Abstract

The ubiquity of mechanosensitive (MS) channels triggered a search for their functional homologs in Archaea. Archaeal MS channels were found to share a common ancestral origin with bacterial MS channels of large and small conductance, and sequence homology with several proteins that most likely function as MS ion channels in prokaryotic and eukaryotic cell-walled organisms. Although bacterial and archaeal MS channels differ in conductive and mechanosensitive properties, they share similar gating mechanisms triggered by mechanical force transmitted via the lipid bilayer. In this review, we suggest that MS channels of Archaea can bridge the evolutionary gap between bacterial and eukaryotic MS channels, and that MS channels of Bacteria, Archaea and cell-walled Eukarya may serve similar physiological functions and may have evolved to protect the fragile cellular membranes in these organisms from excessive dilation and rupture upon osmotic challenge.

Keywords: Arabidopsis, mechanosensitivity, phylogeny, yeast

Introduction

Mechanosensory transduction, the process by which mechanical energy exerted on cellular membranes is converted to electrical or biochemical signals, is believed to be one of the oldest physiological processes to have evolved in living organisms. At present, the molecular basis of mechanosensory transduction remains largely elusive despite its biological importance. Gated by mechanical force, mechanosensitive (MS) channels may serve as molecular transducers in various physiological processes including touch, hearing and proprioception in animals, turgor control and gravitaxis in plants, and osmoregulation in prokaryotes (Martinac 1993, Sackin 1995, Sachs and Morris 1998, Hamill and Martinac 2001). The patch-clamp recording technique (Hamill et al. 1981) made it possible to resolve unitary channel events in membranes of cells too small to be impaled with glass microelectrodes. This led to the identification of MS channels as molecular entities (Brehm et al. 1984, Guharay and Sachs 1984) in a variety of microorganisms including yeast (Gustin et al. 1988, Zhou and Kung 1992) and bacteria (Martinac et al. 1987).

Compared with voltage-dependent or ligand-gated channels, there is little knowledge available on the structure and function of, and the mutual relationships among, the wide range of MS channels found in living organisms. During the last decade, however, major progress has been made in the understanding of the biophysical principles and evolutionary origins of mechanosensory transduction by cloning and structural and functional characterization of several MS channels found in bacterial and archaeal cells (Hamill and Martinac 2001, Martinac 2001). In addition, it has recently been shown that bacterial and archaeal MS channels form a family of mechanosensitive membrane proteins descended from a common ancestor (Kloda and Martinac 2001a). The aim of this review is to summarize this recent progress and show that a familial relationship established for MS channels in prokaryotes can be extended further to some eukaryotic organisms that, like bacteria and archaea, evolved a rigid cell wall to protect their plasma membrane from excessive strain.

Mechanosensitive channels in prokaryotic cells

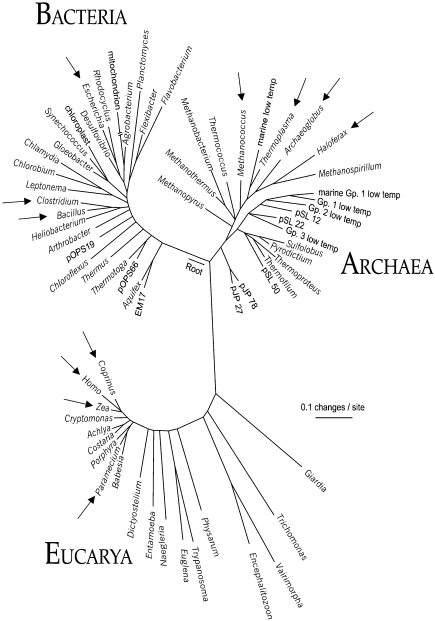

Mechanosensitive channels have been studied extensively in both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria (Martinac et al. 1992, Martinac 1993, 2001, Zoratti and Ghazi 1993, Blount et al. 1999). The existence of MS channels in the cell membranes of Archaea (formerly Archaebacteria), the third domain of the universal phylogenetic tree (Figure 1) (Woese 1994, Pace 1997), was first documented in the archaeon Haloferax volcanii (formerly Halobacterium volcanii) (Le Dain et al. 1998), followed by the cloning and functional characterization of MS channels in Methanococcus jannaschii and Thermoplasma sp. (Kloda and Martinac 2001a, 2001b, 2001c). The existence of MS channels in archaeal and bacterial cell membranes suggests that this class of ion channels may have appeared early in the evolution of life on Earth (Martinac 2001).

Figure 1.

Universal phylogenetic tree based on small subunit rRNA sequences (modified from Pace 1997, with permission). Organisms in each of the three domains in which MS channel activities have been documented by structure or function are marked with arrows.

Structure and function of bacterial MS channels

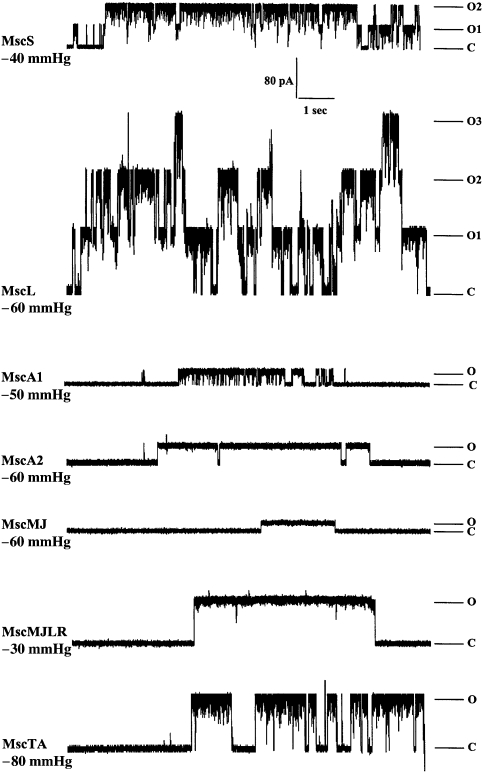

To date, the most detailed characterization of MS channels has been completed in Escherichia coli. This microbe harbors three distinct types of MS channels, named after their conductance and sensitivity to applied pressure: MscM (M for mini), MscS (S for small) and MscL (L for large) (Berrier et al. 1996) (Figures 2 and 3). The larger the conductance, the higher the membrane tension and consequently the higher the energy required for channel activation (Figure 4, Table 1). Provided that the geometric and electrical properties of the patch pipettes are kept constant, the free energy of activation (ΔG0) for an MS channel can be estimated as (Hamill and Martinac 2001):

Figure 2.

Multiplicity of MS channels in bacteria and archaea. Current traces (pA) of Escherichia coli MscL and MscS are followed by traces of MscA1 and MscA2 of Haloferax volcanii and MscMJ and MscMJLR of Methanococcus jannaschii. The bottom trace shows the activity of MscTA, the MS channel of Thermoplasma acidophilum. Single channel currents were recorded at +40 mV. Abbreviations: C denotes the closed state; O denotes the open state; and O1, O2 and O3 denote the open state of 1, 2 and 3 channels, respectively. Note: 1 mmHg = 133 Pa.

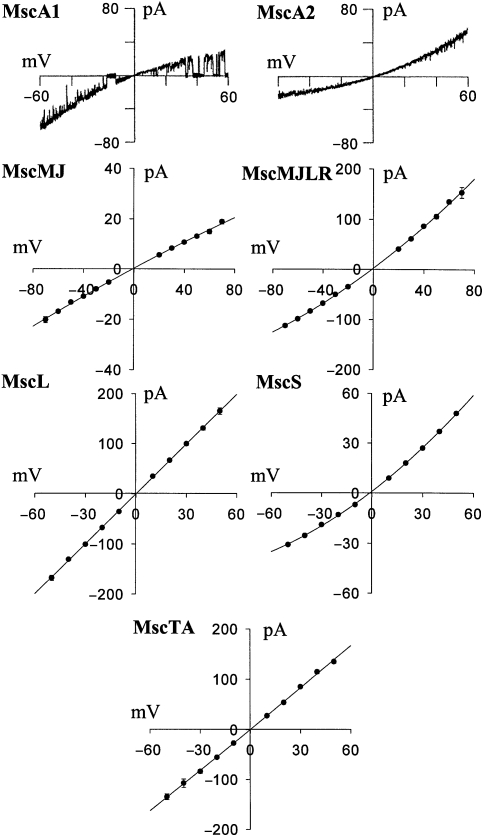

Figure 3.

Comparison of conductive properties of bacterial and archaeal MS channels. From top to bottom: MscA1 and MscA2 of Haloferax volcanii (adapted from Le Dain et al. 1998); MscMJ and MscMJLR of Methanococcus jannaschii (adapted from Kloda and Martinac 2001b); MscL and MscS of Escherichia coli; and MscTA of Thermoplasma acidophilum (adapted from Kloda and Martinac 2001c). Current–voltage plots were obtained in a symmetric recording solution of 200 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, from data where the voltage was stepped to the given potential, except for the MscA1 and MscA2 single-channel currents, which were obtained for a voltage ramp from –60 to +60 mV over 2.6 and 1.7 s, respectively.

Figure 4.

Boltzmann distribution curves for MS channels in prokaryotes. (A) MscS and MscL of Escherichia coli; based on Martinac (unpublished data) and Kloda and Martinac (2001d). (B) MscA1 and MscA2 of Haloferax volcanii; adapted from LeDain et al. (1998). (C) MscMJ and MscMJLR of Methanococcus jannaschii; adapted from Kloda and Martinac (2001a, 2001b). (D) MscTA of Thermoplasma acidophilum; based on Kloda and Martinac (2001c). The Boltzmann function for MS channels relates applied negative pressure and open probability (Po) fitted by nonlinear regression and has the form: Po/(1 – Po) = exp(α(p – p1/2)), where p1/2 is the pressure required for a channel open probability of 50% and α is the slope of the plot of ln(Po/(1 – Po)) versus negative pressure and describes the pressure sensitivity of the channels in the particular patch. Values for Boltzmann parameters are given in Table 1. Note: 1 mmHg = 133 Pa.

Table 1.

Summary of the Boltzmann characteristics and conductive properties for the known prokaryotic MS channels. The parameter values shown were compiled from data cited in the references listed. The conductive and mechanosensitive properties of these channels are further illustrated in Figures 3 and 4 (adapted from Kloda and Martinac 2001d). The diameter of the open channel pore was calculated according to a model proposed by Hille (1968) (Cruickshank et al. 1997). Note: 1 mmHg = 133 Pa.

| MS Channel | p1/2 (mmHg) | 1/α (mmHg) | DG0 (kT) | Conductance (nS) | Diameterpore (Å) | References |

| MscL | 75 | 4. 4–5 | 1 4–19 | 3. 3–3.8 | 35 | Häse et al. 1995 |

| Sukharev et al. 1999 | ||||||

| Kloda and Martinac 2001c, 2001d | ||||||

| MscS | 36 | 5 | 7 | 0.97 (+ve) | 18 | Martinac et al. 1987 |

| 0.65 (–ve) | Martinac (unpublished) | |||||

| Kloda and Martinac 2001d | ||||||

| MscA1 | 34 | 2.3 | 15 | 0.38 (+ve) | 11 | LeDain et al. 1998 |

| 0.68 (–ve) | ||||||

| MscA2 | 43 | 1.5 | 29 | 0.85 (+ve) | 17 | LeDain et al. 1998 |

| 0.49 (–ve) | ||||||

| MscMJ | 57 | 11 | 5 | 0.27 | 9 | Kloda and Martinac 2001a |

| MscMJLR | 29 | 1.7 | 17 | 2.2 (+ve) | 27 | Kloda and Martinac 2001b |

| 1.7 (–ve) | ||||||

| MscTA | 78 | 2.4 | 35 | 2.8 | Kloda and Martinac 2001c, 2001d | |

where α is MS channel pressure sensitivity (mmHg–1) (1 mmHg = 133 Pa), p1/2 is the pressure required for a channel open probability of 50% (Po = 0.5) (mmHg), k is the Boltzmann constant and T is absolute temperature. Estimates of ΔG0 for MS channels characterized to date in various prokaryotic cells are shown in Table 1.

Bacterial MS channels were the first shown to sense directly membrane tension caused by external mechanical force (Martinac et al. 1990, Markin and Martinac 1991). Furthermore, the lipid bilayer alone suffices to transmit membrane tension, leading to channel gating. The role of bilayer tension in the gating mechanism (Hamill and McBride 1997) has been well documented for MS channels in bacteria (Martinac et al. 1990, Sukharev et al. 1993, 1994a, 1994b, 1999, Häse et al. 1995, Cruickshank et al. 1997) as well as in archaea (Le Dain et al. 1998, Kloda and Martinac 2001a, 2001b, 2001c). It has been shown recently that eukaryotic MS ion channels can also be gated by bilayer tension (Zhang et al. 2000). This suggests that gating of MS channels by mechanical force may have first evolved in cell-walled microorganisms and then been conserved in cells of higher eukaryotes (Hamill and Martinac 2001).

The large conductance MS channel of E. coli (MscL) was the first MS channel to be identified at the molecular level (Sukharev et al. 1994a, 1994b). Activation of MscL by bilayer tension enabled individual fractions collected during the purification of the protein from E. coli to be assayed for MS channel activity by the patch-clamp technique (Sukharev et al. 1994a, 1994b). Since the discovery of MscL, many homologous genes have been found in various gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, as well as in the cyanobacterium Synaechocystis sp. (Sukharev et al. 1997, Moe et al. 1998).

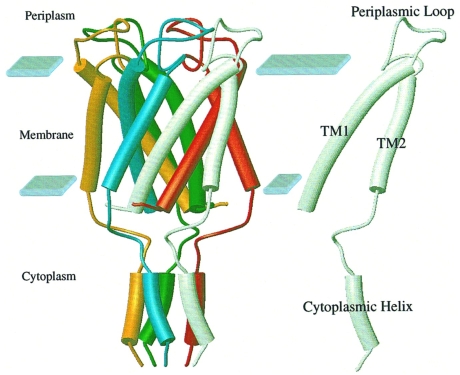

The MscL protein comprises 136 amino acid residues. A hydropathy plot combined with secondary structure analysis indicated that the MscL monomer has two transmembrane α-helical domains (Sukharev et al. 1997, Oakley et al. 1999). An MscL-like structural motif of two transmembrane hydrophobic segments was found in a group of eukaryotic ion channels including the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC), the inward-rectifier potassium channel (Kir) and the ATP-gated (P2X) cation channel (North 1996). A three-dimensional oligomeric structure determination of the MscL homolog from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Tb-MscL) by X-ray crystallography to 3.5-Å resolution showed that the channel is a homopentamer (Chang et al. 1998) (Figure 5). These crystal structures revealed a transmembrane pore that ranges between 4 and 36 Å in diameter at the cytoplasmic and extracellular surfaces, respectively (Figure 5). Recent cysteine-scanning mutagenesis and electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy provided complementary structural information about the conformation of the closed MscL channel (Perozo et al. 2001). Electrophysiological permeation studies, in which the open MscL channel pore was estimated to be about 40 Å in diameter by measuring permeation of large organic cations, such as polyamines and polylysines (Cruickshank et al. 1997), indicated that the structure of the open MscL channel must be quite different from that of the closed one. Consequently, a major structural rearrangement is to be expected when MscL gates between the closed and open conformational states (Batiza et al. 1999).

Figure 5.

Diagram of the MscL pentamer from Mycobacterium tuberculosis according to the three-dimensional structural model proposed by Chang et al. (1998). The pentamer (left) and a single monomer (right) are shown. The transmembrane helices TM1 and TM2 are labeled. Solid blocks denote the location of the membrane interface with the periplasmic and cytoplasmic spaces. This figure was produced by MolScript (Avatar Software, Stockholm, Sweden; Kraulis 1991) (adapted from Oakley et al. 1999).

Experiments with MscL reconstituted in liposome bilayers of different thicknesses indicated that hydrophobic mismatch between MscL and the surrounding bilayer led to a change in the ΔG0 of MscL, such that thinner bilayers caused a decrease, whereas thicker bilayers caused an increase in ΔG0 (Kloda and Martinac 2001c). Therefore, MscL mechanosensitivity (Hamill and Martinac 2001), and possibly that of other mechanosensitive membrane proteins, resulted from stretch-induced bilayer thinning, which stabilizes the open conformation of MscL because of a better hydrophobic match between the membrane and the open channel conformation compared with the closed channel conformation. Similar experiments carried out with the MS channel of the thermophilic archaeon Thermoplasma acidophilum (MscTA) showed that the activity of this MS channel also varied with lipid bilayer thickness (Kloda and Martinac 2001c). These results seem to be in excellent agreement with a molecular dynamics study of MscL gating showing that the transmembrane helices flattened as the channel opened (Gullingsrud et al. 2001). Furthermore, recently proposed three-dimensional structural models of two MscL homologs from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and E. coli postulated flattening of the MscL helices during opening of the channels (Sukharev et al. 2001a, 2001b), in accordance with the notion that thin bilayers provide a better hydrophobic match for the open channel conformation than for the closed channel conformation.

The physiological function of bacterial MS channels can be correlated with their molecular and electrophysiological properties. It has been demonstrated that bacteria exposed to osmotic downshock preserve viability by rapidly releasing their cytoplasmic contents into the extracellular medium (Britten and McClure 1962, Koo et al. 1991, Schleyer et al. 1993). In addition, Berrier et al. (1992) demonstrated that osmotically induced efflux of lactose and ATP from E. coli, as well as ATP from Streptococcus faecalis, could be blocked by Gd3+, a known blocker of bacterial MS channels. Independent investigations (Blount et al. 1996a, Häse et al. 1997) associated MscL activity with the inner cytoplasmic membrane of E. coli, a strategic position for the efflux of osmoprotectants. Two other types of E. coli MS channels, MscS and MscM, can be activated by differences in osmotic pressure in patch-clamp experiments (Martinac et al. 1992, Cui et al. 1995). Together, these results suggest a physiological role for MS channels in bacterial osmoregulation.

The small and mini conductance MS channels of E. coli (MscS and MscM, respectively) require less negative pressure for activation than MscL, in order of their decreasing conductance (Berrier et al. 1996). The MS channel of small conductance was the first MS channel identified in prokaryotic cells (Martinac et al. 1987). The membrane tension required to open MscS is about half that needed to open MscL (Blount et al. 1996b, Sukharev et al. 1997), and the conductance of the channel is about 1 nS (Figure 3) (Martinac et al. 1987, Sukharev et al. 1993). In contrast to MscL and MscM, MscS exhibits a voltage dependence of about 15 mV per e-fold change in the channel open probability (Martinac et al. 1987), and its activity increases with membrane depolarization. Such a response to voltage could be seen as a modulation of channel activity by the lipid bilayer, rather than voltage dependence, because of changes in membrane thickness during voltage-induced electrocompression (Alvarez and Latorre 1978, Hamill and Martinac 2001). The MscS channel is largely nonselective for most ions, although it exhibits a slight preference for anions over cations, with a permeability ratio PCl/PK ≈ 3 (Martinac et al. 1987, Sukharev et al. 1993). Like MscL, MscS is blocked by sub-millimolar concentrations of Gd3+ (Berrier et al. 1992).

Recently, Booth and coworkers (Booth and Louis 1999, Levina et al. 1999) identified two genes on the E. coli chromosome, yggB and kefA, whose deletion abolished MscS activity in bacterial spheroplasts. The gene product YggB is a small membrane protein of 286 amino acids, whereas KefA is about five times larger (1120 amino acids) and is a multimeric membrane protein. The primary amino acid sequence of YggB strongly resembles that of the last two domains of the KefA protein.

The activity of MscM is encountered less frequently in membrane patches of giant E. coli spheroplasts than MscS or MscL activity (Cui et al. 1995, Berrier et al. 1996). The conductance of MscM is about half that of MscS, and MscM exhibits a slight preference for cations over anions (Berrier et al. 1989), in contrast to MscS and MscL. Like MscS and MscL, MscM is blocked by Gd3+ (Berrier et al. 1992). Because all three channels can be activated by hypotonic solutions, they could all provide efflux pathways for various osmoprotectants in osmotically challenged bacteria (Ghazi et al. 1998). Booth and colleagues (Levina et al. 1999) provided compelling evidence for the role of MS channels in bacterial osmoregulation by showing that the presence of either MscS or MscL is essential to preserve the integrity of E. coli cells exposed to sudden change in medium osmolarity. When challenged osmotically, deletion mutants lacking either MscL or MscS alone survive osmotic downshock. Double mutants, however, which lack both MscL and MscS, die on transfer from a medium of high to a medium of low osmolarity, suggesting that the third channel, MscM, is not sufficient to protect bacteria from lysis following osmotic downshock. These physiological responses provide evidence that the bacterial MS channels function as safety valves that protect the cells from bursting at transient, excessively high, cellular turgors.

Structure and function of archaeal MS channels

Archaea are unicellular prokaryotes that, like bacteria, have adapted to the extreme environments of certain habitats found on Earth (Barinaga 1994). They constitute a separate domain on the phylogenetic tree distinct from the domains of Bacteria and Eukarya (Figure 1) (Woese 1994, Pace 1997). The existence of ion channels in archaeal cell membranes was first documented with the discovery of porins (Besnard et al. 1997) and MS channels (Le Dain et al. 1998) in the halophilic archaeon Haloferax volcanii. This was followed by molecular identification and functional characterization of MS channels in methanogenic Methanococcus jannaschii and thermophilic Thermoplasma volcanium and Thermoplasma acidophilum (Kloda and Martinac 2001a, 2001b, 2001c).

Two types of MS channels have been identified in the cell membrane of H. volcanii (Le Dain et al. 1998) (Figure 2): MscA1 and MscA2, (mechanosensitive channels of archaea). Both have large conductances and rectify with voltage (Figure 3). Both are blocked by sub-millimolar concentrations of Gd3+, like the bacterial MS channels. The major property that they share with the bacterial MS channels is their activation by bilayer tension (Hamill and McBride 1997). Like bacterial MS channels, they can be solubilized by detergents and reconstituted into artificial liposomes while fully preserving their mechanosensitivity as observed in patch-clamp experiments. These channels exhibit a higher sensitivity to pressure (1.4–2.9 mmHg per e-fold change in open probability) (Le Dain et al. 1998) than MscL or MscS (approximately 5 mmHg per e-fold change) (Häse et al. 1995) (Table 1, Figure 4). The free energy of activation of MscA1 and MscA2, calculated from Equation 1, is about 14 and 29 kT, respectively (Table 1). Like MscS and MscL, which have ΔG0 values of 7 and 14–19 kT, respectively (Table 1), changes in cellular turgor may also activate the archaeal channels.

Recently, protein MJ0170 in the Methanococcus jannaschii genome (Bult et al. 1996) was found to contain a sequence that shares 38.5% identity with the TM1 transmembrane domain of E. coli MscL. This led to its functional characterization as an MS channel named MscMJ (Kloda and Martinac 2001a). The primary amino acid sequence of MscMJ also shares high homology with YggB, the protein underlying the activity of MscS in E. coli (Levina et al. 1999). Phylogenetic analysis of the MscMJ protein suggested that it evolved from a gene duplication event, followed by divergence of the mscL-like ancestral gene, which appears to be a common progenitor of bacterial and archaeal MS channels (Kloda and Martinac 2001a, Figure 6A). The MscMJ protein exhibits MS channel activity, with a conductance of 270 pS and cation selectivity characterized by PK/PCl ≈ 6, similar to eukaryotic stretch-activated cationic channels (SA-CAT) (Hamill and McBride 1996). The channel’s ΔG0, ≈ 5 kT, is comparable with the MscS value of ~7 kT. Thus, MscMJ is biophysically closer to MscS than to MscL (Table 1). Like MscS (Martinac et al. 1990), MscMJ can be activated by the amphipaths chlorpromazine (CPZ) and trinitrophenol (TNP) (Kloda and Martinac 2001a).

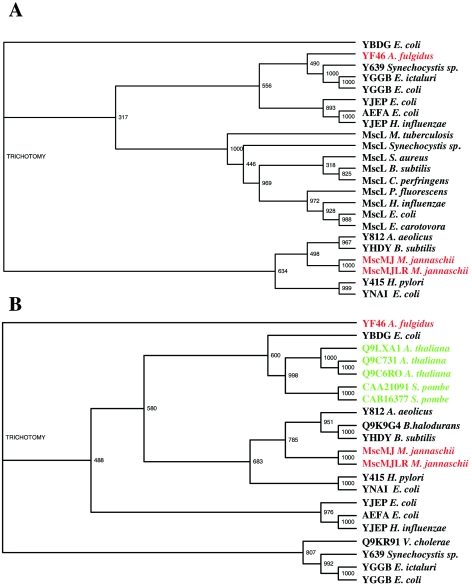

Figure 6.

(A) Phylogenetic tree of complete aligned sequences of MscL and MscMJ homologs showing the common ancestry of prokaryotic MS channels. The archaeal homologs of MscMJ are highlighted in red. (B) Phylogenetic tree of complete aligned sequences of MscMJ and MscMJLR homologs showing the family relationship between bacterial and archaeal MS channels, and putative MS channels in A. thaliana and S. pombe. The bacterial MS channel homologs of MscMJ and MscMJLR are depicted in black; archaeal MS homologs are highlighted in red; and plant and yeast homologs are highlighted in green. The TM1 domain of E. coli MscL was used as a genetic probe to search the M. jannaschii genomic database for sequence similarity, leading to identification of MscMJ. Homologs of MscMJ and MscL were retrieved from the existing protein databases (GenBank, Protein DataBank and SwissProt) using BLAST (Altschul et al. 1997). Multiple alignment of entire sequences was performed using the CLUSTAL X program (Thompson et al. 1997). The phylogenetic trees of prokaryotic MscL and MscMJ-like homologs are shown to ensure the best sequence alignment of known and hypothetical MS channel proteins. Note that there are common members in both trees, suggesting a common ancestry. Bootstrap Neighbor-Joining Trees with 1000 bootstrap trials each were viewed with the TreeView program. Bootstrap values are given on the branch nodes.

Soon after the molecular characterization of MscMJ, a second MS channel, MscMJLR, was identified in M. jannaschii and functionally characterized (Kloda and Martinac 2001b) (Figure 2). Like MscMJ, MscMJLR shares sequence homology with an extensive group of MscS-like proteins identified in prokaryotic microbes, as well as the eukaryotic herbaceous plant Arabidopsis thaliana and the yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Figure 6B). Many members of this group belong to a yet uncharacterized protein family, UPF0003, identified by Pfam (Sonnhammer et al. 1997, 1998). Like MscS and MscL of E. coli, MscMJ and MscMJLR differ in conductive and mechanosensitive properties. Although MscMJLR is cation selective, with a permeability ratio PK/PCl ≈ 5 (close to PK/PC1 ≈ 6 of MscMJ), it has a large conductance of ~2.0 nS, which is about seven times larger than that of MscMJ (270 pS; see Figure 3). The MscMJLR protein is blocked by Gd3+, but is unaffected by the amphipaths CPZ and TNP, which are known activators of eukaryotic and prokaryotic MS channels (Martinac et al. 1990, Sokabe et al. 1993, Hamill and McBride 1996, Patel et al. 1998, Kloda and Martinac 2001a). The free energy of activation for MscMJLR (ΔG0 ≈ 18 kT) estimated from the Boltzmann distribution function (Figure 4) is similar to the value of 14–19 kT for MscL in E. coli (Table 1). The hydrophobic profile of the first putative membrane-spanning domain (TM1) of MscMJLR more closely resembles the TM1 of MscL, which is the helix essential for the opening of the MscL pore by membrane tension (Yoshimura et al. 1999, Ajouz et al. 2000), than that of MscMJ (Figure 7). If the TM1 helix of MscMJ also lines the MscMJ channel pore, its more hydrophilic character compared with that of the MscMJLR TM1 helix (Figure 7) may underlie the much lower energy requirement (~5 kT) necessary to activate MscMJ compared with MscMJLR or MscL. In fact, the free energy required for activation of MscL approximates well the calculated energy required to expose a small hydrophobic surface area of the TM1 helices functioning as a channel gate to the ionic environment (Hamill and Martinac 2001). The presence of multiple MS channels in microbial cells indicates that they may be necessary for survival in environments with frequent osmotic challenges.

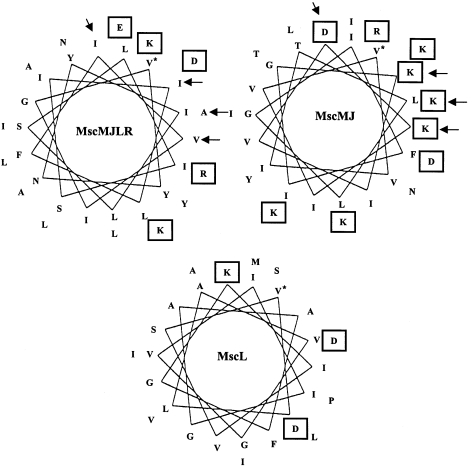

Figure 7.

Helical wheel representation of the TM1 domains of MscMJLR and MscMJ from Methanococcus jannaschii and of MscL from Escherichia coli. Charged residues are boxed and the start of each helix is marked with an asterisk. Arrows indicate positions at which hydrophobic residues within the TM1 helix of MscMJLR are replaced with hydrophilic (charged) residues in the MscMJ helix. Note that the TM1 domains of MscMJ and MscMJLR are hypothetical. Adapted from Kloda and Martinac (2001b).

The MS channel of T. volcanium is a 15-kDa membrane protein with a single-channel conductance of about 1.5 nS (Kloda and Martinac 2001c). It was identified by a functional approach similar to that used for molecular identification of MscL (Sukharev et al. 1994a, 1994b). Like MscS of E. coli (Martinac et al. 1990), or mammalian TREK-1 K+ MS channels (Patel et al. 1998), the T. volcanii channel exhibits an increase in activation by negative pressure in the presence of the anionic amphipath TNP. Twenty N-terminal amino acid residues of this MS protein match with 75% identity the start of the open reading frame of a gene of the related archaeon Thermoplasma acidophilum that encodes another MS protein, MscTA (Kloda and Martinac 2001c). Computer-assisted secondary structure analysis of MscTA revealed two putative α-helical membrane-spanning regions, suggesting possible structural similarity to MscL. Like all currently known prokaryotic MS channels, the mechanosensitivity of MscTA complies with the bilayer model (Martinac et al. 1990, Hamill and McBride 1997); i.e., mechanical force transmitted via the lipid bilayer suffices to activate the channel. The free energy necessary for channel activation (ΔG0 ≥ 35 kT) is, however, unusually high compared with other bacterial and archaeal MS channels (Table 1). A possible reason for such a high activation energy may be that unusually short transmembrane helices result in a hydrophobic mismatch between the MscTA helices and the surrounding bilayer that exceeds that for MscL (Kloda and Martinac 2001c). High negative pressures are also required for the activation of MscL homologs found in Synechocystis sp. and M. tuberculosis (Moe et al. 1998, 2000).

Phylogeny of prokaryotic MS channels

The finding that MS channels exist in organisms from all three domains of the phylogenetic tree (Figure 1) points toward an early evolutionary origin. Several authors have suggested that MS channels function as cellular osmoregulators by protecting cells from excessive osmotic stress occasionally exerted on their cytoplasmic membranes (Sachs 1988, Kung et al. 1990, Morris 1990, Martinac 1993, Kung and Saimi 1995, Sackin 1995). That the MS channels of Bacteria and Archaea have large conductances and generally lack ion specificity supports the view that they are involved in regulation of cellular turgor. This was unambiguously demonstrated for MscL and MscS of E. coli (Blount et al. 1997, Ou et al. 1997, Ajouz et al. 1998, Levina et al. 1999) and also indicated for MscMJ of M. jannaschii (Kloda and Martinac 2001a). The finding that MS channels of prokaryotes descend from a common MscL-like ancestor (Kloda and Martinac 2001a) (Figure 6A) provides further support for the notion of a common early evolutionary origin.

Phylogeny of MS channels in Bacteria, Archaea and cell-walled Eukarya

It was realized that the MS channels identified in archaea may be used as a stepping stone to trace the MscL-like ancestry to some of the eukaryotic MS ion channel genes. Therefore, MscMJ and MscMJLR were used as templates to extend our search for new members of the MS channel family into the eukaryotic domain. Comparative protein sequence analysis (BLAST) revealed that MscMJ and MscMJLR share sequence homology with the hypothetical proteins of the herbaceous plant A. thaliana (i.e., Q9LXA1, Q9C731 and Q9C6RO) and the yeast S. pombe (CAA21091 and CAB16377) (Figure 6B). Based on these findings, it is likely that these eukaryotic hypothetical proteins also function as MS channels and regulate turgor pressure in these organisms. It is satisfying to find homologs of prokaryotic channels in the eukaryotic domain because organisms that harbor them have all evolved a cell wall to protect the fragile lipid bilayer of their cytoplasmic membranes from excessive dilation and rupture. Thus, in the case of MS channels, Nature may have preserved homologous structures to perform similar functions.

Conclusions

Mechanosensitive ion channels have been documented in major cell types and show great diversity in terms of conductance, selectivity and voltage dependence, while sharing the property of gating by mechanical force exerted on cell membranes. Their discovery in archaea provided new insights into the phylogeny of these important membrane proteins; first by helping to identify the evolutionary relationship between bacterial and archaeal MS channels; and currently showing that this relationship extends into the domain of eukaryotic cells.

References

- R1.Ajouz B., Berrier C., Garrigues A., Besnard M., Ghazi A. Release of thioredoxin via mechanosensitive channel MscL during osmotic downshock of Escherichia coli cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:26670–26674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R2.Ajouz B., Berrier C., Besnard M., Martinac B., Ghazi A. Contributions of the different extramembraneous domains of the mechanosensitive ion channel MscL to its response to membrane tension. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:1015–1022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R3.Altschul S.F., Madden T., Schaffer A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R4.Alvarez O., Latorre R. Voltage-dependent capacitance in liquid bilayers made from monolayers. Biophys. J. 1978;21:1–17. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(78)85505-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R5.Barinaga M. Molecular evolution. Archaea and eukaryotes grow closer. Science. 1994;264:1251. doi: 10.1126/science.8191278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R6.Batiza A.F., Rayment I., Kung C. Channel gate! Tension, leak and disclosure. Structure. 1999;7:R99–R103. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R7.Berrier C., Coulombe A., Houssin C., Ghazi A. A patch-clamp study of inner and outer membranes and of contact zones of E. coli, fused into giant liposomes. Pressure-activated channels are localized in the inner membrane. FEBS Lett. 1989;259:27–32. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81486-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R8.Berrier C., Coulombe A., Szabo I., Zoratti M., Ghazi A. Gadolinium ion inhibits loss of metabolites induced by osmotic shock and large stretch-activated channels in bacteria. Eur. J. Biochem. 1992;206:559–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R9.Berrier C., Besnard M., Ajouz B., Coulombe A., Ghazi A. Multiple mechanosensitive ion channels from Escherichia coli, activated at different thresholds of applied pressure. J. Membr. Biol. 1996;151:175–187. doi: 10.1007/s002329900068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R10.Besnard M., Martinac B., Ghazi A. Voltage-dependent porin-like ion channels in the archaeon Haloferax volcanii . J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:992–995. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R11.Blount P., Sukharev S.I., Moe P., Schroeder M.J., Guy H.R., Kung C. Membrane topology and multimeric structure of a mechanosensitive channel protein of Escherichia coli . EMBO J. 1996;15:101–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R12.Blount P., Sukharev S.I., Schroeder M.J., Nagle S.K., Kung C. Single residue substitutions that change gating properties of a mechanosensitive channel in Escherichia coli . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:11652–11657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R13.Blount P., Schroeder M., Kung C. Mutations in a bacterial mechanosensitive channel change the cellular response to osmotic stress. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:32150–32157. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R14.Blount P., Sukharev S.I., Moe P., Martinac B., Kung C. Mechanosensitive channels in bacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1999;294:458–482. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)94027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R15.Booth I.R., Louis P. Managing hypoosmotic stress: aquaporins and mechanosensitive channels in Escherichia coli . Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 1999;2:166–169. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)80029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R16.Brehm P., Kullberg R., Moody-Corbet F. Properties of non-junctional acetylcholine receptor channels on innervated muscle of Xenopus laevis . J. Physiol. 1984;350:631–648. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R17.Britten R.J., McClure F.T. The amino acid pool of Escherichia coli . Bacteriol. Rev. 1962;26:292–335. doi: 10.1128/br.26.3.292-335.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R18.Bult C.J., White O., Olsen G.J, et al. Complete genome sequence of the methanogenic Archaeon, Methanococcus jannaschii . Science. 1996;273:1058–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R19.Chang G., Spencer R., Lee A., Barclay M., Rees C. Structure of the MscL homologue from Mycobacterium tuberculosis: A gated mechanosensitive ion channel. Science. 1998;282:2220–2226. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R20.Cruickshank C., Minchin R., Ledain A., Martinac B. Estimation of the pore size of the large-conductance mechanosensitive ion channel of Escherichia coli . Biophys. J. 1997;73:1925–1931. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78223-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R21.Cui C., Smith D.O., Adler J. Characterization of mechanosensitive channels in Escherichia coli cytoplasmic membrane by whole-cell patch-clamp recording. J. Membr. Biol. 1995;144:310–342. doi: 10.1007/BF00238414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R22.Ghazi A., Berrier C., Ajouz B., Besnard M. Mechanosensitive ion channels and their mode of activation. Biochimie. 1998;80:357–362. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(00)80003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R23.Guharay F., Sachs F. Stretch-activated single ion channel currents in tissue cultured embryonic chick skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 1984;352:685–701. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R24.Gullingsrud J., Kostin D., Schulten K. Structural determinants of MscL gating studied by molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys. J. 2001;80:2074–2081. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76181-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R25.Gustin M.C., Zhou X.L., Martinac B., Kung C. A mechanosensitive ion channel in the yeast plasma membrane. Science. 1988;242:762–765. doi: 10.1126/science.2460920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R26.Hamill O.P., Martinac B. Molecular basis of mechanotransduction in living cells. Physiol. Rev. 2001;81:685–740. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R27.Hamill O.P., McBride D.W. The pharmacology of mechanogated membrane ion channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 1996;48:231–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R28.Hamill O.P., McBride D.W. Induced membrane hypo/hyper-mechanosensitivity: a limitation of patch-clamp recording. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1997;59:621–631. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R29.Hamill O.P., Marty A., Neher E., Sakmann B., Sigworth F.J. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflueg. Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R30.Hille B. Pharmacological modification of the sodium channels of frog nerve. J. Gen. Physiol. 1968;51:199–219. doi: 10.1085/jgp.51.2.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R31.Häse C.C., Ledain A.C., Martinac B. Purification and functional reconstitution of the recombinant large mechanosensitive ion channel (MscL) of Escherichia coli . J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:18329–18334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.31.18329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R32.Häse C.C., Minchin R.F., Kloda A., Martinac B. Cross-linking studies and membrane localization and assembly of radiolabelled large mechanosensitive ion channel (MscL) of Escherichia coli . Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;232:777–782. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R33.Kloda A., Martinac B. Molecular identification of a mechanosensitive ion channel in archaea. Biophys. J. 2001;80:229–240. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76009-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R34.Kloda A., Martinac B. Structural and functional similarities and differences between MscMJLR and MscMJ, the two homologous MS channels of M. jannaschii . EMBO J. 2001;20:1888–1896. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.8.1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R35.Kloda A., Martinac B. Mechanosensitive channel in Thermoplasma a cell wall-less archaea: cloning and molecular characterization. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2001;34:321–347. doi: 10.1385/CBB:34:3:321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R36.Kloda A., Martinac B. Mechanosensitive channels of bacteria and archaea share a common ancestral origin. Eur. Biophys. J. 2001 doi: 10.1007/s002490100160. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R37.Koo S.P., Higgins S.F., Booth I.R. Regulation of compatible solute accumulation in Salmonella typhimurium: evidence for glycine betaine efflux system. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1991;137:2617–2625. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-11-2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R38.Kraulis P.J. MOLSCRIPT: A program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1991;24:946–950. [Google Scholar]

- R39.Kung C., Saimi Y. Solute sensing vs. solvent sensing, a speculation. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 1995;42:199–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1995.tb01564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R40.Kung C., Saimi Y., Martinac B. Mechanosensitive ion channels in microbes and the early evolutionary origin of solvent sensing. In: Claudio T., editor. Current Topics in Membranes and Transport. New York: Vol. 36. Academic Press; 1990. pp. 9451–9455. [Google Scholar]

- R41.Le Dain A.C., Saint N., Kloda A., Ghazi A., Martinac B. Mechanosensitive ion channels of the archaeon Haloferax volcanii . J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:12116–12119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R42.Levina N., Totemeyer S., Stokes N.R., Louis P., Jones M.A., Booth I.R. Protection of Escherichia coli cells against extreme turgor by activation of MscS and MscL mechanosensitive channels: identification of genes required for MscS activity. EMBO J. 1999;18:1730–1737. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.7.1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R43.Markin V.S., Martinac B. Mechanosensitive ion channels as reporters of bilayer expansion. A theoretical model. Biophys. J. 1991;60:1120–1127. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82147-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R44.Martinac B. Mechanosensitive ion channels: biophysics and physiology. In: Jackson M.B., editor. Thermodynamics of Membrane Receptors and Channels. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1993. pp. 327–351. [Google Scholar]

- R45.Martinac B. Mechanosensitive channels in prokaryotes. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2001;11:61–76. doi: 10.1159/000047793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R46.Martinac B., Buechner M., Delcour A.H., Adler J., Kung C. Pressure-sensitive ion channel in Escherichia coli . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:2297–2301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.8.2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R47.Martinac B., Adler J., Kung C. Mechanosensitive ion channels of E. coli activated by amphipaths. Nature. 1990;348:261–263. doi: 10.1038/348261a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R48.Martinac B., Delcour A.H., Buechner M., Adler J., Kung C. Mechanosensitive ion channels in bacteria. In: Ito F., editor. Comparative Aspects of Mechanoreceptor Systems. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 1992. pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- R49.Moe P.C., Blount P., Kung C. Functional and structural conservation in the mechanosensitive channel MscL implicates elements crucial for mechanosensation. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;28:583–592. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R50.Moe P.C., Levin G., Blount P. Correlating a protein structure with function of a bacterial mechanosensitive channel. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:31121–31127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002971200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R51.Morris C.E. Mechanosensitive ion channels. J. Membr. Biol. 1990;113:93–107. doi: 10.1007/BF01872883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R52.North R.A. Families of ion channels with two hydrophobic segments. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1996;8:474–483. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R53.Oakley A.J., Martinac B., Wilce M.C.J. Structure and function of the bacterial mechanosensitive channel of large conductance. Protein Sci. 1999;8:1915–1921. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.10.1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R54.Ou X., Blount P., Hoffman R., Kusano A., Kung C. Random mutagenesis of a mechanosensitive channel identifies regions of the protein crucial for normal function. Biophys. J. 1997;72:A139. [Google Scholar]

- R55.Pace N.R. A molecular view of microbial diversity and the biosphere. Science. 1997;276:734–740. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R56.Patel A., Honoré E., Maingret F., Lesage F., Fink M., Duprat F., Lazdunski M. A mammalian two pore domain mechano-gated S-like K+ channel. EMBO J. 1998;17:4283–4290. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.15.4283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R57.Perozo E., Kloda A., Cortes D.M., Martinac B. Site-directed spin-labeling analysis of reconstituted MscL in the closed state. J. Gen. Physiol. 2001;118:193–205. doi: 10.1085/jgp.118.2.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R58.Sachs F. Mechanical transduction in biological systems. Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 1988;16:141–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R59.Sachs F., Morris C.E. Mechanosensitive ion channels in nonspecialized cells. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1998;132:1–77. doi: 10.1007/BFb0004985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R60.Sackin H. Mechanosensitive channels. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1995;57:333–353. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.002001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R61.Schleyer M., Schmid R., Bakker E.P. Transient, specific and extremely rapid release of osmolytes from growing cells of Escherichia coli . Arch. Microbiol. 1993;160:424–431. doi: 10.1007/BF00245302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R62.Sokabe M., Hasegawa N., Yamamori K. Blockers and activators for stretch-activated ion channels of chick skeletal muscle. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1993;707:417–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb38086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R63.Sonnhammer E.L., Eddy S.R., Durbin R. Pfam: A comprehensive database of protein families based on seed alignments. Proteins. 1997;28:405–420. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(199707)28:3<405::aid-prot10>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R64.Sonnhammer E.L., Eddy S.R., Birney E., Bateman A., Durbin R. Pfam: multiple sequence alignments and HMW-profiles of protein domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:320–322. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.1.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R65.Sukharev S.I., Martinac B., Arshavsky V.Y., Kung C. Two types of mechanosenitive channels in the E. coli cell envelope: solubilization and functional reconstitution. Biophys. J. 1993;65:177–183. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81044-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R66.Sukharev S.I., Blount P., Martinac B., Blattner F.R., Kung C. A large mechanosensitive channel in E. coli encoded by mscL alone. Nature. 1994;368:265–268. doi: 10.1038/368265a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R67.Sukharev S.I., Blount P., Martinac B., Kung C. Functional reconstitution as an assay for biochemical isolation of channel proteins: application to the molecular identification of a bacterial mechanosensitive channel. Methods: A Companion to Methods in Enzymol. 1994;6:51–59. [Google Scholar]

- R68.Sukharev S.I., Blount P., Martinac B., Kung C. Mechanosensitive channels of Escherichiacoli: the MscL gene, protein, and activities. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1997;59:633–657. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R69.Sukharev S.I., Sigurdson W.J., Kung C., Sachs F. Energetic and spatial parameters for gating of the bacterial large conductance mechanosensitive channel, MscL. J. Gen. Physiol. 1999;113:525–539. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.4.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R70.Sukharev S.I., Betanzos M., Chiang C.-S., Guy H.R. The gating mechanism of the large mechanosensitive channel MscL. Nature. 2001;409:720–724. doi: 10.1038/35055559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R71.Sukharev S.I., Durell S.R., Guy H.R. Structural models of the MscL gating mechanism. Biophys. J. 2001;81:917–936. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75751-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R72.Thompson J.D., Gibson T.J., Plewniak F., Jeanmougin F., Higgins D.G. The Clustal X window interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;24:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R73.Woese C.R. There must be a prokaryote somewhere: microbiology’s search for itself. Microbiol. Rev. 1994;58:1–9. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.1.1-9.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R74.Yoshimura K., Batiza A., Schroeder M., Blount P., Kung C. Hydrophilicity of a single residue within MscL correlates with increased channel mechanosensitivity. Biophys. J. 1999;77:1960–1972. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77037-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R75.Zhang Y., Gao G., Popov V.L., Wen J.W., Hamill O.P. Mechanically gated channel activity in cytoskeleton deficient plasma membrane blebs and vesicles from Xenopus oocytes. J. Physiol. 2000;523:117–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00117.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R76.Zhou X.L., Kung C. A mechanosensitive channel in Schizosaccharomycespombe . EMBO J. 1992;11:2869–2875. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05355.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R77.Zoratti M., Ghazi A. Stretch-activated channels in prokaryotes. In: Bakker E.P., editor. Alkali Transport Systems in Prokaryotes. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1993. pp. 349–358. [Google Scholar]