Abstract

A highly efficient method for chromosomal integration of cloned DNA into Methanosarcina spp. was developed utilizing the site-specific recombination system from the Streptomyces phage φC31. Host strains expressing the φC31 integrase gene and carrying an appropriate recombination site can be transformed with non-replicating plasmids carrying the complementary recombination site at efficiencies similar to those obtained with self-replicating vectors. We have also constructed a series of hybrid promoters that combine the highly expressed M. barkeri PmcrB promoter with binding sites for the tetracycline-responsive, bacterial TetR protein. These promoters are tightly regulated by the presence or absence of tetracycline in strains that express the tetR gene. The hybrid promoters can be used in genetic experiments to test gene essentiality by placing a gene of interest under their control. Thus, growth of strains with tetR-regulated essential genes becomes tetracycline-dependent. A series of plasmid vectors that utilize the site-specific recombination system for construction of reporter gene fusions and for tetracycline regulated expression of cloned genes are reported. These vectors were used to test the efficiency of translation at a variety of start codons. Fusions using an ATG start site were the most active, whereas those using GTG and TTG were approximately one half or one fourth as active, respectively. The CTG fusion was 95% less active than the ATG fusion.

Keywords: genetics, site-specific recombination, tetR, essential gene

Introduction

Methanoarchaea are a unique group of organisms that are responsible for the vast majority of biologically mediated methane production. Methanogenesis plays a critical role in the carbon cycle, global warming, alternative energy strategies, waste treatment and agriculture, but the experimental study of methanoarchaea is laborious. They are oxygen-sensitive anaerobes and, until recently, methods for their genetic manipulation were scarce. However, this has begun to change, in particular for members of the genus Methanosarcina (reviewed in Sowers and Schreier (1999) and Rother and Metcalf (2005)). Although, these developments have substantially improved the genetic malleability of Methanosarcina, the pace of genetic studies is frustratingly slow and certain types of experiments remain difficult, in particular those requiring stable insertion of cloned DNA into the chromosome and those requiring stringent regulation of gene expression.

Cloned DNA can be introduced into Methanosarcina spp. with autonomously replicating plasmid vectors (Metcalf et al. 1997); however, this approach often introduces experimental artifacts owing to the higher plasmid copy number. For example, we have found that transformation can be difficult, or impossible, with plasmids carrying genes encoding membrane proteins or highly expressed reporter gene fusions. Further, plasmids can be unstable, especially when they encode genes that confer a growth disadvantage (Apolinario et al. 2005). Insertion of the cloned DNA into the chromosome can avoid these problems; however, current methods of cloned DNA insertion for use with Methanosarcina are less efficient by a factor of about 100 than transformation with autonomous plasmids because of their dependence on homologous recombination. In other organisms, methods utilizing site-specific recombination, instead of homologous recombination, have allowed much higher integration efficiencies (e.g., Lyznik et al. 2003, Schweizer 2003, and references therein). One particularly useful site-specific recombinase system utilizes the Streptomyces bacteriophage φC31 integrase (Thorpe and Smith 1998).

The φC31 integrase catalyzes recombination without aid of other proteins (Thorpe and Smith 1998), a feature that has allowed its use in diverse hosts including Streptomyces (Bierman et al. 1992), Escherichia coli (Thorpe and Smith 1998), Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Thomason et al. 2001) and Homo sapiens cell lines (Groth et al. 2000). The site-specific φC31 integration reaction is unidirectional. Many site-specific recombinases, such as the Saccharomyces Flp system (Schweizer 2003, Branda and Dymecki 2004), can be used efficiently to excise a DNA fragment flanked by recombination sites (Schweizer 2003); however, integration is less efficient because the recombinase is fully reversible. Accordingly, the recombinase-encoding gene cannot be constitutively expressed in the recipient because it destabilizes the construct. Use of reversible recombinases, therefore, requires transient expression, whereas a unidirectional recombinase can be expressed constitutively without compromising the stability of the insert, which greatly simplifies strain constructions (Belteki et al. 2003).

Regulated expression of cloned genes in Methanosarcina is problematic because few regulated promoters have been well characterized in members of this genus. In contrast, large numbers of well-characterized and tightly regulated promoters are known in bacteria. These have allowed the development of numerous systems for stringent regulation of cloned genes and for the testing of gene essentiality (Baron and Bujard 2000, Guzman et al. 1995, Lutz and Bujard 1997, Kamionka et al. 2005). Among the most useful of these is the tetracycline-regulated promoter system from the transposon Tn10 (Beck et al. 1982). The Tn10-encoded TetR protein binds specifically to the tetO operator sequence in the absence of tetracycline, thus preventing transcription. However, binding of tetracycline by the TetR protein abrogates binding of the protein to the promoter allowing transcription. This relatively simple system has been combined with a variety of natural and synthetic promoters to create numerous different tetracycline-regulated systems (reviewed in Berens and Hillen (2004) and Sprengel and Hasan (2007)). These include both prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems, ones that act as either Tet-responsive repressors or activators, and ones in which the binding of mutant derivatives of TetR depends on the presence of tetracycline, instead of its absence.

The use of φC31-mediated site-specific recombination and Tet-regulated gene expression has revolutionized genetic analysis, especially in organisms, such as higher eukaryotes, where genetic manipulation has traditionally been both difficult and slow. Given the inherent difficulties of genetic experiments in methanoarchaea, we believed that the development of similar approaches for Methanosarcina species would be especially worthwhile. These efforts are reported below.

Materials and methods

Strains, media and growth conditions

Methanosarcina strains used in the study are described in Table 1. These were grown in single cell morphology (Sowers et al. 1993) at 37 °C in high salt (HS) liquid medium (Metcalf et al. 1996) containing 125 mM methanol, 50 mM trimethylamine (TMA) or 40 mM acetate as indicated. Growth on medium solidified with 1.5% agar was as described by Zhang et al. (2000). All plating manipulations were carried out in an anaerobic glove box (Coy Laboratory Products, Grass Lake, MI). Solid media plates were incubated in an intra-chamber anaerobic incubator as described by Metcalf et al. (1998). Puromycin (CalBiochem, San Diego, CA) was added from sterile, anaerobic stocks at a final concentration of 2 µg ml–1 for selection of Methanosarcina strains carrying the puromycin transacetylase gene (pac). The purine analog 8-aza-2,6-diaminopurine (8-ADP) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was added from sterile, anaerobic stocks at a final concentration of 20 µg ml–1 for selection against the hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase gene (hpt).

Table 1.

Methanosarcina strains used in this study.

| Strain | Genotype | Source/Reference |

| M. acetivorans C2A | Wild type | DSM28341 |

| WWM1 | Δhpt | (Pritchett et al. 2004) |

| WWM19 | Δhpt::pWM357 | (Guss et al. 2005) |

| WWM60 | Δhpt::PmcrB-tetR | This study |

| WWM73 | Δhpt::PmcrB-tetR-φC31-int-attP | This study |

| WWM75 | Δhpt::PmcrB-tetR-φC31-int-attB | This study |

| WWM82 | Δhpt::PmcrB-φC31-int-attP | This study |

| WWM83 | Δhpt::PmcrB-φC31-int-attB | This study |

| M. barkeri Fusaro | Wild type | DSM8041 |

| WWM85 | Δhpt::PmcrB-φC31-int-attP | This study |

| WWM86 | Δhpt::PmcrB-φC31-int-attB | This study |

| WWM155 | Δhpt::PmcrB-tetR-φC31-int-attP | This study |

| WWM154 | Δhpt::PmcrB-tetR-φC31-int-attB | This study |

| WWM235 | Δhpt::PmcrB-tetR-φC31-int-attB, PmcrB(tetO1)::mcrBCDGA | This study |

1Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (Braunschweig, Germany).

Escherichia coli cells were grown under standard conditions (Wanner 1986). Escherichia coli WM3118 (F-, mcrA, Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC), φ80lacZΔM15, ΔlacX74, recA1, endA1, araD139, Δ(ara, leu)7697, galU, galK, rpsL, nupG, λattB::pAMG27(PrhaB-trfA33) was constructed by integration of pAMG27 (Table 2) into the λattB site of DH10B (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) by site-specific recombination as described by Haldimann and Wanner (2001). WM3118 was used as the host strain for all plasmids containing oriV, allowing plasmid copy number to be dramatically increased by growth in a medium containing 10 mM rhamnose before plasmid purification (Wild et al. 2002). BW25141 was the host strain for Π-dependent plasmids (Haldimann and Wanner 2001). DH10B was the host strain for all other plasmids (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Table 2.

Plasmids and primers used in the study.

| Plasmid | Features/Use | Source |

| pAMG27 | lattP CRIM plasmid encoding kanamycin resistance and PrhaB-trfA33 | This study |

| pAMG33 | Fosmid vector encoding chloramphenicol and puromycin resistance with oriV and lattP | This study |

| pAMG40 | E. coli-Methanosarcina shuttle vector for fosmid retrofitting encoding ampicillin resistance and lattB | This study |

| pAMG44 | Fosmid vector encoding chloramphenicol and puromycin resistance with oriV, lattP and fC31-attP | This study |

| pAMG45 | Fosmid vector encoding chloramphenicol and puromycin resistance with oriV, lattP and fC31-attB | This study |

| pAMG63 | Plasmid for markerless insertion of PmcrB-fC31-int-attP into the M. acetivorans hpt locus (used to construct WWM82) | This study |

| pAMG64 | Plasmid for markerless insertion of PmcrB-fC31-int-attB into the M. acetivorans hpt locus (used to construct WWM83) | This study |

| pAMG70 | Plasmid for markerless insertion of PmcrB-fC31-int-attB into the M. barkeri hpt locus (used to construct WWM85) | This study |

| pAMG71 | Plasmid for markerless insertion of PmcrB-fC31-int-attP into the M. barkeri hpt locus (used to construct WWM86) | This study |

| pAMG82 | fC31-attB vector for construction of translational fusions to the E. coli uidA gene using an ATG start codon | This study |

| pAMG83 | fC31-attB vector for construction of translational fusions to the E. coli uidA gene using an GTG start codon | This study |

| pAMG95 | fC31-attB vector for construction of translational fusions to the E. coli uidA gene using an TTG start codon | This study |

| pAMG96 | fC31-attB vector with M. barkeri mcrB promoter fusion to uidA with a GTG start site | This study |

| pAMG103 | fC31-attB vector for construction of translational fusions to the E. coli uidA gene using an CTG start codon | This study |

| pAMG104 | fC31-attB vector with M. barkeri mcrB promoter fusion to uidA with a TTG start site | This study |

| pAMG105 | fC31-attB vector with M. barkeri mcrB promoter fusion to uidA with a CTG start site | This study |

| pAMG108 | fC31-attB vector for construction of translational fusions to the E. coli uidA gene using an AAA start codon | This study |

| pAMG109 | fC31-attB vector with M. barkeri mcrB promoter fusion to uidA with a AAA start site | This study |

| pJK026A | fC31-attB vector with PmcrB promoter fusion to uidA | This study |

| pJK027A | fC31-attB vector with PmcrB(tetO1) promoter fusion to uidA | This study |

| pJK028A | fC31-attB vector with PmcrB(tetO3) promoter fusion to uidA | This study |

| pJK029A | fC31-attB vector with PmcrB(tetO4) promoter fusion to uidA | This study |

| pJK031A | fC31-attP vector with PmcrB(tetO1) promoter fusion to uidA | This study |

| pJK032A | fC31-attP vector with PmcrB(tetO3) promoter fusion to uidA | This study |

| pJK033A | fC31-attP vector with PmcrB(tetO4) promoter fusion to uidA | This study |

| pJK200 | Fosmid vector encoding chloramphenicol and puromycin resistance with oriV, lattP and fC31-attB | This study |

| pWM321 | E. coli/Methanosarcina shuttle vector | (Metcalf et al. 1997) |

| pWM357 | Fosmid cloning vector | (Zhang et al. 2002) |

| pGK50A | Vector for testing gene essentially using PmcrB(tetO1), encodes kanamycin and puromycin resistance | This study |

| pGK51A | Vector for testing gene essentially using PmcrB(tetO3), encodes kanamycin and puromycin resistance | This study |

| pGK52A | Vector for testing gene essentially using PmcrB(tetO4), encodes kanamycin and puromycin resistance | This study |

| pGK50B | Vector for testing gene essentially using PmcrB(tetO1), encodes kanamycin and puromycin resistance, tetR gene is in opposite orientation to pGK50A | This study |

| pGK51B | Vector for testing gene essentially using PmcrB(tetO3), encodes kanamycin and puromycin resistance, tetR gene is in opposite orientation to pGK51A | This study |

| pGK52B | Vector for testing gene essentially using PmcrB(tetO4), encodes kanamycin and puromycin resistance, tetR gene is in opposite orientation to pGK52A | This study |

| pGK90 | pGK050A-derived plasmid used for construction of WWM253 | This study |

| pAB79 | fC31-attB vector with PmcrB(tetO1) fusion to uidA, can be used for construction of either transcriptional or translational fusions | This study |

Transformation methods

Escherichia coli strains were transformed by electroporation using an E. coli Gene Pulser (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) as recommended. Liposome-mediated transformation was used for Methanosarcina as described by Boccazzi et al. (2000).

Plasmids and DNA primers

Plasmids used in the study are described in Table 2. All plasmids were verified by extensive restriction endonuclease digestion analysis and DNA sequencing of selected junction regions (data not shown). Because of the large number of plasmid intermediates constructed during the course of this work, only the final versions used in the study are presented in Table 2. Annotated GenBank-style DNA sequence files for each plasmid are provided in the online supplementary materials. Details of the plasmid constructions are available on request. Standard techniques were used for the isolation and manipulation of plasmid DNA using E. coli hosts (Ausubel et al. 1992).

Molecular genetic methods

Methanosarcina strain constructions via markerless exchange or gene replacement following transformation with linear DNA were according to Zhang et al. (2002) and Pritchett et al. (2004) and were performed in media containing either methanol or TMA as growth substrate. Transformation efficiency was tested in medium containing TMA as growth substrate. Approximately 2 µg of purified DNA was used in each transformation. Retrofitting of plasmids carrying λattB sites with plasmid pAMG40 was performed using BP clonase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. After the in vitro site-specific recombination reaction was complete, the mixture was used to transform WM3118 with selection for chloramphenicol and kanamycin resistance. Co-integration of the plasmids was verified by restriction endonuclease digestion of purified plasmid DNAs.

PCR verification of plasmid integration

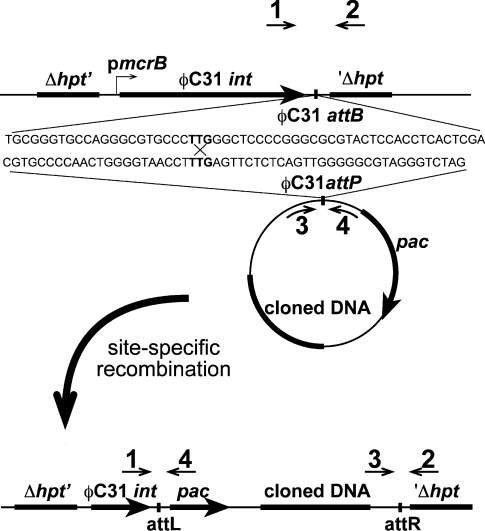

Single copy integration of non-replicating plasmids via φC31 site-specific recombination was verified using a four-primer PCR screen. Template DNA was obtained by resuspending cells from a colony grown on agar-solidified medium in sterile H2O, which causes immediate cell lysis. After a 4 min preincubation at 94 °C, 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 53 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 90 s were performed, followed by a final incubation at 72 °C for 2 min. Methanosarcina acetivorans integrants were screened with C31 screen-all#1 (GAAGCTTCCCCTTGACCAAT, primer #1 in Figure 1), C31 screen-C2A#1 (TTGATTCGGATACCCTGAGC, primer #2 in Figure 1), C31 screen-pJK200#1 (GCAAAGAAAAGCCAGTATGGA, primer #3 in Figure 1), and C31 screen-pJK200#2 (TTTTTCGTCTCAGCCAATCC, primer #4 in Figure 1). Methanosarcina barkeri integrants were screened with C31 screen-all#1 (primer #1 in Figure 1), C31 screen-Fus#1 (CGAACTGTGGTGCAAAAGAC, primer #2 in Figure 1), C31 screen-pJK200#1 (primer #3 in Figure 1), and C31 screen-pJK200#2 (primer #4 in Figure 1). The PCRs were performed using Taq polymerase in Failsafe buffer J (Epicentre, Madison WI). For most of the plasmids described here the expected bands are: parental strain control, 910 bp; plasmid control, 450 bp; single plasmid integrations, 670 and 730 bp; integration of plasmid multimers, 670, 730 and 450 bp. For pAB79-derived plasmids the expected bands are: parental strain control, 910 bp; plasmid control, 510 bp; single plasmid integrations, 679 and 740 bp; integration of plasmid multimers, 680, 741 and 511 bp.

Figure 1.

Scheme of the φC31 integrase-mediated site-specific recombination in Methanosarcina. Strains carrying the φC31 integrase gene (φC31 int) driven by a strong constitutive promotor (PmcrB) and the phage integration site (φC31 attB) inserted into the hpt locus of both Methanosarcina acetivorans and M. barkeri were constructed as described (Table 1). Transformation of these strains to PurR (conferred by the pac gene) with non-replicating plasmids carrying the complementary integration site (φC31 attP) results in highly efficient integration of the plasmid into the host chromosome after site-specific recombination between attB and attP (denoted by X) catalyzed by the Int protein. Δhpt′ and ′Δhpt represent the chromosomal regions flanking the hpt locus, which was deleted upon insertion of the int gene and att sites. attL and attR represent the hybrid recombination sites formed by site specific recombination between attB and attP. The numbered arrows indicate the location of PCR primers used to verify the single-copy insertion of plasmids as described in the methods. Sequences for the screening primers are provided in Table 2.

Extract preparation and β-glucuronidase assay

The preparation of cell extracts and the β-glucuronidase assay method were as previously described (Rother et al. 2005). Enzymatic activity was determined by following production of p-nitrophenol at 415 nm (ε = 12402 mM–1 cm–1). Absorbance spectra were recorded with a Hewlett Packard 8453 diode array spectrophotometer. Activity is reported in milliunits (mU; 1 nmol min–1). Strains were adapted to each growth substrate for at least 15 generations before measurement. Reported values are means of at least three separate cultures. Protein concentration was determined by the method of Bradford (Bradford 1976), with bovine serum albumin as the standard. The limit of detection for β-glucuronidase is 0.4 mU mg protein–1.

Results

Construction of strains and plasmids for site-specific integration of cloned DNA into the Methanosarcina chromosome

A strategy for highly efficient insertion of cloned DNA fragments into the Methanosarcina chromosome utilizing the well-characterized Streptomyces φC31 phage integrase system is shown in Figure 1. In this system, non-replicating plasmids carrying either the attB or attP recombination sites are used to transform strains carrying the complementary recombination site and a constitutively expressed φC31 integrase (int) gene. Site-specific recombination between the attB and attP sequences results in highly efficient integration of the plasmid into the host chromosome.

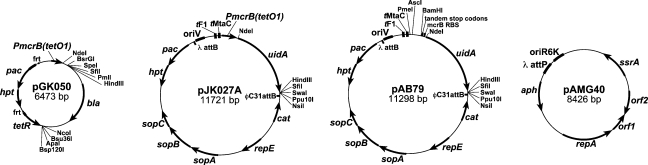

To achieve this goal, we constructed a series of M. barkeri and M. acetivorans strains that carry either attB or attP and the φC31 integrase gene expressed from the constitutive PmcrB promoter of M. barkeri (Rother et al. 2005) (Table 1). A series of complementary plasmids was also constructed (Table 2, Figure 2). Several of these plasmids are derivatives of the fosmid cloning vector pWM357 (Zhang et al. 2002) and are useful for constructing genomic DNA libraries; however, they have been modified to include additional useful features. The parental plasmid was modified to include a marker for selection of puromycin resistance in Methanosarcina species and the origin of replication from plasmid RP4 (oriV) to allow induction of high-copy replication in appropriate host strains (Wild et al. 2002). The plasmids also carry the phage λ attB site, which can be used to retrofit the plasmids with additional features (see below).

Figure 2.

Structure of representative plasmids. Plasmids of the pGK050 series can be used to construct strains with Tet-dependent expression of Methanosarcina genes by “knocking in” a PmcrB(tetO) promoter at the normal chromosomal location of a gene of interest. To do this an appropriate region of homology upstream of the promoter to be deleted is cloned into one of the sites adjacent to tetR, while the gene of interest is cloned downstream of the PmcrB(tetO) promoter. Use of the NdeI site (CATATG) allows construction of in-frame translational fusions to the PmcrB(tetO) promoter (the underlined ATG within the NdeI site comprises the start codon of mcrB). Plasmids of the pJK027A series can integrate into the chromosome by φC31 site-specific recombination and are useful for construction of either translational uidA reporter gene fusions (by replacement of PmcrB(tetO) with a promoter of interest) or fusions of a gene of interest to a Tet-regulated promoter (by replacement of uidA with a gene of interest). Again, the NdeI site allows construction of in-frame translational fusions. Plasmid pAB79 can also integrate into the chromosome by φC31 site-specific recombination, but can be used to create either transcriptional or translational fusions to uidA. By cloning promoters of interest into the BamHI site, one can maintain the mcrB ribosome-binding-site (RBS) to allow efficient translation initiation of uidA; thus, expression of the reporter gene fusion is dependent only on transcription initiating within the cloned segment. Tandem translation stop codons are maintained in this case to prevent translational readthrough into the reporter gene. Alternatively, one can maintain the RBS from the gene of interest by cloning into the NdeI site, thus creating a translational fusion that requires both transcriptional and translational signals to be present in the cloned fragment. Plasmid pAMG40 carries the entire pC2A plasmid from M. acetivorans and is capable of autonomous replication in Methanosarcina. It can be used to retrofit non-replicating plasmids such as pAB79 or the pJK027A series by site-specific recombination between λattB and λattP. The resulting plasmid co-integrants are capable of autonomous replication in either E. coli or Methanosarcina. Additional plasmids similar to the ones shown here are presented in Table 2. Acronyms: bla, β-lactamase gene encoding ampicillin resistance; tetR, gene for the tetracycline-resposive repressor protein from Tn10; hpt, gene for hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase; pac, puromycin acetyltransferase gene encoding resistance to puromycin; FRT, recognition site for the Flp site-specific recombinase; uidA, gene encoding β-glucuronidase; cat, chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene encoding resistance to chloramphenicol; repE, gene encoding the replication initiation protein from the E. coli F plasmid; sopA, sopB and sopC, genes encoding the plasmid partitioning system of the E. coli F plasmid; λattP and λattB, the recognition sites for the phage λ Int site-specific recombinase; tF1 and tMtaC, putative transcriptional terminators from the E. coli phage F1 and M. acetivorans mtaCB1 operon, respectively.

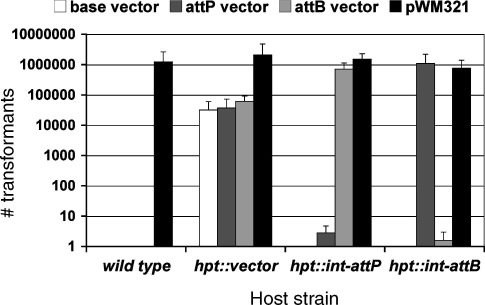

Efficiency of plasmid integration via the φC31 integrase system

We tested the efficiency of the φC31 integrase system in a series of transformation experiments (Figure 3). The self-replicating vector pWM321 yielded approximately 106 puromycin-resistant (PurR) transformants in each of the strains examined. Non-replicating attB and attP fosmids gave nearly as many transformants as pWM321, but only when the transformation involved the complementary attP and attB hosts (i.e., attB plasmids transformed into attP strains and vice versa). When fosmids were introduced into strains carrying identical att sites (i.e. attB x attB and attP x attP), less than ten transformants arose. Fosmids lacking a φC31 att site were incapable of transforming either φC31-int strain. These data suggest that φC31 site-specific recombination can occur in Methanosarcina at efficiencies that approach transformation by autonomous vectors. To compare the efficiency of site-specific recombination with the efficiency of homologous recombination, we transformed a control strain carrying an 8 kb region of homology to the fosmid backbone inserted into the chromosomal hpt locus. In this strain, non-replicating fosmids produced approximately 30-fold lower transformation efficiencies regardless of the presence or absence of φC31 att sites. No recombinants were obtained in wild-type strains after transformation with any of the non-replicating vectors.

Figure 3.

Transformation efficiencies in Methanosarcina using the φC31 integrase-mediated integration. Various Methanosarcina strains were transformed to PurR with 2 µg of the indicated plasmid DNA and the number of colonies obtained was quantified. The presence of φC31 Int recombination sites (attB or attP) are indicated. Results shown are means of least three trials. Host strains used were WWM1 (wild-type), WWM19 (hpt::vector), WWM73 (hpt::int-attP) and WWM75 (hpt::int-attB). Plasmids used were pAMG18 (base vector), pAMG44 (attP vector), pAMG45 (attB vector) and pWM321 (autonomous plasmid vector).

Integration vectors for facile construction of uidA reporter gene fusions

We have found the φC31 integration system to be particularly useful in gene regulation studies using reporter gene fusions, where stably maintained, single-copy fusions are desirable. To facilitate such studies, we constructed a series of φC31 integration plasmids to allow construction of transcriptional and translational fusions to uidA gene from E. coli, which encodes β-glucuronidase (GUS), a useful reporter system in Methanosarcina (Pritchett et al. 2004) (Figure 2).

We used these constructs to examine the effects of alternative start codons on translational efficiency in Methanosarcina. Plasmids with the highly expressed mcrB promoter (PmcrB) fused to uidA using ATG, GTG, TTG, CTG, and AAA as translation initiation codons were constructed and integrated into the M. acetivorans chromosome in single copy. Using methanol as a growth substrate, β-glucuronidase activity was similar when the start codon was ATG or GTG (2034 ± 348 mU mg–1 and 1593 ± 495 mU mg–1, respectively), whereas changing the start site to TTG reduced activity by two-thirds (559 ± 200 mU mg–1). When CTG was the start site, activity was reduced by a factor of about 20 compared to ATG (79 ± 19 mU mg–1). Mutation of the start site to AAA resulted in complete elimination of β-glucuronidase activity (< 0.4 mU mg–1).

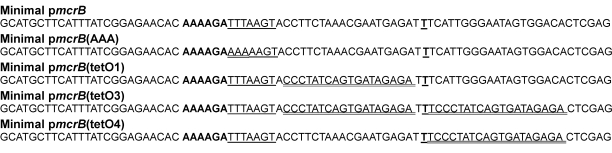

Construction of tetracycline-regulated promoters for use in Methanosarcina

To develop a Tet-regulated gene expression system for Methanosarcina, we constructed a series of plasmids in which PmcrB was modified to include binding sites for the Tn10-derived TetR protein (tetO) (Figure 4). Four promoters with variable placement of the tetO operator were constructed, designated PmcrB(tetO1), PmcrB(tetO2), PmcrB(tetO3) and PmcrB(tetO4). The PmcrB(AAA) promoter, which has a three-base-pair mutation that eliminates the TATA box, was also constructed to demonstrate that transcription was being driven solely by PmcrB. Host strains that constitutively express the Tn10 tetR gene from the wild-type mcrB promoter were constructed to allow regulated expression from these hybrid promoters (Table 1). Some strains also carry the φC31-attB or φC31-attP site, along with an artificial operon that expresses both tetR and the φC31 int gene from the PmcrB promoter, to allow insertion of plasmids into the chromosome as described above.

Figure 4.

Nucleotide sequence of the mcrB promoter and mutated derivatives. The nucleotide sequence of the minimal mcrB promoter from Methanosarcina barkeri is shown on the top line. The putative BRE is shown in bold text, the putative TATA box is underlined and the experimentally verified transcription start site (Allmansberger et al. 1989) is underlined in bold text. The following lines show the mutated derivatives that were modified to include the tetR-binding site (double underlined) at various positions within the promoter.

To test the system, we fused each hybrid promoter to uidA and integrated the resulting plasmids into the M. acetivorans chromosome in single copy via site-specific recombination. We then measured β-glucuronidase activity after growth in media with and without tetracycline (Table 3). In the absence of tetracycline, β-glucuronidase activity was below the limit of detection in strains that express uidA from the PmcrB(tetO1), PmcrB(tetO3) and PmcrB(tetO4) promoters, suggesting that TetR binding prevents transcription from the hybrid promoters. The level of expression was significantly lower than that observed from the PmcrB(AAA) promoter in which the TATA box was intentionally destroyed. Thus, the TetR-binding sites prevent even basal rates of transcription in these strains. Addition of tetracycline to the cultures resulted in activities that ranged from high to low (Table 3). (Tetracycline did not change the growth rate of wild-type strains (data not shown).) These data indicate that the TetR-binding sites alter the efficiency of the hybrid promoters, lowering the induced expression by a factor of two to 35, relative to the wild-type PmcrB promoter. Nevertheless, each of the resulting promoters was tightly regulated by the presence or absence of tetracycline.

Table 3.

Gus activity of PmcrB::uidA fusions and derivatives.

| Promoter | Tet | Gus activity (mU) | |

| Chromosome1 | Plasmid2 | ||

| No uidA fusion | – | < 0.4 | nd |

| + | < 0.4 | nd | |

| PmcrB::uidA | – | 1601.1 ± 185.9 | 1760.4 ± 497.5 |

| + | 1502.7 ± 132.0 | 1777.0 ± 389.1 | |

| PmcrB(AAA)::uidA | – | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 26.9 ± 3.9 |

| + | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 22.3 ± 4.6 | |

| PmcrB(tetO1)::uidA | – | < 0.4 | < 0.4 |

| + | 792.8 ± 20.0 | 2598.0 ± 491.2 | |

| PmcrB(tetO3)::uidA | – | < 0.4 | < 0.4 |

| + | 45.2 ± 8.9 | 387.0 ± 81.1 | |

| PmcrB(tetO4)::uidA | – | < 0.4 | < 0.4 |

| + | 385.4 ± 36.3 | 997.0 ± 163.1 | |

1Strains assayed were WWM73 and single-copy integrants of pJK200-PmcrB::uidA, pJK200-PmcrB(AAA)::uidA, pJK200-PmcrB(tetO1)::uidA, pJK200-PmcrB(tetO3)::uidA) and pJK200-PmcrB(tetO4)::uidA into WWM73. 2Strains assayed were WWM60 and WWM60 carrying autonomously replicating plasmid co-integrants pAMG40 with pJK200-PmcrB::uidA, pJK200-PmcrB(AAA)::uidA, pJK200-PmcrB(tetO1)::uidA, pJK200-PmcrB(tetO3)::uidA) and pJK200-PmcrB(tetO4)::uidA.

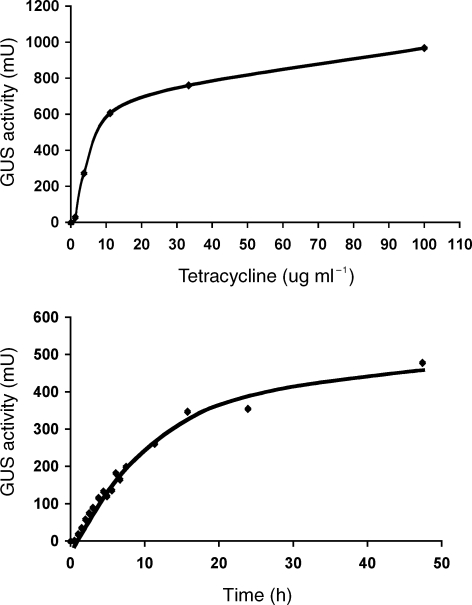

Additional experiments were performed to assess the kinetics of induction and to examine whether expression could be tuned by adding different concentrations of tetracycline (Figure 5). At tetracycline concentrations greater than 33 µg ml–1 induction was essentially complete; however, at lower concentrations of tetracycline (< 10 µg ml–1) a graded response was observed. Expression was not observed when tetracycline was added at less than 0.5 µg ml–1. Time course experiments showed that the response to tetracycline was rapid, with measurable GUS activity being observed within 30 min of the addition of the inducer. However, full expression was not achieved until the cultures reached stationary phase, approximately 48 hours later.

Figure 5.

Dose–response and time course of tetracycline-dependent gene expression in Methanosarcina. Panel A, Plasmid pJK027A was integrated into the chromosome of strain WWM73 and the resulting strain was grown in the presence of various tetracycline concentrations to mid-exponential phase before assaying GUS activity as described. Panel B, The same strain was grown without tetracycline until the culture reached early exponential phase. Tetracycline was then added at a concentration of 100 µg ml–1. At various times, samples were withdrawn and assayed for GUS activity.

We examined regulation by the hybrid promoters when they were carried on multi-copy plasmids in Methanosarcina. To do this we constructed pAMG40, a bifunctional plasmid that replicates in both E. coli and Methanosarcina (Figure 2). The plasmid carries the phage λ-attP site allowing λ-integrase-mediated site-specific recombination with the fosmid vectors described above. Thus, fosmid:pAM40 co-integrants can be constructed by in vitro recombination using commercially available recombinase preparations. This allows facile conversion of the non-replicating integration plasmids described above into autonomous Methanosarcina plasmids. (These experiments are conducted in strains that lack the φC31-int gene to avoid recombination of the multi-copy plasmid into the chromosome.)

Tet-inducible expression of the hybrid promoters carried on autonomous plasmids was 3- to 8-fold higher than that observed when the plasmids were inserted into the chromosome, (Table 3). These values are consistent with the copy number of the pC2A replicon used in pAMG40, which has been estimated at approximately six copies per cell (Sowers and Gunsalus 1988). The more highly expressed promoters showed less of an increase, relative to the chromosomal insertions, than the promoters with lower expression, suggesting that other transcriptional factors may be limiting at high levels of expression.

Use of tet-regulated promoters to test gene essentiality

The exceptionally stringent regulation of the hybrid promoters allows their use to test gene essentiality. To facilitate such studies, we constructed the pGK050 series of plasmids (Table 2), which contain selectable and counter-selectable markers, one of the hybrid promoters and a copy of the PmcrB::tetR gene (Figure 2). To use these plasmids, the gene of interest is fused to the appropriate PmcrB(tetO) promoter (chosen based on the levels of expression of the native gene). A region of homology upstream of the target gene’s promoter is then cloned on the other side of the selectable/counter selectable markers. The resulting plasmid is linearized and recombined onto the chromosome, resulting in replacement of the native promoter with the Tet-regulated promoter. This transformation is performed in the presence of tetracycline to allow expression of the presumptive essential gene. We typically use host strains that carry an additional copy of tetR gene inserted into the chromosomal hpt locus. This greatly reduces the probability of obtaining constitutive, tetR-minus mutants that can confuse the results of the test. Once the strain is verified, growth studies in the presence or absence of tetracycline can be performed to assess whether the cells are viable when the target gene is not expressed (i.e., in the absence of tetracycline). The presence of the counter-selectable marker, which is flanked by recognition sites for the Flp site-specific recombination system, allows removal of the selectable marker should subsequent experiments requiring the puromycin selection be desired (Rother and Metcalf 2005).

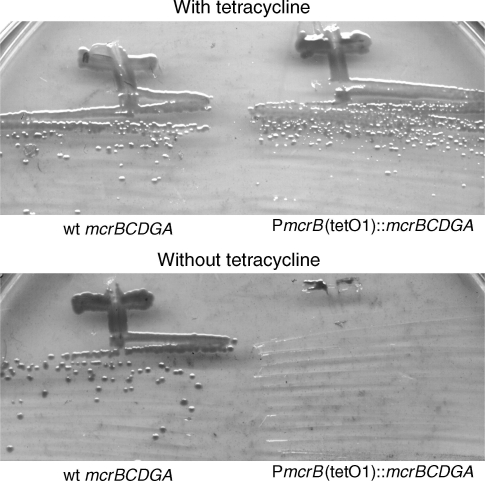

To test this system, we constructed an M. barkeri strain with the mcrBDCGA operon under the control of the PmcrB(tetO1) promoter. The resulting strain grew well on solid medium with the methanol as a growth substrate, so long as tetracycline was included. However, no growth was observed in the absence of tetracycline (Figure 6). Similar results were obtained in liquid media containing acetate, H2/CO2 or H2/CO2/methanol as growth substrates, indicating that the mcr operon is essential for growth on these substrates as well (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Essentiality of the mcr operon in Methanosarcina barkeri. WWM155 and WWM235 were streaked on HS-methanol agar in the presence (100 µg ml–1) or absence of tetracycline. Growth of the PmcrB(tetO1)::mcrBCDGA only in the presence of tetracycline indicates that the mcr operon is essential.

Discussion

The φC31-based site-specific recombination system reported here represents a substantial improvement on previous methods that employ homologous recombination to catalyze stable integration of heterologous DNA into the chromosome of Methanosarcina (Pritchett et al. 2004). Not only is the new system at least 30-fold more efficient at generating recombinants, it also reduces by half the time needed to create strains. The previously used method required a preliminary integration step, followed by a segregation step to produce stable recombinants carrying the DNA of interest. Because growth of Methanosarcina colonies on solid medium requires about 14 days, this method takes a total of about two months because of the need to purify transformants by streaking on solid medium after each step. Thus, utilization of the φC31 system saves a full month over the earlier method. Further, the φC31 integration is unidirectional, providing stability of the insert. In the studies reported here puromycin selection was not maintained after initial isolation of the strain, yet the integrated plasmids were never lost. This system should prove useful for a variety of applications such as single-copy mutant complementation studies, thus relieving problems that occasionally occur when performing episomal complementation of mutants, especially when membrane protein complexes are encoded on the plasmid (Meuer et al. 2002). It is also particularly useful for the construction of promoter gene fusions in Methanosarcina. In a recent study we used this system to place a series of reporter gene fusions into a variety of mutant backgrounds. In this study sixty-eight strains were constructed in a short time with a minimum of effort (Bose and Metcalf 2008). Given the labor and time required, such a study would not have been possible without the efficient and rapid φC31 system.

The observation that many Methanosarcina genes utilize start codons other than ATG raises potential problems in comparing the results obtained using translational reporter genes fusions. For example, mcrB uses a GTG start site, while frhA (encoding a hydrogenase subunit) and pta (encoding phosphotransacetylase) use TTG start sites (Bokranz and Klein 1987, Latimer and Ferry 1993, Vaupel and Thauer 1998). At least one gene, the repA gene of the pC2A plasmid, is predicted to utilize a CTG translation start (Metcalf et al. 1997). Thus, we were interested in determining the relative efficiency of different start codons in Methanosarcina. Our data indicate that GTG, TTG, and even CTG are efficiently used in Methanosarcina, albeit at lower levels than ATG. In cultured monkey CV1 cells TTG and GTG start codons are used poorly, if at all. Instead, translation initiation in this eukaryote occurs efficiently using ACG, and less efficiently using CTG, ATC, ATT and ATA (Peabody 1989). Thus, although archaeal translation initiation is known to share features in common with both bacteria and eukarya (Londei 2005), our data indicate that choice of initiation codon in Methanosarcina is much more similar to bacteria.

Tightly regulated gene expression systems are among the most needed genetic tools in research with archaea (Allers and Mevarech 2005, Rother et al. 2005). Existing expression systems in methanoarchaea are based on fusions of the gene of interest to a catabolic promoter involved, e.g., in methanol, acetate utilization or assimilation of nitrogenous compounds (Apolinario et al. 2005, Lei et al. 2005, Rother et al. 2005). Expression of these fusions is minimized during growth on other substrates and can be induced by switching the culture to the respective catabolic substrate. Thus, expression of the target gene requires growth on a particular substrate, which can be problematic if one is interested in the role of a particular gene under a variety of conditions. We chose to adapt the tetO/TetR system from E. coli because, first, it is well characterized (reviewed in Hillen and Berens (1994) and, second, methanogenic archaea are intrinsically insensitive to tetracycline (Böck and Kandler 1985, Possot et al. 1988). The regulation of the hybrid promoters that we constructed is especially tight and the expression of both homologous and heterologous genes can be induced quickly, several thousand-fold, and independently of the growth phase of the host or the energy substrate utilized. Furthermore, our data suggest that tuning of expression is feasible by titration with tetracycline. However, it remains to be shown if this regulation is dose-dependent for the whole Methanosarcina population, as is the case for tetO/TetR systems in bacteria and eukaryotes, or an autocatalytic induction of expression due to active uptake of the inducer, as is the case for Plac- and Para-dependent gene expression (Novick and Weiner 1957, Morgan-Kiss et al. 2002). With the Pmcr(tetO)/TetR system established for Methanosarcina it seems feasible now to overproduce enzymes in a catalytically active form where other host/overexpresion systems have resulted in partially inactive protein (Roberts et al. 1989, Sauer et al. 1997, Sauer and Thauer Rudolf 1998, Loke et al. 2000). Furthermore, even toxic genes can probably be overproduced because of the tight repression of the hybrid promoter in the absence of tetracycline. The TetR system allows, for the first time, testing gene essentiality in Methanosarcina in a positive, rather than a negative manner. This is in stark contrast to commonly used methods that rely on statistical evidence such as absence of transformants (Stathopoulos et al. 2001).

Finally, this study illustrates the usefulness of φC31 integrase-mediated integration systems and the tetO/TetR mediated system of inducible gene expression in Methanosarcina. Previous studies have demonstrated their functionality in both bacteria and eukarya. That they function in methanogenic archaea, while not surprising, indicates that they could probably be adapted to other archaeal species where genetic systems exist.

Supplementary material

File 1. Methanosarcina Locus pWM357, 8688 bp.

File 2. Methanosarcina pAMG27 3629 bp.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants to WWM from The National Science Foundation (MCB0517419) and the Department of Energy (DE-FG02-02ER15296), and to MR from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (RO 2445/1-1). We thank Arpita Bose for construction of pAB79. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding agencies.

References

- R1.Allers T., Mevarech M. Archaeal genetics—the third way. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005;6:58–73. doi: 10.1038/nrg1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R2.Allmansberger R., Bokranz M., Krockel L., Schallenberg J., Klein A. Conserved gene structures and expression signals in methanogenic archaebacteria. Can. J. Microbiol. 1989;35:52–57. doi: 10.1139/m89-008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R3.Apolinario E.E., Jackson K.M., Sowers K.R. Development of a plasmid-mediated reporter system for in vivo monitoring of gene expression in the archaeon Methanosarcinaacetivorans . Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:4914–4918. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.8.4914-4918.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R4.Ausubel F.M., Brent R., Kingston R.E., Moore D.D., Seidman J.G., Smith J.A., Struhl K. Vol. 3. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1992. Current protocols in molecular biology; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- R5.Baron U., Bujard H. Tet repressor-based system for regulated gene expression in eukaryotic cells: principles and advances. Methods Enzymol. 2000;327:401–421. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)27292-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R6.Beck C.F., Mutzel R., Barbe J., Muller W. A multifunctional gene (tetr) controls tn10-encoded tetracycline resistance. J. Bacteriol. 1982;150:633–642. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.2.633-642.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R7.Belteki G., Gertsenstein M., Ow D.W., Nagy A. Site-specific cassette exchange and germline transmission with mouse ES cells expressing phi C31 integrase. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:321–324. doi: 10.1038/nbt787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R8.Berens C., Hillen W. Gene regulation by tetracyclines. Genet. Eng. 2004;26:255–277. doi: 10.1007/978-0-306-48573-2_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R9.Bierman M., Logan R., Seno E.T., Rao R.N., Schoner B.E. Plasmid cloning vectors for the conjugal transfer of DNA from Escherichiacoli to Streptomyces spp. Gene. 1992;116:43–49. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90627-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R10.Boccazzi P., Zhang J.K., Metcalf W.W. Generation of dominant selectable markers for resistance to pseudomonic acid by cloning and mutagenesis of the ileS gene from the archaeon Methanosarcinabarkeri Fusaro. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:2611–2618. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.9.2611-2618.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R11.Bokranz M., Klein A. Nucleotide sequence of the methyl coenzyme M reductase gene cluster from Methanosarcinabarkeri . Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:4350–4351. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.10.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R12.Bose A., Metcalf W.W. Distinct regulators control the expression of methanol methyltransferase isozymes in Methanosarcinaacetivorans C2A. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;67:649–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R13.Bradford M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R14.Branda C.S., Dymecki S.M. Talking about a revolution: The impact of site-specific recombinases on genetic analyses in mice. Dev. Cell. 2004;6:7–28. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00399-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R15.Böck A., Kandler O. Antibiotic sensitivity of archaebacteria. The Bacteria. 1985;8:525–544. [Google Scholar]

- R16.Groth A.C., Olivares E.C., Thyagarajan B., Calos M.P. A phage integrase directs efficient site-specific integration in human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:5995–6000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090527097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R17.Guss A.M., Mukhopadhyay B., Zhang J.K., Metcalf W.W. Genetic analysis of mch mutants in two methanosarcina species demonstrates multiple roles for the methanopterin-dependent c-1 oxidation/reduction pathway and differences in h(2) metabolism between closely related species. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;55:1671–1680. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R18.Guzman L.M., Belin D., Carson M.J., Beckwith J. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose p-bad promoter. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:4121–4130. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R19.Haldimann A., Wanner B.L. Conditional-replication, integration, excision, and retrieval plasmid-host systems for gene structure–function studies of bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:6384–6393. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.21.6384-6393.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R20.Hillen W., Berens C. Mechanisms underlying expression of tn10 encoded tetracycline resistance. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1994;48:345–369. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.002021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R21.Kamionka A., Bertram R., Hillen W. Tetracycline-dependent conditional gene knockout in Bacillussubtilis . Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:728–733. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.2.728-733.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R22.Latimer M.T., Ferry J.G. Cloning, sequence analysis, and hyperexpression of the genes encoding phosphotransacetylase and acetate kinase from Methanosarcinathermophila . J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:6822–6829. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.21.6822-6829.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R23.Lei T.J., Wood G.E., Leigh J.A. Regulation of nif expression in Methanococcusmaripaludis: roles of the euryarchaeal repressor NrpR, 2-oxoglutarate, and two operators. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:5236–5241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411778200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R24.Loke H.K., Bennett G.N., Lindahl P.A. Active acetyl-CoA synthase from Clostridiumthermoaceticum obtained by cloning and heterologous expression of acsAB in Escherichiacoli . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:12530–12535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220404397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R25.Londei P. Evolution of translational initiation: New insights from the archaea. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2005;29:185–200. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R26.Lutz R., Bujard H. Independent and tight regulation of transcriptional units in Escherichiacoli via the lacR/O, the tetR/O and araC/i-1-i-2 regulatory elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1203–1210. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.6.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R27.Lyznik L.A., Gordon-Kamm W.J., Tao Y. Site-specific recombination for genetic engineering in plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2003;21:925–932. doi: 10.1007/s00299-003-0616-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R28.Metcalf W.W., Zhang J.K., Shi X., Wolfe R.S. Molecular, genetic, and biochemical characterization of the serC gene of Methanosarcinabarkeri Fusaro. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:5797–5802. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5797-5802.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R29.Metcalf W.W., Zhang J.K., Apolinario E., Sowers K.R., Wolfe R.S. A genetic system for archaea of the genus Methanosarcina: Liposome-mediated transformation and construction of shuttle vectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:2626–2631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R30.Metcalf W.W., Zhang J.K., Wolfe R.S. An anaerobic, intrachamber incubator for growth of Methanosarcina spp. on methanol-containing solid media. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998;64:768–770. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.2.768-770.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R31.Meuer J., Kuettner H.C., Zhang J.K., Hedderich R., Metcalf W.W. Genetic analysis of the archaeon Methanosarcina barkeri Fusaro reveals a central role for Ech hydrogenase and ferredoxin in methanogenesis and carbon fixation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:5632–5637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072615499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R32.Morgan-Kiss R.M., Wadler C., Cronan J.E. Long-term and homogeneous regulation of the Escherichiacoli araBAD promoter by use of a lactose transporter of relaxed specificity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:7373–7377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122227599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R33.Novick A., Weiner M. Enzyme induction as an all-or-none phenomenon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1957;43:553–566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.43.7.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R34.Peabody D.S. Translation initiation at non-AUG triplets in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:5031–5035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R35.Possot O., Gernhardt P., Klein A., Sibold L. Analysis of drug resistance in the archaebacterium methanococcus voltae with respect to potential use in genetic engineering. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1988;54:734–740. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.3.734-740.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R36.Pritchett M.A., Zhang J.K., Metcalf W.W. Development of a markerless genetic exchange method for Methanosarcinaacetivorans C2A and its use in construction of new genetic tools for methanogenic archaea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:1425–1433. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.3.1425-1433.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R37.Roberts D.L., James-Hagstrom J.E., Garvin D.K., Gorst C.M., Runquist J.A., Baur J.R., Haase F.C., Ragsdale S.W. Cloning and expression of the gene cluster encoding key proteins involved in acetyl-CoA synthesis in Clostridiumthermoaceticum: CO dehydrogenase, the corrinoid/Fe-S protein, and methyltransferase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1989;86:32–36. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R38.Rother M., Metcalf W.W. Genetic technologies for archaea. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2005;8:745–751. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R39.Rother M., Boccazzi P., Bose A., Pritchett M.A., Metcalf W.W. Methanol-dependent gene expression demonstrates that methyl-coenzyme M reductase is essential in Methanosarcinaacetivorans C2A and allows isolation of mutants with defects in regulation of the methanol utilization pathway. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:5552–5559. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.16.5552-5559.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R40.Sauer K., Thauer Rudolf K. Methanol:Coenzyme M methyltransferase from Methanosarcinabarkeri: Identification of the active-site histidine in the corrinoid-harboring subunit MtaC by site-directed mutagenesis. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998;253:698–705. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2530698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R41.Sauer K., Harms U., Thauer R.K. Methanol:Coenzyme M methyltransferase from Methanosarcinabarkeri. Purification, properties and encoding genes of the corrinoid protein MT1. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997;243:670–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R42.Schweizer H.P. Applications of the saccharomyces cerevisiae Flp-frt system in bacterial genetics. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003;5:67–77. doi: 10.1159/000069976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R43.Sowers K.R., Gunsalus R.P. Plasmid DNA from the acetotrophic methanogen Methanosarcinaacetivorans . J. Bacteriol. 1988;170:4979–4982. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.10.4979-4982.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R44.Sowers K.R., Schreier H.J. Gene transfer systems for the archaea. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:212–219. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01492-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R45.Sowers K.R., Boone J., Gunsalus R.P. Disaggregation of methanosarcina spp. and growth as single cells at elevated osmolarity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993;59:3832–3839. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.11.3832-3839.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R46.Sprengel R., Hasan M.T. Tetracycline-controlled genetic switches. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2007;178:49–72. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-35109-2_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R47.Stathopoulos C., Kim W., Li T., Anderson I., Deutsch B., Palioura S., Whitman W., Soll D. Cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase is not essential for viability of the archaeon Methanococcusmaripaludis . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:14292–14297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201540498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R48.Thomason L.C., Calendar R., Ow D.W. Gene insertion and replacement in Schizosaccharomycespombe mediated by the Streptomyces bacteriophage phi C31 site-specific recombination system. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 2001;65:1031–1038. doi: 10.1007/s004380100498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R49.Thorpe H.M., Smith M.C.M. In vitro site-specific integration of bacteriophage DNA catalyzed by a recombinase of the resolvase/invertase family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:5505–5510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R50.Vaupel M., Thauer R.K. Two F420-reducing hydrogenases in Methanosarcinabarkeri . Arch. Microbiol. 1998;169:201–205. doi: 10.1007/s002030050561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R51.Wanner B.L. Novel regulatory mutants of the phosphate regulon in Escherichiacoli K-12. J. Mol. Biol. 1986;191:39–58. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90421-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R52.Wild J., Hradecna Z., Szybalski W. Conditionally amplifiable BACs: Switching from single-copy to high-copy vectors and genomic clones. Genome Res. 2002;12:1434–1444. doi: 10.1101/gr.130502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R53.Zhang J.K., Pritchett M.A., Lampe D.J., Robertson H.M., Metcalf W.W. In vivo transposon mutagenesis of the methanogenic archaeon Methanosarcina acetivorans C2A using a modified version of the insect mariner-family transposable element Himar1 . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:9665–9670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160272597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R54.Zhang J.K., White A.K., Kuettner H.C., Boccazzi P., Metcalf W.W. Directed mutagenesis and plasmid-based complementation in the methanogenic archaeon Methanosarcinaacetivorans C2A demonstrated by genetic analysis of proline biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:1449–1454. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.5.1449-1454.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

File 1. Methanosarcina Locus pWM357, 8688 bp.

File 2. Methanosarcina pAMG27 3629 bp.