Abstract

Insolubility of full-length HIV-1 integrase (IN) limited previous structure analyses to individual domains. By introducing five point mutations, we engineered a more soluble IN that allowed us to generate multidomain HIV-1 IN crystals. The first multidomain HIV-1 IN structure is reported. It incorporates the catalytic core and C-terminal domains (residues 52–288). The structure resolved to 2.8 Å is a Y-shaped dimer. Within the dimer, the catalytic core domains form the only dimer interface, and the C-terminal domains are located 55 Å apart. A 26-aa α-helix, α6, links the C-terminal domain to the catalytic core. A kink in one of the two α6 helices occurs near a known proteolytic site, suggesting that it may act as a flexible elbow to reorient the domains during the integration process. Two proteins that bind DNA in a sequence-independent manner are structurally homologous to the HIV-1 IN C-terminal domain, suggesting a similar protein–DNA interaction in which the IN C-terminal domain may serve to bind, bend, and orient viral DNA during integration. A strip of positively charged amino acids contributed by both monomers emerges from each active site of the dimer, suggesting a minimally dimeric platform for binding each viral DNA end. The crystal structure of the isolated catalytic core domain (residues 52–210), independently determined at 1.6-Å resolution, is identical to the core domain within the two-domain 52–288 structure.

Integration of retroviral DNA into the host cell genome is required for virus replication and is mediated by viral integrase (IN) (Fig. 1). IN first removes two nucleotides from the 3′ end of each strand of the nascent viral DNA, leaving a recessed 3′ CA dinucleotide (3′ processing). After migration into the nucleus of the infected cell as part of a nucleoprotein complex, IN covalently attaches each 3′ processed viral end to the host cell DNA (strand transfer). Both 3′ processing and strand transfer are divalent cation-requiring trans-esterification reactions catalyzed at a single active site in the enzyme's core (1).

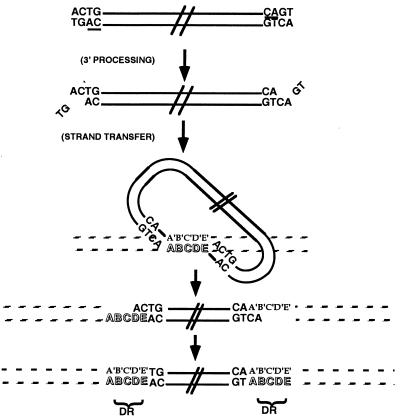

Figure 1.

HIV-1 IN activities. A schematic diagram of HIV-1 IN activities depicts the double-stranded DNA viral genome at the top as parallel black lines with the terminal nucleotides CAGT. The conserved 3′ CA dinucleotide is underlined at each viral end. IN first acts in the cytoplasm to remove the two 3′ nucleotides (3′ processing), leaving a 2-nt overhang at each 5′ end. In the nucleus, IN mediates a concerted integration (strand transfer) by ligating each 3′ end of the viral DNA (looped structure) to the host DNA (striped lines). This generates a “gapped intermediate” with free viral 5′ ends that are repaired to generate the fully integrated provirus. The characteristic HIV-1 5-bp staggered strand transfer is depicted by the letters A-E in the target DNA, and the resulting 5-bp direct repeats (DR) of host DNA flanking the provirus are indicated.

Sequence alignments (2, 3), mutagenesis (4–9), and proteolytic digestion (5) suggest a three-domain structure for HIV-1 IN. The N-terminal domain, residues 1–51, contains a conserved “HH-CC” motif that binds zinc in a 1:1 stoichiometry (10). The central catalytic core domain, residues 52–210, contains the catalytic site characterized by three invariant essential acidic residues, D64, D116, and E152. The C-terminal domain, amino acids 220–288, contributes to DNA binding and oligomerization necessary for the integration process (11) and is linked to the catalytic core by residues 195–220, an extension of the final helix of the core domain.

Prior efforts to crystallize full-length HIV-1 IN have been hampered by poor solubility. The mutation F185K markedly improved solubility of the central IN catalytic core domain to over 25 mg/ml and led to its crystal structure (12, 13). Structures of the individual N-terminal (14, 15) and C-terminal domains (16–18) have been determined by NMR. Like the catalytic core domain, each isolated terminal domain dimerizes in solution. Multidomain structures would provide insight into the relative spatial arrangement of the three domains, how IN binds to the host DNA and the viral DNA ends (att sites) during the 3′ processing and strand transfer reactions, and the oligomeric state of the active enzyme. To address these questions, we sought first to develop a more soluble form of functional, full-length IN (IN1–288) for crystallization.

The introduction of five point mutations, C56S, W131D, F139D, F185K, and C280S, improved the solubility of full-length IN1–288 and allowed for its crystallization. To date, however, IN1–288 crystals have diffracted to 8-Å resolution. Truncations of the penta-mutated IN1–288 yielded a 2.8-Å resolution crystal structure of a two-domain construct involving the catalytic core and the C-terminal domains (IN52–288) and a 1.6-Å resolution crystal structure of the catalytic core domain (IN52–210) as reported here.

Materials and Methods

Mutagenesis.

Mutations C56S, W131D, F139D, F185K, and C280S were introduced into a synthetic full-length HIV-1 IN (SF1) sequence in a pT7–7 vector by using oligonucleotide mutagenesis. An N-terminal 6-histidine (6-His) tag followed by a thrombin cleavage site (Stratagene) was added to facilitate purification. One- and two-domain truncation constructs, IN52–210 and IN52–288, were generated from the penta-mutated IN1–288. All mutations, the 6-His tag, and the thrombin cleavage site were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

IN Expression and Purification.

The 6-His-tagged IN52–288 was expressed in BL21 cells by using the pT7–7 isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside-inducible promoter. After sonication and dounce lysis, the protein was purified by using a Ni2+ column (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA). After thrombin (Novagen) cleavage, thrombin was removed by passage over a benzamidine column (Amersham Pharmacia). The cleaved 6-His tag and any uncleaved protein were removed by passage over a Ni2+ column. Purified IN52–288 migrated as a single band on SDS/PAGE. Identical methods were used to purify IN52–210. Purified protein was filtered (0.8/0.2 μm syringe filter; Gelman), concentrated by high-pressure, stirred-cell ultrafiltration (YM-10 membrane; Amicon), and dialyzed against 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.0), 500 mM NaCl, and 3 mM DTT. The final protein concentration ranged from 8 to 12 mg/ml or 6 to 10 mg/ml as determined by Bradford assay using a BSA standard or absorption at 280 nm with a calculated extinction coefficient of 37,930 liter/mol⋅cm and calculated mass of 28,022 g/mol, respectively.

Crystallization.

Crystals were grown in hanging drops at room temperature by vapor diffusion. Well buffer for IN52–288 was 2.2 M Na formate, 150 mM Na citrate, 3 mM DTT, 3 mM 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS), pH 5.6. Well buffer for IN52–210 was 1.7 M ammonium sulfate, 50 mM CdCl2, 150 mM Na citrate, 5 mM DTT, pH 5.6. Drops were made by mixing 4 μl of purified protein solution with 4 μl of well buffer. To decrease the equilibration rate, a 1:1 mixture of paraffin and silicon oils (Hampton Research, Riverside, CA) was applied over the well solution. Trigonal IN52–288 crystals, 350 × 250 × 100 μm, grew over several weeks. Bipyramidal IN52–210 crystals typically grew to ≈400 μm in each dimension. Before data collection, crystals were transferred to a cryoprotectant consisting of well buffer containing 15% (vol/vol) sucrose (IN52–210) or 20% (vol/vol) glycerol (IN52–288) and frozen in a 90 K nitrogen gas stream.

Structure Determination.

Diffraction was recorded by using a Mar Research image plate detector at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory. Intensities were integrated and scaled by using denzo/scalepack (19). The structure of the core alone, IN52–210, was solved by molecular replacement applied in cns (20) by using the IN (F185K) catalytic core (21) as a search model (Protein Data Bank code 1bis). The rotation function yielded a clear solution, which gave an unambiguous translation solution. Difference Fourier refinement (22) and manual rebuilding using chain (23) were interspersed with positional, B factor, and simulated annealing protocols in cns to define the structure.

The structure of two-domain IN52–288 was solved first by location of the catalytic core dimer by molecular replacement, as implemented in cns with the 1.6-Å catalytic core structure as a search model. A clear rotation solution was found (top product correlation peak 0.0410, next highest 0.0384), and this top peak also gave the highest translation solution (0.247, next highest 0.157). This initial placement gave a Rcryst of 53.7%. 2Fo−Fc maps, and Fo−Fc difference maps phased on the core dimer alone revealed additional density for the C-terminal domains, confirming the correctness of the solution.

The initial interpretation of the C-terminal domains of IN52–288 was facilitated by placement of the averaged NMR structure of the IN220–270 monomer (Protein Data Bank code 1ihw) (17) into the density maps using epmr (24). These domains were located with correlation coefficients of 0.41 (next highest 0.39), and 0.44 (next highest 0.41). The solution clarified the helical linkages between the catalytic core and C-terminal domains. The initial Rcryst for the catalytic core domain dimer plus the two C-terminal domains, the dimeric IN52–288 structure, was 48.7%.

The IN52–288 structure was refined by using rigid body, positional, B factor, and simulated annealing protocols in cns. Parallel refinements run with and without NCS restraints gave lower Rcryst and Rfree values without restraints, suggesting that the two monomers had different microstructures determined by their different environments. NCS restraints were therefore not applied.

Results

Mutagenesis to Increase IN Solubility.

In addition to the previously described F185K mutation (12, 13), we introduced mutations W131D and F139D to eliminate two hydrophobic residues on the core surface (12) and mutations C56S and C280S to minimize oxidation (25). This penta-mutated, full-length IN, IN1–288, remains in solution at > 12 mg/ml for over 30 days. It can perform 3′ processing and strand transfer activities and yields reproducible crystals. However, the IN1–288 crystals diffract to 8 Å. Truncations of the mutated IN1–288 yielded single- and two-domain constructs, IN52–210 and IN52–288, each of which formed crystals that diffracted to high and intermediate resolution, respectively.

Structure of the HIV-1 IN Core Domain.

Crystals of the isolated catalytic core domain, IN52–210, grew in a previously uncharacterized crystal form (space group P32, a = 48.9, c = 103.6 Å, one dimer/asymmetric unit) and diffracted beyond 1.6-Å resolution. This structure was solved by molecular replacement and refined to a Rcryst of 25.2%, Rfree of 26.9% for all reflections to 1.6 Å (Table 1). The structure has the same α-β fold and dimer interface as seen in previous structures of the catalytic core domain of HIV-1 IN (12, 13, 21, 26, 27), simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) IN (28), and Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) IN (29). The mutations introduced to improve IN solubility therefore did not change the catalytic core domain crystal structure.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Structure | IN52-210 | IN52-288 |

|---|---|---|

| Source | SSRL 7-1 (λ = 1.08 Å) | SSRL 9-1 (λ = 0.98 Å) |

| Resolution, Å | 30-1.6 | 30-2.8 |

| Space group | P32 | P312 |

| Unit cell, Å | a = 48.89, c = 103.64 | a = 103.99, c = 101.38 |

| Measured reflections | 213,312 | 178,921 |

| Independent reflections | 35,602 | 15,580 |

| Completeness, % | 97.3 | 99.8 |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 17.0 | 22.1 |

| Rmerge, %* | 5.3 | 7.7 |

| Wilson 〈B〉, Å2 | 24 | 68 |

| 〈B〉, Å2 | 30 | 73 |

| Rfree (%) (F > 3σ) | 26.9 (24.8) | 30.8 (28.4) |

| Rcryst (%) (F > 3σ) | 25.2 (22.8) | 26.0 (24.3) |

| rmsd bond angles, deg | 1.1 | 1.6 |

| rmsd bond lengths, Å | 0.005 | 0.007 |

| Luzzati error, Å | 0.25 | 0.44 |

| Ramachandran distribution | ||

| Most favored, % | 89.1 | 81.5 |

| Allowed, % | 10.9 | 18.5 |

| Waters | 99 | 81 |

rmsd, rms deviation.

Rmerge = Σ|I − 〈I〉/Σ|〈I〉|; negative intensities included as zero.

Two-Domain HIV-1 IN Structure.

Two-domain IN52–288 crystals diffracted to 2.8-Å resolution (space group P312, a = 104.0, c = 101.4 Å, with one dimer/asymmetric unit) (Table 1). The catalytic core domain within IN52–288 forms a symmetric dimer that is very similar to the crystal structure of the isolated catalytic core domain, IN52–210 (Cα rms deviation of 0.6 Å between monomers) (30). Each catalytic core domain of the IN52–288 dimer is linked to the C-terminal domain by residues 195–220 of helix α6. The divergent orientation of the two linking α6 helices within the dimer places the centers of the C-terminal domains ≈55 Å apart within the dimer, imparting a “Y” shape to the IN52–288 structure (Fig. 2 a and b). However, the orientations of the two C-terminal domains differ by ≈90° with respect to their 2-fold-related positions, gauged by using the 2-fold axis of the catalytic core domain (Fig. 2). An electrostatic potential map identifies a contiguous strip of positive charge along the outer face of the IN52–288 dimer, beginning at the active site of one monomer and extending along the linking α6 helix of the other monomer (Fig. 3a).

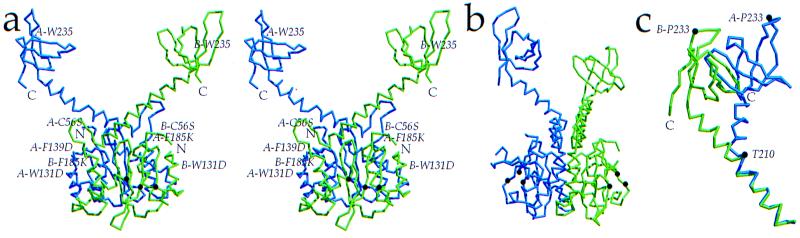

Figure 2.

Structure of HIV-1 IN52–288. (a) Stereoview of the HIV-1 IN52–288 dimer, composed of monomer A (blue) and monomer B (green). Monomer B catalytic residues D64, D116, and E152 are indicated (brown dots), and the N and C termini of each monomer are labeled. Immunologically critical residue W235 is located on the surface. Mutated residues C56S, W131D, F139D, and F185K are indicated, except for C280S, which is disordered. (b) The HIV-1 IN52–288 dimer rotated by 90° with respect to a. Catalytic residues are highlighted in brown. (c) Alignment of residues 195–210 in α6 demonstrates the kink at T210 that creates a ≈90° rotation of the C-terminal domains relative to one another as illustrated by the position of P233. Figure was generated by molscript (44) and raster3d (45).

Figure 3.

Electrostatic potential map of the HIV-1 IN52–288 dimer. (a) The dimer orientation is the same as in Fig. 2a. Potentials range from −15/kT (red) to +15/kT (blue). The strip of positive charge (blue) coursing up and to the left contains residues from both monomers of the dimer, K211, K215, and K219 from monomer A and K159, K186, R187, K188 from monomer B. The active site pocket of monomer B (*) includes catalytic residues D64, D116, and E152. (b) An 18-bp viral DNA end is modeled onto the IN dimer with the positively charged residues in contact with the DNA phosphodiester backbone. The adenine base of the conserved viral 3′ CA dinucleotide contacts K159. Docking of DNA was done with midas (46). Figure was generated by grasp (47).

All residues from position 56–137, 150–185, and 195–212 of the catalytic core domain within IN52–288 were clearly defined in conformation in both monomers. Residues 138–149 in the active site region, and residues 186–194 between the α5 and α6 helices, are flexible loops in poorly defined density, as previously noted in other unliganded core domain structures (12, 26, 31). However, residues 138–141 and 145–149 could be interpreted in monomer A, and the 186–194 loop in both monomers could be built into weak density based on its location in the 1.6-Å resolution IN52–210 structure. Residues 210–270 containing linking helix α6 and the C-terminal domain were ordered in both monomers of the IN52–288 dimer. Residues 271–288 are not clearly defined in density maps.

The average B factor of the catalytic core domain atoms within IN52–288 is 85 Å2, much higher than the 33 Å2 seen in the 1.6-Å IN52–210 structure of the isolated catalytic core domain. In contrast, the C-terminal domains of IN52–288, which form nearly all of the dimer-dimer crystal contacts, have an average B factor of 47 Å2. The average B factor of 85 Å2 for the core implies an average amplitude of thermal vibration of u = 1.04 Å (B = 8 π2<u2>). To investigate how well the structure of the high B factor core domain is defined by the density map, a simulated annealing composite omit map was constructed. This was done by leaving out the structure within sequential volumes of the structure throughout the asymmetric unit, and then refining the remainder of the structure by simulated annealing. Omit maps for each “omitted” volume were calculated and reassembled into a composite omit map (Fig. 4a). It revealed continuous density for the backbone and essentially all of the side chains (Fig. 4a), showing that the high B factor core domain is clearly defined when in the context of this lower B factor C-terminal domain. The source of the higher B factors is suggested by the fact that there is only one very small crystal contact involving the core. The B factors also generally increase with distance from the C-terminal tethering α6 helix, implying a rigid body libration of the otherwise well-ordered core domains.

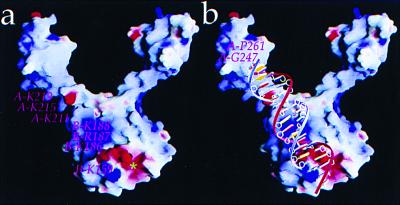

Figure 4.

Electron density plots from the IN52–288 structure. (a) Plot of a simulated annealing composite omit map showing 2Fo−Fc density contoured at 1 σ in a region of the HIV-1 IN52–288 catalytic core domain. The refined structure is superimposed on the density plot. (b) Plot of a 2Fo−Fc map, contoured at 1.2 σ, around linking helix α6 and the C-terminal domain of monomer B. At the left is the cis-proline, P238, where β2 sharply changes direction and transitions between the two β-sheets within the C-terminal domain. Maps were generated by cns (20). Figure was generated by molscript (44) and locally written frodomol.

Folds of β-sheets within individual C-terminal domains of IN52–288, composed of residues 223–228 (β1), 235–245 (β2), 248–252 (β3), 256–260 (β4), and 265–268 (β5), are similar to the solution NMR structure for the isolated HIV-1 IN C-terminal domain (18). The C-terminal domain is a sandwich of two three-stranded antiparallel β-sheets. The two three-stranded antiparallel β-sheets are formed by a noncontiguous triad of strands β1−β2−β5 (involving the N-terminal end of β2) and a contiguous triad of strands β2-β3-β4 (involving the C-terminal end of β2). The longer β2 strand transitions between the two sheets and is interrupted between sheets by a cis-proline, P238 (Fig. 4b).

C-Terminal Domain Interactions of IN52–288.

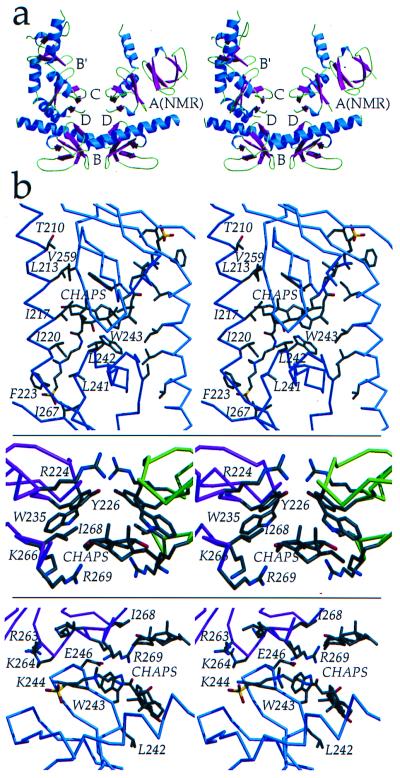

The vast majority of dimer-dimer contacts in the IN52–288 crystal structure are mediated by C-terminal domain interactions involving four adjacent dimers that meet around a crystallographic 2-fold axis to form four different types of contacts, interfaces B, B′, C, and D (Fig. 5). Interfaces B and B′ involve packing of the β2-β3-β4 sheet against the same β2-β3-β4 sheet of a 2-fold related molecule in a parallel manner (Fig. 5). However, a CHAPS molecule wedged between the two sheets, and in contact with L242 and W243, mediates this packing of hydrophobic surfaces. In addition to the CHAPS-mediated interactions at this interface, hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions occur between the β2-β3-β4 sheet and linking helix α6 from the 2-fold-related molecule (Fig. 5b). Because of the kink in the linking α6 helix, interface B′ possesses a greater number of interactions between the β2-β3-β4 sheet and linking helix α6 than does interface B. Interface C involves the antiparallel packing of the noncontiguous β1-β2-β5 sheets from different dimers against each other (Fig. 5b). Again, a CHAPS molecule is wedged in between these hydrophobic surfaces, and the only direct contact between sheets is a hydrogen bond between R224Nη1 and the carbonyl oxygen of W235. Interface D does not lie across a symmetry axis and is formed by edge-to-edge association of the β2-β3 loop 242–246 against the β5 strand 265–269 of the symmetry-related molecule (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

SH3–SH3 interactions. (a) The C-terminal domains within the IN52–288 dimer are 55 Å apart, but four different dimer-dimer contacts involving interactions between adjacent C-terminal domains, interfaces B, B′, C, and D, are found within the crystal. All four of these interfaces differ from interface A, which is found in the NMR structure of isolated C-terminal domains. Buried molecular surface areas for the interfaces are: B = 1,695 Å (2), B′ = 2,589 Å (2), C = 697 Å (2), D = 764 Å (2), and A(NMR) = 660 Å (2). β-strands (magenta), α-helices (blue), and loops (green) are color coded. (b) Interactions between adjacent C-terminal domains and protein-detergent (CHAPS) interactions are shown. (Top) Interface B, in an orientation rotated 90° relative to that in a. (Middle) Interface C. (Bottom) Interface D. Interfaces C and D are in an identical orientation as in a. Figure was generated by using molscript (44) and raster3d (45). Surface area was calculated by using surface (48).

Discussion

The Y-shaped dimer of HIV-1 IN52–288 to 2.8-Å resolution is the first reported multidomain structure for HIV-1 IN and can be compared with analogous structures for RSV IN (32) and SIV IN (28). The introduction of five mutations, C56S, W131D, F139D, F185K, and C280S, did not alter the structure of the catalytic core compared with other structures containing only one of these four mutations, F185K (12), or mutation F185H (26, 31). The finding of an identical catalytic core domain structure alone (IN52–210) or attached to the C-terminal domain (IN52–288) argues that the dimeric core structure also will be found in full-length IN. The three catalytic residues, D64, D116, and E152, are visible in at least one monomer of IN52–288.

Relationship Between the Catalytic and C-Terminal Domains.

The two linking α6 helices of the IN52–288 dimer begin in a 2-fold symmetric manner out to T210. A kink in α6 occurs at T210 in one monomer, introducing a 90° rotation of one C-terminal domain and its leading helical stem relative to the other (Fig. 2 b and c). A previously identified proteolytic cleavage site near T210 suggests that the kink may represent a flexible junction in solution (5). This flexible elbow within α6 may reflect a key functional determinant that permits a dynamic role for each C-terminal domain during the multistep integration process.

In contrast to HIV-1 IN52–288, the link between the catalytic and C-terminal domains in the RSV IN structure (32) is comprised of a short, six-residue β-strand that immediately deviates at W213 from the 2-fold symmetry of the core. For SIV IN (28), only one of the four C-terminal domains within the asymmetric unit can be resolved. It is packed against helix α6 within the core domain, and residues 211–220 of the linking sequence do not form a helix. The different orientations of the catalytic core and C-terminal domains among the RSV, SIV, and HIV-1 IN structures further support the notion of a functional flexibility within the linking sequence.

The NMR structure for residues 220–270 of the HIV-1 C-terminal domain is a dimer involving antiparallel, 2-fold related packing of the contiguous β2-β3-β4 three-stranded β-sheets against each other (16, 17). Although it differs from all three C-terminal interfaces in the IN52–288 crystal structure, the NMR dimer interface most closely resembles IN52–288 interface B that involves the β2-β3-β4 sheets. However, interface B is mediated by a CHAPS molecule and the sheets in interface B and the NMR structure are packed in opposite orientations. This orientation difference is likely caused by a biologically relevant restriction imposed by having the C-terminal domain linked to the catalytic core domain in IN52–288, a restriction not imposed on an isolated C-terminal domain. Although the C-terminal interactions involving adjacent HIV-1 IN52–288 dimers determine the crystal packing, they and the dimer interface in the isolated C-terminal structure may represent favorable interactions that facilitate the higher-order complex required for properly spaced, concerted integration into the host DNA. Mutagenesis of residues within the C-terminal domains suggests that higher-order oligomerization of HIV-1 IN in solution is facilitated by the C-terminal domains (33, 34).

The Viral DNA Binding Platform.

A contiguous strip of positive charge extending from the catalytic site along the outside face of the IN52–288 dimer includes residue K159, which can cross-link to the adenine of the invariant 3′ CA at each viral end (Fig. 3a) (35). It continues through residues K186, R187, and K188, and out to residues K211, K215, and K219 of the α6 helix from the paired monomer in the dimer (Fig. 3a). This strip of positive potential may provide a platform on which viral att site DNA could be stabilized for 3′ processing and strand transfer. This putative DNA binding platform involves residues from both monomers within the IN52–288 dimer, implying that a viral end cleaved in the active site of one monomer is stabilized by residues from the C terminus of the other monomer. This could explain in vitro complementation data in which two inactive IN mutants can be combined to regain IN activity (36, 37). Docking of an 18-bp viral DNA end to IN52–288 places the adenine of the conserved viral 3′ CA in direct contact with K159, places the active site proximal loop involving residues 186–194 in contact with the major groove of the DNA, and places α6 helix residues K211, K215, and K219 of the other monomer in contact with the DNA backbone phosphates (Fig. 3b). In contrast, the structures of two-domain IN from SIV and RSV highlight different putative DNA binding platforms derived from the different spatial arrangements of the C-terminal domain relative to the catalytic core domain. Therefore, the structure of a DNA-bound form of IN will be necessary to distinguish these possibilities.

Residues R263 and K264 in the β4-β5 turn of the HIV-1 IN C-terminal domains can be cross-linked to viral DNA 4–6 base pairs, 14–21 Å, from the conserved terminal CA dinucleotide (38–40). This distance is much closer than the 62 Å between the catalytic site and R263 in the IN52–288 structure (Fig. 3b). The cross-linking data therefore may reflect interactions between viral DNA held by one dimer and the C-terminal domain from an adjacent dimer. This would require two dimers at each viral end or two IN tetramers in a fully active complex. Interestingly, recent cross-linking data suggested an IN octamer as the active complex for concerted integration of both viral ends (40). Alternatively, the connecting α6 helix of one protomer within a dimer could be extended when binding DNA while the connecting α6 helix from the other protomer folds at the flexible elbow (T210), thereby placing R263 ≈20 Å, or one-half turn of duplex DNA, from the conserved CA dinucleotide. Extreme α6 flexibility, well beyond what we see for IN (), could allow the C-terminal domain to pack against the catalytic core as seen in the SIV IN structure (28). In any of these models, a flexible elbow in the linking sequence allows the C-terminal domains to help tether the DNA during the integration process.

Interaction of DNA with the C-Terminal Domain.

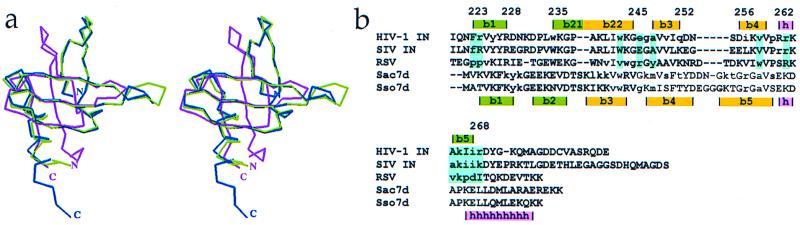

Two structures of DNA-bound to Src homology 3 (SH3)-like folds are known (41–43). The proteins involved, Sso7d and Sac7d, bind in the minor groove of double-stranded DNA in a sequence-independent manner. Hydrophobic groups on the surface of an SH3-fold β-sheet in each protein intercalate into the minor groove of the bound DNA, which widens the groove and sharply kinks the DNA. Although these proteins do not have significant overall sequence homology with the C-terminal domain of HIV-1 IN, alignment of the C-terminal domain crystal structure with those of Sso7d and Sac7d shows that they have similar folds, with rms deviations of 2.2 Å and 1.9 Å, respectively (Fig. 6). The structural similarity is most pronounced at the β-sheet that binds to DNA, which corresponds to the β2-β3-β4 sheet that figures prominently in the C-terminal interactions observed in the HIV IN52–288 structure (Fig. 5). The hydrophobic surface of this IN β-sheet, and the corresponding ones in Sso7d and Sac7d, includes a conserved W243 that interfaces with CHAPS in the IN structure and with DNA bases in the Sso7d and Sac7d structures. We speculate that the HIV-1 IN β2-β3-β4 sheet may bind DNA in a manner analogous to Sso7d and Sac7d.

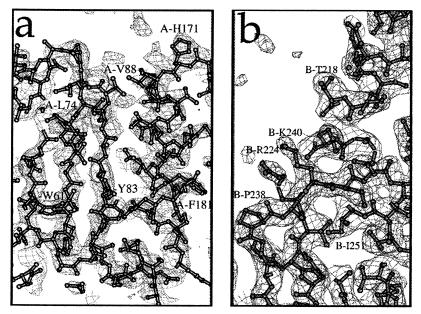

Figure 6.

Comparison of the SH3-like folds from HIV-1 IN, Sac7d, and Sso7d. (a) α-Carbon overlay of the HIV-1 IN C-terminal domain (magenta), Sac7d (green), and Sso7d (blue) structures demonstrates significant structural similarity. (b) Primary sequence alignment of the IN C-terminal domains from HIV-1, SIV, and RSV, and DNA-binding proteins Sac7d and Sso7d based on secondary structure (HIV-1 IN residue numbering). Secondary structural elements are highlighted. Yellow and green denote the β-strands contributing to the β-sandwich structure of the IN C-terminal domains, Sac7d, and Sso7d. Lowercase lettering indicates residues in IN that are involved in protein–protein interactions, and residues in Sac7d and Sso7d that are involved in protein-DNA interactions. Residues highlighted in cyan are involved in protein–protein contacts in at least two of the molecules.

The diversity and hydrophobic character of the protein–protein interactions involving the C-terminal domains from HIV-1, RSV (32), and SIV (28) suggest that they are weak and nonspecific. Because of flexibility in the linker between domains, the C-terminal domains can adopt a wide range of orientations relative to the catalytic core, and none of the protein–protein interactions seen in the crystal structures may actually be present in DNA-bound forms of the protein. The interactions do, however, involve residues that are clustered on the β2-β3-β4 sheet and on the C-terminal strand β5 (Figs. 5 and 6b), suggesting these are binding epitopes that may contribute to DNA binding and IN oligomerization.

HIV-1 IN catalyzes the insertion of the viral cDNA into the human genome and is required for viral replication and pathogenesis (11). As such, IN is a promising target for the design of anti-HIV drugs. The determination of the two-domain HIV-1 IN structure, IN52–288, should prove useful for structure-based efforts to design new IN inhibitors, especially those that may act through perturbation of critical interactions between IN and the viral ends. This can be tested through cocrystallization with DNA and new mutants, experiments that will assist in drug design and will add to our understanding of how IN works.

Acknowledgments

We thank Harold Varmus with whom we started this effort; Robert Rose, Thomas Anderson, George Robles, Earl Rutenber, and Kimiko Yabe for work performed in the early stages of this project; Aina Cohen and Ashley Deacon at Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory for assistance with data collection; and Patrick Brown (Stanford University) for sharing his synthetic HIV-1 IN gene. This work was funded by National Institutes of Health Grant GM56531 to R.M.S. and A.D.L.

Abbreviations

- IN

integrase

- CHAPS

3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate

- SIV

simian immunodeficiency virus

- RSV

Rous sarcoma virus

- SH3

Src homology 3

Footnotes

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.rcsb.org [PDB ID codes 1EXQ (IN52–210) and 1EX4 (IN52–288)].

Article published online before print: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 10.1073/pnas.150220297.

Article and publication date are at www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.150220297

References

- 1.Engelman A, Mizuuchi K, Craigie R. Cell. 1991;67:1211–1221. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90297-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson M S, McClure M A, Feng D F, Gray J, Doolittle R F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:7648–7652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.20.7648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan E, Mack J P, Katz R A, Kulkosky J, Skalka A M. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:851–860. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.4.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bushman F D, Engelman A, Palmer I, Wingfield P, Craigie R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3428–3432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engelman A, Craigie R. J Virol. 1992;66:6361–6369. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6361-6369.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leavitt A D, Shiue L, Varmus H E. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:2113–2119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kulkosky J, Jones K S, Katz R A, Mack J P, Skalka A M. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2331–2338. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.5.2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Gent D C, Groeneger A A, Plasterk R H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:9598–9602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vincent K A, Ellison V, Chow S A, Brown P O. J Virol. 1993;67:425–437. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.1.425-437.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng R, Jenkins T, Craigie R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13659–13664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown P. In: Retroviruses. Coffin S, Hughes S H, Varmus H E, editors. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1997. pp. 161–203. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dyda F, Hickman A B, Jenkins T M, Engelman A, Craigie R, Davies D R. Science. 1994;266:1981–1986. doi: 10.1126/science.7801124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jenkins T M, Hickman A B, Dyda F, Ghirlando R, Davies D R, Craigie R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6057–6061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.6057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai M, Zheng R, Caffrey M, Craigie R, Clore G M, Gronenborn A M. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:567–577. doi: 10.1038/nsb0797-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai M, Huang Y, Caffrey M, Zheng R, Craigie R, Clore G M, Gronenborn A M. Protein Sci. 1998;7:2669–2674. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560071221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eijkelenboom A P, Lutzke R A, Boelens R, Plasterk R H, Kaptein R, Hard K. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:807–810. doi: 10.1038/nsb0995-807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lodi P J, Ernst J A, Kuszewski J, Hickman A B, Engelman A, Craigie R, Clore G M, Gronenborn A M. Biochemistry. 1995;34:9826–9833. doi: 10.1021/bi00031a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eijkelenboom A P, Sprangers R, Hard K, Puras Lutzke R A, Plasterk R H, Boelens R, Kaptein R. Proteins. 1999;36:556–564. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19990901)36:4<556::aid-prot18>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brunger A T, Adams P D, Clore G M, Delano W L, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve R W, Jiang J-S, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu N S, et al. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldgur Y, Dyda F, Hickman A B, Jenkins T M, Craigie R, Davies D R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9150–9154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chambers J L, Stroud R M. Acta Crystallogr B. 1977;33:1824–1837. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sack J S. J Mol Graphics. 1988;6:224–225. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kissinger C R, Gehlhaar D K, Fogel D B. Acta Crystallogr D. 1999;55:484–491. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998012517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aiken C, Konner J, Landau N R, Lenburg M E, Trono D. Cell. 1994;76:853–864. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maignan S, Guilloteau J P, Zhou-Liu Q, Clement-Mella C, Mikol V. J Mol Biol. 1998;282:359–368. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenwald J, Le V, Butler S L, Bushman F, Choe S. Biochemistry. 1999;38:8892–8898. doi: 10.1021/bi9907173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Z, Yan Y, Munshi S, Li Y, Zugay-Murphy J, Xu B, Witmer M, Felock P, Wolfe A, Sardana V, et al. J Mol Biol. 2000;296:521–533. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bujacz G, Jaskolski M, Alexandratos J, Wlodawer A, Merkel G, Katz R A, Skalka A M. J Mol Biol. 1995;253:333–346. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stroud R M, Fauman E B. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2392–2404. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bujacz G, Alexandratos J, Qing Z L, Clément-Mella C, Wlodawer A. FEBS Lett. 1996;398:175–178. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01236-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang Z N, Mueser T C, Bushman F D, Hyde C C. J Mol Biol. 2000;296:535–548. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paras Lutzke R A, Plasterk R H A. J Virol. 1998;72:4841–4848. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4841-4848.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jenkins T M, Engelman A, Ghirlando R, Craigie R. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7712–7718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jenkins T M, Esposito D, Engelman A, Craigie R. EMBO J. 1997;16:6849–6859. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.22.6849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Gent D C, Vink C, Groeneger A A, Plasterk R H. EMBO J. 1993;12:3261–3267. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05995.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Engelman A, Bushman F D, Craigie R. EMBO J. 1993;12:3269–3275. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05996.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Esposito D, Craigie R. EMBO J. 1998;17:5832–5843. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heuer T S, Brown P O. Biochemistry. 1997;36:10655–10665. doi: 10.1021/bi970782h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heuer T S, Brown P O. Biochemistry. 1998;37:6667–6678. doi: 10.1021/bi972949c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robinson H, Gao Y G, McCrary B S, Edmondson S P, Shriver J W, Wang A H. Nature (London) 1998;392:202–205. doi: 10.1038/32455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krueger J K, McCrary B S, Wang A H, Shriver J W, Trewhella J, Edmondson S P. Biochemistry. 1999;38:10247–10255. doi: 10.1021/bi990782c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao Y G, Su S Y, Robinson H, Padmanabhan S, Lim L, McCrary B S, Edmondson S P, Shriver J W, Wang A H. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:782–786. doi: 10.1038/1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kraulis P J. J Appl Crystallogr. 1991;24:946–950. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Merritt E A, Murphy M E P. Acta Crystallogr D. 1994;50:869–873. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994006396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferrin T E, Huang C C, Jarvis L E, Langridge R. J Mol Graphics. 1988;6:13–27. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nicholls A, Sharp K A, Honig B. Proteins. 1991;11:281–296. doi: 10.1002/prot.340110407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.CCP4. Acta Crystallogr D. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]