Abstract

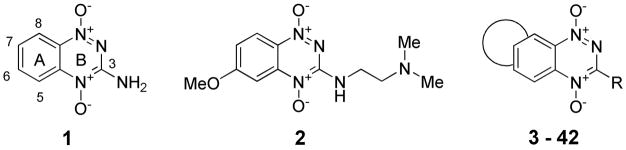

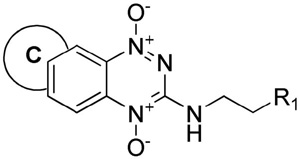

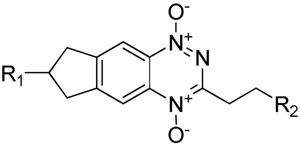

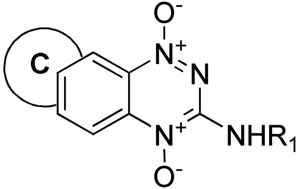

A series of novel tricyclic triazine-di-N-oxides (TTOs) related to tirapazamine have been designed and prepared. A wide range of structural arrangements with cycloalkyl, oxygen- and nitrogen-containing saturated rings fused to the triazine core, coupled with various side chains linked to either hemisphere, resulted in TTO analogues that displayed hypoxia-selective cytotoxicity in vitro. Optimal rates of hypoxic metabolism and tissue diffusion coefficients were achieved with fused cycloalkyl rings in combination with both the 3-aminoalkyl or 3-alkyl substituents linked to weakly basic soluble amines. The selection was further refined using pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model predictions of the in vivo hypoxic potency (AUCreq) and selectivity (HCD) with 12 TTO analogues predicted to be active in vivo, subject to the achievement of adequate plasma pharmacokinetics.

Introduction

The increasingly well defined role of tumor hypoxia in driving tumor metabolism, progression, invasion and metastasis,1–7 as well as resistance to therapy,8–13 emphasizes the cogent need for clinical agents that selectively target hypoxia.14,15

One class of hypoxia-selective cytotoxins under development is the benzotriazine 1,4-dioxides (BTOs) represented by the archetype tirapazamine (1, TPZ).16,17 TPZ acts as a prodrug that undergoes selective bioreductive activation18 under hypoxic conditions to ultimately form an oxidising radical that may react with DNA,19–22 leading to DNA strand breaks and poisoning of topoisomerase II.23–27 TPZ shows selective toxicity to hypoxic cells in vitro and in experimental tumours,17,28–31 and a range of clinical trials have produced modest therapeutic results to date.32–34 This approach, using TPZ to selectively kill hypoxic cells in tumors, is an early example of “physiologically-targeted therapy.” Recent prognostic data35,36 from a clinical trial in head and neck cancer37 has highlighted the importance of preselecting patients with hypoxia when using such a targeted therapy and this may in part explain the modest results with TPZ in trials.

TPZ has limitations that blunt its efficacy in vivo and, potentially, in the clinic. It displays lower hypoxic selectivity in vivo (2 to 3-fold) compared to in vitro (hypoxic cytotoxicity ratio, HCR, ca. 50 to100-fold),38 which has been ascribed to rapid metabolism of TPZ in hypoxic tissues, leading to limited penetration of the drug into hypoxic tissue.39–45

Overcoming this limited extravascular transport (EVT) requires balancing the rate of bioreductive metabolism relative to the tissue diffusion coefficient: analogues with low rates of bioreductive metabolism lack cytotoxic potency, while analogues with high rates of metabolism suffer limited EVT due to excessive consumption of the prodrug.40,46–49 Optimisation of EVT is but one element required in maximizing activity against hypoxic cells in tumors. We have recently demonstrated a spatially-resolved pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) model that integrates hypoxic cytotoxicity and selectivity, EVT, and plasma pharmacokinetics to successfully predict in vivo activity against hypoxic cells in HT2945 and SiHa tumors.46 We have applied this model to guide drug synthesis and testing in two studies of BTO analogues and identified several BTOs with improved activity against hypoxic cells in vivo.48,49

We initially determined structure-activity relationships (SAR) between A-ring substituents and one-electron reduction potential [E(1)], hypoxic cytotoxicity and hypoxic selectivity,50 but issues of aqueous solubility and EVT were not addressed directly in this study. Another study of neutral BTOs demonstrated an increase in tissue diffusion coefficients, measured using multicellular layer (MCL) cultures, of analogues with increased lipophilicity.47 Recently we reported48 a systematic evaluation of 3-aminoalkylamino BTOs, seeking analogues with improved aqueous solubility and EVT. This study showed that electron-donating substituents in the 6-position could be used to counteract increased rates of metabolism caused by the 3-aminoalkylamino substituents, e.g., 2, and demonstrated that sufficiently lipophilic analogues provide MCL penetration similar to TPZ and show activity against hypoxic cells in tumor xenografts. A subsequent study49 demonstrated that removal of hydrogen bond donors at the 3-position could further increase tissue diffusion coefficients, but that the less electron-donating 3-alkyl substituents raised reduction potentials and hypoxic metabolism, which could be counteracted by adding electron-donating substituents to the A-ring. Several BTO analogues with improved in vivo activity relative to TPZ were identified in these studies.

However these findings, and the limited SAR studies by others51–55 have all been on analogues based on the 1,2,4-benzotriazine 1,4-dioxide core. With the exception of several studies on the parent 1,2,4-triazine dioxides,56,57 and isosteric cyanoquinoxaline 1,4-dioxides,58–61 there has been little exploration of related heterocyclic dioxides as hypoxia-selective cytotoxins. In this study we have synthesized 40 novel tricyclic triazine 1,4-dioxides (TTOs) 3–42 and examined their in vitro activity as hypoxia-selective cytotoxins. We have focussed on using lipophilic ring systems of an electron-donating nature in an effort to increase EVT by more rapid diffusion through tumour tissue and reduced rates of hypoxic metabolism. We have used in vitro PK/PD modelling to assess the effect of the structural changes on EVT and this approach has identified twenty novel TTOs of diverse structure with promising in vitro profiles as hypoxia-selective cytotoxins.

Chemistry

Synthesis

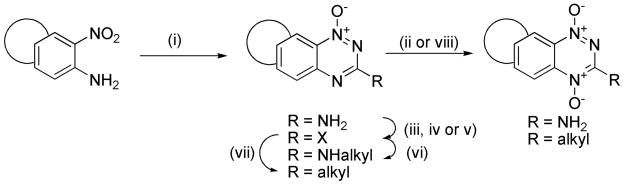

Our synthetic strategies build on well established methodology for the formation of the 3-amino-1,2,4-benzotriazine 1-oxide core48,50 and elaboration to 3-alkyl analogues62,63 and these general methods are described below. Bicyclic nitroanilines were treated with cyanamide and cHCl to generate the intermediate guanidines, which were cyclised under strongly basic conditions to give 3-aminotriazine 1-oxides (Scheme 1). Oxidation of 3-aminotriazine 1-oxides to 3-amino TTOs was achieved with peracetic acid. Conversion of 3-aminotriazine 1-oxides to 3-chlorotriazine 1-oxides was achieved by diazotization in trifluoroacetic acid, followed by chlorination of the intermediate phenol. Displacement of 3-chlorides with a variety of amines gave the 3-aminoalkyltriazine 1-oxides. 3-Aminotriazine 1-oxides were also converted to 3-iodides by diazotization with tBuNO2 in THF and iodination with CH2I2. Reaction of 3-halotriazines with various stannanes using Stille conditions gave 3-alkyltriazine 1-oxides. Alternatively, reaction of 3-iodides with allyl alcohol under Heck conditions gave 3-alkyltriazine 1-oxides. Oxidation of 3-substituted triazine 1-oxides with trifluoroperactic acid, using an excess of trifluoroacetic acid to protect any aliphatic amines present, gave a variety of TTOs.

Scheme 1a.

aReagents: (i) NH2CN, HCl, Δ; then 30% NaOH, Δ; (ii) CH3CO3H, CH3CO2H; (iii) NaNO2, CF3CO2H; (iv) DMF, POCl3, Δ; (v) t-BuNO2, CH2I2, CuI, THF, Δ; (vi) R2CH2CH2NH2, DME, Δ; (vii) Stille or Heck coupling; (viii) CF3CO3H, CF3CO2H, DCM.

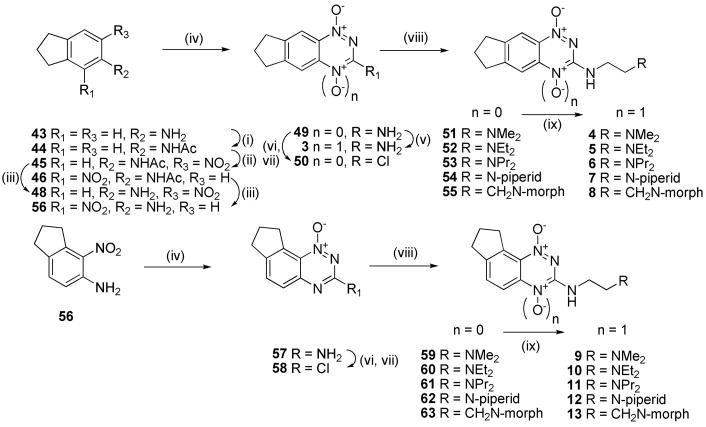

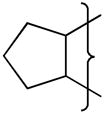

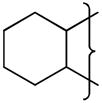

In particular, our first set of targets included cyclopentane-, cyclohexane- and cycloheptane-fused benzotriazine dioxides with a range of 3-aminoalkyl substituents bearing solubilising side chains. Thus, acetylation of 5-aminoindane (43) gave acetamide 44, which was nitrated to give isomeric nitroacetamides 45–47 (Scheme 2). Deprotection of nitroacetamide 45 under acidic conditions gave nitroaniline 48 which underwent Arndt cyclisation to give 1-oxide 49 which was oxidized to TTO 3. The 1-oxide 49 was converted to the 3-chloride 50 and this underwent displacement with a series of lipophilic aminoalkylamines to give 1-oxides 51–55, which were oxidized to the corresponding TTOs 4–8.

Scheme 2a.

aReagents: (i) Ac2O, dioxane; (ii) KNO3, H2SO4; (iii) 5 M HCl, Δ; (iv) NH2CN, HCl, Δ; then 30% NaOH, Δ; (v) CH3CO3H, CH3CO2H; (vi) NaNO2, CF3CO2H; (vii) DMF, POCl3, Δ; (viii) RCH2CH2NH2, DME, Δ; (ix) CF3CO3H, CF3CO2H, DCM.

A similar sequence of reactions was carried out using the angular nitroacetamide isomer 46. Deprotection gave nitroaniline 56 which was converted to 1-oxide 57 and then to 3-chloride 58, which was elaborated to a series of 3-aminoalkyl 1-oxides 59–63 and oxidized to TTOs 9–13, respectively.

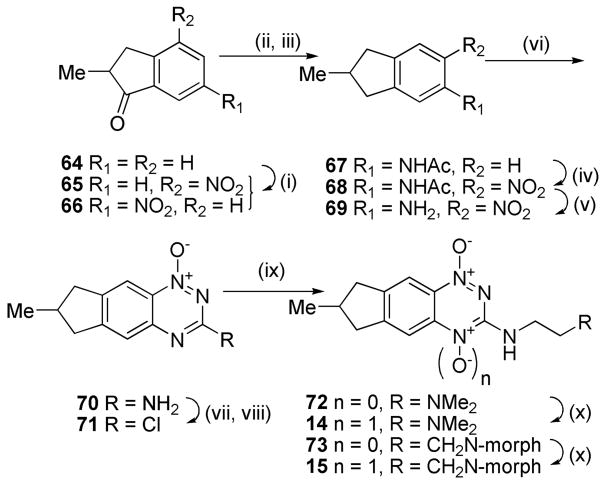

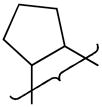

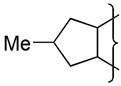

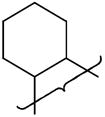

Access to the methylcyclopentane analogues 14 and 15 was accomplished by elaboration of 2-methylindanone 64 (Scheme 3). Nitration gave 4- and 6-nitroisomers 65 and 66. Reduction and acetylation of 66 gave acetamide 67 which was nitrated to give nitroacetamide 68 and deprotected to nitroaniline 69. Cyclisation of 69 gave 1-oxide 70 which was diazotized and chlorinated to 3-chloride 71. Displacement with amines gave 72 and 73 which were oxidized to TTOs 14 and 15, respectively.

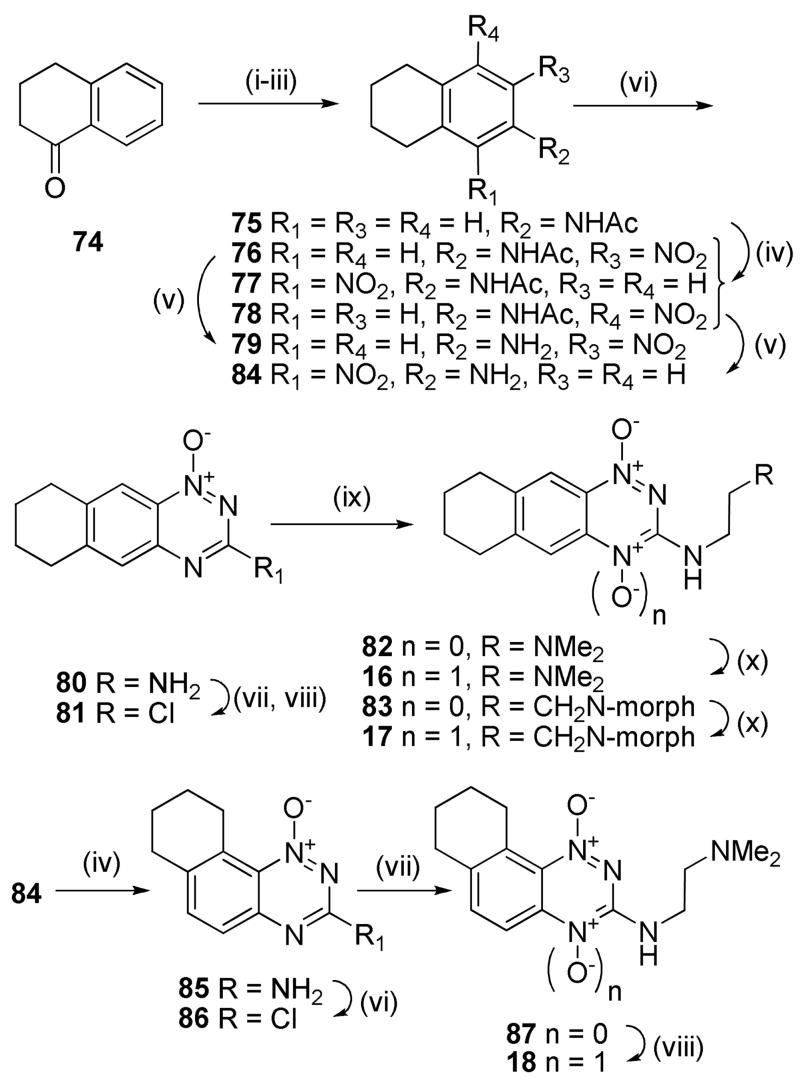

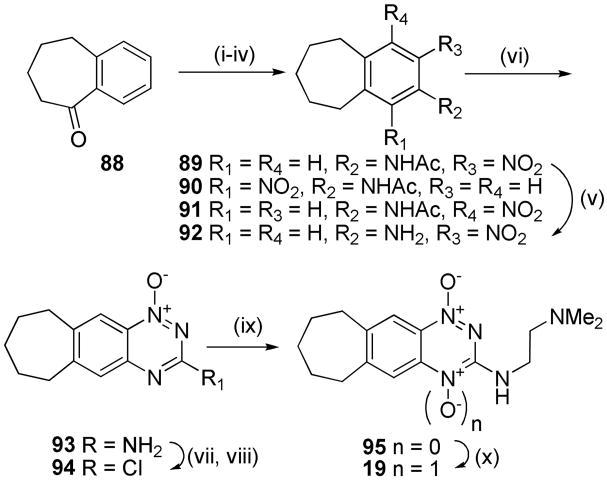

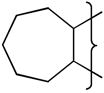

Similar sequences were followed to elaborate α-tetralone (74) to linear tricyclic 1,4-dioxides 16, 17 and the angular analogue 18 (Scheme 4), as well as to convert benzosuberone (88) to the cycloheptane TTO 19 (Scheme 5).

Scheme 4a.

aReagents: (i) fHNO3, H2SO4; (ii) H2, Pd/C, cHCl, EtOH; (iii) Ac2O, dioxane; (iv) KNO3, H2SO4; (v) 5 M HCl, Δ; (vi) NH2CN, HCl, Δ; then 30% NaOH, Δ; (vii) NaNO2, CF3CO2H; (viii) DMF, POCl3, Δ; (ix) RCH2CH2NH2, DME, Δ; (x) CF3CO3H, CF3CO2H, DCM.

Scheme 5a.

aReagents: (i) fHNO3, cH2SO4; (ii) H2, Pd/C, cHCl, EtOH; (iii) Ac2O, dioxane; (iv) KNO3, H2SO4; (v) 5 M HCl, Δ; (vi) NH2CN, HCl, Δ; then 30% NaOH, Δ; (vii) NaNO2, CF3CO2H; (viii) DMF, POCl3, Δ; (ix) RCH2CH2NH2, DME, Δ; (x) CF3CO3H, CF3CO2H, DCM.

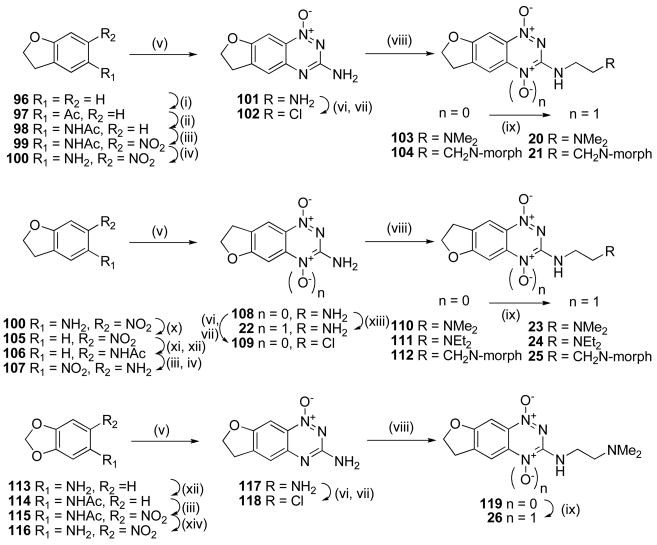

The use of alkoxy substituents to lower electron affinity has previously48,49 yielded active analogues, e.g., 2, thus a series of fused dihydrobenzofuran analogues were synthesized (Scheme 6). Friedel-Crafts acylation of dihydrobenzofuran (96) gave ketone 97 which was converted to the oxime and underwent Beckmann rearrangement to acetamide 98. Nitration gave nitroacetamide 99 which was deprotected to give nitroaniline 100. Conversion of 100 to the “[3,2-g]” 3-amino 1-oxide isomer 101 and subsequent chlorination gave 3-chloride 102, which underwent displacement with amines to give 1-oxides 103 and 104 which were oxidised to the TTOs 20 and 21, respectively.

Scheme 6a.

aReagents: (i) AlCl3, AcCl, DCM; (ii) NH2OH·HCl, pyridine; then HCl, Ac2O, HOAc; (iii) cHNO3, HOAc; (iv) cHCl, EtOH, Δ; (v) NH2CN, HCl, Δ; then 30% NaOH, Δ; (vi) NaNO2, CF3CO2H; (vii) DMF, POCl3, Δ; (viii) R2CH2CH2NH2, DME, Δ; (ix) CF3CO3H, CF3CO2H, DCM; (x) NaNO2, cH2SO4; then H3PO2 (xi) H2, PtO2, THF, EtOH; (xii) Ac2O, dioxane; (xiii) CH3CO3H, HOAc; (xiv) NaOMe, MeOH, Δ.

Access to the “[2,3-g]” isomer pattern was achieved by diazotisation of nitroaniline 100 in the presence of H3PO2, reduction of the resulting nitrobenzofuran 105 to the intermediate aniline and protection as the acetamide 106, nitration and deprotection to give nitroaniline 107. Cyclisation gave the isomeric BTO 1-oxide 108, which was directly oxidised to the 1,4-dioxide 22, or elaborated, via the chloride 109, to 3-aminoalkylamino 1-oxides 110–112 and subsequently to the corresponding TTOs 23–25.

The acetamide 114 of 3,4-methylenedioxoaniline (113) underwent nitration to give nitroacetamide 115 which was deprotected to give nitroaniline 116 (Scheme 6). Cyclisation of 116 gave the 1-oxide 117, which was converted to the 3-chloride 118, displaced with amine side chain to give 119 and oxidised to TTO 26.

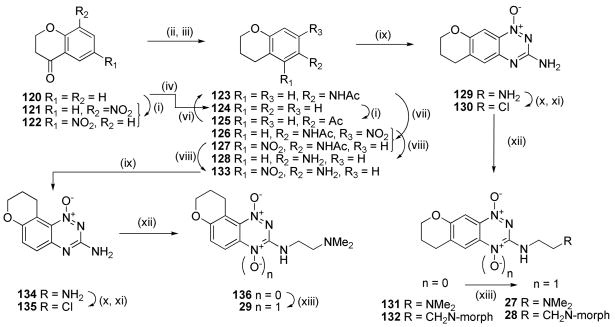

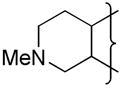

Nitration of 4-chromanone (120) gave predominantly the 6-nitro isomer 122, which was reduced and acetylated to give acetamide 123 in moderate (56%) yield (Scheme 7). Alternatively, zinc reduction of 120 gave chroman 124 which underwent Friedel-Crafts acylation to give 125 with subsequent oxime formation and Beckmann rearrangement to 123. Although lower yielding (41%), this route was more convenient on a large scale. Nitration of 123 gave ca. 1:1 ratio of the two isomeric nitroacetamides 126 and 127, which were deprotected to give corresponding nitroanilines 128 and 133. Cyclisation of 128 gave 1-oxide 129, which was converted, via chloride 130, to 1-oxides 131 and 132 and subsequently oxidised to 1,4-dioxides 27 and 28. A similar sequence converted the isomeric nitroaniline 133 to TTO 29.

Scheme 7a.

aReagents: (i) KNO3, cH2SO4; (ii) H2, Pd/C, aq. HCl, EtOAc/EtOH; (iii) Ac2O, dioxane; (iv) Zn, HOAc, Δ; (v) AlCl3, AcCl, DCM; (vi) NH2OH·HCl, pyridine; then HCl, Ac2O, HOAc; (vii) fHNO3, HOAc; (viii) cHCl, EtOH, Δ; (ix) NH2CN, HCl, Δ; then 30% NaOH, Δ; (x) NaNO2, CF3CO2H; (xi) DMF, POCl3, Δ; (xii) R2CH2CH2NH2, DME, Δ; (xiii) CF3CO3H, CF3CO2H, DCM.

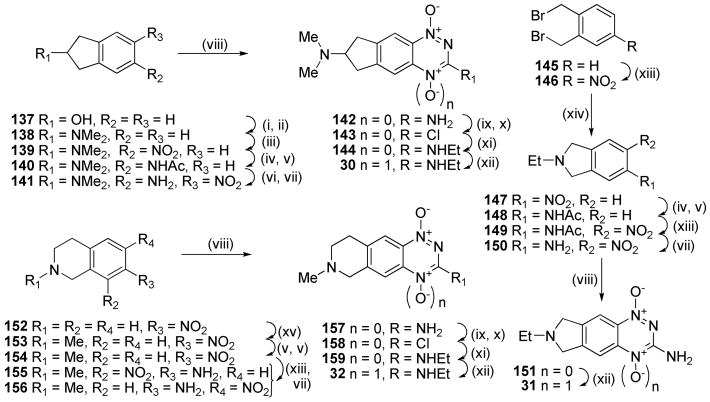

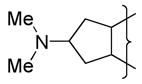

Recent work49 had shown that analogues with a soluble side chain appended to the benzo ring of BTOs displayed excellent hypoxic cytotoxicity and selectivity, so we explored analogues with solubilising functionality linked to, or part of, the saturated ring of the TTOs. Thus mesylation of 2-indanol (137) and displacement with dimethylamine gave amine 138, which was nitrated to give 5-nitroindanamine 139 (Scheme 8). Reduction and acetylation gave 140, nitration of which gave an inseparable mixture of nitroacetamide isomers. Deprotection and fractional crystallisation gave the single nitroaniline isomer 141 in 50% yield for the two steps. Cyclisation of 141 gave 1-oxide 142, which was converted to 3-chloride 143, displaced with ethylamine to give 3-amine 144 and selectively oxidised to TTO 30.

Scheme 8a.

aReagents: (i) MsCl, iPr2Net, DCM; (ii) aq. NHMe2, DMF, Δ; (iii) cHNO3, CF3CO2H; (iv) H2, Pd/C, aq. HCl, EtOAc/EtOH; (v) Ac2O, Et3N, DCM; (vi) fHNO3, HOAc; (vii) HCl, EtOH, Δ; (viii) NH2CN, HCl, Δ; then 30% NaOH, Δ; (ix) NaNO2, CF3CO2H; (iv) H2, Pd/C, aq. HCl, EtOAc/EtOH; (v) Ac2O, Et3N, DCM; (vi) fHNO3, HOAc; (vii) HCl, EtOH, Δ; (viii) NH2CN, HCl, Δ; then 30% NaOH, Δ; (ix) NaNO2, CF3CO2H; (x) DMF, POCl3, Δ; (xi) EtNH2, DME, Δ; (xii) CF3CO3H, CF3CO2H, DCM; (xiii) KNO3, cH2SO4; (xiv) EtNH2·HCl, Et3N, DMF, Δ; (xv) HCO2H, Ac2O, THF; then BH3·DMS.

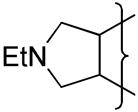

Nitration of bis(bromomethyl)benzene (145) gave 4-nitrobenzene 146 which was cyclised to 2-ethylisoindole 147. Reduction of 147 and acetylation gave acetamide 148 which was nitrated and deprotected to give nitroaniline 150. Cyclisation of 150 gave 1-oxide 151 which was oxidised to TTO 31. Reductive amination of 7-nitro-tetrahydroisoquinoline 152 with acetic formic anhydride gave 153. Reduction of the nitro group and protection gave acetamide 154, nitration of which gave an inseparable mixture of nitroacetamides. Deprotection allowed purification of the isomeric nitroanilines 155 and 156. Cyclisation of nitroaniline 156 gave 1-oxide 157 which was converted to TTO 32 in a similar manner to 142.

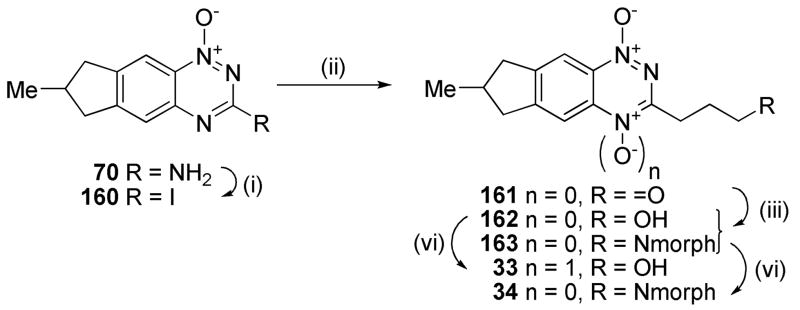

3-Alkyl BTOs displayed increased hypoxic potency compared to the analogous 3-aminoalkyl BTOs, but often had reduced aqueous solubility.49 In order to avoid this limitation with analogous TTOs we sought to maintain aqueous solubility by attaching a solubilising moiety via the 3-position or attached to the third (saturated) ring of the TTO. Diazotization of the 3-amino 1-oxide 70 and reaction with CH2I2 gave the iodide 160 which underwent a Heck reaction with allyl alcohol using Pd(OAc)2 as the catalyst to give aldehyde 161 (Scheme 9). Reductive amination with morpholine gave both the terminal alcohol 162 as well as the tertiary morpholide 163. Oxidation of alcohol 162 and amine 163 gave TTOs 33 and 34, respectively.

Scheme 9a.

aReagents: (i) t-BuNO2, CH2I2, CuI, THF, Δ; (ii) AllylOH, Pd(OAc)2, nBu4NBr, NaHCO3, DMF, Δ; (iii) morpholine, MeOH; then NaCNBH3, HOAc; (iv) CF3CO2H, CF3CO3H, DCM;

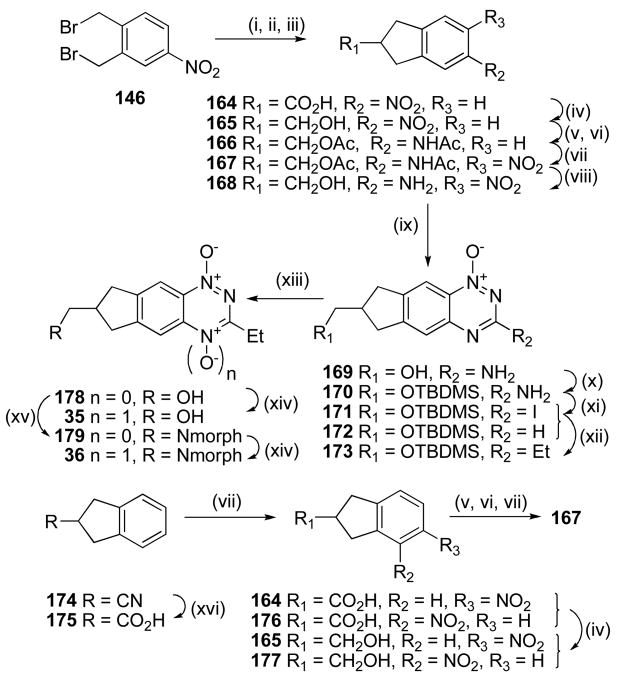

Two routes were explored to synthesize nitroaniline 168 (Scheme 10). Reaction of 1,2-bis(bromomethyl)-4-nitrobenzene (146) with diethyl malonate, with subsequent hydrolysis and decaboxylation giving indane-2-carboxylic acid 164, which was reduced to the corresponding alcohol 165, protected as the N,O-diacetyl compound 166 and nitrated to give nitroacetamide 167. Low yields in the first steps of this sequence prompted us to explore an alternative. Thus, hydrolysis of nitrile 174 gave the carboxylic acid 175, nitration of which gave an inseparable mixture of isomeric nitroindane 2-carboxylic acids 164 and 176. Reduction of this mixture gave a mixture of alcohols 165 and 177, which underwent further reduction, protection as the N,O-diacetyl compounds and subsequent nitration to give nitroacetamide 167 in 37% overall yield for the six steps. Deprotection of 167 gave nitroaniline 168 which was cyclised to 3-amino 1-oxide 169. Protection of 1-oxide 169 as the TBDMS ether 170 and iodination gave 3-iodide 171 which underwent Stille coupling with SnEt4 and Pd(PPh3)4 to give the 3-ethyl derivative 173. Oxidation and simultaneous deprotection of 173 gave TTO 35. The 3-ethyl silyl ether 173 was also deprotected to alcohol 178, and reaction with mesyl chloride and morpholine gave the tertiary amine 179. Selective aromatic N-oxidation of 179 gave TTO 36.

Scheme 10a.

aReagents: (i)NaH, (EtO2C)2CH2, Et2O; (ii) NaOH, EtOH; (iii) xylene, Δ; (iv) BH3·DMS, THF; (v) H2, Pd/C, MeOH; (vi) Ac2O, Et3N, DCM; (vii) cHNO3, CF3CO2H; (viii) 5 M HCl, MeOH, Δ; (ix) NH2CN, HCl, Δ; then 30% NaOH, Δ; (x) TBDMSCl, iPr2NEt, DMF; (xi) t-BuNO2, CH2I2, CuI, THF, Δ; (xii) Et4Sn, Pd(PPh3)4, DME, Δ; (xiii) 1 M HCl, MeOH, Δ; (xiv) CF3CO3H, DCM; (xv) MsCl, iPr2NEt, DCM; then morpholine, DMF, Δ; (xvi) cHCl, dioxane, Δ.

Similarly, Stille reaction of 171 with allyltributyltin gave alkene 180 which underwent hydroboration with 9-borabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane (9-BBN) to give the primary alcohol 181 (Scheme 11). Mesylation of 181 and displacement by morpholine gave amine 182 which was deprotected to alcohol 183 and oxidised to TTO 37.

Scheme 11a.

aReagents: (i) AllylSnBu3, Pd(PPh3)4, DME, Δ; (ii) 9-BBN, THF; then NaOAc, H2O2; (iii) MsCl, iPr2NEt, DCM; then morpholine, DMF; (iv) 1 M HCl, MeOH; (v) CF3CO3H, CF3CO2H,DCM.

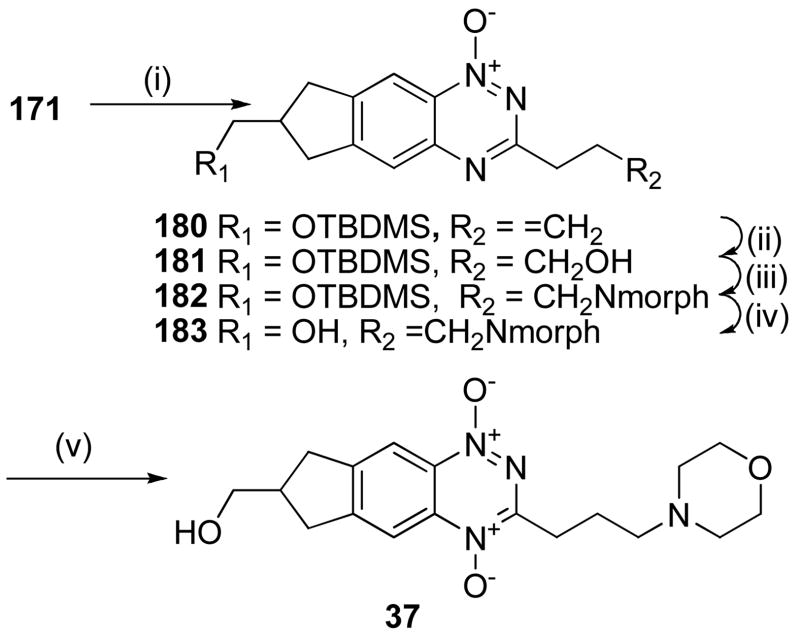

Condensation of indanone 184 with glyoxylic acid gave the enone acid 185 which was reduced to acid 186 (Scheme 12). Esterification of 186, reduction to the alcohol 188 with LiAlH4 and acetylation gave 189. Nitration of 189 gave a mixture of nitro isomers 190 and 191 which were reduced to the corresponding acetamides 192 and 193. Further nitration of the mixture gave the single isomer 194, which was deprotected to give nitroaniline 195. Cyclisation of 195 gave 1-oxide 196, which was diazotized and converted to the 3-iodide 197. Protection of the side chain as the THP ether 198 allowed Stille coupling to form 3-ethyl 1-oxide 199. Deprotection of the THP ether gave alcohol 200, which was oxidised to TTO 38. Alcohol 200 was further functionalised by reaction with mesyl chloride and morpholine to give morpholide 201 which was selectively oxidised to TTO 39.

Scheme 12a.

aReagents: (i) 50% aq. HCOCO2H, cH2SO4, dioxane, Δ; (ii) H2, Pd/C, MeOH, dioxane; (iii) cH2SO4, EtOH; (iv) LiAlH4, THF; (v) Ac2O, pyridine, DMAP, DCM; (vi) Cu(NO3)2·3H2O, Ac2O; (vii) Ac2O, dioxane; (viii) cHNO3, CF3CO2H; (ix)) 5 M HCl, MeOH, Δ; (x) NH2CN, HCl, Δ; then 30% NaOH, Δ; (xi) t-BuNO2, I2, CuI, THF, Δ; (xii) dihydropyran, PPTS, DCM; (xiii) Et4Sn, Pd(PPh3)4, DME, Δ; (xiv) MeSO3H, MeOH; (xv) CF3CO2H, CF3CO3H, DCM; (xvi) MsCl, iPr2NEt, DCM; then morpholine, DMF, Δ.

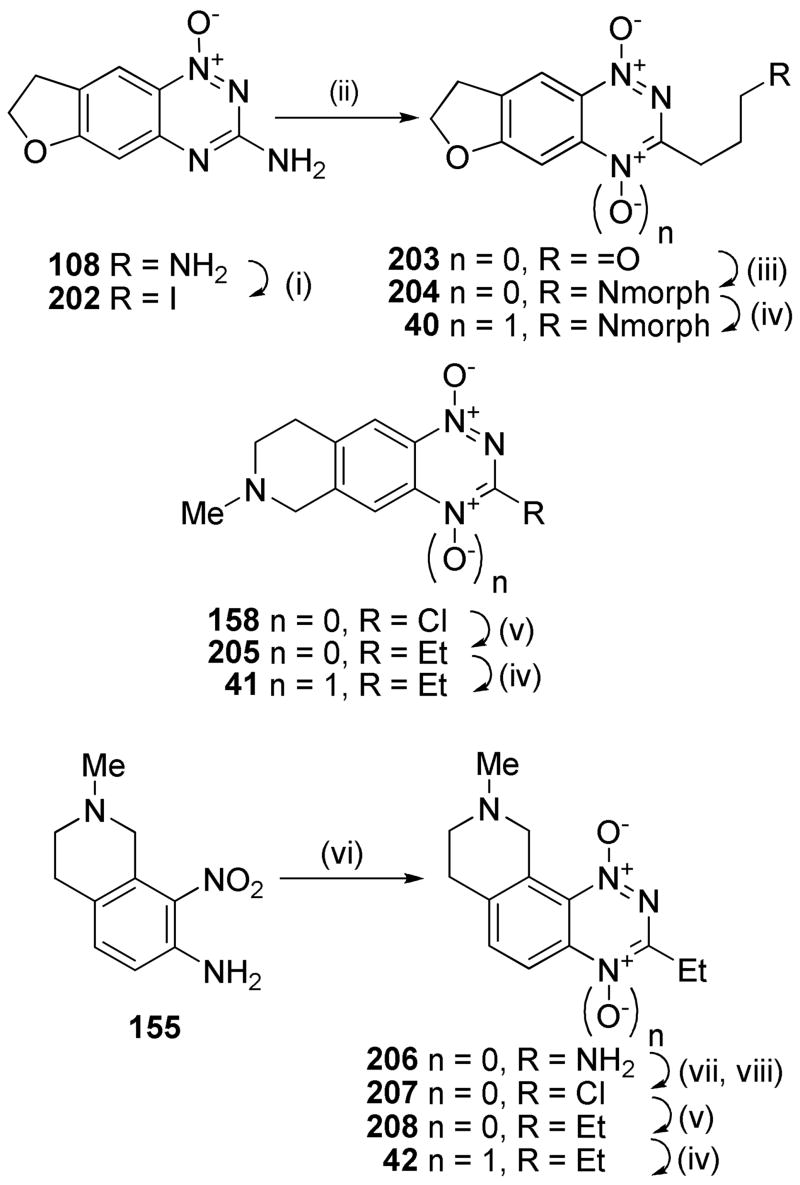

A series of 3-alkyl TTOs were also explored bearing heterocyclic saturated rings to potentially balance the effect of the 3-alkyl group on reduction potential and consequently rates of hypoxic metabolism. Conversion of dihydrofuran 1-oxide 108 to the iodide 109 followed by Heck coupling with allyl alcohol gave aldehyde 203 (Scheme 13). This aldehyde underwent reductive amination to give amine 204 which was oxidised to TTO 40. Stille reaction of the tetrahydroisoquinoline 3-chloride 158 gave the 3-ethyl 1-oxide 205 which was oxidised to TTO 41. Cyclisation of the nitroaniline 155 gave the 1-oxide 206 which was converted to the chloride 207. Stille coupling to gave 3-ethyl 1-oxide 208 which was oxidised to TTO 42.

Scheme 13a.

aReagents: (i) t-BuNO2, CH2I2, CuI, THF, Δ; (ii) Allyl alcohol, Pd(OAc)2, nBu4NBr, NaHCO3, DMF; (iii) morpholine, NaCNBH3, MeOH, DMF; (iv) CF3CO3H, CF3CO2H, DCM; (v) Et4Sn, Pd(PPh3)4, DME, Δ; (vi) NH2CN, HCl, Δ; then 30% NaOH, Δ; (vii) NaNO2, CF3CO2H; (viii) DMF, POCl3, Δ.

One electron reduction potential measurements, E(1)

Pulse radiolysis experiments were performed on The University of Auckland Dynaray 4 (4 MeV) linear accelerator (200 ns pulse length with a custom-built optical radical detection system).64 E(1) values for the TTOs were determined in anaerobic aqueous solutions containing 2-propanol (0.1 M) buffered at pH 7.0 (10 mM phosphate) by measuring the equilibrium constant for the electron transfer between the radical anions of the compounds and the appropriate viologen or quinone reference standard.65 Data were obtained at three concentration ratios at room temperature (22 ± 2 °C) and used to calculate the ΔE between the compounds and references, allowing for ionic strength effects on the equilibria.

Physicochemical Measurements

Solubilities of the TTOs 3–42 were determined in culture medium containing 5% fetal calf serum, at 22 °C. Octanol/water partition coefficients were measured at pH 7.4 (P7.4) for TPZ, 2 and a subset of four TTOs by a low volume shake flask method, with TTO concentrations in both the octanol and buffer phases analysed by HPLC as previously described.48,66 These values, in conjunction with previously determined values for related BTOs47–50 were used to “train” ACD LogP/LogD prediction software (v. 8.0, Advanced Chemistry Development Inc., Toronto, Canada) using a combination of ACD/LogP System Training and Accuracy Extender. Apparent (macroscopic) pKa values for the side chain were calculated using ACD pKa prediction software (v. 8.0, Advanced Chemistry Development Inc., Toronto, Canada).

Biological assays

Cytotoxic potency was determined by IC50 assays, using 4 h drug exposure of HT29 and SiHa cells under aerobic and anoxic (H2/Pd anaerobic chamber) conditions in 96 well plates as described previously.50 The hypoxic cytotoxicity ratio (HCR) was calculated as the intra-experiment ratio aerobic IC50/anoxic IC50 (Tables 1–3).

Table 1.

Physicochemical, in vitro and modelling parameters for TPZ, BTO 2 and TTOs 3–19.

| |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Ring C | R1 | pKaa | logP7.4 calcb | Sol.c mM | E(1) mV | HT29 IC50 hypox μM | HT29 HCRd | SiHa IC50 hypox μM | SiHa HCRd | D calce,f | kmetf,g min−1 | X½f,h μm | AUCreqi μM.min | HCDj |

| 1k | nal | nal | nal | −0.33 | 9 | −456 | 5.1 | 71 | 2.5 | 107 | 4.2 | 0.58 | 45 | 10200 | 4.1 |

| 2k | nal | NMe2 | 8.5 | −0.07 | 46 | −500 | 7.7 | 89 | 2.9 | 232 | 2.9 | 0.54 | 35 | 13800 | 2.7 |

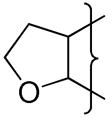

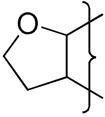

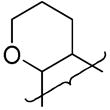

| 3 |

|

nal | 0.0 | 0.50 | 3 | 15.2 | 27 | 8.3 | 31 | 9.8 | 0.47 | 77 | 22100 | 6.3 | |

| 4 | NMe2 | 8.5 | 0.42 | >51 | −486 | 2.3 | 152 | 0.7 | 111 | 6.5 | 0.44 | 62 | 6730 | 6.4 | |

| 5 | NEt2 | 9.5 | 1.29 | 48 | 4.1 | 61 | 1.1 | 133 | 7.4 | 1.08 | 45 | 15300 | 3.9 | ||

| 6 | NPr2 | 8.7 | 0.69 | 20 | 2.5 | 77 | 0.7 | 91 | 19.3 | 1.07 | 72 | 7810 | 6.6 | ||

| 7 | N-piperidine | 8.7 | 1.45 | 1.9 | 5.8 | 49 | 1.3 | 143 | 11.7 | 1.25 | 52 | 3700 | 4.6 | ||

| 8 | CH2N-morpholine | 7.4 | 1.25 | 48 | 21.4 | 20 | 8.8 | 44 | 9.6 | 0.19 | 119 | 9860 | 9.9 | ||

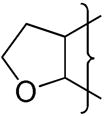

| 9 |

|

NMe2 | 8.5 | 0.18 | >54 | −480 | 3.0 | 67 | 1.6 | 99 | 8.3 | 0.74 | 57 | 7630 | 5.1 |

| 10 | NEt2 | 9.5 | 0.35 | >49 | 4.2 | 17 | 0.9 | 64 | 9.4 | 0.97 | 53 | 10000 | 5.6 | ||

| 11 | NPr2 | 8.7 | 1.60 | 40 | 12.4 | 7 | 3.3 | 23 | 19.3 | 0.73 | 87 | 13000 | 7.9 | ||

| 12 | N-piperidine | 8.7 | 0.65 | 36 | 4.9 | 53 | 1.0 | 51 | 11.9 | 1.60 | 46 | 13900 | 3.8 | ||

| 13 | CH2N-morpholine | 7.4 | 0.88 | 46 | −510 | 38 | 24 | 13.9 | 33 | 10.3 | 0.20 | 122 | 23000 | 10.0 | |

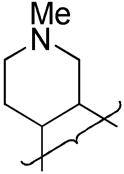

| 14 |

|

NMe2 | 8.5 | 0.42 | >49 | 3.5 | 54 | 1.4 | 97 | 10.2 | 1.49 | 44 | 11000 | 2.9 | |

| 15 | CH2N-morpholine | 7.4 | 1.29 | >49 | 19 | 25 | 8.4 | 50 | 13.8 | 0.13 | 173 | 13700 | 11.1 | ||

| 16 |

|

NMe2 | 8.5 | 0.69 | 12.8 | ||||||||||

| 17 | CH2N- morpholine | 7.4 | 1.45 | 49 | 6.3 | 25 | 2.6 | 54 | 15.2 | 0.69 | 80 | 8700 | 8.2 | ||

| 18 |

|

NMe2 | 8.5 | 0.69 | 47 | 3.4 | 18 | 1.0 | 64 | 12.8 | 1.78 | 46 | 11200 | 3.5 | |

| 19 |

|

NMe2 | 8.5 | 1.25 | >53 | −488 | 5.2 | 54 | 1.2 | 88 | 17.7 | 1.52 | 58 | 11900 | 5.1 |

Calculated using ACD pKa.

Calculated using ACD logD.

Solubility of HCl salts in culture medium.

Hypoxia Cytotoxicity Ratio = oxic IC50/hypoxic IC50.

Diffusion coefficient in HT29 MCLs ×10−7 cm2s−1.

Error estimates are provided in the Supporting Information.

First order rate constant for metabolism in anoxic HT29 cell suspensions, scaled to the cell density in MCLs.

Penetration half distance in anoxic HT29 tumor tissue (see text).

Predicted area under the plasma concentration-time curve required to give 1 log of cell kill in addition to that produced by a single 20 Gy dose of gamma radiation.

In vivo Hypoxic Cytotoxicity Differential = LCKhypoxic/LCKoxic.

Data from Reference 48.

Not applicable.

Table 3.

Physicochemical, in vitro and modelling parameters for TPZ and TTOs 33–42.

| |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | R1 | R2 | pKaa | logP7 calcb.4 | Sol.c mM | E(1) mV | HT29IC50 hypox μM | HT29 HCRd | SiHa IC50 hypox μM | SiHa HCRd | D calce,f | kmetf,g min−1 | X½f,h μm | AUCreqi μM.min | HCDj |

| 1k | nal | nal | nal | −0.33 | 9 | −456 | 5.1 | 71 | 2.5 | 107 | 4.2 | 0.58 | 45 | 10200 | 4.1 |

| 33 | CH3 | CH2OH | 0.0 | 1.14 | 10 | 13.0 | 80 | 8.0 | 104 | 21.0 | 0.24 | 158 | 10300 | 10.9 | |

| 34 | CH3 | CH2N-morpholine | 7.1 | 0.99 | 36 | 2.9 | 72 | 1.7 | 134 | 21.0 | 0.96 | 80 | 4960 | 5.8 | |

| 35 | CH2OH | H | 0.0 | 0.69 | 5 | −452 | 17 | 45 | 6.5 | 48 | 17.7 | 0.47 | 104 | 4150 | 9.2 |

| 36 | CH2N-morpholine | H | 7.0 | 0.29 | 43 | 4.8 | 31 | 2.4 | 62 | 17.3 | 0.54 | 96 | 3390 | 8.8 | |

| 37 | CH2OH | CH2N-morpholine | 7.1 | −0.18 | 48 | −408 | 2.4 | 121 | 1.8 | 206 | 3.8 | 0.90 | 35 | 14100 | 2.7 |

| 38 | (CH2)2OH | H | na | 0.50 | 2 | 7.7 | 102 | 2.9 | 86 | 15.4 | 0.54 | 91 | 6130 | 8.6 | |

| 39 | (CH2)3N-morpholine | H | 7.5 | 0.50 | >51 | −431 | 3.6 | 36 | 1.3 | 84 | 18.5 | 0.54 | 100 | 2560 | 8.7 |

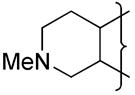

| 40 |

|

CH2N-morpholine | 7.1 | −1.30 | 51 | −468 | 8.9 | 25 | 5.1 | 43 | 3.5 | 0.31 | 57 | 6680 | 5.7 |

| 41 |

|

H | 5.8 | 0.09 | >47 | −344 | 13.1 | 2 | 3.1 | 6 | 20.9 | ||||

| 42 |

|

H | 5.2 | 0.19 | |||||||||||

Calculated using ACD pKa.

Calculated using ACD logD.

Solubility of HCl salts in culture medium.

Hypoxia Cytotoxicity Ratio = oxic IC50/hypoxic IC50.

Diffusion coefficient in HT29 MCLs ×10−7 cm2s−1.

Error estimates are provided in the Supporting Information.

First order rate constant for metabolism in anoxic HT29 cell suspensions, scaled to the cell density in MCLs.

Penetration half distance in anoxic HT29 tumor tissue (see text).

Predicted area under the plasma concentration-time curve required to give 1 log of cell kill in addition to that produced by a single 20 Gy dose of gamma radiation.

In vivo Hypoxic Cytotoxicity Differential = LCKhypoxic/LCKoxic.

Data from Reference 48.

Not applicable.

The relationship between cell killing, drug exposure and drug metabolism (i.e. the in vitro PK/PD model) was measured as previously described43,44 by following the clonogenicity of stirred single cell suspensions of HT29 cells for 3 h, at a drug concentration giving approximately one log kill by 1 h, with monitoring of drug concentrations in extracellular medium by HPLC. This concentration-time data were fitted to determine the apparent first order rate constant for metabolic consumption, kmet. The measured parameter values are given in Tables 1–3 and the associated error estimates are tabulated in the Supporting Information. The best fit PK/PD model,44,48,49 the CT10 (area under the concentration-time curve providing a 10% surviving fraction) and M10 (amount of BTO metabolized for a 10% surviving fraction) were estimated by interpolation and are tabulated in the Supporting Information along with the associated error estimates.

Tissue diffusion coefficients, D, of six TTOs were measured using HT29 MCLs as previously described under 95% O2 to suppress bioreductive metabolism.43 These values, along with previously reported measurements for BTO analogues44,47 and data for other BTOs (a total of 73 compounds) were used to develop a multiple regression model to calculate D for the other analogues as described previously.48 This model extends the reported47 dependence, for neutral BTOs, of D on logP and molecular weight (MW) by replacing logP with the octanol/water distribution coefficient at pH 7.4 (logP7.4) and by adding terms for the numbers of hydrogen bond donors (HD) and acceptors (HA) (eq. 1).67 The calculated and measured values and the associated error estimates are tabulated in the Supporting Information. The calculated values for all TTOs are shown in Tables 1–3.

| (1) |

A one-dimensional EVT parameter, the penetration distance into hypoxic tissue assuming planar geometry (X½, eq. 2), was calculated from the opposing effects of D and kmet on tissue transport as previously reported,48 providing a ready comparison between analogues: values are given in Tables 1–3, and the associated error estimates are tabulated in the Supporting Information.

| (2) |

PK/PD modelling

The in vivo 3D PK/PD model has been described in detail recently45,48 Briefly, transport is modelled in the extravascular compartment of a representative tumor microvascular network by solving the Fick’s Second Law diffusion-reaction equations using a Green’s function method, providing a description of the PK at each point in the tissue region. The transport parameters used in the model are the tissue diffusion coefficient D (estimated in MCLs) and kmet for bioreductive drug metabolism under anoxia (scaled to MCL cell density) determined in vitro as described above. Using the homogeneous PK/PD model established in vitro for each compound, the log cell kill (LCK) was predicted at each position in the tumor microregion. The overall cell kill through the whole region was then calculated for drug only and for drug plus 20 Gy radiation (using the reported radiosensitivity parameters for aerobic and hypoxic HT29 cells).44 The difference between these [LCK(drug + RAD) − LCK(drug alone)] gives the model-predicted logs of hypoxic cell kill (LCKpred). The in vitro PK/PD relationship was used to predict the area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUCreq) that would be required to give 1 log of cell kill in addition to that produced by a single 20 Gy dose of γ-radiation. In addition, the hypoxic cytotoxicity differential (HCD) is calculated as a measure of hypoxic selectivity in the tumor:

| (3) |

where LCK is predicted for the drug alone.

Compounds with high potency (low plasma AUCreq) and high in vivo hypoxic selectivity (HCD) have potential to demonstrate improved in vivo hypoxic cell kill compared to TPZ. Comparison using these criteria was made to evaluate the potential of the analogues as improved analogues of TPZ.

Results and Discussion

Targeting the cycloalkane ring systems 3–19 (Table 1) using the established benzotriazine ring formation was readily achieved. The cycloalkyl rings conferred increased lipophilicity relative to TPZ. The low solubility of 3 was remedied by addition of an aminoalkylamine at the 3-position, e.g., 4 (Table 1). This effect was general, with only the piperidine 7 failing to show increased solubility.

We have previously demonstrated48 that replacing the strongly electron-donating 3-NH2 (σp = −0.66) with the dimethylaminoethylamine side chain raises the one electron reduction potential, E(1), of TPZ by 60 mV. This can be offset by electron-donating substituents at the 6-position, with a 6-Me substituent lowering the E(1) by 40 mV and a 6-OMe substituent, e.g., 2, lowering the E(1) by 104 mV to a value of −500 mV. Thus, the cycloalkane rings (4, 9 and 19) lowered the E(1) by ca. 90 mV and the inclusion of a lower pKa amine (13) resulted in a further reduction in E(1).

The fusion of a cycloalkane ring at the 6,7- or 7,8-positions of the BTO nucleus provided TTOs with similar hypoxic cytotoxicity and selectivity to TPZ with the main variation in hypoxic potency resulting from variation in amine sidechain pKa. Thus the morpholides 8, 13, 15 were considerably less potent than more basic analogues. This drop in potency was also reflected in lowered hypoxic metabolism, with the cyclohexyl analogue 17 showing unusually high hypoxic metabolism and potency relative to the other morpholides. The increased lipophilicity from the cycloalkyl rings resulted in increased diffusion relative to TPZ. Consequently, most of these TTOs showed increased EVT as defined by the 1-D transport parameter X½.

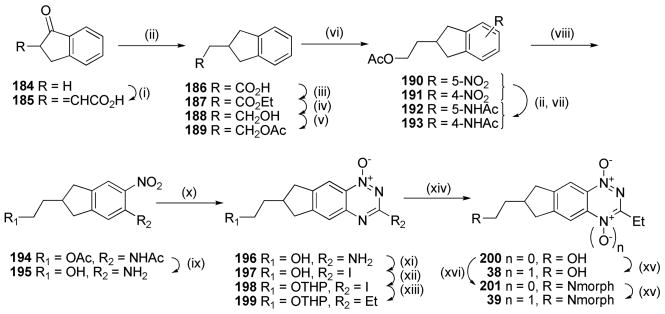

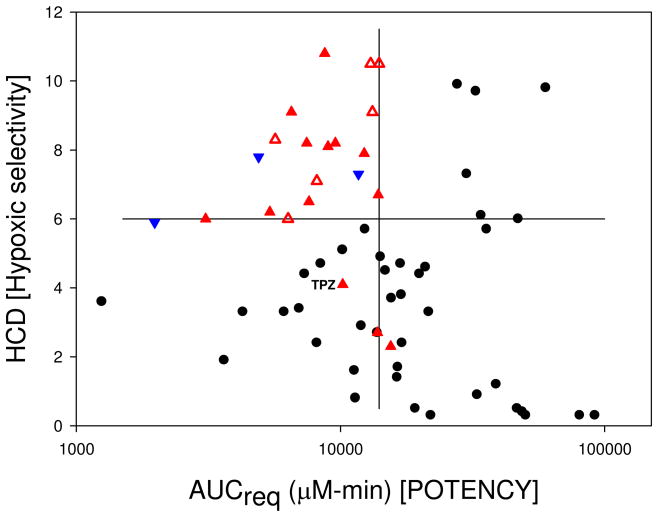

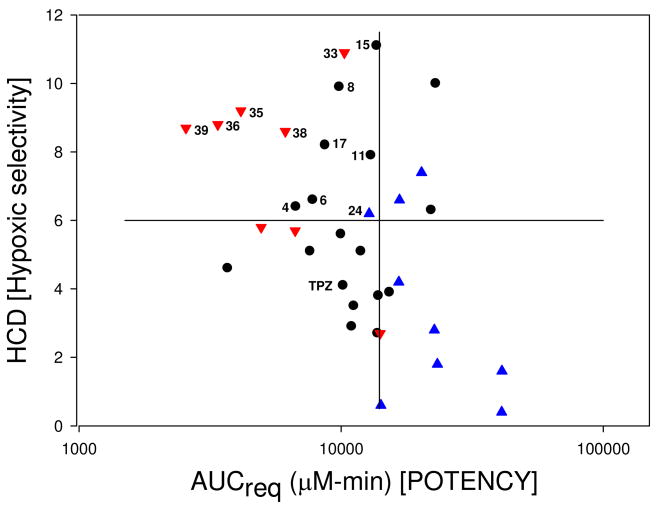

Calculation of the predicted AUC required to achieve 1 log of hypoxic cell kill in tumors (AUCreq) and the in vivo hypoxic selectivity (HCD) allowed comparison with previously studied BTO analogues.48,49 In these studies analogues with high predicted hypoxic selectivity (HCD) and high predicted in vivo potency (AUCreq) were most likely to be active in vivo (upper-left quadrant, Figure 2a). A number of compounds predicted to be active but were not tested because they were structurally similar to other actives (red open triangles, △). The predicted activity is subject to the in vivo toxicity and plasma pharmacokinetics and in a few examples very low plasma AUC values precluded activity (inverted blue triangles, ▼). Using these data as a guide (HCD > 6, AUCreq < 14,000 μM·min) six cycloalkyl-TTOs (4, 6, 8, 11, 15, 17) demonstrated the potential for in vivo activity (black circles, Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Figure 2a. Predicted Hypoxic Selectivity (HCD) and Potency (AUCreq) for BTOs.

Legend for Table 2a: ●compounds predicted inactive;  , active in vivo;

, active in vivo;  , not tested due to structural similarity to actives;

, not tested due to structural similarity to actives;  , not active in vivo. Data from Refs 48 and 49.

, not active in vivo. Data from Refs 48 and 49.

Figure 2b. Predicted Hypoxic Selectivity (HCD) and Potency (AUCreq) for TTOs.

Legend for Table 2b: ● TTOs from Table 1;  , TTOs from Table 2;

, TTOs from Table 2;  , TTOs from Table 3.

, TTOs from Table 3.

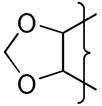

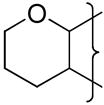

The inclusion of a heteroatom in the fused ring resulted in TTOs with considerably lower lipophilicity than the corresponding cycloalkyl analogues (e.g., compare 20 or 23 with 4; 27 with 16) (Table 2). Again the inclusion of a basic side chain conferred excellent aqueous solubility, with the neutral TTO 22 displaying very low solubility. The indanamine 30 was not stable in medium and was not evaluated in vitro.

Table 2.

Physicochemical, in vitro and modelling parameters for TPZ and TTOs 20–32.

| |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Ring C | R1 | pKaa | logP7.4 calcb | Sol.c mM | E(1) mV | HT29 IC50 hypox μM | HT29 HCRd | SiHa IC50 hypox μM | SiHa HCRd | D calce,f | kmetf,g min−1 | X½f,h μm | AUCreqi μM.min | HCDj |

| 1k | nal | H | nal | −0.33 | 9 | −456 | 5.1 | 71 | 2.5 | 107 | 4.2 | 0.58 | 45 | 10200 | 4.1 |

| 20 |

|

(CH2)2NMe2 | 8.5 | −1.05 | >48 | −487 | 2.4 | 23 | 0.30 | 87 | 2.6 | 3.15 | 20 | 23300 | 1.8 |

| 21 | (CH2)3N-morpholine | 7.4 | −0.27 | >49 | 22 | 8 | 3.4 | 28 | 2.8 | 0.20 | 64 | 20300 | 7.4 | ||

| 22 |

|

H | na | −0.04 | 0.1 | 117 | 4 | 23 | 3.6 | ||||||

| 23 | (CH2)2NMe2 | 8.5 | −1.01 | 49 | −545 | 5.2 | 46 | 1.9 | 128 | 2.6 | 0.60 | 36 | 22700 | 2.8 | |

| 24 | (CH2)2NEt2 | 9.4 | −0.68 | 47 | 10 | 113 | 3.4 | 122 | 2.9 | 0.26 | 57 | 12800 | 6.2 | ||

| 25 | (CH2)3N-morpholine | 7.4 | −0.27 | 46 | 49 | 6 | 29 | 14 | 2.8 | 0.23 | 60 | 16700 | 6.6 | ||

| 26 |

|

(CH2)2NMe2 | 8.5 | −1.09 | >50 | −541 | 13 | 26 | 5 | 53 | 2.3 | 0.87 | 28 | 41100 | 1.6 |

| 27 |

|

(CH2)2NMe2 | 8.5 | −0.54 | >45 | −453 | 1.5 | 19 | 0.3 | 60 | 3.2 | 2.43 | 23 | 14200 | 0.6 |

| 28 | (CH2)3N-morpholine | 7.4 | 0.48 | 40 | 11 | 19 | 3.6 | 41 | 4.8 | 0.97 | 38 | 29900 | 33.0 | ||

| 29 |

|

(CH2)2NMe2 | 8.5 | −0.26 | 47 | 4.1 | 14 | 0.7 | 66 | 3.9 | 0.59 | 44 | 16600 | 4.2 | |

| 30 |

|

Et | 7.6 | 0.08 | 46 | 7.6 | |||||||||

| 31 |

|

H | 4.1 | −0.57 | 6 | −390 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 80 | 2.7 | 2.20 | 19 | 41000 | 0.4 | |

| 32 |

|

Et | 5.8 | −0.29 | >47 | −462 | 2.6 | 59 | 1.1 | 100 | 5.4 | ||||

Calculated using ACD pKa.

Calculated using ACD logD.

Solubility of HCl salts in culture medium.

Hypoxia Cytotoxicity Ratio = oxic IC50/hypoxic IC50.

Diffusion coefficient in HT29 MCLs ×10−7 cm2s−1.

Error estimates are provided in the Supporting Information.

First order rate constant for metabolism in anoxic HT29 cell suspensions, scaled to the cell density in MCLs.

Penetration half distance in anoxic HT29 tumor tissue (see text).

Predicted area under the plasma concentration-time curve required to give 1 log of cell kill in addition to that produced by a single 20 Gy dose of gamma radiation.

In vivo Hypoxic Cytotoxicity Differential = LCKhypoxic/LCKoxic.

Data from Reference 48.

Not applicable.

The oxygen atom of the [3,2-g]dihydrofuran 20 had little effect on E(1) compared to 4 whereas the [2,3-g] isomer 23 shows a stronger influence and a similar effect is seen with the dioxole 26 having a similar E(1) to 23 (Table 2). This reflects the stronger electronic influence of substituents at the“6”-position compared to the “7”-position.50

The heterocyclic TTOs showed similar hypoxic potency to TPZ and slightly lower selectivity, with the weakly basic morpholides again displaying reduced potency. The TTO 22 showed low hypoxic potency and selectivity and failed to pass the criterion for hypoxic selectivity (HCR > 20) in the PK/PD model48,49 and was not evaluated further. The decreased lipophilicity of the heterocyclic TTOs 20–32 resulted in lowered diffusion with only the weakly basic amines 28, 30 and 32 having D values greater than TPZ. The rates of hypoxic metabolism were influenced by the electronic nature of the fused ring and the side chain amine pKa, with the weakly basic morpholides generally having lower kmet values compared to more basic analogues. For TTOs with a 7-oxa atom in the ring, e.g., 20 and 27, kmet values were relatively high reflecting the weaker dependence of E(1) on σp for 7-substituents.50 Only heterocyclic TTOs with very low kmet values achieved a balance with the low D values and thus only 21, 24 and 25 were predicted to display improved EVT based on their X½ values. Low hypoxic potency and kmet contributed to high AUCreq values which, when combined with modest predicted in vivo hypoxic selectivity (HCD) as a consequence of modest D values, resulted in only heteroalkyl-TTO 24 satisfying the criteria for predicted in vivo activity (AUCreq < 14,000; HCD > 6, blue triangle, Figure 2b).

A series of 3-alkyl TTOs 33–40 with solubilising groups attached via the 3-alkyl substituent or the 7-position of the indane ring was prepared. Two examples where the solubilising moiety was included within the isoquinoline ring (41, 42) were also prepared (Table 3). The strategy was to increase EVT through increased lipophilicity and to optimise the hypoxic metabolism by balancing the electron-donating effects of the fused rings. Replacement of the 3-aminoalkyl substituent with a 3-ethyl group (e.g., 35 compared with 4) raised the reduction potential by ca. 30 mV and the inclusion of a morpholine group on the side chain further raised the E(1) by ca. 40 mV. A similar elevation of E(1) was seen with the morpholide 40 when compared to 21. Placement of the morpholino group in a remote position off the indane ring (39) had a negligible effect on E(1).

TTOs 33–42 were generally more lipophilic than similar 3-alkylamino analogues with only the morpholide 40 showing significantly reduced lipophilicity relative to 25 due to the polarity of the dihydrofuran ring. Morpholide side chains provided increased aqueous solubility relative to TPZ whereas the neutral analogues had reduced solubility. TTO 42 was not evaluated because of instability in culture medium. The neutral TTOs were generally less potent than related analogues bearing morpholide side chains which had similar hypoxic cytotoxicity to TPZ. TTOs in this series were hypoxia-selective with the exception of 41, which was not evaluated further. The removal of the 3-NH group resulted in large increases in diffusion coefficient with the addition of a hydrogen bond donor (OH) having a similar negative effect to that of a morpholide group (e.g. compare 33 with 34; 35 with 36; 38 with 39). Hydrogen bond donors such as hydroxyl groups, although only modestly lowering the logP7.4, have a strong negative influence on diffusion rates.47 The strongly polar nature of the [2,3-g]dihydrofuran moiety dominated in TTO 40 leading to a low D value. The cycloalkyl TTOs 33–39 displayed similar rates of hypoxic metabolism to TPZ with the presence of a morpholide side chain producing a small elevation in kmet. The increased diffusion coefficients combined with modest rates of hypoxic metabolism gave significantly increased EVT as defined by X½. These factors combined to give relatively modest AUCreq values and high HCD across the series with TTOs (33, 35, 36, 38, 39) identified as likely to be active in vivo (AUCreq < 14,000; HCD > 6.0) (red inverted triangles, Figure 2b).

The addition of bulky fused rings, either in a linear or angular manner, or the placement of a polar hydroxyl or charged amine solubilizing group in either hemisphere of the molecule resulted in TTOs which were hypoxia-selective. This wide substrate tolerance is consistent with the description of cytochrome P450 reductase (CYP450R) as the major reductase responsible for bioactivation of TPZ.18 CYP450R’s prime role is to reduce the cofactor in cytochrome P450 and consequently it has a wide cleft allowing access of the substrate enzyme to the active site.68,69 For this enzyme interaction electron transfer occurs with minimal overlap of cofactors and is driven by the difference in reduction potential between the substrate and the cofactor.

Optimisation of rates of hypoxic metabolism and tissue diffusion coefficients has been possible for at least 12 different TTO analogues and these compounds are predicted to be active in vivo. Key to the ongoing development of this class of compounds is the determination of SAR for animal toxicity (maximum tolerated dose) and in vivo pharmacokinetics. The attainment of a sufficiently high Cmax and AUC has been demonstrated as necessary for activity against hypoxic tumor cells in vivo.45,48,49 Studies are currently underway with the twelve candidates predicted to be active in vivo to identify SAR for in vivo toxicity and pharmacokinetic parameters.

Conclusions

We have been able to build on previously described SAR to design a wide range of novel tricyclic TTO analogues and explore the effect of these structural modifications on their in vitro activity as hypoxia-selective cytotoxins. A wide range of structural arrangements with cycloalkyl, oxygen- and nitrogen-containing rings fused in a linear or angular fashion to the benzotriazine core, coupled with neutral, polar and charged side chains linked to either hemisphere, resulted in TTO analogues that displayed hypoxia-selective cytotoxicity in vitro.

The fused cycloalkyl rings are sufficiently electron-donating in combination with both the 3-aminoalkyl or 3-alkyl substituents to position the one electron reduction potential in an appropriate range for optimal rates of hypoxic metabolism. The stronger electronic and polar influences of the “oxa” rings were more difficult to balance and mostly led to poor EVT properties. The use of amine containing rings or substituents, while providing increased aqueous solubility, provided either unstable TTOs or only modest activity. The lipophilic nature of the cycloalkyl rings also increased lipophilicity and led to increased diffusion coefficients which when combined with weakly basic morpholine side chains gave the best balance of solubility and increased diffusion.

The selection was further refined using PK/PD model predictions of the AUCreq and HCD and 12 TTOs were predicted to be active in vivo subject to adequate plasma pharmacokinetics.

Experimental Section

Chemistry

General experimental details are described in the Supporting Information. TPZ and BTO 2 were synthesized as previously described.48

Example of synthetic methods

(See Supporting Information for full experimental details)

Preparation of 3-Aminotriazine 1-Oxides. Method (i), Scheme 1

A mixture of nitroaniline (20 mmol) and cyanamide (80 mmol) were mixed together at 100 °C, cooled to 50 °C, cHCl (10 mL) added dropwise (CAUTION: Exotherm) and the mixture heated at 100 °C for 4 h. The mixture was cooled to 50 °C, 7.5 M NaOH solution added until the mixture was strongly basic and the mixture stirred at 100 °C for 3 h. The mixture was cooled, diluted with water (100 mL), filtered, washed with water (3 × 30 mL), washed with ether (2 × 5 mL) and dried. If necessary, the residue was purified by chromatography, eluting with a gradient (0–10%) of MeOH/DCM, to give the 1-oxide.

Preparation of 3-Chlorotriazine 1-Oxides. Method (iii, iv), Scheme 1

Sodium nitrite (10 mmol) was added in small portions to a stirred solution of 1-oxide (5 mmol) in trifluoroacetic acid (20 mL) at 0 °C and the solution stirred at 20 °C for 3 h. The solution was poured into ice/water, stirred 30 minutes, filtered, washed with water (3 × 10 mL) and dried. The solid was suspended in POCl3 (20 mL) and DMF (0.2 mL) and stirred at 100 °C for 1 h. The solution was cooled, poured into ice/water, stirred for 30 minutes, filtered, washed with water (3 × 30 mL) and dried. The solid was suspended in DCM (150 mL), dried and the solvent evaporated. The residue was purified by chromatography, eluting with 5% EtOAc/DCM, to give the chloride.

Preparation of 3-alkylamino 1-Oxides. Method (vi), Scheme 1

Amine (3.0 mmol) was added to a stirred solution of chloride (1.0 mmol) in DME (50 mL) and the solution stirred at reflux temperature for 8 h. The solution was cooled to 20 °C, the solvent evaporated and the residue partitioned between aqueous NH4OH solution (100 mL) and EtOAc (100 mL). The organic fraction was dried, and the solvent evaporated. The residue was purified by chromatography, eluting with a gradient (0–10%) of MeOH/DCM, to give the 1-oxide.

Preparation of 1-Oxides. Method (vii), Scheme 1

Pd(PPh3)4 (0.1 mmol) was added to a stirred, degassed solution of halide (2.0 mmol) and stannane (2.4 mmol) in DME (20 mL) and the solution stirred under N2 at reflux temperature for 16 h. The solvent was evaporated, the residue dissolved in DCM (10 mL) and stirred with saturated aqueous KF solution (10 mL) for 30 min. The mixture was filtered through Celite, the Celite washed with DCM and the combined organic filtrate washed with water. The organic fraction was dried, the solvent evaporated and the residue purified by chromatography, eluting with DCM to give product, which was, if necessary, further purified by chromatography, eluting with 20% EtOAc/pet. ether, to give the 3-alkyl 1-oxide.

Preparation of 1,4-Dioxides 3–42. Method (vii), Scheme 1

Hydrogen peroxide (70%, 10 mmol) was added dropwise to a stirred solution of trifluoroacetic anhydride (10 mmol) in DCM (20 mL) at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 5 min, warmed to 20 °C, stirred for 10 min, and cooled to 5 °C. The mixture was added to a stirred solution of 1-oxide (1.0 mmol) [and where aliphatic amine side chains are present, TFA (5.0 mmol)] in DCM (15 ml) at 0 °C and the mixture stirred at 20 °C for 4–16 h. The solution was carefully diluted with water (20 mL) and the mixture made basic with aqueous NH4OH solution, the mixture was stirred for 15 min and then extracted with CHCl3 (5 × 50 mL). The organic fraction was dried and the solvent evaporated. The residue was purified by chromatography, eluting with a gradient (0–15%) of MeOH/DCM, to give 1,4-dioxides.

Supplementary Material

Experimental details and characterization data for synthetic intermediates 43–208 and TTOs 3–42; experimental details for the physicochemical and biological methods; tables of physicochemical and in vitro data with estimates of errors. This information (81 pages) is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Figure 1.

Scheme 3a.

aReagents: (i) cHNO3; (ii) H2, Pd/C, cHCl, EtOH; (iii) Ac2O, dioxane; (iv) cHNO3, CF3CO2H; (v) cHCl, EtOH, Δ; (vi) NH2CN, HCl, Δ; then 30% NaOH, Δ; (vii) NaNO2, CF3CO2H; (viii) DMF, POCl3, Δ; (ix) RCH2CH2NH2, DME, Δ; (x) CF3CO3H, CF3CO2H, DCM.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jane Botting, Dr Maruta Boyd, Alison Hogg, Sisira Kumara, Sarath Liyanage, for technical assistance. The authors thank Degussa Peroxide Ltd, Morrinsville, NZ for the generous gift of 70% hydrogen peroxide. This work was supported by the US National Cancer Institute under Grant CA82566 (MPH, KP, KOH, FBP, WRW, WAD), the Health Research Council of New Zealand (WRW, RFA, SSS), and the Auckland Division of the Cancer Society of New Zealand (WAD). Further support from Proacta Therapeutics Ltd (HHL) and the Australian Institute of Nuclear Sciences and Engineering is acknowledged.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: TPZ, Tirapazamine; BTO, 1,2,4-benzotriazine 1,4-dioxide; HCR, hypoxic cytotoxicity ratio; EVT, extravascular transport; E(1), one-electron reduction potential; PK/PD, pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic; D, tissue diffusion coefficient; MCL, multicellular layer; kmet, first order rate constant for bioreductive metabolism; SAR, structure activity relationships; 9-BBN, 9-borabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane; P7.4, octanol/water coefficient at pH 7.4; CT10, area under concentration-time curve providing 10% surviving fraction; M10, amount of BTO metabolised for 10% surviving fraction; X½, calculated penetration half-distance into hypoxic tissue; SF, surviving fraction; LCK, log cell kill; AUCreq, area under the plasma concentration-time curve required to give 1 log of cell kill of hypoxic cells in HT29 tumors; HCD, hypoxic cytotoxicity differential.

References

- 1.Semenza GL. HIF-1 mediates the Warburg effect in clear cell renal carcinoma. J Bioenergetics Biomembranes. 2007;39:231–234. doi: 10.1007/s10863-007-9081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gatenby RA, Gillies RJ. Glycolysis in cancer: a potential target for therapy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:1358–1366. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris AL. Hypoxia-a key regulatory factor in tumour growth. Nature Rev Cancer. 2002;2:38–47. doi: 10.1038/nrc704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Semenza GL. HIF-1 and tumor progression: pathophysiology and therapeutics. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8:S62–S67. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(02)02317-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pennachietti S, Michieli P, Galluzzo M, Mazzone M, Giordano S, Comoglio PM. Hypoxia promotes invasive growth by transcriptional activation of the met protooncogene. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:347–361. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00085-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cairns RA, Hill RP. Acute hypoxia enhances spontaneous lymph node metastasis in an orthotopic murine model of human cervical carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2054–2061. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Subarsky P, Hill RP. The hypoxic tumour microenvironment and metastatic progression. Clin Exptl Metastases. 2003;20:237–250. doi: 10.1023/a:1022939318102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durand RE. The influence of microenvironmental factors during cancer therapy. In Vivo. 1994;8:691–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tannock IF. Conventional cancer therapy: promise broken or promise delayed? Lancet. 1998;351(Suppl 2):9–16. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)90327-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown JM, Wilson WR. Exploiting tumor hypoxia in cancer treatment. Nature Rev Cancer. 2004;4:437–447. doi: 10.1038/nrc1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nordsmark M, Overgaard M, Overgaard J. Pretreatment oxygenation predicts radiation response in advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Radiother Oncol. 1996;41:31–39. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(96)91811-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fyles AW, Milosevic M, Wong R, Kavanagh MC, Pintilie M, Sun A, Chapman W, Levin W, Manchul L, Keane TJ, Hill RP. Oxygenation predicts radiation response and survival in patients with cervix cancer. Radiother Oncol. 1998;48:149–156. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(98)00044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koukourakis MI, Bentzen SM, Giatromanolaki A, Wilson GD, Daley FM, Saunders MI, Dische S, Sivridis E, Harris AL. Endogenous markers of two separate hypoxia response pathways (hypoxia inducible factor 2 alpha and carbonic anhydrase 9) are associated with radiotherapy failure in head and neck cancer patients recruited in the CHART randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:727–735. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.7474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denny WA, Wilson WR, Hay MP. Recent developments in the design of bioreductive drugs. Brit J Cancer. 1996;74:S32–S38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown JM, Giaccia AJ. The unique physiology of solid tumors: opportunities (and problems) for cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1408–1416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown JM. SR 4233 (tirapazamine): a new anticancer drug exploiting hypoxia in solid tumours. Br J Cancer. 1993;67:1163–1170. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1993.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Denny WA, Wilson WR. Tirapazamine: a bioreductive anticancer drug that exploits tumour hypoxia. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2000;9:2889–2901. doi: 10.1517/13543784.9.12.2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patterson AV, Saunders MP, Chinje EC, Patterson LH, Stratford IJ. Enzymology of tirapazamine metabolism: a review. Anti-Cancer Drug Des. 1998;13:541–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson RF, Shinde SS, Hay MP, Gamage SA, Denny WA. Activation of 3-amino-1,2,4-benzotriazine 1,4-dioxide antitumor agents to oxidizing species following their one-electron reduction. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:748–756. doi: 10.1021/ja0209363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shinde SS, Anderson RF, Hay MP, Gamage SA, Denny WA. Oxidation of 2-deoxyribose by benzotriazinyl radicals of antitumor 3-amino-1,2,4-benzotriazine 1,4-dioxides. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:7853–7864. doi: 10.1021/ja048740l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daniels JS, Gates KS. DNA cleavage by the antitumor agent 3-amino-1,2,4-benzotriazine 1,4-dioxide (SR4233). Evidence for involvement of hydroxyl radical. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:3380–3385. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chowdhury G, Junnotula V, Daniels JS, Greenberg MM, Gates KS. DNA strand damage product analysis provides evidence that the tumor cell-specific cytotoxin tirapazamine produces hydroxyl radical, acts as a surrogate for O2. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12870–12877. doi: 10.1021/ja074432m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J, Biedermann KA, Brown JM. Repair of DNA and chromosome breaks in cells exposed to SR 4233 under hypoxia or to ionizing radiation. Cancer Res. 1992;52:4473–4477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siim BG, van Zijl PL, Brown JM. Tirapazamine-induced DNA damage measured using the comet assay correlates with cytotoxicity towards hypoxic tumour cells in vitro. Br J Cancer. 1996;73:952–960. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siim BG, Menke DR, Dorie MJ, Brown JM. Tirapazamine-induced cytotoxicity and DNA damage in transplanted tumors: relationship to tumor hypoxia. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2922–2928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peters KB, Brown JM. Tirapazamine: A Hypoxia-activated Topoisomerase II Poison. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5248–5253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evans JW, Chernikova SB, Kachnic LA, Banath JP, Sordet O, Delahoussaye YM, Treszezamsky A, Chon BH, Feng Z, Gu Y, Wilson WR, Pommier Y, Olive PL, Powell SN, Brown JM. Homologous recombination is the principal pathway for the repair of DNA damage induced by tirapazamine in mammalian cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:257–265. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown JM, Lemmon MJ. Potentiation by the hypoxic cytotoxin SR 4233 of cell killing produced by fractionated irradiation of mouse tumors. Cancer Res. 1990;50:7745–7459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown JM, Lemmon MJ. Tumor hypoxia can be exploited to preferentially sensitize tumors to fractionated irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;20:457–461. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90057-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dorie MJ, Brown JM. Tumor-specific, schedule-dependent interaction between tirapazamine (SR 4233) and cisplatin. Cancer Res. 1993;53:4633–4636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dorie MJ, Brown JM. Modification of the antitumor activity of chemotherapeutic drugs by the hypoxic cytotoxic agent tirapazamine. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1997;39:361–366. doi: 10.1007/s002800050584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marcu L, Olver I. Tirapazamine: From Bench to Clinical Trials. Curr Clinical Pharmacol. 2006;1:71–79. doi: 10.2174/157488406775268192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rischin D, Fisher R, Peters L, Corry J, Hicks R. Hypoxia in head and neck cancer: Studies with hypoxic positron emission tomography and hypoxic cytotoxins. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:S61–S63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rischin D, Peters L, O’Sullivan B, Giralt J, Yuen K, Trotti A, Bernier J, Bourhis J, Henke M, Fisher R. Phase III study of tirapazamine, cisplatin and radiation versus cisplatin and radiation for advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.4449. abstr LBA6008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rischin D, Hicks RJ, Fisher R, Binns D, Corry J, Porceddu S, Peters LJ. Prognostic significance of [18F]-misonidazole positron emission tomography-detected tumor hypoxia in patients with advanced head and neck cancer randomly assigned to chemoradiation with or without tirapazamine: a substudy of Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group Study 98.02. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2098–2104. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.2878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peters L, Rischin D, Fisher R, Corry J, Hicks R. Identification and therapeutic targeting of hypoxia in H&N cancer. Int. Congress. Radiat. Res.; San Francisco. 8–12th July 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rischin D, Peters L, Fisher R, Macann A, Denham J, Poulsen M, Jackson M, Kenny L, Penniment M, Corry J, Lamb D, McClure B. Tirapazamine, Cisplatin, and Radiation versus Fluorouracil, Cisplatin, and Radiation in patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer: a randomized phase II trial of the Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group (TROG 98.02) J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:79–87. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Durand RE, Olive PL. Physiologic and cytotoxic effects of tirapazamine in tumor-bearing mice. Radiat Oncol Investig. 1997;5:213–219. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6823(1997)5:5<213::AID-ROI1>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Durand RE, Olive PL. Evaluation of bioreductive drugs in multicell spheroids. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;22:689–692. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(92)90504-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hicks KO, Fleming Y, Siim BG, Koch CJ, Wilson WR. Extravascular diffusion of tirapazamine: effect of metabolic consumption assessed using the multicellular layer model. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;42:641–649. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00268-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kyle AH, Minchinton AI. Measurement of delivery and metabolism of tirapazamine to tumour tissue using the multilayered cell culture model. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1999;43:213–220. doi: 10.1007/s002800050886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baguley BC, Hicks KO, Wilson WR. Tumour cell cultures in drug development. In: Baguley BC, Kerr DJ, editors. Anticancer Drug Development. Academic Press; San Diego: 2002. pp. 269–284. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hicks KO, Pruijn FB, Sturman JR, Denny WA, Wilson WR. Multicellular resistance to tirapazamine is due to restricted extravascular transport: a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic study in multicellular layers. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5970–5977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hicks KO, Siim BG, Pruijn FB, Wilson WR. Oxygen dependence of the metabolic activation and cytotoxicity of tirapazamine: implications for extravascular transport and activity in tumors. Radiat Res. 2004;161:656–666. doi: 10.1667/rr3178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hicks KO, Pruijn FB, Secomb TW, Hay MP, Hsu R, Brown JM, Denny WA, Dewhirst MW, Wilson WR. Use of three-dimensional tissue cultures to model extravascular transport and predict in vivo activity of hypoxia-targeted anticancer drugs. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1118–1128. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hicks KO, Myint H, Patterson AV, Pruijn FB, Siim BG, Patel K, Wilson WR. Oxygen dependence and extravascular transport of hypoxia-activated prodrugs: comparison of the dinitrobenzamide mustard PR-104A and tirapazamine. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:560–571. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pruijn FB, Sturman J, Liyanage S, Hicks KO, Hay MP, Wilson WR. Extravascular transport of drugs in tumor tissue: Effect of lipophilicity on diffusion of tirapazamine analogues in multicellular layer cultures. J Med Chem. 2005;48:1079–1087. doi: 10.1021/jm049549p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hay MP, Hicks KO, Pruijn FB, Pchalek K, Siim BG, Wilson WR, Denny WA. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model-guided identification of hypoxia-selective 1,2,4-benzotriazine 1,4-dioxides with antitumor activity: the role of extravascular transport. J Med Chem. 2007;50:6392–6404. doi: 10.1021/jm070670g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hay MP, Pchalek K, Pruijn FB, Hicks KO, Siim BG, Anderson RR, Shinde SS, Phillips V, Denny WA, Wilson WR. Hypoxia-selective 3-alkyl 1,2,4-benzotriazine 1,4-dioxides: the influence of hydrogen bond donors on extravascular transport and antitumor activity. J Med Chem. 2007;50:6654–6664. doi: 10.1021/jm701037w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hay MP, Gamage SA, Kovacs MS, Pruijn FB, Anderson RF, Patterson AV, Wilson WR, Brown JM, Denny WA. Structure-activity relationships of 1,2,4-benzotriazine 1,4-dioxides as hypoxia-selective analogues of tirapazamine. J Med Chem. 2003;46:169–182. doi: 10.1021/jm020367+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zeman EM, Baker MA, Lemmon MJ, Pearson CI, Adams JA, Brown JM, Lee WW, Tracy M. Structure-activity relationships for benzotriazine di-N-oxides. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;16:977–981. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(89)90899-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Minchinton AI, Lemmon MJ, Tracy M, Pollart DJ, Martinez AP, Tosto LM, Brown JM. Second-generation 1,2,4-benzotriazine 1,4-di-N-oxide bioreductive antitumor agents: pharmacology and activity in vitro and in vivo. Int J Radiat Oncol, Biol Phys. 1992;22:701–705. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(92)90507-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kelson AB, McNamara JP, Pandey A, Ryan KJ, Dorie MJ, McAfee PA, Menke DR, Brown JM, Tracy M. 1,2,4-Benzotriazine 1,4-dioxides. An important class of hypoxic cytotoxins with antitumor activity. Anti-Cancer Drug Des. 1998;13:575–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jiang F, Yang B, Fan L, Heb Q, Hu Y. Synthesis and hypoxic–cytotoxic activity of some 3-amino-1,2,4-benzotriazine-1,4-dioxide derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:4209–4213. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.05.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jiang F, Weng Q, Sheng R, Xia Q, He Q, Yang B, Hu Y. Synthesis, structure and hypoxic cytotoxicity of 3-amino-1,2,4-benzotriazine-1,4-dioxide derivatives. Archiv der Pharmazie. 2007;340:258–263. doi: 10.1002/ardp.200600201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cerecetto H, Gonzalez M, Onetto S, Saenz P, Ezpeleta O, De Cerain AL, Monge A. 1,2,4-Triazine N-oxide derivatives: Studies as potential hypoxic cytotoxins. Part II. Arch Pharmazie. 2004;337:247–258. doi: 10.1002/ardp.200300782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cerecetto H, Gonzalez M, Risso M, Saenz P, Olea-Azar C, Bruno AM, Azqueta A, De Cerain AL, Monge A. 1,2,4-Triazine N-oxide derivatives: Studies as potential hypoxic cytotoxins. Part III. Arch Pharmazie. 2004;337:271–280. doi: 10.1002/ardp.200300839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Monge A, Palop JA, Gonzalez M, Martinez-Crespo FJ, De Cerain AL, Sainz Y, Narro S, Barker AJ, Hamilton E. New hypoxia-selective cytotoxins derived from quinoxaline 1,4-dioxides. J Het Chem. 1995;32:1213–1217. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Monge A, Palop JA, De Cerain AL, Senador V, Martinez-Crespo FJ, Sainz Y, Narro S, Garcia E, de Miguel C, Gonzalez M. Hypoxia-selective agents derived from quinoxaline 1,4-di-N-oxides. J Med Chem. 1995;38:1786–1792. doi: 10.1021/jm00010a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Monge A, Martinez-Crespo FJ, De Cerain AL, Palop JA, Narro S, Senador V, Marin A, Sainz Y, Gonzalez M, Hamilton E. Hypoxia-selective agents derived from 2-quinoxalinecarbonitrile 1,4-di-N-oxides. 2. J Med Chem. 1995;38:4488–4494. doi: 10.1021/jm00022a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Amin KM, Ismail MMF, Noaman E, Soliman DH, Ammard YA. New quinoxaline 1,4-di-N-oxides. Part 1: Hypoxia-selective cytotoxins and anticancer agents derived from quinoxaline1,4-di-N-oxides. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14:6917–6923. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hay MP, Denny WA. A new and versatile synthesis of 3-alkyl-1,2,4-benzotriazine-1,4-dioxides: preparation of the bioreductive cytotoxins SR4895 and SR4941. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:9569–9571. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pchalek K, Hay MP. Stille Coupling Reactions in the Synthesis of Hypoxia-Selective 3-Alkyl-1,2,4-Benzotriazine 1,4-Dioxide Anticancer Agents. J Org Chem. 2006;71:6530–6535. doi: 10.1021/jo060986g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Anderson RF, Denny WA, Li W, Packer JE, Tercel M, Wilson WR. Pulse radiolysis studies on the fragmentation of arylmethyl quaternary nitrogen mustards upon their one-electron reduction in aqueous solution. J Phys Chem A. 1997;101:9704–9709. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wardman P. Reduction potentials of one-electron couples involving free radicals in aqueous solution. J Phys Chem Ref Data. 1989;18:1637–1755. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Siim BG, Hicks KO, Pullen SM, van Zijl PL, Denny WA, Wilson WR. Comparison of aromatic and tertiary amine N-oxides of acridine DNA intercalators as bioreductive drugs – cytotoxicity, DNA binding, cellular uptake, and metabolism. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60:969–978. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00420-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pruijn FB, Patel K, Hay MP, Wilson WR, Hicks KO. Prediction of Tumour Tissue Diffusion Coefficients of Hypoxia-Activated Prodrugs from Physicochemical Parameters. Aust J Chem. 2008;61:687–693. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang M, Roberts DL, Paschke R, Shea TM, Masters BSS, Kim J-JP. Three-dimensional structure of NADPH–cytochrome P450reductase: Prototype for FMN-FAD-containing enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8411–8416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhao Q, Modi S, Smith G, Paine M, Mcdonagh PD, Wolf CR, Tew D, Lian LY, Roberts GCK, Driessen HPC. Crystal structure of the FMN-binding domain of human cytochrome P450 reductase at 1.93 Å resolution. Protein Sci. 1999;8:298–306. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.2.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental details and characterization data for synthetic intermediates 43–208 and TTOs 3–42; experimental details for the physicochemical and biological methods; tables of physicochemical and in vitro data with estimates of errors. This information (81 pages) is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.