Abstract

Ascorbic acid (AsA) biosynthesis in plants occurs through a complex, interconnected network with mannose (Man), myoinositol, and galacturonic acid as principal entry points. Regulation within and between pathways in the network is largely uncharacterized. A gene that regulates the Man/l-galactose (l-Gal) AsA pathway, AMR1 (for ascorbic acid mannose pathway regulator 1), was identified in an activation-tagged Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) ozone-sensitive mutant that had 60% less leaf AsA than wild-type plants. In contrast, two independent T-DNA knockout lines disrupting AMR1 accumulated 2- to 3-fold greater foliar AsA and were more ozone tolerant than wild-type controls. Real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction analysis of steady-state transcripts of genes involved in AsA biosynthesis showed that AMR1 negatively affected the expression of GDP-Man pyrophosphorylase, GDP-l-Gal phosphorylase, l-Gal-1-phosphate phosphatase, GDP-Man-3′,5′-epimerase, l-Gal dehydrogenase, and l-galactono-1,4-lactone dehydrogenase, early and late enzymes of the Man/l-Gal pathway to AsA. AMR1 expression appears to be developmentally and environmentally controlled. As leaves aged, AMR1 transcripts accumulated with a concomitant decrease in AsA. AMR1 transcripts also decreased with increased light intensity. Thus, AMR1 appears to play an important role in modulating AsA levels in Arabidopsis by regulating the expression of major pathway genes in response to developmental and environmental cues.

l-Ascorbic acid (AsA; vitamin C) is a major antioxidant molecule in plants, an essential cofactor for several important metal-containing enzymes, and is implicated in the control of cell division and growth (Davey et al., 2000; Smirnoff and Wheeler, 2000; Arrigoni and De Tullio, 2002; De Tullio and Arrigoni, 2004). As a major antioxidant, AsA protects plants from oxidative stress by decomposing reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated through normal oxygenic metabolism and adverse environmental assaults (Smirnoff, 1996; Noctor and Foyer, 1998; Conklin and Barth, 2004). Since ROS are highly toxic substances and can act as signaling molecules (Davletova et al., 2005), they must be rigidly controlled to prevent oxidization of proteins and damage to the structural and functional integrity of membranes (Smirnoff, 1996). To achieve these multiple functions, the ability to tightly control AsA levels through biosynthesis and degradation pathways would be an advantageous strategy for higher plants. A complex network for producing AsA through several biosynthetic routes has been discovered. Entry points into the network are d-Man (Wheeler et al., 1998), d-galacturonate (Agius et al., 2003), and myoinositol (Lorence et al., 2004). All genes of the major pathway, the Man pathway, have been characterized, including the GDP-d-Man pyrophosphorylase (Conklin et al., 1999), the GDP-Man-3′,5′-epimerase (Wolucka and Van Montagu, 2003), l-Gal dehydrogenase (GalDH; Gatzek et al., 2002), l-galactono-1,4-lactone dehydrogenase (Imai et al., 1998), the l-Gal-1-P phosphatase (GPP; Laing et al., 2004), and, more recently, the GDP-l-Gal phosphorylase (also known as VTC2 and its close homolog VTC5) that converts GDP-l-Gal to l-Gal-1-P (Dowdle et al., 2007; Linster et al., 2007, 2008) and a l-Gal guanyltransferase that also converts GDP-l-Gal to l-Gal-1-P (Laing et al., 2007). In support of the importance of the Man/l-Gal pathway, a double mutant (VTC2/VTC5) showed growth arrest immediately upon germination and the cotyledons subsequently were bleached, while normal growth was restored by supplementation with ascorbate or l-Gal (Dowdle et al., 2007). While the regulatory mechanisms, operating within the different synthetic, recycling, and degradation routes to modulate AsA content, are just beginning to be described (for review, see Wolucka and Van Montagu, 2007; Linster and Clarke, 2008), global control processes within the different pathways and cross talk in the network are still largely unexplored. Knowledge of AsA biosynthesis and its regulation would advance approaches toward the metabolic engineering of this important antioxidant.

Foliar AsA content can be regulated through gene expression by both developmental triggers and environmental cues (Smirnoff and Wheeler, 2000). Temperature stress (Koh, 2002) and high light intensity (Smirnoff, 2000; Bartoli et al., 2006) cause AsA levels to increase. Additionally, a degradation route for apoplastic AsA has been proposed (Green and Fry, 2005). The specific mechanisms eliciting these changes are not known in detail, although low light levels decreased transcripts of GDP-Man pyrophosphorylase (GMP) and l-galactono-1,4-lactone dehydrogenase (GLDH) in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) leaves (Tabata et al., 2002), while high light caused increased expression of VTC2 in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; Dowdle et al., 2007; Yabuta et al., 2007; Müller-Moulé 2008). In Arabidopsis and tobacco, AsA changes diurnally, being lowest at night and increasing throughout the day (Pignocchi et al., 2003; Tamaoki et al., 2003), although this type of fluctuation is absent in other species such as potato (Solanum tuberosum; Imai et al., 1999) and wheat (Triticum aestivum; Bartoli et al., 2005). Ascorbate content of foliar tissue can be increased through enhanced AsA recycling by overexpression of dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR; Chen et al., 2003). Developmentally, foliar AsA is higher in young leaves than in presenescent leaves, and the loss of AsA as tissue matures has been associated with decreases in DHAR activity in tobacco and corn (Zea mays; Chen et al., 2003) and GLDH expression in Arabidopsis (Tamaoki et al., 2003).

Within the Man/l-Gal pathway, substrate availability and enzymatic activity have been shown to regulate AsA synthesis to some degree. Endogenous l-Gal content is rate limiting (Wheeler et al., 1998), suggesting that control lies in production of this substrate. Suppression of GDP-d-Man pyrophosphorylase activity lowered AsA levels (Keller et al., 1999), whereas down-regulation of both GalDH (Gatzek et al., 2002) and GLDH (Tabata et al., 2002) had little effect on AsA content, although the last caused a strong reduction in leaf and fruit size in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), mainly as a consequence of reduced cell expansion (Alhagdow et al., 2007). Ascorbate supplementation decreased VTC2 expression in Arabidopsis, suggesting feedback inhibition by AsA at the transcriptional level (Dowdle et al., 2007). The activity of the branch pathway enzyme, GDP-d-Man-3′,5′-epimerase, is partially inhibited or stimulated by several substrates, as is the redox state of NADH/NADPH, making the epimerase a likely regulatory point (Wolucka and Van Montagu, 2003). Detailed control of AsA biosynthesis in the myoinositol and galacturonate pathways is not known, although high light has been reported to have a positive effect in the expression of the promoter of d-galacturonate reductase (Agius et al., 2005). We recently characterized a purple acid phosphatase with phytase activity (AtPAP15; At3g07130) that may modulate AsA by contributing to the input of free myoinositol into this branch of the AsA biosynthetic network in Arabidopsis (Zhang et al., 2008).

In this work, we show that expression of AMR1 (for ascorbic acid mannose pathway regulator 1), a gene isolated from an activation-tagged (AT) Arabidopsis mutant, is inversely correlated with changes in leaf AsA content. Furthermore, this decrease in AsA appears to result from a coordinated reduction in the expression of genes encoding enzymes in the Man/l-Gal AsA metabolic network, suggesting that AMR1 serves as a negative regulator of this major AsA pathway in plants.

RESULTS

Identification of an AT Mutant with Reduced Leaf AsA

Mutant selection was conducted on lines developed using the pSKI015 AT vector. This vector contains four repeats of the Pro-35S enhancer, and introduction of this T-DNA into the genome can cause increased gene expression near the site of integration in an orientation-independent manner (Weigel et al., 2000). An ozone screen was used to select for low and high AsA (see “Materials and Methods”). We identified AT23061 as a low AsA phenotype from approximately 5,000 independent T1 lines. As illustrated in Figure 1A, line AT23061 was consistently observed to be smaller in size compared with wild-type controls of the same age growing under similar conditions and was found to be sensitive to ozone (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

The phenotype of the AT mutant AT23061 (ecotype Columbia) has increased sensitivity to ozone, higher foliar AsA, and higher expression of AMR1 than wild-type (WT) plants. A, AT23061 at 3 weeks of age is smaller than wild-type plants but otherwise morphologically similar. B, Leaf injury on AT23061 after ozone treatment at 200 nL L−1 for 4 h was considerably more severe than on wild-type plants. C, Foliar total AsA (oxidized + reduced) in AT23061 was 60% less than in Col-0. Tissue was sampled from the second rosette leaf of 3-week-old plants. Bars represent means ± sd (n = 3). FW, Fresh weight. D, DNA gel-blot analysis of the pSKI015 plasmid indicated two insertions in AT23061. Total DNA from AT23061 (4 μg) was digested with EcoRI and hybridized with the whole KS plasmid, digested with EcoRI, as the probe. E, Expression analysis by RT-PCR of AMR1 in AT23061. The AMR1 signal was first normalized to the ATPase signal and then compared with the wild-type signal. Relative AMR1 intensities are shown under each lane as the percentage of signal relative to that in the wild type.

Total foliar AsA in AT23061 (1.0 μmol g−1 fresh weight) was about 60% less than that in wild-type plants (2.6 μmol g−1 fresh weight) at 3 weeks of age (Fig. 1C). A Southern blot, using the Stratagene pBluescript KS− (KS) plasmid as a probe, showed that the mutant contained two T-DNA insertions (Fig. 1D). Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis (Fig. 1E) indicated that the increased expression of a gene of unknown function was responsible for conferring ozone sensitivity in AT23061 compared with wild-type plants (see identification procedure below).

Identification of AMR1 by Thermal Asymmetrical Interlaced-PCR and Analysis of Its Gene Structure

To identify AT insertion positions and possible genes responsible for the mutant AT phenotype, the sites of the two T-DNA insertions within the AT23061 genome were determined by thermal asymmetrical interlaced (TAIL)-PCR (Liu and Whittier, 1995). Two sequences were obtained from the TAIL-PCR analysis. One T-DNA insertion was located in chromosome 4 in an intergenic region (Fig. 2A). The second insertion was situated in chromosome 1 and 400 bp upstream of At1g65770 (Fig. 2A). At1g65770 was designated AMR1 and has an uninterrupted open reading frame (ORF) of 1,083 bp encoding a novel 360-amino acid protein (Fig. 2B). Domain search analyses, using SMART (Schultz et al., 1998; Letunic et al., 2004) and Pfam (Bateman et al., 2004) databases, indicated that AMR1 contains an F-box domain situated at amino acids 4 to 50. The F-box motif location, near the N terminus, is typical for this class of proteins, and AMR1 shows sequence homology to several known F-box proteins in humans (SKP2 and FBX4) and Arabidopsis (ORE9, SLEEPY1, FKF1, UFO, and SON1; Fig. 2C). Many F-box proteins contain functional domains in their C-terminal regions, such as Leu-rich, WD-40, Armadillo, or Kelch repeats, which are implicated in protein-protein interactions and believed to play a role in substrate recognition (Patton et al., 1998; Gagne et al., 2002). Our search indicated that AMR1 contains a common plant domain of unknown function (MMEVKSLGDKAFVIATDTCFSVLAHEFYGCLENAIYFTDDT) from amino acids 285 to 332 (DUF295), suggesting that AMR1 may belong to a separate class of proteins with F-box domains. However, several Arabidopsis proteins, whose functions are not yet described, also contain both the F-box and DUF295 motifs, indicating that AMR1-type proteins are not unique.

Figure 2.

Integration positions of the pSK1015 plasmid in the AT mutant AT23061, the primary structure of AMR1, and sequence homology of the AMR1 F-box motif with known F-box proteins. A, In AT23061, T-DNA insertions were identified in chromosomes (Chr) 4 and 1 by TAIL-PCR. The insertion in chromosome 4 was in an intergenic region, whereas the insertion in chromosome 1 was about 400 by upstream of At1g65770. B, The primary structure of At1g65770 indicated an F-box motif near the N terminus of the protein. C, Sequence homology of AMR1 with human (SKP2 and FBX4) and Arabidopsis (ORE9, SLEEPY1, FKF1, UFO, and SON1) F-box proteins. The consensus sequence was generated using ClustalW on the aligned sequences.

Insertion Mutants amr1-1 and amr1-2 Have Higher Foliar AsA and Ozone Tolerance

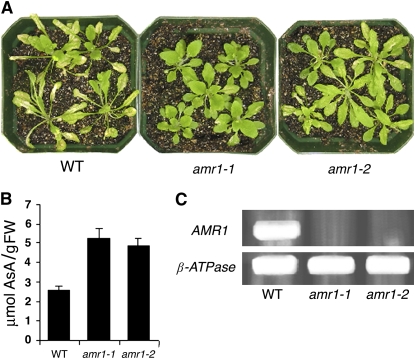

The SALK T-DNA Express Arabidopsis gene-mapping tool (http://signal.salk.edu/cgi-bin/tdnaexpress) was used to identify two insertional mutants: lines SALK_081886 (designated as amr1-1) and SALK_113413 (designated as amr1-2), which contained insertions in the predicted At1g65770 ORF. PCR analysis, using T-DNA internal and 3′/5′ primer pairs of AMR1, confirmed that the two mutants have insertions in different regions of the AMR1 coding sequence (data not shown) and that each has only one T-DNA insertion. The phenotype of these two knockout lines was very similar when grown in an environmental control chamber, and both had increased resistance to ozone, displaying less foliar injury than wild-type plants when exposed to 450 nL L−1 for 4 h (Fig. 3A). The mutant amr1-1 appeared to be somewhat more ozone tolerant than amr1-2, and this may be a function of a slightly higher foliar AsA content in amr1-1. Total AsA levels in amr1-1 (5.3 μmol g−1 fresh weight) and amr1-2 (4.9 μmol g−1 fresh weight) were approximately 2-fold higher than in control plants (2.6 μmol g−1 fresh weight; Fig. 3B). RT-PCR did not detect AMR1 expression in the two T-DNA insertion lines (Fig. 3C). Thus, the absence of AMR1 expression in the amr1mutants resulted in increased levels of foliar AsA, which suggests that AMR1 may function to inhibit the synthesis or promote the degradation of AsA.

Figure 3.

Phenotypes of amr1-1 and amr1-2, two T-DNA knockout lines in AMR1, demonstrated increased ozone tolerance and higher foliar AsA levels. A, Leaf injury in wild-type (WT) plants at 3 weeks of age was more severe than in amr1-1 or amr1-2 after ozone exposure at 450 nL L−1 for 4 h. B, Foliar total AsA was about 2-fold higher in amr1-1 and amr1-2 than in the wild type. Tissue was sampled from the second rosette leaves of 3-week-old plants. Bars represent means ± sd (n = 3). FW, Fresh weight. C, RT-PCR analysis of the insertion mutants indicated no detectable expression of AMR1 in amr1-1 and amr1-2 plants.

AMR1 Is a Negative Regulator of Genes Encoding Enzymes of the Man/l-Gal AsA Pathway

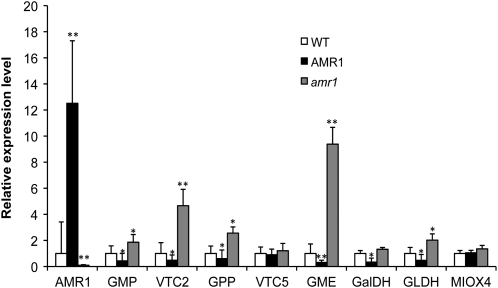

Since AsA pool homeostasis is determined by many factors, such as degradation, transport, and utilization, in addition to synthesis (Smirnoff et al., 2001), we conducted real-time RT-PCR experiments to address the relationship between AMR1 and AsA metabolism. Steady-state transcripts of GMP (Conklin et al., 1999), VTC2 (Dowdle et al., 2007; Linster et al., 2007), GDP-Man-3′,5′-epimerase (GME; Wolucka and Van Montagu, 2003), GPP (Laing et al., 2004), GalDH (Gatzek et al., 2002), and GLDH (Wheeler et al., 1998), early and late enzymes of the Man/l-Gal pathway to AsA, were up-regulated in the amr1-1 insertional mutant but down-regulated in the AT mutant when compared with wild-type plants (Fig. 4). Therefore, AMR1 seems to be a negative regulator that specifically affects genes/enzymes of the Man/l-Gal pathway (Wheeler et al., 1998). Additionally, we did not observe any effect on the expression of myoinositol oxygenase (MIOX4; Lorence et al., 2004), the first enzyme of the myoinositol pathway to AsA.

Figure 4.

Expression levels by real-time PCR of genes of the Man/l-Gal biosynthetic pathway to AsA and the MIOX4 gene in the wild type (WT), the amr insertional mutant, and the AMR1 AT mutant AT23061. Tested genes are as follows: GMP, VTC2, GPP, VTC5, GME, GalDH, GLDH, and MIOX4. Bars represent means ± sd (n = 3). Asterisks denote results that are significantly different from the wild-type findings (** P < 0.005, * P < 0.05). The statistical significance was evaluated by t test.

Expression of AMR1 Is Developmentally and Light Controlled

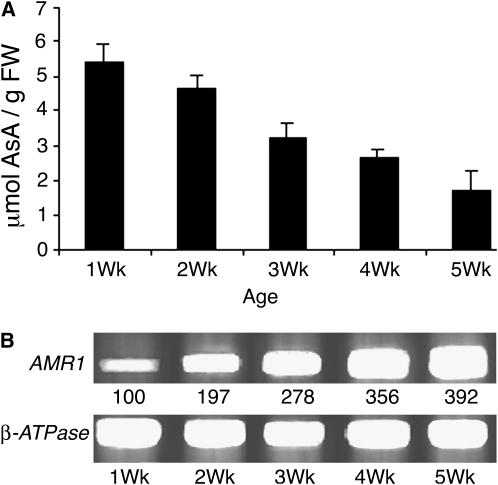

Both RT-PCR and promoter-reporter gene fusion studies were used to examine the expression patterns of AMR1. RT-PCR analysis of AMR1 transcript levels in wild-type leaves was compared with AsA content during development. AsA was highest in 1-week-old plants (5.4 μmol g−1 fresh weight) and progressively decreased with age to 1.5 μmol g−1 fresh weight in 5-week-old plants (Fig. 5A). Concurrent with the decrease in AsA, expression of AMR1 increased over time, being minimally detectable in 1-week-old seedlings and reaching a maximum, 4-fold greater, in 5-week-old plants (Fig. 5B). This inverse relationship between AsA content and AMR1 gene expression during development further supports the idea that AMR1 is involved in the negative regulation of AsA content.

Figure 5.

Age-dependent changes in leaf AsA are inversely correlated with AMR1 transcription levels. A, Total leaf AsA content in wild-type plants declined with leaf age. Tissue was sampled from the rosette leaves. Bars represent means ± sd (n = 3). FW, Fresh weight. B, RT-PCR expression analysis of AMR1 in wild-type plants indicated an increase in transcript with leaf age. Signal intensity was calculated as described in Figure 1.

To examine the spatial expression of AMR1, we fused the GUS reporter gene to a 1-kb segment of the AMR1 promoter and transformed ecotype Columbia (Col-0) Arabidopsis with the fusion construct. At least six independently transformed lines containing the construct were examined histochemically for GUS expression. A homozygous line was used to compare the expression under low-light conditions (approximately 50 μE m−2 s−1) and that under high-light conditions (approximately 200 μE m−2 s−1) at different developmental stages (1, 2, and 3 weeks old). GUS activity was evident in the low-light conditions at all ages (Fig. 6, A, C, and E), although much less staining was observed in the same-age seedlings under the high-light conditions (Fig. 6, B, D, and F). No GUS activity was apparent in the first true leaf as it emerged in 2-week-old and 3-week-old plants, nor was GUS expression obvious in the roots or hypocotyls at this time. In 12-d-old seedlings under moderate light (100–150 μE m−2 s−1), differential staining was apparent depending on leaf age (Fig. 6G). The oldest leaves stained most intensely, especially at the leaf tips and margins. Color intensity decreased steadily with leaf juvenility, and no GUS activity was detectable in the apical meristem. This GUS expression pattern, driven by the AMR1 promoter, confirmed the developmental and light control of AMR1 expression.

Figure 6.

Expression analysis of AMR1 using the GUS reporter gene. A, In 1-week-old seedlings, AMR1 expression was most evident in the apical region of the cotyledons and in the hypocotyls of seedlings grown under low-light conditions (approximately 50 μE m−2 s−1). B, AMR1 was slightly expressed in the apical region of the cotyledons of 1-week-old seedlings grown under high-light conditions (approximately 200 μE m−2 s−1). C, In 2-week-old seedlings grown under low light, AMR1 expression was evident in the cotyledons and less in the newly emerging leaf. D, AMR1 expression in 2-week-old seedlings under high-light conditions was confined primarily to cotyledons and was not evident in young leaves. E, In 3-week-old seedlings grown under low-light conditions, AMR1 was intensely expressed in older leaves and was less expressed in young leaves. F, In 3-week-old seedlings under high light, AMR1 was expressed minimally in older leaves and was much diminished in younger leaves. No expression was detected in roots and hypocotyls. G, In 2-week-old seedlings grown under normal light conditions (100–150 μE m−2 s−1), AMR1 expression was greatest in the older leaves and was less in younger leaves; no staining was evident in the apical meristem.

DISCUSSION

A mutant screen, using ozone to promote foliar oxidative damage, has previously been successful in identifying several low-AsA phenotypes in Arabidopsis plants derived from ethyl methanesulfonate-treated seeds (Conklin, 1998). T-DNA activation tagging (Weigel et al., 2000) is a highly efficient mutagenesis method, since insertion of the foreign DNA either activates (upstream or downstream of the ORF) or disables (in the ORF) gene expression at a high frequency. We screened approximately 5,000 AT lines and identified 12 mutants with either higher (>150%) or lower (<40%) AsA compared with Col-0. One of these mutants (AT23061), which displayed ozone-induced foliar lesions, had leaf AsA levels about 60% lower than wild-type plants. TAIL-PCR analysis localized a T-DNA insertion in the promoter region of At1g65770, a gene of unknown function. Further in silico analysis demonstrated that the At1g65770 gene product, named AMR1, contains an F-box domain near its N terminus, suggesting that At1g65770 may encode an F-box protein that is associated with the negative regulation of leaf AsA content. The AMR1 F-box domain has high homology with several other F-box proteins in both plants and animals, including ORE9 and UFO, which are known to form SCF (for Skp1-Cullin-F-box) E3 ligases (Woo et al., 2001; Moon et al., 2004; Ni et al., 2004).

F-box proteins are involved in a universal regulatory strategy that is common to both plants and animals. These proteins are part of the SCF-ubiquitin-E3 ligase complex that is involved in recognition of both the E2 protein, containing activated ubiquitin, and the substrate targeted for ubiquitination (Bai et al., 1996; Xiao and Jang, 2000). Selective protein degradation by the ubiquitin-proteosome pathway is a powerful regulatory mechanism in a wide variety of cellular processes, including floral development, circadian clock, lateral root formation, light signaling, pollen recognition, and response to plant growth regulators (del Pozo and Estelle, 2000; Lechner et al., 2006). In several of these regulation processes, F-box proteins are identified as negative regulators, such as EBF1 and EBF2, regulators involved in negative regulation in ethylene signaling (Potuschak et al., 2003). Additional examples of negative regulators are SCON2, Fbx13, and FBX2. SCON2 acts within the Neurospora crassa sulfur regulatory network as a negative regulator (Kumar and Paietta, 1998), while Fbxl3 controls the circadian clock by mediating the degradation of CRY proteins that establish a negative feedback loop (Busino et al., 2007). FBX2 was identified as a negative regulator in inorganic phosphate starvation responses (Chen et al., 2008), and in this study, we found AMR1 to be involved in negative regulation of AsA biosynthesis.

Target specificity of F-box proteins is conferred by their C-terminal ends, which usually contain a recognizable protein-protein interaction region in the form of Leu-rich, WD-40, Armadillo, or Kelch repeats (Craig and Tyers, 1999; Andrade et al., 2001; Gagne et al., 2002). The C-terminal region of AMR1 includes an identifiable plant protein domain (DUF295), but its function is unknown. This domain may be involved in target recognition and binding; however, the absence of a recognizable protein-protein interaction region suggests that AMR1 is unique among known Arabidopsis F-box proteins.

Our data show that AMR1 is involved in modulating the expression of several genes in the Man/l-Gal pathway for AsA biosynthesis. The transcript level of GME was affected the most by AMR1. Although photosynthetic electron transport is suggested to play an important role in the regulation of the transcript levels of genes in the Man/l-Gal pathway, GME was not one of them (Yabuta et al., 2007). GME, a highly conserved enzyme among both dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous plants, also forms GPD-l-gulose, and l-gulose is a possible precursor of vitamin C biosynthesis in plants. In addition, the detailed biochemical characterization of the GME protein (i.e. regulation redox state of NADH/NADPH) indicates that regulation of this enzyme is relevant for both the Man/l-Gal and gulose pathways (Wolucka and Van Montagu, 2003, 2007; Major et al., 2005; Watanabe et al., 2006). In addition, GME is regulated by jasmonates (Wolucka et al., 2005).

Our experiments also indicate significant increases in transcript levels of VTC2 in the amr1 mutant. It has been recently proposed that VTC2 might be a dual-function protein, with both enzymatic and regulatory functions, as fusion VTC2:fluorescent proteins have been localized in both the cytosol and the nucleus (Müller-Moulé, 2008). The transcripts of GMP, GPP, and GLDH were also affected by AMR1. It was recently demonstrated that the transcript levels of GMP, GPP, VTC2, and GLDH are elevated specifically in response to photosynthetic electron transport (Yabuta et al., 2007). The expression of GMP is also induced by jasmonates (Sasaki-Sekimoto et al., 2005). Transcript levels of GLDH in young rosette leaves of Arabidopsis increase about 2-fold during the day (Tamaoki et al., 2003). The conversion to ascorbate by l-galactono-1,4-lactone is also controlled by photosynthetic electron transport, although not at the transcriptional level (Yabuta et al., 2008). Transcriptional regulation appears to be specific to one portion of the AsA biosynthetic network, since myoinositol oxygenase expression was unaffected by AMR1 transcript levels. It is interesting that most Man/l-Gal pathway genes are single-copy genes in Arabidopsis and that AMR1, therefore, can regulate metabolite flux to AsA efficiently without potential compensatory effects of multiple gene family members.

Because amr1 mutants demonstrated increased levels of AsA, it was of interest to determine whether the loss of AMR1 would result in greater tolerance to ozone. AsA is an integral weapon in the defense against ROS generated by oxidative stress, and foliar application of AsA has been known as an ozone protectant for decades (Freebairn, 1960). More recently, several studies have demonstrated a correlation between total foliar AsA levels and ozone tolerance, a now classic example being the vtc1-1 Arabidopsis mutant (for review, see Conklin and Barth, 2004). Also, overexpression in tobacco of the AsA-recycling enzyme DHAR increased foliar AsA and conferred increased ozone tolerance (Chen and Gallie, 2005).

AsA in the apoplastic space, where ROS are initially generated, has been considered the primary defense against ozone incursion. However, in two white clover (Trifolium repens) clones, NC-S and NC-R, neither the amount of extracellular or symplastic AsA nor its oxidation state correlated with ozone tolerance, indicating that additional ROS-neutralizing strategies exist in some species (D'Haese et al., 2005). Ozone treatment revealed that the two Arabidopsis insertion mutants, amr1-1 and amr1-2, are indeed more tolerant to this oxidative stress compared with wild-type plants. These results support previous studies showing the relationship between high foliar AsA and ozone tolerance (Conklin et al., 1997; Maddison et al., 2002; Pasqualini et al., 2002; Conklin and Barth, 2004).

Biosynthesis of jasmonates is required for ozone tolerance, and jasmonate signaling regulates the biosynthesis of AsA by activating the expression of GMP and VTC2 (Sasaki-Sekimoto et al., 2005). The mechanism of AsA protection against ozone has not been clearly demonstrated and may involve jasmonate signaling, redox status, modification of cell wall structure, or other metabolic processes in addition to scavenging of ROS.

AsA also plays a role in senescence: low AsA promotes senescence, whereas high AsA delays senescence (Navabpour et al., 2004). In the AsA-deficient mutant vtc1-1, induction of some senescence-associated genes (SAGs) occurred prematurely (Barth et al., 2004). Furthermore, in the presence of exogenous AsA, expression levels of SAG13 and PR1 decreased to wild-type levels. The expression pattern of AMR1 in wild-type plants demonstrated that this gene had highest expression in older leaf tissue, which also had lowest AsA. AMR1, therefore, may function in controlling leaf senescence by depleting AsA levels, and expression studies of SAGs in AMR1 plants could provide support for this hypothesis.

We hypothesize that AMR1 may function as a component of an SCF ubiquitin ligase complex and interact specifically with a positive regulatory protein controlling its quantity and stability through ubiquitination. Additional work is necessary to identify the various components of this complex, especially the target of AMR1, and to explore how the interaction between the target protein and the ubiquitination pathway is involved in the coordinated regulation of several genes in the Man/l-Gal pathway in response to developmental and environmental cues. Such future studies should lead to a better understanding of the regulation of this important molecule.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) Col-0 was used for comparison with mutant plants. Growth conditions were 16-h days at 22°C and 8-h nights at 16°C under 100 to 150 μmol m−2 s−1 photosynthetically active radiation. The AT plants containing pSKI015 (Basta resistance) were screened with 0.1% Basta before ozone treatment. The homozygous amr1-1 and amr1-2 mutant lines (lines SALK_088186 and SALK_113413) were identified as segregating lines in T3 seeds provided by the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (Alonso et al., 2003). Homozygous lines were developed by kanamycin selection and confirmed by PCR (the specific gene cannot be amplified in a homozygous line due to the T-DNA insertion).

Ozone Fumigation Screen of AT Mutants

Four-week-old AT plants were exposed to ozone at concentrations of 150 to 200 nL L−1 for 4 h in a continuously stirred tank reactor. Ozone was generated from oxygen by UV discharge (Osmonics) and delivered to the chambers by flow meters. Ozone concentrations in the chambers were monitored with a TECO UV photometric ozone analyzer (Thermo Electron) and regulated through the flow meters. Damaged plants were selected for analysis to identify lines with reduced AsA levels. Selected mutants were treated with ozone three times to confirm the ozone response.

Leaf Tissue AsA Measurement

AsA content of leaves was measured by the AsA oxidase assay (Rao and Ormrod, 1995). Plant extracts were made from tissue frozen in liquid nitrogen, ground in 6% (w/v) meta-phosphoric acid, and centrifuged at 15,000g for 15 min. Reduced AsA was determined by measuring the decrease in A265 (extinction coefficient of 14.3 cm−1 mm−1) after the addition of 1 unit of AsA oxidase (Sigma) to 1 mL of the reaction mixture containing the plant extract in 100 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.9). Oxidized AsA was measured by the increase in A265 after addition of 1 μL of 0.2 mm dithiothreitol and incubating at room temperature for 15 min. Total AsA is the sum of reduced AsA and oxidized AsA.

Isolation of Genomic DNA and Southern-Blot Hybridization

Total Arabidopsis DNA was isolated using the Qiagen plant DNA extraction kit. Isolated DNA was digested with the restriction endonuclease EcoRI, loaded onto a 0.8% (w/v) agarose gel, denatured with 0.5 m NaOH/1.5 m NaCl, and transferred by mass flow to a blotting membrane (Bio-Rad). The membrane was briefly neutralized in 0.5 m Tris-HCl and 1.5 m NaCl, pH 8.0, and DNA was immobilized by UV irradiation. The membrane was treated with a prehybridization solution (0.5 m sodium phosphate, pH 7.2, and 7% SDS) for 1 h at 65°C. Gene-specific 32P-labeled KS plasmid, which was cut by EcoRI, was denatured by incubation at 65°C in the presence of 0.1 m NaOH for 10 min and added directly to the prehybridization buffer. The probe was allowed to hybridize to its target sequence overnight at 65°C. Nonspecific binding was removed by successive 10-min washes in 2× SSC/0.1% SDS (w/v), 0.2% SSC/0.1% SDS (w/v), and 0.1% SSC/0.1% SDS (w/v; all at room temperature) followed by 0.1% SSC/0.1% SDS (w/v) at 65°C. Hybridizing bands were visualized by exposure to radiographic film (Kodak).

Identification of Genomic DNA Flanking the AT T-DNA

Identification of the T-DNA insertion site in the AT23061 lines in Arabidopsis was determined by TAIL-PCR as described (Liu and Whittier, 1995). Genomic DNA was prepared with a DNA extraction kit (Qiagen). Two rounds of PCR amplification were used to isolate the DNA flanking the T-DNA insertion. A total of 15 pmol of the left border T-DNA primer L1 (5′-GACAACATTGTCGAGGCAGCAGGA-3′) was used with 150 pmol of the partially degenerate primer AD-2 (5′-NGTCGASWGANAWGAA-3′) for the first PCR. Conditions for the first reaction were as follows: (1) 95°C for 4 min; (2) 94°C for 15 s; (3) 65°C for 30 s; (4) 72°C for 1 min; (5) repeat five additional cycles of steps 2 through 4; (6) 94°C for 15 s; (7) 25°C for 3 min; (8) ramp to 72°C over 3 min; (9) 72°C for 3 min; (10) 94°C for 15 s; (11) 65°C for 30 s; (12) 72°C for 1 min; (13) repeat one additional cycle of steps 10 through 13; (14) 94°C for 10 s; (15) 44°C for 1 min; (16) 72°C for 1 min; (17) repeat 14 additional cycles of steps 10 through 16; (18) 72°C for 3 min; and (19) 4°C until needed. DNA produced in the first PCR was diluted 1:50, and 1 μL of this dilution was used for the second round of PCR. A total of 15 pmol of the left border nested primer L2 (5′-TGGACGTGAATGTAGACACGTCGA-3′) was used with 15 pmol of AD-2 for amplification. The PCR cycle conditions were as follows: (1) 95°C for 5 min; (2) 94°C for 15 s; (3) 61°C for 30 s; (4) 72°C for 1 min; (5) repeat one additional cycle of steps 2 through 4; (6) 94°C for 15 s; (7) 44°C for 1 min; (8) 72°C for 1 min; (9) repeat 17 additional cycles of steps 2 through 8; (10) 72°C for 4 min; and (11) 4°C until needed. The resulting PCR products were sequenced with the L3 primer (5′-TTGGTAATTACTCTTTCTTTTCCTCC-3′).

Gene Expression by RT-PCR and Real-Time PCR

For expression analysis, approximately 100 mg of fresh leaf tissues was harvested and frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted with the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen). Crude RNA preparations were treated with 10 units of RNase-free DNase I (Promega) and further purified according to the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit protocol. For RT-PCR studies, cDNA was synthesized from 1.5 μg of DNA-free RNA template using an oligo(dT) primer and SuperScript Reverse Transcriptase (Ambion). One-tenth volume of each cDNA was used as a template for PCR amplification. To determine whether comparable amounts of RNA had been used, β-ATPase or Actin2 primers were used as control (Kinoshita et al., 1992). PCRs were conducted using the following thermal profile: denaturation at 94°C for 4 min; followed by 25 to 30 cycles of 94°C for 45 s, 50°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 1 min; with a 10-min terminal extension step at 72°C. The number of PCR cycles for the transcripts investigated was determined by testing between 18 and 30 to the linear range. PCR products were detected on 1.0% agarose gels infiltrated with ethidium bromide. Real-time PCR was performed on an optical 96-well plate with an ABI PRISM 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Each reaction contained 12.5 μL of 2× SYBR Green Master Mix reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1.0 μL of cDNA samples, and 200 nm gene-specific primer in a final volume of 25 μL. The thermal cycle used was as follows: 95°C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 35 s. Gene-specific primer pairs were designed with Beacon Designer 7.0 (Premier Biosoft International): for AMR1 (At1g65770), 5′-TTCACAAAGGGCAAACATACG-3′ and 5′-CACAACATTCCACAAGTCTCC-3′; for GMP (At2g39770), 5′-TTGTTGACGAAACCGCTAC-3′ and 5′-TGCCACCCGATGATACTG-3′; for VTC2 (At4g26850), 5′-CAATGTTAGTCCGATAGAGTATGG-3′ and 5′-TGTAACCGAGTCTGAAGTATGG-3′; for GPP (At3g02870), 5′-ACATTAGACGATACAACCAACAG-3′ and 5′-GCTTCTTTCACGATAACAATTCC-3′; for VTC5 (At5g55120), 5′-AATGTGAGTCCGATTGAGTATGG-3′ and 5′-AGTAAGCCTGAAAGTGAAGATGG-3′; for GME (At5g28840), 5′-CGATGAGTGTGTTGAAGG-3′ and 5′-AGATTGTTGTCTGAGTTACG-3′; for GalDH (At4g33670), 5′-GGTGTGGGTGTGATAAGTG-3′ and 5′-GACGAAATCTCCTTGTTTGC-3′; for GLDH (At3g47930), 5′-CAGCAGATTGGTGGTATTATTC-3′ and 5′-GACCTCAGCAACAACTCC-3′; for MIOX4 (At4g26260), 5′-ATGAGGTTGTGGATGAGAG-3′ and 5′-TGTCAGAGAGGTTAATCAGATGG-3′); and for Actin2 (At3g18780) used as an internal control, 5′-GTATCGCTGACCGTATGAG-3′ and 5′-CTGCTGGAATGTGCTGAG-3′. Each PCR was performed in triplicate, and the experiments were repeated three times. Specificity was verified at the end of each PCR run using ABI Prism dissociation curve analysis software and also separating the PCR products by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel. Relative expression levels were first normalized to Actin2 expression and then to the respective wild-type controls with the 2−ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Reporter Gene Construct and GUS Activity Staining

The promoter (1 kb upstream of the start codon) of AMR1 was cloned from wild-type genomic DNA with primers FBPH-F (5′-CCAAGCTTCCCACAACACA-3′) and FBPN-R (5′-CCCATGGCATGGTTTCCT-3′) and fused with GUS in the binary vector pCAMBIA1301. The fusion construct was transferred into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 and transformed into plants by the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). Young seedlings or an entire leaf were incubated in staining solution (50 mm NaPO4, pH 7.0, 1% Triton X-100, and 0.1% bromochloroindolyl-β-glucuronide) by vacuum infiltrating the tissue for 5 min. Tissues were incubated overnight at 37°C. When visualizing results, chlorophyll was removed with 95% ethanol (rinsed several times) followed by a final rinse in 70% ethanol before viewing and photographing.

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession number NM_105250.

This work was supported by the Interagency Metabolic Engineering Program (National Science Foundation IPB/MCB grant no. 4–27128 and U.S. Department of Agriculture National Research Initiative Competitive Grants Program grant no. 4–28902).

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Craig L. Nessler (cnessler@vt.edu).

Open Access articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Agius F, Amaya I, Botella MA, Valpuesta V (2005) Functional analysis of homologous and heterologous promoters in strawberry fruits using transient expression. J Exp Biol 56 37–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agius F, González-Lamonthe R, Caballero JL, Muñoz-Blanco J, Botella MA, Valpuesta V (2003) Engineering increased vitamin C levels in plants by over-expression of a D-galacturonic acid reductase. Nat Biotechnol 21 177–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhagdow M, Mounet F, Gilbert L, Nunes-Nesi A, Garcia V, Just D, Petit J, Beauvoit B, Fernie AR, Rothan C, et al (2007) Silencing of the mitochondrial ascorbate synthesizing enzyme L-galactono-1,4-lactone dehydrogenase affects plants and fruit development in tomato. Plant Physiol 145 1408–1422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso JM, Stepanova AN, Leisse TJ, Ki CJ, Che H, Shinn P, Stevenson DK, Zimmerman J, Barajas P, Cheuk R, et al (2003) Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 301 653–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade MA, Perez-Iratxeta C, Ponting CP (2001) Protein repeats: structures, functions, and evolution. J Struct Biol 134 117–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrigoni O, DeTullio MC (2002) Ascorbic acid: much more than just an antioxidant. Biochim Biophys Acta 1569 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai C, Sen P, Hofmann K, Ma L, Goebl M, Harper JW, Elledge SJ (1996) SKP1 connects cell cycle regulators to the ubiquitin proteolysis machinery through a novel motif, the F-box. Cell 86 263–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth C, Moeder W, Klessig DF, Conklin PL (2004) The timing of senescence and response to pathogens is altered in the ascorbate-deficient Arabidopsis mutant vitamin c-1. Plant Physiol 134 1784–1792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoli CG, Guiamet JJ, Kiddle G, Pastori GM, Di Cagno R, Theodoulou FL, Foyer CH (2005) Ascorbate content of wheat leaves is not determined by maximal L-galactono-1,4-lactono dehydrogenase (GalLDH) activity under drought stress. Plant Cell Environ 28 1073–1081 [Google Scholar]

- Bartoli CG, Yu J, Gómez F, Fernández L, McIntosh L, Foyer CH (2006) Inter-relationships between light and respiration in the control of ascorbic acid biosynthesis and accumulation in Arabidopsis thaliana leaves. J Exp Bot 57 1621–1631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A, Coin L, Durbin R, Finn RD, Hollich V, Griffiths-Jones S, Khanna A, Marshall M, Moxon S, Sonnhammer ELL, et al (2004) The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res 32 D138–D141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busino L, Bassermann F, Maiolica A, Lee C, Nolan PM, Godinho SI, Draetta GF, Pagano M (2007) SCFFbxl3 controls the oscillation of the circadian clock by directing the degradation of cryptochrome proteins. Science 316 900–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Gallie DR (2005) Increasing tolerance to ozone by elevating foliar ascorbic acid confers greater protection against ozone than increasing avoidance. Plant Physiol 138 1673–1689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Young TE, Ling J, Chang SC, Gallie DR (2003) Increasing vitamin C content of plants through enhanced ascorbate recycling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100 3525–3530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZH, Jenkins GI, Nimmo HG (2008) Identification of an F box protein that negatively regulates Pi starvation responses. Plant Cell Physiol 49 1902–1906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 16 735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin PL (1998) Vitamin C: a new pathway for an old antioxidant. Trends Plant Sci 3 329–330 [Google Scholar]

- Conklin PL, Barth C (2004) Ascorbic acid, a familiar small molecule intertwined in the response of plants to ozone, pathogens, and the onset of senescence. Plant Cell Environ 27 959–970 [Google Scholar]

- Conklin PL, Norris SR, Wheeler GL, Williams EH, Smirnoff N (1999) Genetic evidence for the role of GDP-mannose in plant ascorbic acid (vitamin C) biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96 4198–4203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin PL, Pallanca JE, Last RL, Smirnoff N (1997) l-Ascorbic acid metabolism in the ascorbate-deficient Arabidopsis mutant vtc1. Plant Physiol 115 1277–1285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig KL, Tyers M (1999) The F-box: a new motif for ubiquitin dependent proteolysis in cell cycle regulation and signal transduction. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 72 299–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey MW, van Montagu M, Sanmatin M, Kanellis A, Smirnoff N, Benzie IJJ, Strain JJ, Favell D, Fletcher J (2000) Plant L-ascorbic acid: chemistry, function, metabolism, bioavailability and effects of processing. J Sci Food Agric 80 825–860 [Google Scholar]

- Davletova S, Rizhsky L, Liang H, Shengqiang Z, Oliver DJ, Coutu J, Shulaev V, Schlauch K, Mittler R (2005) Cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase 1 is a central component of the reactive oxygen gene network of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17 268–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Pozo JC, Estelle M (2000) F-box proteins and protein degradation: an emerging theme in cellular regulation. Plant Mol Biol 44 123–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Tullio MC, Arrigoni O (2004) Hopes, disillusions and more hopes from vitamin C. Cell Mol Life Sci 61 209–219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Haese D, Vandermeiren K, Asard H, Horemans N (2005) Other factors than apoplastic ascorbate contribute to the differential ozone tolerance of two clones of Trifolium repens L. Plant Cell Environ 28 623–632 [Google Scholar]

- Dowdle J, Ishikawa T, Gatzek S, Rolinski S, Smirnoff N (2007) Two genes in Arabidopsis thaliana encoding GDP-L-galactose phosphorylase are required for ascorbate biosynthesis and seedling viability. Plant J 52 673–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freebairn HT (1960) The prevention of air pollution damage to plants by the use of vitamin C sprays. J Air Pollut Control Assoc 10 314–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagne JM, Downes BP, Shiu SH, Durski AM, Vierstra RD (2002) The F-box subunit of the SCF E3 complex is encoded by a diverse superfamily of genes in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99 11519–11524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatzek S, Wheeler GL, Smirnoff N (2002) Antisense suppression of L-galactose dehydrogenase in Arabidopsis thaliana provides evidence for its role in ascorbate synthesis and reveals light modulated L-galactose synthesis. Plant J 30 541–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MA, Fry SC (2005) Vitamin C degradation in plant cells via enzymatic hydrolysis of 4-O-oxalyl-L-threonate. Nature 433 83–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai T, Karita S, Shiratori G, Hattori M, Nunome T, Oba K, Hirai M (1998) L-Galactono-gamma-lactone dehydrogenase from sweet potato: purification and cDNA sequence analysis. Plant Cell Physiol 39 1350–1358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai T, Kingston-Smith AH, Foyer CH (1999) Ascorbate metabolism in potato leaves supplied with exogenous ascorbate. Free Radic Res 31 S171–S179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller R, Springer F, Renz A, Kossmann J (1999) Antisense inhibition of the GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase reduces the ascorbate content in transgenic plants leading to developmental changes during senescence. Plant J 19 131–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T, Imamura J, Nagai H, Shimotohno K (1992) Quantification of gene expression over a wide range by the polymerase chain reaction. Anal Biochem 206 231–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh I (2002) Acclimative response to temperature stress in higher plants: approaches of gene engineering for temperature tolerance. Annu Rev Plant Biol 53 225–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Paietta JV (1998) An additional role for the F-box motif: gene regulation within the Neurospora crassa sulfur control network. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95 2417–2422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laing WA, Bulley S, Wright M, Cooney J, Jensen D, Barraclough D, MacRae E (2004) A highly specific L-galactose-1-phosphate phosphatase on the path to ascorbate biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101 16976–16981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laing WA, Wright MA, Cooney J, Bulley SM (2007) The missing step if the L-galactose pathway of ascorbate biosynthesis in plants, an L-galactose guanyltransferase, increases leaf ascorbate content. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104 9534–9539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechner E, Achard P, Vansiri A, Potuschak T, Genschik P (2006) F-box proteins everywhere. Curr Opin Plant Biol 9 631–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I, Copley RR, Schmidt S, Ciccarelli FD, Doerks T, Schultz J, Ponting CP, Bork P (2004) SMART 4.0: towards genomic data integration. Nucleic Acids Res 32 D142–D144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linster CL, Adler LN, Webb K, Christensen KC, Brenner C, Clarke SG (2008) A second GDP-L-galactose phosphorylase in Arabidopsis en route to vitamin C. J Biol Chem 283 18483–18492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linster CL, Clarke SG (2008) L-Ascorbate biosynthesis in higher plants: the role of VTC2. Trends Plant Sci 13 567–573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linster CL, Gomez TA, Christensen KC, Adler LN, Young BD, Brenner C, Clarke SG (2007) Arabidopsis VTC2 encodes a GDP-L-galactose phosphorylase, the last unknown enzyme in the Smirnoff-Wheeler pathway to ascorbic acid in plants. J Biol Chem 282 18879–18885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YG, Whittier RF (1995) Thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR: automatable amplification and sequencing of insert end fragments from P1 and YAC clones for chromosome walking. Genomics 25 674–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorence A, Chevone BI, Mendes P, Nessler C (2004) myo-Inositol oxygenase offers a possible entry point into plant AsA biosynthesis. Plant Physiol 134 1200–1205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddison J, Lyons T, Plochl M, Barnes J (2002) Hydroponically cultivated radish fed L-galactono-1,4-lactone exhibit tolerance to ozone. Planta 214 383–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major LL, Wolucka BA, Naismith JH (2005) Structure and function of GDP-mannose-3′,5′-epimerase: an enzyme which performs three chemical reactions at the same active site. J Am Chem Soc 127 18309–18320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon J, Parry G, Estelle M (2004) The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and plant development. Plant Cell 16 3181–3195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Moulé P (2008) An expression analysis of the ascorbate biosynthesis enzyme VTC2. Plant Mol Biol 68 31–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navabpour S, Morris K, Allen R, Harrison EA, Mackerness S, Buchanan-Ni W, Xie D, Hobbie L, Feng B, Zhao D, et al (2004) Regulation of flower development in Arabidopsis by SCF complexes. Plant Physiol 134 1574–1585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni W, Xie D, Hobbie L, Feng B, Zhao D, Akkara J, Ma H (2004) Regulation of flower development in Arabidopsis by SCF complexes. Plant Physiol 134 1574–1585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noctor G, Foyer CH (1998) Ascorbate and glutathione: keeping active oxygen under control. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 49 249–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualini S, Della Torre G, Ferranti F, Ederli L, Piccioni C, Reale L, Antonielli M (2002) Salicylic acid modulates ozone-induced hypersensitive cell death in tobacco plants. Physiol Plant 115 204–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton EE, Willems AR, Tyers M (1998) Combinatorial control in ubiquitin dependent proteolysis: don't Skp the F-box hypothesis. Trends Genet 14 236–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignocchi C, Fletcher JM, Wilkinson JE, Barnes JD, Foyer CH (2003) The function of ascorbate oxidase in tobacco. Plant Physiol 132 1631–1641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potuschak T, Lechner E, Parmentier Y, Yanagisawa S, Grava S, Koncz C, Genschik P (2003) EIN3-dependent regulation of plant ethylene hormone signaling by two Arabidopsis F box proteins: EBF1 and EBF2. Cell 115 679–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao M, Ormrod DP (1995) Ozone pressure decreases UVB sensitivity in a UVB-sensitive flavonoid mutant of Arabidopsis. Photochem Photobiol 61 71–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki-Sekimoto Y, Taki N, Obayashi T, Aono M, Matsumoto F, Sakurai N, Susuki H, Hirai MY, Noji M, Saito K, et al (2005) Coordinated activation of metabolic pathways for antioxidants and defense compounds by jasmonates and their roles in stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant J 44 653–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz J, Milpetz F, Bork P, Ponting CP (1998) SMART, a simple modular architecture research tool: identification of signaling domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95 5857–5864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnoff N (1996) The function and metabolism of ascorbic acid in plants. Ann Bot (Lond) 78 661–669 [Google Scholar]

- Smirnoff N (2000) Ascorbate biosynthesis and function in photoprotection. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 355 1455–1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnoff N, Conklin PL, Loewus FA (2001) Biosynthesis of ascorbic acid in plants: a renaissance. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 52 437–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnoff N, Wheeler GL (2000) Ascorbic acid in plants: biosynthesis and function. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 35 291–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabata K, Takaoka T, Esaka M (2002) Gene expression of ascorbic acid-related enzymes in tobacco. Phytochemistry 61 631–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaoki M, Mukai F, Asai N, Nakajimi N, Kubo A, Aono M, Saji H (2003) Light-controlled expression of a gene encoding L-galactono-lactone dehydrogenase which affects ascorbate pool size in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Sci 16 1111–1117 [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K, Suzuki K, Kitamura S (2006) Characterization of a GDP-D-mannose-3′,5′-epimerase from rice. Phytochemistry 67 338–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel D, Ahn JH, Blazquez MA, Borevitz JO, Christensen SK, Fankhauser C, Ferrandiz C, Kardailsky I, Malancharuvil EJ, Neff MM, et al (2000) Activation tagging in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 122 1003–1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler GL, Jones MA, Smirnoff N (1998) The biosynthetic pathway of vitamin C in higher plants. Nature 393 365–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolucka BA, Goossens A, Inzé D (2005) Methyl jasmonate stimulates the de novo biosynthesis of vitamin C in plant cell suspensions. J Exp Bot 56 2527–2538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolucka BA, Van Montagu M (2003) GDP-mannose-3′,5′-epimerase forms GDP-L-gulose, a putative intermediate for the de novo biosynthesis of vitamin C in plants. J Biol Chem 278 47483–47490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolucka BA, Van Montagu M (2007) The VTC2 cycle and the de novo biosynthesis pathways for vitamin C in plants: an opinion. Phytochemistry 68 2602–2613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo HR, Chung KM, Park JH, Oh SA, Ahn T, Hong SH, Jang SK, Nam HG (2001) ORE9, an F-box protein that regulates leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 13 1779–1790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao WY, Jang JC (2000) F-box proteins in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci 5 454–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabuta Y, Maruta T, Nakamura A, Mieda T, Yoshimura K, Ishikawa T, Shigeoka S (2008) Conversion of L-galactono-1,4-lactone to L-ascorbate is regulated by the photosynthetic electron transport chain in Arabidopsis. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 72 2598–2607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabuta Y, Mieda T, Rapolu M, Nakamura A, Motoki T, Maruta T, Yoshimura K, Ishikawa T, Sigeoka S (2007) Light regulation of ascorbate biosynthesis is dependent on the photosynthetic electron transport chain but independent of sugars in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot 58 2661–2671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Gruszewski HA, Chevone BI, Nessler CL (2008) An Arabidopsis purple acid phosphatase with phytase activity increases foliar ascorbate. Plant Physiol 146 431–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]