processes in differentially expressed genes in CNS. Gene lists provided in Table S1 were used in enrichment analysis. GOTool Box was used to retrieve overrepresented biological processes in up- or down- regulated genes. See text for further details.

(0.13 MB XLS)

Differentially expressed genes in testis. Up- and down-regulated genes in individulas exposed to PTZ (F0) and F1 male are listed. Each set of genes was identified using four biological microarray replicates with balanced dye-swaps. See text for further details.

(0.03 MB XLS)

Enriched biological processes in differentially expressed genes in testis. Gene lists provided in Table S3 were used in enrichment analysis. GOTool Box was used to retrieve overrepresented biological processes in up- or down- regulated genes. See text for further details.

(0.03 MB XLS)

Acknowledgments

We thank Sudhanshu Sharma for providing dissected Drosophila testis used in the experiments described here.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: The research was funded by NWP0034 grant of Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Government of India. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Senior Research Fellowship to P.S. from CSIR is duly acknowledged.

References

- 1.Li E. Chromatin modification and epigenetic reprogramming in mammalian development. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;3:662–673. doi: 10.1038/nrg887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jirtle RL, Skinner MK. Environmental epigenomics and disease susceptibility. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:253–262. doi: 10.1038/nrg2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skinner MK, Anway MD, Savenkova MI, Gore AC, Crews D. Transgenerational epigenetic programming of the brain transcriptome and anxiety behavior. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3745. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang YH, Bressler J, Beaudet AL. Epigenetics and human disease. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2004;5:479–510. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.5.061903.180014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egger G, Liang G, Aparicio A, Jones PA. Epigenetics in human disease and prospects for epigenetic therapy. Nature. 2004;429:457–463. doi: 10.1038/nature02625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weaver IC, Cervoni N, Champagne FA, D'Alessio AC, Sharma S, et al. Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:847–854. doi: 10.1038/nn1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waterland RA, Jirtle RL. Transposable elements: targets for early nutritional effects on epigenetic gene regulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5293–5300. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5293-5300.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dolinoy DC, Weidman JR, Waterland RA, Jirtle RL. Maternal genistein alters coat color and protects Avy mouse offspring from obesity by modifying the fetal epigenome. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:567–572. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weaver IC, Champagne FA, Brown SE, Dymov S, Sharma S, et al. Reversal of maternal programming of stress responses in adult offspring through methyl supplementation: altering epigenetic marking later in life. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11045–11054. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3652-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anway MD, Skinner MK. Epigenetic transgenerational actions of endocrine disruptors. Endocrinology. 2006;147:S43–S49. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morgan HD, Sutherland HG, Martin DI, Whitelaw E. Epigenetic inheritance at the agouti locus in the mouse. Nat Genet. 1999;23:314–318. doi: 10.1038/15490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rakyan VK, Chong S, Champ ME, Cuthbert PC, Morgan HD, et al. Transgenerational inheritance of epigenetic states at the murine Axin(Fu) allele occurs after maternal and paternal transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2538–2543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0436776100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anway MD, Cupp AS, Uzumcu M, Skinner MK. Epigenetic transgenerational actions of endocrine disruptors and male fertility. Science. 2005;308:1466–1469. doi: 10.1126/science.1108190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skinner MK. What is an epigenetic transgenerational phenotype? F3 or F2. Reprod Toxicol. 2008;25:2–6. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitelaw NC, Whitelaw E. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in health and disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flanagan JM, Popendikyte V, Pozdniakovaite N, Sobolev M, Assadzadeh A, et al. Intra- and interindividual epigenetic variation in human germ cells. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:67–84. doi: 10.1086/504729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Durcova-Hills G, Hajkova P, Sullivan S, Barton S, Surani MA, et al. Influence of sex chromosome constitution on the genomic imprinting of germ cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11184–11188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602621103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allegrucci C, Thurston A, Lucas E, Young L. Epigenetics and the germline. Reproduction. 2005;129:137–149. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trasler JM. Origin and roles of genomic methylation patterns in male germ cells. Semin. Cell Dev Biol. 1998;9:467–474. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1998.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCarrey JR, Geyer CB, Yoshioka H. Epigenetic regulation of testis-specific gene expression. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1061:226–242. doi: 10.1196/annals.1336.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Association for Cancer Research Human Epigenome Task Force; European Union, Network of Excellence, Scientific Advisory Board. Moving AHEAD with an international human epigenome project. Nature. 2008;454:711–715. doi: 10.1038/454711a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rongo C, Broihier HT, Moore L, Van Doren M, Forbes A, et al. Germ plasm assembly and germ cell migration in Drosophila. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1997;62:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doren MV, Mathews WR, Samuels M, Moore LA, Broihier HT, et al. Fear of intimacy encodes a novel transmembrane protein required for gonad morphogenesis in Drosophila. Development. 2003;130:2355–2364. doi: 10.1242/dev.00454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jayaramaiah RS, Renkawitz-Pohl R. Replacement by Drosophila melanogaster protamines and Mst77F of histones during chromatin condensation in late spermatids and role of sesame in the removal of these proteins from the male pronucleus. Molec Cell Biol. 2005;25:6165–6177. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.6165-6177.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castrillon DH, Gönczy P, Alexander S, Rawson R, Eberhart CG, et al. Toward a molecular genetic analysis of spermatogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster: characterization of male-sterile mutants generated by single P element mutagenesis. Genetics. 1993;135:489–505. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.2.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gräff J, Mansuy IM. Epigenetic codes in cognition and behaviour. Behav Brain Res. 2008;192:70–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohammad F, Singh P, Sharma A. A Drosophila systems model of pentylenetetrazole induced locomotor plasticity responsive to antiepileptic drugs. BMC Syst Biol. 2009;3:11. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-3-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anway MD, Skinner MK. Transgenerational effects of the endocrine disruptor vinclozolin on the prostate transcriptome and adult onset disease. Prostate. 2008;68:517–29. doi: 10.1002/pros.20724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anway MD, Rekow SS, Skinner MK. Transgenerational epigenetic programming of the embryonic testis transcriptome. Genomics. 2008;91:30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chong S, Whitelaw E. Epigenetic germline inheritance. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14:692–696. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Terry NA, Tulina N, Matunis E, DiNardo S. Novel regulators revealed by profiling Drosophila testis stem cells within their niche. Dev Biol. 2006;294:246–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grummt I, Ladurner AG. A metabolic throttle regulates the epigenetic state of rDNA. Cell. 2008;133:577–580. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bownes M, Scott A, Blair M. The use of an inhibitor of protein synthesis to investigate the roles of ecdysteroids and sex-determination genes on the expression of the genes encoding the Drosophila yolk proteins. Development. 1987;101:931–941. doi: 10.1242/dev.101.4.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baggerman G, Cerstiaens A, De Loof A, Schoofs L. Peptidomics of the larval Drosophila melanogaster central nervous system. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40368–40374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206257200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hewes RS, Snowdeal EC, Saitoe M, Taghert PH. Functional redundancy of FMRFamide-related peptides at the Drosophila larval neuromuscular junction. J Neurosci. 1998;18:7138–7151. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-18-07138.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoshikawa K, Aizawa T. Enkephalin precursor gene expression in postmeiotic germ cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;151:664–671. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)80332-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Darboux I, Lingueglia E, Champigny G, Coscoy S, Barbry P, et al. dGNaC1, a gonad-specific amiloride-sensitive Na+ channel. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9424–9429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guan Z, Giustetto M, Lomvardas S, Kim JH, Miniaci MC, et al. Integration of long-term-memory-related synaptic plasticity involves bidirectional regulation of gene expression and chromatin structure. Cell. 2002;111:483–493 (2002). doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pembrey ME, Bygren LO, Kaati G, Edvinsson S, Northstone K, et al. Sex-specific, male-line transgenerational responses in humans. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:159–166. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greely H, Sahakian B, Harris J, Kessler RC, Gazzaniga M, et al. Towards responsible use of cognitive-enhancing drugs by the healthy. Nature. 2008;456:702–705. doi: 10.1038/456702a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dennis G, Jr, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang J, Gao W, et al. DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4:P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Differentially expressed genes in CNS. Up- and down-regulated genes in F1 and F2 male and female CNS are listed. Except F1 male, each set of genes were identified using four biological microarray replicates with balanced dye-swaps. In F1 males, an additional batch of four microarrays were generated. Differentially expressed genes identified using each batch showed significant overlap and were therefore pooled together. See text for further details.

(0.30 MB XLS)

Enriched biological processes in differentially expressed genes in CNS. Gene lists provided in Table S1 were used in enrichment analysis. GOTool Box was used to retrieve overrepresented biological processes in up- or down- regulated genes. See text for further details.

(0.13 MB XLS)

Differentially expressed genes in testis. Up- and down-regulated genes in individulas exposed to PTZ (F0) and F1 male are listed. Each set of genes was identified using four biological microarray replicates with balanced dye-swaps. See text for further details.

(0.03 MB XLS)

Enriched biological processes in differentially expressed genes in testis. Gene lists provided in Table S3 were used in enrichment analysis. GOTool Box was used to retrieve overrepresented biological processes in up- or down- regulated genes. See text for further details.

(0.03 MB XLS)